User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Injustice can lead to treatment

In his editorial “New Year’s resolutions to help our patients” (From the Editor, Current Psychiatry, January 2010) Dr. Nasrallah decried criminalization of mentally ill individuals, which I agree, but I find that I can provide better treatment in the medium-security prison where I work part-time than in our community mental health clinic, which has been downsized. At the prison, we have a multidisciplinary staff, including primary care physicians. Patients keep their appointments and medication intake is monitored. We have enough time to see patients and adequate reimbursement for services. In fact, some patients do not want to leave because in prison they have a roof over their heads, adequate food, and competent health care.

Prisons are the only place in this country where people have the right to treatment. If only health care reform could replicate this outside of prison.

H. Steven Moffic, MD

Professor of psychiatry

Medical College of Wisconsin

Milwaukee, WI

In his editorial “New Year’s resolutions to help our patients” (From the Editor, Current Psychiatry, January 2010) Dr. Nasrallah decried criminalization of mentally ill individuals, which I agree, but I find that I can provide better treatment in the medium-security prison where I work part-time than in our community mental health clinic, which has been downsized. At the prison, we have a multidisciplinary staff, including primary care physicians. Patients keep their appointments and medication intake is monitored. We have enough time to see patients and adequate reimbursement for services. In fact, some patients do not want to leave because in prison they have a roof over their heads, adequate food, and competent health care.

Prisons are the only place in this country where people have the right to treatment. If only health care reform could replicate this outside of prison.

H. Steven Moffic, MD

Professor of psychiatry

Medical College of Wisconsin

Milwaukee, WI

In his editorial “New Year’s resolutions to help our patients” (From the Editor, Current Psychiatry, January 2010) Dr. Nasrallah decried criminalization of mentally ill individuals, which I agree, but I find that I can provide better treatment in the medium-security prison where I work part-time than in our community mental health clinic, which has been downsized. At the prison, we have a multidisciplinary staff, including primary care physicians. Patients keep their appointments and medication intake is monitored. We have enough time to see patients and adequate reimbursement for services. In fact, some patients do not want to leave because in prison they have a roof over their heads, adequate food, and competent health care.

Prisons are the only place in this country where people have the right to treatment. If only health care reform could replicate this outside of prison.

H. Steven Moffic, MD

Professor of psychiatry

Medical College of Wisconsin

Milwaukee, WI

Connecting the dots: Psychiatrists are virtuosos

“Connecting the dots” has emerged as a buzzword in our media and popular culture. This expression is a picturesque way to denote competence and implies an uncanny ability to recognize and integrate what appear to be multiple unrelated data points into an important, actionable pattern. An incisive decision or intervention often follows.

When I hear this expression, I contemplate the centrality of connecting the dots in psychiatric practice. In fact, it is a ubiquitous and indispensable approach to diagnosing and treating our patients. Psychiatrists are trained to be highly skilled at connecting not only one set of dots, but often a bewildering array of complex and disparate sets of dots related to each patient we evaluate and manage. It is impossible to arrive at an accurate psychiatric diagnosis and construct an appropriate and comprehensive treatment plan without connecting countless overt and covert dots related to interconnected pathologies across a patient’s brain, mind, and body. As part of the assessment, psychiatrists often presage the existence of dots that are not yet on their clinical radar and inquire about them with the patient and multiple corroborative sources. That’s what a good psychiatric interview and history taking usually entails.

Painting a diagnostic profile

The effective pursuit of connecting clinically relevant biologic, psychological, and social clinically relevant “dots” is an elegant mix of the art and science of psychiatry. By integrating a vast universe of clinical “dots,” (like an astronomer recognizing a galaxy in star-studded sky) psychiatrists can then identify their patients’ emotional topography, cognitive architecture, behavioral landscape, and psychodynamic geology. This enables us to formulate the patient’s clinical disorder across a matrix of biopsychosocial domains and paint a mosaic of “dots” representing predisposing, precipitating, perpetuating, and protective factors underpinning the patient’s psychopathology and illness course.

The emerging diagnostic profile of a patient leads to the next task of connecting another universe of dots related to launching a multifaceted treatment plan. An enormous number of dots have to be connected to determine a safe and effective treatment consistent with the patient’s demographics, lifestyle, social background, attitudes, beliefs, past and current medical history, family history, comorbidities, and laboratory data. Once those dots are connected and treatment begins, another phase of connecting the dots follows to monitor efficacy, safety, tolerability, and various clinical and functional outcomes related to treatment. Unless this phase is done expertly and meticulously, a patient’s remission, recovery, and return to wellness may be elusive and relapse or complications may develop.

We psychiatrists perform the Herculean task of connecting the dots many times a day on a heterogeneous group of patients with various psychopathologies, and we appear to do it effortlessly. This is a gratifying testimonial to the extensive and arduous years of training it takes to become skillful psychiatric physicians.

We always assume that other professionals also are connecting dots effectively in their respective areas of responsibility. Failure to connect the dots could result in a minor setback, or, in some cases, a catastrophic event. Aristotle defined “virtue” as excelling in one’s job. When we do our job well—diagnosing and healing mental, emotional, and behavioral brain disorders, preventing harm to self and others, and restoring wellness to ailing individuals—we psychiatrists are accomplishing “virtuous” acts and thus earn the privilege to be called “virtuosos.”

“Connecting the dots” has emerged as a buzzword in our media and popular culture. This expression is a picturesque way to denote competence and implies an uncanny ability to recognize and integrate what appear to be multiple unrelated data points into an important, actionable pattern. An incisive decision or intervention often follows.

When I hear this expression, I contemplate the centrality of connecting the dots in psychiatric practice. In fact, it is a ubiquitous and indispensable approach to diagnosing and treating our patients. Psychiatrists are trained to be highly skilled at connecting not only one set of dots, but often a bewildering array of complex and disparate sets of dots related to each patient we evaluate and manage. It is impossible to arrive at an accurate psychiatric diagnosis and construct an appropriate and comprehensive treatment plan without connecting countless overt and covert dots related to interconnected pathologies across a patient’s brain, mind, and body. As part of the assessment, psychiatrists often presage the existence of dots that are not yet on their clinical radar and inquire about them with the patient and multiple corroborative sources. That’s what a good psychiatric interview and history taking usually entails.

Painting a diagnostic profile

The effective pursuit of connecting clinically relevant biologic, psychological, and social clinically relevant “dots” is an elegant mix of the art and science of psychiatry. By integrating a vast universe of clinical “dots,” (like an astronomer recognizing a galaxy in star-studded sky) psychiatrists can then identify their patients’ emotional topography, cognitive architecture, behavioral landscape, and psychodynamic geology. This enables us to formulate the patient’s clinical disorder across a matrix of biopsychosocial domains and paint a mosaic of “dots” representing predisposing, precipitating, perpetuating, and protective factors underpinning the patient’s psychopathology and illness course.

The emerging diagnostic profile of a patient leads to the next task of connecting another universe of dots related to launching a multifaceted treatment plan. An enormous number of dots have to be connected to determine a safe and effective treatment consistent with the patient’s demographics, lifestyle, social background, attitudes, beliefs, past and current medical history, family history, comorbidities, and laboratory data. Once those dots are connected and treatment begins, another phase of connecting the dots follows to monitor efficacy, safety, tolerability, and various clinical and functional outcomes related to treatment. Unless this phase is done expertly and meticulously, a patient’s remission, recovery, and return to wellness may be elusive and relapse or complications may develop.

We psychiatrists perform the Herculean task of connecting the dots many times a day on a heterogeneous group of patients with various psychopathologies, and we appear to do it effortlessly. This is a gratifying testimonial to the extensive and arduous years of training it takes to become skillful psychiatric physicians.

We always assume that other professionals also are connecting dots effectively in their respective areas of responsibility. Failure to connect the dots could result in a minor setback, or, in some cases, a catastrophic event. Aristotle defined “virtue” as excelling in one’s job. When we do our job well—diagnosing and healing mental, emotional, and behavioral brain disorders, preventing harm to self and others, and restoring wellness to ailing individuals—we psychiatrists are accomplishing “virtuous” acts and thus earn the privilege to be called “virtuosos.”

