User login

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common congenital anomaly, with an estimated incidence of 6-12 per 1,000 live births. It is also the congenital anomaly that most often leads to death or significant morbidity. Advances in surgical procedures and operating room care as well as specialized care in the ICU have led to significant improvements in survival over the past 10-20 years – even for the most complex cases of CHD. We now expect the majority of newborns with CHD not only to survive, but to grow up into adulthood.

The focus of clinical research has thus transitioned from survival to issues of long-term morbidity and outcomes, and the more recent literature has clearly shown us that children with CHD are at high risk of learning disabilities and other neurodevelopmental abnormalities. The prevalence of impairment rises with the complexity of CHD, from a prevalence of approximately 20% in mild CHD to as much as 75% in severe CHD. Almost all neonates and infants who undergo palliative surgical procedures have neurodevelopmental impairments.

The neurobehavioral “signature” of CHD includes cognitive defects (usually mild), short attention span, fine and gross motor delays, speech and language delays, visual motor integration, and executive function deficits. Executive function deficits and attention deficits are among the problems that often do not present in children until they reach middle school and beyond, when they are expected to learn more complicated material and handle more complex tasks. Long-term surveillance and care have thus become a major focus at our institution and others throughout the country.

At the same time, evidence has increased in the past 5-10 years that adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with complex CHD may stem from genetic factors as well as compromise to the brain in utero because of altered blood flow, compromise at the time of delivery, and insults during and after corrective or palliative surgery. Surgical strategies and operating room teams have become significantly better at protecting the brain, and new research now is directed toward understanding the neurologic abnormalities that are present in newborns prior to surgical intervention.

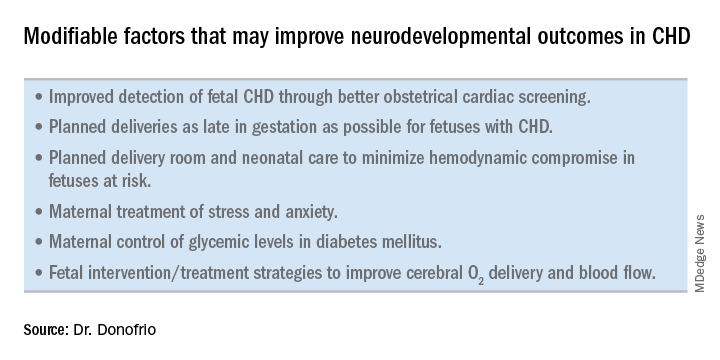

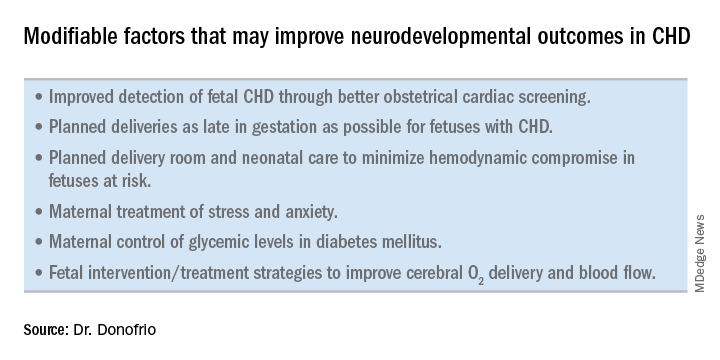

Increasingly, researchers are now focused on looking at the in utero origins of brain impairments in children with CHD and trying to understand specific prenatal causes, mechanisms, and potentially modifiable factors. We’re asking what we can do during pregnancy to improve neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Impaired brain growth

The question of how CHD affects blood flow to the fetal brain is an important one. We found some time ago in a study using Doppler ultrasound that 44% of fetuses with CHD had blood flow abnormalities in the middle cerebral artery at some point in the late second or third trimester, suggesting that the blood vessels had dilated to allow more cerebral perfusion. This phenomenon, termed “brain sparing,” is believed to be an autoregulatory mechanism that occurs as a result of diminished oxygen delivery or inadequate blood flow to the brain (Pediatr Cardiol. 2003 Jan;24[5]:436-43).

Subsequent studies have similarly documented abnormal cerebral blood flow in fetuses with various types of congenital heart lesions. What is left to be determined is whether this autoregulatory mechanism is adequate to maintain perfusion in the presence of specific, high-risk CHD.

