User login

I STEP: Recognizing cognitive distortions in posttraumatic stress disorder

Evidence-based cognitive-behavioral therapies for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may employ cognitive restructuring. This psychotherapeutic technique entails recognizing and correcting maladaptive, inaccurate thoughts that perpetuate illness.1 For example, a clinician helps a patient recognize that the negative thought “Nobody loves me” following a romantic breakup is an overgeneralization. The patient is taught to self-correct this to “While my ex-girlfriend doesn’t love me, others do. It only feels like nobody loves me.”2

We introduce the acronym I STEP to help clinicians recognize several common distorted thoughts in PTSD. These tend to occur within stereotyped themes in PTSD,3 as outlined and illustrated below. Recognizing distorted thoughts in these patients will help clinicians understand and address psychological distress following trauma.

Intimacy/In-touch. Intimacy involves comfort in relationships, including but not limited to sexual intimacy. This requires being in touch emotionally with self and others. In trauma involving loss, fear of further loss may impair intimacy with others. Difficulty with self-intimacy impairs commitment to life’s goals and prompts unhelpful avoidance behaviors, such as difficulty being alone or self-injurious use of drugs or alcohol. Comfort in spending some portion of time alone with one’s thoughts and emotions is a life skill necessary to attain optimum function. Patients who are unable to tolerate their own emotions without constant company might have excessive anxiety when social supports are otherwise occupied. Such patients might seek excessive and repeated reassurance rather than learning to tolerate their own emotions and thoughts. They would then find it difficult to engage successfully in solo activities.

Safety. After trauma, patients may view themselves and others as unsafe, and may overestimate risk. For example, a pedestrian who is struck by a vehicle may believe that crossing a street will again result in getting hit by a car without appreciating that people frequently cross streets without injury or that crossing cautiously is an essential life skill. Parents who have suffered from trauma may unduly believe that their children are in danger when engaging in an activity generally considered to be safe. This may create challenges in parenting and impede their children’s ability to develop a sense of independence.

Trust. Trauma victims may unfairly blame themselves, leading them to mistrust their own judgment. Such patients may have difficulty making decisions confidently and independently, such as choosing a job or a romantic partner. When traumatized by another person or people, it can be difficult to maintain positive views of others or to accept others’ positive behaviors as genuine. For example, a common reaction following rape may be a generalized mistrust of all men.

Esteem. Patients’ self-esteem may suffer following trauma due to irrational self-blame or believing the “just world hypothesis”—the idea that bad things only happen to bad people. For example, a patient who suffers an assault by an acquaintance might think “I must be stupid if I couldn’t figure out that my friend was dangerous.”

Power. Traumatic events usually occur outside of one’s control. Survivors of trauma may lose confidence in their ability to control any aspect of their lives. Conversely, they may attempt to gain control of all of life’s circumstances, including those that are beyond anyone’s control. Control can be applied to emotions, behaviors, or events. A driver struck by a vehicle may think “I can’t control other drivers, so I have no power to control my safety while driving,” and hence give up driving. While there are things that are beyond our control, this extreme thought ignores things that we can control, such as wearing seatbelts or having the vehicle’s brakes regularly serviced.

1. Wenzel A. Basic strategies of cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2017;40(4):597-609.

2. Beck J. Cognitive behavioral therapy: basics and beyond. 2nd ed. The Guilford Press; 2011.

3. Resick PA, Monson CM, Chard KM. Cognitive processing therapy for PTSD. A comprehensive manual. The Guilford Press; 2017.

Evidence-based cognitive-behavioral therapies for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may employ cognitive restructuring. This psychotherapeutic technique entails recognizing and correcting maladaptive, inaccurate thoughts that perpetuate illness.1 For example, a clinician helps a patient recognize that the negative thought “Nobody loves me” following a romantic breakup is an overgeneralization. The patient is taught to self-correct this to “While my ex-girlfriend doesn’t love me, others do. It only feels like nobody loves me.”2

We introduce the acronym I STEP to help clinicians recognize several common distorted thoughts in PTSD. These tend to occur within stereotyped themes in PTSD,3 as outlined and illustrated below. Recognizing distorted thoughts in these patients will help clinicians understand and address psychological distress following trauma.

Intimacy/In-touch. Intimacy involves comfort in relationships, including but not limited to sexual intimacy. This requires being in touch emotionally with self and others. In trauma involving loss, fear of further loss may impair intimacy with others. Difficulty with self-intimacy impairs commitment to life’s goals and prompts unhelpful avoidance behaviors, such as difficulty being alone or self-injurious use of drugs or alcohol. Comfort in spending some portion of time alone with one’s thoughts and emotions is a life skill necessary to attain optimum function. Patients who are unable to tolerate their own emotions without constant company might have excessive anxiety when social supports are otherwise occupied. Such patients might seek excessive and repeated reassurance rather than learning to tolerate their own emotions and thoughts. They would then find it difficult to engage successfully in solo activities.

Safety. After trauma, patients may view themselves and others as unsafe, and may overestimate risk. For example, a pedestrian who is struck by a vehicle may believe that crossing a street will again result in getting hit by a car without appreciating that people frequently cross streets without injury or that crossing cautiously is an essential life skill. Parents who have suffered from trauma may unduly believe that their children are in danger when engaging in an activity generally considered to be safe. This may create challenges in parenting and impede their children’s ability to develop a sense of independence.

Trust. Trauma victims may unfairly blame themselves, leading them to mistrust their own judgment. Such patients may have difficulty making decisions confidently and independently, such as choosing a job or a romantic partner. When traumatized by another person or people, it can be difficult to maintain positive views of others or to accept others’ positive behaviors as genuine. For example, a common reaction following rape may be a generalized mistrust of all men.

Esteem. Patients’ self-esteem may suffer following trauma due to irrational self-blame or believing the “just world hypothesis”—the idea that bad things only happen to bad people. For example, a patient who suffers an assault by an acquaintance might think “I must be stupid if I couldn’t figure out that my friend was dangerous.”

Power. Traumatic events usually occur outside of one’s control. Survivors of trauma may lose confidence in their ability to control any aspect of their lives. Conversely, they may attempt to gain control of all of life’s circumstances, including those that are beyond anyone’s control. Control can be applied to emotions, behaviors, or events. A driver struck by a vehicle may think “I can’t control other drivers, so I have no power to control my safety while driving,” and hence give up driving. While there are things that are beyond our control, this extreme thought ignores things that we can control, such as wearing seatbelts or having the vehicle’s brakes regularly serviced.

Evidence-based cognitive-behavioral therapies for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may employ cognitive restructuring. This psychotherapeutic technique entails recognizing and correcting maladaptive, inaccurate thoughts that perpetuate illness.1 For example, a clinician helps a patient recognize that the negative thought “Nobody loves me” following a romantic breakup is an overgeneralization. The patient is taught to self-correct this to “While my ex-girlfriend doesn’t love me, others do. It only feels like nobody loves me.”2

We introduce the acronym I STEP to help clinicians recognize several common distorted thoughts in PTSD. These tend to occur within stereotyped themes in PTSD,3 as outlined and illustrated below. Recognizing distorted thoughts in these patients will help clinicians understand and address psychological distress following trauma.

Intimacy/In-touch. Intimacy involves comfort in relationships, including but not limited to sexual intimacy. This requires being in touch emotionally with self and others. In trauma involving loss, fear of further loss may impair intimacy with others. Difficulty with self-intimacy impairs commitment to life’s goals and prompts unhelpful avoidance behaviors, such as difficulty being alone or self-injurious use of drugs or alcohol. Comfort in spending some portion of time alone with one’s thoughts and emotions is a life skill necessary to attain optimum function. Patients who are unable to tolerate their own emotions without constant company might have excessive anxiety when social supports are otherwise occupied. Such patients might seek excessive and repeated reassurance rather than learning to tolerate their own emotions and thoughts. They would then find it difficult to engage successfully in solo activities.

Safety. After trauma, patients may view themselves and others as unsafe, and may overestimate risk. For example, a pedestrian who is struck by a vehicle may believe that crossing a street will again result in getting hit by a car without appreciating that people frequently cross streets without injury or that crossing cautiously is an essential life skill. Parents who have suffered from trauma may unduly believe that their children are in danger when engaging in an activity generally considered to be safe. This may create challenges in parenting and impede their children’s ability to develop a sense of independence.

Trust. Trauma victims may unfairly blame themselves, leading them to mistrust their own judgment. Such patients may have difficulty making decisions confidently and independently, such as choosing a job or a romantic partner. When traumatized by another person or people, it can be difficult to maintain positive views of others or to accept others’ positive behaviors as genuine. For example, a common reaction following rape may be a generalized mistrust of all men.

Esteem. Patients’ self-esteem may suffer following trauma due to irrational self-blame or believing the “just world hypothesis”—the idea that bad things only happen to bad people. For example, a patient who suffers an assault by an acquaintance might think “I must be stupid if I couldn’t figure out that my friend was dangerous.”

Power. Traumatic events usually occur outside of one’s control. Survivors of trauma may lose confidence in their ability to control any aspect of their lives. Conversely, they may attempt to gain control of all of life’s circumstances, including those that are beyond anyone’s control. Control can be applied to emotions, behaviors, or events. A driver struck by a vehicle may think “I can’t control other drivers, so I have no power to control my safety while driving,” and hence give up driving. While there are things that are beyond our control, this extreme thought ignores things that we can control, such as wearing seatbelts or having the vehicle’s brakes regularly serviced.

1. Wenzel A. Basic strategies of cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2017;40(4):597-609.

2. Beck J. Cognitive behavioral therapy: basics and beyond. 2nd ed. The Guilford Press; 2011.

3. Resick PA, Monson CM, Chard KM. Cognitive processing therapy for PTSD. A comprehensive manual. The Guilford Press; 2017.

1. Wenzel A. Basic strategies of cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2017;40(4):597-609.

2. Beck J. Cognitive behavioral therapy: basics and beyond. 2nd ed. The Guilford Press; 2011.

3. Resick PA, Monson CM, Chard KM. Cognitive processing therapy for PTSD. A comprehensive manual. The Guilford Press; 2017.

ARISE to supportive psychotherapy

Supportive psychotherapy is a common type of therapy that often is used in combination with other modalities. By focusing on improving symptoms and accepting the patient’s limitations, it is particularly helpful for individuals who might have difficulty engaging in insight-oriented psychotherapies, such as those struggling with external stressors, including exposure to trauma, bereavement, physical disabilities, or socioeconomic challenges. Personal limitations, including severe personality disorder or intellectual disabilities, might also limit a patient’s ability to self-reflect on subconscious issues, which can lead to choosing a supportive modality.

