User login

From Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Burlington, MA (Drs. Liesching and Lei), and Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (Dr. Liesching)

ABSTRACT

Objective: To compare the utilization of oxygen therapies and clinical outcomes of patients admitted for COVID-19 during the second surge of the pandemic to that of patients admitted during the first surge.

Design: Observational study using a registry database.

Setting: Three hospitals (791 inpatient beds and 76 intensive care unit [ICU] beds) within the Beth Israel Lahey Health system in Massachusetts.

Participants: We included 3183 patients with COVID-19 admitted to hospitals.

Measurements: Baseline data included demographics and comorbidities. Treatments included low-flow supplemental oxygen (2-6 L/min), high-flow oxygen via nasal cannula, and invasive mechanical ventilation. Outcomes included ICU admission, length of stay, ventilator days, and mortality.

Results: A total of 3183 patients were included: 1586 during the first surge and 1597 during the second surge. Compared to the first surge, patients admitted during the second surge had a similar rate of receiving low-flow supplemental oxygen (65.8% vs 64.1%, P = .3), a higher rate of receiving high-flow nasal cannula (15.4% vs 10.8%, P = .0001), and a lower ventilation rate (5.6% vs 9.7%, P < .0001). The outcomes during the second surge were better than those during the first surge: lower ICU admission rate (8.1% vs 12.7%, P < .0001), shorter length of hospital stay (5 vs 6 days, P < .0001), fewer ventilator days (10 vs 16, P = .01), and lower mortality (8.3% vs 19.2%, P < .0001). Among ventilated patients, those who received high-flow nasal cannula had lower mortality.

Conclusion: Compared to the first surge of the COVID-19 pandemic, patients admitted during the second surge had similar likelihood of receiving low-flow supplemental oxygen, were more likely to receive high-flow nasal cannula, were less likely to be ventilated, and had better outcomes.

Keywords: supplemental oxygen, high-flow nasal cannula, ventilator.

The respiratory system receives the major impact of SARS-CoV-2 virus, and hypoxemia has been the predominant diagnosis for patients hospitalized with COVID-19.1,2 During the initial stage of the pandemic, oxygen therapies and mechanical ventilation were the only choices for these patients.3-6 Standard-of-care treatment for patients with COVID-19 during the initial surge included oxygen therapies and mechanical ventilation for hypoxemia and medications for comorbidities and COVID-19–associated sequelae, such as multi-organ dysfunction and failure. A report from New York during the first surge (May 2020) showed that among 5700 hospitalized patients with COVID-19, 27.8% received supplemental oxygen and 12.2% received invasive mechanical ventilation.7 High-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) oxygen delivery has been utilized widely throughout the pandemic due to its superiority over other noninvasive respiratory support techniques.8-12 Mechanical ventilation is always necessary for critically ill patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. However, ventilator scarcity has become a bottleneck in caring for severely ill patients with COVID-19 during the pandemic.13

The clinical outcomes of hospitalized COVID-19 patients include a high intubation rate, long length of hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) stay, and high mortality.14,15 As the pandemic evolved, new medications, including remdesivir, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir, or interferon β-1a, were used in addition to the standard of care, but these did not result in significantly different mortality from standard of care.16 Steroids are becoming foundational to the treatment of severe COVID-19 pneumonia, but evidence from high-quality randomized controlled clinical trials is lacking.17

During the first surge from March to May 2020, Massachusetts had the third highest number of COVID-19 cases among states in the United States.18 In early 2021, COVID-19 cases were climbing close to the peak of the second surge in Massachusetts. In this study, we compared utilization of low-flow supplemental oxygen, HFNC, and mechanical ventilation and clinical outcomes of patients admitted to 3 hospitals in Massachusetts during the second surge of the pandemic to that of patients admitted during the first surge.

Methods

Setting

Beth Israel Lahey Health is a system of academic and teaching hospitals with primary care and specialty care providers. We included 3 centers within the Beth Israel Lahey Health system in Massachusetts: Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, with 335 inpatient hospital beds and 52 critical care beds; Beverly Hospital, with 227 beds and 14 critical care beds; and Winchester Hospital, with 229 beds and 10 ICU beds.

Participants

We included patients admitted to the 3 hospitals with COVID-19 as a primary or secondary diagnosis during the first surge of the pandemic (March 1, 2020 to June 15, 2020) and the second surge (November 15, 2020 to January 27, 2021). The timeframe of the first surge was defined as the window between the start date and the end date of data collection. During the time window of the first surge, 1586 patients were included. The start time of the second surge was defined as the date when the data collection was restarted; the end date was set when the number of patients (1597) accumulated was close to the number of patients in the first surge (1586), so that the two groups had similar sample size.

Study Design

A data registry of COVID-19 patients was created by our institution, and the data were prospectively collected starting in March 2020. We retrospectively extracted data on the following from the registry database for this observational study: demographics and baseline comorbidities; the use of low-flow supplemental oxygen, HFNC, and invasive mechanical ventilator; and ICU admission, length of hospital stay, length of ICU stay, and hospital discharge disposition. Start and end times for each oxygen therapy were not entered in the registry. Data about other oxygen therapies, such as noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation, were not collected in the registry database, and therefore were not included in the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables (eg, age) were tested for data distribution normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed data were tested using unpaired t-tests and displayed as mean (SD). The skewed data were tested using the Wilcoxon rank sum test and displayed as median (interquartile range [IQR]). The categorical variables were compared using chi-square test. Comparisons with P ≤ .05 were considered significantly different. Statistical analysis for this study was generated using Statistical Analysis Software (SAS), version 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc.).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

We included 3183 patients: 1586 admitted during the first surge and 1597 admitted during the second surge. Baseline characteristics of patients with COVID-19 admitted during the first and second surges are shown in Table 1. Patients admitted during the second surge were older (73 years vs 71 years, P = .01) and had higher rates of hypertension (64.8% vs 59.6%, P = .003) and asthma (12.9% vs 10.7%, P = .049) but a lower rate of interstitial lung disease (3.3% vs 7.7%, P < .001). Sequential organ failure assessment scores at admission and the rates of other comorbidities were not significantly different between the 2 surges.

