User login

To the Editor:

A 41-year-old man presented with a slowly enlarging, tender, firm lesion on the left hallux of approximately 5 months' duration that initially appeared to be a blister. He reported no history of keloids or trauma to the left foot. On examination, a 3.5-cm, flesh-colored, pedunculated, firm nodule was present on the lateral aspect of the left great hallux (Figure 1). No lymphadenopathy was found. The lesion was diagnosed at that time as a keloid and treated with intralesional steroids without response. The patient was lost to follow-up, and after 5 months he presented again with pain and drainage from the lesion. Acute drainage resolved after antibiotic therapy. A shave biopsy was performed, which revealed findings consistent with a dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). A chest radiograph was unremarkable. Re-excision was performed with negative margins on frozen section but with positive peripheral and deep margins on permanent sections. The patient subsequently underwent amputation of the left great toe and was lost to follow-up after the initial postoperative period.

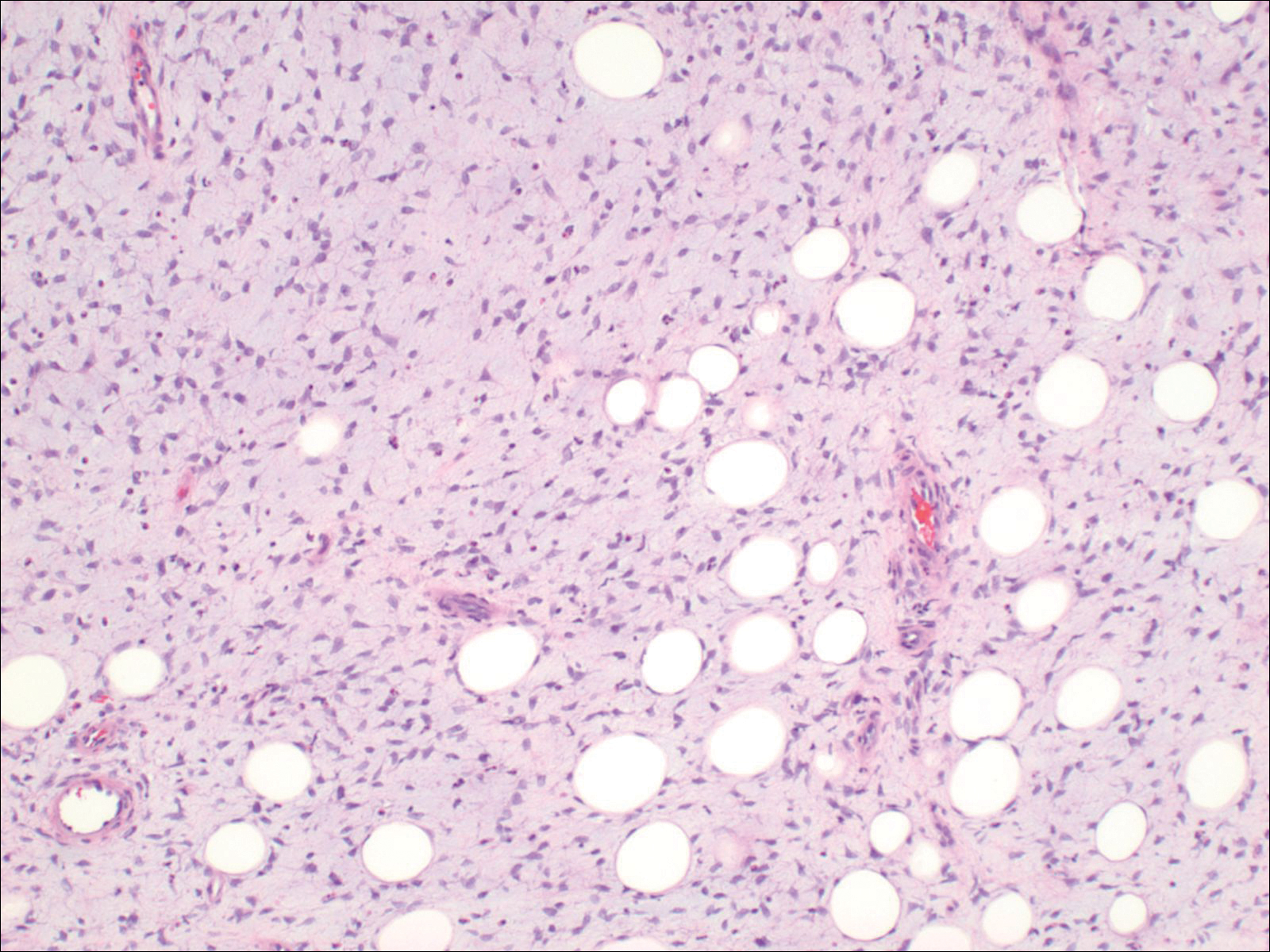

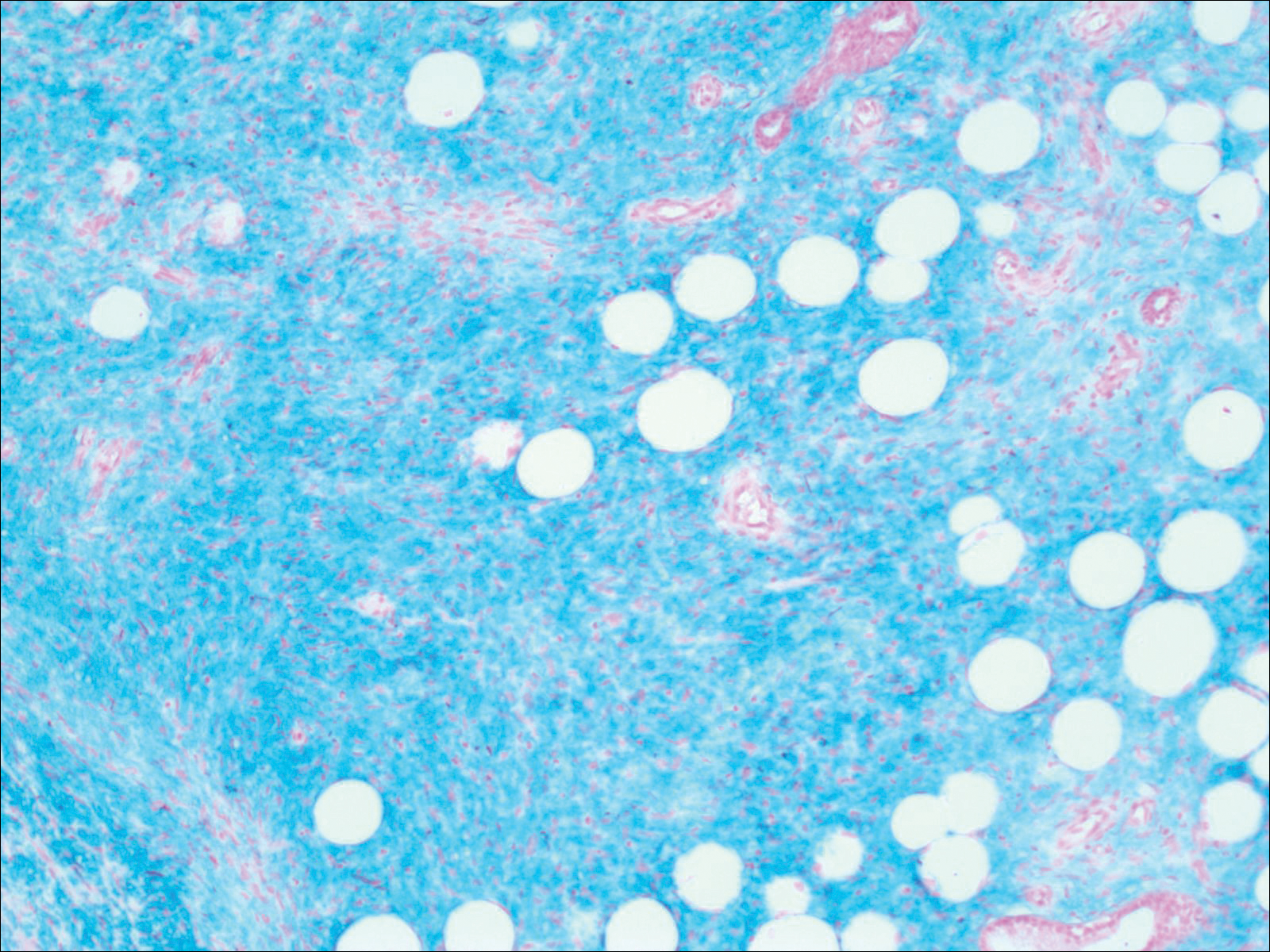

Histopathologic examination demonstrated a polypoid spindle cell tumor that filled the dermis and invaded into the subcutaneous adipose tissue (Figure 2). The spindle cells had tapered nuclei in a honeycomb arrangement with only mild nuclear pleomorphism arranged in fascicles with a herringbone formation. Areas showed a myxoid stroma with abundant mucin (Figure 3). Immunostaining demonstrated cells strongly positive for CD34 and negative for MART (melanoma-associated antigen recognized by T cells), S-100, and smooth muscle actin immunostains.