User login

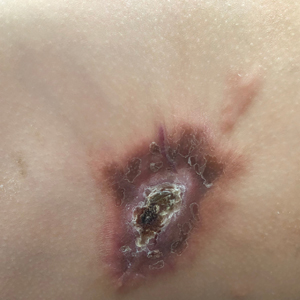

Plaque With Central Ulceration on the Abdomen

Plaque With Central Ulceration on the Abdomen

THE DIAGNOSIS: Plaquelike Myofibroblastic Tumor

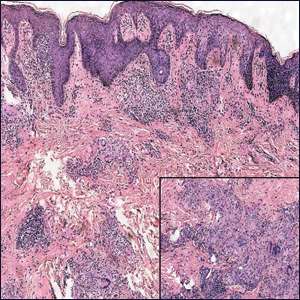

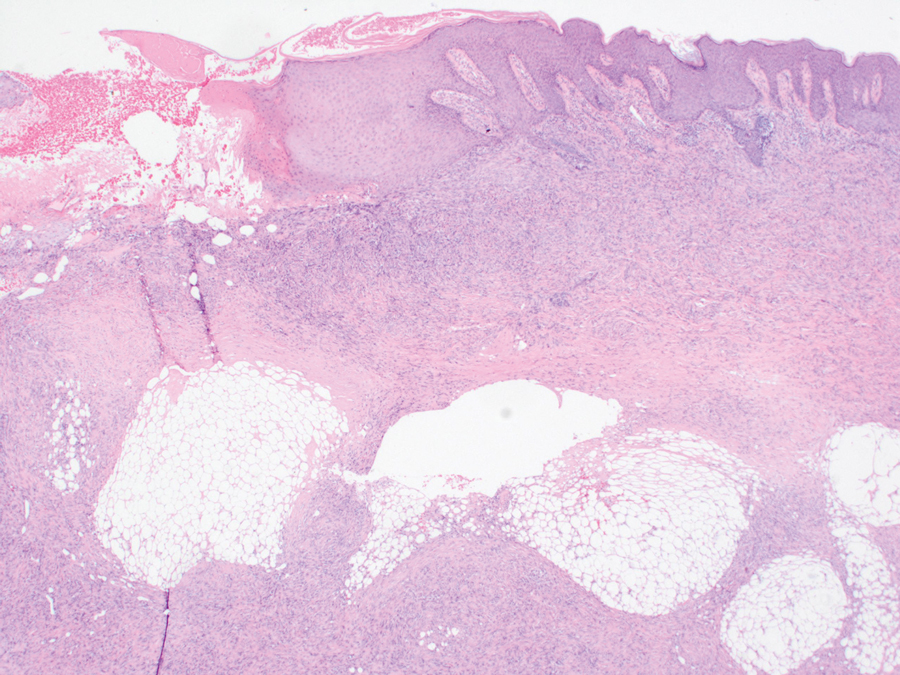

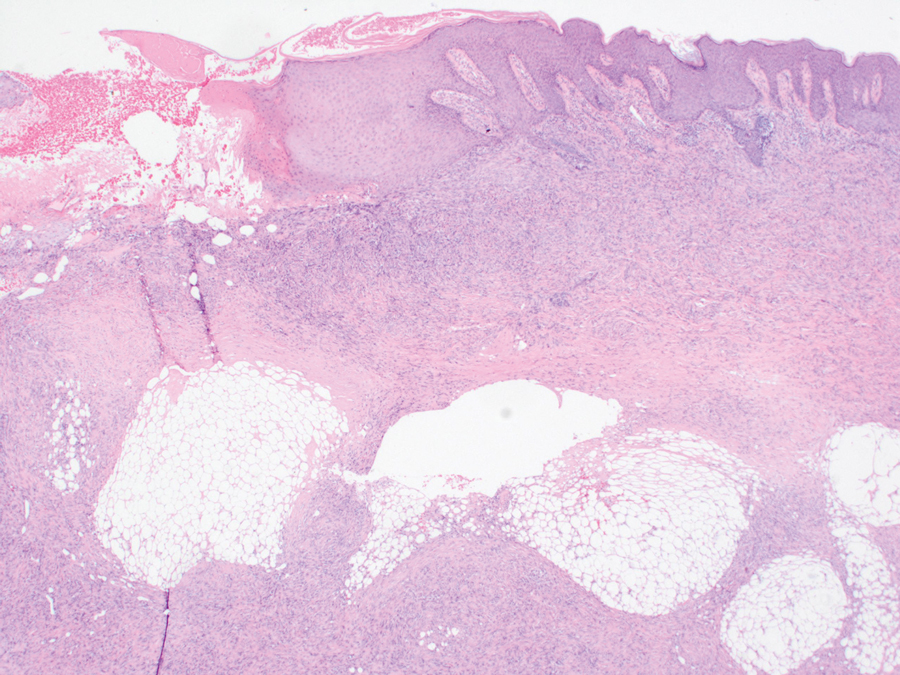

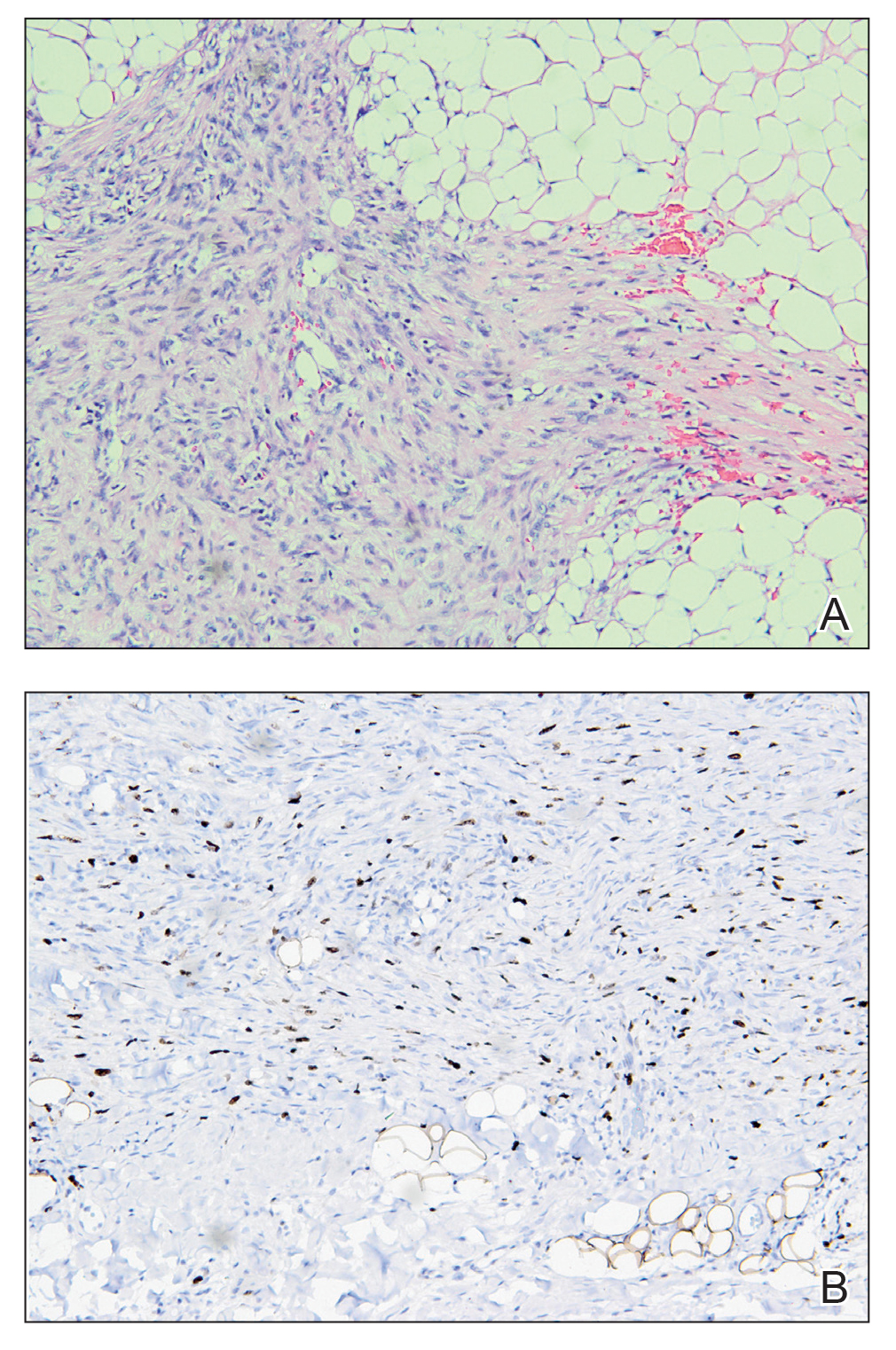

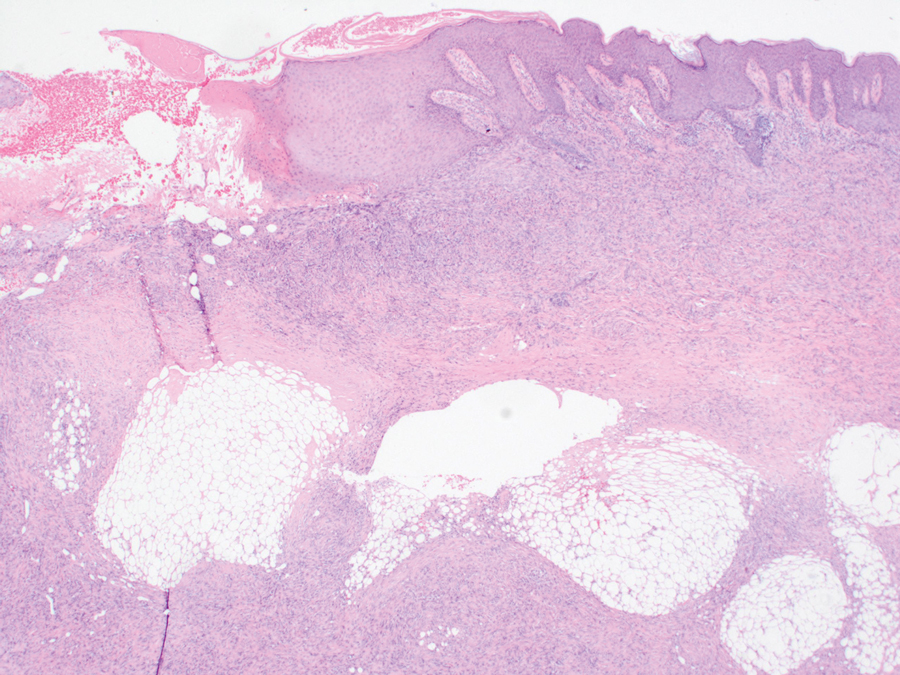

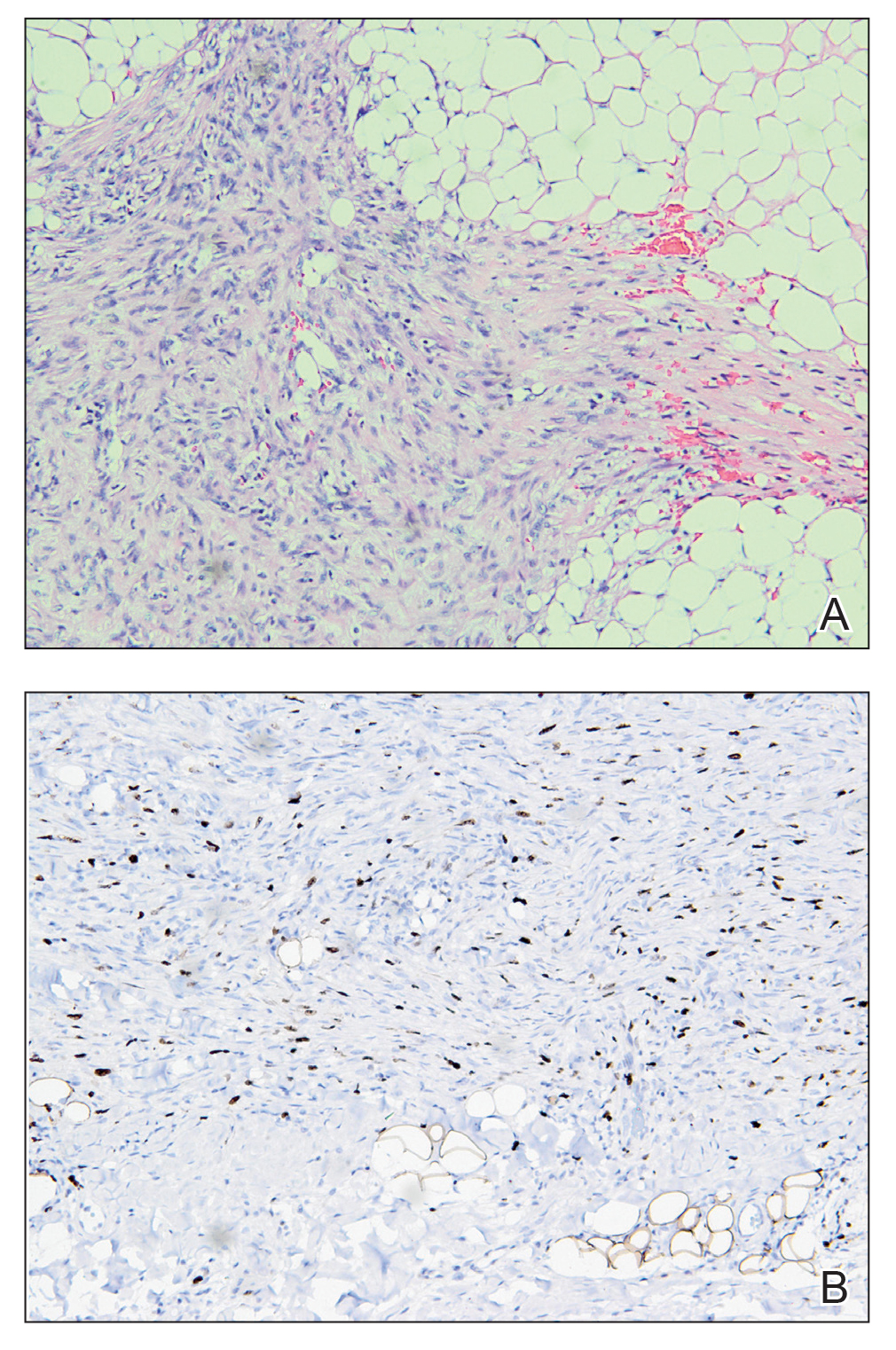

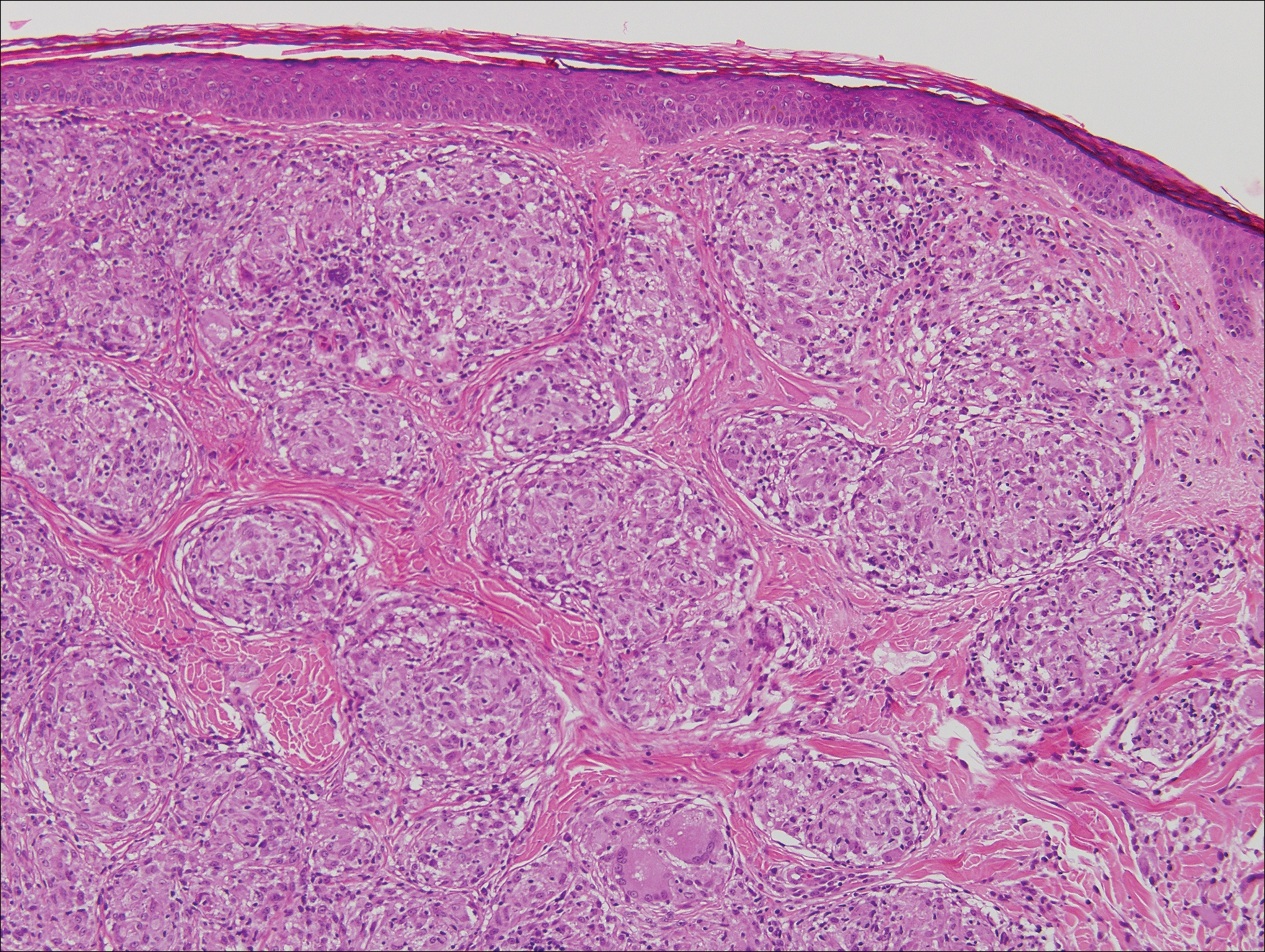

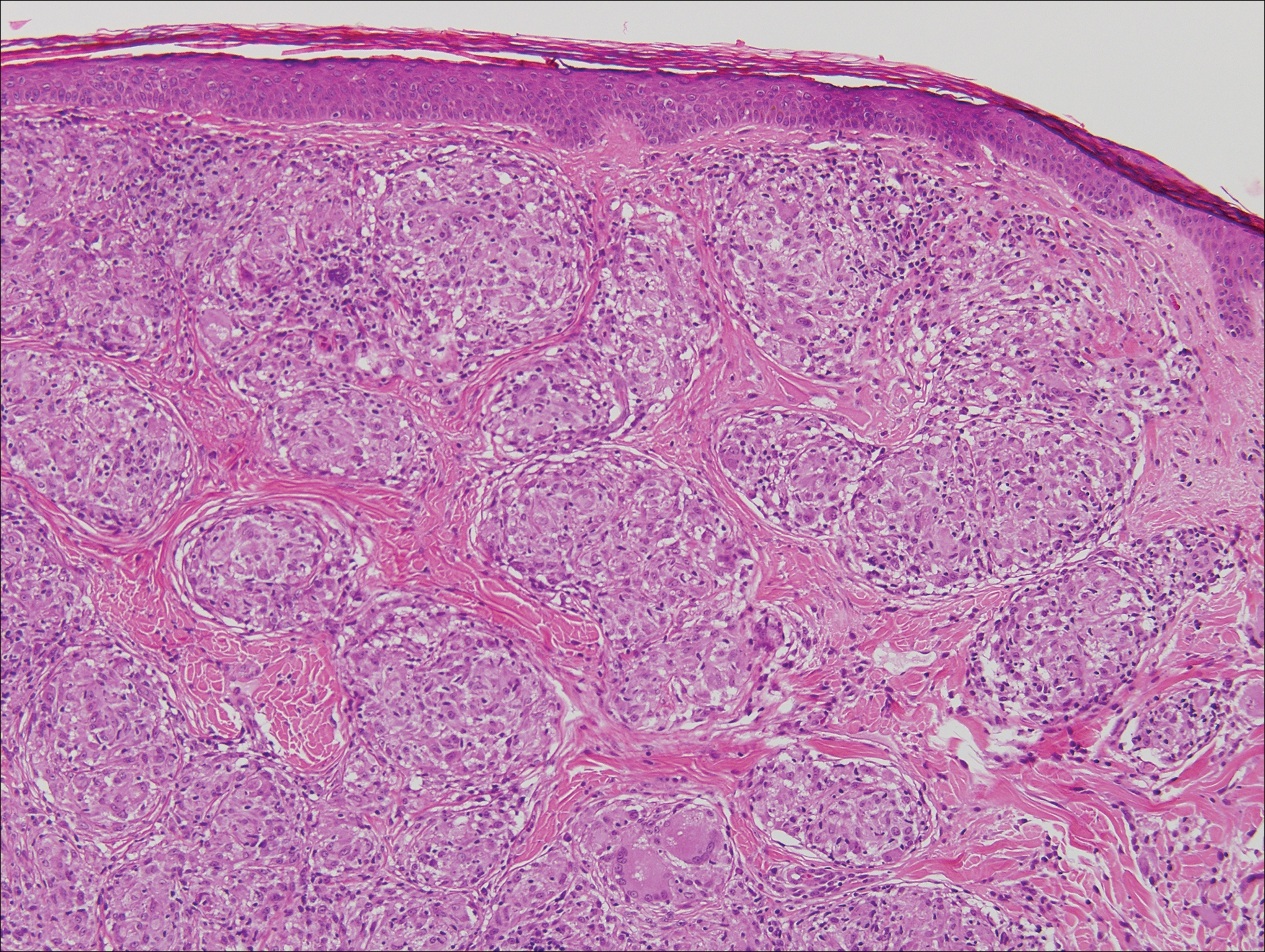

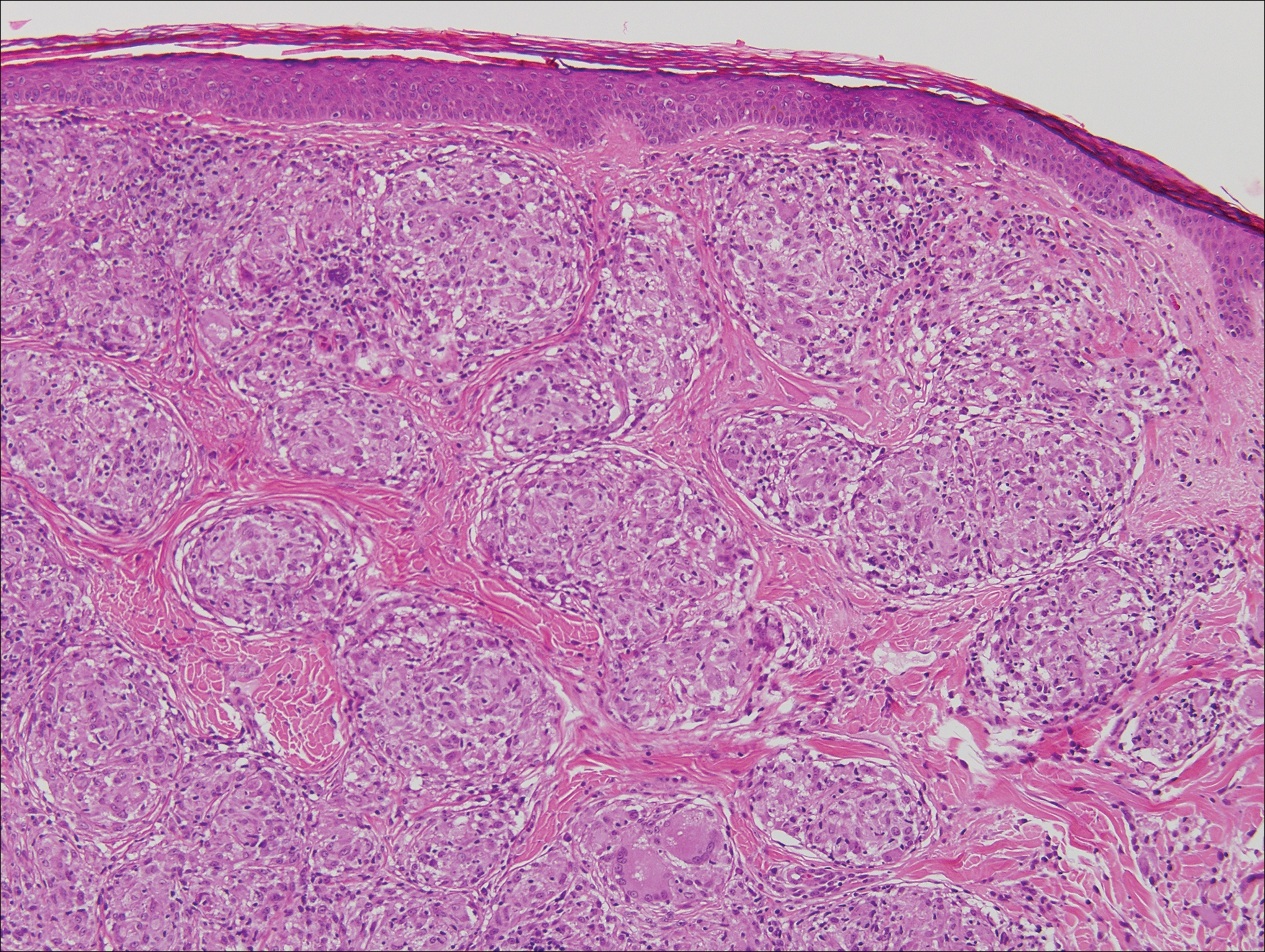

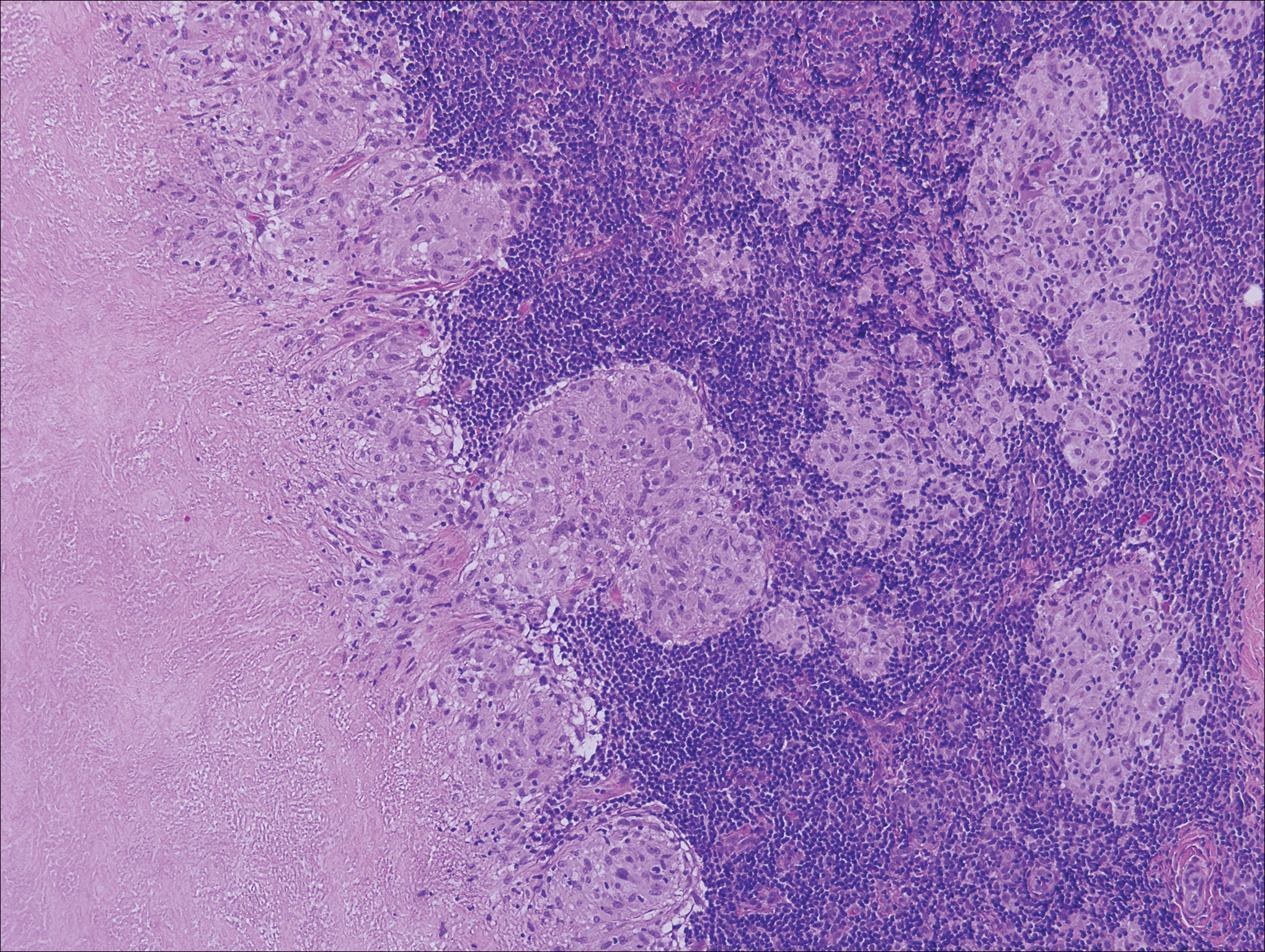

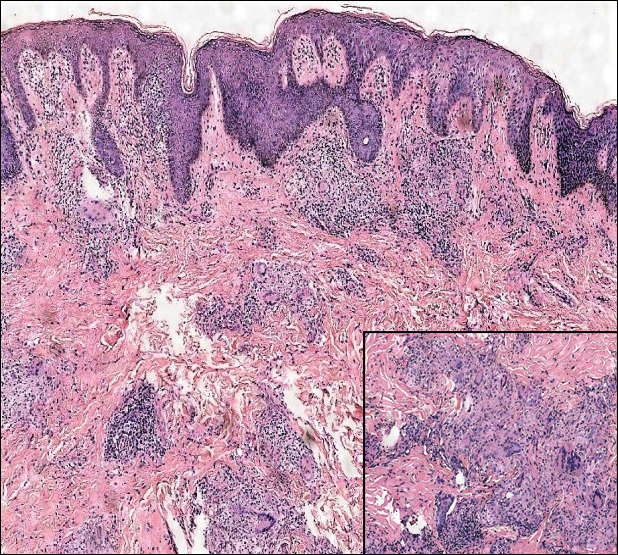

An incisional biopsy of the plaque demonstrated a hypercellular proliferation of bland spindle cells in the dermis that infiltrated the subcutis. The overlying epidermis was mildly acanthotic with both ulceration and follicular induction. There was trapping of individual adipocytes in a honeycomb pattern with foci of erythrocyte extravasation, microvesiculation, and widened fibrous septa (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry was positive for vimentin, actin, and smooth muscle actin (SMA)(Figure 2A). Variable positivity for Factor XIIIa antibodies was noted. CD68 staining was focal positive, suggesting fibrohistiocytic lineage. Expression of CD31, CD34, S100, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase was negative, and Ki-67 was present in less than 10% of cells (Figure 2B).

We reviewed the case in conjunction with a soft-tissue pathologist (Y.L.), and based on the clinical and immunophenotypic features, a diagnosis of plaquelike myofibroblastic tumor (PLMT) was made. The patient’s parents refused further treatment, and there was no sign of disease progression at 6-month follow-up.

Plaquelike myofibroblastic tumor is an unusual pediatric dermal tumor that was first described by Clarke et al1 in 2007. Clinical manifestation of PLMT on the right abdomen was unique in our patient, as the lesions typically present as indurated plaques on the lower back, but the central ulceration in our case resembled a report by Marqueling et al.2 Ulceration and induration of PLMT developing at 8 months of age can suggest an aggressive disease course corresponding with deep infiltration and is seen mostly in children.

The histopathologic features of PLMT include an acanthotic epidermis and follicular induction, which also are characteristic of dermatofibroma (DF). The proliferation of spindle cells extended deep into the fat with foci of erythrocyte extravasation and microvesiculation of the stroma similar to nodular fasciitis and proliferative fasciitis. The presentation of infiltrating and expanding fibrous septae and trapping of individual adipocytes in a honeycomb pattern is similar to dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). Most cases of PLMT are positive for SMA. Factor XIIIa typically is variably positive, and in one report, 31% (4/13) of cases showed positive staining for calponin.3 Rapid growth, ulceration, and recurrence emphasize that PLMT can be locally aggressive, similar to DFSP.4

The main differential diagnoses include DF and its variants, dermatomyofibroma, DFSP, and proliferative fasciitis.3,5 In the cases mentioned above, microscopic features were similar with a relatively well-circumscribed proliferation of spindle cells arranged in short fascicles through the entire reticular dermis, and the overlying epidermis was acanthotic.

