User login

Periungual Papules in an Elderly Woman

The Diagnosis: Multicentric Reticulohistiocytosis

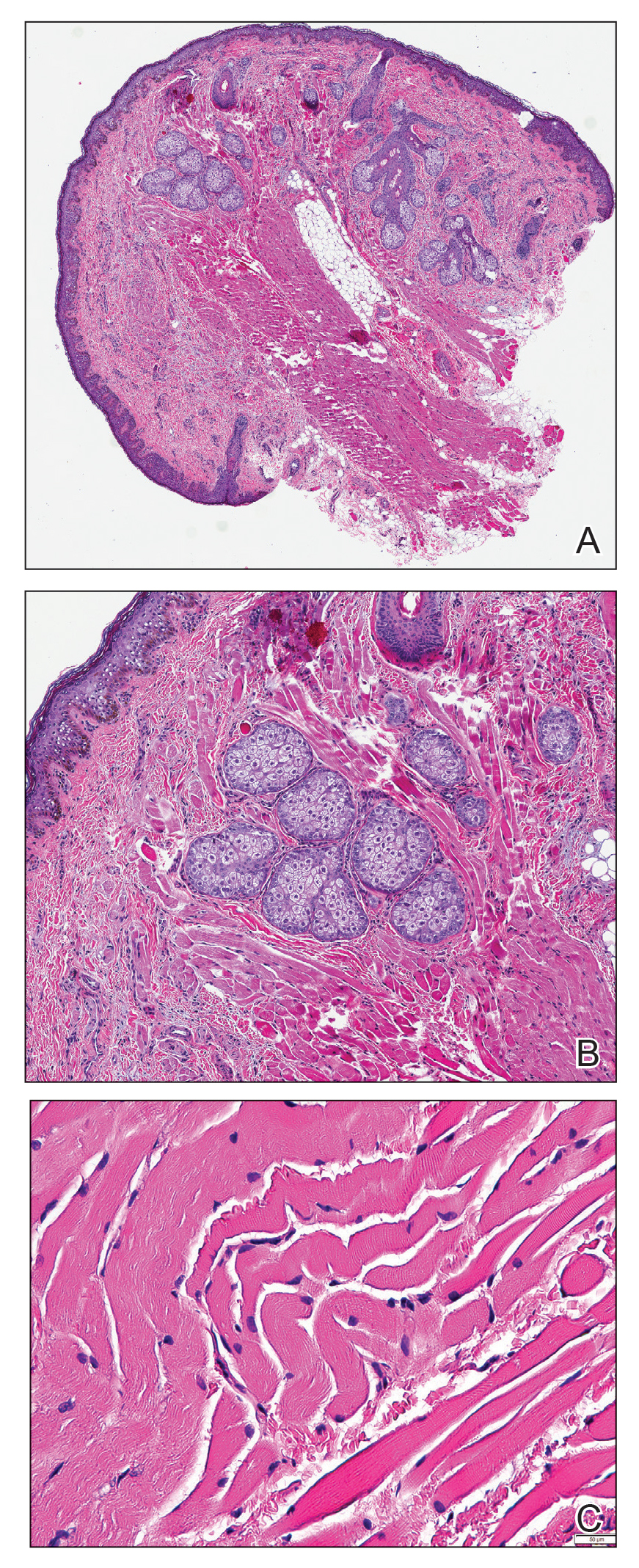

Te patient presented with pink papules coalescing into plaques on the upper chest and lower back (Figure 1) as well as a characteristic finding of periungual papules with a coral bead appearance. Histopathologic examination revealed a dense infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes with amphophilic ground-glass cytoplasm in a nodular configuration (Figure 2). This pattern in conjunction with the clinical features seen in our patient was consistent with a diagnosis of multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (MRH).1-3 The cutaneous symptoms were managed with triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily and oral hydroxyzine 10 mg 3 times daily as needed for itching with moderate improvement. She was referred to rheumatology for arthritis management, and the initial cancer screening was negative.

Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis is a rare granulomatous disease characterized by papulonodular cutaneous lesions and severe erosive arthritis. It has an insidious onset and most commonly affects middle-aged women.1 Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis typically presents as rounded pruritic papules or nodules that may be pink, red, or brown primarily affecting the face and distal upper extremities.1,3 Mucosal involvement occurs in more than half of patients and is characterized by multiple erythematous papules and nodules on the oral and nasopharyngeal mucosae that rarely can produce leonine facies.2 A hallmark feature of MRH is the presence of multiple shiny erythematous papules along the proximal and lateral nail folds that take on a coral bead appearance.1,3,4 Furthermore, nail changes such as atrophy, longitudinal ridging, brittleness, and hyperpigmentation can occur secondary to a synovial reaction that disturbs the nail matrix.4,5

Joint involvement precedes cutaneous involvement in most cases of MRH.1,5 Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis is associated with a symmetric destructive arthritis affecting the hands, knees, shoulders, and hips that often is associated with pain, stiffness, and swelling.1,3 The arthritis rapidly progresses in the early stages of the disease but then becomes less active over the subsequent 8 to 10 years.1 It has the potential to develop into arthritis mutilans, an end-stage form of arthritis also seen in psoriatic and rheumatoid arthritis that leads to severe joint deformity and debilitation.1,2

The etiology of MRH still is unknown, but it has an association with underlying malignancy in up to 25% of patients.6 Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis has been reported in the context of a wide variety of malignancies including melanoma; sarcoma; lymphoma; leukemia; and carcinomas of the breast, colon, and lung. In some cases, the diagnosis of MRH may even precede the diagnosis of cancer.3 Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis also may be associated with autoimmune conditions,3 as seen in our patient who had a history of both hypothyroidism and vitiligo.

