User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Managing schizophrenia in a patient with cancer: A fine balance

CASE Stable with a new diagnosis

Ms. B, age 60, has a history of schizophrenia, which has been stable on clozapine, 500 mg/d, for more than 2 decades. After a series of hospitalizations in her 20s and 30s, clozapine was initiated and she has not required additional inpatient psychiatric care. She has been managed in the outpatient setting with standard biweekly absolute neutrophil count (ANC) monitoring. She lives independently and is an active member in her church.

After experiencing rectal bleeding, Ms. B is diagnosed with rectal carcinoma and is scheduled to undergo chemotherapy and radiation treatment.

[polldaddy:9754786]

The authors’ observations

Both clozapine and chemotherapy carry the risk of immunosuppression, presenting a clinical challenge when choosing an appropriate management strategy. However, the risks of stopping clozapine after a long period of symptom stability are substantial, with a relapse rate up to 50%.1 Among patients taking clozapine, the risk of agranulocytosis and neutropenia are approximately 0.8% and 3%, respectively, and >80% of agranulocyotis cases occur within the first 18 weeks of treatment.2,3 Although both clozapine and chemotherapy can lead to neutropenia and agranulocytosis, there currently is no evidence of a synergistic effect on bone marrow suppression with simultaneous use of these therapies2 nor is there evidence of the combination leading to sustained marrow suppression.4

Because of Ms. B’s positive response to clozapine, the risks associated with discontinuing the medication, and the relatively low risk of clozapine contributing to neutropenia after a long period of stabilization, her outpatient psychiatric providers decide to increase ANC monitoring to weekly while she undergoes cancer treatment.

TREATMENT Neutropenia, psychosis

Ms. B continues clozapine during radiation and chemotherapy, but develops leukopenia and neutropenia with a low of 1,220/μL white blood cells and an ANC of 610/μL. Clozapine is stopped, consistent with current recommendations to hold the drug if the neutrophil count is <1,000/μL in a patient without benign ethnic neutropenia, and her outpatient provider monitors her closely. The treatment team does not restart an antipsychotic immediately after discontinuing clozapine because of the risk that other antipsychotics can cause hematologic toxicity or prolong granulocytopenia associated with clozapine.5

Approximately 2 weeks later, Ms. B is admitted to a different hospital for altered mental status and is found to have hyponatremia and rectal bleeding. The workup suggests that her rectal carcinoma has not fully responded to initial therapies, and she likely will require further treatment. Her mental status improves after hyponatremia resolves, but she reports auditory hallucinations and paranoia. Risperidone, 4 mg/d, is initiated to target psychosis.

After discharge, Ms. B develops bilateral upper extremity tremor, which she finds intolerable and attributes to risperidone. She refuses to continue risperidone or try adjunctive medications to address the tremor, but is willing to consider a different antipsychotic. Olanzapine, 10 mg/d, is initiated and risperidone is slowly tapered. During this time, Ms. B experiences increased paranoia and believes that the Internal Revenue Service is calling her. She misses her next appointment.

Later, the fire department finds Ms. B wandering the streets and brings her to the psychiatric emergency room. During the examination, she is disheveled and withdrawn, and unable to reply to simple questions about diet and sleep. When asked why she was in the street, she says that she left her apartment because it was “too messy.” The treatment team learns that she had walked at least 10 miles from her apartment before sitting down by the side of the road and being picked up by the fire department. She reveals that she left her apartment and continued walking because “a man” told her to do so and threatened to harm her if she stopped.

When Ms. B is admitted to the psychiatric service, she is paranoid, disorganized, and guarded. She remains in her room for most of the day and either refuses to talk to providers or curses at them. She often is seen wearing soiled clothing with her hair mussed. She denies having rectal carcinoma, although she expressed understanding of her medical condition <2 months earlier.

[polldaddy:9754787]

The authors’ observations

Clozapine is considered the most efficacious agent for treatment-resistant schizophrenia.6 Although non-compliance is the most common reason for discontinuing clozapine, >20% of patients stop clozapine because of adverse effects.7 Clozapine often is a drug of last resort because of the need for frequent monitoring and significant side effects; therefore deciding on a next step when clozapine fails or cannot be continued because of other factors can pose a challenge.

Ms. B’s treatment team gave serious consideration to restarting clozapine. However, because it was likely that Ms. B would undergo another round of chemotherapy and possibly radiation, the risk of neutropenia recurring was considered too high. Lithium has been used successfully to manage neutropenia in patients taking clozapine and, for some, adding lithium could help boost white cell count and allow a successful rechallenge with clozapine.3,8 However, because of Ms. B’s medical comorbidities, including cancer and chronic kidney disease, adding lithium was not thought to be clinically prudent at that time and the treatment team considered other options.

Olanzapine. Although research is limited, studies suggest olanzapine is the most commonly prescribed medication when a patient has to discontinue clozapine,7 with comparable response rates in those with refractory schizophrenia.9 Therefore, Ms. B was initially maintained on olanzapine, and the dosage increased to 30 mg over the course of 16 days in the hospital. However, she did not respond to the medication, remaining disorganized and paranoid without any notable improvement in her symptoms therefore other treatment options were explored.

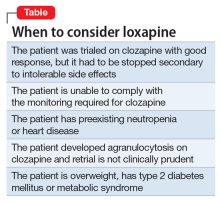

Loxapine. Previous limited case reports have shown loxapine to be effective in treating individuals with refractory schizophrenia, either alone or in combination with other antipsychotics.10,11 FDA-approved in 1975, loxapine was among the last of the typical antipsychotics brought to the U.S. market before the introduction of clozapine, the first atypical.12 Loxapine is a dibenzoxazepine that has a molecular structure similar to clozapine.13 Unlike clozapine, however, loxapine is not known to cause agranulocytosis.14 Research suggests that although clozapine is oxidized to metabolites that are cytotoxic, loxapine is not, potentially accounting for their different effects on neutrophils.15

The efficacy of loxapine has shown to be similar to other typical and atypical antipsychotics, with approximately 70% of patients showing improvement.14 However, loxapine may be overlooked as an option, possibly because it was not included in the CATIE trial and was the last typical antipsychotic to be approved before atypicals were introduced.12 First available in oral and IM formulations, there has been increased interest in loxapine recently because of the approval of an inhaled formulation in 2012.16

Although classified as a typical antipsychotic, studies have suggested that loxapine acts as an atypical at low dosages.17,18 Previous work suggests, however, that the side effect profile of loxapine is similar to typical antipsychotics.14 At dosages <50 mg, it results in fewer cases of extrapyramidal side effects than expected with a typical antipsychotic.18

Loxapine’s binding profile seems to exist along this spectrum of typical to atypical. Tissue-based binding studies have shown a higher 5-HT2 affinity relative to D2, consistent with atypical antipsychotics.19 Positron emission tomography studies in humans show 5-HT2 saturation of loxapine to be close to equal to D2 binding in loxapine, thus a slightly lower ratio of 5-HT2 to D2 relative to atypicals, but more than that seen with typical antipsychotics.20 These differences between in vitro and in vivo studies may be secondary to the binding of loxapine’s active metabolites, particularly 7- and 8-hydroxyloxapine, which have more dopaminergic activity. In addition to increased 5-HT2A binding compared with typical antipsychotics, loxapine also has a high affinity for the D4 receptors, as well as interacting with other serotonin receptors 5-HT3, 5-HT6, and 5-HT7. Of note this is a similar pattern of binding affinity as seen in clozapine.19

It should be noted, however, that loxapine may not be an appropriate treatment in all forms of cancer. Similar to other first-generation antipsychotics, it increases prolactin levels, and thus may have a negative clinical impact on patients with prolactin receptor positive breast cancers.21,22 Finally, although clozapine can result in significant weight gain, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia, unlike many antipsychotics, loxapine has been shown to be weight neutral or result in weight loss,14 making it an option to consider for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia, or cardiovascular disease.