“Connecting the dots” has emerged as a buzzword in our media and popular culture. This expression is a picturesque way to denote competence and implies an uncanny ability to recognize and integrate what appear to be multiple unrelated data points into an important, actionable pattern. An incisive decision or intervention often follows.

When I hear this expression, I contemplate the centrality of connecting the dots in psychiatric practice. In fact, it is a ubiquitous and indispensable approach to diagnosing and treating our patients. Psychiatrists are trained to be highly skilled at connecting not only one set of dots, but often a bewildering array of complex and disparate sets of dots related to each patient we evaluate and manage. It is impossible to arrive at an accurate psychiatric diagnosis and construct an appropriate and comprehensive treatment plan without connecting countless overt and covert dots related to interconnected pathologies across a patient’s brain, mind, and body. As part of the assessment, psychiatrists often presage the existence of dots that are not yet on their clinical radar and inquire about them with the patient and multiple corroborative sources. That’s what a good psychiatric interview and history taking usually entails.

Painting a diagnostic profile

The effective pursuit of connecting clinically relevant biologic, psychological, and social clinically relevant “dots” is an elegant mix of the art and science of psychiatry. By integrating a vast universe of clinical “dots,” (like an astronomer recognizing a galaxy in star-studded sky) psychiatrists can then identify their patients’ emotional topography, cognitive architecture, behavioral landscape, and psychodynamic geology. This enables us to formulate the patient’s clinical disorder across a matrix of biopsychosocial domains and paint a mosaic of “dots” representing predisposing, precipitating, perpetuating, and protective factors underpinning the patient’s psychopathology and illness course.

The emerging diagnostic profile of a patient leads to the next task of connecting another universe of dots related to launching a multifaceted treatment plan. An enormous number of dots have to be connected to determine a safe and effective treatment consistent with the patient’s demographics, lifestyle, social background, attitudes, beliefs, past and current medical history, family history, comorbidities, and laboratory data. Once those dots are connected and treatment begins, another phase of connecting the dots follows to monitor efficacy, safety, tolerability, and various clinical and functional outcomes related to treatment. Unless this phase is done expertly and meticulously, a patient’s remission, recovery, and return to wellness may be elusive and relapse or complications may develop.

We psychiatrists perform the Herculean task of connecting the dots many times a day on a heterogeneous group of patients with various psychopathologies, and we appear to do it effortlessly. This is a gratifying testimonial to the extensive and arduous years of training it takes to become skillful psychiatric physicians.

We always assume that other professionals also are connecting dots effectively in their respective areas of responsibility. Failure to connect the dots could result in a minor setback, or, in some cases, a catastrophic event. Aristotle defined “virtue” as excelling in one’s job. When we do our job well—diagnosing and healing mental, emotional, and behavioral brain disorders, preventing harm to self and others, and restoring wellness to ailing individuals—we psychiatrists are accomplishing “virtuous” acts and thus earn the privilege to be called “virtuosos.”

Psychosis in women: Consider midlife medical and psychological triggers

Dr. I, a 48-year-old university professor, is brought to the ER by her husband because she has developed an irrational fear of being chased by Nazis. The fears have become increasingly bizarre, her husband reports. She believes her Nazi persecutors are bandaging their arms and using wheelchairs to pretend to be disabled. When out with her husband, Dr. I points to people in wheelchairs, convinced they are after her, will kill her, and are incensed because she left Germany—her country of birth. Her husband brought her to the ER when she started to hear her persecutors addressing her in German at night.

Psychoses of unknown cause usually begin in late adolescence or early adulthood. Less frequently the onset occurs in later adulthood (age ≥40). Late-onset psychosis is much more prevalent in women than in men for reasons that are imperfectly understood.

When you are evaluating a midlife woman with first onset of psychosis, don’t assume an illness of unknown cause (bipolar disorder or schizophrenia) until after you have done a comprehensive search for triggers of her psychotic symptoms. After age 40, women are more likely than men to develop psychosis because of gender-specific medical and psychological precipitants.

Predisposing factors for psychosis

Psychosis is an emergent quality of structural and chemical changes in the brain. As such, it can be expected to surface during:

• brain reorganization or transition (adolescence, senescence, brain trauma, stroke, starvation, inflammation, or brain tumor)

• change in brain chemistry (flux in gonadal, thyroid, or adrenal hormone levels; electrolyte imbalance; fever; exposure to chemical substances; immune response).

Psychological stress impacting the brain via stress hormones also can predispose a person to psychosis.

Because some individuals are more prone than others to develop psychosis during brain alteration, chemical and structural changes in the brain are assumed to interact with genetic propensities to influence gene expression. Once a psychotic event has occurred, it is thought to sensitize the brain so that subsequent events emerge more readily.1

Schizophrenia—though not the only illness in which psychosis plays a role—is a prototype for psychotic illness, and several reported sex differences in this disorder are worth noting.2 The incidence of schizophrenia is approximately the same in both sexes, but women show a later age of onset—a paradox in that the brain develops at a faster pace in females and theoretically should reach the threshold for the first appearance of schizophrenia earlier. Women also require lower doses of antipsychotic medication to recover from an acute psychotic episode and to maintain remission, at least before menopause.3,4 Both of these differences can be explained as an effect of estrogen on a) gene expression5 and b) liver enzymes that metabolize antipsychotics.6

The estrogen hypothesis. Women show a tendency toward premenstrual and postpartum exacerbation of symptoms when estrogen levels are relatively low. These clinical observations, confirmed by some but not all studies, have led to the hypothesis that estrogens are neuroprotective7 and also protect against psychosis.8

Estrogen withdrawal in specific brain cells may release a cascade of events that over time can increase the severity of psychotic and cognitive symptoms. The reason for suspecting such effects is based on what we know about estrogenic effects on neurotransmitter, cognitive, and stress-induction pathways, and—more fundamentally—on neuronal growth and atrophy.

According to the estrogen hypothesis, women are—to some degree—protected against schizophrenia by their relatively high gonadal estrogen production between puberty and and menopause. Women lose this protection with the onset of perimenopausal estrogen fluctuation and decline, accounting for their second peak of illness onset after age 45.

Epidemiologic studies showing a second peak of schizophrenia onset in women (but not men) around the age of menopause support this hypothesis.9,10 Longitudinal outcomes for schizophrenia—which are better in women than in men during late adolescence or early adulthood11—gradually even out after the first 15 years of illness, suggesting that women’s advantage is lost at a time approximating menopause (Box 1).

The question, then, becomes: Is it only because of estrogen loss after age 40 that women become more prone to develop a psychotic illness? Other differences between the sexes that may play roles include immune function, low iron stores, sleep sufficiency, thyroid function, exposure to toxic substances (including therapeutic drugs), societal pressures to be slim while aging (Table), and the experience of stress.12

CASE CONTINUED

Exhausted and confused

Dr. I is a well-groomed, handsome woman, but she hardly speaks when interviewed, looking frightened and somewhat bewildered. She has never had a mental health problem, nor has anyone in her family. She agrees to stay in the hospital but is not sure why. She has slept no more than 1 or 2 hours in the last several days.

Her early history is unremarkable. She did well in school. After earning a PhD at the University of Leipzig, she and her husband immigrated to Canada. Both are university professors. They never decided not to have children, but children hadn’t come. Her menstrual periods stopped 2 years before admission. The question about children is the only 1 that elicits emotion in Dr. I. When I ask about it, tears come to her eyes as she shakes her head.

Her husband reports that she has not been eating well and has, in the last year, started to drink more alcohol than usual—3 to 4 drinks of whiskey a night. She does not smoke cigarettes, and her health generally is good. She uses no medications. Her husband describes their marital relationship as very close, although it has become strained in recent weeks because of her unreasonable fears. He admits that their work is always stressful; competition is fierce, with more and more deadlines and less and less leisure time. The couple has few friends and no hobbies.

