User login

The Effect of Race on Outcomes in Veterans With Hepatocellular Carcinoma at a Single Center

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common and third most deadly malignancy worldwide, carrying a mean survival rate without treatment of 6 to 20 months depending on stage.1 Fifty-seven percent of patients with liver cancer are diagnosed with regional or distant metastatic disease that carries 5-year relative survival rates of 10.7% and 3.1%, respectively.2 HCC arises most commonly from liver cirrhosis due to chronic hepatocyte injury, which may be mediated by viral hepatitis, alcoholism, and metabolic disease. Other less common causes include autoimmune disease, exposure to environmental hazards, and certain genetic diseases, such as α-1 antitrypsin deficiency and Wilson disease.

Multiple staging systems for HCC exist that incorporate some variation of the following features: size and invasion of the tumor, distant metastases, and liver function. Stage-directed treatments for HCC include ablation, embolization, resection, transplant, and systemic therapy, such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors, immunotherapies, and monoclonal antibodies. In addition to tumor/node/metastasis (TNM) staging, α-fetoprotein (AFP) is a diagnostic marker with prognostic value in HCC with higher levels correlating to higher tumor burden and a worse prognosis. With treatment, the 5-year survival rate for early stage HCC ranges from 60% to 80% but decreases significantly with higher stages.1 HCC screening in at-risk populations has accounted for > 40% of diagnoses since the practice became widely adopted, and earlier recognition has led to an improvement in survival even when adjusting for lead time bias.3

Systemic therapy for advanced disease continues to improve. Sorafenib remained the standard first-line systemic therapy since it was introduced in 2008.4 First-line therapy improved with immunotherapies. The phase 3 IMBrave150 trial comparing atezolizumab plus bevacizumab to sorafenib showed a median overall survival (OS) > 19 months with 7.7% of patients achieving a complete response.5 HIMALAYA, another phase 3 trial set for publication later this year, also reported promising results when a priming dose of the CTLA-4 inhibitor tremelimumab followed by durvalumab was compared with sorafenib.6

There has been a rise in incidence of HCC in the United States across all races and ethnicities, though Black, Hispanic, and Asian patients remain disproportionately affected. Subsequently, identifying causative biologic, socioeconomic, and cultural factors, as well as implicit bias in health care continues to be a topic of great interest.7-9 Using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data, a number of large studies have found that Black patients with HCC were more likely to present with an advanced stage, less likely to receive curative intent treatment, and had significantly reduced survival compared with that of White patients.1,7-9 An analysis of 1117 patients by Rich and colleagues noted a 34% increased risk of death for Black patients with HCC compared with that of White patients, and other studies have shown about a 50% reduction in rate of liver transplantation for Black patients.10-12 Our study aimed to investigate potential disparities in incidence, etiology, AFP level at diagnosis, and outcomes of HCC in Black and White veterans managed at the Memphis Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Tennessee.

Methods

A single center retrospective chart review was conducted at the Memphis VAMC using the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code C22.0 for HCC. Initial results were manually refined by prespecified criteria. Patients were included if they were diagnosed with HCC and received HCC treatment at the Memphis VAMC. Patients were excluded if HCC was not diagnosed histologically or clinically by imaging characteristics and AFP level, if the patient’s primary treatment was not provided at the Memphis VAMC, if they were lost to follow-up, or if race was not specified as either Black or White.

The following patient variables were examined: age, sex, comorbidities (alcohol or substance use disorder, cirrhosis, HIV), tumor stage, AFP, method of diagnosis, first-line treatments, systemic treatment, surgical options offered, and mortality. Staging was based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM staging for HCC.13 Surgical options were recorded as resection or transplant. Patients who were offered treatment but lost to follow-up were excluded from the analysis.

Data Analysis

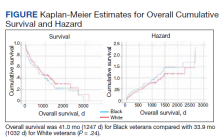

Our primary endpoint was identifying differences in OS among Memphis VAMC patients with HCC related to race. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to investigate differences in OS and cumulative hazard ratio (HR) for death. Cox regression multivariate analysis further evaluated discrepancies among investigated patient variables, including age, race, alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drug use, HIV coinfection, and cirrhosis. Treatment factors were further defined by first-line treatment, systemic therapy, surgical resection, and transplant. χ2 analysis was used to investigate differences in treatment modalities.

Results

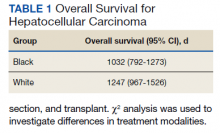

We identified 227 veterans, 95 Black and 132 White, between 2009 and 2021 meeting criteria for primary HCC treated at the Memphis VAMC. This study did not show a significant difference in OS between White and Black veterans (P = .24). Kaplan-Meier assessment showed OS was 1247 days (41 months) for Black veterans compared with 1032 days (34 months) for White veterans (Figure; Table 1).

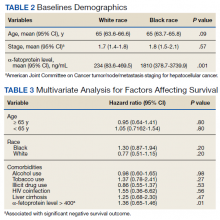

Additionally, no significant difference was found between veterans for age or stage at diagnosis when stratified by race. The mean age of diagnosis for both groups was 65 years (P = .09). The mean TNM staging was 1.7 for White veterans vs 1.8 for Black veterans (P = .57). There was a significant increase in the AFP level at diagnosis for Black veterans (P = .001) (Table 2).

The most common initial treatment for both groups was transarterial chemoembolization and radiofrequency ablation with 68% of White and 64% of Black veterans receiving this therapy. There was no significant difference between who received systemic therapy.

However, we found significant differences by race for some forms of treatment. In our analysis, significant differences existed between those who did not receive any form of treatment as well as who received surgical resection and transplant. Among Black veterans, 11.6% received no treatment vs 6.1% for White veterans (P = .001). Only 2.1% of Black veterans underwent surgical resection vs 8.3% of White veterans (P = .046). Similarly, 13 (9.8%) White veterans vs 3 (3.2%) Black veterans received orthotopic liver transplantation (P = .052) in our cohort (eAppendix available at doi:10.12788/fp.0304). We found no differences in patient characteristics affecting OS, including alcohol use, tobacco use, illicit drug use, HIV coinfection, or liver cirrhosis (Table 3).

Discussion

In this retrospective analysis, Black veterans with HCC did not experience a statistically significant decrease in OS compared with that of White veterans despite some differences in therapy offered. Other studies have found that surgery was less frequently recommended to Black patients across multiple cancer types, and in most cases this carried a negative impact on OS.8,10,11,14,15 A number of other studies have demonstrated a greater percentage of Black patients receiving no treatment, although these studies are often based on SEER data, which captures only cancer-directed surgery and no other methods of treatment. Inequities in patient factors like insurance and socioeconomic status as well as willingness to receive certain treatments are often cited as major influences in health care disparities, but systemic and clinician factors like hospital volume, clinician expertise, specialist availability, and implicit racial bias all affect outcomes.16 One benefit of our study was that CPRS provided a centralized recording of all treatments received. Interestingly, the treatment discrepancy in our study was not attributable to a statistically significant difference in tumor stage at presentation. There should be no misconception that US Department of Veterans Affairs patients are less affected by socioeconomic inequities, though still this suggests clinician and systemic factors were significant drivers behind our findings.

This study did not intend to determine differences in incidence of HCC by race, although many studies have shown an age-adjusted incidence of HCC among Black and Hispanic patients up to twice that of White patients.1,8-10 Notably, the rate of orthotopic liver transplantation in this study was low regardless of race compared with that of other larger studies of patients with HCC.12,15 Discrepancies in HCC care among White and Black patients have been suggested to stem from a variety of influences, including access to early diagnosis and treatment of hepatitis C virus, comorbid conditions, as well as complex socioeconomic factors. It also has been shown that oncologists’ implicit racial bias has a negative impact on patients’ perceived quality of communication, their confidence in the recommended treatment, and the understood difficulty of the treatment by the patient and should be considered as a contributor to health disparities.17,18

Studies evaluating survival in HCC using SEER data generally stratify disease by localized, regional, or distant metastasis. For our study, TNM staging provided a more accurate assessment of the disease and reduced the chances that broader staging definitions could obscure differences in treatment choices. Future studies could be improved by stratifying patients by variables impacting treatment choice, such as Child-Pugh score or Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging. Our study demonstrated a statistically significant difference in AFP level between White and Black veterans. This has been observed in prior studies as well, and while no specific cause has been identified, it suggests differences in tumor biologic features across different races. In addition, we found that an elevated AFP level at the time of diagnosis (defined as > 400) correlates with a worsened OS (HR, 1.36; P = .01).