Dermatofibroma commonly manifests in adults as a minor nodular lesion (commonly <1 cm), and usually is located on the legs. It has several clinical and histologic variants, including multiple clustered DF (MCDF)—a rare condition that has been reported in children and young adults and generally appears in the first and second decades of life. Of the reported cases of MCDF, immunohistochemical staining for SMA was performed in 8 cases. All these cases showed negative or minimal staining.3-5 Smooth muscle actin staining in DFs is negative, or weak and patchy, unlike in PLMT where it is diffuse, uniform, and strong.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans typically occurs in young adults and manifests as dermal and subcutaneous nodular/multinodular or plaquelike masses, with rare congenital cases. Immunohistochemical staining for CD34, which typically is firmly and diffusely positive, is the most reliable marker of DFSP.6 Factor XIIIA in DFSP typically is negative for focal staining, mainly at periphery or in scattered dendritic cells. The prognosis of DFSP generally is excellent, with local recurrences in up to 30% of cases and extremely low metastatic potential (essentially only in cases with fibrosarcomatous transformation).6 Dermatomyofibroma is another rare benign dermal myofibroblastic tumor that typically manifests with indurated hyperpigmented or erythematous plaques or nodules on the shoulders and torso.6 This condition occurs mainly in adolescents and young adults, unlike PLMT. The most striking features of dermatomyofibroma are the horizontal orientation of the spindle cell nuclei and the pattern of the proliferation concerning the adnexal structures, especially hair follicles. The hair follicles have a normal appearance, and the proliferation extends up to each follicle, then continues to the other side without any displacement of the follicle. Tumor cells are variably positive for SMA in dermatomyofibromas and are negative for muscle-specific actin, desmin, S100, CD34, and Factor XIIIA.6

Immunohistochemistry can be very useful in differentiating PLMT from other conditions. Neoplastic cells stain positively for CD34 but not for Factor XIIIa and SMA in cases of DFSP. Dermatofibroma and its variants always present with collagen trapping at the periphery of the lesions and may demonstrate foamy macrophages, hemosiderin, or plasma cells FXIIIA(+), CD34(-), and variable SMA reactivity. This positivity usually is less prominent in DF than in PLMT. Neoplastic cells in dermatomyofibroma often stain positive for calponin, but only focally for SMA. The clinical features of dermatomyofibroma include early onset, large size, multiple nodules, and plaquelike morphology. Moulonguet et al4 hypothesized that, although MCDF and PLMT appear to show some distinctive clinical and histologic features, they also show similarities that could suggest they form part of the myofibroblastic spectrum. Furthermore, Moradi et al7 also considered them as part of the same disease spectrum because of their overlapping clinical, histologic, and immunohistochemical features.

The microscopic features in our case are notable, as the lesion demonstrated overlying acanthosis and follicular induction, resembling DF. The stroma contained microvesicular changes and erythrocyte extravasation, characteristic of nodular or proliferative fasciitis. Additionally, densely packed spindle cells infiltrated deep into the subcutaneous adipose tissue, similar to DFSP.2,3 Our findings expand on the reported histopathologic spectrum of this tumor to date.

- Clarke JT, Clarke LE, Miller C, et al. Plaque-like myofibroblastic tumor of infancy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:E83-E87. doi:10.1111 /j.1525-1470.2007.00449.x

- Marqueling AL, Dasher D, Friedlander SF, et al. Plaque-like myofibroblastic tumor: report of three cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:600-607. doi:10.1111/pde.12185

- Sekar T, Mushtaq J, AlBadry W, et al. Plaque-like myofibroblastic tumor: a series of 2 cases of this unusual dermal tumor which occurs in infancy and early childhood. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2018;21:444-448. doi: 10.1177/1093526617746807

