User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Alternatives to 12-step groups

Persons addicted to drugs often are among the most marginalized psychiatric patients, but are in need of the most support.1 Many of these patients have comorbid medical and psychiatric problems, including difficult-to-treat pathologies that may have developed because of a traumatic experience or an attachment disorder that dominates their emotional lives.2 These patients value clinicians who engage them in an open, nonjudgmental, and empathetic way.

Eliciting a patient’s reasons for change and introducing him (her) to a variety of peer-led recovery group options that complement and support psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy can be valuable. Although most clinicians are aware of the traditional 12-step group model that embraces spirituality, many might know less about other groups that can play an instrumental role in engaging patients and placing them on the path to recovery.

SMART (Self-Management and Recovery Training) Recovery5 is a nonprofit organization that does not employ the 12-step model; instead, it uses evidence-based, non-confrontational, motivational, behavioral, and cognitive approaches to achieve abstinence.

Women for Sobriety6 helps women achieve abstinence.

LifeRing Secular Recovery7 works on empowering the “sober self” through groups that de-emphasize drug and alcohol use in personal histories.

Rational Recovery8 uses the Addictive Voice Recognition Technique to empower people overcoming addictions. This technique trains individuals to recognize the “addictive voice.” It does not support the theory of continuous recovery, or even recovery groups, but enables the user to achieve sobriety independently. This program greatly limits interaction between people overcoming addiction and physicians and counselors—save for periods of serious withdrawal.

The Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA)9 is an evidence-based program that focuses primarily on environmental and social factors influencing sobriety. This behavioral approach emphasizes the role of contingencies that can encourage or discourage sobriety. CRA has been studied in outpatients—predominantly homeless persons—and inpatients, and in a range of abused substances.

Click here for another Pearl on familiarizing yourself with Alcoholics Anonymous dictums.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Kreek MJ. Extreme marginalization: addiction and other mental health disorders, stigma, and imprisonment. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1231:65-72.

2. Wu NS, Schairer LC, Dellor E, et al. Childhood trauma and health outcomes in adults with comorbid substance abuse and mental health disorders. Addict Behav. 2010;35(1):68-71.

3. Moderation Management. http://www.moderation.org. Accessed April 12, 2013.

4. Moderation Management. What is moderation management? http://www.moderation.org/whatisMM.shtml. Accessed August 6, 2013.

5. SMART (Self Management and Recovery Training) Recovery. http://www.smartrecovery.org. Accessed April 12, 2013.

6. Women for Sobriety. http://www.womenforsobriety.org. Accessed April 12, 2013.

7. LifeRing. http://lifering.org. Accessed April 12, 2013.

8. Rational Recovery. http://www.rational.org. Published October 25, 1995. Accessed April 12, 2013.

9. Miller WR, Meyers RJ, Hiller-Sturmhofel S. The community-reinforcement approach. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh23-2/116-121.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2013.

Persons addicted to drugs often are among the most marginalized psychiatric patients, but are in need of the most support.1 Many of these patients have comorbid medical and psychiatric problems, including difficult-to-treat pathologies that may have developed because of a traumatic experience or an attachment disorder that dominates their emotional lives.2 These patients value clinicians who engage them in an open, nonjudgmental, and empathetic way.

Eliciting a patient’s reasons for change and introducing him (her) to a variety of peer-led recovery group options that complement and support psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy can be valuable. Although most clinicians are aware of the traditional 12-step group model that embraces spirituality, many might know less about other groups that can play an instrumental role in engaging patients and placing them on the path to recovery.

SMART (Self-Management and Recovery Training) Recovery5 is a nonprofit organization that does not employ the 12-step model; instead, it uses evidence-based, non-confrontational, motivational, behavioral, and cognitive approaches to achieve abstinence.

Women for Sobriety6 helps women achieve abstinence.

LifeRing Secular Recovery7 works on empowering the “sober self” through groups that de-emphasize drug and alcohol use in personal histories.

Rational Recovery8 uses the Addictive Voice Recognition Technique to empower people overcoming addictions. This technique trains individuals to recognize the “addictive voice.” It does not support the theory of continuous recovery, or even recovery groups, but enables the user to achieve sobriety independently. This program greatly limits interaction between people overcoming addiction and physicians and counselors—save for periods of serious withdrawal.

The Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA)9 is an evidence-based program that focuses primarily on environmental and social factors influencing sobriety. This behavioral approach emphasizes the role of contingencies that can encourage or discourage sobriety. CRA has been studied in outpatients—predominantly homeless persons—and inpatients, and in a range of abused substances.

Click here for another Pearl on familiarizing yourself with Alcoholics Anonymous dictums.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Persons addicted to drugs often are among the most marginalized psychiatric patients, but are in need of the most support.1 Many of these patients have comorbid medical and psychiatric problems, including difficult-to-treat pathologies that may have developed because of a traumatic experience or an attachment disorder that dominates their emotional lives.2 These patients value clinicians who engage them in an open, nonjudgmental, and empathetic way.

Eliciting a patient’s reasons for change and introducing him (her) to a variety of peer-led recovery group options that complement and support psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy can be valuable. Although most clinicians are aware of the traditional 12-step group model that embraces spirituality, many might know less about other groups that can play an instrumental role in engaging patients and placing them on the path to recovery.

SMART (Self-Management and Recovery Training) Recovery5 is a nonprofit organization that does not employ the 12-step model; instead, it uses evidence-based, non-confrontational, motivational, behavioral, and cognitive approaches to achieve abstinence.

Women for Sobriety6 helps women achieve abstinence.

LifeRing Secular Recovery7 works on empowering the “sober self” through groups that de-emphasize drug and alcohol use in personal histories.

Rational Recovery8 uses the Addictive Voice Recognition Technique to empower people overcoming addictions. This technique trains individuals to recognize the “addictive voice.” It does not support the theory of continuous recovery, or even recovery groups, but enables the user to achieve sobriety independently. This program greatly limits interaction between people overcoming addiction and physicians and counselors—save for periods of serious withdrawal.

The Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA)9 is an evidence-based program that focuses primarily on environmental and social factors influencing sobriety. This behavioral approach emphasizes the role of contingencies that can encourage or discourage sobriety. CRA has been studied in outpatients—predominantly homeless persons—and inpatients, and in a range of abused substances.

Click here for another Pearl on familiarizing yourself with Alcoholics Anonymous dictums.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Kreek MJ. Extreme marginalization: addiction and other mental health disorders, stigma, and imprisonment. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1231:65-72.

2. Wu NS, Schairer LC, Dellor E, et al. Childhood trauma and health outcomes in adults with comorbid substance abuse and mental health disorders. Addict Behav. 2010;35(1):68-71.

3. Moderation Management. http://www.moderation.org. Accessed April 12, 2013.

4. Moderation Management. What is moderation management? http://www.moderation.org/whatisMM.shtml. Accessed August 6, 2013.

5. SMART (Self Management and Recovery Training) Recovery. http://www.smartrecovery.org. Accessed April 12, 2013.

6. Women for Sobriety. http://www.womenforsobriety.org. Accessed April 12, 2013.

7. LifeRing. http://lifering.org. Accessed April 12, 2013.

8. Rational Recovery. http://www.rational.org. Published October 25, 1995. Accessed April 12, 2013.

9. Miller WR, Meyers RJ, Hiller-Sturmhofel S. The community-reinforcement approach. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh23-2/116-121.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2013.

1. Kreek MJ. Extreme marginalization: addiction and other mental health disorders, stigma, and imprisonment. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1231:65-72.

2. Wu NS, Schairer LC, Dellor E, et al. Childhood trauma and health outcomes in adults with comorbid substance abuse and mental health disorders. Addict Behav. 2010;35(1):68-71.

