User login

Intraoperative Tissue Expansion to Allow Primary Linear Closure of 2 Large Adjacent Surgical Defects

Practice Gap

Nonmelanoma skin cancers most commonly are found on the head and neck. In these locations, many of these malignancies will meet criteria to undergo treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. It is becoming increasingly common for patients to have multiple lesions treated at the same time, and sometimes these lesions can be in close proximity to one another. The final size of the adjacent defects, along with the amount of normal tissue remaining between them, will determine how to best repair both defects.1 Many times, repair options are limited to the use of a larger and more extensive repair such as a flap or graft. We present a novel option to increase the options for surgical repair.

The Technique

We present a case of 2 large adjacent postsurgical defects where intraoperative tissue relaxation allowed for successful primary linear closure of both defects under notably decreased tension from baseline. A 70-year-old man presented for treatment of 2 adjacent invasive squamous cell carcinomas on the left temple and left frontal scalp. The initial lesion sizes were 2.0×1.0 and 2.0×2.0 cm, respectively. Mohs micrographic surgery was performed on both lesions, and the final defect sizes measured 2.0×1.4 and 3.0×1.6 cm, respectively. The island of normal tissue between the defects measured 2.3-cm wide. Different repair options were discussed with the patient, including allowing 1 or both lesions to heal via secondary intention, creating 1 large wound to repair with a full-thickness skin graft, using a large skin flap to cover both wounds, or utilizing a 2-to-Z flap.2 We also discussed using an intraoperative skin relaxation device to stretch the skin around 1 or both defects and close both defects in a linear fashion; the patient opted for the latter treatment option.

The left temple had adequate mobility to perform a primary closure oriented horizontally along the long axis of the defect. Although it would have been a simple repair for this lesion, the superior defect on the frontal scalp would have been subjected to increased downward tension. The scalp defect was already under considerable tension with limited tissue mobility, so closing the temple defect horizontally would have required repair of the scalp defect using a skin graft or leaving it open to heal on its own. Similarly, the force necessary to close the frontal scalp wound first would have prevented primary closure of the temple defect.

A SUTUREGARD ISR device (Sutureguard Medical Inc) was secured centrally over both defects at a 90° angle to one another to provide intraoperative tissue relaxation without undermining. The devices were held in place by a US Pharmacopeia 2-0 nylon suture and allowed to sit for 60 minutes (Figure 1).3

After 60 minutes, the temple defect had adequate relaxion to allow a standard layered intermediate closure in a vertical orientation along the hairline using 3-0 polyglactin 910 and 3-0 nylon. Although the scalp defect was not completely approximated, it was more than 60% smaller and able to be closed at both wound edges using the same layered approach. There was a central defect area approximately 4-mm wide that was left to heal by secondary intention (Figure 2). Undermining was not used to close either defect.

The patient tolerated the procedure well with minimal pain or discomfort. He followed standard postoperative care instructions and returned for suture removal after 14 days of healing. At the time of suture removal there were no complications. At 1-month follow-up the patient presented with excellent cosmetic results (Figure 3).

Practice Implications

The methods of repairing 2 adjacent postsurgical defects are numerous and vary depending on the size of the individual defects, the location of the defects, and the amount of normal skin remaining between them. Various methods of closure for the adjacent defects include healing by secondary intention, primary linear closure, skin grafts, skin flaps, creating 1 larger wound to be repaired, or a combination of these approaches.1,2,4,5

In our patient, closing the high-tension wound of the scalp would have prevented both wounds from being closed in a linear fashion without first stretching the tissue. Although Zitelli5 has cited that many wounds will heal well on their own despite a large size, many patients prefer the cosmetic appearance and shorter healing time of wounds that have been closed with sutures, particularly if those defects are greater than 8-mm wide. In contrast, patients preferred the cosmetic appearance of 4-mm wounds that healed via secondary intention.6 In our case, we closed the majority of the wound and left a small 4-mm-wide portion to heal on its own. The overall outcome was excellent and healed much quicker than leaving the entire scalp defect to heal by secondary intention.

The other methods of closure, such as a 2-to-Z flap, would have been difficult given the orientation of the lesions and the island between them.2 To create this flap, an extensive amount of undermining would have been necessary, leading to serious disruption of the blood and nerve supply and an increased risk for flap necrosis. Creating 1 large wound and repairing with a flap would have similar requirements and complications.

Intraoperative tissue relaxation can be used to allow primary closure of adjacent wounds without the need for undermining. Prior research has shown that 30 minutes of stress relaxation with 20 Newtons of applied tension yields a 65% reduction in wound-closure tension.7 Orienting the devices between 45° to 90° angles to one another creates opposing tension vectors so that the closure of one defect does not prevent the closure of the other defect. Even in cases in which the defects cannot be completely approximated, closing the wound edges to create a smaller central defect can decrease healing time and lead to an excellent cosmetic outcome without the need for a flap or graft.

The SUTUREGARD ISR suture retention bridge also is cost-effective for the surgeon and the patient. The device and suture-guide washer are included in a set that retails for $35 each or $300 for a box of 12.8 The suture most commonly used to secure the device in our practice is 2-0 nylon and retails for approximately $34 for a box of 12,9 which brings the total cost with the device to around $38 per use. The updated Current Procedural Terminology guidelines from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services define that an intermediate repair requires a layered closure and may include, but does not require, limited undermining. A complex linear closure must meet criteria for an intermediate closure plus at least 1 additional criterion, such as exposure of cartilage, bone, or tendons within the defect; extensive undermining; wound-edge debridement; involvement of free margins; or use of a retention suture.10 Use of a suture retention bridge such as the SUTUREGARD ISR device and therefore a retention suture qualifies the repair as a complex linear closure. Overall, use of the device expands the surgeon’s choices for surgical closures and helps to limit the need for larger, more invasive repair procedures.

- McGinness JL, Parlette HL. A novel technique using a rotation flap for repairing adjacent surgical defects. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:272-275.

- Blattner CM, Perry B, Young J, et al. 2-to-Z flap for reconstruction of adjacent skin defects. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:E77-E78.

- Blattner CM, Perry B, Young J, et al. The use of a suture retention device to enhance tissue expansion and healing in the repair of scalp and lower leg wounds. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:655-661.