OUTCOME Improvement, stability

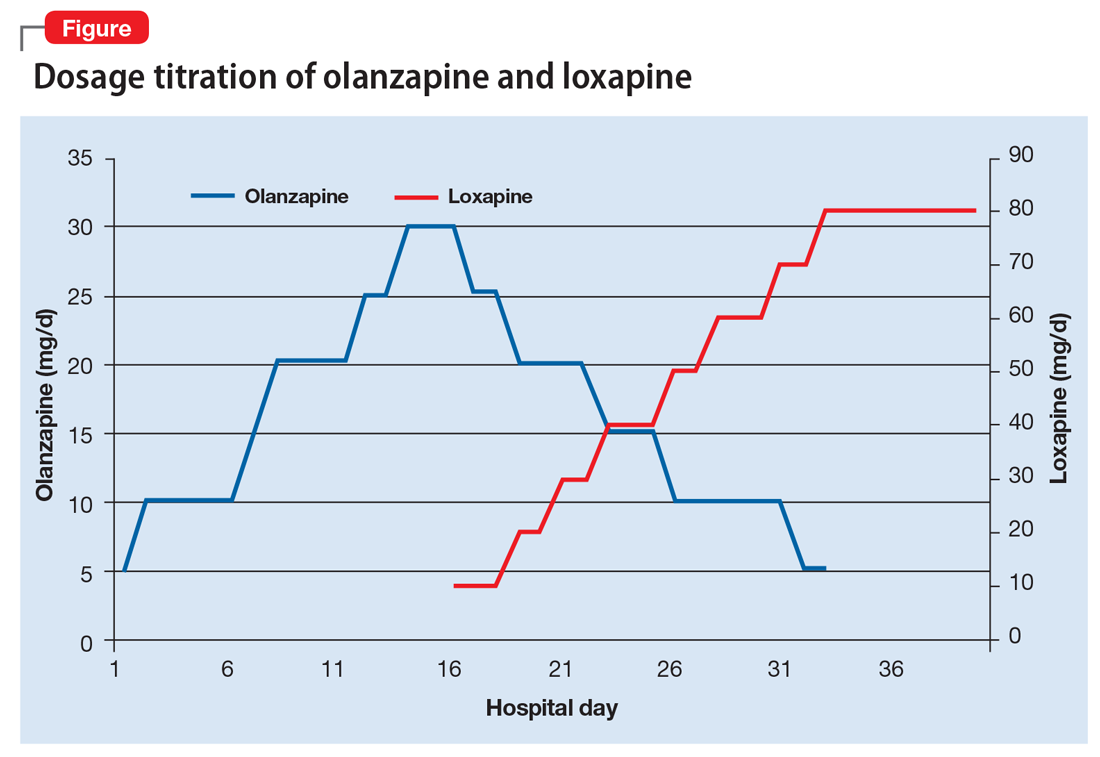

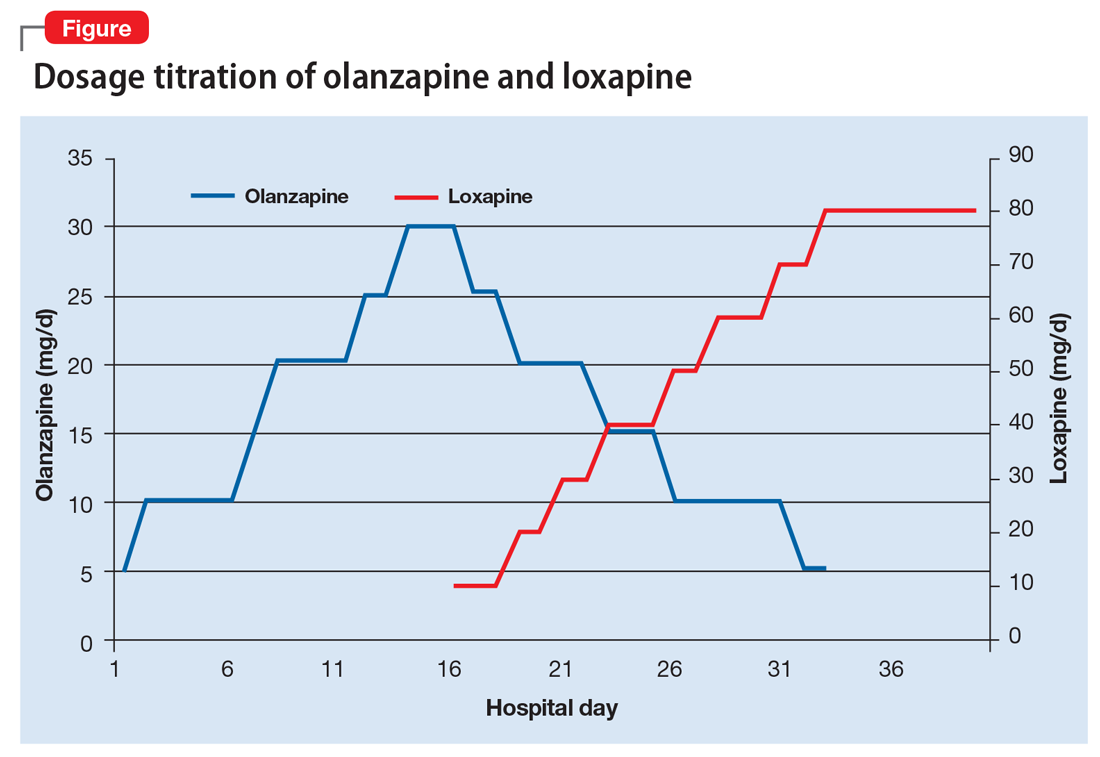

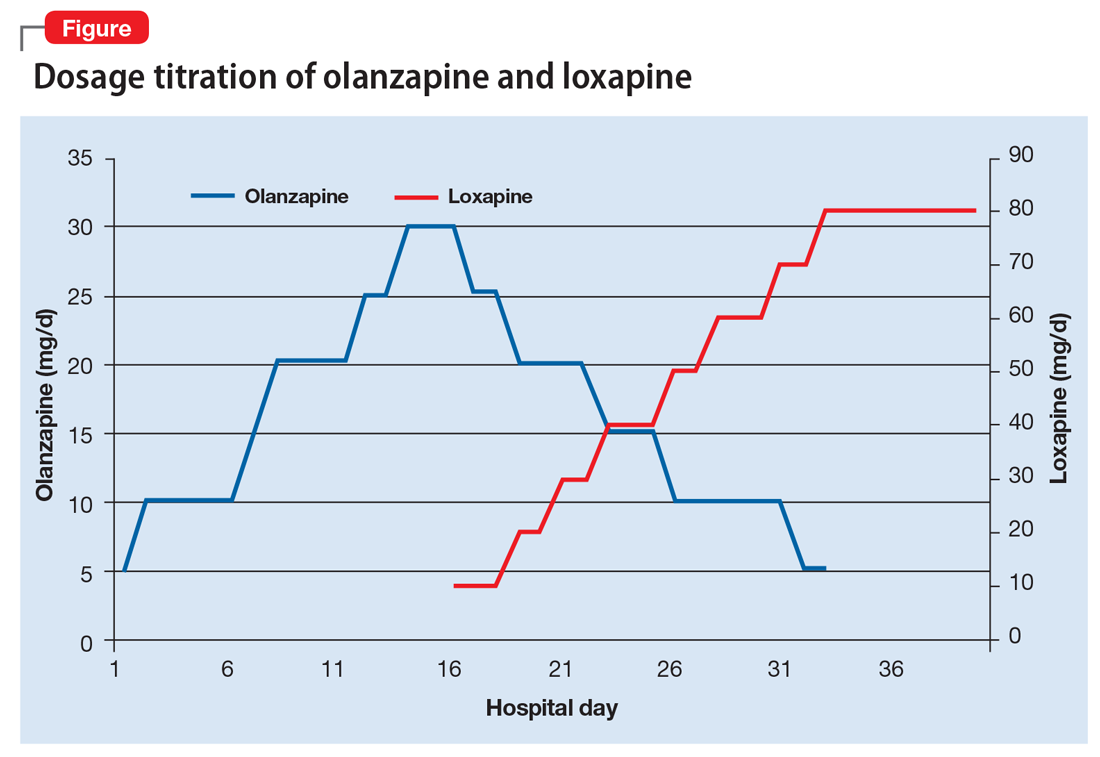

Ms. B begins taking loxapine, 10 mg/d, gradually cross-tapered with olanzapine, increasing loxapine by 10 mg every 2 to 3 days (Figure). After 8 days, when the dosage has reached 40 mg/d, Ms. B’s treatment team begins to observe a consistent change in her behavior. Ms. B comes into the interview room, where previously the team had to see her in her own room because she refused to come out. She also tolerates an extensive interview, even sharing parts of her history without prompting, and is able to discuss her treatment. Ms. B continues to express some paranoia regarding the treatment team. On day 12, receiving loxapine, 50 mg/d, Ms. B says that she likes the new medication and feels she is doing well with it. She becomes less reclusive and begins socializing with other patients. By day 19, receiving loxapine, 80 mg/d, a nurse, who knows Ms. B from the outpatient facility, visits the unit and reports that Ms. B is at her baseline.

At discharge, Ms. B is noted to be “bright,” well organized, neatly dressed, and wearing makeup. Her paranoia and auditory hallucinations have almost completely resolved. She is social, engages appropriately with the treatment team, and is able to describe a plan for self-care after discharge including following up with her oncologist. Her white blood cell counts were carefully monitored throughout her admission and are within normal limits when she is discharged.

One year later, Ms. B remains taking loxapine, 70 mg/d. Although she continues to report mild paranoia, she is living independently in her apartment and attends church regularly.

2. Usta NG, Poyraz CA, Aktan M, et al. Clozapine treatment of refractory schizophrenia during essential chemotherapy: a case study and mini review of a clinical dilemma. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(6):276-281.

3. Meyer N, Gee S, Whiskey E, et al. Optimizing outcomes in clozapine rechallenge following neutropenia: a cohort analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(11):e1410-e1416.

4. Cunningham NT, Dennis N, Dattilo W, et al. Continuation of clozapine during chemotherapy: a case report and review of literature. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(6):673-679.

5. Co¸sar B, Taner ME, Eser HY, et al. Does switching to another antipsychotic in patients with clozapine-associated granulocytopenia solve the problem? Case series of 18. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(2):169-173.

6. McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, et al; CATIE Investigation. Effectiveness of clozapine versus olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia who did not respond to prior atypical antipsychotic treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):600-610.

7. Mustafa FA, Burke JG, Abukmeil SS, et al. “Schizophrenia past clozapine”: reasons for clozapine discontinuation, mortality, and alternative antipsychotic prescribing. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2015;48(1):11-14.

8. Aydin M, Ilhan BC, Calisir S, et al. Continuing clozapine treatment with lithium in schizophrenic patients with neutropenia or leukopenia: brief review of literature with case reports. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2016;6(1):33-38.

9. Bitter I, Dossenbach MR, Brook S, et al; Olanzapine HGCK Study Group. Olanzapine versus clozapine in treatment-resistant or treatment-intolerant schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28(1):173-180.

10. Lehmann CR, Ereshefsky L, Saklad SR, et al. Very high dose loxapine in refractory schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138(9):1212-1214.

11. Sokolski KN. Combination loxapine and aripiprazole for refractory hallucinations in schizophrenia. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(7-8):e36.

12. Shen WW. A history of antipsychotic drug development. Compr Psychiatry. 1999;40(6):407-414.

13. Mazzola CD, Miron S, Jenkins AJ. Loxapine intoxication: case report and literature review. J Anal Toxicol. 2000;24(7):638-641.

14. Chakrabarti A, Bagnall A, Chue P, et al. Loxapine for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007(4):CD001943.

15. Jegouzo A, Gressier B, Frimat B, et al. Comparative oxidation of loxapine and clozapine by human neutrophils. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1999;13(1):113-119.

16. Keating GM. Loxapine inhalation powder: a review of its use in the acute treatment of agitation in patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(6):479-489.

1 7. Glazer WM. Does loxapine have “atypical” properties? Clinical evidence. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 10):42-46.

18. Hellings JA, Jadhav M, Jain S, et al. Low dose loxapine: neuromotor side effects and tolerability in autism spectrum disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2015;25(8):618-624.

19. Singh AN, Barlas C, Singh S, et al. A neurochemical basis for the antipsychotic activity of loxapine: interactions with dopamine D1, D2, D4 and serotonin 5-HT2 receptor subtypes. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1996;21(1):29-35.

20. Kapur S, Zipursky RB, Remington G. Clinical and theoretical implications of 5-HT2 and D2 receptor occupancy of clozapine, risperidone, and olanzapine in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(2):286-293.

21. Robertson AG, Berry R, Meltzer HY. Prolactin stimulating effects of amoxapine and loxapine in psychiatric patients. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1982;78(3):287-292.

22. Rahman T, Clevenger CV, Kaklamani V, et al. Antipsychotic treatment in breast cancer patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(6):616-621.

CASE Stable with a new diagnosis

Ms. B, age 60, has a history of schizophrenia, which has been stable on clozapine, 500 mg/d, for more than 2 decades. After a series of hospitalizations in her 20s and 30s, clozapine was initiated and she has not required additional inpatient psychiatric care. She has been managed in the outpatient setting with standard biweekly absolute neutrophil count (ANC) monitoring. She lives independently and is an active member in her church.

After experiencing rectal bleeding, Ms. B is diagnosed with rectal carcinoma and is scheduled to undergo chemotherapy and radiation treatment.

[polldaddy:9754786]

The authors’ observations

Both clozapine and chemotherapy carry the risk of immunosuppression, presenting a clinical challenge when choosing an appropriate management strategy. However, the risks of stopping clozapine after a long period of symptom stability are substantial, with a relapse rate up to 50%.1 Among patients taking clozapine, the risk of agranulocytosis and neutropenia are approximately 0.8% and 3%, respectively, and >80% of agranulocyotis cases occur within the first 18 weeks of treatment.2,3 Although both clozapine and chemotherapy can lead to neutropenia and agranulocytosis, there currently is no evidence of a synergistic effect on bone marrow suppression with simultaneous use of these therapies2 nor is there evidence of the combination leading to sustained marrow suppression.4

Because of Ms. B’s positive response to clozapine, the risks associated with discontinuing the medication, and the relatively low risk of clozapine contributing to neutropenia after a long period of stabilization, her outpatient psychiatric providers decide to increase ANC monitoring to weekly while she undergoes cancer treatment.