Limitations

This study has several limitations, notably the number of veterans eligible for analysis at a single institution. A larger cohort would be needed to evaluate for statistically significant differences in outcomes by race. Additionally, our study did not account for therapy that was offered to but not pursued by the patient, and this would be useful to determine whether patient or practitioner factors were the more significant influence on the type of therapy received.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated a statistically significant difference in the rate of resection and liver transplantation between White and Black veterans at a single institution, although no difference in OS was observed. This discrepancy was not explained by differences in tumor staging. Additional, larger studies will be useful in clarifying the biologic, cultural, and socioeconomic drivers in HCC treatment and mortality.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lorri Reaves, Memphis Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Department of Hepatology.

1. Altekruse SF, McGlynn KA, Reichman ME. Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence, mortality, and survival trends in the United States from 1975 to 2005. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(9):1485-1491. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7753

2. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2012, National Cancer Institute. Accessed July 8, 2022. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2012/results_merged/sect_14_liver_bile.pdf#page=8

3. Singal AG, Mittal S, Yerokun OA, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma screening associated with early tumor detection and improved survival among patients with cirrhosis in the US. Am J Med. 2017;130(9):1099-1106.e1. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.01.021

4. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(4):378-390. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0708857

5. Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):1894-1905. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1915745

6. Abou-Alfa GK, Chan SL, Kudo M, et al. Phase 3 randomized, open-label, multicenter study of tremelimumab (T) and durvalumab (D) as first-line therapy in patients (pts) with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC): HIMALAYA. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(suppl 4):379. doi:10.1200/JCO.2022.40.4_suppl.379

7. Franco RA, Fan Y, Jarosek S, Bae S, Galbraith J. Racial and geographic disparities in hepatocellular carcinoma outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(5)(suppl 1):S40-S48. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.05.030

8. Ha J, Yan M, Aguilar M, et al. Race/ethnicity-specific disparities in hepatocellular carcinoma stage at diagnosis and its impact on receipt of curative therapies. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50(5):423-430. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000448

9. Wong R, Corley DA. Racial and ethnic variations in hepatocellular carcinoma incidence within the United States. Am J Med. 2008;121(6):525-531. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.03.005

10. Rich NE, Hester C, Odewole M, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in presentation and outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(3):551-559.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2018.05.039

11. Peters NA, Javed AA, He J, Wolfgang CL, Weiss MJ. Association of socioeconomics, surgical therapy, and survival of early stage hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Res. 2017;210:253-260. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2016.11.042

12. Wong RJ, Devaki P, Nguyen L, Cheung R, Nguyen MH. Ethnic disparities and liver transplantation rates in hepatocellular carcinoma patients in the recent era: results from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry. Liver Transpl. 2014;20(5):528-535. doi:10.1002/lt.23820

13. Minagawa M, Ikai I, Matsuyama Y, Yamaoka Y, Makuuchi M. Staging of hepatocellular carcinoma: assessment of the Japanese TNM and AJCC/UICC TNM systems in a cohort of 13,772 patients in Japan. Ann Surg. 2007;245(6):909-922. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000254368.65878.da.

14. Harrison LE, Reichman T, Koneru B, et al. Racial discrepancies in the outcome of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Arch Surg. 2004;139(9):992-996. doi:10.1001/archsurg.139.9.992

15. Sloane D, Chen H, Howell C. Racial disparity in primary hepatocellular carcinoma: tumor stage at presentation, surgical treatment and survival. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(12):1934-1939.

16. Haider AH, Scott VK, Rehman KA, et al. Racial disparities in surgical care and outcomes in the United States: a comprehensive review of patient, provider, and systemic factors. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216(3):482-92.e12. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.11.014

17. Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA, et al. The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):979-987. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300558

18. Penner LA, Dovidio JF, Gonzalez R, et al. The effects of oncologist implicit racial bias in racially discordant oncology interactions. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(24):2874-2880. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.66.3658

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common and third most deadly malignancy worldwide, carrying a mean survival rate without treatment of 6 to 20 months depending on stage.1 Fifty-seven percent of patients with liver cancer are diagnosed with regional or distant metastatic disease that carries 5-year relative survival rates of 10.7% and 3.1%, respectively.2 HCC arises most commonly from liver cirrhosis due to chronic hepatocyte injury, which may be mediated by viral hepatitis, alcoholism, and metabolic disease. Other less common causes include autoimmune disease, exposure to environmental hazards, and certain genetic diseases, such as α-1 antitrypsin deficiency and Wilson disease.

Multiple staging systems for HCC exist that incorporate some variation of the following features: size and invasion of the tumor, distant metastases, and liver function. Stage-directed treatments for HCC include ablation, embolization, resection, transplant, and systemic therapy, such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors, immunotherapies, and monoclonal antibodies. In addition to tumor/node/metastasis (TNM) staging, α-fetoprotein (AFP) is a diagnostic marker with prognostic value in HCC with higher levels correlating to higher tumor burden and a worse prognosis. With treatment, the 5-year survival rate for early stage HCC ranges from 60% to 80% but decreases significantly with higher stages.1 HCC screening in at-risk populations has accounted for > 40% of diagnoses since the practice became widely adopted, and earlier recognition has led to an improvement in survival even when adjusting for lead time bias.3

Systemic therapy for advanced disease continues to improve. Sorafenib remained the standard first-line systemic therapy since it was introduced in 2008.4 First-line therapy improved with immunotherapies. The phase 3 IMBrave150 trial comparing atezolizumab plus bevacizumab to sorafenib showed a median overall survival (OS) > 19 months with 7.7% of patients achieving a complete response.5 HIMALAYA, another phase 3 trial set for publication later this year, also reported promising results when a priming dose of the CTLA-4 inhibitor tremelimumab followed by durvalumab was compared with sorafenib.6

There has been a rise in incidence of HCC in the United States across all races and ethnicities, though Black, Hispanic, and Asian patients remain disproportionately affected. Subsequently, identifying causative biologic, socioeconomic, and cultural factors, as well as implicit bias in health care continues to be a topic of great interest.7-9 Using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data, a number of large studies have found that Black patients with HCC were more likely to present with an advanced stage, less likely to receive curative intent treatment, and had significantly reduced survival compared with that of White patients.1,7-9 An analysis of 1117 patients by Rich and colleagues noted a 34% increased risk of death for Black patients with HCC compared with that of White patients, and other studies have shown about a 50% reduction in rate of liver transplantation for Black patients.10-12 Our study aimed to investigate potential disparities in incidence, etiology, AFP level at diagnosis, and outcomes of HCC in Black and White veterans managed at the Memphis Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Tennessee.

Methods

A single center retrospective chart review was conducted at the Memphis VAMC using the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code C22.0 for HCC. Initial results were manually refined by prespecified criteria. Patients were included if they were diagnosed with HCC and received HCC treatment at the Memphis VAMC. Patients were excluded if HCC was not diagnosed histologically or clinically by imaging characteristics and AFP level, if the patient’s primary treatment was not provided at the Memphis VAMC, if they were lost to follow-up, or if race was not specified as either Black or White.

The following patient variables were examined: age, sex, comorbidities (alcohol or substance use disorder, cirrhosis, HIV), tumor stage, AFP, method of diagnosis, first-line treatments, systemic treatment, surgical options offered, and mortality. Staging was based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM staging for HCC.13 Surgical options were recorded as resection or transplant. Patients who were offered treatment but lost to follow-up were excluded from the analysis.

