User login

Persistent Flu-Like Symptoms in a Patient With Glaucoma and Osteoporosis

A 62-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with 3 days of chills, myalgias, and nausea. The patient’s oral temperature at home ranged from 99.9 to 100.1 °F. He came to the ED after multiple phone discussions with primary care nursing over 3 days. His medical history included posttraumatic stress disorder, enlarged prostate, osteoporosis, gastroesophageal reflux, glaucoma, and left eye central retinal vein occlusion. Medications included fluoxetine 20 mg twice daily, omeprazole 20 mg twice daily, rosuvastatin 10 mg once daily, tamsulosin 0.4 mg nightly, and zolpidem 10 mg nightly. The patient’s glaucoma had been treated with a dexamethasone intraocular implant about 90 days earlier. The patient started on intravenous (IV) zoledronic acid for osteoporosis, with the first infusion 5 days prior to presentation.

In the ED, the patient’s temperature was 98.2 °F, blood pressure was 156/76 mm Hg, pulse was 94 bpm, respiratory rate was 16 breaths per minute, and 98% oxygen saturation on room air. He was in no acute distress, with an unremarkable physical examination reporting no abnormal respiratory sounds, no arrhythmia, normal gait, and no focal neurologic deficits. A comprehensive metabolic panel was unremarkable, creatine phosphokinase was 155 U/L (reference range, 30-240 U/L), and the complete blood count was notable only for an elevated white blood count of 15.3 × 109/L (reference range, 4.0-11.0 × 109/L), with 73.4% neutrophils, 16.2% lymphocytes, 9.1% monocytes, 0.5% eosinophils, and 0.4% basophils. The patient’s urinalysis was unremarkable.

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

Discussion

The ED physician considered viral infection and tested for both influenza and COVID-19. Laboratory results eliminated urinary tract infection and rhabdomyolysis as possible diagnoses. An acute phase reaction to zoledronic acid was determined to be the most likely cause. The patient was treated with IV saline in the ED, and acetaminophen both in the ED and at home.

Although initial nursing triage notes document consideration of acute phase reaction to zoledronic acid, the endocrinology service, which had recommended and arranged the zoledronic acid infusion, was not immediately notified of the reaction. It does not appear any treatment (eg, acetaminophen) was suggested, only that the patient was given advice this may resolve over 3 to 4 days. When he was seen 2 months later for an endocrinology follow-up appointment, he reported that all symptoms (chills, myalgias, and nausea) resolved gradually over 1 week. Since then, he has felt as well as he did before taking zoledronic acid. However, the patient was wary of further zoledronic acid, opting to defer deciding on a second dose until a future appointment.

Prior to starting zoledronic acid therapy, the patient was being treated for vitamin D deficiency. Four months prior to infusion, his 25-hydroxyvitamin D level was 12.0 ng/mL (reference range, 30 to 80 ng/mL). He then started taking cholecalciferol 100 mcg (4000 IU) daily. Eight days prior to infusion his 25-hydroxyvitamin D level was 29.5 ng/mL.

Federal health care practitioners, especially those working in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), will commonly encounter patients similar to this case. Osteoporosisis is common in the United States with > 10 million diagnoses (including > 2 million men) and in VHA primary care populations.1,2 Zoledronic acid is a frequently prescribed treatment, appearing in guidelines for osteoporosis management.3-5

The acute phase reaction is a common adverse effect of both oral and IV bisphosphonates, although it’s substantially more common with IV bisphosphonates such as zoledronic acid. This reaction is characterized by flu-like symptoms of fever, myalgia, and arthralgia that occur within the first few days following bisphosphonate administration, and tends to be rated mild to moderate by patients.6 Clinical trial data from > 7000 women with postmenopausal osteoporosis found that 42% experienced ≥ 1 acute phase symptom following the first infusion (fever was most common, followed by musculoskeletal symptoms and gastrointestinal symptoms), compared with 12% for placebo. Incidence decreases with each subsequent infusion.7 Risk factors for reactions include low 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels,8,9 no prior bisphosphonate exposure,9 younger age (aged 64-67 years vs 78-89 years),7 lower body mass index,10 and higher lymphocyte levels at baseline.11 While most cases are mild and self-limited, severe consequences have been noted, such as precipitation of adrenal crisis.12,13 Additionally, more prolonged bone pain, sometimes quite severe, has been rarely reported with bisphosphonate use. However, it’s unclear whether this represents a separate adverse effect or a more severe acute phase reaction.6

The acute phase reaction is a transient inflammatory state marked by increases in proinflammatory cytokines such as C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α. Proposed mechanisms include: (1) inhibition of farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase, an enzyme of the mevalonate pathway, resulting inactivation of γϐ T cells and increased production of proinflammatory cytokines; (2) inhibition of the suppressor of cytokine signalling-3 in the macrophages, resulting in cessation of the suppression in cytokine signaling; or (3) negative regulation of γϐ T-cell expansion and interferon-c production by low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations.11

Prevention

Can an acute phase reaction to zoledronic acid be prevented? Bourke and colleagues reported that baseline calcium and/or vitamin D intake do not appear to affect rates of acute phase reaction in data pooled from 2 trials of zoledronic acid in postmenopausal women.14 However, patients receiving zoledronic acid had 25-hydroxyvitamin D values > 20 ng/mL 86% of the time, and values > 30 ng/mL 36% of the time. Bourke and colleagues suggest that “coadministration of calcium and vitamin D with zoledronate may not be necessary for individuals not at risk of marked vitamin D deficiency.”14 However, they did not prospectively test this hypothesis.

In our patient, vitamin D deficiency had been identified and treated, nearly achieving 30 ng/mL. The 2020 guidelines for postmenopausal osteoporosis recommend maintaining serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels 30 to 50 ng/mL, advising to supplement with vitamin D3 as needed.5 The 2012 guidelines for osteoporosis in men from the Endocrine Society suggest that men with low vitamin D levels receive vitamin D supplements to raise the level > 30 ng/ml.4

Oral analgesics have been studied for the prevention of adverse effects related to zoledronic acid. Initiating 650 mg acetaminophen 45 minutes before zoledronic acid infusion and then every 6 hours over the next 3 days has been shown to significantly reduce symptoms.15 Acetaminophen or ibuprofen given every 6 hours for 3 days (starting 4 hours after zoledronic acid infusion) has been shown to reduce fever and other symptoms.16

Statins have been shown in vitro to prevent bisphosphonate-induced γϐ T cell activation.17 This has led to studies with various statins, although none have yet shown benefit in vivo. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of postmenopausal women for fluvastatin (single dose of 40 mg or 3 doses of 40 mg, each 24 hours apart) did not prevent acute phase reaction symptoms, nor did it prevent zoledronic acid-induced cytokine release.17 Rosuvastatin 10 mg daily starting 5 days before zoledronic acid treatment and taken for a total of 11 days did not show any difference in fever or pain.18 A protocol for pravastatin has been disseminated, but no study results have been published yet.19

Prophylactic dexamethasone has also been studied. A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral dexamethasone 4 mg at the time of first infusion of zoledronic acid found no significant difference in temperature change or symptom score over the following 3 days.20 Chen and colleagues compared the efficacy of acetaminophen alone vs acetaminophen plus dexamethasone over several days.21 Acetaminophen 500 mg was given on the day of infusion and 4 times daily for 3 to 7 days for both groups, while dexamethasone 4 mg was given for 3 to 7 days. The dexamethasone group reported substantially lower incidence of any acute phase reaction symptoms (34% vs 67%, P = .003). A more recent study by Murdoch and colleagues comparing dexamethasone (4 mg daily for 3 days with the first dose 90 minutes before zoledronic acid infusion) with placebo found that the dexamethasone group had a statistically significant lower mean temperature change and acute phase reaction symptom score.22

Adverse Effect Treatment

Treatment after development of acute phase reaction due to zoledronic acid infusion is generally limited to supportive care and/or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) acetaminophen or dexamethasone, largely based on extrapolation of the noted preventive trials and expert opinion.3,6 Experiencing an acute phase reaction may portend better fracture risk reduction from zoledronic acid, although there is a potential association between acute phase reaction and mortality risk.23,24

Our case was typical for acute phase reaction to zoledronic acid. The patient was already taking rosuvastatin 10 mg daily for hypercholesterolemia as prescribed by his primary care physician. Rosuvastatin was not shown to prevent symptoms, although it was not studied in patients on long-term statin therapy at the time of zoledronic acid infusion.18 The patient was also taking vitamin D3 supplementation and was nearly in the reference range.5 His ED treatment included IV fluids and acetaminophen. Pretreatment (prior to or at the time of zoledronic acid infusion) with acetaminophen or ibuprofen may have prevented his symptoms, or at least lessened them to the point that an ED visit would not have resulted. The endocrinologist who prescribed the zoledronic acid documented a detailed discussion of the adverse effects of zoledronic acid with the patient, and the initial nursing call documents consideration of acute phase reaction. It is unclear whether the persistence of symptoms or worsening of symptoms ultimately led to the ED visit. Because no treatment was offered, it is unknown whether earlier posttreatment with acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or dexamethasone might have prevented his ED visit.

Conclusions

Clinicians who treat patients with osteoporosis should be aware of several key points. First, acute phase reaction symptoms are common with bisphosphonates, especially zoledronic acid infusions. Second, the symptoms are nonspecific but should have a suggestive time course. Third, dexamethasone may be partially protective, but based on the various trials discussed, it likely needs to be given for multiple days (instead of a single dose on the day of infusion). Given that acetaminophen and NSAIDs also seem to be protective (when given for multiple days starting on the day of infusion), both have lower overall adverse effect profiles than dexamethasone, consideration may be given to using either of these prophylactically.6 Dexamethasone could then be prescribed if symptoms are severe or persistent despite the use of acetaminophen or NSAIDs.

