User login

Multifocal Annular Pink Plaques With a Central Violaceous Hue

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Erythema Chronicum Migrans

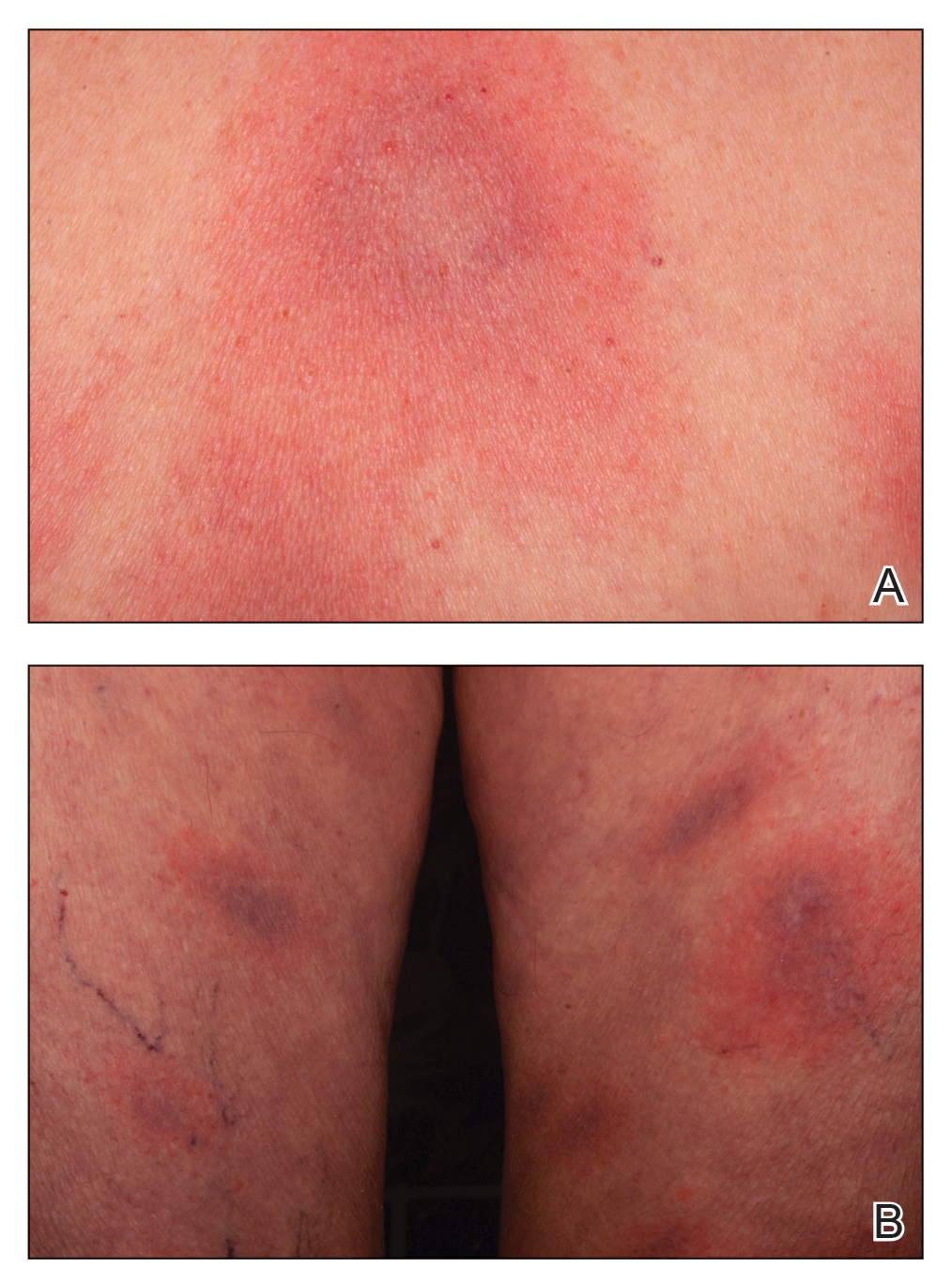

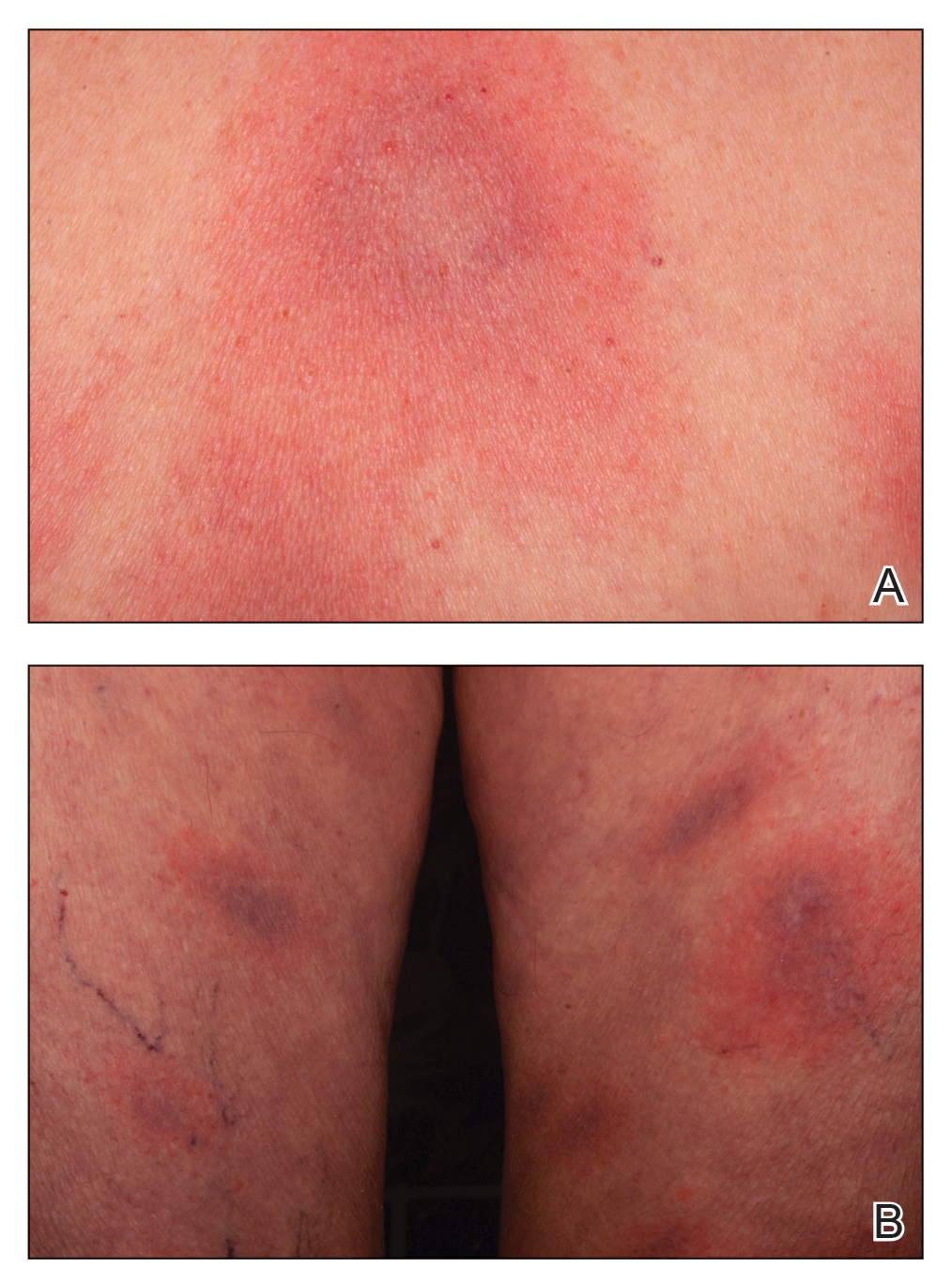

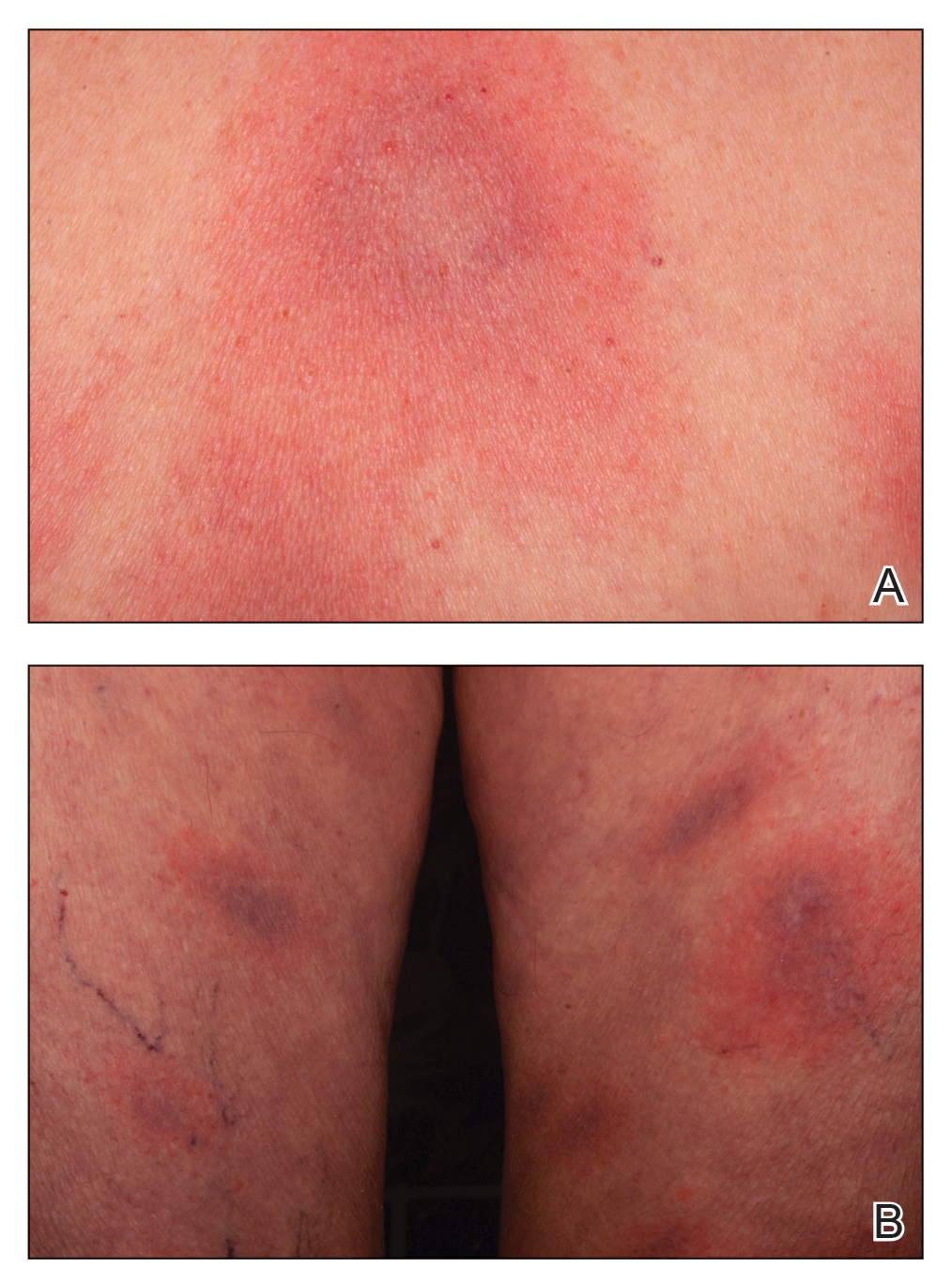

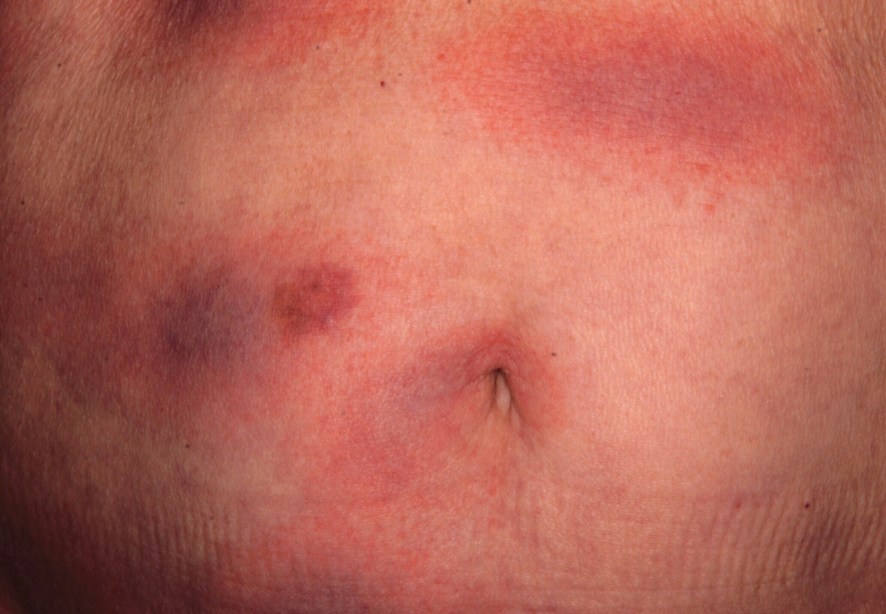

Empiric treatment with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days was initiated for suspected early disseminated Lyme disease manifesting as disseminated multifocal erythema chronicum migrans (Figure). Lyme screening immunoassay and confirmatory IgM Western blot testing subsequently were found to be positive. The clinical history of recent travel to an endemic area and tick bite combined with the recent onset of multifocal erythema migrans lesions, systemic symptoms, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and positive Lyme serology supported the diagnosis of Lyme disease.

The appropriate clinical context and cutaneous morphology are key when considering the differential diagnosis for multifocal annular lesions. Several entities comprised the differential diagnosis considered in our patient. Sweet syndrome is a neutrophilic dermatosis that can present with fever and varying painful cutaneous lesions. It often is associated with certain medications, underlying illnesses, and infections.1 Our patient’s lesions were not painful, and she had no notable medical history, recent infections, or new medication use, making Sweet syndrome unlikely. A fixed drug eruption was low on the differential, as the patient denied starting any new medications within the 3 months prior to presentation. Erythema multiforme is an acute-onset immunemediated condition of the skin and mucous membranes that typically affects young adults and often is associated with infection (eg, herpes simplex virus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae) or medication use. Cutaneous lesions typically are self-limited, less than 3 cm targets with 3 concentric distinct color zones, often with central bullae or erosions. Although erythema multiforme was higher on the differential, it was less likely, as the patient lacked mucosal lesions and did not have symptoms of underlying herpetic or mycoplasma infection, and the clinical picture was more consistent with Lyme disease. Lastly, the failure for individual skin lesions to resolve within

24 hours excluded the diagnosis of urticaria.

Lyme disease is a tick-borne illness caused by 3 species of the Borrelia spirochete: Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia afzelii, and Borrelia garinii.2 In the United States, the disease predominantly is caused by B burgdorferi that is endemic in the upper Midwest and Northeast regions.3 There are 3 stages of Lyme disease: early localized, early disseminated, and late disseminated disease. Early localized disease typically presents with a characteristic single erythema migrans (EM) lesion 3 to 30 days following a bite by the tick Ixodes scapularis.2 The EM lesion gradually can enlarge over a period of several days, reaching up to 12 inches in diameter.2 Early disseminated disease can occur weeks to months following a tick bite and may present with systemic symptoms, multiple widespread

EM lesions, neurologic features such as meningitis or facial nerve palsy, and/or cardiac manifestations such as atrioventricular block or myocarditis. Late disseminated disease can present with chronic arthritis or encephalopathy after months to years if the disease is left untreated.4

Early localized Lyme disease can be diagnosed clinically if the characteristic EM lesion is present in a patient who visited an endemic area. Laboratory testing and Lyme serology are neither required nor recommended in these cases, as the lesion often appears before adequate time has lapsed to develop an adaptive immune response to the organism.5 In contrast, Lyme serology should be ordered in any patient who meets all of the following criteria: (1) patient lives in or has recently traveled to an area endemic for Lyme disease, (2) presence of a risk factor for tick exposure, and (3) symptoms consistent with early disseminated or late Lyme disease. Patients