User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Violent behavior in autism spectrum disorder: Is it a fact, or fiction?

When Kanner first described autism,1 the disorder was believed to be an uncommon condition, occurring in 4 of every 10,000 children. Over the past few years, however, the rate of autism has increased substantially. Autism is now regarded as a childhood-onset spectrum disordera characterized by persistent deficits in social communication, with a restricted pattern of interests and activities, occurring in approximately 1% of children.3

In DSM-IV-TR, Asperger’s disorder (AD), first described as “autistic psychopathy,”4 is categorized as a subtype of ASD in which the patient, without a history of language delay or mental retardation, has autistic social deficits that do not meet full criteria for autism.

DSM-5 eliminated AD as an independent category, including it instead as part of ASD.5 The label “high-functioning autism” is sometimes used to refer to persons with autism who have normal intelligence (usually defined as full-scale IQ >70), whereas those who have severe intellectual and communication disability are referred to as “low-functioning.” I use “high-functioning autism” and “Asperger’s disorder” interchangeably.

Violent crime and ASD/AD

Reports in the past 2 decades have described violent behavior in persons with ASD/AD. Because of the sensational and unusual nature of these criminal incidents, there is a perception by the public that persons with these disorders, especially those with AD, are predisposed to violent behavior. (Incidents allegedly committed by persons with ASD include the 2007 Virginia Tech campus shooting and the 2012 Newtown, Connecticut, school massacre.6)

Yet neither the original descriptions by Kanner (of autism) and Asperger, nor follow-up studies based on the initial samples studied, showed an increased prevalence of violent crime among persons with ASD/AD.7

In this article, I examine the evidence behind the claim that people who have ASD/AD are predisposed to criminal violence. At the conclusion, you should, as a physician without special training in autism, have a better understanding of when to suspect ASD/AD in an adult who is involved in criminal behavior.

When should you suspect ASD/AD in an adult?

Although autism is a childhood-onset disorder, its symptoms persist across the life

span. If the diagnosis is missed in childhood, which is likely to happen if the person has normal intelligence and relatively good verbal skills, he (she) might come to medical attention for the first time as an adult.

Because most psychiatrists who treat adults do not receive adequate training in the assessment of childhood psychiatric disorders, ASD/AD might be misdiagnosed as schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder. What clues help identify underlying ASD/AD when a patient is referred to you for psychiatric evaluation after allegedly committing a violent crime?

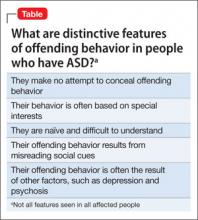

Clue #1. He makes no attempt to deny or conceal the act. The behavior appears to be part of ritualistic behavior or excessive interest (Table).

Often, the alleged crime occurs when the patient’s excessive interests “get out of control,” perhaps because of an external event. For example, a teenager with AD who is fixated on video games might stumble upon pornographic web sites and begin making obscene telephone calls. Particular attention should be paid to a history of rigid, restricted interests beginning in early childhood.

These restricted interests change over time and correlate with intelligence level: The higher the level of intelligence, the more sophisticated the level of fixation. Examples of fixations include computers, technology, and scientific experiments and pursuits. Repeated acts of arson have been reported to be part of an autistic person’s fixation with starting fires.8

Clue #2. He appears to lack sound and prudent judgment despite normal intelligence.

Although most patients with ASD score in the intellectually disabled or mentally retarded range, at least one-third have an IQ in the normal range.9 Examine school records and reports from other agencies when evaluating a patient. Pay attention to a history of difficulty relating to peers at an early age, combined with evidence of rigid, restricted fixations and interests.

It is important to obtain a reliable history going back to early childhood, and not rely just on the patient’s mental status; presenting symptoms might mask underlying traits of ASD, especially in higher-functioning adults. (I once cared for a young man with ASD who had been fired a few days after landing his first job selling used cars because he was “sexually harassing” his colleagues. When questioned, he said that he was only trying to be “friendly” and “practicing his social skills.”)

Clue #3. He has been given a diagnosis of schizophrenia without a clear history of hallucinations or delusions.

Differentiating chronic schizophrenia and autism in adults is not always easy, especially in those who have an intellectual disability. In patients whose cognitive and verbal skills are relatively well preserved (such as AD), the presence of intense, focused interests, a pedantic manner of speaking, and abnormalities of nonverbal communication can help clarify the diagnosis. In particular, a recorded history of “childhood schizophrenia” or “obsessive-compulsive behavior” going back to preschool years should alert you to possible ASD.

Scales and screens. Apart from obtaining an accurate developmental history from a variety of sources, you can use rating scales and screening instruments, such as the Social and Communication Questionnaire10—although their utility is limited in adults. It is important not to risk overdiagnosis on the basis of these instruments alone: The gold standard of diagnosis remains clinical. The critical point is that the combination of core symptoms of social communication deficits and restricted interests is more important than the presence of a single symptom. A touch of oddity does not mean that one has ASD/AD.

Is the prevalence of violent crime increased in ASD/AD?

It is important to distinguish violent crime from aggressive behavior. The latter, which can be verbal or nonverbal, is not always intentional or malevolent. In some persons who have an intellectual disability, a desire to communicate might lead to inappropriate touching or pushing. This distinction is particularly relevant to psychiatrists because many people who have ASD have an intellectual disability.

Violent crime is more deliberate, serious, and planned. It involves force or threat of force. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation Uniform Crime Reporting Program, violent crime comprises four offenses: murder and non-negligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault.11

Earlier descriptions of ASD/AD did not mention criminal violence as an important feature of these disorders. However, reports began to emerge about two decades ago suggesting that people who have ASD—particularly AD—are prone to violent crime. Some of the patients described in Wing’s original series12 of AD showed violent tendencies, ranging from sudden outbursts of violence to injury to others because of fixation on hobbies such as chemistry experimentation.

Reports such as these were based on isolated case reports or select samples, such as residents of maximum-security hospitals. Scragg and Shah, for example, surveyed the male population of Broadmoor Hospital, a high-security facility in the United Kingdom, and found that the prevalence of AD was higher than expected in the general population.13

Recent reports have not been able to confirm that violent crime is increased in persons with ASD, however:

- In a clinical sample of 313 Danish adults with ASD (age 25 to 59) drawn from the Danish Register of Criminality, Mouridsen and colleagues found that persons with ASD had a lower rate of criminal conviction than matched controls (9%, compared with 18%).14

- In a small community study, Woodbury-Smith and colleagues examined the prevalence rates and types of offending behavior in persons with ASD. Based on official records, only two (18%) had a history of criminal conviction.15

The role of psychiatric comorbidity

Psychiatric disorders are common in persons who have ASD. In one study, 70% of a sample of 114 children with ASD (age 10 to 14) had a psychiatric disorder, based on a parent interview.16 Although people with mental illness are not inherently criminal or violent, having an additional psychiatric disorder independently increases the risk of offending behavior.17 For example, the association of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with criminality is well established.16 Some patients with severe depression and psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia, also are at increased risk of committing a violent act.

To examine the contribution of mental health factors to the commission of crime by persons with ASD, Newman and Ghaziuddin18 used online databases to identify relevant articles, which were then cross-referenced with keyword searches for “violence,” “crime,” “murder,” “assault,” “rape,” and “sex offenses.” Thirty-seven cases were identified in the 17 publications that met inclusion criteria. Out of these, 30% had a definite psychiatric disorder and 54% had a probable psychiatric disorder at the time they committed the crime.18

Any patient with ASD/AD who is evaluated for criminal behavior should be screened for a comorbid psychiatric disorder. In adolescents, stressors such as bullying in school and problems surrounding dating might contribute to offending behavior.