1. Choksi P, Gay BL, Reyes-Gastelum D, Haymart MR, Papaleontiou M. Understanding osteoporosis screening practices in men: a nationwide physician survey. Endocr Pract. 2020;26(11):1237-1243. doi:10.4158/EP-2020-0123

2. Yu ZL, Fisher L, Hand J. Osteoporosis screening for male veterans in a resident based primary care clinic at Northport Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Am J Med Qual. 2023;38(5):272.doi:10.1097/JMQ.0000000000000134

3. Eastell R, Rosen CJ, Black DM, Cheung AM, Murad MH, Shoback D. Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: an Endocrine Society* clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(5):1595-1622. doi:10.1210/jc.2019-00221

4. Watts NB, Adler RA, Bilezikian JP, et al. Osteoporosis in men: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(6):1802-1822. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3045

5. Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis – 2020 update. Endocr Pract. 2020;26(suppl 1):1-46. doi:10.4158/GL-2020-0524SUPPL

6. Lim SY, Bolster MB. What can we do about musculoskeletal pain from bisphosphonates?. Cleve Clin J Med. 2018;85(9):675-678. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.18005

7. Reid IR, Gamble GD, Mesenbrink P, Lakatos P, Black DM. Characterization of and risk factors for the acute-phase response after zoledronic acid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(9):4380-4387. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-0597

8. Lu K, Shi Q, Gong YQ, Li C. Association between vitamin D and zoledronate-induced acute-phase response fever risk in osteoporotic patients. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:991913. Published 2022 Oct 10. doi:10.3389/fendo.2022.991913

9. Popp AW, Senn R, Curkovic I, et al. Factors associated with acute-phase response of bisphosphonate-naïve or pretreated women with osteoporosis receiving an intravenous first dose of zoledronate or ibandronate. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(6):1995-2002. doi:10.1007/s00198-017-3992-5

10. Zheng X, Ye J, Zhan Q, et al. Prediction of musculoskeletal pain after the first intravenous zoledronic acid injection in patients with primary osteoporosis: development and evaluation of a new nomogram. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24(1):841. Published 2023 Oct 25. doi:10.1186/s12891-023-06965-y

11. Anastasilakis AD, Polyzos SA, Delaroudis S, et al. The role of cytokines and adipocytokines in zoledronate-induced acute phase reaction in postmenopausal women with low bone mass. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012;77(6):816-822. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2012.04459.x

12. Smrecnik M, Kavcic Trsinar Z, Kocjan T. Adrenal crisis after first infusion of zoledronic acid: a case report. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(7):1675-1678. doi:10.1007/s00198-018-4508-7

13. Kuo B, Koransky A, Vaz Wicks CL. Adrenal crisis as an adverse reaction to zoledronic acid in a patient with primary adrenal insufficiency: a case report and literature review. AACE Clin Case Rep. 2022;9(2):32-34. Published 2022 Dec 17. doi:10.1016/j.aace.2022.12.003

14. Bourke S, Bolland MJ, Grey A, et al. The impact of dietary calcium intake and vitamin D status on the effects of zoledronate. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(1):349-354. doi:10.1007/s00198-012-2117-4

15. Silverman SL, Kriegman A, and Goncalves J, et al. Effect of acetaminophen and fluvastatin on post-dose symptoms following infusion of zoledronic acid. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(8):2337-2345.

16. Wark JD, Bensen W, Recknor C, et al. Treatment with acetaminophen/paracetamol or ibuprofen alleviates post-dose symptoms related to intravenous infusion with zoledronic acid 5 mg. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(2):503-512. doi:10.1007/s00198-011-1563-8

17. Thompson K, Keech F, McLernon DJ, et al. Fluvastatin does not prevent the acute-phase response to intravenous zoledronic acid in post-menopausal women. Bone. 2011;49(1):140-145. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2010.10.177

18. Makras P, Anastasilakis AD, Polyzos SA, Bisbinas I, Sakellariou GT, Papapoulos SE. No effect of rosuvastatin in the zoledronate-induced acute-phase response. Calcif Tissue Int. 2011;88(5):402-408. doi:10.1007/s00223-011-9468-2

19. Liu Q, Han G, Li R, et al. Reduction effect of oral pravastatin on the acute phase response to intravenous zoledronic acid: protocol for a real-world prospective, placebo-controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2022;12(7):e060703. Published 2022 Jul 13. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060703

20. Billington EO, Horne A, Gamble GD, Maslowski K, House M, Reid IR. Effect of single-dose dexamethasone on acute phase response following zoledronic acid: a randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(6):1867-1874. doi:10.1007/s00198-017-3960-0

21. Chen FP, Fu TS, Lin YC, Lin YJ. Addition of dexamethasone to manage acute phase responses following initial zoledronic acid infusion. Osteoporos Int. 2021;32(4):663-670. doi:10.1007/s00198-020-05653-0

22. Murdoch R, Mellar A, Horne AM, et al. Effect of a three-day course of dexamethasone on acute phase response following treatment with zoledronate: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2023;38(5):631-638. doi:10.1002/jbmr.4802

23. Black DM, Reid IR, Napoli N, et al. The interaction of acute-phase reaction and efficacy for osteoporosis after zoledronic acid: HORIZON pivotal fracture trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2022;37(1):21-28. doi:10.1002/jbmr.4434

24. Lu K, Wu YM, Shi Q, Gong YQ, Zhang T, Li C. The impact of acute-phase reaction on mortality and re-fracture after zoledronic acid in hospitalized elderly osteoporotic fracture patients. Osteoporos Int. 2023;34(9):1613-1623. doi:10.1007/s00198-023-06803-w

A 62-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with 3 days of chills, myalgias, and nausea. The patient’s oral temperature at home ranged from 99.9 to 100.1 °F. He came to the ED after multiple phone discussions with primary care nursing over 3 days. His medical history included posttraumatic stress disorder, enlarged prostate, osteoporosis, gastroesophageal reflux, glaucoma, and left eye central retinal vein occlusion. Medications included fluoxetine 20 mg twice daily, omeprazole 20 mg twice daily, rosuvastatin 10 mg once daily, tamsulosin 0.4 mg nightly, and zolpidem 10 mg nightly. The patient’s glaucoma had been treated with a dexamethasone intraocular implant about 90 days earlier. The patient started on intravenous (IV) zoledronic acid for osteoporosis, with the first infusion 5 days prior to presentation.

In the ED, the patient’s temperature was 98.2 °F, blood pressure was 156/76 mm Hg, pulse was 94 bpm, respiratory rate was 16 breaths per minute, and 98% oxygen saturation on room air. He was in no acute distress, with an unremarkable physical examination reporting no abnormal respiratory sounds, no arrhythmia, normal gait, and no focal neurologic deficits. A comprehensive metabolic panel was unremarkable, creatine phosphokinase was 155 U/L (reference range, 30-240 U/L), and the complete blood count was notable only for an elevated white blood count of 15.3 × 109/L (reference range, 4.0-11.0 × 109/L), with 73.4% neutrophils, 16.2% lymphocytes, 9.1% monocytes, 0.5% eosinophils, and 0.4% basophils. The patient’s urinalysis was unremarkable.

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

Discussion

The ED physician considered viral infection and tested for both influenza and COVID-19. Laboratory results eliminated urinary tract infection and rhabdomyolysis as possible diagnoses. An acute phase reaction to zoledronic acid was determined to be the most likely cause. The patient was treated with IV saline in the ED, and acetaminophen both in the ED and at home.

Although initial nursing triage notes document consideration of acute phase reaction to zoledronic acid, the endocrinology service, which had recommended and arranged the zoledronic acid infusion, was not immediately notified of the reaction. It does not appear any treatment (eg, acetaminophen) was suggested, only that the patient was given advice this may resolve over 3 to 4 days. When he was seen 2 months later for an endocrinology follow-up appointment, he reported that all symptoms (chills, myalgias, and nausea) resolved gradually over 1 week. Since then, he has felt as well as he did before taking zoledronic acid. However, the patient was wary of further zoledronic acid, opting to defer deciding on a second dose until a future appointment.

Prior to starting zoledronic acid therapy, the patient was being treated for vitamin D deficiency. Four months prior to infusion, his 25-hydroxyvitamin D level was 12.0 ng/mL (reference range, 30 to 80 ng/mL). He then started taking cholecalciferol 100 mcg (4000 IU) daily. Eight days prior to infusion his 25-hydroxyvitamin D level was 29.5 ng/mL.

Federal health care practitioners, especially those working in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), will commonly encounter patients similar to this case. Osteoporosisis is common in the United States with > 10 million diagnoses (including > 2 million men) and in VHA primary care populations.1,2 Zoledronic acid is a frequently prescribed treatment, appearing in guidelines for osteoporosis management.3-5

The acute phase reaction is a common adverse effect of both oral and IV bisphosphonates, although it’s substantially more common with IV bisphosphonates such as zoledronic acid. This reaction is characterized by flu-like symptoms of fever, myalgia, and arthralgia that occur within the first few days following bisphosphonate administration, and tends to be rated mild to moderate by patients.6 Clinical trial data from > 7000 women with postmenopausal osteoporosis found that 42% experienced ≥ 1 acute phase symptom following the first infusion (fever was most common, followed by musculoskeletal symptoms and gastrointestinal symptoms), compared with 12% for placebo. Incidence decreases with each subsequent infusion.7 Risk factors for reactions include low 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels,8,9 no prior bisphosphonate exposure,9 younger age (aged 64-67 years vs 78-89 years),7 lower body mass index,10 and higher lymphocyte levels at baseline.11 While most cases are mild and self-limited, severe consequences have been noted, such as precipitation of adrenal crisis.12,13 Additionally, more prolonged bone pain, sometimes quite severe, has been rarely reported with bisphosphonate use. However, it’s unclear whether this represents a separate adverse effect or a more severe acute phase reaction.6

The acute phase reaction is a transient inflammatory state marked by increases in proinflammatory cytokines such as C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α. Proposed mechanisms include: (1) inhibition of farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase, an enzyme of the mevalonate pathway, resulting inactivation of γϐ T cells and increased production of proinflammatory cytokines; (2) inhibition of the suppressor of cytokine signalling-3 in the macrophages, resulting in cessation of the suppression in cytokine signaling; or (3) negative regulation of γϐ T-cell expansion and interferon-c production by low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations.11

Prevention

Can an acute phase reaction to zoledronic acid be prevented? Bourke and colleagues reported that baseline calcium and/or vitamin D intake do not appear to affect rates of acute phase reaction in data pooled from 2 trials of zoledronic acid in postmenopausal women.14 However, patients receiving zoledronic acid had 25-hydroxyvitamin D values > 20 ng/mL 86% of the time, and values > 30 ng/mL 36% of the time. Bourke and colleagues suggest that “coadministration of calcium and vitamin D with zoledronate may not be necessary for individuals not at risk of marked vitamin D deficiency.”14 However, they did not prospectively test this hypothesis.