- Zivony D, Siegle RJ. Burrow’s wedge advancement flaps for reconstruction of adjacent surgical defects. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:1162-1164.

- Zitelli JA. Secondary intention healing: an alternative to surgical repair. Clin Dermatol. 1984;2:92-106.

- Christenson LJ, Phillips PK, Weaver AL, et al. Primary closure vs second-intention treatment of skin punch biopsy sites: a randomized trial. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1093-1099.

- Lear W, Blattner CM, Mustoe TA, et al. In vivo stress relaxation of human scalp. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2019;97:85-89.

- SUTUREGARD purchasing facts. SUTUREGARD® Medical Inc website. https://suturegard.com/SUTUREGARD-Purchasing-Facts. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Shop products: suture with needle McKesson nonabsorbable uncoated black suture monofilament nylon size 2-0 18 inch suture 1-needle 26 mm length 3/8 circle reverse cutting needle. McKesson website. https://mms.mckesson.com/catalog?query=1034509. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Norris S. 2020 CPT updates to wound repair guidelines. Zotec Partners website. http://zotecpartners.com/resources/2020-cpt-updates-to-wound-repair-guidelines/. Published June 4, 2020. Accessed October 21, 2020.

Practice Gap

Nonmelanoma skin cancers most commonly are found on the head and neck. In these locations, many of these malignancies will meet criteria to undergo treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. It is becoming increasingly common for patients to have multiple lesions treated at the same time, and sometimes these lesions can be in close proximity to one another. The final size of the adjacent defects, along with the amount of normal tissue remaining between them, will determine how to best repair both defects.1 Many times, repair options are limited to the use of a larger and more extensive repair such as a flap or graft. We present a novel option to increase the options for surgical repair.

The Technique

We present a case of 2 large adjacent postsurgical defects where intraoperative tissue relaxation allowed for successful primary linear closure of both defects under notably decreased tension from baseline. A 70-year-old man presented for treatment of 2 adjacent invasive squamous cell carcinomas on the left temple and left frontal scalp. The initial lesion sizes were 2.0×1.0 and 2.0×2.0 cm, respectively. Mohs micrographic surgery was performed on both lesions, and the final defect sizes measured 2.0×1.4 and 3.0×1.6 cm, respectively. The island of normal tissue between the defects measured 2.3-cm wide. Different repair options were discussed with the patient, including allowing 1 or both lesions to heal via secondary intention, creating 1 large wound to repair with a full-thickness skin graft, using a large skin flap to cover both wounds, or utilizing a 2-to-Z flap.2 We also discussed using an intraoperative skin relaxation device to stretch the skin around 1 or both defects and close both defects in a linear fashion; the patient opted for the latter treatment option.

The left temple had adequate mobility to perform a primary closure oriented horizontally along the long axis of the defect. Although it would have been a simple repair for this lesion, the superior defect on the frontal scalp would have been subjected to increased downward tension. The scalp defect was already under considerable tension with limited tissue mobility, so closing the temple defect horizontally would have required repair of the scalp defect using a skin graft or leaving it open to heal on its own. Similarly, the force necessary to close the frontal scalp wound first would have prevented primary closure of the temple defect.

A SUTUREGARD ISR device (Sutureguard Medical Inc) was secured centrally over both defects at a 90° angle to one another to provide intraoperative tissue relaxation without undermining. The devices were held in place by a US Pharmacopeia 2-0 nylon suture and allowed to sit for 60 minutes (Figure 1).3

After 60 minutes, the temple defect had adequate relaxion to allow a standard layered intermediate closure in a vertical orientation along the hairline using 3-0 polyglactin 910 and 3-0 nylon. Although the scalp defect was not completely approximated, it was more than 60% smaller and able to be closed at both wound edges using the same layered approach. There was a central defect area approximately 4-mm wide that was left to heal by secondary intention (Figure 2). Undermining was not used to close either defect.

The patient tolerated the procedure well with minimal pain or discomfort. He followed standard postoperative care instructions and returned for suture removal after 14 days of healing. At the time of suture removal there were no complications. At 1-month follow-up the patient presented with excellent cosmetic results (Figure 3).

Practice Implications

The methods of repairing 2 adjacent postsurgical defects are numerous and vary depending on the size of the individual defects, the location of the defects, and the amount of normal skin remaining between them. Various methods of closure for the adjacent defects include healing by secondary intention, primary linear closure, skin grafts, skin flaps, creating 1 larger wound to be repaired, or a combination of these approaches.1,2,4,5

In our patient, closing the high-tension wound of the scalp would have prevented both wounds from being closed in a linear fashion without first stretching the tissue. Although Zitelli5 has cited that many wounds will heal well on their own despite a large size, many patients prefer the cosmetic appearance and shorter healing time of wounds that have been closed with sutures, particularly if those defects are greater than 8-mm wide. In contrast, patients preferred the cosmetic appearance of 4-mm wounds that healed via secondary intention.6 In our case, we closed the majority of the wound and left a small 4-mm-wide portion to heal on its own. The overall outcome was excellent and healed much quicker than leaving the entire scalp defect to heal by secondary intention.

The other methods of closure, such as a 2-to-Z flap, would have been difficult given the orientation of the lesions and the island between them.2 To create this flap, an extensive amount of undermining would have been necessary, leading to serious disruption of the blood and nerve supply and an increased risk for flap necrosis. Creating 1 large wound and repairing with a flap would have similar requirements and complications.

Intraoperative tissue relaxation can be used to allow primary closure of adjacent wounds without the need for undermining. Prior research has shown that 30 minutes of stress relaxation with 20 Newtons of applied tension yields a 65% reduction in wound-closure tension.7 Orienting the devices between 45° to 90° angles to one another creates opposing tension vectors so that the closure of one defect does not prevent the closure of the other defect. Even in cases in which the defects cannot be completely approximated, closing the wound edges to create a smaller central defect can decrease healing time and lead to an excellent cosmetic outcome without the need for a flap or graft.