What are management options in the face of violence?

Managing ASD/AD when an offending behavior has occurred first requires a correct diagnosis.19 Professionals working in the criminal justice system have little awareness of the variants of ASD; a defendant with an intellectual disability and a characteristic facial appearance (for example, someone with Down syndrome) can be easily identified, but a high-functioning person who has mild autistic features often is missed. This is more likely to occur in adults because the symptoms of ASD, including the type and severity of isolated interests, change over time.

Here is how I recommend that you proceed:

Step #1. Confirm the ASD diagnosis based on developmental history and the presence of persistent social and communication deficits plus restricted interests.

Step #2. Screen for comorbid psychiatric and medical disorders, including depression, psychosis, and seizure disorder.

Step #3. Treat any disorders you identify with a combination of medication and behavioral intervention.

Step #4. Carefully examine the circumstances surrounding the offending behavior. Involve forensic services on a case-by-case basis, depending on the type and seriousness of the offending behavior (see Related Resources for information on the role of forensic services). When the crime does not involve serious violence, lengthy incarceration might be unnecessary. Because psychopathy and ASD/AD are not mutually exclusive, persons who commit a heinous crime, such as rape or murder, should be dealt with in accordance with the law.

Need for greater awareness of the complexion of ASD

Patients who have ASD/AD form a heterogeneous group in which the levels of cognitive and communication skills are variable. Those who are low-functioning and who have severe behavioral and adaptive deficits occasionally commit aggressive acts against their caregivers.

Most patients with ASD/AD are neither violent nor criminal. Those who are at the higher end of the spectrum, with relatively preserved communication and intellectual skills, occasionally indulge in criminal behavior—behavior that is nonviolent and results from their inability to read social cues or excessive preoccupations.

Most reports that link criminal violence with ASD are based on isolated case reports or on biased samples that use unreliable diagnostic criteria. In higher-functioning persons with ASD, violent crime is almost always precipitated by a comorbid psychiatric disorder, such as severe depression and psychosis.

In short: There is a need to increase our awareness of the special challenges faced by persons with ASD/AD in the criminal justice system.

aGiven the term pervasive developmental disorders (PDD) in the DSM-IV-TR, the spectrum includes autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified.2

Bottom Line

Most people who have an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) do not commit violent crime. When violent crime occurs at the hands of a person with ASD, it is almost always precipitated by a comorbid psychiatric disorder, such as severe depression or psychosis. Treating a person with ASD who has committed a violent crime is multimodal, including forensic services when necessary.

Related Resources

- Autism Speaks. No link between autism and violence. www.autismspeaks.org/science/science-news/no-link-between-autism-and-violence.

- Haskins BG, Silva JA. Asperger’s disorder and criminal behavior: Forensic-psychiatric considerations. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2006;34(3):374-384.

- Newman SS, Ghaziuddin M. Violent crime and Asperger syndrome: the role of psychiatric comorbidity. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38:1848-1852.

- Wing L. Asperger’s syndrome: a clinical account. Psychol Med. 1981;11(1):115-129.

Disclosure

Dr. Ghaziuddin reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nerv Child. 1943;2:217-250.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2008 Principal Investigators. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders--Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 14 sites, United States, 2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012;61(3):1-19.

4. Asperger H. Die autistichen psychopathen im kindesalter. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr. 1944;117:76-136.

5. Happe F. Criteria, categories, and continua: autism and related disorders in DSM-5. J Am Acad Child and Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:540-542.

6. Walkup JT, Rubin DH. Social withdrawal and violence. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:399-401.

7. Hippler K, Vidding E, Klicpera C, et al. Brief report: no increase in criminal convictions in Asperger’s original cohort. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40:774-780.

8. Siponmaa L, Kristiansson M, Jonson C, et al. Juvenile and young adult mentally disordered offenders: the role of child neuropsychiatric disorders. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2001;29(4):420-426.

9. Matson JL, Shoemaker M. Intellectual disability and its relationship to autism spectrum disorders. Res Dev Disabil. 2009;30(6):1107-1114.

10. Rutter M, Bailey A, Lord C. Social communication questionnaire. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2003.

11. US Department of Justice. Violent crime. http://www2.fbi.gov/ucr/cius2009/offenses/violent_crime. Published September, 2010. Accessed April 26, 2013.

12. Wing L. Asperger’s syndrome: a clinical account. Psychol Med. 1981;11(1):115-129.

13. Scragg P, Shah A. The prevalence of Asperger’s syndrome in a secure hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;165:67-72.

14. Mouridsen SE, Rich B, Isager T, et al. Pervasive developmental disorders and criminal behaviour: a case control study. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2008; 52(2):196-205.

15. Woodbury-Smith MR, Clare ICH, Holland AJ, et al. High functioning autistic spectrum disorders, offending and other law-breaking: findings from a community sample. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol. 2006;17(1):108-120.

16. Simonoff E, Pickles A, Charman T, et al. Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(8):

921-929.

17. Ghaziuddin M. Mental health aspects of autism and Asperger syndrome. London, United Kingdom: Jessica Kingsley Press; 2005.

18. Newman SS, Ghaziuddin M. Violent crime and Asperger syndrome: the role of psychiatric comorbidity. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38:1848-1852.

19. Wing L. Asperger’s syndrome: management requires diagnosis. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry. 1997;8(2):253-257.

When Kanner first described autism,1 the disorder was believed to be an uncommon condition, occurring in 4 of every 10,000 children. Over the past few years, however, the rate of autism has increased substantially. Autism is now regarded as a childhood-onset spectrum disordera characterized by persistent deficits in social communication, with a restricted pattern of interests and activities, occurring in approximately 1% of children.3

In DSM-IV-TR, Asperger’s disorder (AD), first described as “autistic psychopathy,”4 is categorized as a subtype of ASD in which the patient, without a history of language delay or mental retardation, has autistic social deficits that do not meet full criteria for autism.

DSM-5 eliminated AD as an independent category, including it instead as part of ASD.5 The label “high-functioning autism” is sometimes used to refer to persons with autism who have normal intelligence (usually defined as full-scale IQ >70), whereas those who have severe intellectual and communication disability are referred to as “low-functioning.” I use “high-functioning autism” and “Asperger’s disorder” interchangeably.

Violent crime and ASD/AD

Reports in the past 2 decades have described violent behavior in persons with ASD/AD. Because of the sensational and unusual nature of these criminal incidents, there is a perception by the public that persons with these disorders, especially those with AD, are predisposed to violent behavior. (Incidents allegedly committed by persons with ASD include the 2007 Virginia Tech campus shooting and the 2012 Newtown, Connecticut, school massacre.6)

Yet neither the original descriptions by Kanner (of autism) and Asperger, nor follow-up studies based on the initial samples studied, showed an increased prevalence of violent crime among persons with ASD/AD.7

In this article, I examine the evidence behind the claim that people who have ASD/AD are predisposed to criminal violence. At the conclusion, you should, as a physician without special training in autism, have a better understanding of when to suspect ASD/AD in an adult who is involved in criminal behavior.

When should you suspect ASD/AD in an adult?

Although autism is a childhood-onset disorder, its symptoms persist across the life

span. If the diagnosis is missed in childhood, which is likely to happen if the person has normal intelligence and relatively good verbal skills, he (she) might come to medical attention for the first time as an adult.