- Moulonguet I, Biaggi A, Eschard C, et al. Plaque-like myofibroblastic tumor: report of 4 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:767-772. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000869

- Virdi A, Baraldi C, Barisani A, et al. Plaque-like myofibroblastic tumor, a rare entity of childhood: possible pitfalls in differential diagnosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:389-392. doi:10.1111/cup.13441

- Cassarino DS. Diagnostic Pathology: Neoplastic Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2021.

- Moradi S, Mnayer L, Earle J, et al. Plaque-like dermatofibroma: case report of a rare entity. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2021;8:337-341. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology8030038

THE DIAGNOSIS: Plaquelike Myofibroblastic Tumor

An incisional biopsy of the plaque demonstrated a hypercellular proliferation of bland spindle cells in the dermis that infiltrated the subcutis. The overlying epidermis was mildly acanthotic with both ulceration and follicular induction. There was trapping of individual adipocytes in a honeycomb pattern with foci of erythrocyte extravasation, microvesiculation, and widened fibrous septa (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry was positive for vimentin, actin, and smooth muscle actin (SMA)(Figure 2A). Variable positivity for Factor XIIIa antibodies was noted. CD68 staining was focal positive, suggesting fibrohistiocytic lineage. Expression of CD31, CD34, S100, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase was negative, and Ki-67 was present in less than 10% of cells (Figure 2B).

We reviewed the case in conjunction with a soft-tissue pathologist (Y.L.), and based on the clinical and immunophenotypic features, a diagnosis of plaquelike myofibroblastic tumor (PLMT) was made. The patient’s parents refused further treatment, and there was no sign of disease progression at 6-month follow-up.

Plaquelike myofibroblastic tumor is an unusual pediatric dermal tumor that was first described by Clarke et al1 in 2007. Clinical manifestation of PLMT on the right abdomen was unique in our patient, as the lesions typically present as indurated plaques on the lower back, but the central ulceration in our case resembled a report by Marqueling et al.2 Ulceration and induration of PLMT developing at 8 months of age can suggest an aggressive disease course corresponding with deep infiltration and is seen mostly in children.

The histopathologic features of PLMT include an acanthotic epidermis and follicular induction, which also are characteristic of dermatofibroma (DF). The proliferation of spindle cells extended deep into the fat with foci of erythrocyte extravasation and microvesiculation of the stroma similar to nodular fasciitis and proliferative fasciitis. The presentation of infiltrating and expanding fibrous septae and trapping of individual adipocytes in a honeycomb pattern is similar to dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). Most cases of PLMT are positive for SMA. Factor XIIIa typically is variably positive, and in one report, 31% (4/13) of cases showed positive staining for calponin.3 Rapid growth, ulceration, and recurrence emphasize that PLMT can be locally aggressive, similar to DFSP.4

The main differential diagnoses include DF and its variants, dermatomyofibroma, DFSP, and proliferative fasciitis.3,5 In the cases mentioned above, microscopic features were similar with a relatively well-circumscribed proliferation of spindle cells arranged in short fascicles through the entire reticular dermis, and the overlying epidermis was acanthotic.