Data Analysis

Our primary endpoint was identifying differences in OS among Memphis VAMC patients with HCC related to race. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to investigate differences in OS and cumulative hazard ratio (HR) for death. Cox regression multivariate analysis further evaluated discrepancies among investigated patient variables, including age, race, alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drug use, HIV coinfection, and cirrhosis. Treatment factors were further defined by first-line treatment, systemic therapy, surgical resection, and transplant. χ2 analysis was used to investigate differences in treatment modalities.

Results

We identified 227 veterans, 95 Black and 132 White, between 2009 and 2021 meeting criteria for primary HCC treated at the Memphis VAMC. This study did not show a significant difference in OS between White and Black veterans (P = .24). Kaplan-Meier assessment showed OS was 1247 days (41 months) for Black veterans compared with 1032 days (34 months) for White veterans (Figure; Table 1).

Additionally, no significant difference was found between veterans for age or stage at diagnosis when stratified by race. The mean age of diagnosis for both groups was 65 years (P = .09). The mean TNM staging was 1.7 for White veterans vs 1.8 for Black veterans (P = .57). There was a significant increase in the AFP level at diagnosis for Black veterans (P = .001) (Table 2).

The most common initial treatment for both groups was transarterial chemoembolization and radiofrequency ablation with 68% of White and 64% of Black veterans receiving this therapy. There was no significant difference between who received systemic therapy.

However, we found significant differences by race for some forms of treatment. In our analysis, significant differences existed between those who did not receive any form of treatment as well as who received surgical resection and transplant. Among Black veterans, 11.6% received no treatment vs 6.1% for White veterans (P = .001). Only 2.1% of Black veterans underwent surgical resection vs 8.3% of White veterans (P = .046). Similarly, 13 (9.8%) White veterans vs 3 (3.2%) Black veterans received orthotopic liver transplantation (P = .052) in our cohort (eAppendix available at doi:10.12788/fp.0304). We found no differences in patient characteristics affecting OS, including alcohol use, tobacco use, illicit drug use, HIV coinfection, or liver cirrhosis (Table 3).

Discussion

In this retrospective analysis, Black veterans with HCC did not experience a statistically significant decrease in OS compared with that of White veterans despite some differences in therapy offered. Other studies have found that surgery was less frequently recommended to Black patients across multiple cancer types, and in most cases this carried a negative impact on OS.8,10,11,14,15 A number of other studies have demonstrated a greater percentage of Black patients receiving no treatment, although these studies are often based on SEER data, which captures only cancer-directed surgery and no other methods of treatment. Inequities in patient factors like insurance and socioeconomic status as well as willingness to receive certain treatments are often cited as major influences in health care disparities, but systemic and clinician factors like hospital volume, clinician expertise, specialist availability, and implicit racial bias all affect outcomes.16 One benefit of our study was that CPRS provided a centralized recording of all treatments received. Interestingly, the treatment discrepancy in our study was not attributable to a statistically significant difference in tumor stage at presentation. There should be no misconception that US Department of Veterans Affairs patients are less affected by socioeconomic inequities, though still this suggests clinician and systemic factors were significant drivers behind our findings.

This study did not intend to determine differences in incidence of HCC by race, although many studies have shown an age-adjusted incidence of HCC among Black and Hispanic patients up to twice that of White patients.1,8-10 Notably, the rate of orthotopic liver transplantation in this study was low regardless of race compared with that of other larger studies of patients with HCC.12,15 Discrepancies in HCC care among White and Black patients have been suggested to stem from a variety of influences, including access to early diagnosis and treatment of hepatitis C virus, comorbid conditions, as well as complex socioeconomic factors. It also has been shown that oncologists’ implicit racial bias has a negative impact on patients’ perceived quality of communication, their confidence in the recommended treatment, and the understood difficulty of the treatment by the patient and should be considered as a contributor to health disparities.17,18

Studies evaluating survival in HCC using SEER data generally stratify disease by localized, regional, or distant metastasis. For our study, TNM staging provided a more accurate assessment of the disease and reduced the chances that broader staging definitions could obscure differences in treatment choices. Future studies could be improved by stratifying patients by variables impacting treatment choice, such as Child-Pugh score or Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging. Our study demonstrated a statistically significant difference in AFP level between White and Black veterans. This has been observed in prior studies as well, and while no specific cause has been identified, it suggests differences in tumor biologic features across different races. In addition, we found that an elevated AFP level at the time of diagnosis (defined as > 400) correlates with a worsened OS (HR, 1.36; P = .01).

Limitations

This study has several limitations, notably the number of veterans eligible for analysis at a single institution. A larger cohort would be needed to evaluate for statistically significant differences in outcomes by race. Additionally, our study did not account for therapy that was offered to but not pursued by the patient, and this would be useful to determine whether patient or practitioner factors were the more significant influence on the type of therapy received.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated a statistically significant difference in the rate of resection and liver transplantation between White and Black veterans at a single institution, although no difference in OS was observed. This discrepancy was not explained by differences in tumor staging. Additional, larger studies will be useful in clarifying the biologic, cultural, and socioeconomic drivers in HCC treatment and mortality.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lorri Reaves, Memphis Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Department of Hepatology.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common and third most deadly malignancy worldwide, carrying a mean survival rate without treatment of 6 to 20 months depending on stage.1 Fifty-seven percent of patients with liver cancer are diagnosed with regional or distant metastatic disease that carries 5-year relative survival rates of 10.7% and 3.1%, respectively.2 HCC arises most commonly from liver cirrhosis due to chronic hepatocyte injury, which may be mediated by viral hepatitis, alcoholism, and metabolic disease. Other less common causes include autoimmune disease, exposure to environmental hazards, and certain genetic diseases, such as α-1 antitrypsin deficiency and Wilson disease.

Multiple staging systems for HCC exist that incorporate some variation of the following features: size and invasion of the tumor, distant metastases, and liver function. Stage-directed treatments for HCC include ablation, embolization, resection, transplant, and systemic therapy, such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors, immunotherapies, and monoclonal antibodies. In addition to tumor/node/metastasis (TNM) staging, α-fetoprotein (AFP) is a diagnostic marker with prognostic value in HCC with higher levels correlating to higher tumor burden and a worse prognosis. With treatment, the 5-year survival rate for early stage HCC ranges from 60% to 80% but decreases significantly with higher stages.1 HCC screening in at-risk populations has accounted for > 40% of diagnoses since the practice became widely adopted, and earlier recognition has led to an improvement in survival even when adjusting for lead time bias.3

Systemic therapy for advanced disease continues to improve. Sorafenib remained the standard first-line systemic therapy since it was introduced in 2008.4 First-line therapy improved with immunotherapies. The phase 3 IMBrave150 trial comparing atezolizumab plus bevacizumab to sorafenib showed a median overall survival (OS) > 19 months with 7.7% of patients achieving a complete response.5 HIMALAYA, another phase 3 trial set for publication later this year, also reported promising results when a priming dose of the CTLA-4 inhibitor tremelimumab followed by durvalumab was compared with sorafenib.6

There has been a rise in incidence of HCC in the United States across all races and ethnicities, though Black, Hispanic, and Asian patients remain disproportionately affected. Subsequently, identifying causative biologic, socioeconomic, and cultural factors, as well as implicit bias in health care continues to be a topic of great interest.7-9 Using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data, a number of large studies have found that Black patients with HCC were more likely to present with an advanced stage, less likely to receive curative intent treatment, and had significantly reduced survival compared with that of White patients.1,7-9 An analysis of 1117 patients by Rich and colleagues noted a 34% increased risk of death for Black patients with HCC compared with that of White patients, and other studies have shown about a 50% reduction in rate of liver transplantation for Black patients.10-12 Our study aimed to investigate potential disparities in incidence, etiology, AFP level at diagnosis, and outcomes of HCC in Black and White veterans managed at the Memphis Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Tennessee.

Methods

A single center retrospective chart review was conducted at the Memphis VAMC using the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code C22.0 for HCC. Initial results were manually refined by prespecified criteria. Patients were included if they were diagnosed with HCC and received HCC treatment at the Memphis VAMC. Patients were excluded if HCC was not diagnosed histologically or clinically by imaging characteristics and AFP level, if the patient’s primary treatment was not provided at the Memphis VAMC, if they were lost to follow-up, or if race was not specified as either Black or White.