Oxygen Therapies

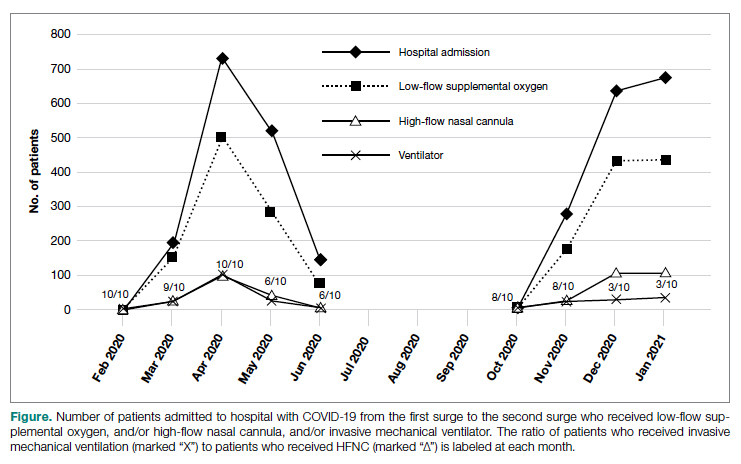

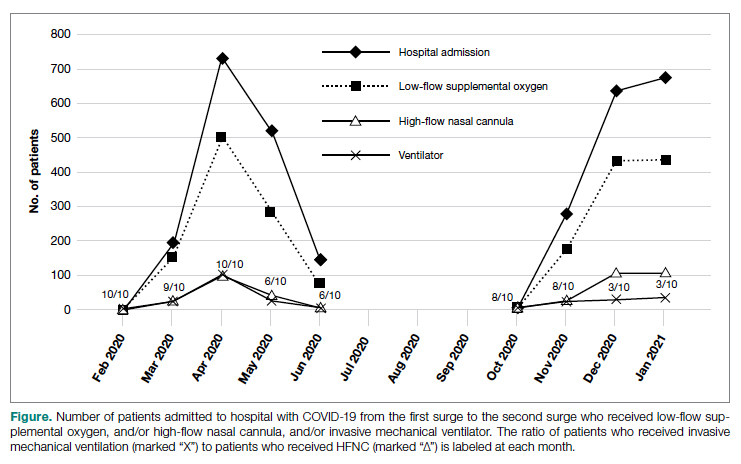

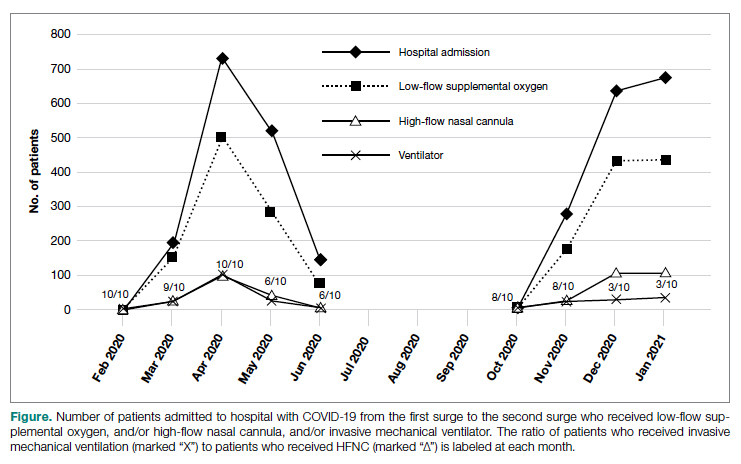

The number of patients who were hospitalized and received low-flow supplemental oxygen, and/or HFNC, and/or ventilator in the first surge and the second surge is shown in the Figure. Of all patients included, 2067 (64.9%) received low-flow supplemental oxygen; of these, 374 (18.1%) subsequently received HFNC, and 85 (22.7%) of these subsequently received mechanical ventilation. Of all 3183 patients, 417 (13.1%) received HFNC; 43 of these patients received HFNC without receiving low-flow supplemental oxygen, and 98 (23.5%) subsequently received mechanical ventilation. Out of all 3183 patients, 244 (7.7%) received mechanical ventilation; 98 (40.2%) of these received HFNC while the remaining 146 (59.8%) did not. At the beginning of the first surge, the ratio of patients who received invasive mechanical ventilation to patients who received HFNC was close to 1:1 (10/10); the ratio decreased to 6:10 in May and June 2020. At the beginning of the second surge, the ratio was 8:10 and then decreased to 3:10 in December 2020 and January 2021.

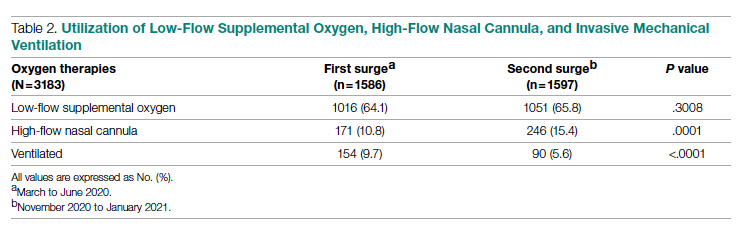

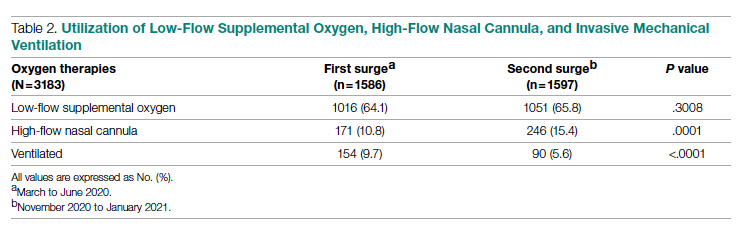

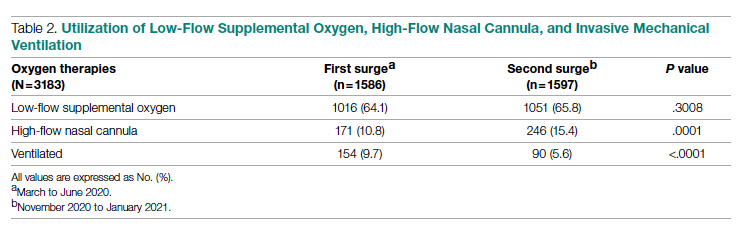

As shown in Table 2, the proportion of patients who received low-flow supplemental oxygen during the second surge was similar to that during the first surge (65.8% vs 64.1%, P = .3). Patients admitted during the second surge were more likely to receive HFNC than patients admitted during the first surge (15.4% vs 10.8%, P = .0001). Patients admitted during the second surge were less likely to be ventilated than the patients admitted during the first surge (5.6% vs 9.7%, P < .0001).

Clinical Outcomes

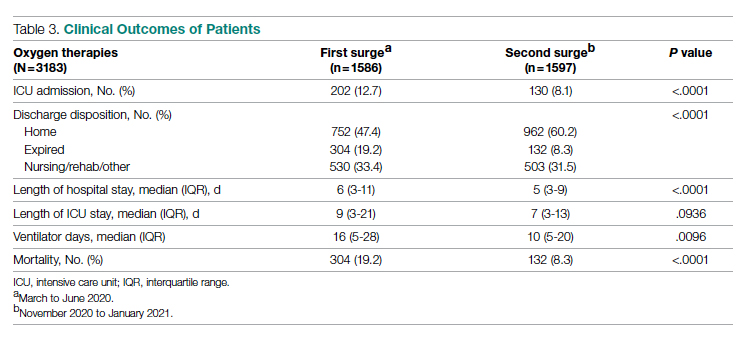

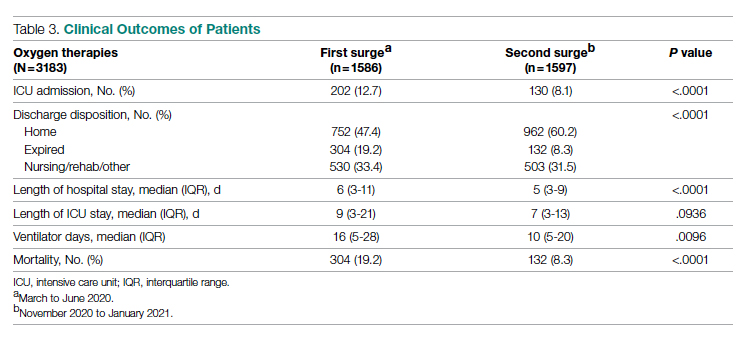

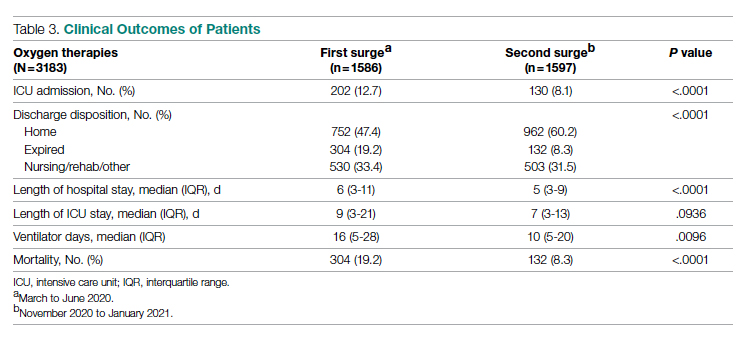

As shown in Table 3, second surge outcomes were much better than first surge outcomes: the ICU admission rate was lower (8.1% vs 12.7%, P < .0001); patients were more likely to be discharged to home (60.2% vs 47.4%, P < .0001), had a shorter length of hospital stay (5 vs 6 days, P < .0001), and had fewer ventilator days (10 vs 16, P = .01); and mortality was lower (8.3% vs 19.2%, P < .0001). There was a trend that length of ICU stay was shorter during the second surge than during the first surge (7 days vs 9 days, P = .09).

