User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Take steps to relieve ataxia in patients with alcohol use disorder

Ataxia is a well-known complication of chronic alcohol abuse, which is attributed to degeneration of the cerebellar vermis. However, effective treatment approaches, as well as the timing and level of recovery, remain unclear. One cross-sectional study found that long-term abstainers from alcohol had less severe ataxia than short-term abstainers,1 suggesting that improvement is possible with continued sobriety. However, a recent longitudinal study contradicts this finding, reporting no improvement in ataxia in patients abstinent for 10 weeks to 1 year.2

CASE REPORT

Unable to walk, heavy alcohol use

Mr. G, a 59-year-old white male with a history of daily, heavy alcohol use, presents to the emergency room reporting that he has “not been able to walk right” for 3 weeks. He is in a wheelchair because of ataxia and difficulty balancing. He denies headaches, visual changes, weakness, numbness, and difficulty speaking or swallowing.

Mr. G reports drinking one 40-oz bottle of malt liquor and 2 pints of vodka per day for more than 40 years. His alcohol abuse led to homelessness, unemployment, and divorce. Despite heavy drinking, he denies signs of withdrawal, including shaking, sweating, seizures, and delirium.

Mr. G has no other medical conditions. He denies a family history of neurologic disorders or substance abuse.

His pulse is 100 beats per minute, respirations of 16 breaths per minute, temperature of 37°C, and blood pressure of 143/89 mm Hg. Physical examination reveals a wide-based gait.

Mr. G is admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit to monitor and treat his alcohol withdrawal and to undergo further workup of the gait disturbance.

A head CT scan shows non-specific changes; an EEG also is within normal limits. Complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, liver function test, HIV test, acute hepatitis panel, thyroid function test, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and vitamin B12 tests are within normal ranges.

A full neurologic exam reveals a wide-based gait, impaired heel-shin test, and dysmetria on finger-nose-finger test. Mr. G is given a diagnosis of ataxia due to alcoholic cerebellar degeneration. Thiamine repletion is suggested.

Treatment and outcome

Mr. G continues on thiamine, 100 mg, twice daily, and oxazepam, 15 mg, as needed, to manage withdrawal symptoms. He receives gait training 3 times per week.

Approximately 10 days after admission, Mr. G is able to ambulate with a walker. Three weeks after admission, his gait has improved and he walks with a cane. (See the video at CurrentPsychiatry.com for an illustration of this progressive recovery.)

After discharge, Mr. G is referred to an addiction psychiatrist and addiction psychotherapist for ongoing treatment of alcohol use disorder.

Making the diagnosis

In a patient complaining of balance difficulties, consider ataxia secondary to cerebellar degeneration.

- Take a complete history. Ask about the onset and progression of ataxia.

- Obtain a family history. Some types of ataxia are genetic.

- Perform a neurologic examination, which may reveal signs of cerebellar deficits, particularly characteristic wide-based gait. These patients will have difficulty when walking in tandem. Other impairments on the neurologic exam that may raise suspicion for a cerebellar disorder include: impaired heel-shin test, impaired finger-nose-finger test (dysmetria), impaired rapid alternating movements (dysdiadochokinesia), nystagmus, impaired smooth pursuits, intention tremor, or speech abnormalities.

- Perform head imaging, such as a CT scan or MRI. In patients with ataxia secondary to alcohol abuse, imaging might reveal degeneration of the cerebellar vermis.

- Perform laboratory tests, such as inflammatory markers, vitamin levels, and thyroid function testing to detect possible toxic-metabolic or inflammatory causes.

Alcohol-induced ataxia can be diagnosed in patients with a history of heavy drinking if the workup does not reveal another possible cause for the gait disturbance. Other less common deficits associated with alcohol-induced cerebellar injury include:

- dysarthria

- abnormal rate and force of movement

- limb ataxia.3

Recommendations

- Be able to recognize the characteristic gait of patients with alcohol-induced ataxia.

- Provide thiamine supplementation.

- Refer patients to physical therapy.

- Educate your patients that their gait will not improve and may worsen if they continue to drink.

- Refer patients for ongoing treatment for alcohol use disorder, including medication management and psychotherapy.

Our experience suggests that patients with alcohol use disorder with cerebellar ataxia could have a good prognosis for ambulation. Improvement could occur over several weeks; it is unclear whether further gains can be expected with months or years of abstinence.

1. Smith S, Fein G. Persistent but less severe ataxia in long-term versus short-term abstinent alcoholic men and women: a cross-sectional analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35(12):2184-2192.

2. Fein G, Greenstein D. Gait and balance deficits in chronic alcoholics: no improvement from 10 weeks through 1 year abstinence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37(1):86-95.

3. Fitzpatrick LE, Jackson M, Crowe SF. Characterization of cerebellar ataxia in chronic alcoholics using the International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale (ICARS). Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36(11):1942-1951.

Ataxia is a well-known complication of chronic alcohol abuse, which is attributed to degeneration of the cerebellar vermis. However, effective treatment approaches, as well as the timing and level of recovery, remain unclear. One cross-sectional study found that long-term abstainers from alcohol had less severe ataxia than short-term abstainers,1 suggesting that improvement is possible with continued sobriety. However, a recent longitudinal study contradicts this finding, reporting no improvement in ataxia in patients abstinent for 10 weeks to 1 year.2

CASE REPORT

Unable to walk, heavy alcohol use

Mr. G, a 59-year-old white male with a history of daily, heavy alcohol use, presents to the emergency room reporting that he has “not been able to walk right” for 3 weeks. He is in a wheelchair because of ataxia and difficulty balancing. He denies headaches, visual changes, weakness, numbness, and difficulty speaking or swallowing.

Mr. G reports drinking one 40-oz bottle of malt liquor and 2 pints of vodka per day for more than 40 years. His alcohol abuse led to homelessness, unemployment, and divorce. Despite heavy drinking, he denies signs of withdrawal, including shaking, sweating, seizures, and delirium.

Mr. G has no other medical conditions. He denies a family history of neurologic disorders or substance abuse.

His pulse is 100 beats per minute, respirations of 16 breaths per minute, temperature of 37°C, and blood pressure of 143/89 mm Hg. Physical examination reveals a wide-based gait.

Mr. G is admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit to monitor and treat his alcohol withdrawal and to undergo further workup of the gait disturbance.

A head CT scan shows non-specific changes; an EEG also is within normal limits. Complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, liver function test, HIV test, acute hepatitis panel, thyroid function test, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and vitamin B12 tests are within normal ranges.

A full neurologic exam reveals a wide-based gait, impaired heel-shin test, and dysmetria on finger-nose-finger test. Mr. G is given a diagnosis of ataxia due to alcoholic cerebellar degeneration. Thiamine repletion is suggested.

Treatment and outcome

Mr. G continues on thiamine, 100 mg, twice daily, and oxazepam, 15 mg, as needed, to manage withdrawal symptoms. He receives gait training 3 times per week.

