User login

Do no harm: Benztropine revisited

Ms. P, a 63-year-old woman with a history of schizophrenia whose symptoms have been stable on haloperidol 10 mg/d and ziprasidone 40 mg twice daily, presents to the outpatient clinic for a medication review. She mentions that she has noticed problems with her “memory.” She says she has had difficulty remembering names of people and places as well as difficulty concentrating while reading and writing, which she did months ago with ease. A Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is conducted, and Ms. P scores 13/30, indicating moderate cognitive impairment. Visuospatial tasks and clock drawing are intact, but she exhibits impairments in working memory, attention, and concentration. One year ago, Ms. P’s MoCA score was 27/30. She agrees to a neurologic assessment and is referred to neurology for work-up.

Ms. P’s physical examination and routine laboratory tests are all within normal limits. The neurologic exam reveals deficits in working memory, concentration, and attention, but is otherwise unremarkable. MRI reveals mild chronic microvascular changes. The neurology service does not rule out cognitive impairment but recommends adjusting the dosage of Ms. P’s psychiatric medications to elucidate if her impairment of memory and attention is due to medications. However, Ms. P had been managed on her current regimen for several years and had not been hospitalized in many years. Previous attempts to taper her antipsychotics had resulted in worsening symptoms. Ms. P is reluctant to attempt a taper of her antipsychotics because she fears decompensation of her chronic illness. The treating team reviews Ms. P’s medication regimen, and notes that she is receiving benztropine 1 mg twice daily for prophylaxis of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). Ms. P denies past or present symptoms of drug-induced parkinsonism, dystonia, or akathisia as well as constipation, sialorrhea, blurry vision, palpitations, or urinary retention.

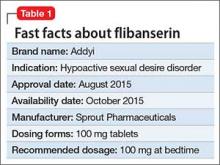

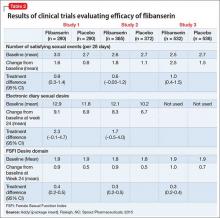

Benztropine is a tropane alkaloid that was synthetized by combining the tropine portion of atropine with the benzhydryl portion of diphenhydramine hydrochloride. It has anticholinergic and antihistaminic properties1 and seems to inhibit the dopamine transporter. Benztropine is indicated for all forms of parkinsonism, including antipsychotic-induced parkinsonism, but is also prescribed for many off-label uses, including sialorrhea and akathisia (although many authors do not recommend anticholinergics for this purpose2,3), and for prophylaxis of EPS. Benztropine can be administered intravenously, intramuscularly, or orally. Given orally, the typical dosing is twice daily with a maximum dose of 6 mg/d. Benztropine is preferred over diphenhydramine and trihexyphenidyl due to adverse effects of sedation or potential for misuse of the medication.1

Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) have been associated with lower rates of neurologic adverse effects compared with first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs). Because SGAs are increasingly prescribed, the use of benztropine (along with other agents such as trihexyphenidyl) for EPS prophylaxis is not an evidence-based practice. However, despite a movement away from prophylactic management of movement disorders, benztropine continues to be prescribed for EPS and/or cholinergic symptoms, despite the peripheral and cognitive adverse effects of this agent and, in many instances, the lack of clear indication for its use.

According to the most recent edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia,4 anticholinergics should only be used for preventing acute dystonia in conjunction with a long-acting injectable antipsychotic. Furthermore, the APA Guideline states anticholinergics may be used for drug-induced parkinsonism when the dose of an antipsychotic cannot be reduced and an alternative agent is required. However, the first-line agent for drug-induced parkinsonism is amantadine, and benztropine should only be considered if amantadine is contraindicated.4 The rationale for this guideline and for judicious use of anticholinergics is that like any pharmacologic treatment, anticholinergics (including benztropine) carry the potential for adverse effects. For benztropine, these range from mild effects such as tachycardia and constipation to paralytic ileus, increased falls, worsening of tardive dyskinesia (TD), and potential cognitive impairment. Literature suggests that the first step in managing cognitive concerns in a patient with schizophrenia should be a close review of medications, and avoidance of agents with anticholinergic properties.5

Prescribing benztropine for EPS

EPS, which include dystonia, akathisia, drug-induced parkinsonism, and TD, are very frequent adverse effects noted with antipsychotics. Benztropine has demonstrated benefit in managing acute dystonia and the APA Guideline recommends IM administration of either benztropine 1 mg or diphenhydramine 25 mg for this purpose.4 However, in our experience, the most frequent indication for long-term prescribing of benztropine is prophylaxis of antipsychoticinduced dystonia. This use was suggested by some older studies. In a 1987 study by Boyer et al,6 patients who were administered benztropine with haloperidol did not develop acute dystonia, while patients who received haloperidol alone developed dystonia. However, this was a small retrospective study with methodological issues. Boyer et al6 suggested discontinuing prophylaxis with benztropine within 1 week, as acute dystonia occurred within 2.5 days. Other researchers7,8 have argued that short-term prophylaxis with benztropine for 1 week may work, especially during treatment with high-potency antipsychotics. However, in a review of the use of anticholinergics in conjunction with antipsychotics, Desmarais et al5 concluded that there is no need for prophylaxis and recommended alternative treatments. As we have noticed in Ms. P and other patients treated in our facilities, benztropine is frequently continued indefinitely without a clinical indication for its continuous use. Assessment and indication for continued use of benztropine should be considered regularly, and it should be discontinued when there is no clear indication for its use or when adverse effects emerge.

Prescribing benztropine for TD

TD is a subtype of tardive syndromes associated with the use of antipsychotics. It is characterized by repetitive involuntary movements such as lip smacking, puckering, chewing, or tongue protrusion. Proposed pathophysiological mechanisms include dopamine receptor hypersensitivity, N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor excitotoxicity, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-containing neuron activity.

According to the APA Guideline, evidence of benztropine’s efficacy for the prevention of TD is lacking.4 A 2018 Cochrane systematic review9 was unable to provide a definitive conclusion regarding the effectiveness of benztropine and other anticholinergics for the treatment of antipsychotic-induced TD. While many clinicians believe that benztropine can be used to treat all types of EPS, there are no clear instances in reviewed literature where the efficacy of benztropine for treating TD could be reliably demonstrated. Furthermore, some literature suggests that anticholinergics such as benztropine increase the risk of developing TD.5,10 The mechanism underlying benztropine’s ability to precipitate or exacerbate abnormal movements is unclear, though it is theorized that anticholinergic medications may inhibit dopamine reuptake into neurons, thus leading to an excess of dopamine in the synaptic cleft that manifests as dyskinesias.10 Some authors also recommend that the first step in the management of TD should be to gradually discontinue anticholinergics, as this has been associated with improvement in TD.11

Continue to: Prescribing anticholinergics in specific patient populations...

Prescribing anticholinergics in specific patient populations

In addition to the adverse effects described above, benztropine can affect cognition, as we observed in Ms. P. The cholinergic system plays a role in human cognition, and blockade of muscarinic receptors has been associated with impairments in working memory and prefrontal tasks.12 These adverse cognitive effects are more pronounced in certain populations, including patients with schizophrenia and older adults.

Schizophrenia is associated with declining cognitive function, and the cognitive faculties of patients with schizophrenia may be worsened by anticholinergics. In patients with schizophrenia, social interactions and social integration are often impacted by profound negative symptoms such as social withdrawal and poverty of thought and speech.13 In a double-blind study by Baker et al,14 benztropine was found to have an impact on attention and concentration in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Baker et al14 found that patients with schizophrenia who were switched from benztropine to placebo increased their overall Wechsler Memory Scale scores compared to those maintained on benztropine. One crosssectional analysis found that a higher anticholinergic burden was associated with impairments across all cognitive domains, including memory, attention/control, executive and visuospatial functioning, and motor speed domains.15 Importantly, a higher anticholinergic medication burden was associated with worse cognitive performance.15 In addition to impairments in cognitive processing, anticholinergics have been associated with a decreased ability to benefit from psychosocial programs and impaired abilities to manage activities of daily living.4 In another study exploring the effects of discontinuing anticholinergics and the impact on movement disorders, Desmarais et al16 found patients experienced a significant improvement in scores on the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia after discontinuing anticholinergics. Vinogradov et al17 noted that “serum anticholinergic activity in schizophrenia patients shows a significant association with impaired performance in measures of verbal working memory and verbal learning memory and was significantly associated with a lowered response to an intensive course of computerized cognitive training.” They felt their findings underscored the cognitive cost of medications with high anticholinergic burden.