Because most psychiatrists who treat adults do not receive adequate training in the assessment of childhood psychiatric disorders, ASD/AD might be misdiagnosed as schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder. What clues help identify underlying ASD/AD when a patient is referred to you for psychiatric evaluation after allegedly committing a violent crime?

Clue #1. He makes no attempt to deny or conceal the act. The behavior appears to be part of ritualistic behavior or excessive interest (Table).

Often, the alleged crime occurs when the patient’s excessive interests “get out of control,” perhaps because of an external event. For example, a teenager with AD who is fixated on video games might stumble upon pornographic web sites and begin making obscene telephone calls. Particular attention should be paid to a history of rigid, restricted interests beginning in early childhood.

These restricted interests change over time and correlate with intelligence level: The higher the level of intelligence, the more sophisticated the level of fixation. Examples of fixations include computers, technology, and scientific experiments and pursuits. Repeated acts of arson have been reported to be part of an autistic person’s fixation with starting fires.8

Clue #2. He appears to lack sound and prudent judgment despite normal intelligence.

Although most patients with ASD score in the intellectually disabled or mentally retarded range, at least one-third have an IQ in the normal range.9 Examine school records and reports from other agencies when evaluating a patient. Pay attention to a history of difficulty relating to peers at an early age, combined with evidence of rigid, restricted fixations and interests.

It is important to obtain a reliable history going back to early childhood, and not rely just on the patient’s mental status; presenting symptoms might mask underlying traits of ASD, especially in higher-functioning adults. (I once cared for a young man with ASD who had been fired a few days after landing his first job selling used cars because he was “sexually harassing” his colleagues. When questioned, he said that he was only trying to be “friendly” and “practicing his social skills.”)

Clue #3. He has been given a diagnosis of schizophrenia without a clear history of hallucinations or delusions.

Differentiating chronic schizophrenia and autism in adults is not always easy, especially in those who have an intellectual disability. In patients whose cognitive and verbal skills are relatively well preserved (such as AD), the presence of intense, focused interests, a pedantic manner of speaking, and abnormalities of nonverbal communication can help clarify the diagnosis. In particular, a recorded history of “childhood schizophrenia” or “obsessive-compulsive behavior” going back to preschool years should alert you to possible ASD.

Scales and screens. Apart from obtaining an accurate developmental history from a variety of sources, you can use rating scales and screening instruments, such as the Social and Communication Questionnaire10—although their utility is limited in adults. It is important not to risk overdiagnosis on the basis of these instruments alone: The gold standard of diagnosis remains clinical. The critical point is that the combination of core symptoms of social communication deficits and restricted interests is more important than the presence of a single symptom. A touch of oddity does not mean that one has ASD/AD.

Is the prevalence of violent crime increased in ASD/AD?

It is important to distinguish violent crime from aggressive behavior. The latter, which can be verbal or nonverbal, is not always intentional or malevolent. In some persons who have an intellectual disability, a desire to communicate might lead to inappropriate touching or pushing. This distinction is particularly relevant to psychiatrists because many people who have ASD have an intellectual disability.

Violent crime is more deliberate, serious, and planned. It involves force or threat of force. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation Uniform Crime Reporting Program, violent crime comprises four offenses: murder and non-negligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault.11

Earlier descriptions of ASD/AD did not mention criminal violence as an important feature of these disorders. However, reports began to emerge about two decades ago suggesting that people who have ASD—particularly AD—are prone to violent crime. Some of the patients described in Wing’s original series12 of AD showed violent tendencies, ranging from sudden outbursts of violence to injury to others because of fixation on hobbies such as chemistry experimentation.

Reports such as these were based on isolated case reports or select samples, such as residents of maximum-security hospitals. Scragg and Shah, for example, surveyed the male population of Broadmoor Hospital, a high-security facility in the United Kingdom, and found that the prevalence of AD was higher than expected in the general population.13

Recent reports have not been able to confirm that violent crime is increased in persons with ASD, however:

- In a clinical sample of 313 Danish adults with ASD (age 25 to 59) drawn from the Danish Register of Criminality, Mouridsen and colleagues found that persons with ASD had a lower rate of criminal conviction than matched controls (9%, compared with 18%).14

- In a small community study, Woodbury-Smith and colleagues examined the prevalence rates and types of offending behavior in persons with ASD. Based on official records, only two (18%) had a history of criminal conviction.15

The role of psychiatric comorbidity

Psychiatric disorders are common in persons who have ASD. In one study, 70% of a sample of 114 children with ASD (age 10 to 14) had a psychiatric disorder, based on a parent interview.16 Although people with mental illness are not inherently criminal or violent, having an additional psychiatric disorder independently increases the risk of offending behavior.17 For example, the association of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with criminality is well established.16 Some patients with severe depression and psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia, also are at increased risk of committing a violent act.

To examine the contribution of mental health factors to the commission of crime by persons with ASD, Newman and Ghaziuddin18 used online databases to identify relevant articles, which were then cross-referenced with keyword searches for “violence,” “crime,” “murder,” “assault,” “rape,” and “sex offenses.” Thirty-seven cases were identified in the 17 publications that met inclusion criteria. Out of these, 30% had a definite psychiatric disorder and 54% had a probable psychiatric disorder at the time they committed the crime.18

Any patient with ASD/AD who is evaluated for criminal behavior should be screened for a comorbid psychiatric disorder. In adolescents, stressors such as bullying in school and problems surrounding dating might contribute to offending behavior.

What are management options in the face of violence?

Managing ASD/AD when an offending behavior has occurred first requires a correct diagnosis.19 Professionals working in the criminal justice system have little awareness of the variants of ASD; a defendant with an intellectual disability and a characteristic facial appearance (for example, someone with Down syndrome) can be easily identified, but a high-functioning person who has mild autistic features often is missed. This is more likely to occur in adults because the symptoms of ASD, including the type and severity of isolated interests, change over time.

Here is how I recommend that you proceed:

Step #1. Confirm the ASD diagnosis based on developmental history and the presence of persistent social and communication deficits plus restricted interests.

Step #2. Screen for comorbid psychiatric and medical disorders, including depression, psychosis, and seizure disorder.

Step #3. Treat any disorders you identify with a combination of medication and behavioral intervention.

Step #4. Carefully examine the circumstances surrounding the offending behavior. Involve forensic services on a case-by-case basis, depending on the type and seriousness of the offending behavior (see Related Resources for information on the role of forensic services). When the crime does not involve serious violence, lengthy incarceration might be unnecessary. Because psychopathy and ASD/AD are not mutually exclusive, persons who commit a heinous crime, such as rape or murder, should be dealt with in accordance with the law.

Need for greater awareness of the complexion of ASD

Patients who have ASD/AD form a heterogeneous group in which the levels of cognitive and communication skills are variable. Those who are low-functioning and who have severe behavioral and adaptive deficits occasionally commit aggressive acts against their caregivers.

Most patients with ASD/AD are neither violent nor criminal. Those who are at the higher end of the spectrum, with relatively preserved communication and intellectual skills, occasionally indulge in criminal behavior—behavior that is nonviolent and results from their inability to read social cues or excessive preoccupations.

Most reports that link criminal violence with ASD are based on isolated case reports or on biased samples that use unreliable diagnostic criteria. In higher-functioning persons with ASD, violent crime is almost always precipitated by a comorbid psychiatric disorder, such as severe depression and psychosis.