Approximately 10 days after admission, Mr. G is able to ambulate with a walker. Three weeks after admission, his gait has improved and he walks with a cane. (See the video at CurrentPsychiatry.com for an illustration of this progressive recovery.)

After discharge, Mr. G is referred to an addiction psychiatrist and addiction psychotherapist for ongoing treatment of alcohol use disorder.

Making the diagnosis

In a patient complaining of balance difficulties, consider ataxia secondary to cerebellar degeneration.

- Take a complete history. Ask about the onset and progression of ataxia.

- Obtain a family history. Some types of ataxia are genetic.

- Perform a neurologic examination, which may reveal signs of cerebellar deficits, particularly characteristic wide-based gait. These patients will have difficulty when walking in tandem. Other impairments on the neurologic exam that may raise suspicion for a cerebellar disorder include: impaired heel-shin test, impaired finger-nose-finger test (dysmetria), impaired rapid alternating movements (dysdiadochokinesia), nystagmus, impaired smooth pursuits, intention tremor, or speech abnormalities.

- Perform head imaging, such as a CT scan or MRI. In patients with ataxia secondary to alcohol abuse, imaging might reveal degeneration of the cerebellar vermis.

- Perform laboratory tests, such as inflammatory markers, vitamin levels, and thyroid function testing to detect possible toxic-metabolic or inflammatory causes.

Alcohol-induced ataxia can be diagnosed in patients with a history of heavy drinking if the workup does not reveal another possible cause for the gait disturbance. Other less common deficits associated with alcohol-induced cerebellar injury include:

- dysarthria

- abnormal rate and force of movement

- limb ataxia.3

Recommendations

- Be able to recognize the characteristic gait of patients with alcohol-induced ataxia.

- Provide thiamine supplementation.

- Refer patients to physical therapy.

- Educate your patients that their gait will not improve and may worsen if they continue to drink.

- Refer patients for ongoing treatment for alcohol use disorder, including medication management and psychotherapy.

Our experience suggests that patients with alcohol use disorder with cerebellar ataxia could have a good prognosis for ambulation. Improvement could occur over several weeks; it is unclear whether further gains can be expected with months or years of abstinence.

Ataxia is a well-known complication of chronic alcohol abuse, which is attributed to degeneration of the cerebellar vermis. However, effective treatment approaches, as well as the timing and level of recovery, remain unclear. One cross-sectional study found that long-term abstainers from alcohol had less severe ataxia than short-term abstainers,1 suggesting that improvement is possible with continued sobriety. However, a recent longitudinal study contradicts this finding, reporting no improvement in ataxia in patients abstinent for 10 weeks to 1 year.2

CASE REPORT

Unable to walk, heavy alcohol use

Mr. G, a 59-year-old white male with a history of daily, heavy alcohol use, presents to the emergency room reporting that he has “not been able to walk right” for 3 weeks. He is in a wheelchair because of ataxia and difficulty balancing. He denies headaches, visual changes, weakness, numbness, and difficulty speaking or swallowing.

Mr. G reports drinking one 40-oz bottle of malt liquor and 2 pints of vodka per day for more than 40 years. His alcohol abuse led to homelessness, unemployment, and divorce. Despite heavy drinking, he denies signs of withdrawal, including shaking, sweating, seizures, and delirium.

Mr. G has no other medical conditions. He denies a family history of neurologic disorders or substance abuse.

His pulse is 100 beats per minute, respirations of 16 breaths per minute, temperature of 37°C, and blood pressure of 143/89 mm Hg. Physical examination reveals a wide-based gait.

Mr. G is admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit to monitor and treat his alcohol withdrawal and to undergo further workup of the gait disturbance.

A head CT scan shows non-specific changes; an EEG also is within normal limits. Complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, liver function test, HIV test, acute hepatitis panel, thyroid function test, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and vitamin B12 tests are within normal ranges.

A full neurologic exam reveals a wide-based gait, impaired heel-shin test, and dysmetria on finger-nose-finger test. Mr. G is given a diagnosis of ataxia due to alcoholic cerebellar degeneration. Thiamine repletion is suggested.

Treatment and outcome

Mr. G continues on thiamine, 100 mg, twice daily, and oxazepam, 15 mg, as needed, to manage withdrawal symptoms. He receives gait training 3 times per week.

Approximately 10 days after admission, Mr. G is able to ambulate with a walker. Three weeks after admission, his gait has improved and he walks with a cane. (See the video at CurrentPsychiatry.com for an illustration of this progressive recovery.)

After discharge, Mr. G is referred to an addiction psychiatrist and addiction psychotherapist for ongoing treatment of alcohol use disorder.

Making the diagnosis

In a patient complaining of balance difficulties, consider ataxia secondary to cerebellar degeneration.

- Take a complete history. Ask about the onset and progression of ataxia.

- Obtain a family history. Some types of ataxia are genetic.

- Perform a neurologic examination, which may reveal signs of cerebellar deficits, particularly characteristic wide-based gait. These patients will have difficulty when walking in tandem. Other impairments on the neurologic exam that may raise suspicion for a cerebellar disorder include: impaired heel-shin test, impaired finger-nose-finger test (dysmetria), impaired rapid alternating movements (dysdiadochokinesia), nystagmus, impaired smooth pursuits, intention tremor, or speech abnormalities.

- Perform head imaging, such as a CT scan or MRI. In patients with ataxia secondary to alcohol abuse, imaging might reveal degeneration of the cerebellar vermis.

- Perform laboratory tests, such as inflammatory markers, vitamin levels, and thyroid function testing to detect possible toxic-metabolic or inflammatory causes.

Alcohol-induced ataxia can be diagnosed in patients with a history of heavy drinking if the workup does not reveal another possible cause for the gait disturbance. Other less common deficits associated with alcohol-induced cerebellar injury include:

- dysarthria

- abnormal rate and force of movement

- limb ataxia.3

Recommendations

- Be able to recognize the characteristic gait of patients with alcohol-induced ataxia.

- Provide thiamine supplementation.

- Refer patients to physical therapy.

- Educate your patients that their gait will not improve and may worsen if they continue to drink.

- Refer patients for ongoing treatment for alcohol use disorder, including medication management and psychotherapy.

Our experience suggests that patients with alcohol use disorder with cerebellar ataxia could have a good prognosis for ambulation. Improvement could occur over several weeks; it is unclear whether further gains can be expected with months or years of abstinence.

1. Smith S, Fein G. Persistent but less severe ataxia in long-term versus short-term abstinent alcoholic men and women: a cross-sectional analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35(12):2184-2192.

2. Fein G, Greenstein D. Gait and balance deficits in chronic alcoholics: no improvement from 10 weeks through 1 year abstinence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37(1):86-95.

3. Fitzpatrick LE, Jackson M, Crowe SF. Characterization of cerebellar ataxia in chronic alcoholics using the International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale (ICARS). Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36(11):1942-1951.