with signs of early or late disseminated disease typically are seropositive, as IgM antibodies can be detected within 2 weeks of onset of the EM lesion and IgG antibodies within 2 to 6 weeks.6 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends a 2-tiered approach when testing for Lyme disease.7 A screening test with high sensitivity such as an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or an immunofluorescence assay initially should be performed.7 If results of the screening test are equivocal or positive, secondary confirmatory testing should be performed via IgM, with or without IgG Western immunoblot assay.7 Biopsy with histologic evaluation can reveal nonspecific findings of vascular endothelial injury and increased mucin deposition. Patients with suspected Lyme disease should immediately be started on empiric treatment with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for a minimum of 10 days (14–28 days if there is concern for dissemination) to prevent post-Lyme sequelae.5 Our patient’s cutaneous lesions responded to oral doxycycline.

- Sweet’s syndrome. Mayo Clinic. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/sweets-syndrome /symptoms-causes/syc-20351117

- Steere AC. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:115-125.

- Lyme disease maps: most recent year. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 22, 2019. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/datasurveillance /maps-recent.html.

- Steere AC, Sikand VK. The present manifestations of Lyme disease and the outcomes of treatment. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2472-2474.

- Sanchez E, Vannier E, Wormser GP, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: a review. JAMA. 2016;315:1767-1777.

- Shapiro ED. Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease). Pediatr Rev. 2014; 35:500-509.

- Mead P, Petersen J, Hinckley A. Updated CDC recommendation for serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:703

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Erythema Chronicum Migrans

Empiric treatment with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days was initiated for suspected early disseminated Lyme disease manifesting as disseminated multifocal erythema chronicum migrans (Figure). Lyme screening immunoassay and confirmatory IgM Western blot testing subsequently were found to be positive. The clinical history of recent travel to an endemic area and tick bite combined with the recent onset of multifocal erythema migrans lesions, systemic symptoms, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and positive Lyme serology supported the diagnosis of Lyme disease.

The appropriate clinical context and cutaneous morphology are key when considering the differential diagnosis for multifocal annular lesions. Several entities comprised the differential diagnosis considered in our patient. Sweet syndrome is a neutrophilic dermatosis that can present with fever and varying painful cutaneous lesions. It often is associated with certain medications, underlying illnesses, and infections.1 Our patient’s lesions were not painful, and she had no notable medical history, recent infections, or new medication use, making Sweet syndrome unlikely. A fixed drug eruption was low on the differential, as the patient denied starting any new medications within the 3 months prior to presentation. Erythema multiforme is an acute-onset immunemediated condition of the skin and mucous membranes that typically affects young adults and often is associated with infection (eg, herpes simplex virus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae) or medication use. Cutaneous lesions typically are self-limited, less than 3 cm targets with 3 concentric distinct color zones, often with central bullae or erosions. Although erythema multiforme was higher on the differential, it was less likely, as the patient lacked mucosal lesions and did not have symptoms of underlying herpetic or mycoplasma infection, and the clinical picture was more consistent with Lyme disease. Lastly, the failure for individual skin lesions to resolve within

24 hours excluded the diagnosis of urticaria.

