User login

The Diagnosis: Paraneoplastic Acanthosis Nigricans

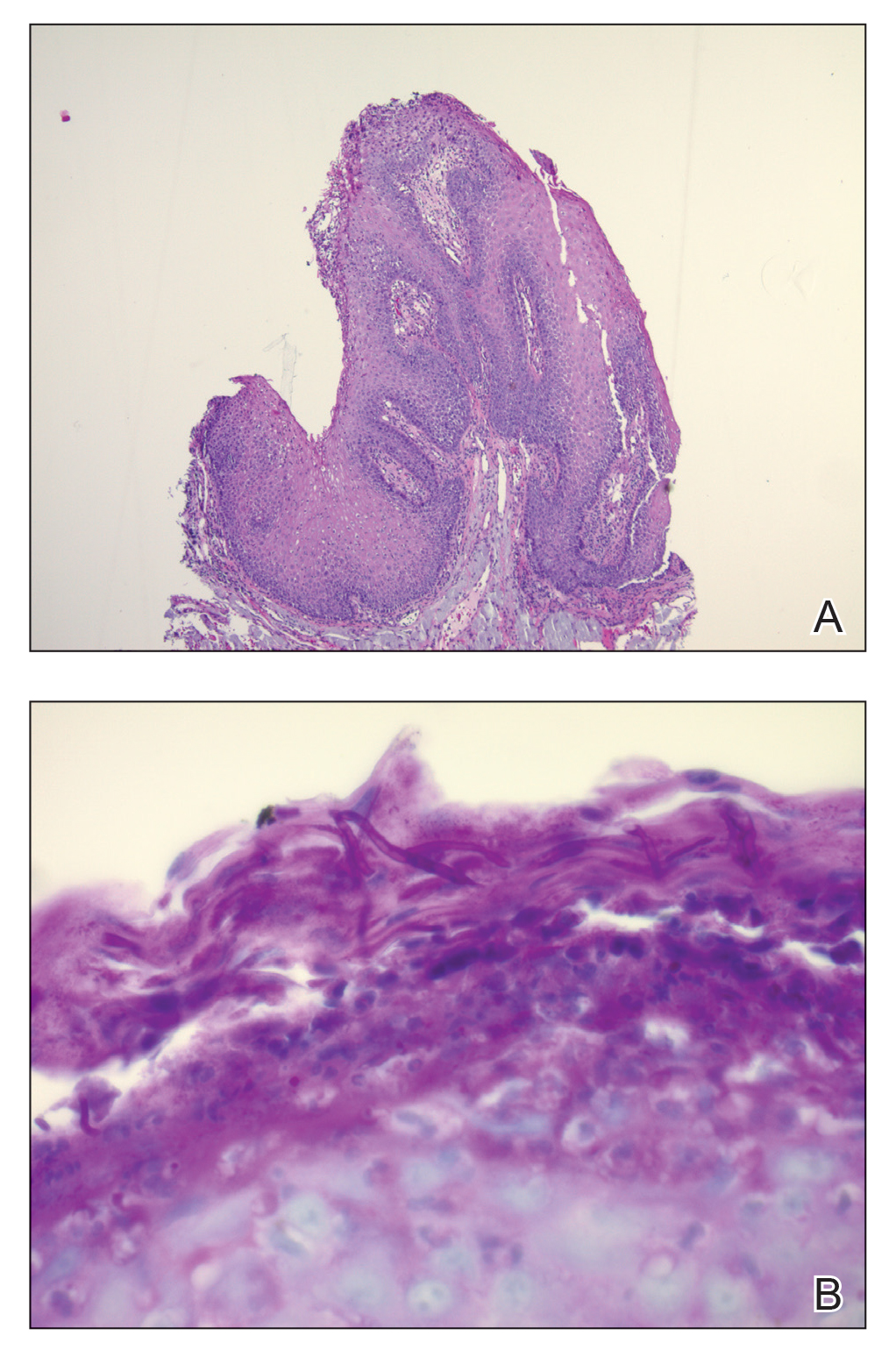

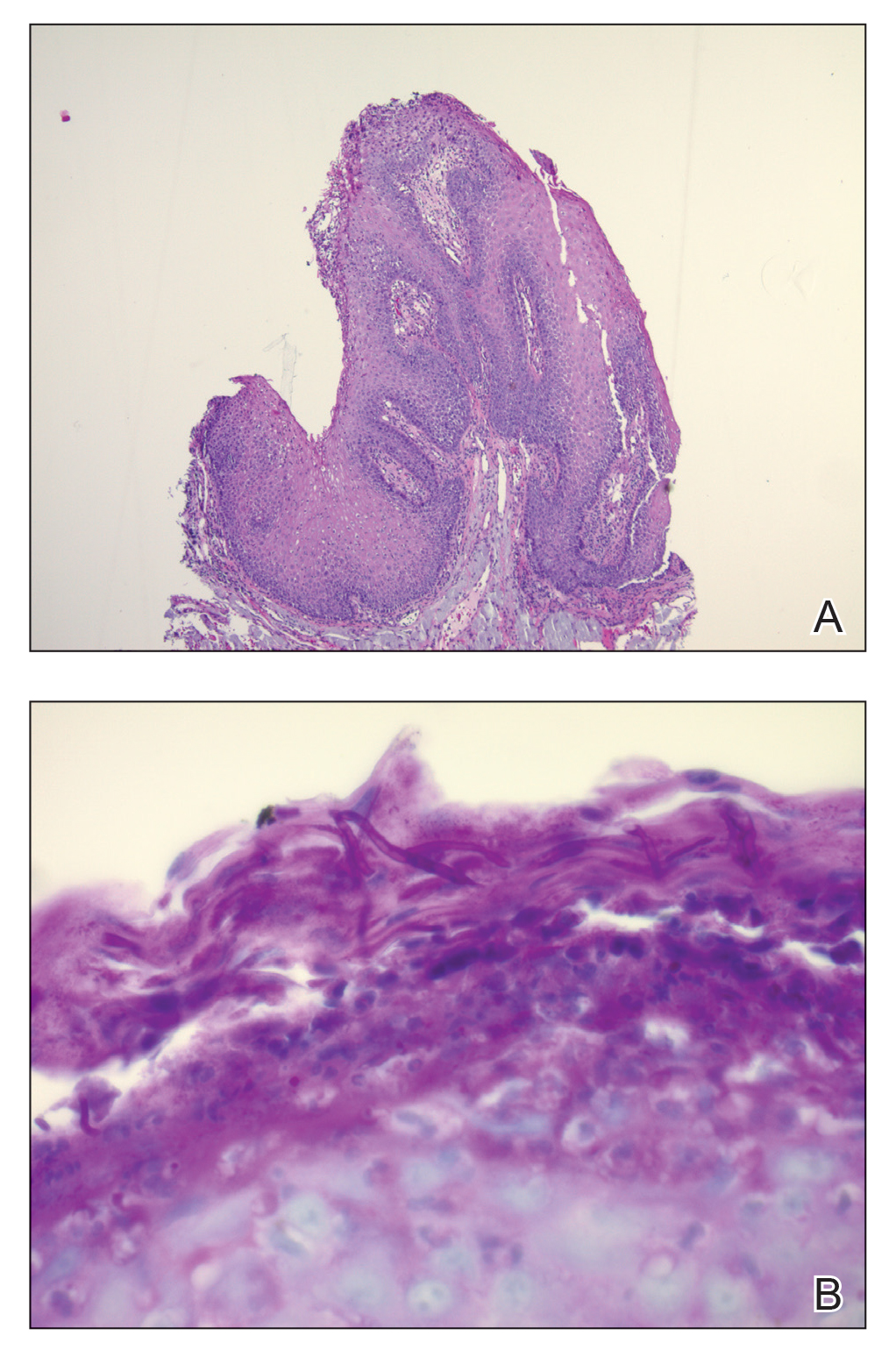

Histopathologic examination demonstrated verrucous epidermal hyperplasia (Figure, A). Fungal organisms were identified with an Alcian blue and periodic acid-Schiff stain (Figure, B). The organisms demonstrated a vertical orientation in relation to the mucosal surface, which was consistent with candidal organisms.

Given the rapid eruption of these plaques, the distribution on the oral and palmar surfaces (tripe palms), and the minimal improvement with both systemic steroids and antifungal treatment, a diagnosis of paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans with secondary candidal infection was made. Drug-induced cheilitis was considered; however, improvement with discontinuation of the suspected offending drug would have been expected. Although chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis was possible, more prompt improvement upon initiation of systemic antifungal therapy would have been observed. Oral Crohn disease should be included in the differential, but it was unlikely given the lack of granulomas on pathology and absence of history of gastrointestinal tract symptoms. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome also was unlikely given the lack of facial nerve palsy as well as the lack of granulomas on pathology. Furthermore, none of these options would be associated with tripe palms, as seen in our patient.