The SUTUREGARD ISR suture retention bridge also is cost-effective for the surgeon and the patient. The device and suture-guide washer are included in a set that retails for $35 each or $300 for a box of 12.8 The suture most commonly used to secure the device in our practice is 2-0 nylon and retails for approximately $34 for a box of 12,9 which brings the total cost with the device to around $38 per use. The updated Current Procedural Terminology guidelines from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services define that an intermediate repair requires a layered closure and may include, but does not require, limited undermining. A complex linear closure must meet criteria for an intermediate closure plus at least 1 additional criterion, such as exposure of cartilage, bone, or tendons within the defect; extensive undermining; wound-edge debridement; involvement of free margins; or use of a retention suture.10 Use of a suture retention bridge such as the SUTUREGARD ISR device and therefore a retention suture qualifies the repair as a complex linear closure. Overall, use of the device expands the surgeon’s choices for surgical closures and helps to limit the need for larger, more invasive repair procedures.

Practice Gap

Nonmelanoma skin cancers most commonly are found on the head and neck. In these locations, many of these malignancies will meet criteria to undergo treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. It is becoming increasingly common for patients to have multiple lesions treated at the same time, and sometimes these lesions can be in close proximity to one another. The final size of the adjacent defects, along with the amount of normal tissue remaining between them, will determine how to best repair both defects.1 Many times, repair options are limited to the use of a larger and more extensive repair such as a flap or graft. We present a novel option to increase the options for surgical repair.

The Technique

We present a case of 2 large adjacent postsurgical defects where intraoperative tissue relaxation allowed for successful primary linear closure of both defects under notably decreased tension from baseline. A 70-year-old man presented for treatment of 2 adjacent invasive squamous cell carcinomas on the left temple and left frontal scalp. The initial lesion sizes were 2.0×1.0 and 2.0×2.0 cm, respectively. Mohs micrographic surgery was performed on both lesions, and the final defect sizes measured 2.0×1.4 and 3.0×1.6 cm, respectively. The island of normal tissue between the defects measured 2.3-cm wide. Different repair options were discussed with the patient, including allowing 1 or both lesions to heal via secondary intention, creating 1 large wound to repair with a full-thickness skin graft, using a large skin flap to cover both wounds, or utilizing a 2-to-Z flap.2 We also discussed using an intraoperative skin relaxation device to stretch the skin around 1 or both defects and close both defects in a linear fashion; the patient opted for the latter treatment option.

The left temple had adequate mobility to perform a primary closure oriented horizontally along the long axis of the defect. Although it would have been a simple repair for this lesion, the superior defect on the frontal scalp would have been subjected to increased downward tension. The scalp defect was already under considerable tension with limited tissue mobility, so closing the temple defect horizontally would have required repair of the scalp defect using a skin graft or leaving it open to heal on its own. Similarly, the force necessary to close the frontal scalp wound first would have prevented primary closure of the temple defect.

A SUTUREGARD ISR device (Sutureguard Medical Inc) was secured centrally over both defects at a 90° angle to one another to provide intraoperative tissue relaxation without undermining. The devices were held in place by a US Pharmacopeia 2-0 nylon suture and allowed to sit for 60 minutes (Figure 1).3

After 60 minutes, the temple defect had adequate relaxion to allow a standard layered intermediate closure in a vertical orientation along the hairline using 3-0 polyglactin 910 and 3-0 nylon. Although the scalp defect was not completely approximated, it was more than 60% smaller and able to be closed at both wound edges using the same layered approach. There was a central defect area approximately 4-mm wide that was left to heal by secondary intention (Figure 2). Undermining was not used to close either defect.

The patient tolerated the procedure well with minimal pain or discomfort. He followed standard postoperative care instructions and returned for suture removal after 14 days of healing. At the time of suture removal there were no complications. At 1-month follow-up the patient presented with excellent cosmetic results (Figure 3).

Practice Implications

The methods of repairing 2 adjacent postsurgical defects are numerous and vary depending on the size of the individual defects, the location of the defects, and the amount of normal skin remaining between them. Various methods of closure for the adjacent defects include healing by secondary intention, primary linear closure, skin grafts, skin flaps, creating 1 larger wound to be repaired, or a combination of these approaches.1,2,4,5

In our patient, closing the high-tension wound of the scalp would have prevented both wounds from being closed in a linear fashion without first stretching the tissue. Although Zitelli5 has cited that many wounds will heal well on their own despite a large size, many patients prefer the cosmetic appearance and shorter healing time of wounds that have been closed with sutures, particularly if those defects are greater than 8-mm wide. In contrast, patients preferred the cosmetic appearance of 4-mm wounds that healed via secondary intention.6 In our case, we closed the majority of the wound and left a small 4-mm-wide portion to heal on its own. The overall outcome was excellent and healed much quicker than leaving the entire scalp defect to heal by secondary intention.

The other methods of closure, such as a 2-to-Z flap, would have been difficult given the orientation of the lesions and the island between them.2 To create this flap, an extensive amount of undermining would have been necessary, leading to serious disruption of the blood and nerve supply and an increased risk for flap necrosis. Creating 1 large wound and repairing with a flap would have similar requirements and complications.

Intraoperative tissue relaxation can be used to allow primary closure of adjacent wounds without the need for undermining. Prior research has shown that 30 minutes of stress relaxation with 20 Newtons of applied tension yields a 65% reduction in wound-closure tension.7 Orienting the devices between 45° to 90° angles to one another creates opposing tension vectors so that the closure of one defect does not prevent the closure of the other defect. Even in cases in which the defects cannot be completely approximated, closing the wound edges to create a smaller central defect can decrease healing time and lead to an excellent cosmetic outcome without the need for a flap or graft.

The SUTUREGARD ISR suture retention bridge also is cost-effective for the surgeon and the patient. The device and suture-guide washer are included in a set that retails for $35 each or $300 for a box of 12.8 The suture most commonly used to secure the device in our practice is 2-0 nylon and retails for approximately $34 for a box of 12,9 which brings the total cost with the device to around $38 per use. The updated Current Procedural Terminology guidelines from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services define that an intermediate repair requires a layered closure and may include, but does not require, limited undermining. A complex linear closure must meet criteria for an intermediate closure plus at least 1 additional criterion, such as exposure of cartilage, bone, or tendons within the defect; extensive undermining; wound-edge debridement; involvement of free margins; or use of a retention suture.10 Use of a suture retention bridge such as the SUTUREGARD ISR device and therefore a retention suture qualifies the repair as a complex linear closure. Overall, use of the device expands the surgeon’s choices for surgical closures and helps to limit the need for larger, more invasive repair procedures.