Lyme disease is a tick-borne illness caused by 3 species of the Borrelia spirochete: Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia afzelii, and Borrelia garinii.2 In the United States, the disease predominantly is caused by B burgdorferi that is endemic in the upper Midwest and Northeast regions.3 There are 3 stages of Lyme disease: early localized, early disseminated, and late disseminated disease. Early localized disease typically presents with a characteristic single erythema migrans (EM) lesion 3 to 30 days following a bite by the tick Ixodes scapularis.2 The EM lesion gradually can enlarge over a period of several days, reaching up to 12 inches in diameter.2 Early disseminated disease can occur weeks to months following a tick bite and may present with systemic symptoms, multiple widespread

EM lesions, neurologic features such as meningitis or facial nerve palsy, and/or cardiac manifestations such as atrioventricular block or myocarditis. Late disseminated disease can present with chronic arthritis or encephalopathy after months to years if the disease is left untreated.4

Early localized Lyme disease can be diagnosed clinically if the characteristic EM lesion is present in a patient who visited an endemic area. Laboratory testing and Lyme serology are neither required nor recommended in these cases, as the lesion often appears before adequate time has lapsed to develop an adaptive immune response to the organism.5 In contrast, Lyme serology should be ordered in any patient who meets all of the following criteria: (1) patient lives in or has recently traveled to an area endemic for Lyme disease, (2) presence of a risk factor for tick exposure, and (3) symptoms consistent with early disseminated or late Lyme disease. Patients with signs of early or late disseminated disease typically are seropositive, as IgM antibodies can be detected within 2 weeks of onset of the EM lesion and IgG antibodies within 2 to 6 weeks.6 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends a 2-tiered approach when testing for Lyme disease.7 A screening test with high sensitivity such as an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or an immunofluorescence assay initially should be performed.7 If results of the screening test are equivocal or positive, secondary confirmatory testing should be performed via IgM, with or without IgG Western immunoblot assay.7 Biopsy with histologic evaluation can reveal nonspecific findings of vascular endothelial injury and increased mucin deposition. Patients with suspected Lyme disease should immediately be started on empiric treatment with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for a minimum of 10 days (14–28 days if there is concern for dissemination) to prevent post-Lyme sequelae.5 Our patient’s cutaneous lesions responded to oral doxycycline.

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Erythema Chronicum Migrans

Empiric treatment with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days was initiated for suspected early disseminated Lyme disease manifesting as disseminated multifocal erythema chronicum migrans (Figure). Lyme screening immunoassay and confirmatory IgM Western blot testing subsequently were found to be positive. The clinical history of recent travel to an endemic area and tick bite combined with the recent onset of multifocal erythema migrans lesions, systemic symptoms, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and positive Lyme serology supported the diagnosis of Lyme disease.

The appropriate clinical context and cutaneous morphology are key when considering the differential diagnosis for multifocal annular lesions. Several entities comprised the differential diagnosis considered in our patient. Sweet syndrome is a neutrophilic dermatosis that can present with fever and varying painful cutaneous lesions. It often is associated with certain medications, underlying illnesses, and infections.1 Our patient’s lesions were not painful, and she had no notable medical history, recent infections, or new medication use, making Sweet syndrome unlikely. A fixed drug eruption was low on the differential, as the patient denied starting any new medications within the 3 months prior to presentation. Erythema multiforme is an acute-onset immunemediated condition of the skin and mucous membranes that typically affects young adults and often is associated with infection (eg, herpes simplex virus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae) or medication use. Cutaneous lesions typically are self-limited, less than 3 cm targets with 3 concentric distinct color zones, often with central bullae or erosions. Although erythema multiforme was higher on the differential, it was less likely, as the patient lacked mucosal lesions and did not have symptoms of underlying herpetic or mycoplasma infection, and the clinical picture was more consistent with Lyme disease. Lastly, the failure for individual skin lesions to resolve within

24 hours excluded the diagnosis of urticaria.

Lyme disease is a tick-borne illness caused by 3 species of the Borrelia spirochete: Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia afzelii, and Borrelia garinii.2 In the United States, the disease predominantly is caused by B burgdorferi that is endemic in the upper Midwest and Northeast regions.3 There are 3 stages of Lyme disease: early localized, early disseminated, and late disseminated disease. Early localized disease typically presents with a characteristic single erythema migrans (EM) lesion 3 to 30 days following a bite by the tick Ixodes scapularis.2 The EM lesion gradually can enlarge over a period of several days, reaching up to 12 inches in diameter.2 Early disseminated disease can occur weeks to months following a tick bite and may present with systemic symptoms, multiple widespread

EM lesions, neurologic features such as meningitis or facial nerve palsy, and/or cardiac manifestations such as atrioventricular block or myocarditis. Late disseminated disease can present with chronic arthritis or encephalopathy after months to years if the disease is left untreated.4

Early localized Lyme disease can be diagnosed clinically if the characteristic EM lesion is present in a patient who visited an endemic area. Laboratory testing and Lyme serology are neither required nor recommended in these cases, as the lesion often appears before adequate time has lapsed to develop an adaptive immune response to the organism.5 In contrast, Lyme serology should be ordered in any patient who meets all of the following criteria: (1) patient lives in or has recently traveled to an area endemic for Lyme disease, (2) presence of a risk factor for tick exposure, and (3) symptoms consistent with early disseminated or late Lyme disease. Patients with signs of early or late disseminated disease typically are seropositive, as IgM antibodies can be detected within 2 weeks of onset of the EM lesion and IgG antibodies within 2 to 6 weeks.6 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends a 2-tiered approach when testing for Lyme disease.7 A screening test with high sensitivity such as an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or an immunofluorescence assay initially should be performed.7 If results of the screening test are equivocal or positive, secondary confirmatory testing should be performed via IgM, with or without IgG Western immunoblot assay.7 Biopsy with histologic evaluation can reveal nonspecific findings of vascular endothelial injury and increased mucin deposition. Patients with suspected Lyme disease should immediately be started on empiric treatment with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for a minimum of 10 days (14–28 days if there is concern for dissemination) to prevent post-Lyme sequelae.5 Our patient’s cutaneous lesions responded to oral doxycycline.

- Sweet’s syndrome. Mayo Clinic. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/sweets-syndrome /symptoms-causes/syc-20351117

- Steere AC. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:115-125.

- Lyme disease maps: most recent year. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 22, 2019. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/datasurveillance /maps-recent.html.

- Steere AC, Sikand VK. The present manifestations of Lyme disease and the outcomes of treatment. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2472-2474.

- Sanchez E, Vannier E, Wormser GP, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: a review. JAMA. 2016;315:1767-1777.

- Shapiro ED. Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease). Pediatr Rev. 2014; 35:500-509.

- Mead P, Petersen J, Hinckley A. Updated CDC recommendation for serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:703

- Sweet’s syndrome. Mayo Clinic. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/sweets-syndrome /symptoms-causes/syc-20351117

- Steere AC. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:115-125.

- Lyme disease maps: most recent year. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 22, 2019. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/datasurveillance /maps-recent.html.

- Steere AC, Sikand VK. The present manifestations of Lyme disease and the outcomes of treatment. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2472-2474.

- Sanchez E, Vannier E, Wormser GP, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: a review. JAMA. 2016;315:1767-1777.

- Shapiro ED. Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease). Pediatr Rev. 2014; 35:500-509.

- Mead P, Petersen J, Hinckley A. Updated CDC recommendation for serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:703

An otherwise healthy 78-year-old woman presented with a diffuse, mildly itchy rash of 5 days’ duration with associated fatigue, chills, decreased appetite, and nausea. She reported waking up with her arms “feeling like they weigh a ton.” She denied any pain, bleeding, or oozing and was unsure if new spots were continuing to develop. The patient reported having allergies to numerous medications but denied any new medications or recent illnesses. She had recently spent time on a farm in Minnesota, and upon further questioning she recalled a tick bite 2 months prior to presentation. She stated that she removed the nonengorged tick and that it could not have been attached for more than 24 hours. Her medical and family history were unremarkable. Physical examination showed multiple annular pink plaques with a central violaceous hue in a generalized distribution involving the face, trunk, arms, and legs with mild erythema of the palms. The plantar surfaces were clear, and there was no evidence of lymphadenopathy. The remainder of the physical examination and review of systems was negative. Laboratory screening was notable for an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level with negative antinuclear antibodies.

Pediatric Dermatology Emergencies

Many pediatric skin conditions can be safely monitored with minimal intervention, but certain skin conditions are emergent and require immediate attention and proper assessment of the neonate, infant, or child. The skin may provide the first presentation of a potentially fatal disease with serious sequelae. Cutaneous findings may indicate the need for further evaluation. Therefore, it is important to differentiate skin conditions with benign etiologies from those that require immediate diagnosis and treatment, as early intervention of some of these conditions can be lifesaving. Herein, we discuss pertinent pediatric dermatology emergencies that dermatologists should keep in mind so that these diagnoses are never missed.

Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome

Presentation

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS), or Ritter disease, is a potentially fatal pediatric emergency, especially in newborns.1 The mortality rate for SSSS in the United States is 3.6% to 11% in children.2 It typically presents with a prodrome of tenderness, fever, and confluent erythematous patches on the folds of the skin such as the groin, axillae, nose, and ears, with eventual spread to the legs and trunk.1,2 Within 24 to 48 hours of symptom onset, blistering and fluid accumulation will appear diffusely. Bullae are flaccid, and tangential and gentle pressure on involved unblistered skin may lead to shearing of the epithelium, which is a positive Nikolsky sign.1,2

Causes

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is caused by exfoliative toxins A and B, toxigenic strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Exfoliative toxins A and B are serine proteases that target and cleave desmoglein 1, which binds keratinocytes in the stratum granulosum.1,3 Exfoliative toxins disrupt the adhesion of keratinocytes, resulting in bullae formation and subsequently diffuse sheetlike desquamation.1,4,5 Although up to 30% of the human population are asymptomatically and permanently colonized with nasal S aureus,6 the exfoliative toxins are produced by only 5% of species.1

In neonates, the immune and renal systems are underdeveloped; therefore, patients are susceptible to SSSS due to lack of neutralizing antibodies and decreased renal toxin excretion.4 Potential complications of SSSS are deeper soft-tissue infection, septicemia (blood-borne infection), and fluid and electrolyte imbalance.1,4

Diagnosis and Treatment

The condition is diagnosed clinically based on the findings of tender erythroderma, bullae, and desquamation with a scalded appearance, especially in friction zones; periorificial crusting; positive Nikolsky sign; and lack of mucosal involvement (Figure 1).1 Histopathology can aid in complicated clinical scenarios as well as culture from affected areas, including the upper respiratory tract, diaper region, and umbilicus.1,4 Hospitalization is required for SSSS for intravenous antibiotics, fluids, and electrolyte repletion.

Differential Diagnosis

There are multiple diagnoses to consider in the setting of flaccid bullae in the pediatric population. Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis also can present with fever and superficial desquamation or bullae; however, exposure to medications and mucosal involvement often are absent in SSSS (Figure 2).2 Pemphigus, particularly paraneoplastic pemphigus, also often includes mucosal involvement and scalding thermal burns that are often geometric or focal. Epidermolysis bullosa and toxic shock syndrome also should be considered.1

Impetigo

Presentation

Impetigo is the most common bacterial skin infection in children caused by S aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes.7-9 It begins as erythematous papules transitioning to thin-walled vesicles that rapidly rupture and result in honey-crusted papules.7,9,10 Individuals of any age can be affected by nonbullous impetigo, but it is the most common skin infection in children aged 2 to 5 years.7

Bullous impetigo primarily is seen in children, especially infants, and rarely can occur in teenagers or adults.7 It most commonly is caused by the exfoliative toxins of S aureus. Bullous impetigo presents as small vesicles that may converge into larger flaccid bullae or pustules.7-10 Once the bullae rupture, an erythematous base with a collarette of scale remains without the formation of a honey-colored crust.8 Bullous impetigo usually affects moist intertriginous areas such as the axillae, neck, and diaper area8,10 (Figure 3). Complications may result in cellulitis, septicemia, osteomyelitis, poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis associated with S pyogenes, and S aureus–induced SSSS.7-9

Diagnosis

Nonbullous and bullous impetigo are largely clinical diagnoses that can be confirmed by culture of a vesicle or pustular fluid.10 Treatment of impetigo includes topical or systemic antibiotics.7,10 Patients should be advised to keep lesions covered and avoid contact with others until all lesions resolve, as lesions are contagious.9

Eczema Herpeticum

Presentation

Eczema herpeticum (EH), also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption, is a disseminated herpes simplex virus infection of impaired skin, most commonly in patients with atopic dermatitis (AD).11 Eczema herpeticum presents as a widespread eruption of erythematous monomorphic vesicles that progress to punched-out erosions with hemorrhagic crusting (Figure 4). Patients may have associated fever or lymphadenopathy.12,13

Causes

The number of children hospitalized annually for EH in the United States is approximately 4 to 7 cases per million children. Less than 3% of pediatric AD patients are affected, with a particularly increased risk in patients with severe and earlier-onset AD.12-15 Patients with AD have skin barrier defects, and decreased IFN-γ expression and cathelicidins predispose patients with AD to developing EH.12,16,17

Diagnosis

Viral polymerase chain reaction for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 is the standard for confirmatory diagnosis. Herpes simplex virus cultures from cutaneous scrapings, direct fluorescent antibody testing, or Tzanck test revealing multinucleated giant cells also may help establish the diagnosis.11,12,17

Management

Individuals with severe AD and other dermatologic conditions with cutaneous barrier compromise are at risk for developing EH, which is a medical emergency requiring hospitalization and prompt treatment with antiviral therapy such as acyclovir, often intravenously, as death can result if left untreated.11,17 Topical or systemic antibiotic therapy should be initiated if there is suspicion for secondary bacterial superinfection. Patients should be evaluated for multiorgan involvement such as keratoconjunctivitis, meningitis, encephalitis, and systemic viremia due to increased mortality, especially in infants.12,15,16

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Presentation

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) has a variable clinical presentation and can involve a single or multiple organ systems, including the bones and skin. Cutaneous LCH can present as violaceous papules, nodules, or ulcerations and crusted erosions (Figure 5). The lymph nodes, liver, spleen, oral mucosa, and respiratory and central nervous systems also may be involved.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis affects individuals of any age group but more often is seen in pediatric patients. The incidence of LCH is approximately 4.6 cases per million children.18 The pathogenesis is secondary to pathologic Langerhans cells, characterized as a clonal myeloid malignancy and dysregulation of the immune system.18,19

Diagnosis

A thorough physical examination is essential in patients with suspected LCH. Additionally, diagnosis of LCH is heavily based on histopathology of tissue from the involved organ system(s) with features of positive S-100 protein, CD1a, and CD207, and identification of Birbeck granules.20 Imaging and laboratory studies also are indicated and can include a skeletal survey (to assess osteolytic and organ involvement), a complete hematologic panel, coagulation studies, and liver function tests.18,21

Management

Management of LCH varies based on the organ system(s) involved along with the extent of the disease. Dermatology referral may be indicated in patients presenting with nonresolving cutaneous lesions as well as in severe cases. Single-organ and multisystem disease may require one treatment modality or a combination of chemotherapy, surgery, radiation, and/or immunotherapy.21

Infantile Hemangioma

Presentation

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common benign tumor of infancy and usually is apparent a few weeks after birth. Lesions appear as bright red papules, nodules, or plaques. Deep or subcutaneous lesions present as raised, flesh-colored nodules with a blue hue and bruiselike appearance with or without a central patch of telangiectasia22-24 (Figure 6). Although all IHs eventually resolve, residual skin changes such as scarring, atrophy, and fibrosis can persist.24

The incidence of IH has been reported to occur in up to 4% to 5% of infants in the United States.23,25 Infantile hemangiomas also have been found to be more common among white, preterm, and multiple-gestation infants.25 The proposed pathogenesis of IHs includes angiogenic and vasogenic factors that cause rapid proliferation of blood vessels, likely driven by tissue hypoxia.23,26,27

Diagnosis

Infantile hemangioma is diagnosed clinically; however, immunohistochemical staining showing positivity for glucose transporter 1 also is helpful.26,27 Imaging modalities such as ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging also can be utilized to visualize the extent of lesions if necessary.25

Management

Around 15% to 25% of IHs are considered complicated and require intervention.25,27 Infantile hemangiomas can interfere with function depending on location or have potentially fatal complications. Based on the location and extent of involvement, these findings can include ulceration; hemorrhage; impairment of feeding, hearing, and/or vision; facial deformities; airway obstruction; hypothyroidism; and congestive heart failure.25,28 Early treatment with topical or oral beta-blockers is imperative for potentially life-threatening IHs, which can be seen due to large size or dangerous location.28,29 Because the rapid proliferative phase of IHs is thought to begin around 6 weeks of life, treatment should be initiated as early as possible. Initiation of beta-blocker therapy in the first few months of life can prevent functional impairment, ulceration, and permanent cosmetic changes. Additionally, surgery or pulsed dye laser treatment have been found to be effective for skin changes found after involution of IH.25,29

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for IH includes vascular malformations, which are present at birth and do not undergo rapid proliferation; sarcoma; and kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, which causes the Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon secondary to platelet trapping. Careful attention to the history of the skin lesion provides good support for diagnosis of IH in most cases.

IgA Vasculitis

Presentation

IgA vasculitis, or Henoch-Schönlein purpura, classically presents as a tetrad of palpable purpura, acute-onset arthritis or arthralgia, abdominal pain, and renal disease with proteinuria or hematuria.30 Skin involvement is seen in almost all cases and is essential for diagnosis of IgA vasculitis. The initial dermatosis may be pruritic and present as an erythematous macular or urticarial wheal that evolves into petechiae, along with palpable purpura that is most frequently located on the legs or buttocks (Figure 7).30-34

IgA vasculitis is an immune-mediated small vessel vasculitis with deposition of IgA in the small vessels. The underlying cause remains unknown, though infection, dietary allergens, drugs, vaccinations, and chemical triggers have been recognized in literature.32,35,36 IgA vasculitis is largely a pediatric diagnosis, with 90% of affected individuals younger than 10 years worldwide.37 In the pediatric population, the incidence has been reported to be 3 to 26.7 cases per 100,000 children.32

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on the clinical presentation and histopathology.30 On direct immunofluorescence, IgA deposition is seen in the vessel walls.35 Laboratory testing is not diagnostic, but urinalysis is mandatory to identify involvement of renal vasculature. Imaging studies may be used in patients with abdominal symptoms, as an ultrasound can be used to visualize bowel structure and abnormalities such as intussusception.33

Management

The majority of cases of IgA vasculitis recover spontaneously, with patients requiring hospital admission based on severity of symptoms.30 The primary approach to management involves providing supportive care including hydration, adequate rest, and symptomatic pain relief of the joints and abdomen with oral analgesics. Systemic corticosteroids or steroid-sparing agents such as dapsone or colchicine can be used to treat cutaneous manifestations in addition to severe pain symptoms.30,31 Patients with IgA vasculitis must be monitored for proteinuria or hematuria to assess the extent of renal involvement. Although much more common in adults, long-term renal impairment can result from childhood cases of IgA vasculitis.34

Final Thoughts

Pediatric dermatology emergencies can be difficult to detect and accurately diagnose. Many of these diseases are potential emergencies that that may result in delayed treatment and considerable morbidity and mortality if missed. Clinicians should be aware that timely recognition and diagnosis, along with possible referral to pediatric dermatology, are essential to avoid complications.