Late-onset psychosis symptoms

In late-onset psychosis (after age 45), men appear to suffer substantially milder symptoms and spend less time hospitalized than women.13 Women with late-onset schizophrenia have more severe positive symptoms than men and fewer negative symptoms.14,15 Overall, patients with late-onset schizophrenia have a lower prevalence of looseness of associations and negative symptoms than those with earlier onset.16,17

In addition, individuals with schizophrenia who become ill in middle age have been reported to:

• show better neuropsychological performance (particularly in learning and abstraction/cognitive flexibility) than those with early onset

• possibly have larger thalamic volumes

• respond to lower antipsychotic doses.18

Auditory and visual hallucinations frequently are observed in patients with comorbid late-onset schizophrenia and auditory and visual impairment.16 Palmer et al18 reported no difference in family history of schizophrenia between early and late onset, but this is controversial. Convert et al16 note that most studies reveal a lower lifetime risk of schizophrenia in first-degree relatives of patients with late-onset than early-onset schizophrenia.

CASE CONTINUED

Medical workup

Dr. I’s physical exam is unremarkable. Her thyroid is not enlarged; there are no breast lumps. On mental status exam, her mood is flat. She is preoccupied with fears of the Nazis. Routine blood tests show slight anemia; fasting glucose levels are within normal range.

I give Dr. I zopiclone, 7.5 mg, to help her sleep. The next day she keeps to herself, eats very little, and appears disinterested in her surroundings. Nursing staff report that she often seems frightened. Dr. I asks to use the ward phone to call Germany but is told that she cannot make long distance calls from that phone. This seems to disturb her.

Differential diagnosis

Sensory impairment, substance abuse, and metabolic changes have been implicated in the appearance of psychosis in later life. More specific to women than men, however, are medical and psychiatric precipitants. These include autoimmune disease (and its treatment) and psychiatric disorders, as well as thyroid dysfunction, self-induced starvation (anorexia nervosa) and diet aids, substance use and abuse, insomnia, and iron deficiency (Table).

Autoimmune disease and treatment. Nearly 80% of patients with autoimmune disease are women, and these disorders (as well as their treatment) can manifest as psychosis. Corticosteroids have a well-documented history of triggering psychotic symptoms, which are twice as likely in women than in men. The incidence of severe psychosis while taking oral prednisone ranges from 1.6% to 50% and averages 5.7%. The average daily dose of corticosteroids for patients who develop psychosis is 59.5 mg/d.

Corticosteroid creams absorbed through skin as well as inhaled and intranasal corticosteroids in their more potent formulations can have systemic effects, including psychosis. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen also can trigger psychosis.19

Psychiatric disorders. Posttraumatic stress disorder with psychotic symptoms may overlap with categories such as psychogenic psychoses, hysterical psychoses, nonaffective remitting psychoses, acute brief psychoses, reactive psychoses, acute and transient psychoses, and bouffées délirantes (in France, the name for transient psychotic reactions).20 Consider these female-predominant conditions in the differential diagnosis, along with micropsychotic episodes in borderline personality disorder, in which the predominance of women is 3:1.

Medical treatment for depression and anxiety also can lead to psychotic symptoms through individual susceptibility to the action of specific drugs or through withdrawal effects.

Clinical assessment

Question all women presenting with psychosis about eating habits and diet pills, and check for hypokalemia and hypocalcemia to rule out starvation effects and reactions to stimulants. Also ask about inhalants, and examine for anemia and thyroid dysfunction. Consider all medications as having the potential to trigger psychotic symptoms.

A family history of illness is important, with a focus on autoimmune disorder and its treatment. A thorough psychiatric history is crucial and needs to include assessment of sleep, mood, and relationships with attachment figures. Do not assume illnesses of unknown cause (bipolar disorder or schizophrenia) until after a comprehensive search for precipitants of psychotic symptoms.

CASE CONTINUED

Guilty feelings

To address her delusions, I start Dr. I on risperidone, 2 mg at bedtime. She goes home for the weekend, and her husband reports that she slept throughout the visit. When she returns, she spends a lot of time in bed but is more communicative.

When I ask Dr. I whether she has called Germany, she says she called her recently widowed father. Dr. I begins to cry when talking of her mother, and tells the nurse she feels guilty for not visiting for the last few years. When her mother died 6 months ago, Dr. I had not seen her in 4 years.

Her fears remit with risperidone, maintained at 2 mg/d, but Dr. I remains depressed and responds slowly to treatment with citalopram, 20 mg/d, and supportive therapy. Her final diagnosis is mood disorder with psychotic features.

Treatment

When treating women with late-onset psychosis, remove all potential triggers and address underlying illness. Cognitive therapy targeting specific symptoms is useful; antipsychotics probably will be necessary. Age-related physiologic changes make older persons more sensitive to the therapeutic and toxic effects of antipsychotics.

Estrogen therapy? Women suffering from schizophrenia show significantly lower estrogen levels than the general population of women, and they experience first-onset or recurrence of a psychotic episode significantly more often in low estrogen phases of the cycle. Estrogens have therefore been postulated to constitute a protective factor against psychosis, which means perimenopause is an at-risk period.21 Although evidence is limited, preliminary studies have found beneficial effects from short-term, off-label use of estrogen therapy in women with psychotic illness (Box 2).

Because continuous use of estrogen plus progestin has been associated with an increased risk of adverse effects,22 off-label use of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) also is being investigated in women with schizophrenia. SERMs act as tissue-specific estrogen agonists and antagonists because they can either inhibit or enhance estrogen-induced activation of estrogen response element-containing genes.23

Wong et al24 used a crossover design to compare the SERM raloxifene with placebo as adjunctive treatment for 6 postmenopausal women with schizophrenia. Each woman received 8 weeks of raloxifene, 60 mg/d, and 8 weeks of placebo. Three began with placebo and 3 with raloxifene.

Verbal memory was measured weekly with the California Verbal Learning Test, using 5 memory trials, free and cued short-delay recall, and long-delay recall. At baseline, the participants had lower scores than older adults in the general population. Eight weeks of placebo improved scores somewhat, suggesting a practice effect. Eight weeks of raloxifene improved cognitive scores to a level similar to that of schizophrenia-free subjects. After 16 weeks, however, cognitive scores in the 2 groups were indistinguishable.

At present I do not recommend estrogen for women with late-onset schizophrenia because the risk is too high and raloxifene does not enter the brain sufficiently to be a valuable cognitive enhancer. Novel SERMs with more specific efficacy for improving cognitive function may prove useful in the future,25 however, as may phytoestrogens. Adjunctive hormone modulation is a promising area of gender-specific treatment for serious mental illness.26

CASE CONCLUSION

Gradually improving

Dr. I’s depression was triggered by her mother’s death and regrets about not visiting and not being a mother. The content of her delusions was related to her guilt about not having returned to Germany; the delusions were probably triggered by depression, alcohol intake, her relative hypoestrogenic state, stress at work, lack of social supports, and dependence on her husband.

Over the next few years, Dr. I is maintained on a low dose of risperidone (reduced from 2 mg/d to 1 mg/d) and citalopram (reduced from 20 mg/d to 10 mg/d). She becomes increasingly engaged in supportive dynamic therapy, and her symptoms gradually improve.

BOTTOM LINE

Psychosis onset in midlife is mostly a female phenomenon because a perimenopausal estrogen decline increases women’s susceptibility. Seek specific triggers such as medical illness or response to a drug before assuming an illness of unknown cause such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. Cognitive therapy targeting specific symptoms is useful; antipsychotics probably will be necessary.

Related Resources

• Women and psychosis: A guide for women and their families. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. University of Toronto. www.camh.net/About_Addiction_Mental_ Health/Mental_Health_Information/Women_Psychosis.

• Seeman MV. Women and psychosis. www.medscape.com/ viewarticle/408912.