- McGinness JL, Parlette HL. A novel technique using a rotation flap for repairing adjacent surgical defects. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:272-275.

- Blattner CM, Perry B, Young J, et al. 2-to-Z flap for reconstruction of adjacent skin defects. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:E77-E78.

- Blattner CM, Perry B, Young J, et al. The use of a suture retention device to enhance tissue expansion and healing in the repair of scalp and lower leg wounds. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:655-661.

- Zivony D, Siegle RJ. Burrow’s wedge advancement flaps for reconstruction of adjacent surgical defects. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:1162-1164.

- Zitelli JA. Secondary intention healing: an alternative to surgical repair. Clin Dermatol. 1984;2:92-106.

- Christenson LJ, Phillips PK, Weaver AL, et al. Primary closure vs second-intention treatment of skin punch biopsy sites: a randomized trial. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1093-1099.

- Lear W, Blattner CM, Mustoe TA, et al. In vivo stress relaxation of human scalp. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2019;97:85-89.

- SUTUREGARD purchasing facts. SUTUREGARD® Medical Inc website. https://suturegard.com/SUTUREGARD-Purchasing-Facts. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Shop products: suture with needle McKesson nonabsorbable uncoated black suture monofilament nylon size 2-0 18 inch suture 1-needle 26 mm length 3/8 circle reverse cutting needle. McKesson website. https://mms.mckesson.com/catalog?query=1034509. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Norris S. 2020 CPT updates to wound repair guidelines. Zotec Partners website. http://zotecpartners.com/resources/2020-cpt-updates-to-wound-repair-guidelines/. Published June 4, 2020. Accessed October 21, 2020.

- McGinness JL, Parlette HL. A novel technique using a rotation flap for repairing adjacent surgical defects. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:272-275.

- Blattner CM, Perry B, Young J, et al. 2-to-Z flap for reconstruction of adjacent skin defects. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:E77-E78.

- Blattner CM, Perry B, Young J, et al. The use of a suture retention device to enhance tissue expansion and healing in the repair of scalp and lower leg wounds. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:655-661.

- Zivony D, Siegle RJ. Burrow’s wedge advancement flaps for reconstruction of adjacent surgical defects. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:1162-1164.

- Zitelli JA. Secondary intention healing: an alternative to surgical repair. Clin Dermatol. 1984;2:92-106.

- Christenson LJ, Phillips PK, Weaver AL, et al. Primary closure vs second-intention treatment of skin punch biopsy sites: a randomized trial. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1093-1099.

- Lear W, Blattner CM, Mustoe TA, et al. In vivo stress relaxation of human scalp. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2019;97:85-89.

- SUTUREGARD purchasing facts. SUTUREGARD® Medical Inc website. https://suturegard.com/SUTUREGARD-Purchasing-Facts. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Shop products: suture with needle McKesson nonabsorbable uncoated black suture monofilament nylon size 2-0 18 inch suture 1-needle 26 mm length 3/8 circle reverse cutting needle. McKesson website. https://mms.mckesson.com/catalog?query=1034509. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Norris S. 2020 CPT updates to wound repair guidelines. Zotec Partners website. http://zotecpartners.com/resources/2020-cpt-updates-to-wound-repair-guidelines/. Published June 4, 2020. Accessed October 21, 2020.

Trichodysplasia Spinulosa in the Setting of Colon Cancer

Case Report

An 82-year-old woman presented to the clinic with a rash on the face that had been present for a few months. She denied any treatment or prior occurrence. Her medical history was remarkable for non-Hodgkin lymphoma that had been successfully treated with chemotherapy 4 years prior. Additionally, she recently had been diagnosed with stage IV colon cancer. She reported that surgery had been scheduled and she would start adjuvant chemotherapy soon after.

