User login

Diabetes Hub contains news and clinical review articles for physicians seeking the most up-to-date information on the rapidly evolving options for treating and preventing Type 2 Diabetes in at-risk patients. The Diabetes Hub is powered by Frontline Medical Communications.

Adult diabetes up 35% over 25 years

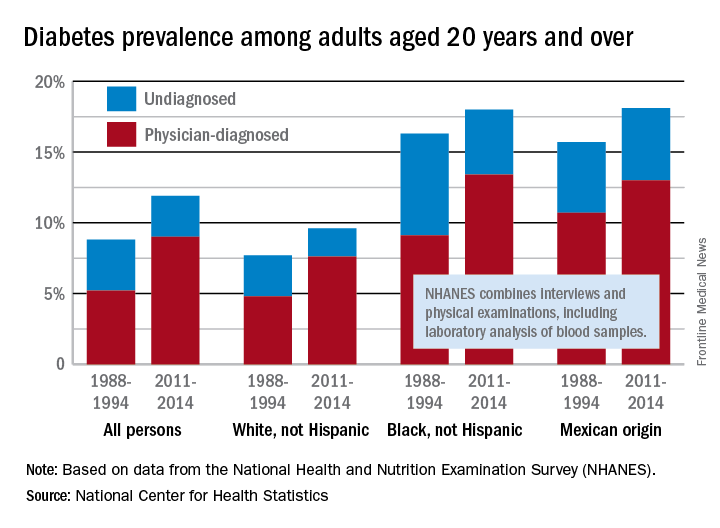

The overall prevalence of diabetes increased 35% from 1988-1994 to 2011-2014 among adults aged 20 years and over, according the National Center for Health Statistics.

During 2011-2014, the age-adjusted prevalence of diabetes was 11.9% in adults aged 20 years and over, compared with 8.8% in 1988-1994. That 35% increase came despite a decrease in undiagnosed diabetes from 3.6% to 2.9% over that time period, which was not enough to offset a jump in physician-diagnosed disease from 5.2% to 9%, the NCHS reported in “Health, United States, 2016.”

Undiagnosed diabetes dropped from 2.9% to 2% in whites and from 7.2% to 4.6% in blacks, but adults of Mexican origin saw a slight increase from 5% in 1988-1994 to 5.1% in 2011-2014. The physician-diagnosed side of the equation rose from 4.8% to 7.6% in whites, 9.1% to 13.4% in blacks, and 10.7% to 13% in those of Mexican origin, according to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, which combines interviews and physical examinations, including laboratory analysis of blood samples.

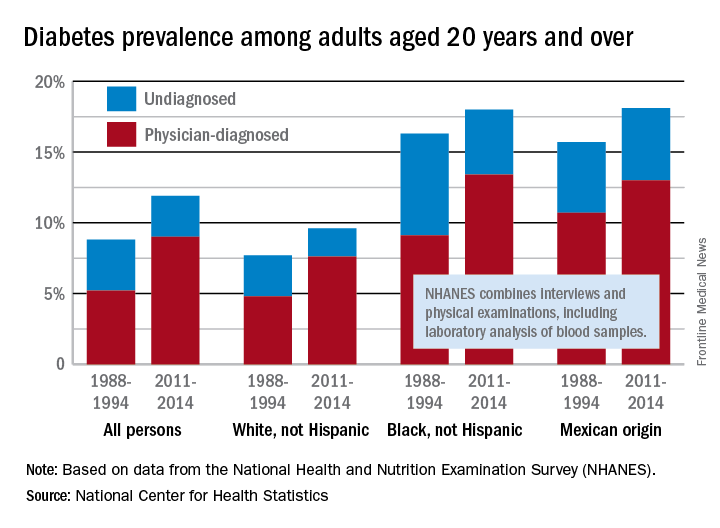

The overall prevalence of diabetes increased 35% from 1988-1994 to 2011-2014 among adults aged 20 years and over, according the National Center for Health Statistics.

During 2011-2014, the age-adjusted prevalence of diabetes was 11.9% in adults aged 20 years and over, compared with 8.8% in 1988-1994. That 35% increase came despite a decrease in undiagnosed diabetes from 3.6% to 2.9% over that time period, which was not enough to offset a jump in physician-diagnosed disease from 5.2% to 9%, the NCHS reported in “Health, United States, 2016.”

Undiagnosed diabetes dropped from 2.9% to 2% in whites and from 7.2% to 4.6% in blacks, but adults of Mexican origin saw a slight increase from 5% in 1988-1994 to 5.1% in 2011-2014. The physician-diagnosed side of the equation rose from 4.8% to 7.6% in whites, 9.1% to 13.4% in blacks, and 10.7% to 13% in those of Mexican origin, according to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, which combines interviews and physical examinations, including laboratory analysis of blood samples.

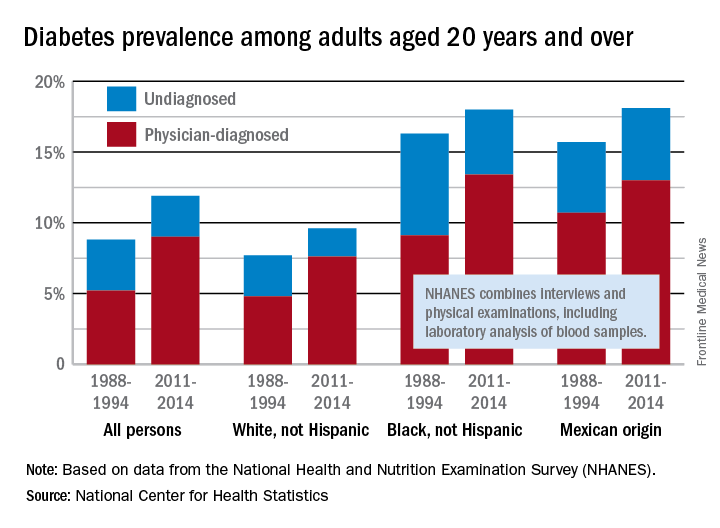

The overall prevalence of diabetes increased 35% from 1988-1994 to 2011-2014 among adults aged 20 years and over, according the National Center for Health Statistics.

During 2011-2014, the age-adjusted prevalence of diabetes was 11.9% in adults aged 20 years and over, compared with 8.8% in 1988-1994. That 35% increase came despite a decrease in undiagnosed diabetes from 3.6% to 2.9% over that time period, which was not enough to offset a jump in physician-diagnosed disease from 5.2% to 9%, the NCHS reported in “Health, United States, 2016.”

Undiagnosed diabetes dropped from 2.9% to 2% in whites and from 7.2% to 4.6% in blacks, but adults of Mexican origin saw a slight increase from 5% in 1988-1994 to 5.1% in 2011-2014. The physician-diagnosed side of the equation rose from 4.8% to 7.6% in whites, 9.1% to 13.4% in blacks, and 10.7% to 13% in those of Mexican origin, according to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, which combines interviews and physical examinations, including laboratory analysis of blood samples.

Insulin degludec decreases rate, severity of hypoglycemic episodes

Insulin degludec decreased both the rate and the severity of hypoglycemic episodes in adults with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, compared with insulin glargine, in two head-to-head trials sponsored by the maker of insulin degludec and reported online July 3 in JAMA.

The two trials had identical randomized double-blind crossover designs. The first involved 501 adults with type 1 diabetes treated at 84 sites in the United States and 6 sites in Poland, and the second involved 721 adults with type 2 diabetes treated at 152 sites in the United States. All the study participants were at risk for hypoglycemia by virtue of experiencing one or more severe hypoglycemic episodes within the preceding year, having moderate chronic renal failure, having a 15-year or longer duration of diabetes, being unaware of their hypoglycemic symptoms, or experiencing severe hypoglycemia within the 3 months preceding baseline.

In both trials, patients were randomized to one type of once-daily insulin for 32 weeks (a 16-week titration period followed by a 16-week maintenance period) and then crossed over to the other type of insulin for 32 weeks. The primary end point in both studies was the rate of overall severe hypoglycemia during the maintenance period. This was defined as either an episode requiring the assistance of another person to administer aid or an episode in which blood glucose measured less than 56 mg/dL.

In the first trial, rates of hypoglycemia were significantly lower with insulin degludec (2,201 episodes per 100 person-years of exposure) than with insulin glargine (2,463 episodes per 100 PYE), demonstrating not just the noninferiority but also the superiority of insulin degludec. In addition, a significantly lower proportion of patients had hypoglycemia with insulin degludec (32.8%) than with insulin glargine (43.1%), said Wendy Lane, MD, of Mountain Diabetes and Endocrine Center, Asheville NC, and her associates.

Regarding the severity of hypoglycemia, the rate of severe episodes was significantly lower with insulin degludec (69 episodes per 100 PYE) than with insulin glargine (92 episodes per 100 PYE). In addition, the proportion of patients who experienced a severe hypoglycemic episode was significantly lower with insulin degludec (10.3%) than with insulin glargine (17.1%).