• Chattopadhyay S. Estrogen and schizophrenia: Any link? The Internet Journal of Mental Health. 2004;2(1). www.ispub. com/journal/the_internet_journal_of_mental_health.html.

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa Prednisone • Deltasone,

Estradiol • Estrace, Orasone, others

Estrofem, others Raloxifene • Evista

Estradiol transdermal • Risperidone • Risperdal

Estraderm , Climara, others

Methylphenidate • Concerta,

Ritalin, others

Disclosure

Dr. Seeman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Post RM. Kindling and sensitization as models for affective episode recurrence, cyclicity, and tolerance phenomena. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2007;31:858-873.

2. Seeman MV. Gender differences in schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 1982;27:107-112.

3. Seeman MV. Interaction of sex, age, and neuroleptic dose. Comp Psychiatry. 1983;24:125-128.

4. Usall J, Suarez D, Haro JM, and the SOHO Study Group. Gender differences in response to antipsychotic treatment in outpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2007;153: 225-231.

5. Hare E, Glahn DC, Dassori A, et al. Heritability of age of onset of psychosis in schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009 Apr 6 [Epub ahead of print].

6. Seeman MV. Gender differences in the prescribing of antipsychotic drugs. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1324-1333.

7. Marin R, Guerra B, Alonso R, et al. Estrogen activates classical and alternative mechanisms to orchestrate neuroprotection. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2005;2:287-301.

8. Seeman MV, Lang M. The role of estrogens in schizophrenia gender differences. Schizophr Bull. 1990;16:185-194.

9. Castle DJ, Abel K, Takei N, et al. Gender differences in schizophrenia: hormonal effect or subtypes? Schizophr Bull. 1995;21:1-12.

10. Häfner H, an der Heiden W. Epidemiology of schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 1997;42:139-151.

11. Grossman LS, Harrow M, Rosen C, et al. Sex differences in schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders: a 20-year longitudinal study of psychosis and recovery. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49:523-529.

12. Kajantie E, Phillips DI. The effects of sex and hormonal status on the physiological response to acute psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:151-178.

13. Riecher-Rössler A, Löffler W, Munk-Jörgensen P. What do we really know about late-onset schizophrenia? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;247:195-208.

14. Lindamer LA, Lohr JB, Harris MJ, et al. Gender-related clinical differences in older patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:61-67.

15. Seeman MV. Does menopause intensify symptoms in schizophrenia? In: Lewis-Hall F, Williams TS, Panetta JA, et al, eds. Psychiatric illness in women: emerging treatments and research. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2002:239-248.

16. Convert H, Védie C, Paulin P. [Late-onset schizophrenia or chronic delusion]. Encephale. 2006;32:957-961.

17. Sato T, Bottlender R, Schröter A, et al. Psychopathology of early-onset versus late-onset schizophrenia revisited: an observation of 473 neuroleptic-naive patients before and after first-admission treatments. Schizophr Res. 2004;67:175-183.

18. Palmer BW, McClure FS, Jeste DV. Schizophrenia in late life: findings challenge traditional concepts. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2001;9:51-58.

19. Weiss DB, Dyrud J, House RM, et al. Psychiatric manifestations of autoimmune disorders. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2005;7:413-417.

20. Castagnini A, Bertelsen A, Munk-Jorgensen P, et al. The relationship of reactive psychosis and ICD-10 acute and transient psychotic disorders: evidence from a case register-based comparison. Psychopathology. 2007;40:47-53.

21. Huber TJ, Rollnik J, Wilhelms J, et al. Estradiol levels in psychotic disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2001;26: 27-35.

22. Heiss G, Wallace R, Anderson G, et al, for the WHI Investigators. Health risks and benefits 3 years after stopping randomized treatment with estrogen and progestin. JAMA. 2008;299(9):1036-1045.

23. Doncarlos LL, Azcoitia I, Garcia-Segura LM. Neuroprotective actions of selective estrogen receptor modulators. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009 May 15 [Epub ahead of print].

24. Wong J, Seeman MV, Shapiro H. Case report: raloxifene in postmenopausal women with psychosis: preliminary findings. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11(6):697-698.

25. Ye L, Chan MY, Leung LK. The soy isoflavone genistein induces estrogen synthesis in an extragonadal pathway. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;302:73-80.

26. Kulkarni J, Gurvich C, Gilbert H, et al. Hormone modulation: a novel therapeutic approach for women with severe mental illness. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2008;42:83-88.

Dr. I, a 48-year-old university professor, is brought to the ER by her husband because she has developed an irrational fear of being chased by Nazis. The fears have become increasingly bizarre, her husband reports. She believes her Nazi persecutors are bandaging their arms and using wheelchairs to pretend to be disabled. When out with her husband, Dr. I points to people in wheelchairs, convinced they are after her, will kill her, and are incensed because she left Germany—her country of birth. Her husband brought her to the ER when she started to hear her persecutors addressing her in German at night.

Psychoses of unknown cause usually begin in late adolescence or early adulthood. Less frequently the onset occurs in later adulthood (age ≥40). Late-onset psychosis is much more prevalent in women than in men for reasons that are imperfectly understood.

When you are evaluating a midlife woman with first onset of psychosis, don’t assume an illness of unknown cause (bipolar disorder or schizophrenia) until after you have done a comprehensive search for triggers of her psychotic symptoms. After age 40, women are more likely than men to develop psychosis because of gender-specific medical and psychological precipitants.

Predisposing factors for psychosis

Psychosis is an emergent quality of structural and chemical changes in the brain. As such, it can be expected to surface during:

• brain reorganization or transition (adolescence, senescence, brain trauma, stroke, starvation, inflammation, or brain tumor)

• change in brain chemistry (flux in gonadal, thyroid, or adrenal hormone levels; electrolyte imbalance; fever; exposure to chemical substances; immune response).

Psychological stress impacting the brain via stress hormones also can predispose a person to psychosis.

Because some individuals are more prone than others to develop psychosis during brain alteration, chemical and structural changes in the brain are assumed to interact with genetic propensities to influence gene expression. Once a psychotic event has occurred, it is thought to sensitize the brain so that subsequent events emerge more readily.1

Schizophrenia—though not the only illness in which psychosis plays a role—is a prototype for psychotic illness, and several reported sex differences in this disorder are worth noting.2 The incidence of schizophrenia is approximately the same in both sexes, but women show a later age of onset—a paradox in that the brain develops at a faster pace in females and theoretically should reach the threshold for the first appearance of schizophrenia earlier. Women also require lower doses of antipsychotic medication to recover from an acute psychotic episode and to maintain remission, at least before menopause.3,4 Both of these differences can be explained as an effect of estrogen on a) gene expression5 and b) liver enzymes that metabolize antipsychotics.6

The estrogen hypothesis. Women show a tendency toward premenstrual and postpartum exacerbation of symptoms when estrogen levels are relatively low. These clinical observations, confirmed by some but not all studies, have led to the hypothesis that estrogens are neuroprotective7 and also protect against psychosis.8

Estrogen withdrawal in specific brain cells may release a cascade of events that over time can increase the severity of psychotic and cognitive symptoms. The reason for suspecting such effects is based on what we know about estrogenic effects on neurotransmitter, cognitive, and stress-induction pathways, and—more fundamentally—on neuronal growth and atrophy.

According to the estrogen hypothesis, women are—to some degree—protected against schizophrenia by their relatively high gonadal estrogen production between puberty and and menopause. Women lose this protection with the onset of perimenopausal estrogen fluctuation and decline, accounting for their second peak of illness onset after age 45.

Epidemiologic studies showing a second peak of schizophrenia onset in women (but not men) around the age of menopause support this hypothesis.9,10 Longitudinal outcomes for schizophrenia—which are better in women than in men during late adolescence or early adulthood11—gradually even out after the first 15 years of illness, suggesting that women’s advantage is lost at a time approximating menopause (Box 1).