Dermatofibroma commonly manifests in adults as a minor nodular lesion (commonly <1 cm), and usually is located on the legs. It has several clinical and histologic variants, including multiple clustered DF (MCDF)—a rare condition that has been reported in children and young adults and generally appears in the first and second decades of life. Of the reported cases of MCDF, immunohistochemical staining for SMA was performed in 8 cases. All these cases showed negative or minimal staining.3-5 Smooth muscle actin staining in DFs is negative, or weak and patchy, unlike in PLMT where it is diffuse, uniform, and strong.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans typically occurs in young adults and manifests as dermal and subcutaneous nodular/multinodular or plaquelike masses, with rare congenital cases. Immunohistochemical staining for CD34, which typically is firmly and diffusely positive, is the most reliable marker of DFSP.6 Factor XIIIA in DFSP typically is negative for focal staining, mainly at periphery or in scattered dendritic cells. The prognosis of DFSP generally is excellent, with local recurrences in up to 30% of cases and extremely low metastatic potential (essentially only in cases with fibrosarcomatous transformation).6 Dermatomyofibroma is another rare benign dermal myofibroblastic tumor that typically manifests with indurated hyperpigmented or erythematous plaques or nodules on the shoulders and torso.6 This condition occurs mainly in adolescents and young adults, unlike PLMT. The most striking features of dermatomyofibroma are the horizontal orientation of the spindle cell nuclei and the pattern of the proliferation concerning the adnexal structures, especially hair follicles. The hair follicles have a normal appearance, and the proliferation extends up to each follicle, then continues to the other side without any displacement of the follicle. Tumor cells are variably positive for SMA in dermatomyofibromas and are negative for muscle-specific actin, desmin, S100, CD34, and Factor XIIIA.6

Immunohistochemistry can be very useful in differentiating PLMT from other conditions. Neoplastic cells stain positively for CD34 but not for Factor XIIIa and SMA in cases of DFSP. Dermatofibroma and its variants always present with collagen trapping at the periphery of the lesions and may demonstrate foamy macrophages, hemosiderin, or plasma cells FXIIIA(+), CD34(-), and variable SMA reactivity. This positivity usually is less prominent in DF than in PLMT. Neoplastic cells in dermatomyofibroma often stain positive for calponin, but only focally for SMA. The clinical features of dermatomyofibroma include early onset, large size, multiple nodules, and plaquelike morphology. Moulonguet et al4 hypothesized that, although MCDF and PLMT appear to show some distinctive clinical and histologic features, they also show similarities that could suggest they form part of the myofibroblastic spectrum. Furthermore, Moradi et al7 also considered them as part of the same disease spectrum because of their overlapping clinical, histologic, and immunohistochemical features.

The microscopic features in our case are notable, as the lesion demonstrated overlying acanthosis and follicular induction, resembling DF. The stroma contained microvesicular changes and erythrocyte extravasation, characteristic of nodular or proliferative fasciitis. Additionally, densely packed spindle cells infiltrated deep into the subcutaneous adipose tissue, similar to DFSP.2,3 Our findings expand on the reported histopathologic spectrum of this tumor to date.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Plaquelike Myofibroblastic Tumor

An incisional biopsy of the plaque demonstrated a hypercellular proliferation of bland spindle cells in the dermis that infiltrated the subcutis. The overlying epidermis was mildly acanthotic with both ulceration and follicular induction. There was trapping of individual adipocytes in a honeycomb pattern with foci of erythrocyte extravasation, microvesiculation, and widened fibrous septa (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry was positive for vimentin, actin, and smooth muscle actin (SMA)(Figure 2A). Variable positivity for Factor XIIIa antibodies was noted. CD68 staining was focal positive, suggesting fibrohistiocytic lineage. Expression of CD31, CD34, S100, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase was negative, and Ki-67 was present in less than 10% of cells (Figure 2B).

We reviewed the case in conjunction with a soft-tissue pathologist (Y.L.), and based on the clinical and immunophenotypic features, a diagnosis of plaquelike myofibroblastic tumor (PLMT) was made. The patient’s parents refused further treatment, and there was no sign of disease progression at 6-month follow-up.

Plaquelike myofibroblastic tumor is an unusual pediatric dermal tumor that was first described by Clarke et al1 in 2007. Clinical manifestation of PLMT on the right abdomen was unique in our patient, as the lesions typically present as indurated plaques on the lower back, but the central ulceration in our case resembled a report by Marqueling et al.2 Ulceration and induration of PLMT developing at 8 months of age can suggest an aggressive disease course corresponding with deep infiltration and is seen mostly in children.

The histopathologic features of PLMT include an acanthotic epidermis and follicular induction, which also are characteristic of dermatofibroma (DF). The proliferation of spindle cells extended deep into the fat with foci of erythrocyte extravasation and microvesiculation of the stroma similar to nodular fasciitis and proliferative fasciitis. The presentation of infiltrating and expanding fibrous septae and trapping of individual adipocytes in a honeycomb pattern is similar to dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). Most cases of PLMT are positive for SMA. Factor XIIIa typically is variably positive, and in one report, 31% (4/13) of cases showed positive staining for calponin.3 Rapid growth, ulceration, and recurrence emphasize that PLMT can be locally aggressive, similar to DFSP.4

The main differential diagnoses include DF and its variants, dermatomyofibroma, DFSP, and proliferative fasciitis.3,5 In the cases mentioned above, microscopic features were similar with a relatively well-circumscribed proliferation of spindle cells arranged in short fascicles through the entire reticular dermis, and the overlying epidermis was acanthotic.

Dermatofibroma commonly manifests in adults as a minor nodular lesion (commonly <1 cm), and usually is located on the legs. It has several clinical and histologic variants, including multiple clustered DF (MCDF)—a rare condition that has been reported in children and young adults and generally appears in the first and second decades of life. Of the reported cases of MCDF, immunohistochemical staining for SMA was performed in 8 cases. All these cases showed negative or minimal staining.3-5 Smooth muscle actin staining in DFs is negative, or weak and patchy, unlike in PLMT where it is diffuse, uniform, and strong.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans typically occurs in young adults and manifests as dermal and subcutaneous nodular/multinodular or plaquelike masses, with rare congenital cases. Immunohistochemical staining for CD34, which typically is firmly and diffusely positive, is the most reliable marker of DFSP.6 Factor XIIIA in DFSP typically is negative for focal staining, mainly at periphery or in scattered dendritic cells. The prognosis of DFSP generally is excellent, with local recurrences in up to 30% of cases and extremely low metastatic potential (essentially only in cases with fibrosarcomatous transformation).6 Dermatomyofibroma is another rare benign dermal myofibroblastic tumor that typically manifests with indurated hyperpigmented or erythematous plaques or nodules on the shoulders and torso.6 This condition occurs mainly in adolescents and young adults, unlike PLMT. The most striking features of dermatomyofibroma are the horizontal orientation of the spindle cell nuclei and the pattern of the proliferation concerning the adnexal structures, especially hair follicles. The hair follicles have a normal appearance, and the proliferation extends up to each follicle, then continues to the other side without any displacement of the follicle. Tumor cells are variably positive for SMA in dermatomyofibromas and are negative for muscle-specific actin, desmin, S100, CD34, and Factor XIIIA.6

Immunohistochemistry can be very useful in differentiating PLMT from other conditions. Neoplastic cells stain positively for CD34 but not for Factor XIIIa and SMA in cases of DFSP. Dermatofibroma and its variants always present with collagen trapping at the periphery of the lesions and may demonstrate foamy macrophages, hemosiderin, or plasma cells FXIIIA(+), CD34(-), and variable SMA reactivity. This positivity usually is less prominent in DF than in PLMT. Neoplastic cells in dermatomyofibroma often stain positive for calponin, but only focally for SMA. The clinical features of dermatomyofibroma include early onset, large size, multiple nodules, and plaquelike morphology. Moulonguet et al4 hypothesized that, although MCDF and PLMT appear to show some distinctive clinical and histologic features, they also show similarities that could suggest they form part of the myofibroblastic spectrum. Furthermore, Moradi et al7 also considered them as part of the same disease spectrum because of their overlapping clinical, histologic, and immunohistochemical features.

The microscopic features in our case are notable, as the lesion demonstrated overlying acanthosis and follicular induction, resembling DF. The stroma contained microvesicular changes and erythrocyte extravasation, characteristic of nodular or proliferative fasciitis. Additionally, densely packed spindle cells infiltrated deep into the subcutaneous adipose tissue, similar to DFSP.2,3 Our findings expand on the reported histopathologic spectrum of this tumor to date.

- Clarke JT, Clarke LE, Miller C, et al. Plaque-like myofibroblastic tumor of infancy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:E83-E87. doi:10.1111 /j.1525-1470.2007.00449.x

- Marqueling AL, Dasher D, Friedlander SF, et al. Plaque-like myofibroblastic tumor: report of three cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:600-607. doi:10.1111/pde.12185

- Sekar T, Mushtaq J, AlBadry W, et al. Plaque-like myofibroblastic tumor: a series of 2 cases of this unusual dermal tumor which occurs in infancy and early childhood. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2018;21:444-448. doi: 10.1177/1093526617746807

- Moulonguet I, Biaggi A, Eschard C, et al. Plaque-like myofibroblastic tumor: report of 4 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:767-772. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000869

- Virdi A, Baraldi C, Barisani A, et al. Plaque-like myofibroblastic tumor, a rare entity of childhood: possible pitfalls in differential diagnosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:389-392. doi:10.1111/cup.13441

- Cassarino DS. Diagnostic Pathology: Neoplastic Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2021.

- Moradi S, Mnayer L, Earle J, et al. Plaque-like dermatofibroma: case report of a rare entity. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2021;8:337-341. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology8030038

- Clarke JT, Clarke LE, Miller C, et al. Plaque-like myofibroblastic tumor of infancy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:E83-E87. doi:10.1111 /j.1525-1470.2007.00449.x

- Marqueling AL, Dasher D, Friedlander SF, et al. Plaque-like myofibroblastic tumor: report of three cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:600-607. doi:10.1111/pde.12185

- Sekar T, Mushtaq J, AlBadry W, et al. Plaque-like myofibroblastic tumor: a series of 2 cases of this unusual dermal tumor which occurs in infancy and early childhood. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2018;21:444-448. doi: 10.1177/1093526617746807

- Moulonguet I, Biaggi A, Eschard C, et al. Plaque-like myofibroblastic tumor: report of 4 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:767-772. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000869

- Virdi A, Baraldi C, Barisani A, et al. Plaque-like myofibroblastic tumor, a rare entity of childhood: possible pitfalls in differential diagnosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:389-392. doi:10.1111/cup.13441

- Cassarino DS. Diagnostic Pathology: Neoplastic Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2021.

- Moradi S, Mnayer L, Earle J, et al. Plaque-like dermatofibroma: case report of a rare entity. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2021;8:337-341. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology8030038

Plaque With Central Ulceration on the Abdomen

Plaque With Central Ulceration on the Abdomen

A 14-month-old girl presented to the dermatology department with a firm asymptomatic lesion on the abdomen of 6 months’ duration. The lesion started as a flesh-colored papule and developed slowly into an indurated plaque that darkened in color. The patient had no history of trauma to the area. Physical examination revealed a dark reddish–brown, indurated, irregularly shaped plaque with central ulceration and elevated borders on the right abdomen. The plaque measured 2×3 cm with a few smaller satellite nodules distributed along the periphery. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed a multinodular proliferation in the dermis and subcutis of the right abdomen.

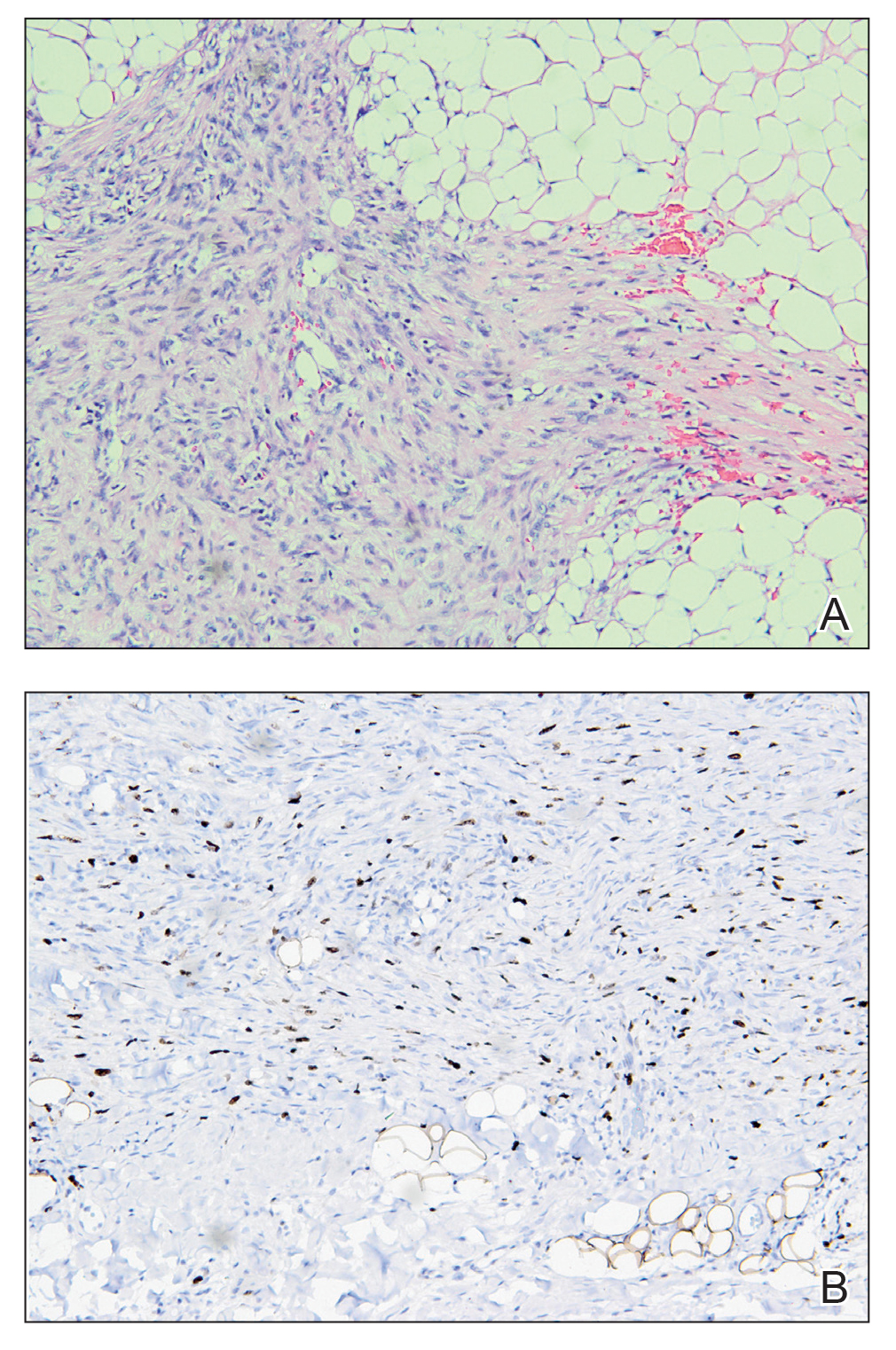

Perianal Condyloma Acuminatum-like Plaque

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Crohn Disease

Crohn disease (CD), a chronic inflammatory granulomatous disease of the gastrointestinal tract, has a wide spectrum of presentations.1 The condition may affect the vulva, perineum, or perianal skin by direct extension from the gastrointestinal tract or may appear as a separate and distinct cutaneous focus of disease referred to as metastatic Crohn disease (MCD).2

Cutaneous lesions of MCD include ulcers, fissures, sinus tracts, abscesses, and vegetative plaques, which typically extend in continuity with sites of intra-abdominal disease to the perineum, buttocks, or abdominal wall, as well as ostomy sites or incisional scars. Erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum are the most common nonspecific cutaneous manifestations. Other cutaneous lesions described in CD include polyarteritis nodosa, psoriasis, erythema multiforme, erythema elevatum diutinum, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, acne fulminans, pyoderma faciale, neutrophilic lobular panniculitis, granulomatous vasculitis, and porokeratosis.3

Perianal skin is the most common site of cutaneous involvement in individuals with CD. It is a marker of more severe disease and is associated with multiple surgical interventions and frequent relapses and has been reported in 22% of patients with CD.4 Most already had an existing diagnosis of gastrointestinal CD, which was active in one-third of individuals; however, 20% presented with disease at nongastrointestinal sites 2 months to 4 years prior to developing the gastrointestinal CD manifestations.5 Our patient presented with lesions on the perianal skin of 2 years' duration and a 6-month history of diarrhea. A colonoscopy demonstrated shallow ulcers involving the ileocecal portion of the gut, colon, and rectum. A biopsy from intestinal mucosal tissue showed acute and chronic inflammation with necrosis mixed with granulomatous inflammation, suggestive of CD.