Both types of insulin reduced hemoglobin A1c levels to 7% or below. Rates of adverse events and serious adverse events were similar between the two study groups, and there were no differences between them in weight change, blood pressure, pulse rate, or laboratory findings, the investigators said (JAMA.2017;318[1]:33-44).

In the second trial, rates of hypoglycemia again were significantly lower with insulin degludec than with insulin glargine (186 vs. 265 episodes per 100 PYE). In addition, the proportion of patients who experienced a severe hypoglycemic episode was 1.6% vs. 2.4%, respectively, said Carol Wysham, MD, of Rockwood Clinic University of Washington, Spokane, and her associates.

As in the first trial, both types of insulin reduced HbA1c levels to the same degree, and rates of adverse events and of serious adverse events were comparable, Dr. Wysham and her associates said (JAMA. 2017;318[1]:45-56).

The dropout rates were similar and higher than expected in both trials, at approximately 20%. Dr. Lane and her associates noted that this may have resulted from “the demanding nature” of the studies, including their 64-week duration; demand for close monitoring of blood glucose; and the requirement of using vials and syringes to maintain treatment blinding, instead of more convenient injector devices.

Both trials were funded by Novo Nordisk, maker of insulin degludec. Dr. Lane reported ties to Novo Nordisk, Insulet Corporation, and Eli Lilly, and her associates reported ties to numerous industry sources. Dr. Wysham reported ties to Novo Nordisk, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen, and Sanofi, and her associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Given the risks associated with hypoglycemia and the concerns about this adverse effect among patients and their families, any basal insulin that reduces the rate of hypoglycemia represents an advance in the treatment of diabetes.

Both studies were limited in that they had relatively high dropout rates of approximately 20% each. However, it appeared that the patients who completed the study were not substantially different from those who dropped out.

These remarks are from an editorial by Elizabeth R. Seaquist, MD, and Lisa S. Chow, MD, that was published along with the research reports (JAMA 2017;318[1]:31-2).

Dr Seaquist reported a variety of sources of funding from Eli Lilly, Locemia, Medtronic, Sanofi, and Zucera; serving as a member of the International Hypoglycemia Study Group; and serving on the examination committee for the American Board of Internal Medicine. Dr. Chow reported research funding from Eli Lilly.

Given the risks associated with hypoglycemia and the concerns about this adverse effect among patients and their families, any basal insulin that reduces the rate of hypoglycemia represents an advance in the treatment of diabetes.

Both studies were limited in that they had relatively high dropout rates of approximately 20% each. However, it appeared that the patients who completed the study were not substantially different from those who dropped out.

These remarks are from an editorial by Elizabeth R. Seaquist, MD, and Lisa S. Chow, MD, that was published along with the research reports (JAMA 2017;318[1]:31-2).

Dr Seaquist reported a variety of sources of funding from Eli Lilly, Locemia, Medtronic, Sanofi, and Zucera; serving as a member of the International Hypoglycemia Study Group; and serving on the examination committee for the American Board of Internal Medicine. Dr. Chow reported research funding from Eli Lilly.

Given the risks associated with hypoglycemia and the concerns about this adverse effect among patients and their families, any basal insulin that reduces the rate of hypoglycemia represents an advance in the treatment of diabetes.

Both studies were limited in that they had relatively high dropout rates of approximately 20% each. However, it appeared that the patients who completed the study were not substantially different from those who dropped out.

These remarks are from an editorial by Elizabeth R. Seaquist, MD, and Lisa S. Chow, MD, that was published along with the research reports (JAMA 2017;318[1]:31-2).

Dr Seaquist reported a variety of sources of funding from Eli Lilly, Locemia, Medtronic, Sanofi, and Zucera; serving as a member of the International Hypoglycemia Study Group; and serving on the examination committee for the American Board of Internal Medicine. Dr. Chow reported research funding from Eli Lilly.

Insulin degludec decreased both the rate and the severity of hypoglycemic episodes in adults with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, compared with insulin glargine, in two head-to-head trials sponsored by the maker of insulin degludec and reported online July 3 in JAMA.

The two trials had identical randomized double-blind crossover designs. The first involved 501 adults with type 1 diabetes treated at 84 sites in the United States and 6 sites in Poland, and the second involved 721 adults with type 2 diabetes treated at 152 sites in the United States. All the study participants were at risk for hypoglycemia by virtue of experiencing one or more severe hypoglycemic episodes within the preceding year, having moderate chronic renal failure, having a 15-year or longer duration of diabetes, being unaware of their hypoglycemic symptoms, or experiencing severe hypoglycemia within the 3 months preceding baseline.

In both trials, patients were randomized to one type of once-daily insulin for 32 weeks (a 16-week titration period followed by a 16-week maintenance period) and then crossed over to the other type of insulin for 32 weeks. The primary end point in both studies was the rate of overall severe hypoglycemia during the maintenance period. This was defined as either an episode requiring the assistance of another person to administer aid or an episode in which blood glucose measured less than 56 mg/dL.

In the first trial, rates of hypoglycemia were significantly lower with insulin degludec (2,201 episodes per 100 person-years of exposure) than with insulin glargine (2,463 episodes per 100 PYE), demonstrating not just the noninferiority but also the superiority of insulin degludec. In addition, a significantly lower proportion of patients had hypoglycemia with insulin degludec (32.8%) than with insulin glargine (43.1%), said Wendy Lane, MD, of Mountain Diabetes and Endocrine Center, Asheville NC, and her associates.

Regarding the severity of hypoglycemia, the rate of severe episodes was significantly lower with insulin degludec (69 episodes per 100 PYE) than with insulin glargine (92 episodes per 100 PYE). In addition, the proportion of patients who experienced a severe hypoglycemic episode was significantly lower with insulin degludec (10.3%) than with insulin glargine (17.1%).

Both types of insulin reduced hemoglobin A1c levels to 7% or below. Rates of adverse events and serious adverse events were similar between the two study groups, and there were no differences between them in weight change, blood pressure, pulse rate, or laboratory findings, the investigators said (JAMA.2017;318[1]:33-44).

In the second trial, rates of hypoglycemia again were significantly lower with insulin degludec than with insulin glargine (186 vs. 265 episodes per 100 PYE). In addition, the proportion of patients who experienced a severe hypoglycemic episode was 1.6% vs. 2.4%, respectively, said Carol Wysham, MD, of Rockwood Clinic University of Washington, Spokane, and her associates.

As in the first trial, both types of insulin reduced HbA1c levels to the same degree, and rates of adverse events and of serious adverse events were comparable, Dr. Wysham and her associates said (JAMA. 2017;318[1]:45-56).

The dropout rates were similar and higher than expected in both trials, at approximately 20%. Dr. Lane and her associates noted that this may have resulted from “the demanding nature” of the studies, including their 64-week duration; demand for close monitoring of blood glucose; and the requirement of using vials and syringes to maintain treatment blinding, instead of more convenient injector devices.

Both trials were funded by Novo Nordisk, maker of insulin degludec. Dr. Lane reported ties to Novo Nordisk, Insulet Corporation, and Eli Lilly, and her associates reported ties to numerous industry sources. Dr. Wysham reported ties to Novo Nordisk, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen, and Sanofi, and her associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Insulin degludec decreased both the rate and the severity of hypoglycemic episodes in adults with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, compared with insulin glargine, in two head-to-head trials sponsored by the maker of insulin degludec and reported online July 3 in JAMA.

The two trials had identical randomized double-blind crossover designs. The first involved 501 adults with type 1 diabetes treated at 84 sites in the United States and 6 sites in Poland, and the second involved 721 adults with type 2 diabetes treated at 152 sites in the United States. All the study participants were at risk for hypoglycemia by virtue of experiencing one or more severe hypoglycemic episodes within the preceding year, having moderate chronic renal failure, having a 15-year or longer duration of diabetes, being unaware of their hypoglycemic symptoms, or experiencing severe hypoglycemia within the 3 months preceding baseline.

In both trials, patients were randomized to one type of once-daily insulin for 32 weeks (a 16-week titration period followed by a 16-week maintenance period) and then crossed over to the other type of insulin for 32 weeks. The primary end point in both studies was the rate of overall severe hypoglycemia during the maintenance period. This was defined as either an episode requiring the assistance of another person to administer aid or an episode in which blood glucose measured less than 56 mg/dL.

In the first trial, rates of hypoglycemia were significantly lower with insulin degludec (2,201 episodes per 100 person-years of exposure) than with insulin glargine (2,463 episodes per 100 PYE), demonstrating not just the noninferiority but also the superiority of insulin degludec. In addition, a significantly lower proportion of patients had hypoglycemia with insulin degludec (32.8%) than with insulin glargine (43.1%), said Wendy Lane, MD, of Mountain Diabetes and Endocrine Center, Asheville NC, and her associates.