Abnormalities were more often seen in CHD with obstructed aortic flow, such as hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) in which the aorta is perfused retrograde through the fetal ductus arteriosus (Circulation. 2010 Jan 4;121:26-33).

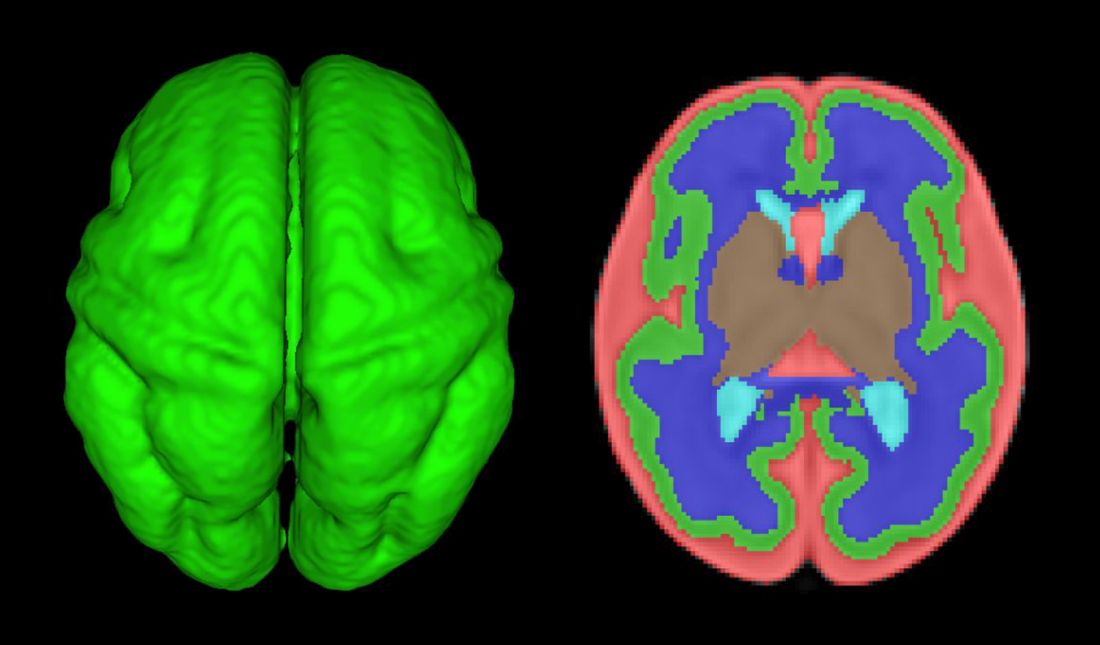

Other fetal imaging studies have similarly demonstrated a progressive third-trimester decrease in both cortical gray and white matter and in gyrification (cortical folding) (Cereb Cortex. 2013;23:2932-43), as well as decreased cerebral oxygen delivery and consumption (Circulation. 2015;131:1313-23) in fetuses with severe CHD. It appears that the brain may start out normal in size, but in the third trimester, the accelerated metabolic demands that come with rapid growth and development are not sufficiently met by the fetal cardiovascular circulation in CHD.

In the newborn with CHD, preoperative brain imaging studies have demonstrated structural abnormalities suggesting delayed development (for example, microcephaly and a widened operculum), microstructural abnormalities suggesting abnormal myelination and neuroaxonal development, and lower brain maturity scores (a composite score that combines multiple factors, such as myelination and cortical in-folding, to represent “brain age”).

Moreover, some of the newborn brain imaging studies have correlated brain MRI findings with neonatal neurodevelopmental assessments. For instance, investigators found that full-term newborns with CHD had decreased gray matter brain volume and increased cerebrospinal fluid volume and that these impairments were associated with poor behavioral state regulation and poor visual orienting (J Pediatr. 2014;164:1121-7).

Interestingly, it has been found that the full-term baby with specific complex CHD, including newborns with single ventricle CHD or transposition of the great arteries, is more likely to have a brain maturity score that is equivalent to that of a baby born at 35 weeks’ gestation. This means that, in some infants with CHD, the brain has lagged in growth by about a month, resulting in a pattern of disturbed development and subsequent injury that is similar to that of premature infants.

It also means that infants with CHD and an immature brain are especially vulnerable to brain injury when open-heart surgery is needed. In short, we now appreciate that the brain in patients with CHD is likely more fragile than we previously thought – and that this fragility is prenatal in its origins.