TREATMENT Neutropenia, psychosis

Ms. B continues clozapine during radiation and chemotherapy, but develops leukopenia and neutropenia with a low of 1,220/μL white blood cells and an ANC of 610/μL. Clozapine is stopped, consistent with current recommendations to hold the drug if the neutrophil count is <1,000/μL in a patient without benign ethnic neutropenia, and her outpatient provider monitors her closely. The treatment team does not restart an antipsychotic immediately after discontinuing clozapine because of the risk that other antipsychotics can cause hematologic toxicity or prolong granulocytopenia associated with clozapine.5

Approximately 2 weeks later, Ms. B is admitted to a different hospital for altered mental status and is found to have hyponatremia and rectal bleeding. The workup suggests that her rectal carcinoma has not fully responded to initial therapies, and she likely will require further treatment. Her mental status improves after hyponatremia resolves, but she reports auditory hallucinations and paranoia. Risperidone, 4 mg/d, is initiated to target psychosis.

After discharge, Ms. B develops bilateral upper extremity tremor, which she finds intolerable and attributes to risperidone. She refuses to continue risperidone or try adjunctive medications to address the tremor, but is willing to consider a different antipsychotic. Olanzapine, 10 mg/d, is initiated and risperidone is slowly tapered. During this time, Ms. B experiences increased paranoia and believes that the Internal Revenue Service is calling her. She misses her next appointment.

Later, the fire department finds Ms. B wandering the streets and brings her to the psychiatric emergency room. During the examination, she is disheveled and withdrawn, and unable to reply to simple questions about diet and sleep. When asked why she was in the street, she says that she left her apartment because it was “too messy.” The treatment team learns that she had walked at least 10 miles from her apartment before sitting down by the side of the road and being picked up by the fire department. She reveals that she left her apartment and continued walking because “a man” told her to do so and threatened to harm her if she stopped.

When Ms. B is admitted to the psychiatric service, she is paranoid, disorganized, and guarded. She remains in her room for most of the day and either refuses to talk to providers or curses at them. She often is seen wearing soiled clothing with her hair mussed. She denies having rectal carcinoma, although she expressed understanding of her medical condition <2 months earlier.

[polldaddy:9754787]

The authors’ observations

Clozapine is considered the most efficacious agent for treatment-resistant schizophrenia.6 Although non-compliance is the most common reason for discontinuing clozapine, >20% of patients stop clozapine because of adverse effects.7 Clozapine often is a drug of last resort because of the need for frequent monitoring and significant side effects; therefore deciding on a next step when clozapine fails or cannot be continued because of other factors can pose a challenge.

Ms. B’s treatment team gave serious consideration to restarting clozapine. However, because it was likely that Ms. B would undergo another round of chemotherapy and possibly radiation, the risk of neutropenia recurring was considered too high. Lithium has been used successfully to manage neutropenia in patients taking clozapine and, for some, adding lithium could help boost white cell count and allow a successful rechallenge with clozapine.3,8 However, because of Ms. B’s medical comorbidities, including cancer and chronic kidney disease, adding lithium was not thought to be clinically prudent at that time and the treatment team considered other options.

Olanzapine. Although research is limited, studies suggest olanzapine is the most commonly prescribed medication when a patient has to discontinue clozapine,7 with comparable response rates in those with refractory schizophrenia.9 Therefore, Ms. B was initially maintained on olanzapine, and the dosage increased to 30 mg over the course of 16 days in the hospital. However, she did not respond to the medication, remaining disorganized and paranoid without any notable improvement in her symptoms therefore other treatment options were explored.

Loxapine. Previous limited case reports have shown loxapine to be effective in treating individuals with refractory schizophrenia, either alone or in combination with other antipsychotics.10,11 FDA-approved in 1975, loxapine was among the last of the typical antipsychotics brought to the U.S. market before the introduction of clozapine, the first atypical.12 Loxapine is a dibenzoxazepine that has a molecular structure similar to clozapine.13 Unlike clozapine, however, loxapine is not known to cause agranulocytosis.14 Research suggests that although clozapine is oxidized to metabolites that are cytotoxic, loxapine is not, potentially accounting for their different effects on neutrophils.15

The efficacy of loxapine has shown to be similar to other typical and atypical antipsychotics, with approximately 70% of patients showing improvement.14 However, loxapine may be overlooked as an option, possibly because it was not included in the CATIE trial and was the last typical antipsychotic to be approved before atypicals were introduced.12 First available in oral and IM formulations, there has been increased interest in loxapine recently because of the approval of an inhaled formulation in 2012.16

Although classified as a typical antipsychotic, studies have suggested that loxapine acts as an atypical at low dosages.17,18 Previous work suggests, however, that the side effect profile of loxapine is similar to typical antipsychotics.14 At dosages <50 mg, it results in fewer cases of extrapyramidal side effects than expected with a typical antipsychotic.18

Loxapine’s binding profile seems to exist along this spectrum of typical to atypical. Tissue-based binding studies have shown a higher 5-HT2 affinity relative to D2, consistent with atypical antipsychotics.19 Positron emission tomography studies in humans show 5-HT2 saturation of loxapine to be close to equal to D2 binding in loxapine, thus a slightly lower ratio of 5-HT2 to D2 relative to atypicals, but more than that seen with typical antipsychotics.20 These differences between in vitro and in vivo studies may be secondary to the binding of loxapine’s active metabolites, particularly 7- and 8-hydroxyloxapine, which have more dopaminergic activity. In addition to increased 5-HT2A binding compared with typical antipsychotics, loxapine also has a high affinity for the D4 receptors, as well as interacting with other serotonin receptors 5-HT3, 5-HT6, and 5-HT7. Of note this is a similar pattern of binding affinity as seen in clozapine.19

It should be noted, however, that loxapine may not be an appropriate treatment in all forms of cancer. Similar to other first-generation antipsychotics, it increases prolactin levels, and thus may have a negative clinical impact on patients with prolactin receptor positive breast cancers.21,22 Finally, although clozapine can result in significant weight gain, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia, unlike many antipsychotics, loxapine has been shown to be weight neutral or result in weight loss,14 making it an option to consider for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia, or cardiovascular disease.

OUTCOME Improvement, stability

Ms. B begins taking loxapine, 10 mg/d, gradually cross-tapered with olanzapine, increasing loxapine by 10 mg every 2 to 3 days (Figure). After 8 days, when the dosage has reached 40 mg/d, Ms. B’s treatment team begins to observe a consistent change in her behavior. Ms. B comes into the interview room, where previously the team had to see her in her own room because she refused to come out. She also tolerates an extensive interview, even sharing parts of her history without prompting, and is able to discuss her treatment. Ms. B continues to express some paranoia regarding the treatment team. On day 12, receiving loxapine, 50 mg/d, Ms. B says that she likes the new medication and feels she is doing well with it. She becomes less reclusive and begins socializing with other patients. By day 19, receiving loxapine, 80 mg/d, a nurse, who knows Ms. B from the outpatient facility, visits the unit and reports that Ms. B is at her baseline.

At discharge, Ms. B is noted to be “bright,” well organized, neatly dressed, and wearing makeup. Her paranoia and auditory hallucinations have almost completely resolved. She is social, engages appropriately with the treatment team, and is able to describe a plan for self-care after discharge including following up with her oncologist. Her white blood cell counts were carefully monitored throughout her admission and are within normal limits when she is discharged.

One year later, Ms. B remains taking loxapine, 70 mg/d. Although she continues to report mild paranoia, she is living independently in her apartment and attends church regularly.

CASE Stable with a new diagnosis

Ms. B, age 60, has a history of schizophrenia, which has been stable on clozapine, 500 mg/d, for more than 2 decades. After a series of hospitalizations in her 20s and 30s, clozapine was initiated and she has not required additional inpatient psychiatric care. She has been managed in the outpatient setting with standard biweekly absolute neutrophil count (ANC) monitoring. She lives independently and is an active member in her church.

After experiencing rectal bleeding, Ms. B is diagnosed with rectal carcinoma and is scheduled to undergo chemotherapy and radiation treatment.

[polldaddy:9754786]

The authors’ observations

Both clozapine and chemotherapy carry the risk of immunosuppression, presenting a clinical challenge when choosing an appropriate management strategy. However, the risks of stopping clozapine after a long period of symptom stability are substantial, with a relapse rate up to 50%.1 Among patients taking clozapine, the risk of agranulocytosis and neutropenia are approximately 0.8% and 3%, respectively, and >80% of agranulocyotis cases occur within the first 18 weeks of treatment.2,3 Although both clozapine and chemotherapy can lead to neutropenia and agranulocytosis, there currently is no evidence of a synergistic effect on bone marrow suppression with simultaneous use of these therapies2 nor is there evidence of the combination leading to sustained marrow suppression.4

Because of Ms. B’s positive response to clozapine, the risks associated with discontinuing the medication, and the relatively low risk of clozapine contributing to neutropenia after a long period of stabilization, her outpatient psychiatric providers decide to increase ANC monitoring to weekly while she undergoes cancer treatment.

TREATMENT Neutropenia, psychosis

Ms. B continues clozapine during radiation and chemotherapy, but develops leukopenia and neutropenia with a low of 1,220/μL white blood cells and an ANC of 610/μL. Clozapine is stopped, consistent with current recommendations to hold the drug if the neutrophil count is <1,000/μL in a patient without benign ethnic neutropenia, and her outpatient provider monitors her closely. The treatment team does not restart an antipsychotic immediately after discontinuing clozapine because of the risk that other antipsychotics can cause hematologic toxicity or prolong granulocytopenia associated with clozapine.5

Approximately 2 weeks later, Ms. B is admitted to a different hospital for altered mental status and is found to have hyponatremia and rectal bleeding. The workup suggests that her rectal carcinoma has not fully responded to initial therapies, and she likely will require further treatment. Her mental status improves after hyponatremia resolves, but she reports auditory hallucinations and paranoia. Risperidone, 4 mg/d, is initiated to target psychosis.

After discharge, Ms. B develops bilateral upper extremity tremor, which she finds intolerable and attributes to risperidone. She refuses to continue risperidone or try adjunctive medications to address the tremor, but is willing to consider a different antipsychotic. Olanzapine, 10 mg/d, is initiated and risperidone is slowly tapered. During this time, Ms. B experiences increased paranoia and believes that the Internal Revenue Service is calling her. She misses her next appointment.

Later, the fire department finds Ms. B wandering the streets and brings her to the psychiatric emergency room. During the examination, she is disheveled and withdrawn, and unable to reply to simple questions about diet and sleep. When asked why she was in the street, she says that she left her apartment because it was “too messy.” The treatment team learns that she had walked at least 10 miles from her apartment before sitting down by the side of the road and being picked up by the fire department. She reveals that she left her apartment and continued walking because “a man” told her to do so and threatened to harm her if she stopped.

When Ms. B is admitted to the psychiatric service, she is paranoid, disorganized, and guarded. She remains in her room for most of the day and either refuses to talk to providers or curses at them. She often is seen wearing soiled clothing with her hair mussed. She denies having rectal carcinoma, although she expressed understanding of her medical condition <2 months earlier.