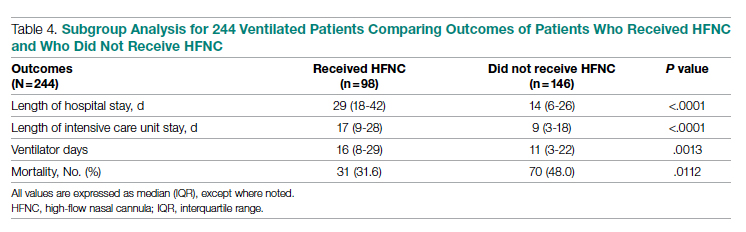

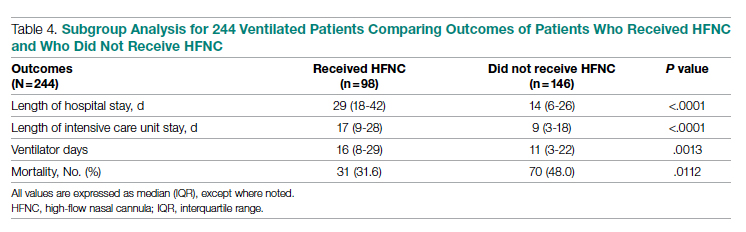

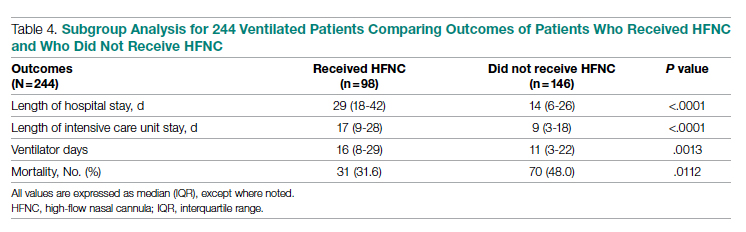

As noted (Figure), the ratio of patients who received invasive mechanical ventilation to patients who received HFNC was decreasing during both the first surge and the second surge. To further analyze the relation between ventilator and HFNC, we performed a subgroup analysis for 244 ventilated patients during both surges to compare outcomes between patients who received HFNC and those who did not receive HFNC (Table 4). Ninety-eight (40%) patients received HFNC. Ventilated patients who received HFNC had lower mortality than those patients who did not receive HFNC (31.6% vs 48%, P = .01), but had a longer length of hospital stay (29 days vs 14 days, P < .0001), longer length of ICU stay (17 days vs 9 days, P < .0001), and a higher number of ventilator days (16 vs 11, P = .001).

Discussion

Our study compared the baseline patient characteristics; utilization of low-flow supplemental oxygen therapy, HFNC, and mechanical ventilation; and clinical outcomes between the first surge (n = 1586) and the second surge (n = 1597) of the COVID-19 pandemic. During both surges, about two-thirds of admitted patients received low-flow supplemental oxygen. A higher proportion of the admitted patients received HFNC during the second surge than during the first surge, while the intubation rate was lower during the second surge than during the first surge.

Reported low-flow supplemental oxygen use ranged from 28% to 63% depending on the cohort characteristics and location during the first surge.6,7,19 A report from New York during the first surge (March 1 to April 4, 2020) showed that among 5700 hospitalized patients with COVID-19, 27.8% received low-flow supplemental oxygen.7 HFNC is recommended in guidelines on management of patients with acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19.20 In our study, HFNC was utilized in a higher proportion of patients admitted for COVID-19 during the second surge (15.5% vs 10.8%, P = .0001). During the early pandemic period in Wuhan, China, 11% to 21% of admitted COVID-19 patients received HFNC.21,22 Utilization of HFNC in New York during the first surge (March to May 2020) varied from 5% to 14.3% of patients admitted with COVID-19.23,24 Our subgroup analysis of the ventilated patients showed that patients who received HFNC had lower mortality than those who did not (31.6% vs 48.0%, P = .011). Comparably, a report from Paris, France, showed that among patients admitted to ICUs for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, those who received HFNC had lower mortality at day 60 than those who did not (21% vs 31%, P = .052).25 Our recent analysis showed that patients treated with HFNC prior to mechanical ventilation had lower mortality than those treated with only conventional oxygen (30% vs 52%, P = .05).26 In this subgroup analysis, we could not determine if HFNC treatment was administered before or after ventilation because HFNC was entered as dichotomous data (“Yes” or “No”) in the registry database. We merely showed the beneficial effect of HFNC on reducing mortality for ventilated COVID-19 patients, but did not mean to focus on how and when to apply HFNC.

We observed that the patients admitted during the second surge were less likely to be ventilated than the patients admitted during the first surge (5.6% vs 9.7%, P < .0001). During the first surge in New York, among 5700 patients admitted with COVID-19, 12.2% received invasive mechanical ventilation.7 In another report, also from New York during the first surge, 26.1% of 2015 hospitalized COVID-19 patients received mechanical ventilation.27 In our study, the ventilation rate of 9.7% during the first surge was lower.

Outcomes during the second surge were better than during the first surge, including ICU admission rate, hospital and ICU length of stay, ventilator days, and mortality. The mortality was 19.2% during the first surge vs 8.3% during the second surge (P < .0001). The mortality of 19.2% was lower than the 30.6% mortality reported for 2015 hospitalized COVID-19 patients in New York during the first surge.27 A retrospective study showed that early administration of remdesivir was associated with reduced ICU admission, ventilation use, and mortality.28 The RECOVERY clinical trial showed that dexamethasone improved mortality for COVID-19 patients who received respiratory support, but not for patients who did not receive any respiratory support.29 Perhaps some, if not all, of the improvement in ICU admission and mortality during the second surge was attributed to the new medications, such as antivirals and steroids.

The length of hospital stay for patients with moderate to severe COVID-19 varied from 4 to 53 days at different locations of the world, as shown in a meta-analysis by Rees and colleagues.30 Our results showing a length of stay of 6 days during the first surge and 5 days during the second surge fell into the shorter end of this range. In a retrospective analysis of 1643 adults with severe COVID-19 admitted to hospitals in New York City between March 9, 2020 and April 23, 2020, median hospital length of stay was 7 (IQR, 3-14) days.31 For the ventilated patients in our study, the length of stay of 14 days (did not receive HFNC) and 29 days (received HFNC) was much longer. This longer length of stay might be attributed to the patients in our study being older and having more severe comorbidities.

The main purpose of this study was to compare the oxygen therapies and outcomes between 2 surges. It is difficult to associate the clinical outcomes with the oxygen therapies because new therapies and medications were available after the first surge. It was not possible to adjust the outcomes with confounders (other therapies and medications) because the registry data did not include the new therapies and medications.

A strength of this study was that we included a large, balanced number of patients in the first surge and the second surge. We did not plan the sample size in both groups as we could not predict the number of admissions. We set the end date of data collection for analysis as the time when the number of patients admitted during the second surge was similar to the number of patients admitted during the first surge. A limitation was that the registry database was created by the institution and was not designed solely for this study. The data for oxygen therapies were limited to low-flow supplemental oxygen, HFNC, and invasive mechanical ventilation; data for noninvasive ventilation were not included.

Conclusion

At our centers, during the second surge of COVID-19 pandemic, patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection were more likely to receive HFNC but less likely to be ventilated. Compared to the first surge, the hospitalized patients with COVID-19 infection had a lower ICU admission rate, shorter length of hospital stay, fewer ventilator days, and lower mortality. For ventilated patients, those who received HFNC had lower mortality than those who did not.

Corresponding author: Timothy N. Liesching, MD, 41 Mall Road, Burlington, MA 01805; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

doi:10.12788/jcom.0086

1. Xie J, Covassin N, Fan Z, et al. Association between hypoxemia and mortality in patients with COVID-19. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(6):1138-1147. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.04.006

2. Asleh R, Asher E, Yagel O, et al. Predictors of hypoxemia and related adverse outcomes in patients hospitalized with COVID-19: a double-center retrospective study. J Clin Med. 2021;10(16):3581. doi:10.3390/jcm10163581

3. Choi KJ, Hong HL, Kim EJ. Association between oxygen saturation/fraction of inhaled oxygen and mortality in patients with COVID-19 associated pneumonia requiring oxygen therapy. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2021;84(2):125-133. doi:10.4046/trd.2020.0126

4. Dixit SB. Role of noninvasive oxygen therapy strategies in COVID-19 patients: Where are we going? Indian J Crit Care Med. 2020;24(10):897-898. doi:10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23625

5. Gonzalez-Castro A, Fajardo Campoverde A, Medina A, et al. Non-invasive mechanical ventilation and high-flow oxygen therapy in the COVID-19 pandemic: the value of a draw. Med Intensiva (Engl Ed). 2021;45(5):320-321. doi:10.1016/j.medine.2021.04.001

6. Pan W, Li J, Ou Y, et al. Clinical outcome of standardized oxygen therapy nursing strategy in COVID-19. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9(4):2171-2177. doi:10.21037/apm-20-1272

7. Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052-2059. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6775

8. He G, Han Y, Fang Q, et al. Clinical experience of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy in severe COVID-19 patients. Article in Chinese. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2020;49(2):232-239. doi:10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2020.03.13

9. Lalla U, Allwood BW, Louw EH, et al. The utility of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy in the management of respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 pneumonia. S Afr Med J. 2020;110(6):12941.