Microscopically, the dominant histologic features of MCD are similar to those of bowel lesions, including an inflammatory infiltrate commonly consisting of sterile noncaseating sarcoidal granulomas, foreign body and Langhans giant cells, epithelioid histiocytes, and plasma cells surrounded by numerous mononuclear cells within the dermis with occasional extension into the subcutis (quiz image). Less common features include collagen degeneration, an infiltrate rich in eosinophils, dermal edema, and mixed lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis.6

Metastatic CD often is misdiagnosed. A detailed history and physical examination may help narrow the differential; however, biopsy is necessary to establish a diagnosis of MCD. The histologic differential diagnosis of sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation of genital skin includes sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, leprosy or other mycobacterial and parasitic infection, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and granulomatous infiltrate associated with certain exogenous material (eg, silica, zirconium, beryllium, tattoo pigment).

Sarcoidosis is a multiorgan disease that most frequently affects the lungs, skin, and lymph nodes. Its etiopathogenesis has not been clearly elucidated.7 Cutaneous lesions are present in 20% to 35% of patients.8 Given the wide variability of clinical manifestations, cutaneous sarcoidosis is another one of the great imitators. Cutaneous lesions are classified as specific and nonspecific depending on the presence of noncaseating granulomas on histologic studies and include maculopapules, plaques, nodules, lupus pernio, scar infiltration, alopecia, ulcerative lesions, and hypopigmentation. The most common nonspecific lesion of cutaneous sarcoidosis is erythema nodosum. Other manifestations include calcifications, prurigo, erythema multiforme, nail clubbing, and Sweet syndrome.9

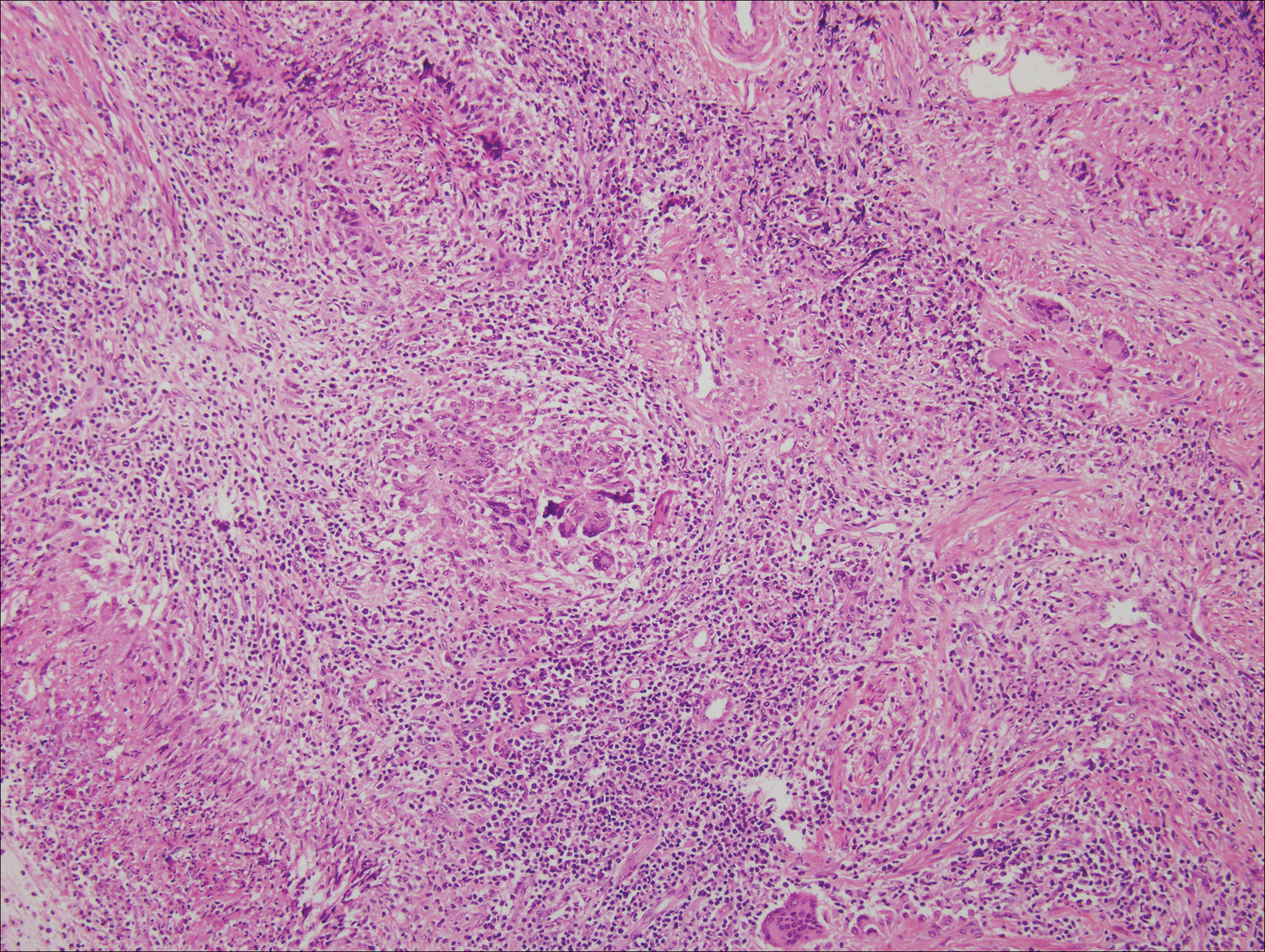

Histologic findings in sarcoidosis generally are independent of the respective organ and clinical disease presentation. The epidermis usually remains unchanged, whereas the dermis shows a superficial and deep nodular granulomatous infiltrate. Granulomas consist of epithelioid cells with only few giant cells and no surrounding lymphocytes or a very sparse lymphocytic infiltrate ("naked" granuloma)(Figure 1). Foreign bodies, including silica, are known to be able to induce sarcoid granulomas, especially in patients with sarcoidosis. A sarcoidal reaction in long-standing scar tissue points to a diagnosis of sarcoidosis.10

Cutaneous tuberculosis primarily is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and less frequently Mycobacterium bovis.11,12 The manifestations of cutaneous tuberculosis depends on various factors such as the type of infection, mode of dissemination, host immunity, and whether it is a first-time infection or a recurrence. In Europe, the head and neck regions are most frequently affected.13 Lesions present as red-brown papules coalescing into a plaque. The tissue, especially in central parts of the lesion, is fragile (probe phenomenon). Diascopy shows the typical apple jelly-like color.

Histologically, cutaneous tuberculosis is characterized by typical tuberculoid granulomas with epithelioid cells and Langhans giant cells at the center surrounded by lymphocytes (Figure 2). Caseous necrosis as well as fibrosis may occur,14,15 and the granulomas tend to coalesce.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis, is a complex, multisystemic disease with varying manifestations. The condition has been defined as a necrotizing granulomatous inflammation usually involving the upper and lower respiratory tracts and necrotizing vasculitis affecting predominantly small- to medium-sized vessels.16 The etiology of GPA is thought to be linked to environmental and infectious triggers inciting onset of disease in genetically predisposed individuals. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies play an important role in the pathogenesis of this disease. Cutaneous vasculitis secondary to GPA can present as papules, nodules, palpable purpura, ulcers resembling pyoderma gangrenosum, or necrotizing lesions leading to gangrene.17

The predominant histopathologic pattern in cutaneous lesions of GPA is leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which is present in up to 50% of biopsies.18 Characteristic findings that aid in establishing the diagnosis include histologic evidence of focal necrosis, fibrinoid degeneration, palisading granuloma surrounding neutrophils (Figure 3), and granulomatous vasculitis involving muscular vessel walls.19 Nonpalisading foci of necrosis or fibrinoid degeneration may precede the development of the typical palisading granuloma.20

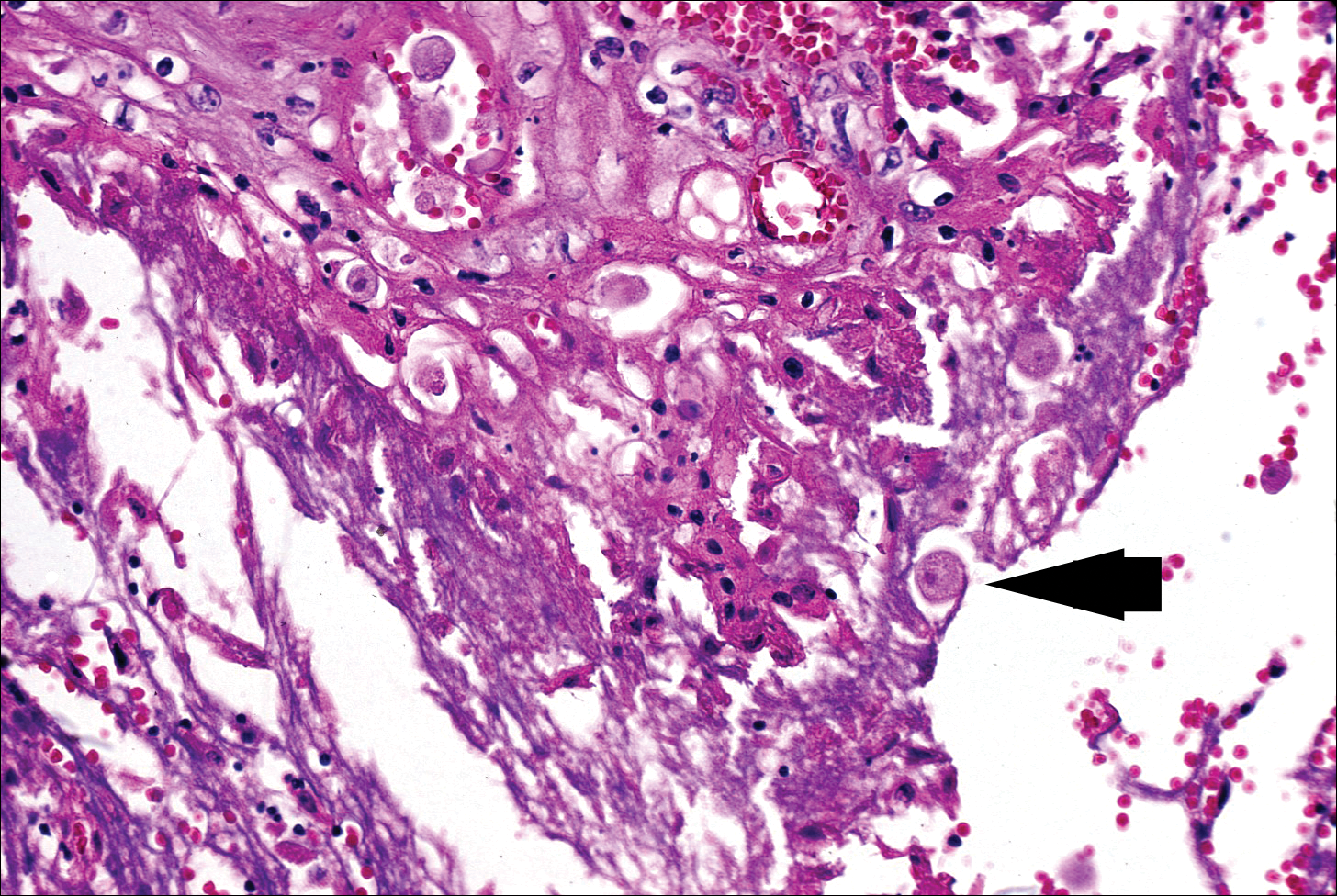

The typical histopathologic pattern of cutaneous amebiasis is ulceration with vascular necrosis (Figure 4).21 The organisms have prominent round nuclei and nucleoli and the cytoplasm may have a scalloped border.

- Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD. Landmark article Oct 25, 1932. regional ileitis. a pathologic and clinical entity. by Burril B. Crohn, Leon Gonzburg and Gordon D. Oppenheimer. JAMA. 1984;251:73-79.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn's disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- Weedon D. Miscellaneous conditions. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:554.