3. Moderation Management. http://www.moderation.org. Accessed April 12, 2013.

4. Moderation Management. What is moderation management? http://www.moderation.org/whatisMM.shtml. Accessed August 6, 2013.

5. SMART (Self Management and Recovery Training) Recovery. http://www.smartrecovery.org. Accessed April 12, 2013.

6. Women for Sobriety. http://www.womenforsobriety.org. Accessed April 12, 2013.

7. LifeRing. http://lifering.org. Accessed April 12, 2013.

8. Rational Recovery. http://www.rational.org. Published October 25, 1995. Accessed April 12, 2013.

9. Miller WR, Meyers RJ, Hiller-Sturmhofel S. The community-reinforcement approach. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh23-2/116-121.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2013.

Obsessed with Facebook

CASE: Paranoid and online

Mr. M, age 22, is brought to the emergency department by family because they are concerned about his paranoia and increasing agitation related to Facebook posts by friends and siblings. At age 8, Mr. M was diagnosed with depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and anger management problems, which were well controlled with fluoxetine until last year, when he discontinued psychiatric follow-up. Mr. M’s girlfriend ended their relationship 1 month ago, although it is unclear whether the break-up was caused by his depressive symptoms or exacerbated them. In the last 2 days, his parents have noticed an increase in his delusional thoughts and aggressive behavior.

Family psychiatric history is not significant. Five years ago, Mr. M suffered a head injury in a motor vehicle collision, but completed high school without evidence of cognitive impairment or behavioral changes.

Mr. M appears disheveled and irritable. He reports his mood as “depressed,” but denies suicidal or homicidal ideations. He has no history of violence or antisocial behavior.

Mr. M is alert and oriented with clear speech, intact language, and grossly intact memory and concentration—although, he admits, “I just obsess over certain thoughts.” He endorses feelings of anxiety, insomnia, low energy, lack of sleep secondary to his paranoia, and claims that “something was said on Facebook about a girl and everyone is in on it.” He explains that his Facebook friends talk in “analogies” about him, and reports that, “I can just tell that’s what they are talking about even if they don’t say it directly.”

a) impulse control disorder

b) brief psychotic episode

c) psychotic depression

d) bipolar disorder

The authors’ observations

The last decade has seen a rise in the creation and use of social networking sites such as Facebook, Myspace, and Twitter. Facebook has 1.15 billion monthly active users.1 Seventy-five percent of teenagers own cell phones, and 25% report using their phones to access social media outlets.2 More than 50% of teenagers visit a social networking site daily, with 22% logging in to their favorite social media network more than 10 times a day.3 The easy accessibility of social media outlets has prompted study of the association of that accessibility with anxiety, depression, and self-esteem.3-7

Although not a DSM-5 or ICD-10 diagnosis, internet addiction has been correlated with depression.8 Similarly, O’Keefe and colleagues describe Facebook depression in teens who spend a large amount of time on social networking sites.4 The recently developed Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS)9 evaluates the six core elements of addiction (salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse) in Facebook users.

Facebook certainly provides a valuable mechanism for friends to stay connected in an increasingly global society, and has acknowledged the potential it has to address mental illness. In 2011, Facebook partnered with the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline to allow users to report observed suicidal content, thereby utilizing the online community to facilitate delivery of mental health resources.10,11

HISTORY: Sibling rivalry

Mr. M had a romantic relationship with “Ms. B” in high school that he describes as “on and off,” beginning during his sophomore year. He describes himself as a “quick learner” who is task-oriented. He says he was outgoing in high school but became more introverted during his last year there. After high school, Mr. M worked as an electrician and discontinued psychiatric follow-up because he “felt fine.” He lives at home with his parents, two older sisters, and twin brother, who he identifies as being a lifelong “rival.”

After Ms. B ended her relationship with Mr. M, he began to suspect that she had become romantically involved with his twin brother. After Mr. M observed his brother leaving the house one night, he confronted his twin, who denied any involvement with Ms. B. After his brother left, Mr. M became enraged and punched a wall, fracturing his hand.

Two weeks before admission, Mr. M became increasingly preoccupied with suspicions of his brother’s involvement with Ms. B and looked for evidence on Facebook. Mr. M intensely monitored his Facebook news feed, which constantly updates to show public posts made by a user’s Facebook friends. He interpreted his friends’ posts as either directly relating to him or to a new relationship between Ms. B and his twin brother, stating that his friends were “talking in analogies” rather than directly using names.

Mr. M’s Facebook use rapidly increased to 3 or more hours a day. He can access Facebook from his laptop or cell phone, and reports logging in more than 10 times throughout the day. He says that, on Facebook, “it’s easier to talk trash” because people can say things they would not normally say face to face. He also states that Facebook is “ruining personal relationships,” and that it is “so easy to be in touch with everyone without really being in touch.”

The authors’ observations

In Mr. M’s case, Facebook served as a vehicle through which he could pursue a non-bizarre delusion. Mr. M openly admitted to viewing his twin brother as a rival; it is not surprising, therefore, that his delusions targeted his brother and ex-girlfriend.

Before social networks, the perseveration of this delusion might have been limited to internal thinking, or gathering corroborative information by means of stalking. Social media outlets have provided a means to perseverate and implicate others remotely, however, and Mr. M soon expanded his delusions to include more peers.

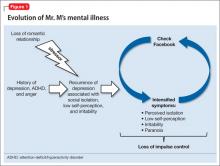

After beginning to suspect that friends and family are commenting on or criticizing him through Facebook, Mr. M experienced an irresistible impulse to repeatedly check the social network, which may have provided short-term relief of anticipatory anxiety, but that perpetuated the cycle. Constant access to the internet facilitated and intensified Mr. M’s cycle of paranoia, anxiety, and dysphoria. He called this process an “addiction.” A conceptual framework of the development of Mr. M’s maladaptive use of Facebook is illustrated in Figure 1.

Risk factors

Insecurity with one’s self-worth also may be a warning sign. Online social networking circumvents the need for physical interaction. A Facebook profile allows a person to selectively portray himself (herself) to the world, which may not be congruous with how his peers see him in everyday life. Patients who fear criticism or judgment may be more prone to maladaptive Facebook use, because they might feel empowered by the control they have over how others see them—online, at least.

Limited or, in Mr. M’s case, singular romantic experience may have influenced the course of his illness. Mr. M described his romantic involvement as a single, tumultuous relationship that lasted several years. Young patients with limited romantic experience may struggle to develop healthy protective mechanisms and may become preoccupied with the details of the situation, such that it interferes with functioning.

Mr. M’s history of ADHD might be a risk factor for abnormal patterns of internet use. Patients with ADHD have increased attentiveness with visually stimulating tasks—specifically, computers and video games.12

Last, it is unclear how, or if, Mr. M’s history of head injury contributed to his symptoms. There were no clear, temporal changes in cognition or emotion associated with the head injury, and he did not receive regular follow-up. Significant cognitive impairment does not appear to be a factor.

a) restart fluoxetine

b) begin an atypical antipsychotic

c) begin a mood stabilizer and atypical antipsychotic

d) encourage Mr. M to deactivate his Facebook account

TREATMENT: Observed use

Quetiapine is selected to target psychosis, agitation, and insomnia characterized by difficulty with sleep initiation. Risperidone is added as a short-term agent to boost antipsychotic effect during the day when Mr. M is not fully responsive to quetiapine alone. Valproic acid is added on admission as a mood stabilizer to target emotional lability, impulsiveness, and possible mania.

