User login

Diabetes Hub contains news and clinical review articles for physicians seeking the most up-to-date information on the rapidly evolving options for treating and preventing Type 2 Diabetes in at-risk patients. The Diabetes Hub is powered by Frontline Medical Communications.

Adolescent lap band removal rate swells by 5 years

LOS ANGELES – An increasing number of adolescents are undergoing gastric band removal after 2 years post operation, a prospective, longitudinal study shows.

“At 2 years most bands are still in place, with 96% of patients having them. After this point, however, multiple bands are removed each year, demonstrating that 2 years perhaps is only the tip of the iceberg,” Dr. Christine Schad said at Obesity Week.

Indeed, the number of adolescents with bands in place reduced to 87%, 76%, and 53% at years 3, 4, and 5 of follow-up. After 5 years, patients continued to undergo band removal.

Like their adult counterparts, adolescents underwent band removal secondary to weight loss failure, reflux esophagitis, and refractory gastric prolapse, Dr. Schad of Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital, New York-Presbyterian Columbia University Medical Center, New York, said.

Weight loss seemed to plateau over time among the 79 evaluable adolescents, with less than 39% of patients able to lose more than 50% of their excess body weight over the 5-year study.

“Although gastric banding can be performed safely, 2 years seems inadequate to evaluate efficacy,” she said.

The use of adjustable gastric banding rose rapidly after Food and Drug Administration approval in 2001, thanks to low perioperative morbidity, reversibility, and good early results.

Gastric banding has fallen sharply, however, with recent adult studies showing a high incidence of weight loss failure, weight regain, and device-related complications.

Previous studies have reported on the safety of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in adolescents; however, these studies are limited to 3-year follow-up at most, Dr. Schad said at the meeting presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

The investigators enrolled 137 morbidly obese adolescents, aged 14-18 years, who underwent laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding from 2006 to 2011. The current analysis included patients with at least 5 years follow-up and patients who had band removal at any point or who did not survive to study end. There were two deaths. The remaining patients had not reached the 5-year follow-up mark or still had their bands in place.

The 79 evaluable patients had a preoperative weight of 138 kg, body mass index of 49.3 kg/m2, and excess body weight of 47.2%. At the time of surgery, their average age was 16.9 years, 71% were female, 43% Hispanic, 36.7% white, and 16.5% black.

Even though gastric banding is declining, the results are important because there has been little information about adolescents, and in some parts of the country, gastric banding may be the only available option, session comoderator Dr. Robert Carpenter of Scott & White Healthcare in Temple, Tex., said in an interview.

“The other issue is that there are a lot of pediatricians that only want their patients to have nonstapled, nondivided operations,” he said. “If that’s the case, and we now know that perhaps for adolescents there is a 30%, 40%, 50% conversion and/or failure rate, then we are putting these kids at an extreme risk.”

Oftentimes, these adolescents also won’t have an opportunity for another operation.

“Many insurance companies that they’ll transition to away from their parents will actually have a complete exclusion for bariatric surgery or they have a onetime, lifetime operative opportunity,” Dr. Carpenter said. “So, if that’s been burned, it’s burned.”

LOS ANGELES – An increasing number of adolescents are undergoing gastric band removal after 2 years post operation, a prospective, longitudinal study shows.

“At 2 years most bands are still in place, with 96% of patients having them. After this point, however, multiple bands are removed each year, demonstrating that 2 years perhaps is only the tip of the iceberg,” Dr. Christine Schad said at Obesity Week.

Indeed, the number of adolescents with bands in place reduced to 87%, 76%, and 53% at years 3, 4, and 5 of follow-up. After 5 years, patients continued to undergo band removal.

Like their adult counterparts, adolescents underwent band removal secondary to weight loss failure, reflux esophagitis, and refractory gastric prolapse, Dr. Schad of Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital, New York-Presbyterian Columbia University Medical Center, New York, said.

Weight loss seemed to plateau over time among the 79 evaluable adolescents, with less than 39% of patients able to lose more than 50% of their excess body weight over the 5-year study.

“Although gastric banding can be performed safely, 2 years seems inadequate to evaluate efficacy,” she said.

The use of adjustable gastric banding rose rapidly after Food and Drug Administration approval in 2001, thanks to low perioperative morbidity, reversibility, and good early results.

Gastric banding has fallen sharply, however, with recent adult studies showing a high incidence of weight loss failure, weight regain, and device-related complications.

Previous studies have reported on the safety of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in adolescents; however, these studies are limited to 3-year follow-up at most, Dr. Schad said at the meeting presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

The investigators enrolled 137 morbidly obese adolescents, aged 14-18 years, who underwent laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding from 2006 to 2011. The current analysis included patients with at least 5 years follow-up and patients who had band removal at any point or who did not survive to study end. There were two deaths. The remaining patients had not reached the 5-year follow-up mark or still had their bands in place.

