User login

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome novel coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has presented a unique challenge to providing essential care to patients. Increased demand for health care workers and medical supplies, in addition to the risk for COVID-19 infection and asymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 among health care workers and patients, prompted the delay of nonessential services during the surge of cases this summer.1 Key considerations for continuing operation included current and projected COVID-19 cases in the region, ability to implement telehealth, staffing availability, personal protective equipment availability, and office capacity.2 Providing care that is deemed essential often was determined by the urgency of the treatment or service.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services outlined a strategy to stratify patients, based on level of acuity, during the COVID-19 surge3:

- Low-acuity treatments or services: includes routine primary, specialty, or preventive care visits. They should be postponed; telehealth follow-ups should be considered.

- Intermediate-acuity treatments or services: includes pediatric and neonatal care, follow-up visits for existing conditions, and evaluation of new symptoms (including those consistent with COVID-19). These services should initially be evaluated using telehealth, then triaged to the appropriate site and level of care.

- High-acuity treatments or services: address symptoms consistent with COVID-19 or other severe disease, of which the lack of in-person evaluation would result in harm to the patient.

Employees in hospitals and health care clinics were classified as essential, but dermatologists were not given explicit direction regarding clinic operation. Many practices have restricted services, especially those in an area of higher COVID-19 prevalence. However, the challenge of determining day-to-day operation may have been left to the provider in most cases.4 As many states in the United States continue to relax restrictions, total cases and the rate of positivity of COVID-19 have been sharply rising again, after months of decline,5 which suggests increased transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and potential resurgence of the high case burden on our health care system. Furthermore, a lack of a widely distributed vaccine or herd immunity suggests we will need to take many of the same precautions as in the first surge.6

In general, patients with cancer have been found to be at greater risk for adverse outcomes and mortality after COVID-19.7 Therefore, resource rationing is particularly concerning for patients with skin cancer, including melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, mycosis fungoides, and keratinocyte carcinoma. Triaging patients based on level of acuity, type of skin cancer, disease burden, host immunosuppression, and risk for progression must be carefully considered in this population.2 Treatment and follow-up present additional challenges.