The following patient variables were examined: age, sex, comorbidities (alcohol or substance use disorder, cirrhosis, HIV), tumor stage, AFP, method of diagnosis, first-line treatments, systemic treatment, surgical options offered, and mortality. Staging was based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM staging for HCC.13 Surgical options were recorded as resection or transplant. Patients who were offered treatment but lost to follow-up were excluded from the analysis.

Data Analysis

Our primary endpoint was identifying differences in OS among Memphis VAMC patients with HCC related to race. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to investigate differences in OS and cumulative hazard ratio (HR) for death. Cox regression multivariate analysis further evaluated discrepancies among investigated patient variables, including age, race, alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drug use, HIV coinfection, and cirrhosis. Treatment factors were further defined by first-line treatment, systemic therapy, surgical resection, and transplant. χ2 analysis was used to investigate differences in treatment modalities.

Results

We identified 227 veterans, 95 Black and 132 White, between 2009 and 2021 meeting criteria for primary HCC treated at the Memphis VAMC. This study did not show a significant difference in OS between White and Black veterans (P = .24). Kaplan-Meier assessment showed OS was 1247 days (41 months) for Black veterans compared with 1032 days (34 months) for White veterans (Figure; Table 1).

Additionally, no significant difference was found between veterans for age or stage at diagnosis when stratified by race. The mean age of diagnosis for both groups was 65 years (P = .09). The mean TNM staging was 1.7 for White veterans vs 1.8 for Black veterans (P = .57). There was a significant increase in the AFP level at diagnosis for Black veterans (P = .001) (Table 2).

The most common initial treatment for both groups was transarterial chemoembolization and radiofrequency ablation with 68% of White and 64% of Black veterans receiving this therapy. There was no significant difference between who received systemic therapy.

However, we found significant differences by race for some forms of treatment. In our analysis, significant differences existed between those who did not receive any form of treatment as well as who received surgical resection and transplant. Among Black veterans, 11.6% received no treatment vs 6.1% for White veterans (P = .001). Only 2.1% of Black veterans underwent surgical resection vs 8.3% of White veterans (P = .046). Similarly, 13 (9.8%) White veterans vs 3 (3.2%) Black veterans received orthotopic liver transplantation (P = .052) in our cohort (eAppendix available at doi:10.12788/fp.0304). We found no differences in patient characteristics affecting OS, including alcohol use, tobacco use, illicit drug use, HIV coinfection, or liver cirrhosis (Table 3).

Discussion

In this retrospective analysis, Black veterans with HCC did not experience a statistically significant decrease in OS compared with that of White veterans despite some differences in therapy offered. Other studies have found that surgery was less frequently recommended to Black patients across multiple cancer types, and in most cases this carried a negative impact on OS.8,10,11,14,15 A number of other studies have demonstrated a greater percentage of Black patients receiving no treatment, although these studies are often based on SEER data, which captures only cancer-directed surgery and no other methods of treatment. Inequities in patient factors like insurance and socioeconomic status as well as willingness to receive certain treatments are often cited as major influences in health care disparities, but systemic and clinician factors like hospital volume, clinician expertise, specialist availability, and implicit racial bias all affect outcomes.16 One benefit of our study was that CPRS provided a centralized recording of all treatments received. Interestingly, the treatment discrepancy in our study was not attributable to a statistically significant difference in tumor stage at presentation. There should be no misconception that US Department of Veterans Affairs patients are less affected by socioeconomic inequities, though still this suggests clinician and systemic factors were significant drivers behind our findings.

This study did not intend to determine differences in incidence of HCC by race, although many studies have shown an age-adjusted incidence of HCC among Black and Hispanic patients up to twice that of White patients.1,8-10 Notably, the rate of orthotopic liver transplantation in this study was low regardless of race compared with that of other larger studies of patients with HCC.12,15 Discrepancies in HCC care among White and Black patients have been suggested to stem from a variety of influences, including access to early diagnosis and treatment of hepatitis C virus, comorbid conditions, as well as complex socioeconomic factors. It also has been shown that oncologists’ implicit racial bias has a negative impact on patients’ perceived quality of communication, their confidence in the recommended treatment, and the understood difficulty of the treatment by the patient and should be considered as a contributor to health disparities.17,18

Studies evaluating survival in HCC using SEER data generally stratify disease by localized, regional, or distant metastasis. For our study, TNM staging provided a more accurate assessment of the disease and reduced the chances that broader staging definitions could obscure differences in treatment choices. Future studies could be improved by stratifying patients by variables impacting treatment choice, such as Child-Pugh score or Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging. Our study demonstrated a statistically significant difference in AFP level between White and Black veterans. This has been observed in prior studies as well, and while no specific cause has been identified, it suggests differences in tumor biologic features across different races. In addition, we found that an elevated AFP level at the time of diagnosis (defined as > 400) correlates with a worsened OS (HR, 1.36; P = .01).

Limitations

This study has several limitations, notably the number of veterans eligible for analysis at a single institution. A larger cohort would be needed to evaluate for statistically significant differences in outcomes by race. Additionally, our study did not account for therapy that was offered to but not pursued by the patient, and this would be useful to determine whether patient or practitioner factors were the more significant influence on the type of therapy received.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated a statistically significant difference in the rate of resection and liver transplantation between White and Black veterans at a single institution, although no difference in OS was observed. This discrepancy was not explained by differences in tumor staging. Additional, larger studies will be useful in clarifying the biologic, cultural, and socioeconomic drivers in HCC treatment and mortality.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lorri Reaves, Memphis Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Department of Hepatology.

1. Altekruse SF, McGlynn KA, Reichman ME. Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence, mortality, and survival trends in the United States from 1975 to 2005. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(9):1485-1491. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7753

2. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2012, National Cancer Institute. Accessed July 8, 2022. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2012/results_merged/sect_14_liver_bile.pdf#page=8

3. Singal AG, Mittal S, Yerokun OA, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma screening associated with early tumor detection and improved survival among patients with cirrhosis in the US. Am J Med. 2017;130(9):1099-1106.e1. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.01.021

4. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(4):378-390. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0708857

5. Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):1894-1905. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1915745

6. Abou-Alfa GK, Chan SL, Kudo M, et al. Phase 3 randomized, open-label, multicenter study of tremelimumab (T) and durvalumab (D) as first-line therapy in patients (pts) with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC): HIMALAYA. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(suppl 4):379. doi:10.1200/JCO.2022.40.4_suppl.379

7. Franco RA, Fan Y, Jarosek S, Bae S, Galbraith J. Racial and geographic disparities in hepatocellular carcinoma outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(5)(suppl 1):S40-S48. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.05.030

8. Ha J, Yan M, Aguilar M, et al. Race/ethnicity-specific disparities in hepatocellular carcinoma stage at diagnosis and its impact on receipt of curative therapies. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50(5):423-430. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000448

9. Wong R, Corley DA. Racial and ethnic variations in hepatocellular carcinoma incidence within the United States. Am J Med. 2008;121(6):525-531. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.03.005

10. Rich NE, Hester C, Odewole M, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in presentation and outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(3):551-559.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2018.05.039

11. Peters NA, Javed AA, He J, Wolfgang CL, Weiss MJ. Association of socioeconomics, surgical therapy, and survival of early stage hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Res. 2017;210:253-260. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2016.11.042

12. Wong RJ, Devaki P, Nguyen L, Cheung R, Nguyen MH. Ethnic disparities and liver transplantation rates in hepatocellular carcinoma patients in the recent era: results from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry. Liver Transpl. 2014;20(5):528-535. doi:10.1002/lt.23820

13. Minagawa M, Ikai I, Matsuyama Y, Yamaoka Y, Makuuchi M. Staging of hepatocellular carcinoma: assessment of the Japanese TNM and AJCC/UICC TNM systems in a cohort of 13,772 patients in Japan. Ann Surg. 2007;245(6):909-922. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000254368.65878.da.

