User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Researchers seek to understand post-COVID autoimmune disease risk

Since the COVID-19 pandemic started more than 3 years ago, the longer-lasting effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection have continued to reveal themselves. Approximately 28% of Americans report having ever experienced post-COVID conditions, such as brain fog, postexertional malaise, and joint pain, and 11% say they are still experiencing these long-term effects. Now, new research is showing that people who have had COVID are more likely to newly develop an autoimmune disease. Exactly why this is happening is less clear, experts say.

Two preprint studies and one study published in a peer-reviewed journal provide strong evidence that patients who have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 are at elevated risk of developing an autoimmune disease. The studies retrospectively reviewed medical records from three countries and compared the incidence of new-onset autoimmune disease among patients who had polymerase chain reaction–confirmed COVID-19 and those who had never been diagnosed with the virus.

A study analyzing the health records of 3.8 million U.S. patients – more than 888,460 with confirmed COVID-19 – found that the COVID-19 group was two to three times as likely to develop various autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and systemic sclerosis. A U.K. preprint study that included more than 458,000 people with confirmed COVID found that those who had previously been infected with SARS-CoV-2 were 22% more likely to develop an autoimmune disease compared with the control group. In this cohort, the diseases most strongly associated with COVID-19 were type 1 diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, and psoriasis. A preprint study from German researchers found that COVID-19 patients were almost 43% more likely to develop an autoimmune disease, compared with those who had never been infected. COVID-19 was most strongly linked to vasculitis.

These large studies are telling us, “Yes, this link is there, so we have to accept it,” Sonia Sharma, PhD, of the Center for Autoimmunity and Inflammation at the La Jolla (Calif.) Institute for Immunology, told this news organization. But this is not the first time that autoimmune diseases have been linked to previous infections.

Researchers have known for decades that Epstein-Barr virus infection is linked to several autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis. More recent research suggests the virus may activate certain genes associated with these immune disorders. Hepatitis C virus can induce cryoglobulinemia, and infection with cytomegalovirus has been implicated in several autoimmune diseases. Bacterial infections have also been linked to autoimmunity, such as group A streptococcus and rheumatic fever, as well as salmonella and reactive arthritis, to name only a few.

“In a way, this isn’t necessarily a new concept to physicians, particularly rheumatologists,” said Jeffrey A. Sparks, MD, a rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “There’s a fine line between appropriately clearing an infection and the body overreacting and setting off a cascade where the immune system is chronically overactive that can manifest as an autoimmune disease,” he told this news organization.

A dysregulated response to infection

It takes the immune system a week or two to develop antigen-specific antibodies to a new pathogen. But for patients with serious infections – in this instance, COVID-19 – that’s time they don’t have. Therefore, the immune system has an alternative pathway, called extrafollicular activation, that creates fast-acting antibodies, explained Matthew Woodruff, PhD, an instructor of immunology and rheumatology at Emory University, Atlanta.

The trade-off is that these antibodies are not as specific and can target the body’s own tissues. This dysregulation of antibody selection is generally short lived and fades when more targeted antibodies are produced and take over, but in some cases, this process can lead to high levels of self-targeting antibodies that can harm the body’s organs and tissues. Research also suggests that for patients who experience long COVID, the same autoantibodies that drive the initial immune response are detectable in the body months after infection, though it is not known whether these lingering immune cells cause these longer-lasting symptoms.

“If you have a virus that causes hyperinflammation plus organ damage, that is a recipe for disaster,” Dr. Sharma said. “It’s a recipe for autoantibodies and autoreactive T cells that down the road can attack the body’s own tissues, especially in people whose immune system is trained in such a way to cause self-reactivity,” she added.

This hyperinflammation can result in rare but serious complications, such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adults, which can occur 2-6 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection. But even in these patients with severe illness, organ-specific complications tend to resolve in 6 months with “no significant sequelae 1 year after diagnosis,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And while long COVID can last for a year or longer, data suggest that symptoms do eventually resolve for most people. What is not clear is why acute autoimmunity triggered by COVID-19 can become a chronic condition in certain patients.

Predisposition to autoimmunity

P. J. Utz, MD, PhD, professor of immunology and rheumatology at Stanford (Calif.) University, said that people who develop autoimmune disease after SARS-CoV-2 infection may have already been predisposed toward autoimmunity. Especially for autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes and lupus, autoantibodies can appear and circulate in the body for more than a decade in some people before they present with any clinical symptoms. “Their immune system is primed such that if they get infected with something – or they have some other environmental trigger that maybe we don’t know about yet – that is enough to then push them over the edge so that they get full-blown autoimmunity,” he said. What is not known is whether these patients’ conditions would have advanced to true clinical disease had they not been infected, he said.

He also noted that the presence of autoantibodies does not necessarily mean someone has autoimmune disease; healthy people can also have autoantibodies, and everyone develops them with age. “My advice would be, ‘Don’t lose sleep over this,’ “ he said.

Dr. Sparks agreed that while these retrospective studies did show an elevated risk of autoimmune disease after COVID-19, that risk appears to be relatively small. “As a practicing rheumatologist, we aren’t seeing a stampede of patients with new-onset rheumatic diseases,” he said. “It’s not like we’re overwhelmed with autoimmune patients, even though almost everyone’s had COVID. So, if there is a risk, it’s very modest.”

Dr. Sparks is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the R. Bruce and Joan M. Mickey Research Scholar Fund, and the Llura Gund Award for Rheumatoid Arthritis Research and Care. Dr. Utz receives research funding from Pfizer. Dr. Sharma and Dr. Woodruff have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic started more than 3 years ago, the longer-lasting effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection have continued to reveal themselves. Approximately 28% of Americans report having ever experienced post-COVID conditions, such as brain fog, postexertional malaise, and joint pain, and 11% say they are still experiencing these long-term effects. Now, new research is showing that people who have had COVID are more likely to newly develop an autoimmune disease. Exactly why this is happening is less clear, experts say.

Two preprint studies and one study published in a peer-reviewed journal provide strong evidence that patients who have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 are at elevated risk of developing an autoimmune disease. The studies retrospectively reviewed medical records from three countries and compared the incidence of new-onset autoimmune disease among patients who had polymerase chain reaction–confirmed COVID-19 and those who had never been diagnosed with the virus.

A study analyzing the health records of 3.8 million U.S. patients – more than 888,460 with confirmed COVID-19 – found that the COVID-19 group was two to three times as likely to develop various autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and systemic sclerosis. A U.K. preprint study that included more than 458,000 people with confirmed COVID found that those who had previously been infected with SARS-CoV-2 were 22% more likely to develop an autoimmune disease compared with the control group. In this cohort, the diseases most strongly associated with COVID-19 were type 1 diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, and psoriasis. A preprint study from German researchers found that COVID-19 patients were almost 43% more likely to develop an autoimmune disease, compared with those who had never been infected. COVID-19 was most strongly linked to vasculitis.

These large studies are telling us, “Yes, this link is there, so we have to accept it,” Sonia Sharma, PhD, of the Center for Autoimmunity and Inflammation at the La Jolla (Calif.) Institute for Immunology, told this news organization. But this is not the first time that autoimmune diseases have been linked to previous infections.

Researchers have known for decades that Epstein-Barr virus infection is linked to several autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis. More recent research suggests the virus may activate certain genes associated with these immune disorders. Hepatitis C virus can induce cryoglobulinemia, and infection with cytomegalovirus has been implicated in several autoimmune diseases. Bacterial infections have also been linked to autoimmunity, such as group A streptococcus and rheumatic fever, as well as salmonella and reactive arthritis, to name only a few.