Delivery room planning

Ideally, our goal is to find ways of changing the circulation in utero to improve cerebral oxygenation and blood flow, and, consequently, improve brain development and long-term neurocognitive function. Despite significant efforts in this area, we’re not there yet.

Examples of strategies that are being tested include catheter intervention to open the aortic valve in utero for fetuses with critical aortic stenosis. This procedure currently is being performed to try to prevent progression of the valve abnormality to HLHS, but it has not been determined whether the intervention affects cerebral blood flow. Maternal oxygen therapy has been shown to change cerebral blood flow in the short term for fetuses with HLHS, but its long-term use has not been studied. At the time of birth, to prevent injury in the potentially more fragile brain of the newborn with CHD, what we can do is to identify those fetuses who are more likely to be at risk for hypoxia low cardiac output and hemodynamic compromise in the delivery room, and plan for specialized delivery room and perinatal management beyond standard neonatal care.

Most newborns with CHD are assigned to Level 1; they have no predicted risk of compromise in the delivery room – or even in the first couple weeks of life – and can deliver at a local hospital with neonatal evaluation and then consult with the pediatric cardiologist. Defects include shunt lesions such as septal defects or mild valve abnormalities.

Patients assigned to Level 2 have minimal risk of compromise in the delivery room but are expected to require postnatal surgery, cardiac catheterization, or another procedure before going home. They can be stabilized by the neonatologist, usually with initiation of a prostaglandin infusion, before transfer to the cardiac center for the planned intervention. Defects include single ventricle CHD and severe Tetralogy of Fallot.

Fetuses assigned to Level 3 and Level 4 are expected to have hemodynamic instability at cord clamping, requiring immediate specialty care in the delivery room that is likely to include urgent cardiac catheterization or surgical intervention. These defects are rare and include diagnoses such as transposition of the great arteries, HLHS with a restrictive or closed foramen ovale, and CHD with associated heart failure and hydrops.

We have found that fetal echocardiography accurately predicts postnatal risk and the need for specialized delivery room care in newborns diagnosed in utero with CHD and that level-of-care protocols ensure safe delivery and optimize fetal outcomes (J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1339-49; Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:737-47).

Such delivery planning, which is coordinated between obstetric, neonatal, cardiology, and surgical services with specialty teams as needed (for example, cardiac intensive care, interventional cardiology, and cardiac surgery), is recommended in a 2014 AHA statement on the diagnosis and treatment of fetal cardiac disease. In recent years it has become the standard of care in many health systems (Circulation. 2014;129[21]:2183-242).

The effect of maternal stress on the in utero environment is also getting increased attention in pediatric cardiology. Alterations in neurocognitive development and fetal and child cardiovascular health are likely to be associated with maternal stress during pregnancy, and studies have shown that maternal stress is high with prenatal diagnoses of CHD. We have to ask: Is stress a modifiable risk factor? There must be ways in which we can do better with prenatal counseling and support after a fetal diagnosis of CHD.

Screening for CHD

Initiating strategies to improve neurodevelopmental outcomes in infants with CHD rests partly on identifying babies with CHD before birth through improved fetal cardiac screening. Research cited in the 2014 AHA statement indicates that nearly all women giving birth to babies with CHD in the United States have obstetric ultrasound examinations in the second or third trimesters, but that only about 30% of the fetuses are diagnosed prenatally.

Current indications for referral for a fetal echocardiogram – in addition to suspicion of a structural heart abnormality on obstetric ultrasound – include maternal factors, such as diabetes mellitus, that raise the risk of CHD above the baseline population risk for low-risk pregnancies.

Women with pregestational diabetes mellitus have a nearly fivefold increase in CHD, compared with the general population (3%-5%), and should be referred for fetal echocardiography. Women with gestational diabetes mellitus have no or minimally increased risk for fetal CHD, but it has been shown that there is an increased risk for cardiac hypertrophy – particularly late in gestation – if glycemic levels are poorly controlled. The 2014 AHA guidelines recommend that fetal echocardiographic evaluation be considered in those who have HbA1c levels greater than 6% in the second half of pregnancy.

Dr. Mary T. Donofrio is a pediatric cardiologist and director of the fetal heart program and critical care delivery program at Children’s National Medical Center, Washington. She reported that she has no disclosures relevant to this article.