1. Smith S, Fein G. Persistent but less severe ataxia in long-term versus short-term abstinent alcoholic men and women: a cross-sectional analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35(12):2184-2192.

2. Fein G, Greenstein D. Gait and balance deficits in chronic alcoholics: no improvement from 10 weeks through 1 year abstinence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37(1):86-95.

3. Fitzpatrick LE, Jackson M, Crowe SF. Characterization of cerebellar ataxia in chronic alcoholics using the International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale (ICARS). Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36(11):1942-1951.

No more 'stickies'!: Help your patients bring their ‘to-do’ list into the 21st century

Difficulty with time management and organization is one of the most common complaints of patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Being unproductive and inefficient also is anxiety-producing and depressing, leaving patients with additional comorbidity.

Although medication can help improve a person’s focus, if the patient is focusing on a set of poorly designed systems, he (she) will see little improvement. A comprehensive approach to improving day-to-day task management, similar to the one I describe here and use with my patients, is therefore as important as medication.

Needed: An ‘organizing principle’

Imagine that supermarkets displayed food in the order it arrives from the food distributors and producers. You’d walk in to the store and see a display of food that lacks hierarchy—1 random item placed next to another. The experience would be jarring, and shopping would be a much slower chore. Furthermore, what if you had to go to 5 stores to cover all your needs?

Yet, that is how most “to-do” lists are executed: A thought comes in, a thought goes down on paper. Or on a sticky note. Or in an app. Or in a calendar. Or all of the above! Often, there is neither an organizing principle (other than perhaps chronological order) or a central repository. No wonder it’s hard to feel present and clear-minded. Add to this disorganization the volume of information coming in from the environment—e-mails, voice mails, texts, notifications, dings, beeps, buzzes, and maybe even snail mail—and the feeling of being overwhelmed grows.

Unconscious motives for maintaining poor systems also might play a role. People with a “need to please” personality type or who are more passive-aggressive in their communication are more likely to overcommit, and then forget or be late completing their tasks, rather than saying “No” from the outset or delegating the work.

Survival basics for time management

Assuming there is simply a skills deficit, you can teach basic time and project management skills to patients with ADHD (and to any patient with suboptimal executive functioning). Here are basic principles to adopt:

- If you can forget it, you will, so all tasks should go onto the to-do list.

- You should keep only 1 list. Adding on “stickies” is not allowed.

- Your list is like an extra lobe of your brain: It should be present at all times, whether you keep it in “the Cloud,” on your desktop, or on paper.

- Review your list and clean it up at least daily. This takes time, but it also saves time—in spades—when you can call upon the right task, at the right time, with energy and drive.

- The first action you should take in the daily review is to weed out or delegate tasks.

- Next, categorize remaining tasks. (Note: The free smartphone app Evernote allows you to do this with “tags.”) Categorizing allows you to process sets of tasks in buckets that can be tackled as a bundle and, therefore, more efficiently. For example, having all of your errands, items to research, and telephone calls that need to be returned in separate buckets allows for speedier processing—as opposed to veering back and forth between line items.

- Then, move remaining high-priority items to the top of the list. However, remember that, if everything is urgent, nothing is. Items that are low-hanging fruit that you can cross off the list in a matter of minutes can be prioritized even if they are not as urgent. By doing that, your list becomes more manageable and your brain can dive deeper into more complex tasks.

- Block out calendar time for each of your buckets with this formula: (1) Estimate how much time you’ll need to complete the tasks in each bucket, then add 50% for each bucket. (2) Add in commuting, set-up, or wind-down time, if you need it, to the grand total for all buckets, and then add 50% more than you’ve estimated

Set the brain free!

This process will seem like a burden at the beginning, when the synapses underneath it still need to get stronger (much like how the body responds to exercise). However, as long as these principles are put into action daily, they will become a trusted, second-nature system that frees the brain from distraction and anxiety—and, ultimately,

Difficulty with time management and organization is one of the most common complaints of patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Being unproductive and inefficient also is anxiety-producing and depressing, leaving patients with additional comorbidity.

Although medication can help improve a person’s focus, if the patient is focusing on a set of poorly designed systems, he (she) will see little improvement. A comprehensive approach to improving day-to-day task management, similar to the one I describe here and use with my patients, is therefore as important as medication.

Needed: An ‘organizing principle’

Imagine that supermarkets displayed food in the order it arrives from the food distributors and producers. You’d walk in to the store and see a display of food that lacks hierarchy—1 random item placed next to another. The experience would be jarring, and shopping would be a much slower chore. Furthermore, what if you had to go to 5 stores to cover all your needs?

Yet, that is how most “to-do” lists are executed: A thought comes in, a thought goes down on paper. Or on a sticky note. Or in an app. Or in a calendar. Or all of the above! Often, there is neither an organizing principle (other than perhaps chronological order) or a central repository. No wonder it’s hard to feel present and clear-minded. Add to this disorganization the volume of information coming in from the environment—e-mails, voice mails, texts, notifications, dings, beeps, buzzes, and maybe even snail mail—and the feeling of being overwhelmed grows.

Unconscious motives for maintaining poor systems also might play a role. People with a “need to please” personality type or who are more passive-aggressive in their communication are more likely to overcommit, and then forget or be late completing their tasks, rather than saying “No” from the outset or delegating the work.

Survival basics for time management

Assuming there is simply a skills deficit, you can teach basic time and project management skills to patients with ADHD (and to any patient with suboptimal executive functioning). Here are basic principles to adopt:

- If you can forget it, you will, so all tasks should go onto the to-do list.

- You should keep only 1 list. Adding on “stickies” is not allowed.

- Your list is like an extra lobe of your brain: It should be present at all times, whether you keep it in “the Cloud,” on your desktop, or on paper.

- Review your list and clean it up at least daily. This takes time, but it also saves time—in spades—when you can call upon the right task, at the right time, with energy and drive.

- The first action you should take in the daily review is to weed out or delegate tasks.

- Next, categorize remaining tasks. (Note: The free smartphone app Evernote allows you to do this with “tags.”) Categorizing allows you to process sets of tasks in buckets that can be tackled as a bundle and, therefore, more efficiently. For example, having all of your errands, items to research, and telephone calls that need to be returned in separate buckets allows for speedier processing—as opposed to veering back and forth between line items.

- Then, move remaining high-priority items to the top of the list. However, remember that, if everything is urgent, nothing is. Items that are low-hanging fruit that you can cross off the list in a matter of minutes can be prioritized even if they are not as urgent. By doing that, your list becomes more manageable and your brain can dive deeper into more complex tasks.

- Block out calendar time for each of your buckets with this formula: (1) Estimate how much time you’ll need to complete the tasks in each bucket, then add 50% for each bucket. (2) Add in commuting, set-up, or wind-down time, if you need it, to the grand total for all buckets, and then add 50% more than you’ve estimated

Set the brain free!