In our patient, vitamin D deficiency had been identified and treated, nearly achieving 30 ng/mL. The 2020 guidelines for postmenopausal osteoporosis recommend maintaining serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels 30 to 50 ng/mL, advising to supplement with vitamin D3 as needed.5 The 2012 guidelines for osteoporosis in men from the Endocrine Society suggest that men with low vitamin D levels receive vitamin D supplements to raise the level > 30 ng/ml.4

Oral analgesics have been studied for the prevention of adverse effects related to zoledronic acid. Initiating 650 mg acetaminophen 45 minutes before zoledronic acid infusion and then every 6 hours over the next 3 days has been shown to significantly reduce symptoms.15 Acetaminophen or ibuprofen given every 6 hours for 3 days (starting 4 hours after zoledronic acid infusion) has been shown to reduce fever and other symptoms.16

Statins have been shown in vitro to prevent bisphosphonate-induced γϐ T cell activation.17 This has led to studies with various statins, although none have yet shown benefit in vivo. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of postmenopausal women for fluvastatin (single dose of 40 mg or 3 doses of 40 mg, each 24 hours apart) did not prevent acute phase reaction symptoms, nor did it prevent zoledronic acid-induced cytokine release.17 Rosuvastatin 10 mg daily starting 5 days before zoledronic acid treatment and taken for a total of 11 days did not show any difference in fever or pain.18 A protocol for pravastatin has been disseminated, but no study results have been published yet.19

Prophylactic dexamethasone has also been studied. A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral dexamethasone 4 mg at the time of first infusion of zoledronic acid found no significant difference in temperature change or symptom score over the following 3 days.20 Chen and colleagues compared the efficacy of acetaminophen alone vs acetaminophen plus dexamethasone over several days.21 Acetaminophen 500 mg was given on the day of infusion and 4 times daily for 3 to 7 days for both groups, while dexamethasone 4 mg was given for 3 to 7 days. The dexamethasone group reported substantially lower incidence of any acute phase reaction symptoms (34% vs 67%, P = .003). A more recent study by Murdoch and colleagues comparing dexamethasone (4 mg daily for 3 days with the first dose 90 minutes before zoledronic acid infusion) with placebo found that the dexamethasone group had a statistically significant lower mean temperature change and acute phase reaction symptom score.22

Adverse Effect Treatment

Treatment after development of acute phase reaction due to zoledronic acid infusion is generally limited to supportive care and/or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) acetaminophen or dexamethasone, largely based on extrapolation of the noted preventive trials and expert opinion.3,6 Experiencing an acute phase reaction may portend better fracture risk reduction from zoledronic acid, although there is a potential association between acute phase reaction and mortality risk.23,24

Our case was typical for acute phase reaction to zoledronic acid. The patient was already taking rosuvastatin 10 mg daily for hypercholesterolemia as prescribed by his primary care physician. Rosuvastatin was not shown to prevent symptoms, although it was not studied in patients on long-term statin therapy at the time of zoledronic acid infusion.18 The patient was also taking vitamin D3 supplementation and was nearly in the reference range.5 His ED treatment included IV fluids and acetaminophen. Pretreatment (prior to or at the time of zoledronic acid infusion) with acetaminophen or ibuprofen may have prevented his symptoms, or at least lessened them to the point that an ED visit would not have resulted. The endocrinologist who prescribed the zoledronic acid documented a detailed discussion of the adverse effects of zoledronic acid with the patient, and the initial nursing call documents consideration of acute phase reaction. It is unclear whether the persistence of symptoms or worsening of symptoms ultimately led to the ED visit. Because no treatment was offered, it is unknown whether earlier posttreatment with acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or dexamethasone might have prevented his ED visit.

Conclusions

Clinicians who treat patients with osteoporosis should be aware of several key points. First, acute phase reaction symptoms are common with bisphosphonates, especially zoledronic acid infusions. Second, the symptoms are nonspecific but should have a suggestive time course. Third, dexamethasone may be partially protective, but based on the various trials discussed, it likely needs to be given for multiple days (instead of a single dose on the day of infusion). Given that acetaminophen and NSAIDs also seem to be protective (when given for multiple days starting on the day of infusion), both have lower overall adverse effect profiles than dexamethasone, consideration may be given to using either of these prophylactically.6 Dexamethasone could then be prescribed if symptoms are severe or persistent despite the use of acetaminophen or NSAIDs.

A 62-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with 3 days of chills, myalgias, and nausea. The patient’s oral temperature at home ranged from 99.9 to 100.1 °F. He came to the ED after multiple phone discussions with primary care nursing over 3 days. His medical history included posttraumatic stress disorder, enlarged prostate, osteoporosis, gastroesophageal reflux, glaucoma, and left eye central retinal vein occlusion. Medications included fluoxetine 20 mg twice daily, omeprazole 20 mg twice daily, rosuvastatin 10 mg once daily, tamsulosin 0.4 mg nightly, and zolpidem 10 mg nightly. The patient’s glaucoma had been treated with a dexamethasone intraocular implant about 90 days earlier. The patient started on intravenous (IV) zoledronic acid for osteoporosis, with the first infusion 5 days prior to presentation.

In the ED, the patient’s temperature was 98.2 °F, blood pressure was 156/76 mm Hg, pulse was 94 bpm, respiratory rate was 16 breaths per minute, and 98% oxygen saturation on room air. He was in no acute distress, with an unremarkable physical examination reporting no abnormal respiratory sounds, no arrhythmia, normal gait, and no focal neurologic deficits. A comprehensive metabolic panel was unremarkable, creatine phosphokinase was 155 U/L (reference range, 30-240 U/L), and the complete blood count was notable only for an elevated white blood count of 15.3 × 109/L (reference range, 4.0-11.0 × 109/L), with 73.4% neutrophils, 16.2% lymphocytes, 9.1% monocytes, 0.5% eosinophils, and 0.4% basophils. The patient’s urinalysis was unremarkable.

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

Discussion

The ED physician considered viral infection and tested for both influenza and COVID-19. Laboratory results eliminated urinary tract infection and rhabdomyolysis as possible diagnoses. An acute phase reaction to zoledronic acid was determined to be the most likely cause. The patient was treated with IV saline in the ED, and acetaminophen both in the ED and at home.

Although initial nursing triage notes document consideration of acute phase reaction to zoledronic acid, the endocrinology service, which had recommended and arranged the zoledronic acid infusion, was not immediately notified of the reaction. It does not appear any treatment (eg, acetaminophen) was suggested, only that the patient was given advice this may resolve over 3 to 4 days. When he was seen 2 months later for an endocrinology follow-up appointment, he reported that all symptoms (chills, myalgias, and nausea) resolved gradually over 1 week. Since then, he has felt as well as he did before taking zoledronic acid. However, the patient was wary of further zoledronic acid, opting to defer deciding on a second dose until a future appointment.

Prior to starting zoledronic acid therapy, the patient was being treated for vitamin D deficiency. Four months prior to infusion, his 25-hydroxyvitamin D level was 12.0 ng/mL (reference range, 30 to 80 ng/mL). He then started taking cholecalciferol 100 mcg (4000 IU) daily. Eight days prior to infusion his 25-hydroxyvitamin D level was 29.5 ng/mL.

Federal health care practitioners, especially those working in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), will commonly encounter patients similar to this case. Osteoporosisis is common in the United States with > 10 million diagnoses (including > 2 million men) and in VHA primary care populations.1,2 Zoledronic acid is a frequently prescribed treatment, appearing in guidelines for osteoporosis management.3-5

The acute phase reaction is a common adverse effect of both oral and IV bisphosphonates, although it’s substantially more common with IV bisphosphonates such as zoledronic acid. This reaction is characterized by flu-like symptoms of fever, myalgia, and arthralgia that occur within the first few days following bisphosphonate administration, and tends to be rated mild to moderate by patients.6 Clinical trial data from > 7000 women with postmenopausal osteoporosis found that 42% experienced ≥ 1 acute phase symptom following the first infusion (fever was most common, followed by musculoskeletal symptoms and gastrointestinal symptoms), compared with 12% for placebo. Incidence decreases with each subsequent infusion.7 Risk factors for reactions include low 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels,8,9 no prior bisphosphonate exposure,9 younger age (aged 64-67 years vs 78-89 years),7 lower body mass index,10 and higher lymphocyte levels at baseline.11 While most cases are mild and self-limited, severe consequences have been noted, such as precipitation of adrenal crisis.12,13 Additionally, more prolonged bone pain, sometimes quite severe, has been rarely reported with bisphosphonate use. However, it’s unclear whether this represents a separate adverse effect or a more severe acute phase reaction.6

The acute phase reaction is a transient inflammatory state marked by increases in proinflammatory cytokines such as C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α. Proposed mechanisms include: (1) inhibition of farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase, an enzyme of the mevalonate pathway, resulting inactivation of γϐ T cells and increased production of proinflammatory cytokines; (2) inhibition of the suppressor of cytokine signalling-3 in the macrophages, resulting in cessation of the suppression in cytokine signaling; or (3) negative regulation of γϐ T-cell expansion and interferon-c production by low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations.11

Prevention

Can an acute phase reaction to zoledronic acid be prevented? Bourke and colleagues reported that baseline calcium and/or vitamin D intake do not appear to affect rates of acute phase reaction in data pooled from 2 trials of zoledronic acid in postmenopausal women.14 However, patients receiving zoledronic acid had 25-hydroxyvitamin D values > 20 ng/mL 86% of the time, and values > 30 ng/mL 36% of the time. Bourke and colleagues suggest that “coadministration of calcium and vitamin D with zoledronate may not be necessary for individuals not at risk of marked vitamin D deficiency.”14 However, they did not prospectively test this hypothesis.