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common congenital anomaly, with an estimated incidence of 6-12 per 1,000 live births. It is also the congenital anomaly that most often leads to death or significant morbidity. Advances in surgical procedures and operating room care as well as specialized care in the ICU have led to significant improvements in survival over the past 10-20 years – even for the most complex cases of CHD. We now expect the majority of newborns with CHD not only to survive, but to grow up into adulthood.

The focus of clinical research has thus transitioned from survival to issues of long-term morbidity and outcomes, and the more recent literature has clearly shown us that children with CHD are at high risk of learning disabilities and other neurodevelopmental abnormalities. The prevalence of impairment rises with the complexity of CHD, from a prevalence of approximately 20% in mild CHD to as much as 75% in severe CHD. Almost all neonates and infants who undergo palliative surgical procedures have neurodevelopmental impairments.

The neurobehavioral “signature” of CHD includes cognitive defects (usually mild), short attention span, fine and gross motor delays, speech and language delays, visual motor integration, and executive function deficits. Executive function deficits and attention deficits are among the problems that often do not present in children until they reach middle school and beyond, when they are expected to learn more complicated material and handle more complex tasks. Long-term surveillance and care have thus become a major focus at our institution and others throughout the country.

At the same time, evidence has increased in the past 5-10 years that adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with complex CHD may stem from genetic factors as well as compromise to the brain in utero because of altered blood flow, compromise at the time of delivery, and insults during and after corrective or palliative surgery. Surgical strategies and operating room teams have become significantly better at protecting the brain, and new research now is directed toward understanding the neurologic abnormalities that are present in newborns prior to surgical intervention.

Increasingly, researchers are now focused on looking at the in utero origins of brain impairments in children with CHD and trying to understand specific prenatal causes, mechanisms, and potentially modifiable factors. We’re asking what we can do during pregnancy to improve neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Impaired brain growth

The question of how CHD affects blood flow to the fetal brain is an important one. We found some time ago in a study using Doppler ultrasound that 44% of fetuses with CHD had blood flow abnormalities in the middle cerebral artery at some point in the late second or third trimester, suggesting that the blood vessels had dilated to allow more cerebral perfusion. This phenomenon, termed “brain sparing,” is believed to be an autoregulatory mechanism that occurs as a result of diminished oxygen delivery or inadequate blood flow to the brain (Pediatr Cardiol. 2003 Jan;24[5]:436-43).

Subsequent studies have similarly documented abnormal cerebral blood flow in fetuses with various types of congenital heart lesions. What is left to be determined is whether this autoregulatory mechanism is adequate to maintain perfusion in the presence of specific, high-risk CHD.

Abnormalities were more often seen in CHD with obstructed aortic flow, such as hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) in which the aorta is perfused retrograde through the fetal ductus arteriosus (Circulation. 2010 Jan 4;121:26-33).

Other fetal imaging studies have similarly demonstrated a progressive third-trimester decrease in both cortical gray and white matter and in gyrification (cortical folding) (Cereb Cortex. 2013;23:2932-43), as well as decreased cerebral oxygen delivery and consumption (Circulation. 2015;131:1313-23) in fetuses with severe CHD. It appears that the brain may start out normal in size, but in the third trimester, the accelerated metabolic demands that come with rapid growth and development are not sufficiently met by the fetal cardiovascular circulation in CHD.

In the newborn with CHD, preoperative brain imaging studies have demonstrated structural abnormalities suggesting delayed development (for example, microcephaly and a widened operculum), microstructural abnormalities suggesting abnormal myelination and neuroaxonal development, and lower brain maturity scores (a composite score that combines multiple factors, such as myelination and cortical in-folding, to represent “brain age”).

Moreover, some of the newborn brain imaging studies have correlated brain MRI findings with neonatal neurodevelopmental assessments. For instance, investigators found that full-term newborns with CHD had decreased gray matter brain volume and increased cerebrospinal fluid volume and that these impairments were associated with poor behavioral state regulation and poor visual orienting (J Pediatr. 2014;164:1121-7).

Interestingly, it has been found that the full-term baby with specific complex CHD, including newborns with single ventricle CHD or transposition of the great arteries, is more likely to have a brain maturity score that is equivalent to that of a baby born at 35 weeks’ gestation. This means that, in some infants with CHD, the brain has lagged in growth by about a month, resulting in a pattern of disturbed development and subsequent injury that is similar to that of premature infants.

It also means that infants with CHD and an immature brain are especially vulnerable to brain injury when open-heart surgery is needed. In short, we now appreciate that the brain in patients with CHD is likely more fragile than we previously thought – and that this fragility is prenatal in its origins.

