User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Assessing perinatal anxiety: What to ask

Emerging data demonstrate that untreated perinatal anxiety is associated with negative outcomes, including an increased risk for suicide.1 A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis that included 102 studies with a total of 221,974 women from 34 countries found that the prevalence of self-reported anxiety symptoms and any anxiety disorder was 22.9% and 15.2%, respectively, across the 3 trimesters.1 During pregnancy, anxiety disorders (eg, generalized anxiety disorder) and anxiety-related disorders (eg, obsessive-compulsive disorder [OCD] and posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) can present as new illnesses or as a reoccurrence of an existing illness. Patients with pre-existing OCD may notice that the nature of their obsessions is changing. Women with pre-existing PTSD may have their symptoms triggered by pregnancy or delivery or may develop PTSD as a result of a traumatic delivery. Anxiety is frequently comorbid with depression, and high anxiety during pregnancy is one of the strongest risk factors for depression.1,2

In light of this data, awareness and recognition of perinatal anxiety is critical. In this article, we describe how to accurately assess perinatal anxiety by avoiding assumptions and asking key questions during the clinical interview.

Avoid these common assumptions

Assessment begins with avoiding assumptions typically associated with maternal mental health. One common assumption is that pregnancy is a joyous occasion for all women. Pregnancy can be a stressful time that has its own unique difficulties, including the potential to develop or have a relapse of a mental illness. Another assumption is that the only concern is “postpartum depression.” In actuality, a significant percentage of women will experience depression during their pregnancy (not just in the postpartum period), and many other psychiatric illnesses are common during the perinatal period, including anxiety disorders.

Conduct a focused interview

Risk factors associated with antenatal anxiety include2:

- previous history of mental illness (particularly a history of anxiety and depression and a history of psychiatric treatment)

- lack of partner or social support

- history of abuse or domestic violence

- unplanned or unwanted pregnancy

- adverse events in life and high perceived stress

- present/past pregnancy complications

- pregnancy loss.

Symptoms of anxiety. The presence of anxiety or worrying does not necessarily mean a mother has an anxiety disorder. Using the DSM-5 as a guide, we should use the questions outlined in the following sections to inquire about all of the symptoms related to a particular illness, the pervasiveness of these symptoms, and to what extent these symptoms impair a woman’s ability to function and carry out her usual activities.3

Past psychiatric history. Ask your patient the following: Have you previously experienced anxiety and/or depressive symptoms? Were those symptoms limited only to times when you were pregnant or postpartum? Were your symptoms severe enough to disrupt your life (job, school, relationships, ability to complete daily tasks)? What treatments were effective for your symptoms? What treatments were ineffective?3

Social factors. Learn more about your patient’s support systems by asking: Who do you consider to be part of your social support? How is your relationship with your social support? Are there challenges in your relationship with your friends, family, or partner? If yes, what are those challenges? Are there other children in the home, and do you have support for them? Is your home environment safe? Do you feel that you have what you need for the baby? What stressors are you currently experiencing? Do you attend support groups for expectant mothers? Are you engaged in perinatal care?3

Continue to: Given the high prevalence...

Given the high prevalence of interpersonal violence in women of reproductive age, all patients should be screened for this. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women recommends screening for interpersonal violence at the first visit during the perinatal period, during each trimester, and at the postpartum visit (at minimum).4 Potential screening questions include (but are not limited to): Have you and/or your children ever been threatened by or felt afraid of your partner? When you argue with your partner, do either of you get physical? Has your partner ever physically hurt you (eg, hit, choked)? Do you feel safe at home? Do you have a safe place to go with resources you and your children will need in case of an emergency?4-6

Feelings toward pregnancy, past/current pregnancy complications, and pregnancy loss. Ask your patient: Was this pregnancy planned? How do you feel about your pregnancy? How do you see yourself as a mother? Do you currently have pregnancy complications and/or have had them in the past, and, if so, what are/were they? Have you lost a pregnancy? If so, what was that like? Do you have fears related to childbirth, and, if so, what are they?3

Intrusive thoughts about harming the baby. Intrusive thoughts are common in postpartum women with anxiety disorders, including OCD.7 Merely asking patients if they’ve had thoughts of harming their baby is incomplete and insufficient to assess for intrusive thoughts. This question does not distinguish between intrusive thoughts and homicidal ideation; this distinction is absolutely necessary given the difference in potential risk to the infant.

Intrusive thoughts are generally associated with a low risk of mothers acting on their thoughts. These thoughts are typically ego dystonic and, in the most severe form, can be distressing to an extent that they cause behavioral changes, such as avoiding bathing the infant, avoiding diaper changes, avoiding knives, or separating themselves from the infant.7 On the contrary, having homicidal ideation carries a higher risk for harm to the infant. Homicidal ideation may be seen in patients with co-occurring psychosis, poor reality testing, and delusions.5,7

Questions such as “Do you worry about harm coming to your baby?” “Do you worry about you causing harm to your baby?” and “Have you had an upsetting thought about harming your baby?” are more likely to reveal intrusive thoughts and prompt further exploration. Statements such as “Some people tell me that they have distressing thoughts about harm coming to their baby” can gently open the door to a having a dialogue about such thoughts. This dialogue is significantly important in making informed assessments as we develop comprehensive treatment plans.

1. Dennis CL, Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. B J Psychiatry. 2017;210(5):315-323.

2. Biaggi A, Conroy S, Pawlby S, et al. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;191:62-77.

3. Kirby N, Kilsby A, Walker R. Assessing low mood during pregnancy. BMJ. 2019;366:I4584. doi: 10.1136/bmj.I4584

4. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Committee opinion: Intimate partner violence. Number 518. February 2012. Accessed March 23, 2020. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2012/02/intimate-partner-violence

5. Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program for Moms Provider Toolkit. Accessed March 18, 2020. https://www.mcpapformoms.org/Docs/AdultProviderToolkit12.09.2019.pdf

6. Ashur ML. Asking about domestic violence: SAFE questions. JAMA. 1993;269(18):2367.

7. Brandes M, Soares CN, Cohen LS. Postpartum onset obsessive-compulsive disorder: diagnosis and management. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2004;7(2):99-110.

Emerging data demonstrate that untreated perinatal anxiety is associated with negative outcomes, including an increased risk for suicide.1 A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis that included 102 studies with a total of 221,974 women from 34 countries found that the prevalence of self-reported anxiety symptoms and any anxiety disorder was 22.9% and 15.2%, respectively, across the 3 trimesters.1 During pregnancy, anxiety disorders (eg, generalized anxiety disorder) and anxiety-related disorders (eg, obsessive-compulsive disorder [OCD] and posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) can present as new illnesses or as a reoccurrence of an existing illness. Patients with pre-existing OCD may notice that the nature of their obsessions is changing. Women with pre-existing PTSD may have their symptoms triggered by pregnancy or delivery or may develop PTSD as a result of a traumatic delivery. Anxiety is frequently comorbid with depression, and high anxiety during pregnancy is one of the strongest risk factors for depression.1,2

In light of this data, awareness and recognition of perinatal anxiety is critical. In this article, we describe how to accurately assess perinatal anxiety by avoiding assumptions and asking key questions during the clinical interview.

Avoid these common assumptions

Assessment begins with avoiding assumptions typically associated with maternal mental health. One common assumption is that pregnancy is a joyous occasion for all women. Pregnancy can be a stressful time that has its own unique difficulties, including the potential to develop or have a relapse of a mental illness. Another assumption is that the only concern is “postpartum depression.” In actuality, a significant percentage of women will experience depression during their pregnancy (not just in the postpartum period), and many other psychiatric illnesses are common during the perinatal period, including anxiety disorders.

Conduct a focused interview

Risk factors associated with antenatal anxiety include2:

- previous history of mental illness (particularly a history of anxiety and depression and a history of psychiatric treatment)

- lack of partner or social support

- history of abuse or domestic violence

- unplanned or unwanted pregnancy

- adverse events in life and high perceived stress

- present/past pregnancy complications

- pregnancy loss.

Symptoms of anxiety. The presence of anxiety or worrying does not necessarily mean a mother has an anxiety disorder. Using the DSM-5 as a guide, we should use the questions outlined in the following sections to inquire about all of the symptoms related to a particular illness, the pervasiveness of these symptoms, and to what extent these symptoms impair a woman’s ability to function and carry out her usual activities.3

Past psychiatric history. Ask your patient the following: Have you previously experienced anxiety and/or depressive symptoms? Were those symptoms limited only to times when you were pregnant or postpartum? Were your symptoms severe enough to disrupt your life (job, school, relationships, ability to complete daily tasks)? What treatments were effective for your symptoms? What treatments were ineffective?3

Social factors. Learn more about your patient’s support systems by asking: Who do you consider to be part of your social support? How is your relationship with your social support? Are there challenges in your relationship with your friends, family, or partner? If yes, what are those challenges? Are there other children in the home, and do you have support for them? Is your home environment safe? Do you feel that you have what you need for the baby? What stressors are you currently experiencing? Do you attend support groups for expectant mothers? Are you engaged in perinatal care?3

Continue to: Given the high prevalence...

Given the high prevalence of interpersonal violence in women of reproductive age, all patients should be screened for this. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women recommends screening for interpersonal violence at the first visit during the perinatal period, during each trimester, and at the postpartum visit (at minimum).4 Potential screening questions include (but are not limited to): Have you and/or your children ever been threatened by or felt afraid of your partner? When you argue with your partner, do either of you get physical? Has your partner ever physically hurt you (eg, hit, choked)? Do you feel safe at home? Do you have a safe place to go with resources you and your children will need in case of an emergency?4-6

Feelings toward pregnancy, past/current pregnancy complications, and pregnancy loss. Ask your patient: Was this pregnancy planned? How do you feel about your pregnancy? How do you see yourself as a mother? Do you currently have pregnancy complications and/or have had them in the past, and, if so, what are/were they? Have you lost a pregnancy? If so, what was that like? Do you have fears related to childbirth, and, if so, what are they?3

Intrusive thoughts about harming the baby. Intrusive thoughts are common in postpartum women with anxiety disorders, including OCD.7 Merely asking patients if they’ve had thoughts of harming their baby is incomplete and insufficient to assess for intrusive thoughts. This question does not distinguish between intrusive thoughts and homicidal ideation; this distinction is absolutely necessary given the difference in potential risk to the infant.

Intrusive thoughts are generally associated with a low risk of mothers acting on their thoughts. These thoughts are typically ego dystonic and, in the most severe form, can be distressing to an extent that they cause behavioral changes, such as avoiding bathing the infant, avoiding diaper changes, avoiding knives, or separating themselves from the infant.7 On the contrary, having homicidal ideation carries a higher risk for harm to the infant. Homicidal ideation may be seen in patients with co-occurring psychosis, poor reality testing, and delusions.5,7

Questions such as “Do you worry about harm coming to your baby?” “Do you worry about you causing harm to your baby?” and “Have you had an upsetting thought about harming your baby?” are more likely to reveal intrusive thoughts and prompt further exploration. Statements such as “Some people tell me that they have distressing thoughts about harm coming to their baby” can gently open the door to a having a dialogue about such thoughts. This dialogue is significantly important in making informed assessments as we develop comprehensive treatment plans.

Emerging data demonstrate that untreated perinatal anxiety is associated with negative outcomes, including an increased risk for suicide.1 A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis that included 102 studies with a total of 221,974 women from 34 countries found that the prevalence of self-reported anxiety symptoms and any anxiety disorder was 22.9% and 15.2%, respectively, across the 3 trimesters.1 During pregnancy, anxiety disorders (eg, generalized anxiety disorder) and anxiety-related disorders (eg, obsessive-compulsive disorder [OCD] and posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) can present as new illnesses or as a reoccurrence of an existing illness. Patients with pre-existing OCD may notice that the nature of their obsessions is changing. Women with pre-existing PTSD may have their symptoms triggered by pregnancy or delivery or may develop PTSD as a result of a traumatic delivery. Anxiety is frequently comorbid with depression, and high anxiety during pregnancy is one of the strongest risk factors for depression.1,2

In light of this data, awareness and recognition of perinatal anxiety is critical. In this article, we describe how to accurately assess perinatal anxiety by avoiding assumptions and asking key questions during the clinical interview.

Avoid these common assumptions

Assessment begins with avoiding assumptions typically associated with maternal mental health. One common assumption is that pregnancy is a joyous occasion for all women. Pregnancy can be a stressful time that has its own unique difficulties, including the potential to develop or have a relapse of a mental illness. Another assumption is that the only concern is “postpartum depression.” In actuality, a significant percentage of women will experience depression during their pregnancy (not just in the postpartum period), and many other psychiatric illnesses are common during the perinatal period, including anxiety disorders.