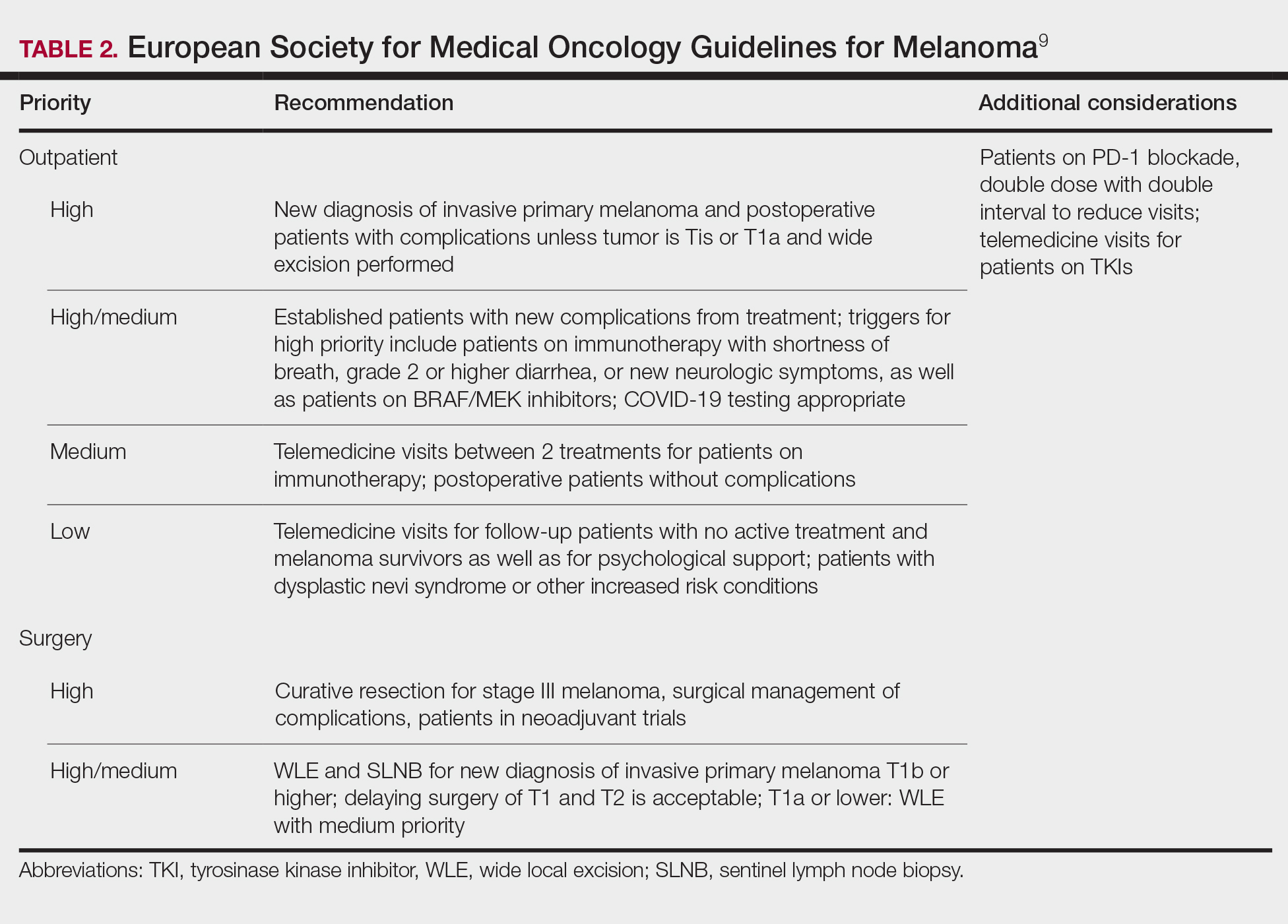

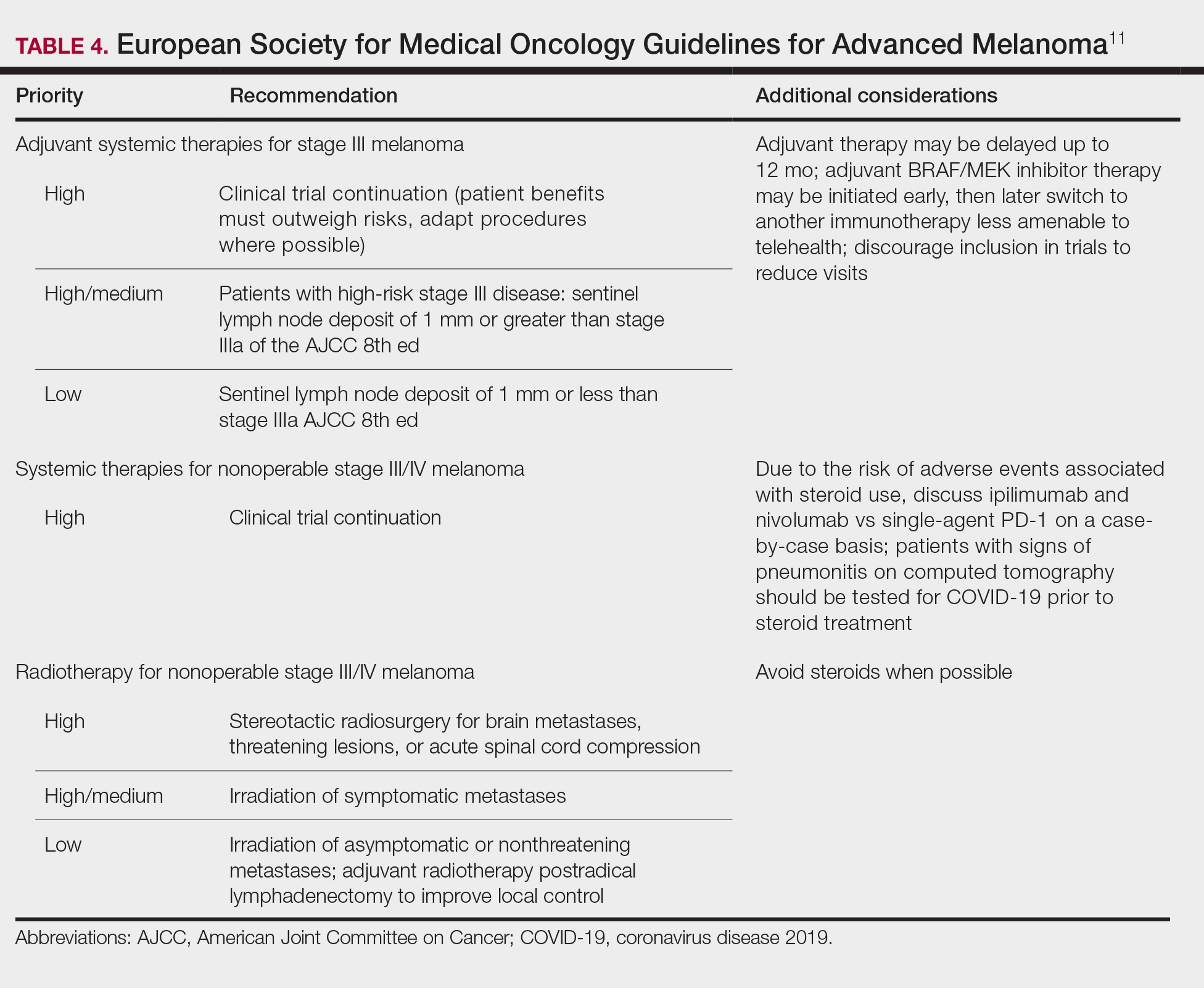

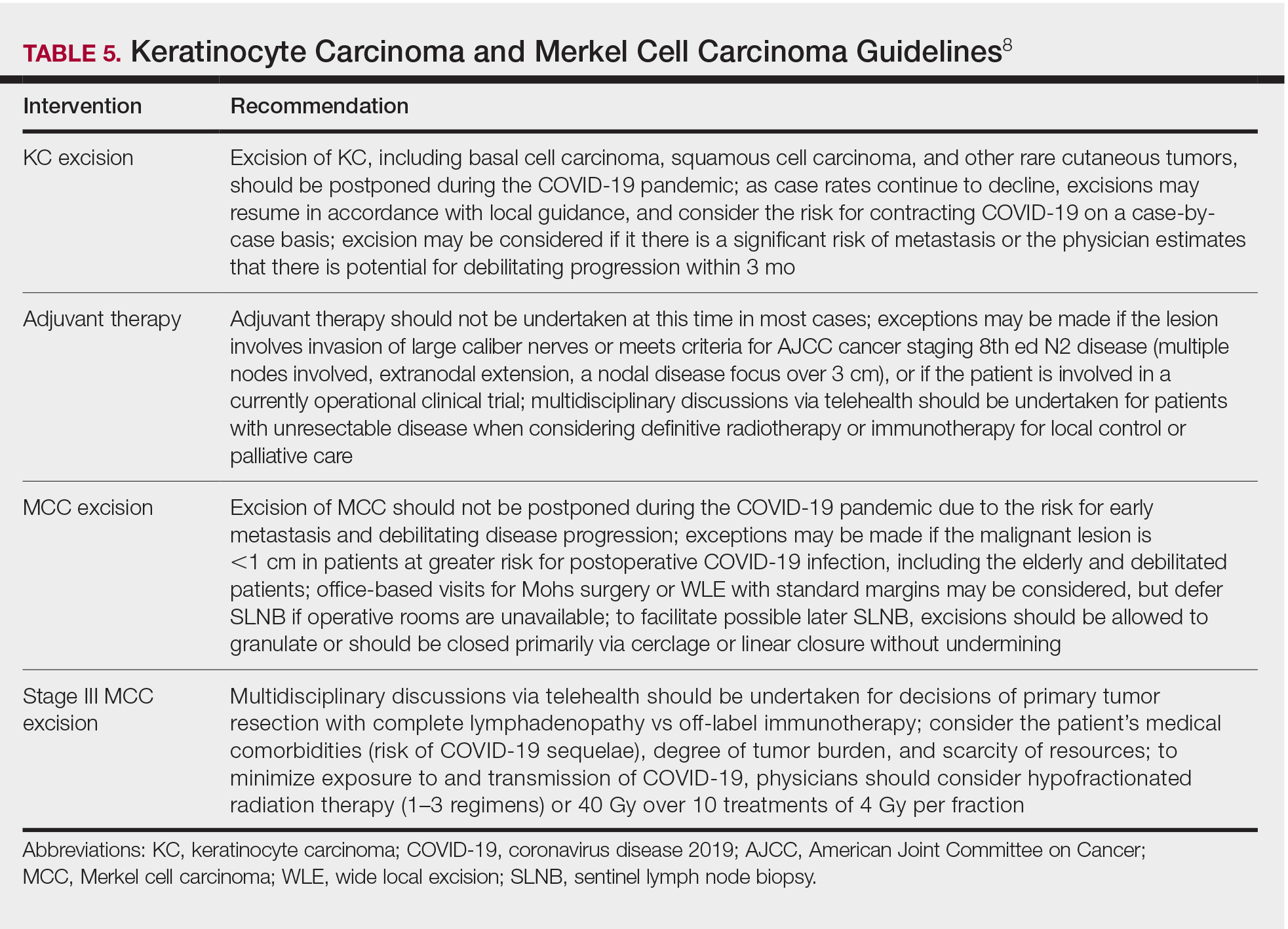

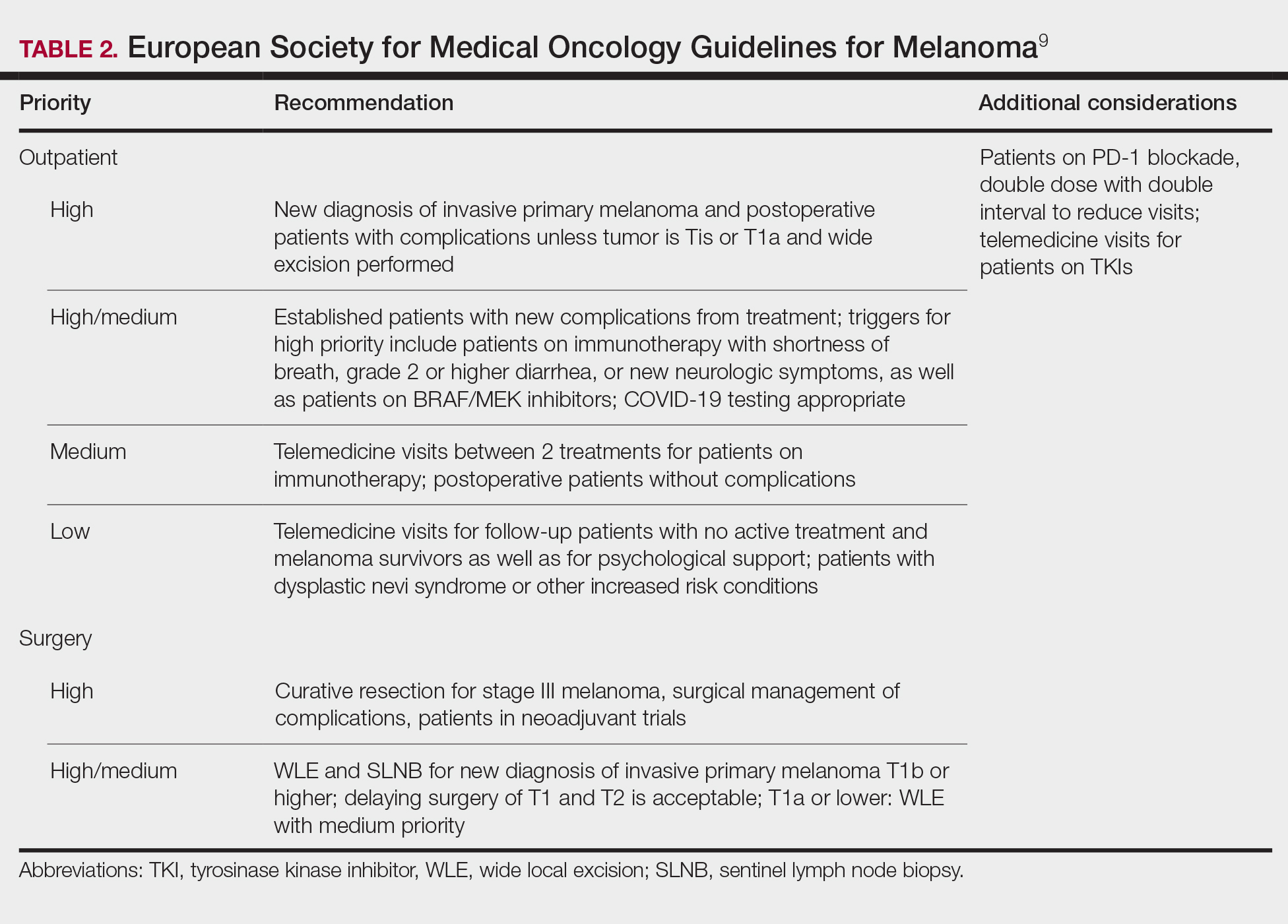

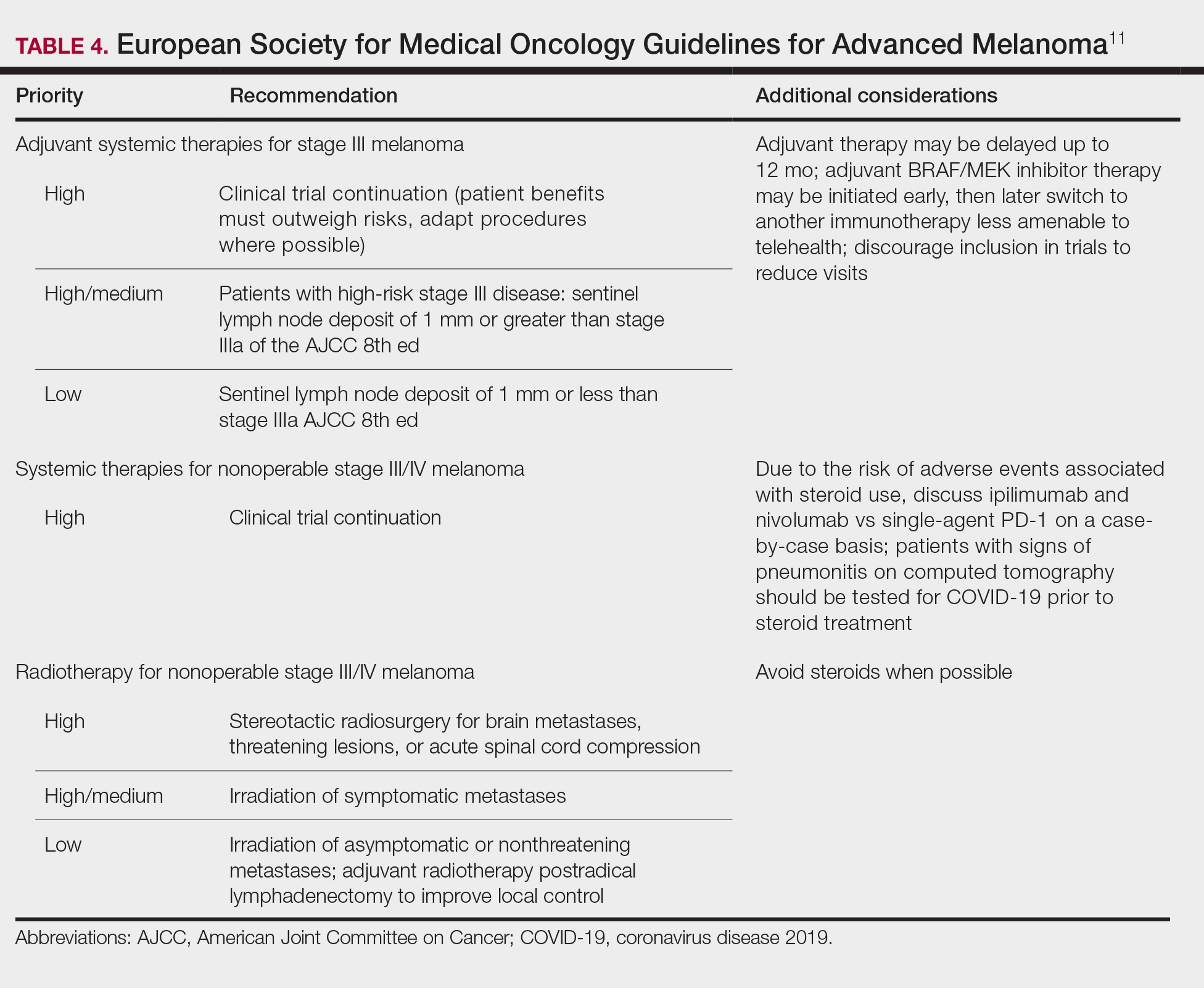

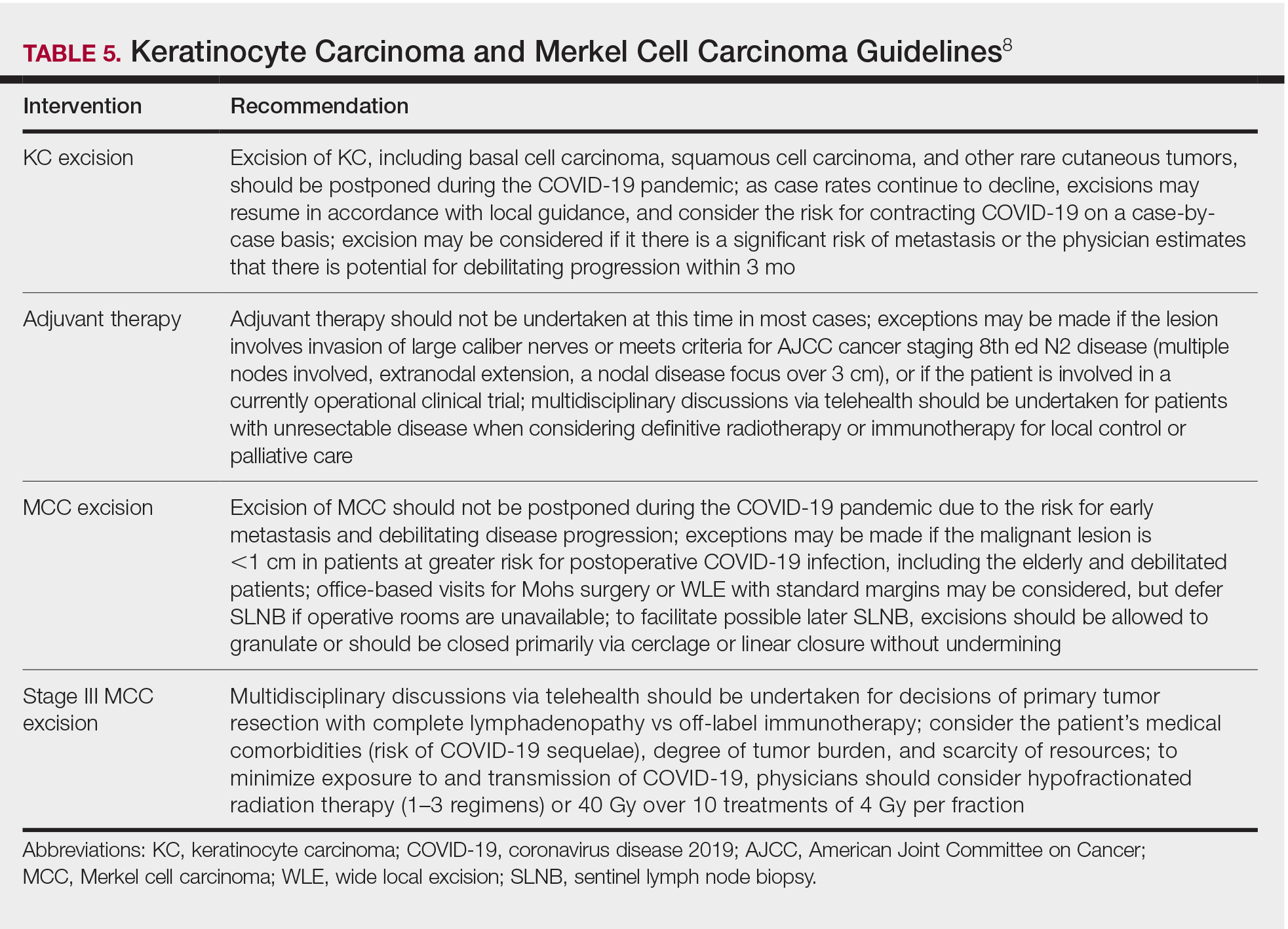

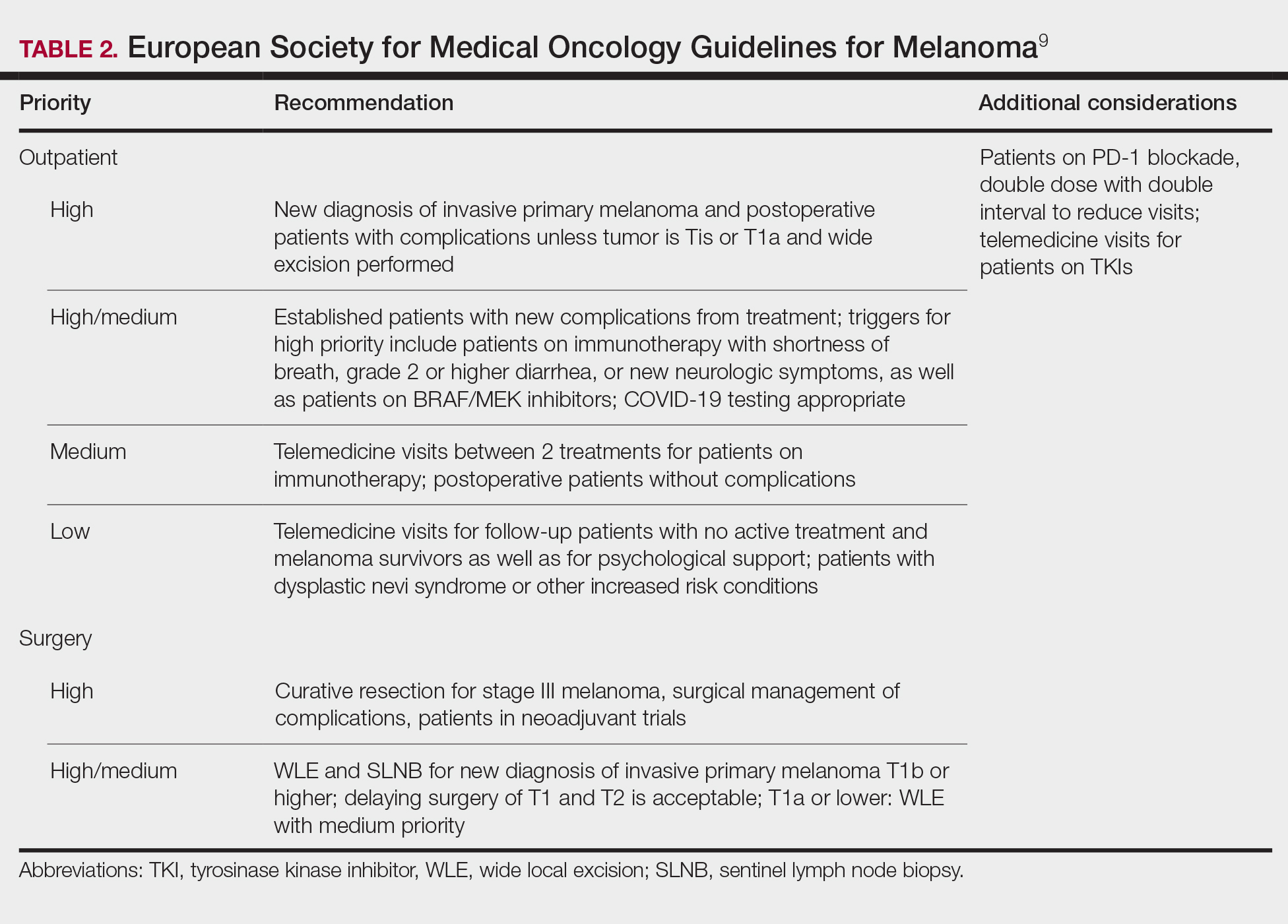

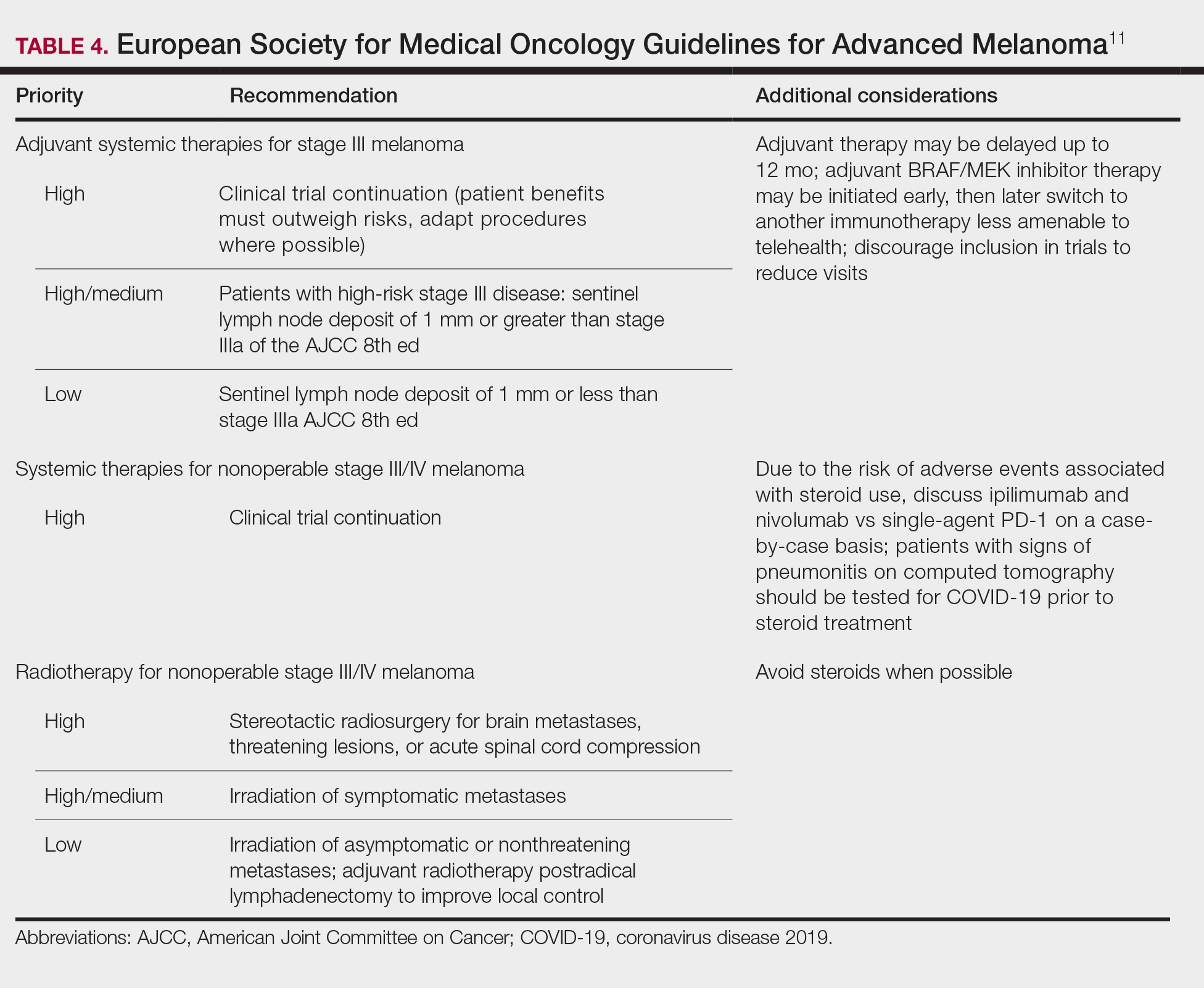

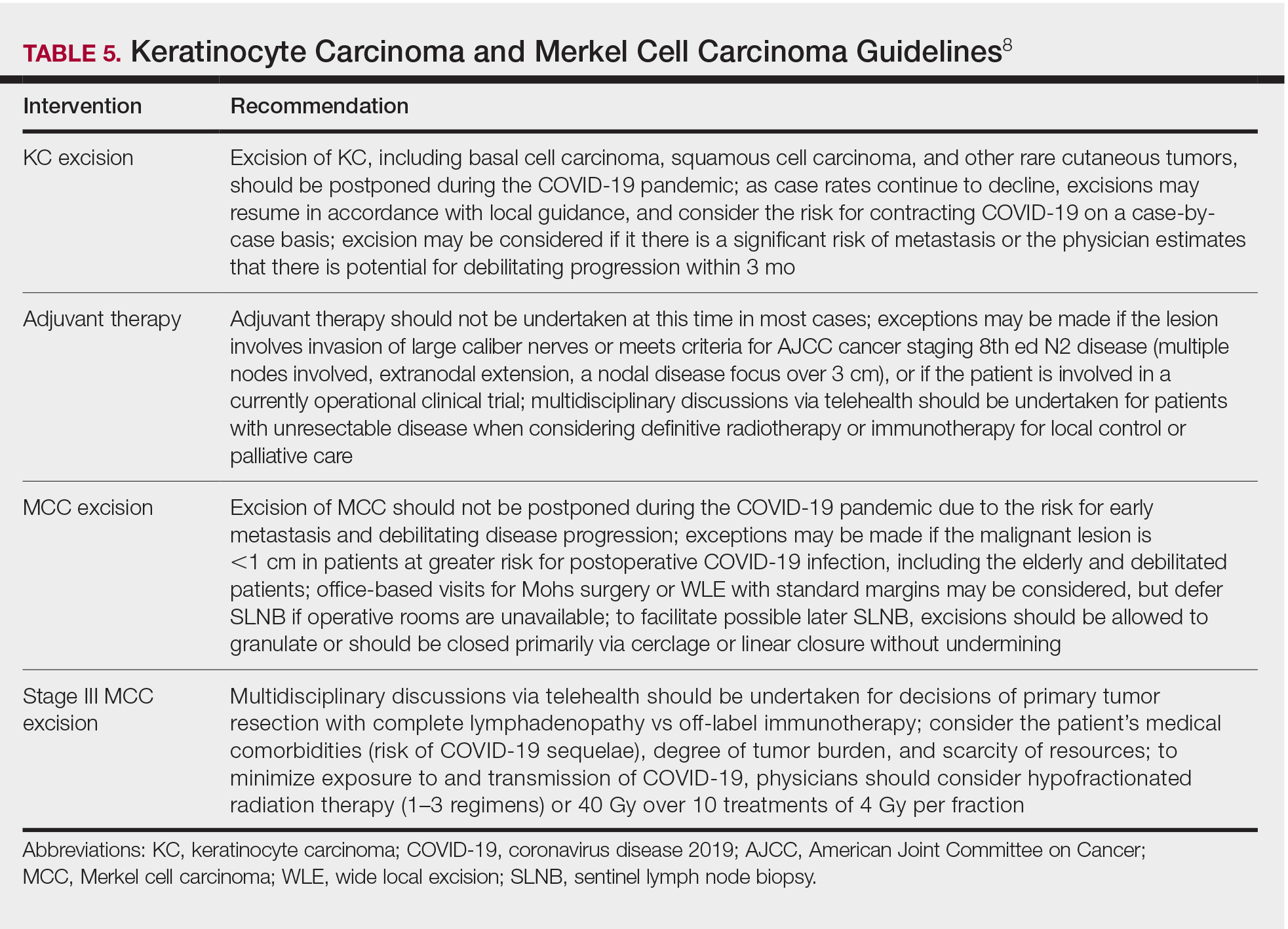

Guidelines provided by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) elaborated on key considerations for the treatment of melanoma, keratinocyte carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma during the COVID-19 pandemic.8-10 Guidelines from the NCCN concentrated on clear divisions between disease stages to determine provider response. Guidelines for melanoma patients proposed by the ESMO assign tiers by value-based priority in various treatment settings, which offered flexibility to providers as the COVID-19 landscape continued to change. Recommendations from the NCCN and ESMO are summarized in Tables 1 to 5.

Although these guidelines initially may have been proposed to delay treatment of lower-acuity tumors, such delay might not be feasible given the unknown duration of this pandemic and future disease waves. One review of several studies, which addressed the outcomes on melanoma survival following the surgical delay recommended by the NCCN, revealed contradictory evidence.12 Further, sufficiently powered studies will be needed to better understand the impact of delaying treatment during the summer COVID-19 surge on patients with skin cancer. Therefore, physicians must triage patients accordingly to manage and treat while also preventing disease spread.

Tips for Performing Dermatologic Surgery

