User login

Repair of a Large Full-Thickness Conchal Bowl Defect

Repair of a Large Full-Thickness Conchal Bowl Defect

Practice Gap

Large full-thickness conchal bowl defects often pose a reconstructive challenge. Maintaining the shape and structural integrity of the concha is fundamental for optimal cosmetic and functional outcomes. Prior reports have suggested wedge excisions, composite grafts, interpolation flaps with or without cartilage struts, and hinge flaps as possible options for reconstruction.1-3 However, patients with large defects who prefer single-stage reconstruction procedures present a unique challenge. Herein, we describe a single-stage full-thickness hinge flap technique for a large conchal bowl defect.

The Technique

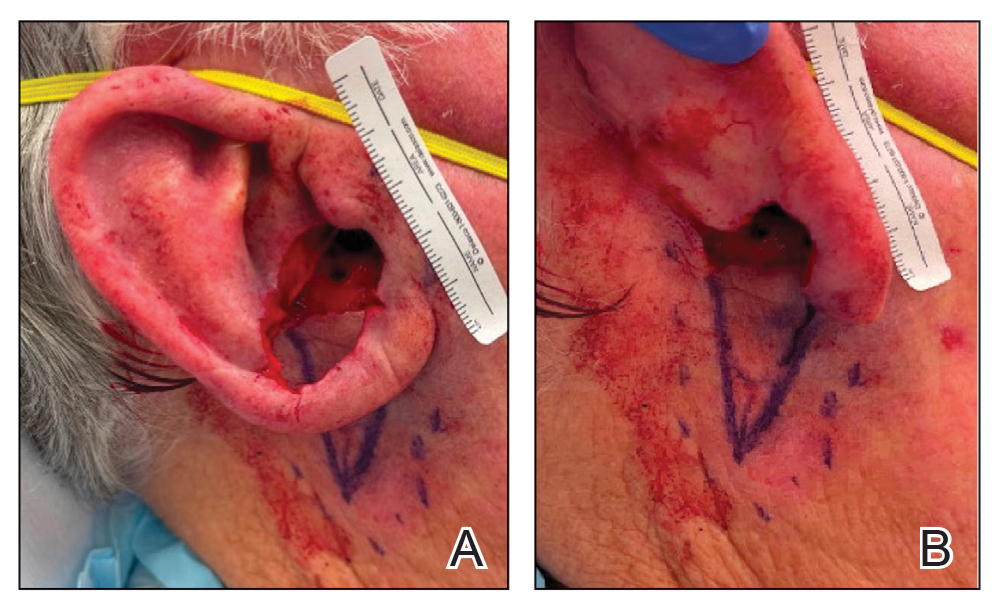

A 77-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic by an outside dermatologist for Mohs micrographic surgery of a biopsy-proven cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma on the right conchal bowl measuring 1.1×2.1 cm and extending to the edge of the external auditory canal (EAC). The excision was performed that same day and was completed in 2 stages, achieving negative margins and resulting in a full-thickness defect measuring 2.0×3.6 cm that included the posterior auricular sulcus, cavum, antitragus, and proximal EAC (Figure 1). The patient requested a single-stage procedure but emphasized that his main priority was an optimal cosmetic outcome.

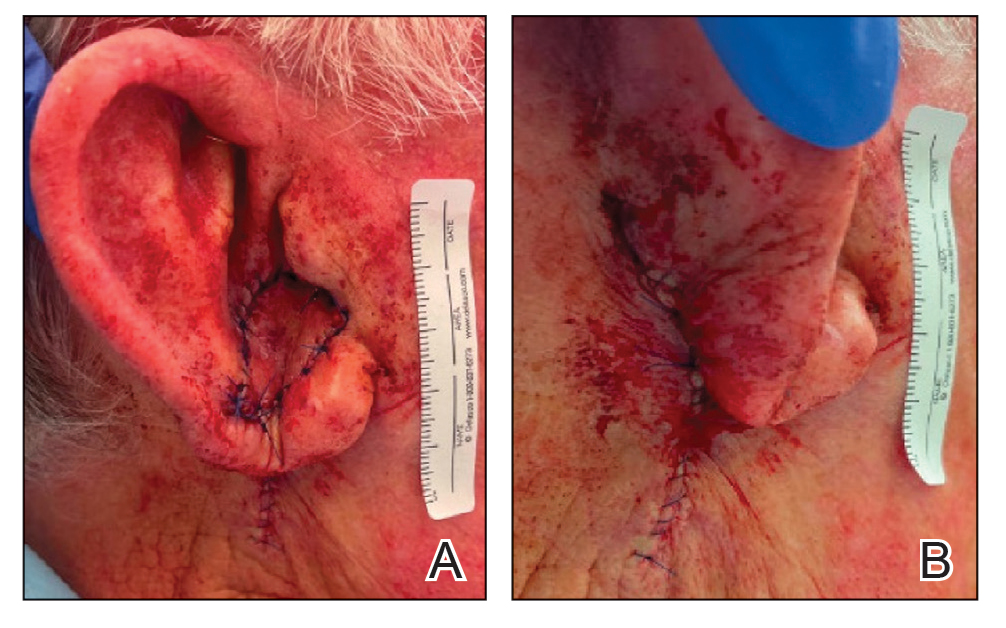

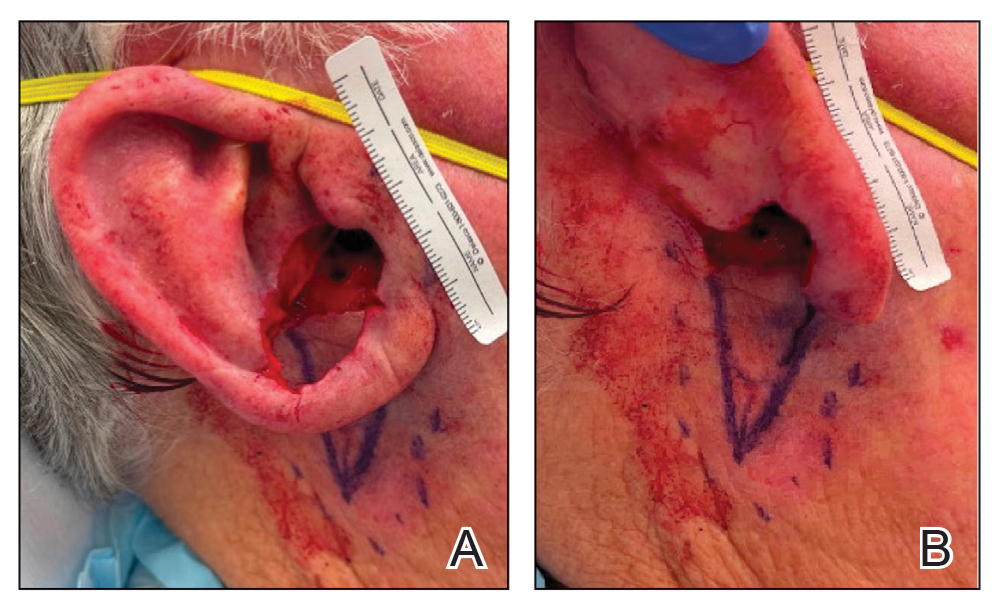

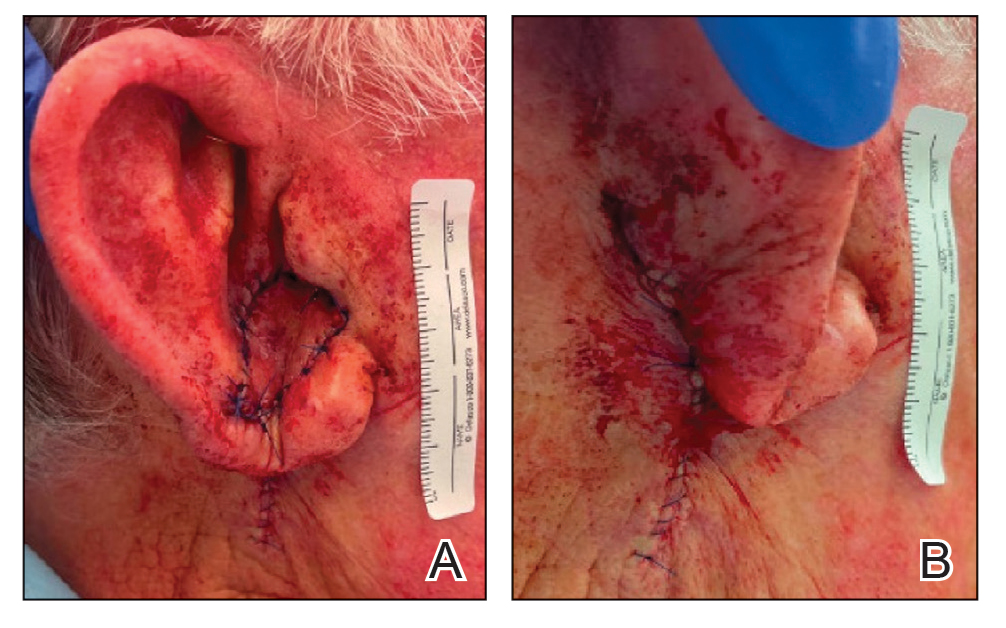

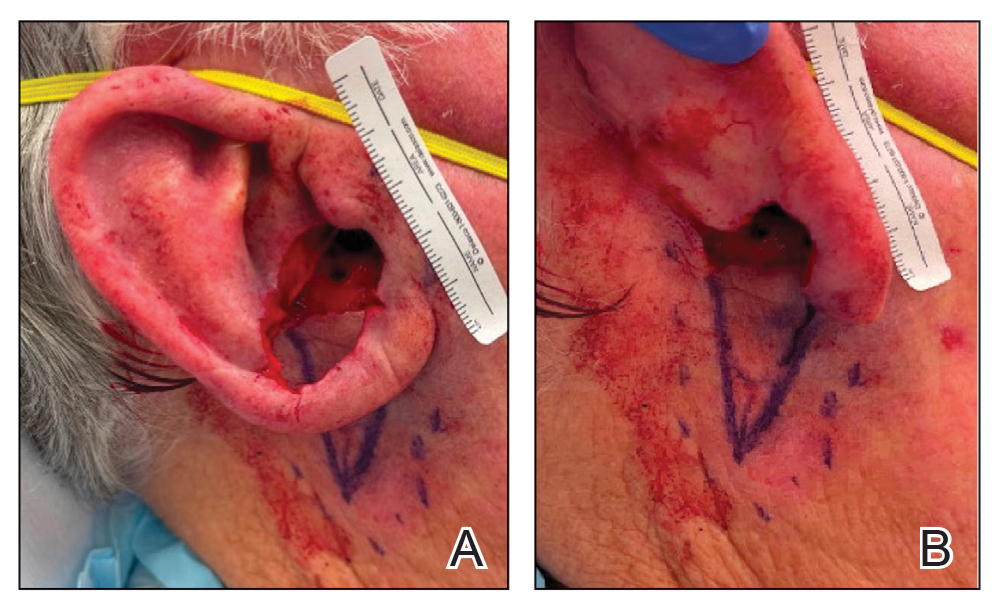

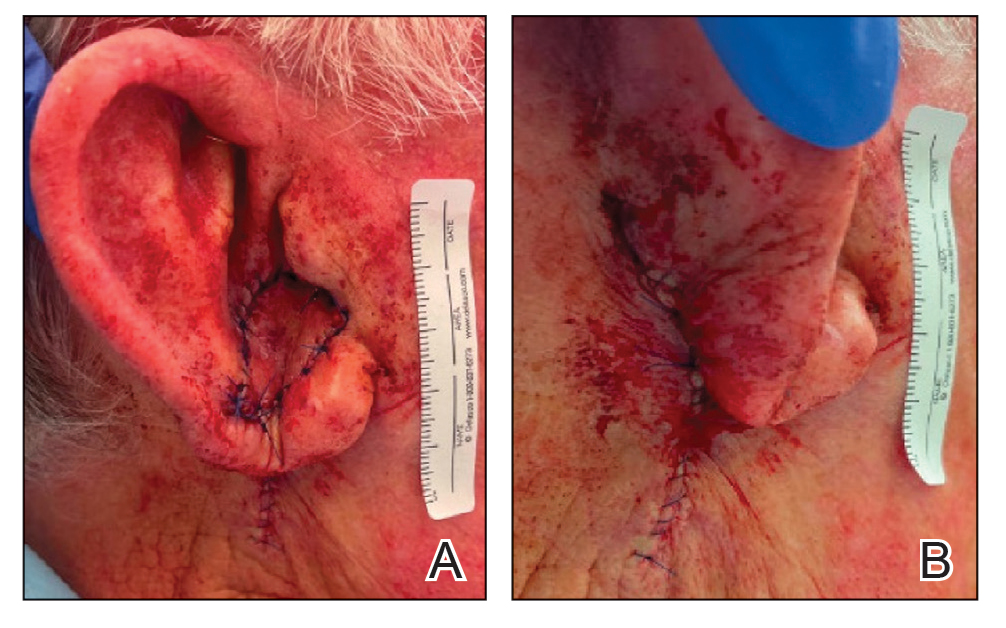

To repair this large defect, a full-thickness hinge flap with Burow graft was performed. The hinge-type flap was designed in a triangular fashion emanating at the posterior auricular sulcus adjacent to the posterior aspect of the defect and extending down the lateral neck (Figure 2). The flap was incised and the surrounding tissue was undermined, maintaining a robust pedicle in the center of its body on the superolateral neck. The flap was passed through the posterior aspect of the full-thickness defect and was secured in place with 4-0 polyglactin sutures in a buried interrupted fashion, thereby recreating the anterior portion of the defect. The superficial skin edges were reapproximated using 4-0 and 5-0 polypropylene sutures in a running interrupted fashion. The distal Burow triangle created from closure of the flap’s secondary defect was aggressively thinned and was utilized as a full-thickness graft for the residual postauricular groove defect (Figure 3). At 2 weeks’ follow-up, the patient was healing well with no postoperative issues and the sutures were removed (Figure 4).