Conduct a focused interview

Risk factors associated with antenatal anxiety include2:

- previous history of mental illness (particularly a history of anxiety and depression and a history of psychiatric treatment)

- lack of partner or social support

- history of abuse or domestic violence

- unplanned or unwanted pregnancy

- adverse events in life and high perceived stress

- present/past pregnancy complications

- pregnancy loss.

Symptoms of anxiety. The presence of anxiety or worrying does not necessarily mean a mother has an anxiety disorder. Using the DSM-5 as a guide, we should use the questions outlined in the following sections to inquire about all of the symptoms related to a particular illness, the pervasiveness of these symptoms, and to what extent these symptoms impair a woman’s ability to function and carry out her usual activities.3

Past psychiatric history. Ask your patient the following: Have you previously experienced anxiety and/or depressive symptoms? Were those symptoms limited only to times when you were pregnant or postpartum? Were your symptoms severe enough to disrupt your life (job, school, relationships, ability to complete daily tasks)? What treatments were effective for your symptoms? What treatments were ineffective?3

Social factors. Learn more about your patient’s support systems by asking: Who do you consider to be part of your social support? How is your relationship with your social support? Are there challenges in your relationship with your friends, family, or partner? If yes, what are those challenges? Are there other children in the home, and do you have support for them? Is your home environment safe? Do you feel that you have what you need for the baby? What stressors are you currently experiencing? Do you attend support groups for expectant mothers? Are you engaged in perinatal care?3

Continue to: Given the high prevalence...

Given the high prevalence of interpersonal violence in women of reproductive age, all patients should be screened for this. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women recommends screening for interpersonal violence at the first visit during the perinatal period, during each trimester, and at the postpartum visit (at minimum).4 Potential screening questions include (but are not limited to): Have you and/or your children ever been threatened by or felt afraid of your partner? When you argue with your partner, do either of you get physical? Has your partner ever physically hurt you (eg, hit, choked)? Do you feel safe at home? Do you have a safe place to go with resources you and your children will need in case of an emergency?4-6

Feelings toward pregnancy, past/current pregnancy complications, and pregnancy loss. Ask your patient: Was this pregnancy planned? How do you feel about your pregnancy? How do you see yourself as a mother? Do you currently have pregnancy complications and/or have had them in the past, and, if so, what are/were they? Have you lost a pregnancy? If so, what was that like? Do you have fears related to childbirth, and, if so, what are they?3

Intrusive thoughts about harming the baby. Intrusive thoughts are common in postpartum women with anxiety disorders, including OCD.7 Merely asking patients if they’ve had thoughts of harming their baby is incomplete and insufficient to assess for intrusive thoughts. This question does not distinguish between intrusive thoughts and homicidal ideation; this distinction is absolutely necessary given the difference in potential risk to the infant.

Intrusive thoughts are generally associated with a low risk of mothers acting on their thoughts. These thoughts are typically ego dystonic and, in the most severe form, can be distressing to an extent that they cause behavioral changes, such as avoiding bathing the infant, avoiding diaper changes, avoiding knives, or separating themselves from the infant.7 On the contrary, having homicidal ideation carries a higher risk for harm to the infant. Homicidal ideation may be seen in patients with co-occurring psychosis, poor reality testing, and delusions.5,7

Questions such as “Do you worry about harm coming to your baby?” “Do you worry about you causing harm to your baby?” and “Have you had an upsetting thought about harming your baby?” are more likely to reveal intrusive thoughts and prompt further exploration. Statements such as “Some people tell me that they have distressing thoughts about harm coming to their baby” can gently open the door to a having a dialogue about such thoughts. This dialogue is significantly important in making informed assessments as we develop comprehensive treatment plans.

1. Dennis CL, Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. B J Psychiatry. 2017;210(5):315-323.

2. Biaggi A, Conroy S, Pawlby S, et al. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;191:62-77.

3. Kirby N, Kilsby A, Walker R. Assessing low mood during pregnancy. BMJ. 2019;366:I4584. doi: 10.1136/bmj.I4584

4. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Committee opinion: Intimate partner violence. Number 518. February 2012. Accessed March 23, 2020. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2012/02/intimate-partner-violence

5. Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program for Moms Provider Toolkit. Accessed March 18, 2020. https://www.mcpapformoms.org/Docs/AdultProviderToolkit12.09.2019.pdf

6. Ashur ML. Asking about domestic violence: SAFE questions. JAMA. 1993;269(18):2367.

7. Brandes M, Soares CN, Cohen LS. Postpartum onset obsessive-compulsive disorder: diagnosis and management. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2004;7(2):99-110.

1. Dennis CL, Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. B J Psychiatry. 2017;210(5):315-323.

2. Biaggi A, Conroy S, Pawlby S, et al. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;191:62-77.

3. Kirby N, Kilsby A, Walker R. Assessing low mood during pregnancy. BMJ. 2019;366:I4584. doi: 10.1136/bmj.I4584

4. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Committee opinion: Intimate partner violence. Number 518. February 2012. Accessed March 23, 2020. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2012/02/intimate-partner-violence

5. Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program for Moms Provider Toolkit. Accessed March 18, 2020. https://www.mcpapformoms.org/Docs/AdultProviderToolkit12.09.2019.pdf

6. Ashur ML. Asking about domestic violence: SAFE questions. JAMA. 1993;269(18):2367.

7. Brandes M, Soares CN, Cohen LS. Postpartum onset obsessive-compulsive disorder: diagnosis and management. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2004;7(2):99-110.

Systemic trauma in the Black community: My perspective as an Asian American

Being a physician gives me great privilege. However, this privilege did not start the moment I donned the white coat, but when I was born Asian American, to parents who hold advanced education degrees. It grew when our family moved to a White neighborhood and I was accepted into an elite college. For medical school and residency, I chose an academic program embedded in an urban setting that serves underprivileged minority communities. I entered psychiatry to facilitate healing. Yet as I read the headlines about people of color who had died at the hands of law enforcement, I found myself feeling overwhelmingly hopeless and numb.

In these individuals, I saw people who looked and lived just like the patients I chose to serve. But during this time, I did not see myself as the healer, but part of the system that brought pain and distress. As an Asian American, I identified with Tou Thao—the Asian American police officer involved in George Floyd’s death. In the medical community with which I identified, I found that ever-rising cases of COVID-19 were disproportionately affecting lower-income minority communities. In a polarizing world, I felt my Asian American identity prevented me from experiencing the pain and suffering Black communities faced. This was not my fight, and if it was, I was more immersed in the side that brought trauma to my patients. From a purely rational perspective, I had no right to feel sad. Intellectually, I felt unqualified to share in their pain, yet here I was, crying in my room.

An evolving transformation

As much as I wanted to take a break, training did not stop. A transformation occurred from an emerging awareness of the unique environment within which I was training and the intersection of who I knew myself to be. Serving in an urban program, I was given the opportunity for candid conversations with health professionals of color. I was humbled when Black colleagues proactively reached out to educate me about the historical context of these events and help me process them. I asked hard questions of my fellow residents who were Black, and listened to their answers and personal stories, which was difficult.

With my patients, I began to listen more intently and think about the systemic issues I had previously written off. One patient missed their appointment because public transportation was closed due to COVID-19. Another patient who was homeless was helped immensely by assistance with housing when he could no longer sleep at his place of residence. Really listening to him revealed that his street had become a common route for protests. With my therapy patient who experienced panic attacks listening to the news, I simply sat and grieved with them. I chose these interactions not because I was uniquely qualified, intelligent, or had any ability to change the trajectory of our country, but because they grew from me simply working in the context I chose and seeking the relationships I naturally sought.

How I define myself

As doctors, we accept the burden of caring for society’s ailments with the ultimate hope of celebrating triumph over the adversity of psychiatric illness. However, superseding our profession is the social system in which we live. I am part of a system that has historically caused trauma to some while benefitting others. Thus, between the calling of my practice and the country I practice in, I found a divergence. Once I accepted the truth of this system and the very personal way it affects me, my colleagues, and patients I serve, I was able to internally reconcile and rediscover hope. While I cannot change my experiences, advantages, or privilege, these facts do not change the reality that I am a citizen of the globe and human first. This realization is the silver lining of these perilous times; training among people of color who graciously included me in their experiences, and my willingness to listen and self-reflect. I now choose to define myself by what makes me similar to my patients instead of what isolates me from them. The tangible results of this deliberate step toward authenticity are renewed inspiration and joy.

For those of you who may have found yourself with no “ethnic home team” (or a desire for a new one), I leave you with this simple charge: Let your emotional reactions guide you to truth, and challenge yourself to process them with someone who doesn’t look like you. Leave your title at the door and embrace humility. You might be pleasantly surprised at the human you find when you look in the mirror.

Being a physician gives me great privilege. However, this privilege did not start the moment I donned the white coat, but when I was born Asian American, to parents who hold advanced education degrees. It grew when our family moved to a White neighborhood and I was accepted into an elite college. For medical school and residency, I chose an academic program embedded in an urban setting that serves underprivileged minority communities. I entered psychiatry to facilitate healing. Yet as I read the headlines about people of color who had died at the hands of law enforcement, I found myself feeling overwhelmingly hopeless and numb.

In these individuals, I saw people who looked and lived just like the patients I chose to serve. But during this time, I did not see myself as the healer, but part of the system that brought pain and distress. As an Asian American, I identified with Tou Thao—the Asian American police officer involved in George Floyd’s death. In the medical community with which I identified, I found that ever-rising cases of COVID-19 were disproportionately affecting lower-income minority communities. In a polarizing world, I felt my Asian American identity prevented me from experiencing the pain and suffering Black communities faced. This was not my fight, and if it was, I was more immersed in the side that brought trauma to my patients. From a purely rational perspective, I had no right to feel sad. Intellectually, I felt unqualified to share in their pain, yet here I was, crying in my room.

An evolving transformation

As much as I wanted to take a break, training did not stop. A transformation occurred from an emerging awareness of the unique environment within which I was training and the intersection of who I knew myself to be. Serving in an urban program, I was given the opportunity for candid conversations with health professionals of color. I was humbled when Black colleagues proactively reached out to educate me about the historical context of these events and help me process them. I asked hard questions of my fellow residents who were Black, and listened to their answers and personal stories, which was difficult.

With my patients, I began to listen more intently and think about the systemic issues I had previously written off. One patient missed their appointment because public transportation was closed due to COVID-19. Another patient who was homeless was helped immensely by assistance with housing when he could no longer sleep at his place of residence. Really listening to him revealed that his street had become a common route for protests. With my therapy patient who experienced panic attacks listening to the news, I simply sat and grieved with them. I chose these interactions not because I was uniquely qualified, intelligent, or had any ability to change the trajectory of our country, but because they grew from me simply working in the context I chose and seeking the relationships I naturally sought.

How I define myself

As doctors, we accept the burden of caring for society’s ailments with the ultimate hope of celebrating triumph over the adversity of psychiatric illness. However, superseding our profession is the social system in which we live. I am part of a system that has historically caused trauma to some while benefitting others. Thus, between the calling of my practice and the country I practice in, I found a divergence. Once I accepted the truth of this system and the very personal way it affects me, my colleagues, and patients I serve, I was able to internally reconcile and rediscover hope. While I cannot change my experiences, advantages, or privilege, these facts do not change the reality that I am a citizen of the globe and human first. This realization is the silver lining of these perilous times; training among people of color who graciously included me in their experiences, and my willingness to listen and self-reflect. I now choose to define myself by what makes me similar to my patients instead of what isolates me from them. The tangible results of this deliberate step toward authenticity are renewed inspiration and joy.

For those of you who may have found yourself with no “ethnic home team” (or a desire for a new one), I leave you with this simple charge: Let your emotional reactions guide you to truth, and challenge yourself to process them with someone who doesn’t look like you. Leave your title at the door and embrace humility. You might be pleasantly surprised at the human you find when you look in the mirror.

Being a physician gives me great privilege. However, this privilege did not start the moment I donned the white coat, but when I was born Asian American, to parents who hold advanced education degrees. It grew when our family moved to a White neighborhood and I was accepted into an elite college. For medical school and residency, I chose an academic program embedded in an urban setting that serves underprivileged minority communities. I entered psychiatry to facilitate healing. Yet as I read the headlines about people of color who had died at the hands of law enforcement, I found myself feeling overwhelmingly hopeless and numb.

In these individuals, I saw people who looked and lived just like the patients I chose to serve. But during this time, I did not see myself as the healer, but part of the system that brought pain and distress. As an Asian American, I identified with Tou Thao—the Asian American police officer involved in George Floyd’s death. In the medical community with which I identified, I found that ever-rising cases of COVID-19 were disproportionately affecting lower-income minority communities. In a polarizing world, I felt my Asian American identity prevented me from experiencing the pain and suffering Black communities faced. This was not my fight, and if it was, I was more immersed in the side that brought trauma to my patients. From a purely rational perspective, I had no right to feel sad. Intellectually, I felt unqualified to share in their pain, yet here I was, crying in my room.