Regarding the severity of hypoglycemia, the rate of severe episodes was significantly lower with insulin degludec (69 episodes per 100 PYE) than with insulin glargine (92 episodes per 100 PYE). In addition, the proportion of patients who experienced a severe hypoglycemic episode was significantly lower with insulin degludec (10.3%) than with insulin glargine (17.1%).

Both types of insulin reduced hemoglobin A1c levels to 7% or below. Rates of adverse events and serious adverse events were similar between the two study groups, and there were no differences between them in weight change, blood pressure, pulse rate, or laboratory findings, the investigators said (JAMA.2017;318[1]:33-44).

In the second trial, rates of hypoglycemia again were significantly lower with insulin degludec than with insulin glargine (186 vs. 265 episodes per 100 PYE). In addition, the proportion of patients who experienced a severe hypoglycemic episode was 1.6% vs. 2.4%, respectively, said Carol Wysham, MD, of Rockwood Clinic University of Washington, Spokane, and her associates.

As in the first trial, both types of insulin reduced HbA1c levels to the same degree, and rates of adverse events and of serious adverse events were comparable, Dr. Wysham and her associates said (JAMA. 2017;318[1]:45-56).

The dropout rates were similar and higher than expected in both trials, at approximately 20%. Dr. Lane and her associates noted that this may have resulted from “the demanding nature” of the studies, including their 64-week duration; demand for close monitoring of blood glucose; and the requirement of using vials and syringes to maintain treatment blinding, instead of more convenient injector devices.

Both trials were funded by Novo Nordisk, maker of insulin degludec. Dr. Lane reported ties to Novo Nordisk, Insulet Corporation, and Eli Lilly, and her associates reported ties to numerous industry sources. Dr. Wysham reported ties to Novo Nordisk, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen, and Sanofi, and her associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Insulin degludec decreases the rate and severity of hypoglycemic episodes in adults with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, compared with insulin glargine.

Major finding: Rates of hypoglycemia were significantly lower with insulin degludec (2,201 episodes per 100 person-years of exposure) than with insulin glargine (2,463 episodes per 100 PYE) in type 1 diabetes and in type 2 diabetes (185.6 vs. 265.4 episodes per 100 PYE).

Data source: Two separate multicenter, randomized, double-blind crossover trials involving 501 adults with type 1 and 721 with type 2 diabetes.

Disclosures: Both trials were funded by Novo Nordisk, maker of insulin degludec. Dr. Lane reported ties to Novo Nordisk, Insulet Corporation, and Eli Lilly, and her associates reported ties to numerous industry sources. Dr. Wysham reported ties to Novo Nordisk, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen, and Sanofi, and her associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Red flags for type 2 diabetes seen 25 years before diagnosis

SAN DIEGO – Based on their analysis of a cohort of more than half a million people, Swedish researchers now believe that mildly elevated fasting plasma glucose and triglyceride levels could indicate an increased risk for type 2 diabetes a quarter-century before diagnosis.

“Previous studies have shown that risk factors for type 2 diabetes, including obesity and elevated fasting glucose, may be present up to 10 years before disease onset. Our study extends this period to more than 20 years before diagnosis,” said the study’s lead author Håkan Malmström, PhD, an epidemiologist with the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm. “Even small elevations in subjects over time early in life may be important to recognize, in particular for people who are overweight or obese.” The study findings were presented in an oral presentation at the scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The researchers identified 47,997 new type 2 diabetes cases in a Swedish cohort of 537,119 people tracked from 1985-2012. For each case, they compared risk factors from clinical examinations performed from 1985-1996 with those of five matched controls.

They found that on average, several risk factors were more common among individuals with type 2 diabetes, compared with the matched controls “many years before the diagnosis,” Dr. Malmström said. “In particular, BMI [body mass index], fasting triglycerides, fasting glucose, the apo B/apo A-I ratio and inflammatory markers were increased up to 25 years before the diagnosis.”

For example, 25 years before diagnosis, mean fasting plasma glucose in the type 2 diabetes group was higher than controls at 90 mg/dL vs. 86 mg/dL, respectively. By 10 years before diagnosis, that gap had widened to 98 mg/dL vs. 88 mg/dL. At 1 year before diagnosis, the levels were 106 mg/dl vs. 90 mg/dL.

As for fasting triglycerides, high levels earlier in life appeared to be especially risky: Individuals with levels over 124 mg/dL were more likely to develop type 2 diabetes 20 years later, even if they weren’t overweight or had elevated mean fasting glucose levels.

At 25 years before diagnosis, the type 2 diabetes group had mean fasting triglyceride levels of 120 mg/dL vs. 89 mg/dL in the control group. And at 1 year before diagnosis, the difference had widened to 146 mg/dL vs. 106 mg/dL.

Researchers found signs of higher levels of fructosamine – a marker of glycemic levels over an extended period of time (2-3 weeks) – at about 15 years before diagnosis. According to Dr. Malmström, this finding suggests that “glucose metabolism was starting to become more disturbed later than the changes in fasting glucose, but still many years before the type 2 diabetes diagnosis.”

He speculated that early signs of type 2 diabetes revealed by the study are related to genetic predisposition. “The risk of developing the disease presents early with increased BMI and dyslipidemia, which in turn leads to successively decreased insulin sensitivity,” he said.

One step for future research, he added, would be to “elaborate on these early changes in risk factors and create a risk score based on a few easily available factors in clinical settings.”

The study was funded by Sweden’s Gunnar and Ingmar Jungner Foundation for Laboratory Medicine. Dr. Malmström reported no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Based on their analysis of a cohort of more than half a million people, Swedish researchers now believe that mildly elevated fasting plasma glucose and triglyceride levels could indicate an increased risk for type 2 diabetes a quarter-century before diagnosis.

“Previous studies have shown that risk factors for type 2 diabetes, including obesity and elevated fasting glucose, may be present up to 10 years before disease onset. Our study extends this period to more than 20 years before diagnosis,” said the study’s lead author Håkan Malmström, PhD, an epidemiologist with the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm. “Even small elevations in subjects over time early in life may be important to recognize, in particular for people who are overweight or obese.” The study findings were presented in an oral presentation at the scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The researchers identified 47,997 new type 2 diabetes cases in a Swedish cohort of 537,119 people tracked from 1985-2012. For each case, they compared risk factors from clinical examinations performed from 1985-1996 with those of five matched controls.

They found that on average, several risk factors were more common among individuals with type 2 diabetes, compared with the matched controls “many years before the diagnosis,” Dr. Malmström said. “In particular, BMI [body mass index], fasting triglycerides, fasting glucose, the apo B/apo A-I ratio and inflammatory markers were increased up to 25 years before the diagnosis.”

For example, 25 years before diagnosis, mean fasting plasma glucose in the type 2 diabetes group was higher than controls at 90 mg/dL vs. 86 mg/dL, respectively. By 10 years before diagnosis, that gap had widened to 98 mg/dL vs. 88 mg/dL. At 1 year before diagnosis, the levels were 106 mg/dl vs. 90 mg/dL.

As for fasting triglycerides, high levels earlier in life appeared to be especially risky: Individuals with levels over 124 mg/dL were more likely to develop type 2 diabetes 20 years later, even if they weren’t overweight or had elevated mean fasting glucose levels.

At 25 years before diagnosis, the type 2 diabetes group had mean fasting triglyceride levels of 120 mg/dL vs. 89 mg/dL in the control group. And at 1 year before diagnosis, the difference had widened to 146 mg/dL vs. 106 mg/dL.

Researchers found signs of higher levels of fructosamine – a marker of glycemic levels over an extended period of time (2-3 weeks) – at about 15 years before diagnosis. According to Dr. Malmström, this finding suggests that “glucose metabolism was starting to become more disturbed later than the changes in fasting glucose, but still many years before the type 2 diabetes diagnosis.”

He speculated that early signs of type 2 diabetes revealed by the study are related to genetic predisposition. “The risk of developing the disease presents early with increased BMI and dyslipidemia, which in turn leads to successively decreased insulin sensitivity,” he said.

One step for future research, he added, would be to “elaborate on these early changes in risk factors and create a risk score based on a few easily available factors in clinical settings.”

The study was funded by Sweden’s Gunnar and Ingmar Jungner Foundation for Laboratory Medicine. Dr. Malmström reported no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Based on their analysis of a cohort of more than half a million people, Swedish researchers now believe that mildly elevated fasting plasma glucose and triglyceride levels could indicate an increased risk for type 2 diabetes a quarter-century before diagnosis.

“Previous studies have shown that risk factors for type 2 diabetes, including obesity and elevated fasting glucose, may be present up to 10 years before disease onset. Our study extends this period to more than 20 years before diagnosis,” said the study’s lead author Håkan Malmström, PhD, an epidemiologist with the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm. “Even small elevations in subjects over time early in life may be important to recognize, in particular for people who are overweight or obese.” The study findings were presented in an oral presentation at the scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The researchers identified 47,997 new type 2 diabetes cases in a Swedish cohort of 537,119 people tracked from 1985-2012. For each case, they compared risk factors from clinical examinations performed from 1985-1996 with those of five matched controls.