The question, then, becomes: Is it only because of estrogen loss after age 40 that women become more prone to develop a psychotic illness? Other differences between the sexes that may play roles include immune function, low iron stores, sleep sufficiency, thyroid function, exposure to toxic substances (including therapeutic drugs), societal pressures to be slim while aging (Table), and the experience of stress.12

CASE CONTINUED

Exhausted and confused

Dr. I is a well-groomed, handsome woman, but she hardly speaks when interviewed, looking frightened and somewhat bewildered. She has never had a mental health problem, nor has anyone in her family. She agrees to stay in the hospital but is not sure why. She has slept no more than 1 or 2 hours in the last several days.

Her early history is unremarkable. She did well in school. After earning a PhD at the University of Leipzig, she and her husband immigrated to Canada. Both are university professors. They never decided not to have children, but children hadn’t come. Her menstrual periods stopped 2 years before admission. The question about children is the only 1 that elicits emotion in Dr. I. When I ask about it, tears come to her eyes as she shakes her head.

Her husband reports that she has not been eating well and has, in the last year, started to drink more alcohol than usual—3 to 4 drinks of whiskey a night. She does not smoke cigarettes, and her health generally is good. She uses no medications. Her husband describes their marital relationship as very close, although it has become strained in recent weeks because of her unreasonable fears. He admits that their work is always stressful; competition is fierce, with more and more deadlines and less and less leisure time. The couple has few friends and no hobbies.

Late-onset psychosis symptoms

In late-onset psychosis (after age 45), men appear to suffer substantially milder symptoms and spend less time hospitalized than women.13 Women with late-onset schizophrenia have more severe positive symptoms than men and fewer negative symptoms.14,15 Overall, patients with late-onset schizophrenia have a lower prevalence of looseness of associations and negative symptoms than those with earlier onset.16,17

In addition, individuals with schizophrenia who become ill in middle age have been reported to:

• show better neuropsychological performance (particularly in learning and abstraction/cognitive flexibility) than those with early onset

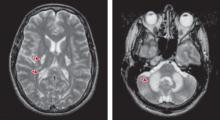

• possibly have larger thalamic volumes

• respond to lower antipsychotic doses.18

Auditory and visual hallucinations frequently are observed in patients with comorbid late-onset schizophrenia and auditory and visual impairment.16 Palmer et al18 reported no difference in family history of schizophrenia between early and late onset, but this is controversial. Convert et al16 note that most studies reveal a lower lifetime risk of schizophrenia in first-degree relatives of patients with late-onset than early-onset schizophrenia.

CASE CONTINUED

Medical workup

Dr. I’s physical exam is unremarkable. Her thyroid is not enlarged; there are no breast lumps. On mental status exam, her mood is flat. She is preoccupied with fears of the Nazis. Routine blood tests show slight anemia; fasting glucose levels are within normal range.

I give Dr. I zopiclone, 7.5 mg, to help her sleep. The next day she keeps to herself, eats very little, and appears disinterested in her surroundings. Nursing staff report that she often seems frightened. Dr. I asks to use the ward phone to call Germany but is told that she cannot make long distance calls from that phone. This seems to disturb her.

Differential diagnosis

Sensory impairment, substance abuse, and metabolic changes have been implicated in the appearance of psychosis in later life. More specific to women than men, however, are medical and psychiatric precipitants. These include autoimmune disease (and its treatment) and psychiatric disorders, as well as thyroid dysfunction, self-induced starvation (anorexia nervosa) and diet aids, substance use and abuse, insomnia, and iron deficiency (Table).

Autoimmune disease and treatment. Nearly 80% of patients with autoimmune disease are women, and these disorders (as well as their treatment) can manifest as psychosis. Corticosteroids have a well-documented history of triggering psychotic symptoms, which are twice as likely in women than in men. The incidence of severe psychosis while taking oral prednisone ranges from 1.6% to 50% and averages 5.7%. The average daily dose of corticosteroids for patients who develop psychosis is 59.5 mg/d.

Corticosteroid creams absorbed through skin as well as inhaled and intranasal corticosteroids in their more potent formulations can have systemic effects, including psychosis. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen also can trigger psychosis.19

Psychiatric disorders. Posttraumatic stress disorder with psychotic symptoms may overlap with categories such as psychogenic psychoses, hysterical psychoses, nonaffective remitting psychoses, acute brief psychoses, reactive psychoses, acute and transient psychoses, and bouffées délirantes (in France, the name for transient psychotic reactions).20 Consider these female-predominant conditions in the differential diagnosis, along with micropsychotic episodes in borderline personality disorder, in which the predominance of women is 3:1.

Medical treatment for depression and anxiety also can lead to psychotic symptoms through individual susceptibility to the action of specific drugs or through withdrawal effects.

Clinical assessment

Question all women presenting with psychosis about eating habits and diet pills, and check for hypokalemia and hypocalcemia to rule out starvation effects and reactions to stimulants. Also ask about inhalants, and examine for anemia and thyroid dysfunction. Consider all medications as having the potential to trigger psychotic symptoms.

A family history of illness is important, with a focus on autoimmune disorder and its treatment. A thorough psychiatric history is crucial and needs to include assessment of sleep, mood, and relationships with attachment figures. Do not assume illnesses of unknown cause (bipolar disorder or schizophrenia) until after a comprehensive search for precipitants of psychotic symptoms.

CASE CONTINUED

Guilty feelings

To address her delusions, I start Dr. I on risperidone, 2 mg at bedtime. She goes home for the weekend, and her husband reports that she slept throughout the visit. When she returns, she spends a lot of time in bed but is more communicative.

When I ask Dr. I whether she has called Germany, she says she called her recently widowed father. Dr. I begins to cry when talking of her mother, and tells the nurse she feels guilty for not visiting for the last few years. When her mother died 6 months ago, Dr. I had not seen her in 4 years.

Her fears remit with risperidone, maintained at 2 mg/d, but Dr. I remains depressed and responds slowly to treatment with citalopram, 20 mg/d, and supportive therapy. Her final diagnosis is mood disorder with psychotic features.

Treatment

When treating women with late-onset psychosis, remove all potential triggers and address underlying illness. Cognitive therapy targeting specific symptoms is useful; antipsychotics probably will be necessary. Age-related physiologic changes make older persons more sensitive to the therapeutic and toxic effects of antipsychotics.

Estrogen therapy? Women suffering from schizophrenia show significantly lower estrogen levels than the general population of women, and they experience first-onset or recurrence of a psychotic episode significantly more often in low estrogen phases of the cycle. Estrogens have therefore been postulated to constitute a protective factor against psychosis, which means perimenopause is an at-risk period.21 Although evidence is limited, preliminary studies have found beneficial effects from short-term, off-label use of estrogen therapy in women with psychotic illness (Box 2).

Because continuous use of estrogen plus progestin has been associated with an increased risk of adverse effects,22 off-label use of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) also is being investigated in women with schizophrenia. SERMs act as tissue-specific estrogen agonists and antagonists because they can either inhibit or enhance estrogen-induced activation of estrogen response element-containing genes.23

Wong et al24 used a crossover design to compare the SERM raloxifene with placebo as adjunctive treatment for 6 postmenopausal women with schizophrenia. Each woman received 8 weeks of raloxifene, 60 mg/d, and 8 weeks of placebo. Three began with placebo and 3 with raloxifene.

Verbal memory was measured weekly with the California Verbal Learning Test, using 5 memory trials, free and cued short-delay recall, and long-delay recall. At baseline, the participants had lower scores than older adults in the general population. Eight weeks of placebo improved scores somewhat, suggesting a practice effect. Eight weeks of raloxifene improved cognitive scores to a level similar to that of schizophrenia-free subjects. After 16 weeks, however, cognitive scores in the 2 groups were indistinguishable.