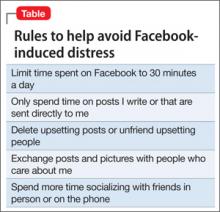

After several days of treatment, and without access to a computer, Mr. M is calmer. We begin to assess the challenges of self-limiting time spent on Facebook; Mr. M explains that, before hospitalization, he had deactivated his Facebook account several times to try to rid himself of what he describes as an “addiction to social media”; soon afterward, however, he experienced overwhelming anxiety that led him to reactivate his account.

We sit with Mr. M as he logs in to Facebook and discuss the range of alternative explanations that specific public messages on his news feed could have. Explicitly listing alternative explanations is a technique used in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Mr. M begins to demonstrate increased insight regarding his paranoia and possible misinterpretation of information gleaned via Facebook; however, he still believes that masked references to him had existed. During his hospital stay he begins to acknowledge the problems that online interactions pose compared with face-to-face interactions, stating that, “There’s no emotion in [Facebook], so you can easily misinterpret what someone says.”

The authors’ observations

Mr. M was discharged after 7 days of treatment and has been seen weekly as an outpatient for 3 months without need for further hospitalization.

Bottom Line

Pervasive access to social media represents a vehicle for relapse of many psychiatric conditions. Younger patients may be especially at risk because they are more likely to use social media and are in the age range for onset of psychiatric illness. Although some degree of dependence on online networks can be considered normal, patients suffering from mental illness represent a vulnerable population for maladaptive online interactions.

Related Resources

• Sandler EP. If you’re in crisis, go online. Psychology Today. www.psychologytoday.com/blog/promoting-hope-preventing-suicide/201110/if-you-re-in-crisis-go-online. Published October 26, 2011.

• Nitzan U, Shoshan E, Lev-Ran S, et al. Internet-related psychosis−a sign of the times. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2011;48(3):207-211.

• Martin EA, Bailey DH, Cicero DC, et al. Social networking profile correlates of schizotypy. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2-3):641-646.

Drug Brand Names

Fluoxetine • Prozac Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal Valproic acid • Depakote

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Facebook. Facebook reports second quarter 2013 results. http://investor.fb.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID= 780093. Updated July 24, 2013. Accessed July 29, 2013.

2. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Offline consequences of online victimization: school violence and delinquency. Journal of School Violence. 2007;6(3):89-112.

3. Pantic I, Damjanovic A, Todorovic J, et al. Associations between online social networking and depression in high school students: behavioral physiology viewpoint. Psychiatr Danub. 2012;24(1):90-93.

4. O’Keeffe GS, Clarke-Pearson K; Council on Communications and Media. The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):800-804.

5. Gonzales AL, Hancock JT. Mirror, mirror on my Facebook wall: effects of exposure to Facebook on self-esteem. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14(1-2):79-83.

6. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide. Arch Suicide Res. 2010;14(3):206-221.

7. Selfhout MH, Branje SJ, Delsing M, et al. Different types of Internet use, depression, and social anxiety: the role of perceived friendship quality. J Adolesc. 2009;32(4):819-833.

8. Morrison CM, Gore H. The relationship between excessive internet use and depression: a questionnaire-based study of 1,319 young people and adults. Psychopathology. 2010; 43:121-126.

9. Andreassen CS, Torsheim T, Brunborg GS, et al. Development of a Facebook Addiction Scale. Psychol Rep. 2012;110(2):501-517.

10. SAMHSA News. Suicide prevention: a national priority. vol 20, no 3. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2012.

11. Facebook. New partnership between Facebook and the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=310287485658707. Accessed July 25, 2013.

12. Weinstein A, Weizman A. Emerging association between addictive gaming and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(5):590-597.

CASE: Paranoid and online

Mr. M, age 22, is brought to the emergency department by family because they are concerned about his paranoia and increasing agitation related to Facebook posts by friends and siblings. At age 8, Mr. M was diagnosed with depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and anger management problems, which were well controlled with fluoxetine until last year, when he discontinued psychiatric follow-up. Mr. M’s girlfriend ended their relationship 1 month ago, although it is unclear whether the break-up was caused by his depressive symptoms or exacerbated them. In the last 2 days, his parents have noticed an increase in his delusional thoughts and aggressive behavior.

Family psychiatric history is not significant. Five years ago, Mr. M suffered a head injury in a motor vehicle collision, but completed high school without evidence of cognitive impairment or behavioral changes.

Mr. M appears disheveled and irritable. He reports his mood as “depressed,” but denies suicidal or homicidal ideations. He has no history of violence or antisocial behavior.

Mr. M is alert and oriented with clear speech, intact language, and grossly intact memory and concentration—although, he admits, “I just obsess over certain thoughts.” He endorses feelings of anxiety, insomnia, low energy, lack of sleep secondary to his paranoia, and claims that “something was said on Facebook about a girl and everyone is in on it.” He explains that his Facebook friends talk in “analogies” about him, and reports that, “I can just tell that’s what they are talking about even if they don’t say it directly.”

a) impulse control disorder

b) brief psychotic episode

c) psychotic depression

d) bipolar disorder

The authors’ observations

The last decade has seen a rise in the creation and use of social networking sites such as Facebook, Myspace, and Twitter. Facebook has 1.15 billion monthly active users.1 Seventy-five percent of teenagers own cell phones, and 25% report using their phones to access social media outlets.2 More than 50% of teenagers visit a social networking site daily, with 22% logging in to their favorite social media network more than 10 times a day.3 The easy accessibility of social media outlets has prompted study of the association of that accessibility with anxiety, depression, and self-esteem.3-7

Although not a DSM-5 or ICD-10 diagnosis, internet addiction has been correlated with depression.8 Similarly, O’Keefe and colleagues describe Facebook depression in teens who spend a large amount of time on social networking sites.4 The recently developed Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS)9 evaluates the six core elements of addiction (salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse) in Facebook users.

Facebook certainly provides a valuable mechanism for friends to stay connected in an increasingly global society, and has acknowledged the potential it has to address mental illness. In 2011, Facebook partnered with the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline to allow users to report observed suicidal content, thereby utilizing the online community to facilitate delivery of mental health resources.10,11

HISTORY: Sibling rivalry

Mr. M had a romantic relationship with “Ms. B” in high school that he describes as “on and off,” beginning during his sophomore year. He describes himself as a “quick learner” who is task-oriented. He says he was outgoing in high school but became more introverted during his last year there. After high school, Mr. M worked as an electrician and discontinued psychiatric follow-up because he “felt fine.” He lives at home with his parents, two older sisters, and twin brother, who he identifies as being a lifelong “rival.”

After Ms. B ended her relationship with Mr. M, he began to suspect that she had become romantically involved with his twin brother. After Mr. M observed his brother leaving the house one night, he confronted his twin, who denied any involvement with Ms. B. After his brother left, Mr. M became enraged and punched a wall, fracturing his hand.

Two weeks before admission, Mr. M became increasingly preoccupied with suspicions of his brother’s involvement with Ms. B and looked for evidence on Facebook. Mr. M intensely monitored his Facebook news feed, which constantly updates to show public posts made by a user’s Facebook friends. He interpreted his friends’ posts as either directly relating to him or to a new relationship between Ms. B and his twin brother, stating that his friends were “talking in analogies” rather than directly using names.

Mr. M’s Facebook use rapidly increased to 3 or more hours a day. He can access Facebook from his laptop or cell phone, and reports logging in more than 10 times throughout the day. He says that, on Facebook, “it’s easier to talk trash” because people can say things they would not normally say face to face. He also states that Facebook is “ruining personal relationships,” and that it is “so easy to be in touch with everyone without really being in touch.”

The authors’ observations

In Mr. M’s case, Facebook served as a vehicle through which he could pursue a non-bizarre delusion. Mr. M openly admitted to viewing his twin brother as a rival; it is not surprising, therefore, that his delusions targeted his brother and ex-girlfriend.