10. Zhang TT, Dai B, Wang W. Should the high-flow nasal oxygen therapy be used or avoided in COVID-19? J Transl Int Med. 2020;8(2):57-58. doi:10.2478/jtim-2020-0018

11. Agarwal A, Basmaji J, Muttalib F, et al. High-flow nasal cannula for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure in patients with COVID-19: systematic reviews of effectiveness and its risks of aerosolization, dispersion, and infection transmission. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67(9):1217-1248. doi:10.1007/s12630-020-01740-2

12. Geng S, Mei Q, Zhu C, et al. High flow nasal cannula is a good treatment option for COVID-19. Heart Lung. 2020;49(5):444-445. doi:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2020.03.018

13. Feinstein MM, Niforatos JD, Hyun I, et al. Considerations for ventilator triage during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(6):e53. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30192-2

14. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239-1242. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2648

15. Rojas-Marte G, Hashmi AT, Khalid M, et al. Outcomes in patients with COVID-19 disease and high oxygen requirements. J Clin Med Res. 2021;13(1):26-37. doi:10.14740/jocmr4405

16. Zhang R, Mylonakis E. In inpatients with COVID-19, none of remdesivir, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir, or interferon β-1a differed from standard care for in-hospital mortality. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(2):JC17. doi:10.7326/ACPJ202102160-017

17. Rello J, Waterer GW, Bourdiol A, Roquilly A. COVID-19, steroids and other immunomodulators: The jigsaw is not complete. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2020;39(6):699-701. doi:10.1016/j.accpm.2020.10.011

18. Dargin J, Stempek S, Lei Y, Gray Jr. A, Liesching T. The effect of a tiered provider staffing model on patient outcomes during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A single-center observational study. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2021;11(3). doi:10.4103/ijciis.ijciis_37_21

19. Ni YN, Wang T, Liang BM, Liang ZA. The independent factors associated with oxygen therapy in COVID-19 patients under 65 years old. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0245690. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0245690

20. Alhazzani W, Moller MH, Arabi YM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Crit Care Med. 2020;48(6):e440-e469. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000004363

21. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061-1069. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1585

22. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054-1062. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3

23. Argenziano MG, Bruce SL, Slater CL, et al. Characterization and clinical course of 1000 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York: retrospective case series. BMJ. 2020;369:m1996. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1996

24. Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1763-1770. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2

25. Demoule A, Vieillard Baron A, Darmon M, et al. High-flow nasal cannula in critically ill patients with severe COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(7):1039-1042. doi:10.1164/rccm.202005-2007LE

26. Hansen CK, Stempek S, Liesching T, Lei Y, Dargin J. Characteristics and outcomes of patients receiving high flow nasal cannula therapy prior to mechanical ventilation in COVID-19 respiratory failure: a prospective observational study. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2021;11(2):56-60. doi:10.4103/IJCIIS.IJCIIS_181_20

27. van Gerwen M, Alsen M, Little C, et al. Risk factors and outcomes of COVID-19 in New York City; a retrospective cohort study. J Med Virol. 2021;93(2):907-915. doi:10.1002/jmv.26337

28. Hussain Alsayed HA, Saheb Sharif-Askari F, Saheb Sharif-Askari N, Hussain AAS, Hamid Q, Halwani R. Early administration of remdesivir to COVID-19 patients associates with higher recovery rate and lower need for ICU admission: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0258643. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0258643

29. RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P, Lim WS, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):693-704. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2021436

30. Rees EM, Nightingale ES, Jafari Y, et al. COVID-19 length of hospital stay: a systematic review and data synthesis. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):270. doi:10.1186/s12916-020-01726-3

31. Anderson M, Bach P, Baldwin MR. Hospital length of stay for severe COVID-19: implications for Remdesivir’s value. medRxiv. 2020;2020.08.10.20171637. doi:10.1101/2020.08.10.20171637

From Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Burlington, MA (Drs. Liesching and Lei), and Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (Dr. Liesching)

ABSTRACT

Objective: To compare the utilization of oxygen therapies and clinical outcomes of patients admitted for COVID-19 during the second surge of the pandemic to that of patients admitted during the first surge.

Design: Observational study using a registry database.

Setting: Three hospitals (791 inpatient beds and 76 intensive care unit [ICU] beds) within the Beth Israel Lahey Health system in Massachusetts.

Participants: We included 3183 patients with COVID-19 admitted to hospitals.

Measurements: Baseline data included demographics and comorbidities. Treatments included low-flow supplemental oxygen (2-6 L/min), high-flow oxygen via nasal cannula, and invasive mechanical ventilation. Outcomes included ICU admission, length of stay, ventilator days, and mortality.

Results: A total of 3183 patients were included: 1586 during the first surge and 1597 during the second surge. Compared to the first surge, patients admitted during the second surge had a similar rate of receiving low-flow supplemental oxygen (65.8% vs 64.1%, P = .3), a higher rate of receiving high-flow nasal cannula (15.4% vs 10.8%, P = .0001), and a lower ventilation rate (5.6% vs 9.7%, P < .0001). The outcomes during the second surge were better than those during the first surge: lower ICU admission rate (8.1% vs 12.7%, P < .0001), shorter length of hospital stay (5 vs 6 days, P < .0001), fewer ventilator days (10 vs 16, P = .01), and lower mortality (8.3% vs 19.2%, P < .0001). Among ventilated patients, those who received high-flow nasal cannula had lower mortality.

Conclusion: Compared to the first surge of the COVID-19 pandemic, patients admitted during the second surge had similar likelihood of receiving low-flow supplemental oxygen, were more likely to receive high-flow nasal cannula, were less likely to be ventilated, and had better outcomes.

Keywords: supplemental oxygen, high-flow nasal cannula, ventilator.

The respiratory system receives the major impact of SARS-CoV-2 virus, and hypoxemia has been the predominant diagnosis for patients hospitalized with COVID-19.1,2 During the initial stage of the pandemic, oxygen therapies and mechanical ventilation were the only choices for these patients.3-6 Standard-of-care treatment for patients with COVID-19 during the initial surge included oxygen therapies and mechanical ventilation for hypoxemia and medications for comorbidities and COVID-19–associated sequelae, such as multi-organ dysfunction and failure. A report from New York during the first surge (May 2020) showed that among 5700 hospitalized patients with COVID-19, 27.8% received supplemental oxygen and 12.2% received invasive mechanical ventilation.7 High-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) oxygen delivery has been utilized widely throughout the pandemic due to its superiority over other noninvasive respiratory support techniques.8-12 Mechanical ventilation is always necessary for critically ill patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. However, ventilator scarcity has become a bottleneck in caring for severely ill patients with COVID-19 during the pandemic.13

The clinical outcomes of hospitalized COVID-19 patients include a high intubation rate, long length of hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) stay, and high mortality.14,15 As the pandemic evolved, new medications, including remdesivir, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir, or interferon β-1a, were used in addition to the standard of care, but these did not result in significantly different mortality from standard of care.16 Steroids are becoming foundational to the treatment of severe COVID-19 pneumonia, but evidence from high-quality randomized controlled clinical trials is lacking.17

During the first surge from March to May 2020, Massachusetts had the third highest number of COVID-19 cases among states in the United States.18 In early 2021, COVID-19 cases were climbing close to the peak of the second surge in Massachusetts. In this study, we compared utilization of low-flow supplemental oxygen, HFNC, and mechanical ventilation and clinical outcomes of patients admitted to 3 hospitals in Massachusetts during the second surge of the pandemic to that of patients admitted during the first surge.

Methods

Setting

Beth Israel Lahey Health is a system of academic and teaching hospitals with primary care and specialty care providers. We included 3 centers within the Beth Israel Lahey Health system in Massachusetts: Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, with 335 inpatient hospital beds and 52 critical care beds; Beverly Hospital, with 227 beds and 14 critical care beds; and Winchester Hospital, with 229 beds and 10 ICU beds.

Participants

We included patients admitted to the 3 hospitals with COVID-19 as a primary or secondary diagnosis during the first surge of the pandemic (March 1, 2020 to June 15, 2020) and the second surge (November 15, 2020 to January 27, 2021). The timeframe of the first surge was defined as the window between the start date and the end date of data collection. During the time window of the first surge, 1586 patients were included. The start time of the second surge was defined as the date when the data collection was restarted; the end date was set when the number of patients (1597) accumulated was close to the number of patients in the first surge (1586), so that the two groups had similar sample size.