An evolving transformation

As much as I wanted to take a break, training did not stop. A transformation occurred from an emerging awareness of the unique environment within which I was training and the intersection of who I knew myself to be. Serving in an urban program, I was given the opportunity for candid conversations with health professionals of color. I was humbled when Black colleagues proactively reached out to educate me about the historical context of these events and help me process them. I asked hard questions of my fellow residents who were Black, and listened to their answers and personal stories, which was difficult.

With my patients, I began to listen more intently and think about the systemic issues I had previously written off. One patient missed their appointment because public transportation was closed due to COVID-19. Another patient who was homeless was helped immensely by assistance with housing when he could no longer sleep at his place of residence. Really listening to him revealed that his street had become a common route for protests. With my therapy patient who experienced panic attacks listening to the news, I simply sat and grieved with them. I chose these interactions not because I was uniquely qualified, intelligent, or had any ability to change the trajectory of our country, but because they grew from me simply working in the context I chose and seeking the relationships I naturally sought.

How I define myself

As doctors, we accept the burden of caring for society’s ailments with the ultimate hope of celebrating triumph over the adversity of psychiatric illness. However, superseding our profession is the social system in which we live. I am part of a system that has historically caused trauma to some while benefitting others. Thus, between the calling of my practice and the country I practice in, I found a divergence. Once I accepted the truth of this system and the very personal way it affects me, my colleagues, and patients I serve, I was able to internally reconcile and rediscover hope. While I cannot change my experiences, advantages, or privilege, these facts do not change the reality that I am a citizen of the globe and human first. This realization is the silver lining of these perilous times; training among people of color who graciously included me in their experiences, and my willingness to listen and self-reflect. I now choose to define myself by what makes me similar to my patients instead of what isolates me from them. The tangible results of this deliberate step toward authenticity are renewed inspiration and joy.

For those of you who may have found yourself with no “ethnic home team” (or a desire for a new one), I leave you with this simple charge: Let your emotional reactions guide you to truth, and challenge yourself to process them with someone who doesn’t look like you. Leave your title at the door and embrace humility. You might be pleasantly surprised at the human you find when you look in the mirror.

Evidence-based medicine: It’s not a cookbook!

The term evidence-based medicine (EBM) has been derided by some as “cookbook medicine.” To others, EBM conjures up the efforts of describing interventions in terms of comparative effectiveness, drowning us in a deluge of “evidence-based” publications. The moniker has also been hijacked by companies to name their Health Economics and Outcomes research divisions. The spirit behind EBM is getting lost. EBM is not just about the evidence; it is about how we use it.1

In this commentary, we describe the concept of EBM and discuss teaching EBM to medical students and residents, its role in continuing medical education, and how it may be applied to practice, using a case scenario as a guide.

What is evidence-based medicine?

Sackett et al2 summed it best in an editorial published in the BMJ in 1996, where he emphasized decision-making in the care of individual patients. When making clinical decisions, using the best evidence available makes sense, but so does integrating individual clinical expertise and considering the individual patient’s preferences. Sackett et al2 warns about practice becoming tyrannized by evidence: “even excellent external evidence may be inapplicable to or inappropriate for an individual patient.” Clearly, EBM is not cookbook medicine.