Before social networks, the perseveration of this delusion might have been limited to internal thinking, or gathering corroborative information by means of stalking. Social media outlets have provided a means to perseverate and implicate others remotely, however, and Mr. M soon expanded his delusions to include more peers.

After beginning to suspect that friends and family are commenting on or criticizing him through Facebook, Mr. M experienced an irresistible impulse to repeatedly check the social network, which may have provided short-term relief of anticipatory anxiety, but that perpetuated the cycle. Constant access to the internet facilitated and intensified Mr. M’s cycle of paranoia, anxiety, and dysphoria. He called this process an “addiction.” A conceptual framework of the development of Mr. M’s maladaptive use of Facebook is illustrated in Figure 1.

Risk factors

Insecurity with one’s self-worth also may be a warning sign. Online social networking circumvents the need for physical interaction. A Facebook profile allows a person to selectively portray himself (herself) to the world, which may not be congruous with how his peers see him in everyday life. Patients who fear criticism or judgment may be more prone to maladaptive Facebook use, because they might feel empowered by the control they have over how others see them—online, at least.

Limited or, in Mr. M’s case, singular romantic experience may have influenced the course of his illness. Mr. M described his romantic involvement as a single, tumultuous relationship that lasted several years. Young patients with limited romantic experience may struggle to develop healthy protective mechanisms and may become preoccupied with the details of the situation, such that it interferes with functioning.

Mr. M’s history of ADHD might be a risk factor for abnormal patterns of internet use. Patients with ADHD have increased attentiveness with visually stimulating tasks—specifically, computers and video games.12

Last, it is unclear how, or if, Mr. M’s history of head injury contributed to his symptoms. There were no clear, temporal changes in cognition or emotion associated with the head injury, and he did not receive regular follow-up. Significant cognitive impairment does not appear to be a factor.

a) restart fluoxetine

b) begin an atypical antipsychotic

c) begin a mood stabilizer and atypical antipsychotic

d) encourage Mr. M to deactivate his Facebook account

TREATMENT: Observed use

Quetiapine is selected to target psychosis, agitation, and insomnia characterized by difficulty with sleep initiation. Risperidone is added as a short-term agent to boost antipsychotic effect during the day when Mr. M is not fully responsive to quetiapine alone. Valproic acid is added on admission as a mood stabilizer to target emotional lability, impulsiveness, and possible mania.

After several days of treatment, and without access to a computer, Mr. M is calmer. We begin to assess the challenges of self-limiting time spent on Facebook; Mr. M explains that, before hospitalization, he had deactivated his Facebook account several times to try to rid himself of what he describes as an “addiction to social media”; soon afterward, however, he experienced overwhelming anxiety that led him to reactivate his account.

We sit with Mr. M as he logs in to Facebook and discuss the range of alternative explanations that specific public messages on his news feed could have. Explicitly listing alternative explanations is a technique used in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Mr. M begins to demonstrate increased insight regarding his paranoia and possible misinterpretation of information gleaned via Facebook; however, he still believes that masked references to him had existed. During his hospital stay he begins to acknowledge the problems that online interactions pose compared with face-to-face interactions, stating that, “There’s no emotion in [Facebook], so you can easily misinterpret what someone says.”

The authors’ observations

Mr. M was discharged after 7 days of treatment and has been seen weekly as an outpatient for 3 months without need for further hospitalization.

Bottom Line

Pervasive access to social media represents a vehicle for relapse of many psychiatric conditions. Younger patients may be especially at risk because they are more likely to use social media and are in the age range for onset of psychiatric illness. Although some degree of dependence on online networks can be considered normal, patients suffering from mental illness represent a vulnerable population for maladaptive online interactions.

Related Resources

• Sandler EP. If you’re in crisis, go online. Psychology Today. www.psychologytoday.com/blog/promoting-hope-preventing-suicide/201110/if-you-re-in-crisis-go-online. Published October 26, 2011.

• Nitzan U, Shoshan E, Lev-Ran S, et al. Internet-related psychosis−a sign of the times. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2011;48(3):207-211.

• Martin EA, Bailey DH, Cicero DC, et al. Social networking profile correlates of schizotypy. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2-3):641-646.

Drug Brand Names

Fluoxetine • Prozac Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal Valproic acid • Depakote

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE: Paranoid and online

Mr. M, age 22, is brought to the emergency department by family because they are concerned about his paranoia and increasing agitation related to Facebook posts by friends and siblings. At age 8, Mr. M was diagnosed with depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and anger management problems, which were well controlled with fluoxetine until last year, when he discontinued psychiatric follow-up. Mr. M’s girlfriend ended their relationship 1 month ago, although it is unclear whether the break-up was caused by his depressive symptoms or exacerbated them. In the last 2 days, his parents have noticed an increase in his delusional thoughts and aggressive behavior.

Family psychiatric history is not significant. Five years ago, Mr. M suffered a head injury in a motor vehicle collision, but completed high school without evidence of cognitive impairment or behavioral changes.

Mr. M appears disheveled and irritable. He reports his mood as “depressed,” but denies suicidal or homicidal ideations. He has no history of violence or antisocial behavior.

Mr. M is alert and oriented with clear speech, intact language, and grossly intact memory and concentration—although, he admits, “I just obsess over certain thoughts.” He endorses feelings of anxiety, insomnia, low energy, lack of sleep secondary to his paranoia, and claims that “something was said on Facebook about a girl and everyone is in on it.” He explains that his Facebook friends talk in “analogies” about him, and reports that, “I can just tell that’s what they are talking about even if they don’t say it directly.”

a) impulse control disorder

b) brief psychotic episode

c) psychotic depression

d) bipolar disorder

The authors’ observations

The last decade has seen a rise in the creation and use of social networking sites such as Facebook, Myspace, and Twitter. Facebook has 1.15 billion monthly active users.1 Seventy-five percent of teenagers own cell phones, and 25% report using their phones to access social media outlets.2 More than 50% of teenagers visit a social networking site daily, with 22% logging in to their favorite social media network more than 10 times a day.3 The easy accessibility of social media outlets has prompted study of the association of that accessibility with anxiety, depression, and self-esteem.3-7

Although not a DSM-5 or ICD-10 diagnosis, internet addiction has been correlated with depression.8 Similarly, O’Keefe and colleagues describe Facebook depression in teens who spend a large amount of time on social networking sites.4 The recently developed Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS)9 evaluates the six core elements of addiction (salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse) in Facebook users.

Facebook certainly provides a valuable mechanism for friends to stay connected in an increasingly global society, and has acknowledged the potential it has to address mental illness. In 2011, Facebook partnered with the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline to allow users to report observed suicidal content, thereby utilizing the online community to facilitate delivery of mental health resources.10,11

HISTORY: Sibling rivalry

Mr. M had a romantic relationship with “Ms. B” in high school that he describes as “on and off,” beginning during his sophomore year. He describes himself as a “quick learner” who is task-oriented. He says he was outgoing in high school but became more introverted during his last year there. After high school, Mr. M worked as an electrician and discontinued psychiatric follow-up because he “felt fine.” He lives at home with his parents, two older sisters, and twin brother, who he identifies as being a lifelong “rival.”

After Ms. B ended her relationship with Mr. M, he began to suspect that she had become romantically involved with his twin brother. After Mr. M observed his brother leaving the house one night, he confronted his twin, who denied any involvement with Ms. B. After his brother left, Mr. M became enraged and punched a wall, fracturing his hand.

Two weeks before admission, Mr. M became increasingly preoccupied with suspicions of his brother’s involvement with Ms. B and looked for evidence on Facebook. Mr. M intensely monitored his Facebook news feed, which constantly updates to show public posts made by a user’s Facebook friends. He interpreted his friends’ posts as either directly relating to him or to a new relationship between Ms. B and his twin brother, stating that his friends were “talking in analogies” rather than directly using names.