At present I do not recommend estrogen for women with late-onset schizophrenia because the risk is too high and raloxifene does not enter the brain sufficiently to be a valuable cognitive enhancer. Novel SERMs with more specific efficacy for improving cognitive function may prove useful in the future,25 however, as may phytoestrogens. Adjunctive hormone modulation is a promising area of gender-specific treatment for serious mental illness.26

CASE CONCLUSION

Gradually improving

Dr. I’s depression was triggered by her mother’s death and regrets about not visiting and not being a mother. The content of her delusions was related to her guilt about not having returned to Germany; the delusions were probably triggered by depression, alcohol intake, her relative hypoestrogenic state, stress at work, lack of social supports, and dependence on her husband.

Over the next few years, Dr. I is maintained on a low dose of risperidone (reduced from 2 mg/d to 1 mg/d) and citalopram (reduced from 20 mg/d to 10 mg/d). She becomes increasingly engaged in supportive dynamic therapy, and her symptoms gradually improve.

BOTTOM LINE

Psychosis onset in midlife is mostly a female phenomenon because a perimenopausal estrogen decline increases women’s susceptibility. Seek specific triggers such as medical illness or response to a drug before assuming an illness of unknown cause such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. Cognitive therapy targeting specific symptoms is useful; antipsychotics probably will be necessary.

Related Resources

• Women and psychosis: A guide for women and their families. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. University of Toronto. www.camh.net/About_Addiction_Mental_ Health/Mental_Health_Information/Women_Psychosis.

• Seeman MV. Women and psychosis. www.medscape.com/ viewarticle/408912.

• Chattopadhyay S. Estrogen and schizophrenia: Any link? The Internet Journal of Mental Health. 2004;2(1). www.ispub. com/journal/the_internet_journal_of_mental_health.html.

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa Prednisone • Deltasone,

Estradiol • Estrace, Orasone, others

Estrofem, others Raloxifene • Evista

Estradiol transdermal • Risperidone • Risperdal

Estraderm , Climara, others

Methylphenidate • Concerta,

Ritalin, others

Disclosure

Dr. Seeman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. I, a 48-year-old university professor, is brought to the ER by her husband because she has developed an irrational fear of being chased by Nazis. The fears have become increasingly bizarre, her husband reports. She believes her Nazi persecutors are bandaging their arms and using wheelchairs to pretend to be disabled. When out with her husband, Dr. I points to people in wheelchairs, convinced they are after her, will kill her, and are incensed because she left Germany—her country of birth. Her husband brought her to the ER when she started to hear her persecutors addressing her in German at night.

Psychoses of unknown cause usually begin in late adolescence or early adulthood. Less frequently the onset occurs in later adulthood (age ≥40). Late-onset psychosis is much more prevalent in women than in men for reasons that are imperfectly understood.

When you are evaluating a midlife woman with first onset of psychosis, don’t assume an illness of unknown cause (bipolar disorder or schizophrenia) until after you have done a comprehensive search for triggers of her psychotic symptoms. After age 40, women are more likely than men to develop psychosis because of gender-specific medical and psychological precipitants.

Predisposing factors for psychosis

Psychosis is an emergent quality of structural and chemical changes in the brain. As such, it can be expected to surface during:

• brain reorganization or transition (adolescence, senescence, brain trauma, stroke, starvation, inflammation, or brain tumor)

• change in brain chemistry (flux in gonadal, thyroid, or adrenal hormone levels; electrolyte imbalance; fever; exposure to chemical substances; immune response).

Psychological stress impacting the brain via stress hormones also can predispose a person to psychosis.

Because some individuals are more prone than others to develop psychosis during brain alteration, chemical and structural changes in the brain are assumed to interact with genetic propensities to influence gene expression. Once a psychotic event has occurred, it is thought to sensitize the brain so that subsequent events emerge more readily.1

Schizophrenia—though not the only illness in which psychosis plays a role—is a prototype for psychotic illness, and several reported sex differences in this disorder are worth noting.2 The incidence of schizophrenia is approximately the same in both sexes, but women show a later age of onset—a paradox in that the brain develops at a faster pace in females and theoretically should reach the threshold for the first appearance of schizophrenia earlier. Women also require lower doses of antipsychotic medication to recover from an acute psychotic episode and to maintain remission, at least before menopause.3,4 Both of these differences can be explained as an effect of estrogen on a) gene expression5 and b) liver enzymes that metabolize antipsychotics.6

The estrogen hypothesis. Women show a tendency toward premenstrual and postpartum exacerbation of symptoms when estrogen levels are relatively low. These clinical observations, confirmed by some but not all studies, have led to the hypothesis that estrogens are neuroprotective7 and also protect against psychosis.8

Estrogen withdrawal in specific brain cells may release a cascade of events that over time can increase the severity of psychotic and cognitive symptoms. The reason for suspecting such effects is based on what we know about estrogenic effects on neurotransmitter, cognitive, and stress-induction pathways, and—more fundamentally—on neuronal growth and atrophy.

According to the estrogen hypothesis, women are—to some degree—protected against schizophrenia by their relatively high gonadal estrogen production between puberty and and menopause. Women lose this protection with the onset of perimenopausal estrogen fluctuation and decline, accounting for their second peak of illness onset after age 45.

Epidemiologic studies showing a second peak of schizophrenia onset in women (but not men) around the age of menopause support this hypothesis.9,10 Longitudinal outcomes for schizophrenia—which are better in women than in men during late adolescence or early adulthood11—gradually even out after the first 15 years of illness, suggesting that women’s advantage is lost at a time approximating menopause (Box 1).

The question, then, becomes: Is it only because of estrogen loss after age 40 that women become more prone to develop a psychotic illness? Other differences between the sexes that may play roles include immune function, low iron stores, sleep sufficiency, thyroid function, exposure to toxic substances (including therapeutic drugs), societal pressures to be slim while aging (Table), and the experience of stress.12

CASE CONTINUED

Exhausted and confused

Dr. I is a well-groomed, handsome woman, but she hardly speaks when interviewed, looking frightened and somewhat bewildered. She has never had a mental health problem, nor has anyone in her family. She agrees to stay in the hospital but is not sure why. She has slept no more than 1 or 2 hours in the last several days.

Her early history is unremarkable. She did well in school. After earning a PhD at the University of Leipzig, she and her husband immigrated to Canada. Both are university professors. They never decided not to have children, but children hadn’t come. Her menstrual periods stopped 2 years before admission. The question about children is the only 1 that elicits emotion in Dr. I. When I ask about it, tears come to her eyes as she shakes her head.

Her husband reports that she has not been eating well and has, in the last year, started to drink more alcohol than usual—3 to 4 drinks of whiskey a night. She does not smoke cigarettes, and her health generally is good. She uses no medications. Her husband describes their marital relationship as very close, although it has become strained in recent weeks because of her unreasonable fears. He admits that their work is always stressful; competition is fierce, with more and more deadlines and less and less leisure time. The couple has few friends and no hobbies.

Late-onset psychosis symptoms

In late-onset psychosis (after age 45), men appear to suffer substantially milder symptoms and spend less time hospitalized than women.13 Women with late-onset schizophrenia have more severe positive symptoms than men and fewer negative symptoms.14,15 Overall, patients with late-onset schizophrenia have a lower prevalence of looseness of associations and negative symptoms than those with earlier onset.16,17

In addition, individuals with schizophrenia who become ill in middle age have been reported to:

• show better neuropsychological performance (particularly in learning and abstraction/cognitive flexibility) than those with early onset

• possibly have larger thalamic volumes

• respond to lower antipsychotic doses.18

Auditory and visual hallucinations frequently are observed in patients with comorbid late-onset schizophrenia and auditory and visual impairment.16 Palmer et al18 reported no difference in family history of schizophrenia between early and late onset, but this is controversial. Convert et al16 note that most studies reveal a lower lifetime risk of schizophrenia in first-degree relatives of patients with late-onset than early-onset schizophrenia.

CASE CONTINUED

Medical workup

Dr. I’s physical exam is unremarkable. Her thyroid is not enlarged; there are no breast lumps. On mental status exam, her mood is flat. She is preoccupied with fears of the Nazis. Routine blood tests show slight anemia; fasting glucose levels are within normal range.

