User login

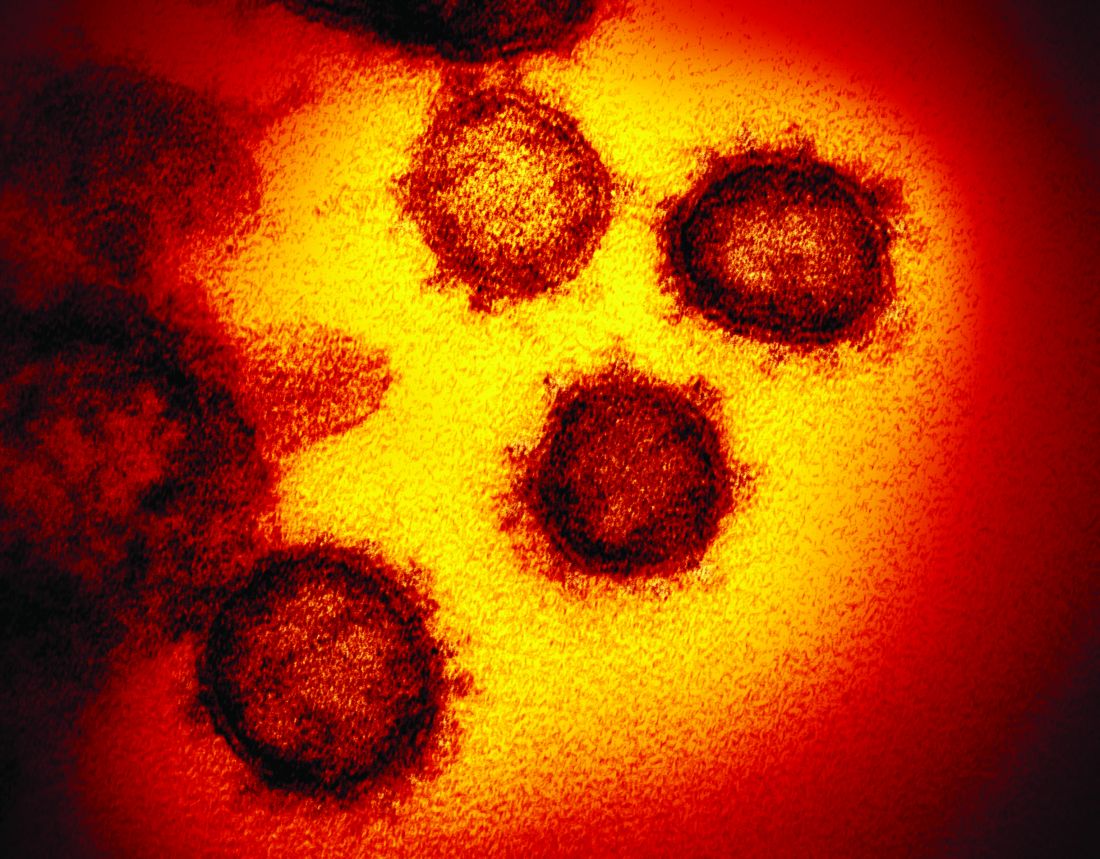

A novel coronavirus, the causative agent of the current pandemic of viral respiratory illness and pneumonia, was first identified in Wuhan, Hubei, China. The disease has been given the name, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The virus at last report has spread to more than 100 countries. Much of what we suspect about this virus comes from work on other severe coronavirus respiratory disease outbreaks – Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). MERS-CoV was a viral respiratory disease, first reported in Saudi Arabia, that was identified in more than 27 additional countries. The disease was characterized by severe acute respiratory illness, including fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Among 2,499 cases, only two patients tested positive for MERS-CoV in the United States. SARS-CoV also caused a severe viral respiratory illness. SARS was first recognized in Asia in 2003 and was subsequently reported in approximately 25 countries. The last case reported was in 2004.

As of March 13, there are 137,066 cases worldwide of COVID-19 and 1,701 in the United States, according to the John Hopkins University Coronavirus COVID-19 resource center.

What about children?