14. Harrison LE, Reichman T, Koneru B, et al. Racial discrepancies in the outcome of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Arch Surg. 2004;139(9):992-996. doi:10.1001/archsurg.139.9.992

15. Sloane D, Chen H, Howell C. Racial disparity in primary hepatocellular carcinoma: tumor stage at presentation, surgical treatment and survival. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(12):1934-1939.

16. Haider AH, Scott VK, Rehman KA, et al. Racial disparities in surgical care and outcomes in the United States: a comprehensive review of patient, provider, and systemic factors. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216(3):482-92.e12. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.11.014

17. Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA, et al. The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):979-987. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300558

18. Penner LA, Dovidio JF, Gonzalez R, et al. The effects of oncologist implicit racial bias in racially discordant oncology interactions. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(24):2874-2880. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.66.3658

1. Altekruse SF, McGlynn KA, Reichman ME. Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence, mortality, and survival trends in the United States from 1975 to 2005. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(9):1485-1491. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7753

2. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2012, National Cancer Institute. Accessed July 8, 2022. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2012/results_merged/sect_14_liver_bile.pdf#page=8

3. Singal AG, Mittal S, Yerokun OA, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma screening associated with early tumor detection and improved survival among patients with cirrhosis in the US. Am J Med. 2017;130(9):1099-1106.e1. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.01.021

4. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(4):378-390. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0708857

5. Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):1894-1905. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1915745

6. Abou-Alfa GK, Chan SL, Kudo M, et al. Phase 3 randomized, open-label, multicenter study of tremelimumab (T) and durvalumab (D) as first-line therapy in patients (pts) with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC): HIMALAYA. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(suppl 4):379. doi:10.1200/JCO.2022.40.4_suppl.379

7. Franco RA, Fan Y, Jarosek S, Bae S, Galbraith J. Racial and geographic disparities in hepatocellular carcinoma outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(5)(suppl 1):S40-S48. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.05.030

8. Ha J, Yan M, Aguilar M, et al. Race/ethnicity-specific disparities in hepatocellular carcinoma stage at diagnosis and its impact on receipt of curative therapies. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50(5):423-430. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000448

9. Wong R, Corley DA. Racial and ethnic variations in hepatocellular carcinoma incidence within the United States. Am J Med. 2008;121(6):525-531. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.03.005

10. Rich NE, Hester C, Odewole M, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in presentation and outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(3):551-559.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2018.05.039

11. Peters NA, Javed AA, He J, Wolfgang CL, Weiss MJ. Association of socioeconomics, surgical therapy, and survival of early stage hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Res. 2017;210:253-260. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2016.11.042

12. Wong RJ, Devaki P, Nguyen L, Cheung R, Nguyen MH. Ethnic disparities and liver transplantation rates in hepatocellular carcinoma patients in the recent era: results from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry. Liver Transpl. 2014;20(5):528-535. doi:10.1002/lt.23820

13. Minagawa M, Ikai I, Matsuyama Y, Yamaoka Y, Makuuchi M. Staging of hepatocellular carcinoma: assessment of the Japanese TNM and AJCC/UICC TNM systems in a cohort of 13,772 patients in Japan. Ann Surg. 2007;245(6):909-922. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000254368.65878.da.

14. Harrison LE, Reichman T, Koneru B, et al. Racial discrepancies in the outcome of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Arch Surg. 2004;139(9):992-996. doi:10.1001/archsurg.139.9.992

15. Sloane D, Chen H, Howell C. Racial disparity in primary hepatocellular carcinoma: tumor stage at presentation, surgical treatment and survival. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(12):1934-1939.

16. Haider AH, Scott VK, Rehman KA, et al. Racial disparities in surgical care and outcomes in the United States: a comprehensive review of patient, provider, and systemic factors. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216(3):482-92.e12. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.11.014

17. Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA, et al. The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):979-987. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300558

18. Penner LA, Dovidio JF, Gonzalez R, et al. The effects of oncologist implicit racial bias in racially discordant oncology interactions. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(24):2874-2880. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.66.3658

Antiviral Therapy Improves Hepatocellular Cancer Survival

Hepatocellular cancer (HCC) is the most common type of hepatic cancers, accounting for 65% of all hepatic cancers.1 Among all cancers, HCC is one of the fastest growing causes of death in the United States, and the rate of new HCC cases are on the rise over several decades.2 There are many risk factors leading to HCC, including alcohol use, obesity, and smoking. Infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) poses a significant risk.1

The pathogenesis of HCV-induced carcinogenesis is mediated by a unique host-induced immunologic response. Viral replication induces production of inflammatory factors, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), interferon (IFN), and oxidative stress on hepatocytes, resulting in cell injury, death, and regeneration. Repetitive cycles of cellular death and regeneration induce fibrosis, which may lead to cirrhosis.3 Hence, early treatment of HCV infection and achieving sustained virologic response (SVR) may lead to decreased incidence and mortality associated with HCC.

Treatment of HCV infection has become more effective with the development of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) leading to SVR in > 90% of patients compared with 40 to 50% with IFN-based treatment.4,5 DAAs have been proved safe and highly effective in eradicating HCV infection even in patients with advanced liver disease with decompensated cirrhosis.6 Although achieving SVR indicates a complete cure from chronic HCV infection, several studies have shown subsequent risk of developing HCC persists even after successful HCV treatment.7-9 Some studies show that using DAAs to achieve SVR in patients with HCV infection leads to a decreased relative risk of HCC development compared with patients who do not receive treatment.10-12 But data on HCC risk following DAA-induced SVR vs IFN-induced SVR are somewhat conflicting.

Much of the information regarding the association between SVR and HCC has been gleaned from large data banks without accounting for individual patient characteristics that can be obtained through full chart review. Due to small sample sizes in many chart review studies, the impact that SVR from DAA therapy has on the progression and severity of HCC is not entirely clear. The aim of our study is to evaluate the effect of HCV treatment and SVR status on overall survival (OS) in patients with HCC. Second, we aim to compare survival benefits, if any exist, among the 2 major HCV treatment modalities (IFN vs DAA).

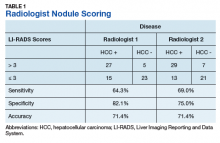

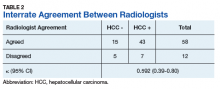

Methods

We performed a retrospective review of patients at Memphis Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Tennessee to determine whether treatment for HCV infection in general, and achieving SVR in particular, makes a difference in progression, recurrence, or OS among patients with HCV infection who develop HCC. We identified 111 patients with a diagnosis of both HCV and new or recurrent HCC lesions from November 2008 to March 2019 (Table 1). We divided these patients based on their HCV treatment status, SVR status, and treatment types (IFN vs DAA).

The inclusion criteria were patients aged > 18 years treated at the Memphis VAMC who have HCV infection and developed HCC. Exclusion criteria were patients who developed HCC from other causes such as alcoholic steatohepatitis, hepatitis B virus infection, hemochromatosis, patients without HCV infection, and patients who were not established at the Memphis VAMC. This protocol was approved by the Memphis VAMC Institutional Review Board.

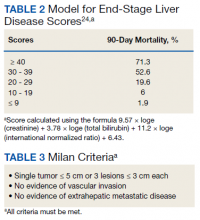

HCC diagnosis was determined using International Classification of Diseases codes (9th revision: 155 and 155.2; 10th revision: CD 22 and 22.9). We also used records of multidisciplinary gastrointestinal malignancy tumor conferences to identify patient who had been diagnosed and treated for HCV infection. We identified patients who were treated with DAA vs IFN as well as patients who had achieved SVR (classified as having negative HCV RNA tests at the end of DAA treatment). We were unable to evaluate Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging since this required documented performance status that was not available in many patient records. We selected cases consistent with both treatment for HCV infection and subsequent development of HCC. Patient data included age; OS time; HIV status HCV genotype; time and status of progression to HCC; type and duration of treatment; and alcohol, tobacco, and drug use. Disease status was measured using the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score (Table 2), Milan criteria (Table 3), and Child-Pugh score (Table 4).