Geriatric patients. Careful consideration should be given before starting benztropine in patients age ≥65. The 2019 American Geriatric Society’s Beers Criteria18 recommend avoiding benztropine in geriatric patients; the level of recommendation is strong. Furthermore, the American Geriatric Society designates benztropine as a medication that should be avoided, and a nondrug approach or alternative medication be prescribed independent of the patient’s condition or diagnosis. In a recently published case report, Esang et al19 highlighted several salient findings from previous studies on the risks associated with anticholinergic use:

- any medications a patient takes with anticholinergic properties contribute to the overall anticholinergic load of a patient’s medication regimen

- the higher the anticholinergic burden, the greater the cognitive deficits

- switching from an FGA to an SGA may decrease the risk of EPS and may limit the need for anticholinergic medications such as benztropine for a particular patient.

One must also consider that the effects of multiple medications with anticholinergic properties is probably cumulative.

Alternatives for treating drug-induced parkinsonism

Antipsychotics exert their effects through antagonism of the D2 receptor, and this is the same mechanism that leads to parkinsonism. Specifically, the mechanism is believed to be D2 receptor antagonism in the striatum leading to disinhibition of striatal neurons containing GABA.11 This disinhibition of medium spiny neurons is propagated when acetylcholine is released from cholinergic interneurons. Anticholinergics such as benztropine can remedy symptoms by blocking the signal of acetylcholine on the M1 receptors on medium spiny neurons. However, benztropine also has the propensity to decrease cholinergic transmission, thereby impairing storage of new information into long-term memory as well as impair perception of time—similar to effects seen with (for instance) diphenhydramine.20

The first step in managing drug-induced parkinsonism is to monitor symptoms. The APA Guideline recommends monitoring for acute-onset EPS at weekly intervals when beginning treatment and until stable for 2 weeks, and then monitoring at every follow-up visit thereafter.4 The next recommendation for long-term management of drug-induced parkinsonism is reducing the antipsychotic dose, or replacing the patient’s antipsychotic with an antipsychotic that is less likely to precipitate parkinsonism,4 such as quetiapine, iloperidone, or clozapine.11 If dose reduction is not possible, and the patient’s symptoms are severe, pharmacologic management is indicated. The APA Guideline recommends amantadine as a first-line agent because it is associated with fewer peripheral adverse effects and less impairment in cognition compared with benztropine.4 In a small (N = 60) doubleblind crossover trial, Gelenberg et al20 found benztropine 4 mg/d—but not amantadine 200 mg/d—impaired free recall and perception of time, and participants’ perception of their own memory impairment was significantly greater with benztropine. Amantadine has also been compared to biperiden, a relatively selective M1 muscarinic receptor muscarinic agent. In a separate double-blind crossover study of 26 patients with chronic schizophrenia, Silver and Geraisy21 found that compared to amantadine, biperiden was associated with worse memory performance. The recommended starting dose of amantadine for parkinsonism is 100 mg in the morning, increased to 100 mg twice a day and titrated to a maximum daily dose of 300 mg/d in divided doses.4

Continue to: Alternatives for treating drug-induced akathisia...

Alternatives for treating drug-induced akathisia

Akathisia remains a relatively common adverse effect of SGAs, and the profound physical distress and impaired functioning caused by akathisia necessitates pharmacologic treatment. Despite frequent use in practice for presumed benefit in akathisia, benztropine is not effective for the treatment of akathisia and the APA Guideline recommends that long-term management should begin with an antipsychotic dose reduction, followed by a switch to an agent with less propensity to incite akathisia.4 Acute manifestations of akathisia must be treated, and mirtazapine, propranolol, or clonazepam may be considered as alternatives.4 Mirtazapine is dosed 7.5 mg to 10 mg nightly for akathisia, though it should be used in caution in patients at risk for mania.4 Mirtazapine’s potent 5-HT2A blockade at low doses may contribute to its utility in treating akathisia.2 Propranolol, a nonselective lipophilic beta-adrenergic antagonist, also has demonstrated efficacy in managing akathisia, with recommended dosing of 40 mg to 80 mg twice daily.2 Benzodiazepines such as clonazepam require judicious use for akathisia because they may also precipitate or exacerbate cognitive impairment.4

Alternatives for treating TD

As mentioned above, benztropine is not recommended for the treatment of TD.1 The Box4,22,23 outlines potential treatment options for TD.

Box

Monitoring is the first step in the prevention of tardive dyskinesia (TD). The American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia recommends patients receiving first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) be monitored every 6 months, those prescribed second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) be monitored every 12 months, and twice as frequent monitoring for geriatric patients and those who developed involuntary movements rapidly after starting an antipsychotic.4

The APA Guideline recommends decreasing or gradually tapering antipsychotics as another strategy for preventing TD.4 However, these recommendations should be weighed against the risk of short-term antipsychotic withdrawal. Withdrawal of D2 antagonists is associated with worsening of dyskinesias or withdrawal dyskinesia and psychotic decompensation.22

Current treatment recommendations give preference to the importance of preventing development of TD by tapering to the lowest dose of antipsychotic needed to control symptoms for the shortest duration possible.22 Thereafter, if treatment intervention is needed, consideration should be given to the following pharmacological interventions in order from highest level of recommendation (Grade A) to lowest (Grade C):

A: vesicular monoamine transporter-2 inhibitors deutetrabenazine and valbenazine

B: clonazepam, ginkgo biloba

C: amantadine, tetrabenazine, and globus pallidus interna deep brain stimulation.22

There is insufficient evidence to support or refute withdrawing causative agents or switching from FGAs to SGAs to treat TD.22 Furthermore, for many patients with schizophrenia, a gradual discontinuation of their antipsychotic must be weighed against the risk of relapse.23

Valbenazine and deutetrabenazine have been demonstrated to be efficacious and are FDA-approved for managing TD. The initial dose of valbenazine is 40 mg/d. Common adverse effects include somnolence and fatigue/ sedation. Valbenazine should be avoided in patients with QT prolongation or arrhythmias. Deutetrabenazine has less impact on the cytochrome P450 2D6 enzyme and therefore does not require genotyping as would be the case for patients who are receiving >50 mg/d of tetrabenazine. The starting dose of deutetrabenazine is 6 mg/d. Adverse effects include depression, suicidality, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, parkinsonism, and QT prolongation. Deutetrabenazine is contraindicated in patients who are suicidal or have untreated depression, hepatic impairment, or concomitant use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors.22 Deutetrabenazine is an isomer of tetrabenazine; however, evidence supporting the parent compound suggests limited use due to increased risk of adverse effects compared with valbenazine and deutetrabenazine.23 Tetrabenazine may be considered as an adjunctive treatment or used as a single agent if valbenazine or deutetrabenazine are not accessible.22

Discontinuing benztropine

Benztropine is recommended as a firstline agent for the management of acute dystonia, and it may be used temporarily for drug-induced parkinsonism, but it is not recommended to prevent EPS or TD. Given the multitude of adverse effects and cognitive impairment noted with anticholinergics, tapering should be considered for patients receiving an anticholinergic agent such as benztropine. Based on their review of earlier studies, Desmarais et al5 suggest a gradual 3-month discontinuation of benztropine. Multiple studies have demonstrated an ability to taper anticholinergics in days to months.4 However, gradual discontinuation is advisable to avoid cholinergic rebound and the reemergence of EPS, and to decrease the risk of neuroleptic malignant syndrome associated with sudden discontinuation.5 One suggested taper regimen is a decrease of 0.5 mg benztropine every week. Amantadine may be considered if parkinsonism is noted during the taper. Patients on benztropine may develop rebound symptoms, such as vivid dreams/nightmares; if this occurs, the taper rate can be slowed to a decrease of 0.5 mg every 2 weeks.4

Continue to: First do no harm...