Histopathologic examination is essential in distinguishing MRH from other autoimmune disorders associated with hand lesions, rash, and arthralgia. Erythema elevatum diutinum is associated with symmetric, violaceous, red or brown papules and plaques located on the extensor surfaces of the extremities and hands; however, histology reveals a leukocytoclastic vasculitis with a mixture of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and lymphocytes.7 Dermatomyositis may present with arthralgia, flattopped, erythematous (Gottron) papules localized over the proximal interphalangeal and distal interphalangeal joints, as well as proximal nail findings. The latter generally presents with periungual erythema associated with dilated capillary loops rather than the discrete orderly papules seen in MRH. Histologic examination of dermatomyositis shows mild epidermal atrophy, vacuolar changes in the basal keratinocyte layer, and a dermal perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate.8 Because MRH initially can present with joint symptoms and hand nodules, it may be confused with rheumatoid arthritis. However, rheumatoid arthritis typically is associated with severe osteopenia and tends to affect the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints rather than the distal interphalangeal joints that most often are affected in MRH.1 Histologic examination of rheumatoid nodules reveals palisading granulomas surrounding a central area of fibrinoid necrosis.9 Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease that can present with cutaneous involvement including erythema nodosum, skin plaques, subcutaneous nodules, and papular eruptions in addition to joint lesions.10 Sarcoidosis most frequently involves the lungs, manifesting as diffuse interstitial lung disease with bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy. Furthermore, histologic examination of lesions demonstrates classic noncaseating granulomas containing epithelioid cells, multinucleated giant cells with inclusion bodies, and lymphocytes.11

A skin biopsy is required to establish the diagnosis of MRH. In general, patients with MRH and no underlying malignancy have a good prognosis and respond to anti-inflammatory therapies such as nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and corticosteroids. Other agents including methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors also have been effective in more severe cases.1,3,12 Finally, in addition to treating the cutaneous manifestations of MRH, it is important to screen patients for underlying malignancies and other autoimmune conditions.

- Tajirian AL, Malik MK, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:486-492.

- Gold RH, Metzger AL, Mirra JM, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (lipoid dermato-arthritis). an erosive polyarthritis with distinctive clinical, roentgenographic and pathologic features. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1975;124:610-624.

- Luz FB, Gaspar TAP, Kalil-Gaspar N, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:524-531.

- Barrow MV. The nails in multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. (lipoid dermato-arthritis). Arch Dermatol. 1967;95:200-201.

- Barrow MV, Holubar K. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. a review of 33 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1969;48:287-305.

- Snow JL, Muller SA. Malignancy-associated multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: a clinical, histological and immunophenotypic study. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:71-76.

- Yiannias JA, el-Azhary RA, Gibson LE. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a clinical and histopathologic study of 13 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:38-44.

- Smith ES, Hallman JR, DeLuca AM, et al. Dermatomyositis: a clinicopathological study of 40 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009; 31:61-67.

- Athanasou NA, Quinn J, Woods CG, et al. Immunohistology of rheumatoid nodules and rheumatoid synovium. Ann Rheum Dis. 1988;47:398-403.

- Yanardag H, Pamuk ON, Karayel T. Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis: analysis of the features in 170 patients. Respir Med. 2003;97:978-982.

- Ma Y, Gal A, Koss MN. The pathology of pulmonary sarcoidosis: update. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2007;24:150-161.

- Kovach BT, Calamia KT, Walsh JS, et al. Treatment of multicentric reticulohistiocytosis with etanercept. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:919-921.

The Diagnosis: Multicentric Reticulohistiocytosis

Te patient presented with pink papules coalescing into plaques on the upper chest and lower back (Figure 1) as well as a characteristic finding of periungual papules with a coral bead appearance. Histopathologic examination revealed a dense infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes with amphophilic ground-glass cytoplasm in a nodular configuration (Figure 2). This pattern in conjunction with the clinical features seen in our patient was consistent with a diagnosis of multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (MRH).1-3 The cutaneous symptoms were managed with triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily and oral hydroxyzine 10 mg 3 times daily as needed for itching with moderate improvement. She was referred to rheumatology for arthritis management, and the initial cancer screening was negative.

Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis is a rare granulomatous disease characterized by papulonodular cutaneous lesions and severe erosive arthritis. It has an insidious onset and most commonly affects middle-aged women.1 Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis typically presents as rounded pruritic papules or nodules that may be pink, red, or brown primarily affecting the face and distal upper extremities.1,3 Mucosal involvement occurs in more than half of patients and is characterized by multiple erythematous papules and nodules on the oral and nasopharyngeal mucosae that rarely can produce leonine facies.2 A hallmark feature of MRH is the presence of multiple shiny erythematous papules along the proximal and lateral nail folds that take on a coral bead appearance.1,3,4 Furthermore, nail changes such as atrophy, longitudinal ridging, brittleness, and hyperpigmentation can occur secondary to a synovial reaction that disturbs the nail matrix.4,5

Joint involvement precedes cutaneous involvement in most cases of MRH.1,5 Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis is associated with a symmetric destructive arthritis affecting the hands, knees, shoulders, and hips that often is associated with pain, stiffness, and swelling.1,3 The arthritis rapidly progresses in the early stages of the disease but then becomes less active over the subsequent 8 to 10 years.1 It has the potential to develop into arthritis mutilans, an end-stage form of arthritis also seen in psoriatic and rheumatoid arthritis that leads to severe joint deformity and debilitation.1,2

The etiology of MRH still is unknown, but it has an association with underlying malignancy in up to 25% of patients.6 Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis has been reported in the context of a wide variety of malignancies including melanoma; sarcoma; lymphoma; leukemia; and carcinomas of the breast, colon, and lung. In some cases, the diagnosis of MRH may even precede the diagnosis of cancer.3 Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis also may be associated with autoimmune conditions,3 as seen in our patient who had a history of both hypothyroidism and vitiligo.

Histopathologic examination is essential in distinguishing MRH from other autoimmune disorders associated with hand lesions, rash, and arthralgia. Erythema elevatum diutinum is associated with symmetric, violaceous, red or brown papules and plaques located on the extensor surfaces of the extremities and hands; however, histology reveals a leukocytoclastic vasculitis with a mixture of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and lymphocytes.7 Dermatomyositis may present with arthralgia, flattopped, erythematous (Gottron) papules localized over the proximal interphalangeal and distal interphalangeal joints, as well as proximal nail findings. The latter generally presents with periungual erythema associated with dilated capillary loops rather than the discrete orderly papules seen in MRH. Histologic examination of dermatomyositis shows mild epidermal atrophy, vacuolar changes in the basal keratinocyte layer, and a dermal perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate.8 Because MRH initially can present with joint symptoms and hand nodules, it may be confused with rheumatoid arthritis. However, rheumatoid arthritis typically is associated with severe osteopenia and tends to affect the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints rather than the distal interphalangeal joints that most often are affected in MRH.1 Histologic examination of rheumatoid nodules reveals palisading granulomas surrounding a central area of fibrinoid necrosis.9 Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease that can present with cutaneous involvement including erythema nodosum, skin plaques, subcutaneous nodules, and papular eruptions in addition to joint lesions.10 Sarcoidosis most frequently involves the lungs, manifesting as diffuse interstitial lung disease with bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy. Furthermore, histologic examination of lesions demonstrates classic noncaseating granulomas containing epithelioid cells, multinucleated giant cells with inclusion bodies, and lymphocytes.11

A skin biopsy is required to establish the diagnosis of MRH. In general, patients with MRH and no underlying malignancy have a good prognosis and respond to anti-inflammatory therapies such as nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and corticosteroids. Other agents including methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors also have been effective in more severe cases.1,3,12 Finally, in addition to treating the cutaneous manifestations of MRH, it is important to screen patients for underlying malignancies and other autoimmune conditions.

The Diagnosis: Multicentric Reticulohistiocytosis

Te patient presented with pink papules coalescing into plaques on the upper chest and lower back (Figure 1) as well as a characteristic finding of periungual papules with a coral bead appearance. Histopathologic examination revealed a dense infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes with amphophilic ground-glass cytoplasm in a nodular configuration (Figure 2). This pattern in conjunction with the clinical features seen in our patient was consistent with a diagnosis of multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (MRH).1-3 The cutaneous symptoms were managed with triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily and oral hydroxyzine 10 mg 3 times daily as needed for itching with moderate improvement. She was referred to rheumatology for arthritis management, and the initial cancer screening was negative.

Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis is a rare granulomatous disease characterized by papulonodular cutaneous lesions and severe erosive arthritis. It has an insidious onset and most commonly affects middle-aged women.1 Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis typically presents as rounded pruritic papules or nodules that may be pink, red, or brown primarily affecting the face and distal upper extremities.1,3 Mucosal involvement occurs in more than half of patients and is characterized by multiple erythematous papules and nodules on the oral and nasopharyngeal mucosae that rarely can produce leonine facies.2 A hallmark feature of MRH is the presence of multiple shiny erythematous papules along the proximal and lateral nail folds that take on a coral bead appearance.1,3,4 Furthermore, nail changes such as atrophy, longitudinal ridging, brittleness, and hyperpigmentation can occur secondary to a synovial reaction that disturbs the nail matrix.4,5