Practice Implications

There are many different reconstructive options for conchal bowl defects, including primary repair, wedge excision, composite graft and interpolation flaps with or without cartilage struts, and hinge flaps. Structural support, EAC patency, auricle symmetry, overall auricle size, and re-creation of natural contours were considered when designing the reconstruction of the defect in our patient; however, his main priority was achieving the greatest cosmetic outcome in a single-stage procedure, therefore limiting our reconstruction options.

Wedge excision, in which the residual lobule and inferior helical rim are removed, could have been considered in our patient but would have drastically altered the symmetry of the size of the ears. A folded postauricular flap, as described in the otolaryngology literature, is an interpolation flap based on the posterior auricular artery that was designed for full-thickness defects of the auricle to prevent any posterior pinning.1 This technique may have worked well in our case, but the patient preferred to avoid a multistage procedure. Additionally, the positional symmetry of the ears was maintained despite utilizing a hinge flap, which does not involve takedown of the pedicle. A composite graft from the contralateral ear could be considered for smaller conchal bowl defects but likely would have resulted in graft failure in our patient’s large defect due to its need for rich blood supply to heal and dependence on lateral wound edges. Cartilage struts in conjunction with a flap could have been considered in this scenario for greater structural support, but in our patient’s case, by maintaining the robust pedicle of our flap and having residual superior cartilage, further structural support was not necessary.

A prior case report described a partial and full-thickness defect in a similar location that was repaired with a retroauricular hinge flap, in which a portion of the flap was extensively de-epithelialized to address the varied thicknesses of the surgical defect.2 In our patient, the defect abutted the skin reservoir on the superolateral neck, and therefore no de-epithelialization was required as the entire epithelialized portion was utilized to recreate the anterior aspect of the defect. Postauricular hinge-type flaps are a reliable, single-stage surgical alternative to the 2-stage folded postauricular interpolation flap when reconstructing large conchal bowl defects. For small full-thickness defects of the ear, a composite graft may be considered; however, blood supply and other nutritional requirements limit this option for large full-thickness defects.

- Roche AM, Griffin M, Shelton R, et al. The folded postauricular flap: a novel approach to reconstruction of large full thickness defects of the conchal bowl. Am J Otolaryngol. 2017;38:706-709. doi:10.1016 /j.amjoto.2017.09.006

- Klein JC, Nijhawan RI. Retroauricular hinge flaps for full-thickness conchal bowl defects. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:E71-E72. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.10.056

- Pickrell BB, Hughes CD, Maricevich RS. Partial ear defects. Semin Plast Surg. 2017 Aug;31:134-140. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1603968.

Practice Gap

Large full-thickness conchal bowl defects often pose a reconstructive challenge. Maintaining the shape and structural integrity of the concha is fundamental for optimal cosmetic and functional outcomes. Prior reports have suggested wedge excisions, composite grafts, interpolation flaps with or without cartilage struts, and hinge flaps as possible options for reconstruction.1-3 However, patients with large defects who prefer single-stage reconstruction procedures present a unique challenge. Herein, we describe a single-stage full-thickness hinge flap technique for a large conchal bowl defect.

The Technique

A 77-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic by an outside dermatologist for Mohs micrographic surgery of a biopsy-proven cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma on the right conchal bowl measuring 1.1×2.1 cm and extending to the edge of the external auditory canal (EAC). The excision was performed that same day and was completed in 2 stages, achieving negative margins and resulting in a full-thickness defect measuring 2.0×3.6 cm that included the posterior auricular sulcus, cavum, antitragus, and proximal EAC (Figure 1). The patient requested a single-stage procedure but emphasized that his main priority was an optimal cosmetic outcome.

To repair this large defect, a full-thickness hinge flap with Burow graft was performed. The hinge-type flap was designed in a triangular fashion emanating at the posterior auricular sulcus adjacent to the posterior aspect of the defect and extending down the lateral neck (Figure 2). The flap was incised and the surrounding tissue was undermined, maintaining a robust pedicle in the center of its body on the superolateral neck. The flap was passed through the posterior aspect of the full-thickness defect and was secured in place with 4-0 polyglactin sutures in a buried interrupted fashion, thereby recreating the anterior portion of the defect. The superficial skin edges were reapproximated using 4-0 and 5-0 polypropylene sutures in a running interrupted fashion. The distal Burow triangle created from closure of the flap’s secondary defect was aggressively thinned and was utilized as a full-thickness graft for the residual postauricular groove defect (Figure 3). At 2 weeks’ follow-up, the patient was healing well with no postoperative issues and the sutures were removed (Figure 4).

Practice Implications

There are many different reconstructive options for conchal bowl defects, including primary repair, wedge excision, composite graft and interpolation flaps with or without cartilage struts, and hinge flaps. Structural support, EAC patency, auricle symmetry, overall auricle size, and re-creation of natural contours were considered when designing the reconstruction of the defect in our patient; however, his main priority was achieving the greatest cosmetic outcome in a single-stage procedure, therefore limiting our reconstruction options.

Wedge excision, in which the residual lobule and inferior helical rim are removed, could have been considered in our patient but would have drastically altered the symmetry of the size of the ears. A folded postauricular flap, as described in the otolaryngology literature, is an interpolation flap based on the posterior auricular artery that was designed for full-thickness defects of the auricle to prevent any posterior pinning.1 This technique may have worked well in our case, but the patient preferred to avoid a multistage procedure. Additionally, the positional symmetry of the ears was maintained despite utilizing a hinge flap, which does not involve takedown of the pedicle. A composite graft from the contralateral ear could be considered for smaller conchal bowl defects but likely would have resulted in graft failure in our patient’s large defect due to its need for rich blood supply to heal and dependence on lateral wound edges. Cartilage struts in conjunction with a flap could have been considered in this scenario for greater structural support, but in our patient’s case, by maintaining the robust pedicle of our flap and having residual superior cartilage, further structural support was not necessary.

A prior case report described a partial and full-thickness defect in a similar location that was repaired with a retroauricular hinge flap, in which a portion of the flap was extensively de-epithelialized to address the varied thicknesses of the surgical defect.2 In our patient, the defect abutted the skin reservoir on the superolateral neck, and therefore no de-epithelialization was required as the entire epithelialized portion was utilized to recreate the anterior aspect of the defect. Postauricular hinge-type flaps are a reliable, single-stage surgical alternative to the 2-stage folded postauricular interpolation flap when reconstructing large conchal bowl defects. For small full-thickness defects of the ear, a composite graft may be considered; however, blood supply and other nutritional requirements limit this option for large full-thickness defects.

Practice Gap

Large full-thickness conchal bowl defects often pose a reconstructive challenge. Maintaining the shape and structural integrity of the concha is fundamental for optimal cosmetic and functional outcomes. Prior reports have suggested wedge excisions, composite grafts, interpolation flaps with or without cartilage struts, and hinge flaps as possible options for reconstruction.1-3 However, patients with large defects who prefer single-stage reconstruction procedures present a unique challenge. Herein, we describe a single-stage full-thickness hinge flap technique for a large conchal bowl defect.

The Technique

A 77-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic by an outside dermatologist for Mohs micrographic surgery of a biopsy-proven cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma on the right conchal bowl measuring 1.1×2.1 cm and extending to the edge of the external auditory canal (EAC). The excision was performed that same day and was completed in 2 stages, achieving negative margins and resulting in a full-thickness defect measuring 2.0×3.6 cm that included the posterior auricular sulcus, cavum, antitragus, and proximal EAC (Figure 1). The patient requested a single-stage procedure but emphasized that his main priority was an optimal cosmetic outcome.

To repair this large defect, a full-thickness hinge flap with Burow graft was performed. The hinge-type flap was designed in a triangular fashion emanating at the posterior auricular sulcus adjacent to the posterior aspect of the defect and extending down the lateral neck (Figure 2). The flap was incised and the surrounding tissue was undermined, maintaining a robust pedicle in the center of its body on the superolateral neck. The flap was passed through the posterior aspect of the full-thickness defect and was secured in place with 4-0 polyglactin sutures in a buried interrupted fashion, thereby recreating the anterior portion of the defect. The superficial skin edges were reapproximated using 4-0 and 5-0 polypropylene sutures in a running interrupted fashion. The distal Burow triangle created from closure of the flap’s secondary defect was aggressively thinned and was utilized as a full-thickness graft for the residual postauricular groove defect (Figure 3). At 2 weeks’ follow-up, the patient was healing well with no postoperative issues and the sutures were removed (Figure 4).

Practice Implications

There are many different reconstructive options for conchal bowl defects, including primary repair, wedge excision, composite graft and interpolation flaps with or without cartilage struts, and hinge flaps. Structural support, EAC patency, auricle symmetry, overall auricle size, and re-creation of natural contours were considered when designing the reconstruction of the defect in our patient; however, his main priority was achieving the greatest cosmetic outcome in a single-stage procedure, therefore limiting our reconstruction options.

Wedge excision, in which the residual lobule and inferior helical rim are removed, could have been considered in our patient but would have drastically altered the symmetry of the size of the ears. A folded postauricular flap, as described in the otolaryngology literature, is an interpolation flap based on the posterior auricular artery that was designed for full-thickness defects of the auricle to prevent any posterior pinning.1 This technique may have worked well in our case, but the patient preferred to avoid a multistage procedure. Additionally, the positional symmetry of the ears was maintained despite utilizing a hinge flap, which does not involve takedown of the pedicle. A composite graft from the contralateral ear could be considered for smaller conchal bowl defects but likely would have resulted in graft failure in our patient’s large defect due to its need for rich blood supply to heal and dependence on lateral wound edges. Cartilage struts in conjunction with a flap could have been considered in this scenario for greater structural support, but in our patient’s case, by maintaining the robust pedicle of our flap and having residual superior cartilage, further structural support was not necessary.

A prior case report described a partial and full-thickness defect in a similar location that was repaired with a retroauricular hinge flap, in which a portion of the flap was extensively de-epithelialized to address the varied thicknesses of the surgical defect.2 In our patient, the defect abutted the skin reservoir on the superolateral neck, and therefore no de-epithelialization was required as the entire epithelialized portion was utilized to recreate the anterior aspect of the defect. Postauricular hinge-type flaps are a reliable, single-stage surgical alternative to the 2-stage folded postauricular interpolation flap when reconstructing large conchal bowl defects. For small full-thickness defects of the ear, a composite graft may be considered; however, blood supply and other nutritional requirements limit this option for large full-thickness defects.