Careful consideration should be made to protect both the patient and staff during office-based excisional surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. To minimize the risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2, patients and staff should (1) be screened for symptoms of COVID-19 at least 48 hours prior to entering the office via telephone screening questions, and (2) follow proper hygiene and contact procedures once entering the office. Consider obtaining a nasal polymerase chain reaction swab or saliva test 48 hours prior to the procedure if the patient is undergoing a head and neck procedure or there is risk for transmission.

Guidelines from the ESMO recommended that all patients undergoing surgery or therapy should be swabbed for SARS-CoV-2 before each treatment.11 Patients should wear a mask, remain 6-feet apart in the waiting room, and avoid touching objects until they enter the procedure room. Objects that the patient must touch, such as pens, should be cleaned immediately after such contact with either alcohol or soap and water for 20 seconds.

Office capacity should be reduced by allowing no more than 1 person to accompany the patient and ensuring the presence of only the minimum staff needed for the procedure. Staff who are deemed necessary should wear a mask continuously and gloves during patient contact.

Once in the procedure room, providers might be at elevated risk of contracting COVID-19 or transmitting SARS-CoV-2. A properly fitted N95 respirator and a face shield are recommended, especially for facial cases. N95 respirators can be reused by following the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations for reuse and decontamination techniques,13 which may include protecting the N95 respirator with a surgical mask and storing it in a paper bag when not in use. Consider testing asymptomatic patients in facial cases when they cannot wear a mask.