In our patient, vitamin D deficiency had been identified and treated, nearly achieving 30 ng/mL. The 2020 guidelines for postmenopausal osteoporosis recommend maintaining serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels 30 to 50 ng/mL, advising to supplement with vitamin D3 as needed.5 The 2012 guidelines for osteoporosis in men from the Endocrine Society suggest that men with low vitamin D levels receive vitamin D supplements to raise the level > 30 ng/ml.4

Oral analgesics have been studied for the prevention of adverse effects related to zoledronic acid. Initiating 650 mg acetaminophen 45 minutes before zoledronic acid infusion and then every 6 hours over the next 3 days has been shown to significantly reduce symptoms.15 Acetaminophen or ibuprofen given every 6 hours for 3 days (starting 4 hours after zoledronic acid infusion) has been shown to reduce fever and other symptoms.16

Statins have been shown in vitro to prevent bisphosphonate-induced γϐ T cell activation.17 This has led to studies with various statins, although none have yet shown benefit in vivo. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of postmenopausal women for fluvastatin (single dose of 40 mg or 3 doses of 40 mg, each 24 hours apart) did not prevent acute phase reaction symptoms, nor did it prevent zoledronic acid-induced cytokine release.17 Rosuvastatin 10 mg daily starting 5 days before zoledronic acid treatment and taken for a total of 11 days did not show any difference in fever or pain.18 A protocol for pravastatin has been disseminated, but no study results have been published yet.19

Prophylactic dexamethasone has also been studied. A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral dexamethasone 4 mg at the time of first infusion of zoledronic acid found no significant difference in temperature change or symptom score over the following 3 days.20 Chen and colleagues compared the efficacy of acetaminophen alone vs acetaminophen plus dexamethasone over several days.21 Acetaminophen 500 mg was given on the day of infusion and 4 times daily for 3 to 7 days for both groups, while dexamethasone 4 mg was given for 3 to 7 days. The dexamethasone group reported substantially lower incidence of any acute phase reaction symptoms (34% vs 67%, P = .003). A more recent study by Murdoch and colleagues comparing dexamethasone (4 mg daily for 3 days with the first dose 90 minutes before zoledronic acid infusion) with placebo found that the dexamethasone group had a statistically significant lower mean temperature change and acute phase reaction symptom score.22

Adverse Effect Treatment

Treatment after development of acute phase reaction due to zoledronic acid infusion is generally limited to supportive care and/or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) acetaminophen or dexamethasone, largely based on extrapolation of the noted preventive trials and expert opinion.3,6 Experiencing an acute phase reaction may portend better fracture risk reduction from zoledronic acid, although there is a potential association between acute phase reaction and mortality risk.23,24

Our case was typical for acute phase reaction to zoledronic acid. The patient was already taking rosuvastatin 10 mg daily for hypercholesterolemia as prescribed by his primary care physician. Rosuvastatin was not shown to prevent symptoms, although it was not studied in patients on long-term statin therapy at the time of zoledronic acid infusion.18 The patient was also taking vitamin D3 supplementation and was nearly in the reference range.5 His ED treatment included IV fluids and acetaminophen. Pretreatment (prior to or at the time of zoledronic acid infusion) with acetaminophen or ibuprofen may have prevented his symptoms, or at least lessened them to the point that an ED visit would not have resulted. The endocrinologist who prescribed the zoledronic acid documented a detailed discussion of the adverse effects of zoledronic acid with the patient, and the initial nursing call documents consideration of acute phase reaction. It is unclear whether the persistence of symptoms or worsening of symptoms ultimately led to the ED visit. Because no treatment was offered, it is unknown whether earlier posttreatment with acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or dexamethasone might have prevented his ED visit.

Conclusions

Clinicians who treat patients with osteoporosis should be aware of several key points. First, acute phase reaction symptoms are common with bisphosphonates, especially zoledronic acid infusions. Second, the symptoms are nonspecific but should have a suggestive time course. Third, dexamethasone may be partially protective, but based on the various trials discussed, it likely needs to be given for multiple days (instead of a single dose on the day of infusion). Given that acetaminophen and NSAIDs also seem to be protective (when given for multiple days starting on the day of infusion), both have lower overall adverse effect profiles than dexamethasone, consideration may be given to using either of these prophylactically.6 Dexamethasone could then be prescribed if symptoms are severe or persistent despite the use of acetaminophen or NSAIDs.

1. Choksi P, Gay BL, Reyes-Gastelum D, Haymart MR, Papaleontiou M. Understanding osteoporosis screening practices in men: a nationwide physician survey. Endocr Pract. 2020;26(11):1237-1243. doi:10.4158/EP-2020-0123

2. Yu ZL, Fisher L, Hand J. Osteoporosis screening for male veterans in a resident based primary care clinic at Northport Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Am J Med Qual. 2023;38(5):272.doi:10.1097/JMQ.0000000000000134

3. Eastell R, Rosen CJ, Black DM, Cheung AM, Murad MH, Shoback D. Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: an Endocrine Society* clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(5):1595-1622. doi:10.1210/jc.2019-00221

4. Watts NB, Adler RA, Bilezikian JP, et al. Osteoporosis in men: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(6):1802-1822. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3045

5. Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis – 2020 update. Endocr Pract. 2020;26(suppl 1):1-46. doi:10.4158/GL-2020-0524SUPPL

6. Lim SY, Bolster MB. What can we do about musculoskeletal pain from bisphosphonates?. Cleve Clin J Med. 2018;85(9):675-678. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.18005

7. Reid IR, Gamble GD, Mesenbrink P, Lakatos P, Black DM. Characterization of and risk factors for the acute-phase response after zoledronic acid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(9):4380-4387. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-0597

8. Lu K, Shi Q, Gong YQ, Li C. Association between vitamin D and zoledronate-induced acute-phase response fever risk in osteoporotic patients. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:991913. Published 2022 Oct 10. doi:10.3389/fendo.2022.991913

9. Popp AW, Senn R, Curkovic I, et al. Factors associated with acute-phase response of bisphosphonate-naïve or pretreated women with osteoporosis receiving an intravenous first dose of zoledronate or ibandronate. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(6):1995-2002. doi:10.1007/s00198-017-3992-5

10. Zheng X, Ye J, Zhan Q, et al. Prediction of musculoskeletal pain after the first intravenous zoledronic acid injection in patients with primary osteoporosis: development and evaluation of a new nomogram. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24(1):841. Published 2023 Oct 25. doi:10.1186/s12891-023-06965-y

11. Anastasilakis AD, Polyzos SA, Delaroudis S, et al. The role of cytokines and adipocytokines in zoledronate-induced acute phase reaction in postmenopausal women with low bone mass. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012;77(6):816-822. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2012.04459.x

12. Smrecnik M, Kavcic Trsinar Z, Kocjan T. Adrenal crisis after first infusion of zoledronic acid: a case report. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(7):1675-1678. doi:10.1007/s00198-018-4508-7

13. Kuo B, Koransky A, Vaz Wicks CL. Adrenal crisis as an adverse reaction to zoledronic acid in a patient with primary adrenal insufficiency: a case report and literature review. AACE Clin Case Rep. 2022;9(2):32-34. Published 2022 Dec 17. doi:10.1016/j.aace.2022.12.003

14. Bourke S, Bolland MJ, Grey A, et al. The impact of dietary calcium intake and vitamin D status on the effects of zoledronate. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(1):349-354. doi:10.1007/s00198-012-2117-4

15. Silverman SL, Kriegman A, and Goncalves J, et al. Effect of acetaminophen and fluvastatin on post-dose symptoms following infusion of zoledronic acid. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(8):2337-2345.

