User login

Although hepatocellular carcinoma can be difficult to detect, use of the LI-RADS algorithm could lead to earlier identification in at-risk patients.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third most common cause of death from cancer worldwide.1 Liver cancer is the fifth most common cancer in men and the seventh in women.2 The highest incidence rates are in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia where hepatitis B virus is endemic. The incidence of HCC in western countries is increasing, particularly due to the rise of hepatitis C virus (HCV) as well as alcoholic liver disease and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. The incidence of HCC has tripled in the US in the past 2 decades.1-3

HCC can be diagnosed by radiographic images without the need for biopsy if the typical imaging features are present.3 The European Association for the Study of Liver Disease (EASL) and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommend screening abdominal ultrasonography at 6-month intervals for high-risk patients.3,4 High-risk patients include patients with cirrhosis, especially those with hepatitis B or C.3

If screening ultrasonography detects a nodule, size determines whether a follow-up ultrasound is needed vs obtaining a contrast-enhanced dynamic computed tomography (CT) scan or a magnetic resonance image (MRI).3 If ultrasonography detects a nodule > 1 cm in diameter, then a dynamic CT or MRI is performed. Characteristic hyperenhancement during later arterial phase and washout during the venous or delayed phase is associated with a nearly 100% specificity for HCC diagnosis.5 Arterial-enhancing contrast is required when using CT and MRI because HCC is a hypervascular lesion.6 The portal venous blood dilutes the majority of the liver’s arterial blood; therefore, the liver does not enhance during the arterial phase, while HCC will show maximum enhancement.7 Furthermore, HCC should demonstrate a “washout” of contrast during the venous phase on CT and MRI.4 Standard imaging protocol dictates that 4 phases are needed to properly diagnose HCC including unenhanced, arterial, venous, and delayed.4

Regular surveillance increases the likelihood of detecting HCC before the presentation of clinical symptoms and facilitates receipt of curative therapy.8-10 Patients with viral hepatitis and cirrhosis with HCC found on screening are more likely to have earlier-stage disease and survive longer from the time of diagnosis.11 Furthermore, it has been observed that HCC detected by surveillance is significantly more likely to undergo curative therapy compared with incidental or symptomatic detection of HCC.9

Technical improvements in imaging techniques include advancement in contrast agents, multidetector row helical CT, and the flexibility/range of pulse sequences available in MRI.7 Even with technical improvements in all modalities used in HCC imaging, detecting HCC remains difficult, especially when detecting the small (< 2 cm) lesions in a cirrhotic liver.7 Interpretation of imaging also remains a challenge as HCC does not always fit strict criteria: lack of “washout” in a hypervascular lesion, determining small HCC lesions from benign nodules, and hypovascular/isovascular HCC.5 Radiologic differentials in the diagnosis of HCC include transient hepatic intensity difference (THID)/transient hepatic attenuation difference (THAD), arterio-portal shunt, and regenerative nodules.12 In the common clinical setting, patients undergo multiple imaging studies that are interpreted by multiple radiologists, which can add to the difficulty in the diagnosis of HCC.13

The radiology community recognized the inconsistencies and complexities of HCC imaging. Therefore, the American College of Radiology endorsed the Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System (LI-RADS), which had the goal of reducing variability in lesion interpretation through standardization and improving communication with clinicians.14 LI-RADS uses a diagnostic algorithm for CT and MRI that categorizes observed liver findings in high-risk individuals based on the probability or relative risk of HCC without assigning a formal diagnosis.14 LI-RADS takes into account arterial phase enhancement, tumor size, washout appearance, the presence and nature of a capsule, and threshold growth.15 LI-RADS categorizes an observed liver finding on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 corresponding to a definitely benign finding and 5 with definitive HCC.14 Furthermore, LI-RADS sought to limit the technical variabilities among institutions.

LI-RADS was launched in 2011 and has been utilized by many clinical practices while continuing to be expanded and updated.16 Recent studies examined the specificity of LI-RADS as well as interreader variability.17,18 For nodules viewed on MRI, both LI-RADS categories 4 and 5 had high specificity for HCC.17 When looking at interreader repeatability, LI-RADS showed moderate agreement among experts using the diagnostic algorithm.19 Further studies have compared LI-RADS with the AASLD guidelines and the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) guidelines.16 When compared with other guidelines, LI-RADS expands the definition of indeterminate findings into probably benign, intermediate probability of HCC, and probably HCC, which corresponds to LI-RADS categories 2, 3, and 4.16

We looked retrospectively at a group of patients previously diagnosed with HCC to see whether utilizing the LI-RADS scoring system within our screening system might have allowed an earlier prediction of HCC and a timelier intervention. Prior to this investigation the LI-RADS system was not used for HCC screening at our US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facility. We examined screened patients at the Memphis VA Medical Center (MVAMC) in Tennessee who were subsequently diagnosed with HCC to see which LI-RADS category the last surveillance CT prior to diagnosis would fall into, 6 months to a year prior to the diagnosis of HCC. Our control population was a group of patients screened with CT for their liver nodules who were found not to have HCC.

Methods

Patients at MVAMC with cirrhosis and patients with chronic hepatitis B are routinely screened with ultrasound, CT, or MRI in accordance with the AASLD, EASL, and VA guidelines. Of 303 patients with HCV and cirrhosis under care in 2015, 242 (81%) received imaging to screen for HCC according to the VA National Hepatitis C Registry 2015 (Personal Communication, Population Health Service, Office of Patient Care Services).The LI-RADS scoring system was not applied as a standard screening methodology.

Under an institutional review board-approved protocol, we reviewed the charts of all patients diagnosed with HCC at MVAMC from 2009 to 2014, utilizing ICD-9 code of 155.0 for HCC. We identified within these charts patients who had a surveillance CT image performed within a 6- to 13-month period prior to the CTs that diagnosed HCC (prediagnostic HCC CT). Furthermore, we reviewed the charts of all patients diagnosed with benign liver nodules at MVAMC from 2009 to 2014, utilizing the ICD-9 code of 573.8 for other specified disorders of the liver.

Within these charts, we found patients who had a surveillance CT image performed and who were followed after that image with additional imaging for ≥ 2 years or who had a liver biopsy negative for HCC (benign surveillance CT). We compared these 2 sets of CTs utilizing LI-RADS criteria. Once these patients were identified, a list of the CTs to be examined were given to 2 MVAMC radiologists who specialize in CT.

No identifying information of the patients was included, and a 13-digit number unique to each CT exam identified the CTs to be reviewed. Radiologist 1 and 2 examined the CTs on the MVAMC Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS). Both radiologists were asked to give each nodule a score according to LI-RADS v2014 diagnostic algorithm (Figure).