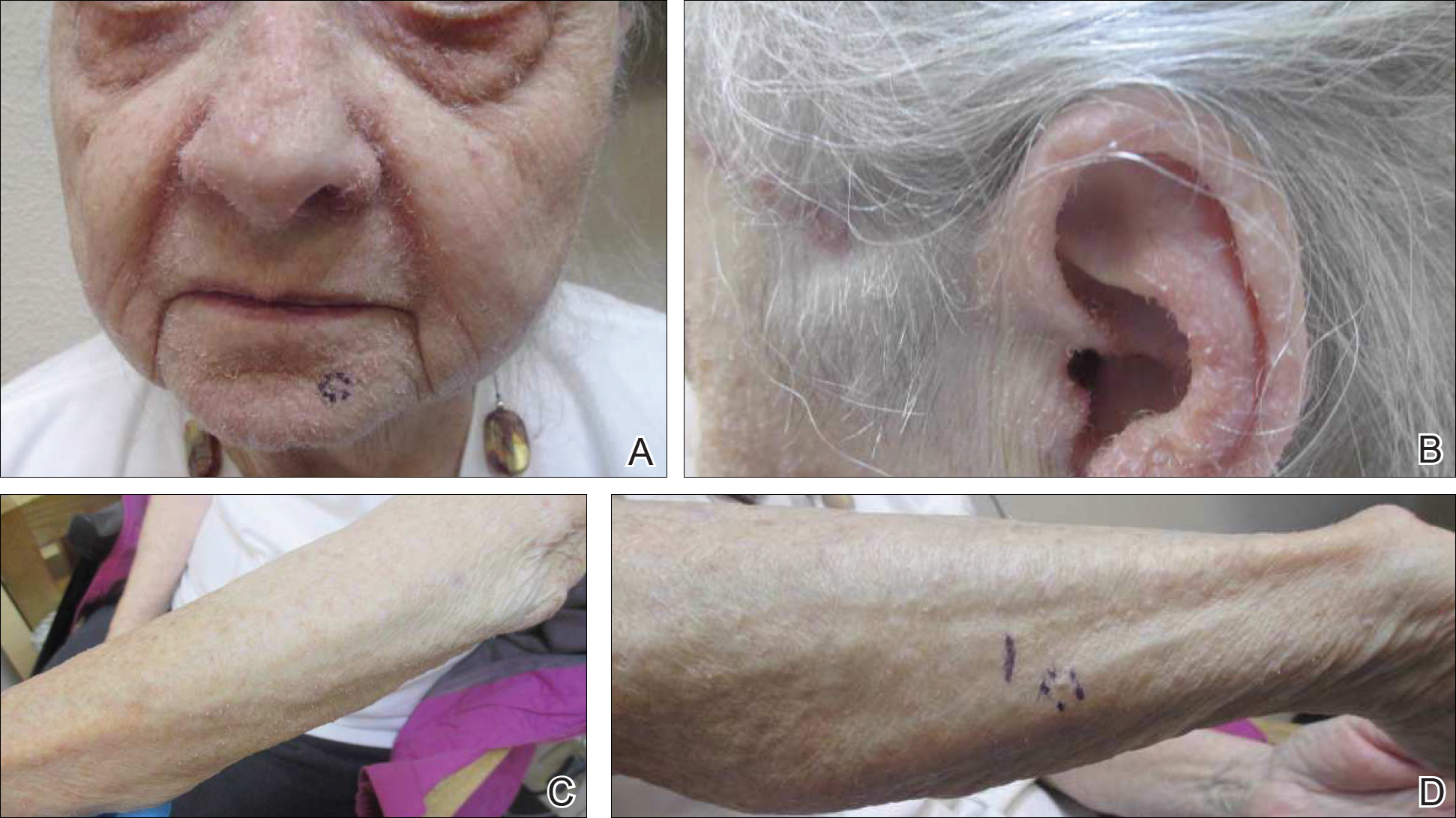

On physical examination she exhibited perioral and perinasal erythematous papules with sparing of the vermilion border. A diagnosis of perioral dermatitis was made, and she was started on topical metronidazole. At 1-month follow-up, her condition had slightly worsened and she was subsequently started on doxycycline. When she returned to the clinic again the following month, physical examination revealed agminated folliculocentric papules with central spicules on the face, nose, ears, upper extremities (Figure 1), and trunk. The differential diagnosis included multiple minute digitate hyperkeratosis, spiculosis of multiple myeloma, and trichodysplasia spinulosa (TS).

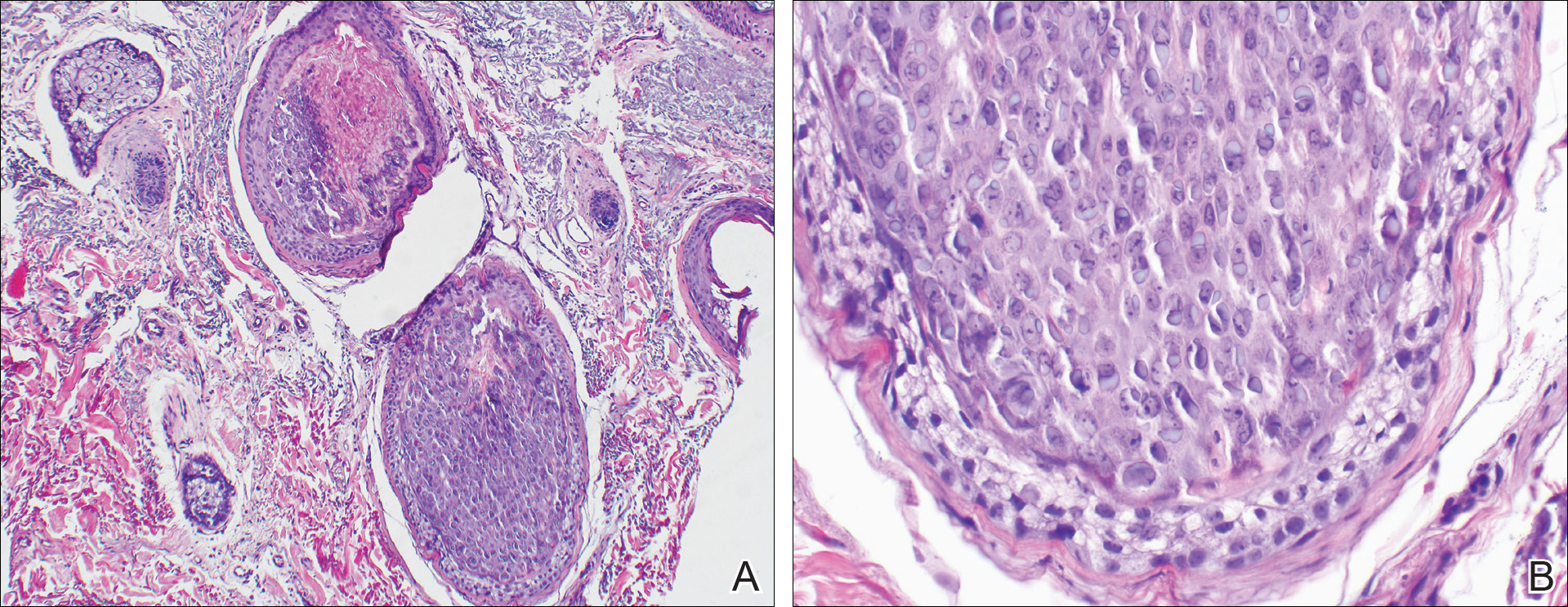

A punch biopsy of 2 separate papules on the face and upper extremity revealed dilated follicles with enlarged trichohyalin granules and dyskeratosis (Figure 2), consistent with TS. Additional testing such as electron microscopy or polymerase chain reaction was not performed to keep the patient’s medical costs down; also, the strong clinical and histopathologic evidence did not warrant further testing.

The plan was to start split-face treatment with topical acyclovir and a topical retinoid to see which agent was more effective, but the patient declined until her chemotherapy regimen had concluded. Unfortunately, the patient died 3 months later due to colon cancer.