The remarkable observation is how few seriously ill children have been identified in the face of global spread. Unlike the H1N1 influenza epidemic of 2009, where older adults were relatively spared and children were a major target population, COVID-19 appears to be relatively infrequent in children or too mild to come to diagnosis, to date. Specifically, among China’s first approximately 44,000 cases, less than 2% were identified in children less than 20 years of age, and severe disease was uncommon with no deaths in children less than 10 years of age reported. One child, 13 months of age, with acute respiratory distress syndrome and septic shock was reported in China. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention webcast , children present with fever in about 50% of cases, cough, fatigue, and subsequently some (3%-30%) progress to shortness of breath. Some children and adults have presented with gastrointestinal disease initially. Viral RNA has been detected in respiratory secretions, blood, and stool of affected children; however, the samples were not cultured for virus so whether stool is a potential source for transmission is unclear. In adults, the disease appears to be most severe – with development of pneumonia – in the second week of illness. In both children and adults, the chest x-ray findings are an interstitial pneumonitis, ground glass appearance, and/or patchy infiltrates.

Are some children at greater risk? Are children the source of community transmission? Will children become a greater part of the disease pattern as further cases are identified and further testing is available? We cannot answer many of these questions about COVID-19 in children as yet, but as you are aware, data are accumulating daily, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health are providing regular updates.

A report from China gave us some idea about community transmission and infection risk for children. The Shenzhen CDC identified 391 COVID-19 cases and 1,286 close contacts. Household contacts and those persons traveling with a case of the virus were at highest risk of acquisition. The secondary attack rates within households was 15%; children were as likely to become infected as adults (medRxiv preprint. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.03.20028423).

What about pregnant women?

The data on pregnant women are even more limited. The concern about COVID-19 during pregnancy comes from our knowledge of adverse outcomes from other respiratory viral infections. For example, respiratory viral infections such as influenza have been associated with increased maternal risk of severe disease, and adverse neonatal outcomes, including low birth weight and preterm birth. The experience with SARS also is concerning for excess adverse maternal and neonatal complications such as spontaneous miscarriage, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, admission to the ICU, renal failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy all were reported as complications of SARS infection during pregnancy.

Two studies on COVID-19 in pregnancy have been reported to date. In nine pregnant women reported by Chen et al., COVID-19 pneumonia was identified in the third trimester. The women presented with fever, cough, myalgia, sore throat, and/or malaise. Fetal distress was reported in two; all nine infants were born alive. Apgar scores were 8-10 at 1 minute. Five were found to have lymphopenia; three had increases in hepatic enzymes. None of the infants developed severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Amniotic fluid, cord blood, neonatal throat swab, and breast milk samples from six of the nine patients were tested for the novel coronavirus 2019, and all results were negative (Lancet. 2020 Feb 12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[20]30360-3)https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30360-3/fulltext.

In a study by Zhu et al., nine pregnant women with confirmed COVID-19 infection were identified during Jan. 20-Feb. 5, 2020. The onset of clinical symptoms in these women occurred before delivery in four cases, on the day of delivery in two cases, and after delivery in three cases. Of the 10 neonates (one set of twins) many had clinical symptoms, but none were proven to be COVID-19 positive in their pharyngeal swabs. Shortness of breath was observed in six, fever in two, tachycardia in one. GI symptoms such as feeding intolerance, bloating, GI bleed, and vomiting also were observed. Chest radiography showed abnormalities in seven neonates at admission. Thrombocytopenia and/or disseminated intravascular coagulopathy also was reported. Five neonates recovered and were discharged, one died, and four neonates remained in hospital in a stable condition. It is unclear if the illness in these infants was related to COVID-19 (Transl Pediatrics. 2020 Feb. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.02.06)http://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/35919/28274.

In the limited experience to date, no evidence of virus has been found in the breast milk of women with COVID-19, which is consistent with the SARS experience. Current recommendations are to separate the infant from known COVID-19 infected mothers either in a different room or in the mother’s room using a six foot rule, a barrier curtain of some type, and mask and hand washing prior to any contact between mother and infant. If the mother desires to breastfeed her child, the same precautions – mask and hand washing – should be in place.

What about treatment?

There are no proven effective therapies and supportive care has been the mainstay to date. Clinical trials of remdesivir have been initiated both by Gilead (compassionate use, open label) and by the National Institutes of Health (randomized remdesivirhttps://www.drugs.com/history/remdesivir.html vs. placebo) in adults based on in vitro data suggesting activity again COVID-19. Lopinavir/ritonavir (combination protease inhibitors) also have been administered off label, but no results are available as yet.