The 79 evaluable patients had a preoperative weight of 138 kg, body mass index of 49.3 kg/m2, and excess body weight of 47.2%. At the time of surgery, their average age was 16.9 years, 71% were female, 43% Hispanic, 36.7% white, and 16.5% black.

Even though gastric banding is declining, the results are important because there has been little information about adolescents, and in some parts of the country, gastric banding may be the only available option, session comoderator Dr. Robert Carpenter of Scott & White Healthcare in Temple, Tex., said in an interview.

“The other issue is that there are a lot of pediatricians that only want their patients to have nonstapled, nondivided operations,” he said. “If that’s the case, and we now know that perhaps for adolescents there is a 30%, 40%, 50% conversion and/or failure rate, then we are putting these kids at an extreme risk.”

Oftentimes, these adolescents also won’t have an opportunity for another operation.

“Many insurance companies that they’ll transition to away from their parents will actually have a complete exclusion for bariatric surgery or they have a onetime, lifetime operative opportunity,” Dr. Carpenter said. “So, if that’s been burned, it’s burned.”

LOS ANGELES – An increasing number of adolescents are undergoing gastric band removal after 2 years post operation, a prospective, longitudinal study shows.

“At 2 years most bands are still in place, with 96% of patients having them. After this point, however, multiple bands are removed each year, demonstrating that 2 years perhaps is only the tip of the iceberg,” Dr. Christine Schad said at Obesity Week.

Indeed, the number of adolescents with bands in place reduced to 87%, 76%, and 53% at years 3, 4, and 5 of follow-up. After 5 years, patients continued to undergo band removal.

Like their adult counterparts, adolescents underwent band removal secondary to weight loss failure, reflux esophagitis, and refractory gastric prolapse, Dr. Schad of Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital, New York-Presbyterian Columbia University Medical Center, New York, said.

Weight loss seemed to plateau over time among the 79 evaluable adolescents, with less than 39% of patients able to lose more than 50% of their excess body weight over the 5-year study.

“Although gastric banding can be performed safely, 2 years seems inadequate to evaluate efficacy,” she said.

The use of adjustable gastric banding rose rapidly after Food and Drug Administration approval in 2001, thanks to low perioperative morbidity, reversibility, and good early results.

Gastric banding has fallen sharply, however, with recent adult studies showing a high incidence of weight loss failure, weight regain, and device-related complications.

Previous studies have reported on the safety of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in adolescents; however, these studies are limited to 3-year follow-up at most, Dr. Schad said at the meeting presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

The investigators enrolled 137 morbidly obese adolescents, aged 14-18 years, who underwent laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding from 2006 to 2011. The current analysis included patients with at least 5 years follow-up and patients who had band removal at any point or who did not survive to study end. There were two deaths. The remaining patients had not reached the 5-year follow-up mark or still had their bands in place.

The 79 evaluable patients had a preoperative weight of 138 kg, body mass index of 49.3 kg/m2, and excess body weight of 47.2%. At the time of surgery, their average age was 16.9 years, 71% were female, 43% Hispanic, 36.7% white, and 16.5% black.

Even though gastric banding is declining, the results are important because there has been little information about adolescents, and in some parts of the country, gastric banding may be the only available option, session comoderator Dr. Robert Carpenter of Scott & White Healthcare in Temple, Tex., said in an interview.

“The other issue is that there are a lot of pediatricians that only want their patients to have nonstapled, nondivided operations,” he said. “If that’s the case, and we now know that perhaps for adolescents there is a 30%, 40%, 50% conversion and/or failure rate, then we are putting these kids at an extreme risk.”

Oftentimes, these adolescents also won’t have an opportunity for another operation.

“Many insurance companies that they’ll transition to away from their parents will actually have a complete exclusion for bariatric surgery or they have a onetime, lifetime operative opportunity,” Dr. Carpenter said. “So, if that’s been burned, it’s burned.”

AT OBESITY WEEK 2015

Key clinical point: Adolescents undergo laparoscopic adjustable gastric band removal at increasing numbers after 2 years post operation.

Major finding: The percentage of bands in place was 96% at 2 years, declining to 87%, 76%, and 53% at years 3, 4, and 5.

Data source: Prospective, longitudinal study in 79 adolescents.

Disclosures: Dr. Schad reported having no disclosures.

Old-school paper handouts on par with weight loss phone app

LOS ANGELES – Use of a mobile phone app alone or personal coaching with smartphone self-monitoring was no better than were simple paper handouts for reducing weight after 24 months in obese or overweight young adults, the prospective CITY trial shows.

Patients given the free Android app lost the least amount of weight, averaging –0.87 kg, –1.48 kg, and –0.99 kg at months 6, 12, and 24.

This was similar to mean losses of –1.14 kg, –2.25 kg, and –1.44 kg among controls, who received three handouts on healthy eating and physical activity from the Eat Smart, Move More North Carolina program and were not asked to self-monitor.