Comment

History and Presentation

Trichodysplasia spinulosa was first recognized as hairlike hyperkeratosis.1 The name by which it is currently known was later championed by Haycox et al.2 They reported a case of a 44-year-old man who underwent a combined renal-pancreas transplant and while taking immunosuppressive medication developed erythematous papules with follicular spinous processes and progressive alopecia.2 Other synonymous terms used for this condition include pilomatrix dysplasia, cyclosporine-induced folliculodystrophy, virus-associated trichodysplasia,3 and follicular dystrophy of immunosuppression.4 Trichodysplasia spinulosa can affect both adult and pediatric immunocompromised patients, including organ transplant recipients on immunosuppressants and cancer patients on chemotherapy.3 The condition also has been reported to precede the recurrence of lymphoma.5

Etiology

The connection of TS with a viral etiology was first demonstrated in 1999, and subsequently it was confirmed to be a polyomavirus.2 The family name of Polyomaviridae possesses a Greek derivation with poly- meaning many and -oma meaning cancer.3 This name was given after the polyomavirus induced multiple tumors in mice.3,6 This viral family consists of multiple naked viruses with a surrounding icosahedral capsid containing 3 structural proteins known as VP1, VP2, and VP3. Their life cycle is characterized by early and late phases with respective early and late protein formation.3

Polyomavirus infections maintain an asymptomatic and latent course in immunocompetent patients.7 The prevalence and manifestation of these viruses change when the host’s immune system is altered. The first identified JC virus and BK virus of the same family have been found at increased frequencies in blood and lymphoid tissue during host immunosuppression.6 Moreover, the Merkel cell polyomavirus detected in Merkel cell carcinoma is well documented in the dermatologic literature.6,8

A specific polyomavirus has been implicated in the majority of TS cases and has subsequently received the name of TS polyomavirus.9 As a polyomavirus, it similarly produces capsid antigens and large/small T antigens. Among the viral protein antigens produced, the large tumor or LT antigen represents one of the most potent viral proteins. It has been postulated to inhibit the retinoblastoma family of proteins, leading to increased inner root sheath cells that allow for further viral replication.9,10

The disease presents with folliculocentric papules localized mainly on the central face and ears, which grow central keratin spines or spicules that can become 1 to 3 mm in length. Coinciding alopecia and madarosis also may be present.9

Diagnosis

Histologic examination reveals abnormal follicular maturation and distension. Additionally, increased proliferation and amount of trichohyalin is seen within the inner root sheath cells. Further testing via viral culture, polymerase chain reaction, electron microscopy, or immunohistochemical stains can confirm the diagnosis. Such testing may not be warranted in all cases given that classic clinical findings coupled with routine histopathology staining can provide enough evidence.10,11

Management

Currently, a universal successful treatment for TS does not exist. There have been anecdotal successes reported with topical medications such as cidofovir ointment 1%, acyclovir combined with 2-deoxy-D-glucose and epigallocatechin, corticosteroids, topical tacrolimus, topical retinoids, and imiquimod. Additionally, success has been seen with oral minocycline, oral retinoids, valacyclovir, and valganciclovir, with the latter showing the best results. Patients also have shown improvement after modifying their immunosuppressive treatment regimen.10,12

Conclusion

Given the previously published case of TS preceding the recurrence of lymphoma,5 we notified our patient’s oncologist of this potential risk. Her history of lymphoma and immunosuppressive treatment 4 years prior may represent the etiology of the cutaneous presentation; however, the TS with concurrent colon cancer presented prior to starting immunosuppressive therapy, suggesting that it also may have been a paraneoplastic process and not just a sign of immunosuppression. Therefore, we recommend that patients who present with TS should be evaluated for underlying malignancy if not already diagnosed.

- Linke M, Geraud C, Sauer C, et al. Follicular erythematous papules with keratotic spicules. Acta Derm Venereol . 2014;94:493-494.

- Haycox CL, Kim S, Fleckman P, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa—a newly described folliculocentric viral infection in an immunocompromised host. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:268-271.

- Moens U, Ludvigsen M, Van Ghelue M. Human polyomaviruses in skin diseases [published online September 12, 2011]. Patholog Res Int. 2011;2011:123491.

- Matthews MR, Wang RC, Reddick RL, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia spinulosa: a case with electron microscopic and molecular detection of the trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated human polyomavirus. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:420-431.

- Osswald SS, Kulick KB, Tomaszewski MM, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia in a patient with lymphoma: a case report and review. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:721-725.

- Dalianis T, Hirsch HH. Human polyomavirus in disease and cancer. Virology. 2013;437:63-72.

- Tsuzuki S, Fukumoto H, Mine S, et al. Detection of trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated polyomavirus in a fatal case of myocarditis in a seven-month-old girl. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:5308-5312.

- Sadeghi M, Aronen M, Chen T, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus and trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated polyomavirus DNAs and antibodies in blood among the elderly. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:383.

- Van der Meijden E, Kazem S, Burgers MM, et al. Seroprevalence of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1355-1363.

- Krichhof MG, Shojania K, Hull MW, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: rare presentation of polyomavirus infection in immunocompromised patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18:430-435.

- Rianthavorn P, Posuwan N, Payungporn S, et al. Polyomavirus reactivation in pediatric patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2012;228:197-204.

- Wanat KA, Holler PD, Dentchev T, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia: characterization of a novel polyomavirus infection with therapeutic insights. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:219-223.

Case Report

An 82-year-old woman presented to the clinic with a rash on the face that had been present for a few months. She denied any treatment or prior occurrence. Her medical history was remarkable for non-Hodgkin lymphoma that had been successfully treated with chemotherapy 4 years prior. Additionally, she recently had been diagnosed with stage IV colon cancer. She reported that surgery had been scheduled and she would start adjuvant chemotherapy soon after.

On physical examination she exhibited perioral and perinasal erythematous papules with sparing of the vermilion border. A diagnosis of perioral dermatitis was made, and she was started on topical metronidazole. At 1-month follow-up, her condition had slightly worsened and she was subsequently started on doxycycline. When she returned to the clinic again the following month, physical examination revealed agminated folliculocentric papules with central spicules on the face, nose, ears, upper extremities (Figure 1), and trunk. The differential diagnosis included multiple minute digitate hyperkeratosis, spiculosis of multiple myeloma, and trichodysplasia spinulosa (TS).

A punch biopsy of 2 separate papules on the face and upper extremity revealed dilated follicles with enlarged trichohyalin granules and dyskeratosis (Figure 2), consistent with TS. Additional testing such as electron microscopy or polymerase chain reaction was not performed to keep the patient’s medical costs down; also, the strong clinical and histopathologic evidence did not warrant further testing.

The plan was to start split-face treatment with topical acyclovir and a topical retinoid to see which agent was more effective, but the patient declined until her chemotherapy regimen had concluded. Unfortunately, the patient died 3 months later due to colon cancer.

