User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Thick chart syndrome: Treatment resistance is our greatest challenge

We all have patients with thick charts, the mentally ill individuals who push our clinical skills to the limit. They respond poorly to the entire algorithm of approved medications for depression, anxiety, or psychosis. Their symptoms hardly budge despite multiple psychotherapeutic interventions. They lead lives of quiet desperation and suffer through many hospitalizations and outpatient visits. They are perennially at high risk for harm to self or others. They get many side effects yet meager benefits from pharmacotherapy. Their social and vocational functions often are minimal to nil. Their life has little meaning beyond doleful patienthood.

Too complicated to be managed by primary care providers and most mental health practitioners, treatment-resistant patients often have several psychiatric comorbidities—both axis I and II. They frequently suffer from axis III disorders as well. Their lack of tangible response (let alone remission) frustrates us. Their poor treatment course and outcomes eventually tempt us to resort to unapproved polypharmacy and other non evidence-based practices in a desperate effort to help them.

We worry about our persistently unimproved patients; they haunt our thoughts after work. They are a constant reminder of how critical it is for our field to conduct aggressive, relentless research to unravel the underlying biology of chronic nonresponsive, disabling psychiatric brain disorders that rob children, adults, and elderly persons of their potential or even the ability to pursue happiness. We long for treatment breakthroughs that may reverse the downward spiral of their tortured lives.

Treatment resistance in my long-suffering patients incites me to ask important questions that beg for answers, such as:

- Are treatment-resistant patients afflicted by a categorically different subtype of illness, or do they suffer from a more severe form of the illness (ie, a dimensional difference)?

- Are some treatment-resistant patients victims of misdiagnosis? Do they have a psychiatric illness secondary to an unrecognized general medical condition that fails to respond to standard psychiatric treatments (such as a lack of response to several antidepressants in a patient with hypothyroid-induced depression or lack of efficacy of neuroleptics in psychosis secondary to a porphyria or Niemann-Pick disease)?

- Why isn’t the pharmaceutical industry conducting trials that target treatment-resistant patients? Controlled research trials in all clinical drug development programs for psychotropic medications explicitly exclude patients with a history of nonresponse. Thus, if a drug proves to be superior to placebo in FDA trials, it is likely to have efficacy in responsive patients but not in patients who have a history of nonresponse to prior medications

- Why are there no FDA studies of combination therapy—using drugs with different mechanisms of action—jointly sponsored (where necessary) by 2 or more pharmaceutical companies? Evidence-based, FDA -approved combinations are common for severe hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease; why not for severe psychiatric disorders?

- Why are personality disorders and psychiatric comorbidities more likely in treatment-resistant patients, and is this a neurobiologic clue for our nosologic/diagnostic framework and an impetus for better and innovative drug development?

- Why isn’t more funding from the National Institute of Mental Health targeting treatment-resistant diagnostic groups? Effective solutions for treatment-resistant populations, whose care often is very expensive, can be extremely beneficial for the affected individuals as well as substantially cost-effective for society at large.

Until my questions can be answered—and better treatment options emerge for my treatment-resistant patients—I will continue to do my best to relieve their agony and anguish. I will then write more progress notes and add yet more sheets of paper to their already thick charts.

We all have patients with thick charts, the mentally ill individuals who push our clinical skills to the limit. They respond poorly to the entire algorithm of approved medications for depression, anxiety, or psychosis. Their symptoms hardly budge despite multiple psychotherapeutic interventions. They lead lives of quiet desperation and suffer through many hospitalizations and outpatient visits. They are perennially at high risk for harm to self or others. They get many side effects yet meager benefits from pharmacotherapy. Their social and vocational functions often are minimal to nil. Their life has little meaning beyond doleful patienthood.

Too complicated to be managed by primary care providers and most mental health practitioners, treatment-resistant patients often have several psychiatric comorbidities—both axis I and II. They frequently suffer from axis III disorders as well. Their lack of tangible response (let alone remission) frustrates us. Their poor treatment course and outcomes eventually tempt us to resort to unapproved polypharmacy and other non evidence-based practices in a desperate effort to help them.

We worry about our persistently unimproved patients; they haunt our thoughts after work. They are a constant reminder of how critical it is for our field to conduct aggressive, relentless research to unravel the underlying biology of chronic nonresponsive, disabling psychiatric brain disorders that rob children, adults, and elderly persons of their potential or even the ability to pursue happiness. We long for treatment breakthroughs that may reverse the downward spiral of their tortured lives.

Treatment resistance in my long-suffering patients incites me to ask important questions that beg for answers, such as:

- Are treatment-resistant patients afflicted by a categorically different subtype of illness, or do they suffer from a more severe form of the illness (ie, a dimensional difference)?

- Are some treatment-resistant patients victims of misdiagnosis? Do they have a psychiatric illness secondary to an unrecognized general medical condition that fails to respond to standard psychiatric treatments (such as a lack of response to several antidepressants in a patient with hypothyroid-induced depression or lack of efficacy of neuroleptics in psychosis secondary to a porphyria or Niemann-Pick disease)?

- Why isn’t the pharmaceutical industry conducting trials that target treatment-resistant patients? Controlled research trials in all clinical drug development programs for psychotropic medications explicitly exclude patients with a history of nonresponse. Thus, if a drug proves to be superior to placebo in FDA trials, it is likely to have efficacy in responsive patients but not in patients who have a history of nonresponse to prior medications

- Why are there no FDA studies of combination therapy—using drugs with different mechanisms of action—jointly sponsored (where necessary) by 2 or more pharmaceutical companies? Evidence-based, FDA -approved combinations are common for severe hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease; why not for severe psychiatric disorders?

- Why are personality disorders and psychiatric comorbidities more likely in treatment-resistant patients, and is this a neurobiologic clue for our nosologic/diagnostic framework and an impetus for better and innovative drug development?

- Why isn’t more funding from the National Institute of Mental Health targeting treatment-resistant diagnostic groups? Effective solutions for treatment-resistant populations, whose care often is very expensive, can be extremely beneficial for the affected individuals as well as substantially cost-effective for society at large.

Until my questions can be answered—and better treatment options emerge for my treatment-resistant patients—I will continue to do my best to relieve their agony and anguish. I will then write more progress notes and add yet more sheets of paper to their already thick charts.

We all have patients with thick charts, the mentally ill individuals who push our clinical skills to the limit. They respond poorly to the entire algorithm of approved medications for depression, anxiety, or psychosis. Their symptoms hardly budge despite multiple psychotherapeutic interventions. They lead lives of quiet desperation and suffer through many hospitalizations and outpatient visits. They are perennially at high risk for harm to self or others. They get many side effects yet meager benefits from pharmacotherapy. Their social and vocational functions often are minimal to nil. Their life has little meaning beyond doleful patienthood.

Too complicated to be managed by primary care providers and most mental health practitioners, treatment-resistant patients often have several psychiatric comorbidities—both axis I and II. They frequently suffer from axis III disorders as well. Their lack of tangible response (let alone remission) frustrates us. Their poor treatment course and outcomes eventually tempt us to resort to unapproved polypharmacy and other non evidence-based practices in a desperate effort to help them.

We worry about our persistently unimproved patients; they haunt our thoughts after work. They are a constant reminder of how critical it is for our field to conduct aggressive, relentless research to unravel the underlying biology of chronic nonresponsive, disabling psychiatric brain disorders that rob children, adults, and elderly persons of their potential or even the ability to pursue happiness. We long for treatment breakthroughs that may reverse the downward spiral of their tortured lives.

Treatment resistance in my long-suffering patients incites me to ask important questions that beg for answers, such as:

- Are treatment-resistant patients afflicted by a categorically different subtype of illness, or do they suffer from a more severe form of the illness (ie, a dimensional difference)?

- Are some treatment-resistant patients victims of misdiagnosis? Do they have a psychiatric illness secondary to an unrecognized general medical condition that fails to respond to standard psychiatric treatments (such as a lack of response to several antidepressants in a patient with hypothyroid-induced depression or lack of efficacy of neuroleptics in psychosis secondary to a porphyria or Niemann-Pick disease)?

- Why isn’t the pharmaceutical industry conducting trials that target treatment-resistant patients? Controlled research trials in all clinical drug development programs for psychotropic medications explicitly exclude patients with a history of nonresponse. Thus, if a drug proves to be superior to placebo in FDA trials, it is likely to have efficacy in responsive patients but not in patients who have a history of nonresponse to prior medications

- Why are there no FDA studies of combination therapy—using drugs with different mechanisms of action—jointly sponsored (where necessary) by 2 or more pharmaceutical companies? Evidence-based, FDA -approved combinations are common for severe hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease; why not for severe psychiatric disorders?