- Leung AKC, Barankin B, Leong KF. Staphylococcal-scalded skin syndrome: evaluation, diagnosis, and management. World J Pediatr. 2018;14:116-120.

- Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome: diagnosis and management in children and adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1418-1423.

- Davidson J, Polly S, Hayes P, et al. Recurrent staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in an extremely low-birth-weight neonate. AJP Rep. 2017;7:E134-E137.

- Mishra AK, Yadav P, Mishra A. A systemic review on staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS): a rare and critical disease of neonates. Open Microbiol J. 2016;10:150-159.

- Berk D. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Cancer Therapy Advisor website. https://www.cancertherapyadvisor.com/home/decision-support-in-medicine/pediatrics/staphylococcal-scalded-skin-syndrome/. Published 2017. Accessed February 19, 2020.

- Sakr A, Brégeon F, Mège JL, et al. Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization: an update on mechanisms, epidemiology, risk factors, and subsequent infections [published online October 8, 2018]. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2419.

- Pereira LB. Impetigo review. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:293-299.

- Nardi NM, Schaefer TJ. Impetigo. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430974/. Accessed February 21, 2020.

- Koning S, van der Sande R, Verhagen AP, et al. Interventions for impetigo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;1:CD003261.

- Sommer LL, Reboli AC, Heymann WR. Bacterial diseases. In: Bolognia, JL Schaffer, JV Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1259-1295.

- Micali G, Lacarrubba F. Eczema herpeticum. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:e9.

- Leung DY. Why is eczema herpeticum unexpectedly rare? Antiviral Res. 2013;98:153-157.

- Seegräber M, Worm M, Werfel T, et al. Recurrent eczema herpeticum—a retrospective European multicenter study evaluating the clinical characteristics of eczema herpeticum cases in atopic dermatitis patients [published online November 16, 2019]. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.16090.

- Sun D, Ong PY. Infectious complications in atopic dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2017;37:75-93.

- Hsu DY, Shinkai K, Silverberg JI. Epidemiology of eczema herpeticum in hospitalized U.S. children: analysis of a nationwide cohort [published online September 17, 2018]. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:265-272.

- Leung DY, Gao PS, Grigoryev DN, et al. Human atopic dermatitis complicated by eczema herpeticum is associated with abnormalities in IFN-γ response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:965-73.e1-5.

- Darji K, Frisch S, Adjei Boakye E, et al. Characterization of children with recurrent eczema herpeticum and response to treatment with interferon-gamma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:686-689.

- Allen CE, Merad M, McClain KL. Langerhans-cell histiocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:856-868.

- Abla O, Weitzman S. Treatment of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: role of BRAF/MAPK inhibition. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2015;2015:565-570.

- Allen CE, Li L, Peters TL, et al. Cell-specific gene expression in Langerhans cell histiocytosis lesions reveals a distinct profile compared with epidermal Langerhans cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:4557-4567.

- Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work-up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184.

- Holland KE, Drolet BA. Infantile hemangioma [published online August 21, 2010]. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2010;57:1069-1083.

- Chen TS, Eichenfield LF, Friedlander SF. Infantile hemangiomas: an update on pathogenesis and therapy. Pediatrics. 2013;131:99-108.

- George A, Mani V, Noufal A. Update on the classification of hemangioma. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18(suppl 1):S117-S120.

- Darrow DH, Greene AK, Mancini AJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of infantile hemangioma. Pediatrics. 2015;136:786-791.

- Munden A, Butschek R, Tom WL, et al. Prospective study of infantile haemangiomas: incidence, clinical characteristics and association with placental anomalies. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:907-913.

- de Jong S, Itinteang T, Withers AH, et al. Does hypoxia play a role in infantile hemangioma? Arch Dermatol Res. 2016;308:219-227.

- Hogeling M, Adams S, Wargon O. A randomized controlled trial of propranolol for infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2011;128:E259-E266.

- Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas [published online January 2019]. Pediatrics. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-3475.

- Sohagia AB, Gunturu SG, Tong TR, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura—a case report and review of the literature [published online May 23, 2010]. Gastroenterol Res Pract. doi:10.1155/2010/597648.

- Rigante D, Castellazzi L, Bosco A, et al. Is there a crossroad between infections, genetics, and Henoch-Schönlein purpura? Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:1016-1021.

- Piram M, Mahr A. Epidemiology of immunoglobulin A vasculitis (Henoch–Schönlein): current state of knowledge. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013;25:171-178.

- Carlson JA. The histological assessment of cutaneous vasculitis. Histopathology. 2010;56:3-23.

- Eleftheriou D, Batu ED, Ozen S, et al. Vasculitis in children. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;30:I94-I103.

- van Timmeren MM, Heeringa P, Kallenberg CG. Infectious triggers for vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26:416-423.

- Scott DGI, Watts RA. Epidemiology and clinical features of systemic vasculitis [published online July 11, 2013]. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2013;17:607-610.

- He X, Yu C, Zhao P, et al. The genetics of Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:1387-1395.

Many pediatric skin conditions can be safely monitored with minimal intervention, but certain skin conditions are emergent and require immediate attention and proper assessment of the neonate, infant, or child. The skin may provide the first presentation of a potentially fatal disease with serious sequelae. Cutaneous findings may indicate the need for further evaluation. Therefore, it is important to differentiate skin conditions with benign etiologies from those that require immediate diagnosis and treatment, as early intervention of some of these conditions can be lifesaving. Herein, we discuss pertinent pediatric dermatology emergencies that dermatologists should keep in mind so that these diagnoses are never missed.

Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome

Presentation

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS), or Ritter disease, is a potentially fatal pediatric emergency, especially in newborns.1 The mortality rate for SSSS in the United States is 3.6% to 11% in children.2 It typically presents with a prodrome of tenderness, fever, and confluent erythematous patches on the folds of the skin such as the groin, axillae, nose, and ears, with eventual spread to the legs and trunk.1,2 Within 24 to 48 hours of symptom onset, blistering and fluid accumulation will appear diffusely. Bullae are flaccid, and tangential and gentle pressure on involved unblistered skin may lead to shearing of the epithelium, which is a positive Nikolsky sign.1,2

Causes

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is caused by exfoliative toxins A and B, toxigenic strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Exfoliative toxins A and B are serine proteases that target and cleave desmoglein 1, which binds keratinocytes in the stratum granulosum.1,3 Exfoliative toxins disrupt the adhesion of keratinocytes, resulting in bullae formation and subsequently diffuse sheetlike desquamation.1,4,5 Although up to 30% of the human population are asymptomatically and permanently colonized with nasal S aureus,6 the exfoliative toxins are produced by only 5% of species.1

In neonates, the immune and renal systems are underdeveloped; therefore, patients are susceptible to SSSS due to lack of neutralizing antibodies and decreased renal toxin excretion.4 Potential complications of SSSS are deeper soft-tissue infection, septicemia (blood-borne infection), and fluid and electrolyte imbalance.1,4

Diagnosis and Treatment

The condition is diagnosed clinically based on the findings of tender erythroderma, bullae, and desquamation with a scalded appearance, especially in friction zones; periorificial crusting; positive Nikolsky sign; and lack of mucosal involvement (Figure 1).1 Histopathology can aid in complicated clinical scenarios as well as culture from affected areas, including the upper respiratory tract, diaper region, and umbilicus.1,4 Hospitalization is required for SSSS for intravenous antibiotics, fluids, and electrolyte repletion.

Differential Diagnosis

There are multiple diagnoses to consider in the setting of flaccid bullae in the pediatric population. Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis also can present with fever and superficial desquamation or bullae; however, exposure to medications and mucosal involvement often are absent in SSSS (Figure 2).2 Pemphigus, particularly paraneoplastic pemphigus, also often includes mucosal involvement and scalding thermal burns that are often geometric or focal. Epidermolysis bullosa and toxic shock syndrome also should be considered.1

Impetigo

Presentation

Impetigo is the most common bacterial skin infection in children caused by S aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes.7-9 It begins as erythematous papules transitioning to thin-walled vesicles that rapidly rupture and result in honey-crusted papules.7,9,10 Individuals of any age can be affected by nonbullous impetigo, but it is the most common skin infection in children aged 2 to 5 years.7

Bullous impetigo primarily is seen in children, especially infants, and rarely can occur in teenagers or adults.7 It most commonly is caused by the exfoliative toxins of S aureus. Bullous impetigo presents as small vesicles that may converge into larger flaccid bullae or pustules.7-10 Once the bullae rupture, an erythematous base with a collarette of scale remains without the formation of a honey-colored crust.8 Bullous impetigo usually affects moist intertriginous areas such as the axillae, neck, and diaper area8,10 (Figure 3). Complications may result in cellulitis, septicemia, osteomyelitis, poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis associated with S pyogenes, and S aureus–induced SSSS.7-9