First do no harm

Psychiatrists commonly prescribe benztropine to prevent EPS and TD, but available literature does not support the efficacy of benztropine for mitigating drug-induced parkinsonism, and studies report benztropine may significantly worsen cognitive processes and exacerbate TD.16 In addition, benztropine misuse has been correlated with euphoria and psychosis.16 More than 3 decades ago, the World Health Organization Heads of Centres Collaborating in WHO-Coordinated Studies on Biological Aspects of Mental Illness issued a consensus statement24 discouraging the prophylactic use of anticholinergics for patients receiving antipsychotics, yet we still see patients on an indefinite regimen of benztropine.

As clinicians, our goals should be to optimize a patient’s functioning and quality of life, and to use the lowest dose of medication along with the fewest medications necessary to avoid adverse effects such as EPS. Benztropine is recommended as a first-line agent for the management of acute dystonia, but its continued or indefinite use to prevent antipsychotic-induced adverse effects is not recommended. While all pharmacologic interventions carry a risk of adverse effects, weighing the risk of those effects against the clinical benefits is the prerogative of a skilled clinician. Benztropine and other anticholinergics prescribed for prophylactic purposes have numerous adverse effects, limited clinical utility, and a deleterious effect on quality of life. Furthermore, benztropine prophylaxis of drug-induced parkinsonism does not seem to be warranted, and the risks do not seem to outweigh the harm benztropine may cause, with the possible exception of “prophylactic” treatment of dystonia that is discontinued in a few days, as some researchers have suggested.6-8 The preventive value of benztropine has not been demonstrated. It is time we took inventory of medications that might cause more harm than good, rely on current treatment guidelines instead of habit, and use these agents judiciously while considering replacement with novel, safer medications whenever possible.

CASE CONTINUED

The clinical team considers benztropine’s ability to cause cognitive effects, and decides to taper and discontinue it over 1 month. Ms. P is seen in an outpatient clinic within 1 month of discontinuing benztropine. She reports that her difficulty remembering words and details has improved. She also says that she is now able to concentrate on writing and reading. The consulting neurologist also notes improvement. Ms. P continues to report improvement in symptoms over the next 2 months of follow-up, and says that her mood improved and she has less apathy.

Bottom Line

Benztropine is a first-line medication for acute dystonia, but its continued or indefinite use for preventing antipsychotic-induced adverse effects is not recommended. Given the multitude of adverse effects and cognitive impairment noted with anticholinergics, tapering should be considered for patients receiving an anticholinergic medication such as benztropine.

1. Cogentin [package insert]. McPherson, KS: Lundbeck Inc; 2013.

2. Poyurovsky M, Weizman A. Treatment of antipsychoticrelated akathisia revisited. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015; 35(6):711-714.

3. Salem H, Nagpal C, Pigott T, et al. Revisiting antipsychoticinduced akathisia: current issues and prospective challenges. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15(5):789-798.

4. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2021.

5. Desmarais JE, Beauclair L, Margolese HC. Anticholinergics in the era of atypical antipsychotics: short-term or long-term treatment? J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26(9):1167-1174.

6. Boyer WF, Bakalar NH, Lake CR. Anticholinergic prophylaxis of acute haloperidol-induced acute dystonic reactions. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1987;7(3):164-166.

7. Winslow RS, Stillner V, Coons DJ, et al. Prevention of acute dystonic reactions in patients beginning high-potency neuroleptics. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(6):706-710.

8. Stern TA, Anderson WH. Benztropine prophylaxis of dystonic reactions. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1979; 61(3):261-262.

9. Bergman H, Soares‐Weiser K. Anticholinergic medication for antipsychotic‐induced tardive dyskinesia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1(1):CD000204. doi:10.1002/ 14651858.CD000204.pub2

10. Howrie DL, Rowley AH, Krenzelok EP. Benztropineinduced acute dystonic reaction. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15(5):594-596.

11. Ward KM, Citrome L. Antipsychotic-related movement disorders: drug-induced parkinsonism vs. tardive dyskinesia--key differences in pathophysiology and clinical management. Neurol Ther. 2018;7(2): 233-248.

12. Wijegunaratne H, Qazi H, Koola M. Chronic and bedtime use of benztropine with antipsychotics: is it necessary? Schizophr Res. 2014;153(1-3):248-249.

13. Möller HJ. The relevance of negative symptoms in schizophrenia and how to treat them with psychopharmaceuticals? Psychiatr Danub. 2016;28(4):435-440.

14. Baker LA, Cheng LY, Amara IB. The withdrawal of benztropine mesylate in chronic schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1983;143:584-590.

15. Joshi YB, Thomas ML, Braff DL, et al. Anticholinergic medication burden-associated cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178(9):838-847.

16. Desmarais JE, Beauclair E, Annable L, et al. Effects of discontinuing anticholinergic treatment on movement disorders, cognition and psychopathology in patients with schizophrenia. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(6): 257-267.

17. Vinogradov S, Fisher M, Warm H, et al. The cognitive cost of anticholinergic burden: decreased response to cognitive training in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9): 1055-1062.

18. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674-694.

19. Esang M, Person US, Izekor OO, et al. An unlikely case of benztropine misuse in an elderly schizophrenic. Cureus. 2021;13(2):e13434. doi:10.7759/cureus.13434

20. Gelenberg AJ, Van Putten T, Lavori PW, et al. Anticholinergic effects on memory: benztropine versus amantadine. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1989;9(3):180-185.

21. Silver H, Geraisy N. Effects of biperiden and amantadine on memory in medicated chronic schizophrenic patients. A double-blind cross-over study. Br J Psychiatry. 1995; 166(2):241-243.

22. Bhidayasiri R, Jitkritsadakul O, Friedman J, et al. Updating the recommendations for treatment of tardive syndromes: a systematic review of new evidence and practical treatment algorithm. J Neurol Sci. 2018;389:67-75.

23. Ricciardi L, Pringsheim T, Barnes TRE, et al. Treatment recommendations for tardive dyskinesia. Canadian J Psychiatry. 2019;64(6):388-399.

24. Prophylactic use of anticholinergics in patients on long-term neuroleptic treatment. A consensus statement. World Health Organization heads of centres collaborating in WHO coordinated studies on biological aspects of mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;156:412.

Ms. P, a 63-year-old woman with a history of schizophrenia whose symptoms have been stable on haloperidol 10 mg/d and ziprasidone 40 mg twice daily, presents to the outpatient clinic for a medication review. She mentions that she has noticed problems with her “memory.” She says she has had difficulty remembering names of people and places as well as difficulty concentrating while reading and writing, which she did months ago with ease. A Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is conducted, and Ms. P scores 13/30, indicating moderate cognitive impairment. Visuospatial tasks and clock drawing are intact, but she exhibits impairments in working memory, attention, and concentration. One year ago, Ms. P’s MoCA score was 27/30. She agrees to a neurologic assessment and is referred to neurology for work-up.

Ms. P’s physical examination and routine laboratory tests are all within normal limits. The neurologic exam reveals deficits in working memory, concentration, and attention, but is otherwise unremarkable. MRI reveals mild chronic microvascular changes. The neurology service does not rule out cognitive impairment but recommends adjusting the dosage of Ms. P’s psychiatric medications to elucidate if her impairment of memory and attention is due to medications. However, Ms. P had been managed on her current regimen for several years and had not been hospitalized in many years. Previous attempts to taper her antipsychotics had resulted in worsening symptoms. Ms. P is reluctant to attempt a taper of her antipsychotics because she fears decompensation of her chronic illness. The treating team reviews Ms. P’s medication regimen, and notes that she is receiving benztropine 1 mg twice daily for prophylaxis of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). Ms. P denies past or present symptoms of drug-induced parkinsonism, dystonia, or akathisia as well as constipation, sialorrhea, blurry vision, palpitations, or urinary retention.