Mr. M’s Facebook use rapidly increased to 3 or more hours a day. He can access Facebook from his laptop or cell phone, and reports logging in more than 10 times throughout the day. He says that, on Facebook, “it’s easier to talk trash” because people can say things they would not normally say face to face. He also states that Facebook is “ruining personal relationships,” and that it is “so easy to be in touch with everyone without really being in touch.”

The authors’ observations

In Mr. M’s case, Facebook served as a vehicle through which he could pursue a non-bizarre delusion. Mr. M openly admitted to viewing his twin brother as a rival; it is not surprising, therefore, that his delusions targeted his brother and ex-girlfriend.

Before social networks, the perseveration of this delusion might have been limited to internal thinking, or gathering corroborative information by means of stalking. Social media outlets have provided a means to perseverate and implicate others remotely, however, and Mr. M soon expanded his delusions to include more peers.

After beginning to suspect that friends and family are commenting on or criticizing him through Facebook, Mr. M experienced an irresistible impulse to repeatedly check the social network, which may have provided short-term relief of anticipatory anxiety, but that perpetuated the cycle. Constant access to the internet facilitated and intensified Mr. M’s cycle of paranoia, anxiety, and dysphoria. He called this process an “addiction.” A conceptual framework of the development of Mr. M’s maladaptive use of Facebook is illustrated in Figure 1.

Risk factors

Insecurity with one’s self-worth also may be a warning sign. Online social networking circumvents the need for physical interaction. A Facebook profile allows a person to selectively portray himself (herself) to the world, which may not be congruous with how his peers see him in everyday life. Patients who fear criticism or judgment may be more prone to maladaptive Facebook use, because they might feel empowered by the control they have over how others see them—online, at least.

Limited or, in Mr. M’s case, singular romantic experience may have influenced the course of his illness. Mr. M described his romantic involvement as a single, tumultuous relationship that lasted several years. Young patients with limited romantic experience may struggle to develop healthy protective mechanisms and may become preoccupied with the details of the situation, such that it interferes with functioning.

Mr. M’s history of ADHD might be a risk factor for abnormal patterns of internet use. Patients with ADHD have increased attentiveness with visually stimulating tasks—specifically, computers and video games.12

Last, it is unclear how, or if, Mr. M’s history of head injury contributed to his symptoms. There were no clear, temporal changes in cognition or emotion associated with the head injury, and he did not receive regular follow-up. Significant cognitive impairment does not appear to be a factor.

a) restart fluoxetine

b) begin an atypical antipsychotic

c) begin a mood stabilizer and atypical antipsychotic

d) encourage Mr. M to deactivate his Facebook account

TREATMENT: Observed use

Quetiapine is selected to target psychosis, agitation, and insomnia characterized by difficulty with sleep initiation. Risperidone is added as a short-term agent to boost antipsychotic effect during the day when Mr. M is not fully responsive to quetiapine alone. Valproic acid is added on admission as a mood stabilizer to target emotional lability, impulsiveness, and possible mania.

After several days of treatment, and without access to a computer, Mr. M is calmer. We begin to assess the challenges of self-limiting time spent on Facebook; Mr. M explains that, before hospitalization, he had deactivated his Facebook account several times to try to rid himself of what he describes as an “addiction to social media”; soon afterward, however, he experienced overwhelming anxiety that led him to reactivate his account.

We sit with Mr. M as he logs in to Facebook and discuss the range of alternative explanations that specific public messages on his news feed could have. Explicitly listing alternative explanations is a technique used in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Mr. M begins to demonstrate increased insight regarding his paranoia and possible misinterpretation of information gleaned via Facebook; however, he still believes that masked references to him had existed. During his hospital stay he begins to acknowledge the problems that online interactions pose compared with face-to-face interactions, stating that, “There’s no emotion in [Facebook], so you can easily misinterpret what someone says.”

The authors’ observations

Mr. M was discharged after 7 days of treatment and has been seen weekly as an outpatient for 3 months without need for further hospitalization.

Bottom Line

Pervasive access to social media represents a vehicle for relapse of many psychiatric conditions. Younger patients may be especially at risk because they are more likely to use social media and are in the age range for onset of psychiatric illness. Although some degree of dependence on online networks can be considered normal, patients suffering from mental illness represent a vulnerable population for maladaptive online interactions.

Related Resources

• Sandler EP. If you’re in crisis, go online. Psychology Today. www.psychologytoday.com/blog/promoting-hope-preventing-suicide/201110/if-you-re-in-crisis-go-online. Published October 26, 2011.

• Nitzan U, Shoshan E, Lev-Ran S, et al. Internet-related psychosis−a sign of the times. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2011;48(3):207-211.

• Martin EA, Bailey DH, Cicero DC, et al. Social networking profile correlates of schizotypy. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2-3):641-646.

Drug Brand Names

Fluoxetine • Prozac Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal Valproic acid • Depakote

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Facebook. Facebook reports second quarter 2013 results. http://investor.fb.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID= 780093. Updated July 24, 2013. Accessed July 29, 2013.

2. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Offline consequences of online victimization: school violence and delinquency. Journal of School Violence. 2007;6(3):89-112.

3. Pantic I, Damjanovic A, Todorovic J, et al. Associations between online social networking and depression in high school students: behavioral physiology viewpoint. Psychiatr Danub. 2012;24(1):90-93.

4. O’Keeffe GS, Clarke-Pearson K; Council on Communications and Media. The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):800-804.

5. Gonzales AL, Hancock JT. Mirror, mirror on my Facebook wall: effects of exposure to Facebook on self-esteem. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14(1-2):79-83.

6. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide. Arch Suicide Res. 2010;14(3):206-221.

7. Selfhout MH, Branje SJ, Delsing M, et al. Different types of Internet use, depression, and social anxiety: the role of perceived friendship quality. J Adolesc. 2009;32(4):819-833.

8. Morrison CM, Gore H. The relationship between excessive internet use and depression: a questionnaire-based study of 1,319 young people and adults. Psychopathology. 2010; 43:121-126.

9. Andreassen CS, Torsheim T, Brunborg GS, et al. Development of a Facebook Addiction Scale. Psychol Rep. 2012;110(2):501-517.

10. SAMHSA News. Suicide prevention: a national priority. vol 20, no 3. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2012.

11. Facebook. New partnership between Facebook and the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=310287485658707. Accessed July 25, 2013.

12. Weinstein A, Weizman A. Emerging association between addictive gaming and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(5):590-597.

1. Facebook. Facebook reports second quarter 2013 results. http://investor.fb.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID= 780093. Updated July 24, 2013. Accessed July 29, 2013.

2. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Offline consequences of online victimization: school violence and delinquency. Journal of School Violence. 2007;6(3):89-112.

3. Pantic I, Damjanovic A, Todorovic J, et al. Associations between online social networking and depression in high school students: behavioral physiology viewpoint. Psychiatr Danub. 2012;24(1):90-93.

4. O’Keeffe GS, Clarke-Pearson K; Council on Communications and Media. The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):800-804.

5. Gonzales AL, Hancock JT. Mirror, mirror on my Facebook wall: effects of exposure to Facebook on self-esteem. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14(1-2):79-83.

6. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide. Arch Suicide Res. 2010;14(3):206-221.

7. Selfhout MH, Branje SJ, Delsing M, et al. Different types of Internet use, depression, and social anxiety: the role of perceived friendship quality. J Adolesc. 2009;32(4):819-833.

8. Morrison CM, Gore H. The relationship between excessive internet use and depression: a questionnaire-based study of 1,319 young people and adults. Psychopathology. 2010; 43:121-126.