Keeping up

I suggest several valuable resources to keep yourself abreast of the rapidly changing COVID-19 story. First the CDC website or your local Department of Health. These are being updated frequently and include advisories on personal protective equipment, clusters of cases in your local community, and current recommendations for mitigation of the epidemic. I have listened to Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Robert R. Redfield, MD, the director of the CDC almost daily. I trust their viewpoints and transparency about what is and what is not known, as well as the why and wherefore of their guidance, remembering that each day brings new information and new guidance.

Dr. Pelton is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University and public health and senior attending physician at Boston Medical Center. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

A novel coronavirus, the causative agent of the current pandemic of viral respiratory illness and pneumonia, was first identified in Wuhan, Hubei, China. The disease has been given the name, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The virus at last report has spread to more than 100 countries. Much of what we suspect about this virus comes from work on other severe coronavirus respiratory disease outbreaks – Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). MERS-CoV was a viral respiratory disease, first reported in Saudi Arabia, that was identified in more than 27 additional countries. The disease was characterized by severe acute respiratory illness, including fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Among 2,499 cases, only two patients tested positive for MERS-CoV in the United States. SARS-CoV also caused a severe viral respiratory illness. SARS was first recognized in Asia in 2003 and was subsequently reported in approximately 25 countries. The last case reported was in 2004.

As of March 13, there are 137,066 cases worldwide of COVID-19 and 1,701 in the United States, according to the John Hopkins University Coronavirus COVID-19 resource center.

What about children?

The remarkable observation is how few seriously ill children have been identified in the face of global spread. Unlike the H1N1 influenza epidemic of 2009, where older adults were relatively spared and children were a major target population, COVID-19 appears to be relatively infrequent in children or too mild to come to diagnosis, to date. Specifically, among China’s first approximately 44,000 cases, less than 2% were identified in children less than 20 years of age, and severe disease was uncommon with no deaths in children less than 10 years of age reported. One child, 13 months of age, with acute respiratory distress syndrome and septic shock was reported in China. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention webcast , children present with fever in about 50% of cases, cough, fatigue, and subsequently some (3%-30%) progress to shortness of breath. Some children and adults have presented with gastrointestinal disease initially. Viral RNA has been detected in respiratory secretions, blood, and stool of affected children; however, the samples were not cultured for virus so whether stool is a potential source for transmission is unclear. In adults, the disease appears to be most severe – with development of pneumonia – in the second week of illness. In both children and adults, the chest x-ray findings are an interstitial pneumonitis, ground glass appearance, and/or patchy infiltrates.

Are some children at greater risk? Are children the source of community transmission? Will children become a greater part of the disease pattern as further cases are identified and further testing is available? We cannot answer many of these questions about COVID-19 in children as yet, but as you are aware, data are accumulating daily, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health are providing regular updates.

A report from China gave us some idea about community transmission and infection risk for children. The Shenzhen CDC identified 391 COVID-19 cases and 1,286 close contacts. Household contacts and those persons traveling with a case of the virus were at highest risk of acquisition. The secondary attack rates within households was 15%; children were as likely to become infected as adults (medRxiv preprint. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.03.20028423).

What about pregnant women?

The data on pregnant women are even more limited. The concern about COVID-19 during pregnancy comes from our knowledge of adverse outcomes from other respiratory viral infections. For example, respiratory viral infections such as influenza have been associated with increased maternal risk of severe disease, and adverse neonatal outcomes, including low birth weight and preterm birth. The experience with SARS also is concerning for excess adverse maternal and neonatal complications such as spontaneous miscarriage, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, admission to the ICU, renal failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy all were reported as complications of SARS infection during pregnancy.

Two studies on COVID-19 in pregnancy have been reported to date. In nine pregnant women reported by Chen et al., COVID-19 pneumonia was identified in the third trimester. The women presented with fever, cough, myalgia, sore throat, and/or malaise. Fetal distress was reported in two; all nine infants were born alive. Apgar scores were 8-10 at 1 minute. Five were found to have lymphopenia; three had increases in hepatic enzymes. None of the infants developed severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Amniotic fluid, cord blood, neonatal throat swab, and breast milk samples from six of the nine patients were tested for the novel coronavirus 2019, and all results were negative (Lancet. 2020 Feb 12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[20]30360-3)https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30360-3/fulltext.