In short: There is a need to increase our awareness of the special challenges faced by persons with ASD/AD in the criminal justice system.

aGiven the term pervasive developmental disorders (PDD) in the DSM-IV-TR, the spectrum includes autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified.2

Bottom Line

Most people who have an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) do not commit violent crime. When violent crime occurs at the hands of a person with ASD, it is almost always precipitated by a comorbid psychiatric disorder, such as severe depression or psychosis. Treating a person with ASD who has committed a violent crime is multimodal, including forensic services when necessary.

Related Resources

- Autism Speaks. No link between autism and violence. www.autismspeaks.org/science/science-news/no-link-between-autism-and-violence.

- Haskins BG, Silva JA. Asperger’s disorder and criminal behavior: Forensic-psychiatric considerations. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2006;34(3):374-384.

- Newman SS, Ghaziuddin M. Violent crime and Asperger syndrome: the role of psychiatric comorbidity. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38:1848-1852.

- Wing L. Asperger’s syndrome: a clinical account. Psychol Med. 1981;11(1):115-129.

Disclosure

Dr. Ghaziuddin reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

When Kanner first described autism,1 the disorder was believed to be an uncommon condition, occurring in 4 of every 10,000 children. Over the past few years, however, the rate of autism has increased substantially. Autism is now regarded as a childhood-onset spectrum disordera characterized by persistent deficits in social communication, with a restricted pattern of interests and activities, occurring in approximately 1% of children.3

In DSM-IV-TR, Asperger’s disorder (AD), first described as “autistic psychopathy,”4 is categorized as a subtype of ASD in which the patient, without a history of language delay or mental retardation, has autistic social deficits that do not meet full criteria for autism.

DSM-5 eliminated AD as an independent category, including it instead as part of ASD.5 The label “high-functioning autism” is sometimes used to refer to persons with autism who have normal intelligence (usually defined as full-scale IQ >70), whereas those who have severe intellectual and communication disability are referred to as “low-functioning.” I use “high-functioning autism” and “Asperger’s disorder” interchangeably.

Violent crime and ASD/AD

Reports in the past 2 decades have described violent behavior in persons with ASD/AD. Because of the sensational and unusual nature of these criminal incidents, there is a perception by the public that persons with these disorders, especially those with AD, are predisposed to violent behavior. (Incidents allegedly committed by persons with ASD include the 2007 Virginia Tech campus shooting and the 2012 Newtown, Connecticut, school massacre.6)

Yet neither the original descriptions by Kanner (of autism) and Asperger, nor follow-up studies based on the initial samples studied, showed an increased prevalence of violent crime among persons with ASD/AD.7

In this article, I examine the evidence behind the claim that people who have ASD/AD are predisposed to criminal violence. At the conclusion, you should, as a physician without special training in autism, have a better understanding of when to suspect ASD/AD in an adult who is involved in criminal behavior.

When should you suspect ASD/AD in an adult?

Although autism is a childhood-onset disorder, its symptoms persist across the life

span. If the diagnosis is missed in childhood, which is likely to happen if the person has normal intelligence and relatively good verbal skills, he (she) might come to medical attention for the first time as an adult.

Because most psychiatrists who treat adults do not receive adequate training in the assessment of childhood psychiatric disorders, ASD/AD might be misdiagnosed as schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder. What clues help identify underlying ASD/AD when a patient is referred to you for psychiatric evaluation after allegedly committing a violent crime?

Clue #1. He makes no attempt to deny or conceal the act. The behavior appears to be part of ritualistic behavior or excessive interest (Table).

Often, the alleged crime occurs when the patient’s excessive interests “get out of control,” perhaps because of an external event. For example, a teenager with AD who is fixated on video games might stumble upon pornographic web sites and begin making obscene telephone calls. Particular attention should be paid to a history of rigid, restricted interests beginning in early childhood.

These restricted interests change over time and correlate with intelligence level: The higher the level of intelligence, the more sophisticated the level of fixation. Examples of fixations include computers, technology, and scientific experiments and pursuits. Repeated acts of arson have been reported to be part of an autistic person’s fixation with starting fires.8

Clue #2. He appears to lack sound and prudent judgment despite normal intelligence.

Although most patients with ASD score in the intellectually disabled or mentally retarded range, at least one-third have an IQ in the normal range.9 Examine school records and reports from other agencies when evaluating a patient. Pay attention to a history of difficulty relating to peers at an early age, combined with evidence of rigid, restricted fixations and interests.

It is important to obtain a reliable history going back to early childhood, and not rely just on the patient’s mental status; presenting symptoms might mask underlying traits of ASD, especially in higher-functioning adults. (I once cared for a young man with ASD who had been fired a few days after landing his first job selling used cars because he was “sexually harassing” his colleagues. When questioned, he said that he was only trying to be “friendly” and “practicing his social skills.”)

Clue #3. He has been given a diagnosis of schizophrenia without a clear history of hallucinations or delusions.

Differentiating chronic schizophrenia and autism in adults is not always easy, especially in those who have an intellectual disability. In patients whose cognitive and verbal skills are relatively well preserved (such as AD), the presence of intense, focused interests, a pedantic manner of speaking, and abnormalities of nonverbal communication can help clarify the diagnosis. In particular, a recorded history of “childhood schizophrenia” or “obsessive-compulsive behavior” going back to preschool years should alert you to possible ASD.

Scales and screens. Apart from obtaining an accurate developmental history from a variety of sources, you can use rating scales and screening instruments, such as the Social and Communication Questionnaire10—although their utility is limited in adults. It is important not to risk overdiagnosis on the basis of these instruments alone: The gold standard of diagnosis remains clinical. The critical point is that the combination of core symptoms of social communication deficits and restricted interests is more important than the presence of a single symptom. A touch of oddity does not mean that one has ASD/AD.

Is the prevalence of violent crime increased in ASD/AD?

It is important to distinguish violent crime from aggressive behavior. The latter, which can be verbal or nonverbal, is not always intentional or malevolent. In some persons who have an intellectual disability, a desire to communicate might lead to inappropriate touching or pushing. This distinction is particularly relevant to psychiatrists because many people who have ASD have an intellectual disability.

Violent crime is more deliberate, serious, and planned. It involves force or threat of force. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation Uniform Crime Reporting Program, violent crime comprises four offenses: murder and non-negligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault.11

Earlier descriptions of ASD/AD did not mention criminal violence as an important feature of these disorders. However, reports began to emerge about two decades ago suggesting that people who have ASD—particularly AD—are prone to violent crime. Some of the patients described in Wing’s original series12 of AD showed violent tendencies, ranging from sudden outbursts of violence to injury to others because of fixation on hobbies such as chemistry experimentation.

Reports such as these were based on isolated case reports or select samples, such as residents of maximum-security hospitals. Scragg and Shah, for example, surveyed the male population of Broadmoor Hospital, a high-security facility in the United Kingdom, and found that the prevalence of AD was higher than expected in the general population.13

Recent reports have not been able to confirm that violent crime is increased in persons with ASD, however:

- In a clinical sample of 313 Danish adults with ASD (age 25 to 59) drawn from the Danish Register of Criminality, Mouridsen and colleagues found that persons with ASD had a lower rate of criminal conviction than matched controls (9%, compared with 18%).14

- In a small community study, Woodbury-Smith and colleagues examined the prevalence rates and types of offending behavior in persons with ASD. Based on official records, only two (18%) had a history of criminal conviction.15

The role of psychiatric comorbidity

Psychiatric disorders are common in persons who have ASD. In one study, 70% of a sample of 114 children with ASD (age 10 to 14) had a psychiatric disorder, based on a parent interview.16 Although people with mental illness are not inherently criminal or violent, having an additional psychiatric disorder independently increases the risk of offending behavior.17 For example, the association of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with criminality is well established.16 Some patients with severe depression and psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia, also are at increased risk of committing a violent act.