Patients randomly assigned to personal coaching plus smartphone self-monitoring lost the most weight at months 6, 12, and 24 (mean –3.07 kg, –3.58 kg, –2.45 kg).

This was significantly more than controls at 6 months (net effect –1.92 kg; P = .003), but not at 12 months or 24 months, according to results to be presented formally at Obesity Week 2015 and simultaneously published online (Obesity. 2015 Nov. doi:10.1002/oby.21226).

“Although conclusions can only be drawn about the specific app tested, the CITY trial sounds a cautionary note concerning intervention delivery by mobile applications alone,” principal investigator Laura Svetkey of Duke University, Durham, N.C., advised.

CITY (Cell Phone Intervention for Young Adults) involved 365 individuals aged 18-35 years with a body mass index of at least 25 kg/m2, and was described as the largest and longest comparative-effectiveness trial to examine theory-based behavioral weight loss interventions that may be suitable for widespread use. At entry, the average age was 29.4 years, 69.6% were women, and average BMI was 35 kg/m2.

The results are surprising because both active interventions included behavior principles and tools, and intervention engagement and study retention remained high, according to the researchers.

Participants continued to use the investigator-designed phone app an average of twice weekly for 2 years, and final weight measurements at 2 years were available in 86% of patients: 104 patients randomized to the cell phone (CP) app, 104 to personal coaching (PC), and 105 controls.

The lack of efficacy of the CP and PC interventions at 2 years may be in part related to the behavior of the control group, which had better-than-expected outcomes, Dr. Svetkey suggested. Based on observational data, the control group was expected to gain 1.5 kg per year, but instead, 22% had a clinically meaningful weight loss of at least 5%, which did not differ significantly from the CP and PC groups at 25.5% and 27.5%.

Notably, 54% of controls also reported using at least one commercial weight loss app during the trial. Mean weight change at 24 months, however, was similar in the control group among commercial app users and nonusers (–1.2 kg vs. –1.8 kg), she reported at the meeting, which was presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

It’s also possible the CP app was ineffective because its design wasn’t sufficiently compelling and couldn’t be individually tailored to adapt to participants’ behavior and needs, the authors noted.

The CP intervention was delivered solely through the Android app, which included goal setting, challenge games, and social support via a “buddy system” that allowed predetermined messages to be sent to a randomly assigned buddy participant. A free Bluetooth-enabled scale was used to automatically transmit weight through the smartphone to the study database. Self-management behaviors were prompted by the app based on a protocol-driven schedule.

“Indeed, future trials may need to consider rapid, responsive, relevant (R3) design in which rapid assessment of usage and outcomes allows for response design changes that keep the app relevant to users,” Dr. Svetkey and colleagues wrote.

CP also may have been ineffective because it lacked human contact, while the PC intervention included six weekly face-to-face sessions, followed by monthly telephone calls.

Although PC led to significantly greater weight loss than did the phone app at 6 months (net effect –2.19 kg; P less than .001) and 12 months (net effect –2.10 kg; P = .025), the effect size was smaller than in studies in older adults with more in-person sessions, suggesting that the dose or intensity may have been insufficient for a sustained effect or that this approach is less effective in younger than older adults.

“Effective weight loss intervention for young adults that can be implemented efficiently and broadly may require the scalability of mobile technology, the social support and human interaction of personal coaching, an adaptive approach to intervention design, and more personally tailored approaches,” Dr. Svetkey and colleagues concluded.

The study was sponsored by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Svetkey reported consulting for the Oregon Center for Applied Science. One coauthor disclosed serving as a consultant for Gilead Sciences and another is a scientific advisory board member for Nutrisystem and owns shares in Scale Down, a digital weight loss vendor.

LOS ANGELES – Use of a mobile phone app alone or personal coaching with smartphone self-monitoring was no better than were simple paper handouts for reducing weight after 24 months in obese or overweight young adults, the prospective CITY trial shows.

Patients given the free Android app lost the least amount of weight, averaging –0.87 kg, –1.48 kg, and –0.99 kg at months 6, 12, and 24.

This was similar to mean losses of –1.14 kg, –2.25 kg, and –1.44 kg among controls, who received three handouts on healthy eating and physical activity from the Eat Smart, Move More North Carolina program and were not asked to self-monitor.

Patients randomly assigned to personal coaching plus smartphone self-monitoring lost the most weight at months 6, 12, and 24 (mean –3.07 kg, –3.58 kg, –2.45 kg).

This was significantly more than controls at 6 months (net effect –1.92 kg; P = .003), but not at 12 months or 24 months, according to results to be presented formally at Obesity Week 2015 and simultaneously published online (Obesity. 2015 Nov. doi:10.1002/oby.21226).

“Although conclusions can only be drawn about the specific app tested, the CITY trial sounds a cautionary note concerning intervention delivery by mobile applications alone,” principal investigator Laura Svetkey of Duke University, Durham, N.C., advised.