In a study by Zhu et al., nine pregnant women with confirmed COVID-19 infection were identified during Jan. 20-Feb. 5, 2020. The onset of clinical symptoms in these women occurred before delivery in four cases, on the day of delivery in two cases, and after delivery in three cases. Of the 10 neonates (one set of twins) many had clinical symptoms, but none were proven to be COVID-19 positive in their pharyngeal swabs. Shortness of breath was observed in six, fever in two, tachycardia in one. GI symptoms such as feeding intolerance, bloating, GI bleed, and vomiting also were observed. Chest radiography showed abnormalities in seven neonates at admission. Thrombocytopenia and/or disseminated intravascular coagulopathy also was reported. Five neonates recovered and were discharged, one died, and four neonates remained in hospital in a stable condition. It is unclear if the illness in these infants was related to COVID-19 (Transl Pediatrics. 2020 Feb. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.02.06)http://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/35919/28274.

In the limited experience to date, no evidence of virus has been found in the breast milk of women with COVID-19, which is consistent with the SARS experience. Current recommendations are to separate the infant from known COVID-19 infected mothers either in a different room or in the mother’s room using a six foot rule, a barrier curtain of some type, and mask and hand washing prior to any contact between mother and infant. If the mother desires to breastfeed her child, the same precautions – mask and hand washing – should be in place.

What about treatment?

There are no proven effective therapies and supportive care has been the mainstay to date. Clinical trials of remdesivir have been initiated both by Gilead (compassionate use, open label) and by the National Institutes of Health (randomized remdesivirhttps://www.drugs.com/history/remdesivir.html vs. placebo) in adults based on in vitro data suggesting activity again COVID-19. Lopinavir/ritonavir (combination protease inhibitors) also have been administered off label, but no results are available as yet.

Keeping up

I suggest several valuable resources to keep yourself abreast of the rapidly changing COVID-19 story. First the CDC website or your local Department of Health. These are being updated frequently and include advisories on personal protective equipment, clusters of cases in your local community, and current recommendations for mitigation of the epidemic. I have listened to Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Robert R. Redfield, MD, the director of the CDC almost daily. I trust their viewpoints and transparency about what is and what is not known, as well as the why and wherefore of their guidance, remembering that each day brings new information and new guidance.

Dr. Pelton is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University and public health and senior attending physician at Boston Medical Center. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

A novel coronavirus, the causative agent of the current pandemic of viral respiratory illness and pneumonia, was first identified in Wuhan, Hubei, China. The disease has been given the name, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The virus at last report has spread to more than 100 countries. Much of what we suspect about this virus comes from work on other severe coronavirus respiratory disease outbreaks – Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). MERS-CoV was a viral respiratory disease, first reported in Saudi Arabia, that was identified in more than 27 additional countries. The disease was characterized by severe acute respiratory illness, including fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Among 2,499 cases, only two patients tested positive for MERS-CoV in the United States. SARS-CoV also caused a severe viral respiratory illness. SARS was first recognized in Asia in 2003 and was subsequently reported in approximately 25 countries. The last case reported was in 2004.

As of March 13, there are 137,066 cases worldwide of COVID-19 and 1,701 in the United States, according to the John Hopkins University Coronavirus COVID-19 resource center.

What about children?

The remarkable observation is how few seriously ill children have been identified in the face of global spread. Unlike the H1N1 influenza epidemic of 2009, where older adults were relatively spared and children were a major target population, COVID-19 appears to be relatively infrequent in children or too mild to come to diagnosis, to date. Specifically, among China’s first approximately 44,000 cases, less than 2% were identified in children less than 20 years of age, and severe disease was uncommon with no deaths in children less than 10 years of age reported. One child, 13 months of age, with acute respiratory distress syndrome and septic shock was reported in China. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention webcast , children present with fever in about 50% of cases, cough, fatigue, and subsequently some (3%-30%) progress to shortness of breath. Some children and adults have presented with gastrointestinal disease initially. Viral RNA has been detected in respiratory secretions, blood, and stool of affected children; however, the samples were not cultured for virus so whether stool is a potential source for transmission is unclear. In adults, the disease appears to be most severe – with development of pneumonia – in the second week of illness. In both children and adults, the chest x-ray findings are an interstitial pneumonitis, ground glass appearance, and/or patchy infiltrates.