Diagnosis

Nonbullous and bullous impetigo are largely clinical diagnoses that can be confirmed by culture of a vesicle or pustular fluid.10 Treatment of impetigo includes topical or systemic antibiotics.7,10 Patients should be advised to keep lesions covered and avoid contact with others until all lesions resolve, as lesions are contagious.9

Eczema Herpeticum

Presentation

Eczema herpeticum (EH), also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption, is a disseminated herpes simplex virus infection of impaired skin, most commonly in patients with atopic dermatitis (AD).11 Eczema herpeticum presents as a widespread eruption of erythematous monomorphic vesicles that progress to punched-out erosions with hemorrhagic crusting (Figure 4). Patients may have associated fever or lymphadenopathy.12,13

Causes

The number of children hospitalized annually for EH in the United States is approximately 4 to 7 cases per million children. Less than 3% of pediatric AD patients are affected, with a particularly increased risk in patients with severe and earlier-onset AD.12-15 Patients with AD have skin barrier defects, and decreased IFN-γ expression and cathelicidins predispose patients with AD to developing EH.12,16,17

Diagnosis

Viral polymerase chain reaction for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 is the standard for confirmatory diagnosis. Herpes simplex virus cultures from cutaneous scrapings, direct fluorescent antibody testing, or Tzanck test revealing multinucleated giant cells also may help establish the diagnosis.11,12,17

Management

Individuals with severe AD and other dermatologic conditions with cutaneous barrier compromise are at risk for developing EH, which is a medical emergency requiring hospitalization and prompt treatment with antiviral therapy such as acyclovir, often intravenously, as death can result if left untreated.11,17 Topical or systemic antibiotic therapy should be initiated if there is suspicion for secondary bacterial superinfection. Patients should be evaluated for multiorgan involvement such as keratoconjunctivitis, meningitis, encephalitis, and systemic viremia due to increased mortality, especially in infants.12,15,16

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Presentation

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) has a variable clinical presentation and can involve a single or multiple organ systems, including the bones and skin. Cutaneous LCH can present as violaceous papules, nodules, or ulcerations and crusted erosions (Figure 5). The lymph nodes, liver, spleen, oral mucosa, and respiratory and central nervous systems also may be involved.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis affects individuals of any age group but more often is seen in pediatric patients. The incidence of LCH is approximately 4.6 cases per million children.18 The pathogenesis is secondary to pathologic Langerhans cells, characterized as a clonal myeloid malignancy and dysregulation of the immune system.18,19

Diagnosis

A thorough physical examination is essential in patients with suspected LCH. Additionally, diagnosis of LCH is heavily based on histopathology of tissue from the involved organ system(s) with features of positive S-100 protein, CD1a, and CD207, and identification of Birbeck granules.20 Imaging and laboratory studies also are indicated and can include a skeletal survey (to assess osteolytic and organ involvement), a complete hematologic panel, coagulation studies, and liver function tests.18,21

Management

Management of LCH varies based on the organ system(s) involved along with the extent of the disease. Dermatology referral may be indicated in patients presenting with nonresolving cutaneous lesions as well as in severe cases. Single-organ and multisystem disease may require one treatment modality or a combination of chemotherapy, surgery, radiation, and/or immunotherapy.21

Infantile Hemangioma

Presentation

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common benign tumor of infancy and usually is apparent a few weeks after birth. Lesions appear as bright red papules, nodules, or plaques. Deep or subcutaneous lesions present as raised, flesh-colored nodules with a blue hue and bruiselike appearance with or without a central patch of telangiectasia22-24 (Figure 6). Although all IHs eventually resolve, residual skin changes such as scarring, atrophy, and fibrosis can persist.24

The incidence of IH has been reported to occur in up to 4% to 5% of infants in the United States.23,25 Infantile hemangiomas also have been found to be more common among white, preterm, and multiple-gestation infants.25 The proposed pathogenesis of IHs includes angiogenic and vasogenic factors that cause rapid proliferation of blood vessels, likely driven by tissue hypoxia.23,26,27

Diagnosis

Infantile hemangioma is diagnosed clinically; however, immunohistochemical staining showing positivity for glucose transporter 1 also is helpful.26,27 Imaging modalities such as ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging also can be utilized to visualize the extent of lesions if necessary.25

Management

Around 15% to 25% of IHs are considered complicated and require intervention.25,27 Infantile hemangiomas can interfere with function depending on location or have potentially fatal complications. Based on the location and extent of involvement, these findings can include ulceration; hemorrhage; impairment of feeding, hearing, and/or vision; facial deformities; airway obstruction; hypothyroidism; and congestive heart failure.25,28 Early treatment with topical or oral beta-blockers is imperative for potentially life-threatening IHs, which can be seen due to large size or dangerous location.28,29 Because the rapid proliferative phase of IHs is thought to begin around 6 weeks of life, treatment should be initiated as early as possible. Initiation of beta-blocker therapy in the first few months of life can prevent functional impairment, ulceration, and permanent cosmetic changes. Additionally, surgery or pulsed dye laser treatment have been found to be effective for skin changes found after involution of IH.25,29

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for IH includes vascular malformations, which are present at birth and do not undergo rapid proliferation; sarcoma; and kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, which causes the Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon secondary to platelet trapping. Careful attention to the history of the skin lesion provides good support for diagnosis of IH in most cases.

IgA Vasculitis

Presentation

IgA vasculitis, or Henoch-Schönlein purpura, classically presents as a tetrad of palpable purpura, acute-onset arthritis or arthralgia, abdominal pain, and renal disease with proteinuria or hematuria.30 Skin involvement is seen in almost all cases and is essential for diagnosis of IgA vasculitis. The initial dermatosis may be pruritic and present as an erythematous macular or urticarial wheal that evolves into petechiae, along with palpable purpura that is most frequently located on the legs or buttocks (Figure 7).30-34

IgA vasculitis is an immune-mediated small vessel vasculitis with deposition of IgA in the small vessels. The underlying cause remains unknown, though infection, dietary allergens, drugs, vaccinations, and chemical triggers have been recognized in literature.32,35,36 IgA vasculitis is largely a pediatric diagnosis, with 90% of affected individuals younger than 10 years worldwide.37 In the pediatric population, the incidence has been reported to be 3 to 26.7 cases per 100,000 children.32

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on the clinical presentation and histopathology.30 On direct immunofluorescence, IgA deposition is seen in the vessel walls.35 Laboratory testing is not diagnostic, but urinalysis is mandatory to identify involvement of renal vasculature. Imaging studies may be used in patients with abdominal symptoms, as an ultrasound can be used to visualize bowel structure and abnormalities such as intussusception.33

Management

The majority of cases of IgA vasculitis recover spontaneously, with patients requiring hospital admission based on severity of symptoms.30 The primary approach to management involves providing supportive care including hydration, adequate rest, and symptomatic pain relief of the joints and abdomen with oral analgesics. Systemic corticosteroids or steroid-sparing agents such as dapsone or colchicine can be used to treat cutaneous manifestations in addition to severe pain symptoms.30,31 Patients with IgA vasculitis must be monitored for proteinuria or hematuria to assess the extent of renal involvement. Although much more common in adults, long-term renal impairment can result from childhood cases of IgA vasculitis.34

Final Thoughts

Pediatric dermatology emergencies can be difficult to detect and accurately diagnose. Many of these diseases are potential emergencies that that may result in delayed treatment and considerable morbidity and mortality if missed. Clinicians should be aware that timely recognition and diagnosis, along with possible referral to pediatric dermatology, are essential to avoid complications.

Many pediatric skin conditions can be safely monitored with minimal intervention, but certain skin conditions are emergent and require immediate attention and proper assessment of the neonate, infant, or child. The skin may provide the first presentation of a potentially fatal disease with serious sequelae. Cutaneous findings may indicate the need for further evaluation. Therefore, it is important to differentiate skin conditions with benign etiologies from those that require immediate diagnosis and treatment, as early intervention of some of these conditions can be lifesaving. Herein, we discuss pertinent pediatric dermatology emergencies that dermatologists should keep in mind so that these diagnoses are never missed.

Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome

Presentation

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS), or Ritter disease, is a potentially fatal pediatric emergency, especially in newborns.1 The mortality rate for SSSS in the United States is 3.6% to 11% in children.2 It typically presents with a prodrome of tenderness, fever, and confluent erythematous patches on the folds of the skin such as the groin, axillae, nose, and ears, with eventual spread to the legs and trunk.1,2 Within 24 to 48 hours of symptom onset, blistering and fluid accumulation will appear diffusely. Bullae are flaccid, and tangential and gentle pressure on involved unblistered skin may lead to shearing of the epithelium, which is a positive Nikolsky sign.1,2

Causes

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is caused by exfoliative toxins A and B, toxigenic strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Exfoliative toxins A and B are serine proteases that target and cleave desmoglein 1, which binds keratinocytes in the stratum granulosum.1,3 Exfoliative toxins disrupt the adhesion of keratinocytes, resulting in bullae formation and subsequently diffuse sheetlike desquamation.1,4,5 Although up to 30% of the human population are asymptomatically and permanently colonized with nasal S aureus,6 the exfoliative toxins are produced by only 5% of species.1

In neonates, the immune and renal systems are underdeveloped; therefore, patients are susceptible to SSSS due to lack of neutralizing antibodies and decreased renal toxin excretion.4 Potential complications of SSSS are deeper soft-tissue infection, septicemia (blood-borne infection), and fluid and electrolyte imbalance.1,4

Diagnosis and Treatment

The condition is diagnosed clinically based on the findings of tender erythroderma, bullae, and desquamation with a scalded appearance, especially in friction zones; periorificial crusting; positive Nikolsky sign; and lack of mucosal involvement (Figure 1).1 Histopathology can aid in complicated clinical scenarios as well as culture from affected areas, including the upper respiratory tract, diaper region, and umbilicus.1,4 Hospitalization is required for SSSS for intravenous antibiotics, fluids, and electrolyte repletion.