16. Wark JD, Bensen W, Recknor C, et al. Treatment with acetaminophen/paracetamol or ibuprofen alleviates post-dose symptoms related to intravenous infusion with zoledronic acid 5 mg. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(2):503-512. doi:10.1007/s00198-011-1563-8

17. Thompson K, Keech F, McLernon DJ, et al. Fluvastatin does not prevent the acute-phase response to intravenous zoledronic acid in post-menopausal women. Bone. 2011;49(1):140-145. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2010.10.177

18. Makras P, Anastasilakis AD, Polyzos SA, Bisbinas I, Sakellariou GT, Papapoulos SE. No effect of rosuvastatin in the zoledronate-induced acute-phase response. Calcif Tissue Int. 2011;88(5):402-408. doi:10.1007/s00223-011-9468-2

19. Liu Q, Han G, Li R, et al. Reduction effect of oral pravastatin on the acute phase response to intravenous zoledronic acid: protocol for a real-world prospective, placebo-controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2022;12(7):e060703. Published 2022 Jul 13. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060703

20. Billington EO, Horne A, Gamble GD, Maslowski K, House M, Reid IR. Effect of single-dose dexamethasone on acute phase response following zoledronic acid: a randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(6):1867-1874. doi:10.1007/s00198-017-3960-0

21. Chen FP, Fu TS, Lin YC, Lin YJ. Addition of dexamethasone to manage acute phase responses following initial zoledronic acid infusion. Osteoporos Int. 2021;32(4):663-670. doi:10.1007/s00198-020-05653-0

22. Murdoch R, Mellar A, Horne AM, et al. Effect of a three-day course of dexamethasone on acute phase response following treatment with zoledronate: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2023;38(5):631-638. doi:10.1002/jbmr.4802

23. Black DM, Reid IR, Napoli N, et al. The interaction of acute-phase reaction and efficacy for osteoporosis after zoledronic acid: HORIZON pivotal fracture trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2022;37(1):21-28. doi:10.1002/jbmr.4434

24. Lu K, Wu YM, Shi Q, Gong YQ, Zhang T, Li C. The impact of acute-phase reaction on mortality and re-fracture after zoledronic acid in hospitalized elderly osteoporotic fracture patients. Osteoporos Int. 2023;34(9):1613-1623. doi:10.1007/s00198-023-06803-w

1. Choksi P, Gay BL, Reyes-Gastelum D, Haymart MR, Papaleontiou M. Understanding osteoporosis screening practices in men: a nationwide physician survey. Endocr Pract. 2020;26(11):1237-1243. doi:10.4158/EP-2020-0123

2. Yu ZL, Fisher L, Hand J. Osteoporosis screening for male veterans in a resident based primary care clinic at Northport Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Am J Med Qual. 2023;38(5):272.doi:10.1097/JMQ.0000000000000134

3. Eastell R, Rosen CJ, Black DM, Cheung AM, Murad MH, Shoback D. Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: an Endocrine Society* clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(5):1595-1622. doi:10.1210/jc.2019-00221

4. Watts NB, Adler RA, Bilezikian JP, et al. Osteoporosis in men: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(6):1802-1822. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3045

5. Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis – 2020 update. Endocr Pract. 2020;26(suppl 1):1-46. doi:10.4158/GL-2020-0524SUPPL

6. Lim SY, Bolster MB. What can we do about musculoskeletal pain from bisphosphonates?. Cleve Clin J Med. 2018;85(9):675-678. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.18005

7. Reid IR, Gamble GD, Mesenbrink P, Lakatos P, Black DM. Characterization of and risk factors for the acute-phase response after zoledronic acid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(9):4380-4387. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-0597

8. Lu K, Shi Q, Gong YQ, Li C. Association between vitamin D and zoledronate-induced acute-phase response fever risk in osteoporotic patients. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:991913. Published 2022 Oct 10. doi:10.3389/fendo.2022.991913

9. Popp AW, Senn R, Curkovic I, et al. Factors associated with acute-phase response of bisphosphonate-naïve or pretreated women with osteoporosis receiving an intravenous first dose of zoledronate or ibandronate. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(6):1995-2002. doi:10.1007/s00198-017-3992-5

10. Zheng X, Ye J, Zhan Q, et al. Prediction of musculoskeletal pain after the first intravenous zoledronic acid injection in patients with primary osteoporosis: development and evaluation of a new nomogram. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24(1):841. Published 2023 Oct 25. doi:10.1186/s12891-023-06965-y

11. Anastasilakis AD, Polyzos SA, Delaroudis S, et al. The role of cytokines and adipocytokines in zoledronate-induced acute phase reaction in postmenopausal women with low bone mass. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012;77(6):816-822. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2012.04459.x

12. Smrecnik M, Kavcic Trsinar Z, Kocjan T. Adrenal crisis after first infusion of zoledronic acid: a case report. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(7):1675-1678. doi:10.1007/s00198-018-4508-7

13. Kuo B, Koransky A, Vaz Wicks CL. Adrenal crisis as an adverse reaction to zoledronic acid in a patient with primary adrenal insufficiency: a case report and literature review. AACE Clin Case Rep. 2022;9(2):32-34. Published 2022 Dec 17. doi:10.1016/j.aace.2022.12.003

14. Bourke S, Bolland MJ, Grey A, et al. The impact of dietary calcium intake and vitamin D status on the effects of zoledronate. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(1):349-354. doi:10.1007/s00198-012-2117-4

15. Silverman SL, Kriegman A, and Goncalves J, et al. Effect of acetaminophen and fluvastatin on post-dose symptoms following infusion of zoledronic acid. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(8):2337-2345.

16. Wark JD, Bensen W, Recknor C, et al. Treatment with acetaminophen/paracetamol or ibuprofen alleviates post-dose symptoms related to intravenous infusion with zoledronic acid 5 mg. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(2):503-512. doi:10.1007/s00198-011-1563-8

17. Thompson K, Keech F, McLernon DJ, et al. Fluvastatin does not prevent the acute-phase response to intravenous zoledronic acid in post-menopausal women. Bone. 2011;49(1):140-145. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2010.10.177

18. Makras P, Anastasilakis AD, Polyzos SA, Bisbinas I, Sakellariou GT, Papapoulos SE. No effect of rosuvastatin in the zoledronate-induced acute-phase response. Calcif Tissue Int. 2011;88(5):402-408. doi:10.1007/s00223-011-9468-2

19. Liu Q, Han G, Li R, et al. Reduction effect of oral pravastatin on the acute phase response to intravenous zoledronic acid: protocol for a real-world prospective, placebo-controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2022;12(7):e060703. Published 2022 Jul 13. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060703

20. Billington EO, Horne A, Gamble GD, Maslowski K, House M, Reid IR. Effect of single-dose dexamethasone on acute phase response following zoledronic acid: a randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(6):1867-1874. doi:10.1007/s00198-017-3960-0

21. Chen FP, Fu TS, Lin YC, Lin YJ. Addition of dexamethasone to manage acute phase responses following initial zoledronic acid infusion. Osteoporos Int. 2021;32(4):663-670. doi:10.1007/s00198-020-05653-0

22. Murdoch R, Mellar A, Horne AM, et al. Effect of a three-day course of dexamethasone on acute phase response following treatment with zoledronate: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2023;38(5):631-638. doi:10.1002/jbmr.4802

23. Black DM, Reid IR, Napoli N, et al. The interaction of acute-phase reaction and efficacy for osteoporosis after zoledronic acid: HORIZON pivotal fracture trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2022;37(1):21-28. doi:10.1002/jbmr.4434

24. Lu K, Wu YM, Shi Q, Gong YQ, Zhang T, Li C. The impact of acute-phase reaction on mortality and re-fracture after zoledronic acid in hospitalized elderly osteoporotic fracture patients. Osteoporos Int. 2023;34(9):1613-1623. doi:10.1007/s00198-023-06803-w

Evaluating an Academic Hospitalist Service

Improving quality while reducing costs remains important for hospitals across the United States, including the approximately 150 hospitals that are part of the Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system.[1, 2] The field of hospital medicine has grown rapidly, leading to predictions that the majority of inpatient care in the United States eventually will be delivered by hospitalists.[3, 4] In 2010, 57% of US hospitals had hospitalists on staff, including 87% of hospitals with 200 beds,[5] and nearly 80% of VA hospitals.[6]

The demand for hospitalists within teaching hospitals has grown in part as a response to the mandate to reduce residency work hours.[7] Furthermore, previous research has found that hospitalist care is associated with modest reductions in length of stay (LOS) and weak but inconsistent differences in quality.[8] The educational effect of hospitalists has been far less examined. The limited number of studies published to date suggests that hospitalists may improve resident learning and house‐officer satisfaction in academic medical centers and community teaching hospitals[9, 10, 11] and provide positive experiences for medical students12,13; however, Wachter et al reported no significant changes in clinical outcomes or patient, faculty, and house‐staff satisfaction in a newly designed hospital medicine service in San Francisco.[14] Additionally, whether using hospitalists influences nurse‐physician communication[15] is unknown.

Recognizing the limited and sometimes conflicting evidence about the hospitalist model, we report the results of a 3‐year quasi‐experimental evaluation of the experience at our medical center with academic hospitalists. As part of a VA Systems Redesign Improvement Capability Grantknown as the Hospital Outcomes Program of Excellence (HOPE) Initiativewe created a hospitalist‐based medicine team focused on quality improvement, medical education, and patient outcomes.

METHODS

Setting and Design

The main hospital of the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, located in Ann Arbor, Michigan, operates 105 acute‐care beds and 40 extended‐care beds. At the time of this evaluation, the medicine service consisted of 4 internal medicine teamsGold, Silver, Burgundy, and Yelloweach of which was responsible for admitting patients on a rotating basis every fourth day, with limited numbers of admissions occurring between each team's primary admitting day. Each team is led by an attending physician, a board‐certified (or board‐eligible) general internist or subspecialist who is also a faculty member at the University of Michigan Medical School. Each team has a senior medical resident, 2 to 3 interns, and 3 to 5 medical students (mostly third‐year students). In total, there are approximately 50 senior medical residents, 60 interns, and 170 medical students who rotate through the medicine service each year. Traditional rounding involves the medical students and interns receiving sign‐out from the overnight team in the morning, then pre‐rounding on each patient by obtaining an interval history, performing an exam, and checking any test results. A tentative plan of care is formed with the senior medical resident, usually by discussing each patient very quickly in the team room. Attending rounds are then conducted, with the physician team visiting each patient one by one to review and plan all aspects of care in detail. When time allows, small segments of teaching may occur during these attending work rounds. This system had been in place for >20 years.