While being supportive in the vernacular sense can be helpful, formal supportive psychotherapy employs well-defined goals and techniques.1 A therapist can facilitate progress by explicitly referring to these goals and techniques. The acronym ARISE can help therapists and other clinicians to use and appraise therapeutic progress toward these goals.

Alliance-building. The therapeutic alliance is an important predictor of the success of psychotherapy.2 Warmly encourage positive transference toward the therapist. The patient’s appreciation of the therapist’s empathic interactions can further the alliance. Paraphrasing the patient’s words can demonstrate and enhance empathy. Doing so allows clarification of the patient’s thoughts and helps the patient feel understood. Formulate and partner around shared therapeutic goals. Monitor the strength of the alliance and intervene if it is threatened. For example, if you misunderstand your patient and inadvertently offend them, apologizing may be helpful. In the face of disagreement between the patient and therapist, reorienting back to shared goals reinforces common ground.

Reduce anxiety and negative affect. In contrast to the caricature of the stiff psychoanalyst, the supportive therapist adopts an engaged conversational style to help the patient feel relaxed and to diminish the power differential between therapist and patient. If the patient appears uncomfortable with silence, maintaining the flow of conversation may reduce discomfort.1 Minimize your patient’s discomfort by approaching uncomfortable topics in manageable portions. Seek permission before introducing a subject that induces anxiety. Explain the reasoning behind approaching such topics.3 Reassurance and encouragement can further reduce anxiety.4 When not incongruous to the discussion, appropriate use of warm affect (eg, a smile) or even humor can elicit positive affect.

Increase awareness. Use psychoeducation and psychological interpretation (whether cognitive-behavioral or psychodynamic) to expand your patient’s awareness and help them understand their social contacts’ point of view. Clarification, gentle confrontation, and interpretation can make patients aware of biopsychosocial precipitants of distress.4

Strengthen coping mechanisms. Reinforce adaptive defense mechanisms, such as mature humor or suppression. Educating patients on practical organizational skills, problem-solving, relaxation techniques, and other relevant skills, can help them cope more effectively. Give advice only in limited circumstances, and when doing so, back up your advice with a rationale derived from your professional expertise. Because it is important for patients to realize that their life choices are their own, usually it is best to help the patient understand how they might come to their own decisions rather than to prescribe life choices in the form of advice.

Enhance self-esteem. Many patients in distress suffer from low self-esteem.5,6 Active encouragement and honest praise can nurture your patient’s ability to correct a distorted self-image and challenge self-reproach. Praise should not be false but reality-based. Praise can address preexisting strengths, highlight the patient’s willingness to express challenging material, or provide reinforcement on progress made toward treatment goals.

1. Rothe, EM. Supportive psychotherapy in everyday clinical practice: it’s like riding a bicycle. Psychiatric Times. Published May 24, 2017. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/supportive-psychotherapy-everyday-clinical-practice-its-riding-bicycle

2. Flückiger C, Del Re AC, Wampold BE, et al. The alliance in adult psychotherapy: a meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2018;55(4):316-340.

3. Pine F. The interpretive moment. Variations on classical themes. Bull Menninger Clin. 1984;48(1), 54-71.

4. Grover S, Avasthi A, Jagiwala M. Clinical practice guidelines for practice of supportive psychotherapy. Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62(Suppl 2):S173-S182.

5. Leary MR, Schreindorfer LS, Haupt AL. The role of low self-esteem in emotional and behavioral problems: why is low self-esteem dysfunctional? J Soc Clin Psychol. 1995;14(3):297-314.

6. Zahn R, Lythe KE, Gethin JA, et al. The role of self-blame and worthlessness in the psychopathology of major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2015;186:337-341.

Supportive psychotherapy is a common type of therapy that often is used in combination with other modalities. By focusing on improving symptoms and accepting the patient’s limitations, it is particularly helpful for individuals who might have difficulty engaging in insight-oriented psychotherapies, such as those struggling with external stressors, including exposure to trauma, bereavement, physical disabilities, or socioeconomic challenges. Personal limitations, including severe personality disorder or intellectual disabilities, might also limit a patient’s ability to self-reflect on subconscious issues, which can lead to choosing a supportive modality.

While being supportive in the vernacular sense can be helpful, formal supportive psychotherapy employs well-defined goals and techniques.1 A therapist can facilitate progress by explicitly referring to these goals and techniques. The acronym ARISE can help therapists and other clinicians to use and appraise therapeutic progress toward these goals.

Alliance-building. The therapeutic alliance is an important predictor of the success of psychotherapy.2 Warmly encourage positive transference toward the therapist. The patient’s appreciation of the therapist’s empathic interactions can further the alliance. Paraphrasing the patient’s words can demonstrate and enhance empathy. Doing so allows clarification of the patient’s thoughts and helps the patient feel understood. Formulate and partner around shared therapeutic goals. Monitor the strength of the alliance and intervene if it is threatened. For example, if you misunderstand your patient and inadvertently offend them, apologizing may be helpful. In the face of disagreement between the patient and therapist, reorienting back to shared goals reinforces common ground.

Reduce anxiety and negative affect. In contrast to the caricature of the stiff psychoanalyst, the supportive therapist adopts an engaged conversational style to help the patient feel relaxed and to diminish the power differential between therapist and patient. If the patient appears uncomfortable with silence, maintaining the flow of conversation may reduce discomfort.1 Minimize your patient’s discomfort by approaching uncomfortable topics in manageable portions. Seek permission before introducing a subject that induces anxiety. Explain the reasoning behind approaching such topics.3 Reassurance and encouragement can further reduce anxiety.4 When not incongruous to the discussion, appropriate use of warm affect (eg, a smile) or even humor can elicit positive affect.

Increase awareness. Use psychoeducation and psychological interpretation (whether cognitive-behavioral or psychodynamic) to expand your patient’s awareness and help them understand their social contacts’ point of view. Clarification, gentle confrontation, and interpretation can make patients aware of biopsychosocial precipitants of distress.4

Strengthen coping mechanisms. Reinforce adaptive defense mechanisms, such as mature humor or suppression. Educating patients on practical organizational skills, problem-solving, relaxation techniques, and other relevant skills, can help them cope more effectively. Give advice only in limited circumstances, and when doing so, back up your advice with a rationale derived from your professional expertise. Because it is important for patients to realize that their life choices are their own, usually it is best to help the patient understand how they might come to their own decisions rather than to prescribe life choices in the form of advice.

Enhance self-esteem. Many patients in distress suffer from low self-esteem.5,6 Active encouragement and honest praise can nurture your patient’s ability to correct a distorted self-image and challenge self-reproach. Praise should not be false but reality-based. Praise can address preexisting strengths, highlight the patient’s willingness to express challenging material, or provide reinforcement on progress made toward treatment goals.

Supportive psychotherapy is a common type of therapy that often is used in combination with other modalities. By focusing on improving symptoms and accepting the patient’s limitations, it is particularly helpful for individuals who might have difficulty engaging in insight-oriented psychotherapies, such as those struggling with external stressors, including exposure to trauma, bereavement, physical disabilities, or socioeconomic challenges. Personal limitations, including severe personality disorder or intellectual disabilities, might also limit a patient’s ability to self-reflect on subconscious issues, which can lead to choosing a supportive modality.

While being supportive in the vernacular sense can be helpful, formal supportive psychotherapy employs well-defined goals and techniques.1 A therapist can facilitate progress by explicitly referring to these goals and techniques. The acronym ARISE can help therapists and other clinicians to use and appraise therapeutic progress toward these goals.

Alliance-building. The therapeutic alliance is an important predictor of the success of psychotherapy.2 Warmly encourage positive transference toward the therapist. The patient’s appreciation of the therapist’s empathic interactions can further the alliance. Paraphrasing the patient’s words can demonstrate and enhance empathy. Doing so allows clarification of the patient’s thoughts and helps the patient feel understood. Formulate and partner around shared therapeutic goals. Monitor the strength of the alliance and intervene if it is threatened. For example, if you misunderstand your patient and inadvertently offend them, apologizing may be helpful. In the face of disagreement between the patient and therapist, reorienting back to shared goals reinforces common ground.

Reduce anxiety and negative affect. In contrast to the caricature of the stiff psychoanalyst, the supportive therapist adopts an engaged conversational style to help the patient feel relaxed and to diminish the power differential between therapist and patient. If the patient appears uncomfortable with silence, maintaining the flow of conversation may reduce discomfort.1 Minimize your patient’s discomfort by approaching uncomfortable topics in manageable portions. Seek permission before introducing a subject that induces anxiety. Explain the reasoning behind approaching such topics.3 Reassurance and encouragement can further reduce anxiety.4 When not incongruous to the discussion, appropriate use of warm affect (eg, a smile) or even humor can elicit positive affect.

Increase awareness. Use psychoeducation and psychological interpretation (whether cognitive-behavioral or psychodynamic) to expand your patient’s awareness and help them understand their social contacts’ point of view. Clarification, gentle confrontation, and interpretation can make patients aware of biopsychosocial precipitants of distress.4

Strengthen coping mechanisms. Reinforce adaptive defense mechanisms, such as mature humor or suppression. Educating patients on practical organizational skills, problem-solving, relaxation techniques, and other relevant skills, can help them cope more effectively. Give advice only in limited circumstances, and when doing so, back up your advice with a rationale derived from your professional expertise. Because it is important for patients to realize that their life choices are their own, usually it is best to help the patient understand how they might come to their own decisions rather than to prescribe life choices in the form of advice.

Enhance self-esteem. Many patients in distress suffer from low self-esteem.5,6 Active encouragement and honest praise can nurture your patient’s ability to correct a distorted self-image and challenge self-reproach. Praise should not be false but reality-based. Praise can address preexisting strengths, highlight the patient’s willingness to express challenging material, or provide reinforcement on progress made toward treatment goals.

1. Rothe, EM. Supportive psychotherapy in everyday clinical practice: it’s like riding a bicycle. Psychiatric Times. Published May 24, 2017. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/supportive-psychotherapy-everyday-clinical-practice-its-riding-bicycle

2. Flückiger C, Del Re AC, Wampold BE, et al. The alliance in adult psychotherapy: a meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2018;55(4):316-340.