Acanthosis nigricans is a localized skin disorder characterized by hyperpigmented velvety plaques arising in flexural and intertriginous regions. Although most cases (80%) are associated with idiopathic or benign conditions, the link between acanthosis nigricans and an underlying malignancy has been well documented.1-3 Most commonly associated with an underlying intra-abdominal malignancy (often gastric carcinoma), the lesions of paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans are indistinguishable from their benign counterparts.1,4 When the condition presents abruptly and extensively in a nonobese patient, prompt workup for malignancy should be initiated. Rapid onset and atypical distribution (ie, palmar, perioral, or mucosal) more commonly is associated with a paraneoplastic etiology.5,6

Histopathology for acanthosis nigricans shows hyperkeratosis and epidermal papillomatosis. Horn pseudocyst formation is possible, but usually no hyperpigmentation is observed. The findings typically are indistinguishable from seborrheic keratoses, epidermal nevi, or lesions of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud.2

The underlying pathogenesis of acanthosis nigricans is poorly understood. In the benign subtype, insulin resistance commonly has been described. In the paraneoplastic subtype, it is proposed that the tumor produces a transforming growth factor that mimics epidermal growth factor and leads to keratinocyte proliferation.7,8 Paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans has the potential to arise at any point of tumor development, further contributing to the diagnostic challenge. Treatment of the skin lesions involves management of the underlying malignancy. Unfortunately, many such malignancies often are at an advanced stage, and subsequent prognosis is poor.2

- Shah A, Jack A, Liu H, et al. Neoplastic/paraneoplastic dermatitis, fasciitis, and panniculitis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2011;37:573-592.

- Chairatchaneeboon M, Kim EJ. Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes. In: Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019:2441-2464.

- Lee HC, Ker KJ, Chong WS. Oral malignant acanthosis nigricans and tripe palms associated with renal urothelial carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1381-1383.

- Yu Q, Li XL, Ji G, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: an early diagnostic clue for gastric adenocarcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2017;15:208.

- Mohrenschlager M, Vocks E, Wessner DB, et al. Tripe palms and malignant acanthosis nigricans: cutaneous signs of imminent metastasis in bladder cancer? J Urol. 2001;165:1629-1630.

- Cohen PR, Grossman ME, Almeida L, et al. Tripe palms and malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:669-678.

- Higgins SP, Freemark M, Prose NS. Acanthosis nigricans: a practical approach to evaluation and management. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:2.

- Torley D, Bellus GA, Munro CS. Genes, growth factors and acanthosis nigricans. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1096-1101.

The Diagnosis: Paraneoplastic Acanthosis Nigricans

Histopathologic examination demonstrated verrucous epidermal hyperplasia (Figure, A). Fungal organisms were identified with an Alcian blue and periodic acid-Schiff stain (Figure, B). The organisms demonstrated a vertical orientation in relation to the mucosal surface, which was consistent with candidal organisms.

Given the rapid eruption of these plaques, the distribution on the oral and palmar surfaces (tripe palms), and the minimal improvement with both systemic steroids and antifungal treatment, a diagnosis of paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans with secondary candidal infection was made. Drug-induced cheilitis was considered; however, improvement with discontinuation of the suspected offending drug would have been expected. Although chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis was possible, more prompt improvement upon initiation of systemic antifungal therapy would have been observed. Oral Crohn disease should be included in the differential, but it was unlikely given the lack of granulomas on pathology and absence of history of gastrointestinal tract symptoms. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome also was unlikely given the lack of facial nerve palsy as well as the lack of granulomas on pathology. Furthermore, none of these options would be associated with tripe palms, as seen in our patient.

Acanthosis nigricans is a localized skin disorder characterized by hyperpigmented velvety plaques arising in flexural and intertriginous regions. Although most cases (80%) are associated with idiopathic or benign conditions, the link between acanthosis nigricans and an underlying malignancy has been well documented.1-3 Most commonly associated with an underlying intra-abdominal malignancy (often gastric carcinoma), the lesions of paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans are indistinguishable from their benign counterparts.1,4 When the condition presents abruptly and extensively in a nonobese patient, prompt workup for malignancy should be initiated. Rapid onset and atypical distribution (ie, palmar, perioral, or mucosal) more commonly is associated with a paraneoplastic etiology.5,6

Histopathology for acanthosis nigricans shows hyperkeratosis and epidermal papillomatosis. Horn pseudocyst formation is possible, but usually no hyperpigmentation is observed. The findings typically are indistinguishable from seborrheic keratoses, epidermal nevi, or lesions of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud.2