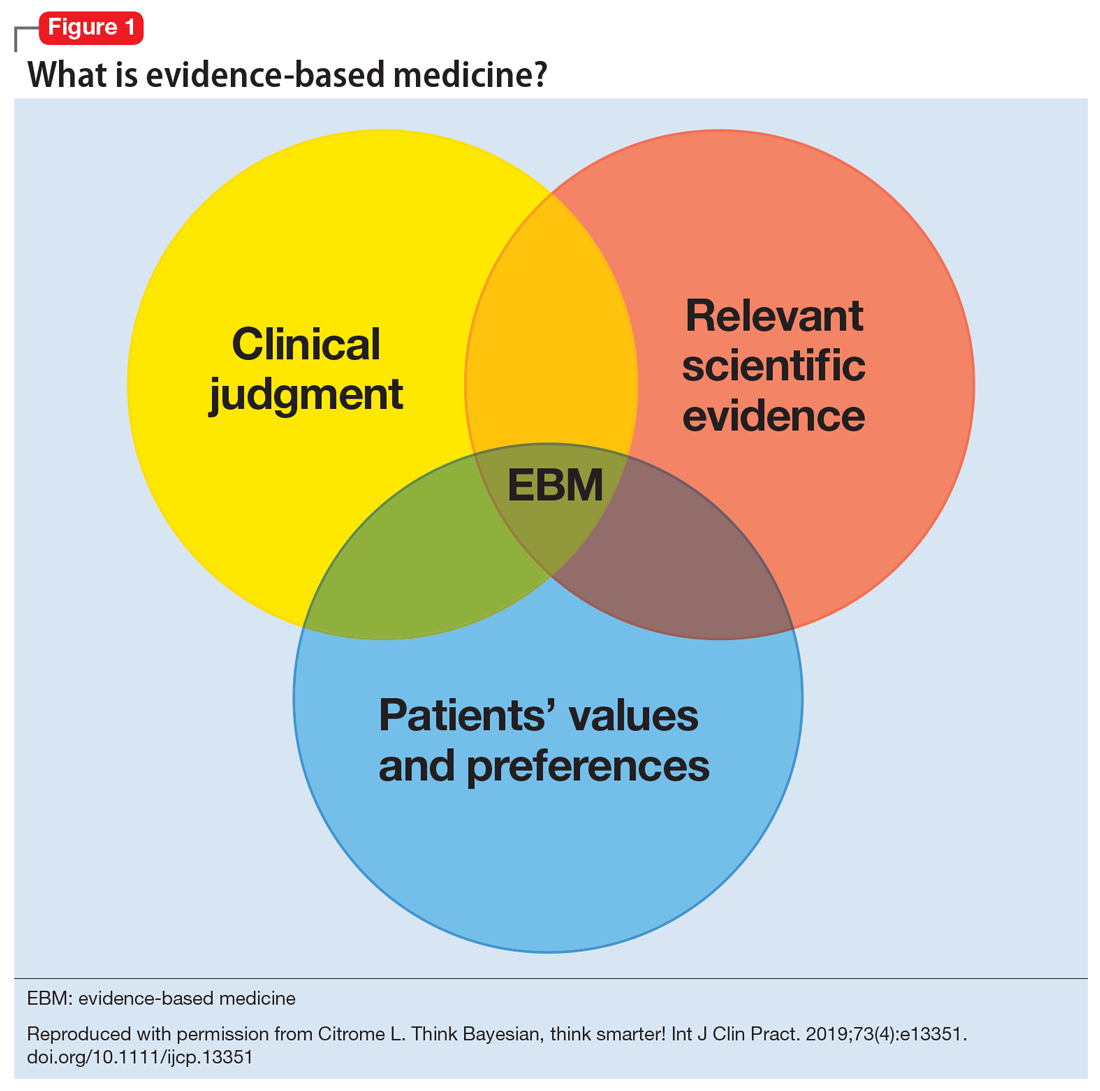

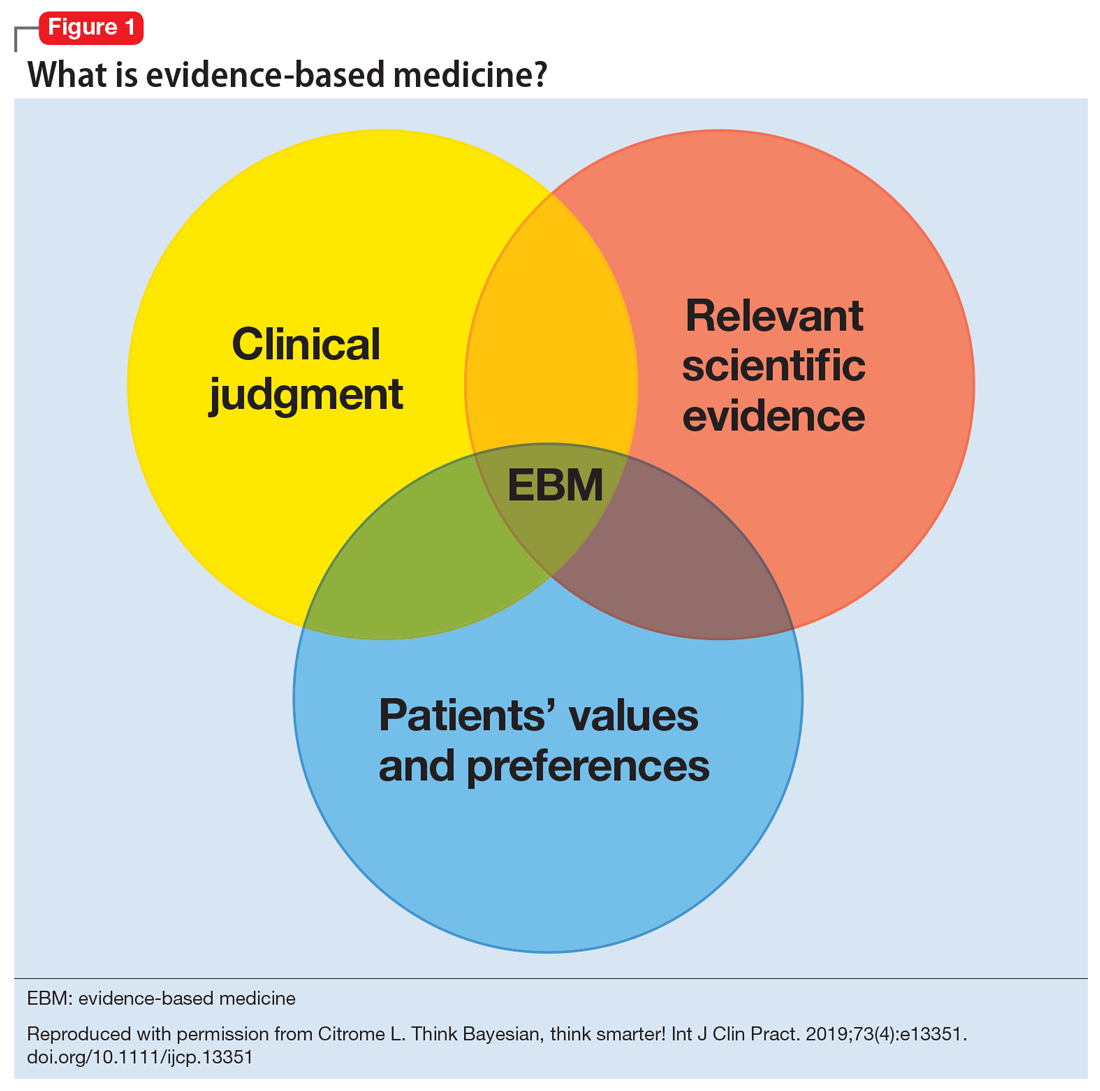

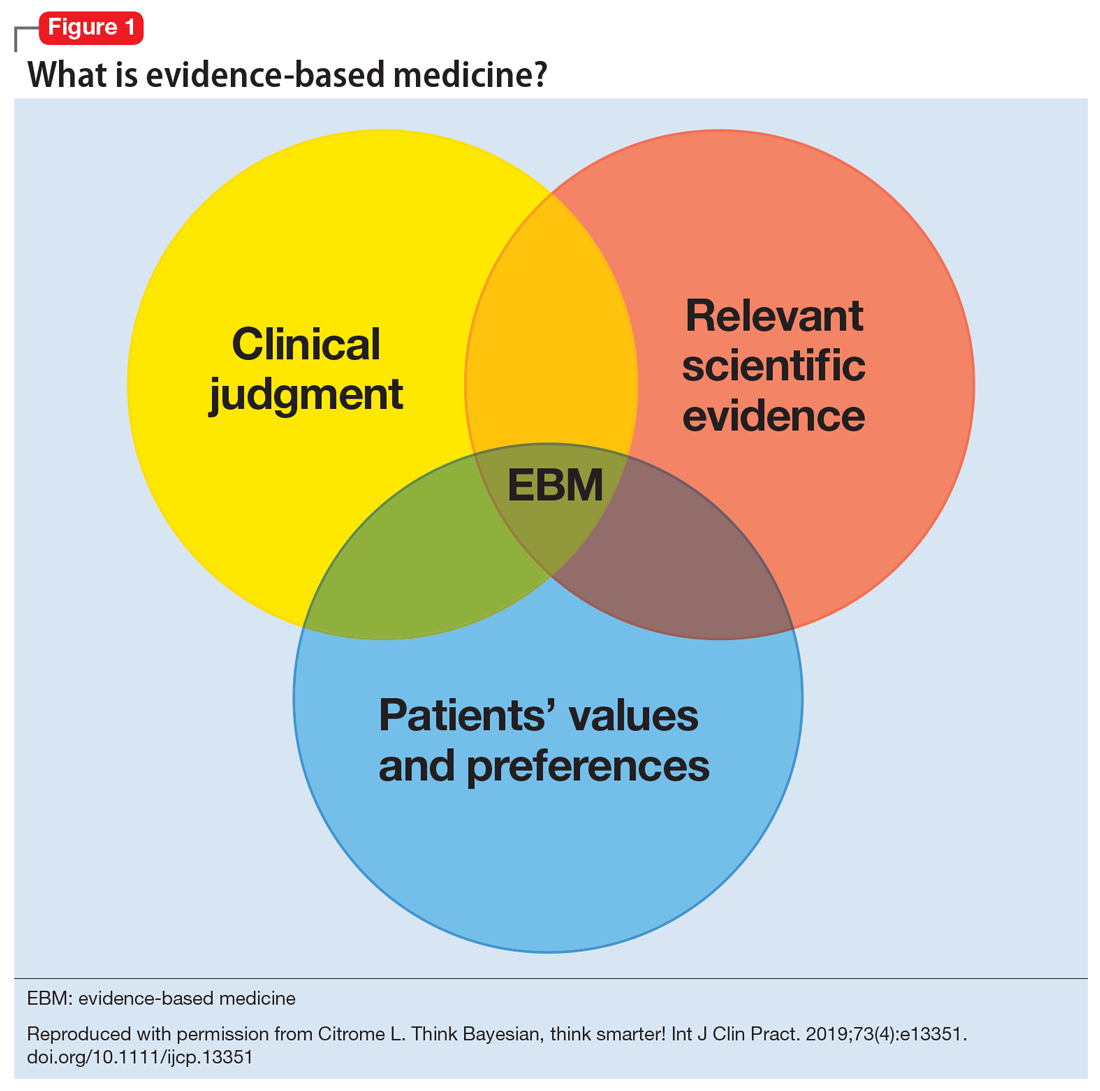

Figure 13 illustrates EBM as the confluence of clinical judgment, relevant scientific evidence, and patients’ values and preferences. The results from a clinical trial are only one part of the equation. As practitioners, we have the advantage of detailed knowledge about the patient, and our decisions are not “one size fits all.” Prior information about the patient dictates how we apply the evidence that supports potential interventions.

The concept of EBM was born out of necessity to bring scientific principles into the heart of medicine. As outlined by Sackett,4 the practice of EBM is a process of lifelong, self-directed learning in which caring for our own patients creates the need for clinically important information about diagnosis, prognosis, therapy, and other clinical and health care issues. Through EBM, we:

- convert these information needs into answerable questions

- track down, with maximum efficiency, the best evidence with which to answer questions (whether from clinical examination, diagnostic laboratory results, research evidence, or other sources)

- critically appraise that evidence for its validity (closeness to the truth) and usefulness (clinical applicability)

- integrate this appraisal with our clinical expertise and apply it in practice

- evaluate our performance.

Over the years, the original aim of EBM as a self-directed method for clinicians to practice high-quality medicine was morphed by some into a tool of enforced standardization and a boilerplate approach to managing costs across systems of care. As a result, the term EBM has been criticized because of:

- its reliance on empiricism

- a narrow definition of evidence

- a lack of evidence of efficacy

- its limited usefulness for individual patients

- threats to the autonomy of the doctor-patient relationship.

These 5 categories are associated with severe drawbacks when used for individual patient care.5 In addition to problems with applying standardized population research to a specific patient with a specific set of symptoms, medications, genetic variations, and unique environment, it can take years for clinicians to change their practices to incorporate new information.6

Continue to: Evidence that is too narrow...

Evidence that is too narrow in scope may not be useful. Single-molecule pharmaceutical clinical trials have erroneously become a synonym of EBM. Such studies do not reflect complex, real-life situations. Based on such studies, FDA product labeling can be inadequate in its guidance, particularly when faced with complex comorbidities. The standard comparison of active treatment to placebo is also seen as EBM, narrowing its scope and deflecting from clinical medicine when physicians measure one treatment’s success against another vs measuring real treatments against shams. Real-life treatment choice is frequently based on considering adverse effects as important to consider as therapeutic efficacy; however, this concept is outside of the common (mis)understanding of EBM.

Conflicting and ever-changing data and the push to replace clinical thinking with general dogmas trivializes medical practice and endangers treatment outcomes. This would not happen to the extent we see now if EBM was again seen as a guide and general direction rather than a blanket, distorted requirement to follow rigid recommendations for specific patients.

Insurance companies have driven a change in the understanding of EBM by using the FDA label as an excuse to deny, delay, and/or refuse to pay for treatments that are not explicitly and narrowly on-label. Dependence on on-label treatments is even more challenging in specialty medicine because primary care clinicians generally have tried the conventional approaches before referring patients to a specialist. However, insurance denials rarely differentiate between practice settings.

Medicolegal issues have cemented the present situation when clinically valid “off-label” treatments may be a reasonable consideration for patients but can place health care practitioners in jeopardy. The distorted EBM doctrine has become a justification for legal actions against clinicians who practice individualized medicine.

Concision bias (selectively focusing on information, losing nuance) and selection bias (patients in clinical trials who do not reflect real-life patients) have become an impediment to progress and EBM as originally intended.

Continue to: Training medical students and residents

Training medical students and residents

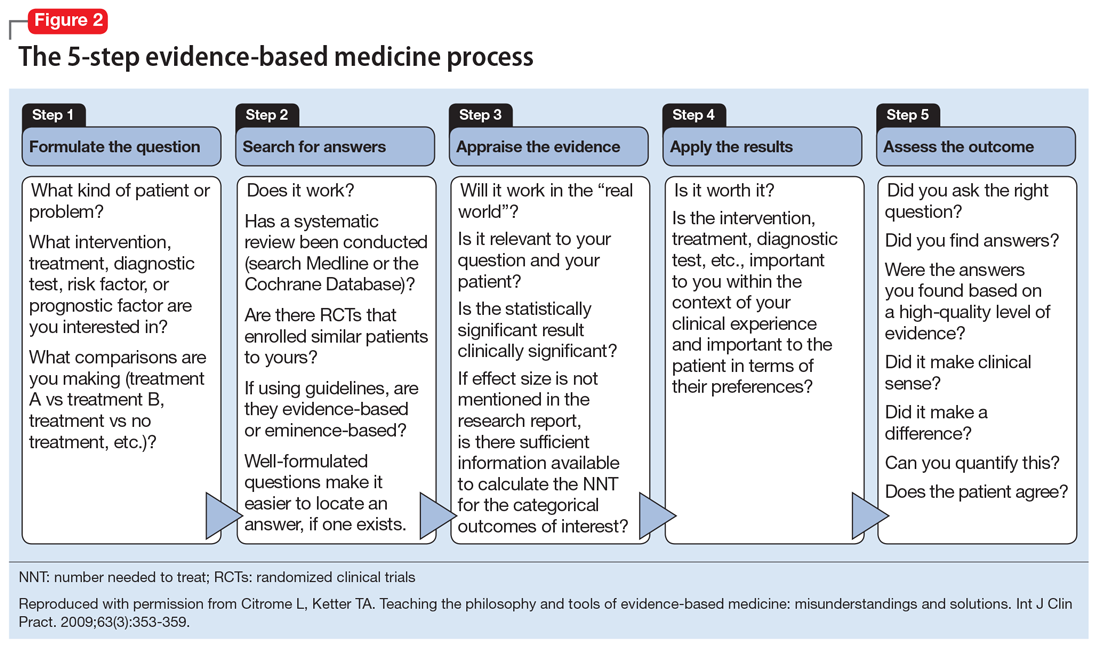

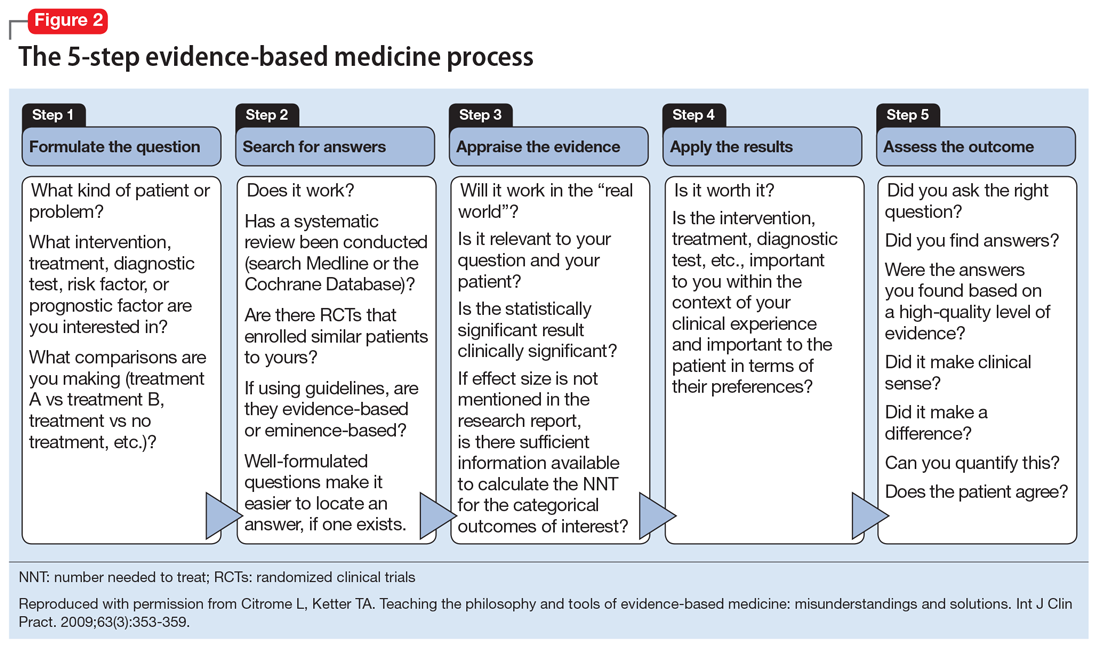

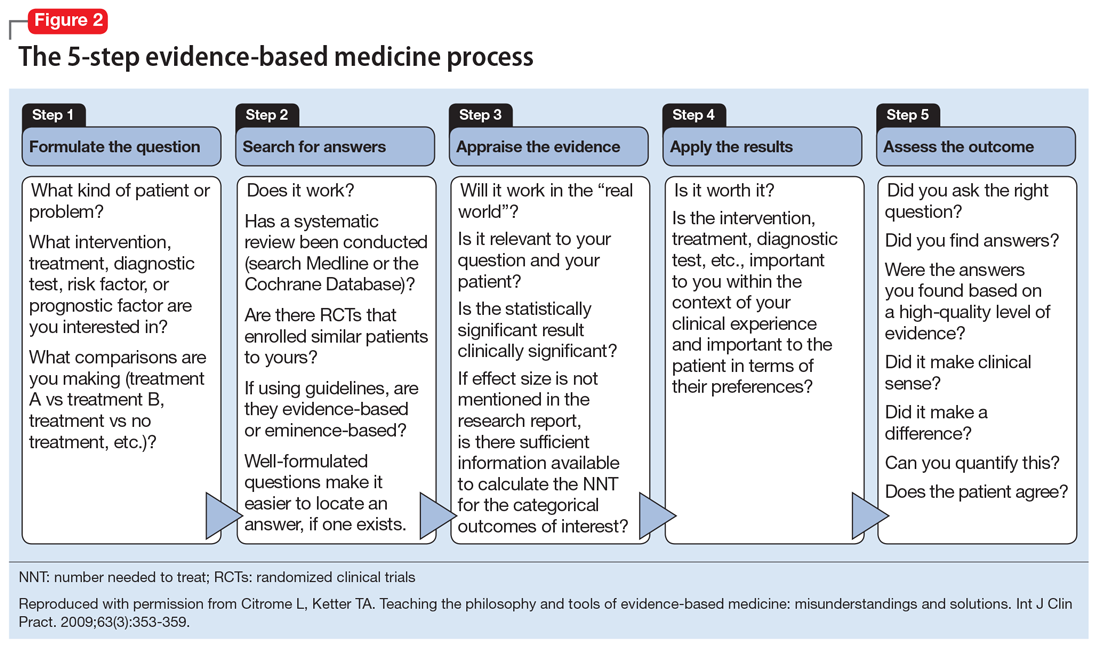

Although there is some variation in how EBM is taught to medical students and residents,7,8 the expectation is that such education occurs. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements for a residency program state that “the program must advance residents’ knowledge and practice of the scholarly approach to evidence-based patient care.”9 The topic has been part of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology Model Psychopharmacology Curriculum, but only in an optional lecture.10 The formal teaching of EBM includes how to find relevant biomedical publications for the clinical issues at hand, understand the different hierarchies of evidence, interpret results in terms of effect size, and apply this knowledge in the care of patients. This 5-step process is illustrated in Figure 28. See Related Resources for 3 books that provide a scholarly yet clinically relevant approach to EBM.