Joint involvement precedes cutaneous involvement in most cases of MRH.1,5 Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis is associated with a symmetric destructive arthritis affecting the hands, knees, shoulders, and hips that often is associated with pain, stiffness, and swelling.1,3 The arthritis rapidly progresses in the early stages of the disease but then becomes less active over the subsequent 8 to 10 years.1 It has the potential to develop into arthritis mutilans, an end-stage form of arthritis also seen in psoriatic and rheumatoid arthritis that leads to severe joint deformity and debilitation.1,2

The etiology of MRH still is unknown, but it has an association with underlying malignancy in up to 25% of patients.6 Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis has been reported in the context of a wide variety of malignancies including melanoma; sarcoma; lymphoma; leukemia; and carcinomas of the breast, colon, and lung. In some cases, the diagnosis of MRH may even precede the diagnosis of cancer.3 Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis also may be associated with autoimmune conditions,3 as seen in our patient who had a history of both hypothyroidism and vitiligo.

Histopathologic examination is essential in distinguishing MRH from other autoimmune disorders associated with hand lesions, rash, and arthralgia. Erythema elevatum diutinum is associated with symmetric, violaceous, red or brown papules and plaques located on the extensor surfaces of the extremities and hands; however, histology reveals a leukocytoclastic vasculitis with a mixture of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and lymphocytes.7 Dermatomyositis may present with arthralgia, flattopped, erythematous (Gottron) papules localized over the proximal interphalangeal and distal interphalangeal joints, as well as proximal nail findings. The latter generally presents with periungual erythema associated with dilated capillary loops rather than the discrete orderly papules seen in MRH. Histologic examination of dermatomyositis shows mild epidermal atrophy, vacuolar changes in the basal keratinocyte layer, and a dermal perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate.8 Because MRH initially can present with joint symptoms and hand nodules, it may be confused with rheumatoid arthritis. However, rheumatoid arthritis typically is associated with severe osteopenia and tends to affect the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints rather than the distal interphalangeal joints that most often are affected in MRH.1 Histologic examination of rheumatoid nodules reveals palisading granulomas surrounding a central area of fibrinoid necrosis.9 Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease that can present with cutaneous involvement including erythema nodosum, skin plaques, subcutaneous nodules, and papular eruptions in addition to joint lesions.10 Sarcoidosis most frequently involves the lungs, manifesting as diffuse interstitial lung disease with bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy. Furthermore, histologic examination of lesions demonstrates classic noncaseating granulomas containing epithelioid cells, multinucleated giant cells with inclusion bodies, and lymphocytes.11

A skin biopsy is required to establish the diagnosis of MRH. In general, patients with MRH and no underlying malignancy have a good prognosis and respond to anti-inflammatory therapies such as nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and corticosteroids. Other agents including methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors also have been effective in more severe cases.1,3,12 Finally, in addition to treating the cutaneous manifestations of MRH, it is important to screen patients for underlying malignancies and other autoimmune conditions.

- Tajirian AL, Malik MK, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:486-492.

- Gold RH, Metzger AL, Mirra JM, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (lipoid dermato-arthritis). an erosive polyarthritis with distinctive clinical, roentgenographic and pathologic features. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1975;124:610-624.

- Luz FB, Gaspar TAP, Kalil-Gaspar N, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:524-531.

- Barrow MV. The nails in multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. (lipoid dermato-arthritis). Arch Dermatol. 1967;95:200-201.

- Barrow MV, Holubar K. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. a review of 33 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1969;48:287-305.

- Snow JL, Muller SA. Malignancy-associated multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: a clinical, histological and immunophenotypic study. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:71-76.

- Yiannias JA, el-Azhary RA, Gibson LE. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a clinical and histopathologic study of 13 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:38-44.

- Smith ES, Hallman JR, DeLuca AM, et al. Dermatomyositis: a clinicopathological study of 40 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009; 31:61-67.

- Athanasou NA, Quinn J, Woods CG, et al. Immunohistology of rheumatoid nodules and rheumatoid synovium. Ann Rheum Dis. 1988;47:398-403.

- Yanardag H, Pamuk ON, Karayel T. Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis: analysis of the features in 170 patients. Respir Med. 2003;97:978-982.

- Ma Y, Gal A, Koss MN. The pathology of pulmonary sarcoidosis: update. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2007;24:150-161.

- Kovach BT, Calamia KT, Walsh JS, et al. Treatment of multicentric reticulohistiocytosis with etanercept. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:919-921.

- Tajirian AL, Malik MK, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:486-492.

- Gold RH, Metzger AL, Mirra JM, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (lipoid dermato-arthritis). an erosive polyarthritis with distinctive clinical, roentgenographic and pathologic features. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1975;124:610-624.

- Luz FB, Gaspar TAP, Kalil-Gaspar N, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:524-531.

- Barrow MV. The nails in multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. (lipoid dermato-arthritis). Arch Dermatol. 1967;95:200-201.

- Barrow MV, Holubar K. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. a review of 33 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1969;48:287-305.

- Snow JL, Muller SA. Malignancy-associated multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: a clinical, histological and immunophenotypic study. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:71-76.