The underlying pathogenesis of acanthosis nigricans is poorly understood. In the benign subtype, insulin resistance commonly has been described. In the paraneoplastic subtype, it is proposed that the tumor produces a transforming growth factor that mimics epidermal growth factor and leads to keratinocyte proliferation.7,8 Paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans has the potential to arise at any point of tumor development, further contributing to the diagnostic challenge. Treatment of the skin lesions involves management of the underlying malignancy. Unfortunately, many such malignancies often are at an advanced stage, and subsequent prognosis is poor.2

The Diagnosis: Paraneoplastic Acanthosis Nigricans

Histopathologic examination demonstrated verrucous epidermal hyperplasia (Figure, A). Fungal organisms were identified with an Alcian blue and periodic acid-Schiff stain (Figure, B). The organisms demonstrated a vertical orientation in relation to the mucosal surface, which was consistent with candidal organisms.

Given the rapid eruption of these plaques, the distribution on the oral and palmar surfaces (tripe palms), and the minimal improvement with both systemic steroids and antifungal treatment, a diagnosis of paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans with secondary candidal infection was made. Drug-induced cheilitis was considered; however, improvement with discontinuation of the suspected offending drug would have been expected. Although chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis was possible, more prompt improvement upon initiation of systemic antifungal therapy would have been observed. Oral Crohn disease should be included in the differential, but it was unlikely given the lack of granulomas on pathology and absence of history of gastrointestinal tract symptoms. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome also was unlikely given the lack of facial nerve palsy as well as the lack of granulomas on pathology. Furthermore, none of these options would be associated with tripe palms, as seen in our patient.

Acanthosis nigricans is a localized skin disorder characterized by hyperpigmented velvety plaques arising in flexural and intertriginous regions. Although most cases (80%) are associated with idiopathic or benign conditions, the link between acanthosis nigricans and an underlying malignancy has been well documented.1-3 Most commonly associated with an underlying intra-abdominal malignancy (often gastric carcinoma), the lesions of paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans are indistinguishable from their benign counterparts.1,4 When the condition presents abruptly and extensively in a nonobese patient, prompt workup for malignancy should be initiated. Rapid onset and atypical distribution (ie, palmar, perioral, or mucosal) more commonly is associated with a paraneoplastic etiology.5,6

Histopathology for acanthosis nigricans shows hyperkeratosis and epidermal papillomatosis. Horn pseudocyst formation is possible, but usually no hyperpigmentation is observed. The findings typically are indistinguishable from seborrheic keratoses, epidermal nevi, or lesions of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud.2

The underlying pathogenesis of acanthosis nigricans is poorly understood. In the benign subtype, insulin resistance commonly has been described. In the paraneoplastic subtype, it is proposed that the tumor produces a transforming growth factor that mimics epidermal growth factor and leads to keratinocyte proliferation.7,8 Paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans has the potential to arise at any point of tumor development, further contributing to the diagnostic challenge. Treatment of the skin lesions involves management of the underlying malignancy. Unfortunately, many such malignancies often are at an advanced stage, and subsequent prognosis is poor.2

- Shah A, Jack A, Liu H, et al. Neoplastic/paraneoplastic dermatitis, fasciitis, and panniculitis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2011;37:573-592.

- Chairatchaneeboon M, Kim EJ. Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes. In: Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019:2441-2464.

- Lee HC, Ker KJ, Chong WS. Oral malignant acanthosis nigricans and tripe palms associated with renal urothelial carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1381-1383.

- Yu Q, Li XL, Ji G, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: an early diagnostic clue for gastric adenocarcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2017;15:208.

- Mohrenschlager M, Vocks E, Wessner DB, et al. Tripe palms and malignant acanthosis nigricans: cutaneous signs of imminent metastasis in bladder cancer? J Urol. 2001;165:1629-1630.

- Cohen PR, Grossman ME, Almeida L, et al. Tripe palms and malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:669-678.

- Higgins SP, Freemark M, Prose NS. Acanthosis nigricans: a practical approach to evaluation and management. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:2.

- Torley D, Bellus GA, Munro CS. Genes, growth factors and acanthosis nigricans. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1096-1101.

- Shah A, Jack A, Liu H, et al. Neoplastic/paraneoplastic dermatitis, fasciitis, and panniculitis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2011;37:573-592.

- Chairatchaneeboon M, Kim EJ. Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes. In: Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019:2441-2464.

- Lee HC, Ker KJ, Chong WS. Oral malignant acanthosis nigricans and tripe palms associated with renal urothelial carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1381-1383.

- Yu Q, Li XL, Ji G, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: an early diagnostic clue for gastric adenocarcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2017;15:208.