We hypothesized that the prediagnostic CT images of patients eventually determined to have HCC would have a LI-RADS score of 4 (LR4) or LR5. Furthermore, we hypothesized that the CT images of the benign liver nodule patients would have a score ≤ LR3. If there was a disagreement between the radiologists in terms of a malignant score (LR4 or LR5) vs a benign score (≤ LR3), then a third radiologist (radiologist 3) provided a score for these nodules. The third, tiebreaker radiologist was given the scores of both prior radiologists and asked to choose which score was correct.

Statistical analysis was then applied to the data to determine the sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy in diagnosing eventual HCC, as well as the false-negative and false-positive rates of radiologists 1 and 2. Raw data also were used to determine the agreement between raters by calculating the κ statistic with a 95% CI.

Results

A total of 70 nodules were examined by radiologists 1 and 2 with 42 of the nodules in the prediagnostic HCC CTs and 28 of the nodules in the benign surveillance CTs.

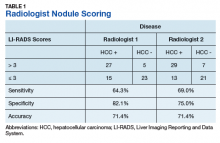

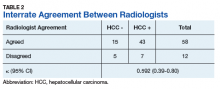

Radiologist 1 identified 11 patients with LR4 and 21 patients with LR5. His scores showed a sensitivity of 64.3% and specificity of 82.1% with accuracy of 71.4% for LI-RADS in identifying eventual HCC. The false-negative rate of the LI-RADS diagnostic algorithm for radiologist 1 was 35.7% and the false-positive rate was 17.9%. Radiologist 2 identified 17 patients LR4 and 19 patients with LR5. Radiologist 2’s scores showed a sensitivity of 69.0% and specificity of 75.0% with accuracy of 71.4% for LI-RADS in identifying eventual HCC.The false-negative rate of the LI-RADS diagnostic algorithm for radiologist 2 was 31.0% and false-positive rate of 25.0%. The κ statistic was calculated to determine the interrater agreement. The radiologists agreed on 58 of 70 samples; 15 without HCC and 43 with HCC. The κ statistic was 0.592, which indicates moderate agreement (Table 2).

Discussion

If HCC is diagnosed late in the disease process based on symptomatology and not on surveillance imaging, the likelihood of receiving early and potential curative therapy greatly declines as was shown in a systemic literature review.9 Surveillance imaging and lesion interpretation by various radiologists has been difficult to standardize as new technologic advances continue to occur in the imaging of HCC.14 LI-RADS was initiated to help standardize CT and MRI interpretation and reporting of hepatic nodules. As a dynamic algorithm, it continues to adjust with new advances in imaging techniques with the most recent updates being made to the algorithm in 2014.14,19 LI-RADS applies to patients at high risk for HCC most often who are already enrolled in a surveillance program.19 The MVAMC has a high incidence of patients with cirrhosis who are at risk for HCC, which is why we chose it as our study population.

LI-RADS can be applied to both MRI and CT imaging. Much of the recent literature have looked at LI-RADS in terms of MRI. A group in China looked at 100 pathologically confirmed patients and assigned a LI-RADS score to the MRI at the time of diagnosis and showed that MRI LI-RADS scoring was highly sensitive and specific in the diagnosis of HCC.20 This study did note a numeric difference in the specificity of LI-RADS algorithm depending on how LR3 scores were viewed. If a LR3 score was considered negative rather than positive for HCC, then the specificity increased by almost 20%.20

Another study looked at patients with liver nodules ≤ 20 mm found on ultrasound and obtained MRIs and biopsies on these patients, assigning the MRI a LI-RADs score.17 Darnell and colleagues found that MRI LR4 and LR5 have a high specificity for HCC. However, 29 of the 42 LR3 lesions examined were found to be HCC.17 Furthermore, Choi and colleagues retrospectively looked at patients in a HCC surveillance program who had undergone MRI as part of the program and assigned LI-RADS scores to these MRIs.21 Their study showed that LR5 criteria on gadoxetate disodium-enhanced MRI has excellent positive predictive value (PPV) for diagnosing HCC, and LR4 showed good PPV.21

In our study, we chose to look at LI-RADS in terms of surveillance CT scans 6 to 13 months prior to the diagnosis of HCC to see whether this method would allow us to intervene earlier with more aggressive diagnostics or therapy in those suspected of having HCC. Although Choi and colleagues looked retrospectively at MRI surveillance imaging, most of the prior studies have looked at LI-RADS scoring in imaging at the time of diagnosis.17,20,21 By looking at surveillance CT scans, we sought to determine LI-RADS sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy as a screening tool compared with CT evaluations without LI-RADS scoring.

We also chose to look at CT scans since most of the prior studies have looked at the more detailed and often more expensive MRIs. For both radiologists 1 and 2, the sensitivity was > 60% and specificity was > 70% with a diagnostic accuracy of 71.4% in predicting a diagnosis of HCC in future scans. Although there was high false negative of > 30% for both radiologists, we did consider LR3 as negative for HCC. As Darnell and colleagues’ study of MRI LI-RADS shows, LR3 may need to be revised in the future as its ambiguity can lead to false-negatives.17 Our results also showed moderate interreader agreement, which has been seen in previous studies with LI-RADS.18

Some studies have compared MRI with CT imaging in terms of LI-RADs classification of hepatic nodules to find out whether concordance was seen.22,23 Both studies found that there was substantial discordance between MRI and CT with CT often underscoring hepatic nodules.22,23 In Zhang and colleagues, interclass agreement between CT and MRI varied the most in terms of arterial enhancement with CT producing false-negative findings.22 CT also underestimated LI-RADS score by 16.9% for LR3, 37.3% for LR4, and 8.5% for LR5 in this study.22 Furthermore, Corwin and colleagues found a significant upgrade in terms of LI-RADS categorization with MRI for 42.5% of observations.23 In this study, upgraded LI-RADS scores on MRI included 2 upgraded to LR5V (Figure), 15 upgraded to LR5, and 12 upgraded to LR4.23

Our study shows that the LI-RADS algorithm has a good sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy as a screening tool, predicting HCC in scans earlier than standard CT evaluation. In our study, the patients with HCC were shown to have higher LI-RADS scores on prediagnostic imaging, while the benign liver nodule patients were shown to have lower LI-RADS scores. This data would suggest that a LI-RADS score given to surveillance CT of LR4 or higher should recommend either a biopsy or follow-up imaging after a short interval. If LI-RADS is applied to surveillance CTs in patients at risk for HCC, a diagnosis of HCC may be arrived at earlier as compared with not using the LI-RADS algorithm. Earlier detection may lead to earlier intervention and improved treatment outcomes.