[polldaddy:9754787]

The authors’ observations

Clozapine is considered the most efficacious agent for treatment-resistant schizophrenia.6 Although non-compliance is the most common reason for discontinuing clozapine, >20% of patients stop clozapine because of adverse effects.7 Clozapine often is a drug of last resort because of the need for frequent monitoring and significant side effects; therefore deciding on a next step when clozapine fails or cannot be continued because of other factors can pose a challenge.

Ms. B’s treatment team gave serious consideration to restarting clozapine. However, because it was likely that Ms. B would undergo another round of chemotherapy and possibly radiation, the risk of neutropenia recurring was considered too high. Lithium has been used successfully to manage neutropenia in patients taking clozapine and, for some, adding lithium could help boost white cell count and allow a successful rechallenge with clozapine.3,8 However, because of Ms. B’s medical comorbidities, including cancer and chronic kidney disease, adding lithium was not thought to be clinically prudent at that time and the treatment team considered other options.

Olanzapine. Although research is limited, studies suggest olanzapine is the most commonly prescribed medication when a patient has to discontinue clozapine,7 with comparable response rates in those with refractory schizophrenia.9 Therefore, Ms. B was initially maintained on olanzapine, and the dosage increased to 30 mg over the course of 16 days in the hospital. However, she did not respond to the medication, remaining disorganized and paranoid without any notable improvement in her symptoms therefore other treatment options were explored.

Loxapine. Previous limited case reports have shown loxapine to be effective in treating individuals with refractory schizophrenia, either alone or in combination with other antipsychotics.10,11 FDA-approved in 1975, loxapine was among the last of the typical antipsychotics brought to the U.S. market before the introduction of clozapine, the first atypical.12 Loxapine is a dibenzoxazepine that has a molecular structure similar to clozapine.13 Unlike clozapine, however, loxapine is not known to cause agranulocytosis.14 Research suggests that although clozapine is oxidized to metabolites that are cytotoxic, loxapine is not, potentially accounting for their different effects on neutrophils.15

The efficacy of loxapine has shown to be similar to other typical and atypical antipsychotics, with approximately 70% of patients showing improvement.14 However, loxapine may be overlooked as an option, possibly because it was not included in the CATIE trial and was the last typical antipsychotic to be approved before atypicals were introduced.12 First available in oral and IM formulations, there has been increased interest in loxapine recently because of the approval of an inhaled formulation in 2012.16

Although classified as a typical antipsychotic, studies have suggested that loxapine acts as an atypical at low dosages.17,18 Previous work suggests, however, that the side effect profile of loxapine is similar to typical antipsychotics.14 At dosages <50 mg, it results in fewer cases of extrapyramidal side effects than expected with a typical antipsychotic.18

Loxapine’s binding profile seems to exist along this spectrum of typical to atypical. Tissue-based binding studies have shown a higher 5-HT2 affinity relative to D2, consistent with atypical antipsychotics.19 Positron emission tomography studies in humans show 5-HT2 saturation of loxapine to be close to equal to D2 binding in loxapine, thus a slightly lower ratio of 5-HT2 to D2 relative to atypicals, but more than that seen with typical antipsychotics.20 These differences between in vitro and in vivo studies may be secondary to the binding of loxapine’s active metabolites, particularly 7- and 8-hydroxyloxapine, which have more dopaminergic activity. In addition to increased 5-HT2A binding compared with typical antipsychotics, loxapine also has a high affinity for the D4 receptors, as well as interacting with other serotonin receptors 5-HT3, 5-HT6, and 5-HT7. Of note this is a similar pattern of binding affinity as seen in clozapine.19

It should be noted, however, that loxapine may not be an appropriate treatment in all forms of cancer. Similar to other first-generation antipsychotics, it increases prolactin levels, and thus may have a negative clinical impact on patients with prolactin receptor positive breast cancers.21,22 Finally, although clozapine can result in significant weight gain, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia, unlike many antipsychotics, loxapine has been shown to be weight neutral or result in weight loss,14 making it an option to consider for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia, or cardiovascular disease.

OUTCOME Improvement, stability

Ms. B begins taking loxapine, 10 mg/d, gradually cross-tapered with olanzapine, increasing loxapine by 10 mg every 2 to 3 days (Figure). After 8 days, when the dosage has reached 40 mg/d, Ms. B’s treatment team begins to observe a consistent change in her behavior. Ms. B comes into the interview room, where previously the team had to see her in her own room because she refused to come out. She also tolerates an extensive interview, even sharing parts of her history without prompting, and is able to discuss her treatment. Ms. B continues to express some paranoia regarding the treatment team. On day 12, receiving loxapine, 50 mg/d, Ms. B says that she likes the new medication and feels she is doing well with it. She becomes less reclusive and begins socializing with other patients. By day 19, receiving loxapine, 80 mg/d, a nurse, who knows Ms. B from the outpatient facility, visits the unit and reports that Ms. B is at her baseline.

At discharge, Ms. B is noted to be “bright,” well organized, neatly dressed, and wearing makeup. Her paranoia and auditory hallucinations have almost completely resolved. She is social, engages appropriately with the treatment team, and is able to describe a plan for self-care after discharge including following up with her oncologist. Her white blood cell counts were carefully monitored throughout her admission and are within normal limits when she is discharged.

One year later, Ms. B remains taking loxapine, 70 mg/d. Although she continues to report mild paranoia, she is living independently in her apartment and attends church regularly.

2. Usta NG, Poyraz CA, Aktan M, et al. Clozapine treatment of refractory schizophrenia during essential chemotherapy: a case study and mini review of a clinical dilemma. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(6):276-281.

3. Meyer N, Gee S, Whiskey E, et al. Optimizing outcomes in clozapine rechallenge following neutropenia: a cohort analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(11):e1410-e1416.

4. Cunningham NT, Dennis N, Dattilo W, et al. Continuation of clozapine during chemotherapy: a case report and review of literature. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(6):673-679.

5. Co¸sar B, Taner ME, Eser HY, et al. Does switching to another antipsychotic in patients with clozapine-associated granulocytopenia solve the problem? Case series of 18. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(2):169-173.

6. McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, et al; CATIE Investigation. Effectiveness of clozapine versus olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia who did not respond to prior atypical antipsychotic treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):600-610.

7. Mustafa FA, Burke JG, Abukmeil SS, et al. “Schizophrenia past clozapine”: reasons for clozapine discontinuation, mortality, and alternative antipsychotic prescribing. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2015;48(1):11-14.

8. Aydin M, Ilhan BC, Calisir S, et al. Continuing clozapine treatment with lithium in schizophrenic patients with neutropenia or leukopenia: brief review of literature with case reports. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2016;6(1):33-38.

9. Bitter I, Dossenbach MR, Brook S, et al; Olanzapine HGCK Study Group. Olanzapine versus clozapine in treatment-resistant or treatment-intolerant schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28(1):173-180.

10. Lehmann CR, Ereshefsky L, Saklad SR, et al. Very high dose loxapine in refractory schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138(9):1212-1214.

11. Sokolski KN. Combination loxapine and aripiprazole for refractory hallucinations in schizophrenia. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(7-8):e36.

12. Shen WW. A history of antipsychotic drug development. Compr Psychiatry. 1999;40(6):407-414.

13. Mazzola CD, Miron S, Jenkins AJ. Loxapine intoxication: case report and literature review. J Anal Toxicol. 2000;24(7):638-641.

14. Chakrabarti A, Bagnall A, Chue P, et al. Loxapine for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007(4):CD001943.

15. Jegouzo A, Gressier B, Frimat B, et al. Comparative oxidation of loxapine and clozapine by human neutrophils. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1999;13(1):113-119.

16. Keating GM. Loxapine inhalation powder: a review of its use in the acute treatment of agitation in patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(6):479-489.

1 7. Glazer WM. Does loxapine have “atypical” properties? Clinical evidence. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 10):42-46.

18. Hellings JA, Jadhav M, Jain S, et al. Low dose loxapine: neuromotor side effects and tolerability in autism spectrum disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2015;25(8):618-624.

19. Singh AN, Barlas C, Singh S, et al. A neurochemical basis for the antipsychotic activity of loxapine: interactions with dopamine D1, D2, D4 and serotonin 5-HT2 receptor subtypes. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1996;21(1):29-35.

20. Kapur S, Zipursky RB, Remington G. Clinical and theoretical implications of 5-HT2 and D2 receptor occupancy of clozapine, risperidone, and olanzapine in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(2):286-293.

21. Robertson AG, Berry R, Meltzer HY. Prolactin stimulating effects of amoxapine and loxapine in psychiatric patients. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1982;78(3):287-292.

22. Rahman T, Clevenger CV, Kaklamani V, et al. Antipsychotic treatment in breast cancer patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(6):616-621.

2. Usta NG, Poyraz CA, Aktan M, et al. Clozapine treatment of refractory schizophrenia during essential chemotherapy: a case study and mini review of a clinical dilemma. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(6):276-281.

3. Meyer N, Gee S, Whiskey E, et al. Optimizing outcomes in clozapine rechallenge following neutropenia: a cohort analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(11):e1410-e1416.

4. Cunningham NT, Dennis N, Dattilo W, et al. Continuation of clozapine during chemotherapy: a case report and review of literature. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(6):673-679.

5. Co¸sar B, Taner ME, Eser HY, et al. Does switching to another antipsychotic in patients with clozapine-associated granulocytopenia solve the problem? Case series of 18. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(2):169-173.

6. McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, et al; CATIE Investigation. Effectiveness of clozapine versus olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia who did not respond to prior atypical antipsychotic treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):600-610.

7. Mustafa FA, Burke JG, Abukmeil SS, et al. “Schizophrenia past clozapine”: reasons for clozapine discontinuation, mortality, and alternative antipsychotic prescribing. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2015;48(1):11-14.

8. Aydin M, Ilhan BC, Calisir S, et al. Continuing clozapine treatment with lithium in schizophrenic patients with neutropenia or leukopenia: brief review of literature with case reports. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2016;6(1):33-38.

9. Bitter I, Dossenbach MR, Brook S, et al; Olanzapine HGCK Study Group. Olanzapine versus clozapine in treatment-resistant or treatment-intolerant schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28(1):173-180.

10. Lehmann CR, Ereshefsky L, Saklad SR, et al. Very high dose loxapine in refractory schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138(9):1212-1214.

11. Sokolski KN. Combination loxapine and aripiprazole for refractory hallucinations in schizophrenia. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(7-8):e36.

12. Shen WW. A history of antipsychotic drug development. Compr Psychiatry. 1999;40(6):407-414.

13. Mazzola CD, Miron S, Jenkins AJ. Loxapine intoxication: case report and literature review. J Anal Toxicol. 2000;24(7):638-641.

14. Chakrabarti A, Bagnall A, Chue P, et al. Loxapine for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007(4):CD001943.

15. Jegouzo A, Gressier B, Frimat B, et al. Comparative oxidation of loxapine and clozapine by human neutrophils. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1999;13(1):113-119.