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a sarcoma that is locally aggressive and tends to recur after surgical excision, though rare cases of metastasis involving the lungs have been reported.12 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans usually affects young to middle-aged adults. Acral DFSP is rare in adults, with tumors most commonly occurring on the trunk (50%-60%), proximal extremities (20%-30%), or the head and neck (10%-15%).1,2 A higher rate of acral DFSP has been found in children, which may be due to the increased rate of extremity trauma. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans commonly presents as an asymptomatic, slowly growing, indurated plaque that may be flesh colored or hyperpigmented, followed by development of erythematous firm nodules of up to several centimeters.1,3 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans may be associated with a purulent exudate or ulceration, and pain may develop as the lesion grows.

Histopathologic evaluation shows an early plaque stage characterized by low cellularity, minimal nuclear atypia, and rare mitotic figures.4 In the nodular stage, the spindle cells are arranged as short fascicles in a storiform arrangement and infiltrate the subcutaneous tissue in a honeycomb pattern with hyperchromatic nuclei and mitotic figures. The nodules may develop myxomatous areas as well as less-differentiated foci with intersecting fascicles in a herringbone pattern. Anti-CD34 antibody immunostaining demonstrates strongly positive spindle cells, while DFSP is negative for stromelysin 3, factor XIIIa, and D2-40, which can help to differentiate DFSP from dermatofibroma.5 The myxoid subtype of DFSP does not differ clinically or prognostically from conventional DFSP, though its recognition can be of use in differentiating other myxoid tumors. Myxoid DFSP is nearly always positive for CD34 and negative for the neural marker S-100 protein.6

Some reports have demonstrated that Mohs micrographic surgery is superior to wide local excision in treatment of DFSP, as it results in fewer local recurrences and metastases.7,8 Because of cytogenic abnormalities such as a reciprocal chromosomal (17;22) translocation or supernumerary ring chromosome derived from t(17;22) that place the PDGFB gene under the control of COL1A1 promoter, imatinib mesylate has been tested in DFSP and resulted in dramatic responses in both adults and children.9,10 Suggested uses of imatinib include metastatic disease and locally invasive disease not suitable for surgical excision as well as a method to debulk tumors prior to resection.11

- Gloster HM Jr. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(3, pt 1):355-374; quiz 375-376.

- Do AN, Goleno K, Geisse JK. Mohs micrographic surgery and partial amputation preserving function and aesthetics in digits: case reports of invasive melanoma and digital dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1516-1521.

- Taylor HB, Helwig EB. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a study of 115 cases. Cancer. 1962;15:717-725.

- Kamino H, Reddy VB, Pui J. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier; 2012:1961-1977.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Farhood AI. Dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: differential expression of CD34 and factor XIIIa. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:573-574.

- Llombart B, Serra-Guillén C, Monteagudo C, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a comprehensive review and update of diagnosis and management. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2013;30:13-28.