- Yiannias JA, el-Azhary RA, Gibson LE. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a clinical and histopathologic study of 13 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:38-44.

- Smith ES, Hallman JR, DeLuca AM, et al. Dermatomyositis: a clinicopathological study of 40 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009; 31:61-67.

- Athanasou NA, Quinn J, Woods CG, et al. Immunohistology of rheumatoid nodules and rheumatoid synovium. Ann Rheum Dis. 1988;47:398-403.

- Yanardag H, Pamuk ON, Karayel T. Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis: analysis of the features in 170 patients. Respir Med. 2003;97:978-982.

- Ma Y, Gal A, Koss MN. The pathology of pulmonary sarcoidosis: update. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2007;24:150-161.

- Kovach BT, Calamia KT, Walsh JS, et al. Treatment of multicentric reticulohistiocytosis with etanercept. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:919-921.

A 79-year-old woman presented with pruritic papules and plaques on the chest, back, arms, hands, legs, and feet of 1 year’s duration. She reported a history of hypothyroidism, arthritis, and vitiligo but denied a history of cancer. Physical examination showed pink papules coalescing into plaques on the upper chest and lower back as well as lichenified plaques on the forearms and knees. Erythematous papules on the proximal nail folds of the right first and second digits also were noted. Multiple depigmented patches on the hands, wrists, arms, and lower back also were present, and deformities of the hands and bulbous-appearing knees were observed. Results from a complete blood cell count and blood chemistry analyses showed mild anemia but were otherwise normal. Radiography of the right knee showed degenerative changes and periarticular radiolucencies consistent with an inflammatory arthropathy. A 4-mm punch biopsy specimen from the back was obtained for histopathologic examination.

Flesh-Colored Papule in the Nose of a Child

The Diagnosis: Striated Muscle Hamartoma

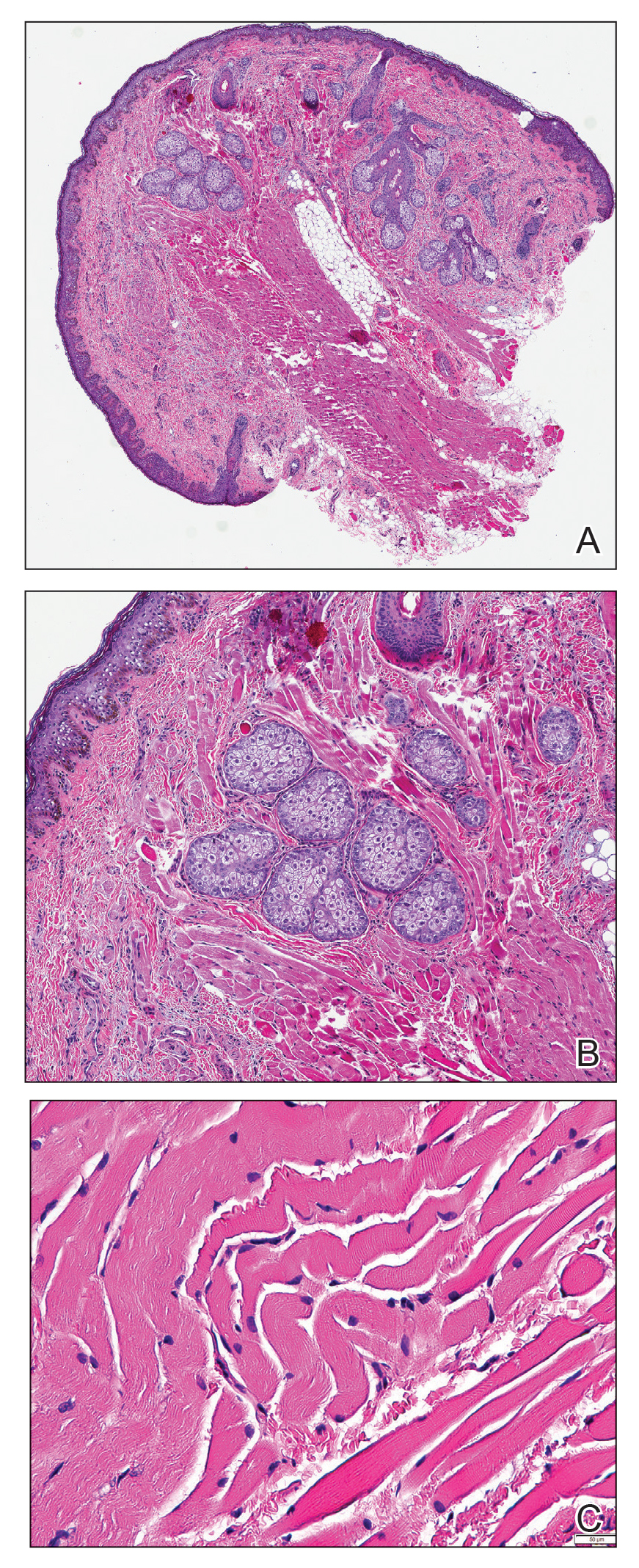

Histopathologic evaluation revealed a dome-shaped papule with a center composed of mature striated muscle bundles, vellus hairs, sebaceous lobules, and nerve twigs (Figure) consistent with a diagnosis of striated muscle hamartoma (SMH).

