User login

An alerting sign: Enlarged cardiac silhouette

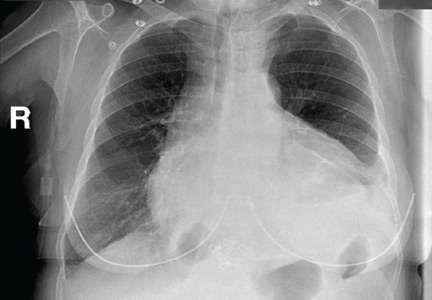

A 75-year-old woman with a history of hypertension and left-lung lobectomy for a carcinoid tumor 10 years ago presented with a 2-week history of progressive cough, dyspnea, and fatigue. Her heart rate was 159 beats per minute with an irregularly irregular rhythm, and her respiratory rate was 36 breaths per minute. Her blood pressure was 140/90 mm Hg. Examination revealed decreased breath sounds and dullness on percussion at the left lung base, jugular venous distention with a positive hepatojugular reflux sign, and an enlarged liver. Electrocardiography showed atrial fibrillation. Chest radiography (Figure 1) revealed enlargement of the cardiac silhouette, with a disproportionately increased transverse diameter, and an obscured left costophrenic angle. A radiograph taken 13 months earlier (Figure 1) had shown a normal cardiothoracic ratio.

EVALUATION OF PERICARDIAL EFFUSION

Pericardial effusion should be suspected in patients presenting with symptoms of impaired cardiac function such as fatigue, dyspnea, nausea, palpitations, lightheadedness, cough, and hoarseness. Patients may also present with chest pain, often decreased by sitting up and leaning forward and exacerbated by lying supine.

Physical examination may reveal distant heart sounds, an absent or displaced apical impulse, dullness and increased fremitus beneath the angle of the left scapula (the Ewart sign), pulsus paradoxus, and nonspecific findings such as tachycardia and hypotension. Jugular venous distention, hepatojugular reflux, and peripheral edema suggest impaired cardiac function.

A chest radiograph showing unexplained new symmetric cardiomegaly (which is often globe-shaped) without signs of pulmonary congestion1 or with a left dominant pleural effusion is an indicator of pericardial effusion, as in our patient. Pericardial fluid may be seen outlining the heart between the epicardial and mediastinal fat, posterior to the sternum in a lateral view.

Other common causes of cardiomegaly include hypertension, congestive heart failure, valvular disease, cardiomyopathy, ischemic heart disease, and pulmonary disease.

Once pericardial effusion is suspected, the next step is to confirm its presence and determine its hemodynamic significance. Transthoracic echocardiography is the imaging test of choice to confirm effusion, as it can be done rapidly and in unstable patients.2

If transthoracic echocardiography is nondiagnostic but suspicion is high, further evaluation may include transesophageal echocardiography,3 computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging.

MAKING THE DIAGNOSIS

Pericardial effusion can occur as part of various diseases involving the pericardium, eg, acute pericarditis, myocarditis, autoimmune disease, postmyocardial infarction, malignancy, aortic dissection, and chest trauma. It can also be associated with certain drugs.

In our patient, echocardiography (Figure 2, Figure 3) demonstrated a large amount of pericardial fluid, and 820 mL of red fluid was aspirated by pericardiocentesis, resulting in relief of her respiratory symptoms. Subcostal two-dimensional echocardiography demonstrated rocking of the heart and intermittent right-ventricular collapse (watch video at www.ccjm.org). Flow cytometry demonstrated 10% kappa+ monoclonal cells. Bone marrow biopsy with immunohistochemical staining revealed infiltration by CD20+, CD5+, CD23+, and BCL1– cells, compatible with small lymphocytic lymphoma.

MALIGNANT PERICARDIAL EFFUSION

Pericardial disease can be the first manifestation of malignancy,4 more often when the patient presents with a large pericardial effusion or tamponade. Malignant tumors of the lung, breast, and esophagus—as well as lymphoma, leukemia, and melanoma—often spread to the pericardium directly or through the lymphatic vessels or bloodstream.4 In our patient, corticosteroid treatment was initiated, and echocardiography at a follow-up visit 2 months later showed no pericardial fluid.

- Khandaker MH, Espinosa RE, Nishimura RA, et al. Pericardial disease: diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc 2010; 85:572–593.

- Cheitlin MD, Armstrong WF, Aurigemma GP, et al; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association; American Society of Echocardiography. ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 guideline update for the clinical application of echocardiography: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/ASE Committee to Update the 1997 Guidelines for the Clinical Application of Echocardiography). Circulation 2003; 108:1146–1162.