- Paradisi A, Abeni D, Rusciani A, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: wide local excision vs. Mohs micrographic surgery. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:728-736.

- Foroozan M, Sei JF, Amini M, et al. Efficacy of Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1055-1063.

- Patel KU, Szaebo SS, Hernandez VS, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans COL1A1-PDGFB fusion is identified in virtually all dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans cases when investigated by newly developed multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization assays. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:184-193.

- McArthur GA, Demetri GD, van Oosterom A, et al. Molecular and clinical analysis of locally advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans treated with imatinib: Imatinib Target Exploration Consortium Study B2225. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:866-873.

- Rutkowski P, Van Glabbeke M, Rankin CJ, et al; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Soft Tissue/Bone Sarcoma Group, Southwest Oncology Group. Imatinib mesylate in advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: pooled analysis of two phase II clinical trials [published online March 1, 2010]. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1772-1779.

- Mentzel T, Beham A, Katenkamp D, et al. Fibrosarcomatous ("high-grade") dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of a series of 41 cases with emphasis on prognostic significance. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:576-587.

To the Editor:

A 41-year-old man presented with a slowly enlarging, tender, firm lesion on the left hallux of approximately 5 months' duration that initially appeared to be a blister. He reported no history of keloids or trauma to the left foot. On examination, a 3.5-cm, flesh-colored, pedunculated, firm nodule was present on the lateral aspect of the left great hallux (Figure 1). No lymphadenopathy was found. The lesion was diagnosed at that time as a keloid and treated with intralesional steroids without response. The patient was lost to follow-up, and after 5 months he presented again with pain and drainage from the lesion. Acute drainage resolved after antibiotic therapy. A shave biopsy was performed, which revealed findings consistent with a dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). A chest radiograph was unremarkable. Re-excision was performed with negative margins on frozen section but with positive peripheral and deep margins on permanent sections. The patient subsequently underwent amputation of the left great toe and was lost to follow-up after the initial postoperative period.

Histopathologic examination demonstrated a polypoid spindle cell tumor that filled the dermis and invaded into the subcutaneous adipose tissue (Figure 2). The spindle cells had tapered nuclei in a honeycomb arrangement with only mild nuclear pleomorphism arranged in fascicles with a herringbone formation. Areas showed a myxoid stroma with abundant mucin (Figure 3). Immunostaining demonstrated cells strongly positive for CD34 and negative for MART (melanoma-associated antigen recognized by T cells), S-100, and smooth muscle actin immunostains.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a sarcoma that is locally aggressive and tends to recur after surgical excision, though rare cases of metastasis involving the lungs have been reported.12 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans usually affects young to middle-aged adults. Acral DFSP is rare in adults, with tumors most commonly occurring on the trunk (50%-60%), proximal extremities (20%-30%), or the head and neck (10%-15%).1,2 A higher rate of acral DFSP has been found in children, which may be due to the increased rate of extremity trauma. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans commonly presents as an asymptomatic, slowly growing, indurated plaque that may be flesh colored or hyperpigmented, followed by development of erythematous firm nodules of up to several centimeters.1,3 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans may be associated with a purulent exudate or ulceration, and pain may develop as the lesion grows.

Histopathologic evaluation shows an early plaque stage characterized by low cellularity, minimal nuclear atypia, and rare mitotic figures.4 In the nodular stage, the spindle cells are arranged as short fascicles in a storiform arrangement and infiltrate the subcutaneous tissue in a honeycomb pattern with hyperchromatic nuclei and mitotic figures. The nodules may develop myxomatous areas as well as less-differentiated foci with intersecting fascicles in a herringbone pattern. Anti-CD34 antibody immunostaining demonstrates strongly positive spindle cells, while DFSP is negative for stromelysin 3, factor XIIIa, and D2-40, which can help to differentiate DFSP from dermatofibroma.5 The myxoid subtype of DFSP does not differ clinically or prognostically from conventional DFSP, though its recognition can be of use in differentiating other myxoid tumors. Myxoid DFSP is nearly always positive for CD34 and negative for the neural marker S-100 protein.6