16. Keating GM. Loxapine inhalation powder: a review of its use in the acute treatment of agitation in patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(6):479-489.

1 7. Glazer WM. Does loxapine have “atypical” properties? Clinical evidence. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 10):42-46.

18. Hellings JA, Jadhav M, Jain S, et al. Low dose loxapine: neuromotor side effects and tolerability in autism spectrum disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2015;25(8):618-624.

19. Singh AN, Barlas C, Singh S, et al. A neurochemical basis for the antipsychotic activity of loxapine: interactions with dopamine D1, D2, D4 and serotonin 5-HT2 receptor subtypes. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1996;21(1):29-35.

20. Kapur S, Zipursky RB, Remington G. Clinical and theoretical implications of 5-HT2 and D2 receptor occupancy of clozapine, risperidone, and olanzapine in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(2):286-293.

21. Robertson AG, Berry R, Meltzer HY. Prolactin stimulating effects of amoxapine and loxapine in psychiatric patients. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1982;78(3):287-292.

22. Rahman T, Clevenger CV, Kaklamani V, et al. Antipsychotic treatment in breast cancer patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(6):616-621.

Herb–drug interactions: Caution patients when changing supplements

Ms. X, age 41, has a history of bipolar disorder and presents with extreme sleepiness, constipation with mild abdominal cramping, occasional dizziness, and “palpitations.” Although usually she is quite articulate, Ms. X seems to have trouble describing her symptoms and reports that they have been worsening over 4 to 6 days. She is worried because she is making mistakes at work and repeatedly misunderstanding directions.

Ms. X has a family history of hyperlipidemia, heart disease, and diabetes, and she has been employing a healthy diet, exercise, and use of supplements for cardiovascular health since her early 20s. Her medication regimen includes lithium, 600 mg, twice a day, quetiapine, 1,200 mg/d, a multivitamin and mineral tablet once a day, a brand name garlic supplement (garlic powder, 300 mg, vitamin C, 80 mg, vitamin E, 20 IU, vitamin A, 2,640 IU) twice a day, and fish oil, 2 g/d, at bedtime. Lithium levels consistently have been 0.8 to 0.9 mEq/L for the last 3 years.

Factors of drug–supplement interactions

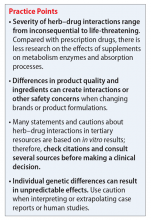

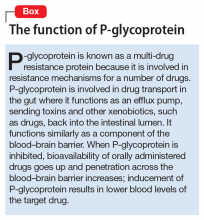

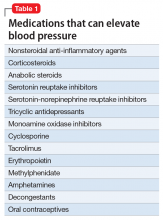

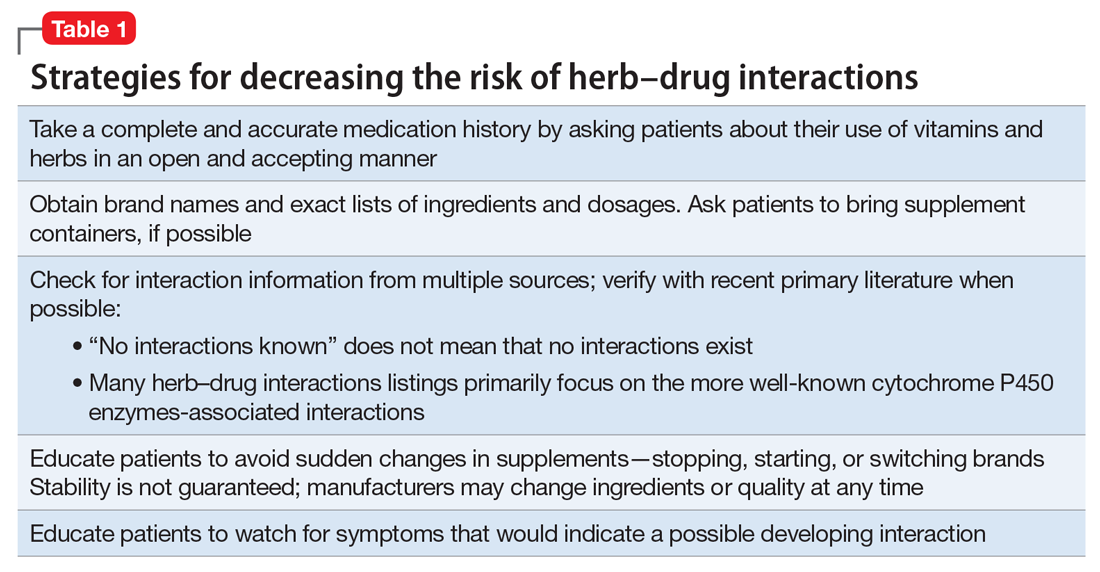

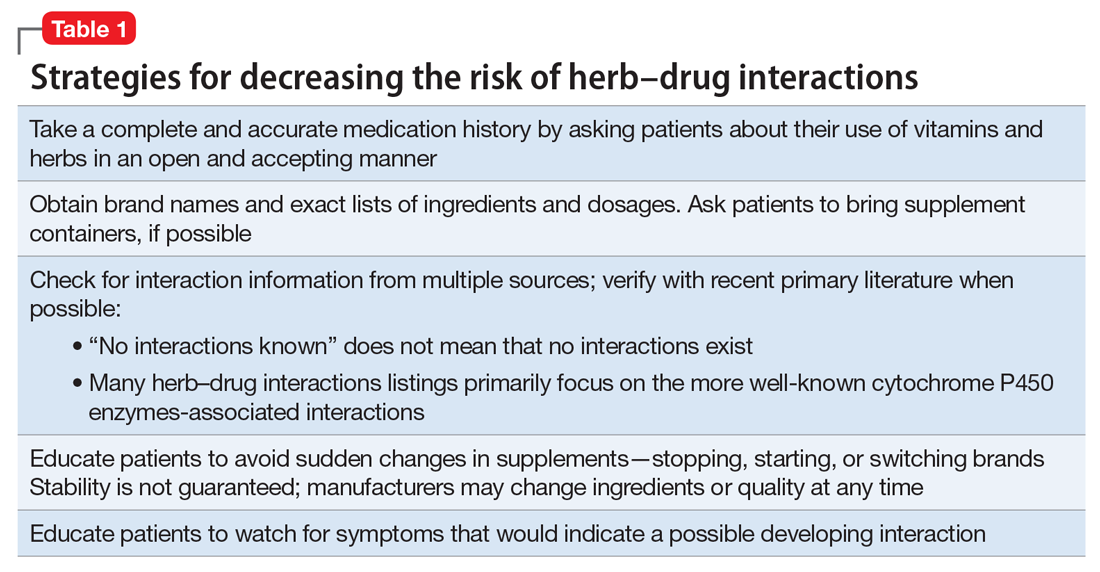

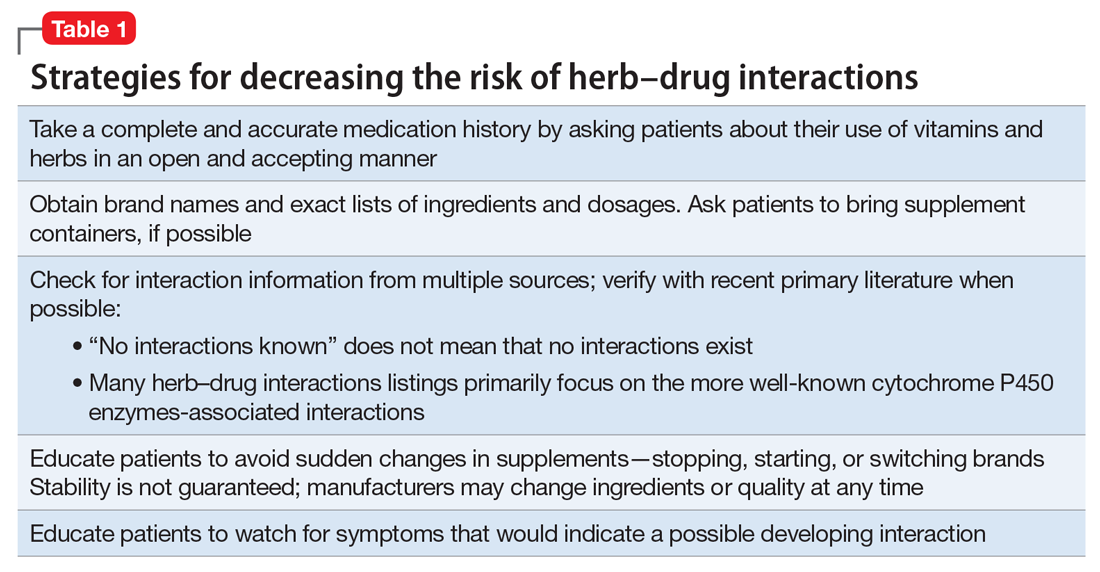

Because an interaction is possible doesn’t always mean that a drug and an offending botanical cannot be used together. With awareness and planning, possible interactions can be safely managed (Table 1). Such was the case of Ms. X, who was stable on a higher-than-usual dosage of quetiapine (average target is 600 mg/d for bipolar disorder) because of presumed moderate enzyme induction by the brand name garlic supplement. Ms. X did not want to stop taking this supplement when she started quetiapine. Although garlic is listed as a possible moderate cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 inducer, there is conflicting evidence.1 Ms. X’s clinician advised her to avoid changes in dosage, because it could affect her quetiapine levels. However, the change in the botanical preparation from dried, powdered garlic to garlic oil likely removed the CYP3A4 enzyme induction, leading to a lower rate of metabolism and accumulation of the drug to toxic levels.