- Samitz MH, Dana Jr AS, Rosenberg P. Cutaneous vasculitis in association with Crohn's disease. Cutis. 1970;6:51-56.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Aberumand B, Howard J, Howard J. Metastatic Crohn's disease: an approach to an uncommon but important cutaneous disorder: a review [published online January 3, 2017]. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:8192150.

- Mahony J, Helms SE, Brodell RT. The sarcoidal granuloma: a unifying hypothesis for an enigmatic response. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:654-659.

- Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolf K, et al. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2003.

- Fernandez-Faith E, McDonnell J. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: differential diagnosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:276-287.

- Walsh NM, Hanly JG, Tremaine R, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and foreign bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:203-207.

- Semaan R, Traboulsi R, Kanj S. Primary Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex cutaneous infection: report of two cases and literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:472-477.

- Lai-Cheong JE, Perez A, Tang V, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of tuberculosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:461-466.

- Marcoval J, Servitje O, Moreno A, et al. Lupus vulgaris. clinical, histopathologic, and bacteriologic study of 10 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:404-407.

- Tronnier M, Wolff H. Dermatosen mit granulomatöser Entzündung. Histopathologie der Haut. In: Kerl H, Garbe C, Cerroni L, et al, eds. New York, NY: Springer; 2003.

- Min KW, Ko JY, Park CK. Histopathological spectrum of cutaneous tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:582-595.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1-11.

- Comfere NI, Macaron NC, Gibson LE. Cutaneous manifestations of Wegener's granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 17 patients and correlation to antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody status. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:739-747.

- Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Berti E. Skin involvement in cutaneous and systemic vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:467-476.

- Bramsiepe I, Danz B, Heine R, et al. Primary cutaneous manifestation of Wegener's granulomatosis [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;27:1429-1432.

- Daoud MS, Gibson LE, DeRemee RA, et al. Cutaneous Wegener's granulomatosis: clinical, histopathologic, and immunopathologic features of thirty patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:605-612.

- Guidry JA, Downing C, Tyring SK. Deep fungal infections, blastomycosis-like pyoderma, and granulomatous sexually transmitted infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:595-607.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Crohn Disease

Crohn disease (CD), a chronic inflammatory granulomatous disease of the gastrointestinal tract, has a wide spectrum of presentations.1 The condition may affect the vulva, perineum, or perianal skin by direct extension from the gastrointestinal tract or may appear as a separate and distinct cutaneous focus of disease referred to as metastatic Crohn disease (MCD).2

Cutaneous lesions of MCD include ulcers, fissures, sinus tracts, abscesses, and vegetative plaques, which typically extend in continuity with sites of intra-abdominal disease to the perineum, buttocks, or abdominal wall, as well as ostomy sites or incisional scars. Erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum are the most common nonspecific cutaneous manifestations. Other cutaneous lesions described in CD include polyarteritis nodosa, psoriasis, erythema multiforme, erythema elevatum diutinum, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, acne fulminans, pyoderma faciale, neutrophilic lobular panniculitis, granulomatous vasculitis, and porokeratosis.3

Perianal skin is the most common site of cutaneous involvement in individuals with CD. It is a marker of more severe disease and is associated with multiple surgical interventions and frequent relapses and has been reported in 22% of patients with CD.4 Most already had an existing diagnosis of gastrointestinal CD, which was active in one-third of individuals; however, 20% presented with disease at nongastrointestinal sites 2 months to 4 years prior to developing the gastrointestinal CD manifestations.5 Our patient presented with lesions on the perianal skin of 2 years' duration and a 6-month history of diarrhea. A colonoscopy demonstrated shallow ulcers involving the ileocecal portion of the gut, colon, and rectum. A biopsy from intestinal mucosal tissue showed acute and chronic inflammation with necrosis mixed with granulomatous inflammation, suggestive of CD.

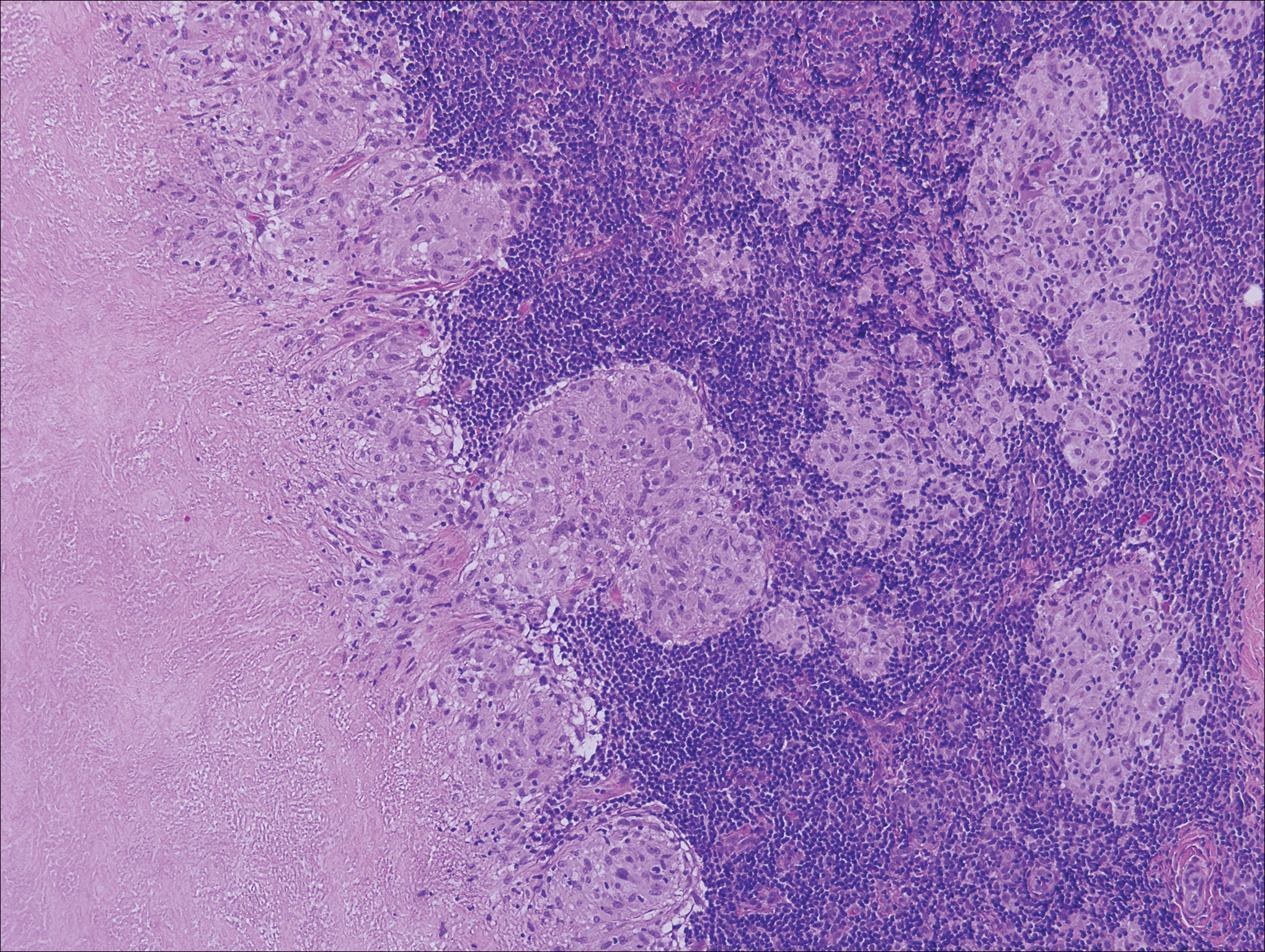

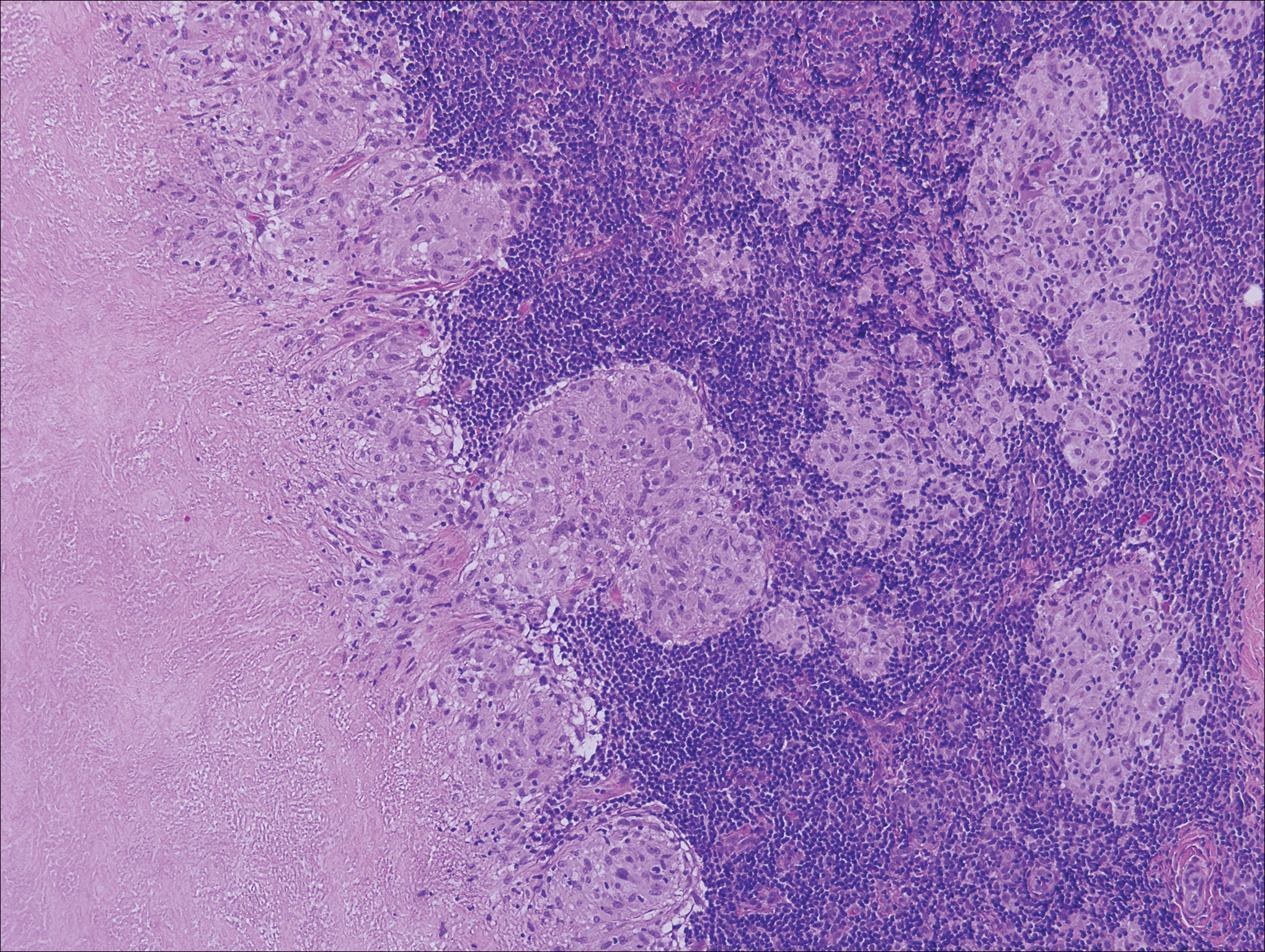

Microscopically, the dominant histologic features of MCD are similar to those of bowel lesions, including an inflammatory infiltrate commonly consisting of sterile noncaseating sarcoidal granulomas, foreign body and Langhans giant cells, epithelioid histiocytes, and plasma cells surrounded by numerous mononuclear cells within the dermis with occasional extension into the subcutis (quiz image). Less common features include collagen degeneration, an infiltrate rich in eosinophils, dermal edema, and mixed lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis.6

Metastatic CD often is misdiagnosed. A detailed history and physical examination may help narrow the differential; however, biopsy is necessary to establish a diagnosis of MCD. The histologic differential diagnosis of sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation of genital skin includes sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, leprosy or other mycobacterial and parasitic infection, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and granulomatous infiltrate associated with certain exogenous material (eg, silica, zirconium, beryllium, tattoo pigment).

Sarcoidosis is a multiorgan disease that most frequently affects the lungs, skin, and lymph nodes. Its etiopathogenesis has not been clearly elucidated.7 Cutaneous lesions are present in 20% to 35% of patients.8 Given the wide variability of clinical manifestations, cutaneous sarcoidosis is another one of the great imitators. Cutaneous lesions are classified as specific and nonspecific depending on the presence of noncaseating granulomas on histologic studies and include maculopapules, plaques, nodules, lupus pernio, scar infiltration, alopecia, ulcerative lesions, and hypopigmentation. The most common nonspecific lesion of cutaneous sarcoidosis is erythema nodosum. Other manifestations include calcifications, prurigo, erythema multiforme, nail clubbing, and Sweet syndrome.9

Histologic findings in sarcoidosis generally are independent of the respective organ and clinical disease presentation. The epidermis usually remains unchanged, whereas the dermis shows a superficial and deep nodular granulomatous infiltrate. Granulomas consist of epithelioid cells with only few giant cells and no surrounding lymphocytes or a very sparse lymphocytic infiltrate ("naked" granuloma)(Figure 1). Foreign bodies, including silica, are known to be able to induce sarcoid granulomas, especially in patients with sarcoidosis. A sarcoidal reaction in long-standing scar tissue points to a diagnosis of sarcoidosis.10

Cutaneous tuberculosis primarily is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and less frequently Mycobacterium bovis.11,12 The manifestations of cutaneous tuberculosis depends on various factors such as the type of infection, mode of dissemination, host immunity, and whether it is a first-time infection or a recurrence. In Europe, the head and neck regions are most frequently affected.13 Lesions present as red-brown papules coalescing into a plaque. The tissue, especially in central parts of the lesion, is fragile (probe phenomenon). Diascopy shows the typical apple jelly-like color.