To examine the contribution of mental health factors to the commission of crime by persons with ASD, Newman and Ghaziuddin18 used online databases to identify relevant articles, which were then cross-referenced with keyword searches for “violence,” “crime,” “murder,” “assault,” “rape,” and “sex offenses.” Thirty-seven cases were identified in the 17 publications that met inclusion criteria. Out of these, 30% had a definite psychiatric disorder and 54% had a probable psychiatric disorder at the time they committed the crime.18

Any patient with ASD/AD who is evaluated for criminal behavior should be screened for a comorbid psychiatric disorder. In adolescents, stressors such as bullying in school and problems surrounding dating might contribute to offending behavior.

What are management options in the face of violence?

Managing ASD/AD when an offending behavior has occurred first requires a correct diagnosis.19 Professionals working in the criminal justice system have little awareness of the variants of ASD; a defendant with an intellectual disability and a characteristic facial appearance (for example, someone with Down syndrome) can be easily identified, but a high-functioning person who has mild autistic features often is missed. This is more likely to occur in adults because the symptoms of ASD, including the type and severity of isolated interests, change over time.

Here is how I recommend that you proceed:

Step #1. Confirm the ASD diagnosis based on developmental history and the presence of persistent social and communication deficits plus restricted interests.

Step #2. Screen for comorbid psychiatric and medical disorders, including depression, psychosis, and seizure disorder.

Step #3. Treat any disorders you identify with a combination of medication and behavioral intervention.

Step #4. Carefully examine the circumstances surrounding the offending behavior. Involve forensic services on a case-by-case basis, depending on the type and seriousness of the offending behavior (see Related Resources for information on the role of forensic services). When the crime does not involve serious violence, lengthy incarceration might be unnecessary. Because psychopathy and ASD/AD are not mutually exclusive, persons who commit a heinous crime, such as rape or murder, should be dealt with in accordance with the law.

Need for greater awareness of the complexion of ASD

Patients who have ASD/AD form a heterogeneous group in which the levels of cognitive and communication skills are variable. Those who are low-functioning and who have severe behavioral and adaptive deficits occasionally commit aggressive acts against their caregivers.

Most patients with ASD/AD are neither violent nor criminal. Those who are at the higher end of the spectrum, with relatively preserved communication and intellectual skills, occasionally indulge in criminal behavior—behavior that is nonviolent and results from their inability to read social cues or excessive preoccupations.

Most reports that link criminal violence with ASD are based on isolated case reports or on biased samples that use unreliable diagnostic criteria. In higher-functioning persons with ASD, violent crime is almost always precipitated by a comorbid psychiatric disorder, such as severe depression and psychosis.

In short: There is a need to increase our awareness of the special challenges faced by persons with ASD/AD in the criminal justice system.

aGiven the term pervasive developmental disorders (PDD) in the DSM-IV-TR, the spectrum includes autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified.2

Bottom Line

Most people who have an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) do not commit violent crime. When violent crime occurs at the hands of a person with ASD, it is almost always precipitated by a comorbid psychiatric disorder, such as severe depression or psychosis. Treating a person with ASD who has committed a violent crime is multimodal, including forensic services when necessary.

Related Resources

- Autism Speaks. No link between autism and violence. www.autismspeaks.org/science/science-news/no-link-between-autism-and-violence.

- Haskins BG, Silva JA. Asperger’s disorder and criminal behavior: Forensic-psychiatric considerations. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2006;34(3):374-384.

- Newman SS, Ghaziuddin M. Violent crime and Asperger syndrome: the role of psychiatric comorbidity. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38:1848-1852.

- Wing L. Asperger’s syndrome: a clinical account. Psychol Med. 1981;11(1):115-129.

Disclosure

Dr. Ghaziuddin reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nerv Child. 1943;2:217-250.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2008 Principal Investigators. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders--Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 14 sites, United States, 2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012;61(3):1-19.

4. Asperger H. Die autistichen psychopathen im kindesalter. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr. 1944;117:76-136.

5. Happe F. Criteria, categories, and continua: autism and related disorders in DSM-5. J Am Acad Child and Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:540-542.

6. Walkup JT, Rubin DH. Social withdrawal and violence. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:399-401.

7. Hippler K, Vidding E, Klicpera C, et al. Brief report: no increase in criminal convictions in Asperger’s original cohort. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40:774-780.

8. Siponmaa L, Kristiansson M, Jonson C, et al. Juvenile and young adult mentally disordered offenders: the role of child neuropsychiatric disorders. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2001;29(4):420-426.

9. Matson JL, Shoemaker M. Intellectual disability and its relationship to autism spectrum disorders. Res Dev Disabil. 2009;30(6):1107-1114.

10. Rutter M, Bailey A, Lord C. Social communication questionnaire. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2003.

11. US Department of Justice. Violent crime. http://www2.fbi.gov/ucr/cius2009/offenses/violent_crime. Published September, 2010. Accessed April 26, 2013.

12. Wing L. Asperger’s syndrome: a clinical account. Psychol Med. 1981;11(1):115-129.

13. Scragg P, Shah A. The prevalence of Asperger’s syndrome in a secure hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;165:67-72.

14. Mouridsen SE, Rich B, Isager T, et al. Pervasive developmental disorders and criminal behaviour: a case control study. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2008; 52(2):196-205.

15. Woodbury-Smith MR, Clare ICH, Holland AJ, et al. High functioning autistic spectrum disorders, offending and other law-breaking: findings from a community sample. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol. 2006;17(1):108-120.

16. Simonoff E, Pickles A, Charman T, et al. Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(8):

921-929.

17. Ghaziuddin M. Mental health aspects of autism and Asperger syndrome. London, United Kingdom: Jessica Kingsley Press; 2005.

18. Newman SS, Ghaziuddin M. Violent crime and Asperger syndrome: the role of psychiatric comorbidity. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38:1848-1852.

19. Wing L. Asperger’s syndrome: management requires diagnosis. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry. 1997;8(2):253-257.

1. Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nerv Child. 1943;2:217-250.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2008 Principal Investigators. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders--Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 14 sites, United States, 2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012;61(3):1-19.

4. Asperger H. Die autistichen psychopathen im kindesalter. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr. 1944;117:76-136.

5. Happe F. Criteria, categories, and continua: autism and related disorders in DSM-5. J Am Acad Child and Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:540-542.

6. Walkup JT, Rubin DH. Social withdrawal and violence. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:399-401.

7. Hippler K, Vidding E, Klicpera C, et al. Brief report: no increase in criminal convictions in Asperger’s original cohort. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40:774-780.

8. Siponmaa L, Kristiansson M, Jonson C, et al. Juvenile and young adult mentally disordered offenders: the role of child neuropsychiatric disorders. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2001;29(4):420-426.

9. Matson JL, Shoemaker M. Intellectual disability and its relationship to autism spectrum disorders. Res Dev Disabil. 2009;30(6):1107-1114.

10. Rutter M, Bailey A, Lord C. Social communication questionnaire. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2003.

11. US Department of Justice. Violent crime. http://www2.fbi.gov/ucr/cius2009/offenses/violent_crime. Published September, 2010. Accessed April 26, 2013.