Are some children at greater risk? Are children the source of community transmission? Will children become a greater part of the disease pattern as further cases are identified and further testing is available? We cannot answer many of these questions about COVID-19 in children as yet, but as you are aware, data are accumulating daily, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health are providing regular updates.

A report from China gave us some idea about community transmission and infection risk for children. The Shenzhen CDC identified 391 COVID-19 cases and 1,286 close contacts. Household contacts and those persons traveling with a case of the virus were at highest risk of acquisition. The secondary attack rates within households was 15%; children were as likely to become infected as adults (medRxiv preprint. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.03.20028423).

What about pregnant women?

The data on pregnant women are even more limited. The concern about COVID-19 during pregnancy comes from our knowledge of adverse outcomes from other respiratory viral infections. For example, respiratory viral infections such as influenza have been associated with increased maternal risk of severe disease, and adverse neonatal outcomes, including low birth weight and preterm birth. The experience with SARS also is concerning for excess adverse maternal and neonatal complications such as spontaneous miscarriage, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, admission to the ICU, renal failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy all were reported as complications of SARS infection during pregnancy.

Two studies on COVID-19 in pregnancy have been reported to date. In nine pregnant women reported by Chen et al., COVID-19 pneumonia was identified in the third trimester. The women presented with fever, cough, myalgia, sore throat, and/or malaise. Fetal distress was reported in two; all nine infants were born alive. Apgar scores were 8-10 at 1 minute. Five were found to have lymphopenia; three had increases in hepatic enzymes. None of the infants developed severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Amniotic fluid, cord blood, neonatal throat swab, and breast milk samples from six of the nine patients were tested for the novel coronavirus 2019, and all results were negative (Lancet. 2020 Feb 12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[20]30360-3)https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30360-3/fulltext.

In a study by Zhu et al., nine pregnant women with confirmed COVID-19 infection were identified during Jan. 20-Feb. 5, 2020. The onset of clinical symptoms in these women occurred before delivery in four cases, on the day of delivery in two cases, and after delivery in three cases. Of the 10 neonates (one set of twins) many had clinical symptoms, but none were proven to be COVID-19 positive in their pharyngeal swabs. Shortness of breath was observed in six, fever in two, tachycardia in one. GI symptoms such as feeding intolerance, bloating, GI bleed, and vomiting also were observed. Chest radiography showed abnormalities in seven neonates at admission. Thrombocytopenia and/or disseminated intravascular coagulopathy also was reported. Five neonates recovered and were discharged, one died, and four neonates remained in hospital in a stable condition. It is unclear if the illness in these infants was related to COVID-19 (Transl Pediatrics. 2020 Feb. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.02.06)http://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/35919/28274.

In the limited experience to date, no evidence of virus has been found in the breast milk of women with COVID-19, which is consistent with the SARS experience. Current recommendations are to separate the infant from known COVID-19 infected mothers either in a different room or in the mother’s room using a six foot rule, a barrier curtain of some type, and mask and hand washing prior to any contact between mother and infant. If the mother desires to breastfeed her child, the same precautions – mask and hand washing – should be in place.

What about treatment?

There are no proven effective therapies and supportive care has been the mainstay to date. Clinical trials of remdesivir have been initiated both by Gilead (compassionate use, open label) and by the National Institutes of Health (randomized remdesivirhttps://www.drugs.com/history/remdesivir.html vs. placebo) in adults based on in vitro data suggesting activity again COVID-19. Lopinavir/ritonavir (combination protease inhibitors) also have been administered off label, but no results are available as yet.

Keeping up

I suggest several valuable resources to keep yourself abreast of the rapidly changing COVID-19 story. First the CDC website or your local Department of Health. These are being updated frequently and include advisories on personal protective equipment, clusters of cases in your local community, and current recommendations for mitigation of the epidemic. I have listened to Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Robert R. Redfield, MD, the director of the CDC almost daily. I trust their viewpoints and transparency about what is and what is not known, as well as the why and wherefore of their guidance, remembering that each day brings new information and new guidance.

Dr. Pelton is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University and public health and senior attending physician at Boston Medical Center. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].