Differential Diagnosis

There are multiple diagnoses to consider in the setting of flaccid bullae in the pediatric population. Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis also can present with fever and superficial desquamation or bullae; however, exposure to medications and mucosal involvement often are absent in SSSS (Figure 2).2 Pemphigus, particularly paraneoplastic pemphigus, also often includes mucosal involvement and scalding thermal burns that are often geometric or focal. Epidermolysis bullosa and toxic shock syndrome also should be considered.1

Impetigo

Presentation

Impetigo is the most common bacterial skin infection in children caused by S aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes.7-9 It begins as erythematous papules transitioning to thin-walled vesicles that rapidly rupture and result in honey-crusted papules.7,9,10 Individuals of any age can be affected by nonbullous impetigo, but it is the most common skin infection in children aged 2 to 5 years.7

Bullous impetigo primarily is seen in children, especially infants, and rarely can occur in teenagers or adults.7 It most commonly is caused by the exfoliative toxins of S aureus. Bullous impetigo presents as small vesicles that may converge into larger flaccid bullae or pustules.7-10 Once the bullae rupture, an erythematous base with a collarette of scale remains without the formation of a honey-colored crust.8 Bullous impetigo usually affects moist intertriginous areas such as the axillae, neck, and diaper area8,10 (Figure 3). Complications may result in cellulitis, septicemia, osteomyelitis, poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis associated with S pyogenes, and S aureus–induced SSSS.7-9

Diagnosis

Nonbullous and bullous impetigo are largely clinical diagnoses that can be confirmed by culture of a vesicle or pustular fluid.10 Treatment of impetigo includes topical or systemic antibiotics.7,10 Patients should be advised to keep lesions covered and avoid contact with others until all lesions resolve, as lesions are contagious.9

Eczema Herpeticum

Presentation

Eczema herpeticum (EH), also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption, is a disseminated herpes simplex virus infection of impaired skin, most commonly in patients with atopic dermatitis (AD).11 Eczema herpeticum presents as a widespread eruption of erythematous monomorphic vesicles that progress to punched-out erosions with hemorrhagic crusting (Figure 4). Patients may have associated fever or lymphadenopathy.12,13

Causes

The number of children hospitalized annually for EH in the United States is approximately 4 to 7 cases per million children. Less than 3% of pediatric AD patients are affected, with a particularly increased risk in patients with severe and earlier-onset AD.12-15 Patients with AD have skin barrier defects, and decreased IFN-γ expression and cathelicidins predispose patients with AD to developing EH.12,16,17

Diagnosis

Viral polymerase chain reaction for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 is the standard for confirmatory diagnosis. Herpes simplex virus cultures from cutaneous scrapings, direct fluorescent antibody testing, or Tzanck test revealing multinucleated giant cells also may help establish the diagnosis.11,12,17

Management

Individuals with severe AD and other dermatologic conditions with cutaneous barrier compromise are at risk for developing EH, which is a medical emergency requiring hospitalization and prompt treatment with antiviral therapy such as acyclovir, often intravenously, as death can result if left untreated.11,17 Topical or systemic antibiotic therapy should be initiated if there is suspicion for secondary bacterial superinfection. Patients should be evaluated for multiorgan involvement such as keratoconjunctivitis, meningitis, encephalitis, and systemic viremia due to increased mortality, especially in infants.12,15,16

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Presentation

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) has a variable clinical presentation and can involve a single or multiple organ systems, including the bones and skin. Cutaneous LCH can present as violaceous papules, nodules, or ulcerations and crusted erosions (Figure 5). The lymph nodes, liver, spleen, oral mucosa, and respiratory and central nervous systems also may be involved.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis affects individuals of any age group but more often is seen in pediatric patients. The incidence of LCH is approximately 4.6 cases per million children.18 The pathogenesis is secondary to pathologic Langerhans cells, characterized as a clonal myeloid malignancy and dysregulation of the immune system.18,19

Diagnosis

A thorough physical examination is essential in patients with suspected LCH. Additionally, diagnosis of LCH is heavily based on histopathology of tissue from the involved organ system(s) with features of positive S-100 protein, CD1a, and CD207, and identification of Birbeck granules.20 Imaging and laboratory studies also are indicated and can include a skeletal survey (to assess osteolytic and organ involvement), a complete hematologic panel, coagulation studies, and liver function tests.18,21

Management

Management of LCH varies based on the organ system(s) involved along with the extent of the disease. Dermatology referral may be indicated in patients presenting with nonresolving cutaneous lesions as well as in severe cases. Single-organ and multisystem disease may require one treatment modality or a combination of chemotherapy, surgery, radiation, and/or immunotherapy.21

Infantile Hemangioma

Presentation

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common benign tumor of infancy and usually is apparent a few weeks after birth. Lesions appear as bright red papules, nodules, or plaques. Deep or subcutaneous lesions present as raised, flesh-colored nodules with a blue hue and bruiselike appearance with or without a central patch of telangiectasia22-24 (Figure 6). Although all IHs eventually resolve, residual skin changes such as scarring, atrophy, and fibrosis can persist.24

The incidence of IH has been reported to occur in up to 4% to 5% of infants in the United States.23,25 Infantile hemangiomas also have been found to be more common among white, preterm, and multiple-gestation infants.25 The proposed pathogenesis of IHs includes angiogenic and vasogenic factors that cause rapid proliferation of blood vessels, likely driven by tissue hypoxia.23,26,27

Diagnosis

Infantile hemangioma is diagnosed clinically; however, immunohistochemical staining showing positivity for glucose transporter 1 also is helpful.26,27 Imaging modalities such as ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging also can be utilized to visualize the extent of lesions if necessary.25

Management

Around 15% to 25% of IHs are considered complicated and require intervention.25,27 Infantile hemangiomas can interfere with function depending on location or have potentially fatal complications. Based on the location and extent of involvement, these findings can include ulceration; hemorrhage; impairment of feeding, hearing, and/or vision; facial deformities; airway obstruction; hypothyroidism; and congestive heart failure.25,28 Early treatment with topical or oral beta-blockers is imperative for potentially life-threatening IHs, which can be seen due to large size or dangerous location.28,29 Because the rapid proliferative phase of IHs is thought to begin around 6 weeks of life, treatment should be initiated as early as possible. Initiation of beta-blocker therapy in the first few months of life can prevent functional impairment, ulceration, and permanent cosmetic changes. Additionally, surgery or pulsed dye laser treatment have been found to be effective for skin changes found after involution of IH.25,29

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for IH includes vascular malformations, which are present at birth and do not undergo rapid proliferation; sarcoma; and kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, which causes the Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon secondary to platelet trapping. Careful attention to the history of the skin lesion provides good support for diagnosis of IH in most cases.

IgA Vasculitis

Presentation

IgA vasculitis, or Henoch-Schönlein purpura, classically presents as a tetrad of palpable purpura, acute-onset arthritis or arthralgia, abdominal pain, and renal disease with proteinuria or hematuria.30 Skin involvement is seen in almost all cases and is essential for diagnosis of IgA vasculitis. The initial dermatosis may be pruritic and present as an erythematous macular or urticarial wheal that evolves into petechiae, along with palpable purpura that is most frequently located on the legs or buttocks (Figure 7).30-34

IgA vasculitis is an immune-mediated small vessel vasculitis with deposition of IgA in the small vessels. The underlying cause remains unknown, though infection, dietary allergens, drugs, vaccinations, and chemical triggers have been recognized in literature.32,35,36 IgA vasculitis is largely a pediatric diagnosis, with 90% of affected individuals younger than 10 years worldwide.37 In the pediatric population, the incidence has been reported to be 3 to 26.7 cases per 100,000 children.32

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on the clinical presentation and histopathology.30 On direct immunofluorescence, IgA deposition is seen in the vessel walls.35 Laboratory testing is not diagnostic, but urinalysis is mandatory to identify involvement of renal vasculature. Imaging studies may be used in patients with abdominal symptoms, as an ultrasound can be used to visualize bowel structure and abnormalities such as intussusception.33

Management

The majority of cases of IgA vasculitis recover spontaneously, with patients requiring hospital admission based on severity of symptoms.30 The primary approach to management involves providing supportive care including hydration, adequate rest, and symptomatic pain relief of the joints and abdomen with oral analgesics. Systemic corticosteroids or steroid-sparing agents such as dapsone or colchicine can be used to treat cutaneous manifestations in addition to severe pain symptoms.30,31 Patients with IgA vasculitis must be monitored for proteinuria or hematuria to assess the extent of renal involvement. Although much more common in adults, long-term renal impairment can result from childhood cases of IgA vasculitis.34

Final Thoughts

Pediatric dermatology emergencies can be difficult to detect and accurately diagnose. Many of these diseases are potential emergencies that that may result in delayed treatment and considerable morbidity and mortality if missed. Clinicians should be aware that timely recognition and diagnosis, along with possible referral to pediatric dermatology, are essential to avoid complications.

- Leung AKC, Barankin B, Leong KF. Staphylococcal-scalded skin syndrome: evaluation, diagnosis, and management. World J Pediatr. 2018;14:116-120.

- Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome: diagnosis and management in children and adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1418-1423.

- Davidson J, Polly S, Hayes P, et al. Recurrent staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in an extremely low-birth-weight neonate. AJP Rep. 2017;7:E134-E137.