CITY (Cell Phone Intervention for Young Adults) involved 365 individuals aged 18-35 years with a body mass index of at least 25 kg/m2, and was described as the largest and longest comparative-effectiveness trial to examine theory-based behavioral weight loss interventions that may be suitable for widespread use. At entry, the average age was 29.4 years, 69.6% were women, and average BMI was 35 kg/m2.

The results are surprising because both active interventions included behavior principles and tools, and intervention engagement and study retention remained high, according to the researchers.

Participants continued to use the investigator-designed phone app an average of twice weekly for 2 years, and final weight measurements at 2 years were available in 86% of patients: 104 patients randomized to the cell phone (CP) app, 104 to personal coaching (PC), and 105 controls.

The lack of efficacy of the CP and PC interventions at 2 years may be in part related to the behavior of the control group, which had better-than-expected outcomes, Dr. Svetkey suggested. Based on observational data, the control group was expected to gain 1.5 kg per year, but instead, 22% had a clinically meaningful weight loss of at least 5%, which did not differ significantly from the CP and PC groups at 25.5% and 27.5%.

Notably, 54% of controls also reported using at least one commercial weight loss app during the trial. Mean weight change at 24 months, however, was similar in the control group among commercial app users and nonusers (–1.2 kg vs. –1.8 kg), she reported at the meeting, which was presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

It’s also possible the CP app was ineffective because its design wasn’t sufficiently compelling and couldn’t be individually tailored to adapt to participants’ behavior and needs, the authors noted.

The CP intervention was delivered solely through the Android app, which included goal setting, challenge games, and social support via a “buddy system” that allowed predetermined messages to be sent to a randomly assigned buddy participant. A free Bluetooth-enabled scale was used to automatically transmit weight through the smartphone to the study database. Self-management behaviors were prompted by the app based on a protocol-driven schedule.

“Indeed, future trials may need to consider rapid, responsive, relevant (R3) design in which rapid assessment of usage and outcomes allows for response design changes that keep the app relevant to users,” Dr. Svetkey and colleagues wrote.

CP also may have been ineffective because it lacked human contact, while the PC intervention included six weekly face-to-face sessions, followed by monthly telephone calls.

Although PC led to significantly greater weight loss than did the phone app at 6 months (net effect –2.19 kg; P less than .001) and 12 months (net effect –2.10 kg; P = .025), the effect size was smaller than in studies in older adults with more in-person sessions, suggesting that the dose or intensity may have been insufficient for a sustained effect or that this approach is less effective in younger than older adults.

“Effective weight loss intervention for young adults that can be implemented efficiently and broadly may require the scalability of mobile technology, the social support and human interaction of personal coaching, an adaptive approach to intervention design, and more personally tailored approaches,” Dr. Svetkey and colleagues concluded.

The study was sponsored by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Svetkey reported consulting for the Oregon Center for Applied Science. One coauthor disclosed serving as a consultant for Gilead Sciences and another is a scientific advisory board member for Nutrisystem and owns shares in Scale Down, a digital weight loss vendor.

LOS ANGELES – Use of a mobile phone app alone or personal coaching with smartphone self-monitoring was no better than were simple paper handouts for reducing weight after 24 months in obese or overweight young adults, the prospective CITY trial shows.

Patients given the free Android app lost the least amount of weight, averaging –0.87 kg, –1.48 kg, and –0.99 kg at months 6, 12, and 24.

This was similar to mean losses of –1.14 kg, –2.25 kg, and –1.44 kg among controls, who received three handouts on healthy eating and physical activity from the Eat Smart, Move More North Carolina program and were not asked to self-monitor.

Patients randomly assigned to personal coaching plus smartphone self-monitoring lost the most weight at months 6, 12, and 24 (mean –3.07 kg, –3.58 kg, –2.45 kg).

This was significantly more than controls at 6 months (net effect –1.92 kg; P = .003), but not at 12 months or 24 months, according to results to be presented formally at Obesity Week 2015 and simultaneously published online (Obesity. 2015 Nov. doi:10.1002/oby.21226).

“Although conclusions can only be drawn about the specific app tested, the CITY trial sounds a cautionary note concerning intervention delivery by mobile applications alone,” principal investigator Laura Svetkey of Duke University, Durham, N.C., advised.

CITY (Cell Phone Intervention for Young Adults) involved 365 individuals aged 18-35 years with a body mass index of at least 25 kg/m2, and was described as the largest and longest comparative-effectiveness trial to examine theory-based behavioral weight loss interventions that may be suitable for widespread use. At entry, the average age was 29.4 years, 69.6% were women, and average BMI was 35 kg/m2.

The results are surprising because both active interventions included behavior principles and tools, and intervention engagement and study retention remained high, according to the researchers.

Participants continued to use the investigator-designed phone app an average of twice weekly for 2 years, and final weight measurements at 2 years were available in 86% of patients: 104 patients randomized to the cell phone (CP) app, 104 to personal coaching (PC), and 105 controls.