Steps should be taken to reduce in-person visits. Dissolving sutures can help avoid return visits. Follow-up visits and postprocedural questions should be managed by telehealth. However, patients with a high-risk underlying conditions (eg, posttransplantation, immunosuppressed) should continue to obtain regular skin checks because they are at higher risk for more aggressive malignancies, such as Merkel cell carcinoma.

Conclusion

The future trajectory of the COVID-19 pandemic is uncertain. Dermatologists should continue providing care for patients with skin cancer while mitigating the risk for COVID-19 infection and transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Guidelines provided by the NCCN and ESMO should help providers triage patients. Decisions should be made case by case, keeping in mind the availability of resources and practicing in compliance with local guidance.

- Moletta L, Pierobon ES, Capovilla G, et al. International guidelines and recommendations for surgery during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Int J Surg. 2020;79:180-188.

- Ueda M, Martins R, Hendrie PC, et al. Managing cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic: agility and collaboration toward common goal. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020:1-4.

- Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Non-emergent, elective medical services, and treatment recommendations. Published April 7, 2020. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/cms-non-emergent-elective-medical-recommendations.pdf

- Muddasani S, Housholder A, Fleischer AB. An assessment of United States dermatology practices during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:436-438.

- Coronavirus Resource Center, Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. Rate of positive tests in the US and states over time. Updated December 11, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/testing/individual-states

- Middleton J, Lopes H, Michelson K, et al. Planning for a second wave pandemic of COVID-19 and planning for winter: a statement from the Association of Schools of Public Health in the European Region. Int J Public Health. 2020;65:1525-1527.

- Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335-337.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Advisory statement for non-melanoma skin cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic (version 4). Published May 22, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://www.nccn.org/covid-19/pdf/NCCN-NMSC.pdf

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Short-term recommendations for cutaneous melanoma management during COVID-19 pandemic (version 3). Published May 6, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. www.nccn.org/covid-19/pdf/Melanoma.pdf - Conforti C, Giuffrida R, Di Meo N, et al. Management of advanced melanoma in the COVID-19 era. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13444.

- ESMO [European Society for Medical Oncology]. Cancer patient management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accessed Decemeber 11, 2020. https://www.esmo.org/guidelines/cancer-patient-management-during-the-covid-19-pandemic?hit=ehp

- Guhan S, Boland G, Tanabe K, et al. Surgical delay and mortality for primary cutaneous melanoma [published online July 22, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.078

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Implementing filtering facepiece respirator (FFR) reuse, including reuse after decontamination, when there are known shortages of N95 respirators. Updated October 19, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ppe-strategy/decontamination-reuse-respirators.html

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome novel coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has presented a unique challenge to providing essential care to patients. Increased demand for health care workers and medical supplies, in addition to the risk for COVID-19 infection and asymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 among health care workers and patients, prompted the delay of nonessential services during the surge of cases this summer.1 Key considerations for continuing operation included current and projected COVID-19 cases in the region, ability to implement telehealth, staffing availability, personal protective equipment availability, and office capacity.2 Providing care that is deemed essential often was determined by the urgency of the treatment or service.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services outlined a strategy to stratify patients, based on level of acuity, during the COVID-19 surge3:

- Low-acuity treatments or services: includes routine primary, specialty, or preventive care visits. They should be postponed; telehealth follow-ups should be considered.