Benztropine is a tropane alkaloid that was synthetized by combining the tropine portion of atropine with the benzhydryl portion of diphenhydramine hydrochloride. It has anticholinergic and antihistaminic properties1 and seems to inhibit the dopamine transporter. Benztropine is indicated for all forms of parkinsonism, including antipsychotic-induced parkinsonism, but is also prescribed for many off-label uses, including sialorrhea and akathisia (although many authors do not recommend anticholinergics for this purpose2,3), and for prophylaxis of EPS. Benztropine can be administered intravenously, intramuscularly, or orally. Given orally, the typical dosing is twice daily with a maximum dose of 6 mg/d. Benztropine is preferred over diphenhydramine and trihexyphenidyl due to adverse effects of sedation or potential for misuse of the medication.1

Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) have been associated with lower rates of neurologic adverse effects compared with first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs). Because SGAs are increasingly prescribed, the use of benztropine (along with other agents such as trihexyphenidyl) for EPS prophylaxis is not an evidence-based practice. However, despite a movement away from prophylactic management of movement disorders, benztropine continues to be prescribed for EPS and/or cholinergic symptoms, despite the peripheral and cognitive adverse effects of this agent and, in many instances, the lack of clear indication for its use.

According to the most recent edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia,4 anticholinergics should only be used for preventing acute dystonia in conjunction with a long-acting injectable antipsychotic. Furthermore, the APA Guideline states anticholinergics may be used for drug-induced parkinsonism when the dose of an antipsychotic cannot be reduced and an alternative agent is required. However, the first-line agent for drug-induced parkinsonism is amantadine, and benztropine should only be considered if amantadine is contraindicated.4 The rationale for this guideline and for judicious use of anticholinergics is that like any pharmacologic treatment, anticholinergics (including benztropine) carry the potential for adverse effects. For benztropine, these range from mild effects such as tachycardia and constipation to paralytic ileus, increased falls, worsening of tardive dyskinesia (TD), and potential cognitive impairment. Literature suggests that the first step in managing cognitive concerns in a patient with schizophrenia should be a close review of medications, and avoidance of agents with anticholinergic properties.5

Prescribing benztropine for EPS

EPS, which include dystonia, akathisia, drug-induced parkinsonism, and TD, are very frequent adverse effects noted with antipsychotics. Benztropine has demonstrated benefit in managing acute dystonia and the APA Guideline recommends IM administration of either benztropine 1 mg or diphenhydramine 25 mg for this purpose.4 However, in our experience, the most frequent indication for long-term prescribing of benztropine is prophylaxis of antipsychoticinduced dystonia. This use was suggested by some older studies. In a 1987 study by Boyer et al,6 patients who were administered benztropine with haloperidol did not develop acute dystonia, while patients who received haloperidol alone developed dystonia. However, this was a small retrospective study with methodological issues. Boyer et al6 suggested discontinuing prophylaxis with benztropine within 1 week, as acute dystonia occurred within 2.5 days. Other researchers7,8 have argued that short-term prophylaxis with benztropine for 1 week may work, especially during treatment with high-potency antipsychotics. However, in a review of the use of anticholinergics in conjunction with antipsychotics, Desmarais et al5 concluded that there is no need for prophylaxis and recommended alternative treatments. As we have noticed in Ms. P and other patients treated in our facilities, benztropine is frequently continued indefinitely without a clinical indication for its continuous use. Assessment and indication for continued use of benztropine should be considered regularly, and it should be discontinued when there is no clear indication for its use or when adverse effects emerge.

Prescribing benztropine for TD

TD is a subtype of tardive syndromes associated with the use of antipsychotics. It is characterized by repetitive involuntary movements such as lip smacking, puckering, chewing, or tongue protrusion. Proposed pathophysiological mechanisms include dopamine receptor hypersensitivity, N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor excitotoxicity, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-containing neuron activity.

According to the APA Guideline, evidence of benztropine’s efficacy for the prevention of TD is lacking.4 A 2018 Cochrane systematic review9 was unable to provide a definitive conclusion regarding the effectiveness of benztropine and other anticholinergics for the treatment of antipsychotic-induced TD. While many clinicians believe that benztropine can be used to treat all types of EPS, there are no clear instances in reviewed literature where the efficacy of benztropine for treating TD could be reliably demonstrated. Furthermore, some literature suggests that anticholinergics such as benztropine increase the risk of developing TD.5,10 The mechanism underlying benztropine’s ability to precipitate or exacerbate abnormal movements is unclear, though it is theorized that anticholinergic medications may inhibit dopamine reuptake into neurons, thus leading to an excess of dopamine in the synaptic cleft that manifests as dyskinesias.10 Some authors also recommend that the first step in the management of TD should be to gradually discontinue anticholinergics, as this has been associated with improvement in TD.11

Continue to: Prescribing anticholinergics in specific patient populations...

Prescribing anticholinergics in specific patient populations

In addition to the adverse effects described above, benztropine can affect cognition, as we observed in Ms. P. The cholinergic system plays a role in human cognition, and blockade of muscarinic receptors has been associated with impairments in working memory and prefrontal tasks.12 These adverse cognitive effects are more pronounced in certain populations, including patients with schizophrenia and older adults.

Schizophrenia is associated with declining cognitive function, and the cognitive faculties of patients with schizophrenia may be worsened by anticholinergics. In patients with schizophrenia, social interactions and social integration are often impacted by profound negative symptoms such as social withdrawal and poverty of thought and speech.13 In a double-blind study by Baker et al,14 benztropine was found to have an impact on attention and concentration in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Baker et al14 found that patients with schizophrenia who were switched from benztropine to placebo increased their overall Wechsler Memory Scale scores compared to those maintained on benztropine. One crosssectional analysis found that a higher anticholinergic burden was associated with impairments across all cognitive domains, including memory, attention/control, executive and visuospatial functioning, and motor speed domains.15 Importantly, a higher anticholinergic medication burden was associated with worse cognitive performance.15 In addition to impairments in cognitive processing, anticholinergics have been associated with a decreased ability to benefit from psychosocial programs and impaired abilities to manage activities of daily living.4 In another study exploring the effects of discontinuing anticholinergics and the impact on movement disorders, Desmarais et al16 found patients experienced a significant improvement in scores on the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia after discontinuing anticholinergics. Vinogradov et al17 noted that “serum anticholinergic activity in schizophrenia patients shows a significant association with impaired performance in measures of verbal working memory and verbal learning memory and was significantly associated with a lowered response to an intensive course of computerized cognitive training.” They felt their findings underscored the cognitive cost of medications with high anticholinergic burden.

Geriatric patients. Careful consideration should be given before starting benztropine in patients age ≥65. The 2019 American Geriatric Society’s Beers Criteria18 recommend avoiding benztropine in geriatric patients; the level of recommendation is strong. Furthermore, the American Geriatric Society designates benztropine as a medication that should be avoided, and a nondrug approach or alternative medication be prescribed independent of the patient’s condition or diagnosis. In a recently published case report, Esang et al19 highlighted several salient findings from previous studies on the risks associated with anticholinergic use:

- any medications a patient takes with anticholinergic properties contribute to the overall anticholinergic load of a patient’s medication regimen

- the higher the anticholinergic burden, the greater the cognitive deficits

- switching from an FGA to an SGA may decrease the risk of EPS and may limit the need for anticholinergic medications such as benztropine for a particular patient.

One must also consider that the effects of multiple medications with anticholinergic properties is probably cumulative.

Alternatives for treating drug-induced parkinsonism

Antipsychotics exert their effects through antagonism of the D2 receptor, and this is the same mechanism that leads to parkinsonism. Specifically, the mechanism is believed to be D2 receptor antagonism in the striatum leading to disinhibition of striatal neurons containing GABA.11 This disinhibition of medium spiny neurons is propagated when acetylcholine is released from cholinergic interneurons. Anticholinergics such as benztropine can remedy symptoms by blocking the signal of acetylcholine on the M1 receptors on medium spiny neurons. However, benztropine also has the propensity to decrease cholinergic transmission, thereby impairing storage of new information into long-term memory as well as impair perception of time—similar to effects seen with (for instance) diphenhydramine.20

The first step in managing drug-induced parkinsonism is to monitor symptoms. The APA Guideline recommends monitoring for acute-onset EPS at weekly intervals when beginning treatment and until stable for 2 weeks, and then monitoring at every follow-up visit thereafter.4 The next recommendation for long-term management of drug-induced parkinsonism is reducing the antipsychotic dose, or replacing the patient’s antipsychotic with an antipsychotic that is less likely to precipitate parkinsonism,4 such as quetiapine, iloperidone, or clozapine.11 If dose reduction is not possible, and the patient’s symptoms are severe, pharmacologic management is indicated. The APA Guideline recommends amantadine as a first-line agent because it is associated with fewer peripheral adverse effects and less impairment in cognition compared with benztropine.4 In a small (N = 60) doubleblind crossover trial, Gelenberg et al20 found benztropine 4 mg/d—but not amantadine 200 mg/d—impaired free recall and perception of time, and participants’ perception of their own memory impairment was significantly greater with benztropine. Amantadine has also been compared to biperiden, a relatively selective M1 muscarinic receptor muscarinic agent. In a separate double-blind crossover study of 26 patients with chronic schizophrenia, Silver and Geraisy21 found that compared to amantadine, biperiden was associated with worse memory performance. The recommended starting dose of amantadine for parkinsonism is 100 mg in the morning, increased to 100 mg twice a day and titrated to a maximum daily dose of 300 mg/d in divided doses.4

Continue to: Alternatives for treating drug-induced akathisia...