Delivery room planning

Ideally, our goal is to find ways of changing the circulation in utero to improve cerebral oxygenation and blood flow, and, consequently, improve brain development and long-term neurocognitive function. Despite significant efforts in this area, we’re not there yet.

Examples of strategies that are being tested include catheter intervention to open the aortic valve in utero for fetuses with critical aortic stenosis. This procedure currently is being performed to try to prevent progression of the valve abnormality to HLHS, but it has not been determined whether the intervention affects cerebral blood flow. Maternal oxygen therapy has been shown to change cerebral blood flow in the short term for fetuses with HLHS, but its long-term use has not been studied. At the time of birth, to prevent injury in the potentially more fragile brain of the newborn with CHD, what we can do is to identify those fetuses who are more likely to be at risk for hypoxia low cardiac output and hemodynamic compromise in the delivery room, and plan for specialized delivery room and perinatal management beyond standard neonatal care.

Most newborns with CHD are assigned to Level 1; they have no predicted risk of compromise in the delivery room – or even in the first couple weeks of life – and can deliver at a local hospital with neonatal evaluation and then consult with the pediatric cardiologist. Defects include shunt lesions such as septal defects or mild valve abnormalities.

Patients assigned to Level 2 have minimal risk of compromise in the delivery room but are expected to require postnatal surgery, cardiac catheterization, or another procedure before going home. They can be stabilized by the neonatologist, usually with initiation of a prostaglandin infusion, before transfer to the cardiac center for the planned intervention. Defects include single ventricle CHD and severe Tetralogy of Fallot.

Fetuses assigned to Level 3 and Level 4 are expected to have hemodynamic instability at cord clamping, requiring immediate specialty care in the delivery room that is likely to include urgent cardiac catheterization or surgical intervention. These defects are rare and include diagnoses such as transposition of the great arteries, HLHS with a restrictive or closed foramen ovale, and CHD with associated heart failure and hydrops.

We have found that fetal echocardiography accurately predicts postnatal risk and the need for specialized delivery room care in newborns diagnosed in utero with CHD and that level-of-care protocols ensure safe delivery and optimize fetal outcomes (J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1339-49; Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:737-47).

Such delivery planning, which is coordinated between obstetric, neonatal, cardiology, and surgical services with specialty teams as needed (for example, cardiac intensive care, interventional cardiology, and cardiac surgery), is recommended in a 2014 AHA statement on the diagnosis and treatment of fetal cardiac disease. In recent years it has become the standard of care in many health systems (Circulation. 2014;129[21]:2183-242).

The effect of maternal stress on the in utero environment is also getting increased attention in pediatric cardiology. Alterations in neurocognitive development and fetal and child cardiovascular health are likely to be associated with maternal stress during pregnancy, and studies have shown that maternal stress is high with prenatal diagnoses of CHD. We have to ask: Is stress a modifiable risk factor? There must be ways in which we can do better with prenatal counseling and support after a fetal diagnosis of CHD.

Screening for CHD

Initiating strategies to improve neurodevelopmental outcomes in infants with CHD rests partly on identifying babies with CHD before birth through improved fetal cardiac screening. Research cited in the 2014 AHA statement indicates that nearly all women giving birth to babies with CHD in the United States have obstetric ultrasound examinations in the second or third trimesters, but that only about 30% of the fetuses are diagnosed prenatally.

Current indications for referral for a fetal echocardiogram – in addition to suspicion of a structural heart abnormality on obstetric ultrasound – include maternal factors, such as diabetes mellitus, that raise the risk of CHD above the baseline population risk for low-risk pregnancies.

Women with pregestational diabetes mellitus have a nearly fivefold increase in CHD, compared with the general population (3%-5%), and should be referred for fetal echocardiography. Women with gestational diabetes mellitus have no or minimally increased risk for fetal CHD, but it has been shown that there is an increased risk for cardiac hypertrophy – particularly late in gestation – if glycemic levels are poorly controlled. The 2014 AHA guidelines recommend that fetal echocardiographic evaluation be considered in those who have HbA1c levels greater than 6% in the second half of pregnancy.

Dr. Mary T. Donofrio is a pediatric cardiologist and director of the fetal heart program and critical care delivery program at Children’s National Medical Center, Washington. She reported that she has no disclosures relevant to this article.