Statistical Analysis

OS was measured from the date of HCC diagnosis to the date of death or last follow-up. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined from the date of HCC treatment initiation to the date of first HCC recurrence. We compared survival data for the SVR and non-SVR subgroups, the HCV treatment vs non-HCV treatment subgroups, and the IFN therapy vs DAA therapy subgroups, using the Kaplan-Meier method. The differences between subgroups were assessed using a log-rank test. Multivariate analysis using Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to identify factors that had significant impact on OS. Those factors included age; race; alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use; SVR status; HCV treatment status; IFN-based regimen vs DAA; MELD, and Child-Pugh scores. The results were expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CI. Calculations were made using Statistical Analysis SAS and IBM SPSS software.

Results

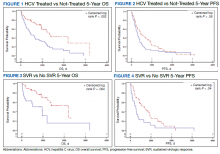

The study included 111 patients. The mean age was 65.7 years; all were male and half of were Black patients. The gender imbalance was due to the predominantly male patient population at Memphis VAMC. Among 111 patients with HCV infection and HCC, 68 patients were treated for HCV infection and had significantly improved OS and PFS compared with the nontreatment group. The median 5-year OS was 44.6 months (95% CI, 966-3202) in the treated HCV infection group compared with 15.1 months in the untreated HCV infection group with a Wilcoxon P = .0005 (Figure 1). Similarly, patients treated for HCV infection had a significantly better 5-year PFS of 15.3 months (95% CI, 294-726) compared with the nontreatment group 9.5 months (95% CI, 205-405) with a Wilcoxon P = .04 (Figure 2).

Among 68 patients treated for HCV infection, 51 achieved SVR, and 34 achieved SVR after the diagnosis of HCC. Patients who achieved SVR had an improved 5-year OS when compared with patients who did not achieve SVR (median 65.8 months [95% CI, 1222-NA] vs 15.7 months [95% CI, 242-853], Wilcoxon P < .001) (Figure 3). Similarly, patients with SVR had improved 5-year PFS when compared with the non-SVR group (median 20.5 months [95% CI, 431-914] vs 8.9 months [95% CI, 191-340], Wilcoxon P = .007 (Figure 4). Achievement of SVR after HCC diagnosis suggests a significantly improved OS (HR 0.37) compared with achievement prior to HCC diagnosis (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.23-1.82, P = .41)

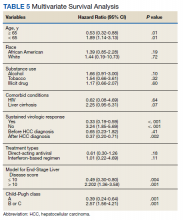

Multivariate Cox regression was used to determine factors with significant survival impact. Advanced age at diagnosis (aged ≥ 65 years) (HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.320-0.880; P = .01), SVR status (HR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.190-0.587; P < .001), achieving SVR after HCC diagnosis (HR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.20-0.71; P = .002), low MELD score (< 10) (HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.30-0.80; P = .004) and low Child-Pugh score (class A) (HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.24-0.64; P = .001) have a significant positive impact on OS. Survival was not significantly influenced by race, tobacco, drug use, HIV or cirrhosis status, or HCV treatment type. In addition, higher Child-Pugh class (B or C), higher MELD score (> 10), and younger age at diagnosis (< 65 years) have a negative impact on survival outcome (Table 5).

Discussion

The survival benefit of HCV eradication and achieving SVR status has been well established in patients with HCC.13 In a retrospective cohort study of 250 patients with HCV infection who had received curative treatment for HCC, multivariate analysis demonstrated that achieving SVR is an independent predictor of OS.14 The 3-year and 5-year OS rates were 97% and 94% for the SVR group, and 91% and 60% for the non‐SVR group, respectively (P < .001). Similarly, according to Sou and colleagues, of 122 patients with HCV-related HCC, patients with SVR had longer OS than patients with no SVR (P = .04).15 One of the hypotheses that could explain the survival benefit in patients who achieved SVR is the effect of achieving SVR in reducing persistent liver inflammation and associated liver mortality, and therefore lowering risks of complication in patients with HCC.16 In our study, multivariate analysis shows that achieving SVR is associated with significant improved OS (HR, 0.33). In contrast, patients with HCC who have not achieved SVR are associated with worse survival (HR, 3.24). This finding supports early treatment of HCV to obtain SVR in HCV-related patients with HCC, even after development of HCC.

Among 68 patients treated for HCV infection, 45 patients were treated after HCC diagnosis, and 34 patients achieved SVR after HCC diagnosis. The average time between HCV infection treatment after HCC diagnosis was 6 months. Our data suggested that achievement of SVR after HCC diagnosis suggests an improved OS (HR, 0.37) compared with achievement prior to HCC diagnosis (HR, 0.65; 95% CI,0.23-1.82; P = .41). This lack of statistical significance is likely due to small sample size of patients achieving SVR prior to HCC diagnosis. Our results are consistent with the findings regarding the efficacy and timing of DAA treatment in patients with active HCC. According to Singal and colleagues, achieving SVR after DAA therapy may result in improved liver function and facilitate additional HCC-directed therapy, which potentially improves survival.17-19

Nagaoki and colleagues found that there was no significant difference in OS in patients with HCC between the DAA and IFN groups. According to the study, the 3-year and 5-year OS rates were 96% and 96% for DAA patients and 93% and 73% for IFN patients, respectively (P = .16).14 This finding is consistent with the results of our study. HCV treatment type (IFN vs DAA) was not found to be associated with either OS or PFS time, regardless of time period.

A higher MELD score (> 10) and a higher Child-Pugh class (B or C) score are associated with worse survival outcome regardless of SVR status. While patients with a low MELD score (≤ 10) have a better survival rate (HR 0.49), a higher MELD score has a significantly higher HR and therefore worse survival outcomes (HR, 2.20). Similarly, patients with Child-Pugh A (HR, 0.39) have a better survival outcome compared with those patients with Child-Pugh class B or C (HR, 2.57). This finding is consistent with results of multiple studies indicating that advanced liver disease, as measured by a high MELD score and Child-Pugh class score, can be used to predict the survival outcome in patients with HCV-related HCC.20-22

Unlike other studies that look at a single prognostic variable, our study evaluated prognostic impacts of multiple variables (age, SVR status, the order of SVR in relation to HCC development, HCV treatment type, MELD score and Child-Pugh class) in patients with HCC. The study included patients treated for HCV after development of HCC along with other multiple variables leading to OS benefit. It is one of the only studies in the United States that compared 5-year OS and PFS among patients with HCC treated for HCV and achieved SVR. The studies by Nagaoki and colleagues and Sou and colleagues were conducted in Japan, and some of their subset analyses were univariate. Among our study population of veterans, 50% were African American patients, suggesting that they may have similar OS benefit when compared to White patients with HCC and HCV treatment.

Limitations

Our findings were limited in that our study population is too small to conduct further subset analysis that would allow statistical significance of those subsets, such as the suggested benefit of SVR in patients who presented with HCC after antiviral therapy. Another limitation is the all-male population, likely a result of the older veteran population at the Memphis VAMC. The mean age at diagnosis was 65 years, which is slightly higher than the general population. Compared to the SEER database, HCC is most frequently diagnosed among people aged 55 to 64 years.23 The age difference was likely due to our aging veteran population.

Further studies are needed to determine the significance of SVR on HCC recurrence and treatment. Immunotherapy is now first-line treatment for patients with local advanced HCC. All the immunotherapy studies excluded patients with active HCV infection. Hence, we need more data on HCV treatment timing among patients scheduled to start treatment with immunotherapy.

Conclusions

In a population of older veterans, treatment of HCV infection leads to OS benefit among patients with HCC. In addition, patients with HCV infection who achieve SVR have an OS benefit over patients unable to achieve SVR. The type of treatment, DAA vs IFN-based regimen, did not show significant survival benefit.