They found that on average, several risk factors were more common among individuals with type 2 diabetes, compared with the matched controls “many years before the diagnosis,” Dr. Malmström said. “In particular, BMI [body mass index], fasting triglycerides, fasting glucose, the apo B/apo A-I ratio and inflammatory markers were increased up to 25 years before the diagnosis.”

For example, 25 years before diagnosis, mean fasting plasma glucose in the type 2 diabetes group was higher than controls at 90 mg/dL vs. 86 mg/dL, respectively. By 10 years before diagnosis, that gap had widened to 98 mg/dL vs. 88 mg/dL. At 1 year before diagnosis, the levels were 106 mg/dl vs. 90 mg/dL.

As for fasting triglycerides, high levels earlier in life appeared to be especially risky: Individuals with levels over 124 mg/dL were more likely to develop type 2 diabetes 20 years later, even if they weren’t overweight or had elevated mean fasting glucose levels.

At 25 years before diagnosis, the type 2 diabetes group had mean fasting triglyceride levels of 120 mg/dL vs. 89 mg/dL in the control group. And at 1 year before diagnosis, the difference had widened to 146 mg/dL vs. 106 mg/dL.

Researchers found signs of higher levels of fructosamine – a marker of glycemic levels over an extended period of time (2-3 weeks) – at about 15 years before diagnosis. According to Dr. Malmström, this finding suggests that “glucose metabolism was starting to become more disturbed later than the changes in fasting glucose, but still many years before the type 2 diabetes diagnosis.”

He speculated that early signs of type 2 diabetes revealed by the study are related to genetic predisposition. “The risk of developing the disease presents early with increased BMI and dyslipidemia, which in turn leads to successively decreased insulin sensitivity,” he said.

One step for future research, he added, would be to “elaborate on these early changes in risk factors and create a risk score based on a few easily available factors in clinical settings.”

The study was funded by Sweden’s Gunnar and Ingmar Jungner Foundation for Laboratory Medicine. Dr. Malmström reported no relevant disclosures.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

LEADER post hoc analysis: Mechanism behind liraglutide’s cardioprotective effects unclear

SAN DIEGO – The glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist liraglutide significantly reduced the risk of initial and recurrent major cardiovascular events in high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes, according to new posthoc analyses from the LEADER (Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results) trial.

Liraglutide’s cardioprotective effect did not depend on baseline use of insulin or cardiovascular medications, nor whether patients started insulin, sulfonylureas, or thiazolidinediones, or developed severe hypoglycemia during the trial, Richard Pratley, MD, told a packed auditorium at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “It appears unlikely that the cardiovascular risk reduction with liraglutide can be fully explained by the observed differences in hemoglobin A1c, body weight, systolic blood pressure, and lipids,” he said. Experts have proposed several pathways, “but the bottom line is, in humans, we don’t know the mechanism for liraglutide’s benefit.”

In LEADER, 9,340 older patients with suboptimally controlled type 2 diabetes and additional cardiovascular risk factors were randomly assigned to liraglutide or placebo once daily. Patients were typically male, obese, and hypertensive, and about 18% had prior heart failure. Topline results reported last year at ADA included a 13% reduction in the rate of initial cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and non-fatal stroke in the liraglutide group, compared with the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.78 to 0.97).

The new posthoc analyses indicate that liraglutide also prevents both initial and recurrent cardiovascular events (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.78 to 0.95) and that its cardioprotective effect spans subgroups of patients stratified according to whether they were on insulin, beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, statins, and platelet aggregation inhibitors at baseline, said Dr. Pratley, senior investigator at the Translational Research Institute for Metabolism and Diabetes, and medical director of the Florida Hospital Diabetes Institute, Orlando.

Liraglutide also reduced cardiovascular events to about the same extent regardless of whether patients later started insulin, sulfonylureas, or thiazolidinediones or developed severe hypoglycemia.

Such findings signal a fundamental shift in diabetes care, commented Steven Nissen, MD, chair of the department of cardiovascular medicine, at the Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio. For decades, patients and clinicians lacked diabetes outcomes trials, and “it took three successive shockwaves to awaken the medical community from its 50-year slumber.”

The wake-up call started when Dr. Nissen and his associates linked muraglitazar (JAMA. 2005 Nov 23;294[20]:2581-6) and rosiglitazone (N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2457-71) to an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events. This continued when researchers found that targeting glycated hemoglobin levels below 6.0% increased the risk of death in patients with type 2 diabetes, in the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial (N Engl J Med 2008; 358:2545-59).

In response, the Food and Drug Administration began requiring cardiovascular outcomes trials before and after approving new diabetes drugs. “The result has been a new era of research” that has revealed uneven outcomes and a lack of uniform class effects, Dr. Nissen said.

For example, lixisenatide and long-acting exenatide are GLP-1 receptor agonists like liraglutide, but neither of these two drugs were found to prevent cardiovascular outcomes compared with placebo. In addition, the DPP-4 inhibitors “provide no meaningful outcome benefits, minimal glucose lowering, and potential harm at a high cost of about $400 per month,” he said.

This class has suffered “three disappointments,” he added. He referred to findings that alogliptin and sitagliptin did not reduce cardiovascular events compared with placebo in the EXAMINE trial (N Engl J Med 2013; 369:1327-35) and TECOS trial (N Engl J Med 2015; 373:232-42), respectively, while the SAVOR-TIMI 53 trial linked saxagliptin to an increased risk of hospitalization for heart failure (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.51).

In contrast, the sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor empagliflozin reduced the rate of cardiovascular death, stroke, and MI by about 14% in the EMPA-REG trial (N Engl J Med 2015;373:2117-28).

Based on the LEADER results, the Food and Drug Administration’s Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee voted 17-2 supporting a new cardiovascular indication for liraglutide in type 2 diabetes, at a meeting in June 2017.

“After 60 years of stagnation, we are now witnessing a new era in the pharmacological management of type 2 diabetes, which is allowing a choice of therapies based on actual clinical outcomes – risks and benefits – rather than a surrogate biochemical marker like glucose levels,” Dr. Nissen said.

But current ADA recommendations “only weakly reflect contemporary knowledge,” he added. Although these guidelines do recommend considering empagliflozin or liraglutide for patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and “long-standing, suboptimally controlled type 2 diabetes,” their guidance on dual therapy does not reflect diverse cardiovascular outcomes data within and between classes, he said. “Just as we observed with statins, adoption of pivotal results is often just too slow.”

Integrating knowledge into practice will require close collaboration between cardiovascular and diabetes practitioners and “leadership from ADA to overcome residual inertia from decades of complacency,” he commented.

Dr. Pratley disclosed ties to AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Company, and several other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Nissen disclosed research support from Novo Nordisk, Abbvie, Eli Lilly, and several other pharmaceutical companies, and travel support from Novo Nordisk.

SAN DIEGO – The glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist liraglutide significantly reduced the risk of initial and recurrent major cardiovascular events in high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes, according to new posthoc analyses from the LEADER (Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results) trial.

Liraglutide’s cardioprotective effect did not depend on baseline use of insulin or cardiovascular medications, nor whether patients started insulin, sulfonylureas, or thiazolidinediones, or developed severe hypoglycemia during the trial, Richard Pratley, MD, told a packed auditorium at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “It appears unlikely that the cardiovascular risk reduction with liraglutide can be fully explained by the observed differences in hemoglobin A1c, body weight, systolic blood pressure, and lipids,” he said. Experts have proposed several pathways, “but the bottom line is, in humans, we don’t know the mechanism for liraglutide’s benefit.”

In LEADER, 9,340 older patients with suboptimally controlled type 2 diabetes and additional cardiovascular risk factors were randomly assigned to liraglutide or placebo once daily. Patients were typically male, obese, and hypertensive, and about 18% had prior heart failure. Topline results reported last year at ADA included a 13% reduction in the rate of initial cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and non-fatal stroke in the liraglutide group, compared with the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.78 to 0.97).

The new posthoc analyses indicate that liraglutide also prevents both initial and recurrent cardiovascular events (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.78 to 0.95) and that its cardioprotective effect spans subgroups of patients stratified according to whether they were on insulin, beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, statins, and platelet aggregation inhibitors at baseline, said Dr. Pratley, senior investigator at the Translational Research Institute for Metabolism and Diabetes, and medical director of the Florida Hospital Diabetes Institute, Orlando.

Liraglutide also reduced cardiovascular events to about the same extent regardless of whether patients later started insulin, sulfonylureas, or thiazolidinediones or developed severe hypoglycemia.