“In a way, this isn’t necessarily a new concept to physicians, particularly rheumatologists,” said Jeffrey A. Sparks, MD, a rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “There’s a fine line between appropriately clearing an infection and the body overreacting and setting off a cascade where the immune system is chronically overactive that can manifest as an autoimmune disease,” he told this news organization.

A dysregulated response to infection

It takes the immune system a week or two to develop antigen-specific antibodies to a new pathogen. But for patients with serious infections – in this instance, COVID-19 – that’s time they don’t have. Therefore, the immune system has an alternative pathway, called extrafollicular activation, that creates fast-acting antibodies, explained Matthew Woodruff, PhD, an instructor of immunology and rheumatology at Emory University, Atlanta.

The trade-off is that these antibodies are not as specific and can target the body’s own tissues. This dysregulation of antibody selection is generally short lived and fades when more targeted antibodies are produced and take over, but in some cases, this process can lead to high levels of self-targeting antibodies that can harm the body’s organs and tissues. Research also suggests that for patients who experience long COVID, the same autoantibodies that drive the initial immune response are detectable in the body months after infection, though it is not known whether these lingering immune cells cause these longer-lasting symptoms.

“If you have a virus that causes hyperinflammation plus organ damage, that is a recipe for disaster,” Dr. Sharma said. “It’s a recipe for autoantibodies and autoreactive T cells that down the road can attack the body’s own tissues, especially in people whose immune system is trained in such a way to cause self-reactivity,” she added.

This hyperinflammation can result in rare but serious complications, such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adults, which can occur 2-6 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection. But even in these patients with severe illness, organ-specific complications tend to resolve in 6 months with “no significant sequelae 1 year after diagnosis,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And while long COVID can last for a year or longer, data suggest that symptoms do eventually resolve for most people. What is not clear is why acute autoimmunity triggered by COVID-19 can become a chronic condition in certain patients.

Predisposition to autoimmunity

P. J. Utz, MD, PhD, professor of immunology and rheumatology at Stanford (Calif.) University, said that people who develop autoimmune disease after SARS-CoV-2 infection may have already been predisposed toward autoimmunity. Especially for autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes and lupus, autoantibodies can appear and circulate in the body for more than a decade in some people before they present with any clinical symptoms. “Their immune system is primed such that if they get infected with something – or they have some other environmental trigger that maybe we don’t know about yet – that is enough to then push them over the edge so that they get full-blown autoimmunity,” he said. What is not known is whether these patients’ conditions would have advanced to true clinical disease had they not been infected, he said.

He also noted that the presence of autoantibodies does not necessarily mean someone has autoimmune disease; healthy people can also have autoantibodies, and everyone develops them with age. “My advice would be, ‘Don’t lose sleep over this,’ “ he said.

Dr. Sparks agreed that while these retrospective studies did show an elevated risk of autoimmune disease after COVID-19, that risk appears to be relatively small. “As a practicing rheumatologist, we aren’t seeing a stampede of patients with new-onset rheumatic diseases,” he said. “It’s not like we’re overwhelmed with autoimmune patients, even though almost everyone’s had COVID. So, if there is a risk, it’s very modest.”

Dr. Sparks is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the R. Bruce and Joan M. Mickey Research Scholar Fund, and the Llura Gund Award for Rheumatoid Arthritis Research and Care. Dr. Utz receives research funding from Pfizer. Dr. Sharma and Dr. Woodruff have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic started more than 3 years ago, the longer-lasting effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection have continued to reveal themselves. Approximately 28% of Americans report having ever experienced post-COVID conditions, such as brain fog, postexertional malaise, and joint pain, and 11% say they are still experiencing these long-term effects. Now, new research is showing that people who have had COVID are more likely to newly develop an autoimmune disease. Exactly why this is happening is less clear, experts say.

Two preprint studies and one study published in a peer-reviewed journal provide strong evidence that patients who have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 are at elevated risk of developing an autoimmune disease. The studies retrospectively reviewed medical records from three countries and compared the incidence of new-onset autoimmune disease among patients who had polymerase chain reaction–confirmed COVID-19 and those who had never been diagnosed with the virus.

A study analyzing the health records of 3.8 million U.S. patients – more than 888,460 with confirmed COVID-19 – found that the COVID-19 group was two to three times as likely to develop various autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and systemic sclerosis. A U.K. preprint study that included more than 458,000 people with confirmed COVID found that those who had previously been infected with SARS-CoV-2 were 22% more likely to develop an autoimmune disease compared with the control group. In this cohort, the diseases most strongly associated with COVID-19 were type 1 diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, and psoriasis. A preprint study from German researchers found that COVID-19 patients were almost 43% more likely to develop an autoimmune disease, compared with those who had never been infected. COVID-19 was most strongly linked to vasculitis.

These large studies are telling us, “Yes, this link is there, so we have to accept it,” Sonia Sharma, PhD, of the Center for Autoimmunity and Inflammation at the La Jolla (Calif.) Institute for Immunology, told this news organization. But this is not the first time that autoimmune diseases have been linked to previous infections.

Researchers have known for decades that Epstein-Barr virus infection is linked to several autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis. More recent research suggests the virus may activate certain genes associated with these immune disorders. Hepatitis C virus can induce cryoglobulinemia, and infection with cytomegalovirus has been implicated in several autoimmune diseases. Bacterial infections have also been linked to autoimmunity, such as group A streptococcus and rheumatic fever, as well as salmonella and reactive arthritis, to name only a few.

“In a way, this isn’t necessarily a new concept to physicians, particularly rheumatologists,” said Jeffrey A. Sparks, MD, a rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “There’s a fine line between appropriately clearing an infection and the body overreacting and setting off a cascade where the immune system is chronically overactive that can manifest as an autoimmune disease,” he told this news organization.

A dysregulated response to infection

It takes the immune system a week or two to develop antigen-specific antibodies to a new pathogen. But for patients with serious infections – in this instance, COVID-19 – that’s time they don’t have. Therefore, the immune system has an alternative pathway, called extrafollicular activation, that creates fast-acting antibodies, explained Matthew Woodruff, PhD, an instructor of immunology and rheumatology at Emory University, Atlanta.

The trade-off is that these antibodies are not as specific and can target the body’s own tissues. This dysregulation of antibody selection is generally short lived and fades when more targeted antibodies are produced and take over, but in some cases, this process can lead to high levels of self-targeting antibodies that can harm the body’s organs and tissues. Research also suggests that for patients who experience long COVID, the same autoantibodies that drive the initial immune response are detectable in the body months after infection, though it is not known whether these lingering immune cells cause these longer-lasting symptoms.

“If you have a virus that causes hyperinflammation plus organ damage, that is a recipe for disaster,” Dr. Sharma said. “It’s a recipe for autoantibodies and autoreactive T cells that down the road can attack the body’s own tissues, especially in people whose immune system is trained in such a way to cause self-reactivity,” she added.

This hyperinflammation can result in rare but serious complications, such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adults, which can occur 2-6 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection. But even in these patients with severe illness, organ-specific complications tend to resolve in 6 months with “no significant sequelae 1 year after diagnosis,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And while long COVID can last for a year or longer, data suggest that symptoms do eventually resolve for most people. What is not clear is why acute autoimmunity triggered by COVID-19 can become a chronic condition in certain patients.

Predisposition to autoimmunity

P. J. Utz, MD, PhD, professor of immunology and rheumatology at Stanford (Calif.) University, said that people who develop autoimmune disease after SARS-CoV-2 infection may have already been predisposed toward autoimmunity. Especially for autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes and lupus, autoantibodies can appear and circulate in the body for more than a decade in some people before they present with any clinical symptoms. “Their immune system is primed such that if they get infected with something – or they have some other environmental trigger that maybe we don’t know about yet – that is enough to then push them over the edge so that they get full-blown autoimmunity,” he said. What is not known is whether these patients’ conditions would have advanced to true clinical disease had they not been infected, he said.