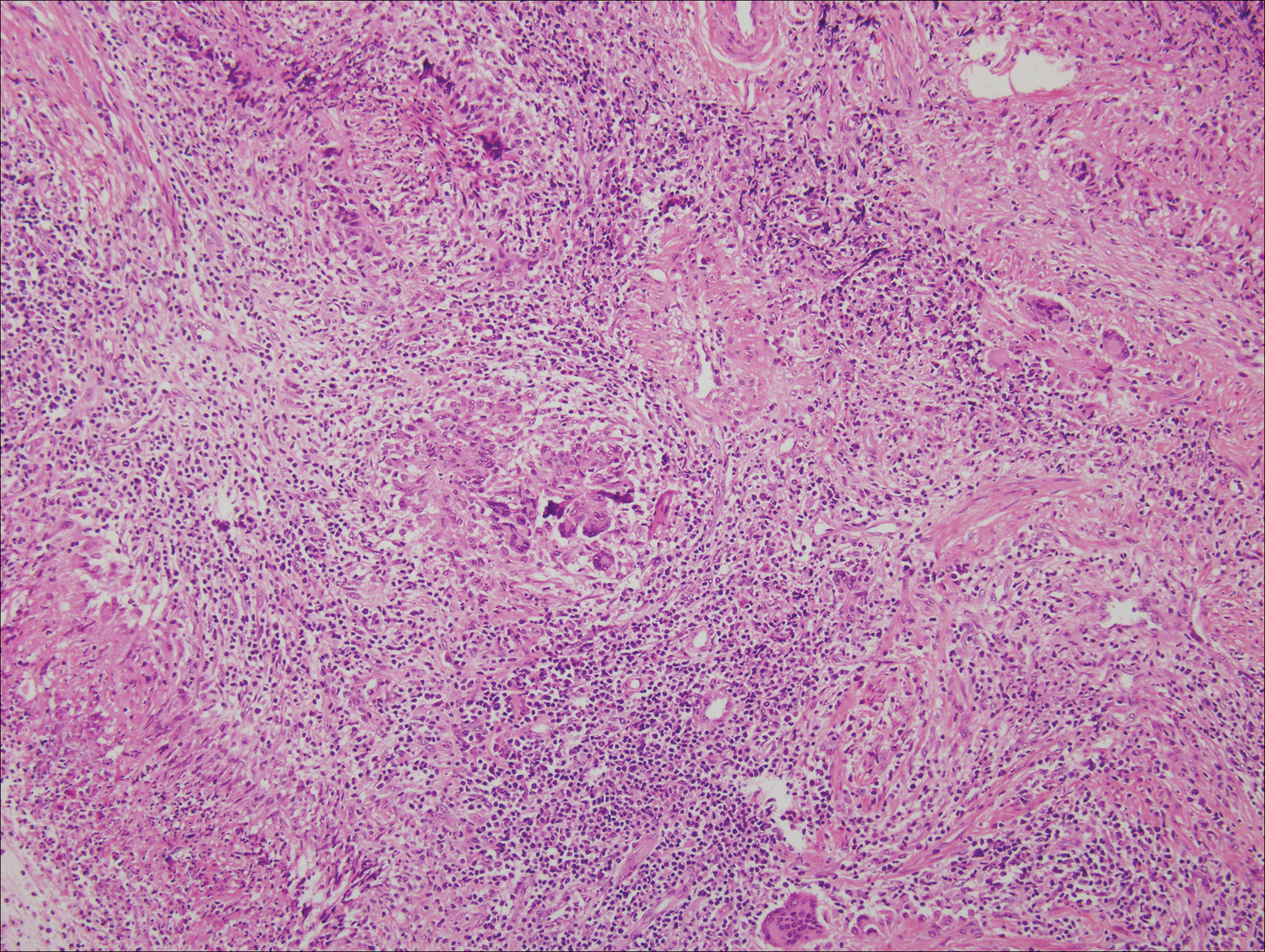

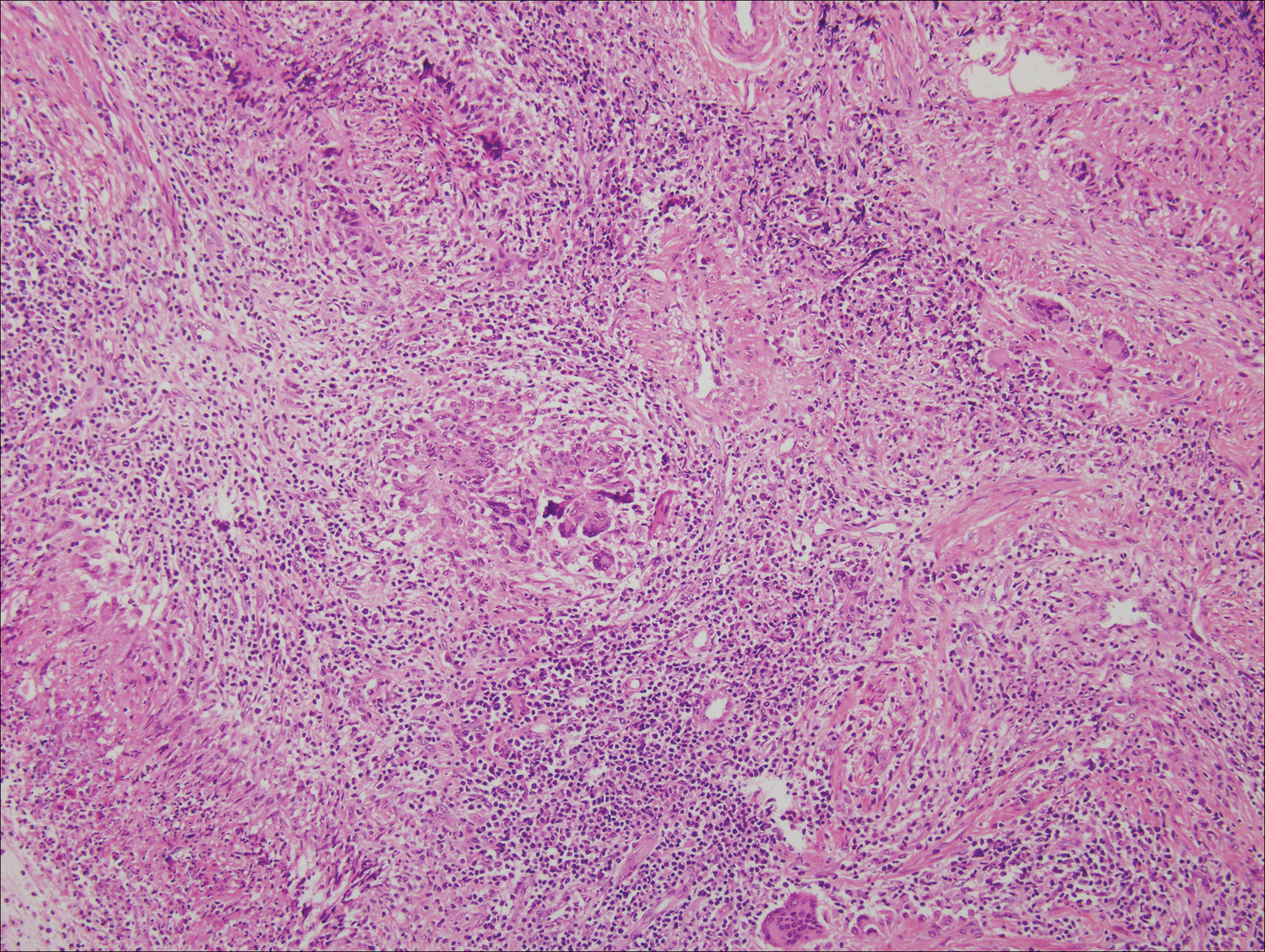

Histologically, cutaneous tuberculosis is characterized by typical tuberculoid granulomas with epithelioid cells and Langhans giant cells at the center surrounded by lymphocytes (Figure 2). Caseous necrosis as well as fibrosis may occur,14,15 and the granulomas tend to coalesce.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis, is a complex, multisystemic disease with varying manifestations. The condition has been defined as a necrotizing granulomatous inflammation usually involving the upper and lower respiratory tracts and necrotizing vasculitis affecting predominantly small- to medium-sized vessels.16 The etiology of GPA is thought to be linked to environmental and infectious triggers inciting onset of disease in genetically predisposed individuals. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies play an important role in the pathogenesis of this disease. Cutaneous vasculitis secondary to GPA can present as papules, nodules, palpable purpura, ulcers resembling pyoderma gangrenosum, or necrotizing lesions leading to gangrene.17

The predominant histopathologic pattern in cutaneous lesions of GPA is leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which is present in up to 50% of biopsies.18 Characteristic findings that aid in establishing the diagnosis include histologic evidence of focal necrosis, fibrinoid degeneration, palisading granuloma surrounding neutrophils (Figure 3), and granulomatous vasculitis involving muscular vessel walls.19 Nonpalisading foci of necrosis or fibrinoid degeneration may precede the development of the typical palisading granuloma.20