Alternatives for treating drug-induced akathisia

Akathisia remains a relatively common adverse effect of SGAs, and the profound physical distress and impaired functioning caused by akathisia necessitates pharmacologic treatment. Despite frequent use in practice for presumed benefit in akathisia, benztropine is not effective for the treatment of akathisia and the APA Guideline recommends that long-term management should begin with an antipsychotic dose reduction, followed by a switch to an agent with less propensity to incite akathisia.4 Acute manifestations of akathisia must be treated, and mirtazapine, propranolol, or clonazepam may be considered as alternatives.4 Mirtazapine is dosed 7.5 mg to 10 mg nightly for akathisia, though it should be used in caution in patients at risk for mania.4 Mirtazapine’s potent 5-HT2A blockade at low doses may contribute to its utility in treating akathisia.2 Propranolol, a nonselective lipophilic beta-adrenergic antagonist, also has demonstrated efficacy in managing akathisia, with recommended dosing of 40 mg to 80 mg twice daily.2 Benzodiazepines such as clonazepam require judicious use for akathisia because they may also precipitate or exacerbate cognitive impairment.4

Alternatives for treating TD

As mentioned above, benztropine is not recommended for the treatment of TD.1 The Box4,22,23 outlines potential treatment options for TD.

Box

Monitoring is the first step in the prevention of tardive dyskinesia (TD). The American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia recommends patients receiving first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) be monitored every 6 months, those prescribed second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) be monitored every 12 months, and twice as frequent monitoring for geriatric patients and those who developed involuntary movements rapidly after starting an antipsychotic.4

The APA Guideline recommends decreasing or gradually tapering antipsychotics as another strategy for preventing TD.4 However, these recommendations should be weighed against the risk of short-term antipsychotic withdrawal. Withdrawal of D2 antagonists is associated with worsening of dyskinesias or withdrawal dyskinesia and psychotic decompensation.22

Current treatment recommendations give preference to the importance of preventing development of TD by tapering to the lowest dose of antipsychotic needed to control symptoms for the shortest duration possible.22 Thereafter, if treatment intervention is needed, consideration should be given to the following pharmacological interventions in order from highest level of recommendation (Grade A) to lowest (Grade C):

A: vesicular monoamine transporter-2 inhibitors deutetrabenazine and valbenazine

B: clonazepam, ginkgo biloba

C: amantadine, tetrabenazine, and globus pallidus interna deep brain stimulation.22

There is insufficient evidence to support or refute withdrawing causative agents or switching from FGAs to SGAs to treat TD.22 Furthermore, for many patients with schizophrenia, a gradual discontinuation of their antipsychotic must be weighed against the risk of relapse.23

Valbenazine and deutetrabenazine have been demonstrated to be efficacious and are FDA-approved for managing TD. The initial dose of valbenazine is 40 mg/d. Common adverse effects include somnolence and fatigue/ sedation. Valbenazine should be avoided in patients with QT prolongation or arrhythmias. Deutetrabenazine has less impact on the cytochrome P450 2D6 enzyme and therefore does not require genotyping as would be the case for patients who are receiving >50 mg/d of tetrabenazine. The starting dose of deutetrabenazine is 6 mg/d. Adverse effects include depression, suicidality, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, parkinsonism, and QT prolongation. Deutetrabenazine is contraindicated in patients who are suicidal or have untreated depression, hepatic impairment, or concomitant use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors.22 Deutetrabenazine is an isomer of tetrabenazine; however, evidence supporting the parent compound suggests limited use due to increased risk of adverse effects compared with valbenazine and deutetrabenazine.23 Tetrabenazine may be considered as an adjunctive treatment or used as a single agent if valbenazine or deutetrabenazine are not accessible.22

Discontinuing benztropine

Benztropine is recommended as a firstline agent for the management of acute dystonia, and it may be used temporarily for drug-induced parkinsonism, but it is not recommended to prevent EPS or TD. Given the multitude of adverse effects and cognitive impairment noted with anticholinergics, tapering should be considered for patients receiving an anticholinergic agent such as benztropine. Based on their review of earlier studies, Desmarais et al5 suggest a gradual 3-month discontinuation of benztropine. Multiple studies have demonstrated an ability to taper anticholinergics in days to months.4 However, gradual discontinuation is advisable to avoid cholinergic rebound and the reemergence of EPS, and to decrease the risk of neuroleptic malignant syndrome associated with sudden discontinuation.5 One suggested taper regimen is a decrease of 0.5 mg benztropine every week. Amantadine may be considered if parkinsonism is noted during the taper. Patients on benztropine may develop rebound symptoms, such as vivid dreams/nightmares; if this occurs, the taper rate can be slowed to a decrease of 0.5 mg every 2 weeks.4

Continue to: First do no harm...

First do no harm

Psychiatrists commonly prescribe benztropine to prevent EPS and TD, but available literature does not support the efficacy of benztropine for mitigating drug-induced parkinsonism, and studies report benztropine may significantly worsen cognitive processes and exacerbate TD.16 In addition, benztropine misuse has been correlated with euphoria and psychosis.16 More than 3 decades ago, the World Health Organization Heads of Centres Collaborating in WHO-Coordinated Studies on Biological Aspects of Mental Illness issued a consensus statement24 discouraging the prophylactic use of anticholinergics for patients receiving antipsychotics, yet we still see patients on an indefinite regimen of benztropine.

As clinicians, our goals should be to optimize a patient’s functioning and quality of life, and to use the lowest dose of medication along with the fewest medications necessary to avoid adverse effects such as EPS. Benztropine is recommended as a first-line agent for the management of acute dystonia, but its continued or indefinite use to prevent antipsychotic-induced adverse effects is not recommended. While all pharmacologic interventions carry a risk of adverse effects, weighing the risk of those effects against the clinical benefits is the prerogative of a skilled clinician. Benztropine and other anticholinergics prescribed for prophylactic purposes have numerous adverse effects, limited clinical utility, and a deleterious effect on quality of life. Furthermore, benztropine prophylaxis of drug-induced parkinsonism does not seem to be warranted, and the risks do not seem to outweigh the harm benztropine may cause, with the possible exception of “prophylactic” treatment of dystonia that is discontinued in a few days, as some researchers have suggested.6-8 The preventive value of benztropine has not been demonstrated. It is time we took inventory of medications that might cause more harm than good, rely on current treatment guidelines instead of habit, and use these agents judiciously while considering replacement with novel, safer medications whenever possible.

CASE CONTINUED

The clinical team considers benztropine’s ability to cause cognitive effects, and decides to taper and discontinue it over 1 month. Ms. P is seen in an outpatient clinic within 1 month of discontinuing benztropine. She reports that her difficulty remembering words and details has improved. She also says that she is now able to concentrate on writing and reading. The consulting neurologist also notes improvement. Ms. P continues to report improvement in symptoms over the next 2 months of follow-up, and says that her mood improved and she has less apathy.

Bottom Line

Benztropine is a first-line medication for acute dystonia, but its continued or indefinite use for preventing antipsychotic-induced adverse effects is not recommended. Given the multitude of adverse effects and cognitive impairment noted with anticholinergics, tapering should be considered for patients receiving an anticholinergic medication such as benztropine.