Resulting in part from a grant received from the VA Systems Redesign Central Office (ie, the HOPE Initiative), the Gold team was modified in July 2009 and an academic hospitalist (S.S.) was assigned to head this team. Specific hospitalists were selected by the Associate Chief of Medicine (S.S.) and the Chief of Medicine (R.H.M.) to serve as Gold team attendings on a regular basis. The other teams continued to be overseen by the Chief of Medicine, and the Gold team remained within the medicine service. Characteristics of the Gold and nonGold team attendings can be found in Table 1. The 3 other teams initially were noninterventional concurrent control groups. However, during the second year of the evaluation, the Silver team adopted some of the initiatives as a result of the preliminary findings observed on Gold. Specifically, in the second year of the evaluation, approximately 42% of attendings on the Silver team were from the Gold team. This increased in the third year to 67% of coverage by Gold team attendings on the Silver team. The evaluation of the Gold team ended in June 2012.

| Characteristic | Gold Team | Non‐Gold Teams |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of attendings | 14 | 57 |

| Sex, % | ||

| Male | 79 | 58 |

| Female | 21 | 42 |

| Median years postresidency (range) | 10 (130) | 7 (141) |

| Subspecialists, % | 14 | 40 |

| Median days on service per year (range) | 53 (574) | 30 (592) |

The clinical interventions implemented on the Gold team were quality‐improvement work and were therefore exempt from institutional review board review. Human subjects' approval was, however, received to conduct interviews as part of a qualitative assessment.

Clinical Interventions

Several interventions involving the clinical care delivered were introduced on the Gold team, with a focus on improving communication among healthcare workers (Table 2).

| Clinical Interventions | Educational Interventions |

|---|---|

| Modified structure of attending rounds | Modified structure of attending rounds |

| Circle of Concern rounds | Attending reading list |

| Clinical Care Coordinator | Nifty Fifty reading list for learners |

| Regular attending team meetings | Website to provide expectations to learners |

| Two‐month per year commitment by attendings |

Structure of Attending Rounds

The structure of morning rounds was modified on the Gold team. Similar to the traditional structure, medical students and interns on the Gold team receive sign‐out from the overnight team in the morning. However, interns and students may or may not conduct pre‐rounds on each patient. The majority of time between sign‐out and the arrival of the attending physician is spent on work rounds. The senior resident leads rounds with the interns and students, discussing each patient while focusing on overnight events and current symptoms, new physical‐examination findings, and laboratory and test data. The plan of care to be presented to the attending is then formulated with the senior resident. The attending physician then leads Circle of Concern rounds with an expanded team, including a charge nurse, a clinical pharmacist, and a nurse Clinical Care Coordinator. Attending rounds tend to use an E‐AP format: significant Events overnight are discussed, followed by an Assessment & Plan by problem for the top active problems. Using this model, the attendings are able to focus more on teaching and discussing the patient plan than in the traditional model (in which the learner presents the details of the subjective, objective, laboratory, and radiographic data, with limited time left for the assessment and plan for each problem).

Circle of Concern Rounds

Suzanne Gordon described the Circle of Concern in her book Nursing Against the Odds.[16] From her observations, she noted that physicians typically form a circle to discuss patient care during rounds. The circle expands when another physician joins the group; however, the circle does not similarly expand to include nurses when they approach the group. Instead, nurses typically remain on the periphery, listening silently or trying to communicate to physicians' backs.[16] Thus, to promote nurse‐physician communication, Circle of Concern rounds were formally introduced on the Gold team. Each morning, the charge nurse rounds with the team and is encouraged to bring up nursing concerns. The inpatient clinical pharmacist is also included 2 to 3 times per week to help provide education to residents and students and perform medication reconciliation.

Clinical Care Coordinator

The role of the nurse Clinical Care Coordinatoralso introduced on the Gold teamis to provide continuity of patient care, facilitate interdisciplinary communication, facilitate patient discharge, ensure appropriate appointments are scheduled, communicate with the ambulatory care service to ensure proper transition between inpatient and outpatient care, and help educate residents and students on VA procedures and resources.

Regular Gold Team Meetings

All Gold team attendings are expected to dedicate 2 months per year to inpatient service (divided into half‐month blocks), instead of the average 1 month per year for attendings on the other teams. The Gold team attendings, unlike the other teams, also attend bimonthly meetings to discuss strategies for running the team.

Educational Interventions

Given the high number of learners on the medicine service, we wanted to enhance the educational experience for our learners. We thus implemented various interventions, in addition to the change in the structure of rounds, as described below.

Reading List for Learners: The Nifty Fifty

Because reading about clinical medicine is an integral part of medical education, we make explicit our expectation that residents and students read something clinically relevant every day. To promote this, we have provided a Nifty Fifty reading list of key articles. The PDF of each article is provided, along with a brief summary highlighting key points.

Reading List for Gold Attendings and Support Staff

To promote a common understanding of leadership techniques, management books are provided to Gold attending physicians and other members of the team (eg, Care Coordinator, nurse researcher, systems redesign engineer). One book is discussed at each Gold team meeting (Table 3), with participants taking turns leading the discussion.

| Book Title | Author(s) |

|---|---|

| The One Minute Manager | Ken Blanchard and Spencer Johnson |

| Good to Great | Jim Collins |

| Good to Great and the Social Sectors | Jim Collins |

| The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right | Atul Gawande |

| The Five Dysfunctions of a Team: A Leadership Fable | Patrick Lencioni |

| Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In | Roger Fisher, William Ury, and Bruce Patton |

| The Effective Executive: The Definitive Guide to Getting the Right Things Done | Peter Drucker |

| A Sense of Urgency | John Kotter |

| The Power of Positive Deviance: How Unlikely Innovators Solve the World's Toughest Problems | Richard Pascale, Jerry Sternin, and Monique Sternin |

| On the Mend: Revolutionizing Healthcare to Save Lives and Transform the Industry | John Toussaint and Roger Gerard |

| Outliers: The Story of Success | Malcolm Gladwell |

| Nursing Against the Odds: How Health Care Cost Cutting, Media Stereotypes, and Medical Hubris Undermine Nurses and Patient Care | Suzanne Gordon |

| How the Mighty Fall and Why Some Companies Never Give In | Jim Collins |

| What the Best College Teachers Do | Ken Bain |

| The Creative Destruction of Medicine | Eric Topol |

| What Got You Here Won't Get You There: How Successful People Become Even More Successful! | Marshall Goldsmith |

Website

A HOPE Initiative website was created (

Qualitative Assessment

To evaluate our efforts, we conducted a thorough qualitative assessment during the third year of the program. A total of 35 semistructured qualitative interviews were conducted with patients and staff from all levels of the organization, including senior leadership. The qualitative assessment was led by research staff from the Center for Clinical Management Research, who were minimally involved in the redesign effort and could provide an unbiased view of the initiative. Field notes from the semistructured interviews were analyzed, with themes developed using a descriptive approach and through discussion by a multidisciplinary team, which included building team consensus on findings that were supported by clear evidence in the data.[17]

Quantitative Outcome Measures

Clinical Outcomes

To determine if our communication and educational interventions had an impact on patient care, we used hospital administrative data to evaluate admission rates, LOS, and readmission rates for all 4 of the medicine teams. Additional clinical measures were assessed as needed. For example, we monitored the impact of the clinical pharmacist during a 4‐week pilot study by asking the Clinical Care Coordinator to track the proportion of patient encounters (n=170) in which the clinical pharmacist changed management or provided education to team members. Additionally, 2 staff surveys were conducted. The first survey focused on healthcare‐worker communication and was given to inpatient nurses and physicians (including attendings, residents, and medical students) who were recently on an inpatient medical service rotation. The survey included questions from previously validated communication measures,[18, 19, 20] as well as study‐specific questions. The second survey evaluated the new role of the Clinical Care Coordinator (Appendix). Both physicians and nurses who interacted with the Gold team's Clinical Care Coordinator were asked to complete this survey.

Educational Outcomes

To assess the educational interventions, we used learner evaluations of attendings, by both residents and medical students, and standardized internal medicine National Board of Medical Examiners Subject Examination (or shelf) scores for third‐year medical students. A separate evaluation of medical student perceptions of the rounding structure introduced on the Gold team using survey design has already been published.[21]

Statistical Analyses

Data from all sources were analyzed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Outliers for the LOS variable were removed from the analysis. Means and frequency distributions were examined for all variables. Student t tests and [2] tests of independence were used to compare data between groups. Multivariable linear regression models controlling for time (preintervention vs postintervention) were used to assess the effect of the HOPE Initiative on patient LOS and readmission rates. In all cases, 2‐tailed P values of 0.05 or less were considered statistically significant.

Role of the Funding Source

The VA Office of Systems Redesign provided funding but was not involved in the design or conduct of the study, data analysis, or preparation of the manuscript.