- Roche AM, Griffin M, Shelton R, et al. The folded postauricular flap: a novel approach to reconstruction of large full thickness defects of the conchal bowl. Am J Otolaryngol. 2017;38:706-709. doi:10.1016 /j.amjoto.2017.09.006

- Klein JC, Nijhawan RI. Retroauricular hinge flaps for full-thickness conchal bowl defects. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:E71-E72. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.10.056

- Pickrell BB, Hughes CD, Maricevich RS. Partial ear defects. Semin Plast Surg. 2017 Aug;31:134-140. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1603968.

- Roche AM, Griffin M, Shelton R, et al. The folded postauricular flap: a novel approach to reconstruction of large full thickness defects of the conchal bowl. Am J Otolaryngol. 2017;38:706-709. doi:10.1016 /j.amjoto.2017.09.006

- Klein JC, Nijhawan RI. Retroauricular hinge flaps for full-thickness conchal bowl defects. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:E71-E72. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.10.056

- Pickrell BB, Hughes CD, Maricevich RS. Partial ear defects. Semin Plast Surg. 2017 Aug;31:134-140. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1603968.

Repair of a Large Full-Thickness Conchal Bowl Defect

Repair of a Large Full-Thickness Conchal Bowl Defect

Nonphysician Clinicians in Dermatology Residencies: Cross-sectional Survey on Residency Education

To the Editor:

There is increasing demand for medical care in the United States due to expanded health care coverage; an aging population; and advancements in diagnostics, treatment, and technology.1 It is predicted that by 2050 the number of dermatologists will be 24.4% short of the expected estimate of demand.2

Accordingly, dermatologists are increasingly practicing in team-based care delivery models that incorporate nonphysician clinicians (NPCs), including nurse practitioners and physician assistants.1 Despite recognition that NPCs are taking a larger role in medical teams, there is, to our knowledge, limited training for dermatologists and dermatologists in-training to optimize this professional alliance.

The objectives of this study included (1) determining whether residency programs adequately prepare residents to work with or supervise NPCs and (2) understanding the relationship between NPCs and dermatology residents across residency programs in the United States.

An anonymous cross-sectional, Internet-based survey designed using Google Forms survey creation and administration software was distributed to 117 dermatology residency program directors through email, with a request for further dissemination to residents through self-maintained listserves. Four email reminders about completing and disseminating the survey were sent to program directors between August and November 2020. The study was approved by the Emory University institutional review board. All respondents consented to participate in this survey prior to completing it.

The survey included questions pertaining to demographic information, residents’ experiences working with NPCs, residency program training specific to working with NPCs, and residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions on NPCs’ impact on education and patient care. Program directors were asked to respond N/A to 6 questions on the survey because data from those questions represented residents’ opinions only. Questions relating to residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions were based on a 5-point scale of impact (1=strongly impact in a negative way; 5=strongly impact in a positive way) or importance (1=not at all important; 5=extremely important). The survey was not previously validated.

Descriptive analysis and a paired t test were conducted when appropriate. Missing data were excluded.