Comment

History and Presentation

Trichodysplasia spinulosa was first recognized as hairlike hyperkeratosis.1 The name by which it is currently known was later championed by Haycox et al.2 They reported a case of a 44-year-old man who underwent a combined renal-pancreas transplant and while taking immunosuppressive medication developed erythematous papules with follicular spinous processes and progressive alopecia.2 Other synonymous terms used for this condition include pilomatrix dysplasia, cyclosporine-induced folliculodystrophy, virus-associated trichodysplasia,3 and follicular dystrophy of immunosuppression.4 Trichodysplasia spinulosa can affect both adult and pediatric immunocompromised patients, including organ transplant recipients on immunosuppressants and cancer patients on chemotherapy.3 The condition also has been reported to precede the recurrence of lymphoma.5

Etiology

The connection of TS with a viral etiology was first demonstrated in 1999, and subsequently it was confirmed to be a polyomavirus.2 The family name of Polyomaviridae possesses a Greek derivation with poly- meaning many and -oma meaning cancer.3 This name was given after the polyomavirus induced multiple tumors in mice.3,6 This viral family consists of multiple naked viruses with a surrounding icosahedral capsid containing 3 structural proteins known as VP1, VP2, and VP3. Their life cycle is characterized by early and late phases with respective early and late protein formation.3

Polyomavirus infections maintain an asymptomatic and latent course in immunocompetent patients.7 The prevalence and manifestation of these viruses change when the host’s immune system is altered. The first identified JC virus and BK virus of the same family have been found at increased frequencies in blood and lymphoid tissue during host immunosuppression.6 Moreover, the Merkel cell polyomavirus detected in Merkel cell carcinoma is well documented in the dermatologic literature.6,8

A specific polyomavirus has been implicated in the majority of TS cases and has subsequently received the name of TS polyomavirus.9 As a polyomavirus, it similarly produces capsid antigens and large/small T antigens. Among the viral protein antigens produced, the large tumor or LT antigen represents one of the most potent viral proteins. It has been postulated to inhibit the retinoblastoma family of proteins, leading to increased inner root sheath cells that allow for further viral replication.9,10

The disease presents with folliculocentric papules localized mainly on the central face and ears, which grow central keratin spines or spicules that can become 1 to 3 mm in length. Coinciding alopecia and madarosis also may be present.9

Diagnosis

Histologic examination reveals abnormal follicular maturation and distension. Additionally, increased proliferation and amount of trichohyalin is seen within the inner root sheath cells. Further testing via viral culture, polymerase chain reaction, electron microscopy, or immunohistochemical stains can confirm the diagnosis. Such testing may not be warranted in all cases given that classic clinical findings coupled with routine histopathology staining can provide enough evidence.10,11

Management

Currently, a universal successful treatment for TS does not exist. There have been anecdotal successes reported with topical medications such as cidofovir ointment 1%, acyclovir combined with 2-deoxy-D-glucose and epigallocatechin, corticosteroids, topical tacrolimus, topical retinoids, and imiquimod. Additionally, success has been seen with oral minocycline, oral retinoids, valacyclovir, and valganciclovir, with the latter showing the best results. Patients also have shown improvement after modifying their immunosuppressive treatment regimen.10,12

Conclusion

Given the previously published case of TS preceding the recurrence of lymphoma,5 we notified our patient’s oncologist of this potential risk. Her history of lymphoma and immunosuppressive treatment 4 years prior may represent the etiology of the cutaneous presentation; however, the TS with concurrent colon cancer presented prior to starting immunosuppressive therapy, suggesting that it also may have been a paraneoplastic process and not just a sign of immunosuppression. Therefore, we recommend that patients who present with TS should be evaluated for underlying malignancy if not already diagnosed.

Case Report

An 82-year-old woman presented to the clinic with a rash on the face that had been present for a few months. She denied any treatment or prior occurrence. Her medical history was remarkable for non-Hodgkin lymphoma that had been successfully treated with chemotherapy 4 years prior. Additionally, she recently had been diagnosed with stage IV colon cancer. She reported that surgery had been scheduled and she would start adjuvant chemotherapy soon after.

On physical examination she exhibited perioral and perinasal erythematous papules with sparing of the vermilion border. A diagnosis of perioral dermatitis was made, and she was started on topical metronidazole. At 1-month follow-up, her condition had slightly worsened and she was subsequently started on doxycycline. When she returned to the clinic again the following month, physical examination revealed agminated folliculocentric papules with central spicules on the face, nose, ears, upper extremities (Figure 1), and trunk. The differential diagnosis included multiple minute digitate hyperkeratosis, spiculosis of multiple myeloma, and trichodysplasia spinulosa (TS).

A punch biopsy of 2 separate papules on the face and upper extremity revealed dilated follicles with enlarged trichohyalin granules and dyskeratosis (Figure 2), consistent with TS. Additional testing such as electron microscopy or polymerase chain reaction was not performed to keep the patient’s medical costs down; also, the strong clinical and histopathologic evidence did not warrant further testing.

The plan was to start split-face treatment with topical acyclovir and a topical retinoid to see which agent was more effective, but the patient declined until her chemotherapy regimen had concluded. Unfortunately, the patient died 3 months later due to colon cancer.

Comment

History and Presentation

Trichodysplasia spinulosa was first recognized as hairlike hyperkeratosis.1 The name by which it is currently known was later championed by Haycox et al.2 They reported a case of a 44-year-old man who underwent a combined renal-pancreas transplant and while taking immunosuppressive medication developed erythematous papules with follicular spinous processes and progressive alopecia.2 Other synonymous terms used for this condition include pilomatrix dysplasia, cyclosporine-induced folliculodystrophy, virus-associated trichodysplasia,3 and follicular dystrophy of immunosuppression.4 Trichodysplasia spinulosa can affect both adult and pediatric immunocompromised patients, including organ transplant recipients on immunosuppressants and cancer patients on chemotherapy.3 The condition also has been reported to precede the recurrence of lymphoma.5

Etiology

The connection of TS with a viral etiology was first demonstrated in 1999, and subsequently it was confirmed to be a polyomavirus.2 The family name of Polyomaviridae possesses a Greek derivation with poly- meaning many and -oma meaning cancer.3 This name was given after the polyomavirus induced multiple tumors in mice.3,6 This viral family consists of multiple naked viruses with a surrounding icosahedral capsid containing 3 structural proteins known as VP1, VP2, and VP3. Their life cycle is characterized by early and late phases with respective early and late protein formation.3