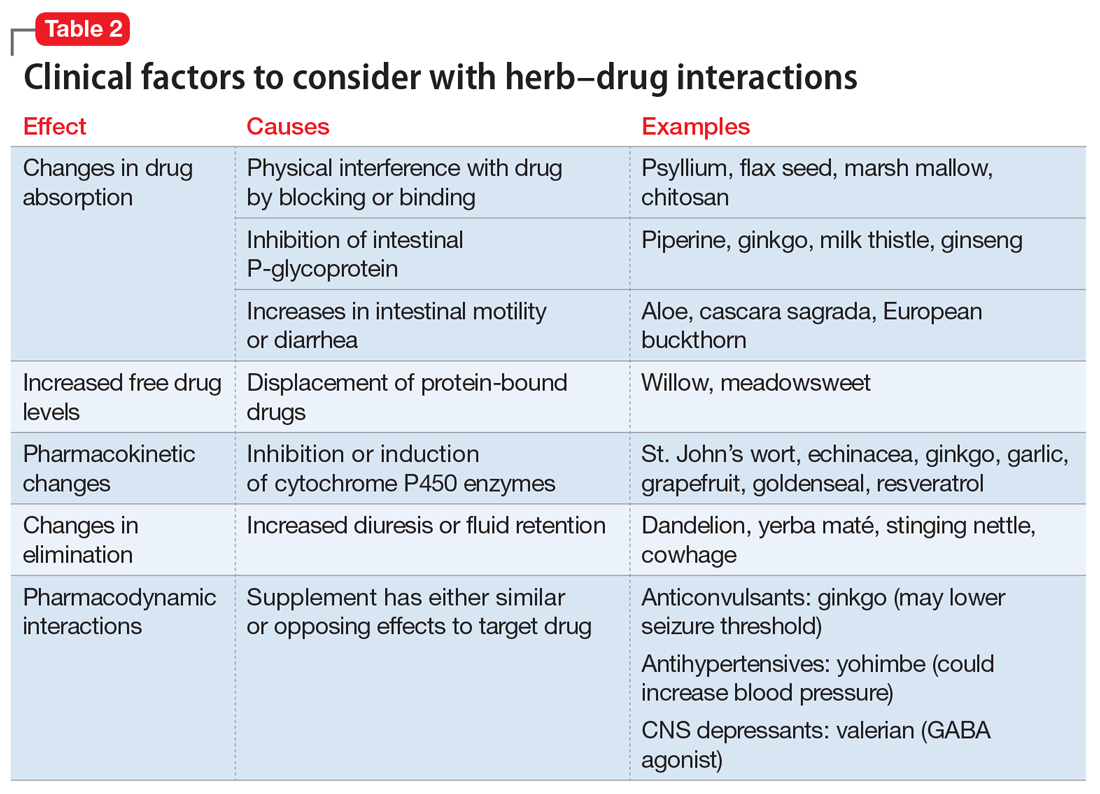

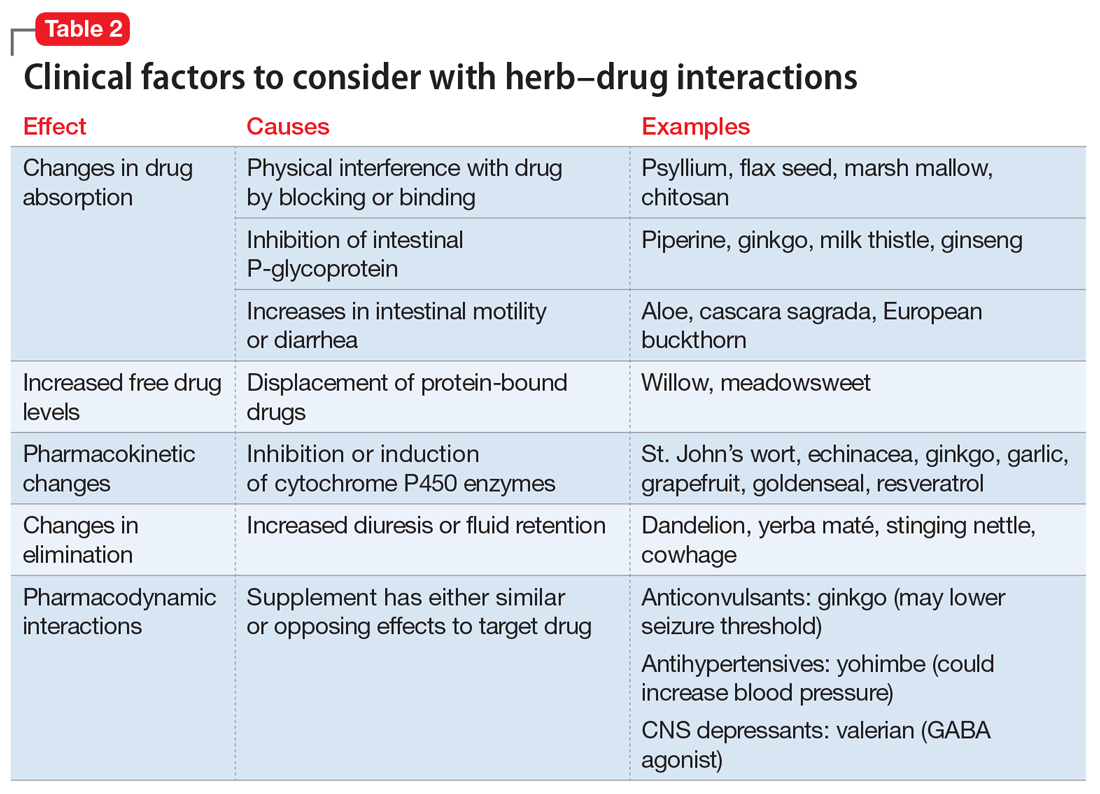

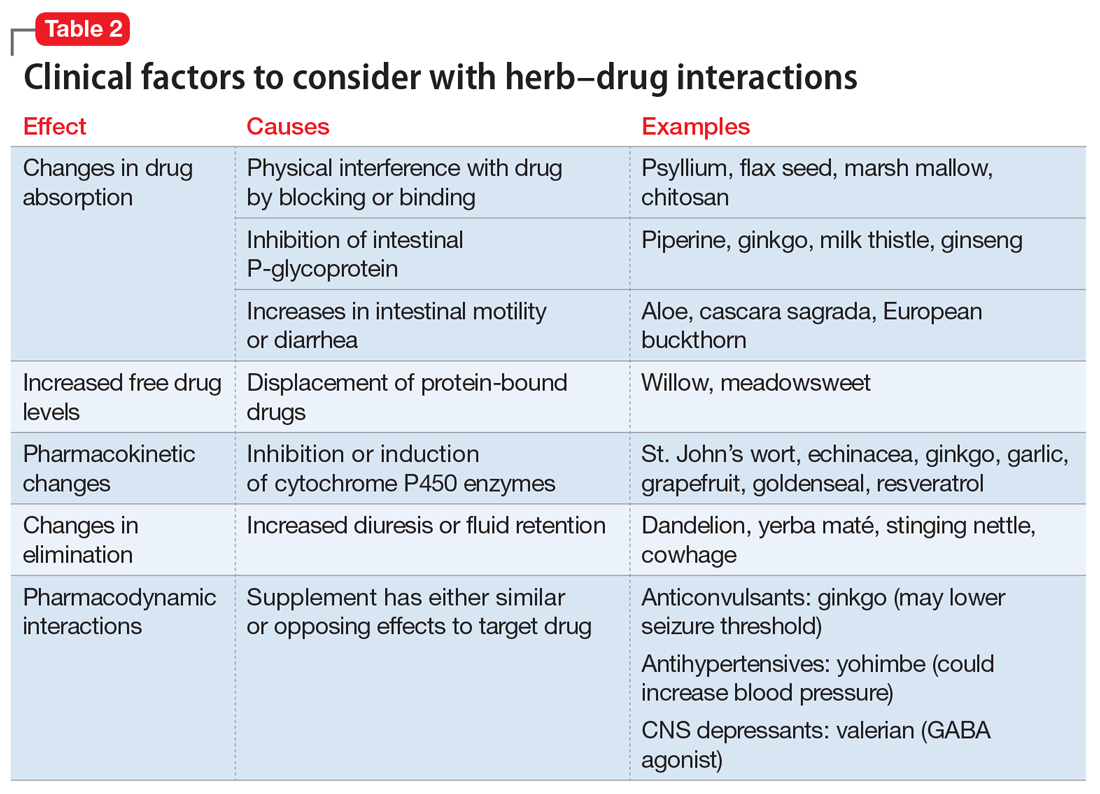

Drug metabolism. Practitioners are increasingly aware that St. John’s wort can significantly affect concomitantly administered drug levels by induction of the CYP isoenzyme 3A4 and more resources are listing this same possible induction for garlic.1 However, what is less understood is the extent to which different preparations of the same plant possess different chemical profiles (Table 2).

Clinical studies with different garlic preparations—dried powder, aqueous extracts, deodorized preparations, oils—have demonstrated diverse and highly variable results in tests of effects on CYP isoenzymes and other metabolism activities.

Drug absorption. Small differences in amounts of vitamins in the supplement are unlikely to be clinically significant, but the addition of piperine could be affecting quetiapine absorption. Piperine, a constituent of black pepper and long pepper, is used in Ayurvedic medicine for:

- pain

- influenza

- rheumatoid arthritis

- asthma

- loss of appetite

- stimulating peristalsis.6

Animal studies have demonstrated anti-inflammatory, anticonvulsant, anticarcinogenic, and antioxidant effects, as well as stimulation of digestion via digestive enzyme secretion and increased gastromotility.3,6

Because piperine is known to increase intestinal absorption by various mechanisms, it often is added to botanical medicines to increase bioavailability of active components. BioPerine is a 95% piperine extract marketed to be included in vitamin and herbal supplements for that purpose.3 This allows use of lower dosages to achieve outcomes, which, for expensive botanicals, could be a cost savings for the manufacturer. Studies examining piperine’s influence on drug absorption have demonstrated significant increases in carbamazepine, rifampin, phenytoin, nevirapine, and many other drugs.

In addition to increased absorption, piperine seems to be a non-specific general inhibitor of CYP isoenzymes; IV phenytoin levels also were higher among test participants.6,8 Piperine reduces intestinal glucuronidation via uridine 5’-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase inhibition, and the small or moderate effects on lithium levels seem to be the result of diuretic activities.3,7

Patients often are motivated to control at least 1 aspect of their medical treatment, such as the supplements they choose to take. Being open to patient use of non-harmful or low-risk supplements, even when they are unlikely to have any medicinal benefit, helps preserve a relationship in which patients are more likely to consider your recommendation to avoid a harmful or high-risk supplement.

Related Resources

1. Natural Medicines Database. Garlic monograph. http://naturaldatabase.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed May 1, 2017.

2. Wanwimolruk S, Prachayasittikul V. Cytochrome P450 enzyme mediated herbal drug interactions (part 1). EXCLI J. 2014;13:347-391.

3. Colalto C. Herbal interactions on absorption of drugs: mechanism of action and clinical risk assessment. Pharmacol Res. 2010;62(3):207-227.

4. Gurley BJ, Gardner SF, Hubbard MA, et al. Clinical assessment of effects of botanical supplementation on cytochrome P450 phenotypes in the elderly: St. John’s wort, garlic oil, Panax ginseng and Ginkgo biloba. Drugs Aging. 2005;22(6):525-539.

5. Gallicano K, Foster B, Choudhri S. Effect of short-term administration of garlic supplements on single-dose ritonavir pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;55(2):199-202.

6. Meghwal M, Goswami TK. Piper nigrum and piperine: an update. Phytother Res. 2013;27(8):1121-1130.

7. Natural Medicines Database. Black pepper monograph. https://www.naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed May 1, 2017.

8. Zhou S, Lim LY, Chowbay B. Herbal modulation of p-glycoprotein. Drug Metab Rev. 2004;36(1):57-104.

9. Chinta G, Syed B, Coumar MS, et al. Piperine: a comprehensive review of pre-clinical and clinical investigations. Curr Bioact Compd. 2015;11(3):156-169.

Ms. X, age 41, has a history of bipolar disorder and presents with extreme sleepiness, constipation with mild abdominal cramping, occasional dizziness, and “palpitations.” Although usually she is quite articulate, Ms. X seems to have trouble describing her symptoms and reports that they have been worsening over 4 to 6 days. She is worried because she is making mistakes at work and repeatedly misunderstanding directions.