Striated muscle hamartoma was first described in 1986 by Hendrick et al1 with 2 cases in neonates. Biopsies of the lesions taken from the upper lip and sternum showed a characteristic histology consisting of dermal striated muscle fibers and nerve bundles in the central core of the papules associated with a marked number of adnexa. In 1989, the diagnosis of rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma was described, which showed similar findings.2 Cases reported since these entities were discovered have used the terms striated muscle hamartoma and rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma interchangeably.3

Most commonly found on the head and neck, SMH has now been observed in diverse locations including the sternum, hallux, vagina, and oral cavity.1-15 Many reported cases describe lesions around or in the nose.4,7,8 Multiple congenital anomalies have been described alongside SMH and may be associated with this entity including amniotic bands, cleft lip and palate, coloboma, and Delleman syndrome.1,3,4 Almost all of the lesions present as a sessile or pedunculated papule, polyp, nodule, or plaque measuring from 0.3 cm up to 4.9 cm and typically are present since birth.3,5,15 However, there are a few cases of lesions presenting in adults with no prior history.5,6,15

Microscopically, SMH is defined by a dermal lesion with a core comprised of mature skeletal muscle admixed with adipose tissue, adnexa, nerve bundles, and fibrovascular tissue.1 There are other entities that should be considered before making the diagnosis of SMH. Other hamartomas such as accessory tragus, connective tissue nevus, fibrous hamartoma of infancy, and nevus lipomatosis may present similarly; however, these lesions classically lack skeletal muscle. Benign triton tumors, or neuromuscular hamartomas, are rare lesions composed of skeletal muscle and abundant, intimately associated neural tissue. Neuromuscular hamartomas frequently involve large nerves.16 Rhabdomyomas also should be considered. Adult rhabdomyomas are composed of eosinophilic polygonal cells with granular cytoplasm and occasional cross-striations. Fetal rhabdomyomas have multiple histologic types and are defined by a variable myxoid stroma, eosinophilic spindled cells, and rhabdomyocytes in various stages of maturity. Genital rhabdomyomas histopathologically appear similar to fetal rhabdomyomas but are confined to the genital region. The skeletal muscle present in rhabdomyomas typically is less differentiated.17 TMature skeletal bundles should be a dominant component of the lesion before diagnosing SMH.

Typically presenting as congenital lesions in the head and neck region, papules with a dermal core of mature skeletal muscle associated with adnexa and nerve twigs should prompt consideration of a diagnosis of SMH or rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma. These lesions are benign and usually are cured with complete excision.

- Hendrick SJ, Sanchez RL, Blackwell SJ, et al. Striated muscle hamartoma: description of two cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:153-157.

- Mills AE. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma of skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1989;1:58-63.

- Rosenberg AS, Kirk J, Morgan MB. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma: an unusual dermal entity with a report of two cases and a review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:238-243.

- Sánchez RL, Raimer SS. Clinical and histologic features of striated muscle hamartoma: possible relationship to Delleman’s syndrome. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:40-46.

- Chang CP, Chen GS. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma: a plaque-type variant in an adult. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2005;21:185-188.

- Harris MA, Dutton JJ, Proia AD. Striated muscle hamartoma of the eyelid in an adult woman. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;24:492-494.

- Nakanishi H, Hashimoto I, Takiwaki H, et al. Striated muscle hamartoma of the nostril. J Dermatol. 1995;22:504-507.

- Farris PE, Manning S, Veatch F. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:73-75.

- Grilli R, Escalonilla P, Soriano ML, et al. The so-called striated muscle hamartoma is a hamartoma of cutaneous adnexa and mesenchyme, but not of striated muscle. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:390.

- Sampat K, Cheesman E, Siminas S. Perianal rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2017;99:E193-E195.

- Brinster NK, Farmer ER. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma presenting on a digit. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:61-63.

- Han SH, Song HJ, Hong WK, et al. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma of the vagina. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:753-755.

- De la Sotta P, Salomone C, González S. Rhabdomyomatous (mesenchymal) hamartoma of the tongue: report of a case. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:58-59.

- Magro G, Di Benedetto A, Sanges G, et al. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma of oral cavity: an unusual location for such a rare lesion. Virchows Arch. 2005;446:346-347.

- Wang Y, Zhao H, Yue X, et al. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma presenting as a big subcutaneous mass on the neck: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:410.

- Amita K, Shankar SV, Nischal KC, et al. Benign triton tumor: a rare entity in head and neck region. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47:74-76.

- Walsh S, Hurt M. Cutaneous fetal rhabdomyoma: a case report and historical review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:485-491.

The Diagnosis: Striated Muscle Hamartoma

Histopathologic evaluation revealed a dome-shaped papule with a center composed of mature striated muscle bundles, vellus hairs, sebaceous lobules, and nerve twigs (Figure) consistent with a diagnosis of striated muscle hamartoma (SMH).