Limitations

Limitations to our study occurred because radiologist 3 did not review all of the images nor score them. Radiologist 3 was limited to 12 images where there was disagreement and was limited to 2 scores to choose from for each image. Further limitations include that this study was performed at a single center. Our study focused on one imaging modality and did not include ultrasounds or MRIs. We did not compare the demographics of our patients with those of other VA hospitals. The radiologists interpreted the images individually, and their subjectivity was another limitation.

Conclusion

In the MVAMC population, LI-RADS showed a good sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy for CT surveillance scans in patient at high risk for HCC at an earlier time point than did standard evaluation by very experienced CT radiologists. Higher LI-RADS scores on surveillance CTs had good diagnostic accuracy for the probable future diagnosis of HCC, whereas lower LI-RADS scores had a good diagnostic accuracy for probable benign nodules. Utilizing the LI-RADS algorithm on all surveillance CTs in patients at high risk for HCC may lead to obtaining MRIs or follow-up CTs sooner for suspicious nodules, leading to an earlier diagnosis of HCC and possible earlier and more effective intervention.

1. El–Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(7):2557-2576.

2. El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1118-1127.

3. Bruix J, Sherman M; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53(3):1020-1022.

4. Selvapatt N, House H, Brown A. Hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance: are we utilizing it? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50(1):e8-e12.

5. Lee JM, Yoon JH, Joo I, Woo HS. Recent advances in CT and MR imaging for evaluation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2012;1(1):22-40.

6. Chou R, Cuevas C, Fu R, et al. Imaging techniques for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(10):697-711.

7. Ariff B, Lloyd CR, Khan S, et al. Imaging of liver cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(11):1289-1300.

8. Yuen MF, Cheng CC, Lauder IJ, Lam SK, Ooi CG, Lai CL. Early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma increases the chance of treatment: Hong Kong experience. Hepatology. 2000;31(2):330-335.

9. Singal AG, Pillai A, Tiro J. Early detection, curative treatment, and survival rates for hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in patients with cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11(4):e1001624.

10. Nusbaum, JD, Smirniotopoulos J, Wright HC, et al. The effect of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in an urban population with liver cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(10):e91-e95.

11. Kansagara D, Papak J, Pasha AS, et al. Screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic liver disease: a systemic review. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(4):261-269.

12. Shah S, Shukla A, Paunipagar B. Radiological features of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2014;4(suppl 3):S63-S66.

13. You MW, Kim SY, Kim KW, et al. Recent advances in the imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2015;21(1):95-103.

14. American College of Radiology. Liver reporting and data system (LI-RADS). https://www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/Reporting-and-Data-Systems/LI-RADS. Accessed April 10, 2018.

15. Anis M. Imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma: new approaches to diagnosis. Clin Liver Dis. 2015;19(2):325-340.

16. Mitchell D, Bruix J, Sherman M, Sirlin CB. LI-RADS (Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System): summary, discussion, and consensus of the LI-RADS Management Working Group and future directions. Hepatology. 2015;61(3):1056-1065.

17. Darnell A, Forner A, Rimola J, et al. Liver imaging reporting and data system with MR imaging: evaluation in nodules 20 mm or smaller detected in cirrhosis at screening US. Radiology. 2015; 275(3):698-707.

18. Davenport MS, Khalatbari S, Liu PS, et al. Repeatability of diagnostic features and scoring systems for hepatocellular carcinoma by using MR imaging. Radiology. 2014;272(1):132-142.

19. An C, Rakhmonova G, Choi JY, Kim MJ. Liver imaging reporting and data system (LI-RADS) version 2014: understanding and application of the diagnostic algorithm. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2016;22(2):296-307.

20. Zhao W, Li W, Yi X, et al. [Diagnostic value of liver imaging reporting and data system on primary hepatocellular carcinoma] [in Chinese]. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2016;41(4):380-387.

21. Choi SH, Byun JH, Kim SY, et al. Liver imaging reporting and data system v2014 with gadoxetate disodium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging: validation of LIRADS category 4 and 5 criteria. Invest Radiol. 2016;51(8):483-490.

22. Zhang YD, Zhu FP, Xu X, et al. Liver imaging reporting and data system: substantial discordance between CT and MR for imaging classification of hepatic nodules. Acad Radiol. 2016;23(3):344-352.

23. Corwin MT, Fananapazir G, Jin M, Lamba R, Bashir MR. Difference in liver imaging and reporting data system categorization between MRI and CT. Am J Roentgenol. 2016;206(2):307-312.

Although hepatocellular carcinoma can be difficult to detect, use of the LI-RADS algorithm could lead to earlier identification in at-risk patients.

Although hepatocellular carcinoma can be difficult to detect, use of the LI-RADS algorithm could lead to earlier identification in at-risk patients.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third most common cause of death from cancer worldwide.1 Liver cancer is the fifth most common cancer in men and the seventh in women.2 The highest incidence rates are in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia where hepatitis B virus is endemic. The incidence of HCC in western countries is increasing, particularly due to the rise of hepatitis C virus (HCV) as well as alcoholic liver disease and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. The incidence of HCC has tripled in the US in the past 2 decades.1-3

HCC can be diagnosed by radiographic images without the need for biopsy if the typical imaging features are present.3 The European Association for the Study of Liver Disease (EASL) and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommend screening abdominal ultrasonography at 6-month intervals for high-risk patients.3,4 High-risk patients include patients with cirrhosis, especially those with hepatitis B or C.3

If screening ultrasonography detects a nodule, size determines whether a follow-up ultrasound is needed vs obtaining a contrast-enhanced dynamic computed tomography (CT) scan or a magnetic resonance image (MRI).3 If ultrasonography detects a nodule > 1 cm in diameter, then a dynamic CT or MRI is performed. Characteristic hyperenhancement during later arterial phase and washout during the venous or delayed phase is associated with a nearly 100% specificity for HCC diagnosis.5 Arterial-enhancing contrast is required when using CT and MRI because HCC is a hypervascular lesion.6 The portal venous blood dilutes the majority of the liver’s arterial blood; therefore, the liver does not enhance during the arterial phase, while HCC will show maximum enhancement.7 Furthermore, HCC should demonstrate a “washout” of contrast during the venous phase on CT and MRI.4 Standard imaging protocol dictates that 4 phases are needed to properly diagnose HCC including unenhanced, arterial, venous, and delayed.4