Continuing medical education

Most

Practical applications

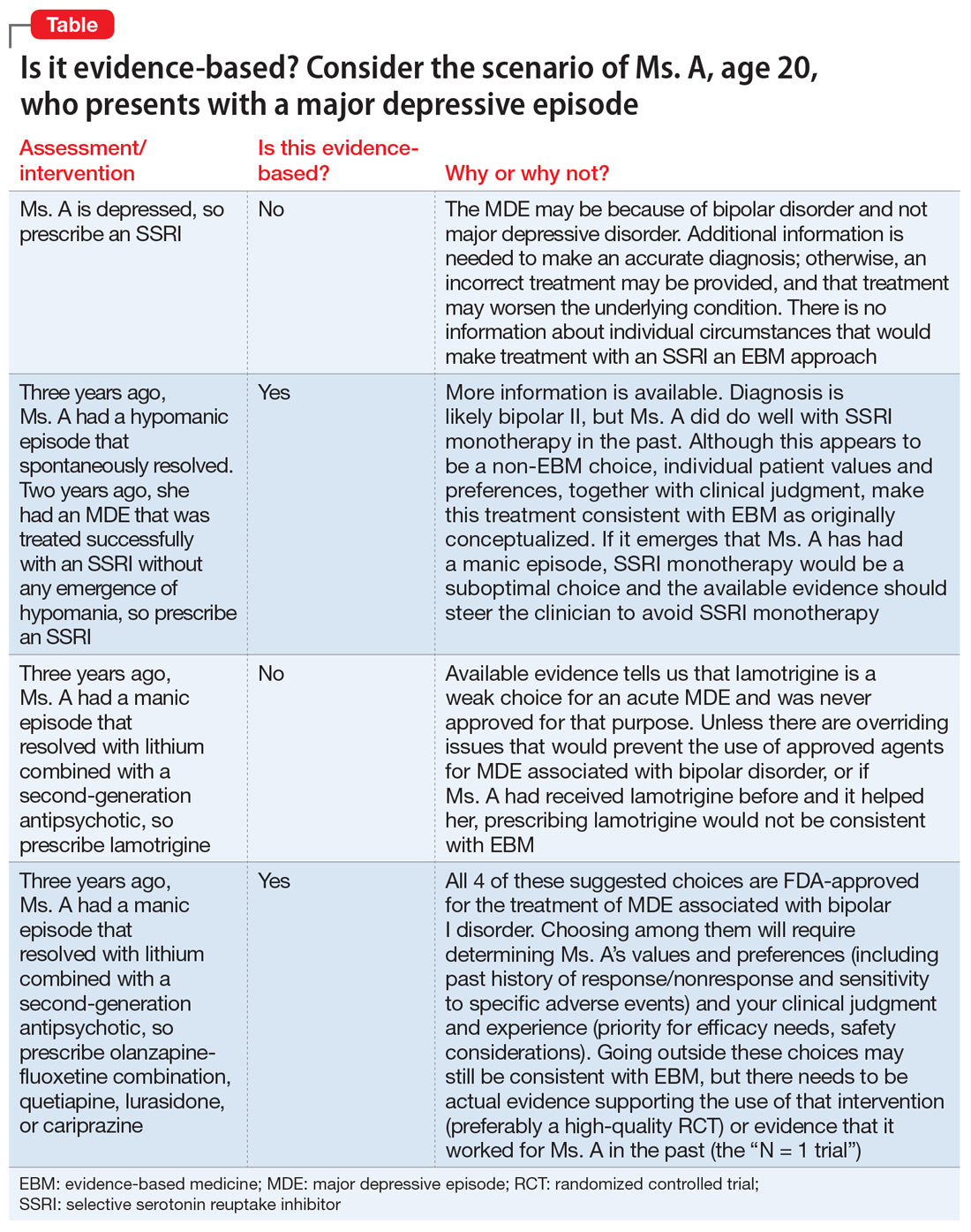

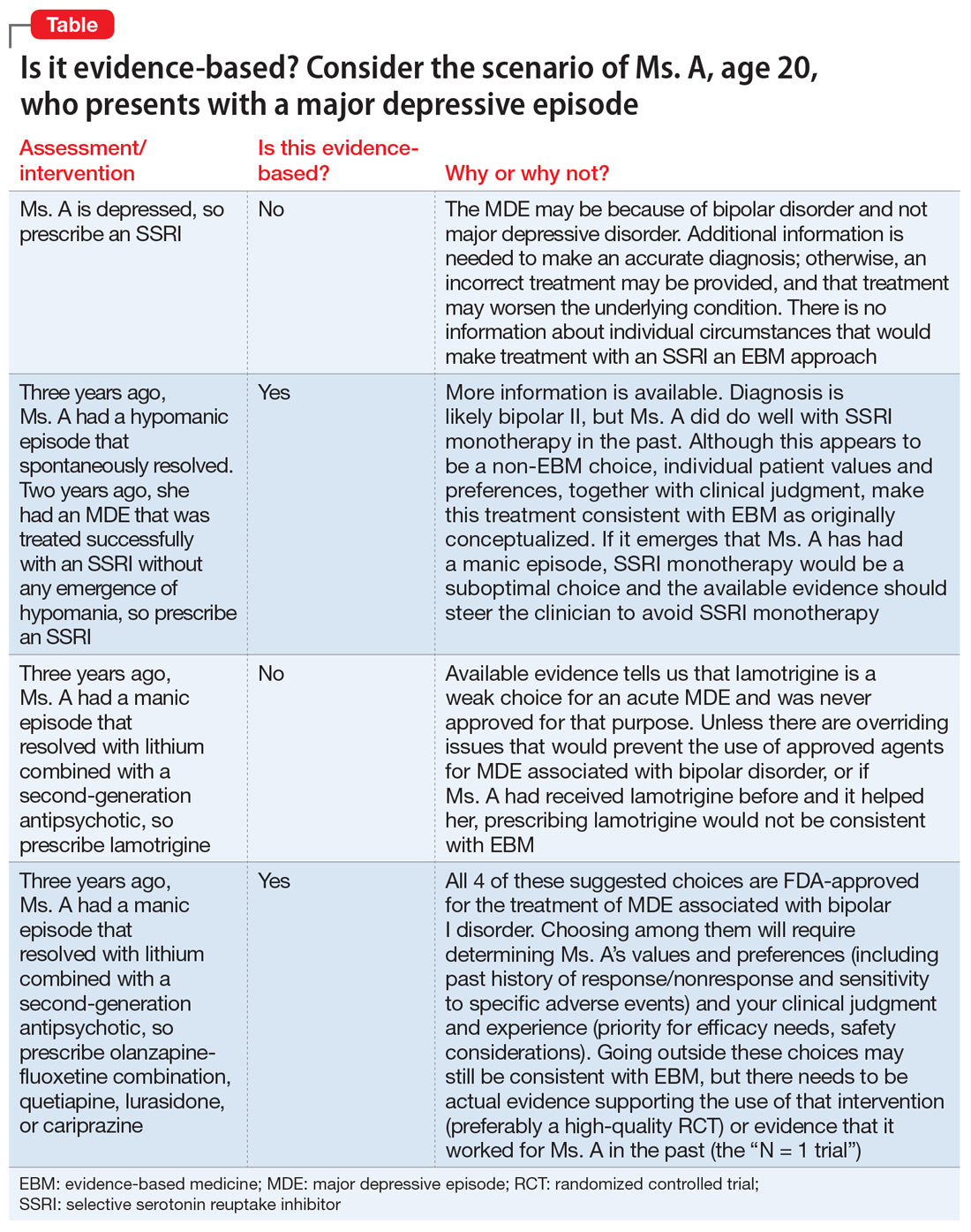

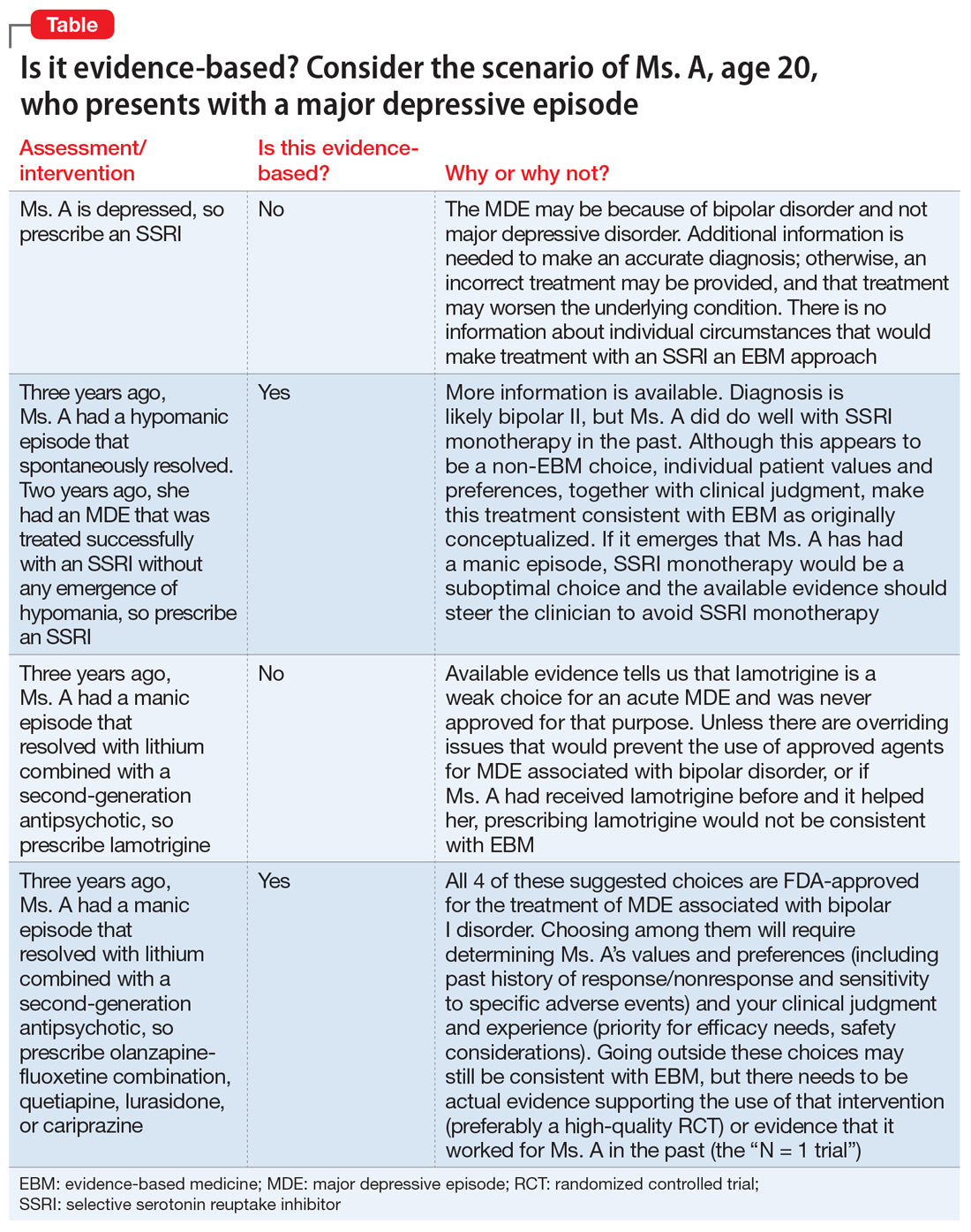

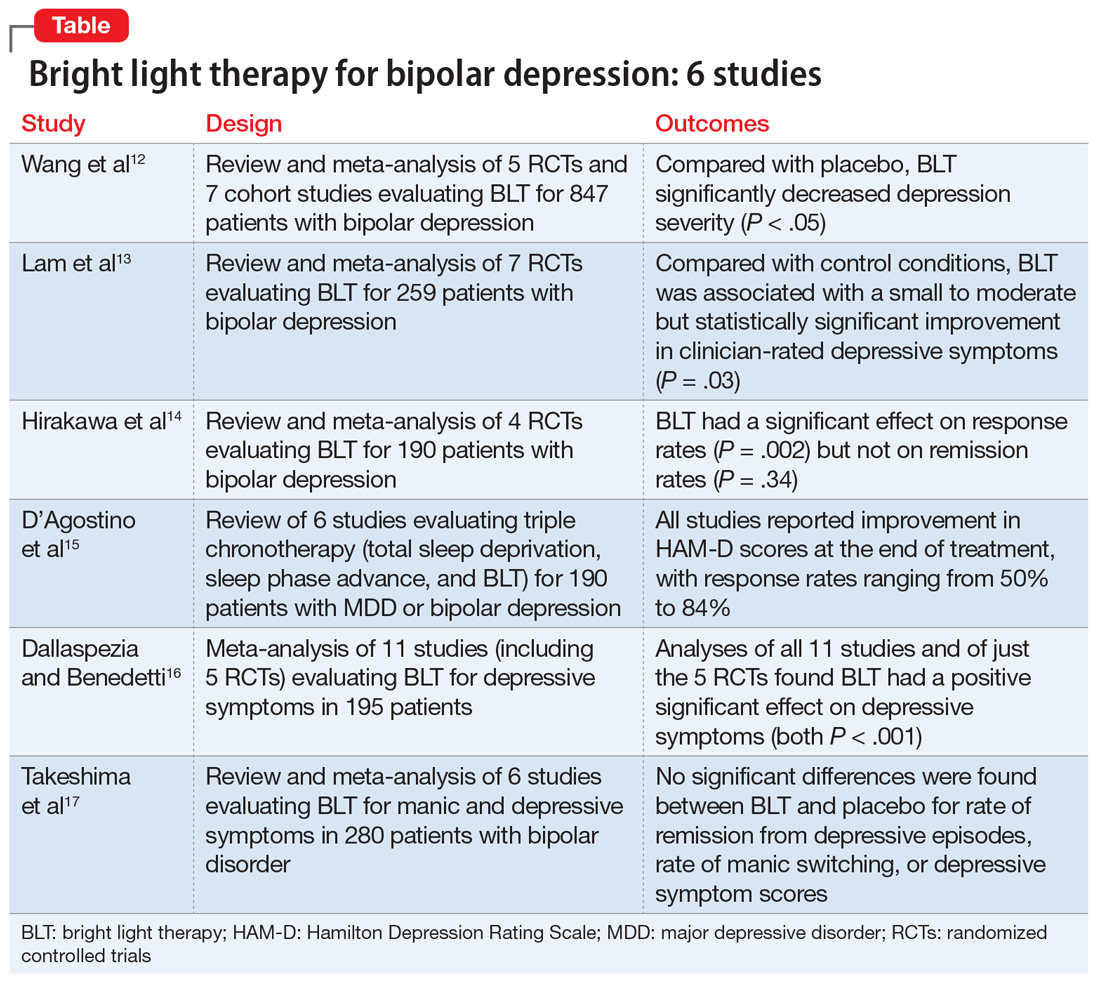

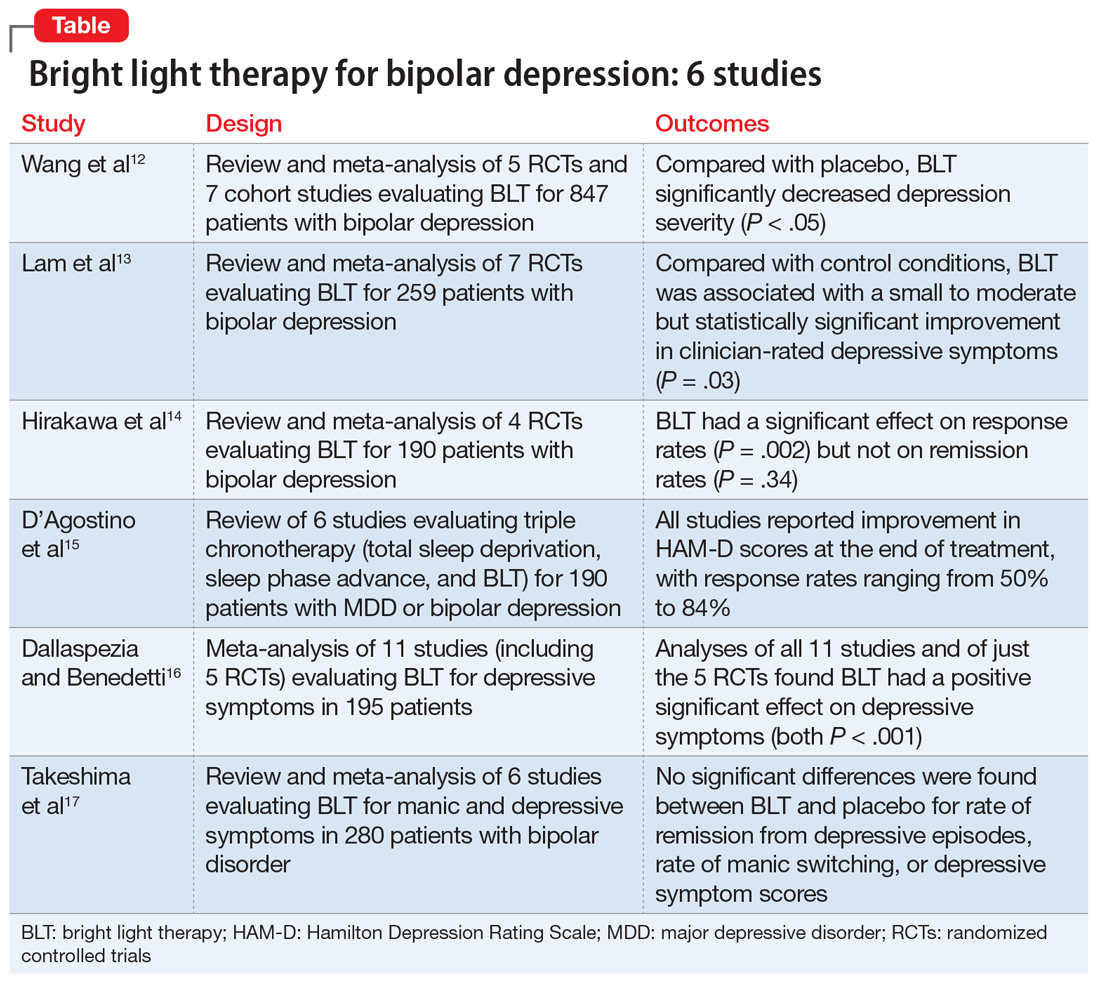

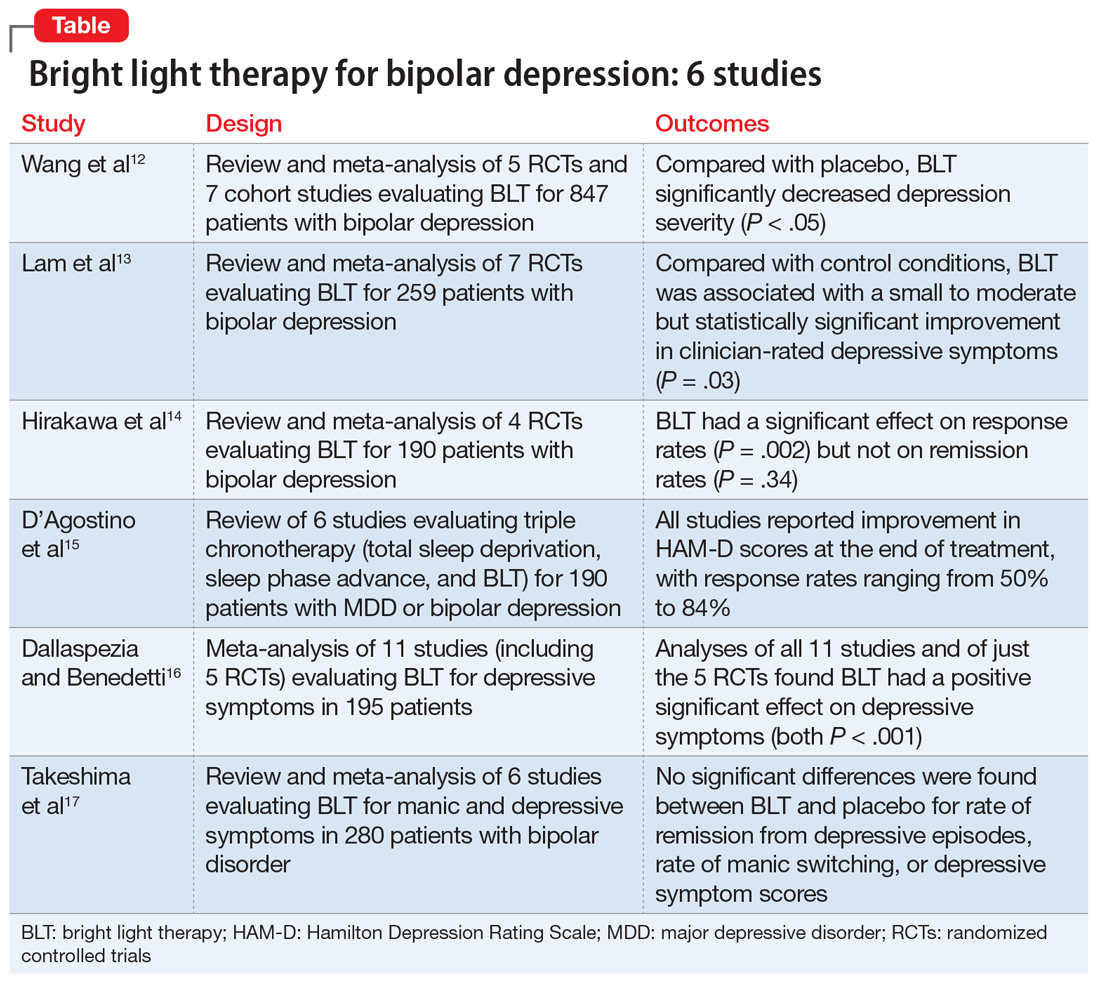

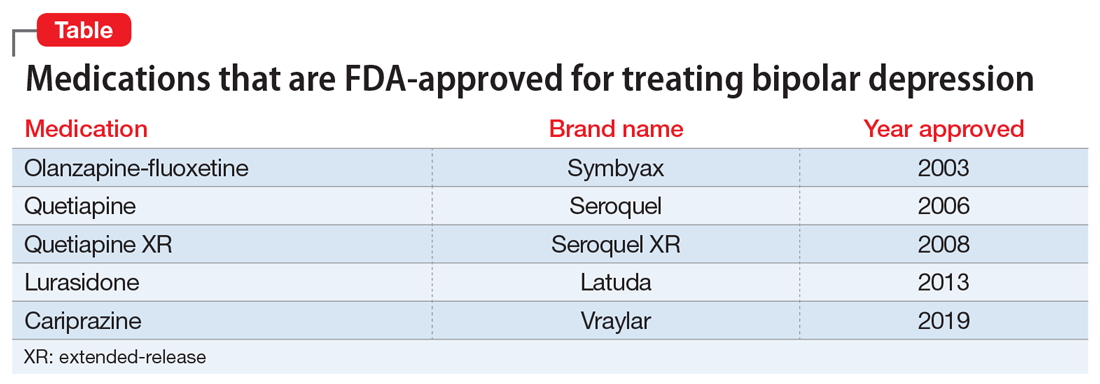

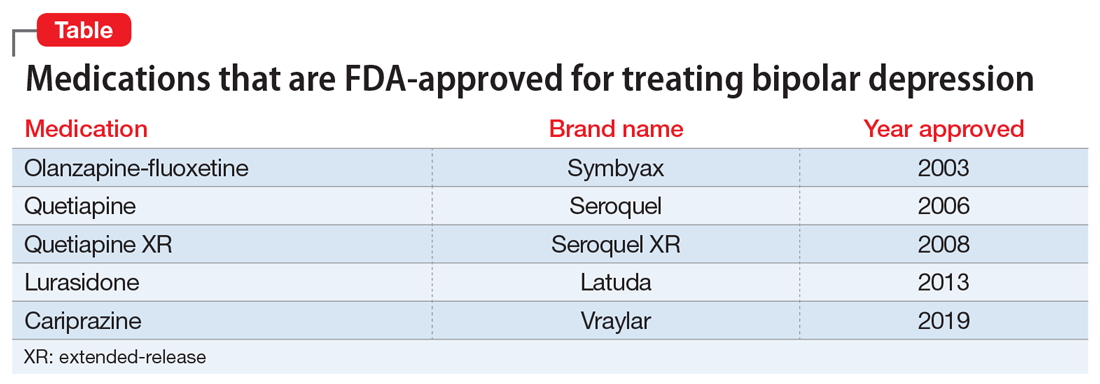

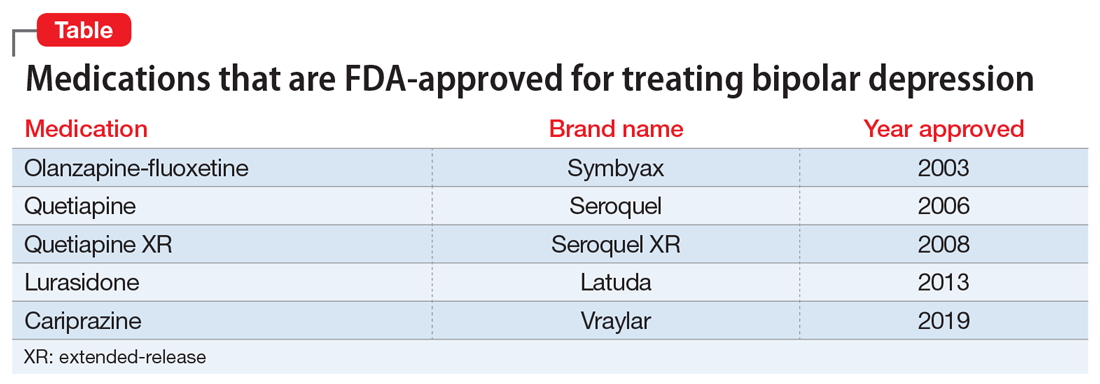

There are common clinical scenarios where evidence is ignored, or where it is overvalued. For example, the treatment of bipolar depression can be made worse with the use of antidepressants.14 Does this mean that antidepressants should never be used? What about patient history and preference? What if the approved agents fail to relieve symptoms or are not well tolerated? Available FDA-approved choices may not always be suitable.15 The Table illustrates some of these scenarios.