1. Ghouri YA, Mian I, Rowe JH. Review of hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology, etiology, and carcinogenesis. J Carcinog. 2017;16:1. Published 2017 May 29. doi:10.4103/jcar.JCar_9_16

2. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394-424. doi:10.3322/caac.21492

3. Farazi PA, DePinho RA. Hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis: from genes to environment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(9):674-687. doi:10.1038/nrc1934

4. Falade-Nwulia O, Suarez-Cuervo C, Nelson DR, Fried MW, Segal JB, Sulkowski MS. Oral direct-acting agent therapy for hepatitis c virus infection: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(9):637-648. doi:10.7326/M16-2575

5. Kouris G, Hydery T, Greenwood BC, et al. Effectiveness of Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir and predictors of treatment failure in members with hepatitis C genotype 1 infection: a retrospective cohort study in a medicaid population. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24(7):591-597. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2018.24.7.591

6. Jacobson IM, Lawitz E, Kwo PY, et al. Safety and efficacy of elbasvir/grazoprevir in patients with hepatitis c virus infection and compensated cirrhosis: an integrated analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(6):1372-1382.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.050

7. Nahon P, Layese R, Bourcier V, et al. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma after direct antiviral therapy for HCV in patients with cirrhosis included in surveillance programs. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(5):1436-1450.e6. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.01510.

8. Innes H, Barclay ST, Hayes PC, et al. The risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients with hepatitis C and sustained viral response: role of the treatment regimen. J Hepatol. 2018;68(4):646-654. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.10.033

9. Romano A, Angeli P, Piovesan S, et al. Newly diagnosed hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with advanced hepatitis C treated with DAAs: a prospective population study. J Hepatol. 2018;69(2):345-352. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.009

10. Kanwal F, Kramer J, Asch SM, Chayanupatkul M, Cao Y, El-Serag HB. Risk of hepatocellular cancer in HCV patients treated with direct-acting antiviral agents. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(4):996-1005.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.0122

11. Singh S, Nautiyal A, Loke YK. Oral direct-acting antivirals and the incidence or recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2018;9(4):262-270. doi:10.1136/flgastro-2018-101017

12. Kuftinec G, Loehfelm T, Corwin M, et al. De novo hepatocellular carcinoma occurrence in hepatitis C cirrhotics treated with direct-acting antiviral agents. Hepat Oncol. 2018;5(1):HEP06. Published 2018 Jul 25. doi:10.2217/hep-2018-00033

13. Morgan RL, Baack B, Smith BD, Yartel A, Pitasi M, Falck-Ytter Y. Eradication of hepatitis C virus infection and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5 Pt 1):329-337. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303050-00005

14. Nagaoki Y, Imamura M, Nishida Y, et al. The impact of interferon-free direct-acting antivirals on clinical outcome after curative treatment for hepatitis C virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison with interferon-based therapy. J Med Virol. 2019;91(4):650-658. doi:10.1002/jmv.25352

15. Sou FM, Wu CK, Chang KC, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of HCC occurrence after antiviral therapy for HCV patients between sustained and non-sustained responders. J Formos Med Assoc. 2019;118(1 Pt 3):504-513. doi:10.1016/j.jfma.2018.10.017

16. Roche B, Coilly A, Duclos-Vallee JC, Samuel D. The impact of treatment of hepatitis C with DAAs on the occurrence of HCC. Liver Int. 2018;38(suppl 1):139-145. doi:10.1111/liv.13659

17. Singal AG, Lim JK, Kanwal F. AGA clinical practice update on interaction between oral direct-acting antivirals for chronic hepatitis C infection and hepatocellular carcinoma: expert review. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(8):2149-2157. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.02.046

18. Toyoda H, Kumada T, Hayashi K, et al. Characteristics and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma detected in sustained responders to interferon therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Cancer Detect Prev. 2003;27(6):498-502. doi:10.1016/j.cdp.2003.09.00719. Okamura Y, Sugiura T, Ito T, et al. The achievement of a sustained virological response either before or after hepatectomy improves the prognosis of patients with primary hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019; 26(13):4566-4575. doi:10.1245/s10434-019-07911-w

20. Wray CJ, Harvin JA, Silberfein EJ, Ko TC, Kao LS. Pilot prognostic model of extremely poor survival among high-risk hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Cancer. 2012;118(24):6118-6125. doi:10.1002/cncr.27649

21. Kim JH, Kim JH, Choi JH, et al. Value of the model for end-stage liver disease for predicting survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with transarterial chemoembolization. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44(3):346-357. doi:10.1080/00365520802530838

22. Vogeler M, Mohr I, Pfeiffenberger J, et al. Applicability of scoring systems predicting outcome of transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2020;146(4):1033-1050. doi:10.1007/s00432-020-03135-8

23. National Institutes of Health, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results. Cancer stat facts: cancer of the liver and intrahepatic bile duct. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/livibd.html

24. Singal AK, Kamath PS. Model for End-stage Liver Disease. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2013;3(1):50-60. doi:10.1016/j.jceh.2012.11.002

Hepatocellular cancer (HCC) is the most common type of hepatic cancers, accounting for 65% of all hepatic cancers.1 Among all cancers, HCC is one of the fastest growing causes of death in the United States, and the rate of new HCC cases are on the rise over several decades.2 There are many risk factors leading to HCC, including alcohol use, obesity, and smoking. Infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) poses a significant risk.1

The pathogenesis of HCV-induced carcinogenesis is mediated by a unique host-induced immunologic response. Viral replication induces production of inflammatory factors, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), interferon (IFN), and oxidative stress on hepatocytes, resulting in cell injury, death, and regeneration. Repetitive cycles of cellular death and regeneration induce fibrosis, which may lead to cirrhosis.3 Hence, early treatment of HCV infection and achieving sustained virologic response (SVR) may lead to decreased incidence and mortality associated with HCC.

Treatment of HCV infection has become more effective with the development of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) leading to SVR in > 90% of patients compared with 40 to 50% with IFN-based treatment.4,5 DAAs have been proved safe and highly effective in eradicating HCV infection even in patients with advanced liver disease with decompensated cirrhosis.6 Although achieving SVR indicates a complete cure from chronic HCV infection, several studies have shown subsequent risk of developing HCC persists even after successful HCV treatment.7-9 Some studies show that using DAAs to achieve SVR in patients with HCV infection leads to a decreased relative risk of HCC development compared with patients who do not receive treatment.10-12 But data on HCC risk following DAA-induced SVR vs IFN-induced SVR are somewhat conflicting.

Much of the information regarding the association between SVR and HCC has been gleaned from large data banks without accounting for individual patient characteristics that can be obtained through full chart review. Due to small sample sizes in many chart review studies, the impact that SVR from DAA therapy has on the progression and severity of HCC is not entirely clear. The aim of our study is to evaluate the effect of HCV treatment and SVR status on overall survival (OS) in patients with HCC. Second, we aim to compare survival benefits, if any exist, among the 2 major HCV treatment modalities (IFN vs DAA).

Methods

We performed a retrospective review of patients at Memphis Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Tennessee to determine whether treatment for HCV infection in general, and achieving SVR in particular, makes a difference in progression, recurrence, or OS among patients with HCV infection who develop HCC. We identified 111 patients with a diagnosis of both HCV and new or recurrent HCC lesions from November 2008 to March 2019 (Table 1). We divided these patients based on their HCV treatment status, SVR status, and treatment types (IFN vs DAA).

The inclusion criteria were patients aged > 18 years treated at the Memphis VAMC who have HCV infection and developed HCC. Exclusion criteria were patients who developed HCC from other causes such as alcoholic steatohepatitis, hepatitis B virus infection, hemochromatosis, patients without HCV infection, and patients who were not established at the Memphis VAMC. This protocol was approved by the Memphis VAMC Institutional Review Board.

HCC diagnosis was determined using International Classification of Diseases codes (9th revision: 155 and 155.2; 10th revision: CD 22 and 22.9). We also used records of multidisciplinary gastrointestinal malignancy tumor conferences to identify patient who had been diagnosed and treated for HCV infection. We identified patients who were treated with DAA vs IFN as well as patients who had achieved SVR (classified as having negative HCV RNA tests at the end of DAA treatment). We were unable to evaluate Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging since this required documented performance status that was not available in many patient records. We selected cases consistent with both treatment for HCV infection and subsequent development of HCC. Patient data included age; OS time; HIV status HCV genotype; time and status of progression to HCC; type and duration of treatment; and alcohol, tobacco, and drug use. Disease status was measured using the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score (Table 2), Milan criteria (Table 3), and Child-Pugh score (Table 4).