Ms. X has a family history of hyperlipidemia, heart disease, and diabetes, and she has been employing a healthy diet, exercise, and use of supplements for cardiovascular health since her early 20s. Her medication regimen includes lithium, 600 mg, twice a day, quetiapine, 1,200 mg/d, a multivitamin and mineral tablet once a day, a brand name garlic supplement (garlic powder, 300 mg, vitamin C, 80 mg, vitamin E, 20 IU, vitamin A, 2,640 IU) twice a day, and fish oil, 2 g/d, at bedtime. Lithium levels consistently have been 0.8 to 0.9 mEq/L for the last 3 years.

Factors of drug–supplement interactions

Because an interaction is possible doesn’t always mean that a drug and an offending botanical cannot be used together. With awareness and planning, possible interactions can be safely managed (Table 1). Such was the case of Ms. X, who was stable on a higher-than-usual dosage of quetiapine (average target is 600 mg/d for bipolar disorder) because of presumed moderate enzyme induction by the brand name garlic supplement. Ms. X did not want to stop taking this supplement when she started quetiapine. Although garlic is listed as a possible moderate cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 inducer, there is conflicting evidence.1 Ms. X’s clinician advised her to avoid changes in dosage, because it could affect her quetiapine levels. However, the change in the botanical preparation from dried, powdered garlic to garlic oil likely removed the CYP3A4 enzyme induction, leading to a lower rate of metabolism and accumulation of the drug to toxic levels.

Drug metabolism. Practitioners are increasingly aware that St. John’s wort can significantly affect concomitantly administered drug levels by induction of the CYP isoenzyme 3A4 and more resources are listing this same possible induction for garlic.1 However, what is less understood is the extent to which different preparations of the same plant possess different chemical profiles (Table 2).

Clinical studies with different garlic preparations—dried powder, aqueous extracts, deodorized preparations, oils—have demonstrated diverse and highly variable results in tests of effects on CYP isoenzymes and other metabolism activities.

Drug absorption. Small differences in amounts of vitamins in the supplement are unlikely to be clinically significant, but the addition of piperine could be affecting quetiapine absorption. Piperine, a constituent of black pepper and long pepper, is used in Ayurvedic medicine for:

- pain

- influenza

- rheumatoid arthritis

- asthma

- loss of appetite

- stimulating peristalsis.6

Animal studies have demonstrated anti-inflammatory, anticonvulsant, anticarcinogenic, and antioxidant effects, as well as stimulation of digestion via digestive enzyme secretion and increased gastromotility.3,6

Because piperine is known to increase intestinal absorption by various mechanisms, it often is added to botanical medicines to increase bioavailability of active components. BioPerine is a 95% piperine extract marketed to be included in vitamin and herbal supplements for that purpose.3 This allows use of lower dosages to achieve outcomes, which, for expensive botanicals, could be a cost savings for the manufacturer. Studies examining piperine’s influence on drug absorption have demonstrated significant increases in carbamazepine, rifampin, phenytoin, nevirapine, and many other drugs.

In addition to increased absorption, piperine seems to be a non-specific general inhibitor of CYP isoenzymes; IV phenytoin levels also were higher among test participants.6,8 Piperine reduces intestinal glucuronidation via uridine 5’-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase inhibition, and the small or moderate effects on lithium levels seem to be the result of diuretic activities.3,7

Patients often are motivated to control at least 1 aspect of their medical treatment, such as the supplements they choose to take. Being open to patient use of non-harmful or low-risk supplements, even when they are unlikely to have any medicinal benefit, helps preserve a relationship in which patients are more likely to consider your recommendation to avoid a harmful or high-risk supplement.

Related Resources

Ms. X, age 41, has a history of bipolar disorder and presents with extreme sleepiness, constipation with mild abdominal cramping, occasional dizziness, and “palpitations.” Although usually she is quite articulate, Ms. X seems to have trouble describing her symptoms and reports that they have been worsening over 4 to 6 days. She is worried because she is making mistakes at work and repeatedly misunderstanding directions.

Ms. X has a family history of hyperlipidemia, heart disease, and diabetes, and she has been employing a healthy diet, exercise, and use of supplements for cardiovascular health since her early 20s. Her medication regimen includes lithium, 600 mg, twice a day, quetiapine, 1,200 mg/d, a multivitamin and mineral tablet once a day, a brand name garlic supplement (garlic powder, 300 mg, vitamin C, 80 mg, vitamin E, 20 IU, vitamin A, 2,640 IU) twice a day, and fish oil, 2 g/d, at bedtime. Lithium levels consistently have been 0.8 to 0.9 mEq/L for the last 3 years.

Factors of drug–supplement interactions

Because an interaction is possible doesn’t always mean that a drug and an offending botanical cannot be used together. With awareness and planning, possible interactions can be safely managed (Table 1). Such was the case of Ms. X, who was stable on a higher-than-usual dosage of quetiapine (average target is 600 mg/d for bipolar disorder) because of presumed moderate enzyme induction by the brand name garlic supplement. Ms. X did not want to stop taking this supplement when she started quetiapine. Although garlic is listed as a possible moderate cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 inducer, there is conflicting evidence.1 Ms. X’s clinician advised her to avoid changes in dosage, because it could affect her quetiapine levels. However, the change in the botanical preparation from dried, powdered garlic to garlic oil likely removed the CYP3A4 enzyme induction, leading to a lower rate of metabolism and accumulation of the drug to toxic levels.

Drug metabolism. Practitioners are increasingly aware that St. John’s wort can significantly affect concomitantly administered drug levels by induction of the CYP isoenzyme 3A4 and more resources are listing this same possible induction for garlic.1 However, what is less understood is the extent to which different preparations of the same plant possess different chemical profiles (Table 2).

Clinical studies with different garlic preparations—dried powder, aqueous extracts, deodorized preparations, oils—have demonstrated diverse and highly variable results in tests of effects on CYP isoenzymes and other metabolism activities.

Drug absorption. Small differences in amounts of vitamins in the supplement are unlikely to be clinically significant, but the addition of piperine could be affecting quetiapine absorption. Piperine, a constituent of black pepper and long pepper, is used in Ayurvedic medicine for:

- pain

- influenza

- rheumatoid arthritis

- asthma

- loss of appetite

- stimulating peristalsis.6

Animal studies have demonstrated anti-inflammatory, anticonvulsant, anticarcinogenic, and antioxidant effects, as well as stimulation of digestion via digestive enzyme secretion and increased gastromotility.3,6

Because piperine is known to increase intestinal absorption by various mechanisms, it often is added to botanical medicines to increase bioavailability of active components. BioPerine is a 95% piperine extract marketed to be included in vitamin and herbal supplements for that purpose.3 This allows use of lower dosages to achieve outcomes, which, for expensive botanicals, could be a cost savings for the manufacturer. Studies examining piperine’s influence on drug absorption have demonstrated significant increases in carbamazepine, rifampin, phenytoin, nevirapine, and many other drugs.

In addition to increased absorption, piperine seems to be a non-specific general inhibitor of CYP isoenzymes; IV phenytoin levels also were higher among test participants.6,8 Piperine reduces intestinal glucuronidation via uridine 5’-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase inhibition, and the small or moderate effects on lithium levels seem to be the result of diuretic activities.3,7

Patients often are motivated to control at least 1 aspect of their medical treatment, such as the supplements they choose to take. Being open to patient use of non-harmful or low-risk supplements, even when they are unlikely to have any medicinal benefit, helps preserve a relationship in which patients are more likely to consider your recommendation to avoid a harmful or high-risk supplement.

Related Resources

1. Natural Medicines Database. Garlic monograph. http://naturaldatabase.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed May 1, 2017.

2. Wanwimolruk S, Prachayasittikul V. Cytochrome P450 enzyme mediated herbal drug interactions (part 1). EXCLI J. 2014;13:347-391.

3. Colalto C. Herbal interactions on absorption of drugs: mechanism of action and clinical risk assessment. Pharmacol Res. 2010;62(3):207-227.

4. Gurley BJ, Gardner SF, Hubbard MA, et al. Clinical assessment of effects of botanical supplementation on cytochrome P450 phenotypes in the elderly: St. John’s wort, garlic oil, Panax ginseng and Ginkgo biloba. Drugs Aging. 2005;22(6):525-539.

5. Gallicano K, Foster B, Choudhri S. Effect of short-term administration of garlic supplements on single-dose ritonavir pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;55(2):199-202.

6. Meghwal M, Goswami TK. Piper nigrum and piperine: an update. Phytother Res. 2013;27(8):1121-1130.

7. Natural Medicines Database. Black pepper monograph. https://www.naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed May 1, 2017.

8. Zhou S, Lim LY, Chowbay B. Herbal modulation of p-glycoprotein. Drug Metab Rev. 2004;36(1):57-104.

9. Chinta G, Syed B, Coumar MS, et al. Piperine: a comprehensive review of pre-clinical and clinical investigations. Curr Bioact Compd. 2015;11(3):156-169.

1. Natural Medicines Database. Garlic monograph. http://naturaldatabase.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed May 1, 2017.

2. Wanwimolruk S, Prachayasittikul V. Cytochrome P450 enzyme mediated herbal drug interactions (part 1). EXCLI J. 2014;13:347-391.

3. Colalto C. Herbal interactions on absorption of drugs: mechanism of action and clinical risk assessment. Pharmacol Res. 2010;62(3):207-227.

4. Gurley BJ, Gardner SF, Hubbard MA, et al. Clinical assessment of effects of botanical supplementation on cytochrome P450 phenotypes in the elderly: St. John’s wort, garlic oil, Panax ginseng and Ginkgo biloba. Drugs Aging. 2005;22(6):525-539.

5. Gallicano K, Foster B, Choudhri S. Effect of short-term administration of garlic supplements on single-dose ritonavir pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;55(2):199-202.

6. Meghwal M, Goswami TK. Piper nigrum and piperine: an update. Phytother Res. 2013;27(8):1121-1130.

7. Natural Medicines Database. Black pepper monograph. https://www.naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed May 1, 2017.

8. Zhou S, Lim LY, Chowbay B. Herbal modulation of p-glycoprotein. Drug Metab Rev. 2004;36(1):57-104.

9. Chinta G, Syed B, Coumar MS, et al. Piperine: a comprehensive review of pre-clinical and clinical investigations. Curr Bioact Compd. 2015;11(3):156-169.

‘3 Strikes ‘n’ yer out’: Dismissing no-show patients

Dear Dr. Mossman,

The clinic where I work initiated a “3 misses and out” policy: If a patient doesn’t show for 3 appointments in a 12-month period, the clinic removes him from the patient rolls. I’ve heard such policies are common, but I worry: Is this abandonment?

Submitted by “Dr. C”

The short answer to Dr. C’s question is, “Handled properly, it’s not abandonment.” But if this response really was satisfactory, Dr. C probably would not have asked the question. Dealing with no-show patients has bothered psychiatrists, other mental health professionals, and other physicians for decades.1

Clinicians worry when patients miss important follow-up, and unreimbursed office time won’t help pay a clinician’s salary or office expenses.2 But a policy such as the one Dr. C describes may not be the best response—clinically or financially—for many patients who miss appointments repeatedly.