1. Citrome L. Evidence-based medicine: it’s not just about the evidence. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65(6):634-635.

2. Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71.

3. Citrome L. Think Bayesian, think smarter! Int J Clin Pract. 2019;73(4):e13351. doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.13351

4. Sackett DL. Evidence-based medicine. Semin Perinatol. 1997;21(1):3-5.

5. Cohen AM, Stavri PZ, Hersh WR. A categorization and analysis of the criticisms of evidence-based medicine. Int J Med Inform. 2004;73(1):35-43.

6. Dutton DB. Worse than the disease: pitfalls of medical progress. Cambridge University Press; 1988.

7. Maggio LA. Educating physicians in evidence based medicine: current practices and curricular strategies. Perspect Med Educ. 2016;5(6):358-361.

8. Citrome L, Ketter TA. Teaching the philosophy and tools of evidence-based medicine: misunderstandings and solutions. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63(3):353-359.

9. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Common Program Requirements (Residency). Revised February 3, 2020. Accessed March 30, 2021. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRResidency2020.pdf

10. Citrome L, Ellison JM. Show me the evidence! Understanding the philosophy of evidence-based medicine and interpreting clinical trials. In: Glick ID, Macaluso M (Chair, Co-chair). ASCP model psychopharmacology curriculum for training directors and teachers of psychopharmacology in psychiatric residency programs, 10th ed. American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology; 2019.

11. Citrome L. Interpreting and applying the CATIE results: with CATIE, context is key, when sorting out Phases 1, 1A, 1B, 2E, and 2T. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2007;4(10):23-29.

12. Citrome L, Stroup TS. Schizophrenia, clinical antipsychotic trials of intervention effectiveness (CATIE) and number needed to treat: how can CATIE inform clinicians? Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60(8):933-940. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01044.x

13. Citrome L. Dissecting clinical trials with ‘number needed to treat’. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):66-71.

14. Goldberg JF, Freeman MP, Balon R, et al. The American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology survey of psychopharmacologists’ practice patterns for the treatment of mood disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(8):605-613.

15. Citrome L. Food and Drug Administration-approved treatments for acute bipolar depression: what we have and what we need. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;40(4):334-338.

The term evidence-based medicine (EBM) has been derided by some as “cookbook medicine.” To others, EBM conjures up the efforts of describing interventions in terms of comparative effectiveness, drowning us in a deluge of “evidence-based” publications. The moniker has also been hijacked by companies to name their Health Economics and Outcomes research divisions. The spirit behind EBM is getting lost. EBM is not just about the evidence; it is about how we use it.1

In this commentary, we describe the concept of EBM and discuss teaching EBM to medical students and residents, its role in continuing medical education, and how it may be applied to practice, using a case scenario as a guide.

What is evidence-based medicine?

Sackett et al2 summed it best in an editorial published in the BMJ in 1996, where he emphasized decision-making in the care of individual patients. When making clinical decisions, using the best evidence available makes sense, but so does integrating individual clinical expertise and considering the individual patient’s preferences. Sackett et al2 warns about practice becoming tyrannized by evidence: “even excellent external evidence may be inapplicable to or inappropriate for an individual patient.” Clearly, EBM is not cookbook medicine.

Figure 13 illustrates EBM as the confluence of clinical judgment, relevant scientific evidence, and patients’ values and preferences. The results from a clinical trial are only one part of the equation. As practitioners, we have the advantage of detailed knowledge about the patient, and our decisions are not “one size fits all.” Prior information about the patient dictates how we apply the evidence that supports potential interventions.

The concept of EBM was born out of necessity to bring scientific principles into the heart of medicine. As outlined by Sackett,4 the practice of EBM is a process of lifelong, self-directed learning in which caring for our own patients creates the need for clinically important information about diagnosis, prognosis, therapy, and other clinical and health care issues. Through EBM, we:

- convert these information needs into answerable questions

- track down, with maximum efficiency, the best evidence with which to answer questions (whether from clinical examination, diagnostic laboratory results, research evidence, or other sources)

- critically appraise that evidence for its validity (closeness to the truth) and usefulness (clinical applicability)

- integrate this appraisal with our clinical expertise and apply it in practice

- evaluate our performance.

Over the years, the original aim of EBM as a self-directed method for clinicians to practice high-quality medicine was morphed by some into a tool of enforced standardization and a boilerplate approach to managing costs across systems of care. As a result, the term EBM has been criticized because of:

- its reliance on empiricism

- a narrow definition of evidence

- a lack of evidence of efficacy

- its limited usefulness for individual patients

- threats to the autonomy of the doctor-patient relationship.

These 5 categories are associated with severe drawbacks when used for individual patient care.5 In addition to problems with applying standardized population research to a specific patient with a specific set of symptoms, medications, genetic variations, and unique environment, it can take years for clinicians to change their practices to incorporate new information.6

Continue to: Evidence that is too narrow...

Evidence that is too narrow in scope may not be useful. Single-molecule pharmaceutical clinical trials have erroneously become a synonym of EBM. Such studies do not reflect complex, real-life situations. Based on such studies, FDA product labeling can be inadequate in its guidance, particularly when faced with complex comorbidities. The standard comparison of active treatment to placebo is also seen as EBM, narrowing its scope and deflecting from clinical medicine when physicians measure one treatment’s success against another vs measuring real treatments against shams. Real-life treatment choice is frequently based on considering adverse effects as important to consider as therapeutic efficacy; however, this concept is outside of the common (mis)understanding of EBM.

Conflicting and ever-changing data and the push to replace clinical thinking with general dogmas trivializes medical practice and endangers treatment outcomes. This would not happen to the extent we see now if EBM was again seen as a guide and general direction rather than a blanket, distorted requirement to follow rigid recommendations for specific patients.

Insurance companies have driven a change in the understanding of EBM by using the FDA label as an excuse to deny, delay, and/or refuse to pay for treatments that are not explicitly and narrowly on-label. Dependence on on-label treatments is even more challenging in specialty medicine because primary care clinicians generally have tried the conventional approaches before referring patients to a specialist. However, insurance denials rarely differentiate between practice settings.

Medicolegal issues have cemented the present situation when clinically valid “off-label” treatments may be a reasonable consideration for patients but can place health care practitioners in jeopardy. The distorted EBM doctrine has become a justification for legal actions against clinicians who practice individualized medicine.

Concision bias (selectively focusing on information, losing nuance) and selection bias (patients in clinical trials who do not reflect real-life patients) have become an impediment to progress and EBM as originally intended.

Continue to: Training medical students and residents

Training medical students and residents

Although there is some variation in how EBM is taught to medical students and residents,7,8 the expectation is that such education occurs. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements for a residency program state that “the program must advance residents’ knowledge and practice of the scholarly approach to evidence-based patient care.”9 The topic has been part of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology Model Psychopharmacology Curriculum, but only in an optional lecture.10 The formal teaching of EBM includes how to find relevant biomedical publications for the clinical issues at hand, understand the different hierarchies of evidence, interpret results in terms of effect size, and apply this knowledge in the care of patients. This 5-step process is illustrated in Figure 28. See Related Resources for 3 books that provide a scholarly yet clinically relevant approach to EBM.

Continuing medical education

Most

Practical applications

There are common clinical scenarios where evidence is ignored, or where it is overvalued. For example, the treatment of bipolar depression can be made worse with the use of antidepressants.14 Does this mean that antidepressants should never be used? What about patient history and preference? What if the approved agents fail to relieve symptoms or are not well tolerated? Available FDA-approved choices may not always be suitable.15 The Table illustrates some of these scenarios.

The term evidence-based medicine (EBM) has been derided by some as “cookbook medicine.” To others, EBM conjures up the efforts of describing interventions in terms of comparative effectiveness, drowning us in a deluge of “evidence-based” publications. The moniker has also been hijacked by companies to name their Health Economics and Outcomes research divisions. The spirit behind EBM is getting lost. EBM is not just about the evidence; it is about how we use it.1

In this commentary, we describe the concept of EBM and discuss teaching EBM to medical students and residents, its role in continuing medical education, and how it may be applied to practice, using a case scenario as a guide.

What is evidence-based medicine?

Sackett et al2 summed it best in an editorial published in the BMJ in 1996, where he emphasized decision-making in the care of individual patients. When making clinical decisions, using the best evidence available makes sense, but so does integrating individual clinical expertise and considering the individual patient’s preferences. Sackett et al2 warns about practice becoming tyrannized by evidence: “even excellent external evidence may be inapplicable to or inappropriate for an individual patient.” Clearly, EBM is not cookbook medicine.

Figure 13 illustrates EBM as the confluence of clinical judgment, relevant scientific evidence, and patients’ values and preferences. The results from a clinical trial are only one part of the equation. As practitioners, we have the advantage of detailed knowledge about the patient, and our decisions are not “one size fits all.” Prior information about the patient dictates how we apply the evidence that supports potential interventions.

The concept of EBM was born out of necessity to bring scientific principles into the heart of medicine. As outlined by Sackett,4 the practice of EBM is a process of lifelong, self-directed learning in which caring for our own patients creates the need for clinically important information about diagnosis, prognosis, therapy, and other clinical and health care issues. Through EBM, we:

- convert these information needs into answerable questions

- track down, with maximum efficiency, the best evidence with which to answer questions (whether from clinical examination, diagnostic laboratory results, research evidence, or other sources)

- critically appraise that evidence for its validity (closeness to the truth) and usefulness (clinical applicability)

- integrate this appraisal with our clinical expertise and apply it in practice

- evaluate our performance.

Over the years, the original aim of EBM as a self-directed method for clinicians to practice high-quality medicine was morphed by some into a tool of enforced standardization and a boilerplate approach to managing costs across systems of care. As a result, the term EBM has been criticized because of:

- its reliance on empiricism

- a narrow definition of evidence

- a lack of evidence of efficacy

- its limited usefulness for individual patients

- threats to the autonomy of the doctor-patient relationship.

These 5 categories are associated with severe drawbacks when used for individual patient care.5 In addition to problems with applying standardized population research to a specific patient with a specific set of symptoms, medications, genetic variations, and unique environment, it can take years for clinicians to change their practices to incorporate new information.6

Continue to: Evidence that is too narrow...

Evidence that is too narrow in scope may not be useful. Single-molecule pharmaceutical clinical trials have erroneously become a synonym of EBM. Such studies do not reflect complex, real-life situations. Based on such studies, FDA product labeling can be inadequate in its guidance, particularly when faced with complex comorbidities. The standard comparison of active treatment to placebo is also seen as EBM, narrowing its scope and deflecting from clinical medicine when physicians measure one treatment’s success against another vs measuring real treatments against shams. Real-life treatment choice is frequently based on considering adverse effects as important to consider as therapeutic efficacy; however, this concept is outside of the common (mis)understanding of EBM.

Conflicting and ever-changing data and the push to replace clinical thinking with general dogmas trivializes medical practice and endangers treatment outcomes. This would not happen to the extent we see now if EBM was again seen as a guide and general direction rather than a blanket, distorted requirement to follow rigid recommendations for specific patients.

Insurance companies have driven a change in the understanding of EBM by using the FDA label as an excuse to deny, delay, and/or refuse to pay for treatments that are not explicitly and narrowly on-label. Dependence on on-label treatments is even more challenging in specialty medicine because primary care clinicians generally have tried the conventional approaches before referring patients to a specialist. However, insurance denials rarely differentiate between practice settings.

Medicolegal issues have cemented the present situation when clinically valid “off-label” treatments may be a reasonable consideration for patients but can place health care practitioners in jeopardy. The distorted EBM doctrine has become a justification for legal actions against clinicians who practice individualized medicine.

Concision bias (selectively focusing on information, losing nuance) and selection bias (patients in clinical trials who do not reflect real-life patients) have become an impediment to progress and EBM as originally intended.