He also noted that the presence of autoantibodies does not necessarily mean someone has autoimmune disease; healthy people can also have autoantibodies, and everyone develops them with age. “My advice would be, ‘Don’t lose sleep over this,’ “ he said.

Dr. Sparks agreed that while these retrospective studies did show an elevated risk of autoimmune disease after COVID-19, that risk appears to be relatively small. “As a practicing rheumatologist, we aren’t seeing a stampede of patients with new-onset rheumatic diseases,” he said. “It’s not like we’re overwhelmed with autoimmune patients, even though almost everyone’s had COVID. So, if there is a risk, it’s very modest.”

Dr. Sparks is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the R. Bruce and Joan M. Mickey Research Scholar Fund, and the Llura Gund Award for Rheumatoid Arthritis Research and Care. Dr. Utz receives research funding from Pfizer. Dr. Sharma and Dr. Woodruff have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Gut microbiome may guide personalized heart failure therapy

Understanding more about the gut microbiome and how it may affect the development and treatment of heart failure could lead to a more personalized approach to managing the condition, a new review article suggests.

the authors note. “Interactions among the gut microbiome, diet, and medications offer potentially innovative modalities for management of patients with heart failure,” they add.

The review was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“Over the past years we have gathered more understanding about how important the gut microbiome is in relation to how our bodies function overall and even though the cardiovascular system and the heart itself may appear to be quite distant from the gut, we know the gut microbiome affects the cardiovascular system and the physiology of heart failure,” lead author Petra Mamic, MD, Stanford (Calif.) University, told this news organization.

“We’ve also learnt that the microbiome is very personalized. It seems to be affected by a lot of intrinsic and as well as extrinsic factors. For cardiovascular diseases in particular, we always knew that diet and lifestyle were part of the environmental risk, and we now believe that the gut microbiome may be one of the factors that mediates that risk,” she said.

“Studies on the gut microbiome are difficult to do and we are right at the beginning of this type of research. But we have learned that the microbiome is altered or dysregulated in many diseases including many cardiovascular diseases, and many of the changes in the microbiome we see in different cardiovascular diseases seem to overlap,” she added.

Dr. Mamic explained that patients with heart failure have a microbiome that appears different and dysregulated, compared with the microbiome in healthy individuals.

“The difficulty is teasing out whether the microbiome changes are causing heart failure or if they are a consequence of the heart failure and all the medications and comorbidities associated with heart failure,” she commented.

Animal studies have shown that many microbial products, small molecules made by the microbiome, seem to affect how the heart recovers from injury, for example after a myocardial infarction, and how much the heart scars and hypertrophies after an injury, Dr. Mamic reported. These microbiome-derived small molecules can also affect blood pressure, which is dysregulated in heart failure.

Other products of the microbiome can be pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory, which can again affect the cardiovascular physiology and the heart, she noted.

High-fiber diet may be beneficial

One area of particular interest at present involves the role of short-chain fatty acids, which are a byproduct of microbes in the gut that digest fiber.

“These short chain fatty acids seem to have positive effects on the host physiology. They are anti-inflammatory; they lower blood pressure; and they seem to protect the heart from scarring and hypertrophy after injury. In heart failure, the gut microbes that make these short-chain fatty acids are significantly depleted,” Dr. Mamic explained.

They are an obvious focus of interest because these short-chain fatty acids are produced when gut bacteria break down dietary fiber, raising the possibility of beneficial effects from eating a high-fiber diet.

Another product of the gut microbiome of interest is trimethylamine N-oxide, formed when gut bacteria break down nutrients such as L-carnitine and phosphatidyl choline, nutrients abundant in foods of animal origin, especially red meat. This metabolite has proatherogenic and prothrombotic effects, and negatively affected cardiac remodeling in a mouse heart failure model, the review notes.

However, though it is too early to make specific dietary recommendations based on these findings, Dr. Mamic points out that a high-fiber diet is thought to be beneficial.

“Nutritional research is very hard to do and the data is limited, but as best as we can summarize things, we know that plant-based diets such as the Mediterranean and DASH diets seem to prevent some of the risk factors for the development of heart failure and seem to slow the progression of heart failure,” she added.

One of the major recommendations in these diets is a high intake of fiber, including whole foods, vegetables, fruits, legumes, and nuts, and less intake of processed food and red meat. “In general, I think everyone should eat like that, but I specifically recommend a plant-based diet with a high amount of fiber to my heart failure patients,” Dr. Mamic said.

Large variation in microbiome composition

The review also explores the idea of personalization of diet or specific treatments dependent on an individual’s gut microbiome composition.

Dr. Mamic explains: “When we look at the microbiome composition between individuals, it is very different. There is very little overlap between individuals, even in people who are related. It seems to be more to do with the environment – people who are living together are more likely to have similarities in their microbiome. We are still trying to understand what drives these differences.”

It is thought that these differences may affect the response to a specific diet or medication. Dr. Mamic gives the example of fiber. “Not all bacteria can digest the same types of fiber, so not everyone responds in the same way to a high-fiber diet. That’s probably because of differences in their microbiome.”

Another example is the response to the heart failure drug digoxin, which is metabolized by one particular strain of bacteria in the gut. The toxicity or effectiveness of digoxin seems to be influenced by levels of this bacterial strain, and this again can be influenced by diet, Dr. Mamic says.

Manipulating the microbiome as a therapeutic strategy

Microbiome-targeting therapies may also become part of future treatment strategies for many conditions, including heart failure, the review authors say.

Probiotics (foods and dietary supplements that contain live microbes) interact with the gut microbiota to alter host physiology beneficially. Certain probiotics may specifically modulate processes dysregulated in heart failure, as was suggested in a rodent heart failure model in which supplementation with Lactobacillus-containing and Bifidobacterium-containing probiotics resulted in markedly improved cardiac function, the authors report.

However, a randomized trial (GutHeart) of probiotic yeast Saccharomyces boulardii in patients with heart failure found no improvement in cardiac function, compared with standard care.

Commenting on this, Dr. Mamic suggested that a more specific approach may be needed.

“Some of our preliminary data have shown people who have heart failure have severely depleted Bifidobacteria,” Dr. Mamic said. These bacteria are commercially available as a probiotic, and the researchers are planning a study to give patients with heart failure these specific probiotics. “We are trying to find practical ways forward and to be guided by the data. These people have very little Bifidobacteria, and we know that probiotics seem to be accepted best by the host where there is a specific need for them, so this seems like a sensible approach.”

Dr. Mamic does not recommend that heart failure patients take general probiotic products at present, but she tells her patients about the study she is doing. “Probiotics are quite different from each other. It is a very unregulated market. A general probiotic product may not contain the specific bacteria needed.”

Include microbiome data in biobanks

The review calls for more research on the subject and a more systematic approach to collecting data on the microbiome.

“At present for medical research, blood samples are collected, stored, and analyzed routinely. I think we should also be collecting stool samples in the same way to analyze the microbiome,” Dr. Mamic suggests.

“If we can combine that with data from blood tests on various metabolites/cytokines and look at how the microbiome changes over time or with medication, or with diet, and how the host responds including clinically relevant data, that would be really important. Given how quickly the field is growing I would think there would be biobanks including the microbiome in a few years’ time.”

“We need to gather this data. We would be looking for which bacteria are there, what their functionality is, how it changes over time, with diet or medication, and even whether we can use the microbiome data to predict who will respond to a specific drug.”

Dr. Mamic believes that in the future, analysis of the microbiome could be a routine part of deciding what people eat for good health and to characterize patients for personalized therapies.

“It is clear that the microbiome can influence health, and a dysregulated microbiome negatively affects the host, but there is lot of work to do. We need to learn a lot more about it, but we shouldn’t miss the opportunity to do this,” she concluded.