The lack of efficacy of the CP and PC interventions at 2 years may be in part related to the behavior of the control group, which had better-than-expected outcomes, Dr. Svetkey suggested. Based on observational data, the control group was expected to gain 1.5 kg per year, but instead, 22% had a clinically meaningful weight loss of at least 5%, which did not differ significantly from the CP and PC groups at 25.5% and 27.5%.

Notably, 54% of controls also reported using at least one commercial weight loss app during the trial. Mean weight change at 24 months, however, was similar in the control group among commercial app users and nonusers (–1.2 kg vs. –1.8 kg), she reported at the meeting, which was presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

It’s also possible the CP app was ineffective because its design wasn’t sufficiently compelling and couldn’t be individually tailored to adapt to participants’ behavior and needs, the authors noted.

The CP intervention was delivered solely through the Android app, which included goal setting, challenge games, and social support via a “buddy system” that allowed predetermined messages to be sent to a randomly assigned buddy participant. A free Bluetooth-enabled scale was used to automatically transmit weight through the smartphone to the study database. Self-management behaviors were prompted by the app based on a protocol-driven schedule.

“Indeed, future trials may need to consider rapid, responsive, relevant (R3) design in which rapid assessment of usage and outcomes allows for response design changes that keep the app relevant to users,” Dr. Svetkey and colleagues wrote.

CP also may have been ineffective because it lacked human contact, while the PC intervention included six weekly face-to-face sessions, followed by monthly telephone calls.

Although PC led to significantly greater weight loss than did the phone app at 6 months (net effect –2.19 kg; P less than .001) and 12 months (net effect –2.10 kg; P = .025), the effect size was smaller than in studies in older adults with more in-person sessions, suggesting that the dose or intensity may have been insufficient for a sustained effect or that this approach is less effective in younger than older adults.

“Effective weight loss intervention for young adults that can be implemented efficiently and broadly may require the scalability of mobile technology, the social support and human interaction of personal coaching, an adaptive approach to intervention design, and more personally tailored approaches,” Dr. Svetkey and colleagues concluded.

The study was sponsored by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Svetkey reported consulting for the Oregon Center for Applied Science. One coauthor disclosed serving as a consultant for Gilead Sciences and another is a scientific advisory board member for Nutrisystem and owns shares in Scale Down, a digital weight loss vendor.

AT OBESITY WEEK 2015

Key clinical point: A mobile phone app alone may not be enough to prompt weight loss in obese or overweight young adults.

Major finding: Weight loss with a smartphone app alone was not superior to control at any time point.

Data source: Randomized trial of 365 obese or overweight young adults.

Disclosures: The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute sponsored the study. Dr. Svetkey reported consulting for the Oregon Center for Applied Science. One coauthor disclosed serving as a consultant for Gilead Sciences and another is a scientific advisory board member for Nutrisystem and owns shares in Scale Down, a digital weight loss vendor.

Even subclinical hypothyroidism ups risk for metabolic syndrome

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – Patients with low thyroid function may experience a “double whammy” of hypothyroidism and metabolic syndrome.

Even subclinical hypothyroidism affects many metabolic pathways that can contribute to deranged glucose and lipid metabolism, raising the risk of metabolic syndrome, according to Dr. Gabriela Brenta of the department of endocrinology at the Dr. Cesar Milstein Hospital in Buenos Aires. Though some mechanisms are incompletely understood, the association is clear enough to warrant screening all metabolic syndrome patients for hypothyroidism, she said.

Dr. Brenta described the recent work she and others have completed in the field. Basic science work revealed some early clues. For example, those who studied the effects of acute thyroid hormone withdrawal on patients with no thyroid gland found that these patients saw a rapid rise in insulin resistance. It’s known that even subclinical insulin resistance can lead to impaired glucose metabolism, making it logical to follow both normal and deranged metabolic pathways to help sort out the relationship between thyroid dysfunction and impaired glucose metabolism, she reported at the International Thyroid Congress.

Hypothyroidism can affect glucose homeostasis through multiple mechanisms, said Dr. Brenta. Firstly, hypothyroidism can lead to decreased hepatic gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis. Hypothyroidism also can lead to reduced baseline plasma insulin levels and increased postglucose insulin secretion. In the peripheral tissues, hypothyroidism can interfere with glucose metabolism and disposal. All of these mechanisms can decrease hepatic glucose metabolism and lead to a postabsorptive hyperglycemia state, said Dr. Brenta, noting: “Insulin resistance is in some way the backbone of metabolic syndrome.”

Lipid metabolism is also affected by subclinical hypothyroidism, which can decrease expression of mRNA for LDL-C receptors, leading to LDL-C receptor down-regulation. With fewer receptors available, serum levels of LDL-C increase, with resultant increased susceptibility to oxidative effects and increased foam cell generation.