Ms. P, a 63-year-old woman with a history of schizophrenia whose symptoms have been stable on haloperidol 10 mg/d and ziprasidone 40 mg twice daily, presents to the outpatient clinic for a medication review. She mentions that she has noticed problems with her “memory.” She says she has had difficulty remembering names of people and places as well as difficulty concentrating while reading and writing, which she did months ago with ease. A Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is conducted, and Ms. P scores 13/30, indicating moderate cognitive impairment. Visuospatial tasks and clock drawing are intact, but she exhibits impairments in working memory, attention, and concentration. One year ago, Ms. P’s MoCA score was 27/30. She agrees to a neurologic assessment and is referred to neurology for work-up.

Ms. P’s physical examination and routine laboratory tests are all within normal limits. The neurologic exam reveals deficits in working memory, concentration, and attention, but is otherwise unremarkable. MRI reveals mild chronic microvascular changes. The neurology service does not rule out cognitive impairment but recommends adjusting the dosage of Ms. P’s psychiatric medications to elucidate if her impairment of memory and attention is due to medications. However, Ms. P had been managed on her current regimen for several years and had not been hospitalized in many years. Previous attempts to taper her antipsychotics had resulted in worsening symptoms. Ms. P is reluctant to attempt a taper of her antipsychotics because she fears decompensation of her chronic illness. The treating team reviews Ms. P’s medication regimen, and notes that she is receiving benztropine 1 mg twice daily for prophylaxis of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). Ms. P denies past or present symptoms of drug-induced parkinsonism, dystonia, or akathisia as well as constipation, sialorrhea, blurry vision, palpitations, or urinary retention.

Benztropine is a tropane alkaloid that was synthetized by combining the tropine portion of atropine with the benzhydryl portion of diphenhydramine hydrochloride. It has anticholinergic and antihistaminic properties1 and seems to inhibit the dopamine transporter. Benztropine is indicated for all forms of parkinsonism, including antipsychotic-induced parkinsonism, but is also prescribed for many off-label uses, including sialorrhea and akathisia (although many authors do not recommend anticholinergics for this purpose2,3), and for prophylaxis of EPS. Benztropine can be administered intravenously, intramuscularly, or orally. Given orally, the typical dosing is twice daily with a maximum dose of 6 mg/d. Benztropine is preferred over diphenhydramine and trihexyphenidyl due to adverse effects of sedation or potential for misuse of the medication.1

Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) have been associated with lower rates of neurologic adverse effects compared with first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs). Because SGAs are increasingly prescribed, the use of benztropine (along with other agents such as trihexyphenidyl) for EPS prophylaxis is not an evidence-based practice. However, despite a movement away from prophylactic management of movement disorders, benztropine continues to be prescribed for EPS and/or cholinergic symptoms, despite the peripheral and cognitive adverse effects of this agent and, in many instances, the lack of clear indication for its use.

According to the most recent edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia,4 anticholinergics should only be used for preventing acute dystonia in conjunction with a long-acting injectable antipsychotic. Furthermore, the APA Guideline states anticholinergics may be used for drug-induced parkinsonism when the dose of an antipsychotic cannot be reduced and an alternative agent is required. However, the first-line agent for drug-induced parkinsonism is amantadine, and benztropine should only be considered if amantadine is contraindicated.4 The rationale for this guideline and for judicious use of anticholinergics is that like any pharmacologic treatment, anticholinergics (including benztropine) carry the potential for adverse effects. For benztropine, these range from mild effects such as tachycardia and constipation to paralytic ileus, increased falls, worsening of tardive dyskinesia (TD), and potential cognitive impairment. Literature suggests that the first step in managing cognitive concerns in a patient with schizophrenia should be a close review of medications, and avoidance of agents with anticholinergic properties.5

Prescribing benztropine for EPS

EPS, which include dystonia, akathisia, drug-induced parkinsonism, and TD, are very frequent adverse effects noted with antipsychotics. Benztropine has demonstrated benefit in managing acute dystonia and the APA Guideline recommends IM administration of either benztropine 1 mg or diphenhydramine 25 mg for this purpose.4 However, in our experience, the most frequent indication for long-term prescribing of benztropine is prophylaxis of antipsychoticinduced dystonia. This use was suggested by some older studies. In a 1987 study by Boyer et al,6 patients who were administered benztropine with haloperidol did not develop acute dystonia, while patients who received haloperidol alone developed dystonia. However, this was a small retrospective study with methodological issues. Boyer et al6 suggested discontinuing prophylaxis with benztropine within 1 week, as acute dystonia occurred within 2.5 days. Other researchers7,8 have argued that short-term prophylaxis with benztropine for 1 week may work, especially during treatment with high-potency antipsychotics. However, in a review of the use of anticholinergics in conjunction with antipsychotics, Desmarais et al5 concluded that there is no need for prophylaxis and recommended alternative treatments. As we have noticed in Ms. P and other patients treated in our facilities, benztropine is frequently continued indefinitely without a clinical indication for its continuous use. Assessment and indication for continued use of benztropine should be considered regularly, and it should be discontinued when there is no clear indication for its use or when adverse effects emerge.

Prescribing benztropine for TD

TD is a subtype of tardive syndromes associated with the use of antipsychotics. It is characterized by repetitive involuntary movements such as lip smacking, puckering, chewing, or tongue protrusion. Proposed pathophysiological mechanisms include dopamine receptor hypersensitivity, N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor excitotoxicity, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-containing neuron activity.

According to the APA Guideline, evidence of benztropine’s efficacy for the prevention of TD is lacking.4 A 2018 Cochrane systematic review9 was unable to provide a definitive conclusion regarding the effectiveness of benztropine and other anticholinergics for the treatment of antipsychotic-induced TD. While many clinicians believe that benztropine can be used to treat all types of EPS, there are no clear instances in reviewed literature where the efficacy of benztropine for treating TD could be reliably demonstrated. Furthermore, some literature suggests that anticholinergics such as benztropine increase the risk of developing TD.5,10 The mechanism underlying benztropine’s ability to precipitate or exacerbate abnormal movements is unclear, though it is theorized that anticholinergic medications may inhibit dopamine reuptake into neurons, thus leading to an excess of dopamine in the synaptic cleft that manifests as dyskinesias.10 Some authors also recommend that the first step in the management of TD should be to gradually discontinue anticholinergics, as this has been associated with improvement in TD.11

Continue to: Prescribing anticholinergics in specific patient populations...

Prescribing anticholinergics in specific patient populations

In addition to the adverse effects described above, benztropine can affect cognition, as we observed in Ms. P. The cholinergic system plays a role in human cognition, and blockade of muscarinic receptors has been associated with impairments in working memory and prefrontal tasks.12 These adverse cognitive effects are more pronounced in certain populations, including patients with schizophrenia and older adults.

Schizophrenia is associated with declining cognitive function, and the cognitive faculties of patients with schizophrenia may be worsened by anticholinergics. In patients with schizophrenia, social interactions and social integration are often impacted by profound negative symptoms such as social withdrawal and poverty of thought and speech.13 In a double-blind study by Baker et al,14 benztropine was found to have an impact on attention and concentration in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Baker et al14 found that patients with schizophrenia who were switched from benztropine to placebo increased their overall Wechsler Memory Scale scores compared to those maintained on benztropine. One crosssectional analysis found that a higher anticholinergic burden was associated with impairments across all cognitive domains, including memory, attention/control, executive and visuospatial functioning, and motor speed domains.15 Importantly, a higher anticholinergic medication burden was associated with worse cognitive performance.15 In addition to impairments in cognitive processing, anticholinergics have been associated with a decreased ability to benefit from psychosocial programs and impaired abilities to manage activities of daily living.4 In another study exploring the effects of discontinuing anticholinergics and the impact on movement disorders, Desmarais et al16 found patients experienced a significant improvement in scores on the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia after discontinuing anticholinergics. Vinogradov et al17 noted that “serum anticholinergic activity in schizophrenia patients shows a significant association with impaired performance in measures of verbal working memory and verbal learning memory and was significantly associated with a lowered response to an intensive course of computerized cognitive training.” They felt their findings underscored the cognitive cost of medications with high anticholinergic burden.