Dr. Mamic reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Understanding more about the gut microbiome and how it may affect the development and treatment of heart failure could lead to a more personalized approach to managing the condition, a new review article suggests.

the authors note. “Interactions among the gut microbiome, diet, and medications offer potentially innovative modalities for management of patients with heart failure,” they add.

The review was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“Over the past years we have gathered more understanding about how important the gut microbiome is in relation to how our bodies function overall and even though the cardiovascular system and the heart itself may appear to be quite distant from the gut, we know the gut microbiome affects the cardiovascular system and the physiology of heart failure,” lead author Petra Mamic, MD, Stanford (Calif.) University, told this news organization.

“We’ve also learnt that the microbiome is very personalized. It seems to be affected by a lot of intrinsic and as well as extrinsic factors. For cardiovascular diseases in particular, we always knew that diet and lifestyle were part of the environmental risk, and we now believe that the gut microbiome may be one of the factors that mediates that risk,” she said.

“Studies on the gut microbiome are difficult to do and we are right at the beginning of this type of research. But we have learned that the microbiome is altered or dysregulated in many diseases including many cardiovascular diseases, and many of the changes in the microbiome we see in different cardiovascular diseases seem to overlap,” she added.

Dr. Mamic explained that patients with heart failure have a microbiome that appears different and dysregulated, compared with the microbiome in healthy individuals.

“The difficulty is teasing out whether the microbiome changes are causing heart failure or if they are a consequence of the heart failure and all the medications and comorbidities associated with heart failure,” she commented.

Animal studies have shown that many microbial products, small molecules made by the microbiome, seem to affect how the heart recovers from injury, for example after a myocardial infarction, and how much the heart scars and hypertrophies after an injury, Dr. Mamic reported. These microbiome-derived small molecules can also affect blood pressure, which is dysregulated in heart failure.

Other products of the microbiome can be pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory, which can again affect the cardiovascular physiology and the heart, she noted.

High-fiber diet may be beneficial

One area of particular interest at present involves the role of short-chain fatty acids, which are a byproduct of microbes in the gut that digest fiber.

“These short chain fatty acids seem to have positive effects on the host physiology. They are anti-inflammatory; they lower blood pressure; and they seem to protect the heart from scarring and hypertrophy after injury. In heart failure, the gut microbes that make these short-chain fatty acids are significantly depleted,” Dr. Mamic explained.

They are an obvious focus of interest because these short-chain fatty acids are produced when gut bacteria break down dietary fiber, raising the possibility of beneficial effects from eating a high-fiber diet.

Another product of the gut microbiome of interest is trimethylamine N-oxide, formed when gut bacteria break down nutrients such as L-carnitine and phosphatidyl choline, nutrients abundant in foods of animal origin, especially red meat. This metabolite has proatherogenic and prothrombotic effects, and negatively affected cardiac remodeling in a mouse heart failure model, the review notes.

However, though it is too early to make specific dietary recommendations based on these findings, Dr. Mamic points out that a high-fiber diet is thought to be beneficial.

“Nutritional research is very hard to do and the data is limited, but as best as we can summarize things, we know that plant-based diets such as the Mediterranean and DASH diets seem to prevent some of the risk factors for the development of heart failure and seem to slow the progression of heart failure,” she added.

One of the major recommendations in these diets is a high intake of fiber, including whole foods, vegetables, fruits, legumes, and nuts, and less intake of processed food and red meat. “In general, I think everyone should eat like that, but I specifically recommend a plant-based diet with a high amount of fiber to my heart failure patients,” Dr. Mamic said.

Large variation in microbiome composition

The review also explores the idea of personalization of diet or specific treatments dependent on an individual’s gut microbiome composition.

Dr. Mamic explains: “When we look at the microbiome composition between individuals, it is very different. There is very little overlap between individuals, even in people who are related. It seems to be more to do with the environment – people who are living together are more likely to have similarities in their microbiome. We are still trying to understand what drives these differences.”

It is thought that these differences may affect the response to a specific diet or medication. Dr. Mamic gives the example of fiber. “Not all bacteria can digest the same types of fiber, so not everyone responds in the same way to a high-fiber diet. That’s probably because of differences in their microbiome.”

Another example is the response to the heart failure drug digoxin, which is metabolized by one particular strain of bacteria in the gut. The toxicity or effectiveness of digoxin seems to be influenced by levels of this bacterial strain, and this again can be influenced by diet, Dr. Mamic says.

Manipulating the microbiome as a therapeutic strategy

Microbiome-targeting therapies may also become part of future treatment strategies for many conditions, including heart failure, the review authors say.

Probiotics (foods and dietary supplements that contain live microbes) interact with the gut microbiota to alter host physiology beneficially. Certain probiotics may specifically modulate processes dysregulated in heart failure, as was suggested in a rodent heart failure model in which supplementation with Lactobacillus-containing and Bifidobacterium-containing probiotics resulted in markedly improved cardiac function, the authors report.

However, a randomized trial (GutHeart) of probiotic yeast Saccharomyces boulardii in patients with heart failure found no improvement in cardiac function, compared with standard care.

Commenting on this, Dr. Mamic suggested that a more specific approach may be needed.

“Some of our preliminary data have shown people who have heart failure have severely depleted Bifidobacteria,” Dr. Mamic said. These bacteria are commercially available as a probiotic, and the researchers are planning a study to give patients with heart failure these specific probiotics. “We are trying to find practical ways forward and to be guided by the data. These people have very little Bifidobacteria, and we know that probiotics seem to be accepted best by the host where there is a specific need for them, so this seems like a sensible approach.”

Dr. Mamic does not recommend that heart failure patients take general probiotic products at present, but she tells her patients about the study she is doing. “Probiotics are quite different from each other. It is a very unregulated market. A general probiotic product may not contain the specific bacteria needed.”

Include microbiome data in biobanks

The review calls for more research on the subject and a more systematic approach to collecting data on the microbiome.

“At present for medical research, blood samples are collected, stored, and analyzed routinely. I think we should also be collecting stool samples in the same way to analyze the microbiome,” Dr. Mamic suggests.

“If we can combine that with data from blood tests on various metabolites/cytokines and look at how the microbiome changes over time or with medication, or with diet, and how the host responds including clinically relevant data, that would be really important. Given how quickly the field is growing I would think there would be biobanks including the microbiome in a few years’ time.”

“We need to gather this data. We would be looking for which bacteria are there, what their functionality is, how it changes over time, with diet or medication, and even whether we can use the microbiome data to predict who will respond to a specific drug.”

Dr. Mamic believes that in the future, analysis of the microbiome could be a routine part of deciding what people eat for good health and to characterize patients for personalized therapies.

“It is clear that the microbiome can influence health, and a dysregulated microbiome negatively affects the host, but there is lot of work to do. We need to learn a lot more about it, but we shouldn’t miss the opportunity to do this,” she concluded.

Dr. Mamic reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Understanding more about the gut microbiome and how it may affect the development and treatment of heart failure could lead to a more personalized approach to managing the condition, a new review article suggests.

the authors note. “Interactions among the gut microbiome, diet, and medications offer potentially innovative modalities for management of patients with heart failure,” they add.

The review was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“Over the past years we have gathered more understanding about how important the gut microbiome is in relation to how our bodies function overall and even though the cardiovascular system and the heart itself may appear to be quite distant from the gut, we know the gut microbiome affects the cardiovascular system and the physiology of heart failure,” lead author Petra Mamic, MD, Stanford (Calif.) University, told this news organization.

“We’ve also learnt that the microbiome is very personalized. It seems to be affected by a lot of intrinsic and as well as extrinsic factors. For cardiovascular diseases in particular, we always knew that diet and lifestyle were part of the environmental risk, and we now believe that the gut microbiome may be one of the factors that mediates that risk,” she said.