- Why are personality disorders and psychiatric comorbidities more likely in treatment-resistant patients, and is this a neurobiologic clue for our nosologic/diagnostic framework and an impetus for better and innovative drug development?

- Why isn’t more funding from the National Institute of Mental Health targeting treatment-resistant diagnostic groups? Effective solutions for treatment-resistant populations, whose care often is very expensive, can be extremely beneficial for the affected individuals as well as substantially cost-effective for society at large.

Until my questions can be answered—and better treatment options emerge for my treatment-resistant patients—I will continue to do my best to relieve their agony and anguish. I will then write more progress notes and add yet more sheets of paper to their already thick charts.

Borderline or bipolar? Don't skimp on the life story

Guanfacine extended release for ADHD

Guanfacine extended release (GXR)—a selective α-2 adrenergic agonist FDA-approved for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)—has demonstrated efficacy for inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptom domains in 2 large trials lasting 8 and 9 weeks.1,2 GXR’s once-daily formulation may increase adherence and deliver consistent control of symptoms across a full day ( Table 1 ).

Table 1

Guanfacine extended release: Fast facts

| Brand name: Intuniv |

| Indication: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder |

| Approval date: September 3, 2009 |

| Availability date: November 2009 |

| Manufacturer: Shire |

| Dosing forms: 1-mg, 2-mg, 3-mg, and 4-mg extended-release tablets |

| Recommended dosage: 0.05 to 0.12 mg/kg once daily |

Clinical implications

GXR exhibits enhancement of noradrenergic pathways through selective direct receptor action in the prefrontal cortex.3 This mechanism of action is different from that of other FDA-approved ADHD medications. GXR can be used alone or in combination with stimulants or atomoxetine for treating complex ADHD, such as cases accompanied by oppositional features and emotional dysregulation or characterized by partial stimulant response.

How it works

Guanfacine—originally developed as an immediate-release (IR) antihypertensive—reduces sympathetic tone, causing centrally mediated vasodilation and reduced heart rate. Although GXR’s mechanism of action in ADHD is not known, the drug is a selective α-2A receptor agonist thought to directly engage postsynaptic receptors in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), an area of the brain believed to play a major role in attentional and organizational functions that preclinical research has linked to ADHD.3

The postsynaptic α-2A receptor is thought to play a central role in the optimal functioning of the PFC as illustrated by the “inverted U hypothesis of PFC activation.”4 In this model, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels build within the prefrontal cortical neurons and cause specific ion channels—hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide gated (HCN) channels—to open on dendritic spines of these neurons.5 Activation of HCN channels effectively reduces membrane resistance, cutting off synaptic inputs and disconnecting PFC network connections. Because α-2A receptors are located in proximity to HCN channels, their stimulation by GXR closes HCN channels, inhibits further production of cAMP, and reestablishes synaptic function and the resulting network connectivity.5 Blockade of α-2A receptors by yohimbine reverses this process, eroding network connectivity, and in monkeys has been demonstrated to impair working memory,6 damage inhibition/impulse control, and produce locomotor hyperactivity.

Direct stimulation by GXR of the postsynaptic α-2A receptors is thought to:

- strengthen working memory

- reduce susceptibility to distraction

- improve attention regulation

- improve behavioral inhibition

- enhance impulse control.7

Pharmacokinetics

GXR offers enhanced pharmaceutics relative to IR guanfacine. IR guanfacine exhibits poor absorption characteristics—peak plasma concentration is achieved too rapidly and then declines precipitously, with considerable inter-individual variation.

GXR’s once-daily formulation is implemented by a proprietary enteric-coated sustained release mechanism8 that is meant to:

- control absorption

- provide a broad but flat plasma concentration profile

- reduce inter-individual variation of guanfacine exposure.

Compared with IR guanfacine, GXR exhibits delayed time of maximum concentration (Tmax) and reduced maximum concentration (Cmax). Therapeutic concentrations can be sustained over longer periods with reduced peak-to-trough fluctuation,8 which tends to improve tolerability and symptom control throughout the day. The convenience of once-daily dosing also may increase adherence.

GXR’s pharmacokinetic characteristics do not change with dose, but high-fat meals will increase absorption of the drug—Cmax increases by 75% and area under the plasma concentration time curve increases by 40%. Because GXR primarily is metabolized through cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4, CYP3A4 inhibitors such as ketoconazole will increase guanfacine plasma concentrations and elevate the risk of adverse events such as bradycardia, hypotension, and sedation. Conversely, CYP3A4 inducers such as rifampin will significantly reduce total guanfacine exposure. Coadministration of valproic acid with GXR can result in increased valproic acid levels, producing additive CNS side effects.

Efficacy

GXR reduced both inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms in 2 phase III, forced-dose, parallel-design, randomized, placebo-controlled trials ( Table 2 ). In the first trial,1 345 children age 6 to 17 received placebo or GXR, 2 mg, 3 mg, or 4 mg once daily for 8 weeks. In the second study,2 324 children age 6 to 17 received placebo or GXR, 1 mg, 2 mg, 3 mg, or 4 mg, once daily for 9 weeks; the 1-mg dose was given only to patients weighing <50 kg (<110 lbs).

In both trials, doses were increased in increments of 1 mg/week, and investigators evaluated participants’ ADHD signs and symptoms once a week using the clinician administered and scored ADHD Rating Scale-IV (ADHD-RS-IV). The primary outcome was change in total ADHD-RS-IV score from baseline to endpoint.

In both trials, patients taking GXR demonstrated statistically signifcant improvements in ADHD-RS-IV score starting 1 to 2 weeks after they began receiving once-daily GXR:

- In the first trial, the mean reduction in ADHD-RS-IV total score at endpoint was –16.7 for GXR compared with –8.9 for placebo (P < .0001).

- In the second, the reduction was –19.6 for GXR and –12.2 for placebo (P=.004).

Placebo-adjusted least squares mean changes from baseline were statistically significant for all GXR doses in the randomized treatment groups in both studies.

Secondary efficacy outcome measures included the Conners’ Parent Rating Scale-Revised: Short Form (CPRS-R) and the Conners’ Teacher Rating Scale-Revised: Short Form (CTRS-R).

Significant improvements were seen on both scales. On the CPRS-R, parents reported significant improvement across a full day (as measured at 6 PM, 8 PM, and 6 AM the next day). On the CTRS-R—which was used only in the first trial—teachers reported significant improvement throughout the school day (as measured at 10 AM and 2 PM).

Treating oppositional symptoms. In a collateral study,9 GXR was evaluated in complex ADHD patients age 6 to 12 who exhibited oppositional symptoms. The primary efficacy measure was change from baseline to endpoint in the oppositional subscale of the Conners’ Parent Rating Scale-Revised: Long Form (CPRS-R:L) score.

All subjects randomized to GXR started on a dose of 1 mg/d—which could be titrated by 1 mg/week during the 5-week, dose-optimization period to a maximum of 4 mg/d—and were maintained at their optimal doses for 3 additional weeks. Among the 217 subjects enrolled, 138 received GXR and 79, placebo.

Least-squares mean reductions from baseline to endpoint in CPRS-R:L oppositional subscale scores were –10.9 in the GXR group compared with –6.8 in the placebo group (P < .001; effect size 0.590). The GXR-treated group showed a significantly greater reduction in ADHD-RS-IV total score from baseline to endpoint compared with the placebo group (–23.8 vs –11.4, respectively, P < .001; effect size 0.916).