3. Pine F. The interpretive moment. Variations on classical themes. Bull Menninger Clin. 1984;48(1), 54-71.

4. Grover S, Avasthi A, Jagiwala M. Clinical practice guidelines for practice of supportive psychotherapy. Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62(Suppl 2):S173-S182.

5. Leary MR, Schreindorfer LS, Haupt AL. The role of low self-esteem in emotional and behavioral problems: why is low self-esteem dysfunctional? J Soc Clin Psychol. 1995;14(3):297-314.

6. Zahn R, Lythe KE, Gethin JA, et al. The role of self-blame and worthlessness in the psychopathology of major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2015;186:337-341.

1. Rothe, EM. Supportive psychotherapy in everyday clinical practice: it’s like riding a bicycle. Psychiatric Times. Published May 24, 2017. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/supportive-psychotherapy-everyday-clinical-practice-its-riding-bicycle

2. Flückiger C, Del Re AC, Wampold BE, et al. The alliance in adult psychotherapy: a meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2018;55(4):316-340.

3. Pine F. The interpretive moment. Variations on classical themes. Bull Menninger Clin. 1984;48(1), 54-71.

4. Grover S, Avasthi A, Jagiwala M. Clinical practice guidelines for practice of supportive psychotherapy. Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62(Suppl 2):S173-S182.

5. Leary MR, Schreindorfer LS, Haupt AL. The role of low self-esteem in emotional and behavioral problems: why is low self-esteem dysfunctional? J Soc Clin Psychol. 1995;14(3):297-314.

6. Zahn R, Lythe KE, Gethin JA, et al. The role of self-blame and worthlessness in the psychopathology of major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2015;186:337-341.

Delirious after undergoing workup for stroke

CASE Altered mental status after stroke workup

Ms. L, age 91, is admitted to the hospital for a neurologic evaluation of a recent episode of left-sided weakness that occurred 1 week ago. This left-sided weakness resolved without intervention within 2 hours while at home. This presentation is typical of a transient ischemic attack (TIA). She has a history of hypertension, bradycardia, and pacemaker implantation. On initial evaluation, her memory is intact, and she is able to walk normally. Her score on the St. Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) exam is 25, which suggests normal cognitive functioning for her academic background. A CT scan of the head reveals a subacute stroke of the right posterior limb of the internal capsule consistent with recent TIA.

Ms. L is admitted for a routine stroke workup and prepares to undergo a CT angiogram (CTA) with the use of the iodinated agent iopamidol (100 mL, 76%) to evaluate patency of cerebral vessels. Her baseline blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels are within normal limits.

A day after undergoing CTA, Ms. L starts mumbling to herself, has unpredictable mood outbursts, and is not oriented to time, place, or person.

[polldaddy:10199351]

The authors’ observations

Due to her acute altered mental status (AMS), Ms. L underwent an emergent CT scan of the head to rule out any acute intracranial hemorrhages or thromboembolic events. The results of this test were negative. Urinalysis, BUN, creatinine, basic chemistry, and complete blood count panels were unrevealing. On a repeat SLUMS exam, Ms. L scored 9, indicating cognitive impairment.

Ms. L also underwent a comprehensive metabolic profile, which excluded any electrolyte abnormalities, or any hepatic or renal causes of AMS. There was no sign of dehydration, acidosis, hypoglycemia, hypoxemia, hypotension, or bradycardia/tachycardia. A urinalysis, chest X-ray, complete blood count, and 2 blood cultures conducted 24 hours apart did not reveal any signs of infection. There were no recent changes in her medications and she was not taking any sleep medications or other psychiatric medications that might precipitate a withdrawal syndrome.

There have been multiple reports of contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN), which may be evidenced by high BUN-to-creatinine ratios and could cause AMS in geriatric patients. However, CIN was ruled out as a potential cause in our patient because her BUN-to-creatinine was unremarkable.

Continue to: Routine EEG was clinically...

Routine EEG was clinically inconclusive. Diffusion-weighted MRI may have been helpful to identify ischemic strokes that a CT scan of the head might miss,1 but we were unable to conduct this test because Ms. L had a pacemaker. Barber et al2 suggested that in the setting of acute stroke, the use of MRI may not have an added advantage over the CT scan of the head.

[polldaddy:10199352]

TREATMENT Rapid improvement with supportive therapy

Intravenous fluids are administered as supportive therapy to Ms. L for suspected contrast-induced encephalopathy (CIE). The next day, Ms. L experiences a notable improvement in cognition, beyond that attributed to IV hydration. By 3 days post-contrast injection, her SLUMS score increases to 15. By 72 hours after contrast administration, Ms. L’s cognition returns to baseline. She is monitored for 24 hours after returning to baseline cognitive functioning. After observing her to be in no physical or medical distress and at baseline functioning, she is discharged home under the care of her son with outpatient follow-up and rehab services.

The authors’ observations

For Ms. L, the differential diagnosis included post-ictal phenomenon, new-onset ischemic or hemorrhagic changes, hyperperfusion syndrome, and CIE.

Seizures were ruled out because EEG was inconclusive, and Ms. L did not have the clinical features one would expect in an ictal episode. Transient ischemic attack is, by definition, an ischemic event with clinical return to baseline within 24 hours. Although a CT scan of the head may not be the most sensitive way to detect early ischemic changes and small ischemic zones, the self-limiting course and complete resolution of Ms. L’s symptoms with return to baseline is indicative of a more benign pathology, such as CIE. New hemorrhagic conversions have a dramatic presentation on radiologic studies. Historically, CIE presentations on imaging have been closely associated with the hyperattentuation seen in subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). The absence of typical radiologic and clinical findings in our case ruled out SAH.

Continue to: Typical CT scan findings in CIE include...