Striated muscle hamartoma was first described in 1986 by Hendrick et al1 with 2 cases in neonates. Biopsies of the lesions taken from the upper lip and sternum showed a characteristic histology consisting of dermal striated muscle fibers and nerve bundles in the central core of the papules associated with a marked number of adnexa. In 1989, the diagnosis of rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma was described, which showed similar findings.2 Cases reported since these entities were discovered have used the terms striated muscle hamartoma and rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma interchangeably.3

Most commonly found on the head and neck, SMH has now been observed in diverse locations including the sternum, hallux, vagina, and oral cavity.1-15 Many reported cases describe lesions around or in the nose.4,7,8 Multiple congenital anomalies have been described alongside SMH and may be associated with this entity including amniotic bands, cleft lip and palate, coloboma, and Delleman syndrome.1,3,4 Almost all of the lesions present as a sessile or pedunculated papule, polyp, nodule, or plaque measuring from 0.3 cm up to 4.9 cm and typically are present since birth.3,5,15 However, there are a few cases of lesions presenting in adults with no prior history.5,6,15

Microscopically, SMH is defined by a dermal lesion with a core comprised of mature skeletal muscle admixed with adipose tissue, adnexa, nerve bundles, and fibrovascular tissue.1 There are other entities that should be considered before making the diagnosis of SMH. Other hamartomas such as accessory tragus, connective tissue nevus, fibrous hamartoma of infancy, and nevus lipomatosis may present similarly; however, these lesions classically lack skeletal muscle. Benign triton tumors, or neuromuscular hamartomas, are rare lesions composed of skeletal muscle and abundant, intimately associated neural tissue. Neuromuscular hamartomas frequently involve large nerves.16 Rhabdomyomas also should be considered. Adult rhabdomyomas are composed of eosinophilic polygonal cells with granular cytoplasm and occasional cross-striations. Fetal rhabdomyomas have multiple histologic types and are defined by a variable myxoid stroma, eosinophilic spindled cells, and rhabdomyocytes in various stages of maturity. Genital rhabdomyomas histopathologically appear similar to fetal rhabdomyomas but are confined to the genital region. The skeletal muscle present in rhabdomyomas typically is less differentiated.17 TMature skeletal bundles should be a dominant component of the lesion before diagnosing SMH.

Typically presenting as congenital lesions in the head and neck region, papules with a dermal core of mature skeletal muscle associated with adnexa and nerve twigs should prompt consideration of a diagnosis of SMH or rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma. These lesions are benign and usually are cured with complete excision.

The Diagnosis: Striated Muscle Hamartoma

Histopathologic evaluation revealed a dome-shaped papule with a center composed of mature striated muscle bundles, vellus hairs, sebaceous lobules, and nerve twigs (Figure) consistent with a diagnosis of striated muscle hamartoma (SMH).

Striated muscle hamartoma was first described in 1986 by Hendrick et al1 with 2 cases in neonates. Biopsies of the lesions taken from the upper lip and sternum showed a characteristic histology consisting of dermal striated muscle fibers and nerve bundles in the central core of the papules associated with a marked number of adnexa. In 1989, the diagnosis of rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma was described, which showed similar findings.2 Cases reported since these entities were discovered have used the terms striated muscle hamartoma and rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma interchangeably.3

Most commonly found on the head and neck, SMH has now been observed in diverse locations including the sternum, hallux, vagina, and oral cavity.1-15 Many reported cases describe lesions around or in the nose.4,7,8 Multiple congenital anomalies have been described alongside SMH and may be associated with this entity including amniotic bands, cleft lip and palate, coloboma, and Delleman syndrome.1,3,4 Almost all of the lesions present as a sessile or pedunculated papule, polyp, nodule, or plaque measuring from 0.3 cm up to 4.9 cm and typically are present since birth.3,5,15 However, there are a few cases of lesions presenting in adults with no prior history.5,6,15

Microscopically, SMH is defined by a dermal lesion with a core comprised of mature skeletal muscle admixed with adipose tissue, adnexa, nerve bundles, and fibrovascular tissue.1 There are other entities that should be considered before making the diagnosis of SMH. Other hamartomas such as accessory tragus, connective tissue nevus, fibrous hamartoma of infancy, and nevus lipomatosis may present similarly; however, these lesions classically lack skeletal muscle. Benign triton tumors, or neuromuscular hamartomas, are rare lesions composed of skeletal muscle and abundant, intimately associated neural tissue. Neuromuscular hamartomas frequently involve large nerves.16 Rhabdomyomas also should be considered. Adult rhabdomyomas are composed of eosinophilic polygonal cells with granular cytoplasm and occasional cross-striations. Fetal rhabdomyomas have multiple histologic types and are defined by a variable myxoid stroma, eosinophilic spindled cells, and rhabdomyocytes in various stages of maturity. Genital rhabdomyomas histopathologically appear similar to fetal rhabdomyomas but are confined to the genital region. The skeletal muscle present in rhabdomyomas typically is less differentiated.17 TMature skeletal bundles should be a dominant component of the lesion before diagnosing SMH.