Table 2

Randomized, controlled trials supporting GXR’s effectiveness

for treating ADHD symptoms

| Study | Subjects | GXR dosages | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biederman et al, 20087 ; phase III, forced-dose parallel-design | 345 ADHD patients age 6 to 17 | 2, 3, or 4 mg given once daily for 8 weeks | GXR was associated with significantly lower ADHD-RS-IV score compared with placebo (-16.7 vs -8.9) |

| Sallee et al, 20098 ; phase III, forced-dose parallel-design | 324 ADHD patients age 6 to 17 | 1,* 2, 3, or 4 mg given once daily for 9 weeks | GXR was associated with significantly lower ADHD-RS-IV score compared with placebo (-19.6 vs -12.2) |

| Connor et al, 20099 ; collateral study | 217 complex ADHD patients age 6 to 12 with oppositional symptoms | Starting dose 1 mg/d, titrated to a maximum of 4 mg/d for a total of 8 weeks | GXR was associated with significantly lower scores on CPRS-R:L oppositional subscale (-10.9 vs -6.8) and ADHD-RS-IV (-23.8 vs -11.4) compared with placebo |

| *1-mg dose was given only to subjects weighing <50 kg (<110 lbs) | |||

| ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ADHD-RS-IV: Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Rating Scale-IV; CPRS-R:L: Conners’ Parent Rating Scale-Revised: Long Form; GXR: guanfacine extended release | |||

Tolerability

In the phase III trials, the most commonly reported drug-related adverse reactions (occurring in ≥2% of patients) were:

- somnolence (38%)

- headache (24%)

- fatigue (14%)

- upper abdominal pain (10%)

- nausea, lethargy, dizziness, hypotension/decreased blood pressure, irritability (6% for each)

- decreased appetite (5%)

- dry mouth (4%)

- constipation (3%).

Many of these adverse reactions appear to be dose-related, particularly somnolence, sedation, abdominal pain, dizziness, and hypotension/decreased blood pressure.

Overall, GXR was well tolerated; clinicians rated most events as mild to moderate. Twelve percent of GXR patients discontinued the clinical studies because of adverse events, compared with 4% in the placebo groups. The most common adverse reactions leading to discontinuation were somnolence/sedation (6%) and fatigue (2%). Less common adverse reactions leading to discontinuation (occurring in 1% of patients) included hypotension/decreased blood pressure, headache, and dizziness.

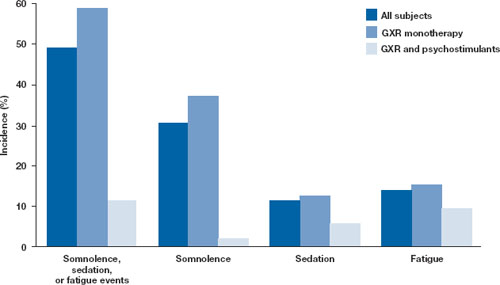

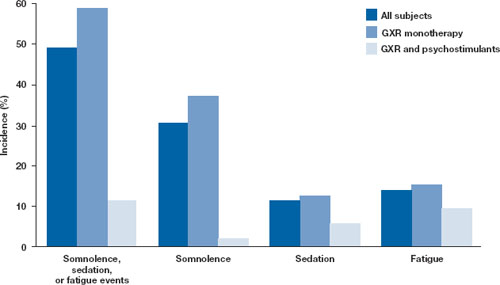

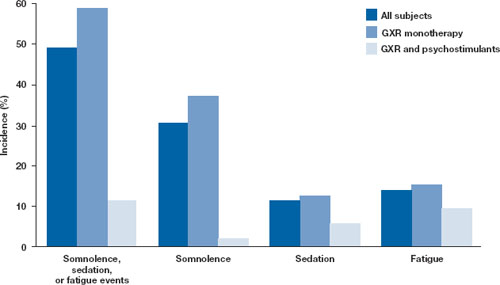

Open-label safety trial. Sallee et al10 conducted a longer-term, open-label, flexible-dose safety continuation study of 259 GXR-treated patients (mean exposure 10 months), some of whom also received a psychostimulant. Common adverse reactions (occurring in ≥5% of subjects) included somnolence (45%), headache (26%), fatigue (16%), upper abdominal pain (11%), hypotension/decreased blood pressure (10%), vomiting (9%), dizziness (7%), nausea (7%), weight gain (7%), and irritability (6%).10 In a subset of patients, the onset of sedative events typically occurred within the first 3 weeks of GXR treatment and then declined with maintenance to a frequency of approximately 16%. The rates of somnolence, sedation, or fatigue were lowest among patients who also received a psychostimulant ( Figure ).

Distribution of GXR doses before the end of this study was 37% of patients on 4 mg, 33% on 3 mg, 27% on 2 mg, and 3% on 1 mg, suggesting a preference for maintenance doses of 3 to 4 mg/d. The most frequent adverse reactions leading to discontinuation were somnolence (3%), syncopal events (2%), increased weight (2%), depression (2%), and fatigue (2%). Other adverse reactions leading to discontinuation (occurring in approximately 1% of patients) included hypotension/decreased blood pressure, sedation, headache, and lethargy. Serious adverse reactions in the longer-term study in >1 patient included syncope (2%) and convulsion (0.4%).

Figure: Incidence of somnolence, sedation, and fatigue in study patients receiving GXR

with or without psychostimulants

In an open-label continuation study of 259 patients treated with guanfacine extended release (GXR), somnolence, sedation, or fatigue was reported by 49% of subjects overall, 59% of those who received GXR monotherapy, and 11% of those given GXR with a psychostimulant.

GXR: guanfacine extended release

Source: Reprinted with permission from Sallee FR, Lyne A, Wigal T, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of guanfacine extended release in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(3):215-226 Safety warnings relating to the likelihood of hypotension, bradycardia, and possible syncope when prescribing GXR should be understood in the context of its pharmacologic action to lower heart rate and blood pressure. In the short-term (8 to 9 weeks) controlled trials, the maximum mean changes from baseline in systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and pulse were -5 mm Hg, -3 mm Hg, and -6 bpm, respectively, for all dose groups combined. These changes, which generally occurred 1 week after reaching target doses of 1 to 4 mg/d, were dose-dependent but usually modest and did not cause other symptoms; however, hypotension and bradycardia can occur.

In the longer-term, open-label safety study,10 maximum decreases in systolic and diastolic blood pressure occurred in the first month of treatment; decreases were less pronounced over time. Syncope occurred in 1% of pediatric subjects but was not dose-dependent. Guanfacine IR can increase QT interval but not in a dose-dependent fashion.

Dosing

The approved dose range for GXR is 1 to 4 mg once daily in the morning. Initiate treatment at 1 mg/d, and adjust the dose in increments of no more than 1 mg/week, evaluating the patient weekly. GXR maintenance therapy is frequently in the range of 2 to 4 mg/d.

Because adverse events such as hypotension, bradycardia, and sedation are dose-related, evaluate benefit and risk using mg/kg range approximation. GXR efficacy on a weight-adjusted (mg/kg) basis is consistent across a dosage range of 0.01 to 0.17 mg/kg/d. Clinically relevant improvements are usually observed beginning at doses of 0.05 to 0.08 mg/kg/d. In clinical trials, efficacy increased with increasing weight-adjusted dose (mg/kg), so if GXR is well-tolerated, doses up to 0.12 mg/kg once daily may provide additional benefit up to the maximum of 4 mg/d.

Instruct patients to swallow GXR whole because crushing, chewing, or otherwise breaking the tablet’s enteric coating will markedly enhance guanfacine release.

Abruptly discontinuing GXR is associated with infrequent, transient elevations in blood pressure above the patient’s baseline (ie, rebound). To minimize these effects, GXR should be gradually tapered in decrements of no more than 1 mg every 3 to 7 days. Isolated missed doses of GXR generally are not a problem, but ≥2 consecutive missed doses may warrant reinitiation of the titration schedule.

Related resource

- Guanfacine extended release (Intuniv) prescribing information. www.intuniv.com/documents/INTUNIV_Full_Prescribing_Information.pdf.

Drug brand names

- Atomoxetine • Strattera

- Guanfacine extended release • Intuniv

- Guanfacine immediate release • Tenex

- Ketoconazole • Nizoral

- Rifampin • Rifadin, Rimactane

- Valproic acid • Depakene, Depakote

Disclosure

Dr. Sallee receives grant/research support from the National Institutes of Health. He is a consultant to Otsuka, Nextwave, and Sepracor and a consultant to and speaker for Shire. Dr. Sallee is a consultant to, shareholder of, and member of the board of directors of P2D Inc. and a principal in Satiety Solutions.

1. Biederman J, Melmed RD, Patel A, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of guanfacine extended release in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e73-e84.

2. Sallee F, McGough J, Wigal T, et al. For the SPD503 Study Group Guanfacine extended release in children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(2):155-165.

3. Arnsten AF, Cai JX, Goldman-Rakic PS. The α-2 adrenergic agonist guanfacine improves memory in aged monkeys without sedative or hypotensive side effects: evidence for α-2 receptor subtypes. J Neurosci. 1988;8:4287-4298.