I give Dr. I zopiclone, 7.5 mg, to help her sleep. The next day she keeps to herself, eats very little, and appears disinterested in her surroundings. Nursing staff report that she often seems frightened. Dr. I asks to use the ward phone to call Germany but is told that she cannot make long distance calls from that phone. This seems to disturb her.

Differential diagnosis

Sensory impairment, substance abuse, and metabolic changes have been implicated in the appearance of psychosis in later life. More specific to women than men, however, are medical and psychiatric precipitants. These include autoimmune disease (and its treatment) and psychiatric disorders, as well as thyroid dysfunction, self-induced starvation (anorexia nervosa) and diet aids, substance use and abuse, insomnia, and iron deficiency (Table).

Autoimmune disease and treatment. Nearly 80% of patients with autoimmune disease are women, and these disorders (as well as their treatment) can manifest as psychosis. Corticosteroids have a well-documented history of triggering psychotic symptoms, which are twice as likely in women than in men. The incidence of severe psychosis while taking oral prednisone ranges from 1.6% to 50% and averages 5.7%. The average daily dose of corticosteroids for patients who develop psychosis is 59.5 mg/d.

Corticosteroid creams absorbed through skin as well as inhaled and intranasal corticosteroids in their more potent formulations can have systemic effects, including psychosis. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen also can trigger psychosis.19

Psychiatric disorders. Posttraumatic stress disorder with psychotic symptoms may overlap with categories such as psychogenic psychoses, hysterical psychoses, nonaffective remitting psychoses, acute brief psychoses, reactive psychoses, acute and transient psychoses, and bouffées délirantes (in France, the name for transient psychotic reactions).20 Consider these female-predominant conditions in the differential diagnosis, along with micropsychotic episodes in borderline personality disorder, in which the predominance of women is 3:1.

Medical treatment for depression and anxiety also can lead to psychotic symptoms through individual susceptibility to the action of specific drugs or through withdrawal effects.

Clinical assessment

Question all women presenting with psychosis about eating habits and diet pills, and check for hypokalemia and hypocalcemia to rule out starvation effects and reactions to stimulants. Also ask about inhalants, and examine for anemia and thyroid dysfunction. Consider all medications as having the potential to trigger psychotic symptoms.

A family history of illness is important, with a focus on autoimmune disorder and its treatment. A thorough psychiatric history is crucial and needs to include assessment of sleep, mood, and relationships with attachment figures. Do not assume illnesses of unknown cause (bipolar disorder or schizophrenia) until after a comprehensive search for precipitants of psychotic symptoms.

CASE CONTINUED

Guilty feelings

To address her delusions, I start Dr. I on risperidone, 2 mg at bedtime. She goes home for the weekend, and her husband reports that she slept throughout the visit. When she returns, she spends a lot of time in bed but is more communicative.

When I ask Dr. I whether she has called Germany, she says she called her recently widowed father. Dr. I begins to cry when talking of her mother, and tells the nurse she feels guilty for not visiting for the last few years. When her mother died 6 months ago, Dr. I had not seen her in 4 years.

Her fears remit with risperidone, maintained at 2 mg/d, but Dr. I remains depressed and responds slowly to treatment with citalopram, 20 mg/d, and supportive therapy. Her final diagnosis is mood disorder with psychotic features.

Treatment

When treating women with late-onset psychosis, remove all potential triggers and address underlying illness. Cognitive therapy targeting specific symptoms is useful; antipsychotics probably will be necessary. Age-related physiologic changes make older persons more sensitive to the therapeutic and toxic effects of antipsychotics.

Estrogen therapy? Women suffering from schizophrenia show significantly lower estrogen levels than the general population of women, and they experience first-onset or recurrence of a psychotic episode significantly more often in low estrogen phases of the cycle. Estrogens have therefore been postulated to constitute a protective factor against psychosis, which means perimenopause is an at-risk period.21 Although evidence is limited, preliminary studies have found beneficial effects from short-term, off-label use of estrogen therapy in women with psychotic illness (Box 2).

Because continuous use of estrogen plus progestin has been associated with an increased risk of adverse effects,22 off-label use of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) also is being investigated in women with schizophrenia. SERMs act as tissue-specific estrogen agonists and antagonists because they can either inhibit or enhance estrogen-induced activation of estrogen response element-containing genes.23

Wong et al24 used a crossover design to compare the SERM raloxifene with placebo as adjunctive treatment for 6 postmenopausal women with schizophrenia. Each woman received 8 weeks of raloxifene, 60 mg/d, and 8 weeks of placebo. Three began with placebo and 3 with raloxifene.

Verbal memory was measured weekly with the California Verbal Learning Test, using 5 memory trials, free and cued short-delay recall, and long-delay recall. At baseline, the participants had lower scores than older adults in the general population. Eight weeks of placebo improved scores somewhat, suggesting a practice effect. Eight weeks of raloxifene improved cognitive scores to a level similar to that of schizophrenia-free subjects. After 16 weeks, however, cognitive scores in the 2 groups were indistinguishable.

At present I do not recommend estrogen for women with late-onset schizophrenia because the risk is too high and raloxifene does not enter the brain sufficiently to be a valuable cognitive enhancer. Novel SERMs with more specific efficacy for improving cognitive function may prove useful in the future,25 however, as may phytoestrogens. Adjunctive hormone modulation is a promising area of gender-specific treatment for serious mental illness.26

CASE CONCLUSION

Gradually improving

Dr. I’s depression was triggered by her mother’s death and regrets about not visiting and not being a mother. The content of her delusions was related to her guilt about not having returned to Germany; the delusions were probably triggered by depression, alcohol intake, her relative hypoestrogenic state, stress at work, lack of social supports, and dependence on her husband.

Over the next few years, Dr. I is maintained on a low dose of risperidone (reduced from 2 mg/d to 1 mg/d) and citalopram (reduced from 20 mg/d to 10 mg/d). She becomes increasingly engaged in supportive dynamic therapy, and her symptoms gradually improve.

BOTTOM LINE

Psychosis onset in midlife is mostly a female phenomenon because a perimenopausal estrogen decline increases women’s susceptibility. Seek specific triggers such as medical illness or response to a drug before assuming an illness of unknown cause such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. Cognitive therapy targeting specific symptoms is useful; antipsychotics probably will be necessary.

Related Resources

• Women and psychosis: A guide for women and their families. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. University of Toronto. www.camh.net/About_Addiction_Mental_ Health/Mental_Health_Information/Women_Psychosis.

• Seeman MV. Women and psychosis. www.medscape.com/ viewarticle/408912.

• Chattopadhyay S. Estrogen and schizophrenia: Any link? The Internet Journal of Mental Health. 2004;2(1). www.ispub. com/journal/the_internet_journal_of_mental_health.html.

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa Prednisone • Deltasone,

Estradiol • Estrace, Orasone, others

Estrofem, others Raloxifene • Evista

Estradiol transdermal • Risperidone • Risperdal

Estraderm , Climara, others

Methylphenidate • Concerta,

Ritalin, others

Disclosure

Dr. Seeman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Post RM. Kindling and sensitization as models for affective episode recurrence, cyclicity, and tolerance phenomena. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2007;31:858-873.

2. Seeman MV. Gender differences in schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 1982;27:107-112.

3. Seeman MV. Interaction of sex, age, and neuroleptic dose. Comp Psychiatry. 1983;24:125-128.

4. Usall J, Suarez D, Haro JM, and the SOHO Study Group. Gender differences in response to antipsychotic treatment in outpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2007;153: 225-231.

5. Hare E, Glahn DC, Dassori A, et al. Heritability of age of onset of psychosis in schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009 Apr 6 [Epub ahead of print].

6. Seeman MV. Gender differences in the prescribing of antipsychotic drugs. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1324-1333.

7. Marin R, Guerra B, Alonso R, et al. Estrogen activates classical and alternative mechanisms to orchestrate neuroprotection. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2005;2:287-301.