- Verhaert D, Gabriel RS, Johnston D, Lytle BW, Desai MY, Klein AL. The role of multimodality imaging in the management of pericardial disease. Circ Cardiovascular Imaging 2010; 3:333–343.

- Burazor I, Imazio M, Markel G, Adler Y. Malignant pericardial effusion. Cardiology 2013; 124:224–232.

A 75-year-old woman with a history of hypertension and left-lung lobectomy for a carcinoid tumor 10 years ago presented with a 2-week history of progressive cough, dyspnea, and fatigue. Her heart rate was 159 beats per minute with an irregularly irregular rhythm, and her respiratory rate was 36 breaths per minute. Her blood pressure was 140/90 mm Hg. Examination revealed decreased breath sounds and dullness on percussion at the left lung base, jugular venous distention with a positive hepatojugular reflux sign, and an enlarged liver. Electrocardiography showed atrial fibrillation. Chest radiography (Figure 1) revealed enlargement of the cardiac silhouette, with a disproportionately increased transverse diameter, and an obscured left costophrenic angle. A radiograph taken 13 months earlier (Figure 1) had shown a normal cardiothoracic ratio.

EVALUATION OF PERICARDIAL EFFUSION

Pericardial effusion should be suspected in patients presenting with symptoms of impaired cardiac function such as fatigue, dyspnea, nausea, palpitations, lightheadedness, cough, and hoarseness. Patients may also present with chest pain, often decreased by sitting up and leaning forward and exacerbated by lying supine.

Physical examination may reveal distant heart sounds, an absent or displaced apical impulse, dullness and increased fremitus beneath the angle of the left scapula (the Ewart sign), pulsus paradoxus, and nonspecific findings such as tachycardia and hypotension. Jugular venous distention, hepatojugular reflux, and peripheral edema suggest impaired cardiac function.

A chest radiograph showing unexplained new symmetric cardiomegaly (which is often globe-shaped) without signs of pulmonary congestion1 or with a left dominant pleural effusion is an indicator of pericardial effusion, as in our patient. Pericardial fluid may be seen outlining the heart between the epicardial and mediastinal fat, posterior to the sternum in a lateral view.

Other common causes of cardiomegaly include hypertension, congestive heart failure, valvular disease, cardiomyopathy, ischemic heart disease, and pulmonary disease.

Once pericardial effusion is suspected, the next step is to confirm its presence and determine its hemodynamic significance. Transthoracic echocardiography is the imaging test of choice to confirm effusion, as it can be done rapidly and in unstable patients.2

If transthoracic echocardiography is nondiagnostic but suspicion is high, further evaluation may include transesophageal echocardiography,3 computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging.

MAKING THE DIAGNOSIS

Pericardial effusion can occur as part of various diseases involving the pericardium, eg, acute pericarditis, myocarditis, autoimmune disease, postmyocardial infarction, malignancy, aortic dissection, and chest trauma. It can also be associated with certain drugs.

In our patient, echocardiography (Figure 2, Figure 3) demonstrated a large amount of pericardial fluid, and 820 mL of red fluid was aspirated by pericardiocentesis, resulting in relief of her respiratory symptoms. Subcostal two-dimensional echocardiography demonstrated rocking of the heart and intermittent right-ventricular collapse (watch video at www.ccjm.org). Flow cytometry demonstrated 10% kappa+ monoclonal cells. Bone marrow biopsy with immunohistochemical staining revealed infiltration by CD20+, CD5+, CD23+, and BCL1– cells, compatible with small lymphocytic lymphoma.

MALIGNANT PERICARDIAL EFFUSION

Pericardial disease can be the first manifestation of malignancy,4 more often when the patient presents with a large pericardial effusion or tamponade. Malignant tumors of the lung, breast, and esophagus—as well as lymphoma, leukemia, and melanoma—often spread to the pericardium directly or through the lymphatic vessels or bloodstream.4 In our patient, corticosteroid treatment was initiated, and echocardiography at a follow-up visit 2 months later showed no pericardial fluid.

A 75-year-old woman with a history of hypertension and left-lung lobectomy for a carcinoid tumor 10 years ago presented with a 2-week history of progressive cough, dyspnea, and fatigue. Her heart rate was 159 beats per minute with an irregularly irregular rhythm, and her respiratory rate was 36 breaths per minute. Her blood pressure was 140/90 mm Hg. Examination revealed decreased breath sounds and dullness on percussion at the left lung base, jugular venous distention with a positive hepatojugular reflux sign, and an enlarged liver. Electrocardiography showed atrial fibrillation. Chest radiography (Figure 1) revealed enlargement of the cardiac silhouette, with a disproportionately increased transverse diameter, and an obscured left costophrenic angle. A radiograph taken 13 months earlier (Figure 1) had shown a normal cardiothoracic ratio.