- Intermediate-acuity treatments or services: includes pediatric and neonatal care, follow-up visits for existing conditions, and evaluation of new symptoms (including those consistent with COVID-19). These services should initially be evaluated using telehealth, then triaged to the appropriate site and level of care.

- High-acuity treatments or services: address symptoms consistent with COVID-19 or other severe disease, of which the lack of in-person evaluation would result in harm to the patient.

Employees in hospitals and health care clinics were classified as essential, but dermatologists were not given explicit direction regarding clinic operation. Many practices have restricted services, especially those in an area of higher COVID-19 prevalence. However, the challenge of determining day-to-day operation may have been left to the provider in most cases.4 As many states in the United States continue to relax restrictions, total cases and the rate of positivity of COVID-19 have been sharply rising again, after months of decline,5 which suggests increased transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and potential resurgence of the high case burden on our health care system. Furthermore, a lack of a widely distributed vaccine or herd immunity suggests we will need to take many of the same precautions as in the first surge.6

In general, patients with cancer have been found to be at greater risk for adverse outcomes and mortality after COVID-19.7 Therefore, resource rationing is particularly concerning for patients with skin cancer, including melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, mycosis fungoides, and keratinocyte carcinoma. Triaging patients based on level of acuity, type of skin cancer, disease burden, host immunosuppression, and risk for progression must be carefully considered in this population.2 Treatment and follow-up present additional challenges.

Guidelines provided by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) elaborated on key considerations for the treatment of melanoma, keratinocyte carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma during the COVID-19 pandemic.8-10 Guidelines from the NCCN concentrated on clear divisions between disease stages to determine provider response. Guidelines for melanoma patients proposed by the ESMO assign tiers by value-based priority in various treatment settings, which offered flexibility to providers as the COVID-19 landscape continued to change. Recommendations from the NCCN and ESMO are summarized in Tables 1 to 5.

Although these guidelines initially may have been proposed to delay treatment of lower-acuity tumors, such delay might not be feasible given the unknown duration of this pandemic and future disease waves. One review of several studies, which addressed the outcomes on melanoma survival following the surgical delay recommended by the NCCN, revealed contradictory evidence.12 Further, sufficiently powered studies will be needed to better understand the impact of delaying treatment during the summer COVID-19 surge on patients with skin cancer. Therefore, physicians must triage patients accordingly to manage and treat while also preventing disease spread.

Tips for Performing Dermatologic Surgery

Careful consideration should be made to protect both the patient and staff during office-based excisional surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. To minimize the risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2, patients and staff should (1) be screened for symptoms of COVID-19 at least 48 hours prior to entering the office via telephone screening questions, and (2) follow proper hygiene and contact procedures once entering the office. Consider obtaining a nasal polymerase chain reaction swab or saliva test 48 hours prior to the procedure if the patient is undergoing a head and neck procedure or there is risk for transmission.

Guidelines from the ESMO recommended that all patients undergoing surgery or therapy should be swabbed for SARS-CoV-2 before each treatment.11 Patients should wear a mask, remain 6-feet apart in the waiting room, and avoid touching objects until they enter the procedure room. Objects that the patient must touch, such as pens, should be cleaned immediately after such contact with either alcohol or soap and water for 20 seconds.

Office capacity should be reduced by allowing no more than 1 person to accompany the patient and ensuring the presence of only the minimum staff needed for the procedure. Staff who are deemed necessary should wear a mask continuously and gloves during patient contact.

Once in the procedure room, providers might be at elevated risk of contracting COVID-19 or transmitting SARS-CoV-2. A properly fitted N95 respirator and a face shield are recommended, especially for facial cases. N95 respirators can be reused by following the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations for reuse and decontamination techniques,13 which may include protecting the N95 respirator with a surgical mask and storing it in a paper bag when not in use. Consider testing asymptomatic patients in facial cases when they cannot wear a mask.

Steps should be taken to reduce in-person visits. Dissolving sutures can help avoid return visits. Follow-up visits and postprocedural questions should be managed by telehealth. However, patients with a high-risk underlying conditions (eg, posttransplantation, immunosuppressed) should continue to obtain regular skin checks because they are at higher risk for more aggressive malignancies, such as Merkel cell carcinoma.

Conclusion

The future trajectory of the COVID-19 pandemic is uncertain. Dermatologists should continue providing care for patients with skin cancer while mitigating the risk for COVID-19 infection and transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Guidelines provided by the NCCN and ESMO should help providers triage patients. Decisions should be made case by case, keeping in mind the availability of resources and practicing in compliance with local guidance.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome novel coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has presented a unique challenge to providing essential care to patients. Increased demand for health care workers and medical supplies, in addition to the risk for COVID-19 infection and asymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 among health care workers and patients, prompted the delay of nonessential services during the surge of cases this summer.1 Key considerations for continuing operation included current and projected COVID-19 cases in the region, ability to implement telehealth, staffing availability, personal protective equipment availability, and office capacity.2 Providing care that is deemed essential often was determined by the urgency of the treatment or service.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services outlined a strategy to stratify patients, based on level of acuity, during the COVID-19 surge3:

- Low-acuity treatments or services: includes routine primary, specialty, or preventive care visits. They should be postponed; telehealth follow-ups should be considered.

- Intermediate-acuity treatments or services: includes pediatric and neonatal care, follow-up visits for existing conditions, and evaluation of new symptoms (including those consistent with COVID-19). These services should initially be evaluated using telehealth, then triaged to the appropriate site and level of care.

- High-acuity treatments or services: address symptoms consistent with COVID-19 or other severe disease, of which the lack of in-person evaluation would result in harm to the patient.

Employees in hospitals and health care clinics were classified as essential, but dermatologists were not given explicit direction regarding clinic operation. Many practices have restricted services, especially those in an area of higher COVID-19 prevalence. However, the challenge of determining day-to-day operation may have been left to the provider in most cases.4 As many states in the United States continue to relax restrictions, total cases and the rate of positivity of COVID-19 have been sharply rising again, after months of decline,5 which suggests increased transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and potential resurgence of the high case burden on our health care system. Furthermore, a lack of a widely distributed vaccine or herd immunity suggests we will need to take many of the same precautions as in the first surge.6

In general, patients with cancer have been found to be at greater risk for adverse outcomes and mortality after COVID-19.7 Therefore, resource rationing is particularly concerning for patients with skin cancer, including melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, mycosis fungoides, and keratinocyte carcinoma. Triaging patients based on level of acuity, type of skin cancer, disease burden, host immunosuppression, and risk for progression must be carefully considered in this population.2 Treatment and follow-up present additional challenges.

Guidelines provided by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) elaborated on key considerations for the treatment of melanoma, keratinocyte carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma during the COVID-19 pandemic.8-10 Guidelines from the NCCN concentrated on clear divisions between disease stages to determine provider response. Guidelines for melanoma patients proposed by the ESMO assign tiers by value-based priority in various treatment settings, which offered flexibility to providers as the COVID-19 landscape continued to change. Recommendations from the NCCN and ESMO are summarized in Tables 1 to 5.