12. Wing L. Asperger’s syndrome: a clinical account. Psychol Med. 1981;11(1):115-129.

13. Scragg P, Shah A. The prevalence of Asperger’s syndrome in a secure hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;165:67-72.

14. Mouridsen SE, Rich B, Isager T, et al. Pervasive developmental disorders and criminal behaviour: a case control study. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2008; 52(2):196-205.

15. Woodbury-Smith MR, Clare ICH, Holland AJ, et al. High functioning autistic spectrum disorders, offending and other law-breaking: findings from a community sample. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol. 2006;17(1):108-120.

16. Simonoff E, Pickles A, Charman T, et al. Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(8):

921-929.

17. Ghaziuddin M. Mental health aspects of autism and Asperger syndrome. London, United Kingdom: Jessica Kingsley Press; 2005.

18. Newman SS, Ghaziuddin M. Violent crime and Asperger syndrome: the role of psychiatric comorbidity. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38:1848-1852.

19. Wing L. Asperger’s syndrome: management requires diagnosis. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry. 1997;8(2):253-257.

Problematic pruritus: Seeking a cure for psychogenic itch

Psychogenic itch—an excessive impulse to scratch, gouge, or pick at skin in the absence of dermatologic cause—is common among psychiatric inpatients, but can be challenging to assess and manage in outpatients. Patients with psychogenic itch predominantly are female, with average age of onset between 30 and 45 years.1 Psychiatric disorders associated with psychogenic itch include depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety, somatoform disorders, mania, psychosis, and substance abuse.2 Body dysmorphic disorder, trichotillomania, kleptomania, and borderline personality disorder may be comorbid in patients with psychogenic itch.3

Characteristics of psychogenic itch

Consider psychogenic itch in patients who have recurring physical symptoms and demand examination despite repeated negative results. Other indicators include psychological factors—loss of a loved one, unemployment, relocation, etc.—that may be associated with onset, severity, elicitation, or maintenance of the itching; impairments in the patient’s social or professional life; and marked preoccupation with itching or the state of her (his) skin. Characteristically, itching can be provoked by emotional triggers, most notably during stages of excitement, and also by mechanical or chemical stimuli.

Skin changes associated with psychogenic itch often are found on areas accessible to the patient’s hand: face, arms, legs, abdomen, thighs, upper back, and shoulders. These changes can be seen in varying stages, from discrete superficial excoriations, erosions, and ulcers to thick, darkened nodules and colorless atrophic scars. Patients often complain of burning. In some cases, a patient uses a tool or instrument to autoaggressively manipulate his (her) skin in response to tingling or stabbing sensations. Artificial lesions or eczemas brought on by self-

manipulation can occur. Stress, life changes, or inhibited rage may be evoking the burning sensation and subsequent complaints.

Interventions to consider

After you have ruled out other causes of pruritus and made a diagnosis of psychogenic itch, educate your patient about the multifactorial etiology. Explain possible associations between skin disorders and unconscious reaction patterns, and the role of emotional and cognitive stimuli.

Moisturizing the skin can help the dryness associated with repetitive scratching. Consider prescribing an antihistamine, moisturizer, topical steroid, antibiotic, or

occlusive dressing.

Some pharmacological properties of antidepressants that are not related to their antidepressant activity—eg, the histamine-1 blocking effect of tricyclic antidepressants—are beneficial for treating psychogenic itch.4 Sedating antihistamines (hydroxyzine) and antidepressants (doxepin) may help break cycles of itching and depression or itching and scratching.4 Tricyclic antidepressants also are recommended for treating burning, stabbing, or tingling sensations.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Yosipovitch G, Samuel LS. Neuropathic and psychogenic itch. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21(1):32-41.

2. Krishnan A, Koo J. Psyche, opioids, and itch: therapeutic consequences. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18(4):314-322.

3. Arnold LM, Auchenbach MB, McElroy SL. Psychogenic excoriation. Clinical features, proposed diagnostic criteria, epidemiology and approaches to treatment. CNS Drugs. 2001;15(5):351-359.

4. Gupta MA, Guptat AK. The use of antidepressant drugs in dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15(6):512-518.

Psychogenic itch—an excessive impulse to scratch, gouge, or pick at skin in the absence of dermatologic cause—is common among psychiatric inpatients, but can be challenging to assess and manage in outpatients. Patients with psychogenic itch predominantly are female, with average age of onset between 30 and 45 years.1 Psychiatric disorders associated with psychogenic itch include depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety, somatoform disorders, mania, psychosis, and substance abuse.2 Body dysmorphic disorder, trichotillomania, kleptomania, and borderline personality disorder may be comorbid in patients with psychogenic itch.3

Characteristics of psychogenic itch

Consider psychogenic itch in patients who have recurring physical symptoms and demand examination despite repeated negative results. Other indicators include psychological factors—loss of a loved one, unemployment, relocation, etc.—that may be associated with onset, severity, elicitation, or maintenance of the itching; impairments in the patient’s social or professional life; and marked preoccupation with itching or the state of her (his) skin. Characteristically, itching can be provoked by emotional triggers, most notably during stages of excitement, and also by mechanical or chemical stimuli.

Skin changes associated with psychogenic itch often are found on areas accessible to the patient’s hand: face, arms, legs, abdomen, thighs, upper back, and shoulders. These changes can be seen in varying stages, from discrete superficial excoriations, erosions, and ulcers to thick, darkened nodules and colorless atrophic scars. Patients often complain of burning. In some cases, a patient uses a tool or instrument to autoaggressively manipulate his (her) skin in response to tingling or stabbing sensations. Artificial lesions or eczemas brought on by self-

manipulation can occur. Stress, life changes, or inhibited rage may be evoking the burning sensation and subsequent complaints.

Interventions to consider

After you have ruled out other causes of pruritus and made a diagnosis of psychogenic itch, educate your patient about the multifactorial etiology. Explain possible associations between skin disorders and unconscious reaction patterns, and the role of emotional and cognitive stimuli.

Moisturizing the skin can help the dryness associated with repetitive scratching. Consider prescribing an antihistamine, moisturizer, topical steroid, antibiotic, or

occlusive dressing.

Some pharmacological properties of antidepressants that are not related to their antidepressant activity—eg, the histamine-1 blocking effect of tricyclic antidepressants—are beneficial for treating psychogenic itch.4 Sedating antihistamines (hydroxyzine) and antidepressants (doxepin) may help break cycles of itching and depression or itching and scratching.4 Tricyclic antidepressants also are recommended for treating burning, stabbing, or tingling sensations.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Psychogenic itch—an excessive impulse to scratch, gouge, or pick at skin in the absence of dermatologic cause—is common among psychiatric inpatients, but can be challenging to assess and manage in outpatients. Patients with psychogenic itch predominantly are female, with average age of onset between 30 and 45 years.1 Psychiatric disorders associated with psychogenic itch include depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety, somatoform disorders, mania, psychosis, and substance abuse.2 Body dysmorphic disorder, trichotillomania, kleptomania, and borderline personality disorder may be comorbid in patients with psychogenic itch.3

Characteristics of psychogenic itch

Consider psychogenic itch in patients who have recurring physical symptoms and demand examination despite repeated negative results. Other indicators include psychological factors—loss of a loved one, unemployment, relocation, etc.—that may be associated with onset, severity, elicitation, or maintenance of the itching; impairments in the patient’s social or professional life; and marked preoccupation with itching or the state of her (his) skin. Characteristically, itching can be provoked by emotional triggers, most notably during stages of excitement, and also by mechanical or chemical stimuli.