EVALUATION OF PERICARDIAL EFFUSION

Pericardial effusion should be suspected in patients presenting with symptoms of impaired cardiac function such as fatigue, dyspnea, nausea, palpitations, lightheadedness, cough, and hoarseness. Patients may also present with chest pain, often decreased by sitting up and leaning forward and exacerbated by lying supine.

Physical examination may reveal distant heart sounds, an absent or displaced apical impulse, dullness and increased fremitus beneath the angle of the left scapula (the Ewart sign), pulsus paradoxus, and nonspecific findings such as tachycardia and hypotension. Jugular venous distention, hepatojugular reflux, and peripheral edema suggest impaired cardiac function.

A chest radiograph showing unexplained new symmetric cardiomegaly (which is often globe-shaped) without signs of pulmonary congestion1 or with a left dominant pleural effusion is an indicator of pericardial effusion, as in our patient. Pericardial fluid may be seen outlining the heart between the epicardial and mediastinal fat, posterior to the sternum in a lateral view.

Other common causes of cardiomegaly include hypertension, congestive heart failure, valvular disease, cardiomyopathy, ischemic heart disease, and pulmonary disease.

Once pericardial effusion is suspected, the next step is to confirm its presence and determine its hemodynamic significance. Transthoracic echocardiography is the imaging test of choice to confirm effusion, as it can be done rapidly and in unstable patients.2

If transthoracic echocardiography is nondiagnostic but suspicion is high, further evaluation may include transesophageal echocardiography,3 computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging.

MAKING THE DIAGNOSIS

Pericardial effusion can occur as part of various diseases involving the pericardium, eg, acute pericarditis, myocarditis, autoimmune disease, postmyocardial infarction, malignancy, aortic dissection, and chest trauma. It can also be associated with certain drugs.

In our patient, echocardiography (Figure 2, Figure 3) demonstrated a large amount of pericardial fluid, and 820 mL of red fluid was aspirated by pericardiocentesis, resulting in relief of her respiratory symptoms. Subcostal two-dimensional echocardiography demonstrated rocking of the heart and intermittent right-ventricular collapse (watch video at www.ccjm.org). Flow cytometry demonstrated 10% kappa+ monoclonal cells. Bone marrow biopsy with immunohistochemical staining revealed infiltration by CD20+, CD5+, CD23+, and BCL1– cells, compatible with small lymphocytic lymphoma.

MALIGNANT PERICARDIAL EFFUSION

Pericardial disease can be the first manifestation of malignancy,4 more often when the patient presents with a large pericardial effusion or tamponade. Malignant tumors of the lung, breast, and esophagus—as well as lymphoma, leukemia, and melanoma—often spread to the pericardium directly or through the lymphatic vessels or bloodstream.4 In our patient, corticosteroid treatment was initiated, and echocardiography at a follow-up visit 2 months later showed no pericardial fluid.

- Khandaker MH, Espinosa RE, Nishimura RA, et al. Pericardial disease: diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc 2010; 85:572–593.

- Cheitlin MD, Armstrong WF, Aurigemma GP, et al; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association; American Society of Echocardiography. ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 guideline update for the clinical application of echocardiography: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/ASE Committee to Update the 1997 Guidelines for the Clinical Application of Echocardiography). Circulation 2003; 108:1146–1162.

- Verhaert D, Gabriel RS, Johnston D, Lytle BW, Desai MY, Klein AL. The role of multimodality imaging in the management of pericardial disease. Circ Cardiovascular Imaging 2010; 3:333–343.

- Burazor I, Imazio M, Markel G, Adler Y. Malignant pericardial effusion. Cardiology 2013; 124:224–232.

- Khandaker MH, Espinosa RE, Nishimura RA, et al. Pericardial disease: diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc 2010; 85:572–593.

- Cheitlin MD, Armstrong WF, Aurigemma GP, et al; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association; American Society of Echocardiography. ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 guideline update for the clinical application of echocardiography: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/ASE Committee to Update the 1997 Guidelines for the Clinical Application of Echocardiography). Circulation 2003; 108:1146–1162.

- Verhaert D, Gabriel RS, Johnston D, Lytle BW, Desai MY, Klein AL. The role of multimodality imaging in the management of pericardial disease. Circ Cardiovascular Imaging 2010; 3:333–343.

- Burazor I, Imazio M, Markel G, Adler Y. Malignant pericardial effusion. Cardiology 2013; 124:224–232.