4. Vijayraghavan S, Wang M, Birnbaum SG, et al. Inverted-U dopamine D1 receptor actions on prefrontal neurons engaged in working memory. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:376-384.

5. Wang M, Ramos BP, Paspalas CD, et al. α 2-A adrenoceptors strengthen working memory networks by inhibiting cAMP-HCN channel signaling in prefrontal cortex. Cell. 2007;129:397-410.

6. Li BM, Mei ZT. Delayed-response deficit induced by local injection of the α 2-adrenergic antagonist yohimbine into the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in young adult monkeys. Behav Neural Biol. 1994;62:134-139.

7. Scahill L, Chappell PB, Kim YS, et al. A placebo-controlled study of guanfacine in the treatment of children with tic disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1067-1074.

8. Swearingen D, Pennick M, Shojaei A, et al. A phase I, randomized, open-label, crossover study of the single-dose pharmacokinetic properties of guanfacine extended-release 1-, 2-, and 4-mg tablets in healthy adults. Clin Ther. 2007;29:617-625.

9. Connor D, Spencer T, Kratochvil C, et al. Effects of guanfacine extended release on secondary measures in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and oppositional symptoms. Abstract presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; May 18, 2009; San Francisco, CA.

10. Sallee FR, Lyne A, Wigal T, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of guanfacine extended release in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(3):215-226.

Guanfacine extended release (GXR)—a selective α-2 adrenergic agonist FDA-approved for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)—has demonstrated efficacy for inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptom domains in 2 large trials lasting 8 and 9 weeks.1,2 GXR’s once-daily formulation may increase adherence and deliver consistent control of symptoms across a full day ( Table 1 ).

Table 1

Guanfacine extended release: Fast facts

| Brand name: Intuniv |

| Indication: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder |

| Approval date: September 3, 2009 |

| Availability date: November 2009 |

| Manufacturer: Shire |

| Dosing forms: 1-mg, 2-mg, 3-mg, and 4-mg extended-release tablets |

| Recommended dosage: 0.05 to 0.12 mg/kg once daily |

Clinical implications

GXR exhibits enhancement of noradrenergic pathways through selective direct receptor action in the prefrontal cortex.3 This mechanism of action is different from that of other FDA-approved ADHD medications. GXR can be used alone or in combination with stimulants or atomoxetine for treating complex ADHD, such as cases accompanied by oppositional features and emotional dysregulation or characterized by partial stimulant response.

How it works

Guanfacine—originally developed as an immediate-release (IR) antihypertensive—reduces sympathetic tone, causing centrally mediated vasodilation and reduced heart rate. Although GXR’s mechanism of action in ADHD is not known, the drug is a selective α-2A receptor agonist thought to directly engage postsynaptic receptors in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), an area of the brain believed to play a major role in attentional and organizational functions that preclinical research has linked to ADHD.3

The postsynaptic α-2A receptor is thought to play a central role in the optimal functioning of the PFC as illustrated by the “inverted U hypothesis of PFC activation.”4 In this model, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels build within the prefrontal cortical neurons and cause specific ion channels—hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide gated (HCN) channels—to open on dendritic spines of these neurons.5 Activation of HCN channels effectively reduces membrane resistance, cutting off synaptic inputs and disconnecting PFC network connections. Because α-2A receptors are located in proximity to HCN channels, their stimulation by GXR closes HCN channels, inhibits further production of cAMP, and reestablishes synaptic function and the resulting network connectivity.5 Blockade of α-2A receptors by yohimbine reverses this process, eroding network connectivity, and in monkeys has been demonstrated to impair working memory,6 damage inhibition/impulse control, and produce locomotor hyperactivity.

Direct stimulation by GXR of the postsynaptic α-2A receptors is thought to:

- strengthen working memory

- reduce susceptibility to distraction

- improve attention regulation

- improve behavioral inhibition

- enhance impulse control.7

Pharmacokinetics

GXR offers enhanced pharmaceutics relative to IR guanfacine. IR guanfacine exhibits poor absorption characteristics—peak plasma concentration is achieved too rapidly and then declines precipitously, with considerable inter-individual variation.

GXR’s once-daily formulation is implemented by a proprietary enteric-coated sustained release mechanism8 that is meant to:

- control absorption

- provide a broad but flat plasma concentration profile

- reduce inter-individual variation of guanfacine exposure.

Compared with IR guanfacine, GXR exhibits delayed time of maximum concentration (Tmax) and reduced maximum concentration (Cmax). Therapeutic concentrations can be sustained over longer periods with reduced peak-to-trough fluctuation,8 which tends to improve tolerability and symptom control throughout the day. The convenience of once-daily dosing also may increase adherence.

GXR’s pharmacokinetic characteristics do not change with dose, but high-fat meals will increase absorption of the drug—Cmax increases by 75% and area under the plasma concentration time curve increases by 40%. Because GXR primarily is metabolized through cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4, CYP3A4 inhibitors such as ketoconazole will increase guanfacine plasma concentrations and elevate the risk of adverse events such as bradycardia, hypotension, and sedation. Conversely, CYP3A4 inducers such as rifampin will significantly reduce total guanfacine exposure. Coadministration of valproic acid with GXR can result in increased valproic acid levels, producing additive CNS side effects.

Efficacy

GXR reduced both inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms in 2 phase III, forced-dose, parallel-design, randomized, placebo-controlled trials ( Table 2 ). In the first trial,1 345 children age 6 to 17 received placebo or GXR, 2 mg, 3 mg, or 4 mg once daily for 8 weeks. In the second study,2 324 children age 6 to 17 received placebo or GXR, 1 mg, 2 mg, 3 mg, or 4 mg, once daily for 9 weeks; the 1-mg dose was given only to patients weighing <50 kg (<110 lbs).

In both trials, doses were increased in increments of 1 mg/week, and investigators evaluated participants’ ADHD signs and symptoms once a week using the clinician administered and scored ADHD Rating Scale-IV (ADHD-RS-IV). The primary outcome was change in total ADHD-RS-IV score from baseline to endpoint.

In both trials, patients taking GXR demonstrated statistically signifcant improvements in ADHD-RS-IV score starting 1 to 2 weeks after they began receiving once-daily GXR:

- In the first trial, the mean reduction in ADHD-RS-IV total score at endpoint was –16.7 for GXR compared with –8.9 for placebo (P < .0001).

- In the second, the reduction was –19.6 for GXR and –12.2 for placebo (P=.004).

Placebo-adjusted least squares mean changes from baseline were statistically significant for all GXR doses in the randomized treatment groups in both studies.

Secondary efficacy outcome measures included the Conners’ Parent Rating Scale-Revised: Short Form (CPRS-R) and the Conners’ Teacher Rating Scale-Revised: Short Form (CTRS-R).

Significant improvements were seen on both scales. On the CPRS-R, parents reported significant improvement across a full day (as measured at 6 PM, 8 PM, and 6 AM the next day). On the CTRS-R—which was used only in the first trial—teachers reported significant improvement throughout the school day (as measured at 10 AM and 2 PM).

Treating oppositional symptoms. In a collateral study,9 GXR was evaluated in complex ADHD patients age 6 to 12 who exhibited oppositional symptoms. The primary efficacy measure was change from baseline to endpoint in the oppositional subscale of the Conners’ Parent Rating Scale-Revised: Long Form (CPRS-R:L) score.

All subjects randomized to GXR started on a dose of 1 mg/d—which could be titrated by 1 mg/week during the 5-week, dose-optimization period to a maximum of 4 mg/d—and were maintained at their optimal doses for 3 additional weeks. Among the 217 subjects enrolled, 138 received GXR and 79, placebo.

Least-squares mean reductions from baseline to endpoint in CPRS-R:L oppositional subscale scores were –10.9 in the GXR group compared with –6.8 in the placebo group (P < .001; effect size 0.590). The GXR-treated group showed a significantly greater reduction in ADHD-RS-IV total score from baseline to endpoint compared with the placebo group (–23.8 vs –11.4, respectively, P < .001; effect size 0.916).