This process will seem like a burden at the beginning, when the synapses underneath it still need to get stronger (much like how the body responds to exercise). However, as long as these principles are put into action daily, they will become a trusted, second-nature system that frees the brain from distraction and anxiety—and, ultimately,

Difficulty with time management and organization is one of the most common complaints of patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Being unproductive and inefficient also is anxiety-producing and depressing, leaving patients with additional comorbidity.

Although medication can help improve a person’s focus, if the patient is focusing on a set of poorly designed systems, he (she) will see little improvement. A comprehensive approach to improving day-to-day task management, similar to the one I describe here and use with my patients, is therefore as important as medication.

Needed: An ‘organizing principle’

Imagine that supermarkets displayed food in the order it arrives from the food distributors and producers. You’d walk in to the store and see a display of food that lacks hierarchy—1 random item placed next to another. The experience would be jarring, and shopping would be a much slower chore. Furthermore, what if you had to go to 5 stores to cover all your needs?

Yet, that is how most “to-do” lists are executed: A thought comes in, a thought goes down on paper. Or on a sticky note. Or in an app. Or in a calendar. Or all of the above! Often, there is neither an organizing principle (other than perhaps chronological order) or a central repository. No wonder it’s hard to feel present and clear-minded. Add to this disorganization the volume of information coming in from the environment—e-mails, voice mails, texts, notifications, dings, beeps, buzzes, and maybe even snail mail—and the feeling of being overwhelmed grows.

Unconscious motives for maintaining poor systems also might play a role. People with a “need to please” personality type or who are more passive-aggressive in their communication are more likely to overcommit, and then forget or be late completing their tasks, rather than saying “No” from the outset or delegating the work.

Survival basics for time management

Assuming there is simply a skills deficit, you can teach basic time and project management skills to patients with ADHD (and to any patient with suboptimal executive functioning). Here are basic principles to adopt:

- If you can forget it, you will, so all tasks should go onto the to-do list.

- You should keep only 1 list. Adding on “stickies” is not allowed.

- Your list is like an extra lobe of your brain: It should be present at all times, whether you keep it in “the Cloud,” on your desktop, or on paper.

- Review your list and clean it up at least daily. This takes time, but it also saves time—in spades—when you can call upon the right task, at the right time, with energy and drive.

- The first action you should take in the daily review is to weed out or delegate tasks.

- Next, categorize remaining tasks. (Note: The free smartphone app Evernote allows you to do this with “tags.”) Categorizing allows you to process sets of tasks in buckets that can be tackled as a bundle and, therefore, more efficiently. For example, having all of your errands, items to research, and telephone calls that need to be returned in separate buckets allows for speedier processing—as opposed to veering back and forth between line items.

- Then, move remaining high-priority items to the top of the list. However, remember that, if everything is urgent, nothing is. Items that are low-hanging fruit that you can cross off the list in a matter of minutes can be prioritized even if they are not as urgent. By doing that, your list becomes more manageable and your brain can dive deeper into more complex tasks.

- Block out calendar time for each of your buckets with this formula: (1) Estimate how much time you’ll need to complete the tasks in each bucket, then add 50% for each bucket. (2) Add in commuting, set-up, or wind-down time, if you need it, to the grand total for all buckets, and then add 50% more than you’ve estimated

Set the brain free!

This process will seem like a burden at the beginning, when the synapses underneath it still need to get stronger (much like how the body responds to exercise). However, as long as these principles are put into action daily, they will become a trusted, second-nature system that frees the brain from distraction and anxiety—and, ultimately,

Ataxia due to alcohol abuse

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Forget the myths and help your psychiatric patients quit smoking

The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey1,2 (NAMCS) indicates that less than 1 out of 4 (23%) psychiatrists provide smoking cessation counseling to their patients, and even fewer prescribe medications.

What gives? How is it that so many psychiatrists endorse having recently helped a patient quit smoking when the data from large-scale surveys1,2 indicate they do not?

From the “glass is half-full” perspective, the discrepancy might indicate that psychiatrists finally have bought into the message put forth 20 years ago when the American Psychiatric Association first published its clinical practice guidelines for treating nicotine dependence.3 Because the figures I cited from NAMCS reflect data from 2006 to 2010, it is possible that in the last 5 years more psychiatrists have started to help their patients quit smoking. Such an hypothesis is further supported by the increasing number of research papers on smoking cessation in individuals with mental illness published over the past 8 years—a period that coincides with the release of the second edition of the Treating tobacco use and dependence clinical practice guideline from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which highlighted the need for more research in this population of smokers.4

Regardless of the reason, the fact that my informal surveys indicate a likely uptick in activity among psychiatrists to help their patients quit smoking is welcome news. With nearly 1 out of 2 cigarettes sold in the United States being smoked by individuals with psychiatric and substance use disorders,5 psychiatrists and other mental health professionals play a vital role in addressing this epidemic. That our patients smoke at rates 2- to 4-times that of the general population and die decades earlier than their non-smoking, non-mentally ill counterparts6 are compelling reasons urging us to end our complacency and help our patients quit smoking.

EAGLES trial results help debunk the latest myth about smoking cessation

In an article that I wrote for

In addition to applying the “black-box” warning, the FDA issued a post-marketing requirement to the manufacturers of bupropion and varenicline to conduct a large randomized controlled trial—Evaluating Adverse Events in a Global Smoking Cessation Study (EAGLES)—the top-line results of which were published in The Lancet this spring.12

Key results of the EAGLES trial

The researchers found no significant increase in serious neuropsychiatric AEs—a composite measure assessing depression, anxiety, suicidality, and 13 other symptom clusters—attributable to varenicline or bupropion compared with placebo or the nicotine patch in smokers with or without psychiatric disorders. The study did detect a significant difference—approximately 4% (2% in non-psychiatric cohort vs 6% in psychiatric cohort)—in the rate of serious neuropsychiatric AEs regardless of treatment condition. In both cohorts, varenicline was more effective than bupropion, which had similar efficacy to the nicotine patch; all interventions were superior to placebo. Importantly, all 3 medications significantly improved quit rates in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders. Although the efficacy of medications in smokers with or without psychiatric disorders was similar in terms of odds ratios, overall, those with psychiatric disorders had 20% to 30% lower quit rates compared with non-psychiatrically ill smokers.

The EAGLES study results, when viewed in the context of findings from other clinical trials and large-scale observational studies, provide further evidence that smokers with stable mental illness can use bupropion and varenicline safely. It also demonstrates that moderate to severe neuropsychiatric AEs occur during a smoking cessation attempt regardless of the medication used, therefore, monitoring smokers—especially those with psychiatric disorders—is important, a role that psychiatrists are uniquely poised to play.

That all 3 smoking cessation medications are effective in patients with mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders is good news for our patients. Combined with the EAGLES safety findings, there is no better time to intervene in tobacco dependence

1. Rogers E, Sherman S. Tobacco use screening and treatment by outpatient psychiatrists before and after release of the American Psychiatric Association treatment guidelines for nicotine dependence. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):90-95.