Regular surveillance increases the likelihood of detecting HCC before the presentation of clinical symptoms and facilitates receipt of curative therapy.8-10 Patients with viral hepatitis and cirrhosis with HCC found on screening are more likely to have earlier-stage disease and survive longer from the time of diagnosis.11 Furthermore, it has been observed that HCC detected by surveillance is significantly more likely to undergo curative therapy compared with incidental or symptomatic detection of HCC.9

Technical improvements in imaging techniques include advancement in contrast agents, multidetector row helical CT, and the flexibility/range of pulse sequences available in MRI.7 Even with technical improvements in all modalities used in HCC imaging, detecting HCC remains difficult, especially when detecting the small (< 2 cm) lesions in a cirrhotic liver.7 Interpretation of imaging also remains a challenge as HCC does not always fit strict criteria: lack of “washout” in a hypervascular lesion, determining small HCC lesions from benign nodules, and hypovascular/isovascular HCC.5 Radiologic differentials in the diagnosis of HCC include transient hepatic intensity difference (THID)/transient hepatic attenuation difference (THAD), arterio-portal shunt, and regenerative nodules.12 In the common clinical setting, patients undergo multiple imaging studies that are interpreted by multiple radiologists, which can add to the difficulty in the diagnosis of HCC.13

The radiology community recognized the inconsistencies and complexities of HCC imaging. Therefore, the American College of Radiology endorsed the Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System (LI-RADS), which had the goal of reducing variability in lesion interpretation through standardization and improving communication with clinicians.14 LI-RADS uses a diagnostic algorithm for CT and MRI that categorizes observed liver findings in high-risk individuals based on the probability or relative risk of HCC without assigning a formal diagnosis.14 LI-RADS takes into account arterial phase enhancement, tumor size, washout appearance, the presence and nature of a capsule, and threshold growth.15 LI-RADS categorizes an observed liver finding on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 corresponding to a definitely benign finding and 5 with definitive HCC.14 Furthermore, LI-RADS sought to limit the technical variabilities among institutions.

LI-RADS was launched in 2011 and has been utilized by many clinical practices while continuing to be expanded and updated.16 Recent studies examined the specificity of LI-RADS as well as interreader variability.17,18 For nodules viewed on MRI, both LI-RADS categories 4 and 5 had high specificity for HCC.17 When looking at interreader repeatability, LI-RADS showed moderate agreement among experts using the diagnostic algorithm.19 Further studies have compared LI-RADS with the AASLD guidelines and the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) guidelines.16 When compared with other guidelines, LI-RADS expands the definition of indeterminate findings into probably benign, intermediate probability of HCC, and probably HCC, which corresponds to LI-RADS categories 2, 3, and 4.16

We looked retrospectively at a group of patients previously diagnosed with HCC to see whether utilizing the LI-RADS scoring system within our screening system might have allowed an earlier prediction of HCC and a timelier intervention. Prior to this investigation the LI-RADS system was not used for HCC screening at our US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facility. We examined screened patients at the Memphis VA Medical Center (MVAMC) in Tennessee who were subsequently diagnosed with HCC to see which LI-RADS category the last surveillance CT prior to diagnosis would fall into, 6 months to a year prior to the diagnosis of HCC. Our control population was a group of patients screened with CT for their liver nodules who were found not to have HCC.

Methods

Patients at MVAMC with cirrhosis and patients with chronic hepatitis B are routinely screened with ultrasound, CT, or MRI in accordance with the AASLD, EASL, and VA guidelines. Of 303 patients with HCV and cirrhosis under care in 2015, 242 (81%) received imaging to screen for HCC according to the VA National Hepatitis C Registry 2015 (Personal Communication, Population Health Service, Office of Patient Care Services).The LI-RADS scoring system was not applied as a standard screening methodology.

Under an institutional review board-approved protocol, we reviewed the charts of all patients diagnosed with HCC at MVAMC from 2009 to 2014, utilizing ICD-9 code of 155.0 for HCC. We identified within these charts patients who had a surveillance CT image performed within a 6- to 13-month period prior to the CTs that diagnosed HCC (prediagnostic HCC CT). Furthermore, we reviewed the charts of all patients diagnosed with benign liver nodules at MVAMC from 2009 to 2014, utilizing the ICD-9 code of 573.8 for other specified disorders of the liver.

Within these charts, we found patients who had a surveillance CT image performed and who were followed after that image with additional imaging for ≥ 2 years or who had a liver biopsy negative for HCC (benign surveillance CT). We compared these 2 sets of CTs utilizing LI-RADS criteria. Once these patients were identified, a list of the CTs to be examined were given to 2 MVAMC radiologists who specialize in CT.

No identifying information of the patients was included, and a 13-digit number unique to each CT exam identified the CTs to be reviewed. Radiologist 1 and 2 examined the CTs on the MVAMC Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS). Both radiologists were asked to give each nodule a score according to LI-RADS v2014 diagnostic algorithm (Figure).

We hypothesized that the prediagnostic CT images of patients eventually determined to have HCC would have a LI-RADS score of 4 (LR4) or LR5. Furthermore, we hypothesized that the CT images of the benign liver nodule patients would have a score ≤ LR3. If there was a disagreement between the radiologists in terms of a malignant score (LR4 or LR5) vs a benign score (≤ LR3), then a third radiologist (radiologist 3) provided a score for these nodules. The third, tiebreaker radiologist was given the scores of both prior radiologists and asked to choose which score was correct.

Statistical analysis was then applied to the data to determine the sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy in diagnosing eventual HCC, as well as the false-negative and false-positive rates of radiologists 1 and 2. Raw data also were used to determine the agreement between raters by calculating the κ statistic with a 95% CI.

Results

A total of 70 nodules were examined by radiologists 1 and 2 with 42 of the nodules in the prediagnostic HCC CTs and 28 of the nodules in the benign surveillance CTs.

Radiologist 1 identified 11 patients with LR4 and 21 patients with LR5. His scores showed a sensitivity of 64.3% and specificity of 82.1% with accuracy of 71.4% for LI-RADS in identifying eventual HCC. The false-negative rate of the LI-RADS diagnostic algorithm for radiologist 1 was 35.7% and the false-positive rate was 17.9%. Radiologist 2 identified 17 patients LR4 and 19 patients with LR5. Radiologist 2’s scores showed a sensitivity of 69.0% and specificity of 75.0% with accuracy of 71.4% for LI-RADS in identifying eventual HCC.The false-negative rate of the LI-RADS diagnostic algorithm for radiologist 2 was 31.0% and false-positive rate of 25.0%. The κ statistic was calculated to determine the interrater agreement. The radiologists agreed on 58 of 70 samples; 15 without HCC and 43 with HCC. The κ statistic was 0.592, which indicates moderate agreement (Table 2).