Study Design

A data registry of COVID-19 patients was created by our institution, and the data were prospectively collected starting in March 2020. We retrospectively extracted data on the following from the registry database for this observational study: demographics and baseline comorbidities; the use of low-flow supplemental oxygen, HFNC, and invasive mechanical ventilator; and ICU admission, length of hospital stay, length of ICU stay, and hospital discharge disposition. Start and end times for each oxygen therapy were not entered in the registry. Data about other oxygen therapies, such as noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation, were not collected in the registry database, and therefore were not included in the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables (eg, age) were tested for data distribution normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed data were tested using unpaired t-tests and displayed as mean (SD). The skewed data were tested using the Wilcoxon rank sum test and displayed as median (interquartile range [IQR]). The categorical variables were compared using chi-square test. Comparisons with P ≤ .05 were considered significantly different. Statistical analysis for this study was generated using Statistical Analysis Software (SAS), version 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc.).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

We included 3183 patients: 1586 admitted during the first surge and 1597 admitted during the second surge. Baseline characteristics of patients with COVID-19 admitted during the first and second surges are shown in Table 1. Patients admitted during the second surge were older (73 years vs 71 years, P = .01) and had higher rates of hypertension (64.8% vs 59.6%, P = .003) and asthma (12.9% vs 10.7%, P = .049) but a lower rate of interstitial lung disease (3.3% vs 7.7%, P < .001). Sequential organ failure assessment scores at admission and the rates of other comorbidities were not significantly different between the 2 surges.

Oxygen Therapies

The number of patients who were hospitalized and received low-flow supplemental oxygen, and/or HFNC, and/or ventilator in the first surge and the second surge is shown in the Figure. Of all patients included, 2067 (64.9%) received low-flow supplemental oxygen; of these, 374 (18.1%) subsequently received HFNC, and 85 (22.7%) of these subsequently received mechanical ventilation. Of all 3183 patients, 417 (13.1%) received HFNC; 43 of these patients received HFNC without receiving low-flow supplemental oxygen, and 98 (23.5%) subsequently received mechanical ventilation. Out of all 3183 patients, 244 (7.7%) received mechanical ventilation; 98 (40.2%) of these received HFNC while the remaining 146 (59.8%) did not. At the beginning of the first surge, the ratio of patients who received invasive mechanical ventilation to patients who received HFNC was close to 1:1 (10/10); the ratio decreased to 6:10 in May and June 2020. At the beginning of the second surge, the ratio was 8:10 and then decreased to 3:10 in December 2020 and January 2021.

As shown in Table 2, the proportion of patients who received low-flow supplemental oxygen during the second surge was similar to that during the first surge (65.8% vs 64.1%, P = .3). Patients admitted during the second surge were more likely to receive HFNC than patients admitted during the first surge (15.4% vs 10.8%, P = .0001). Patients admitted during the second surge were less likely to be ventilated than the patients admitted during the first surge (5.6% vs 9.7%, P < .0001).

Clinical Outcomes

As shown in Table 3, second surge outcomes were much better than first surge outcomes: the ICU admission rate was lower (8.1% vs 12.7%, P < .0001); patients were more likely to be discharged to home (60.2% vs 47.4%, P < .0001), had a shorter length of hospital stay (5 vs 6 days, P < .0001), and had fewer ventilator days (10 vs 16, P = .01); and mortality was lower (8.3% vs 19.2%, P < .0001). There was a trend that length of ICU stay was shorter during the second surge than during the first surge (7 days vs 9 days, P = .09).

As noted (Figure), the ratio of patients who received invasive mechanical ventilation to patients who received HFNC was decreasing during both the first surge and the second surge. To further analyze the relation between ventilator and HFNC, we performed a subgroup analysis for 244 ventilated patients during both surges to compare outcomes between patients who received HFNC and those who did not receive HFNC (Table 4). Ninety-eight (40%) patients received HFNC. Ventilated patients who received HFNC had lower mortality than those patients who did not receive HFNC (31.6% vs 48%, P = .01), but had a longer length of hospital stay (29 days vs 14 days, P < .0001), longer length of ICU stay (17 days vs 9 days, P < .0001), and a higher number of ventilator days (16 vs 11, P = .001).

Discussion

Our study compared the baseline patient characteristics; utilization of low-flow supplemental oxygen therapy, HFNC, and mechanical ventilation; and clinical outcomes between the first surge (n = 1586) and the second surge (n = 1597) of the COVID-19 pandemic. During both surges, about two-thirds of admitted patients received low-flow supplemental oxygen. A higher proportion of the admitted patients received HFNC during the second surge than during the first surge, while the intubation rate was lower during the second surge than during the first surge.

Reported low-flow supplemental oxygen use ranged from 28% to 63% depending on the cohort characteristics and location during the first surge.6,7,19 A report from New York during the first surge (March 1 to April 4, 2020) showed that among 5700 hospitalized patients with COVID-19, 27.8% received low-flow supplemental oxygen.7 HFNC is recommended in guidelines on management of patients with acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19.20 In our study, HFNC was utilized in a higher proportion of patients admitted for COVID-19 during the second surge (15.5% vs 10.8%, P = .0001). During the early pandemic period in Wuhan, China, 11% to 21% of admitted COVID-19 patients received HFNC.21,22 Utilization of HFNC in New York during the first surge (March to May 2020) varied from 5% to 14.3% of patients admitted with COVID-19.23,24 Our subgroup analysis of the ventilated patients showed that patients who received HFNC had lower mortality than those who did not (31.6% vs 48.0%, P = .011). Comparably, a report from Paris, France, showed that among patients admitted to ICUs for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, those who received HFNC had lower mortality at day 60 than those who did not (21% vs 31%, P = .052).25 Our recent analysis showed that patients treated with HFNC prior to mechanical ventilation had lower mortality than those treated with only conventional oxygen (30% vs 52%, P = .05).26 In this subgroup analysis, we could not determine if HFNC treatment was administered before or after ventilation because HFNC was entered as dichotomous data (“Yes” or “No”) in the registry database. We merely showed the beneficial effect of HFNC on reducing mortality for ventilated COVID-19 patients, but did not mean to focus on how and when to apply HFNC.

We observed that the patients admitted during the second surge were less likely to be ventilated than the patients admitted during the first surge (5.6% vs 9.7%, P < .0001). During the first surge in New York, among 5700 patients admitted with COVID-19, 12.2% received invasive mechanical ventilation.7 In another report, also from New York during the first surge, 26.1% of 2015 hospitalized COVID-19 patients received mechanical ventilation.27 In our study, the ventilation rate of 9.7% during the first surge was lower.

Outcomes during the second surge were better than during the first surge, including ICU admission rate, hospital and ICU length of stay, ventilator days, and mortality. The mortality was 19.2% during the first surge vs 8.3% during the second surge (P < .0001). The mortality of 19.2% was lower than the 30.6% mortality reported for 2015 hospitalized COVID-19 patients in New York during the first surge.27 A retrospective study showed that early administration of remdesivir was associated with reduced ICU admission, ventilation use, and mortality.28 The RECOVERY clinical trial showed that dexamethasone improved mortality for COVID-19 patients who received respiratory support, but not for patients who did not receive any respiratory support.29 Perhaps some, if not all, of the improvement in ICU admission and mortality during the second surge was attributed to the new medications, such as antivirals and steroids.

The length of hospital stay for patients with moderate to severe COVID-19 varied from 4 to 53 days at different locations of the world, as shown in a meta-analysis by Rees and colleagues.30 Our results showing a length of stay of 6 days during the first surge and 5 days during the second surge fell into the shorter end of this range. In a retrospective analysis of 1643 adults with severe COVID-19 admitted to hospitals in New York City between March 9, 2020 and April 23, 2020, median hospital length of stay was 7 (IQR, 3-14) days.31 For the ventilated patients in our study, the length of stay of 14 days (did not receive HFNC) and 29 days (received HFNC) was much longer. This longer length of stay might be attributed to the patients in our study being older and having more severe comorbidities.

The main purpose of this study was to compare the oxygen therapies and outcomes between 2 surges. It is difficult to associate the clinical outcomes with the oxygen therapies because new therapies and medications were available after the first surge. It was not possible to adjust the outcomes with confounders (other therapies and medications) because the registry data did not include the new therapies and medications.

A strength of this study was that we included a large, balanced number of patients in the first surge and the second surge. We did not plan the sample size in both groups as we could not predict the number of admissions. We set the end date of data collection for analysis as the time when the number of patients admitted during the second surge was similar to the number of patients admitted during the first surge. A limitation was that the registry database was created by the institution and was not designed solely for this study. The data for oxygen therapies were limited to low-flow supplemental oxygen, HFNC, and invasive mechanical ventilation; data for noninvasive ventilation were not included.