9. Andreassen CS, Torsheim T, Brunborg GS, et al. Development of a Facebook Addiction Scale. Psychol Rep. 2012;110(2):501-517.

10. SAMHSA News. Suicide prevention: a national priority. vol 20, no 3. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2012.

11. Facebook. New partnership between Facebook and the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=310287485658707. Accessed July 25, 2013.

12. Weinstein A, Weizman A. Emerging association between addictive gaming and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(5):590-597.

Consider this slow-taper program for benzodiazepines

Concerns about prescription medication abuse have led to the creation of remediation plans directed to reduce overuse, multiple prescribers, and diversion of prescribed drugs. One such plan from the United Kingdom, described below, has shown it is possible to taper a patient off of benzodiazepines.1,2

Before starting a tapering plan, inform the patient about the risks of withdrawal.3 Abrupt reductions from high-dose benzodiazepines can result in seizures, psychotic reactions, and agitation.1-3 Understanding the tapering regimen enhances compliance and outcomes. Stress the importance of careful adherence and provide close psychosocial monitoring and fail-safe means for patient contact if someone is experiencing difficulties. Supportive psychotherapy improves the prognosis.4 On a clinical basis, additional, adjunctive, symptomatic, or other medications may be required for safe illness management.

Managing comorbid medical conditions and psychopathologies—including addressing other substances of abuse—is important.1-4 Tapering one or more substances at a time—even nicotine—is not advised. Refer patients to a self-help group or substance abuse rehabilitation program.

Slow tapering is safer and better tolerated than more abrupt techniques.1-5 If the patient experiences overt clinical signs of withdrawal, such as tachycardia or other hyperadrenergia during dosage reduction, maintain the previous dosage until the next tapering date.

For persons who take a short-acting benzodiazepine—eg, alprazolam or lorazepam—convert the dosage into an equivalent dosage of a long-acting benzodiazepine—eg, diazepam.1,2 Metabolized slowly, with a long half-life, diazepam allows a consistent, slow decline in concentration while tapering the dosage. This helps avoid severe withdrawal.1-5 For patients who have been taking alprazolam or clonazepam, 1 mg, the equivalent diazepam dosage would be 20 mg; for temazepam, 30 mg, the diazepam dosage would be 15 mg; for lorazepam, 1 mg, oxazepam, 20 mg, or chlordiazepoxide, 25 mg, the diazepam dosage would be 10 mg.1,2

Prescribe the to-be-tapered benzodiazepine at five-sixths of that dose and prescribe one-sixth of the diazepam amount daily. Proceed with tapering

every 1 to 2 weeks by a one-sixth dose reduction of the tapered medication and a one-sixth increase in diazepam. Continue until diazepam is used alone and well-tolerated.

Once the patient is taking only diazepam, decrease the dosage by 2 mg every 2 weeks until the patient is doing well on a relatively small dosage of diazepam.1,2 Subsequent diazepam reductions are at 1 mg less every 1 to 2 weeks, until the patient is able to completely discontinue the medication.

Continue monitoring until clinical stability is achieved or otherwise indicated. Be aware that some people might switch to other substances of abuse.

1. Ashton H. Benzodiazepine withdrawal: an unfinished story. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1984;288(6424):1135-1140.

2. Benzodiazepines: how they work and how to withdraw (aka The Ashton Manual). http://www.benzo.org.uk/manual. Accessed March 27, 2013.

3. Lader M. Benzodiazepine harm: how can it be reduced? [published online August 10, 2012] Br J Clin Pharmacol. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04418.x.

4. Morin CM, Bastien C, Guay B, et al. Randomized clinical trial of supervised tapering and cognitive behavior therapy to facilitate benzodiazepine discontinuation in older adults with chronic insomnia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(2):332-342.

5. Lopez-Peig C, Mundet X, Casabella B, et al. Analysis of benzodiazepine withdrawal program managed by primary care nurses in Spain. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:684. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-684.

Concerns about prescription medication abuse have led to the creation of remediation plans directed to reduce overuse, multiple prescribers, and diversion of prescribed drugs. One such plan from the United Kingdom, described below, has shown it is possible to taper a patient off of benzodiazepines.1,2

Before starting a tapering plan, inform the patient about the risks of withdrawal.3 Abrupt reductions from high-dose benzodiazepines can result in seizures, psychotic reactions, and agitation.1-3 Understanding the tapering regimen enhances compliance and outcomes. Stress the importance of careful adherence and provide close psychosocial monitoring and fail-safe means for patient contact if someone is experiencing difficulties. Supportive psychotherapy improves the prognosis.4 On a clinical basis, additional, adjunctive, symptomatic, or other medications may be required for safe illness management.

Managing comorbid medical conditions and psychopathologies—including addressing other substances of abuse—is important.1-4 Tapering one or more substances at a time—even nicotine—is not advised. Refer patients to a self-help group or substance abuse rehabilitation program.

Slow tapering is safer and better tolerated than more abrupt techniques.1-5 If the patient experiences overt clinical signs of withdrawal, such as tachycardia or other hyperadrenergia during dosage reduction, maintain the previous dosage until the next tapering date.

For persons who take a short-acting benzodiazepine—eg, alprazolam or lorazepam—convert the dosage into an equivalent dosage of a long-acting benzodiazepine—eg, diazepam.1,2 Metabolized slowly, with a long half-life, diazepam allows a consistent, slow decline in concentration while tapering the dosage. This helps avoid severe withdrawal.1-5 For patients who have been taking alprazolam or clonazepam, 1 mg, the equivalent diazepam dosage would be 20 mg; for temazepam, 30 mg, the diazepam dosage would be 15 mg; for lorazepam, 1 mg, oxazepam, 20 mg, or chlordiazepoxide, 25 mg, the diazepam dosage would be 10 mg.1,2

Prescribe the to-be-tapered benzodiazepine at five-sixths of that dose and prescribe one-sixth of the diazepam amount daily. Proceed with tapering

every 1 to 2 weeks by a one-sixth dose reduction of the tapered medication and a one-sixth increase in diazepam. Continue until diazepam is used alone and well-tolerated.

Once the patient is taking only diazepam, decrease the dosage by 2 mg every 2 weeks until the patient is doing well on a relatively small dosage of diazepam.1,2 Subsequent diazepam reductions are at 1 mg less every 1 to 2 weeks, until the patient is able to completely discontinue the medication.

Continue monitoring until clinical stability is achieved or otherwise indicated. Be aware that some people might switch to other substances of abuse.

Concerns about prescription medication abuse have led to the creation of remediation plans directed to reduce overuse, multiple prescribers, and diversion of prescribed drugs. One such plan from the United Kingdom, described below, has shown it is possible to taper a patient off of benzodiazepines.1,2

Before starting a tapering plan, inform the patient about the risks of withdrawal.3 Abrupt reductions from high-dose benzodiazepines can result in seizures, psychotic reactions, and agitation.1-3 Understanding the tapering regimen enhances compliance and outcomes. Stress the importance of careful adherence and provide close psychosocial monitoring and fail-safe means for patient contact if someone is experiencing difficulties. Supportive psychotherapy improves the prognosis.4 On a clinical basis, additional, adjunctive, symptomatic, or other medications may be required for safe illness management.

Managing comorbid medical conditions and psychopathologies—including addressing other substances of abuse—is important.1-4 Tapering one or more substances at a time—even nicotine—is not advised. Refer patients to a self-help group or substance abuse rehabilitation program.

Slow tapering is safer and better tolerated than more abrupt techniques.1-5 If the patient experiences overt clinical signs of withdrawal, such as tachycardia or other hyperadrenergia during dosage reduction, maintain the previous dosage until the next tapering date.