- Mishra AK, Yadav P, Mishra A. A systemic review on staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS): a rare and critical disease of neonates. Open Microbiol J. 2016;10:150-159.

- Berk D. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Cancer Therapy Advisor website. https://www.cancertherapyadvisor.com/home/decision-support-in-medicine/pediatrics/staphylococcal-scalded-skin-syndrome/. Published 2017. Accessed February 19, 2020.

- Sakr A, Brégeon F, Mège JL, et al. Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization: an update on mechanisms, epidemiology, risk factors, and subsequent infections [published online October 8, 2018]. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2419.

- Pereira LB. Impetigo review. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:293-299.

- Nardi NM, Schaefer TJ. Impetigo. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430974/. Accessed February 21, 2020.

- Koning S, van der Sande R, Verhagen AP, et al. Interventions for impetigo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;1:CD003261.

- Sommer LL, Reboli AC, Heymann WR. Bacterial diseases. In: Bolognia, JL Schaffer, JV Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1259-1295.

- Micali G, Lacarrubba F. Eczema herpeticum. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:e9.

- Leung DY. Why is eczema herpeticum unexpectedly rare? Antiviral Res. 2013;98:153-157.

- Seegräber M, Worm M, Werfel T, et al. Recurrent eczema herpeticum—a retrospective European multicenter study evaluating the clinical characteristics of eczema herpeticum cases in atopic dermatitis patients [published online November 16, 2019]. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.16090.

- Sun D, Ong PY. Infectious complications in atopic dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2017;37:75-93.

- Hsu DY, Shinkai K, Silverberg JI. Epidemiology of eczema herpeticum in hospitalized U.S. children: analysis of a nationwide cohort [published online September 17, 2018]. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:265-272.

- Leung DY, Gao PS, Grigoryev DN, et al. Human atopic dermatitis complicated by eczema herpeticum is associated with abnormalities in IFN-γ response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:965-73.e1-5.

- Darji K, Frisch S, Adjei Boakye E, et al. Characterization of children with recurrent eczema herpeticum and response to treatment with interferon-gamma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:686-689.

- Allen CE, Merad M, McClain KL. Langerhans-cell histiocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:856-868.

- Abla O, Weitzman S. Treatment of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: role of BRAF/MAPK inhibition. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2015;2015:565-570.

- Allen CE, Li L, Peters TL, et al. Cell-specific gene expression in Langerhans cell histiocytosis lesions reveals a distinct profile compared with epidermal Langerhans cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:4557-4567.

- Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work-up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184.

- Holland KE, Drolet BA. Infantile hemangioma [published online August 21, 2010]. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2010;57:1069-1083.

- Chen TS, Eichenfield LF, Friedlander SF. Infantile hemangiomas: an update on pathogenesis and therapy. Pediatrics. 2013;131:99-108.

- George A, Mani V, Noufal A. Update on the classification of hemangioma. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18(suppl 1):S117-S120.

- Darrow DH, Greene AK, Mancini AJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of infantile hemangioma. Pediatrics. 2015;136:786-791.

- Munden A, Butschek R, Tom WL, et al. Prospective study of infantile haemangiomas: incidence, clinical characteristics and association with placental anomalies. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:907-913.

- de Jong S, Itinteang T, Withers AH, et al. Does hypoxia play a role in infantile hemangioma? Arch Dermatol Res. 2016;308:219-227.

- Hogeling M, Adams S, Wargon O. A randomized controlled trial of propranolol for infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2011;128:E259-E266.

- Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas [published online January 2019]. Pediatrics. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-3475.

- Sohagia AB, Gunturu SG, Tong TR, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura—a case report and review of the literature [published online May 23, 2010]. Gastroenterol Res Pract. doi:10.1155/2010/597648.

- Rigante D, Castellazzi L, Bosco A, et al. Is there a crossroad between infections, genetics, and Henoch-Schönlein purpura? Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:1016-1021.

- Piram M, Mahr A. Epidemiology of immunoglobulin A vasculitis (Henoch–Schönlein): current state of knowledge. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013;25:171-178.

- Carlson JA. The histological assessment of cutaneous vasculitis. Histopathology. 2010;56:3-23.

- Eleftheriou D, Batu ED, Ozen S, et al. Vasculitis in children. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;30:I94-I103.

- van Timmeren MM, Heeringa P, Kallenberg CG. Infectious triggers for vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26:416-423.

- Scott DGI, Watts RA. Epidemiology and clinical features of systemic vasculitis [published online July 11, 2013]. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2013;17:607-610.

- He X, Yu C, Zhao P, et al. The genetics of Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:1387-1395.

- Leung AKC, Barankin B, Leong KF. Staphylococcal-scalded skin syndrome: evaluation, diagnosis, and management. World J Pediatr. 2018;14:116-120.

- Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome: diagnosis and management in children and adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1418-1423.

- Davidson J, Polly S, Hayes P, et al. Recurrent staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in an extremely low-birth-weight neonate. AJP Rep. 2017;7:E134-E137.

- Mishra AK, Yadav P, Mishra A. A systemic review on staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS): a rare and critical disease of neonates. Open Microbiol J. 2016;10:150-159.

- Berk D. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Cancer Therapy Advisor website. https://www.cancertherapyadvisor.com/home/decision-support-in-medicine/pediatrics/staphylococcal-scalded-skin-syndrome/. Published 2017. Accessed February 19, 2020.

- Sakr A, Brégeon F, Mège JL, et al. Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization: an update on mechanisms, epidemiology, risk factors, and subsequent infections [published online October 8, 2018]. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2419.

- Pereira LB. Impetigo review. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:293-299.

- Nardi NM, Schaefer TJ. Impetigo. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430974/. Accessed February 21, 2020.

- Koning S, van der Sande R, Verhagen AP, et al. Interventions for impetigo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;1:CD003261.

- Sommer LL, Reboli AC, Heymann WR. Bacterial diseases. In: Bolognia, JL Schaffer, JV Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1259-1295.

- Micali G, Lacarrubba F. Eczema herpeticum. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:e9.

- Leung DY. Why is eczema herpeticum unexpectedly rare? Antiviral Res. 2013;98:153-157.

- Seegräber M, Worm M, Werfel T, et al. Recurrent eczema herpeticum—a retrospective European multicenter study evaluating the clinical characteristics of eczema herpeticum cases in atopic dermatitis patients [published online November 16, 2019]. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.16090.

- Sun D, Ong PY. Infectious complications in atopic dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2017;37:75-93.

- Hsu DY, Shinkai K, Silverberg JI. Epidemiology of eczema herpeticum in hospitalized U.S. children: analysis of a nationwide cohort [published online September 17, 2018]. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:265-272.

- Leung DY, Gao PS, Grigoryev DN, et al. Human atopic dermatitis complicated by eczema herpeticum is associated with abnormalities in IFN-γ response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:965-73.e1-5.

- Darji K, Frisch S, Adjei Boakye E, et al. Characterization of children with recurrent eczema herpeticum and response to treatment with interferon-gamma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:686-689.

- Allen CE, Merad M, McClain KL. Langerhans-cell histiocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:856-868.

- Abla O, Weitzman S. Treatment of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: role of BRAF/MAPK inhibition. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2015;2015:565-570.

- Allen CE, Li L, Peters TL, et al. Cell-specific gene expression in Langerhans cell histiocytosis lesions reveals a distinct profile compared with epidermal Langerhans cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:4557-4567.

- Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work-up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184.

- Holland KE, Drolet BA. Infantile hemangioma [published online August 21, 2010]. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2010;57:1069-1083.

- Chen TS, Eichenfield LF, Friedlander SF. Infantile hemangiomas: an update on pathogenesis and therapy. Pediatrics. 2013;131:99-108.

- George A, Mani V, Noufal A. Update on the classification of hemangioma. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18(suppl 1):S117-S120.

- Darrow DH, Greene AK, Mancini AJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of infantile hemangioma. Pediatrics. 2015;136:786-791.

- Munden A, Butschek R, Tom WL, et al. Prospective study of infantile haemangiomas: incidence, clinical characteristics and association with placental anomalies. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:907-913.

- de Jong S, Itinteang T, Withers AH, et al. Does hypoxia play a role in infantile hemangioma? Arch Dermatol Res. 2016;308:219-227.

- Hogeling M, Adams S, Wargon O. A randomized controlled trial of propranolol for infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2011;128:E259-E266.

- Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas [published online January 2019]. Pediatrics. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-3475.

- Sohagia AB, Gunturu SG, Tong TR, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura—a case report and review of the literature [published online May 23, 2010]. Gastroenterol Res Pract. doi:10.1155/2010/597648.

- Rigante D, Castellazzi L, Bosco A, et al. Is there a crossroad between infections, genetics, and Henoch-Schönlein purpura? Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:1016-1021.

- Piram M, Mahr A. Epidemiology of immunoglobulin A vasculitis (Henoch–Schönlein): current state of knowledge. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013;25:171-178.

- Carlson JA. The histological assessment of cutaneous vasculitis. Histopathology. 2010;56:3-23.

- Eleftheriou D, Batu ED, Ozen S, et al. Vasculitis in children. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;30:I94-I103.

- van Timmeren MM, Heeringa P, Kallenberg CG. Infectious triggers for vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26:416-423.

- Scott DGI, Watts RA. Epidemiology and clinical features of systemic vasculitis [published online July 11, 2013]. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2013;17:607-610.

- He X, Yu C, Zhao P, et al. The genetics of Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:1387-1395.

Practice Points

- Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, impetigo, eczema herpeticum, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, infantile hemangiomas, and IgA vasculitis all present potential emergencies in pediatric patients in dermatologic settings.

- Early and accurate identification and management of these entities is critical to avoid short-term and long-term negative sequalae.