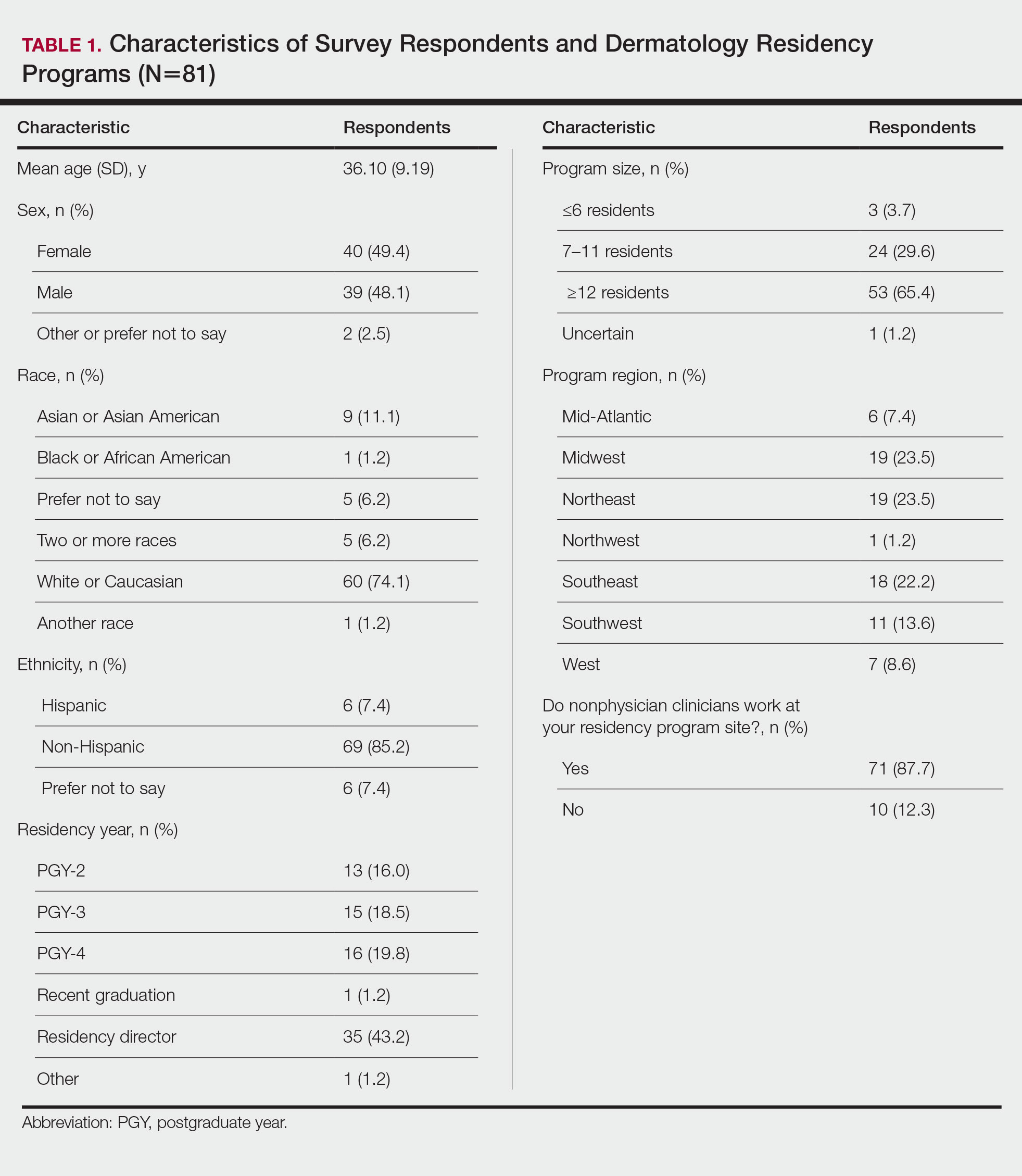

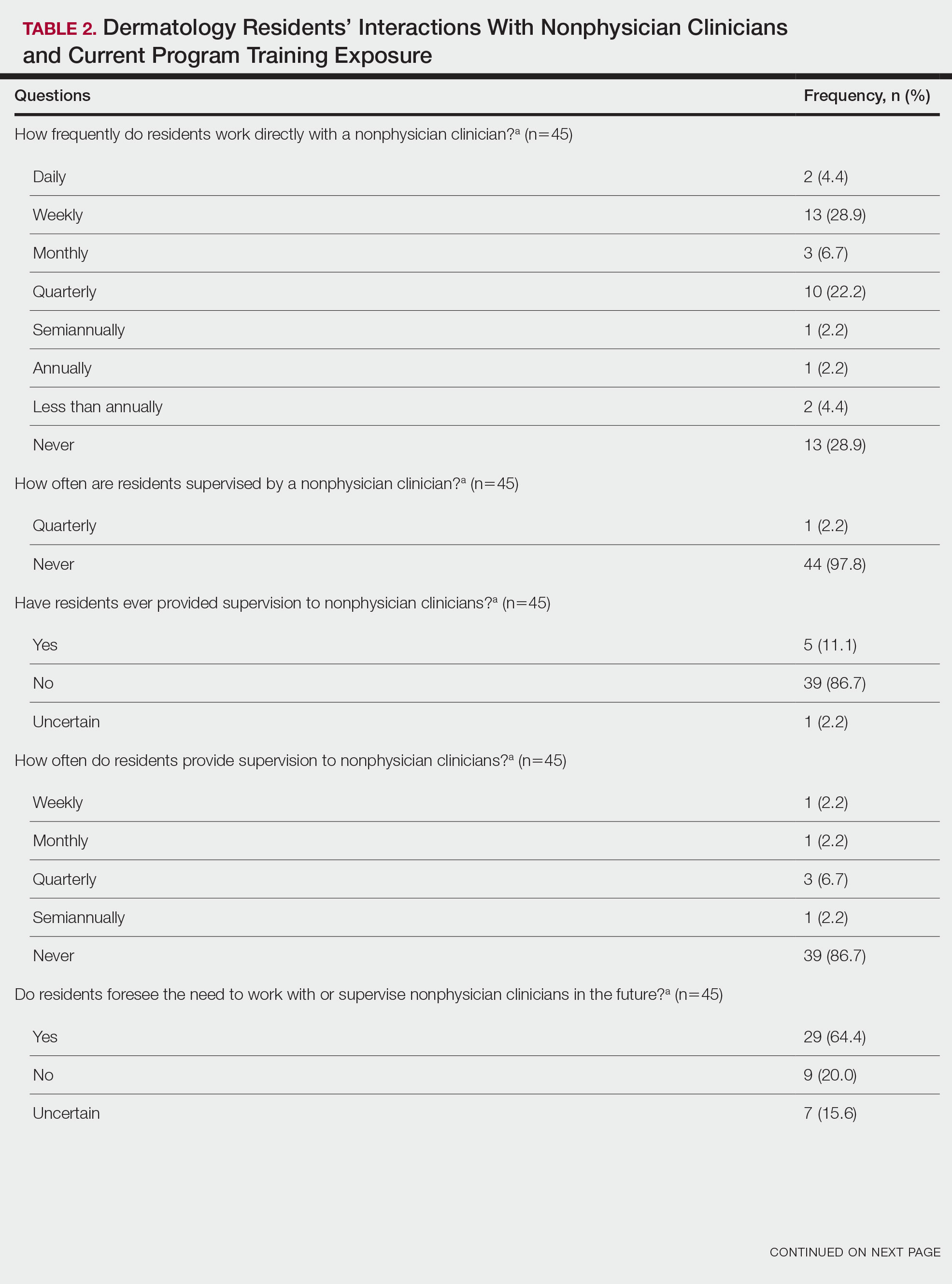

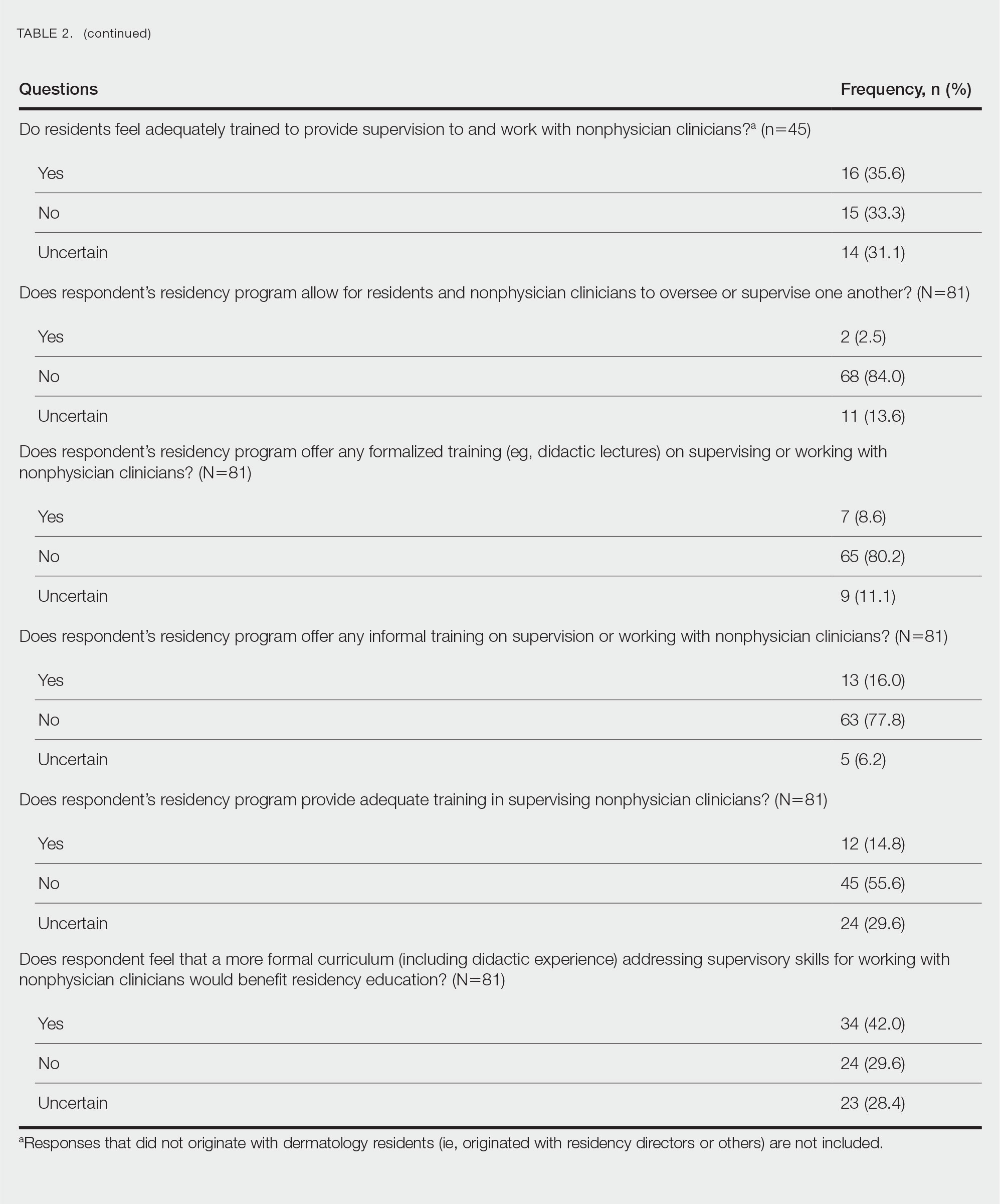

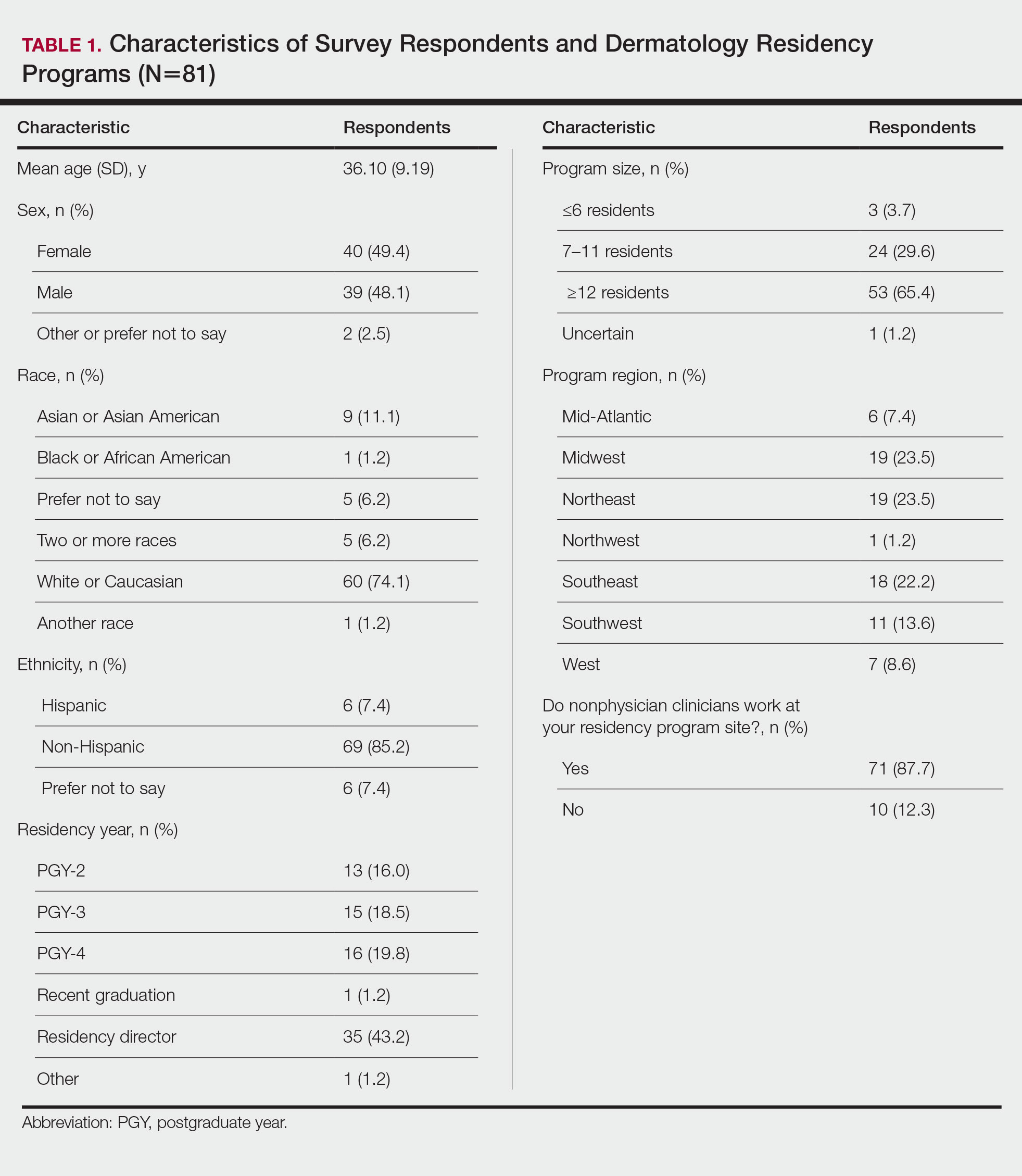

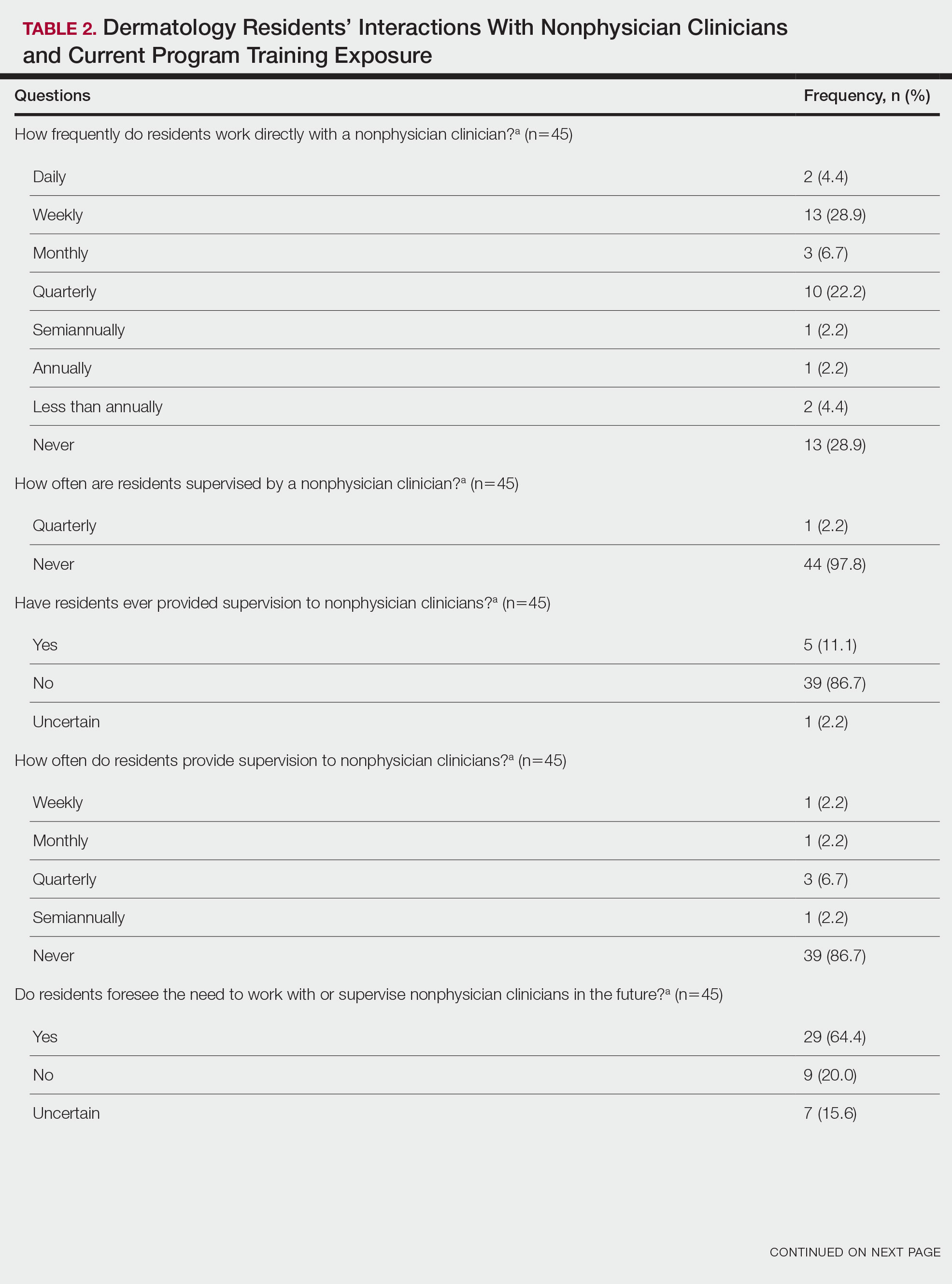

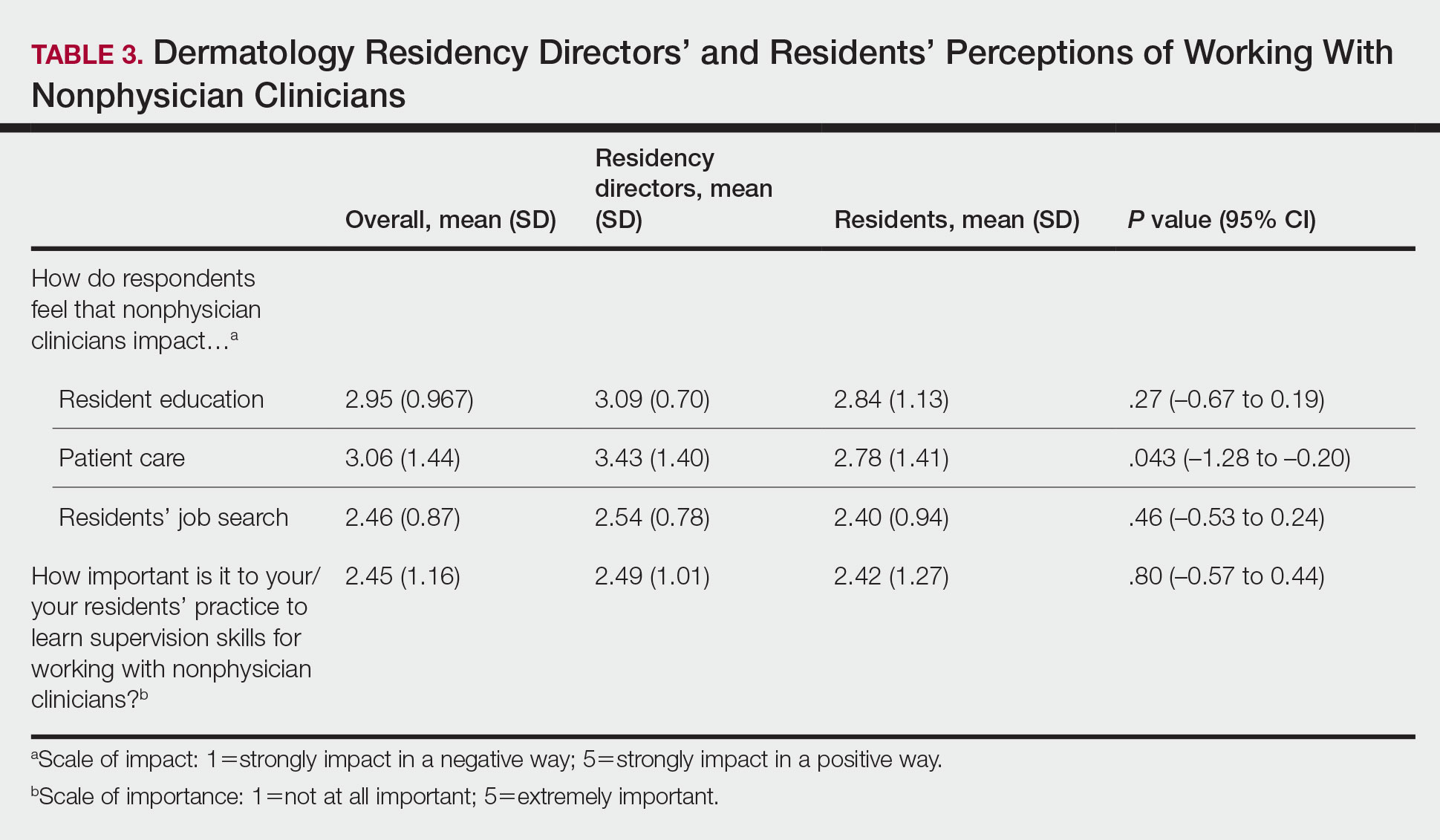

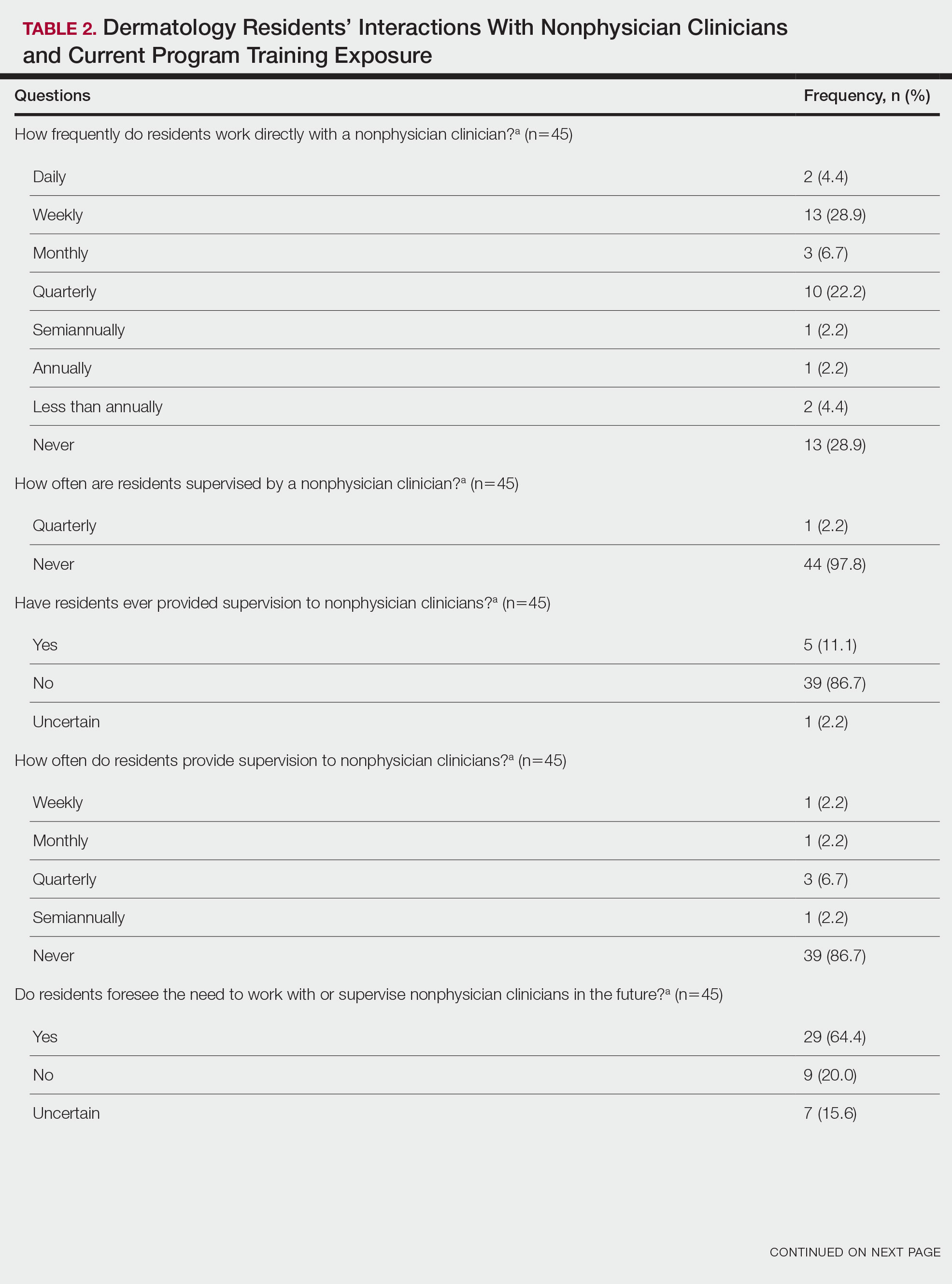

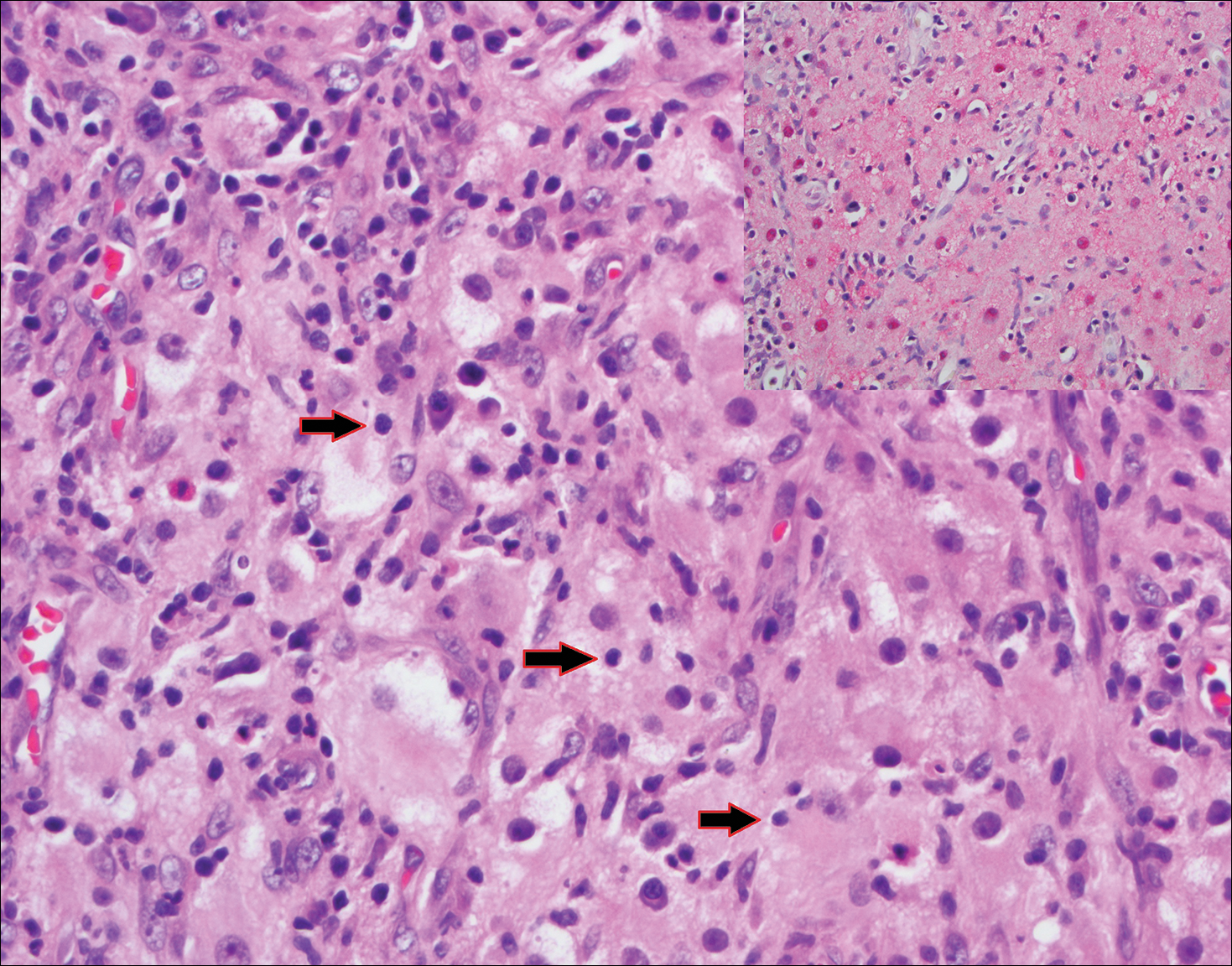

There were 81 respondents to the survey. Demographic information is shown Table 1. Thirty-five dermatology residency program directors (29.9% of 117 programs) responded. Of the 45 residents or recent graduates, 29 (64.4%) reported that they foresaw the need to work with or supervise NPCs in the future (Table 2). Currently, 29 (64.4%) residents also reported that (1) they do not feel adequately trained to provide supervision of or to work with NPCs or (2) were uncertain whether they could do so. Sixty-five (80.2%) respondents stated that there was no formalized training in their program for supervising or working with NPCs; 45 (55.6%) respondents noted that they do not think that their program provided adequate training in supervising NPCs.