Table 2

Randomized, controlled trials supporting GXR’s effectiveness

for treating ADHD symptoms

| Study | Subjects | GXR dosages | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biederman et al, 20087 ; phase III, forced-dose parallel-design | 345 ADHD patients age 6 to 17 | 2, 3, or 4 mg given once daily for 8 weeks | GXR was associated with significantly lower ADHD-RS-IV score compared with placebo (-16.7 vs -8.9) |

| Sallee et al, 20098 ; phase III, forced-dose parallel-design | 324 ADHD patients age 6 to 17 | 1,* 2, 3, or 4 mg given once daily for 9 weeks | GXR was associated with significantly lower ADHD-RS-IV score compared with placebo (-19.6 vs -12.2) |

| Connor et al, 20099 ; collateral study | 217 complex ADHD patients age 6 to 12 with oppositional symptoms | Starting dose 1 mg/d, titrated to a maximum of 4 mg/d for a total of 8 weeks | GXR was associated with significantly lower scores on CPRS-R:L oppositional subscale (-10.9 vs -6.8) and ADHD-RS-IV (-23.8 vs -11.4) compared with placebo |

| *1-mg dose was given only to subjects weighing <50 kg (<110 lbs) | |||

| ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ADHD-RS-IV: Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Rating Scale-IV; CPRS-R:L: Conners’ Parent Rating Scale-Revised: Long Form; GXR: guanfacine extended release | |||

Tolerability

In the phase III trials, the most commonly reported drug-related adverse reactions (occurring in ≥2% of patients) were:

- somnolence (38%)

- headache (24%)

- fatigue (14%)

- upper abdominal pain (10%)

- nausea, lethargy, dizziness, hypotension/decreased blood pressure, irritability (6% for each)

- decreased appetite (5%)

- dry mouth (4%)

- constipation (3%).

Many of these adverse reactions appear to be dose-related, particularly somnolence, sedation, abdominal pain, dizziness, and hypotension/decreased blood pressure.

Overall, GXR was well tolerated; clinicians rated most events as mild to moderate. Twelve percent of GXR patients discontinued the clinical studies because of adverse events, compared with 4% in the placebo groups. The most common adverse reactions leading to discontinuation were somnolence/sedation (6%) and fatigue (2%). Less common adverse reactions leading to discontinuation (occurring in 1% of patients) included hypotension/decreased blood pressure, headache, and dizziness.

Open-label safety trial. Sallee et al10 conducted a longer-term, open-label, flexible-dose safety continuation study of 259 GXR-treated patients (mean exposure 10 months), some of whom also received a psychostimulant. Common adverse reactions (occurring in ≥5% of subjects) included somnolence (45%), headache (26%), fatigue (16%), upper abdominal pain (11%), hypotension/decreased blood pressure (10%), vomiting (9%), dizziness (7%), nausea (7%), weight gain (7%), and irritability (6%).10 In a subset of patients, the onset of sedative events typically occurred within the first 3 weeks of GXR treatment and then declined with maintenance to a frequency of approximately 16%. The rates of somnolence, sedation, or fatigue were lowest among patients who also received a psychostimulant ( Figure ).

Distribution of GXR doses before the end of this study was 37% of patients on 4 mg, 33% on 3 mg, 27% on 2 mg, and 3% on 1 mg, suggesting a preference for maintenance doses of 3 to 4 mg/d. The most frequent adverse reactions leading to discontinuation were somnolence (3%), syncopal events (2%), increased weight (2%), depression (2%), and fatigue (2%). Other adverse reactions leading to discontinuation (occurring in approximately 1% of patients) included hypotension/decreased blood pressure, sedation, headache, and lethargy. Serious adverse reactions in the longer-term study in >1 patient included syncope (2%) and convulsion (0.4%).

Figure: Incidence of somnolence, sedation, and fatigue in study patients receiving GXR

with or without psychostimulants

In an open-label continuation study of 259 patients treated with guanfacine extended release (GXR), somnolence, sedation, or fatigue was reported by 49% of subjects overall, 59% of those who received GXR monotherapy, and 11% of those given GXR with a psychostimulant.

GXR: guanfacine extended release

Source: Reprinted with permission from Sallee FR, Lyne A, Wigal T, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of guanfacine extended release in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(3):215-226 Safety warnings relating to the likelihood of hypotension, bradycardia, and possible syncope when prescribing GXR should be understood in the context of its pharmacologic action to lower heart rate and blood pressure. In the short-term (8 to 9 weeks) controlled trials, the maximum mean changes from baseline in systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and pulse were -5 mm Hg, -3 mm Hg, and -6 bpm, respectively, for all dose groups combined. These changes, which generally occurred 1 week after reaching target doses of 1 to 4 mg/d, were dose-dependent but usually modest and did not cause other symptoms; however, hypotension and bradycardia can occur.

In the longer-term, open-label safety study,10 maximum decreases in systolic and diastolic blood pressure occurred in the first month of treatment; decreases were less pronounced over time. Syncope occurred in 1% of pediatric subjects but was not dose-dependent. Guanfacine IR can increase QT interval but not in a dose-dependent fashion.

Dosing

The approved dose range for GXR is 1 to 4 mg once daily in the morning. Initiate treatment at 1 mg/d, and adjust the dose in increments of no more than 1 mg/week, evaluating the patient weekly. GXR maintenance therapy is frequently in the range of 2 to 4 mg/d.

Because adverse events such as hypotension, bradycardia, and sedation are dose-related, evaluate benefit and risk using mg/kg range approximation. GXR efficacy on a weight-adjusted (mg/kg) basis is consistent across a dosage range of 0.01 to 0.17 mg/kg/d. Clinically relevant improvements are usually observed beginning at doses of 0.05 to 0.08 mg/kg/d. In clinical trials, efficacy increased with increasing weight-adjusted dose (mg/kg), so if GXR is well-tolerated, doses up to 0.12 mg/kg once daily may provide additional benefit up to the maximum of 4 mg/d.

Instruct patients to swallow GXR whole because crushing, chewing, or otherwise breaking the tablet’s enteric coating will markedly enhance guanfacine release.

Abruptly discontinuing GXR is associated with infrequent, transient elevations in blood pressure above the patient’s baseline (ie, rebound). To minimize these effects, GXR should be gradually tapered in decrements of no more than 1 mg every 3 to 7 days. Isolated missed doses of GXR generally are not a problem, but ≥2 consecutive missed doses may warrant reinitiation of the titration schedule.

Related resource

- Guanfacine extended release (Intuniv) prescribing information. www.intuniv.com/documents/INTUNIV_Full_Prescribing_Information.pdf.

Drug brand names

- Atomoxetine • Strattera

- Guanfacine extended release • Intuniv

- Guanfacine immediate release • Tenex

- Ketoconazole • Nizoral

- Rifampin • Rifadin, Rimactane

- Valproic acid • Depakene, Depakote

Disclosure

Dr. Sallee receives grant/research support from the National Institutes of Health. He is a consultant to Otsuka, Nextwave, and Sepracor and a consultant to and speaker for Shire. Dr. Sallee is a consultant to, shareholder of, and member of the board of directors of P2D Inc. and a principal in Satiety Solutions.

Guanfacine extended release (GXR)—a selective α-2 adrenergic agonist FDA-approved for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)—has demonstrated efficacy for inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptom domains in 2 large trials lasting 8 and 9 weeks.1,2 GXR’s once-daily formulation may increase adherence and deliver consistent control of symptoms across a full day ( Table 1 ).

Table 1

Guanfacine extended release: Fast facts

| Brand name: Intuniv |

| Indication: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder |

| Approval date: September 3, 2009 |

| Availability date: November 2009 |

| Manufacturer: Shire |

| Dosing forms: 1-mg, 2-mg, 3-mg, and 4-mg extended-release tablets |

| Recommended dosage: 0.05 to 0.12 mg/kg once daily |

Clinical implications

GXR exhibits enhancement of noradrenergic pathways through selective direct receptor action in the prefrontal cortex.3 This mechanism of action is different from that of other FDA-approved ADHD medications. GXR can be used alone or in combination with stimulants or atomoxetine for treating complex ADHD, such as cases accompanied by oppositional features and emotional dysregulation or characterized by partial stimulant response.