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common congenital anomaly, with an estimated incidence of 6-12 per 1,000 live births. It is also the congenital anomaly that most often leads to death or significant morbidity. Advances in surgical procedures and operating room care as well as specialized care in the ICU have led to significant improvements in survival over the past 10-20 years – even for the most complex cases of CHD. We now expect the majority of newborns with CHD not only to survive, but to grow up into adulthood.

The focus of clinical research has thus transitioned from survival to issues of long-term morbidity and outcomes, and the more recent literature has clearly shown us that children with CHD are at high risk of learning disabilities and other neurodevelopmental abnormalities. The prevalence of impairment rises with the complexity of CHD, from a prevalence of approximately 20% in mild CHD to as much as 75% in severe CHD. Almost all neonates and infants who undergo palliative surgical procedures have neurodevelopmental impairments.

The neurobehavioral “signature” of CHD includes cognitive defects (usually mild), short attention span, fine and gross motor delays, speech and language delays, visual motor integration, and executive function deficits. Executive function deficits and attention deficits are among the problems that often do not present in children until they reach middle school and beyond, when they are expected to learn more complicated material and handle more complex tasks. Long-term surveillance and care have thus become a major focus at our institution and others throughout the country.

At the same time, evidence has increased in the past 5-10 years that adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with complex CHD may stem from genetic factors as well as compromise to the brain in utero because of altered blood flow, compromise at the time of delivery, and insults during and after corrective or palliative surgery. Surgical strategies and operating room teams have become significantly better at protecting the brain, and new research now is directed toward understanding the neurologic abnormalities that are present in newborns prior to surgical intervention.

Increasingly, researchers are now focused on looking at the in utero origins of brain impairments in children with CHD and trying to understand specific prenatal causes, mechanisms, and potentially modifiable factors. We’re asking what we can do during pregnancy to improve neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Impaired brain growth

The question of how CHD affects blood flow to the fetal brain is an important one. We found some time ago in a study using Doppler ultrasound that 44% of fetuses with CHD had blood flow abnormalities in the middle cerebral artery at some point in the late second or third trimester, suggesting that the blood vessels had dilated to allow more cerebral perfusion. This phenomenon, termed “brain sparing,” is believed to be an autoregulatory mechanism that occurs as a result of diminished oxygen delivery or inadequate blood flow to the brain (Pediatr Cardiol. 2003 Jan;24[5]:436-43).

Subsequent studies have similarly documented abnormal cerebral blood flow in fetuses with various types of congenital heart lesions. What is left to be determined is whether this autoregulatory mechanism is adequate to maintain perfusion in the presence of specific, high-risk CHD.

Abnormalities were more often seen in CHD with obstructed aortic flow, such as hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) in which the aorta is perfused retrograde through the fetal ductus arteriosus (Circulation. 2010 Jan 4;121:26-33).

Other fetal imaging studies have similarly demonstrated a progressive third-trimester decrease in both cortical gray and white matter and in gyrification (cortical folding) (Cereb Cortex. 2013;23:2932-43), as well as decreased cerebral oxygen delivery and consumption (Circulation. 2015;131:1313-23) in fetuses with severe CHD. It appears that the brain may start out normal in size, but in the third trimester, the accelerated metabolic demands that come with rapid growth and development are not sufficiently met by the fetal cardiovascular circulation in CHD.

In the newborn with CHD, preoperative brain imaging studies have demonstrated structural abnormalities suggesting delayed development (for example, microcephaly and a widened operculum), microstructural abnormalities suggesting abnormal myelination and neuroaxonal development, and lower brain maturity scores (a composite score that combines multiple factors, such as myelination and cortical in-folding, to represent “brain age”).

Moreover, some of the newborn brain imaging studies have correlated brain MRI findings with neonatal neurodevelopmental assessments. For instance, investigators found that full-term newborns with CHD had decreased gray matter brain volume and increased cerebrospinal fluid volume and that these impairments were associated with poor behavioral state regulation and poor visual orienting (J Pediatr. 2014;164:1121-7).

Interestingly, it has been found that the full-term baby with specific complex CHD, including newborns with single ventricle CHD or transposition of the great arteries, is more likely to have a brain maturity score that is equivalent to that of a baby born at 35 weeks’ gestation. This means that, in some infants with CHD, the brain has lagged in growth by about a month, resulting in a pattern of disturbed development and subsequent injury that is similar to that of premature infants.