RESULTS

Clinical Outcomes

Patient Outcomes

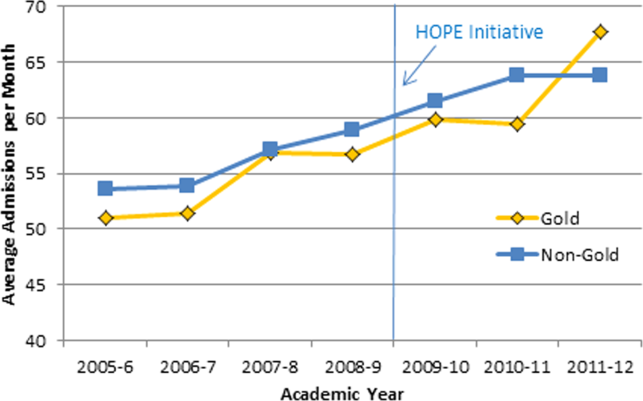

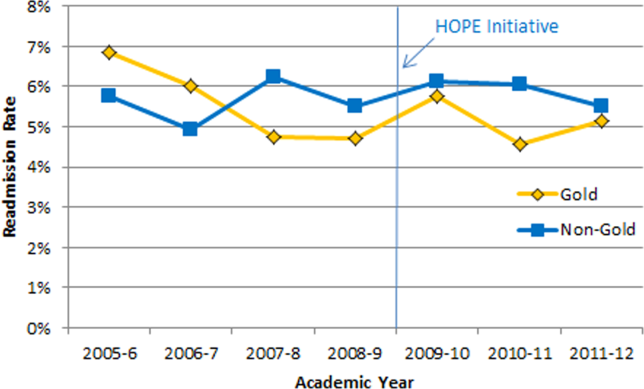

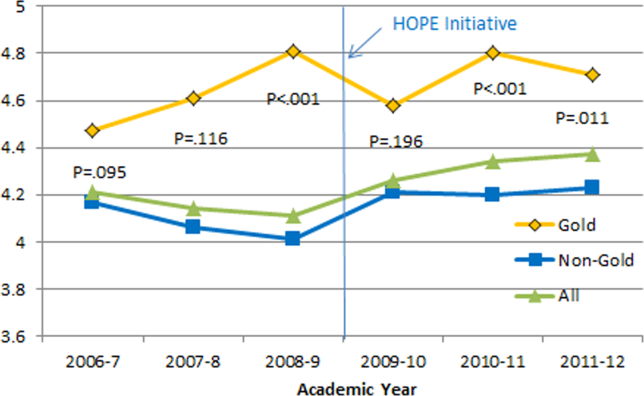

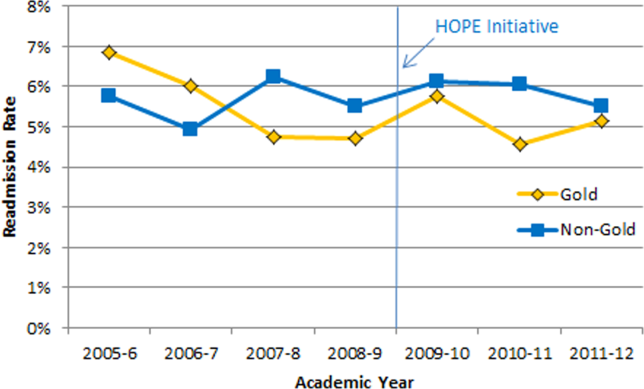

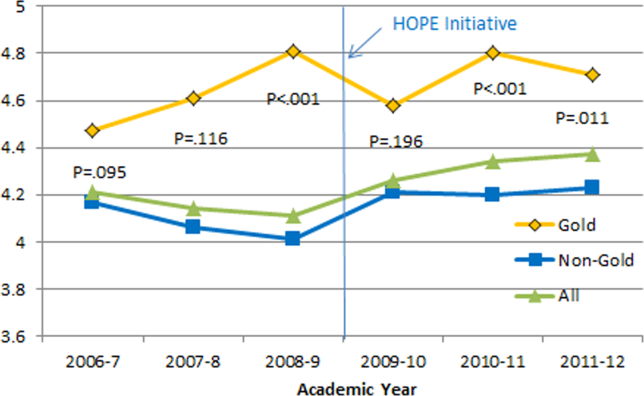

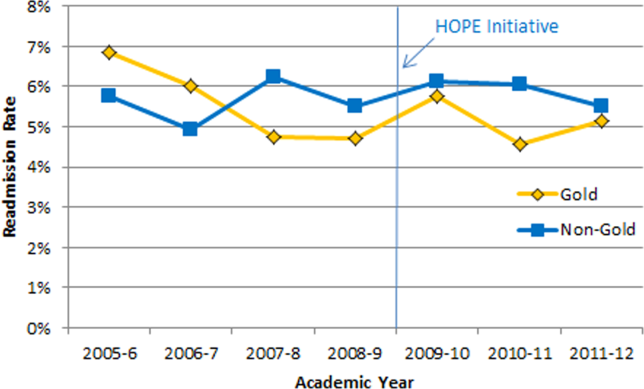

Our multivariable linear regression analysis, controlling for time, showed a significant reduction in LOS of approximately 0.3 days on all teams after the HOPE Initiative began (P=0.004). There were no significant differences between the Gold and non‐Gold teams in the multivariate models when controlling for time for any of the patient‐outcome measures. The number of admissions increased for all 4 medical teams (Figure 1), but, as shown in Figures 2 and 3, the readmission rates for all teams remained relatively stable over this same period of time.

Clinical Pharmacist on Gold Team Rounds

The inpatient clinical pharmacist changed the management plan for 22% of the patients seen on rounds. Contributions from the clinical pharmacist included adjusting the dosing of ordered medication and correcting medication reconciliation. Education and pharmaceutical information was provided to the team in another 6% of the 170 consecutive patient encounters evaluated.

Perception of Circle of Concern Rounds

Circle of Concern rounds were generally well‐received by both nurses and physicians. In a healthcare‐worker communication survey, completed by 38 physicians (62% response rate) and 48 nurses (54% response rate), the majority of both physicians (83%) and nurses (68%) felt Circle of Concern rounds improved communication.

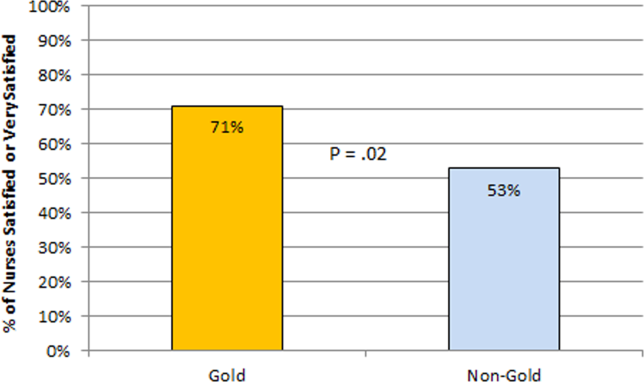

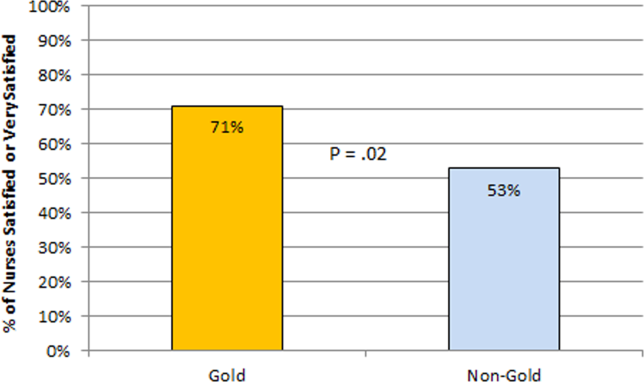

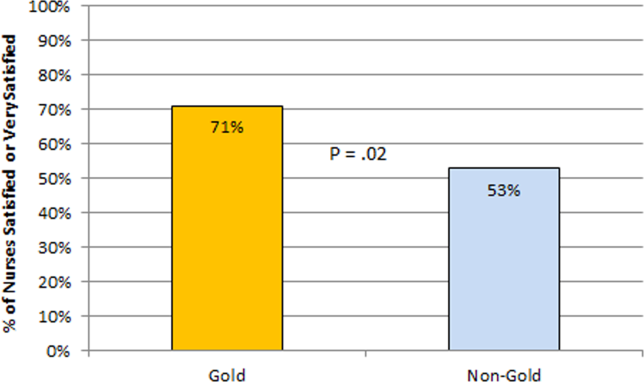

Nurse Perception of Communication

The healthcare‐worker communication survey asked inpatient nurses to rate communication between nurses and physicians on each of the 4 medicine teams. Significantly more nurses were satisfied with communication with the Gold team (71%) compared with the other 3 medicine teams (53%; P=0.02) (Figure 4).

Perception of the Clinical Care Coordinator

In total, 20 physicians (87% response rate) and 10 nurses (56% response rate) completed the Clinical Care Coordinator survey. The physician results were overwhelmingly positive: 100% were satisfied or very satisfied with the role; 100% felt each team should have a Clinical Care Coordinator; and 100% agreed or strongly agreed that the Clinical Care Coordinator ensures that appropriate follow‐up is arranged, provides continuity of care, assists with interdisciplinary communication, and helps facilitate discharge. The majority of nurses was also satisfied or very satisfied with the Clinical Care Coordinator role and felt each team should have one.