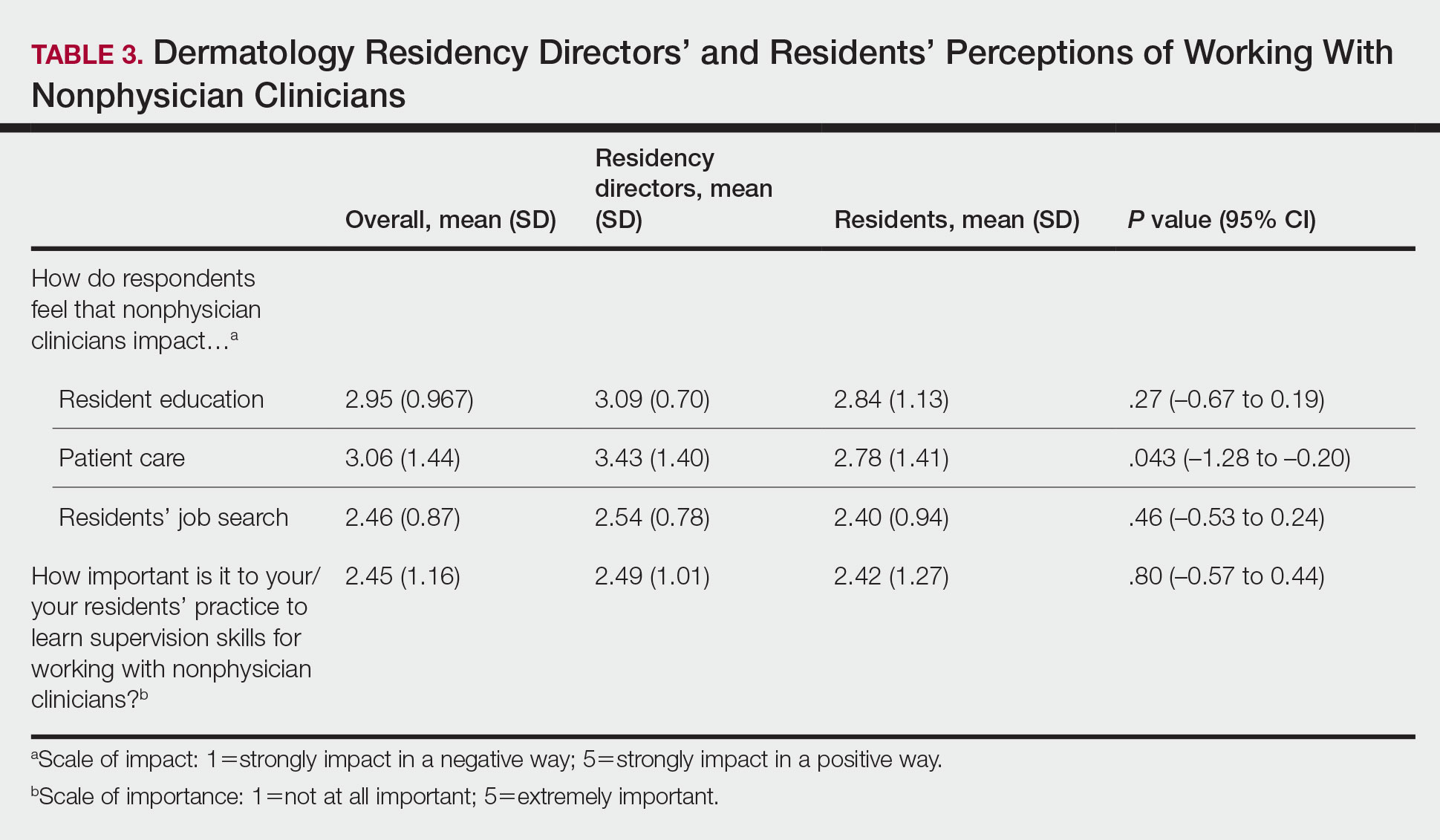

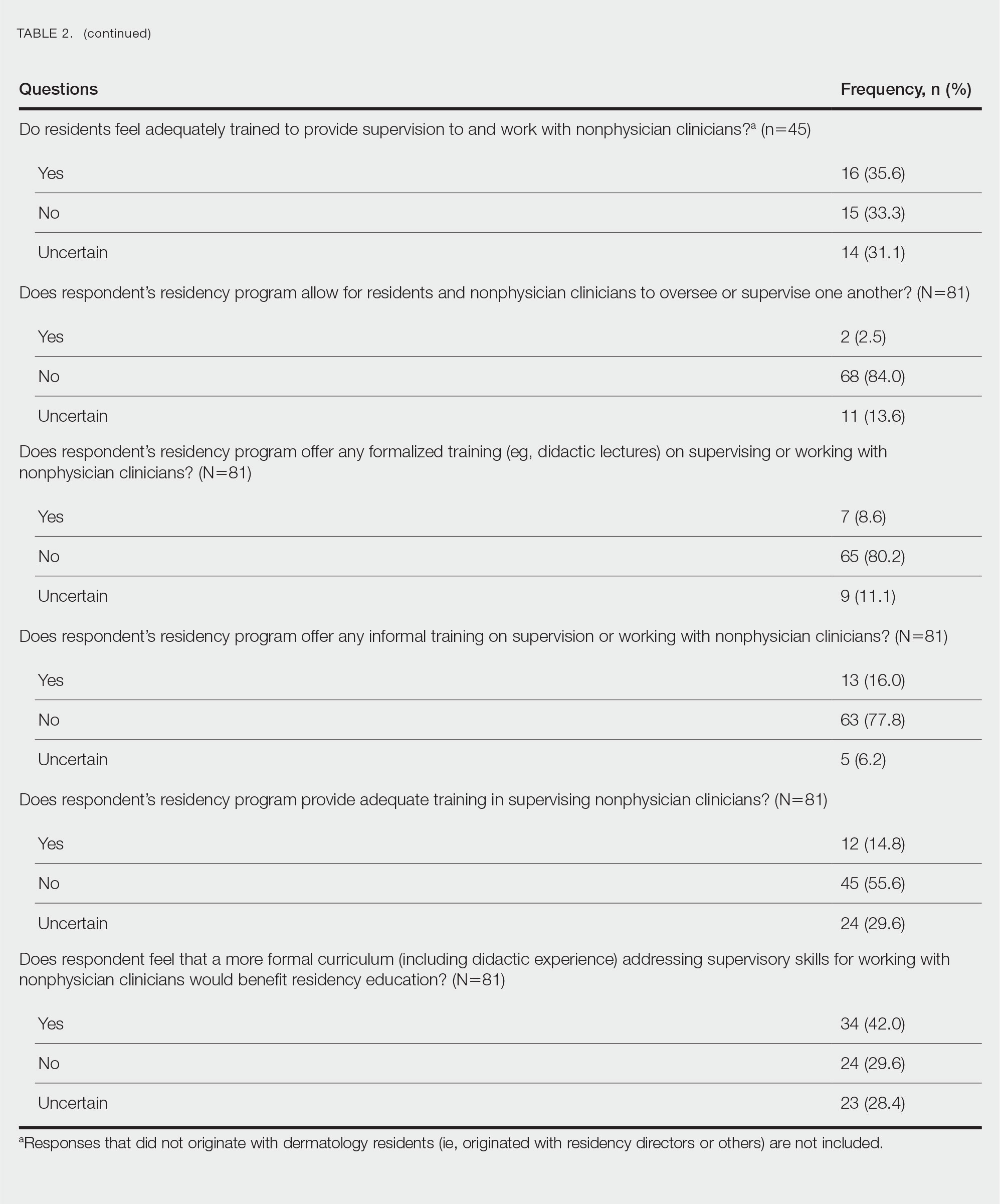

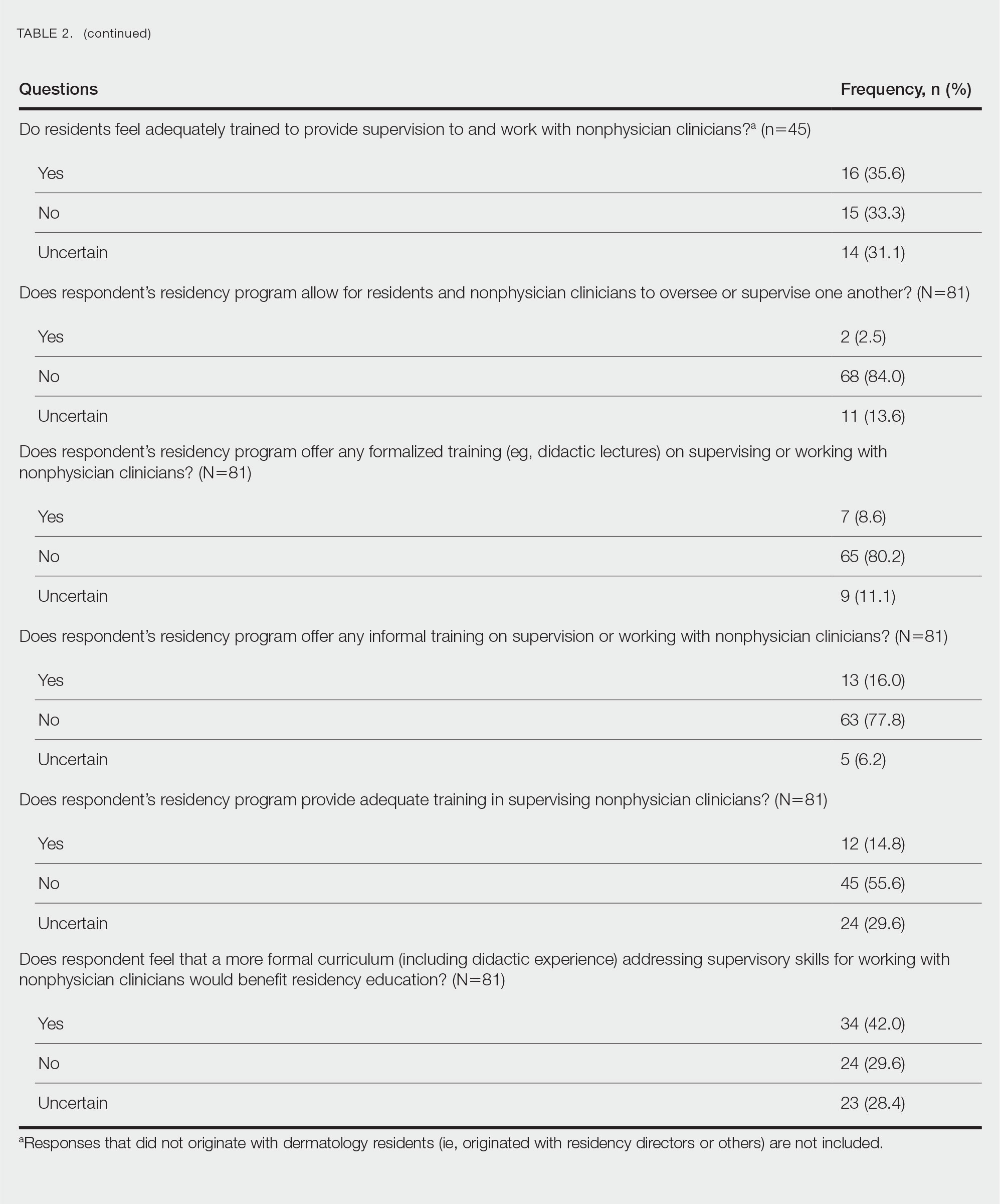

Regarding NPCs impact on care, residency program directors who completed the survey were more likely to rank NPCs as having a more significant positive impact on patient care than residents (mean score, 3.43 vs 2.78; P=.043; 95% CI, –1.28 to –0.20)(Table 3).

This study demonstrated a lack of dermatology training related to working with NPCs in a professional setting and highlighted residents’ perception that formal education in working with and supervising NPCs could be of benefit to their education. Furthermore, residency directors perceived NPCs as having a greater positive impact on patient care than residents did, underscoring the importance of the continued need to educate residents on working synergistically with NPCs to optimize patient care. Ultimately, these results suggest a potential area for further development of residency curricula.

There are approximately 360,000 NPCs serving as integral members of interdisciplinary medical teams across the United States.3,4 In a 2014 survey, 46% of 2001 dermatologists noted that they already employed 1 or more NPCs, a number that has increased over time and is likely to continue to do so.5 Although the number of NPCs in dermatology has increased, there remain limited formal training and certificate programs for these providers.1,6

Furthermore, the American Academy of Dermatology recommends that “[w]hen practicing in a dermatological setting, non-dermatologist physicians and non-physician clinicians . . . should be directly supervised by a board-certified dermatologist.”7 Therefore, the responsibility for a dermatology-specific education can fall on the dermatologist, necessitating adequate supervision and training of NPCs.

The findings of this study were limited by a small sample size; response bias because distribution of the survey relied on program directors disseminating the instrument to their residents, thereby limiting generalizability; and a lack of predissemination validation of the survey. Additional research in this area should focus on survey validation and distribution directly to dermatology residents, instead of relying on dermatology program directors to disseminate the survey.

- Sargen MR, Shi L, Hooker RS, et al. Future growth of physicians and non-physician providers within the U.S. Dermatology workforce. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt840223q6

- The current and projected dermatology workforce in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(suppl 1):AB122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.478

- Nurse anesthetists, nurse midwives, and nurse practitioners.Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/health care/nurse-anesthetists-nurse-midwives-and-nurse-practitioners.htm

- Physician assistants. Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physician-assistants.htm

- Ehrlich A, Kostecki J, Olkaba H. Trends in dermatology practices and the implications for the workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:746-752. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.030

- Anderson AM, Matsumoto M, Saul MI, et al. Accuracy of skin cancer diagnosis by physician assistants compared with dermatologists in a large health care system. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:569-573. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0212s

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Position statement on the practice of dermatology: protecting and preserving patient safety and quality care. Revised May 21, 2016. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://server.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Practice of Dermatology-Protecting Preserving Patient Safety Quality Care.pdf?

To the Editor:

There is increasing demand for medical care in the United States due to expanded health care coverage; an aging population; and advancements in diagnostics, treatment, and technology.1 It is predicted that by 2050 the number of dermatologists will be 24.4% short of the expected estimate of demand.2

Accordingly, dermatologists are increasingly practicing in team-based care delivery models that incorporate nonphysician clinicians (NPCs), including nurse practitioners and physician assistants.1 Despite recognition that NPCs are taking a larger role in medical teams, there is, to our knowledge, limited training for dermatologists and dermatologists in-training to optimize this professional alliance.

The objectives of this study included (1) determining whether residency programs adequately prepare residents to work with or supervise NPCs and (2) understanding the relationship between NPCs and dermatology residents across residency programs in the United States.