Skin changes associated with psychogenic itch often are found on areas accessible to the patient’s hand: face, arms, legs, abdomen, thighs, upper back, and shoulders. These changes can be seen in varying stages, from discrete superficial excoriations, erosions, and ulcers to thick, darkened nodules and colorless atrophic scars. Patients often complain of burning. In some cases, a patient uses a tool or instrument to autoaggressively manipulate his (her) skin in response to tingling or stabbing sensations. Artificial lesions or eczemas brought on by self-

manipulation can occur. Stress, life changes, or inhibited rage may be evoking the burning sensation and subsequent complaints.

Interventions to consider

After you have ruled out other causes of pruritus and made a diagnosis of psychogenic itch, educate your patient about the multifactorial etiology. Explain possible associations between skin disorders and unconscious reaction patterns, and the role of emotional and cognitive stimuli.

Moisturizing the skin can help the dryness associated with repetitive scratching. Consider prescribing an antihistamine, moisturizer, topical steroid, antibiotic, or

occlusive dressing.

Some pharmacological properties of antidepressants that are not related to their antidepressant activity—eg, the histamine-1 blocking effect of tricyclic antidepressants—are beneficial for treating psychogenic itch.4 Sedating antihistamines (hydroxyzine) and antidepressants (doxepin) may help break cycles of itching and depression or itching and scratching.4 Tricyclic antidepressants also are recommended for treating burning, stabbing, or tingling sensations.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Yosipovitch G, Samuel LS. Neuropathic and psychogenic itch. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21(1):32-41.

2. Krishnan A, Koo J. Psyche, opioids, and itch: therapeutic consequences. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18(4):314-322.

3. Arnold LM, Auchenbach MB, McElroy SL. Psychogenic excoriation. Clinical features, proposed diagnostic criteria, epidemiology and approaches to treatment. CNS Drugs. 2001;15(5):351-359.

4. Gupta MA, Guptat AK. The use of antidepressant drugs in dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15(6):512-518.

1. Yosipovitch G, Samuel LS. Neuropathic and psychogenic itch. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21(1):32-41.

2. Krishnan A, Koo J. Psyche, opioids, and itch: therapeutic consequences. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18(4):314-322.

3. Arnold LM, Auchenbach MB, McElroy SL. Psychogenic excoriation. Clinical features, proposed diagnostic criteria, epidemiology and approaches to treatment. CNS Drugs. 2001;15(5):351-359.

4. Gupta MA, Guptat AK. The use of antidepressant drugs in dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15(6):512-518.

Managing geriatric bipolar disorder

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“I just saw Big Bird. He was 100 feet tall!” Malingering in the emergency room

The economic downturn in the United States has prompted numerous state and county budget cuts, in turn forcing many patients to receive their mental health care in the emergency room (ER). Most patients evaluated in the ER for mental health-related reasons have a legitimate psychiatric crisis—but that isn’t always the case. And as the number of people seeking care in the ER has increased, it appears that so too has the number of those who feign symptoms for secondary gain—that is, who are malingering.

This article highlights several red flags for malingered behavior; emphasizes typical (compared with atypical) symptoms of psychosis; and provides an overview of four instruments that you can use to help assess for malingering in the ED.

A difficult diagnosis

No single factor is indicative of malingering, and no objective tests exist to diagnose malingering definitively. Rather, the tests we discuss provide additional information that can help formulate a clinical impression.

According to DSM-5, malingering is “…the intentional production of false or grossly exaggerated physical or psychological symptoms, motivated by external incentives…”1 Despite a relatively straightforward definition, the diagnosis is difficult to make because it is a diagnosis of exclusion.

Even with sufficient evidence, many clinicians are reluctant to diagnose malingering because they fear retaliation and diagnostic uncertainty. Psychiatrists also might be reluctant to diagnose malingering because the negative connotation that the label carries risks stigmatizing a patient who might, in fact, be suffering. This is true especially when there is suspicion of partial malingering, the conscious exaggeration of existing symptoms.

Despite physicians’ reluctance to diagnose malingering, it is a real problem, especially in the ER. Research suggests that as many as 13% of patients in the ER feign illness, and that their secondary gain most often includes food, shelter, prescription drugs, financial gain, and avoidance of jail, work, or family responsibilities.2

CASE REPORT ‘The voices are telling me to kill myself’

Mr. K, a 36-year-old white man, walks into the ER on a late December day. He tells the triage nurse that he suicidal; she escorts him to the psychiatric pod of the ER. Nursing staff provide line-of-sight care, monitor his vital signs, and draw blood for testing.

Within hours, Mr. K is deemed “medically cleared” and ready for assessment by the psychiatric social worker.

Interview and assessment. During the interview with the social worker, Mr. K reports that he has been depressed, adamantly maintaining that he is suicidal, with a plan to “walk in traffic” or “eat the end of a gun.” The social worker places him on a 72-hour involuntary psychiatric hold. ER physicians order psychiatric consultation.

Mr. K is well-known to the psychiatrist on call, from prior ER visits and psychiatric hospital admissions. In fact, two days earlier, he put a psychiatric nurse in a headlock while being escorted from the psychiatric inpatient unit under protest.

On assessment by the psychiatrist, Mr. K continues to endorse feeling suicidal; he adds: “If I don’t get some help, I’m gonna kill somebody else!”

Without prompting, the patient states that “the voices are telling me to kill myself.” He says that those voices have been relentless since he left the hospital two days earlier. According to Mr. K, nothing he did helped quiet the voices, although previous prescriptions for quetiapine have been helpful.

Mr. K says that he is unable to recall the clinic or name of his prior psychiatrist. He claims that he was hospitalized four months ago, (despite the psychiatrist’s knowledge that he had been discharged two days ago) and estimates that his psychotic symptoms began one year ago. He explains that he is homeless and does not have social support. He is unable to provide a telephone number or a name to contact family for collateral information.

Mental status exam. The mental status examination reveals a tall, thin, disheveled man who has poor dentition. He is now calm and cooperative despite his reported level of distress. His speech is unremarkable and his eye contact is appropriate. His thought process is linear, organized, and coherent.

Mr. K does not endorse additional symptoms, but is quick to agree with the psychiatrist’s follow-up questions about hallucinations: “Yeah! I’ve been seeing all kinds of crazy stuff.” When prompted for details, he says, “I just saw Big Bird… He was 100 feet tall!”

Lab testing. Mr. K’s blood work is remarkable for positive urine toxicology for amphetamines.

Nursing notes indicate that Mr. K slept overnight and ate 100% of the food on his dinner and breakfast trays.

Red flags flying

Mr. K’s case highlights several red flags that should raise suspicion of malingering (Table 1)3,4:

- A conditional statement by which a patient threatens to harm himself or others, contingent upon a demand—for example, “If I don’t get A, I’ll do B.”

- An overly dramatic presentation, in which the patient is quick to endorse

distressing symptoms. Consider Mr. K: He was quick to report that he saw Big Bird, and that this Sesame Street character “was 100 feet tall.” Patients who have been experiencing true psychotic symptoms might be reluctant to speak of their distressing symptoms, especially if they have not experienced such symptoms in the past (the first psychotic break). Mr. K, however, volunteered and called attention to particularly dramatic psychotic symptoms. - A subjective report of distress that is inconsistent with the objective presentation. Mr. K’s report of depression—a diagnosis that typically includes insomnia and poor appetite—was inconsistent with his behavior: He slept and he ate all of his meals.