Continue to: Training medical students and residents

Training medical students and residents

Although there is some variation in how EBM is taught to medical students and residents,7,8 the expectation is that such education occurs. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements for a residency program state that “the program must advance residents’ knowledge and practice of the scholarly approach to evidence-based patient care.”9 The topic has been part of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology Model Psychopharmacology Curriculum, but only in an optional lecture.10 The formal teaching of EBM includes how to find relevant biomedical publications for the clinical issues at hand, understand the different hierarchies of evidence, interpret results in terms of effect size, and apply this knowledge in the care of patients. This 5-step process is illustrated in Figure 28. See Related Resources for 3 books that provide a scholarly yet clinically relevant approach to EBM.

Continuing medical education

Most

Practical applications

There are common clinical scenarios where evidence is ignored, or where it is overvalued. For example, the treatment of bipolar depression can be made worse with the use of antidepressants.14 Does this mean that antidepressants should never be used? What about patient history and preference? What if the approved agents fail to relieve symptoms or are not well tolerated? Available FDA-approved choices may not always be suitable.15 The Table illustrates some of these scenarios.

1. Citrome L. Evidence-based medicine: it’s not just about the evidence. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65(6):634-635.

2. Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71.

3. Citrome L. Think Bayesian, think smarter! Int J Clin Pract. 2019;73(4):e13351. doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.13351

4. Sackett DL. Evidence-based medicine. Semin Perinatol. 1997;21(1):3-5.

5. Cohen AM, Stavri PZ, Hersh WR. A categorization and analysis of the criticisms of evidence-based medicine. Int J Med Inform. 2004;73(1):35-43.

6. Dutton DB. Worse than the disease: pitfalls of medical progress. Cambridge University Press; 1988.

7. Maggio LA. Educating physicians in evidence based medicine: current practices and curricular strategies. Perspect Med Educ. 2016;5(6):358-361.

8. Citrome L, Ketter TA. Teaching the philosophy and tools of evidence-based medicine: misunderstandings and solutions. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63(3):353-359.

9. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Common Program Requirements (Residency). Revised February 3, 2020. Accessed March 30, 2021. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRResidency2020.pdf

10. Citrome L, Ellison JM. Show me the evidence! Understanding the philosophy of evidence-based medicine and interpreting clinical trials. In: Glick ID, Macaluso M (Chair, Co-chair). ASCP model psychopharmacology curriculum for training directors and teachers of psychopharmacology in psychiatric residency programs, 10th ed. American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology; 2019.

11. Citrome L. Interpreting and applying the CATIE results: with CATIE, context is key, when sorting out Phases 1, 1A, 1B, 2E, and 2T. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2007;4(10):23-29.

12. Citrome L, Stroup TS. Schizophrenia, clinical antipsychotic trials of intervention effectiveness (CATIE) and number needed to treat: how can CATIE inform clinicians? Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60(8):933-940. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01044.x

13. Citrome L. Dissecting clinical trials with ‘number needed to treat’. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):66-71.

14. Goldberg JF, Freeman MP, Balon R, et al. The American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology survey of psychopharmacologists’ practice patterns for the treatment of mood disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(8):605-613.

15. Citrome L. Food and Drug Administration-approved treatments for acute bipolar depression: what we have and what we need. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;40(4):334-338.

1. Citrome L. Evidence-based medicine: it’s not just about the evidence. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65(6):634-635.

2. Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71.

3. Citrome L. Think Bayesian, think smarter! Int J Clin Pract. 2019;73(4):e13351. doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.13351

4. Sackett DL. Evidence-based medicine. Semin Perinatol. 1997;21(1):3-5.

5. Cohen AM, Stavri PZ, Hersh WR. A categorization and analysis of the criticisms of evidence-based medicine. Int J Med Inform. 2004;73(1):35-43.

6. Dutton DB. Worse than the disease: pitfalls of medical progress. Cambridge University Press; 1988.

7. Maggio LA. Educating physicians in evidence based medicine: current practices and curricular strategies. Perspect Med Educ. 2016;5(6):358-361.

8. Citrome L, Ketter TA. Teaching the philosophy and tools of evidence-based medicine: misunderstandings and solutions. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63(3):353-359.

9. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Common Program Requirements (Residency). Revised February 3, 2020. Accessed March 30, 2021. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRResidency2020.pdf

10. Citrome L, Ellison JM. Show me the evidence! Understanding the philosophy of evidence-based medicine and interpreting clinical trials. In: Glick ID, Macaluso M (Chair, Co-chair). ASCP model psychopharmacology curriculum for training directors and teachers of psychopharmacology in psychiatric residency programs, 10th ed. American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology; 2019.

11. Citrome L. Interpreting and applying the CATIE results: with CATIE, context is key, when sorting out Phases 1, 1A, 1B, 2E, and 2T. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2007;4(10):23-29.

12. Citrome L, Stroup TS. Schizophrenia, clinical antipsychotic trials of intervention effectiveness (CATIE) and number needed to treat: how can CATIE inform clinicians? Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60(8):933-940. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01044.x

13. Citrome L. Dissecting clinical trials with ‘number needed to treat’. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):66-71.

14. Goldberg JF, Freeman MP, Balon R, et al. The American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology survey of psychopharmacologists’ practice patterns for the treatment of mood disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(8):605-613.

15. Citrome L. Food and Drug Administration-approved treatments for acute bipolar depression: what we have and what we need. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;40(4):334-338.

10 devastating consequences of psychotic relapses

It breaks my heart every time young patients with functional disability and a history of several psychotic episodes are referred to me. It makes me wonder why they weren’t protected from a lifetime of disability with the use of one of the FDA-approved long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics right after discharge from their initial hospitalization for first-episode psychosis (FEP).

Two decades ago, psychiatric research discovered that psychotic episodes are neurotoxic and neurodegenerative, with grave consequences for the brain if they recur. Although many clinicians are aware of the high rate of nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia—which inevitably leads to a psychotic relapse—the vast majority (>99%, in my estimate) never prescribe an LAI after the FEP to guarantee full adherence and protect the patient’s brain from further atrophy due to relapses. The overall rate of LAI antipsychotic use is astonishingly low (approximately 10%), despite the neurologic malignancy of psychotic episodes. Further, LAIs are most often used after a patient has experienced multiple psychotic episodes, at which point the patient has already lost a significant amount of brain tissue and has already descended into a life of permanent disability.

Oral antipsychotics have the same efficacy as their LAI counterparts, and certainly should be used initially in the hospital during FEP to ascertain the absence of an allergic reaction after initial exposure, and to establish tolerability. Inpatient nurses are experts at making sure a reluctant patient actually swallows the pills and does not cheek them to spit them out later. So patients who have had FEP do improve with oral medications in the hospital, but all bets are off that those patients will regularly ingest tablets every day after discharge. Studies show patients have a high rate of nonadherence within days or weeks after leaving the hospital for FEP.1 This leads to repetitive psychotic relapses and rehospitalizations, with dire consequences for young patients with schizophrenia—a very serious brain disorder that had been labeled “the worst disease of mankind”2 in the era before studies showed LAI second-generation antipsychotics for FEP had remarkable rates of relapse prevention and recovery.3,4

Psychiatrists should approach FEP the same way oncologists approach cancer when it is diagnosed as Stage 1. Oncologists immediately take action to prevent the recurrence of the patient’s cancer with chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, and do not wait for the cancer to advance to Stage 4, with widespread metastasis, before administering these potentially life-saving therapies (despite their toxic adverse effects). In schizophrenia, functional disability is the equivalent of Stage 4 cancer and should be aggressively prevented by using LAIs at the time of initial diagnosis, which is Stage 1 schizophrenia. Knowing the grave consequences of psychotic relapses, there is no logical reason whatsoever not to switch patients who have had FEP to an LAI before they are discharged from the hospital. A well-known study by a UCLA research group that compared patients who had FEP and were assigned to oral vs LAI antipsychotics at the time of discharge reported a stunning difference at the end of 1 year: a 650% higher relapse rate among the oral medication group compared with the LAI group!5 In light of such a massive difference, wouldn’t psychiatrists want to treat their sons or daughters with an LAI antipsychotic right after FEP? I certainly would, and I have always believed in treating every patient like a family member.

Catastrophic consequences

This lack of early intervention with LAI antipsychotics following FEP is the main reason schizophrenia is associated with poor clinical and functional outcomes. Patients are prescribed pills that they often take erratically or not at all, and end up relapsing repeatedly, with multiple catastrophic consequences, such as:

1. Brain tissue loss. Until recently, psychiatry did not know that psychosis destroys gray and white matter in the brain and causes progressive brain atrophy with every psychotic relapse.6,7 The neurotoxicity of psychosis is attributed to 2 destructive processes: neuroinflammation8,9 and free radicals.10 Approximately 11 cc of brain tissue is lost during FEP and with every subsequent relapse.6 Simple math shows that after 3 to 5 relapses, patients’ brains will shrink by 35 cc to 60 cc. No wonder recurrent psychoses lead to a life of permanent disability. As I have said in a past editorial,11 just as cardiologists do everything they can to prevent a second myocardial infarction (“heart attack”), psychiatrists must do the same to prevent a second psychotic episode (“brain attack”).

2. Treatment resistance. With each psychotic episode, the low antipsychotic dose that worked well in FEP is no longer enough and must be increased. The neurodegenerative effects of psychosis implies that the brain structure changes with each episode. Higher and higher doses become necessary with every psychotic recurrence, and studies show that approximately 1 in 8 patients may stop responding altogether after a psychotic relapse.12

Continue to: Disability

3. Disability. Functional disability, both vocational and social, usually begins after the second psychotic episode, which is why it is so important to prevent the second episode.13 Patients usually must drop out of high school or college or quit the job they held before FEP. Most patients with multiple psychotic episodes will never be able to work, get married, have children, live independently, or develop a circle of friends. Disability in schizophrenia is essentially a functional death sentence.14

4. Incarceration and criminalization. So many of our patients with schizophrenia get arrested when they become psychotic and behave erratically due to delusions, hallucinations, or both. They typically are taken to jail instead of a hospital because almost all the state hospitals around the country have been closed. It is outrageous that a medical condition of the brain leads to criminalization of patients with schizophrenia.15 The only solution for this ongoing crisis of incarceration of our patients with schizophrenia is to prevent them from relapsing into psychosis. The so-called deinstitutionalization movement has mutated into trans-institutionalization, moving patients who are medically ill from state hospitals to more restrictive state prisons. Patients with schizophrenia should be surrounded by a mental health team, not by armed prison guards. The rate of recidivism among these individuals is extremely high because patients who are released often stop taking their medications and get re-arrested when their behavior deteriorates.

5. Suicide. The rate of suicide in the first year after FEP is astronomical. A recent study reported an unimaginably high suicide rate: 17,000% higher than that of the general population.16 Many patients with FEP commit suicide after they stop taking their antipsychotic medication, and often no antipsychotic medication is detected in their postmortem blood samples.

6. Homelessness. A disproportionate number of patients with schizophrenia become homeless.17 It started in the 1980s, when the shuttering of state hospitals began and patients with chronic illnesses were released into the community to fend for themselves. Many perished. Others became homeless, living on the streets of urban areas.

7. Early mortality. Schizophrenia has repeatedly been shown to be associated with early mortality, with a loss of approximately 25 potential years of life.17 This is attributed to lifestyle risk factors (eg, sedentary living, poor diet) and multiple medical comorbidities (eg, obesity, diabetes, hypertension). To make things worse, patients with schizophrenia do not receive basic medical care to protect them from cardiovascular morbidity, an appalling disparity of care.18 Interestingly, a recent 7-year follow-up study of patients with schizophrenia found that the lowest rate of mortality from all causes was among patients receiving a second-generation LAI.19 Relapse prevention with LAIs can reduce mortality! According to that study, the worst mortality rate was observed in patients with schizophrenia who were not receiving any antipsychotic medication.

Continue to: Posttraumatic stress disorder

8. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Many studies report that psychosis triggers PTSD symptoms20 because delusions and hallucinations can represent a life-threatening experience. The symptoms of PTSD get embedded within the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, and every psychotic relapse serves as a “booster shot” for PTSD, leading to depression, anxiety, personality changes, aggressive behavior, and suicide.

9. Hopelessness, depression, and demoralization. The stigma of a severe psychiatric brain disorder such as schizophrenia, with multiple episodes, disability, incarceration, and homelessness, extends to the patients themselves, who become hopeless and demoralized by a chronic illness that marginalizes them into desperately ill individuals.21 The more psychotic episodes, the more intense the demoralization, hopelessness, and depression.

10. Family burden. The repercussions of psychotic relapses after FEP leads to significant financial and emotional stress on patients’ families.22 The heavy burden of caregiving among family members can be highly distressing, leading to depression and medical illness due to compromised immune functions.

Preventing relapse: It is not rocket science