An anonymous cross-sectional, Internet-based survey designed using Google Forms survey creation and administration software was distributed to 117 dermatology residency program directors through email, with a request for further dissemination to residents through self-maintained listserves. Four email reminders about completing and disseminating the survey were sent to program directors between August and November 2020. The study was approved by the Emory University institutional review board. All respondents consented to participate in this survey prior to completing it.

The survey included questions pertaining to demographic information, residents’ experiences working with NPCs, residency program training specific to working with NPCs, and residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions on NPCs’ impact on education and patient care. Program directors were asked to respond N/A to 6 questions on the survey because data from those questions represented residents’ opinions only. Questions relating to residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions were based on a 5-point scale of impact (1=strongly impact in a negative way; 5=strongly impact in a positive way) or importance (1=not at all important; 5=extremely important). The survey was not previously validated.

Descriptive analysis and a paired t test were conducted when appropriate. Missing data were excluded.

There were 81 respondents to the survey. Demographic information is shown Table 1. Thirty-five dermatology residency program directors (29.9% of 117 programs) responded. Of the 45 residents or recent graduates, 29 (64.4%) reported that they foresaw the need to work with or supervise NPCs in the future (Table 2). Currently, 29 (64.4%) residents also reported that (1) they do not feel adequately trained to provide supervision of or to work with NPCs or (2) were uncertain whether they could do so. Sixty-five (80.2%) respondents stated that there was no formalized training in their program for supervising or working with NPCs; 45 (55.6%) respondents noted that they do not think that their program provided adequate training in supervising NPCs.

Regarding NPCs impact on care, residency program directors who completed the survey were more likely to rank NPCs as having a more significant positive impact on patient care than residents (mean score, 3.43 vs 2.78; P=.043; 95% CI, –1.28 to –0.20)(Table 3).

This study demonstrated a lack of dermatology training related to working with NPCs in a professional setting and highlighted residents’ perception that formal education in working with and supervising NPCs could be of benefit to their education. Furthermore, residency directors perceived NPCs as having a greater positive impact on patient care than residents did, underscoring the importance of the continued need to educate residents on working synergistically with NPCs to optimize patient care. Ultimately, these results suggest a potential area for further development of residency curricula.

There are approximately 360,000 NPCs serving as integral members of interdisciplinary medical teams across the United States.3,4 In a 2014 survey, 46% of 2001 dermatologists noted that they already employed 1 or more NPCs, a number that has increased over time and is likely to continue to do so.5 Although the number of NPCs in dermatology has increased, there remain limited formal training and certificate programs for these providers.1,6

Furthermore, the American Academy of Dermatology recommends that “[w]hen practicing in a dermatological setting, non-dermatologist physicians and non-physician clinicians . . . should be directly supervised by a board-certified dermatologist.”7 Therefore, the responsibility for a dermatology-specific education can fall on the dermatologist, necessitating adequate supervision and training of NPCs.

The findings of this study were limited by a small sample size; response bias because distribution of the survey relied on program directors disseminating the instrument to their residents, thereby limiting generalizability; and a lack of predissemination validation of the survey. Additional research in this area should focus on survey validation and distribution directly to dermatology residents, instead of relying on dermatology program directors to disseminate the survey.

To the Editor:

There is increasing demand for medical care in the United States due to expanded health care coverage; an aging population; and advancements in diagnostics, treatment, and technology.1 It is predicted that by 2050 the number of dermatologists will be 24.4% short of the expected estimate of demand.2

Accordingly, dermatologists are increasingly practicing in team-based care delivery models that incorporate nonphysician clinicians (NPCs), including nurse practitioners and physician assistants.1 Despite recognition that NPCs are taking a larger role in medical teams, there is, to our knowledge, limited training for dermatologists and dermatologists in-training to optimize this professional alliance.

The objectives of this study included (1) determining whether residency programs adequately prepare residents to work with or supervise NPCs and (2) understanding the relationship between NPCs and dermatology residents across residency programs in the United States.

An anonymous cross-sectional, Internet-based survey designed using Google Forms survey creation and administration software was distributed to 117 dermatology residency program directors through email, with a request for further dissemination to residents through self-maintained listserves. Four email reminders about completing and disseminating the survey were sent to program directors between August and November 2020. The study was approved by the Emory University institutional review board. All respondents consented to participate in this survey prior to completing it.

The survey included questions pertaining to demographic information, residents’ experiences working with NPCs, residency program training specific to working with NPCs, and residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions on NPCs’ impact on education and patient care. Program directors were asked to respond N/A to 6 questions on the survey because data from those questions represented residents’ opinions only. Questions relating to residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions were based on a 5-point scale of impact (1=strongly impact in a negative way; 5=strongly impact in a positive way) or importance (1=not at all important; 5=extremely important). The survey was not previously validated.

Descriptive analysis and a paired t test were conducted when appropriate. Missing data were excluded.

There were 81 respondents to the survey. Demographic information is shown Table 1. Thirty-five dermatology residency program directors (29.9% of 117 programs) responded. Of the 45 residents or recent graduates, 29 (64.4%) reported that they foresaw the need to work with or supervise NPCs in the future (Table 2). Currently, 29 (64.4%) residents also reported that (1) they do not feel adequately trained to provide supervision of or to work with NPCs or (2) were uncertain whether they could do so. Sixty-five (80.2%) respondents stated that there was no formalized training in their program for supervising or working with NPCs; 45 (55.6%) respondents noted that they do not think that their program provided adequate training in supervising NPCs.

Regarding NPCs impact on care, residency program directors who completed the survey were more likely to rank NPCs as having a more significant positive impact on patient care than residents (mean score, 3.43 vs 2.78; P=.043; 95% CI, –1.28 to –0.20)(Table 3).

This study demonstrated a lack of dermatology training related to working with NPCs in a professional setting and highlighted residents’ perception that formal education in working with and supervising NPCs could be of benefit to their education. Furthermore, residency directors perceived NPCs as having a greater positive impact on patient care than residents did, underscoring the importance of the continued need to educate residents on working synergistically with NPCs to optimize patient care. Ultimately, these results suggest a potential area for further development of residency curricula.

There are approximately 360,000 NPCs serving as integral members of interdisciplinary medical teams across the United States.3,4 In a 2014 survey, 46% of 2001 dermatologists noted that they already employed 1 or more NPCs, a number that has increased over time and is likely to continue to do so.5 Although the number of NPCs in dermatology has increased, there remain limited formal training and certificate programs for these providers.1,6

Furthermore, the American Academy of Dermatology recommends that “[w]hen practicing in a dermatological setting, non-dermatologist physicians and non-physician clinicians . . . should be directly supervised by a board-certified dermatologist.”7 Therefore, the responsibility for a dermatology-specific education can fall on the dermatologist, necessitating adequate supervision and training of NPCs.

The findings of this study were limited by a small sample size; response bias because distribution of the survey relied on program directors disseminating the instrument to their residents, thereby limiting generalizability; and a lack of predissemination validation of the survey. Additional research in this area should focus on survey validation and distribution directly to dermatology residents, instead of relying on dermatology program directors to disseminate the survey.

- Sargen MR, Shi L, Hooker RS, et al. Future growth of physicians and non-physician providers within the U.S. Dermatology workforce. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt840223q6

- The current and projected dermatology workforce in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(suppl 1):AB122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.478

- Nurse anesthetists, nurse midwives, and nurse practitioners.Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/health care/nurse-anesthetists-nurse-midwives-and-nurse-practitioners.htm

- Physician assistants. Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physician-assistants.htm

- Ehrlich A, Kostecki J, Olkaba H. Trends in dermatology practices and the implications for the workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:746-752. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.030

- Anderson AM, Matsumoto M, Saul MI, et al. Accuracy of skin cancer diagnosis by physician assistants compared with dermatologists in a large health care system. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:569-573. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0212s

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Position statement on the practice of dermatology: protecting and preserving patient safety and quality care. Revised May 21, 2016. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://server.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Practice of Dermatology-Protecting Preserving Patient Safety Quality Care.pdf?

- Sargen MR, Shi L, Hooker RS, et al. Future growth of physicians and non-physician providers within the U.S. Dermatology workforce. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt840223q6

- The current and projected dermatology workforce in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(suppl 1):AB122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.478

- Nurse anesthetists, nurse midwives, and nurse practitioners.Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/health care/nurse-anesthetists-nurse-midwives-and-nurse-practitioners.htm

- Physician assistants. Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physician-assistants.htm

- Ehrlich A, Kostecki J, Olkaba H. Trends in dermatology practices and the implications for the workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:746-752. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.030

- Anderson AM, Matsumoto M, Saul MI, et al. Accuracy of skin cancer diagnosis by physician assistants compared with dermatologists in a large health care system. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:569-573. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0212s

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Position statement on the practice of dermatology: protecting and preserving patient safety and quality care. Revised May 21, 2016. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://server.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Practice of Dermatology-Protecting Preserving Patient Safety Quality Care.pdf?

Practice Points

- Most dermatology residency programs do not offer training on working with and supervising nonphysician clinicians.

- Dermatology residents think that formal training in supervising nonphysician clinicians would be a beneficial addition to the residency curriculum.

Orange Nodules on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare histiocytic proliferative disorder of unknown etiology. It has 2 forms: limited cutaneous and systemic. The systemic form, also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, affects the lymph nodes and other organs at times. The disease is characterized by a proliferation of histiocytes in the lymph nodes, most commonly in the cervical basin1; however, the inguinal, axillary, mediastinal, or para-aortic nodes also may be affected.1,2 The skin is the most common site of extranodal disease, seen in approximately 10% of cases.1 Cutaneous involvement often is in the facial area but also can be found on the trunk, ears, neck, arms, legs, and genitals. Clinically, skin lesions appear as papules, plaques, and/or nodules.2