Geriatric patients. Careful consideration should be given before starting benztropine in patients age ≥65. The 2019 American Geriatric Society’s Beers Criteria18 recommend avoiding benztropine in geriatric patients; the level of recommendation is strong. Furthermore, the American Geriatric Society designates benztropine as a medication that should be avoided, and a nondrug approach or alternative medication be prescribed independent of the patient’s condition or diagnosis. In a recently published case report, Esang et al19 highlighted several salient findings from previous studies on the risks associated with anticholinergic use:

- any medications a patient takes with anticholinergic properties contribute to the overall anticholinergic load of a patient’s medication regimen

- the higher the anticholinergic burden, the greater the cognitive deficits

- switching from an FGA to an SGA may decrease the risk of EPS and may limit the need for anticholinergic medications such as benztropine for a particular patient.

One must also consider that the effects of multiple medications with anticholinergic properties is probably cumulative.

Alternatives for treating drug-induced parkinsonism

Antipsychotics exert their effects through antagonism of the D2 receptor, and this is the same mechanism that leads to parkinsonism. Specifically, the mechanism is believed to be D2 receptor antagonism in the striatum leading to disinhibition of striatal neurons containing GABA.11 This disinhibition of medium spiny neurons is propagated when acetylcholine is released from cholinergic interneurons. Anticholinergics such as benztropine can remedy symptoms by blocking the signal of acetylcholine on the M1 receptors on medium spiny neurons. However, benztropine also has the propensity to decrease cholinergic transmission, thereby impairing storage of new information into long-term memory as well as impair perception of time—similar to effects seen with (for instance) diphenhydramine.20

The first step in managing drug-induced parkinsonism is to monitor symptoms. The APA Guideline recommends monitoring for acute-onset EPS at weekly intervals when beginning treatment and until stable for 2 weeks, and then monitoring at every follow-up visit thereafter.4 The next recommendation for long-term management of drug-induced parkinsonism is reducing the antipsychotic dose, or replacing the patient’s antipsychotic with an antipsychotic that is less likely to precipitate parkinsonism,4 such as quetiapine, iloperidone, or clozapine.11 If dose reduction is not possible, and the patient’s symptoms are severe, pharmacologic management is indicated. The APA Guideline recommends amantadine as a first-line agent because it is associated with fewer peripheral adverse effects and less impairment in cognition compared with benztropine.4 In a small (N = 60) doubleblind crossover trial, Gelenberg et al20 found benztropine 4 mg/d—but not amantadine 200 mg/d—impaired free recall and perception of time, and participants’ perception of their own memory impairment was significantly greater with benztropine. Amantadine has also been compared to biperiden, a relatively selective M1 muscarinic receptor muscarinic agent. In a separate double-blind crossover study of 26 patients with chronic schizophrenia, Silver and Geraisy21 found that compared to amantadine, biperiden was associated with worse memory performance. The recommended starting dose of amantadine for parkinsonism is 100 mg in the morning, increased to 100 mg twice a day and titrated to a maximum daily dose of 300 mg/d in divided doses.4

Continue to: Alternatives for treating drug-induced akathisia...

Alternatives for treating drug-induced akathisia

Akathisia remains a relatively common adverse effect of SGAs, and the profound physical distress and impaired functioning caused by akathisia necessitates pharmacologic treatment. Despite frequent use in practice for presumed benefit in akathisia, benztropine is not effective for the treatment of akathisia and the APA Guideline recommends that long-term management should begin with an antipsychotic dose reduction, followed by a switch to an agent with less propensity to incite akathisia.4 Acute manifestations of akathisia must be treated, and mirtazapine, propranolol, or clonazepam may be considered as alternatives.4 Mirtazapine is dosed 7.5 mg to 10 mg nightly for akathisia, though it should be used in caution in patients at risk for mania.4 Mirtazapine’s potent 5-HT2A blockade at low doses may contribute to its utility in treating akathisia.2 Propranolol, a nonselective lipophilic beta-adrenergic antagonist, also has demonstrated efficacy in managing akathisia, with recommended dosing of 40 mg to 80 mg twice daily.2 Benzodiazepines such as clonazepam require judicious use for akathisia because they may also precipitate or exacerbate cognitive impairment.4

Alternatives for treating TD

As mentioned above, benztropine is not recommended for the treatment of TD.1 The Box4,22,23 outlines potential treatment options for TD.

Box

Monitoring is the first step in the prevention of tardive dyskinesia (TD). The American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia recommends patients receiving first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) be monitored every 6 months, those prescribed second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) be monitored every 12 months, and twice as frequent monitoring for geriatric patients and those who developed involuntary movements rapidly after starting an antipsychotic.4

The APA Guideline recommends decreasing or gradually tapering antipsychotics as another strategy for preventing TD.4 However, these recommendations should be weighed against the risk of short-term antipsychotic withdrawal. Withdrawal of D2 antagonists is associated with worsening of dyskinesias or withdrawal dyskinesia and psychotic decompensation.22

Current treatment recommendations give preference to the importance of preventing development of TD by tapering to the lowest dose of antipsychotic needed to control symptoms for the shortest duration possible.22 Thereafter, if treatment intervention is needed, consideration should be given to the following pharmacological interventions in order from highest level of recommendation (Grade A) to lowest (Grade C):

A: vesicular monoamine transporter-2 inhibitors deutetrabenazine and valbenazine

B: clonazepam, ginkgo biloba

C: amantadine, tetrabenazine, and globus pallidus interna deep brain stimulation.22

There is insufficient evidence to support or refute withdrawing causative agents or switching from FGAs to SGAs to treat TD.22 Furthermore, for many patients with schizophrenia, a gradual discontinuation of their antipsychotic must be weighed against the risk of relapse.23

Valbenazine and deutetrabenazine have been demonstrated to be efficacious and are FDA-approved for managing TD. The initial dose of valbenazine is 40 mg/d. Common adverse effects include somnolence and fatigue/ sedation. Valbenazine should be avoided in patients with QT prolongation or arrhythmias. Deutetrabenazine has less impact on the cytochrome P450 2D6 enzyme and therefore does not require genotyping as would be the case for patients who are receiving >50 mg/d of tetrabenazine. The starting dose of deutetrabenazine is 6 mg/d. Adverse effects include depression, suicidality, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, parkinsonism, and QT prolongation. Deutetrabenazine is contraindicated in patients who are suicidal or have untreated depression, hepatic impairment, or concomitant use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors.22 Deutetrabenazine is an isomer of tetrabenazine; however, evidence supporting the parent compound suggests limited use due to increased risk of adverse effects compared with valbenazine and deutetrabenazine.23 Tetrabenazine may be considered as an adjunctive treatment or used as a single agent if valbenazine or deutetrabenazine are not accessible.22

Discontinuing benztropine

Benztropine is recommended as a firstline agent for the management of acute dystonia, and it may be used temporarily for drug-induced parkinsonism, but it is not recommended to prevent EPS or TD. Given the multitude of adverse effects and cognitive impairment noted with anticholinergics, tapering should be considered for patients receiving an anticholinergic agent such as benztropine. Based on their review of earlier studies, Desmarais et al5 suggest a gradual 3-month discontinuation of benztropine. Multiple studies have demonstrated an ability to taper anticholinergics in days to months.4 However, gradual discontinuation is advisable to avoid cholinergic rebound and the reemergence of EPS, and to decrease the risk of neuroleptic malignant syndrome associated with sudden discontinuation.5 One suggested taper regimen is a decrease of 0.5 mg benztropine every week. Amantadine may be considered if parkinsonism is noted during the taper. Patients on benztropine may develop rebound symptoms, such as vivid dreams/nightmares; if this occurs, the taper rate can be slowed to a decrease of 0.5 mg every 2 weeks.4

Continue to: First do no harm...

First do no harm

Psychiatrists commonly prescribe benztropine to prevent EPS and TD, but available literature does not support the efficacy of benztropine for mitigating drug-induced parkinsonism, and studies report benztropine may significantly worsen cognitive processes and exacerbate TD.16 In addition, benztropine misuse has been correlated with euphoria and psychosis.16 More than 3 decades ago, the World Health Organization Heads of Centres Collaborating in WHO-Coordinated Studies on Biological Aspects of Mental Illness issued a consensus statement24 discouraging the prophylactic use of anticholinergics for patients receiving antipsychotics, yet we still see patients on an indefinite regimen of benztropine.