It also means that infants with CHD and an immature brain are especially vulnerable to brain injury when open-heart surgery is needed. In short, we now appreciate that the brain in patients with CHD is likely more fragile than we previously thought – and that this fragility is prenatal in its origins.

Delivery room planning

Ideally, our goal is to find ways of changing the circulation in utero to improve cerebral oxygenation and blood flow, and, consequently, improve brain development and long-term neurocognitive function. Despite significant efforts in this area, we’re not there yet.

Examples of strategies that are being tested include catheter intervention to open the aortic valve in utero for fetuses with critical aortic stenosis. This procedure currently is being performed to try to prevent progression of the valve abnormality to HLHS, but it has not been determined whether the intervention affects cerebral blood flow. Maternal oxygen therapy has been shown to change cerebral blood flow in the short term for fetuses with HLHS, but its long-term use has not been studied. At the time of birth, to prevent injury in the potentially more fragile brain of the newborn with CHD, what we can do is to identify those fetuses who are more likely to be at risk for hypoxia low cardiac output and hemodynamic compromise in the delivery room, and plan for specialized delivery room and perinatal management beyond standard neonatal care.

Most newborns with CHD are assigned to Level 1; they have no predicted risk of compromise in the delivery room – or even in the first couple weeks of life – and can deliver at a local hospital with neonatal evaluation and then consult with the pediatric cardiologist. Defects include shunt lesions such as septal defects or mild valve abnormalities.

Patients assigned to Level 2 have minimal risk of compromise in the delivery room but are expected to require postnatal surgery, cardiac catheterization, or another procedure before going home. They can be stabilized by the neonatologist, usually with initiation of a prostaglandin infusion, before transfer to the cardiac center for the planned intervention. Defects include single ventricle CHD and severe Tetralogy of Fallot.

Fetuses assigned to Level 3 and Level 4 are expected to have hemodynamic instability at cord clamping, requiring immediate specialty care in the delivery room that is likely to include urgent cardiac catheterization or surgical intervention. These defects are rare and include diagnoses such as transposition of the great arteries, HLHS with a restrictive or closed foramen ovale, and CHD with associated heart failure and hydrops.

We have found that fetal echocardiography accurately predicts postnatal risk and the need for specialized delivery room care in newborns diagnosed in utero with CHD and that level-of-care protocols ensure safe delivery and optimize fetal outcomes (J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1339-49; Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:737-47).

Such delivery planning, which is coordinated between obstetric, neonatal, cardiology, and surgical services with specialty teams as needed (for example, cardiac intensive care, interventional cardiology, and cardiac surgery), is recommended in a 2014 AHA statement on the diagnosis and treatment of fetal cardiac disease. In recent years it has become the standard of care in many health systems (Circulation. 2014;129[21]:2183-242).

The effect of maternal stress on the in utero environment is also getting increased attention in pediatric cardiology. Alterations in neurocognitive development and fetal and child cardiovascular health are likely to be associated with maternal stress during pregnancy, and studies have shown that maternal stress is high with prenatal diagnoses of CHD. We have to ask: Is stress a modifiable risk factor? There must be ways in which we can do better with prenatal counseling and support after a fetal diagnosis of CHD.

Screening for CHD

Initiating strategies to improve neurodevelopmental outcomes in infants with CHD rests partly on identifying babies with CHD before birth through improved fetal cardiac screening. Research cited in the 2014 AHA statement indicates that nearly all women giving birth to babies with CHD in the United States have obstetric ultrasound examinations in the second or third trimesters, but that only about 30% of the fetuses are diagnosed prenatally.

Current indications for referral for a fetal echocardiogram – in addition to suspicion of a structural heart abnormality on obstetric ultrasound – include maternal factors, such as diabetes mellitus, that raise the risk of CHD above the baseline population risk for low-risk pregnancies.

Women with pregestational diabetes mellitus have a nearly fivefold increase in CHD, compared with the general population (3%-5%), and should be referred for fetal echocardiography. Women with gestational diabetes mellitus have no or minimally increased risk for fetal CHD, but it has been shown that there is an increased risk for cardiac hypertrophy – particularly late in gestation – if glycemic levels are poorly controlled. The 2014 AHA guidelines recommend that fetal echocardiographic evaluation be considered in those who have HbA1c levels greater than 6% in the second half of pregnancy.

Dr. Mary T. Donofrio is a pediatric cardiologist and director of the fetal heart program and critical care delivery program at Children’s National Medical Center, Washington. She reported that she has no disclosures relevant to this article.