2. Himelhoch S, Daumit G. To whom do psychiatrists offer smoking-cessation counseling? Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(12):2228-2230.

3. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with nicotine dependence. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;53;153(suppl 10):1-31.

4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Clinical practice guideline. http://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/clinicians/update/treating_tobacco_use08.pdf. Published May 2008. Accessed September 12, 2016.

5. Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, et al. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(11):1107-1115.

6. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42.

7. Anthenelli RM. How—and why—to help psychiatric patients stop smoking. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(1):77-87.

8. Zyban [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC; GlaxoSmithKline; 2016.

9. Chantix [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer; 2016.

10. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking – 50 years of progress: a report of the surgeon general, 2014. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014.

11. World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2011: warning about the dangers of tobacco. http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2011/en/index.html. Published 2011. Accessed December 1, 2015.

12. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;18;387(10037):2507-2520.

13. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

14. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, patient edition (SCID-I/P). New York, NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002.

15. First M, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II personality disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1997.

16. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361-370.

17. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;168(12):1266-1277.

The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey1,2 (NAMCS) indicates that less than 1 out of 4 (23%) psychiatrists provide smoking cessation counseling to their patients, and even fewer prescribe medications.

What gives? How is it that so many psychiatrists endorse having recently helped a patient quit smoking when the data from large-scale surveys1,2 indicate they do not?

From the “glass is half-full” perspective, the discrepancy might indicate that psychiatrists finally have bought into the message put forth 20 years ago when the American Psychiatric Association first published its clinical practice guidelines for treating nicotine dependence.3 Because the figures I cited from NAMCS reflect data from 2006 to 2010, it is possible that in the last 5 years more psychiatrists have started to help their patients quit smoking. Such an hypothesis is further supported by the increasing number of research papers on smoking cessation in individuals with mental illness published over the past 8 years—a period that coincides with the release of the second edition of the Treating tobacco use and dependence clinical practice guideline from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which highlighted the need for more research in this population of smokers.4

Regardless of the reason, the fact that my informal surveys indicate a likely uptick in activity among psychiatrists to help their patients quit smoking is welcome news. With nearly 1 out of 2 cigarettes sold in the United States being smoked by individuals with psychiatric and substance use disorders,5 psychiatrists and other mental health professionals play a vital role in addressing this epidemic. That our patients smoke at rates 2- to 4-times that of the general population and die decades earlier than their non-smoking, non-mentally ill counterparts6 are compelling reasons urging us to end our complacency and help our patients quit smoking.

EAGLES trial results help debunk the latest myth about smoking cessation

In an article that I wrote for

In addition to applying the “black-box” warning, the FDA issued a post-marketing requirement to the manufacturers of bupropion and varenicline to conduct a large randomized controlled trial—Evaluating Adverse Events in a Global Smoking Cessation Study (EAGLES)—the top-line results of which were published in The Lancet this spring.12

Key results of the EAGLES trial

The researchers found no significant increase in serious neuropsychiatric AEs—a composite measure assessing depression, anxiety, suicidality, and 13 other symptom clusters—attributable to varenicline or bupropion compared with placebo or the nicotine patch in smokers with or without psychiatric disorders. The study did detect a significant difference—approximately 4% (2% in non-psychiatric cohort vs 6% in psychiatric cohort)—in the rate of serious neuropsychiatric AEs regardless of treatment condition. In both cohorts, varenicline was more effective than bupropion, which had similar efficacy to the nicotine patch; all interventions were superior to placebo. Importantly, all 3 medications significantly improved quit rates in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders. Although the efficacy of medications in smokers with or without psychiatric disorders was similar in terms of odds ratios, overall, those with psychiatric disorders had 20% to 30% lower quit rates compared with non-psychiatrically ill smokers.

The EAGLES study results, when viewed in the context of findings from other clinical trials and large-scale observational studies, provide further evidence that smokers with stable mental illness can use bupropion and varenicline safely. It also demonstrates that moderate to severe neuropsychiatric AEs occur during a smoking cessation attempt regardless of the medication used, therefore, monitoring smokers—especially those with psychiatric disorders—is important, a role that psychiatrists are uniquely poised to play.

That all 3 smoking cessation medications are effective in patients with mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders is good news for our patients. Combined with the EAGLES safety findings, there is no better time to intervene in tobacco dependence

The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey1,2 (NAMCS) indicates that less than 1 out of 4 (23%) psychiatrists provide smoking cessation counseling to their patients, and even fewer prescribe medications.

What gives? How is it that so many psychiatrists endorse having recently helped a patient quit smoking when the data from large-scale surveys1,2 indicate they do not?

From the “glass is half-full” perspective, the discrepancy might indicate that psychiatrists finally have bought into the message put forth 20 years ago when the American Psychiatric Association first published its clinical practice guidelines for treating nicotine dependence.3 Because the figures I cited from NAMCS reflect data from 2006 to 2010, it is possible that in the last 5 years more psychiatrists have started to help their patients quit smoking. Such an hypothesis is further supported by the increasing number of research papers on smoking cessation in individuals with mental illness published over the past 8 years—a period that coincides with the release of the second edition of the Treating tobacco use and dependence clinical practice guideline from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which highlighted the need for more research in this population of smokers.4

Regardless of the reason, the fact that my informal surveys indicate a likely uptick in activity among psychiatrists to help their patients quit smoking is welcome news. With nearly 1 out of 2 cigarettes sold in the United States being smoked by individuals with psychiatric and substance use disorders,5 psychiatrists and other mental health professionals play a vital role in addressing this epidemic. That our patients smoke at rates 2- to 4-times that of the general population and die decades earlier than their non-smoking, non-mentally ill counterparts6 are compelling reasons urging us to end our complacency and help our patients quit smoking.

EAGLES trial results help debunk the latest myth about smoking cessation

In an article that I wrote for

In addition to applying the “black-box” warning, the FDA issued a post-marketing requirement to the manufacturers of bupropion and varenicline to conduct a large randomized controlled trial—Evaluating Adverse Events in a Global Smoking Cessation Study (EAGLES)—the top-line results of which were published in The Lancet this spring.12

Key results of the EAGLES trial

The researchers found no significant increase in serious neuropsychiatric AEs—a composite measure assessing depression, anxiety, suicidality, and 13 other symptom clusters—attributable to varenicline or bupropion compared with placebo or the nicotine patch in smokers with or without psychiatric disorders. The study did detect a significant difference—approximately 4% (2% in non-psychiatric cohort vs 6% in psychiatric cohort)—in the rate of serious neuropsychiatric AEs regardless of treatment condition. In both cohorts, varenicline was more effective than bupropion, which had similar efficacy to the nicotine patch; all interventions were superior to placebo. Importantly, all 3 medications significantly improved quit rates in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders. Although the efficacy of medications in smokers with or without psychiatric disorders was similar in terms of odds ratios, overall, those with psychiatric disorders had 20% to 30% lower quit rates compared with non-psychiatrically ill smokers.