How it works

Guanfacine—originally developed as an immediate-release (IR) antihypertensive—reduces sympathetic tone, causing centrally mediated vasodilation and reduced heart rate. Although GXR’s mechanism of action in ADHD is not known, the drug is a selective α-2A receptor agonist thought to directly engage postsynaptic receptors in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), an area of the brain believed to play a major role in attentional and organizational functions that preclinical research has linked to ADHD.3

The postsynaptic α-2A receptor is thought to play a central role in the optimal functioning of the PFC as illustrated by the “inverted U hypothesis of PFC activation.”4 In this model, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels build within the prefrontal cortical neurons and cause specific ion channels—hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide gated (HCN) channels—to open on dendritic spines of these neurons.5 Activation of HCN channels effectively reduces membrane resistance, cutting off synaptic inputs and disconnecting PFC network connections. Because α-2A receptors are located in proximity to HCN channels, their stimulation by GXR closes HCN channels, inhibits further production of cAMP, and reestablishes synaptic function and the resulting network connectivity.5 Blockade of α-2A receptors by yohimbine reverses this process, eroding network connectivity, and in monkeys has been demonstrated to impair working memory,6 damage inhibition/impulse control, and produce locomotor hyperactivity.

Direct stimulation by GXR of the postsynaptic α-2A receptors is thought to:

- strengthen working memory

- reduce susceptibility to distraction

- improve attention regulation

- improve behavioral inhibition

- enhance impulse control.7

Pharmacokinetics

GXR offers enhanced pharmaceutics relative to IR guanfacine. IR guanfacine exhibits poor absorption characteristics—peak plasma concentration is achieved too rapidly and then declines precipitously, with considerable inter-individual variation.

GXR’s once-daily formulation is implemented by a proprietary enteric-coated sustained release mechanism8 that is meant to:

- control absorption

- provide a broad but flat plasma concentration profile

- reduce inter-individual variation of guanfacine exposure.

Compared with IR guanfacine, GXR exhibits delayed time of maximum concentration (Tmax) and reduced maximum concentration (Cmax). Therapeutic concentrations can be sustained over longer periods with reduced peak-to-trough fluctuation,8 which tends to improve tolerability and symptom control throughout the day. The convenience of once-daily dosing also may increase adherence.

GXR’s pharmacokinetic characteristics do not change with dose, but high-fat meals will increase absorption of the drug—Cmax increases by 75% and area under the plasma concentration time curve increases by 40%. Because GXR primarily is metabolized through cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4, CYP3A4 inhibitors such as ketoconazole will increase guanfacine plasma concentrations and elevate the risk of adverse events such as bradycardia, hypotension, and sedation. Conversely, CYP3A4 inducers such as rifampin will significantly reduce total guanfacine exposure. Coadministration of valproic acid with GXR can result in increased valproic acid levels, producing additive CNS side effects.

Efficacy

GXR reduced both inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms in 2 phase III, forced-dose, parallel-design, randomized, placebo-controlled trials ( Table 2 ). In the first trial,1 345 children age 6 to 17 received placebo or GXR, 2 mg, 3 mg, or 4 mg once daily for 8 weeks. In the second study,2 324 children age 6 to 17 received placebo or GXR, 1 mg, 2 mg, 3 mg, or 4 mg, once daily for 9 weeks; the 1-mg dose was given only to patients weighing <50 kg (<110 lbs).

In both trials, doses were increased in increments of 1 mg/week, and investigators evaluated participants’ ADHD signs and symptoms once a week using the clinician administered and scored ADHD Rating Scale-IV (ADHD-RS-IV). The primary outcome was change in total ADHD-RS-IV score from baseline to endpoint.

In both trials, patients taking GXR demonstrated statistically signifcant improvements in ADHD-RS-IV score starting 1 to 2 weeks after they began receiving once-daily GXR:

- In the first trial, the mean reduction in ADHD-RS-IV total score at endpoint was –16.7 for GXR compared with –8.9 for placebo (P < .0001).

- In the second, the reduction was –19.6 for GXR and –12.2 for placebo (P=.004).

Placebo-adjusted least squares mean changes from baseline were statistically significant for all GXR doses in the randomized treatment groups in both studies.

Secondary efficacy outcome measures included the Conners’ Parent Rating Scale-Revised: Short Form (CPRS-R) and the Conners’ Teacher Rating Scale-Revised: Short Form (CTRS-R).

Significant improvements were seen on both scales. On the CPRS-R, parents reported significant improvement across a full day (as measured at 6 PM, 8 PM, and 6 AM the next day). On the CTRS-R—which was used only in the first trial—teachers reported significant improvement throughout the school day (as measured at 10 AM and 2 PM).

Treating oppositional symptoms. In a collateral study,9 GXR was evaluated in complex ADHD patients age 6 to 12 who exhibited oppositional symptoms. The primary efficacy measure was change from baseline to endpoint in the oppositional subscale of the Conners’ Parent Rating Scale-Revised: Long Form (CPRS-R:L) score.

All subjects randomized to GXR started on a dose of 1 mg/d—which could be titrated by 1 mg/week during the 5-week, dose-optimization period to a maximum of 4 mg/d—and were maintained at their optimal doses for 3 additional weeks. Among the 217 subjects enrolled, 138 received GXR and 79, placebo.

Least-squares mean reductions from baseline to endpoint in CPRS-R:L oppositional subscale scores were –10.9 in the GXR group compared with –6.8 in the placebo group (P < .001; effect size 0.590). The GXR-treated group showed a significantly greater reduction in ADHD-RS-IV total score from baseline to endpoint compared with the placebo group (–23.8 vs –11.4, respectively, P < .001; effect size 0.916).

Table 2

Randomized, controlled trials supporting GXR’s effectiveness

for treating ADHD symptoms

| Study | Subjects | GXR dosages | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biederman et al, 20087 ; phase III, forced-dose parallel-design | 345 ADHD patients age 6 to 17 | 2, 3, or 4 mg given once daily for 8 weeks | GXR was associated with significantly lower ADHD-RS-IV score compared with placebo (-16.7 vs -8.9) |

| Sallee et al, 20098 ; phase III, forced-dose parallel-design | 324 ADHD patients age 6 to 17 | 1,* 2, 3, or 4 mg given once daily for 9 weeks | GXR was associated with significantly lower ADHD-RS-IV score compared with placebo (-19.6 vs -12.2) |

| Connor et al, 20099 ; collateral study | 217 complex ADHD patients age 6 to 12 with oppositional symptoms | Starting dose 1 mg/d, titrated to a maximum of 4 mg/d for a total of 8 weeks | GXR was associated with significantly lower scores on CPRS-R:L oppositional subscale (-10.9 vs -6.8) and ADHD-RS-IV (-23.8 vs -11.4) compared with placebo |

| *1-mg dose was given only to subjects weighing <50 kg (<110 lbs) | |||

| ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ADHD-RS-IV: Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Rating Scale-IV; CPRS-R:L: Conners’ Parent Rating Scale-Revised: Long Form; GXR: guanfacine extended release | |||

Tolerability

In the phase III trials, the most commonly reported drug-related adverse reactions (occurring in ≥2% of patients) were:

- somnolence (38%)

- headache (24%)

- fatigue (14%)

- upper abdominal pain (10%)

- nausea, lethargy, dizziness, hypotension/decreased blood pressure, irritability (6% for each)

- decreased appetite (5%)

- dry mouth (4%)

- constipation (3%).

Many of these adverse reactions appear to be dose-related, particularly somnolence, sedation, abdominal pain, dizziness, and hypotension/decreased blood pressure.

Overall, GXR was well tolerated; clinicians rated most events as mild to moderate. Twelve percent of GXR patients discontinued the clinical studies because of adverse events, compared with 4% in the placebo groups. The most common adverse reactions leading to discontinuation were somnolence/sedation (6%) and fatigue (2%). Less common adverse reactions leading to discontinuation (occurring in 1% of patients) included hypotension/decreased blood pressure, headache, and dizziness.

Open-label safety trial. Sallee et al10 conducted a longer-term, open-label, flexible-dose safety continuation study of 259 GXR-treated patients (mean exposure 10 months), some of whom also received a psychostimulant. Common adverse reactions (occurring in ≥5% of subjects) included somnolence (45%), headache (26%), fatigue (16%), upper abdominal pain (11%), hypotension/decreased blood pressure (10%), vomiting (9%), dizziness (7%), nausea (7%), weight gain (7%), and irritability (6%).10 In a subset of patients, the onset of sedative events typically occurred within the first 3 weeks of GXR treatment and then declined with maintenance to a frequency of approximately 16%. The rates of somnolence, sedation, or fatigue were lowest among patients who also received a psychostimulant ( Figure ).