“Studies on the gut microbiome are difficult to do and we are right at the beginning of this type of research. But we have learned that the microbiome is altered or dysregulated in many diseases including many cardiovascular diseases, and many of the changes in the microbiome we see in different cardiovascular diseases seem to overlap,” she added.

Dr. Mamic explained that patients with heart failure have a microbiome that appears different and dysregulated, compared with the microbiome in healthy individuals.

“The difficulty is teasing out whether the microbiome changes are causing heart failure or if they are a consequence of the heart failure and all the medications and comorbidities associated with heart failure,” she commented.

Animal studies have shown that many microbial products, small molecules made by the microbiome, seem to affect how the heart recovers from injury, for example after a myocardial infarction, and how much the heart scars and hypertrophies after an injury, Dr. Mamic reported. These microbiome-derived small molecules can also affect blood pressure, which is dysregulated in heart failure.

Other products of the microbiome can be pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory, which can again affect the cardiovascular physiology and the heart, she noted.

High-fiber diet may be beneficial

One area of particular interest at present involves the role of short-chain fatty acids, which are a byproduct of microbes in the gut that digest fiber.

“These short chain fatty acids seem to have positive effects on the host physiology. They are anti-inflammatory; they lower blood pressure; and they seem to protect the heart from scarring and hypertrophy after injury. In heart failure, the gut microbes that make these short-chain fatty acids are significantly depleted,” Dr. Mamic explained.

They are an obvious focus of interest because these short-chain fatty acids are produced when gut bacteria break down dietary fiber, raising the possibility of beneficial effects from eating a high-fiber diet.

Another product of the gut microbiome of interest is trimethylamine N-oxide, formed when gut bacteria break down nutrients such as L-carnitine and phosphatidyl choline, nutrients abundant in foods of animal origin, especially red meat. This metabolite has proatherogenic and prothrombotic effects, and negatively affected cardiac remodeling in a mouse heart failure model, the review notes.

However, though it is too early to make specific dietary recommendations based on these findings, Dr. Mamic points out that a high-fiber diet is thought to be beneficial.

“Nutritional research is very hard to do and the data is limited, but as best as we can summarize things, we know that plant-based diets such as the Mediterranean and DASH diets seem to prevent some of the risk factors for the development of heart failure and seem to slow the progression of heart failure,” she added.

One of the major recommendations in these diets is a high intake of fiber, including whole foods, vegetables, fruits, legumes, and nuts, and less intake of processed food and red meat. “In general, I think everyone should eat like that, but I specifically recommend a plant-based diet with a high amount of fiber to my heart failure patients,” Dr. Mamic said.

Large variation in microbiome composition

The review also explores the idea of personalization of diet or specific treatments dependent on an individual’s gut microbiome composition.

Dr. Mamic explains: “When we look at the microbiome composition between individuals, it is very different. There is very little overlap between individuals, even in people who are related. It seems to be more to do with the environment – people who are living together are more likely to have similarities in their microbiome. We are still trying to understand what drives these differences.”

It is thought that these differences may affect the response to a specific diet or medication. Dr. Mamic gives the example of fiber. “Not all bacteria can digest the same types of fiber, so not everyone responds in the same way to a high-fiber diet. That’s probably because of differences in their microbiome.”

Another example is the response to the heart failure drug digoxin, which is metabolized by one particular strain of bacteria in the gut. The toxicity or effectiveness of digoxin seems to be influenced by levels of this bacterial strain, and this again can be influenced by diet, Dr. Mamic says.

Manipulating the microbiome as a therapeutic strategy

Microbiome-targeting therapies may also become part of future treatment strategies for many conditions, including heart failure, the review authors say.

Probiotics (foods and dietary supplements that contain live microbes) interact with the gut microbiota to alter host physiology beneficially. Certain probiotics may specifically modulate processes dysregulated in heart failure, as was suggested in a rodent heart failure model in which supplementation with Lactobacillus-containing and Bifidobacterium-containing probiotics resulted in markedly improved cardiac function, the authors report.

However, a randomized trial (GutHeart) of probiotic yeast Saccharomyces boulardii in patients with heart failure found no improvement in cardiac function, compared with standard care.

Commenting on this, Dr. Mamic suggested that a more specific approach may be needed.

“Some of our preliminary data have shown people who have heart failure have severely depleted Bifidobacteria,” Dr. Mamic said. These bacteria are commercially available as a probiotic, and the researchers are planning a study to give patients with heart failure these specific probiotics. “We are trying to find practical ways forward and to be guided by the data. These people have very little Bifidobacteria, and we know that probiotics seem to be accepted best by the host where there is a specific need for them, so this seems like a sensible approach.”

Dr. Mamic does not recommend that heart failure patients take general probiotic products at present, but she tells her patients about the study she is doing. “Probiotics are quite different from each other. It is a very unregulated market. A general probiotic product may not contain the specific bacteria needed.”

Include microbiome data in biobanks

The review calls for more research on the subject and a more systematic approach to collecting data on the microbiome.

“At present for medical research, blood samples are collected, stored, and analyzed routinely. I think we should also be collecting stool samples in the same way to analyze the microbiome,” Dr. Mamic suggests.

“If we can combine that with data from blood tests on various metabolites/cytokines and look at how the microbiome changes over time or with medication, or with diet, and how the host responds including clinically relevant data, that would be really important. Given how quickly the field is growing I would think there would be biobanks including the microbiome in a few years’ time.”

“We need to gather this data. We would be looking for which bacteria are there, what their functionality is, how it changes over time, with diet or medication, and even whether we can use the microbiome data to predict who will respond to a specific drug.”

Dr. Mamic believes that in the future, analysis of the microbiome could be a routine part of deciding what people eat for good health and to characterize patients for personalized therapies.

“It is clear that the microbiome can influence health, and a dysregulated microbiome negatively affects the host, but there is lot of work to do. We need to learn a lot more about it, but we shouldn’t miss the opportunity to do this,” she concluded.