The EAGLES study results, when viewed in the context of findings from other clinical trials and large-scale observational studies, provide further evidence that smokers with stable mental illness can use bupropion and varenicline safely. It also demonstrates that moderate to severe neuropsychiatric AEs occur during a smoking cessation attempt regardless of the medication used, therefore, monitoring smokers—especially those with psychiatric disorders—is important, a role that psychiatrists are uniquely poised to play.

That all 3 smoking cessation medications are effective in patients with mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders is good news for our patients. Combined with the EAGLES safety findings, there is no better time to intervene in tobacco dependence

1. Rogers E, Sherman S. Tobacco use screening and treatment by outpatient psychiatrists before and after release of the American Psychiatric Association treatment guidelines for nicotine dependence. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):90-95.

2. Himelhoch S, Daumit G. To whom do psychiatrists offer smoking-cessation counseling? Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(12):2228-2230.

3. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with nicotine dependence. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;53;153(suppl 10):1-31.

4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Clinical practice guideline. http://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/clinicians/update/treating_tobacco_use08.pdf. Published May 2008. Accessed September 12, 2016.

5. Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, et al. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(11):1107-1115.

6. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42.

7. Anthenelli RM. How—and why—to help psychiatric patients stop smoking. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(1):77-87.

8. Zyban [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC; GlaxoSmithKline; 2016.

9. Chantix [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer; 2016.

10. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking – 50 years of progress: a report of the surgeon general, 2014. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014.

11. World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2011: warning about the dangers of tobacco. http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2011/en/index.html. Published 2011. Accessed December 1, 2015.

12. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;18;387(10037):2507-2520.

13. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

14. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, patient edition (SCID-I/P). New York, NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002.

15. First M, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II personality disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1997.

16. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361-370.

17. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;168(12):1266-1277.

1. Rogers E, Sherman S. Tobacco use screening and treatment by outpatient psychiatrists before and after release of the American Psychiatric Association treatment guidelines for nicotine dependence. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):90-95.

2. Himelhoch S, Daumit G. To whom do psychiatrists offer smoking-cessation counseling? Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(12):2228-2230.

3. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with nicotine dependence. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;53;153(suppl 10):1-31.

4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Clinical practice guideline. http://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/clinicians/update/treating_tobacco_use08.pdf. Published May 2008. Accessed September 12, 2016.

5. Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, et al. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(11):1107-1115.

6. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42.

7. Anthenelli RM. How—and why—to help psychiatric patients stop smoking. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(1):77-87.

8. Zyban [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC; GlaxoSmithKline; 2016.

9. Chantix [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer; 2016.

10. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking – 50 years of progress: a report of the surgeon general, 2014. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014.

11. World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2011: warning about the dangers of tobacco. http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2011/en/index.html. Published 2011. Accessed December 1, 2015.

12. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;18;387(10037):2507-2520.

13. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

14. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, patient edition (SCID-I/P). New York, NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002.

15. First M, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II personality disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1997.

16. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361-370.

17. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;168(12):1266-1277.

Don’t balk at using medical therapy to manage alcohol use disorder

There is ample evidence in the medical literature, as well as clinical experience, that patients seeking help for chemical dependency benefit from pharmacotherapy. It is common, however, for physicians, patients, and family to balk at the idea. Even within the psychiatry community, where there should be better understanding of substance use disorders, many practitioners hesitate to employ medications, especially for alcohol use disorder (AUD).

Efficacy for such FDA-approved medications has been demonstrated in well-designed, randomized controlled trials, but many trainees, and even experienced professionals, have never seen these medications used effectively and appropriately. Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is not an alternative to biopsychosocial approaches but is an augmentation that can (1) help stabilize the patient until he (she) can be educated in relapse prevention skills and (2) allow the brain to rewire and heal until he regains impulse control.

Diverse presentations

Do you remember that patient who often arrived for appointments intoxicated, promising that he plans to cut down? How about the man you saw in the emergency department with an elevated blood alcohol level, who was constantly endorsing suicidal thoughts that subsided when he reached clinical sobriety? What about the college student who often was treated for alcohol poisoning after binge drinking on weekends, but who never considered this behavior problematic? And, how about the elderly woman who was evaluated for anxiety, but had been drinking 4 beers nightly for the past 30 years?

Despite the diverse presentations, these patients all have a chronic disease and we fail them when we do not apply evidence-based medicine to their treatment.

As psychiatrists, we encounter many patients with AUD as a primary or comorbid diagnosis. This is a global problem associated with significant human and financial cost. With 80% of American adolescents having reported using alcohol in the past year, the problem will continue to grow.1 Furthermore, a greater prevalence of AUD is noted in clinical populations undergoing psychiatric treatment.2 Ongoing alcohol abuse complicates the course of medical and psychiatric conditions and incites significant societal exclusion.

Pharmacotherapy is underutilized

Despite an increase in the use of psychotropic medications for treating psychiatric illness, pharmacotherapy for AUD is underutilized: only 3% of patients have received an FDA-approved treatment.2,3 Nearly one-third of adults are affected by AUD during their lifetime, yet only 20% seek help.3 Management today remains limited to episodic, brief inpatient detoxification and psychosocial therapy.

Recovery rates are highest when addiction treatment that monitors abstinence is continuous; yet, for most part, alcohol addiction is treated in discrete episodes upon relapse. Although MAT is recommended by experts for “moderate” and “severe” substance use disorders, practitioners, in general, have demonstrated considerable resistance to using this modality as part of routine practice.4,5 This is regrettable: Regardless of terminology used to describe their condition, these people suffer a potentially fatal disease characterized by high post-treatment recidivism.

Neuroscience supports the brain disease model of addiction, with neuroplasticity changes being made during phases of drug use. Medications are shown to assist in preventing relapse while the brain is healing and normal emotional and decision-making capacities are being restored.6

Why hesitate to use pharmacotherapeutics?

There are diverse pharmacotherapeutic options that can be pursued for treating AUD with minimal disruption to home and work life. Alarmingly, many trainees have never prescribed or even considered such medications. Despite modest effect sizes in randomized controlled trials, efficacy has been demonstrated in reducing relapse rates and overall severity of drinking days.4,5 So, from where does the ambivalence of patients and providers about using these treatments to achieve lasting recovery stem?

Starting MAT certainly requires both parties to be in agreement. A patient might decline medication because of a fear of dependence or because he overestimates his ability to achieve remission on his own. There also may be financial barriers in a current alcohol treatment system that is traditionally non-medically oriented. Prescribers also fail to offer medications because of:

- lack of familiarity with available agents

- absence of guidelines for use

- disbelief that the condition is treatable.

Given that treatment often is based on a 12-step approach, such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), providers might hesitate to prescribe medication for an illness that is thought to be managed through psychosocial interventions, such as group and motivational therapy.

Therapeutic options

Choice of medication depends on the prescriber’s comfort level, reputation of the medication, potential side-effect profile, medical contraindications, and affordability; the most important consideration, however, should be the overall goals and expectations of the patient.