Conclusion

At our centers, during the second surge of COVID-19 pandemic, patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection were more likely to receive HFNC but less likely to be ventilated. Compared to the first surge, the hospitalized patients with COVID-19 infection had a lower ICU admission rate, shorter length of hospital stay, fewer ventilator days, and lower mortality. For ventilated patients, those who received HFNC had lower mortality than those who did not.

Corresponding author: Timothy N. Liesching, MD, 41 Mall Road, Burlington, MA 01805; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

doi:10.12788/jcom.0086

From Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Burlington, MA (Drs. Liesching and Lei), and Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (Dr. Liesching)

ABSTRACT

Objective: To compare the utilization of oxygen therapies and clinical outcomes of patients admitted for COVID-19 during the second surge of the pandemic to that of patients admitted during the first surge.

Design: Observational study using a registry database.

Setting: Three hospitals (791 inpatient beds and 76 intensive care unit [ICU] beds) within the Beth Israel Lahey Health system in Massachusetts.

Participants: We included 3183 patients with COVID-19 admitted to hospitals.

Measurements: Baseline data included demographics and comorbidities. Treatments included low-flow supplemental oxygen (2-6 L/min), high-flow oxygen via nasal cannula, and invasive mechanical ventilation. Outcomes included ICU admission, length of stay, ventilator days, and mortality.

Results: A total of 3183 patients were included: 1586 during the first surge and 1597 during the second surge. Compared to the first surge, patients admitted during the second surge had a similar rate of receiving low-flow supplemental oxygen (65.8% vs 64.1%, P = .3), a higher rate of receiving high-flow nasal cannula (15.4% vs 10.8%, P = .0001), and a lower ventilation rate (5.6% vs 9.7%, P < .0001). The outcomes during the second surge were better than those during the first surge: lower ICU admission rate (8.1% vs 12.7%, P < .0001), shorter length of hospital stay (5 vs 6 days, P < .0001), fewer ventilator days (10 vs 16, P = .01), and lower mortality (8.3% vs 19.2%, P < .0001). Among ventilated patients, those who received high-flow nasal cannula had lower mortality.

Conclusion: Compared to the first surge of the COVID-19 pandemic, patients admitted during the second surge had similar likelihood of receiving low-flow supplemental oxygen, were more likely to receive high-flow nasal cannula, were less likely to be ventilated, and had better outcomes.

Keywords: supplemental oxygen, high-flow nasal cannula, ventilator.

The respiratory system receives the major impact of SARS-CoV-2 virus, and hypoxemia has been the predominant diagnosis for patients hospitalized with COVID-19.1,2 During the initial stage of the pandemic, oxygen therapies and mechanical ventilation were the only choices for these patients.3-6 Standard-of-care treatment for patients with COVID-19 during the initial surge included oxygen therapies and mechanical ventilation for hypoxemia and medications for comorbidities and COVID-19–associated sequelae, such as multi-organ dysfunction and failure. A report from New York during the first surge (May 2020) showed that among 5700 hospitalized patients with COVID-19, 27.8% received supplemental oxygen and 12.2% received invasive mechanical ventilation.7 High-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) oxygen delivery has been utilized widely throughout the pandemic due to its superiority over other noninvasive respiratory support techniques.8-12 Mechanical ventilation is always necessary for critically ill patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. However, ventilator scarcity has become a bottleneck in caring for severely ill patients with COVID-19 during the pandemic.13

The clinical outcomes of hospitalized COVID-19 patients include a high intubation rate, long length of hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) stay, and high mortality.14,15 As the pandemic evolved, new medications, including remdesivir, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir, or interferon β-1a, were used in addition to the standard of care, but these did not result in significantly different mortality from standard of care.16 Steroids are becoming foundational to the treatment of severe COVID-19 pneumonia, but evidence from high-quality randomized controlled clinical trials is lacking.17

During the first surge from March to May 2020, Massachusetts had the third highest number of COVID-19 cases among states in the United States.18 In early 2021, COVID-19 cases were climbing close to the peak of the second surge in Massachusetts. In this study, we compared utilization of low-flow supplemental oxygen, HFNC, and mechanical ventilation and clinical outcomes of patients admitted to 3 hospitals in Massachusetts during the second surge of the pandemic to that of patients admitted during the first surge.

Methods

Setting

Beth Israel Lahey Health is a system of academic and teaching hospitals with primary care and specialty care providers. We included 3 centers within the Beth Israel Lahey Health system in Massachusetts: Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, with 335 inpatient hospital beds and 52 critical care beds; Beverly Hospital, with 227 beds and 14 critical care beds; and Winchester Hospital, with 229 beds and 10 ICU beds.

Participants

We included patients admitted to the 3 hospitals with COVID-19 as a primary or secondary diagnosis during the first surge of the pandemic (March 1, 2020 to June 15, 2020) and the second surge (November 15, 2020 to January 27, 2021). The timeframe of the first surge was defined as the window between the start date and the end date of data collection. During the time window of the first surge, 1586 patients were included. The start time of the second surge was defined as the date when the data collection was restarted; the end date was set when the number of patients (1597) accumulated was close to the number of patients in the first surge (1586), so that the two groups had similar sample size.

Study Design

A data registry of COVID-19 patients was created by our institution, and the data were prospectively collected starting in March 2020. We retrospectively extracted data on the following from the registry database for this observational study: demographics and baseline comorbidities; the use of low-flow supplemental oxygen, HFNC, and invasive mechanical ventilator; and ICU admission, length of hospital stay, length of ICU stay, and hospital discharge disposition. Start and end times for each oxygen therapy were not entered in the registry. Data about other oxygen therapies, such as noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation, were not collected in the registry database, and therefore were not included in the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables (eg, age) were tested for data distribution normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed data were tested using unpaired t-tests and displayed as mean (SD). The skewed data were tested using the Wilcoxon rank sum test and displayed as median (interquartile range [IQR]). The categorical variables were compared using chi-square test. Comparisons with P ≤ .05 were considered significantly different. Statistical analysis for this study was generated using Statistical Analysis Software (SAS), version 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc.).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

We included 3183 patients: 1586 admitted during the first surge and 1597 admitted during the second surge. Baseline characteristics of patients with COVID-19 admitted during the first and second surges are shown in Table 1. Patients admitted during the second surge were older (73 years vs 71 years, P = .01) and had higher rates of hypertension (64.8% vs 59.6%, P = .003) and asthma (12.9% vs 10.7%, P = .049) but a lower rate of interstitial lung disease (3.3% vs 7.7%, P < .001). Sequential organ failure assessment scores at admission and the rates of other comorbidities were not significantly different between the 2 surges.

Oxygen Therapies

The number of patients who were hospitalized and received low-flow supplemental oxygen, and/or HFNC, and/or ventilator in the first surge and the second surge is shown in the Figure. Of all patients included, 2067 (64.9%) received low-flow supplemental oxygen; of these, 374 (18.1%) subsequently received HFNC, and 85 (22.7%) of these subsequently received mechanical ventilation. Of all 3183 patients, 417 (13.1%) received HFNC; 43 of these patients received HFNC without receiving low-flow supplemental oxygen, and 98 (23.5%) subsequently received mechanical ventilation. Out of all 3183 patients, 244 (7.7%) received mechanical ventilation; 98 (40.2%) of these received HFNC while the remaining 146 (59.8%) did not. At the beginning of the first surge, the ratio of patients who received invasive mechanical ventilation to patients who received HFNC was close to 1:1 (10/10); the ratio decreased to 6:10 in May and June 2020. At the beginning of the second surge, the ratio was 8:10 and then decreased to 3:10 in December 2020 and January 2021.

As shown in Table 2, the proportion of patients who received low-flow supplemental oxygen during the second surge was similar to that during the first surge (65.8% vs 64.1%, P = .3). Patients admitted during the second surge were more likely to receive HFNC than patients admitted during the first surge (15.4% vs 10.8%, P = .0001). Patients admitted during the second surge were less likely to be ventilated than the patients admitted during the first surge (5.6% vs 9.7%, P < .0001).

Clinical Outcomes

As shown in Table 3, second surge outcomes were much better than first surge outcomes: the ICU admission rate was lower (8.1% vs 12.7%, P < .0001); patients were more likely to be discharged to home (60.2% vs 47.4%, P < .0001), had a shorter length of hospital stay (5 vs 6 days, P < .0001), and had fewer ventilator days (10 vs 16, P = .01); and mortality was lower (8.3% vs 19.2%, P < .0001). There was a trend that length of ICU stay was shorter during the second surge than during the first surge (7 days vs 9 days, P = .09).