Dr. Brenta cited her earlier work showing that “triglyceride enrichment of LDL particles correlates with lower hepatic lipase activity” for individuals with subclinical hypothyroidism, with significantly lower hepatic lipase activity and a higher LDL-C to triglyceride ratio for those patients than for controls (Thyroid. 2007 May;17[5]:453-60). Overall, in hypothyroidism, “LDL particles are exposed to more substances that make them more atherogenic with decreased degradation and increased half-life,” said Dr. Brenta.

The increased risk for hypertension in both subclinical and overt hypothyroidism may be related, in part, to the fact that triiodothyronine deficiency can contribute to endothelial dysfunction. The relationship between subclinical hypothyroidism and hypertension was confirmed in a 2011 meta-analysis, said Dr. Brenta (Hypertens Res. 2011 Oct;34[10]:1098-105).

Though many factors contribute to obesity and thyroid function alone does not regulate body weight, a large population-based Danish study found that “even mild elevations of TSH are important for body weight,” said Dr. Brenta. The relationship is complex and bidirectional – a classic “chicken and egg” story – since obesity also may modulate TSH, she said; “however, we must not forget the ample literature on low levels of thyroid hormones reducing resting energy expenditure” (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005 Jul;90[7]:4019-24).

Even though TSH tends to rise naturally through the lifespan, the association between elevated TSH and increased risk of metabolic syndrome held true even for older patients in one study, with “each one unit increase in TSH predicting a 3% increase in the odds of metabolic syndrome,” even after adjustment for age, BMI, and HOMA-IR status, among other variables, said Dr. Brenta (Clin Endocrinol [Oxf]. 2012 Jun;76[6]:911-8).

Advocating for universal screening for hypothyroidism among patients with metabolic syndrome, Dr. Brenta said that “hypothyroid disturbances are associated with an adverse metabolic profile, and even low normal TSH levels are associated with the metabolic traits of metabolic syndrome.”

The meeting was held by the American Thyroid Association, Asia-Oceania Thyroid Association, European Thyroid Association, and Latin American Thyroid Society. Dr. Brenta did not identify any conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @karioakes

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – Patients with low thyroid function may experience a “double whammy” of hypothyroidism and metabolic syndrome.

Even subclinical hypothyroidism affects many metabolic pathways that can contribute to deranged glucose and lipid metabolism, raising the risk of metabolic syndrome, according to Dr. Gabriela Brenta of the department of endocrinology at the Dr. Cesar Milstein Hospital in Buenos Aires. Though some mechanisms are incompletely understood, the association is clear enough to warrant screening all metabolic syndrome patients for hypothyroidism, she said.

Dr. Brenta described the recent work she and others have completed in the field. Basic science work revealed some early clues. For example, those who studied the effects of acute thyroid hormone withdrawal on patients with no thyroid gland found that these patients saw a rapid rise in insulin resistance. It’s known that even subclinical insulin resistance can lead to impaired glucose metabolism, making it logical to follow both normal and deranged metabolic pathways to help sort out the relationship between thyroid dysfunction and impaired glucose metabolism, she reported at the International Thyroid Congress.

Hypothyroidism can affect glucose homeostasis through multiple mechanisms, said Dr. Brenta. Firstly, hypothyroidism can lead to decreased hepatic gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis. Hypothyroidism also can lead to reduced baseline plasma insulin levels and increased postglucose insulin secretion. In the peripheral tissues, hypothyroidism can interfere with glucose metabolism and disposal. All of these mechanisms can decrease hepatic glucose metabolism and lead to a postabsorptive hyperglycemia state, said Dr. Brenta, noting: “Insulin resistance is in some way the backbone of metabolic syndrome.”

Lipid metabolism is also affected by subclinical hypothyroidism, which can decrease expression of mRNA for LDL-C receptors, leading to LDL-C receptor down-regulation. With fewer receptors available, serum levels of LDL-C increase, with resultant increased susceptibility to oxidative effects and increased foam cell generation.

Dr. Brenta cited her earlier work showing that “triglyceride enrichment of LDL particles correlates with lower hepatic lipase activity” for individuals with subclinical hypothyroidism, with significantly lower hepatic lipase activity and a higher LDL-C to triglyceride ratio for those patients than for controls (Thyroid. 2007 May;17[5]:453-60). Overall, in hypothyroidism, “LDL particles are exposed to more substances that make them more atherogenic with decreased degradation and increased half-life,” said Dr. Brenta.

The increased risk for hypertension in both subclinical and overt hypothyroidism may be related, in part, to the fact that triiodothyronine deficiency can contribute to endothelial dysfunction. The relationship between subclinical hypothyroidism and hypertension was confirmed in a 2011 meta-analysis, said Dr. Brenta (Hypertens Res. 2011 Oct;34[10]:1098-105).