As clinicians, our goals should be to optimize a patient’s functioning and quality of life, and to use the lowest dose of medication along with the fewest medications necessary to avoid adverse effects such as EPS. Benztropine is recommended as a first-line agent for the management of acute dystonia, but its continued or indefinite use to prevent antipsychotic-induced adverse effects is not recommended. While all pharmacologic interventions carry a risk of adverse effects, weighing the risk of those effects against the clinical benefits is the prerogative of a skilled clinician. Benztropine and other anticholinergics prescribed for prophylactic purposes have numerous adverse effects, limited clinical utility, and a deleterious effect on quality of life. Furthermore, benztropine prophylaxis of drug-induced parkinsonism does not seem to be warranted, and the risks do not seem to outweigh the harm benztropine may cause, with the possible exception of “prophylactic” treatment of dystonia that is discontinued in a few days, as some researchers have suggested.6-8 The preventive value of benztropine has not been demonstrated. It is time we took inventory of medications that might cause more harm than good, rely on current treatment guidelines instead of habit, and use these agents judiciously while considering replacement with novel, safer medications whenever possible.

CASE CONTINUED

The clinical team considers benztropine’s ability to cause cognitive effects, and decides to taper and discontinue it over 1 month. Ms. P is seen in an outpatient clinic within 1 month of discontinuing benztropine. She reports that her difficulty remembering words and details has improved. She also says that she is now able to concentrate on writing and reading. The consulting neurologist also notes improvement. Ms. P continues to report improvement in symptoms over the next 2 months of follow-up, and says that her mood improved and she has less apathy.

Bottom Line

Benztropine is a first-line medication for acute dystonia, but its continued or indefinite use for preventing antipsychotic-induced adverse effects is not recommended. Given the multitude of adverse effects and cognitive impairment noted with anticholinergics, tapering should be considered for patients receiving an anticholinergic medication such as benztropine.

1. Cogentin [package insert]. McPherson, KS: Lundbeck Inc; 2013.

2. Poyurovsky M, Weizman A. Treatment of antipsychoticrelated akathisia revisited. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015; 35(6):711-714.

3. Salem H, Nagpal C, Pigott T, et al. Revisiting antipsychoticinduced akathisia: current issues and prospective challenges. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15(5):789-798.

4. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2021.

5. Desmarais JE, Beauclair L, Margolese HC. Anticholinergics in the era of atypical antipsychotics: short-term or long-term treatment? J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26(9):1167-1174.

6. Boyer WF, Bakalar NH, Lake CR. Anticholinergic prophylaxis of acute haloperidol-induced acute dystonic reactions. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1987;7(3):164-166.

7. Winslow RS, Stillner V, Coons DJ, et al. Prevention of acute dystonic reactions in patients beginning high-potency neuroleptics. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(6):706-710.

8. Stern TA, Anderson WH. Benztropine prophylaxis of dystonic reactions. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1979; 61(3):261-262.

9. Bergman H, Soares‐Weiser K. Anticholinergic medication for antipsychotic‐induced tardive dyskinesia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1(1):CD000204. doi:10.1002/ 14651858.CD000204.pub2

10. Howrie DL, Rowley AH, Krenzelok EP. Benztropineinduced acute dystonic reaction. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15(5):594-596.

11. Ward KM, Citrome L. Antipsychotic-related movement disorders: drug-induced parkinsonism vs. tardive dyskinesia--key differences in pathophysiology and clinical management. Neurol Ther. 2018;7(2): 233-248.

12. Wijegunaratne H, Qazi H, Koola M. Chronic and bedtime use of benztropine with antipsychotics: is it necessary? Schizophr Res. 2014;153(1-3):248-249.

13. Möller HJ. The relevance of negative symptoms in schizophrenia and how to treat them with psychopharmaceuticals? Psychiatr Danub. 2016;28(4):435-440.

14. Baker LA, Cheng LY, Amara IB. The withdrawal of benztropine mesylate in chronic schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1983;143:584-590.

15. Joshi YB, Thomas ML, Braff DL, et al. Anticholinergic medication burden-associated cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178(9):838-847.

16. Desmarais JE, Beauclair E, Annable L, et al. Effects of discontinuing anticholinergic treatment on movement disorders, cognition and psychopathology in patients with schizophrenia. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(6): 257-267.

17. Vinogradov S, Fisher M, Warm H, et al. The cognitive cost of anticholinergic burden: decreased response to cognitive training in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9): 1055-1062.

18. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674-694.

19. Esang M, Person US, Izekor OO, et al. An unlikely case of benztropine misuse in an elderly schizophrenic. Cureus. 2021;13(2):e13434. doi:10.7759/cureus.13434

20. Gelenberg AJ, Van Putten T, Lavori PW, et al. Anticholinergic effects on memory: benztropine versus amantadine. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1989;9(3):180-185.

21. Silver H, Geraisy N. Effects of biperiden and amantadine on memory in medicated chronic schizophrenic patients. A double-blind cross-over study. Br J Psychiatry. 1995; 166(2):241-243.

22. Bhidayasiri R, Jitkritsadakul O, Friedman J, et al. Updating the recommendations for treatment of tardive syndromes: a systematic review of new evidence and practical treatment algorithm. J Neurol Sci. 2018;389:67-75.

23. Ricciardi L, Pringsheim T, Barnes TRE, et al. Treatment recommendations for tardive dyskinesia. Canadian J Psychiatry. 2019;64(6):388-399.

24. Prophylactic use of anticholinergics in patients on long-term neuroleptic treatment. A consensus statement. World Health Organization heads of centres collaborating in WHO coordinated studies on biological aspects of mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;156:412.

1. Cogentin [package insert]. McPherson, KS: Lundbeck Inc; 2013.

2. Poyurovsky M, Weizman A. Treatment of antipsychoticrelated akathisia revisited. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015; 35(6):711-714.

3. Salem H, Nagpal C, Pigott T, et al. Revisiting antipsychoticinduced akathisia: current issues and prospective challenges. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15(5):789-798.

4. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2021.

5. Desmarais JE, Beauclair L, Margolese HC. Anticholinergics in the era of atypical antipsychotics: short-term or long-term treatment? J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26(9):1167-1174.

6. Boyer WF, Bakalar NH, Lake CR. Anticholinergic prophylaxis of acute haloperidol-induced acute dystonic reactions. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1987;7(3):164-166.

7. Winslow RS, Stillner V, Coons DJ, et al. Prevention of acute dystonic reactions in patients beginning high-potency neuroleptics. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(6):706-710.

8. Stern TA, Anderson WH. Benztropine prophylaxis of dystonic reactions. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1979; 61(3):261-262.

9. Bergman H, Soares‐Weiser K. Anticholinergic medication for antipsychotic‐induced tardive dyskinesia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1(1):CD000204. doi:10.1002/ 14651858.CD000204.pub2

10. Howrie DL, Rowley AH, Krenzelok EP. Benztropineinduced acute dystonic reaction. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15(5):594-596.

11. Ward KM, Citrome L. Antipsychotic-related movement disorders: drug-induced parkinsonism vs. tardive dyskinesia--key differences in pathophysiology and clinical management. Neurol Ther. 2018;7(2): 233-248.

12. Wijegunaratne H, Qazi H, Koola M. Chronic and bedtime use of benztropine with antipsychotics: is it necessary? Schizophr Res. 2014;153(1-3):248-249.

13. Möller HJ. The relevance of negative symptoms in schizophrenia and how to treat them with psychopharmaceuticals? Psychiatr Danub. 2016;28(4):435-440.

14. Baker LA, Cheng LY, Amara IB. The withdrawal of benztropine mesylate in chronic schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1983;143:584-590.

15. Joshi YB, Thomas ML, Braff DL, et al. Anticholinergic medication burden-associated cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178(9):838-847.

16. Desmarais JE, Beauclair E, Annable L, et al. Effects of discontinuing anticholinergic treatment on movement disorders, cognition and psychopathology in patients with schizophrenia. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(6): 257-267.

17. Vinogradov S, Fisher M, Warm H, et al. The cognitive cost of anticholinergic burden: decreased response to cognitive training in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9): 1055-1062.