Dr. Mamic reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

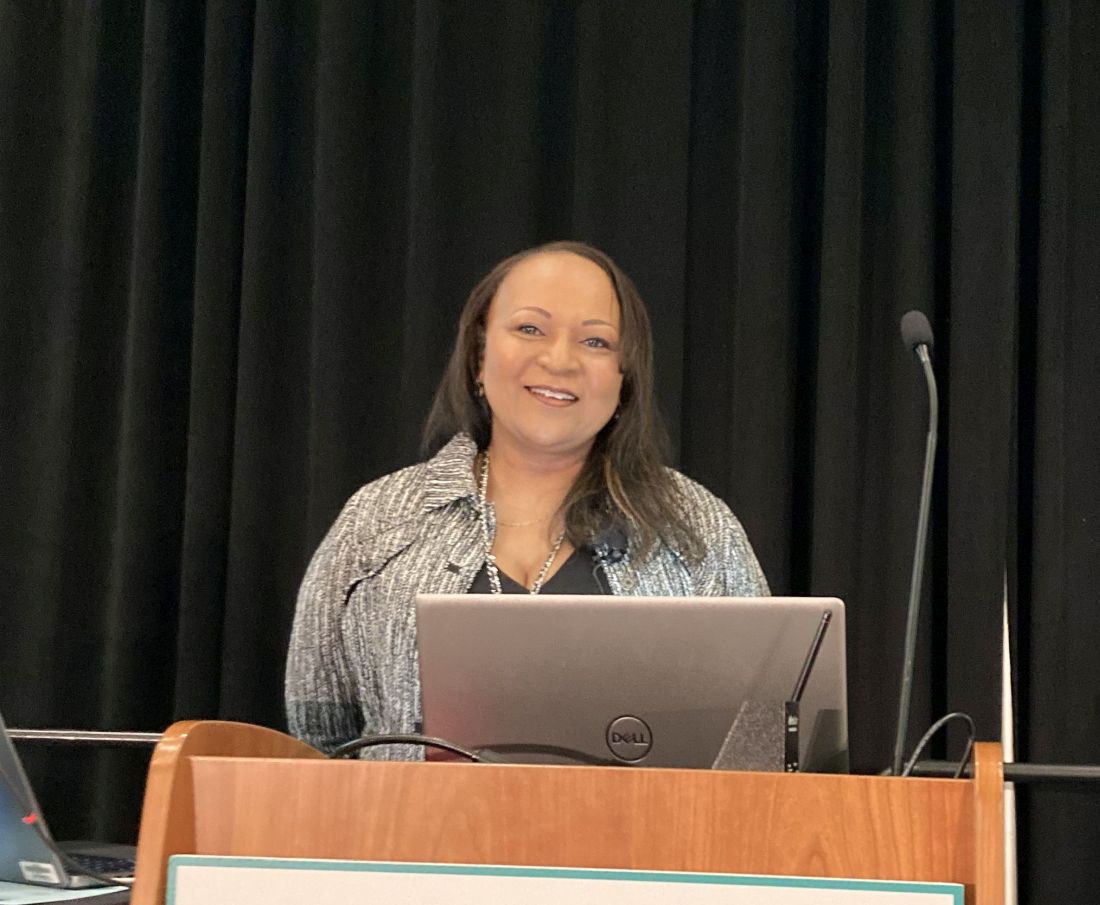

New blood pressure thresholds: How do they affect the evaluation and treatment of hypertension?

In a major shift in the definition of hypertension, guidelines published in 2017 reclassified 130/80 mm Hg as high blood pressure, or stage 1 hypertension. Previous guidelines classified 130/80 mm Hg as elevated, and 140/90 mm Hg used to be the threshold for stage 1 hypertension.

“This shift in classification criteria may cause confusion among clinicians caring for patients with hypertension and has a significant impact on how we diagnose and manage hypertension in our practice,” said Shawna D. Nesbitt, MD, professor of internal medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and medical director at Parkland Hypertension Clinic in Dallas. Dr. Nesbitt is an expert in the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension, particularly complex and refractory cases.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in the United States, accounting for nearly one-quarter of all deaths in men and in women. Hypertension is a key factor contributing to CVD. The hypertension‐related CVD mortality is currently on the rise in many U.S. demographic groups, including younger individuals (35-64 years old), she said.

When asked about the potential causes of this trend, Dr. Nesbitt explained that the epidemics of obesity and overweight are critical contributors to the high prevalence of hypertension.

The new definition means a wider gap in the prevalence of hypertension between men and women, as well as between Black and White people in the United States. The U.S. rates of hypertension and hypertension‐related CVD mortality are much higher in Black than in White people in this country. Hypertension control rates are the lowest in Black, Hispanic, and Asian males, Dr. Nesbitt said.

Accurate measurement of blood pressure is crucial

The changes in classification criteria for hypertension have made accurate measurements of blood pressure important. A key challenge in the evaluation of hypertension in the clinic is the difference in the methods used to measure blood pressure between trials and real-world clinical practice.

“We can’t easily translate data collected in clinical trials into real-life scenarios, and this can have important implications in our expectations of treatment outcome,” Dr. Nesbitt cautioned.

Commenting on the best practices in blood pressure measurements in the office, Dr. Nesbitt said that patients need to be seated with their feet on the floor and their backs and arms supported. In addition, patients need to have at least 5 minutes of rest without talking.

“It is very important to help patients understand what triggers their blood pressure to be elevated and teach them how and when to measure their blood pressure at home using their own devices,” she added.

Another critical question is how to translate the new guidelines into changes in clinical care, she said.

Current treatment landscape of hypertension

Ensuring a healthy diet, weight, and sleep, participating in physical activity, avoiding nicotine, and managing blood pressure, cholesterol, and sugar levels are the new “Life’s Essential 8” strategies proposed by the American Heart Association (AHA) to reduce CVD risk.

“Sleep has recently been added to the AHA guidelines because it modulates many factors contributing to hypertension,” Dr. Nesbitt pointed out. She advised that clinicians should ask patients about their sleep and educate them on healthy sleeping habits.

Some of the evidence used to develop the new AHA guidelines is derived from the SPRINT trial, which showed that controlling blood pressure reduces the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events. “This is our ultimate goal for our patients with hypertension,” Dr. Nesbitt noted.

Regarding the best practice in hypertension management, Dr. Nesbitt explained that with the new blood pressure thresholds, more patients will be diagnosed with stage 1 hypertension and need the nonpharmacological therapy suggested by the AHA. But patients with stage 1 hypertension and with a high CVD risk (at least 10%) also should receive blood pressure-lowering medications, so an accurate assessment of the risk of clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or the estimated 10-year CVD risk is crucial. “If we are not careful, we might miss some patients who need to be treated,” she said.

Calcium channel blockers, thiazide diuretics, and ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are the treatment of choice for patients with newly diagnosed hypertension. Although extensively used in the past, beta-blockers are no longer a first-line treatment for hypertension.

When asked why beta-blockers are no longer suitable for routine initial treatment of hypertension, Dr. Nesbitt said that they are effective in controlling palpitations but “other antihypertensive drugs have proven far better in controlling blood pressure.”

Hypertension is multifactorial and often occurs in combination with other conditions, including diabetes and chronic kidney disease. When developing a treatment plan for patients with hypertension, comorbidities need to be considered, because their management may also help control blood pressure, especially for conditions that may contribute to the development of hypertension.

Common conditions that contribute to and often coexist with hypertension include sleep apnea, obesity, anxiety, and depression. However, convincing people to seek mental health support can be very challenging, Dr. Nesbitt said.

She added that hypertension is a complex disease with a strong social component. Understanding its pathophysiology and social determinants is paramount for successfully managing hypertension at the individual level, as well as at the community level.

Identification and management of side effects is key

Dr. Nesbitt also discussed the importance of the identification and management of side effects associated with blood pressure-lowering drugs. She cautioned that, if not managed, side effects can lead to treatment nonadherence and pseudo‐resistance, both of which can jeopardize the successful management of hypertension.

When asked about her approach to managing side effects and convincing patients to continue taking their medications, Dr. Nesbitt noted that “setting realistic expectations and goals is key.”

In an interview after Dr. Nesbitt’s presentation, Jesica Naanous, MD, agreed that having an honest conversation with the patients is the best way to convince them to keep taking their medications. She also explains to patients that the complications of uncontrolled blood pressure are worse than the side effects of the drugs.

“As a last resort, I change a blood pressure-lowering agent to another,” added Dr. Naanous, an internist at the American British Cowdray (ABC) Medical Center in Mexico City. She explained that many antihypertensive drugs have different toxicity profiles, and simply changing to another agent can make treatment more tolerable for the patient.

Dr. Nesbitt reported no relationships with entities whose primary business is producing, marketing, selling, reselling, or distributing health care products used by or on patients.

In a major shift in the definition of hypertension, guidelines published in 2017 reclassified 130/80 mm Hg as high blood pressure, or stage 1 hypertension. Previous guidelines classified 130/80 mm Hg as elevated, and 140/90 mm Hg used to be the threshold for stage 1 hypertension.

“This shift in classification criteria may cause confusion among clinicians caring for patients with hypertension and has a significant impact on how we diagnose and manage hypertension in our practice,” said Shawna D. Nesbitt, MD, professor of internal medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and medical director at Parkland Hypertension Clinic in Dallas. Dr. Nesbitt is an expert in the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension, particularly complex and refractory cases.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in the United States, accounting for nearly one-quarter of all deaths in men and in women. Hypertension is a key factor contributing to CVD. The hypertension‐related CVD mortality is currently on the rise in many U.S. demographic groups, including younger individuals (35-64 years old), she said.