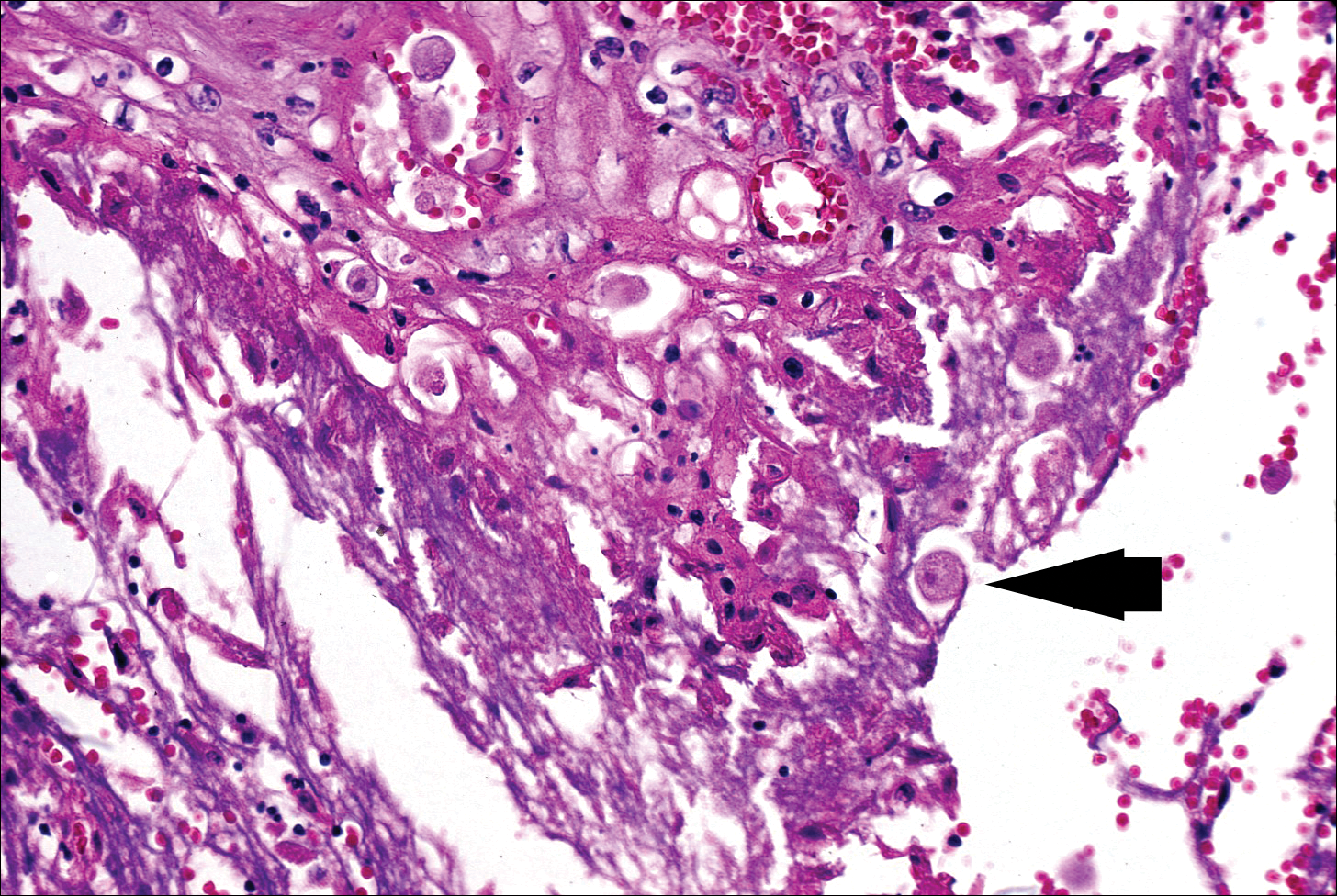

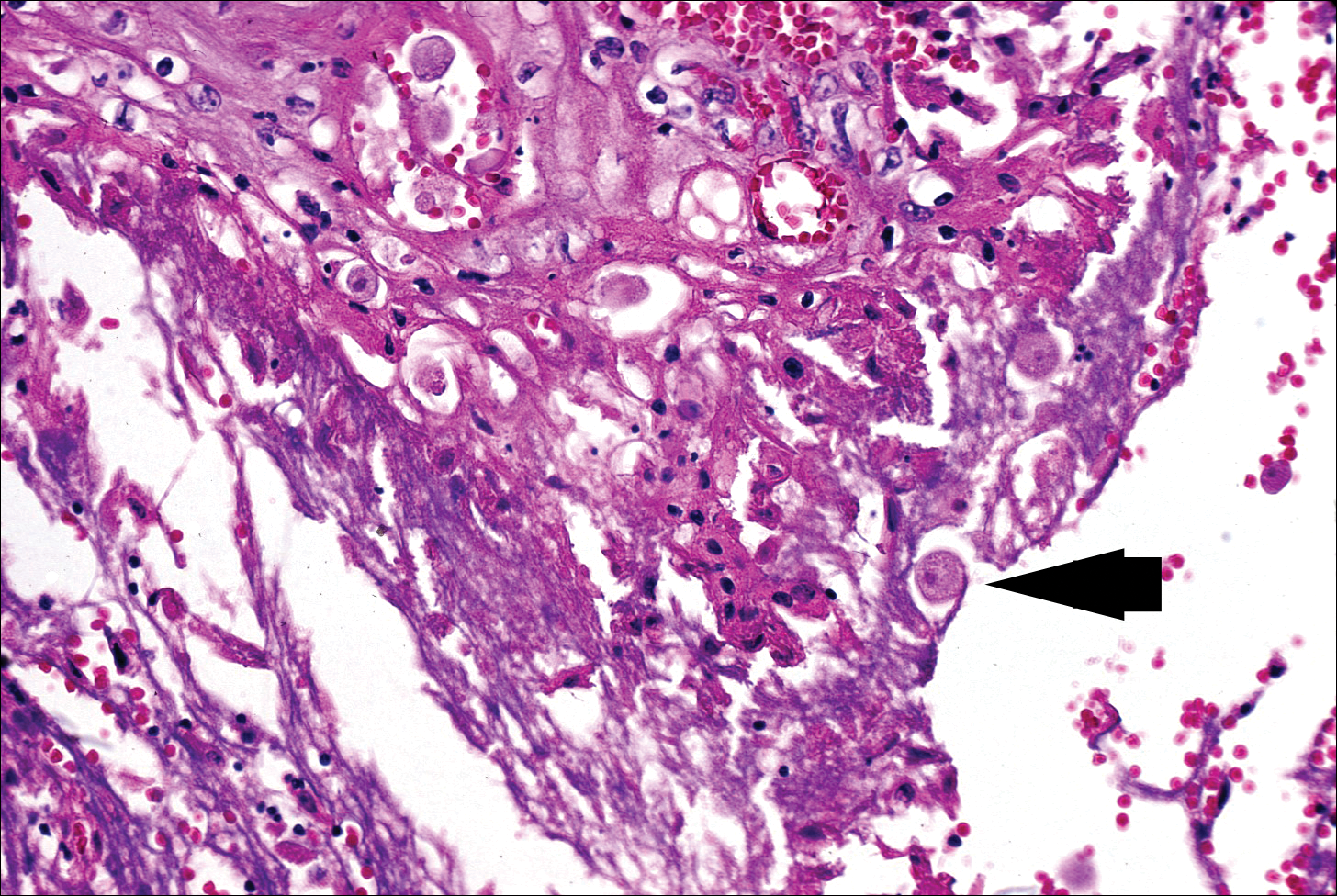

The typical histopathologic pattern of cutaneous amebiasis is ulceration with vascular necrosis (Figure 4).21 The organisms have prominent round nuclei and nucleoli and the cytoplasm may have a scalloped border.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Crohn Disease

Crohn disease (CD), a chronic inflammatory granulomatous disease of the gastrointestinal tract, has a wide spectrum of presentations.1 The condition may affect the vulva, perineum, or perianal skin by direct extension from the gastrointestinal tract or may appear as a separate and distinct cutaneous focus of disease referred to as metastatic Crohn disease (MCD).2

Cutaneous lesions of MCD include ulcers, fissures, sinus tracts, abscesses, and vegetative plaques, which typically extend in continuity with sites of intra-abdominal disease to the perineum, buttocks, or abdominal wall, as well as ostomy sites or incisional scars. Erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum are the most common nonspecific cutaneous manifestations. Other cutaneous lesions described in CD include polyarteritis nodosa, psoriasis, erythema multiforme, erythema elevatum diutinum, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, acne fulminans, pyoderma faciale, neutrophilic lobular panniculitis, granulomatous vasculitis, and porokeratosis.3

Perianal skin is the most common site of cutaneous involvement in individuals with CD. It is a marker of more severe disease and is associated with multiple surgical interventions and frequent relapses and has been reported in 22% of patients with CD.4 Most already had an existing diagnosis of gastrointestinal CD, which was active in one-third of individuals; however, 20% presented with disease at nongastrointestinal sites 2 months to 4 years prior to developing the gastrointestinal CD manifestations.5 Our patient presented with lesions on the perianal skin of 2 years' duration and a 6-month history of diarrhea. A colonoscopy demonstrated shallow ulcers involving the ileocecal portion of the gut, colon, and rectum. A biopsy from intestinal mucosal tissue showed acute and chronic inflammation with necrosis mixed with granulomatous inflammation, suggestive of CD.

Microscopically, the dominant histologic features of MCD are similar to those of bowel lesions, including an inflammatory infiltrate commonly consisting of sterile noncaseating sarcoidal granulomas, foreign body and Langhans giant cells, epithelioid histiocytes, and plasma cells surrounded by numerous mononuclear cells within the dermis with occasional extension into the subcutis (quiz image). Less common features include collagen degeneration, an infiltrate rich in eosinophils, dermal edema, and mixed lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis.6

Metastatic CD often is misdiagnosed. A detailed history and physical examination may help narrow the differential; however, biopsy is necessary to establish a diagnosis of MCD. The histologic differential diagnosis of sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation of genital skin includes sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, leprosy or other mycobacterial and parasitic infection, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and granulomatous infiltrate associated with certain exogenous material (eg, silica, zirconium, beryllium, tattoo pigment).

Sarcoidosis is a multiorgan disease that most frequently affects the lungs, skin, and lymph nodes. Its etiopathogenesis has not been clearly elucidated.7 Cutaneous lesions are present in 20% to 35% of patients.8 Given the wide variability of clinical manifestations, cutaneous sarcoidosis is another one of the great imitators. Cutaneous lesions are classified as specific and nonspecific depending on the presence of noncaseating granulomas on histologic studies and include maculopapules, plaques, nodules, lupus pernio, scar infiltration, alopecia, ulcerative lesions, and hypopigmentation. The most common nonspecific lesion of cutaneous sarcoidosis is erythema nodosum. Other manifestations include calcifications, prurigo, erythema multiforme, nail clubbing, and Sweet syndrome.9

Histologic findings in sarcoidosis generally are independent of the respective organ and clinical disease presentation. The epidermis usually remains unchanged, whereas the dermis shows a superficial and deep nodular granulomatous infiltrate. Granulomas consist of epithelioid cells with only few giant cells and no surrounding lymphocytes or a very sparse lymphocytic infiltrate ("naked" granuloma)(Figure 1). Foreign bodies, including silica, are known to be able to induce sarcoid granulomas, especially in patients with sarcoidosis. A sarcoidal reaction in long-standing scar tissue points to a diagnosis of sarcoidosis.10

Cutaneous tuberculosis primarily is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and less frequently Mycobacterium bovis.11,12 The manifestations of cutaneous tuberculosis depends on various factors such as the type of infection, mode of dissemination, host immunity, and whether it is a first-time infection or a recurrence. In Europe, the head and neck regions are most frequently affected.13 Lesions present as red-brown papules coalescing into a plaque. The tissue, especially in central parts of the lesion, is fragile (probe phenomenon). Diascopy shows the typical apple jelly-like color.

Histologically, cutaneous tuberculosis is characterized by typical tuberculoid granulomas with epithelioid cells and Langhans giant cells at the center surrounded by lymphocytes (Figure 2). Caseous necrosis as well as fibrosis may occur,14,15 and the granulomas tend to coalesce.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis, is a complex, multisystemic disease with varying manifestations. The condition has been defined as a necrotizing granulomatous inflammation usually involving the upper and lower respiratory tracts and necrotizing vasculitis affecting predominantly small- to medium-sized vessels.16 The etiology of GPA is thought to be linked to environmental and infectious triggers inciting onset of disease in genetically predisposed individuals. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies play an important role in the pathogenesis of this disease. Cutaneous vasculitis secondary to GPA can present as papules, nodules, palpable purpura, ulcers resembling pyoderma gangrenosum, or necrotizing lesions leading to gangrene.17

The predominant histopathologic pattern in cutaneous lesions of GPA is leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which is present in up to 50% of biopsies.18 Characteristic findings that aid in establishing the diagnosis include histologic evidence of focal necrosis, fibrinoid degeneration, palisading granuloma surrounding neutrophils (Figure 3), and granulomatous vasculitis involving muscular vessel walls.19 Nonpalisading foci of necrosis or fibrinoid degeneration may precede the development of the typical palisading granuloma.20

The typical histopathologic pattern of cutaneous amebiasis is ulceration with vascular necrosis (Figure 4).21 The organisms have prominent round nuclei and nucleoli and the cytoplasm may have a scalloped border.

- Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD. Landmark article Oct 25, 1932. regional ileitis. a pathologic and clinical entity. by Burril B. Crohn, Leon Gonzburg and Gordon D. Oppenheimer. JAMA. 1984;251:73-79.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn's disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- Weedon D. Miscellaneous conditions. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:554.

- Samitz MH, Dana Jr AS, Rosenberg P. Cutaneous vasculitis in association with Crohn's disease. Cutis. 1970;6:51-56.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Aberumand B, Howard J, Howard J. Metastatic Crohn's disease: an approach to an uncommon but important cutaneous disorder: a review [published online January 3, 2017]. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:8192150.

- Mahony J, Helms SE, Brodell RT. The sarcoidal granuloma: a unifying hypothesis for an enigmatic response. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:654-659.

- Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolf K, et al. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2003.

- Fernandez-Faith E, McDonnell J. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: differential diagnosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:276-287.

- Walsh NM, Hanly JG, Tremaine R, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and foreign bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:203-207.

- Semaan R, Traboulsi R, Kanj S. Primary Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex cutaneous infection: report of two cases and literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:472-477.

- Lai-Cheong JE, Perez A, Tang V, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of tuberculosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:461-466.

- Marcoval J, Servitje O, Moreno A, et al. Lupus vulgaris. clinical, histopathologic, and bacteriologic study of 10 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:404-407.

- Tronnier M, Wolff H. Dermatosen mit granulomatöser Entzündung. Histopathologie der Haut. In: Kerl H, Garbe C, Cerroni L, et al, eds. New York, NY: Springer; 2003.

- Min KW, Ko JY, Park CK. Histopathological spectrum of cutaneous tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:582-595.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1-11.

- Comfere NI, Macaron NC, Gibson LE. Cutaneous manifestations of Wegener's granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 17 patients and correlation to antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody status. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:739-747.

- Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Berti E. Skin involvement in cutaneous and systemic vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:467-476.

- Bramsiepe I, Danz B, Heine R, et al. Primary cutaneous manifestation of Wegener's granulomatosis [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;27:1429-1432.

- Daoud MS, Gibson LE, DeRemee RA, et al. Cutaneous Wegener's granulomatosis: clinical, histopathologic, and immunopathologic features of thirty patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:605-612.

- Guidry JA, Downing C, Tyring SK. Deep fungal infections, blastomycosis-like pyoderma, and granulomatous sexually transmitted infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:595-607.

- Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD. Landmark article Oct 25, 1932. regional ileitis. a pathologic and clinical entity. by Burril B. Crohn, Leon Gonzburg and Gordon D. Oppenheimer. JAMA. 1984;251:73-79.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn's disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- Weedon D. Miscellaneous conditions. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:554.

- Samitz MH, Dana Jr AS, Rosenberg P. Cutaneous vasculitis in association with Crohn's disease. Cutis. 1970;6:51-56.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Aberumand B, Howard J, Howard J. Metastatic Crohn's disease: an approach to an uncommon but important cutaneous disorder: a review [published online January 3, 2017]. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:8192150.

- Mahony J, Helms SE, Brodell RT. The sarcoidal granuloma: a unifying hypothesis for an enigmatic response. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:654-659.

- Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolf K, et al. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2003.

- Fernandez-Faith E, McDonnell J. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: differential diagnosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:276-287.

- Walsh NM, Hanly JG, Tremaine R, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and foreign bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:203-207.

- Semaan R, Traboulsi R, Kanj S. Primary Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex cutaneous infection: report of two cases and literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:472-477.

- Lai-Cheong JE, Perez A, Tang V, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of tuberculosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:461-466.

- Marcoval J, Servitje O, Moreno A, et al. Lupus vulgaris. clinical, histopathologic, and bacteriologic study of 10 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:404-407.

- Tronnier M, Wolff H. Dermatosen mit granulomatöser Entzündung. Histopathologie der Haut. In: Kerl H, Garbe C, Cerroni L, et al, eds. New York, NY: Springer; 2003.

- Min KW, Ko JY, Park CK. Histopathological spectrum of cutaneous tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:582-595.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1-11.

- Comfere NI, Macaron NC, Gibson LE. Cutaneous manifestations of Wegener's granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 17 patients and correlation to antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody status. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:739-747.

- Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Berti E. Skin involvement in cutaneous and systemic vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:467-476.

- Bramsiepe I, Danz B, Heine R, et al. Primary cutaneous manifestation of Wegener's granulomatosis [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;27:1429-1432.

- Daoud MS, Gibson LE, DeRemee RA, et al. Cutaneous Wegener's granulomatosis: clinical, histopathologic, and immunopathologic features of thirty patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:605-612.

- Guidry JA, Downing C, Tyring SK. Deep fungal infections, blastomycosis-like pyoderma, and granulomatous sexually transmitted infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:595-607.

A 19-year-old man presented with a perianal condyloma acuminatum-like plaque of 2 years' duration and a 6-month history of diarrhea.