Distribution of GXR doses before the end of this study was 37% of patients on 4 mg, 33% on 3 mg, 27% on 2 mg, and 3% on 1 mg, suggesting a preference for maintenance doses of 3 to 4 mg/d. The most frequent adverse reactions leading to discontinuation were somnolence (3%), syncopal events (2%), increased weight (2%), depression (2%), and fatigue (2%). Other adverse reactions leading to discontinuation (occurring in approximately 1% of patients) included hypotension/decreased blood pressure, sedation, headache, and lethargy. Serious adverse reactions in the longer-term study in >1 patient included syncope (2%) and convulsion (0.4%).

Figure: Incidence of somnolence, sedation, and fatigue in study patients receiving GXR

with or without psychostimulants

In an open-label continuation study of 259 patients treated with guanfacine extended release (GXR), somnolence, sedation, or fatigue was reported by 49% of subjects overall, 59% of those who received GXR monotherapy, and 11% of those given GXR with a psychostimulant.

GXR: guanfacine extended release

Source: Reprinted with permission from Sallee FR, Lyne A, Wigal T, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of guanfacine extended release in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(3):215-226 Safety warnings relating to the likelihood of hypotension, bradycardia, and possible syncope when prescribing GXR should be understood in the context of its pharmacologic action to lower heart rate and blood pressure. In the short-term (8 to 9 weeks) controlled trials, the maximum mean changes from baseline in systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and pulse were -5 mm Hg, -3 mm Hg, and -6 bpm, respectively, for all dose groups combined. These changes, which generally occurred 1 week after reaching target doses of 1 to 4 mg/d, were dose-dependent but usually modest and did not cause other symptoms; however, hypotension and bradycardia can occur.

In the longer-term, open-label safety study,10 maximum decreases in systolic and diastolic blood pressure occurred in the first month of treatment; decreases were less pronounced over time. Syncope occurred in 1% of pediatric subjects but was not dose-dependent. Guanfacine IR can increase QT interval but not in a dose-dependent fashion.

Dosing

The approved dose range for GXR is 1 to 4 mg once daily in the morning. Initiate treatment at 1 mg/d, and adjust the dose in increments of no more than 1 mg/week, evaluating the patient weekly. GXR maintenance therapy is frequently in the range of 2 to 4 mg/d.

Because adverse events such as hypotension, bradycardia, and sedation are dose-related, evaluate benefit and risk using mg/kg range approximation. GXR efficacy on a weight-adjusted (mg/kg) basis is consistent across a dosage range of 0.01 to 0.17 mg/kg/d. Clinically relevant improvements are usually observed beginning at doses of 0.05 to 0.08 mg/kg/d. In clinical trials, efficacy increased with increasing weight-adjusted dose (mg/kg), so if GXR is well-tolerated, doses up to 0.12 mg/kg once daily may provide additional benefit up to the maximum of 4 mg/d.

Instruct patients to swallow GXR whole because crushing, chewing, or otherwise breaking the tablet’s enteric coating will markedly enhance guanfacine release.

Abruptly discontinuing GXR is associated with infrequent, transient elevations in blood pressure above the patient’s baseline (ie, rebound). To minimize these effects, GXR should be gradually tapered in decrements of no more than 1 mg every 3 to 7 days. Isolated missed doses of GXR generally are not a problem, but ≥2 consecutive missed doses may warrant reinitiation of the titration schedule.

Related resource

- Guanfacine extended release (Intuniv) prescribing information. www.intuniv.com/documents/INTUNIV_Full_Prescribing_Information.pdf.

Drug brand names

- Atomoxetine • Strattera

- Guanfacine extended release • Intuniv

- Guanfacine immediate release • Tenex

- Ketoconazole • Nizoral

- Rifampin • Rifadin, Rimactane

- Valproic acid • Depakene, Depakote

Disclosure

Dr. Sallee receives grant/research support from the National Institutes of Health. He is a consultant to Otsuka, Nextwave, and Sepracor and a consultant to and speaker for Shire. Dr. Sallee is a consultant to, shareholder of, and member of the board of directors of P2D Inc. and a principal in Satiety Solutions.

1. Biederman J, Melmed RD, Patel A, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of guanfacine extended release in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e73-e84.

2. Sallee F, McGough J, Wigal T, et al. For the SPD503 Study Group Guanfacine extended release in children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(2):155-165.

3. Arnsten AF, Cai JX, Goldman-Rakic PS. The α-2 adrenergic agonist guanfacine improves memory in aged monkeys without sedative or hypotensive side effects: evidence for α-2 receptor subtypes. J Neurosci. 1988;8:4287-4298.

4. Vijayraghavan S, Wang M, Birnbaum SG, et al. Inverted-U dopamine D1 receptor actions on prefrontal neurons engaged in working memory. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:376-384.

5. Wang M, Ramos BP, Paspalas CD, et al. α 2-A adrenoceptors strengthen working memory networks by inhibiting cAMP-HCN channel signaling in prefrontal cortex. Cell. 2007;129:397-410.

6. Li BM, Mei ZT. Delayed-response deficit induced by local injection of the α 2-adrenergic antagonist yohimbine into the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in young adult monkeys. Behav Neural Biol. 1994;62:134-139.

7. Scahill L, Chappell PB, Kim YS, et al. A placebo-controlled study of guanfacine in the treatment of children with tic disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1067-1074.

8. Swearingen D, Pennick M, Shojaei A, et al. A phase I, randomized, open-label, crossover study of the single-dose pharmacokinetic properties of guanfacine extended-release 1-, 2-, and 4-mg tablets in healthy adults. Clin Ther. 2007;29:617-625.

9. Connor D, Spencer T, Kratochvil C, et al. Effects of guanfacine extended release on secondary measures in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and oppositional symptoms. Abstract presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; May 18, 2009; San Francisco, CA.

10. Sallee FR, Lyne A, Wigal T, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of guanfacine extended release in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(3):215-226.

1. Biederman J, Melmed RD, Patel A, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of guanfacine extended release in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e73-e84.

2. Sallee F, McGough J, Wigal T, et al. For the SPD503 Study Group Guanfacine extended release in children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(2):155-165.

3. Arnsten AF, Cai JX, Goldman-Rakic PS. The α-2 adrenergic agonist guanfacine improves memory in aged monkeys without sedative or hypotensive side effects: evidence for α-2 receptor subtypes. J Neurosci. 1988;8:4287-4298.

4. Vijayraghavan S, Wang M, Birnbaum SG, et al. Inverted-U dopamine D1 receptor actions on prefrontal neurons engaged in working memory. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:376-384.

5. Wang M, Ramos BP, Paspalas CD, et al. α 2-A adrenoceptors strengthen working memory networks by inhibiting cAMP-HCN channel signaling in prefrontal cortex. Cell. 2007;129:397-410.

6. Li BM, Mei ZT. Delayed-response deficit induced by local injection of the α 2-adrenergic antagonist yohimbine into the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in young adult monkeys. Behav Neural Biol. 1994;62:134-139.

7. Scahill L, Chappell PB, Kim YS, et al. A placebo-controlled study of guanfacine in the treatment of children with tic disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1067-1074.

8. Swearingen D, Pennick M, Shojaei A, et al. A phase I, randomized, open-label, crossover study of the single-dose pharmacokinetic properties of guanfacine extended-release 1-, 2-, and 4-mg tablets in healthy adults. Clin Ther. 2007;29:617-625.

9. Connor D, Spencer T, Kratochvil C, et al. Effects of guanfacine extended release on secondary measures in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and oppositional symptoms. Abstract presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; May 18, 2009; San Francisco, CA.

10. Sallee FR, Lyne A, Wigal T, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of guanfacine extended release in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(3):215-226.

Sad Dad: Identify depression in new fathers

After the birth of a child, family changes can put fathers at risk for postpartum depression. Long recognized as a problem affecting some new mothers, postpartum depression also can grip men. Ten percent of new fathers and 14% of new mothers are affected by depression.1 Still, most men and their partners fail to recognize postpartum depression—characterized by mood changes after a baby is born—when it arises.

Different causes, similar symptoms

Symptoms of postpartum depression are similar in both sexes, but the causes may be different. Hormonal changes contribute to women’s suffering, whereas sudden and unexpected lifestyle changes are thought to trigger fathers’ depression.

After the birth of a child, a father might not get the same attention from his partner and sexual activity may be reduced. His sleep is affected, and he may feel pressure to work longer hours to provide for the family economically.2 Some fathers may believe the child is a binding force in an unsatisfactory marriage.3

Depressed new dads—like depressed men in general—are more likely than depressed women to engage in destructive behaviors, including alcohol or drug abuse, angry outbursts, or taking unnecessary risks such as reckless driving or extramarital sex. Other signs to look for include depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure, weight gain or loss, oversleeping or insomnia, restlessness, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, impaired concentration, and thoughts of suicide or death.