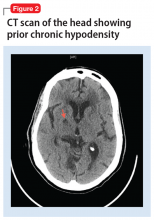

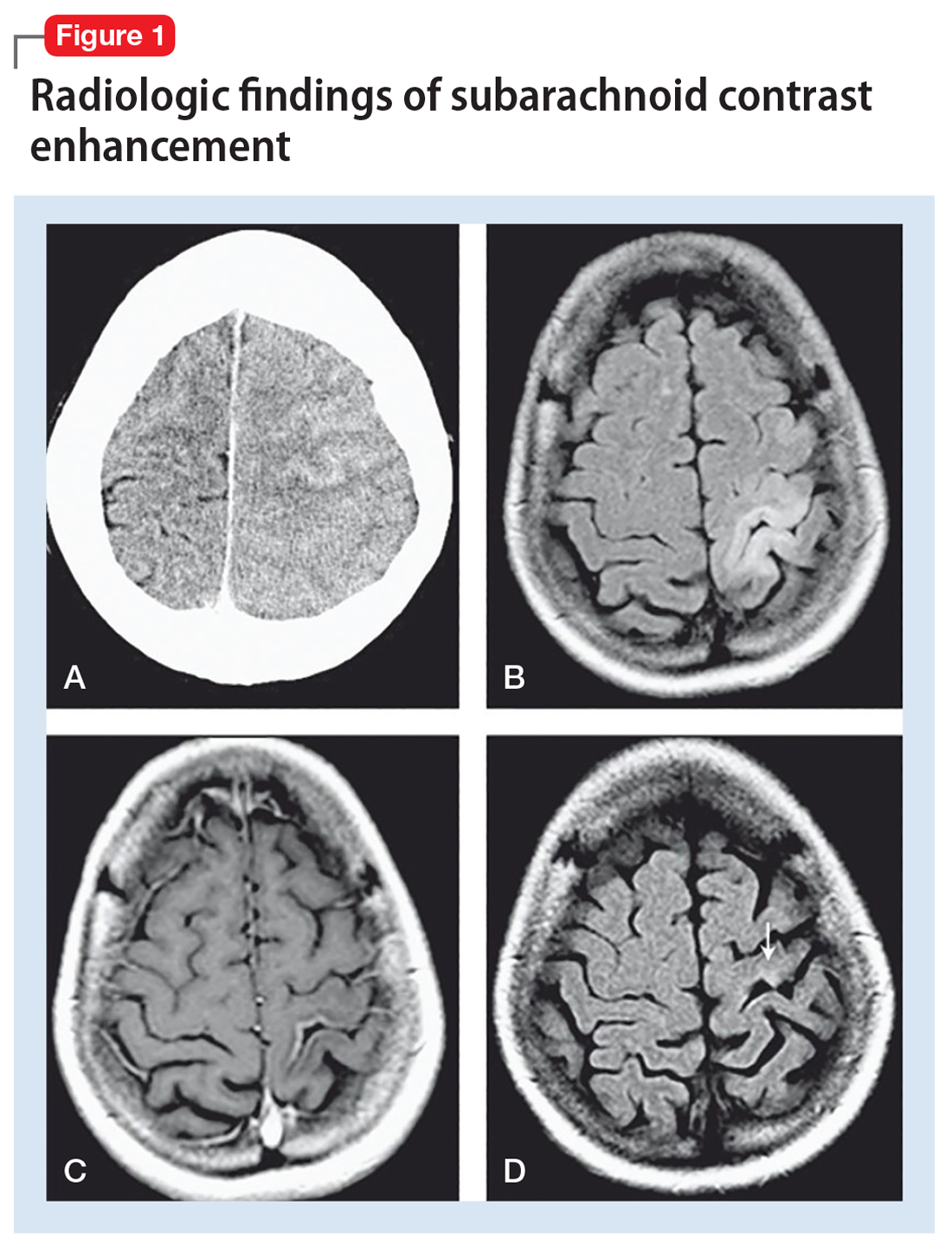

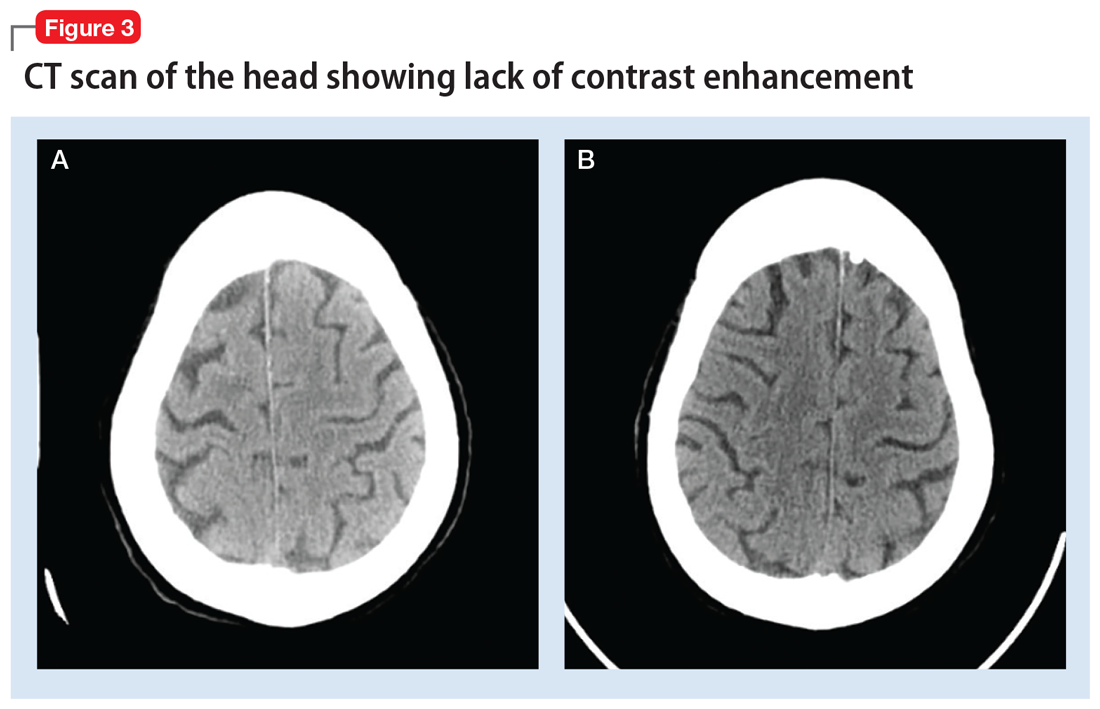

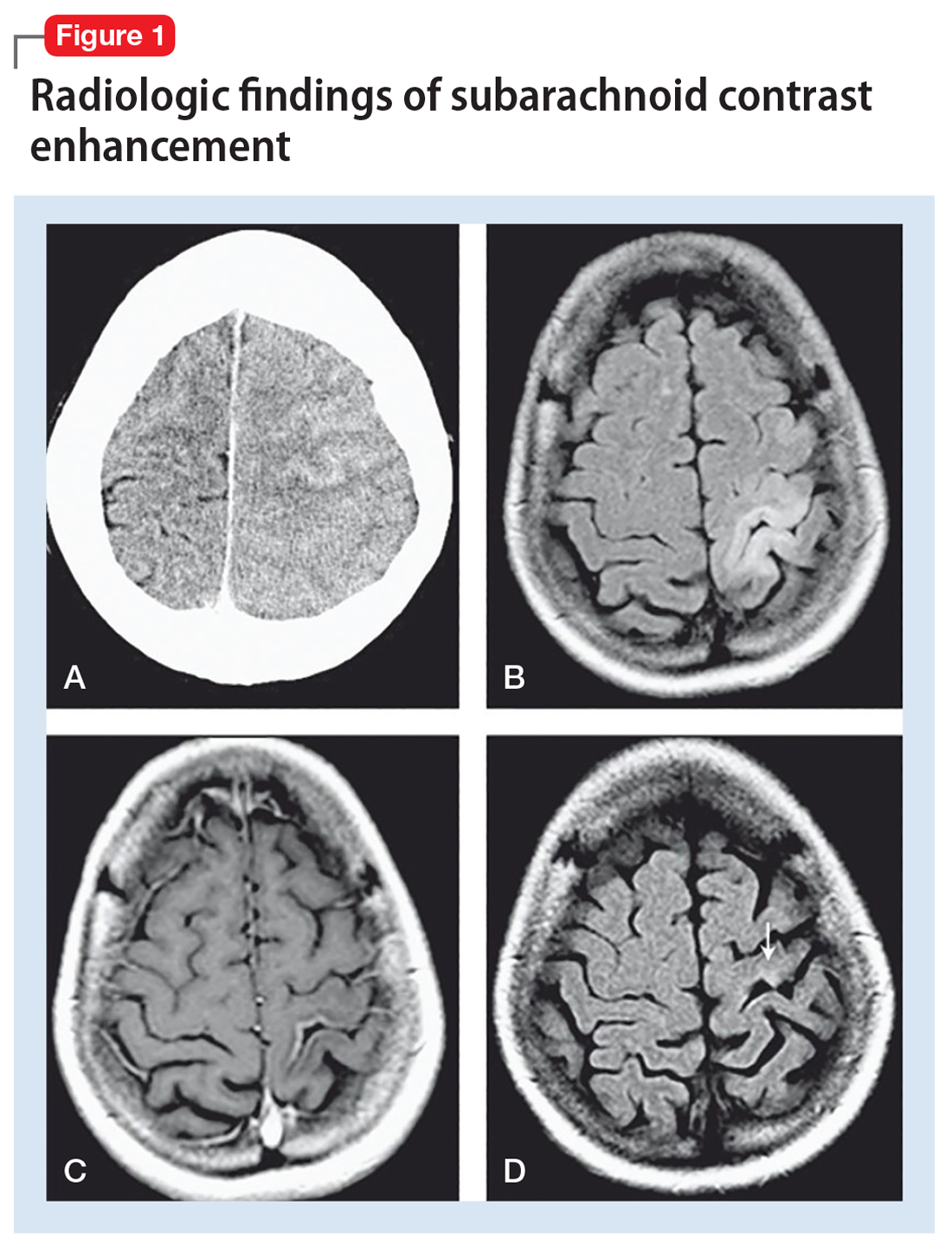

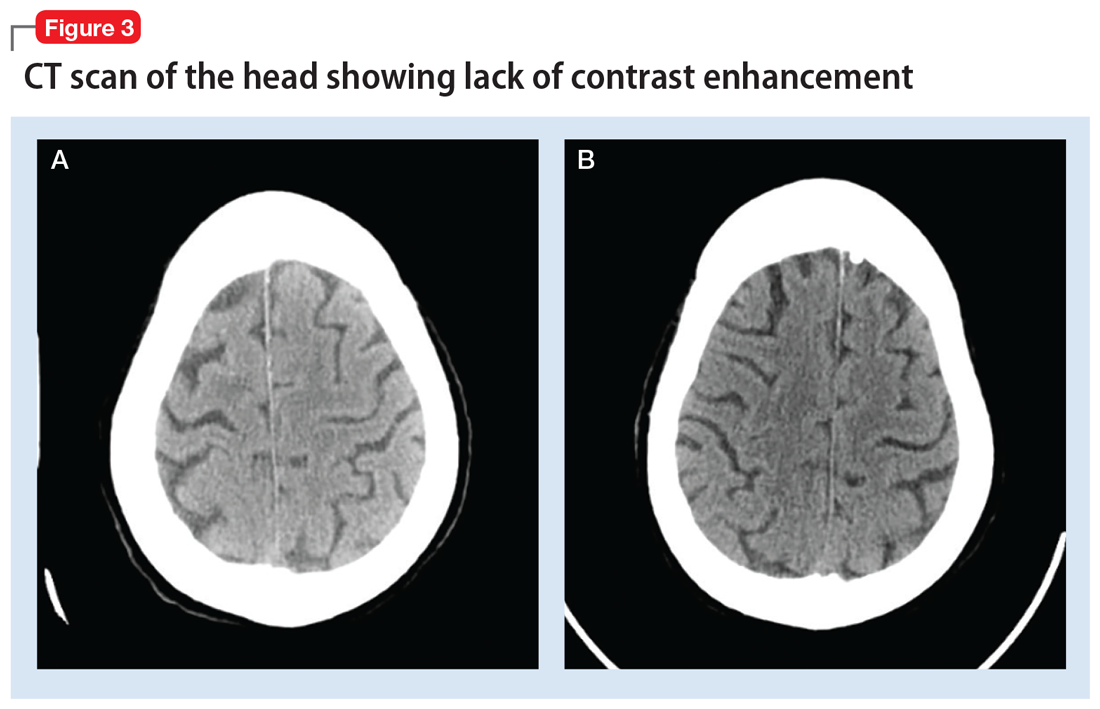

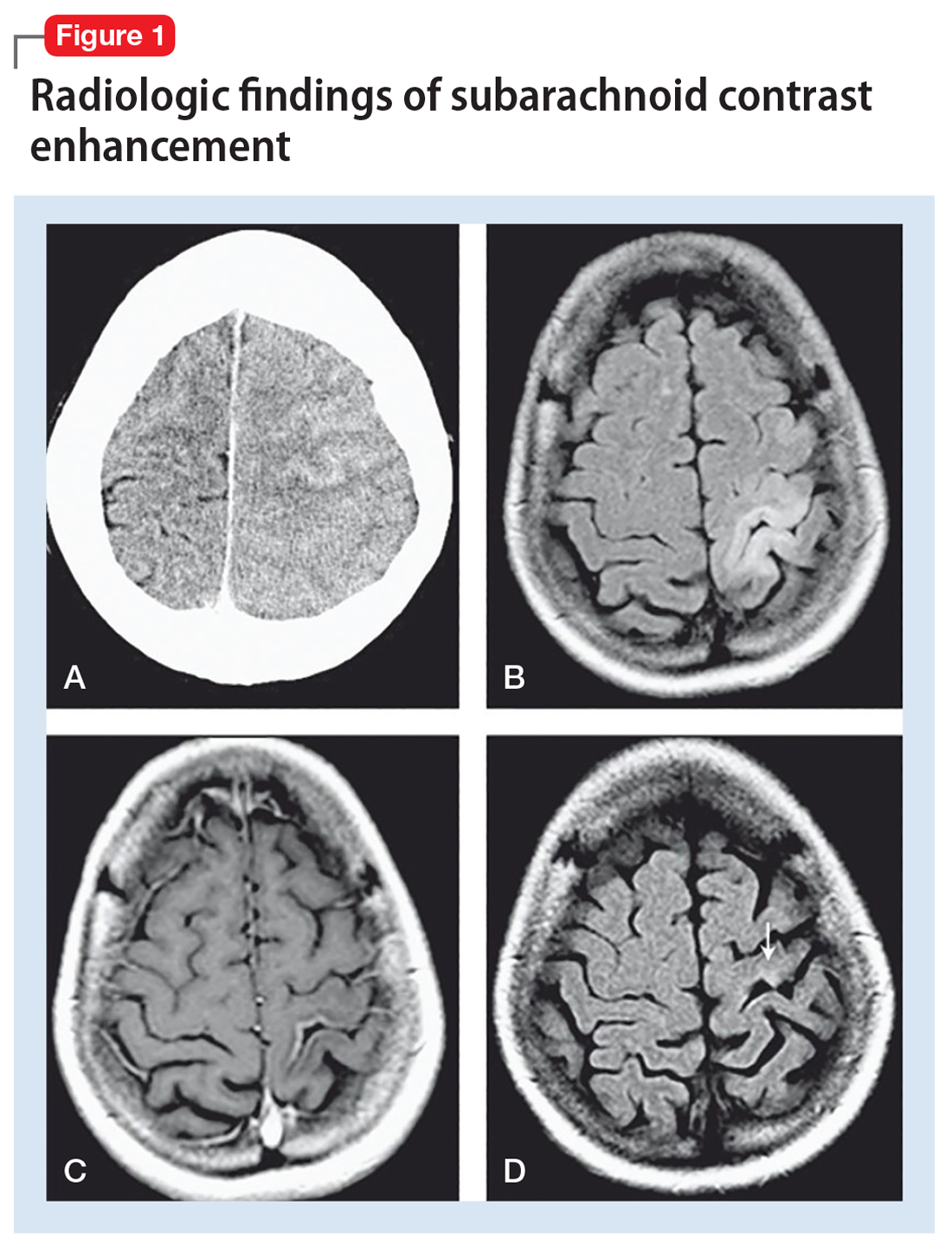

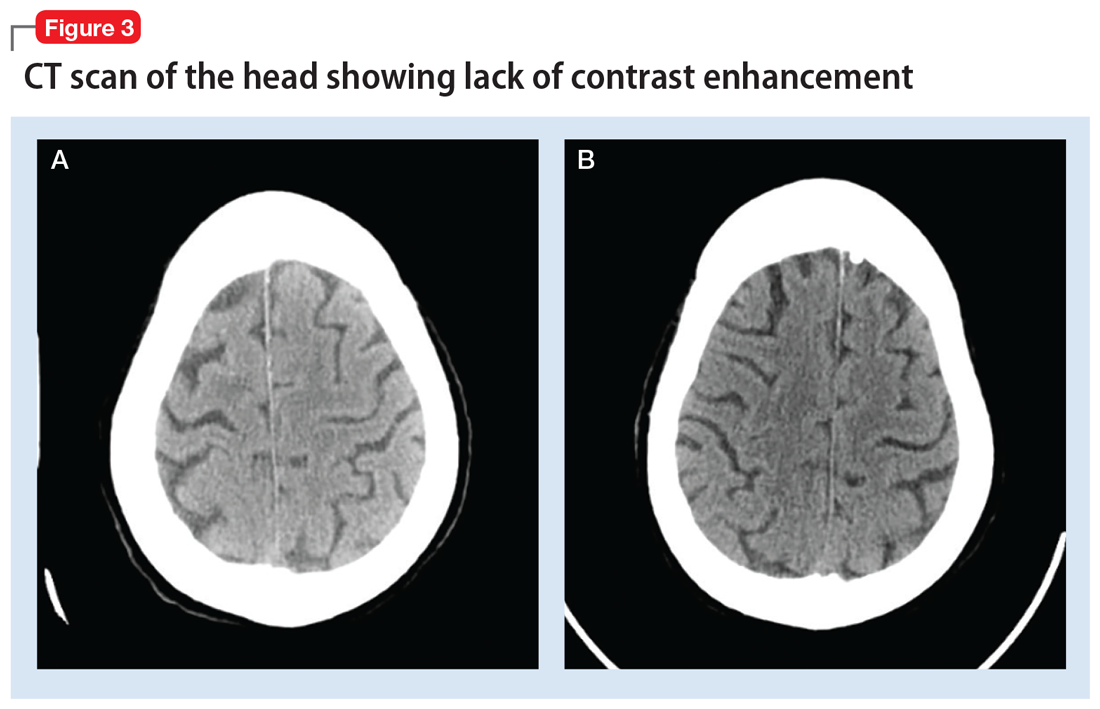

Typical CT scan findings in CIE include abnormal cortical contrast enhancement and edema, subarachnoid contrast enhancement, and striatal contrast enhancement (Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3). Since the first clinical description, reports of 39 CT-/MRI-confirmed cases of CIE have been published in English language medical literature, with documented clinical follow-up3 and a median recovery time of 2.5 days. In a case report by Ito et al,4 there were no supportive radiographic findings. Ours is the second documented case that showed no radiologic signs of CIE. With a paucity of other etiologic evidence, negative lab tests for other causes of delirium, and the rapid resolution of Ms. L’s AMS after providing IV fluids as supportive treatment, a temporal correlation can be deduced, which implicates iodine-based contrast as the inciting factor.

Iodine-based contrast agents have been used since the 1920s. Today, >75 million procedures requiring iodine dyes are performed annually worldwide.5 This level of routine iodine contrast usage compels a mention of risk factors and complications from using such dyes. As a general rule, contrast agent reactions can be categorized as immediate (<1 day) or delayed (1 to 7 days after contrast administration). Immediate reactions are immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated anaphylactic reactions. Delayed reactions involve a T-cell mediated response that ranges from pruritus and urticaria (approximately 70%) to cardiac complications such as cardiovascular shock, arrhythmia, arrest, and Kounis syndrome. Other less prevalent complications include hypotension, bronchospasm, and CIN. Patients with the following factors may be at higher risk for contrast-induced reactions:

- asthma

- cardiac arrhythmias

- central myasthenia gravis

- >70 years of age

- pheochromocytoma

- sickle cell anemia

- hyperthyroidism

- dehydration

- hypotension.

Although some older literature reported correlations between seafood and shellfish allergies and iodine contrast reactions, more recent reports suggest there may not be a direct correlation, or any correlation at all.5,6

Iodinated CIE is a rare complication of contrast angiography. It was first reported in 1970 as transient cortical blindness after coronary angiography.7 Clinical manifestations include encephalopathy evidenced by AMS, affected orientation, and acute psychotic changes, including paranoia and hallucinations, seizures, cortical blindness, and focal neurologic deficits. Neuroimaging has been pivotal in confirming the diagnosis and in excluding thromboembolic and hemorrhagic complications of angiography.8

Encephalopathy has been documented after administration of

Continue to: Regardless of the mechanism...

Regardless of the mechanism, all the above-mentioned studies note a reversal of radiologic and neurologic findings without any deficits within 48 to 72 hours (median recovery time of 2.5 days).3 All reported cases of CIE, including ours, were found to be completely reversible without any neurologic or radiologic deficits after resolution (48 to 72 hours post-contrast administration).

Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for CIE in patients with recent iodine-based contrast exposure. From a practical standpoint, such a mechanism could be easily missed because while use of a single-administration contrast agent may appear in procedure notes or medication administration records, it might not necessarily appear in documentation of currently administered medications. Also, such cases might not always present with unique radiologic findings, as illustrated by Ms. L’s case.

Bottom Line