When asked about the potential causes of this trend, Dr. Nesbitt explained that the epidemics of obesity and overweight are critical contributors to the high prevalence of hypertension.

The new definition means a wider gap in the prevalence of hypertension between men and women, as well as between Black and White people in the United States. The U.S. rates of hypertension and hypertension‐related CVD mortality are much higher in Black than in White people in this country. Hypertension control rates are the lowest in Black, Hispanic, and Asian males, Dr. Nesbitt said.

Accurate measurement of blood pressure is crucial

The changes in classification criteria for hypertension have made accurate measurements of blood pressure important. A key challenge in the evaluation of hypertension in the clinic is the difference in the methods used to measure blood pressure between trials and real-world clinical practice.

“We can’t easily translate data collected in clinical trials into real-life scenarios, and this can have important implications in our expectations of treatment outcome,” Dr. Nesbitt cautioned.

Commenting on the best practices in blood pressure measurements in the office, Dr. Nesbitt said that patients need to be seated with their feet on the floor and their backs and arms supported. In addition, patients need to have at least 5 minutes of rest without talking.

“It is very important to help patients understand what triggers their blood pressure to be elevated and teach them how and when to measure their blood pressure at home using their own devices,” she added.

Another critical question is how to translate the new guidelines into changes in clinical care, she said.

Current treatment landscape of hypertension

Ensuring a healthy diet, weight, and sleep, participating in physical activity, avoiding nicotine, and managing blood pressure, cholesterol, and sugar levels are the new “Life’s Essential 8” strategies proposed by the American Heart Association (AHA) to reduce CVD risk.

“Sleep has recently been added to the AHA guidelines because it modulates many factors contributing to hypertension,” Dr. Nesbitt pointed out. She advised that clinicians should ask patients about their sleep and educate them on healthy sleeping habits.

Some of the evidence used to develop the new AHA guidelines is derived from the SPRINT trial, which showed that controlling blood pressure reduces the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events. “This is our ultimate goal for our patients with hypertension,” Dr. Nesbitt noted.

Regarding the best practice in hypertension management, Dr. Nesbitt explained that with the new blood pressure thresholds, more patients will be diagnosed with stage 1 hypertension and need the nonpharmacological therapy suggested by the AHA. But patients with stage 1 hypertension and with a high CVD risk (at least 10%) also should receive blood pressure-lowering medications, so an accurate assessment of the risk of clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or the estimated 10-year CVD risk is crucial. “If we are not careful, we might miss some patients who need to be treated,” she said.

Calcium channel blockers, thiazide diuretics, and ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are the treatment of choice for patients with newly diagnosed hypertension. Although extensively used in the past, beta-blockers are no longer a first-line treatment for hypertension.

When asked why beta-blockers are no longer suitable for routine initial treatment of hypertension, Dr. Nesbitt said that they are effective in controlling palpitations but “other antihypertensive drugs have proven far better in controlling blood pressure.”

Hypertension is multifactorial and often occurs in combination with other conditions, including diabetes and chronic kidney disease. When developing a treatment plan for patients with hypertension, comorbidities need to be considered, because their management may also help control blood pressure, especially for conditions that may contribute to the development of hypertension.

Common conditions that contribute to and often coexist with hypertension include sleep apnea, obesity, anxiety, and depression. However, convincing people to seek mental health support can be very challenging, Dr. Nesbitt said.

She added that hypertension is a complex disease with a strong social component. Understanding its pathophysiology and social determinants is paramount for successfully managing hypertension at the individual level, as well as at the community level.

Identification and management of side effects is key

Dr. Nesbitt also discussed the importance of the identification and management of side effects associated with blood pressure-lowering drugs. She cautioned that, if not managed, side effects can lead to treatment nonadherence and pseudo‐resistance, both of which can jeopardize the successful management of hypertension.

When asked about her approach to managing side effects and convincing patients to continue taking their medications, Dr. Nesbitt noted that “setting realistic expectations and goals is key.”

In an interview after Dr. Nesbitt’s presentation, Jesica Naanous, MD, agreed that having an honest conversation with the patients is the best way to convince them to keep taking their medications. She also explains to patients that the complications of uncontrolled blood pressure are worse than the side effects of the drugs.

“As a last resort, I change a blood pressure-lowering agent to another,” added Dr. Naanous, an internist at the American British Cowdray (ABC) Medical Center in Mexico City. She explained that many antihypertensive drugs have different toxicity profiles, and simply changing to another agent can make treatment more tolerable for the patient.

Dr. Nesbitt reported no relationships with entities whose primary business is producing, marketing, selling, reselling, or distributing health care products used by or on patients.

In a major shift in the definition of hypertension, guidelines published in 2017 reclassified 130/80 mm Hg as high blood pressure, or stage 1 hypertension. Previous guidelines classified 130/80 mm Hg as elevated, and 140/90 mm Hg used to be the threshold for stage 1 hypertension.

“This shift in classification criteria may cause confusion among clinicians caring for patients with hypertension and has a significant impact on how we diagnose and manage hypertension in our practice,” said Shawna D. Nesbitt, MD, professor of internal medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and medical director at Parkland Hypertension Clinic in Dallas. Dr. Nesbitt is an expert in the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension, particularly complex and refractory cases.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in the United States, accounting for nearly one-quarter of all deaths in men and in women. Hypertension is a key factor contributing to CVD. The hypertension‐related CVD mortality is currently on the rise in many U.S. demographic groups, including younger individuals (35-64 years old), she said.

When asked about the potential causes of this trend, Dr. Nesbitt explained that the epidemics of obesity and overweight are critical contributors to the high prevalence of hypertension.

The new definition means a wider gap in the prevalence of hypertension between men and women, as well as between Black and White people in the United States. The U.S. rates of hypertension and hypertension‐related CVD mortality are much higher in Black than in White people in this country. Hypertension control rates are the lowest in Black, Hispanic, and Asian males, Dr. Nesbitt said.

Accurate measurement of blood pressure is crucial

The changes in classification criteria for hypertension have made accurate measurements of blood pressure important. A key challenge in the evaluation of hypertension in the clinic is the difference in the methods used to measure blood pressure between trials and real-world clinical practice.

“We can’t easily translate data collected in clinical trials into real-life scenarios, and this can have important implications in our expectations of treatment outcome,” Dr. Nesbitt cautioned.

Commenting on the best practices in blood pressure measurements in the office, Dr. Nesbitt said that patients need to be seated with their feet on the floor and their backs and arms supported. In addition, patients need to have at least 5 minutes of rest without talking.

“It is very important to help patients understand what triggers their blood pressure to be elevated and teach them how and when to measure their blood pressure at home using their own devices,” she added.

Another critical question is how to translate the new guidelines into changes in clinical care, she said.

Current treatment landscape of hypertension

Ensuring a healthy diet, weight, and sleep, participating in physical activity, avoiding nicotine, and managing blood pressure, cholesterol, and sugar levels are the new “Life’s Essential 8” strategies proposed by the American Heart Association (AHA) to reduce CVD risk.

“Sleep has recently been added to the AHA guidelines because it modulates many factors contributing to hypertension,” Dr. Nesbitt pointed out. She advised that clinicians should ask patients about their sleep and educate them on healthy sleeping habits.

Some of the evidence used to develop the new AHA guidelines is derived from the SPRINT trial, which showed that controlling blood pressure reduces the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events. “This is our ultimate goal for our patients with hypertension,” Dr. Nesbitt noted.