- Mohrenschlager M, Vocks E, Wessner DB, et al. Tripe palms and malignant acanthosis nigricans: cutaneous signs of imminent metastasis in bladder cancer? J Urol. 2001;165:1629-1630.

- Cohen PR, Grossman ME, Almeida L, et al. Tripe palms and malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:669-678.

- Higgins SP, Freemark M, Prose NS. Acanthosis nigricans: a practical approach to evaluation and management. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:2.

- Torley D, Bellus GA, Munro CS. Genes, growth factors and acanthosis nigricans. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1096-1101.

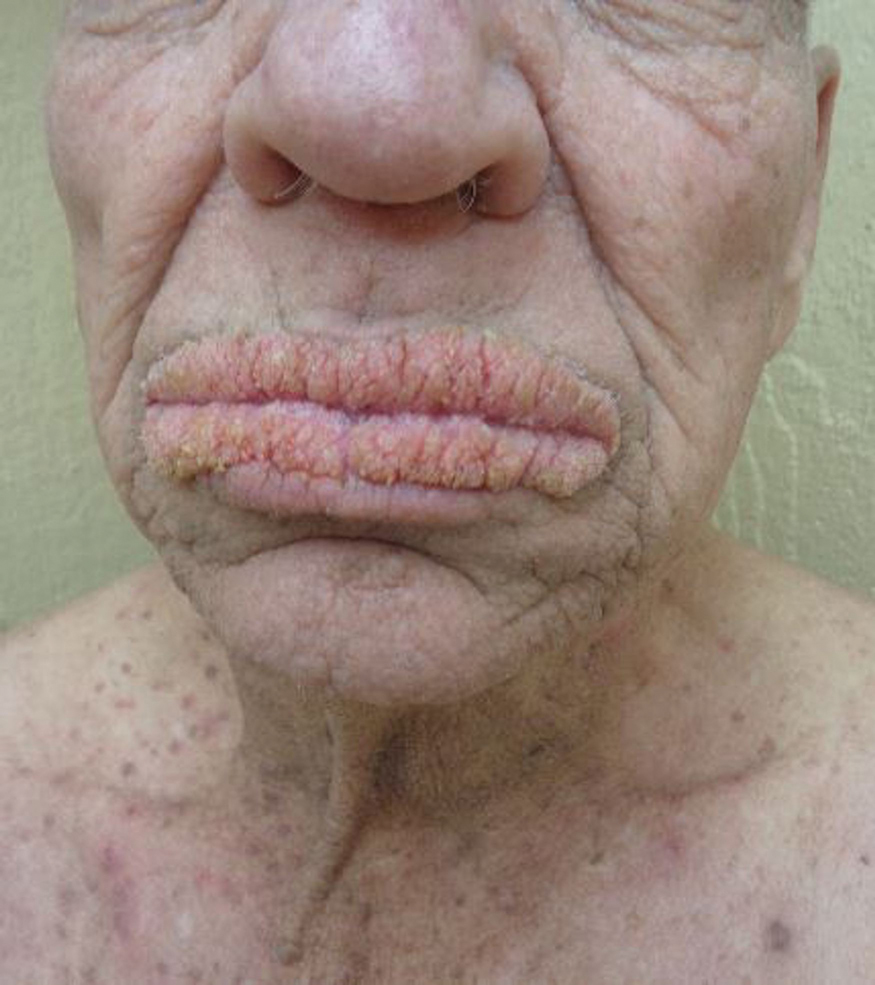

A 75-year-old nonobese man with metastatic urothelial carcinoma presented for evaluation and treatment of swollen lips. The patient stated that his lips began to swell and crack shortly after beginning pembrolizumab approximately 5 months prior. The swelling had progressively worsened, prompting discontinuation of the pembrolizumab by oncology about 2 months prior to presentation to our dermatology clinic. He reported slight improvement after the discontinuation of pembrolizumab, and he had since been started on carboplatin and gemcitabine. He previously was treated with oral corticosteroids without improvement. His oncologist started him on oral fluconazole for treatment of oral thrush on the day of presentation to our clinic. Physical examination revealed diffuse papillomatous and verrucous plaques of the upper and lower lips with involvement of the buccal mucosa. He also had deep fissures and white plaques on the tongue. Velvety hyperpigmented plaques were noted in the axillae, and he had confluent thickening of the palms. A 3-mm punch biopsy from the lower lip was performed. The patient subsequently was evaluated 2 weeks after the initial appointment, and minor improvement in the oral verrucous hyperplasia was noted following antifungal therapy, with resolution of the candidiasis.