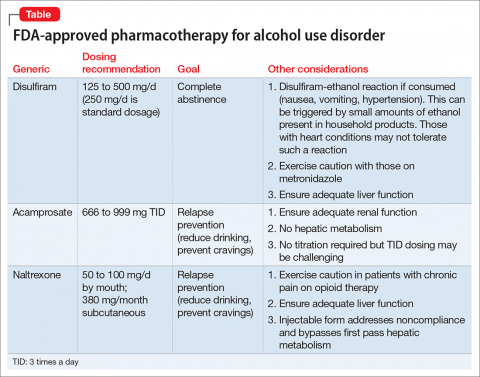

There are 4 FDA-approved medications for AUD (Table); many others are off-label. It is advisable to start with an FDA-approved medication such as disulfiram for the motivated patient who has a collaborator and desires complete abstinence; naltrexone for a patient who wants to cut down on intake (a long-acting formulation can be used for poorly adherent patients); and acamprosate for a patient with at least some established sobriety who needs help with post-withdrawal sleep disturbances.

With regard to off-label medications, topiramate has the highest evidence for efficacy. Gabapentin can augment naltrexone and also helps with sleep, anxiety, withdrawal, and cravings.4,5

Psychosocial interventions

Medications are just 1 tool in recovery; patients should be engaged in a program of counseling. Encourage attendance at AA meetings. An up-and-coming concept is the use of smartphone applications to prevent relapse (or even induce remission); apps that provide an accurate blood alcohol tracking systems and integrated psychosocial therapies are in the pipeline. The novel Reddit online forum r/StopDrinking is a 24-hour peer-support community that relies on

fellowship, accountability, monitoring, and anonymity; the forum can compete with

motivational interviewing for efficacy in increasing abstinence and preventing relapse.

1. Johnson L, O’Malley P, Miech RA, et al. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2015: overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2015.pdf. Published February 2016. Accessed January 20, 2016.

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 national survey on drug use and health: mental health findings, NSDUH Series H-49, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4887. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014.

3. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):757-766.

4. Robinson S, Meeks TW, Geniza C. Medication for alcohol use disorder: which agents work best. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(1):22-29.

5. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Medication for the treatment of alcohol use disorder: a brief guide. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 15-4907. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015.

6. Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT. Neurobiological advances from the brain disease model of addiction. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):363-371.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Thomas M. Penders, MS, MD, Medical Director for Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry at Cape Cod Healthcare, Hyannis, Massachusetts, and Affiliate Professor at East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, for all his guidance, support, and mentorship.

There is ample evidence in the medical literature, as well as clinical experience, that patients seeking help for chemical dependency benefit from pharmacotherapy. It is common, however, for physicians, patients, and family to balk at the idea. Even within the psychiatry community, where there should be better understanding of substance use disorders, many practitioners hesitate to employ medications, especially for alcohol use disorder (AUD).

Efficacy for such FDA-approved medications has been demonstrated in well-designed, randomized controlled trials, but many trainees, and even experienced professionals, have never seen these medications used effectively and appropriately. Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is not an alternative to biopsychosocial approaches but is an augmentation that can (1) help stabilize the patient until he (she) can be educated in relapse prevention skills and (2) allow the brain to rewire and heal until he regains impulse control.

Diverse presentations

Do you remember that patient who often arrived for appointments intoxicated, promising that he plans to cut down? How about the man you saw in the emergency department with an elevated blood alcohol level, who was constantly endorsing suicidal thoughts that subsided when he reached clinical sobriety? What about the college student who often was treated for alcohol poisoning after binge drinking on weekends, but who never considered this behavior problematic? And, how about the elderly woman who was evaluated for anxiety, but had been drinking 4 beers nightly for the past 30 years?

Despite the diverse presentations, these patients all have a chronic disease and we fail them when we do not apply evidence-based medicine to their treatment.

As psychiatrists, we encounter many patients with AUD as a primary or comorbid diagnosis. This is a global problem associated with significant human and financial cost. With 80% of American adolescents having reported using alcohol in the past year, the problem will continue to grow.1 Furthermore, a greater prevalence of AUD is noted in clinical populations undergoing psychiatric treatment.2 Ongoing alcohol abuse complicates the course of medical and psychiatric conditions and incites significant societal exclusion.

Pharmacotherapy is underutilized

Despite an increase in the use of psychotropic medications for treating psychiatric illness, pharmacotherapy for AUD is underutilized: only 3% of patients have received an FDA-approved treatment.2,3 Nearly one-third of adults are affected by AUD during their lifetime, yet only 20% seek help.3 Management today remains limited to episodic, brief inpatient detoxification and psychosocial therapy.

Recovery rates are highest when addiction treatment that monitors abstinence is continuous; yet, for most part, alcohol addiction is treated in discrete episodes upon relapse. Although MAT is recommended by experts for “moderate” and “severe” substance use disorders, practitioners, in general, have demonstrated considerable resistance to using this modality as part of routine practice.4,5 This is regrettable: Regardless of terminology used to describe their condition, these people suffer a potentially fatal disease characterized by high post-treatment recidivism.

Neuroscience supports the brain disease model of addiction, with neuroplasticity changes being made during phases of drug use. Medications are shown to assist in preventing relapse while the brain is healing and normal emotional and decision-making capacities are being restored.6

Why hesitate to use pharmacotherapeutics?

There are diverse pharmacotherapeutic options that can be pursued for treating AUD with minimal disruption to home and work life. Alarmingly, many trainees have never prescribed or even considered such medications. Despite modest effect sizes in randomized controlled trials, efficacy has been demonstrated in reducing relapse rates and overall severity of drinking days.4,5 So, from where does the ambivalence of patients and providers about using these treatments to achieve lasting recovery stem?

Starting MAT certainly requires both parties to be in agreement. A patient might decline medication because of a fear of dependence or because he overestimates his ability to achieve remission on his own. There also may be financial barriers in a current alcohol treatment system that is traditionally non-medically oriented. Prescribers also fail to offer medications because of:

- lack of familiarity with available agents

- absence of guidelines for use

- disbelief that the condition is treatable.

Given that treatment often is based on a 12-step approach, such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), providers might hesitate to prescribe medication for an illness that is thought to be managed through psychosocial interventions, such as group and motivational therapy.

Therapeutic options

Choice of medication depends on the prescriber’s comfort level, reputation of the medication, potential side-effect profile, medical contraindications, and affordability; the most important consideration, however, should be the overall goals and expectations of the patient.

There are 4 FDA-approved medications for AUD (Table); many others are off-label. It is advisable to start with an FDA-approved medication such as disulfiram for the motivated patient who has a collaborator and desires complete abstinence; naltrexone for a patient who wants to cut down on intake (a long-acting formulation can be used for poorly adherent patients); and acamprosate for a patient with at least some established sobriety who needs help with post-withdrawal sleep disturbances.