If no-show patients worry you or cause problems where you practice, read on as I cover:

- charging for missed appointments

- why patients miss appointments

- evidence-based methods to improve show-up rates

- when ending a treatment relationship unilaterally is not abandonment

- how to dismiss no-show patients from a practice properly.

Before the mid-1980s, most office-based psychiatrists worked in solo or small group and required patients to pay cash for treatment; approximately 40% of psychiatrists still practice this way.3 Often, private practice clinicians require payment for appointments missed without 24 hours’ notice. This well-accepted practice2,4,5 reinforces the notion that psychotherapy involves making a commitment to work on problems. It also protects clinicians’ financial interests and mitigates possible resentment that might arise if office time committed to a patient went unreimbursed.6 Clinicians who charge for missed appointments should inform patients of this at the beginning of treatment, explaining clearly that the patient—not the insurer—will be paying for unused treatment time.2,4

Since the 1980s, outpatient psychiatrists have increasingly worked in public agencies or other organizational practice settings7 where patients—whose care is funded by public monies or third-party payors—cannot afford to pay for missed appointments. If you work in a clinic such as the one where Dr. C provides services, you probably are paid an hourly wage whether your patients show up or not. To pay you and remain solvent, your clinic must find ways other than charging patients to address and reduce no-shows.

The literature abounds with research on why no-shows occur. But no-shows seem to be more common in psychiatry than in other medical specialties.8 The frequency of no-shows varies considerably, but it’s a big problem in some mental health treatment contexts, with reported rates ranging from 12% to 60%.9 A recent, comprehensive review reported that approximately 30% of patients refuse, drop out, or prematurely disengage from services after first-episode psychosis.10 No-shows and drop outs are linked to clinical deterioration11 and heightened risk of hospitalization.12

Jaeschke et al15 suggests that no-shows, dropping out of treatment, and other forms of what doctors call “noncompliance” or “nonadherence” might be better conceptualized as a lack of “concordance,” “mutuality,” or “shared ideology” about what ails patients and the role of their physicians. For this reason, striving for a “partnership between a physician and a patient,” with the patient “fully engaged in the two-way communication with a doctor … seems to be a much more suitable way of achieving therapeutic progress in the discipline of psychiatry.”15

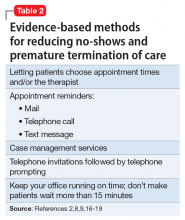

Reducing no-shows: Evidence-based methods

Many medical and mental health articles describe evidence-based methods for lowering no-show rates. Studies document the value of assertive outreach, home visits, avoiding scheduling on religious holidays, scheduling appointments in the afternoon rather than the morning, providing assistance with transportation,8 sending reminder letters,16 or making telephone calls.17 Growing evidence suggests that text messages reduce missed appointments, even among patients with severe disorders (eg, schizophrenia) that compromise cognitive functioning.18

The measures I’ve described won’t prevent every patient from no-showing repeatedly. If you or your employer have tried some of these proven methods and they haven’t reduced a patient’s persistent no-shows, and if it makes sense from a clinical and financial standpoint, then it’s all right to dismiss the patient.

To understand why you are permitted to dismiss a patient from your practice, it helps to understand how the law views the doctor–patient relationship. A doctor has no legal duty to treat anyone—even someone who desperately needs care—unless the doctor has taken some action to establish a treatment relationship with that person. Having previously treated the patient establishes a treatment relationship, as could other actions such as giving specific advice or (in some cases) making an appointment for a person. Once you have a treatment relationship with someone, you usually must continue to provide necessary medical attention until either the treatment episode has concluded or you and the patient agree to end treatment.20

For many chronic mental illnesses, a treatment episode could last years. But this does not force you to continue caring for a patient indefinitely if your circumstances change or if the patient’s behavior causes you to want to withdraw from providing care.

To ethically end care of a patient while a treatment episode is ongoing, you must either transfer care to another competent physician, or give your patient adequate notice and opportunity to obtain appropriate treatment elsewhere.20 If you fail to do either, however, you are guilty of “abandonment” and potentially subject to discipline by state licensing authorities21 or, if harm results, a malpractice lawsuit.22

In many states, statutes or regulations describe what you must do to end a treatment relationship properly. Ohio’s rule is typical: You must send the patient a certified letter explaining that the treatment relationship is ending, that you will remain available to provide care for 30 days, and that you will send treatment records to another provider upon receiving the patient’s signed authorization.21

One note of caution, however: If you practice in hospitals or groups, or if you or the agency where you work has signed provider contracts, you may have agreed to terms of practice that make dismissing a patient more complicated.23 Whether you practice individually or in a large organization, it’s usually wise to get advice from an attorney and/or your malpractice carrier to make sure you’re handling a patient dismissal the right way.

1. Adler LM, Yamamoto J, Goin M. Failed psychiatric clinic appointments. Relationship to social class. Calif Med. 1963;99:388-392.

2. Buppert C. How to deal with missed appointments. Dermatol Nurs 2009;21(4):207-208.

3. National Council Medical Director Institute. The psychiatric shortage: causes and solutions. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Psychiatric-Shortage_National-Council-.pdf. Published March 28, 2017. Accessed April 6, 2017.

4. Legal & Regulatory Affairs staff. Practitioner pointer: how to handle late and missed appointments. http://www.apapracticecentral.org/update/2014/11-06/late-missed-appoitments.aspx. Published November 6, 2004. Accessed April 7, 2017.

5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. MLN Matters Number: MM5613. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/downloads/MM5613.pdf. Updated November 12, 2014. Accessed April 7, 2017.

6. MacCutcheon M. Why I charge for late cancellations and no-shows to therapy. http://www.goodtherapy.org/blog/why-i-charge-for-late-cancellations-no-shows-to-therapy-0921164. Published September 21, 2016. Accessed April 6, 2017.

7. Kalman TP, Goldstein MA. Satisfaction of Manhattan psychiatrists with private practice: assessing the impact of managed care. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/430759_4. Accessed April 6, 2017.

8. Mitchell AJ, Selmes T. Why don’t patients attend their appointments? Maintaining engagement with psychiatric services. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2007;13(6):423-434.

9. Long J, Sakauye K, Chisty K, et al. The empty chair appointment. SAGE Open. 2016;6:1-5.

10. Doyle R, Turner N, Fanning F, et al. First-episode psychosis and disengagement from treatment: a systematic review. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(5):603-611.

11. Nelson EA, Maruish ME, Axler JL. Effects of discharge planning and compliance with outpatient appointments on readmission rates. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(7):885-889.

12. Killaspy H, Banerjee S, King M, et al. Prospective controlled study of psychiatric out-patient non-attendance. Characteristics and outcome. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:160-165.

13. Williamson AE, Ellis DA, Wilson P, et al. Understanding repeated non-attendance in health services: a pilot analysis of administrative data and full study protocol for a national retrospective cohort. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e014120. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014120.

14. Binnie J, Boden Z. Non-attendance at psychological therapy appointments. Mental Health Rev J. 2016;21(3):231-248.

15. Jaeschke R, Siwek M, Dudek D. Various ways of understanding compliance: a psychiatrist’s view. Arch Psychiatr Psychother. 2011;13(3):49-55.

16. Boland B, Burnett F. Optimising outpatient efficiency – development of an innovative ‘Did Not Attend’ management approach. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2014;18(3):217-219.

17. Pennington D, Hodgson J. Non‐attendance and invitation methods within a CBT service. Mental Health Rev J. 2012;17(3):145-151.

18. Sims H, Sanghara H, Hayes D, et al. Text message reminders of appointments: a pilot intervention at four community mental health clinics in London. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(2):161-168.

19. Oldham M, Kellett S, Miles E, et al. Interventions to increase attendance at psychotherapy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(5):928-939.

20. Gore AG, Grossman EL, Martin L, et al. Physicians, surgeons, and other healers. In: American Jurisprudence. 2nd ed, §130. Eagan, MN: West Publishing; 2017:61.

21. Ohio Administrative Code §4731-27-02.

22. Lowery v Miller, 157 Wis 2d 503, 460 N.W. 2d 446 (Wis App 1990).

23. Brockway LH. Terminating patient relationships: how to dismiss without abandoning. TMLT. https://www.tmlt.org/tmlt/tmlt-resources/newscenter/blog/2009/Terminating-patient-relationships.html. Published June 19, 2009. Accessed April 3, 2017.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

The clinic where I work initiated a “3 misses and out” policy: If a patient doesn’t show for 3 appointments in a 12-month period, the clinic removes him from the patient rolls. I’ve heard such policies are common, but I worry: Is this abandonment?

Submitted by “Dr. C”

The short answer to Dr. C’s question is, “Handled properly, it’s not abandonment.” But if this response really was satisfactory, Dr. C probably would not have asked the question. Dealing with no-show patients has bothered psychiatrists, other mental health professionals, and other physicians for decades.1

Clinicians worry when patients miss important follow-up, and unreimbursed office time won’t help pay a clinician’s salary or office expenses.2 But a policy such as the one Dr. C describes may not be the best response—clinically or financially—for many patients who miss appointments repeatedly.

If no-show patients worry you or cause problems where you practice, read on as I cover:

- charging for missed appointments

- why patients miss appointments

- evidence-based methods to improve show-up rates

- when ending a treatment relationship unilaterally is not abandonment

- how to dismiss no-show patients from a practice properly.

Before the mid-1980s, most office-based psychiatrists worked in solo or small group and required patients to pay cash for treatment; approximately 40% of psychiatrists still practice this way.3 Often, private practice clinicians require payment for appointments missed without 24 hours’ notice. This well-accepted practice2,4,5 reinforces the notion that psychotherapy involves making a commitment to work on problems. It also protects clinicians’ financial interests and mitigates possible resentment that might arise if office time committed to a patient went unreimbursed.6 Clinicians who charge for missed appointments should inform patients of this at the beginning of treatment, explaining clearly that the patient—not the insurer—will be paying for unused treatment time.2,4

Since the 1980s, outpatient psychiatrists have increasingly worked in public agencies or other organizational practice settings7 where patients—whose care is funded by public monies or third-party payors—cannot afford to pay for missed appointments. If you work in a clinic such as the one where Dr. C provides services, you probably are paid an hourly wage whether your patients show up or not. To pay you and remain solvent, your clinic must find ways other than charging patients to address and reduce no-shows.

The literature abounds with research on why no-shows occur. But no-shows seem to be more common in psychiatry than in other medical specialties.8 The frequency of no-shows varies considerably, but it’s a big problem in some mental health treatment contexts, with reported rates ranging from 12% to 60%.9 A recent, comprehensive review reported that approximately 30% of patients refuse, drop out, or prematurely disengage from services after first-episode psychosis.10 No-shows and drop outs are linked to clinical deterioration11 and heightened risk of hospitalization.12

Jaeschke et al15 suggests that no-shows, dropping out of treatment, and other forms of what doctors call “noncompliance” or “nonadherence” might be better conceptualized as a lack of “concordance,” “mutuality,” or “shared ideology” about what ails patients and the role of their physicians. For this reason, striving for a “partnership between a physician and a patient,” with the patient “fully engaged in the two-way communication with a doctor … seems to be a much more suitable way of achieving therapeutic progress in the discipline of psychiatry.”15