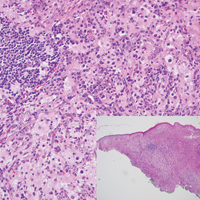

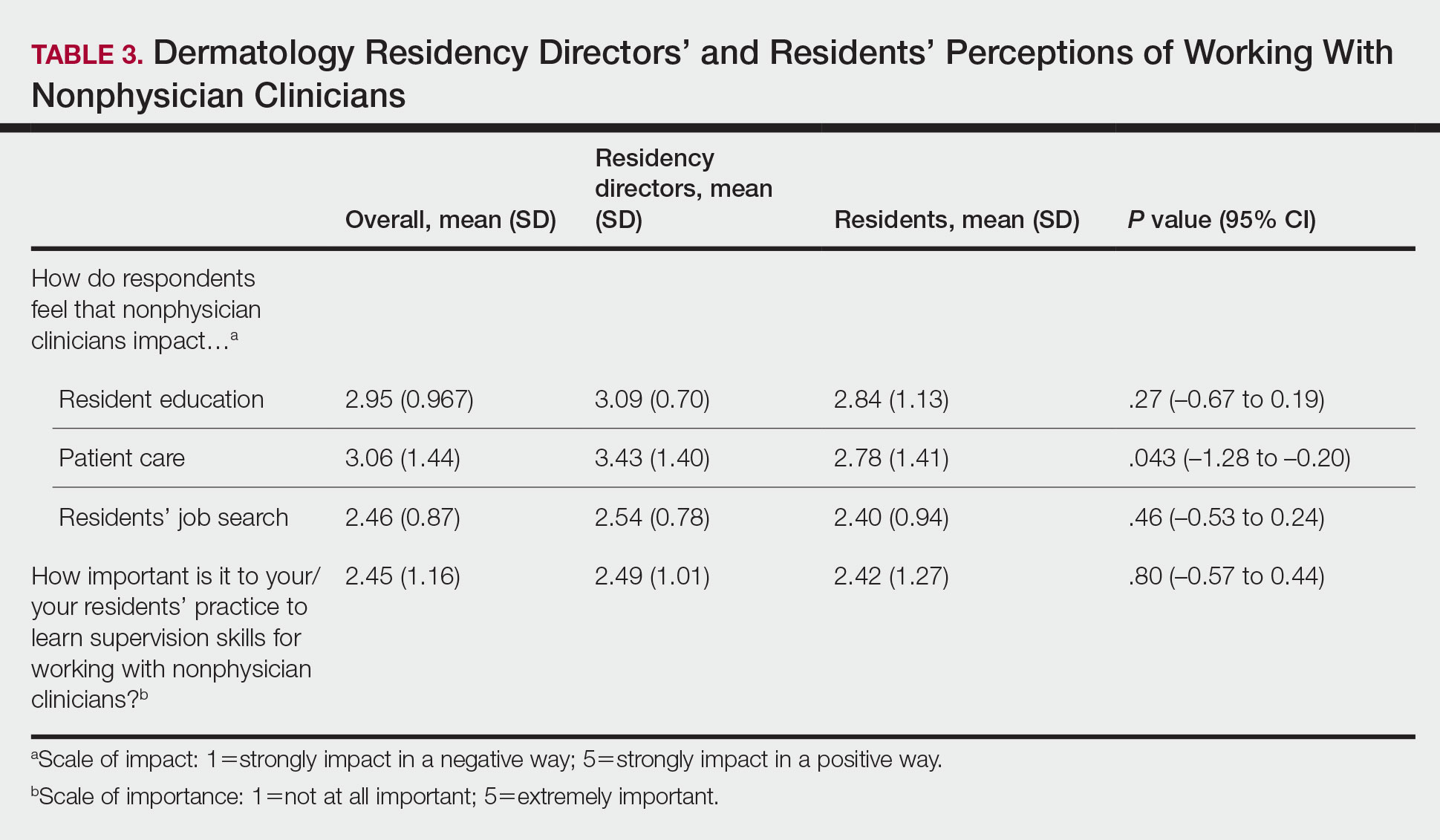

Histopathologic examination of Rosai-Dorfman disease generally shows a dense sheetlike dermal infiltrate of large polygonal histiocytes (Figure 1). Histiocytes may display pale pink or clear cytoplasm. The pathognomonic finding is emperipolesis, which consists of histiocytes with engulfed lymphocytes, erythrocytes, plasma cells, and/or granulocytes surrounded by a clear halo. Immunohistochemical staining also is characteristic, with lesional histiocytes showing expression of S-100 protein (Figure 1, inset) and CD68. The associated inflammatory infiltrate is mixed, containing primarily plasma cells but also lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils.

Blastomycosis (Figure 2) is a systemic infection due to inhalation of Blastomyces dermatitidis conidia. Primary infection occurs in the lungs, and with dissemination the skin is the most common subsequently involved organ.3 Cutaneous blastomycosis shows pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with neutrophilic microabscesses and a dense dermal infiltrate containing suppurative granulomatous inflammation. The nonpigmented yeast phase typically is 8 to 15 µm in length with a refractile cell wall and characteristic single, broad-based budding.3

Granuloma faciale (Figure 3) is a rare disease with unknown etiology characterized by reddish brown plaques or nodules most commonly occurring on the face.4,5 Histology shows a dense nodular dermal infiltrate with a grenz zone. The infiltrate is mixed, containing mostly neutrophils with leukocytoclasis and eosinophils. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is present with associated extravasated erythrocytes. In chronic fibrosing granuloma faciale, lesions can demonstrate fibrosis and hemosiderin deposition, similar to erythema elevatum diutinum.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (Figure 4) is a common histiocytic disease of early childhood, though adult cases have been reported.6 Tumors are found on the head and trunk and are typically firm, reddish yellow papules or nodules.6,7 Histologic examination shows a nodular infiltrate of foamy histiocytes in the superficial dermis. Touton-type multinucleated giant cells with a peripheral rim of xanthomatized foamy cytoplasm and a wreathlike arrangement of nuclei are characteristic. Associated eosinophils are seen. No emperipolesis is present.

Reticulohistiocytoma (Figure 5) is a benign dermal lesion that presents as solitary or less commonly multiple red-brown papules or nodules.8 Lesions consist of well-delineated nodular aggregates of histiocytes containing a finely granular eosinophilic ground glass cytoplasm. Few, if any, eosinophils are found. The lack of Touton multinucleated giant cells or emperipolesis and lack of expression of S-100 protein helps to distinguish reticulohistiocytoma from other entities in the differential diagnosis.

- Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman R. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:19-73.

- Kutlubay Z, Bairamov O, Sevim A, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease: a case report with nodal and cutaneous involvement and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:353-357.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Wolff K, Johnson R, Saavedra AP. Fitzpatrick's Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyrí J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Rodriguez J, Ackerman AB. Xanthogranuloma in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:43-44.

- Tanz WS, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. Cutis. 1994;54:241-245.

- Cohen PR, Lee RA. Adult-onset reticulohistiocytoma presenting as a solitary asymptomatic red knee nodule: report and review of clinical presentations and immunohistochemistry staining features of reticulohistiocytosis. Dermatology Online J. 2014;20. pii:doj_21725.

The Diagnosis: Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare histiocytic proliferative disorder of unknown etiology. It has 2 forms: limited cutaneous and systemic. The systemic form, also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, affects the lymph nodes and other organs at times. The disease is characterized by a proliferation of histiocytes in the lymph nodes, most commonly in the cervical basin1; however, the inguinal, axillary, mediastinal, or para-aortic nodes also may be affected.1,2 The skin is the most common site of extranodal disease, seen in approximately 10% of cases.1 Cutaneous involvement often is in the facial area but also can be found on the trunk, ears, neck, arms, legs, and genitals. Clinically, skin lesions appear as papules, plaques, and/or nodules.2

Histopathologic examination of Rosai-Dorfman disease generally shows a dense sheetlike dermal infiltrate of large polygonal histiocytes (Figure 1). Histiocytes may display pale pink or clear cytoplasm. The pathognomonic finding is emperipolesis, which consists of histiocytes with engulfed lymphocytes, erythrocytes, plasma cells, and/or granulocytes surrounded by a clear halo. Immunohistochemical staining also is characteristic, with lesional histiocytes showing expression of S-100 protein (Figure 1, inset) and CD68. The associated inflammatory infiltrate is mixed, containing primarily plasma cells but also lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils.

Blastomycosis (Figure 2) is a systemic infection due to inhalation of Blastomyces dermatitidis conidia. Primary infection occurs in the lungs, and with dissemination the skin is the most common subsequently involved organ.3 Cutaneous blastomycosis shows pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with neutrophilic microabscesses and a dense dermal infiltrate containing suppurative granulomatous inflammation. The nonpigmented yeast phase typically is 8 to 15 µm in length with a refractile cell wall and characteristic single, broad-based budding.3

Granuloma faciale (Figure 3) is a rare disease with unknown etiology characterized by reddish brown plaques or nodules most commonly occurring on the face.4,5 Histology shows a dense nodular dermal infiltrate with a grenz zone. The infiltrate is mixed, containing mostly neutrophils with leukocytoclasis and eosinophils. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is present with associated extravasated erythrocytes. In chronic fibrosing granuloma faciale, lesions can demonstrate fibrosis and hemosiderin deposition, similar to erythema elevatum diutinum.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (Figure 4) is a common histiocytic disease of early childhood, though adult cases have been reported.6 Tumors are found on the head and trunk and are typically firm, reddish yellow papules or nodules.6,7 Histologic examination shows a nodular infiltrate of foamy histiocytes in the superficial dermis. Touton-type multinucleated giant cells with a peripheral rim of xanthomatized foamy cytoplasm and a wreathlike arrangement of nuclei are characteristic. Associated eosinophils are seen. No emperipolesis is present.

Reticulohistiocytoma (Figure 5) is a benign dermal lesion that presents as solitary or less commonly multiple red-brown papules or nodules.8 Lesions consist of well-delineated nodular aggregates of histiocytes containing a finely granular eosinophilic ground glass cytoplasm. Few, if any, eosinophils are found. The lack of Touton multinucleated giant cells or emperipolesis and lack of expression of S-100 protein helps to distinguish reticulohistiocytoma from other entities in the differential diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare histiocytic proliferative disorder of unknown etiology. It has 2 forms: limited cutaneous and systemic. The systemic form, also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, affects the lymph nodes and other organs at times. The disease is characterized by a proliferation of histiocytes in the lymph nodes, most commonly in the cervical basin1; however, the inguinal, axillary, mediastinal, or para-aortic nodes also may be affected.1,2 The skin is the most common site of extranodal disease, seen in approximately 10% of cases.1 Cutaneous involvement often is in the facial area but also can be found on the trunk, ears, neck, arms, legs, and genitals. Clinically, skin lesions appear as papules, plaques, and/or nodules.2

Histopathologic examination of Rosai-Dorfman disease generally shows a dense sheetlike dermal infiltrate of large polygonal histiocytes (Figure 1). Histiocytes may display pale pink or clear cytoplasm. The pathognomonic finding is emperipolesis, which consists of histiocytes with engulfed lymphocytes, erythrocytes, plasma cells, and/or granulocytes surrounded by a clear halo. Immunohistochemical staining also is characteristic, with lesional histiocytes showing expression of S-100 protein (Figure 1, inset) and CD68. The associated inflammatory infiltrate is mixed, containing primarily plasma cells but also lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils.

Blastomycosis (Figure 2) is a systemic infection due to inhalation of Blastomyces dermatitidis conidia. Primary infection occurs in the lungs, and with dissemination the skin is the most common subsequently involved organ.3 Cutaneous blastomycosis shows pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with neutrophilic microabscesses and a dense dermal infiltrate containing suppurative granulomatous inflammation. The nonpigmented yeast phase typically is 8 to 15 µm in length with a refractile cell wall and characteristic single, broad-based budding.3

Granuloma faciale (Figure 3) is a rare disease with unknown etiology characterized by reddish brown plaques or nodules most commonly occurring on the face.4,5 Histology shows a dense nodular dermal infiltrate with a grenz zone. The infiltrate is mixed, containing mostly neutrophils with leukocytoclasis and eosinophils. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is present with associated extravasated erythrocytes. In chronic fibrosing granuloma faciale, lesions can demonstrate fibrosis and hemosiderin deposition, similar to erythema elevatum diutinum.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (Figure 4) is a common histiocytic disease of early childhood, though adult cases have been reported.6 Tumors are found on the head and trunk and are typically firm, reddish yellow papules or nodules.6,7 Histologic examination shows a nodular infiltrate of foamy histiocytes in the superficial dermis. Touton-type multinucleated giant cells with a peripheral rim of xanthomatized foamy cytoplasm and a wreathlike arrangement of nuclei are characteristic. Associated eosinophils are seen. No emperipolesis is present.

Reticulohistiocytoma (Figure 5) is a benign dermal lesion that presents as solitary or less commonly multiple red-brown papules or nodules.8 Lesions consist of well-delineated nodular aggregates of histiocytes containing a finely granular eosinophilic ground glass cytoplasm. Few, if any, eosinophils are found. The lack of Touton multinucleated giant cells or emperipolesis and lack of expression of S-100 protein helps to distinguish reticulohistiocytoma from other entities in the differential diagnosis.

- Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman R. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:19-73.

- Kutlubay Z, Bairamov O, Sevim A, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease: a case report with nodal and cutaneous involvement and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:353-357.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Wolff K, Johnson R, Saavedra AP. Fitzpatrick's Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyrí J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Rodriguez J, Ackerman AB. Xanthogranuloma in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:43-44.

- Tanz WS, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. Cutis. 1994;54:241-245.

- Cohen PR, Lee RA. Adult-onset reticulohistiocytoma presenting as a solitary asymptomatic red knee nodule: report and review of clinical presentations and immunohistochemistry staining features of reticulohistiocytosis. Dermatology Online J. 2014;20. pii:doj_21725.

- Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman R. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:19-73.

- Kutlubay Z, Bairamov O, Sevim A, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease: a case report with nodal and cutaneous involvement and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:353-357.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Wolff K, Johnson R, Saavedra AP. Fitzpatrick's Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyrí J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Rodriguez J, Ackerman AB. Xanthogranuloma in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:43-44.

- Tanz WS, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. Cutis. 1994;54:241-245.

- Cohen PR, Lee RA. Adult-onset reticulohistiocytoma presenting as a solitary asymptomatic red knee nodule: report and review of clinical presentations and immunohistochemistry staining features of reticulohistiocytosis. Dermatology Online J. 2014;20. pii:doj_21725.

A 59-year-old man presented with itchy and mildly painful nodules on the head and neck of 7 months' duration. The patient denied fever, chills, unintentional weight loss, night sweats, and other systemic symptoms. Physical examination revealed multiple firm pink-orange nodules of varying sizes distributed on the scalp, face, and neck. Right-sided, painless, bulky cervical lymphadenopathy also was noted. An incisional biopsy was performed.