Have a high index of suspicion for contrast-induced encephalopathy, especially in geriatric patients, even in the absence of radiologic findings. A full delirium/dementia workup is warranted to rule out other life-threatening causes of altered mental status. Timely recognition could enable implementation of medicationsparing approaches to the disorder, such as IV fluids and frequent reorientation.

Related Resources

- Donepudi B, Trottier S. A seizure and hemiplegia following contrast exposure: Understanding contrast-induced encephalopathy. Case Rep Med. 2018;2018:9278526. doi:10.1155/2018/9278526.

- Hamra M, Bakhit Y, Khan M, et al. Case report and literature review on contrast-induced encephalopathy. Future Cardiol. 2017;13(4):331-335.

Drug Brand Names

Iohexol • Omnipaque

Iopamidol • Isovue-370

Iopromide • Ultravist

Ioxilan • Oxilan

1. Moreau F, Asdaghi N, Modi J, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging versus computed tomography in transient ischemic attack and minor stroke: the more you see the more you know. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra. 2013;3(1):130-136.

2. Barber PA, Hill MD, Eliasziw M, et al. Imaging of the brain in acute ischaemic stroke: comparison of computed tomography and magnetic resonance diffusion-weighted imaging. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(11):1528-1533.

3. Leong S, Fanning NF. Persistent neurological deficit from iodinated contrast encephalopathy following intracranial aneurysm coiling: a case report and review of the literature. Interv Neuroradiol. 2012;18(1):33-41.

4. Ito N, Nishio R, Ozuki T, et al. A state of delirium (confusion) following cerebral angiography with ioxilan: a case report. Nihon Igaku Hoshasen Gakkai Zasshi. 2002; 62(7):370-371.

5. Bottinor W, Polkampally P, Jovin I. Adverse reactions to iodinated contrast media. Int J Angiol. 2013;22:149-154.

6. Cohan R. AHRQ Patient Safety Network Reaction to Dye. US Department of Health and Human Services Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/webmm/case/75/reaction-to-dye. Published September 2004. Accessed March 5, 2017.

7. Fischer-Williams M, Gottschalk PG, Browell JN. Transient cortical blindness: an unusual complication of coronary angiography. Neurology. 1970;20(4):353-355.

8. Lantos G. Cortical blindness due to osmotic disruption of the blood-brain barrier by angiographic contrast material: CT and MRI studies. Neurology. 1989;39(4):567-571.

9. Kocabay G, Karabay CY. Iopromide-induced encephalopathy following coronary angioplasty. Perfusion. 2011;26:67-70.

10. Dangas G, Monsein LH, Laureno R, et al. Transient contrast encephalopathy after carotid artery stenting. Journal of Endovascular Therapy. 2001;8:111-113.

11. Sawaya RA, Hammoud R, Arnaout SJ, et al. Contrast induced encephalopathy following coronary angioplasty with iohexol. Southern Medical Journal. 2007;100(10):1054-1055.

CASE Altered mental status after stroke workup

Ms. L, age 91, is admitted to the hospital for a neurologic evaluation of a recent episode of left-sided weakness that occurred 1 week ago. This left-sided weakness resolved without intervention within 2 hours while at home. This presentation is typical of a transient ischemic attack (TIA). She has a history of hypertension, bradycardia, and pacemaker implantation. On initial evaluation, her memory is intact, and she is able to walk normally. Her score on the St. Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) exam is 25, which suggests normal cognitive functioning for her academic background. A CT scan of the head reveals a subacute stroke of the right posterior limb of the internal capsule consistent with recent TIA.

Ms. L is admitted for a routine stroke workup and prepares to undergo a CT angiogram (CTA) with the use of the iodinated agent iopamidol (100 mL, 76%) to evaluate patency of cerebral vessels. Her baseline blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels are within normal limits.