Statistical Analysis

OS was measured from the date of HCC diagnosis to the date of death or last follow-up. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined from the date of HCC treatment initiation to the date of first HCC recurrence. We compared survival data for the SVR and non-SVR subgroups, the HCV treatment vs non-HCV treatment subgroups, and the IFN therapy vs DAA therapy subgroups, using the Kaplan-Meier method. The differences between subgroups were assessed using a log-rank test. Multivariate analysis using Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to identify factors that had significant impact on OS. Those factors included age; race; alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use; SVR status; HCV treatment status; IFN-based regimen vs DAA; MELD, and Child-Pugh scores. The results were expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CI. Calculations were made using Statistical Analysis SAS and IBM SPSS software.

Results

The study included 111 patients. The mean age was 65.7 years; all were male and half of were Black patients. The gender imbalance was due to the predominantly male patient population at Memphis VAMC. Among 111 patients with HCV infection and HCC, 68 patients were treated for HCV infection and had significantly improved OS and PFS compared with the nontreatment group. The median 5-year OS was 44.6 months (95% CI, 966-3202) in the treated HCV infection group compared with 15.1 months in the untreated HCV infection group with a Wilcoxon P = .0005 (Figure 1). Similarly, patients treated for HCV infection had a significantly better 5-year PFS of 15.3 months (95% CI, 294-726) compared with the nontreatment group 9.5 months (95% CI, 205-405) with a Wilcoxon P = .04 (Figure 2).

Among 68 patients treated for HCV infection, 51 achieved SVR, and 34 achieved SVR after the diagnosis of HCC. Patients who achieved SVR had an improved 5-year OS when compared with patients who did not achieve SVR (median 65.8 months [95% CI, 1222-NA] vs 15.7 months [95% CI, 242-853], Wilcoxon P < .001) (Figure 3). Similarly, patients with SVR had improved 5-year PFS when compared with the non-SVR group (median 20.5 months [95% CI, 431-914] vs 8.9 months [95% CI, 191-340], Wilcoxon P = .007 (Figure 4). Achievement of SVR after HCC diagnosis suggests a significantly improved OS (HR 0.37) compared with achievement prior to HCC diagnosis (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.23-1.82, P = .41)

Multivariate Cox regression was used to determine factors with significant survival impact. Advanced age at diagnosis (aged ≥ 65 years) (HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.320-0.880; P = .01), SVR status (HR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.190-0.587; P < .001), achieving SVR after HCC diagnosis (HR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.20-0.71; P = .002), low MELD score (< 10) (HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.30-0.80; P = .004) and low Child-Pugh score (class A) (HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.24-0.64; P = .001) have a significant positive impact on OS. Survival was not significantly influenced by race, tobacco, drug use, HIV or cirrhosis status, or HCV treatment type. In addition, higher Child-Pugh class (B or C), higher MELD score (> 10), and younger age at diagnosis (< 65 years) have a negative impact on survival outcome (Table 5).

Discussion

The survival benefit of HCV eradication and achieving SVR status has been well established in patients with HCC.13 In a retrospective cohort study of 250 patients with HCV infection who had received curative treatment for HCC, multivariate analysis demonstrated that achieving SVR is an independent predictor of OS.14 The 3-year and 5-year OS rates were 97% and 94% for the SVR group, and 91% and 60% for the non‐SVR group, respectively (P < .001). Similarly, according to Sou and colleagues, of 122 patients with HCV-related HCC, patients with SVR had longer OS than patients with no SVR (P = .04).15 One of the hypotheses that could explain the survival benefit in patients who achieved SVR is the effect of achieving SVR in reducing persistent liver inflammation and associated liver mortality, and therefore lowering risks of complication in patients with HCC.16 In our study, multivariate analysis shows that achieving SVR is associated with significant improved OS (HR, 0.33). In contrast, patients with HCC who have not achieved SVR are associated with worse survival (HR, 3.24). This finding supports early treatment of HCV to obtain SVR in HCV-related patients with HCC, even after development of HCC.

Among 68 patients treated for HCV infection, 45 patients were treated after HCC diagnosis, and 34 patients achieved SVR after HCC diagnosis. The average time between HCV infection treatment after HCC diagnosis was 6 months. Our data suggested that achievement of SVR after HCC diagnosis suggests an improved OS (HR, 0.37) compared with achievement prior to HCC diagnosis (HR, 0.65; 95% CI,0.23-1.82; P = .41). This lack of statistical significance is likely due to small sample size of patients achieving SVR prior to HCC diagnosis. Our results are consistent with the findings regarding the efficacy and timing of DAA treatment in patients with active HCC. According to Singal and colleagues, achieving SVR after DAA therapy may result in improved liver function and facilitate additional HCC-directed therapy, which potentially improves survival.17-19

Nagaoki and colleagues found that there was no significant difference in OS in patients with HCC between the DAA and IFN groups. According to the study, the 3-year and 5-year OS rates were 96% and 96% for DAA patients and 93% and 73% for IFN patients, respectively (P = .16).14 This finding is consistent with the results of our study. HCV treatment type (IFN vs DAA) was not found to be associated with either OS or PFS time, regardless of time period.

A higher MELD score (> 10) and a higher Child-Pugh class (B or C) score are associated with worse survival outcome regardless of SVR status. While patients with a low MELD score (≤ 10) have a better survival rate (HR 0.49), a higher MELD score has a significantly higher HR and therefore worse survival outcomes (HR, 2.20). Similarly, patients with Child-Pugh A (HR, 0.39) have a better survival outcome compared with those patients with Child-Pugh class B or C (HR, 2.57). This finding is consistent with results of multiple studies indicating that advanced liver disease, as measured by a high MELD score and Child-Pugh class score, can be used to predict the survival outcome in patients with HCV-related HCC.20-22

Unlike other studies that look at a single prognostic variable, our study evaluated prognostic impacts of multiple variables (age, SVR status, the order of SVR in relation to HCC development, HCV treatment type, MELD score and Child-Pugh class) in patients with HCC. The study included patients treated for HCV after development of HCC along with other multiple variables leading to OS benefit. It is one of the only studies in the United States that compared 5-year OS and PFS among patients with HCC treated for HCV and achieved SVR. The studies by Nagaoki and colleagues and Sou and colleagues were conducted in Japan, and some of their subset analyses were univariate. Among our study population of veterans, 50% were African American patients, suggesting that they may have similar OS benefit when compared to White patients with HCC and HCV treatment.

Limitations

Our findings were limited in that our study population is too small to conduct further subset analysis that would allow statistical significance of those subsets, such as the suggested benefit of SVR in patients who presented with HCC after antiviral therapy. Another limitation is the all-male population, likely a result of the older veteran population at the Memphis VAMC. The mean age at diagnosis was 65 years, which is slightly higher than the general population. Compared to the SEER database, HCC is most frequently diagnosed among people aged 55 to 64 years.23 The age difference was likely due to our aging veteran population.

Further studies are needed to determine the significance of SVR on HCC recurrence and treatment. Immunotherapy is now first-line treatment for patients with local advanced HCC. All the immunotherapy studies excluded patients with active HCV infection. Hence, we need more data on HCV treatment timing among patients scheduled to start treatment with immunotherapy.

Conclusions

In a population of older veterans, treatment of HCV infection leads to OS benefit among patients with HCC. In addition, patients with HCV infection who achieve SVR have an OS benefit over patients unable to achieve SVR. The type of treatment, DAA vs IFN-based regimen, did not show significant survival benefit.

Hepatocellular cancer (HCC) is the most common type of hepatic cancers, accounting for 65% of all hepatic cancers.1 Among all cancers, HCC is one of the fastest growing causes of death in the United States, and the rate of new HCC cases are on the rise over several decades.2 There are many risk factors leading to HCC, including alcohol use, obesity, and smoking. Infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) poses a significant risk.1