As noted (Figure), the ratio of patients who received invasive mechanical ventilation to patients who received HFNC was decreasing during both the first surge and the second surge. To further analyze the relation between ventilator and HFNC, we performed a subgroup analysis for 244 ventilated patients during both surges to compare outcomes between patients who received HFNC and those who did not receive HFNC (Table 4). Ninety-eight (40%) patients received HFNC. Ventilated patients who received HFNC had lower mortality than those patients who did not receive HFNC (31.6% vs 48%, P = .01), but had a longer length of hospital stay (29 days vs 14 days, P < .0001), longer length of ICU stay (17 days vs 9 days, P < .0001), and a higher number of ventilator days (16 vs 11, P = .001).

Discussion

Our study compared the baseline patient characteristics; utilization of low-flow supplemental oxygen therapy, HFNC, and mechanical ventilation; and clinical outcomes between the first surge (n = 1586) and the second surge (n = 1597) of the COVID-19 pandemic. During both surges, about two-thirds of admitted patients received low-flow supplemental oxygen. A higher proportion of the admitted patients received HFNC during the second surge than during the first surge, while the intubation rate was lower during the second surge than during the first surge.

Reported low-flow supplemental oxygen use ranged from 28% to 63% depending on the cohort characteristics and location during the first surge.6,7,19 A report from New York during the first surge (March 1 to April 4, 2020) showed that among 5700 hospitalized patients with COVID-19, 27.8% received low-flow supplemental oxygen.7 HFNC is recommended in guidelines on management of patients with acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19.20 In our study, HFNC was utilized in a higher proportion of patients admitted for COVID-19 during the second surge (15.5% vs 10.8%, P = .0001). During the early pandemic period in Wuhan, China, 11% to 21% of admitted COVID-19 patients received HFNC.21,22 Utilization of HFNC in New York during the first surge (March to May 2020) varied from 5% to 14.3% of patients admitted with COVID-19.23,24 Our subgroup analysis of the ventilated patients showed that patients who received HFNC had lower mortality than those who did not (31.6% vs 48.0%, P = .011). Comparably, a report from Paris, France, showed that among patients admitted to ICUs for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, those who received HFNC had lower mortality at day 60 than those who did not (21% vs 31%, P = .052).25 Our recent analysis showed that patients treated with HFNC prior to mechanical ventilation had lower mortality than those treated with only conventional oxygen (30% vs 52%, P = .05).26 In this subgroup analysis, we could not determine if HFNC treatment was administered before or after ventilation because HFNC was entered as dichotomous data (“Yes” or “No”) in the registry database. We merely showed the beneficial effect of HFNC on reducing mortality for ventilated COVID-19 patients, but did not mean to focus on how and when to apply HFNC.

We observed that the patients admitted during the second surge were less likely to be ventilated than the patients admitted during the first surge (5.6% vs 9.7%, P < .0001). During the first surge in New York, among 5700 patients admitted with COVID-19, 12.2% received invasive mechanical ventilation.7 In another report, also from New York during the first surge, 26.1% of 2015 hospitalized COVID-19 patients received mechanical ventilation.27 In our study, the ventilation rate of 9.7% during the first surge was lower.

Outcomes during the second surge were better than during the first surge, including ICU admission rate, hospital and ICU length of stay, ventilator days, and mortality. The mortality was 19.2% during the first surge vs 8.3% during the second surge (P < .0001). The mortality of 19.2% was lower than the 30.6% mortality reported for 2015 hospitalized COVID-19 patients in New York during the first surge.27 A retrospective study showed that early administration of remdesivir was associated with reduced ICU admission, ventilation use, and mortality.28 The RECOVERY clinical trial showed that dexamethasone improved mortality for COVID-19 patients who received respiratory support, but not for patients who did not receive any respiratory support.29 Perhaps some, if not all, of the improvement in ICU admission and mortality during the second surge was attributed to the new medications, such as antivirals and steroids.

The length of hospital stay for patients with moderate to severe COVID-19 varied from 4 to 53 days at different locations of the world, as shown in a meta-analysis by Rees and colleagues.30 Our results showing a length of stay of 6 days during the first surge and 5 days during the second surge fell into the shorter end of this range. In a retrospective analysis of 1643 adults with severe COVID-19 admitted to hospitals in New York City between March 9, 2020 and April 23, 2020, median hospital length of stay was 7 (IQR, 3-14) days.31 For the ventilated patients in our study, the length of stay of 14 days (did not receive HFNC) and 29 days (received HFNC) was much longer. This longer length of stay might be attributed to the patients in our study being older and having more severe comorbidities.

The main purpose of this study was to compare the oxygen therapies and outcomes between 2 surges. It is difficult to associate the clinical outcomes with the oxygen therapies because new therapies and medications were available after the first surge. It was not possible to adjust the outcomes with confounders (other therapies and medications) because the registry data did not include the new therapies and medications.

A strength of this study was that we included a large, balanced number of patients in the first surge and the second surge. We did not plan the sample size in both groups as we could not predict the number of admissions. We set the end date of data collection for analysis as the time when the number of patients admitted during the second surge was similar to the number of patients admitted during the first surge. A limitation was that the registry database was created by the institution and was not designed solely for this study. The data for oxygen therapies were limited to low-flow supplemental oxygen, HFNC, and invasive mechanical ventilation; data for noninvasive ventilation were not included.

Conclusion

At our centers, during the second surge of COVID-19 pandemic, patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection were more likely to receive HFNC but less likely to be ventilated. Compared to the first surge, the hospitalized patients with COVID-19 infection had a lower ICU admission rate, shorter length of hospital stay, fewer ventilator days, and lower mortality. For ventilated patients, those who received HFNC had lower mortality than those who did not.

Corresponding author: Timothy N. Liesching, MD, 41 Mall Road, Burlington, MA 01805; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

doi:10.12788/jcom.0086

1. Xie J, Covassin N, Fan Z, et al. Association between hypoxemia and mortality in patients with COVID-19. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(6):1138-1147. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.04.006

2. Asleh R, Asher E, Yagel O, et al. Predictors of hypoxemia and related adverse outcomes in patients hospitalized with COVID-19: a double-center retrospective study. J Clin Med. 2021;10(16):3581. doi:10.3390/jcm10163581

3. Choi KJ, Hong HL, Kim EJ. Association between oxygen saturation/fraction of inhaled oxygen and mortality in patients with COVID-19 associated pneumonia requiring oxygen therapy. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2021;84(2):125-133. doi:10.4046/trd.2020.0126

4. Dixit SB. Role of noninvasive oxygen therapy strategies in COVID-19 patients: Where are we going? Indian J Crit Care Med. 2020;24(10):897-898. doi:10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23625

5. Gonzalez-Castro A, Fajardo Campoverde A, Medina A, et al. Non-invasive mechanical ventilation and high-flow oxygen therapy in the COVID-19 pandemic: the value of a draw. Med Intensiva (Engl Ed). 2021;45(5):320-321. doi:10.1016/j.medine.2021.04.001

6. Pan W, Li J, Ou Y, et al. Clinical outcome of standardized oxygen therapy nursing strategy in COVID-19. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9(4):2171-2177. doi:10.21037/apm-20-1272

7. Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052-2059. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6775

8. He G, Han Y, Fang Q, et al. Clinical experience of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy in severe COVID-19 patients. Article in Chinese. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2020;49(2):232-239. doi:10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2020.03.13

9. Lalla U, Allwood BW, Louw EH, et al. The utility of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy in the management of respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 pneumonia. S Afr Med J. 2020;110(6):12941.