Regarding the best practice in hypertension management, Dr. Nesbitt explained that with the new blood pressure thresholds, more patients will be diagnosed with stage 1 hypertension and need the nonpharmacological therapy suggested by the AHA. But patients with stage 1 hypertension and with a high CVD risk (at least 10%) also should receive blood pressure-lowering medications, so an accurate assessment of the risk of clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or the estimated 10-year CVD risk is crucial. “If we are not careful, we might miss some patients who need to be treated,” she said.

Calcium channel blockers, thiazide diuretics, and ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are the treatment of choice for patients with newly diagnosed hypertension. Although extensively used in the past, beta-blockers are no longer a first-line treatment for hypertension.

When asked why beta-blockers are no longer suitable for routine initial treatment of hypertension, Dr. Nesbitt said that they are effective in controlling palpitations but “other antihypertensive drugs have proven far better in controlling blood pressure.”

Hypertension is multifactorial and often occurs in combination with other conditions, including diabetes and chronic kidney disease. When developing a treatment plan for patients with hypertension, comorbidities need to be considered, because their management may also help control blood pressure, especially for conditions that may contribute to the development of hypertension.

Common conditions that contribute to and often coexist with hypertension include sleep apnea, obesity, anxiety, and depression. However, convincing people to seek mental health support can be very challenging, Dr. Nesbitt said.

She added that hypertension is a complex disease with a strong social component. Understanding its pathophysiology and social determinants is paramount for successfully managing hypertension at the individual level, as well as at the community level.

Identification and management of side effects is key

Dr. Nesbitt also discussed the importance of the identification and management of side effects associated with blood pressure-lowering drugs. She cautioned that, if not managed, side effects can lead to treatment nonadherence and pseudo‐resistance, both of which can jeopardize the successful management of hypertension.

When asked about her approach to managing side effects and convincing patients to continue taking their medications, Dr. Nesbitt noted that “setting realistic expectations and goals is key.”

In an interview after Dr. Nesbitt’s presentation, Jesica Naanous, MD, agreed that having an honest conversation with the patients is the best way to convince them to keep taking their medications. She also explains to patients that the complications of uncontrolled blood pressure are worse than the side effects of the drugs.

“As a last resort, I change a blood pressure-lowering agent to another,” added Dr. Naanous, an internist at the American British Cowdray (ABC) Medical Center in Mexico City. She explained that many antihypertensive drugs have different toxicity profiles, and simply changing to another agent can make treatment more tolerable for the patient.

Dr. Nesbitt reported no relationships with entities whose primary business is producing, marketing, selling, reselling, or distributing health care products used by or on patients.

AT INTERNAL MEDICINE 2023

Can an endoscopic procedure treat type 2 diabetes?

Called recellularization via electroporation therapy (ReCET), the technology, manufactured by Endogenex, uses a specialized catheter to deliver alternating electric pulses to the duodenum to induce cellular regeneration. This process is thought to improve insulin sensitivity, in part, by altering gut hormones and nutritional sensing, principal investigator Jacques Bergman, MD, PhD, said in a press briefing held in conjunction with the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW), where he will present the data on May 9.

In the first-in-human study of ReCET, 12 of 14 patients were able to come off insulin for up to a year following the procedure when combined with the use of the glucagonlike peptide–1 agonist semaglutide.

“This might be a game changer in the management of type 2 diabetes because a single outpatient endoscopic intervention was suggested to have a pretty long therapeutic effect, which is compliance-free, as opposed to drug therapy that relies on patients taking the drugs on a daily basis,” said Dr. Bergman, professor of gastrointestinal endoscopy at Amsterdam University Medical Center.

Moreover, he added, “this technique is disease-modifying, so it goes to the root cause of type 2 diabetes and tackles the insulin resistance, as opposed to drug therapy, which at best, is disease-controlling, and the effect is immediately gone if you stop the medication.”

ReCET is similar to another product, Fractyl’s Revita DMR, for which Dr. Bergman was involved in a randomized clinical trial. He said in an interview that the two technologies differ in that the Revita uses heat with submucosal lifting to avoid deeper heat penetration, whereas ReCET is nonthermal. He is also involved in a second randomized trial of the Revita.

Is semaglutide muddying the findings?

Asked to comment about the current study with ReCET, Ali Aminian, MD, professor of surgery and director of the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute at the Cleveland Clinic, said that the treatment effect is certainly plausible.

“The observation that hyperglycemia rapidly and substantially improves after bariatric surgery has prompted innovators to search for novel endoscopic procedures targeting the GI tract to improve diabetes and metabolic disease. Over the years, we learned that in addition to its role in digestion and absorption, the GI tract is actually a large endocrine organ which contributes to development of diabetes and metabolic disease.”

However, Dr. Aminian said that, “while these preliminary findings on a very small number of patients with a very short follow-up time are interesting,” he faulted the study design for including semaglutide. “When patients are treated with a combination of therapies, it will be hard to understand the true effect of each therapy,” and particularly, “when we add a strong diabetes medication like semaglutide.”

Dr. Bergman said semaglutide was used to “boost the insulin-resistant effect of the endoscopic treatment,” and that a planned double-blind, randomized trial will “show how much semaglutide actually contributed to the effect.” The ultimate goal, he noted, is to eliminate the need for all medications.

Moreover, when people with type 2 diabetes add semaglutide to insulin treatment, only about 20% typically are able to quit taking the insulin, in contrast to the 86% seen in this study, lead author Celine Busch, MBBS, a PhD candidate in gastroenterology at Amsterdam University, said in a DDW statement.

Dr. Aminian said, “I’m looking forward to better quality data ... from studies with a stronger design to prove safety, efficacy, and durability of this endoscopic intervention in patients with diabetes.”

But, he also cautioned, “in the past few years, other endoscopic procedures targeting the duodenum were introduced with exciting initial findings based on a small series [with a] short-term follow-up time. However, their safety, efficacy, and durability were not proven in subsequent studies.”

All patients stopped insulin, most for a year

The single-arm, single-center study involved 14 patients with type 2 diabetes taking basal but not premeal insulin. All underwent the 1-hour outpatient ReCET procedure, which involved placing a catheter into the first part of the small bowel and delivering electrical pulses to the duodenum.

Patients adhered to a calorie-controlled liquid diet for 2 weeks, after which they were initiated on semaglutide. All 14 patients were able to come off insulin for 3 months while maintaining glycemic control, and 12 were able to come off insulin for 12 months. They also experienced a 50% reduction in liver fat.

Dr. Bergman said a randomized, double-blind study using a sham procedure for controls is expected to start in about 2 months. “But for now, we are very encouraged by the potential for controlling type 2 diabetes with a single endoscopic treatment.”

Dr. Bergman has reported serving on the advisory board for Endogenex. Dr. Aminian has reported receiving research support and honorarium from Medtronic and Ethicon.

The meeting is sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Called recellularization via electroporation therapy (ReCET), the technology, manufactured by Endogenex, uses a specialized catheter to deliver alternating electric pulses to the duodenum to induce cellular regeneration. This process is thought to improve insulin sensitivity, in part, by altering gut hormones and nutritional sensing, principal investigator Jacques Bergman, MD, PhD, said in a press briefing held in conjunction with the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW), where he will present the data on May 9.

In the first-in-human study of ReCET, 12 of 14 patients were able to come off insulin for up to a year following the procedure when combined with the use of the glucagonlike peptide–1 agonist semaglutide.

“This might be a game changer in the management of type 2 diabetes because a single outpatient endoscopic intervention was suggested to have a pretty long therapeutic effect, which is compliance-free, as opposed to drug therapy that relies on patients taking the drugs on a daily basis,” said Dr. Bergman, professor of gastrointestinal endoscopy at Amsterdam University Medical Center.