Such findings signal a fundamental shift in diabetes care, commented Steven Nissen, MD, chair of the department of cardiovascular medicine, at the Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio. For decades, patients and clinicians lacked diabetes outcomes trials, and “it took three successive shockwaves to awaken the medical community from its 50-year slumber.”

The wake-up call started when Dr. Nissen and his associates linked muraglitazar (JAMA. 2005 Nov 23;294[20]:2581-6) and rosiglitazone (N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2457-71) to an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events. This continued when researchers found that targeting glycated hemoglobin levels below 6.0% increased the risk of death in patients with type 2 diabetes, in the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial (N Engl J Med 2008; 358:2545-59).

In response, the Food and Drug Administration began requiring cardiovascular outcomes trials before and after approving new diabetes drugs. “The result has been a new era of research” that has revealed uneven outcomes and a lack of uniform class effects, Dr. Nissen said.

For example, lixisenatide and long-acting exenatide are GLP-1 receptor agonists like liraglutide, but neither of these two drugs were found to prevent cardiovascular outcomes compared with placebo. In addition, the DPP-4 inhibitors “provide no meaningful outcome benefits, minimal glucose lowering, and potential harm at a high cost of about $400 per month,” he said.

This class has suffered “three disappointments,” he added. He referred to findings that alogliptin and sitagliptin did not reduce cardiovascular events compared with placebo in the EXAMINE trial (N Engl J Med 2013; 369:1327-35) and TECOS trial (N Engl J Med 2015; 373:232-42), respectively, while the SAVOR-TIMI 53 trial linked saxagliptin to an increased risk of hospitalization for heart failure (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.51).

In contrast, the sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor empagliflozin reduced the rate of cardiovascular death, stroke, and MI by about 14% in the EMPA-REG trial (N Engl J Med 2015;373:2117-28).

Based on the LEADER results, the Food and Drug Administration’s Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee voted 17-2 supporting a new cardiovascular indication for liraglutide in type 2 diabetes, at a meeting in June 2017.

“After 60 years of stagnation, we are now witnessing a new era in the pharmacological management of type 2 diabetes, which is allowing a choice of therapies based on actual clinical outcomes – risks and benefits – rather than a surrogate biochemical marker like glucose levels,” Dr. Nissen said.

But current ADA recommendations “only weakly reflect contemporary knowledge,” he added. Although these guidelines do recommend considering empagliflozin or liraglutide for patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and “long-standing, suboptimally controlled type 2 diabetes,” their guidance on dual therapy does not reflect diverse cardiovascular outcomes data within and between classes, he said. “Just as we observed with statins, adoption of pivotal results is often just too slow.”

Integrating knowledge into practice will require close collaboration between cardiovascular and diabetes practitioners and “leadership from ADA to overcome residual inertia from decades of complacency,” he commented.

Dr. Pratley disclosed ties to AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Company, and several other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Nissen disclosed research support from Novo Nordisk, Abbvie, Eli Lilly, and several other pharmaceutical companies, and travel support from Novo Nordisk.

SAN DIEGO – The glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist liraglutide significantly reduced the risk of initial and recurrent major cardiovascular events in high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes, according to new posthoc analyses from the LEADER (Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results) trial.

Liraglutide’s cardioprotective effect did not depend on baseline use of insulin or cardiovascular medications, nor whether patients started insulin, sulfonylureas, or thiazolidinediones, or developed severe hypoglycemia during the trial, Richard Pratley, MD, told a packed auditorium at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “It appears unlikely that the cardiovascular risk reduction with liraglutide can be fully explained by the observed differences in hemoglobin A1c, body weight, systolic blood pressure, and lipids,” he said. Experts have proposed several pathways, “but the bottom line is, in humans, we don’t know the mechanism for liraglutide’s benefit.”

In LEADER, 9,340 older patients with suboptimally controlled type 2 diabetes and additional cardiovascular risk factors were randomly assigned to liraglutide or placebo once daily. Patients were typically male, obese, and hypertensive, and about 18% had prior heart failure. Topline results reported last year at ADA included a 13% reduction in the rate of initial cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and non-fatal stroke in the liraglutide group, compared with the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.78 to 0.97).

The new posthoc analyses indicate that liraglutide also prevents both initial and recurrent cardiovascular events (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.78 to 0.95) and that its cardioprotective effect spans subgroups of patients stratified according to whether they were on insulin, beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, statins, and platelet aggregation inhibitors at baseline, said Dr. Pratley, senior investigator at the Translational Research Institute for Metabolism and Diabetes, and medical director of the Florida Hospital Diabetes Institute, Orlando.

Liraglutide also reduced cardiovascular events to about the same extent regardless of whether patients later started insulin, sulfonylureas, or thiazolidinediones or developed severe hypoglycemia.

Such findings signal a fundamental shift in diabetes care, commented Steven Nissen, MD, chair of the department of cardiovascular medicine, at the Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio. For decades, patients and clinicians lacked diabetes outcomes trials, and “it took three successive shockwaves to awaken the medical community from its 50-year slumber.”

The wake-up call started when Dr. Nissen and his associates linked muraglitazar (JAMA. 2005 Nov 23;294[20]:2581-6) and rosiglitazone (N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2457-71) to an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events. This continued when researchers found that targeting glycated hemoglobin levels below 6.0% increased the risk of death in patients with type 2 diabetes, in the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial (N Engl J Med 2008; 358:2545-59).

In response, the Food and Drug Administration began requiring cardiovascular outcomes trials before and after approving new diabetes drugs. “The result has been a new era of research” that has revealed uneven outcomes and a lack of uniform class effects, Dr. Nissen said.

For example, lixisenatide and long-acting exenatide are GLP-1 receptor agonists like liraglutide, but neither of these two drugs were found to prevent cardiovascular outcomes compared with placebo. In addition, the DPP-4 inhibitors “provide no meaningful outcome benefits, minimal glucose lowering, and potential harm at a high cost of about $400 per month,” he said.

This class has suffered “three disappointments,” he added. He referred to findings that alogliptin and sitagliptin did not reduce cardiovascular events compared with placebo in the EXAMINE trial (N Engl J Med 2013; 369:1327-35) and TECOS trial (N Engl J Med 2015; 373:232-42), respectively, while the SAVOR-TIMI 53 trial linked saxagliptin to an increased risk of hospitalization for heart failure (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.51).

In contrast, the sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor empagliflozin reduced the rate of cardiovascular death, stroke, and MI by about 14% in the EMPA-REG trial (N Engl J Med 2015;373:2117-28).

Based on the LEADER results, the Food and Drug Administration’s Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee voted 17-2 supporting a new cardiovascular indication for liraglutide in type 2 diabetes, at a meeting in June 2017.

“After 60 years of stagnation, we are now witnessing a new era in the pharmacological management of type 2 diabetes, which is allowing a choice of therapies based on actual clinical outcomes – risks and benefits – rather than a surrogate biochemical marker like glucose levels,” Dr. Nissen said.

But current ADA recommendations “only weakly reflect contemporary knowledge,” he added. Although these guidelines do recommend considering empagliflozin or liraglutide for patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and “long-standing, suboptimally controlled type 2 diabetes,” their guidance on dual therapy does not reflect diverse cardiovascular outcomes data within and between classes, he said. “Just as we observed with statins, adoption of pivotal results is often just too slow.”

Integrating knowledge into practice will require close collaboration between cardiovascular and diabetes practitioners and “leadership from ADA to overcome residual inertia from decades of complacency,” he commented.

Dr. Pratley disclosed ties to AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Company, and several other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Nissen disclosed research support from Novo Nordisk, Abbvie, Eli Lilly, and several other pharmaceutical companies, and travel support from Novo Nordisk.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Oral insulin matches glargine in phase II trial

SAN DIEGO – In an industry-funded phase II trial, researchers say they’ve shown for the first time that oral basal insulin tablets can safely decrease plasma glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM).

“Oral basal insulin appears safe and efficacious in insulin-naive patients with type 2 [diabetes] insufficiently controlled with medications. It improves glycemic control to a similar extent as does glargine,” said study lead author Leona Plum-Mörschel, MD, CEO of the German clinical research organization Profil Mainz, in an oral presentation at the scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. A statement from Novo Nordisk, the maker of the investigational medication, says the company discontinued development of the product due to its low bioavailability and concerns about the costs of producing it.

According to Dr. Plum-Mörschel, researchers have been searching for an oral insulin treatment for almost a century without success.

In the new phase IIa study, researchers tested a basal insulin analog tablet called OI338GT. It uses a technology platform called Gipet by Merrion Pharmaceuticals that aims to boost the absorption of injectable drugs when they are given in oral form.

Researchers recruited 50 insulin-naive patients with T2DM (mean age 61 ± 7 years, mean BMI 30.5 ± 3.7 kg/m²) whose diabetes wasn’t properly controlled by metformin by itself or in conjunction with other drugs. All had hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels between 7% and 10%.

The patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to the investigational oral medication or subcutaneous insulin glargine (IGlar). They took the drugs once a day for 8 weeks in addition to their existing drug regimen.

The researchers increased the doses on a weekly basis with a goal of reaching fasting plasma glucose (FPG) of 80-126 mg/dL. Daily doses of the investigational drug (nmol/kg) began at a mean 30 ± 11 and reached 114 ± 51 by the end of the study; daily mean doses of IGlar (U/kg) began at 0.11 ± 0.03 and ended at 0.33 ± 0.15.

Both medications boosted glycemic control at about the same level, the researchers report, based on levels of FPG, HbA1c, and fructosamine levels at 8 weeks.

Mean FPG levels (mg/dL), the primary endpoint, declined in investigational medication and IGlar from 175 ± 50 and 164 ± 31, respectively, at baseline to 129 ± 33 and 121 ± 17, respectively, at end of treatment. The treatment difference (investigational medication – IGlar) was 5.2 mg/dL [–8.8;19.1], 95% CI, P = .4567.

In a post hoc analysis, mean HbA1c levels declined from 8.1 ± 0.6% and 8.2 ± 0.8% at baseline in investigational medication and IGlar, respectively, to 7.3 ± 0.8% and 7.1 ± 0.6%, respectively. The treatment difference (investigational medication – IGlar) was 0.30% [–0.03;0.63], 95% CI, P = .0774.

In another post hoc analysis, mean fructosamine levels (micromol/L) dipped from 275 ± 44 and 273 ± 50 in investigational medication and IGlar, respectively, to 235 ± 45 and 223 ± 34, respectively. The treatment difference (investigational medication – IGlar)

was 9.6 micromol/L [–11.7;30.9], 95% CI, P = .3700. None of the patients reported severe hypoglycemia. In the investigational group, 6 subjects suffered 7 events of hypoglycemia that emerged or worsened during treatment; 11 events occurred in 6 subjects in the IGlar group. Researchers report similar levels of adverse events in both groups: 31 in 15 patients treated with the investigational drug and 37 in 17 patients treated with IGlar.

“After termination of treatment, plasma glucose rebounded to baseline levels within a couple of weeks,” Dr. Plum-Mörschel said.

Novo Nordisk funded the trial. Dr. Plum-Mörschel reports no disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – In an industry-funded phase II trial, researchers say they’ve shown for the first time that oral basal insulin tablets can safely decrease plasma glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM).

“Oral basal insulin appears safe and efficacious in insulin-naive patients with type 2 [diabetes] insufficiently controlled with medications. It improves glycemic control to a similar extent as does glargine,” said study lead author Leona Plum-Mörschel, MD, CEO of the German clinical research organization Profil Mainz, in an oral presentation at the scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. A statement from Novo Nordisk, the maker of the investigational medication, says the company discontinued development of the product due to its low bioavailability and concerns about the costs of producing it.

According to Dr. Plum-Mörschel, researchers have been searching for an oral insulin treatment for almost a century without success.

In the new phase IIa study, researchers tested a basal insulin analog tablet called OI338GT. It uses a technology platform called Gipet by Merrion Pharmaceuticals that aims to boost the absorption of injectable drugs when they are given in oral form.

Researchers recruited 50 insulin-naive patients with T2DM (mean age 61 ± 7 years, mean BMI 30.5 ± 3.7 kg/m²) whose diabetes wasn’t properly controlled by metformin by itself or in conjunction with other drugs. All had hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels between 7% and 10%.

The patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to the investigational oral medication or subcutaneous insulin glargine (IGlar). They took the drugs once a day for 8 weeks in addition to their existing drug regimen.

The researchers increased the doses on a weekly basis with a goal of reaching fasting plasma glucose (FPG) of 80-126 mg/dL. Daily doses of the investigational drug (nmol/kg) began at a mean 30 ± 11 and reached 114 ± 51 by the end of the study; daily mean doses of IGlar (U/kg) began at 0.11 ± 0.03 and ended at 0.33 ± 0.15.

Both medications boosted glycemic control at about the same level, the researchers report, based on levels of FPG, HbA1c, and fructosamine levels at 8 weeks.

Mean FPG levels (mg/dL), the primary endpoint, declined in investigational medication and IGlar from 175 ± 50 and 164 ± 31, respectively, at baseline to 129 ± 33 and 121 ± 17, respectively, at end of treatment. The treatment difference (investigational medication – IGlar) was 5.2 mg/dL [–8.8;19.1], 95% CI, P = .4567.

In a post hoc analysis, mean HbA1c levels declined from 8.1 ± 0.6% and 8.2 ± 0.8% at baseline in investigational medication and IGlar, respectively, to 7.3 ± 0.8% and 7.1 ± 0.6%, respectively. The treatment difference (investigational medication – IGlar) was 0.30% [–0.03;0.63], 95% CI, P = .0774.

In another post hoc analysis, mean fructosamine levels (micromol/L) dipped from 275 ± 44 and 273 ± 50 in investigational medication and IGlar, respectively, to 235 ± 45 and 223 ± 34, respectively. The treatment difference (investigational medication – IGlar)

was 9.6 micromol/L [–11.7;30.9], 95% CI, P = .3700. None of the patients reported severe hypoglycemia. In the investigational group, 6 subjects suffered 7 events of hypoglycemia that emerged or worsened during treatment; 11 events occurred in 6 subjects in the IGlar group. Researchers report similar levels of adverse events in both groups: 31 in 15 patients treated with the investigational drug and 37 in 17 patients treated with IGlar.

“After termination of treatment, plasma glucose rebounded to baseline levels within a couple of weeks,” Dr. Plum-Mörschel said.

Novo Nordisk funded the trial. Dr. Plum-Mörschel reports no disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – In an industry-funded phase II trial, researchers say they’ve shown for the first time that oral basal insulin tablets can safely decrease plasma glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM).

“Oral basal insulin appears safe and efficacious in insulin-naive patients with type 2 [diabetes] insufficiently controlled with medications. It improves glycemic control to a similar extent as does glargine,” said study lead author Leona Plum-Mörschel, MD, CEO of the German clinical research organization Profil Mainz, in an oral presentation at the scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. A statement from Novo Nordisk, the maker of the investigational medication, says the company discontinued development of the product due to its low bioavailability and concerns about the costs of producing it.

According to Dr. Plum-Mörschel, researchers have been searching for an oral insulin treatment for almost a century without success.

In the new phase IIa study, researchers tested a basal insulin analog tablet called OI338GT. It uses a technology platform called Gipet by Merrion Pharmaceuticals that aims to boost the absorption of injectable drugs when they are given in oral form.

Researchers recruited 50 insulin-naive patients with T2DM (mean age 61 ± 7 years, mean BMI 30.5 ± 3.7 kg/m²) whose diabetes wasn’t properly controlled by metformin by itself or in conjunction with other drugs. All had hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels between 7% and 10%.

The patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to the investigational oral medication or subcutaneous insulin glargine (IGlar). They took the drugs once a day for 8 weeks in addition to their existing drug regimen.

The researchers increased the doses on a weekly basis with a goal of reaching fasting plasma glucose (FPG) of 80-126 mg/dL. Daily doses of the investigational drug (nmol/kg) began at a mean 30 ± 11 and reached 114 ± 51 by the end of the study; daily mean doses of IGlar (U/kg) began at 0.11 ± 0.03 and ended at 0.33 ± 0.15.

Both medications boosted glycemic control at about the same level, the researchers report, based on levels of FPG, HbA1c, and fructosamine levels at 8 weeks.

Mean FPG levels (mg/dL), the primary endpoint, declined in investigational medication and IGlar from 175 ± 50 and 164 ± 31, respectively, at baseline to 129 ± 33 and 121 ± 17, respectively, at end of treatment. The treatment difference (investigational medication – IGlar) was 5.2 mg/dL [–8.8;19.1], 95% CI, P = .4567.

In a post hoc analysis, mean HbA1c levels declined from 8.1 ± 0.6% and 8.2 ± 0.8% at baseline in investigational medication and IGlar, respectively, to 7.3 ± 0.8% and 7.1 ± 0.6%, respectively. The treatment difference (investigational medication – IGlar) was 0.30% [–0.03;0.63], 95% CI, P = .0774.

In another post hoc analysis, mean fructosamine levels (micromol/L) dipped from 275 ± 44 and 273 ± 50 in investigational medication and IGlar, respectively, to 235 ± 45 and 223 ± 34, respectively. The treatment difference (investigational medication – IGlar)

was 9.6 micromol/L [–11.7;30.9], 95% CI, P = .3700. None of the patients reported severe hypoglycemia. In the investigational group, 6 subjects suffered 7 events of hypoglycemia that emerged or worsened during treatment; 11 events occurred in 6 subjects in the IGlar group. Researchers report similar levels of adverse events in both groups: 31 in 15 patients treated with the investigational drug and 37 in 17 patients treated with IGlar.