Though many factors contribute to obesity and thyroid function alone does not regulate body weight, a large population-based Danish study found that “even mild elevations of TSH are important for body weight,” said Dr. Brenta. The relationship is complex and bidirectional – a classic “chicken and egg” story – since obesity also may modulate TSH, she said; “however, we must not forget the ample literature on low levels of thyroid hormones reducing resting energy expenditure” (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005 Jul;90[7]:4019-24).

Even though TSH tends to rise naturally through the lifespan, the association between elevated TSH and increased risk of metabolic syndrome held true even for older patients in one study, with “each one unit increase in TSH predicting a 3% increase in the odds of metabolic syndrome,” even after adjustment for age, BMI, and HOMA-IR status, among other variables, said Dr. Brenta (Clin Endocrinol [Oxf]. 2012 Jun;76[6]:911-8).

Advocating for universal screening for hypothyroidism among patients with metabolic syndrome, Dr. Brenta said that “hypothyroid disturbances are associated with an adverse metabolic profile, and even low normal TSH levels are associated with the metabolic traits of metabolic syndrome.”

The meeting was held by the American Thyroid Association, Asia-Oceania Thyroid Association, European Thyroid Association, and Latin American Thyroid Society. Dr. Brenta did not identify any conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @karioakes

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – Patients with low thyroid function may experience a “double whammy” of hypothyroidism and metabolic syndrome.

Even subclinical hypothyroidism affects many metabolic pathways that can contribute to deranged glucose and lipid metabolism, raising the risk of metabolic syndrome, according to Dr. Gabriela Brenta of the department of endocrinology at the Dr. Cesar Milstein Hospital in Buenos Aires. Though some mechanisms are incompletely understood, the association is clear enough to warrant screening all metabolic syndrome patients for hypothyroidism, she said.

Dr. Brenta described the recent work she and others have completed in the field. Basic science work revealed some early clues. For example, those who studied the effects of acute thyroid hormone withdrawal on patients with no thyroid gland found that these patients saw a rapid rise in insulin resistance. It’s known that even subclinical insulin resistance can lead to impaired glucose metabolism, making it logical to follow both normal and deranged metabolic pathways to help sort out the relationship between thyroid dysfunction and impaired glucose metabolism, she reported at the International Thyroid Congress.

Hypothyroidism can affect glucose homeostasis through multiple mechanisms, said Dr. Brenta. Firstly, hypothyroidism can lead to decreased hepatic gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis. Hypothyroidism also can lead to reduced baseline plasma insulin levels and increased postglucose insulin secretion. In the peripheral tissues, hypothyroidism can interfere with glucose metabolism and disposal. All of these mechanisms can decrease hepatic glucose metabolism and lead to a postabsorptive hyperglycemia state, said Dr. Brenta, noting: “Insulin resistance is in some way the backbone of metabolic syndrome.”

Lipid metabolism is also affected by subclinical hypothyroidism, which can decrease expression of mRNA for LDL-C receptors, leading to LDL-C receptor down-regulation. With fewer receptors available, serum levels of LDL-C increase, with resultant increased susceptibility to oxidative effects and increased foam cell generation.

Dr. Brenta cited her earlier work showing that “triglyceride enrichment of LDL particles correlates with lower hepatic lipase activity” for individuals with subclinical hypothyroidism, with significantly lower hepatic lipase activity and a higher LDL-C to triglyceride ratio for those patients than for controls (Thyroid. 2007 May;17[5]:453-60). Overall, in hypothyroidism, “LDL particles are exposed to more substances that make them more atherogenic with decreased degradation and increased half-life,” said Dr. Brenta.

The increased risk for hypertension in both subclinical and overt hypothyroidism may be related, in part, to the fact that triiodothyronine deficiency can contribute to endothelial dysfunction. The relationship between subclinical hypothyroidism and hypertension was confirmed in a 2011 meta-analysis, said Dr. Brenta (Hypertens Res. 2011 Oct;34[10]:1098-105).

Though many factors contribute to obesity and thyroid function alone does not regulate body weight, a large population-based Danish study found that “even mild elevations of TSH are important for body weight,” said Dr. Brenta. The relationship is complex and bidirectional – a classic “chicken and egg” story – since obesity also may modulate TSH, she said; “however, we must not forget the ample literature on low levels of thyroid hormones reducing resting energy expenditure” (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005 Jul;90[7]:4019-24).

Even though TSH tends to rise naturally through the lifespan, the association between elevated TSH and increased risk of metabolic syndrome held true even for older patients in one study, with “each one unit increase in TSH predicting a 3% increase in the odds of metabolic syndrome,” even after adjustment for age, BMI, and HOMA-IR status, among other variables, said Dr. Brenta (Clin Endocrinol [Oxf]. 2012 Jun;76[6]:911-8).

Advocating for universal screening for hypothyroidism among patients with metabolic syndrome, Dr. Brenta said that “hypothyroid disturbances are associated with an adverse metabolic profile, and even low normal TSH levels are associated with the metabolic traits of metabolic syndrome.”