A day after undergoing CTA, Ms. L starts mumbling to herself, has unpredictable mood outbursts, and is not oriented to time, place, or person.

[polldaddy:10199351]

The authors’ observations

Due to her acute altered mental status (AMS), Ms. L underwent an emergent CT scan of the head to rule out any acute intracranial hemorrhages or thromboembolic events. The results of this test were negative. Urinalysis, BUN, creatinine, basic chemistry, and complete blood count panels were unrevealing. On a repeat SLUMS exam, Ms. L scored 9, indicating cognitive impairment.

Ms. L also underwent a comprehensive metabolic profile, which excluded any electrolyte abnormalities, or any hepatic or renal causes of AMS. There was no sign of dehydration, acidosis, hypoglycemia, hypoxemia, hypotension, or bradycardia/tachycardia. A urinalysis, chest X-ray, complete blood count, and 2 blood cultures conducted 24 hours apart did not reveal any signs of infection. There were no recent changes in her medications and she was not taking any sleep medications or other psychiatric medications that might precipitate a withdrawal syndrome.

There have been multiple reports of contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN), which may be evidenced by high BUN-to-creatinine ratios and could cause AMS in geriatric patients. However, CIN was ruled out as a potential cause in our patient because her BUN-to-creatinine was unremarkable.

Continue to: Routine EEG was clinically...

Routine EEG was clinically inconclusive. Diffusion-weighted MRI may have been helpful to identify ischemic strokes that a CT scan of the head might miss,1 but we were unable to conduct this test because Ms. L had a pacemaker. Barber et al2 suggested that in the setting of acute stroke, the use of MRI may not have an added advantage over the CT scan of the head.

[polldaddy:10199352]

TREATMENT Rapid improvement with supportive therapy

Intravenous fluids are administered as supportive therapy to Ms. L for suspected contrast-induced encephalopathy (CIE). The next day, Ms. L experiences a notable improvement in cognition, beyond that attributed to IV hydration. By 3 days post-contrast injection, her SLUMS score increases to 15. By 72 hours after contrast administration, Ms. L’s cognition returns to baseline. She is monitored for 24 hours after returning to baseline cognitive functioning. After observing her to be in no physical or medical distress and at baseline functioning, she is discharged home under the care of her son with outpatient follow-up and rehab services.

The authors’ observations

For Ms. L, the differential diagnosis included post-ictal phenomenon, new-onset ischemic or hemorrhagic changes, hyperperfusion syndrome, and CIE.

Seizures were ruled out because EEG was inconclusive, and Ms. L did not have the clinical features one would expect in an ictal episode. Transient ischemic attack is, by definition, an ischemic event with clinical return to baseline within 24 hours. Although a CT scan of the head may not be the most sensitive way to detect early ischemic changes and small ischemic zones, the self-limiting course and complete resolution of Ms. L’s symptoms with return to baseline is indicative of a more benign pathology, such as CIE. New hemorrhagic conversions have a dramatic presentation on radiologic studies. Historically, CIE presentations on imaging have been closely associated with the hyperattentuation seen in subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). The absence of typical radiologic and clinical findings in our case ruled out SAH.

Continue to: Typical CT scan findings in CIE include...

Typical CT scan findings in CIE include abnormal cortical contrast enhancement and edema, subarachnoid contrast enhancement, and striatal contrast enhancement (Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3). Since the first clinical description, reports of 39 CT-/MRI-confirmed cases of CIE have been published in English language medical literature, with documented clinical follow-up3 and a median recovery time of 2.5 days. In a case report by Ito et al,4 there were no supportive radiographic findings. Ours is the second documented case that showed no radiologic signs of CIE. With a paucity of other etiologic evidence, negative lab tests for other causes of delirium, and the rapid resolution of Ms. L’s AMS after providing IV fluids as supportive treatment, a temporal correlation can be deduced, which implicates iodine-based contrast as the inciting factor.

Iodine-based contrast agents have been used since the 1920s. Today, >75 million procedures requiring iodine dyes are performed annually worldwide.5 This level of routine iodine contrast usage compels a mention of risk factors and complications from using such dyes. As a general rule, contrast agent reactions can be categorized as immediate (<1 day) or delayed (1 to 7 days after contrast administration). Immediate reactions are immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated anaphylactic reactions. Delayed reactions involve a T-cell mediated response that ranges from pruritus and urticaria (approximately 70%) to cardiac complications such as cardiovascular shock, arrhythmia, arrest, and Kounis syndrome. Other less prevalent complications include hypotension, bronchospasm, and CIN. Patients with the following factors may be at higher risk for contrast-induced reactions:

- asthma

- cardiac arrhythmias

- central myasthenia gravis

- >70 years of age

- pheochromocytoma

- sickle cell anemia

- hyperthyroidism

- dehydration

- hypotension.

Although some older literature reported correlations between seafood and shellfish allergies and iodine contrast reactions, more recent reports suggest there may not be a direct correlation, or any correlation at all.5,6

Iodinated CIE is a rare complication of contrast angiography. It was first reported in 1970 as transient cortical blindness after coronary angiography.7 Clinical manifestations include encephalopathy evidenced by AMS, affected orientation, and acute psychotic changes, including paranoia and hallucinations, seizures, cortical blindness, and focal neurologic deficits. Neuroimaging has been pivotal in confirming the diagnosis and in excluding thromboembolic and hemorrhagic complications of angiography.8

Encephalopathy has been documented after administration of

Continue to: Regardless of the mechanism...

Regardless of the mechanism, all the above-mentioned studies note a reversal of radiologic and neurologic findings without any deficits within 48 to 72 hours (median recovery time of 2.5 days).3 All reported cases of CIE, including ours, were found to be completely reversible without any neurologic or radiologic deficits after resolution (48 to 72 hours post-contrast administration).

Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for CIE in patients with recent iodine-based contrast exposure. From a practical standpoint, such a mechanism could be easily missed because while use of a single-administration contrast agent may appear in procedure notes or medication administration records, it might not necessarily appear in documentation of currently administered medications. Also, such cases might not always present with unique radiologic findings, as illustrated by Ms. L’s case.

Bottom Line

Have a high index of suspicion for contrast-induced encephalopathy, especially in geriatric patients, even in the absence of radiologic findings. A full delirium/dementia workup is warranted to rule out other life-threatening causes of altered mental status. Timely recognition could enable implementation of medicationsparing approaches to the disorder, such as IV fluids and frequent reorientation.

Related Resources

- Donepudi B, Trottier S. A seizure and hemiplegia following contrast exposure: Understanding contrast-induced encephalopathy. Case Rep Med. 2018;2018:9278526. doi:10.1155/2018/9278526.

- Hamra M, Bakhit Y, Khan M, et al. Case report and literature review on contrast-induced encephalopathy. Future Cardiol. 2017;13(4):331-335.

Drug Brand Names

Iohexol • Omnipaque

Iopamidol • Isovue-370

Iopromide • Ultravist

Ioxilan • Oxilan

CASE Altered mental status after stroke workup

Ms. L, age 91, is admitted to the hospital for a neurologic evaluation of a recent episode of left-sided weakness that occurred 1 week ago. This left-sided weakness resolved without intervention within 2 hours while at home. This presentation is typical of a transient ischemic attack (TIA). She has a history of hypertension, bradycardia, and pacemaker implantation. On initial evaluation, her memory is intact, and she is able to walk normally. Her score on the St. Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) exam is 25, which suggests normal cognitive functioning for her academic background. A CT scan of the head reveals a subacute stroke of the right posterior limb of the internal capsule consistent with recent TIA.

Ms. L is admitted for a routine stroke workup and prepares to undergo a CT angiogram (CTA) with the use of the iodinated agent iopamidol (100 mL, 76%) to evaluate patency of cerebral vessels. Her baseline blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels are within normal limits.

A day after undergoing CTA, Ms. L starts mumbling to herself, has unpredictable mood outbursts, and is not oriented to time, place, or person.

[polldaddy:10199351]

The authors’ observations

Due to her acute altered mental status (AMS), Ms. L underwent an emergent CT scan of the head to rule out any acute intracranial hemorrhages or thromboembolic events. The results of this test were negative. Urinalysis, BUN, creatinine, basic chemistry, and complete blood count panels were unrevealing. On a repeat SLUMS exam, Ms. L scored 9, indicating cognitive impairment.

Ms. L also underwent a comprehensive metabolic profile, which excluded any electrolyte abnormalities, or any hepatic or renal causes of AMS. There was no sign of dehydration, acidosis, hypoglycemia, hypoxemia, hypotension, or bradycardia/tachycardia. A urinalysis, chest X-ray, complete blood count, and 2 blood cultures conducted 24 hours apart did not reveal any signs of infection. There were no recent changes in her medications and she was not taking any sleep medications or other psychiatric medications that might precipitate a withdrawal syndrome.

There have been multiple reports of contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN), which may be evidenced by high BUN-to-creatinine ratios and could cause AMS in geriatric patients. However, CIN was ruled out as a potential cause in our patient because her BUN-to-creatinine was unremarkable.

Continue to: Routine EEG was clinically...

Routine EEG was clinically inconclusive. Diffusion-weighted MRI may have been helpful to identify ischemic strokes that a CT scan of the head might miss,1 but we were unable to conduct this test because Ms. L had a pacemaker. Barber et al2 suggested that in the setting of acute stroke, the use of MRI may not have an added advantage over the CT scan of the head.

[polldaddy:10199352]

TREATMENT Rapid improvement with supportive therapy

Intravenous fluids are administered as supportive therapy to Ms. L for suspected contrast-induced encephalopathy (CIE). The next day, Ms. L experiences a notable improvement in cognition, beyond that attributed to IV hydration. By 3 days post-contrast injection, her SLUMS score increases to 15. By 72 hours after contrast administration, Ms. L’s cognition returns to baseline. She is monitored for 24 hours after returning to baseline cognitive functioning. After observing her to be in no physical or medical distress and at baseline functioning, she is discharged home under the care of her son with outpatient follow-up and rehab services.

The authors’ observations

For Ms. L, the differential diagnosis included post-ictal phenomenon, new-onset ischemic or hemorrhagic changes, hyperperfusion syndrome, and CIE.