“After termination of treatment, plasma glucose rebounded to baseline levels within a couple of weeks,” Dr. Plum-Mörschel said.

Novo Nordisk funded the trial. Dr. Plum-Mörschel reports no disclosures.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: In 8-week trial, oral insulin tablets produce similar glucose control to injectable glargine (IGlar) in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM).

Major finding: Mean levels fasting plasma glucose (FPG, mg/dL) declined from 175 ± 50 to 129 ± 33 (investigational medication) and from 164 ± 31 to 121 ± 17 (IGlar). The treatment difference (investigational medication – IGlar) was 5.2 mg/dL [–8.8;19.1], 95% CI, P = .4567.

Data source: 50 insulin-naive patients with T2DM randomly assigned (1:1) to daily doses of investigational oral medication or IGlar for 8 weeks, titrated to reach target FPG of 80-126 mg/dL.

Disclosures: Novo Nordisk funded the trial. Dr. Plum-Mörschel reports no disclosures.

IDegLira equals basal-bolus insulin in HbA1c, lowers hypoglycemia risk

SAN DIEGO – When basal insulin alone does not achieve glucose targets in type 2 diabetes, a single fixed-dose injection of insulin degludec and liraglutide (IDegLira) is as effective as multiple insulin injections and has a significantly lower risk of hypoglycemia, according to a randomized, multicenter, open-label, industry-sponsored trial.

After 26 weeks of treatment, average hemoglobin A1c levels dropped similarly with once-daily IDegLira (1.48%) as with basal insulin glargine U100 plus mealtime injections of short-acting insulin aspart (1.46%; P less than .0001 for noninferiority), reported Liana K. Billings, MD, at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Patients also needed significantly less insulin and lost significantly more weight on IDegLira, compared with the basal-bolus regimen. “This is some of the most robust, most impressive data I’ve seen in years,” Julio Rosenstock, MD, director of the Dallas Diabetes and Endocrine Center in Texas, commented from the audience. Dr. Rosenstock was not involved in the trial and has studied other combination regimens for type 2 diabetes.

The advent of new insulins and adjunct therapies gives clinicians many potential algorithms for treating type 2 diabetes patients. The ADA recommends that health care professionals consider dual or triple therapy if patients do not meet glycemic targets with lifestyle changes and metformin alone. However, weight gain, hypoglycemia, and complex treatment regimens can make it difficult to intensify treatment in the real world, Dr. Billings said.

Insulin degludec is an ultra–long-acting basal insulin analogue, while liraglutide is a GLP-1 receptor agonist. The open-label, phase III DUAL VII study compared once-daily IDegLira injection (Xultophy, Novo Nordisk) with once-daily basal insulin glargine (Lantus, Sanofi) U100 plus bolus insulin aspart (NovoLog, Novo Nordisk) at mealtimes in 506 adults with type 2 diabetes. All patients were on metformin and glargine (typically 34 U) at baseline. Most were in their late 50s and obese, with an average 13-year duration of type 2 diabetes and HbA1c levels of 8.2% despite treatment. The IDegLira group started at 16 U and titrated by 2 U twice weekly to reach a fasting glucose target of 72-90 mg/dL. Basal-bolus patients maintained their baseline glargine dose and added 4 U mealtime bolus insulin aspart, titrating to target by 1 U twice weekly. The primary endpoint was change in HbA1c levels after 26 weeks. More than 98% of patients completed the trial. Approximately two-thirds of patients in both arms achieved an HbA1c level below 7%, but IDegLira recipients were significantly more likely to do so without gaining weight or experiencing hypoglycemia during the last 12 weeks of treatment (odds ratio, 10.39; 95% CI, 5.76-18.75). The IDegLira arm received significantly less daily insulin than the basal-bolus arm (40 U versus 84 U; P less than .0001), and IDegLira patients lost an average of 0.93 kg, while the comparison group gained 2.64 kg. Rates of serious adverse events were low and similar between arms. The cumulative rate of nausea was higher with IDegLira (11.1%) than with basal-bolus therapy (1.6%), Dr. Billings said. There were no deaths or unexpected adverse events.

Novo Nordisk makes Xultophy and funded the trial. Dr. Billings reported having served on advisory panels and speaker bureaus for Novo Nordisk.

SAN DIEGO – When basal insulin alone does not achieve glucose targets in type 2 diabetes, a single fixed-dose injection of insulin degludec and liraglutide (IDegLira) is as effective as multiple insulin injections and has a significantly lower risk of hypoglycemia, according to a randomized, multicenter, open-label, industry-sponsored trial.

After 26 weeks of treatment, average hemoglobin A1c levels dropped similarly with once-daily IDegLira (1.48%) as with basal insulin glargine U100 plus mealtime injections of short-acting insulin aspart (1.46%; P less than .0001 for noninferiority), reported Liana K. Billings, MD, at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Patients also needed significantly less insulin and lost significantly more weight on IDegLira, compared with the basal-bolus regimen. “This is some of the most robust, most impressive data I’ve seen in years,” Julio Rosenstock, MD, director of the Dallas Diabetes and Endocrine Center in Texas, commented from the audience. Dr. Rosenstock was not involved in the trial and has studied other combination regimens for type 2 diabetes.

The advent of new insulins and adjunct therapies gives clinicians many potential algorithms for treating type 2 diabetes patients. The ADA recommends that health care professionals consider dual or triple therapy if patients do not meet glycemic targets with lifestyle changes and metformin alone. However, weight gain, hypoglycemia, and complex treatment regimens can make it difficult to intensify treatment in the real world, Dr. Billings said.

Insulin degludec is an ultra–long-acting basal insulin analogue, while liraglutide is a GLP-1 receptor agonist. The open-label, phase III DUAL VII study compared once-daily IDegLira injection (Xultophy, Novo Nordisk) with once-daily basal insulin glargine (Lantus, Sanofi) U100 plus bolus insulin aspart (NovoLog, Novo Nordisk) at mealtimes in 506 adults with type 2 diabetes. All patients were on metformin and glargine (typically 34 U) at baseline. Most were in their late 50s and obese, with an average 13-year duration of type 2 diabetes and HbA1c levels of 8.2% despite treatment. The IDegLira group started at 16 U and titrated by 2 U twice weekly to reach a fasting glucose target of 72-90 mg/dL. Basal-bolus patients maintained their baseline glargine dose and added 4 U mealtime bolus insulin aspart, titrating to target by 1 U twice weekly. The primary endpoint was change in HbA1c levels after 26 weeks. More than 98% of patients completed the trial. Approximately two-thirds of patients in both arms achieved an HbA1c level below 7%, but IDegLira recipients were significantly more likely to do so without gaining weight or experiencing hypoglycemia during the last 12 weeks of treatment (odds ratio, 10.39; 95% CI, 5.76-18.75). The IDegLira arm received significantly less daily insulin than the basal-bolus arm (40 U versus 84 U; P less than .0001), and IDegLira patients lost an average of 0.93 kg, while the comparison group gained 2.64 kg. Rates of serious adverse events were low and similar between arms. The cumulative rate of nausea was higher with IDegLira (11.1%) than with basal-bolus therapy (1.6%), Dr. Billings said. There were no deaths or unexpected adverse events.

Novo Nordisk makes Xultophy and funded the trial. Dr. Billings reported having served on advisory panels and speaker bureaus for Novo Nordisk.

SAN DIEGO – When basal insulin alone does not achieve glucose targets in type 2 diabetes, a single fixed-dose injection of insulin degludec and liraglutide (IDegLira) is as effective as multiple insulin injections and has a significantly lower risk of hypoglycemia, according to a randomized, multicenter, open-label, industry-sponsored trial.

After 26 weeks of treatment, average hemoglobin A1c levels dropped similarly with once-daily IDegLira (1.48%) as with basal insulin glargine U100 plus mealtime injections of short-acting insulin aspart (1.46%; P less than .0001 for noninferiority), reported Liana K. Billings, MD, at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Patients also needed significantly less insulin and lost significantly more weight on IDegLira, compared with the basal-bolus regimen. “This is some of the most robust, most impressive data I’ve seen in years,” Julio Rosenstock, MD, director of the Dallas Diabetes and Endocrine Center in Texas, commented from the audience. Dr. Rosenstock was not involved in the trial and has studied other combination regimens for type 2 diabetes.

The advent of new insulins and adjunct therapies gives clinicians many potential algorithms for treating type 2 diabetes patients. The ADA recommends that health care professionals consider dual or triple therapy if patients do not meet glycemic targets with lifestyle changes and metformin alone. However, weight gain, hypoglycemia, and complex treatment regimens can make it difficult to intensify treatment in the real world, Dr. Billings said.