Educational Outcomes

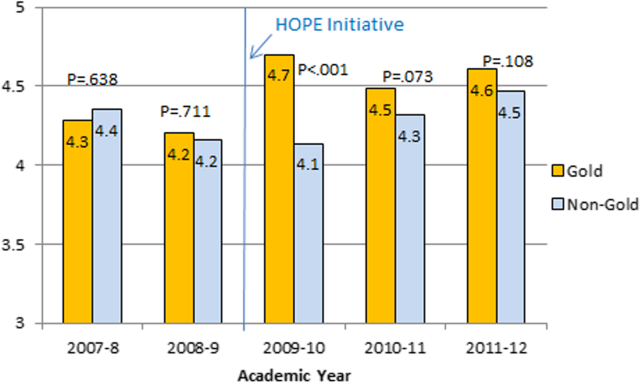

House Officer Evaluation of Attendings

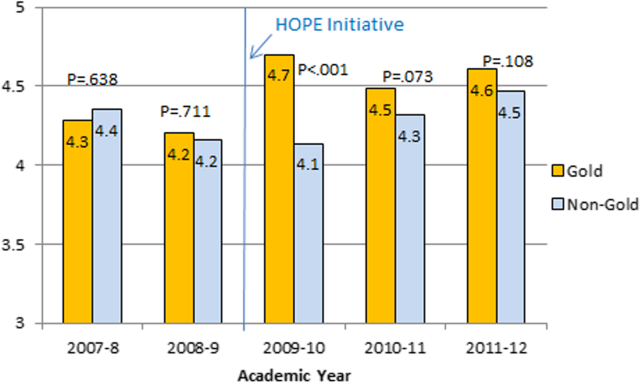

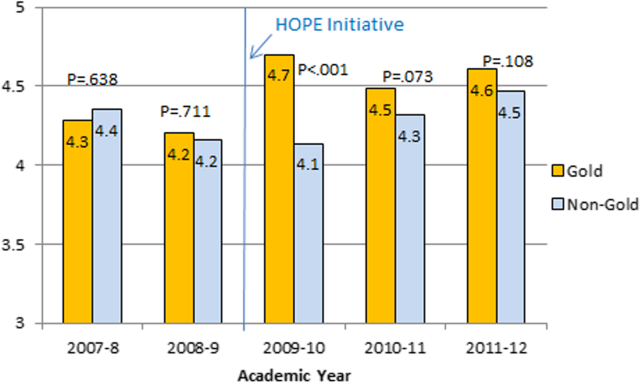

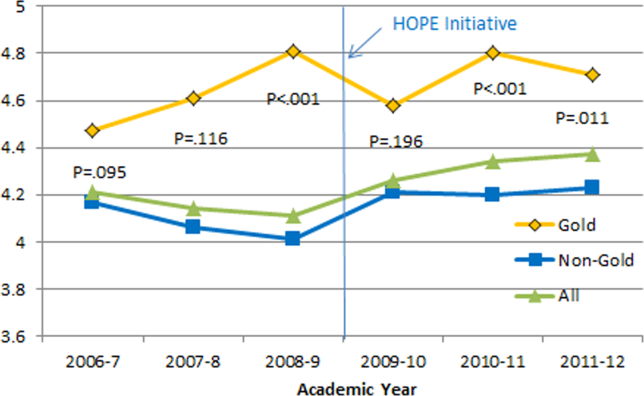

Monthly evaluations of attending physicians by house officers (Figure 5) revealed that prior to the HOPE Initiative, little differences were observed between teams, as would be expected because attending assignment was largely random. After the intervention date of July 2009, however, significant differences were noted, with Gold team attendings receiving significantly higher teaching evaluations immediately after the introduction of the HOPE Initiative. Although ratings for Gold attendings remained more favorable, the difference was no longer statistically significant in the second and third year of the initiative, likely due to Gold attendings serving on other medicine teams, which contributed to an improvement in ratings of all attendings.

Medical Student Evaluation of Attendings

Monthly evaluations of attending physicians by third‐year medical students (Figure 6) revealed differences between the Gold attendings and all others, with the attendings that joined the Gold team in 2009 receiving higher teaching evaluations even before the HOPE Initiative started. However, this difference remained statistically significant in years 2 and 3 postinitiative, despite the addition of 4 new junior attendings.

Medical Student Medicine Shelf Scores

The national average on the shelf exam, which reflects learning after the internal medicine third‐year clerkship, has ranged from 75 to 78 for the past several years, with University of Michigan students averaging significantly higher scores prior to and after the HOPE Initiative. However, following the HOPE Initiative, third‐year medical students on the Gold team scored significantly higher on the shelf exam compared with their colleagues on the non‐Gold teams (84 vs 82; P=0.006). This difference in the shelf exam scores, although small, is statistically significant. It represents a measurable improvement in shelf scores in our system and demonstrates the potential educational benefit for the students. Over this same time period, scores on the United States Medical Licensing Exam, given to medical students at the beginning of their third year, remained stable (233 preHOPE Initiative; 234 postHOPE Initiative).

Qualitative Assessment

Qualitative data collected as part of our evaluation of the HOPE Initiative also suggested that nurse‐physician communication had improved since the start of the project. In particular, they reported positively on the Gold team in general, the Circle of Concern rounds, and the Clinical Care Coordinator (Table 4).

| Staff Type | Statement1 |

|---|---|

| |

| Nurse | [Gold is] above and beyond other [teams]. Other teams don't run as smoothly. |

| Nurse | There has been a difference in communication [on Gold]. You can tell the difference in how they communicate with staff. We know the Clinical Care Coordinator or charge nurse is rounding with that team, so there is more communication. |

| Nurse | The most important thing that has improved communication is the Circle of Concern rounds. |

| Physician | [The Gold Clinical Care Coordinator] expedites care, not only what to do but who to call. She can convey the urgency. On rounds she is able to break off, put in an order, place a call, talk to a patient. Things that we would do at 11 AM she gets to at 9 AM. A couple of hours may not seem like much, but sometimes it can make the difference between things happening that day instead of the next. |

| Physician | The Clinical Care Coordinator is completely indispensable. Major benefit to providing care to Veterans. |

| Physician | I like to think Gold has lifted all of the teams to a higher level. |

| Medical student | It may be due to personalities vs the Gold [team] itself, but there is more emphasis on best practices. Are we following guidelines even if it is not related to the primary reason for admission? |

| Medical student | Gold is very collegial and nurses/physicians know one another by name. Physicians request rather than order; this sets a good example to me on how to approach the nurses. |

| Chief resident | [Gold attendings] encourage senior residents to take charge and run the team, although the attending is there for back‐up and support. This provides great learning for the residents. Interns and medical students also are affected because they have to step up their game as well. |

DISCUSSION

Within academic medical centers, hospitalists are expected to care for patients, teach, and help improve the quality and efficiency of hospital‐based care.[7] The Department of Veterans Affairs runs the largest integrated healthcare system in the United States, with approximately 80% of VA hospitals having hospital medicine programs. Overall, one‐third of US residents perform part of their residency training at a VA hospital.[22, 23] Thus, the effects of a system‐wide change at a VA hospital may have implications throughout the country. We studied one such intervention. Our primary findings are that we were able to improve communication and learner education with minimal effects on patient outcomes. While overall LOS decreased slightly postintervention, after taking into account secular trends, readmission rates did not.

We are not the first to evaluate a hospital medicine team using a quasi‐experimental design. For example, Meltzer and colleagues evaluated a hospitalist program at the University of Chicago Medical Center and found that, by the second year of operation, hospitalist care was associated with significantly shorter LOS (0.49 days), reduced costs, and decreased mortality.[24] Auerbach also evaluated a newly created hospital medicine service, finding decreased LOS (0.61 days), lower costs, and lower risk of mortality by the second year of the program.[25]

Improving nurse‐physician communication is considered important for avoiding medical error,[26] yet there has been limited empirical study of methods to improve communication within the medical profession.[27] Based both on our surveys and qualitative interviews, healthcare‐worker communication appeared to improve on the Gold team during the study. A key component of this improvement is likely related to instituting Circle of Concern rounds, in which nurses joined the medical team during attending rounds. Such an intervention likely helped to address organizational silence[28] and enhance the psychological safety of the nursing staff, because the attending physician was proactive about soliciting the input of nurses during rounds.[29] Such leader inclusivenesswords and deeds exhibited by leaders that invite and appreciate others' contributionscan aid interdisciplinary teams in overcoming the negative effects of status differences, thereby promoting collaboration.[29] The inclusion of nurses on rounds is also relationship‐building, which Gotlib Conn and colleagues found was important to improved interprofessional communication and collaboration.[30] In the future, using a tool such as the Teamwork Effectiveness Assessment Module (TEAM) developed by the American Board of Internal Medicine[31] could provide further evaluation of the impact on interprofessional teamwork and communication.

The focus on learner education, though evaluated in prior studies, is also novel. One previous survey of medical students showed that engaging students in substantive discussions is associated with greater student satisfaction.[32] Another survey of medical students found that attendings who were enthusiastic about teaching, inspired confidence in knowledge and skills, provided useful feedback, and encouraged increased student responsibility were viewed as more effective teachers.[33] No previous study that we are aware of, however, has looked at actual educational outcomes, such as shelf scores. The National Board of Medical Examiners reports that the Medicine subject exam is scaled to have a mean of 70 and a standard deviation of 8.[34] Thus, a mean increase in score of 2 points is small, but not trivial. This shows improvement in a hard educational outcome. Additionally, 2 points, although small in the context of total score and standard deviation, may make a substantial difference to an individual student in terms of overall grade, and, thus, residency applications. Our finding that third‐year medical students on the Gold team performed significantly better than University of Michigan third‐year medical students on other teams is an intriguing finding that warrants confirmation. On the other hand, this finding is consistent with a previous report evaluating learner satisfaction in which Bodnar et al found improved ratings of quantity and quality of teaching on teams with a nontraditional structure (Gold team).[21] Moreover, despite relatively few studies, the reason underlying the educational benefit of hospitalists should surprise few. The hospitalist model ensures that learners are supervised by physicians who are experts in the care of hospitalized patients.[35] Hospitalists hired at teaching hospitals to work on services with learners are generally chosen because they possess superior educational skills.[7]

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of the following limitations. First, our study focused on a single academically affiliated VA hospital. As other VA hospitals are pursuing a similar approach (eg, the Houston and Detroit VA medical centers), replicating our results will be important. Second, the VA system, although the largest integrated healthcare system in the United States, has unique characteristicssuch as an integrated electronic health record and predominantly male patient populationthat may make generalizations to the larger US healthcare system challenging. Third, there was a slightly lower response rate among nurses on a few of the surveys to evaluate our efforts; however, this rate of response is standard at our facility. Finally, our evaluation lacks an empirical measure of healthcare‐worker communication, such as incident reports.

Despite these limitations, our results have important implications. Using both quantitative and qualitative assessment, we found that academic hospitalists have the ability to improve healthcare‐worker communication and enhance learner education without increasing LOS. These findings are directly applicable to VA medical centers and potentially applicable to other academic medical centers.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Milisa Manojlovich, PhD, RN, Edward Kennedy, MS, and Andrew Hickner, MSI, for help with preparation of this manuscript.