For persons who take a short-acting benzodiazepine—eg, alprazolam or lorazepam—convert the dosage into an equivalent dosage of a long-acting benzodiazepine—eg, diazepam.1,2 Metabolized slowly, with a long half-life, diazepam allows a consistent, slow decline in concentration while tapering the dosage. This helps avoid severe withdrawal.1-5 For patients who have been taking alprazolam or clonazepam, 1 mg, the equivalent diazepam dosage would be 20 mg; for temazepam, 30 mg, the diazepam dosage would be 15 mg; for lorazepam, 1 mg, oxazepam, 20 mg, or chlordiazepoxide, 25 mg, the diazepam dosage would be 10 mg.1,2

Prescribe the to-be-tapered benzodiazepine at five-sixths of that dose and prescribe one-sixth of the diazepam amount daily. Proceed with tapering

every 1 to 2 weeks by a one-sixth dose reduction of the tapered medication and a one-sixth increase in diazepam. Continue until diazepam is used alone and well-tolerated.

Once the patient is taking only diazepam, decrease the dosage by 2 mg every 2 weeks until the patient is doing well on a relatively small dosage of diazepam.1,2 Subsequent diazepam reductions are at 1 mg less every 1 to 2 weeks, until the patient is able to completely discontinue the medication.

Continue monitoring until clinical stability is achieved or otherwise indicated. Be aware that some people might switch to other substances of abuse.

1. Ashton H. Benzodiazepine withdrawal: an unfinished story. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1984;288(6424):1135-1140.

2. Benzodiazepines: how they work and how to withdraw (aka The Ashton Manual). http://www.benzo.org.uk/manual. Accessed March 27, 2013.

3. Lader M. Benzodiazepine harm: how can it be reduced? [published online August 10, 2012] Br J Clin Pharmacol. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04418.x.

4. Morin CM, Bastien C, Guay B, et al. Randomized clinical trial of supervised tapering and cognitive behavior therapy to facilitate benzodiazepine discontinuation in older adults with chronic insomnia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(2):332-342.

5. Lopez-Peig C, Mundet X, Casabella B, et al. Analysis of benzodiazepine withdrawal program managed by primary care nurses in Spain. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:684. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-684.

1. Ashton H. Benzodiazepine withdrawal: an unfinished story. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1984;288(6424):1135-1140.

2. Benzodiazepines: how they work and how to withdraw (aka The Ashton Manual). http://www.benzo.org.uk/manual. Accessed March 27, 2013.

3. Lader M. Benzodiazepine harm: how can it be reduced? [published online August 10, 2012] Br J Clin Pharmacol. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04418.x.

4. Morin CM, Bastien C, Guay B, et al. Randomized clinical trial of supervised tapering and cognitive behavior therapy to facilitate benzodiazepine discontinuation in older adults with chronic insomnia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(2):332-342.

5. Lopez-Peig C, Mundet X, Casabella B, et al. Analysis of benzodiazepine withdrawal program managed by primary care nurses in Spain. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:684. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-684.

Do glucocorticoids hold promise as a treatment for PTSD?

As symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) progress, the involved person’s physical and mental health deteriorates.1 This sparks lifestyle changes that allow them to avoid re-exposure to triggering stimuli; however, it also increases their risk of social isolation. Early clinical investigation has found that patients who experience hyperarousal symptoms of overt PTSD—difficulty sleeping, emotional dyscontrol, hypervigilance, and an enhanced startle response—could benefit from the stress-reducing capacity of glucocorticoids.

Decreased glucocorticoids

After a distressing situation, norepinephrine levels rise acutely.2,3 This contributes to a protective retention of potentially threatening memories, which is how people learn to avoid danger.

Glucocorticoid secretion enhances a patient’s coping mechanisms by helping them process information in a way that diminishes retrieval of fear-evoking memories.2,3 Glucocorticoid, also called cortisol, is referred to as a “stress hormone.” Cortisol promotes emotional adaptability following a traumatic event; this action diminishes future, inappropriate retrieval of frightening memories as a physiologic mechanism to help people cope with upsetting situations.3

PTSD pathogenesis involves altered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function; sustained stress results in decreased levels of circulating glucocorticoid. This is a consequence of enhanced negative feedback and increased glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity, which is evidenced by results of abnormal dexamethasone suppression tests.1 Downregulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) receptors in the pituitary glands and increased CRH levels have been documented in PTSD patients.1,4 An association between high CRH levels and an increase in startle response explains the exaggerated startle response observed in patients with PTSD. Higher circulating glucocorticoid has the opposite effect4; there is an inverse relationship between the daily level of glucocorticoid and startle amplitude. A low level of circulating glucocorticoid promotes recall of frightening events that results in persistent re-experiencing of traumatic memories.2,3

Glucocorticoids in PTSD

Glucocorticoid administration reduces psychological and physiological responses to stress.3 Exogenous glucocorticoid administration affects cognition by interacting with serotonin, dopamine, and ã-aminobutyric acid by actions on the amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus.2,3 Research among veterans with and without PTSD recorded a decrease in startle response after administration of a single dose of 20 mg of hydrocortisone.4 Results of a large study documented that one dose of hydrocortisone administered at >35 mg can inhibit threatening memories and improve social function.3 Hydrocortisone is linked to anxiolytic effects in healthy persons and patients with social phobia or panic disorder.3,4 Because treatment of PTSD with antidepressants and benzodiazepines often is ineffective,5 glucocorticoids may offer a new pharmacotherapy option. Glucocorticoids have been prescribed as prophylactic agents shortly after an acutely stressful event to prevent development of PTSD.4 Hydrocortisone is not FDA-approved to treat PTSD; informed consent, physician discretion, and close monitoring are emphasized.

Glucocorticoid use in mitigating PTSD symptom emergence is under investigation. Research suggests that just one acute dose of hydrocortisone might benefit patients prone to PTSD.3,4 Further study is needed to establish whether prescribing hydrocortisone is efficacious.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Jones T, Moller MD. Implications of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functioning in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2011;17(6):393-403.

2. Blundell J, Blaiss CA, Lagace DC, et al. Block of glucocorticoid synthesis during re-activation inhibits extinction of an established fear memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2011;95(4):453-460.

3. Putman P, Roelofs K. Effects of single cortisol administrations on human affect reviewed: coping with stress through adaptive regulation of automatic cognitive processing. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(4):439-448.

4. Miller MW, McKinney AE, Kanter FS, et al. Hydrocortisone suppression of the fear-potentiated startle response and posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(7):970-980.

5. Nin MS, Martinez LA, Pibiri F, et al. Neurosteroids reduce social isolation-induced behavioral deficits: a proposed link with neurosteroid-mediated upregulation of BDNF expression. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2011;2(73):1-12.

As symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) progress, the involved person’s physical and mental health deteriorates.1 This sparks lifestyle changes that allow them to avoid re-exposure to triggering stimuli; however, it also increases their risk of social isolation. Early clinical investigation has found that patients who experience hyperarousal symptoms of overt PTSD—difficulty sleeping, emotional dyscontrol, hypervigilance, and an enhanced startle response—could benefit from the stress-reducing capacity of glucocorticoids.

Decreased glucocorticoids

After a distressing situation, norepinephrine levels rise acutely.2,3 This contributes to a protective retention of potentially threatening memories, which is how people learn to avoid danger.