Discussion

If HCC is diagnosed late in the disease process based on symptomatology and not on surveillance imaging, the likelihood of receiving early and potential curative therapy greatly declines as was shown in a systemic literature review.9 Surveillance imaging and lesion interpretation by various radiologists has been difficult to standardize as new technologic advances continue to occur in the imaging of HCC.14 LI-RADS was initiated to help standardize CT and MRI interpretation and reporting of hepatic nodules. As a dynamic algorithm, it continues to adjust with new advances in imaging techniques with the most recent updates being made to the algorithm in 2014.14,19 LI-RADS applies to patients at high risk for HCC most often who are already enrolled in a surveillance program.19 The MVAMC has a high incidence of patients with cirrhosis who are at risk for HCC, which is why we chose it as our study population.

LI-RADS can be applied to both MRI and CT imaging. Much of the recent literature have looked at LI-RADS in terms of MRI. A group in China looked at 100 pathologically confirmed patients and assigned a LI-RADS score to the MRI at the time of diagnosis and showed that MRI LI-RADS scoring was highly sensitive and specific in the diagnosis of HCC.20 This study did note a numeric difference in the specificity of LI-RADS algorithm depending on how LR3 scores were viewed. If a LR3 score was considered negative rather than positive for HCC, then the specificity increased by almost 20%.20

Another study looked at patients with liver nodules ≤ 20 mm found on ultrasound and obtained MRIs and biopsies on these patients, assigning the MRI a LI-RADs score.17 Darnell and colleagues found that MRI LR4 and LR5 have a high specificity for HCC. However, 29 of the 42 LR3 lesions examined were found to be HCC.17 Furthermore, Choi and colleagues retrospectively looked at patients in a HCC surveillance program who had undergone MRI as part of the program and assigned LI-RADS scores to these MRIs.21 Their study showed that LR5 criteria on gadoxetate disodium-enhanced MRI has excellent positive predictive value (PPV) for diagnosing HCC, and LR4 showed good PPV.21

In our study, we chose to look at LI-RADS in terms of surveillance CT scans 6 to 13 months prior to the diagnosis of HCC to see whether this method would allow us to intervene earlier with more aggressive diagnostics or therapy in those suspected of having HCC. Although Choi and colleagues looked retrospectively at MRI surveillance imaging, most of the prior studies have looked at LI-RADS scoring in imaging at the time of diagnosis.17,20,21 By looking at surveillance CT scans, we sought to determine LI-RADS sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy as a screening tool compared with CT evaluations without LI-RADS scoring.

We also chose to look at CT scans since most of the prior studies have looked at the more detailed and often more expensive MRIs. For both radiologists 1 and 2, the sensitivity was > 60% and specificity was > 70% with a diagnostic accuracy of 71.4% in predicting a diagnosis of HCC in future scans. Although there was high false negative of > 30% for both radiologists, we did consider LR3 as negative for HCC. As Darnell and colleagues’ study of MRI LI-RADS shows, LR3 may need to be revised in the future as its ambiguity can lead to false-negatives.17 Our results also showed moderate interreader agreement, which has been seen in previous studies with LI-RADS.18

Some studies have compared MRI with CT imaging in terms of LI-RADs classification of hepatic nodules to find out whether concordance was seen.22,23 Both studies found that there was substantial discordance between MRI and CT with CT often underscoring hepatic nodules.22,23 In Zhang and colleagues, interclass agreement between CT and MRI varied the most in terms of arterial enhancement with CT producing false-negative findings.22 CT also underestimated LI-RADS score by 16.9% for LR3, 37.3% for LR4, and 8.5% for LR5 in this study.22 Furthermore, Corwin and colleagues found a significant upgrade in terms of LI-RADS categorization with MRI for 42.5% of observations.23 In this study, upgraded LI-RADS scores on MRI included 2 upgraded to LR5V (Figure), 15 upgraded to LR5, and 12 upgraded to LR4.23

Our study shows that the LI-RADS algorithm has a good sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy as a screening tool, predicting HCC in scans earlier than standard CT evaluation. In our study, the patients with HCC were shown to have higher LI-RADS scores on prediagnostic imaging, while the benign liver nodule patients were shown to have lower LI-RADS scores. This data would suggest that a LI-RADS score given to surveillance CT of LR4 or higher should recommend either a biopsy or follow-up imaging after a short interval. If LI-RADS is applied to surveillance CTs in patients at risk for HCC, a diagnosis of HCC may be arrived at earlier as compared with not using the LI-RADS algorithm. Earlier detection may lead to earlier intervention and improved treatment outcomes.

Limitations

Limitations to our study occurred because radiologist 3 did not review all of the images nor score them. Radiologist 3 was limited to 12 images where there was disagreement and was limited to 2 scores to choose from for each image. Further limitations include that this study was performed at a single center. Our study focused on one imaging modality and did not include ultrasounds or MRIs. We did not compare the demographics of our patients with those of other VA hospitals. The radiologists interpreted the images individually, and their subjectivity was another limitation.

Conclusion

In the MVAMC population, LI-RADS showed a good sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy for CT surveillance scans in patient at high risk for HCC at an earlier time point than did standard evaluation by very experienced CT radiologists. Higher LI-RADS scores on surveillance CTs had good diagnostic accuracy for the probable future diagnosis of HCC, whereas lower LI-RADS scores had a good diagnostic accuracy for probable benign nodules. Utilizing the LI-RADS algorithm on all surveillance CTs in patients at high risk for HCC may lead to obtaining MRIs or follow-up CTs sooner for suspicious nodules, leading to an earlier diagnosis of HCC and possible earlier and more effective intervention.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third most common cause of death from cancer worldwide.1 Liver cancer is the fifth most common cancer in men and the seventh in women.2 The highest incidence rates are in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia where hepatitis B virus is endemic. The incidence of HCC in western countries is increasing, particularly due to the rise of hepatitis C virus (HCV) as well as alcoholic liver disease and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. The incidence of HCC has tripled in the US in the past 2 decades.1-3

HCC can be diagnosed by radiographic images without the need for biopsy if the typical imaging features are present.3 The European Association for the Study of Liver Disease (EASL) and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommend screening abdominal ultrasonography at 6-month intervals for high-risk patients.3,4 High-risk patients include patients with cirrhosis, especially those with hepatitis B or C.3