Seizures were ruled out because EEG was inconclusive, and Ms. L did not have the clinical features one would expect in an ictal episode. Transient ischemic attack is, by definition, an ischemic event with clinical return to baseline within 24 hours. Although a CT scan of the head may not be the most sensitive way to detect early ischemic changes and small ischemic zones, the self-limiting course and complete resolution of Ms. L’s symptoms with return to baseline is indicative of a more benign pathology, such as CIE. New hemorrhagic conversions have a dramatic presentation on radiologic studies. Historically, CIE presentations on imaging have been closely associated with the hyperattentuation seen in subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). The absence of typical radiologic and clinical findings in our case ruled out SAH.

Continue to: Typical CT scan findings in CIE include...

Typical CT scan findings in CIE include abnormal cortical contrast enhancement and edema, subarachnoid contrast enhancement, and striatal contrast enhancement (Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3). Since the first clinical description, reports of 39 CT-/MRI-confirmed cases of CIE have been published in English language medical literature, with documented clinical follow-up3 and a median recovery time of 2.5 days. In a case report by Ito et al,4 there were no supportive radiographic findings. Ours is the second documented case that showed no radiologic signs of CIE. With a paucity of other etiologic evidence, negative lab tests for other causes of delirium, and the rapid resolution of Ms. L’s AMS after providing IV fluids as supportive treatment, a temporal correlation can be deduced, which implicates iodine-based contrast as the inciting factor.

Iodine-based contrast agents have been used since the 1920s. Today, >75 million procedures requiring iodine dyes are performed annually worldwide.5 This level of routine iodine contrast usage compels a mention of risk factors and complications from using such dyes. As a general rule, contrast agent reactions can be categorized as immediate (<1 day) or delayed (1 to 7 days after contrast administration). Immediate reactions are immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated anaphylactic reactions. Delayed reactions involve a T-cell mediated response that ranges from pruritus and urticaria (approximately 70%) to cardiac complications such as cardiovascular shock, arrhythmia, arrest, and Kounis syndrome. Other less prevalent complications include hypotension, bronchospasm, and CIN. Patients with the following factors may be at higher risk for contrast-induced reactions:

- asthma

- cardiac arrhythmias

- central myasthenia gravis

- >70 years of age

- pheochromocytoma

- sickle cell anemia

- hyperthyroidism

- dehydration

- hypotension.

Although some older literature reported correlations between seafood and shellfish allergies and iodine contrast reactions, more recent reports suggest there may not be a direct correlation, or any correlation at all.5,6

Iodinated CIE is a rare complication of contrast angiography. It was first reported in 1970 as transient cortical blindness after coronary angiography.7 Clinical manifestations include encephalopathy evidenced by AMS, affected orientation, and acute psychotic changes, including paranoia and hallucinations, seizures, cortical blindness, and focal neurologic deficits. Neuroimaging has been pivotal in confirming the diagnosis and in excluding thromboembolic and hemorrhagic complications of angiography.8

Encephalopathy has been documented after administration of

Continue to: Regardless of the mechanism...

Regardless of the mechanism, all the above-mentioned studies note a reversal of radiologic and neurologic findings without any deficits within 48 to 72 hours (median recovery time of 2.5 days).3 All reported cases of CIE, including ours, were found to be completely reversible without any neurologic or radiologic deficits after resolution (48 to 72 hours post-contrast administration).

Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for CIE in patients with recent iodine-based contrast exposure. From a practical standpoint, such a mechanism could be easily missed because while use of a single-administration contrast agent may appear in procedure notes or medication administration records, it might not necessarily appear in documentation of currently administered medications. Also, such cases might not always present with unique radiologic findings, as illustrated by Ms. L’s case.

Bottom Line

Have a high index of suspicion for contrast-induced encephalopathy, especially in geriatric patients, even in the absence of radiologic findings. A full delirium/dementia workup is warranted to rule out other life-threatening causes of altered mental status. Timely recognition could enable implementation of medicationsparing approaches to the disorder, such as IV fluids and frequent reorientation.

Related Resources

- Donepudi B, Trottier S. A seizure and hemiplegia following contrast exposure: Understanding contrast-induced encephalopathy. Case Rep Med. 2018;2018:9278526. doi:10.1155/2018/9278526.

- Hamra M, Bakhit Y, Khan M, et al. Case report and literature review on contrast-induced encephalopathy. Future Cardiol. 2017;13(4):331-335.

Drug Brand Names

Iohexol • Omnipaque

Iopamidol • Isovue-370

Iopromide • Ultravist

Ioxilan • Oxilan

1. Moreau F, Asdaghi N, Modi J, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging versus computed tomography in transient ischemic attack and minor stroke: the more you see the more you know. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra. 2013;3(1):130-136.

2. Barber PA, Hill MD, Eliasziw M, et al. Imaging of the brain in acute ischaemic stroke: comparison of computed tomography and magnetic resonance diffusion-weighted imaging. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(11):1528-1533.

3. Leong S, Fanning NF. Persistent neurological deficit from iodinated contrast encephalopathy following intracranial aneurysm coiling: a case report and review of the literature. Interv Neuroradiol. 2012;18(1):33-41.

4. Ito N, Nishio R, Ozuki T, et al. A state of delirium (confusion) following cerebral angiography with ioxilan: a case report. Nihon Igaku Hoshasen Gakkai Zasshi. 2002; 62(7):370-371.

5. Bottinor W, Polkampally P, Jovin I. Adverse reactions to iodinated contrast media. Int J Angiol. 2013;22:149-154.

6. Cohan R. AHRQ Patient Safety Network Reaction to Dye. US Department of Health and Human Services Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/webmm/case/75/reaction-to-dye. Published September 2004. Accessed March 5, 2017.

7. Fischer-Williams M, Gottschalk PG, Browell JN. Transient cortical blindness: an unusual complication of coronary angiography. Neurology. 1970;20(4):353-355.

8. Lantos G. Cortical blindness due to osmotic disruption of the blood-brain barrier by angiographic contrast material: CT and MRI studies. Neurology. 1989;39(4):567-571.

9. Kocabay G, Karabay CY. Iopromide-induced encephalopathy following coronary angioplasty. Perfusion. 2011;26:67-70.

10. Dangas G, Monsein LH, Laureno R, et al. Transient contrast encephalopathy after carotid artery stenting. Journal of Endovascular Therapy. 2001;8:111-113.

11. Sawaya RA, Hammoud R, Arnaout SJ, et al. Contrast induced encephalopathy following coronary angioplasty with iohexol. Southern Medical Journal. 2007;100(10):1054-1055.

1. Moreau F, Asdaghi N, Modi J, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging versus computed tomography in transient ischemic attack and minor stroke: the more you see the more you know. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra. 2013;3(1):130-136.

2. Barber PA, Hill MD, Eliasziw M, et al. Imaging of the brain in acute ischaemic stroke: comparison of computed tomography and magnetic resonance diffusion-weighted imaging. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(11):1528-1533.

3. Leong S, Fanning NF. Persistent neurological deficit from iodinated contrast encephalopathy following intracranial aneurysm coiling: a case report and review of the literature. Interv Neuroradiol. 2012;18(1):33-41.

4. Ito N, Nishio R, Ozuki T, et al. A state of delirium (confusion) following cerebral angiography with ioxilan: a case report. Nihon Igaku Hoshasen Gakkai Zasshi. 2002; 62(7):370-371.

5. Bottinor W, Polkampally P, Jovin I. Adverse reactions to iodinated contrast media. Int J Angiol. 2013;22:149-154.

6. Cohan R. AHRQ Patient Safety Network Reaction to Dye. US Department of Health and Human Services Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/webmm/case/75/reaction-to-dye. Published September 2004. Accessed March 5, 2017.

7. Fischer-Williams M, Gottschalk PG, Browell JN. Transient cortical blindness: an unusual complication of coronary angiography. Neurology. 1970;20(4):353-355.

8. Lantos G. Cortical blindness due to osmotic disruption of the blood-brain barrier by angiographic contrast material: CT and MRI studies. Neurology. 1989;39(4):567-571.

9. Kocabay G, Karabay CY. Iopromide-induced encephalopathy following coronary angioplasty. Perfusion. 2011;26:67-70.

10. Dangas G, Monsein LH, Laureno R, et al. Transient contrast encephalopathy after carotid artery stenting. Journal of Endovascular Therapy. 2001;8:111-113.

11. Sawaya RA, Hammoud R, Arnaout SJ, et al. Contrast induced encephalopathy following coronary angioplasty with iohexol. Southern Medical Journal. 2007;100(10):1054-1055.

6 Brief exercises for introducing mindfulness

Mindfulness is actively being aware of one’s inner and outer environments in the present moment. Core mindfulness skills include observation, description, participation, a nonjudgmental approach, focusing on 1 thing at a time, and effectiveness.1

Psychotherapeutic interventions based on each of these skills have been developed to instill a mindful state in psychiatric patients. Evidence suggests these interventions can be helpful when treating borderline personality disorder, somatization, pain, depression, and anxiety, among other conditions.2

Elements of mindfulness can be integrated into brief interventions. The following 6 simple, practical exercises can be used to help patients develop these skills.

Observation involves noticing internal and external experiences, including thoughts and sensations, without applying words or labels. Guide your patient through the following exercise:

Focus your attention on the ground beneath your feet, feeling the pressure, temperature, and texture of this sensation. Do the same with your seat, your breath, and the sounds, sights, and smells of the room. Be aware of your thoughts and watch them come and go like fish in a fishbowl.

Description entails assigning purely descriptive words to one’s observations. To help your patient develop this skill, ask him (her) to describe the sensations he (she) observed in the previous exercise.

Participation entails immersive engagement in an activity. Ask your patient to listen to a song he has never heard before, and then play it again and dance or sing along. Instruct him to engage wholly, conscious of each step or note, without being judgmental or self-conscious. If he feels embarrassed or self-critical, tell him to observe these thoughts and emotions, put them aside, and return to the activity.

A nonjudgmental approach consists of separating out the facts and recognizing emotional responses without clinging to them. To practice this skill, ask your patient to play a song that he likes and one that he dislikes. The patient should listen to each, observing and describing the way they sound without judgment. Tell the patient that if judgmental words or phrases, such as “beautiful,” “ugly,” “I love…,” or “I hate…,” appear as thoughts, he should observe them, put them aside, and then return to nonjudgmental description and observation.

Focusing on 1 thing at a time means dedicating complete attention to a single task, activity, or thought. Give your patient a short paragraph or poem to read. Instruct

Effectiveness involves focusing on what works to attain one’s goals. For this exercise, set up a task for your patient by placing several items in a location that is neither immediately obvious nor readily accessible without an intermediate step. Instruct your patient to obtain these objects. Then guide them as follows:

What do you have to do to get them? Ask permission? Borrow a key? Recruit assistance? Determine the location? Brainstorm ways to obtain the items, and then complete the task.