Insulin degludec is an ultra–long-acting basal insulin analogue, while liraglutide is a GLP-1 receptor agonist. The open-label, phase III DUAL VII study compared once-daily IDegLira injection (Xultophy, Novo Nordisk) with once-daily basal insulin glargine (Lantus, Sanofi) U100 plus bolus insulin aspart (NovoLog, Novo Nordisk) at mealtimes in 506 adults with type 2 diabetes. All patients were on metformin and glargine (typically 34 U) at baseline. Most were in their late 50s and obese, with an average 13-year duration of type 2 diabetes and HbA1c levels of 8.2% despite treatment. The IDegLira group started at 16 U and titrated by 2 U twice weekly to reach a fasting glucose target of 72-90 mg/dL. Basal-bolus patients maintained their baseline glargine dose and added 4 U mealtime bolus insulin aspart, titrating to target by 1 U twice weekly. The primary endpoint was change in HbA1c levels after 26 weeks. More than 98% of patients completed the trial. Approximately two-thirds of patients in both arms achieved an HbA1c level below 7%, but IDegLira recipients were significantly more likely to do so without gaining weight or experiencing hypoglycemia during the last 12 weeks of treatment (odds ratio, 10.39; 95% CI, 5.76-18.75). The IDegLira arm received significantly less daily insulin than the basal-bolus arm (40 U versus 84 U; P less than .0001), and IDegLira patients lost an average of 0.93 kg, while the comparison group gained 2.64 kg. Rates of serious adverse events were low and similar between arms. The cumulative rate of nausea was higher with IDegLira (11.1%) than with basal-bolus therapy (1.6%), Dr. Billings said. There were no deaths or unexpected adverse events.

Novo Nordisk makes Xultophy and funded the trial. Dr. Billings reported having served on advisory panels and speaker bureaus for Novo Nordisk.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: A single daily injection of fixed-dose insulin degludec and liraglutide (IDegLira) improved hemoglobin A1c levels as much as basal-bolus insulin therapy while producing significantly less hypoglycemia.

Major finding: HbA1c levels dropped similarly with IDegLira (1.48%) or basal insulin glargine U100 plus mealtime injections of short-acting insulin aspart (1.46%; P less than .0001 for noninferiority).

Data source: DUAL VII, a multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase III trial of 506 adults with type 2 diabetes who did not reach glucose targets on basal insulin glargine and metformin.

Disclosures: Novo Nordisk makes Xultophy and funded the trial. Dr. Billings reported having served on advisory panels and speaker bureaus for Novo Nordisk.

Consistent weight benefits seen in empagliflozin use

SAN DIEGO – In a follow-up to the blockbuster trial results linking the type 2 diabetes drug empagliflozin (Jardiance) to a dramatically lower risk of cardiac death, researchers report that the drug improved weight-related measures in multiple groups.

Two daily doses of empagliflozin, 10 mg and 25 mg, “had consistent and robust effects on lowering weight, waist circumference, and other markers of body fat across most patients regardless of their age, sex, or degree of abdominal obesity,” study lead author Ian J. Neeland, MD, of the department of medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, said in an interview. “Our next step is to determine if these effects may contribute to the improvement in cardiovascular risk seen with the drug.”

“In the EMPA-REG OUTCOME study, empagliflozin treatment significantly reduced the risk of cardiovascular death by 38%,” Dr. Neeland said. “We also observed that patients treated with empagliflozin had improvements in markers of body fatness such as weight, waist circumference, and estimated total body fat. Since we know that obesity is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, we were interested in finding out if the improvements in weight and other markers of body fatness may have contributed to the observed cardiovascular benefits of empagliflozin in the study. One part of this was to examine whether the drug had consistent effects on body fat according to other important cardiovascular risk factors.”

The researchers analyzed changes in body weight, waist circumference, index of central obesity, and estimated total body fat from baseline to week 164 in a study that randomly assigned participants with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease to placebo or 10 mg or 25 mg of empagliflozin. The number of patients in the groups were 2,333, 2,345 and 2,342, respectively, and their mean baseline weight was around 86.0 kg.

In general, researchers found that across groups, weight measures improved more in drug-treated patients than those treated with placebo. The higher dose (25 mg) often had a greater effect; the two available doses of the drug are 10 mg and 20 mg.

For example, the placebo-adjusted mean reduction in weight was –1.70 kg in men (95% confidence interval, –2.14 to –1.27) in the 10-mg group and 2.18 kg (95% CI, –2.61 to –1.75) in the 25-mg group. For women, the reduction was –1.32 kg (95% CI, –2.02 to –0.62) in the 10-mg group and –1.44 kg (95% CI, –2.15 to –0.73) in the 25-mg group.

“Patients lost on average 1.5-2 kg of weight – about 4 pounds – with empagliflozin, compared with placebo,” Dr. Neeland said. “Although quality of life and other metrics of better health were not systematically collected, we do know that people who lose weight and waist circumference tend to feel better, have fewer health problems, and live longer, compared with people who remain obese.”

Dr. Neeland said researchers still need to understand whether the improvements in obesity markers contribute to the drug’s positive cardiac effects.

Study funding was not reported. The original EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly. Dr. Neeland disclosed consultant/speakers bureau support from Boehringer Ingelheim. He is a scientific advisory board member for Advanced MR Analytics AB.

SAN DIEGO – In a follow-up to the blockbuster trial results linking the type 2 diabetes drug empagliflozin (Jardiance) to a dramatically lower risk of cardiac death, researchers report that the drug improved weight-related measures in multiple groups.

Two daily doses of empagliflozin, 10 mg and 25 mg, “had consistent and robust effects on lowering weight, waist circumference, and other markers of body fat across most patients regardless of their age, sex, or degree of abdominal obesity,” study lead author Ian J. Neeland, MD, of the department of medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, said in an interview. “Our next step is to determine if these effects may contribute to the improvement in cardiovascular risk seen with the drug.”

“In the EMPA-REG OUTCOME study, empagliflozin treatment significantly reduced the risk of cardiovascular death by 38%,” Dr. Neeland said. “We also observed that patients treated with empagliflozin had improvements in markers of body fatness such as weight, waist circumference, and estimated total body fat. Since we know that obesity is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, we were interested in finding out if the improvements in weight and other markers of body fatness may have contributed to the observed cardiovascular benefits of empagliflozin in the study. One part of this was to examine whether the drug had consistent effects on body fat according to other important cardiovascular risk factors.”

The researchers analyzed changes in body weight, waist circumference, index of central obesity, and estimated total body fat from baseline to week 164 in a study that randomly assigned participants with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease to placebo or 10 mg or 25 mg of empagliflozin. The number of patients in the groups were 2,333, 2,345 and 2,342, respectively, and their mean baseline weight was around 86.0 kg.

In general, researchers found that across groups, weight measures improved more in drug-treated patients than those treated with placebo. The higher dose (25 mg) often had a greater effect; the two available doses of the drug are 10 mg and 20 mg.

For example, the placebo-adjusted mean reduction in weight was –1.70 kg in men (95% confidence interval, –2.14 to –1.27) in the 10-mg group and 2.18 kg (95% CI, –2.61 to –1.75) in the 25-mg group. For women, the reduction was –1.32 kg (95% CI, –2.02 to –0.62) in the 10-mg group and –1.44 kg (95% CI, –2.15 to –0.73) in the 25-mg group.

“Patients lost on average 1.5-2 kg of weight – about 4 pounds – with empagliflozin, compared with placebo,” Dr. Neeland said. “Although quality of life and other metrics of better health were not systematically collected, we do know that people who lose weight and waist circumference tend to feel better, have fewer health problems, and live longer, compared with people who remain obese.”

Dr. Neeland said researchers still need to understand whether the improvements in obesity markers contribute to the drug’s positive cardiac effects.

Study funding was not reported. The original EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly. Dr. Neeland disclosed consultant/speakers bureau support from Boehringer Ingelheim. He is a scientific advisory board member for Advanced MR Analytics AB.

SAN DIEGO – In a follow-up to the blockbuster trial results linking the type 2 diabetes drug empagliflozin (Jardiance) to a dramatically lower risk of cardiac death, researchers report that the drug improved weight-related measures in multiple groups.

Two daily doses of empagliflozin, 10 mg and 25 mg, “had consistent and robust effects on lowering weight, waist circumference, and other markers of body fat across most patients regardless of their age, sex, or degree of abdominal obesity,” study lead author Ian J. Neeland, MD, of the department of medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, said in an interview. “Our next step is to determine if these effects may contribute to the improvement in cardiovascular risk seen with the drug.”

“In the EMPA-REG OUTCOME study, empagliflozin treatment significantly reduced the risk of cardiovascular death by 38%,” Dr. Neeland said. “We also observed that patients treated with empagliflozin had improvements in markers of body fatness such as weight, waist circumference, and estimated total body fat. Since we know that obesity is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, we were interested in finding out if the improvements in weight and other markers of body fatness may have contributed to the observed cardiovascular benefits of empagliflozin in the study. One part of this was to examine whether the drug had consistent effects on body fat according to other important cardiovascular risk factors.”