Typically presenting as congenital lesions in the head and neck region, papules with a dermal core of mature skeletal muscle associated with adnexa and nerve twigs should prompt consideration of a diagnosis of SMH or rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma. These lesions are benign and usually are cured with complete excision.

- Hendrick SJ, Sanchez RL, Blackwell SJ, et al. Striated muscle hamartoma: description of two cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:153-157.

- Mills AE. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma of skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1989;1:58-63.

- Rosenberg AS, Kirk J, Morgan MB. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma: an unusual dermal entity with a report of two cases and a review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:238-243.

- Sánchez RL, Raimer SS. Clinical and histologic features of striated muscle hamartoma: possible relationship to Delleman’s syndrome. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:40-46.

- Chang CP, Chen GS. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma: a plaque-type variant in an adult. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2005;21:185-188.

- Harris MA, Dutton JJ, Proia AD. Striated muscle hamartoma of the eyelid in an adult woman. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;24:492-494.

- Nakanishi H, Hashimoto I, Takiwaki H, et al. Striated muscle hamartoma of the nostril. J Dermatol. 1995;22:504-507.

- Farris PE, Manning S, Veatch F. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:73-75.

- Grilli R, Escalonilla P, Soriano ML, et al. The so-called striated muscle hamartoma is a hamartoma of cutaneous adnexa and mesenchyme, but not of striated muscle. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:390.

- Sampat K, Cheesman E, Siminas S. Perianal rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2017;99:E193-E195.

- Brinster NK, Farmer ER. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma presenting on a digit. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:61-63.

- Han SH, Song HJ, Hong WK, et al. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma of the vagina. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:753-755.

- De la Sotta P, Salomone C, González S. Rhabdomyomatous (mesenchymal) hamartoma of the tongue: report of a case. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:58-59.

- Magro G, Di Benedetto A, Sanges G, et al. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma of oral cavity: an unusual location for such a rare lesion. Virchows Arch. 2005;446:346-347.

- Wang Y, Zhao H, Yue X, et al. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma presenting as a big subcutaneous mass on the neck: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:410.

- Amita K, Shankar SV, Nischal KC, et al. Benign triton tumor: a rare entity in head and neck region. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47:74-76.

- Walsh S, Hurt M. Cutaneous fetal rhabdomyoma: a case report and historical review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:485-491.

- Hendrick SJ, Sanchez RL, Blackwell SJ, et al. Striated muscle hamartoma: description of two cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:153-157.

- Mills AE. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma of skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1989;1:58-63.

- Rosenberg AS, Kirk J, Morgan MB. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma: an unusual dermal entity with a report of two cases and a review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:238-243.

- Sánchez RL, Raimer SS. Clinical and histologic features of striated muscle hamartoma: possible relationship to Delleman’s syndrome. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:40-46.

- Chang CP, Chen GS. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma: a plaque-type variant in an adult. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2005;21:185-188.

- Harris MA, Dutton JJ, Proia AD. Striated muscle hamartoma of the eyelid in an adult woman. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;24:492-494.

- Nakanishi H, Hashimoto I, Takiwaki H, et al. Striated muscle hamartoma of the nostril. J Dermatol. 1995;22:504-507.

- Farris PE, Manning S, Veatch F. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:73-75.

- Grilli R, Escalonilla P, Soriano ML, et al. The so-called striated muscle hamartoma is a hamartoma of cutaneous adnexa and mesenchyme, but not of striated muscle. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:390.

- Sampat K, Cheesman E, Siminas S. Perianal rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2017;99:E193-E195.

- Brinster NK, Farmer ER. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma presenting on a digit. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:61-63.

- Han SH, Song HJ, Hong WK, et al. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma of the vagina. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:753-755.

- De la Sotta P, Salomone C, González S. Rhabdomyomatous (mesenchymal) hamartoma of the tongue: report of a case. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:58-59.

- Magro G, Di Benedetto A, Sanges G, et al. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma of oral cavity: an unusual location for such a rare lesion. Virchows Arch. 2005;446:346-347.

- Wang Y, Zhao H, Yue X, et al. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma presenting as a big subcutaneous mass on the neck: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:410.

- Amita K, Shankar SV, Nischal KC, et al. Benign triton tumor: a rare entity in head and neck region. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47:74-76.

- Walsh S, Hurt M. Cutaneous fetal rhabdomyoma: a case report and historical review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:485-491.

A 4-year-old girl presented to our clinic with an asymptomatic flesh-colored papule in the left nostril. The lesion had been present since birth and grew in relation to the patient with no rapid changes. There had been no pigmentation changes and no bleeding, pain, or itching. The patient’s birth and developmental history were normal. Physical examination revealed a singular, 10×5-mm, flesh-colored, pedunculated mass on the left nasal sill. There were no additional lesions present. An excisional biopsy was performed and submitted for pathologic diagnosis.