If screening ultrasonography detects a nodule, size determines whether a follow-up ultrasound is needed vs obtaining a contrast-enhanced dynamic computed tomography (CT) scan or a magnetic resonance image (MRI).3 If ultrasonography detects a nodule > 1 cm in diameter, then a dynamic CT or MRI is performed. Characteristic hyperenhancement during later arterial phase and washout during the venous or delayed phase is associated with a nearly 100% specificity for HCC diagnosis.5 Arterial-enhancing contrast is required when using CT and MRI because HCC is a hypervascular lesion.6 The portal venous blood dilutes the majority of the liver’s arterial blood; therefore, the liver does not enhance during the arterial phase, while HCC will show maximum enhancement.7 Furthermore, HCC should demonstrate a “washout” of contrast during the venous phase on CT and MRI.4 Standard imaging protocol dictates that 4 phases are needed to properly diagnose HCC including unenhanced, arterial, venous, and delayed.4

Regular surveillance increases the likelihood of detecting HCC before the presentation of clinical symptoms and facilitates receipt of curative therapy.8-10 Patients with viral hepatitis and cirrhosis with HCC found on screening are more likely to have earlier-stage disease and survive longer from the time of diagnosis.11 Furthermore, it has been observed that HCC detected by surveillance is significantly more likely to undergo curative therapy compared with incidental or symptomatic detection of HCC.9

Technical improvements in imaging techniques include advancement in contrast agents, multidetector row helical CT, and the flexibility/range of pulse sequences available in MRI.7 Even with technical improvements in all modalities used in HCC imaging, detecting HCC remains difficult, especially when detecting the small (< 2 cm) lesions in a cirrhotic liver.7 Interpretation of imaging also remains a challenge as HCC does not always fit strict criteria: lack of “washout” in a hypervascular lesion, determining small HCC lesions from benign nodules, and hypovascular/isovascular HCC.5 Radiologic differentials in the diagnosis of HCC include transient hepatic intensity difference (THID)/transient hepatic attenuation difference (THAD), arterio-portal shunt, and regenerative nodules.12 In the common clinical setting, patients undergo multiple imaging studies that are interpreted by multiple radiologists, which can add to the difficulty in the diagnosis of HCC.13

The radiology community recognized the inconsistencies and complexities of HCC imaging. Therefore, the American College of Radiology endorsed the Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System (LI-RADS), which had the goal of reducing variability in lesion interpretation through standardization and improving communication with clinicians.14 LI-RADS uses a diagnostic algorithm for CT and MRI that categorizes observed liver findings in high-risk individuals based on the probability or relative risk of HCC without assigning a formal diagnosis.14 LI-RADS takes into account arterial phase enhancement, tumor size, washout appearance, the presence and nature of a capsule, and threshold growth.15 LI-RADS categorizes an observed liver finding on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 corresponding to a definitely benign finding and 5 with definitive HCC.14 Furthermore, LI-RADS sought to limit the technical variabilities among institutions.

LI-RADS was launched in 2011 and has been utilized by many clinical practices while continuing to be expanded and updated.16 Recent studies examined the specificity of LI-RADS as well as interreader variability.17,18 For nodules viewed on MRI, both LI-RADS categories 4 and 5 had high specificity for HCC.17 When looking at interreader repeatability, LI-RADS showed moderate agreement among experts using the diagnostic algorithm.19 Further studies have compared LI-RADS with the AASLD guidelines and the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) guidelines.16 When compared with other guidelines, LI-RADS expands the definition of indeterminate findings into probably benign, intermediate probability of HCC, and probably HCC, which corresponds to LI-RADS categories 2, 3, and 4.16

We looked retrospectively at a group of patients previously diagnosed with HCC to see whether utilizing the LI-RADS scoring system within our screening system might have allowed an earlier prediction of HCC and a timelier intervention. Prior to this investigation the LI-RADS system was not used for HCC screening at our US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facility. We examined screened patients at the Memphis VA Medical Center (MVAMC) in Tennessee who were subsequently diagnosed with HCC to see which LI-RADS category the last surveillance CT prior to diagnosis would fall into, 6 months to a year prior to the diagnosis of HCC. Our control population was a group of patients screened with CT for their liver nodules who were found not to have HCC.

Methods

Patients at MVAMC with cirrhosis and patients with chronic hepatitis B are routinely screened with ultrasound, CT, or MRI in accordance with the AASLD, EASL, and VA guidelines. Of 303 patients with HCV and cirrhosis under care in 2015, 242 (81%) received imaging to screen for HCC according to the VA National Hepatitis C Registry 2015 (Personal Communication, Population Health Service, Office of Patient Care Services).The LI-RADS scoring system was not applied as a standard screening methodology.

Under an institutional review board-approved protocol, we reviewed the charts of all patients diagnosed with HCC at MVAMC from 2009 to 2014, utilizing ICD-9 code of 155.0 for HCC. We identified within these charts patients who had a surveillance CT image performed within a 6- to 13-month period prior to the CTs that diagnosed HCC (prediagnostic HCC CT). Furthermore, we reviewed the charts of all patients diagnosed with benign liver nodules at MVAMC from 2009 to 2014, utilizing the ICD-9 code of 573.8 for other specified disorders of the liver.

Within these charts, we found patients who had a surveillance CT image performed and who were followed after that image with additional imaging for ≥ 2 years or who had a liver biopsy negative for HCC (benign surveillance CT). We compared these 2 sets of CTs utilizing LI-RADS criteria. Once these patients were identified, a list of the CTs to be examined were given to 2 MVAMC radiologists who specialize in CT.

No identifying information of the patients was included, and a 13-digit number unique to each CT exam identified the CTs to be reviewed. Radiologist 1 and 2 examined the CTs on the MVAMC Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS). Both radiologists were asked to give each nodule a score according to LI-RADS v2014 diagnostic algorithm (Figure).

We hypothesized that the prediagnostic CT images of patients eventually determined to have HCC would have a LI-RADS score of 4 (LR4) or LR5. Furthermore, we hypothesized that the CT images of the benign liver nodule patients would have a score ≤ LR3. If there was a disagreement between the radiologists in terms of a malignant score (LR4 or LR5) vs a benign score (≤ LR3), then a third radiologist (radiologist 3) provided a score for these nodules. The third, tiebreaker radiologist was given the scores of both prior radiologists and asked to choose which score was correct.

Statistical analysis was then applied to the data to determine the sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy in diagnosing eventual HCC, as well as the false-negative and false-positive rates of radiologists 1 and 2. Raw data also were used to determine the agreement between raters by calculating the κ statistic with a 95% CI.

Results

A total of 70 nodules were examined by radiologists 1 and 2 with 42 of the nodules in the prediagnostic HCC CTs and 28 of the nodules in the benign surveillance CTs.