Atypical (vs typical) psychosis

Malingering can occur in various arenas and take many different forms. In forensic settings, such as prison, malingered conditions more often present as posttraumatic stress disorder or cognitive impairment.5 In non-forensic settings, such as the ER, the most commonly malingered conditions include suicidality and psychosis.

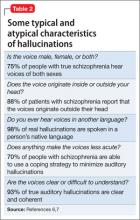

To detect malingered psychosis, one must first understand how true psychotic symptoms manifest. The following discussion describes and compares typical and atypical symptoms of psychosis; examples are given in Table 2.6,7No single atypical psychotic symptom is indicative of malingering. Rather, a collection of atypical symptoms, when considered in clinical context, should raise suspicion of malingering and prompt you to seek additional collateral information or perform appropriate testing for malingering.

Hallucinations

Typically, hallucinations take three forms: auditory, visual, and tactile. In primary psychiatric conditions, auditory hallucinations are the most common of those three.

Tactile hallucinations can be present during episodes of substance intoxication or withdrawal (eg, so-called coke bugs).

Auditory hallucinations. Patients who malinger psychosis are often unaware of the nuances of hallucinations. For example, they might report the atypical symptom of continuous voices; in fact, most patients who have schizophrenia hear voices intermittently. Keep in mind, too, that 75% of patients who have schizophrenia hear male and female voices, and that 70% have some type of coping strategy to minimize their internal stimuli (eg, listening to music).6,7

Visual hallucinations are most often associated with neurologic disease, but also occur often in primary psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia.

Patients who malinger psychotic symptoms often are open to suggestion, and are quick to endorse visual hallucinations. When asked to describe their hallucinations, however, they often respond without details (“I don’t know”). Other times, they overcompensate with wild exaggeration of atypical visions—recall Mr. K’s description of a towering Big Bird. Asked if the visions are in black and white, they might eagerly agree. Research suggests, however, that patients who have schizophrenia more often experience life-sized hallucinations of vivid scenes with family members, religious figures, or animals.8 Furthermore, genuine visual hallucinations typically are in color.

Putting malingering in the differential

Regardless of the number of atypical symptoms a patient exhibits, malingering will be missed if you do not include it in the differential diagnosis. This fact was made evident in a 1973 study.9

In that study, Rosenhan and seven of his colleagues—a psychology graduate student, three psychologists, a pediatrician, a psychiatrist, a painter, and a housewife—presented to various ERs and intake units, and, as they had been instructed, endorsed vague auditory hallucinations of “empty,” “hollow,” or “thud” sounds—but nothing more. All were admitted to psychiatric hospitals. Once admitted, they refrained (again, as instructed) from endorsing or exhibiting any psychotic symptoms.

Despite the vague nature of the reported auditory hallucinations and how rapidly symptoms resolved on admission, seven of these pseudo-patients were given a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and one was given a diagnosis of manic-depressive psychosis. Duration of admission ranged from 7 to 52 days (average, 19 days). None of the study participants were suspected of feigning symptoms.

It’s fortunate that, since then, mental health professionals have developed more structured techniques of assessment to detect malingering in inpatient and triage settings.

Testing to identify and assess malingering

The ER is a fast-paced environment, in which treatment teams are challenged to make rapid clinical assessments. With the overwhelming number of patients seeking mental health care in the ER, however, overall wait times are increasing; in some regions, it is common to write, then to rewrite, involuntary psychiatric holds for patients awaiting transfer to a psychiatric hospital. This extended duration presents an opportunity to serially evaluate patients suspected of malingering.

Even in environments that allow for a more comprehensive evaluation (eg, jail or inpatient psychiatric wards), few psychometric tests have been validated to detect malingering. The most validated tests include the Structured Interview of Reported Symptoms (SIRS), distributed now as the Structured Interview of Reported Symptoms, 2nd edition (SIRS-2), and the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory Revised (MMPI-2). These tests typically require ≥30 minutes to administer and generally are not feasible in the fast-paced ER.

Despite the high prevalence of malingered behaviors in the ER, no single test has been validated in such a setting. Furthermore, there is no test designed to specifically assess for malingered suicidality or homicidality. The results of one test do not, in isolation, represent a comprehensive neuropsychological examination; rather, those results provide additional data to formulate a clinical impression. The instruments discussed below are administered and scored in a defined, objective manner.

When evaluating a patient whom you suspect of malingering, gathering collateral information—from family members, friends, nurses, social workers, emergency medicine physicians, and others—becomes important. You might discover pertinent information in ambulance and police reports and a review of the patient’s prior ER visits.

During the initial interview, ask open-ended questions; do not lead the patient by listing clusters of symptoms associated with a particular diagnosis. Because it is often difficult for a patient to malinger symptoms for a prolonged period, serial observations of a patient’s behavior and interview responses over time can provide additional information to make a clinical diagnosis of malingering.4

What testing is feasible in the ER?

Miller Forensic Assessment of Symptoms Test. The M-FAST measures rare symptom combinations, excessive reporting, and atypical symptoms of psychosis, using the same principles as the SIRS-2.

The 25-item screen begins by advising the examinee that he (she) will be asked questions about his psychological symptoms and that the questions that follow might or might not apply to his specific symptoms.

After that brief introduction, the examinee is asked if he hears ringing in his ears. Based on his response, the examiner reads one of two responses—both of which suggest the false notion that patients with true mental illness will suffer from ringing in their ears.

The examinee is then asked a series of Yes or No questions. Some pertain to legitimate symptoms a person with a psychotic illness might suffer (such as, “Do voices tell you to do things? Yes or No?”). Conversely, other questions screen for improbable symptoms that are atypical of patients who have a true psychotic disorder (such as “On many days I feel so bad that I can’t even remember my full name: Yes or No?”).

The exam concludes with a question about a ringing in the examinee’s ear. Affirmative responses are tallied; a score of ≥6 in a clinical setting is 83% specific and 93% sensitive for malingering.10

Visual Memory Test. Rey’s 15-Item Visual Memory Test capitalizes on the false belief that intellectual deficits, in addition to psychotic symptoms, make a claim of mental illness more believable.

In this simple test, the provider tells the examinee, “I am going to show you a card with 15 things on it that I want you to remember. When I take the card away, I want you to write down as many of the 15 things as you can remember.”3 The examinee is shown 15 common symbols (eg, 1, 2, 3; A, B, C; I, II, III, a, b, c; and the geometrics ●, ■, ▲).

At 5 seconds, the examinee is prompted, “Be sure to remember all of them.” After 10 seconds, the stimulus is removed, and the examinee is asked to recreate the figure.

Normative data indicate that even a patient who has a severe traumatic brain injury is able to recreate at least eight of the symbols. Although controversial, research indicates that a score of <9 symbols is predictive of malingering with 40% sensitivity and 100% specificity.11

Critics argued that confounding variables (IQ, memory disorder, age) might skew the quantitative score. For that reason, the same group developed the Rey’s II Test, which includes a supplementary qualitative scoring system that emphasizes embellishment errors (eg, the wrong symbol) and ordering errors (eg, wrong row). The Rey’s II Test proved to be more sensitive (accurate classification of malingers): A cut-off score of ≥2 qualitative errors is predictive of malingering with 86% sensitivity and 100% specificity.12

Coin-in-the-Hand Test. Perhaps the simplest test to administer is the Coin-in-the-Hand, designed to seem—superficially—to be a challenging memory test.

The patient must guess in which hand the examiner is holding a coin. The patient is shown the coin for two seconds, and then asked to close his eyes and count back from 10. The patient then points to one of the two clenched hands.