Although these guidelines initially may have been proposed to delay treatment of lower-acuity tumors, such delay might not be feasible given the unknown duration of this pandemic and future disease waves. One review of several studies, which addressed the outcomes on melanoma survival following the surgical delay recommended by the NCCN, revealed contradictory evidence.12 Further, sufficiently powered studies will be needed to better understand the impact of delaying treatment during the summer COVID-19 surge on patients with skin cancer. Therefore, physicians must triage patients accordingly to manage and treat while also preventing disease spread.

Tips for Performing Dermatologic Surgery

Careful consideration should be made to protect both the patient and staff during office-based excisional surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. To minimize the risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2, patients and staff should (1) be screened for symptoms of COVID-19 at least 48 hours prior to entering the office via telephone screening questions, and (2) follow proper hygiene and contact procedures once entering the office. Consider obtaining a nasal polymerase chain reaction swab or saliva test 48 hours prior to the procedure if the patient is undergoing a head and neck procedure or there is risk for transmission.

Guidelines from the ESMO recommended that all patients undergoing surgery or therapy should be swabbed for SARS-CoV-2 before each treatment.11 Patients should wear a mask, remain 6-feet apart in the waiting room, and avoid touching objects until they enter the procedure room. Objects that the patient must touch, such as pens, should be cleaned immediately after such contact with either alcohol or soap and water for 20 seconds.

Office capacity should be reduced by allowing no more than 1 person to accompany the patient and ensuring the presence of only the minimum staff needed for the procedure. Staff who are deemed necessary should wear a mask continuously and gloves during patient contact.

Once in the procedure room, providers might be at elevated risk of contracting COVID-19 or transmitting SARS-CoV-2. A properly fitted N95 respirator and a face shield are recommended, especially for facial cases. N95 respirators can be reused by following the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations for reuse and decontamination techniques,13 which may include protecting the N95 respirator with a surgical mask and storing it in a paper bag when not in use. Consider testing asymptomatic patients in facial cases when they cannot wear a mask.

Steps should be taken to reduce in-person visits. Dissolving sutures can help avoid return visits. Follow-up visits and postprocedural questions should be managed by telehealth. However, patients with a high-risk underlying conditions (eg, posttransplantation, immunosuppressed) should continue to obtain regular skin checks because they are at higher risk for more aggressive malignancies, such as Merkel cell carcinoma.

Conclusion

The future trajectory of the COVID-19 pandemic is uncertain. Dermatologists should continue providing care for patients with skin cancer while mitigating the risk for COVID-19 infection and transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Guidelines provided by the NCCN and ESMO should help providers triage patients. Decisions should be made case by case, keeping in mind the availability of resources and practicing in compliance with local guidance.

- Moletta L, Pierobon ES, Capovilla G, et al. International guidelines and recommendations for surgery during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Int J Surg. 2020;79:180-188.

- Ueda M, Martins R, Hendrie PC, et al. Managing cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic: agility and collaboration toward common goal. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020:1-4.

- Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Non-emergent, elective medical services, and treatment recommendations. Published April 7, 2020. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/cms-non-emergent-elective-medical-recommendations.pdf

- Muddasani S, Housholder A, Fleischer AB. An assessment of United States dermatology practices during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:436-438.

- Coronavirus Resource Center, Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. Rate of positive tests in the US and states over time. Updated December 11, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/testing/individual-states

- Middleton J, Lopes H, Michelson K, et al. Planning for a second wave pandemic of COVID-19 and planning for winter: a statement from the Association of Schools of Public Health in the European Region. Int J Public Health. 2020;65:1525-1527.

- Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335-337.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Advisory statement for non-melanoma skin cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic (version 4). Published May 22, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://www.nccn.org/covid-19/pdf/NCCN-NMSC.pdf

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Short-term recommendations for cutaneous melanoma management during COVID-19 pandemic (version 3). Published May 6, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. www.nccn.org/covid-19/pdf/Melanoma.pdf - Conforti C, Giuffrida R, Di Meo N, et al. Management of advanced melanoma in the COVID-19 era. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13444.

- ESMO [European Society for Medical Oncology]. Cancer patient management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accessed Decemeber 11, 2020. https://www.esmo.org/guidelines/cancer-patient-management-during-the-covid-19-pandemic?hit=ehp

- Guhan S, Boland G, Tanabe K, et al. Surgical delay and mortality for primary cutaneous melanoma [published online July 22, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.078

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Implementing filtering facepiece respirator (FFR) reuse, including reuse after decontamination, when there are known shortages of N95 respirators. Updated October 19, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ppe-strategy/decontamination-reuse-respirators.html

- Moletta L, Pierobon ES, Capovilla G, et al. International guidelines and recommendations for surgery during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Int J Surg. 2020;79:180-188.

- Ueda M, Martins R, Hendrie PC, et al. Managing cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic: agility and collaboration toward common goal. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020:1-4.

- Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Non-emergent, elective medical services, and treatment recommendations. Published April 7, 2020. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/cms-non-emergent-elective-medical-recommendations.pdf

- Muddasani S, Housholder A, Fleischer AB. An assessment of United States dermatology practices during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:436-438.

- Coronavirus Resource Center, Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. Rate of positive tests in the US and states over time. Updated December 11, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/testing/individual-states

- Middleton J, Lopes H, Michelson K, et al. Planning for a second wave pandemic of COVID-19 and planning for winter: a statement from the Association of Schools of Public Health in the European Region. Int J Public Health. 2020;65:1525-1527.

- Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335-337.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Advisory statement for non-melanoma skin cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic (version 4). Published May 22, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://www.nccn.org/covid-19/pdf/NCCN-NMSC.pdf

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Short-term recommendations for cutaneous melanoma management during COVID-19 pandemic (version 3). Published May 6, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. www.nccn.org/covid-19/pdf/Melanoma.pdf - Conforti C, Giuffrida R, Di Meo N, et al. Management of advanced melanoma in the COVID-19 era. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13444.

- ESMO [European Society for Medical Oncology]. Cancer patient management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accessed Decemeber 11, 2020. https://www.esmo.org/guidelines/cancer-patient-management-during-the-covid-19-pandemic?hit=ehp

- Guhan S, Boland G, Tanabe K, et al. Surgical delay and mortality for primary cutaneous melanoma [published online July 22, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.078

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Implementing filtering facepiece respirator (FFR) reuse, including reuse after decontamination, when there are known shortages of N95 respirators. Updated October 19, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ppe-strategy/decontamination-reuse-respirators.html

Practice Points

- Consider the rate of cases and transmission in your area during a pandemic surge when triaging surgical and nonsurgical cases.

- If performing head and neck surgical procedures or cosmetic procedures in which the patient cannot wear a mask, consider testing them 24 to 48 hours before the procedure.

- Follow Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines concerning screening asymptomatic patients. Also, follow CDC guidelines on testing patients who have had prior infections.

- Ensure proper personal protective equipment for yourself and staff, including the use of properly fitting N95 respirators and face shields.