Radiologist 1 identified 11 patients with LR4 and 21 patients with LR5. His scores showed a sensitivity of 64.3% and specificity of 82.1% with accuracy of 71.4% for LI-RADS in identifying eventual HCC. The false-negative rate of the LI-RADS diagnostic algorithm for radiologist 1 was 35.7% and the false-positive rate was 17.9%. Radiologist 2 identified 17 patients LR4 and 19 patients with LR5. Radiologist 2’s scores showed a sensitivity of 69.0% and specificity of 75.0% with accuracy of 71.4% for LI-RADS in identifying eventual HCC.The false-negative rate of the LI-RADS diagnostic algorithm for radiologist 2 was 31.0% and false-positive rate of 25.0%. The κ statistic was calculated to determine the interrater agreement. The radiologists agreed on 58 of 70 samples; 15 without HCC and 43 with HCC. The κ statistic was 0.592, which indicates moderate agreement (Table 2).

Discussion

If HCC is diagnosed late in the disease process based on symptomatology and not on surveillance imaging, the likelihood of receiving early and potential curative therapy greatly declines as was shown in a systemic literature review.9 Surveillance imaging and lesion interpretation by various radiologists has been difficult to standardize as new technologic advances continue to occur in the imaging of HCC.14 LI-RADS was initiated to help standardize CT and MRI interpretation and reporting of hepatic nodules. As a dynamic algorithm, it continues to adjust with new advances in imaging techniques with the most recent updates being made to the algorithm in 2014.14,19 LI-RADS applies to patients at high risk for HCC most often who are already enrolled in a surveillance program.19 The MVAMC has a high incidence of patients with cirrhosis who are at risk for HCC, which is why we chose it as our study population.

LI-RADS can be applied to both MRI and CT imaging. Much of the recent literature have looked at LI-RADS in terms of MRI. A group in China looked at 100 pathologically confirmed patients and assigned a LI-RADS score to the MRI at the time of diagnosis and showed that MRI LI-RADS scoring was highly sensitive and specific in the diagnosis of HCC.20 This study did note a numeric difference in the specificity of LI-RADS algorithm depending on how LR3 scores were viewed. If a LR3 score was considered negative rather than positive for HCC, then the specificity increased by almost 20%.20

Another study looked at patients with liver nodules ≤ 20 mm found on ultrasound and obtained MRIs and biopsies on these patients, assigning the MRI a LI-RADs score.17 Darnell and colleagues found that MRI LR4 and LR5 have a high specificity for HCC. However, 29 of the 42 LR3 lesions examined were found to be HCC.17 Furthermore, Choi and colleagues retrospectively looked at patients in a HCC surveillance program who had undergone MRI as part of the program and assigned LI-RADS scores to these MRIs.21 Their study showed that LR5 criteria on gadoxetate disodium-enhanced MRI has excellent positive predictive value (PPV) for diagnosing HCC, and LR4 showed good PPV.21

In our study, we chose to look at LI-RADS in terms of surveillance CT scans 6 to 13 months prior to the diagnosis of HCC to see whether this method would allow us to intervene earlier with more aggressive diagnostics or therapy in those suspected of having HCC. Although Choi and colleagues looked retrospectively at MRI surveillance imaging, most of the prior studies have looked at LI-RADS scoring in imaging at the time of diagnosis.17,20,21 By looking at surveillance CT scans, we sought to determine LI-RADS sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy as a screening tool compared with CT evaluations without LI-RADS scoring.

We also chose to look at CT scans since most of the prior studies have looked at the more detailed and often more expensive MRIs. For both radiologists 1 and 2, the sensitivity was > 60% and specificity was > 70% with a diagnostic accuracy of 71.4% in predicting a diagnosis of HCC in future scans. Although there was high false negative of > 30% for both radiologists, we did consider LR3 as negative for HCC. As Darnell and colleagues’ study of MRI LI-RADS shows, LR3 may need to be revised in the future as its ambiguity can lead to false-negatives.17 Our results also showed moderate interreader agreement, which has been seen in previous studies with LI-RADS.18

Some studies have compared MRI with CT imaging in terms of LI-RADs classification of hepatic nodules to find out whether concordance was seen.22,23 Both studies found that there was substantial discordance between MRI and CT with CT often underscoring hepatic nodules.22,23 In Zhang and colleagues, interclass agreement between CT and MRI varied the most in terms of arterial enhancement with CT producing false-negative findings.22 CT also underestimated LI-RADS score by 16.9% for LR3, 37.3% for LR4, and 8.5% for LR5 in this study.22 Furthermore, Corwin and colleagues found a significant upgrade in terms of LI-RADS categorization with MRI for 42.5% of observations.23 In this study, upgraded LI-RADS scores on MRI included 2 upgraded to LR5V (Figure), 15 upgraded to LR5, and 12 upgraded to LR4.23

Our study shows that the LI-RADS algorithm has a good sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy as a screening tool, predicting HCC in scans earlier than standard CT evaluation. In our study, the patients with HCC were shown to have higher LI-RADS scores on prediagnostic imaging, while the benign liver nodule patients were shown to have lower LI-RADS scores. This data would suggest that a LI-RADS score given to surveillance CT of LR4 or higher should recommend either a biopsy or follow-up imaging after a short interval. If LI-RADS is applied to surveillance CTs in patients at risk for HCC, a diagnosis of HCC may be arrived at earlier as compared with not using the LI-RADS algorithm. Earlier detection may lead to earlier intervention and improved treatment outcomes.

Limitations

Limitations to our study occurred because radiologist 3 did not review all of the images nor score them. Radiologist 3 was limited to 12 images where there was disagreement and was limited to 2 scores to choose from for each image. Further limitations include that this study was performed at a single center. Our study focused on one imaging modality and did not include ultrasounds or MRIs. We did not compare the demographics of our patients with those of other VA hospitals. The radiologists interpreted the images individually, and their subjectivity was another limitation.

Conclusion

In the MVAMC population, LI-RADS showed a good sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy for CT surveillance scans in patient at high risk for HCC at an earlier time point than did standard evaluation by very experienced CT radiologists. Higher LI-RADS scores on surveillance CTs had good diagnostic accuracy for the probable future diagnosis of HCC, whereas lower LI-RADS scores had a good diagnostic accuracy for probable benign nodules. Utilizing the LI-RADS algorithm on all surveillance CTs in patients at high risk for HCC may lead to obtaining MRIs or follow-up CTs sooner for suspicious nodules, leading to an earlier diagnosis of HCC and possible earlier and more effective intervention.

1. El–Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(7):2557-2576.

2. El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1118-1127.

3. Bruix J, Sherman M; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53(3):1020-1022.

4. Selvapatt N, House H, Brown A. Hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance: are we utilizing it? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50(1):e8-e12.