With regard to off-label medications, topiramate has the highest evidence for efficacy. Gabapentin can augment naltrexone and also helps with sleep, anxiety, withdrawal, and cravings.4,5

Psychosocial interventions

Medications are just 1 tool in recovery; patients should be engaged in a program of counseling. Encourage attendance at AA meetings. An up-and-coming concept is the use of smartphone applications to prevent relapse (or even induce remission); apps that provide an accurate blood alcohol tracking systems and integrated psychosocial therapies are in the pipeline. The novel Reddit online forum r/StopDrinking is a 24-hour peer-support community that relies on

fellowship, accountability, monitoring, and anonymity; the forum can compete with

motivational interviewing for efficacy in increasing abstinence and preventing relapse.

There is ample evidence in the medical literature, as well as clinical experience, that patients seeking help for chemical dependency benefit from pharmacotherapy. It is common, however, for physicians, patients, and family to balk at the idea. Even within the psychiatry community, where there should be better understanding of substance use disorders, many practitioners hesitate to employ medications, especially for alcohol use disorder (AUD).

Efficacy for such FDA-approved medications has been demonstrated in well-designed, randomized controlled trials, but many trainees, and even experienced professionals, have never seen these medications used effectively and appropriately. Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is not an alternative to biopsychosocial approaches but is an augmentation that can (1) help stabilize the patient until he (she) can be educated in relapse prevention skills and (2) allow the brain to rewire and heal until he regains impulse control.

Diverse presentations

Do you remember that patient who often arrived for appointments intoxicated, promising that he plans to cut down? How about the man you saw in the emergency department with an elevated blood alcohol level, who was constantly endorsing suicidal thoughts that subsided when he reached clinical sobriety? What about the college student who often was treated for alcohol poisoning after binge drinking on weekends, but who never considered this behavior problematic? And, how about the elderly woman who was evaluated for anxiety, but had been drinking 4 beers nightly for the past 30 years?

Despite the diverse presentations, these patients all have a chronic disease and we fail them when we do not apply evidence-based medicine to their treatment.

As psychiatrists, we encounter many patients with AUD as a primary or comorbid diagnosis. This is a global problem associated with significant human and financial cost. With 80% of American adolescents having reported using alcohol in the past year, the problem will continue to grow.1 Furthermore, a greater prevalence of AUD is noted in clinical populations undergoing psychiatric treatment.2 Ongoing alcohol abuse complicates the course of medical and psychiatric conditions and incites significant societal exclusion.

Pharmacotherapy is underutilized

Despite an increase in the use of psychotropic medications for treating psychiatric illness, pharmacotherapy for AUD is underutilized: only 3% of patients have received an FDA-approved treatment.2,3 Nearly one-third of adults are affected by AUD during their lifetime, yet only 20% seek help.3 Management today remains limited to episodic, brief inpatient detoxification and psychosocial therapy.

Recovery rates are highest when addiction treatment that monitors abstinence is continuous; yet, for most part, alcohol addiction is treated in discrete episodes upon relapse. Although MAT is recommended by experts for “moderate” and “severe” substance use disorders, practitioners, in general, have demonstrated considerable resistance to using this modality as part of routine practice.4,5 This is regrettable: Regardless of terminology used to describe their condition, these people suffer a potentially fatal disease characterized by high post-treatment recidivism.

Neuroscience supports the brain disease model of addiction, with neuroplasticity changes being made during phases of drug use. Medications are shown to assist in preventing relapse while the brain is healing and normal emotional and decision-making capacities are being restored.6

Why hesitate to use pharmacotherapeutics?

There are diverse pharmacotherapeutic options that can be pursued for treating AUD with minimal disruption to home and work life. Alarmingly, many trainees have never prescribed or even considered such medications. Despite modest effect sizes in randomized controlled trials, efficacy has been demonstrated in reducing relapse rates and overall severity of drinking days.4,5 So, from where does the ambivalence of patients and providers about using these treatments to achieve lasting recovery stem?

Starting MAT certainly requires both parties to be in agreement. A patient might decline medication because of a fear of dependence or because he overestimates his ability to achieve remission on his own. There also may be financial barriers in a current alcohol treatment system that is traditionally non-medically oriented. Prescribers also fail to offer medications because of:

- lack of familiarity with available agents

- absence of guidelines for use

- disbelief that the condition is treatable.

Given that treatment often is based on a 12-step approach, such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), providers might hesitate to prescribe medication for an illness that is thought to be managed through psychosocial interventions, such as group and motivational therapy.

Therapeutic options

Choice of medication depends on the prescriber’s comfort level, reputation of the medication, potential side-effect profile, medical contraindications, and affordability; the most important consideration, however, should be the overall goals and expectations of the patient.

There are 4 FDA-approved medications for AUD (Table); many others are off-label. It is advisable to start with an FDA-approved medication such as disulfiram for the motivated patient who has a collaborator and desires complete abstinence; naltrexone for a patient who wants to cut down on intake (a long-acting formulation can be used for poorly adherent patients); and acamprosate for a patient with at least some established sobriety who needs help with post-withdrawal sleep disturbances.

With regard to off-label medications, topiramate has the highest evidence for efficacy. Gabapentin can augment naltrexone and also helps with sleep, anxiety, withdrawal, and cravings.4,5

Psychosocial interventions

Medications are just 1 tool in recovery; patients should be engaged in a program of counseling. Encourage attendance at AA meetings. An up-and-coming concept is the use of smartphone applications to prevent relapse (or even induce remission); apps that provide an accurate blood alcohol tracking systems and integrated psychosocial therapies are in the pipeline. The novel Reddit online forum r/StopDrinking is a 24-hour peer-support community that relies on

fellowship, accountability, monitoring, and anonymity; the forum can compete with

motivational interviewing for efficacy in increasing abstinence and preventing relapse.

1. Johnson L, O’Malley P, Miech RA, et al. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2015: overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2015.pdf. Published February 2016. Accessed January 20, 2016.

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 national survey on drug use and health: mental health findings, NSDUH Series H-49, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4887. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014.

3. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):757-766.

4. Robinson S, Meeks TW, Geniza C. Medication for alcohol use disorder: which agents work best. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(1):22-29.

5. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Medication for the treatment of alcohol use disorder: a brief guide. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 15-4907. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015.

6. Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT. Neurobiological advances from the brain disease model of addiction. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):363-371.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Thomas M. Penders, MS, MD, Medical Director for Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry at Cape Cod Healthcare, Hyannis, Massachusetts, and Affiliate Professor at East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, for all his guidance, support, and mentorship.

1. Johnson L, O’Malley P, Miech RA, et al. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2015: overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2015.pdf. Published February 2016. Accessed January 20, 2016.

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 national survey on drug use and health: mental health findings, NSDUH Series H-49, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4887. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014.

3. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):757-766.

4. Robinson S, Meeks TW, Geniza C. Medication for alcohol use disorder: which agents work best. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(1):22-29.