1. Linehan MM. DBT skills training manual. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2015.

2. Gotink RA, Chu P, Busschbach JJ, et al. Standardised mindfulness-based interventions in healthcare: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0124344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124344.

Mindfulness is actively being aware of one’s inner and outer environments in the present moment. Core mindfulness skills include observation, description, participation, a nonjudgmental approach, focusing on 1 thing at a time, and effectiveness.1

Psychotherapeutic interventions based on each of these skills have been developed to instill a mindful state in psychiatric patients. Evidence suggests these interventions can be helpful when treating borderline personality disorder, somatization, pain, depression, and anxiety, among other conditions.2

Elements of mindfulness can be integrated into brief interventions. The following 6 simple, practical exercises can be used to help patients develop these skills.

Observation involves noticing internal and external experiences, including thoughts and sensations, without applying words or labels. Guide your patient through the following exercise:

Focus your attention on the ground beneath your feet, feeling the pressure, temperature, and texture of this sensation. Do the same with your seat, your breath, and the sounds, sights, and smells of the room. Be aware of your thoughts and watch them come and go like fish in a fishbowl.

Description entails assigning purely descriptive words to one’s observations. To help your patient develop this skill, ask him (her) to describe the sensations he (she) observed in the previous exercise.

Participation entails immersive engagement in an activity. Ask your patient to listen to a song he has never heard before, and then play it again and dance or sing along. Instruct him to engage wholly, conscious of each step or note, without being judgmental or self-conscious. If he feels embarrassed or self-critical, tell him to observe these thoughts and emotions, put them aside, and return to the activity.

A nonjudgmental approach consists of separating out the facts and recognizing emotional responses without clinging to them. To practice this skill, ask your patient to play a song that he likes and one that he dislikes. The patient should listen to each, observing and describing the way they sound without judgment. Tell the patient that if judgmental words or phrases, such as “beautiful,” “ugly,” “I love…,” or “I hate…,” appear as thoughts, he should observe them, put them aside, and then return to nonjudgmental description and observation.

Focusing on 1 thing at a time means dedicating complete attention to a single task, activity, or thought. Give your patient a short paragraph or poem to read. Instruct

Effectiveness involves focusing on what works to attain one’s goals. For this exercise, set up a task for your patient by placing several items in a location that is neither immediately obvious nor readily accessible without an intermediate step. Instruct your patient to obtain these objects. Then guide them as follows:

What do you have to do to get them? Ask permission? Borrow a key? Recruit assistance? Determine the location? Brainstorm ways to obtain the items, and then complete the task.

Mindfulness is actively being aware of one’s inner and outer environments in the present moment. Core mindfulness skills include observation, description, participation, a nonjudgmental approach, focusing on 1 thing at a time, and effectiveness.1

Psychotherapeutic interventions based on each of these skills have been developed to instill a mindful state in psychiatric patients. Evidence suggests these interventions can be helpful when treating borderline personality disorder, somatization, pain, depression, and anxiety, among other conditions.2

Elements of mindfulness can be integrated into brief interventions. The following 6 simple, practical exercises can be used to help patients develop these skills.

Observation involves noticing internal and external experiences, including thoughts and sensations, without applying words or labels. Guide your patient through the following exercise:

Focus your attention on the ground beneath your feet, feeling the pressure, temperature, and texture of this sensation. Do the same with your seat, your breath, and the sounds, sights, and smells of the room. Be aware of your thoughts and watch them come and go like fish in a fishbowl.

Description entails assigning purely descriptive words to one’s observations. To help your patient develop this skill, ask him (her) to describe the sensations he (she) observed in the previous exercise.

Participation entails immersive engagement in an activity. Ask your patient to listen to a song he has never heard before, and then play it again and dance or sing along. Instruct him to engage wholly, conscious of each step or note, without being judgmental or self-conscious. If he feels embarrassed or self-critical, tell him to observe these thoughts and emotions, put them aside, and return to the activity.

A nonjudgmental approach consists of separating out the facts and recognizing emotional responses without clinging to them. To practice this skill, ask your patient to play a song that he likes and one that he dislikes. The patient should listen to each, observing and describing the way they sound without judgment. Tell the patient that if judgmental words or phrases, such as “beautiful,” “ugly,” “I love…,” or “I hate…,” appear as thoughts, he should observe them, put them aside, and then return to nonjudgmental description and observation.

Focusing on 1 thing at a time means dedicating complete attention to a single task, activity, or thought. Give your patient a short paragraph or poem to read. Instruct

Effectiveness involves focusing on what works to attain one’s goals. For this exercise, set up a task for your patient by placing several items in a location that is neither immediately obvious nor readily accessible without an intermediate step. Instruct your patient to obtain these objects. Then guide them as follows:

What do you have to do to get them? Ask permission? Borrow a key? Recruit assistance? Determine the location? Brainstorm ways to obtain the items, and then complete the task.

1. Linehan MM. DBT skills training manual. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2015.

2. Gotink RA, Chu P, Busschbach JJ, et al. Standardised mindfulness-based interventions in healthcare: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0124344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124344.

1. Linehan MM. DBT skills training manual. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2015.

2. Gotink RA, Chu P, Busschbach JJ, et al. Standardised mindfulness-based interventions in healthcare: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0124344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124344.

A practical approach to interviewing a somatizing patient

Somatization is the experience of psychological distress in the form of bodil

Collecting a detailed history of physical symptoms can help the patient feel that you are listening to him (her) and that the chief concern is important. A detailed review of psychiatric symptoms (eg, hallucinations, paranoia, suicidality, etc.) should be deferred until later in the examination. Asking questions relating to psychiatric symptoms early could lead to further resistance by reinforcing negative preconceptions that the patient might have regarding mental illness.

Explicitly express empathy regarding physical symptoms throughout the interview to acknowledge any real suffering the patient is experiencing and to contradict any notion that psychiatric evaluation implies that the suffering could be imaginary.

Ask, “How has this illness affected your life?” This question helps make the connection between the patient’s physical state and social milieu. If somatization is confirmed, then the provider should assist the patient in reversing the arrow of causation. Although the ultimate goal is for the patient to understand how his (her) life has affected the symptoms, simply understanding that there are connections between the two is a start toward this goal.1

Explore the response to the previous question. Expand upon it to elicit a detailed social history, listening for any social stressors.

Obtain family and personal histories of allergies, substance abuse, and medical or psychiatric illness.

Review psychiatric symptoms. Make questions less jarring2 by adapting them to the patient’s situation, such as “Has your illness become so painful that at times you don’t even want to live?”

Perform cognitive and physical examinations. Conducting a physical examination could further reassure the patient that you are not ignoring physical complaints.

Educate the patient that the mind and body are connected and emotions affect how one feels physically. Use examples, such as “When I feel anxious, my heart beats faster” or “A headache might hurt more at work than at the beach.”

Elicit feedback and questions from the patient.

Discuss your treatment plan with the patient. Resistant patients with confirmed somatization disorders might accept psychiatric care as a means of dealing with the stress or pain of their physical symptoms.

Consider asking:

- What would you be doing if you weren’t in the hospital right now?

- Aside from your health, what’s the biggest challenge in your life?

- Everything has a good side and a bad side. Is there anything positive about dealing with your illness? Providing the patient with an example of negative aspects of a good thing (such as the calories in ice cream, the high cost of gold, etc.) can help make this point.

- What would your life look like if you didn’t have these symptoms?

1. Creed F, Guthrie E. Techniques for interviewing the somatising patient. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:467-471.

2. Carlat DJ. The psychiatric interview: a practical guide. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins; 2005.

Somatization is the experience of psychological distress in the form of bodil

Collecting a detailed history of physical symptoms can help the patient feel that you are listening to him (her) and that the chief concern is important. A detailed review of psychiatric symptoms (eg, hallucinations, paranoia, suicidality, etc.) should be deferred until later in the examination. Asking questions relating to psychiatric symptoms early could lead to further resistance by reinforcing negative preconceptions that the patient might have regarding mental illness.

Explicitly express empathy regarding physical symptoms throughout the interview to acknowledge any real suffering the patient is experiencing and to contradict any notion that psychiatric evaluation implies that the suffering could be imaginary.

Ask, “How has this illness affected your life?” This question helps make the connection between the patient’s physical state and social milieu. If somatization is confirmed, then the provider should assist the patient in reversing the arrow of causation. Although the ultimate goal is for the patient to understand how his (her) life has affected the symptoms, simply understanding that there are connections between the two is a start toward this goal.1

Explore the response to the previous question. Expand upon it to elicit a detailed social history, listening for any social stressors.

Obtain family and personal histories of allergies, substance abuse, and medical or psychiatric illness.

Review psychiatric symptoms. Make questions less jarring2 by adapting them to the patient’s situation, such as “Has your illness become so painful that at times you don’t even want to live?”

Perform cognitive and physical examinations. Conducting a physical examination could further reassure the patient that you are not ignoring physical complaints.

Educate the patient that the mind and body are connected and emotions affect how one feels physically. Use examples, such as “When I feel anxious, my heart beats faster” or “A headache might hurt more at work than at the beach.”

Elicit feedback and questions from the patient.

Discuss your treatment plan with the patient. Resistant patients with confirmed somatization disorders might accept psychiatric care as a means of dealing with the stress or pain of their physical symptoms.

Consider asking:

- What would you be doing if you weren’t in the hospital right now?

- Aside from your health, what’s the biggest challenge in your life?

- Everything has a good side and a bad side. Is there anything positive about dealing with your illness? Providing the patient with an example of negative aspects of a good thing (such as the calories in ice cream, the high cost of gold, etc.) can help make this point.

- What would your life look like if you didn’t have these symptoms?

Somatization is the experience of psychological distress in the form of bodil

Collecting a detailed history of physical symptoms can help the patient feel that you are listening to him (her) and that the chief concern is important. A detailed review of psychiatric symptoms (eg, hallucinations, paranoia, suicidality, etc.) should be deferred until later in the examination. Asking questions relating to psychiatric symptoms early could lead to further resistance by reinforcing negative preconceptions that the patient might have regarding mental illness.

Explicitly express empathy regarding physical symptoms throughout the interview to acknowledge any real suffering the patient is experiencing and to contradict any notion that psychiatric evaluation implies that the suffering could be imaginary.