5. Lee JM, Yoon JH, Joo I, Woo HS. Recent advances in CT and MR imaging for evaluation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2012;1(1):22-40.

6. Chou R, Cuevas C, Fu R, et al. Imaging techniques for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(10):697-711.

7. Ariff B, Lloyd CR, Khan S, et al. Imaging of liver cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(11):1289-1300.

8. Yuen MF, Cheng CC, Lauder IJ, Lam SK, Ooi CG, Lai CL. Early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma increases the chance of treatment: Hong Kong experience. Hepatology. 2000;31(2):330-335.

9. Singal AG, Pillai A, Tiro J. Early detection, curative treatment, and survival rates for hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in patients with cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11(4):e1001624.

10. Nusbaum, JD, Smirniotopoulos J, Wright HC, et al. The effect of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in an urban population with liver cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(10):e91-e95.

11. Kansagara D, Papak J, Pasha AS, et al. Screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic liver disease: a systemic review. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(4):261-269.

12. Shah S, Shukla A, Paunipagar B. Radiological features of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2014;4(suppl 3):S63-S66.

13. You MW, Kim SY, Kim KW, et al. Recent advances in the imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2015;21(1):95-103.

14. American College of Radiology. Liver reporting and data system (LI-RADS). https://www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/Reporting-and-Data-Systems/LI-RADS. Accessed April 10, 2018.

15. Anis M. Imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma: new approaches to diagnosis. Clin Liver Dis. 2015;19(2):325-340.

16. Mitchell D, Bruix J, Sherman M, Sirlin CB. LI-RADS (Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System): summary, discussion, and consensus of the LI-RADS Management Working Group and future directions. Hepatology. 2015;61(3):1056-1065.

17. Darnell A, Forner A, Rimola J, et al. Liver imaging reporting and data system with MR imaging: evaluation in nodules 20 mm or smaller detected in cirrhosis at screening US. Radiology. 2015; 275(3):698-707.

18. Davenport MS, Khalatbari S, Liu PS, et al. Repeatability of diagnostic features and scoring systems for hepatocellular carcinoma by using MR imaging. Radiology. 2014;272(1):132-142.

19. An C, Rakhmonova G, Choi JY, Kim MJ. Liver imaging reporting and data system (LI-RADS) version 2014: understanding and application of the diagnostic algorithm. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2016;22(2):296-307.

20. Zhao W, Li W, Yi X, et al. [Diagnostic value of liver imaging reporting and data system on primary hepatocellular carcinoma] [in Chinese]. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2016;41(4):380-387.

21. Choi SH, Byun JH, Kim SY, et al. Liver imaging reporting and data system v2014 with gadoxetate disodium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging: validation of LIRADS category 4 and 5 criteria. Invest Radiol. 2016;51(8):483-490.

22. Zhang YD, Zhu FP, Xu X, et al. Liver imaging reporting and data system: substantial discordance between CT and MR for imaging classification of hepatic nodules. Acad Radiol. 2016;23(3):344-352.

23. Corwin MT, Fananapazir G, Jin M, Lamba R, Bashir MR. Difference in liver imaging and reporting data system categorization between MRI and CT. Am J Roentgenol. 2016;206(2):307-312.

1. El–Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(7):2557-2576.

2. El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1118-1127.

3. Bruix J, Sherman M; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53(3):1020-1022.

4. Selvapatt N, House H, Brown A. Hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance: are we utilizing it? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50(1):e8-e12.

5. Lee JM, Yoon JH, Joo I, Woo HS. Recent advances in CT and MR imaging for evaluation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2012;1(1):22-40.

6. Chou R, Cuevas C, Fu R, et al. Imaging techniques for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(10):697-711.

7. Ariff B, Lloyd CR, Khan S, et al. Imaging of liver cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(11):1289-1300.

8. Yuen MF, Cheng CC, Lauder IJ, Lam SK, Ooi CG, Lai CL. Early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma increases the chance of treatment: Hong Kong experience. Hepatology. 2000;31(2):330-335.

9. Singal AG, Pillai A, Tiro J. Early detection, curative treatment, and survival rates for hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in patients with cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11(4):e1001624.

10. Nusbaum, JD, Smirniotopoulos J, Wright HC, et al. The effect of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in an urban population with liver cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(10):e91-e95.

11. Kansagara D, Papak J, Pasha AS, et al. Screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic liver disease: a systemic review. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(4):261-269.

12. Shah S, Shukla A, Paunipagar B. Radiological features of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2014;4(suppl 3):S63-S66.

13. You MW, Kim SY, Kim KW, et al. Recent advances in the imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2015;21(1):95-103.

14. American College of Radiology. Liver reporting and data system (LI-RADS). https://www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/Reporting-and-Data-Systems/LI-RADS. Accessed April 10, 2018.

15. Anis M. Imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma: new approaches to diagnosis. Clin Liver Dis. 2015;19(2):325-340.

16. Mitchell D, Bruix J, Sherman M, Sirlin CB. LI-RADS (Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System): summary, discussion, and consensus of the LI-RADS Management Working Group and future directions. Hepatology. 2015;61(3):1056-1065.

17. Darnell A, Forner A, Rimola J, et al. Liver imaging reporting and data system with MR imaging: evaluation in nodules 20 mm or smaller detected in cirrhosis at screening US. Radiology. 2015; 275(3):698-707.

18. Davenport MS, Khalatbari S, Liu PS, et al. Repeatability of diagnostic features and scoring systems for hepatocellular carcinoma by using MR imaging. Radiology. 2014;272(1):132-142.

19. An C, Rakhmonova G, Choi JY, Kim MJ. Liver imaging reporting and data system (LI-RADS) version 2014: understanding and application of the diagnostic algorithm. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2016;22(2):296-307.

20. Zhao W, Li W, Yi X, et al. [Diagnostic value of liver imaging reporting and data system on primary hepatocellular carcinoma] [in Chinese]. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2016;41(4):380-387.

21. Choi SH, Byun JH, Kim SY, et al. Liver imaging reporting and data system v2014 with gadoxetate disodium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging: validation of LIRADS category 4 and 5 criteria. Invest Radiol. 2016;51(8):483-490.

22. Zhang YD, Zhu FP, Xu X, et al. Liver imaging reporting and data system: substantial discordance between CT and MR for imaging classification of hepatic nodules. Acad Radiol. 2016;23(3):344-352.

23. Corwin MT, Fananapazir G, Jin M, Lamba R, Bashir MR. Difference in liver imaging and reporting data system categorization between MRI and CT. Am J Roentgenol. 2016;206(2):307-312.