10. Zhang TT, Dai B, Wang W. Should the high-flow nasal oxygen therapy be used or avoided in COVID-19? J Transl Int Med. 2020;8(2):57-58. doi:10.2478/jtim-2020-0018

11. Agarwal A, Basmaji J, Muttalib F, et al. High-flow nasal cannula for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure in patients with COVID-19: systematic reviews of effectiveness and its risks of aerosolization, dispersion, and infection transmission. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67(9):1217-1248. doi:10.1007/s12630-020-01740-2

12. Geng S, Mei Q, Zhu C, et al. High flow nasal cannula is a good treatment option for COVID-19. Heart Lung. 2020;49(5):444-445. doi:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2020.03.018

13. Feinstein MM, Niforatos JD, Hyun I, et al. Considerations for ventilator triage during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(6):e53. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30192-2

14. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239-1242. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2648

15. Rojas-Marte G, Hashmi AT, Khalid M, et al. Outcomes in patients with COVID-19 disease and high oxygen requirements. J Clin Med Res. 2021;13(1):26-37. doi:10.14740/jocmr4405

16. Zhang R, Mylonakis E. In inpatients with COVID-19, none of remdesivir, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir, or interferon β-1a differed from standard care for in-hospital mortality. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(2):JC17. doi:10.7326/ACPJ202102160-017

17. Rello J, Waterer GW, Bourdiol A, Roquilly A. COVID-19, steroids and other immunomodulators: The jigsaw is not complete. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2020;39(6):699-701. doi:10.1016/j.accpm.2020.10.011

18. Dargin J, Stempek S, Lei Y, Gray Jr. A, Liesching T. The effect of a tiered provider staffing model on patient outcomes during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A single-center observational study. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2021;11(3). doi:10.4103/ijciis.ijciis_37_21

19. Ni YN, Wang T, Liang BM, Liang ZA. The independent factors associated with oxygen therapy in COVID-19 patients under 65 years old. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0245690. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0245690

20. Alhazzani W, Moller MH, Arabi YM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Crit Care Med. 2020;48(6):e440-e469. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000004363

21. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061-1069. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1585

22. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054-1062. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3

23. Argenziano MG, Bruce SL, Slater CL, et al. Characterization and clinical course of 1000 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York: retrospective case series. BMJ. 2020;369:m1996. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1996

24. Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1763-1770. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2

25. Demoule A, Vieillard Baron A, Darmon M, et al. High-flow nasal cannula in critically ill patients with severe COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(7):1039-1042. doi:10.1164/rccm.202005-2007LE

26. Hansen CK, Stempek S, Liesching T, Lei Y, Dargin J. Characteristics and outcomes of patients receiving high flow nasal cannula therapy prior to mechanical ventilation in COVID-19 respiratory failure: a prospective observational study. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2021;11(2):56-60. doi:10.4103/IJCIIS.IJCIIS_181_20

27. van Gerwen M, Alsen M, Little C, et al. Risk factors and outcomes of COVID-19 in New York City; a retrospective cohort study. J Med Virol. 2021;93(2):907-915. doi:10.1002/jmv.26337

28. Hussain Alsayed HA, Saheb Sharif-Askari F, Saheb Sharif-Askari N, Hussain AAS, Hamid Q, Halwani R. Early administration of remdesivir to COVID-19 patients associates with higher recovery rate and lower need for ICU admission: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0258643. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0258643

29. RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P, Lim WS, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):693-704. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2021436

30. Rees EM, Nightingale ES, Jafari Y, et al. COVID-19 length of hospital stay: a systematic review and data synthesis. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):270. doi:10.1186/s12916-020-01726-3

31. Anderson M, Bach P, Baldwin MR. Hospital length of stay for severe COVID-19: implications for Remdesivir’s value. medRxiv. 2020;2020.08.10.20171637. doi:10.1101/2020.08.10.20171637

1. Xie J, Covassin N, Fan Z, et al. Association between hypoxemia and mortality in patients with COVID-19. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(6):1138-1147. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.04.006

2. Asleh R, Asher E, Yagel O, et al. Predictors of hypoxemia and related adverse outcomes in patients hospitalized with COVID-19: a double-center retrospective study. J Clin Med. 2021;10(16):3581. doi:10.3390/jcm10163581

3. Choi KJ, Hong HL, Kim EJ. Association between oxygen saturation/fraction of inhaled oxygen and mortality in patients with COVID-19 associated pneumonia requiring oxygen therapy. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2021;84(2):125-133. doi:10.4046/trd.2020.0126

4. Dixit SB. Role of noninvasive oxygen therapy strategies in COVID-19 patients: Where are we going? Indian J Crit Care Med. 2020;24(10):897-898. doi:10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23625

5. Gonzalez-Castro A, Fajardo Campoverde A, Medina A, et al. Non-invasive mechanical ventilation and high-flow oxygen therapy in the COVID-19 pandemic: the value of a draw. Med Intensiva (Engl Ed). 2021;45(5):320-321. doi:10.1016/j.medine.2021.04.001

6. Pan W, Li J, Ou Y, et al. Clinical outcome of standardized oxygen therapy nursing strategy in COVID-19. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9(4):2171-2177. doi:10.21037/apm-20-1272

7. Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052-2059. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6775

8. He G, Han Y, Fang Q, et al. Clinical experience of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy in severe COVID-19 patients. Article in Chinese. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2020;49(2):232-239. doi:10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2020.03.13

9. Lalla U, Allwood BW, Louw EH, et al. The utility of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy in the management of respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 pneumonia. S Afr Med J. 2020;110(6):12941.

10. Zhang TT, Dai B, Wang W. Should the high-flow nasal oxygen therapy be used or avoided in COVID-19? J Transl Int Med. 2020;8(2):57-58. doi:10.2478/jtim-2020-0018

11. Agarwal A, Basmaji J, Muttalib F, et al. High-flow nasal cannula for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure in patients with COVID-19: systematic reviews of effectiveness and its risks of aerosolization, dispersion, and infection transmission. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67(9):1217-1248. doi:10.1007/s12630-020-01740-2

12. Geng S, Mei Q, Zhu C, et al. High flow nasal cannula is a good treatment option for COVID-19. Heart Lung. 2020;49(5):444-445. doi:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2020.03.018

13. Feinstein MM, Niforatos JD, Hyun I, et al. Considerations for ventilator triage during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(6):e53. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30192-2

14. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239-1242. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2648

15. Rojas-Marte G, Hashmi AT, Khalid M, et al. Outcomes in patients with COVID-19 disease and high oxygen requirements. J Clin Med Res. 2021;13(1):26-37. doi:10.14740/jocmr4405

16. Zhang R, Mylonakis E. In inpatients with COVID-19, none of remdesivir, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir, or interferon β-1a differed from standard care for in-hospital mortality. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(2):JC17. doi:10.7326/ACPJ202102160-017

17. Rello J, Waterer GW, Bourdiol A, Roquilly A. COVID-19, steroids and other immunomodulators: The jigsaw is not complete. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2020;39(6):699-701. doi:10.1016/j.accpm.2020.10.011

18. Dargin J, Stempek S, Lei Y, Gray Jr. A, Liesching T. The effect of a tiered provider staffing model on patient outcomes during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A single-center observational study. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2021;11(3). doi:10.4103/ijciis.ijciis_37_21

19. Ni YN, Wang T, Liang BM, Liang ZA. The independent factors associated with oxygen therapy in COVID-19 patients under 65 years old. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0245690. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0245690

20. Alhazzani W, Moller MH, Arabi YM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Crit Care Med. 2020;48(6):e440-e469. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000004363

21. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061-1069. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1585

22. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054-1062. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3

23. Argenziano MG, Bruce SL, Slater CL, et al. Characterization and clinical course of 1000 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York: retrospective case series. BMJ. 2020;369:m1996. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1996

24. Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1763-1770. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2

25. Demoule A, Vieillard Baron A, Darmon M, et al. High-flow nasal cannula in critically ill patients with severe COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(7):1039-1042. doi:10.1164/rccm.202005-2007LE

26. Hansen CK, Stempek S, Liesching T, Lei Y, Dargin J. Characteristics and outcomes of patients receiving high flow nasal cannula therapy prior to mechanical ventilation in COVID-19 respiratory failure: a prospective observational study. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2021;11(2):56-60. doi:10.4103/IJCIIS.IJCIIS_181_20

27. van Gerwen M, Alsen M, Little C, et al. Risk factors and outcomes of COVID-19 in New York City; a retrospective cohort study. J Med Virol. 2021;93(2):907-915. doi:10.1002/jmv.26337

28. Hussain Alsayed HA, Saheb Sharif-Askari F, Saheb Sharif-Askari N, Hussain AAS, Hamid Q, Halwani R. Early administration of remdesivir to COVID-19 patients associates with higher recovery rate and lower need for ICU admission: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0258643. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0258643

29. RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P, Lim WS, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):693-704. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2021436

30. Rees EM, Nightingale ES, Jafari Y, et al. COVID-19 length of hospital stay: a systematic review and data synthesis. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):270. doi:10.1186/s12916-020-01726-3

31. Anderson M, Bach P, Baldwin MR. Hospital length of stay for severe COVID-19: implications for Remdesivir’s value. medRxiv. 2020;2020.08.10.20171637. doi:10.1101/2020.08.10.20171637