Some reports have demonstrated that Mohs micrographic surgery is superior to wide local excision in treatment of DFSP, as it results in fewer local recurrences and metastases.7,8 Because of cytogenic abnormalities such as a reciprocal chromosomal (17;22) translocation or supernumerary ring chromosome derived from t(17;22) that place the PDGFB gene under the control of COL1A1 promoter, imatinib mesylate has been tested in DFSP and resulted in dramatic responses in both adults and children.9,10 Suggested uses of imatinib include metastatic disease and locally invasive disease not suitable for surgical excision as well as a method to debulk tumors prior to resection.11

To the Editor:

A 41-year-old man presented with a slowly enlarging, tender, firm lesion on the left hallux of approximately 5 months' duration that initially appeared to be a blister. He reported no history of keloids or trauma to the left foot. On examination, a 3.5-cm, flesh-colored, pedunculated, firm nodule was present on the lateral aspect of the left great hallux (Figure 1). No lymphadenopathy was found. The lesion was diagnosed at that time as a keloid and treated with intralesional steroids without response. The patient was lost to follow-up, and after 5 months he presented again with pain and drainage from the lesion. Acute drainage resolved after antibiotic therapy. A shave biopsy was performed, which revealed findings consistent with a dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). A chest radiograph was unremarkable. Re-excision was performed with negative margins on frozen section but with positive peripheral and deep margins on permanent sections. The patient subsequently underwent amputation of the left great toe and was lost to follow-up after the initial postoperative period.

Histopathologic examination demonstrated a polypoid spindle cell tumor that filled the dermis and invaded into the subcutaneous adipose tissue (Figure 2). The spindle cells had tapered nuclei in a honeycomb arrangement with only mild nuclear pleomorphism arranged in fascicles with a herringbone formation. Areas showed a myxoid stroma with abundant mucin (Figure 3). Immunostaining demonstrated cells strongly positive for CD34 and negative for MART (melanoma-associated antigen recognized by T cells), S-100, and smooth muscle actin immunostains.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a sarcoma that is locally aggressive and tends to recur after surgical excision, though rare cases of metastasis involving the lungs have been reported.12 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans usually affects young to middle-aged adults. Acral DFSP is rare in adults, with tumors most commonly occurring on the trunk (50%-60%), proximal extremities (20%-30%), or the head and neck (10%-15%).1,2 A higher rate of acral DFSP has been found in children, which may be due to the increased rate of extremity trauma. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans commonly presents as an asymptomatic, slowly growing, indurated plaque that may be flesh colored or hyperpigmented, followed by development of erythematous firm nodules of up to several centimeters.1,3 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans may be associated with a purulent exudate or ulceration, and pain may develop as the lesion grows.

Histopathologic evaluation shows an early plaque stage characterized by low cellularity, minimal nuclear atypia, and rare mitotic figures.4 In the nodular stage, the spindle cells are arranged as short fascicles in a storiform arrangement and infiltrate the subcutaneous tissue in a honeycomb pattern with hyperchromatic nuclei and mitotic figures. The nodules may develop myxomatous areas as well as less-differentiated foci with intersecting fascicles in a herringbone pattern. Anti-CD34 antibody immunostaining demonstrates strongly positive spindle cells, while DFSP is negative for stromelysin 3, factor XIIIa, and D2-40, which can help to differentiate DFSP from dermatofibroma.5 The myxoid subtype of DFSP does not differ clinically or prognostically from conventional DFSP, though its recognition can be of use in differentiating other myxoid tumors. Myxoid DFSP is nearly always positive for CD34 and negative for the neural marker S-100 protein.6

Some reports have demonstrated that Mohs micrographic surgery is superior to wide local excision in treatment of DFSP, as it results in fewer local recurrences and metastases.7,8 Because of cytogenic abnormalities such as a reciprocal chromosomal (17;22) translocation or supernumerary ring chromosome derived from t(17;22) that place the PDGFB gene under the control of COL1A1 promoter, imatinib mesylate has been tested in DFSP and resulted in dramatic responses in both adults and children.9,10 Suggested uses of imatinib include metastatic disease and locally invasive disease not suitable for surgical excision as well as a method to debulk tumors prior to resection.11

- Gloster HM Jr. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(3, pt 1):355-374; quiz 375-376.