Polyomavirus infections maintain an asymptomatic and latent course in immunocompetent patients.7 The prevalence and manifestation of these viruses change when the host’s immune system is altered. The first identified JC virus and BK virus of the same family have been found at increased frequencies in blood and lymphoid tissue during host immunosuppression.6 Moreover, the Merkel cell polyomavirus detected in Merkel cell carcinoma is well documented in the dermatologic literature.6,8

A specific polyomavirus has been implicated in the majority of TS cases and has subsequently received the name of TS polyomavirus.9 As a polyomavirus, it similarly produces capsid antigens and large/small T antigens. Among the viral protein antigens produced, the large tumor or LT antigen represents one of the most potent viral proteins. It has been postulated to inhibit the retinoblastoma family of proteins, leading to increased inner root sheath cells that allow for further viral replication.9,10

The disease presents with folliculocentric papules localized mainly on the central face and ears, which grow central keratin spines or spicules that can become 1 to 3 mm in length. Coinciding alopecia and madarosis also may be present.9

Diagnosis

Histologic examination reveals abnormal follicular maturation and distension. Additionally, increased proliferation and amount of trichohyalin is seen within the inner root sheath cells. Further testing via viral culture, polymerase chain reaction, electron microscopy, or immunohistochemical stains can confirm the diagnosis. Such testing may not be warranted in all cases given that classic clinical findings coupled with routine histopathology staining can provide enough evidence.10,11

Management

Currently, a universal successful treatment for TS does not exist. There have been anecdotal successes reported with topical medications such as cidofovir ointment 1%, acyclovir combined with 2-deoxy-D-glucose and epigallocatechin, corticosteroids, topical tacrolimus, topical retinoids, and imiquimod. Additionally, success has been seen with oral minocycline, oral retinoids, valacyclovir, and valganciclovir, with the latter showing the best results. Patients also have shown improvement after modifying their immunosuppressive treatment regimen.10,12

Conclusion

Given the previously published case of TS preceding the recurrence of lymphoma,5 we notified our patient’s oncologist of this potential risk. Her history of lymphoma and immunosuppressive treatment 4 years prior may represent the etiology of the cutaneous presentation; however, the TS with concurrent colon cancer presented prior to starting immunosuppressive therapy, suggesting that it also may have been a paraneoplastic process and not just a sign of immunosuppression. Therefore, we recommend that patients who present with TS should be evaluated for underlying malignancy if not already diagnosed.

- Linke M, Geraud C, Sauer C, et al. Follicular erythematous papules with keratotic spicules. Acta Derm Venereol . 2014;94:493-494.

- Haycox CL, Kim S, Fleckman P, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa—a newly described folliculocentric viral infection in an immunocompromised host. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:268-271.

- Moens U, Ludvigsen M, Van Ghelue M. Human polyomaviruses in skin diseases [published online September 12, 2011]. Patholog Res Int. 2011;2011:123491.

- Matthews MR, Wang RC, Reddick RL, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia spinulosa: a case with electron microscopic and molecular detection of the trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated human polyomavirus. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:420-431.

- Osswald SS, Kulick KB, Tomaszewski MM, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia in a patient with lymphoma: a case report and review. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:721-725.

- Dalianis T, Hirsch HH. Human polyomavirus in disease and cancer. Virology. 2013;437:63-72.

- Tsuzuki S, Fukumoto H, Mine S, et al. Detection of trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated polyomavirus in a fatal case of myocarditis in a seven-month-old girl. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:5308-5312.

- Sadeghi M, Aronen M, Chen T, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus and trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated polyomavirus DNAs and antibodies in blood among the elderly. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:383.

- Van der Meijden E, Kazem S, Burgers MM, et al. Seroprevalence of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1355-1363.

- Krichhof MG, Shojania K, Hull MW, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: rare presentation of polyomavirus infection in immunocompromised patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18:430-435.

- Rianthavorn P, Posuwan N, Payungporn S, et al. Polyomavirus reactivation in pediatric patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2012;228:197-204.

- Wanat KA, Holler PD, Dentchev T, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia: characterization of a novel polyomavirus infection with therapeutic insights. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:219-223.

- Linke M, Geraud C, Sauer C, et al. Follicular erythematous papules with keratotic spicules. Acta Derm Venereol . 2014;94:493-494.

- Haycox CL, Kim S, Fleckman P, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa—a newly described folliculocentric viral infection in an immunocompromised host. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:268-271.

- Moens U, Ludvigsen M, Van Ghelue M. Human polyomaviruses in skin diseases [published online September 12, 2011]. Patholog Res Int. 2011;2011:123491.

- Matthews MR, Wang RC, Reddick RL, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia spinulosa: a case with electron microscopic and molecular detection of the trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated human polyomavirus. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:420-431.

- Osswald SS, Kulick KB, Tomaszewski MM, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia in a patient with lymphoma: a case report and review. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:721-725.

- Dalianis T, Hirsch HH. Human polyomavirus in disease and cancer. Virology. 2013;437:63-72.

- Tsuzuki S, Fukumoto H, Mine S, et al. Detection of trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated polyomavirus in a fatal case of myocarditis in a seven-month-old girl. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:5308-5312.

- Sadeghi M, Aronen M, Chen T, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus and trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated polyomavirus DNAs and antibodies in blood among the elderly. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:383.

- Van der Meijden E, Kazem S, Burgers MM, et al. Seroprevalence of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1355-1363.

- Krichhof MG, Shojania K, Hull MW, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: rare presentation of polyomavirus infection in immunocompromised patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18:430-435.

- Rianthavorn P, Posuwan N, Payungporn S, et al. Polyomavirus reactivation in pediatric patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2012;228:197-204.

- Wanat KA, Holler PD, Dentchev T, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia: characterization of a novel polyomavirus infection with therapeutic insights. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:219-223.

Practice Points

- Rashes have a life span and can evolve with time.

- If apparent straightforward conditions do not appear to respond to standard therapy, start to think outside the box for underlying potential causes.