Treatment

Postpartum depression can began within days or weeks of a child’s delivery and can last one year or more. In both sexes, it can be successfully treated with psycho therapy, medication, or both. The family’s involvement is critical to identifying depression in a new father. Often, the woman will be the first to notice her partner’s depression. A history of depression or mental illness and having a spouse with postpartum depression increases a father’s risk of depression.

1. Paulson JF, Dauber S, Leiferman JA. Individual and combined effects of postpartum depression in mothers and fathers on parenting behavior. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):659-668.

2. Scarton D. Post-partum depression strikes new dads, too. US News and World Report. May 21, 2008. Available at: http://health.usnews.com/articles/health/sexual-reproductive/2008/05/21/postpartum-depression-strikes-new-fathers-too.html. Accessed October 23, 2009.

3. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:869.

After the birth of a child, family changes can put fathers at risk for postpartum depression. Long recognized as a problem affecting some new mothers, postpartum depression also can grip men. Ten percent of new fathers and 14% of new mothers are affected by depression.1 Still, most men and their partners fail to recognize postpartum depression—characterized by mood changes after a baby is born—when it arises.

Different causes, similar symptoms

Symptoms of postpartum depression are similar in both sexes, but the causes may be different. Hormonal changes contribute to women’s suffering, whereas sudden and unexpected lifestyle changes are thought to trigger fathers’ depression.

After the birth of a child, a father might not get the same attention from his partner and sexual activity may be reduced. His sleep is affected, and he may feel pressure to work longer hours to provide for the family economically.2 Some fathers may believe the child is a binding force in an unsatisfactory marriage.3

Depressed new dads—like depressed men in general—are more likely than depressed women to engage in destructive behaviors, including alcohol or drug abuse, angry outbursts, or taking unnecessary risks such as reckless driving or extramarital sex. Other signs to look for include depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure, weight gain or loss, oversleeping or insomnia, restlessness, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, impaired concentration, and thoughts of suicide or death.

Treatment

Postpartum depression can began within days or weeks of a child’s delivery and can last one year or more. In both sexes, it can be successfully treated with psycho therapy, medication, or both. The family’s involvement is critical to identifying depression in a new father. Often, the woman will be the first to notice her partner’s depression. A history of depression or mental illness and having a spouse with postpartum depression increases a father’s risk of depression.

After the birth of a child, family changes can put fathers at risk for postpartum depression. Long recognized as a problem affecting some new mothers, postpartum depression also can grip men. Ten percent of new fathers and 14% of new mothers are affected by depression.1 Still, most men and their partners fail to recognize postpartum depression—characterized by mood changes after a baby is born—when it arises.

Different causes, similar symptoms

Symptoms of postpartum depression are similar in both sexes, but the causes may be different. Hormonal changes contribute to women’s suffering, whereas sudden and unexpected lifestyle changes are thought to trigger fathers’ depression.

After the birth of a child, a father might not get the same attention from his partner and sexual activity may be reduced. His sleep is affected, and he may feel pressure to work longer hours to provide for the family economically.2 Some fathers may believe the child is a binding force in an unsatisfactory marriage.3

Depressed new dads—like depressed men in general—are more likely than depressed women to engage in destructive behaviors, including alcohol or drug abuse, angry outbursts, or taking unnecessary risks such as reckless driving or extramarital sex. Other signs to look for include depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure, weight gain or loss, oversleeping or insomnia, restlessness, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, impaired concentration, and thoughts of suicide or death.

Treatment

Postpartum depression can began within days or weeks of a child’s delivery and can last one year or more. In both sexes, it can be successfully treated with psycho therapy, medication, or both. The family’s involvement is critical to identifying depression in a new father. Often, the woman will be the first to notice her partner’s depression. A history of depression or mental illness and having a spouse with postpartum depression increases a father’s risk of depression.

1. Paulson JF, Dauber S, Leiferman JA. Individual and combined effects of postpartum depression in mothers and fathers on parenting behavior. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):659-668.

2. Scarton D. Post-partum depression strikes new dads, too. US News and World Report. May 21, 2008. Available at: http://health.usnews.com/articles/health/sexual-reproductive/2008/05/21/postpartum-depression-strikes-new-fathers-too.html. Accessed October 23, 2009.

3. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:869.

1. Paulson JF, Dauber S, Leiferman JA. Individual and combined effects of postpartum depression in mothers and fathers on parenting behavior. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):659-668.

2. Scarton D. Post-partum depression strikes new dads, too. US News and World Report. May 21, 2008. Available at: http://health.usnews.com/articles/health/sexual-reproductive/2008/05/21/postpartum-depression-strikes-new-fathers-too.html. Accessed October 23, 2009.

3. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:869.

Terrifying visions

CASE: Seeing things

Family members bring Mrs. L, age 82, to the emergency room (ER) because she is agitated, nervous, and carries a knife “for protection.” In the past few months, she has been seeing things her family could not, such as bugs in her food and people trying to break into her house. Mrs. L becomes increasingly frightened and angry because her family denies seeing these things. Her family is concerned she might hurt herself or others.

Despite some hearing loss, Mrs. L had been relatively healthy and independent until a few years ago, when her vision decreased secondary to age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy. In addition to sensory impairment and diabetes mellitus, her medical history includes mild hypothyroidism and intervertebral disc herniation. She has no history of liver disease or alcohol or substance abuse. A few weeks ago Mrs. L’s primary care physician began treating her with donepezil, 5 mg/d, because he suspected dementia was causing her hallucinations. Otherwise, she has no psychiatric history.

On exam, Mrs. L is easily directable and cooperative. She seems angry because no one believes her; she reports seeing a cat that nobody else could see in the ER immediately before being evaluated. She is frightened because she believes her hallucinations are real, although she is unable to explain them. Mrs. L reports feeling anxious most of the time and having difficulty sleeping because of her fears. She also feels sad and occasionally worthless because she cannot see or hear as well as when she was younger.

A mental status examination shows partial impairment of concentration and short-term memory, but Mrs. L is alert and oriented. No theme of delusions is detected. She has no physical complaints, and physical examination is unremarkable.

The authors’ observations

Mrs. L presented with new-onset agitation, visual hallucinations, and mildly decreased concentration and short-term memory. Our next step after history and examination was to perform laboratory testing to narrow the diagnosis ( Table 1 ).

A basic electrolyte panel including kidney function can point toward electrolyte imbalance or uremia as a cause of delirium. Mrs. L’s basic metabolic panel and liver function were normal. Urinalysis ruled out urinary tract infection.

Mrs. L’s thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level was mildly elevated at 5.6 mU/L (in our laboratory, the upper normal limit is 5.2 mU/L). Hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism are not associated with hallucinations, but hyperthyroidism is an important medical cause of anxiety and hypothyroidism can cause a dementia-like presentation. CT of the head to rule out a space-occupying lesion or acute process—such as cerebrovascular accident—shows only chronic vascular changes.

Based on Mrs. L’s history, physical examination, and lab results, we provisionally diagnose dementia, Alzheimer’s type with psychotic features, and prescribe quetiapine, 25 mg at bedtime. We offer to admit Mrs. L, but she and her family prefer close outpatient follow-up. After discussing safety concerns and pharmacotherapy with the patient and her family, we discharge Mrs. L home and advise her to follow up with the psychiatric clinic.

Table 1

Suggested workup for elderly patients with hallucinations

| History and physical exam |

| History of dementia, mood disorder, Parkinson’s disease, or drug abuse |

| Presence of delusions or mood/anxiety symptoms |

| Detailed medication history |

| Level of consciousness, alertness, and cognitive function assessment (eg, MMSE) |

| Vital signs (instability may reflect delirium, meningitis/encephalitis, or intoxication) |

| Physical exam (may confirm acute medical illness causing delirium) |

| Neurologic exam (may show focal neurologic signs reflecting space-occupying lesion, signs of Parkinson’s disease, vitamin B12 deficiency) |

| Ophthalmologic history/exam |

| Investigations |

| Electrolyte imbalance, especially calcium |

| Glucose level |

| Uremia, impaired liver function, and increased ammonia |

| CBC |

| Urine drug screen |

| Urinalysis, culture, and sensitivity |

| Additional tests |