- Do AN, Goleno K, Geisse JK. Mohs micrographic surgery and partial amputation preserving function and aesthetics in digits: case reports of invasive melanoma and digital dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1516-1521.

- Taylor HB, Helwig EB. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a study of 115 cases. Cancer. 1962;15:717-725.

- Kamino H, Reddy VB, Pui J. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier; 2012:1961-1977.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Farhood AI. Dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: differential expression of CD34 and factor XIIIa. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:573-574.

- Llombart B, Serra-Guillén C, Monteagudo C, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a comprehensive review and update of diagnosis and management. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2013;30:13-28.

- Paradisi A, Abeni D, Rusciani A, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: wide local excision vs. Mohs micrographic surgery. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:728-736.

- Foroozan M, Sei JF, Amini M, et al. Efficacy of Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1055-1063.

- Patel KU, Szaebo SS, Hernandez VS, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans COL1A1-PDGFB fusion is identified in virtually all dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans cases when investigated by newly developed multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization assays. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:184-193.

- McArthur GA, Demetri GD, van Oosterom A, et al. Molecular and clinical analysis of locally advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans treated with imatinib: Imatinib Target Exploration Consortium Study B2225. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:866-873.

- Rutkowski P, Van Glabbeke M, Rankin CJ, et al; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Soft Tissue/Bone Sarcoma Group, Southwest Oncology Group. Imatinib mesylate in advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: pooled analysis of two phase II clinical trials [published online March 1, 2010]. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1772-1779.

- Mentzel T, Beham A, Katenkamp D, et al. Fibrosarcomatous ("high-grade") dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of a series of 41 cases with emphasis on prognostic significance. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:576-587.

- Gloster HM Jr. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(3, pt 1):355-374; quiz 375-376.

- Do AN, Goleno K, Geisse JK. Mohs micrographic surgery and partial amputation preserving function and aesthetics in digits: case reports of invasive melanoma and digital dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1516-1521.

- Taylor HB, Helwig EB. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a study of 115 cases. Cancer. 1962;15:717-725.

- Kamino H, Reddy VB, Pui J. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier; 2012:1961-1977.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Farhood AI. Dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: differential expression of CD34 and factor XIIIa. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:573-574.

- Llombart B, Serra-Guillén C, Monteagudo C, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a comprehensive review and update of diagnosis and management. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2013;30:13-28.

- Paradisi A, Abeni D, Rusciani A, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: wide local excision vs. Mohs micrographic surgery. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:728-736.

- Foroozan M, Sei JF, Amini M, et al. Efficacy of Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1055-1063.

- Patel KU, Szaebo SS, Hernandez VS, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans COL1A1-PDGFB fusion is identified in virtually all dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans cases when investigated by newly developed multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization assays. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:184-193.

- McArthur GA, Demetri GD, van Oosterom A, et al. Molecular and clinical analysis of locally advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans treated with imatinib: Imatinib Target Exploration Consortium Study B2225. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:866-873.

- Rutkowski P, Van Glabbeke M, Rankin CJ, et al; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Soft Tissue/Bone Sarcoma Group, Southwest Oncology Group. Imatinib mesylate in advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: pooled analysis of two phase II clinical trials [published online March 1, 2010]. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1772-1779.

- Mentzel T, Beham A, Katenkamp D, et al. Fibrosarcomatous ("high-grade") dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of a series of 41 cases with emphasis on prognostic significance. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:576-587.

Practice Points

- Consider dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans for a keloidlike enlarging lesion when there is no history of trauma or prior keloid formation.

- Treatments such as Mohs micrographic surgery or oral imatinib mesylate can provide lower recurrence rates in appropriate patients as stand-alone or adjuvant therapy.