Glucocorticoid secretion enhances a patient’s coping mechanisms by helping them process information in a way that diminishes retrieval of fear-evoking memories.2,3 Glucocorticoid, also called cortisol, is referred to as a “stress hormone.” Cortisol promotes emotional adaptability following a traumatic event; this action diminishes future, inappropriate retrieval of frightening memories as a physiologic mechanism to help people cope with upsetting situations.3

PTSD pathogenesis involves altered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function; sustained stress results in decreased levels of circulating glucocorticoid. This is a consequence of enhanced negative feedback and increased glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity, which is evidenced by results of abnormal dexamethasone suppression tests.1 Downregulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) receptors in the pituitary glands and increased CRH levels have been documented in PTSD patients.1,4 An association between high CRH levels and an increase in startle response explains the exaggerated startle response observed in patients with PTSD. Higher circulating glucocorticoid has the opposite effect4; there is an inverse relationship between the daily level of glucocorticoid and startle amplitude. A low level of circulating glucocorticoid promotes recall of frightening events that results in persistent re-experiencing of traumatic memories.2,3

Glucocorticoids in PTSD

Glucocorticoid administration reduces psychological and physiological responses to stress.3 Exogenous glucocorticoid administration affects cognition by interacting with serotonin, dopamine, and ã-aminobutyric acid by actions on the amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus.2,3 Research among veterans with and without PTSD recorded a decrease in startle response after administration of a single dose of 20 mg of hydrocortisone.4 Results of a large study documented that one dose of hydrocortisone administered at >35 mg can inhibit threatening memories and improve social function.3 Hydrocortisone is linked to anxiolytic effects in healthy persons and patients with social phobia or panic disorder.3,4 Because treatment of PTSD with antidepressants and benzodiazepines often is ineffective,5 glucocorticoids may offer a new pharmacotherapy option. Glucocorticoids have been prescribed as prophylactic agents shortly after an acutely stressful event to prevent development of PTSD.4 Hydrocortisone is not FDA-approved to treat PTSD; informed consent, physician discretion, and close monitoring are emphasized.

Glucocorticoid use in mitigating PTSD symptom emergence is under investigation. Research suggests that just one acute dose of hydrocortisone might benefit patients prone to PTSD.3,4 Further study is needed to establish whether prescribing hydrocortisone is efficacious.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

As symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) progress, the involved person’s physical and mental health deteriorates.1 This sparks lifestyle changes that allow them to avoid re-exposure to triggering stimuli; however, it also increases their risk of social isolation. Early clinical investigation has found that patients who experience hyperarousal symptoms of overt PTSD—difficulty sleeping, emotional dyscontrol, hypervigilance, and an enhanced startle response—could benefit from the stress-reducing capacity of glucocorticoids.

Decreased glucocorticoids

After a distressing situation, norepinephrine levels rise acutely.2,3 This contributes to a protective retention of potentially threatening memories, which is how people learn to avoid danger.

Glucocorticoid secretion enhances a patient’s coping mechanisms by helping them process information in a way that diminishes retrieval of fear-evoking memories.2,3 Glucocorticoid, also called cortisol, is referred to as a “stress hormone.” Cortisol promotes emotional adaptability following a traumatic event; this action diminishes future, inappropriate retrieval of frightening memories as a physiologic mechanism to help people cope with upsetting situations.3

PTSD pathogenesis involves altered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function; sustained stress results in decreased levels of circulating glucocorticoid. This is a consequence of enhanced negative feedback and increased glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity, which is evidenced by results of abnormal dexamethasone suppression tests.1 Downregulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) receptors in the pituitary glands and increased CRH levels have been documented in PTSD patients.1,4 An association between high CRH levels and an increase in startle response explains the exaggerated startle response observed in patients with PTSD. Higher circulating glucocorticoid has the opposite effect4; there is an inverse relationship between the daily level of glucocorticoid and startle amplitude. A low level of circulating glucocorticoid promotes recall of frightening events that results in persistent re-experiencing of traumatic memories.2,3

Glucocorticoids in PTSD

Glucocorticoid administration reduces psychological and physiological responses to stress.3 Exogenous glucocorticoid administration affects cognition by interacting with serotonin, dopamine, and ã-aminobutyric acid by actions on the amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus.2,3 Research among veterans with and without PTSD recorded a decrease in startle response after administration of a single dose of 20 mg of hydrocortisone.4 Results of a large study documented that one dose of hydrocortisone administered at >35 mg can inhibit threatening memories and improve social function.3 Hydrocortisone is linked to anxiolytic effects in healthy persons and patients with social phobia or panic disorder.3,4 Because treatment of PTSD with antidepressants and benzodiazepines often is ineffective,5 glucocorticoids may offer a new pharmacotherapy option. Glucocorticoids have been prescribed as prophylactic agents shortly after an acutely stressful event to prevent development of PTSD.4 Hydrocortisone is not FDA-approved to treat PTSD; informed consent, physician discretion, and close monitoring are emphasized.

Glucocorticoid use in mitigating PTSD symptom emergence is under investigation. Research suggests that just one acute dose of hydrocortisone might benefit patients prone to PTSD.3,4 Further study is needed to establish whether prescribing hydrocortisone is efficacious.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Jones T, Moller MD. Implications of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functioning in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2011;17(6):393-403.

2. Blundell J, Blaiss CA, Lagace DC, et al. Block of glucocorticoid synthesis during re-activation inhibits extinction of an established fear memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2011;95(4):453-460.

3. Putman P, Roelofs K. Effects of single cortisol administrations on human affect reviewed: coping with stress through adaptive regulation of automatic cognitive processing. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(4):439-448.

4. Miller MW, McKinney AE, Kanter FS, et al. Hydrocortisone suppression of the fear-potentiated startle response and posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(7):970-980.

5. Nin MS, Martinez LA, Pibiri F, et al. Neurosteroids reduce social isolation-induced behavioral deficits: a proposed link with neurosteroid-mediated upregulation of BDNF expression. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2011;2(73):1-12.

1. Jones T, Moller MD. Implications of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functioning in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2011;17(6):393-403.

2. Blundell J, Blaiss CA, Lagace DC, et al. Block of glucocorticoid synthesis during re-activation inhibits extinction of an established fear memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2011;95(4):453-460.

3. Putman P, Roelofs K. Effects of single cortisol administrations on human affect reviewed: coping with stress through adaptive regulation of automatic cognitive processing. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(4):439-448.

4. Miller MW, McKinney AE, Kanter FS, et al. Hydrocortisone suppression of the fear-potentiated startle response and posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(7):970-980.

5. Nin MS, Martinez LA, Pibiri F, et al. Neurosteroids reduce social isolation-induced behavioral deficits: a proposed link with neurosteroid-mediated upregulation of BDNF expression. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2011;2(73):1-12.

Using ECT

How best to engage patients in their psychiatric care

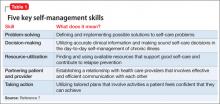

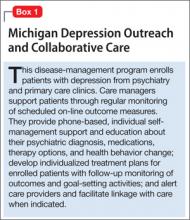

Providing patients and their families with information and education about their psychiatric illness is a central tenet of mental health care. Discussions about diagnostic impressions, treatment options, and the risks and benefits of interventions are customary. Additionally, patients and families often receive written material or referral to other information sources, including self-help books and a growing number of online resources. Although patient education remains a useful and expected element of good care, there is evidence that, alone, it is insufficient to change health behaviors.1

A growing body of literature and clinical experience suggests that self-management strategies complement patient education and improve treatment outcomes for patients with chronic illnesses, including psychiatric conditions.2,3 The Cochrane Collaboration describes patient education as “teaching or training of patients concerning their own health needs,” and self-management as “the individual’s ability to manage the symptoms, treatment, physical and psychosocial consequences and lifestyle changes inherent in living with a long-term disorder.”4

In this article, we review:

• characteristics of long-term care models

• literature supporting the benefits of self-management programs

• clinical initiatives illustrating important elements of self-management support

• opportunities and challenges faced by clinicians, patients, families, clinics, and healthcare systems implementing self-management programs.

Principles of self-management