8. Seeman MV, Lang M. The role of estrogens in schizophrenia gender differences. Schizophr Bull. 1990;16:185-194.

9. Castle DJ, Abel K, Takei N, et al. Gender differences in schizophrenia: hormonal effect or subtypes? Schizophr Bull. 1995;21:1-12.

10. Häfner H, an der Heiden W. Epidemiology of schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 1997;42:139-151.

11. Grossman LS, Harrow M, Rosen C, et al. Sex differences in schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders: a 20-year longitudinal study of psychosis and recovery. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49:523-529.

12. Kajantie E, Phillips DI. The effects of sex and hormonal status on the physiological response to acute psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:151-178.

13. Riecher-Rössler A, Löffler W, Munk-Jörgensen P. What do we really know about late-onset schizophrenia? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;247:195-208.

14. Lindamer LA, Lohr JB, Harris MJ, et al. Gender-related clinical differences in older patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:61-67.

15. Seeman MV. Does menopause intensify symptoms in schizophrenia? In: Lewis-Hall F, Williams TS, Panetta JA, et al, eds. Psychiatric illness in women: emerging treatments and research. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2002:239-248.

16. Convert H, Védie C, Paulin P. [Late-onset schizophrenia or chronic delusion]. Encephale. 2006;32:957-961.

17. Sato T, Bottlender R, Schröter A, et al. Psychopathology of early-onset versus late-onset schizophrenia revisited: an observation of 473 neuroleptic-naive patients before and after first-admission treatments. Schizophr Res. 2004;67:175-183.

18. Palmer BW, McClure FS, Jeste DV. Schizophrenia in late life: findings challenge traditional concepts. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2001;9:51-58.

19. Weiss DB, Dyrud J, House RM, et al. Psychiatric manifestations of autoimmune disorders. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2005;7:413-417.

20. Castagnini A, Bertelsen A, Munk-Jorgensen P, et al. The relationship of reactive psychosis and ICD-10 acute and transient psychotic disorders: evidence from a case register-based comparison. Psychopathology. 2007;40:47-53.

21. Huber TJ, Rollnik J, Wilhelms J, et al. Estradiol levels in psychotic disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2001;26: 27-35.

22. Heiss G, Wallace R, Anderson G, et al, for the WHI Investigators. Health risks and benefits 3 years after stopping randomized treatment with estrogen and progestin. JAMA. 2008;299(9):1036-1045.

23. Doncarlos LL, Azcoitia I, Garcia-Segura LM. Neuroprotective actions of selective estrogen receptor modulators. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009 May 15 [Epub ahead of print].

24. Wong J, Seeman MV, Shapiro H. Case report: raloxifene in postmenopausal women with psychosis: preliminary findings. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11(6):697-698.

25. Ye L, Chan MY, Leung LK. The soy isoflavone genistein induces estrogen synthesis in an extragonadal pathway. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;302:73-80.

26. Kulkarni J, Gurvich C, Gilbert H, et al. Hormone modulation: a novel therapeutic approach for women with severe mental illness. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2008;42:83-88.

1. Post RM. Kindling and sensitization as models for affective episode recurrence, cyclicity, and tolerance phenomena. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2007;31:858-873.

2. Seeman MV. Gender differences in schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 1982;27:107-112.

3. Seeman MV. Interaction of sex, age, and neuroleptic dose. Comp Psychiatry. 1983;24:125-128.

4. Usall J, Suarez D, Haro JM, and the SOHO Study Group. Gender differences in response to antipsychotic treatment in outpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2007;153: 225-231.

5. Hare E, Glahn DC, Dassori A, et al. Heritability of age of onset of psychosis in schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009 Apr 6 [Epub ahead of print].

6. Seeman MV. Gender differences in the prescribing of antipsychotic drugs. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1324-1333.

7. Marin R, Guerra B, Alonso R, et al. Estrogen activates classical and alternative mechanisms to orchestrate neuroprotection. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2005;2:287-301.

8. Seeman MV, Lang M. The role of estrogens in schizophrenia gender differences. Schizophr Bull. 1990;16:185-194.

9. Castle DJ, Abel K, Takei N, et al. Gender differences in schizophrenia: hormonal effect or subtypes? Schizophr Bull. 1995;21:1-12.

10. Häfner H, an der Heiden W. Epidemiology of schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 1997;42:139-151.

11. Grossman LS, Harrow M, Rosen C, et al. Sex differences in schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders: a 20-year longitudinal study of psychosis and recovery. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49:523-529.

12. Kajantie E, Phillips DI. The effects of sex and hormonal status on the physiological response to acute psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:151-178.

13. Riecher-Rössler A, Löffler W, Munk-Jörgensen P. What do we really know about late-onset schizophrenia? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;247:195-208.

14. Lindamer LA, Lohr JB, Harris MJ, et al. Gender-related clinical differences in older patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:61-67.

15. Seeman MV. Does menopause intensify symptoms in schizophrenia? In: Lewis-Hall F, Williams TS, Panetta JA, et al, eds. Psychiatric illness in women: emerging treatments and research. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2002:239-248.

16. Convert H, Védie C, Paulin P. [Late-onset schizophrenia or chronic delusion]. Encephale. 2006;32:957-961.

17. Sato T, Bottlender R, Schröter A, et al. Psychopathology of early-onset versus late-onset schizophrenia revisited: an observation of 473 neuroleptic-naive patients before and after first-admission treatments. Schizophr Res. 2004;67:175-183.

18. Palmer BW, McClure FS, Jeste DV. Schizophrenia in late life: findings challenge traditional concepts. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2001;9:51-58.

19. Weiss DB, Dyrud J, House RM, et al. Psychiatric manifestations of autoimmune disorders. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2005;7:413-417.

20. Castagnini A, Bertelsen A, Munk-Jorgensen P, et al. The relationship of reactive psychosis and ICD-10 acute and transient psychotic disorders: evidence from a case register-based comparison. Psychopathology. 2007;40:47-53.

21. Huber TJ, Rollnik J, Wilhelms J, et al. Estradiol levels in psychotic disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2001;26: 27-35.

22. Heiss G, Wallace R, Anderson G, et al, for the WHI Investigators. Health risks and benefits 3 years after stopping randomized treatment with estrogen and progestin. JAMA. 2008;299(9):1036-1045.

23. Doncarlos LL, Azcoitia I, Garcia-Segura LM. Neuroprotective actions of selective estrogen receptor modulators. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009 May 15 [Epub ahead of print].

24. Wong J, Seeman MV, Shapiro H. Case report: raloxifene in postmenopausal women with psychosis: preliminary findings. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11(6):697-698.

25. Ye L, Chan MY, Leung LK. The soy isoflavone genistein induces estrogen synthesis in an extragonadal pathway. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;302:73-80.

26. Kulkarni J, Gurvich C, Gilbert H, et al. Hormone modulation: a novel therapeutic approach for women with severe mental illness. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2008;42:83-88.

How to talk to older patients about medication and alcohol misuse

Serotonin syndrome or NMS? Clues to diagnosis

Symptoms of serotonin syndrome and neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) are similar—mental status changes, autonomic dysfunction, and neuromuscular abnormalities—making the syndromes difficult to differentiate. However, therapeutic interventions and the mortality rates associated with these syndromes are widely divergent.

Because many medication regimens for treatment-resistant mood disorders modulate both serotonin and dopamine systems, psychiatrists must be prepared at any time to recognize either syndrome and quickly initiate appropriate treatment. For this, we rely on disease course, lab findings and vital signs, and the physical exam.

Clinical course

Serotonin syndrome symptoms can develop within minutes to hours after the administration of an agent that increases central serotonergic tone, such as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. After rapid onset, serotonin syndrome symptoms may improve or even resolve within <24 hours. NMS, on the other hand, can develop days to weeks after the administration of a dopamine antagonist—such as an antipsychotic—and may take 3 to 14 days to resolve.

Labs and vital signs