The meeting was held by the American Thyroid Association, Asia-Oceania Thyroid Association, European Thyroid Association, and Latin American Thyroid Society. Dr. Brenta did not identify any conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ITC 2015

For weight loss, low-fat diet is least effective intervention

A low-fat diet was the least effective form of weight loss intervention and showed superior weight loss only when compared with a usual diet, according to a systematic review by Dr. Deirdre Tobias and her associates.

A total of 53 studies were included in the review and meta-analysis. Low-carbohydrate diets were more effective than low-fat diets, with a weighted mean difference of 1.15 kg. There was no significant difference between low-fat diets and other higher-fat weight loss interventions. A low-fat diet was more effective then remaining on a usual diet, with a weighted mean difference of 5.41 kg.

While on average, low-fat and higher-fat weight loss interventions were statistically similar, if low-fat and higher-fat groups differed in calories obtained from fat by more than 5% or in serum triglyceride levels of at least 0.06 mmol/L, higher-fat interventions became more effective, with weighted mean differences of 1.04 kg and 1.38 kg, respectively, the investigators found.

While low-carbohydrate diets were statistically more effective than were low-fat diets, Dr. Kevin Hall of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, Md., wrote in a related comment, “Consider the magnitude of the benefit: Participants prescribed low-carbohydrate diets lost only about 1 kg of additional weight after 1 year compared with those advised to consume low-fat diets. Although statistically significant, such a minuscule difference in weight loss is clinically meaningless. Furthermore, irrespective of the diet prescription, the overall average weight loss in trials testing interventions designed to reduce bodyweight was unimpressive.”

Find the full study in the Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology (doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587[15]00367-8).

A low-fat diet was the least effective form of weight loss intervention and showed superior weight loss only when compared with a usual diet, according to a systematic review by Dr. Deirdre Tobias and her associates.

A total of 53 studies were included in the review and meta-analysis. Low-carbohydrate diets were more effective than low-fat diets, with a weighted mean difference of 1.15 kg. There was no significant difference between low-fat diets and other higher-fat weight loss interventions. A low-fat diet was more effective then remaining on a usual diet, with a weighted mean difference of 5.41 kg.

While on average, low-fat and higher-fat weight loss interventions were statistically similar, if low-fat and higher-fat groups differed in calories obtained from fat by more than 5% or in serum triglyceride levels of at least 0.06 mmol/L, higher-fat interventions became more effective, with weighted mean differences of 1.04 kg and 1.38 kg, respectively, the investigators found.

While low-carbohydrate diets were statistically more effective than were low-fat diets, Dr. Kevin Hall of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, Md., wrote in a related comment, “Consider the magnitude of the benefit: Participants prescribed low-carbohydrate diets lost only about 1 kg of additional weight after 1 year compared with those advised to consume low-fat diets. Although statistically significant, such a minuscule difference in weight loss is clinically meaningless. Furthermore, irrespective of the diet prescription, the overall average weight loss in trials testing interventions designed to reduce bodyweight was unimpressive.”

Find the full study in the Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology (doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587[15]00367-8).

A low-fat diet was the least effective form of weight loss intervention and showed superior weight loss only when compared with a usual diet, according to a systematic review by Dr. Deirdre Tobias and her associates.

A total of 53 studies were included in the review and meta-analysis. Low-carbohydrate diets were more effective than low-fat diets, with a weighted mean difference of 1.15 kg. There was no significant difference between low-fat diets and other higher-fat weight loss interventions. A low-fat diet was more effective then remaining on a usual diet, with a weighted mean difference of 5.41 kg.

While on average, low-fat and higher-fat weight loss interventions were statistically similar, if low-fat and higher-fat groups differed in calories obtained from fat by more than 5% or in serum triglyceride levels of at least 0.06 mmol/L, higher-fat interventions became more effective, with weighted mean differences of 1.04 kg and 1.38 kg, respectively, the investigators found.

While low-carbohydrate diets were statistically more effective than were low-fat diets, Dr. Kevin Hall of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, Md., wrote in a related comment, “Consider the magnitude of the benefit: Participants prescribed low-carbohydrate diets lost only about 1 kg of additional weight after 1 year compared with those advised to consume low-fat diets. Although statistically significant, such a minuscule difference in weight loss is clinically meaningless. Furthermore, irrespective of the diet prescription, the overall average weight loss in trials testing interventions designed to reduce bodyweight was unimpressive.”

Find the full study in the Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology (doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587[15]00367-8).

USPSTF recommends glucose screening in overweight or obese adults

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has added a B-level recommendation for abnormal blood glucose screening in overweight or obese adults aged 40-70 years as a part of their cardiovascular risk assessment. The guidelines were published in the Annals of Internal Medicine on Oct 26.

“Losing weight reduces the chances of developing diabetes, which is why our recommendation focuses on diet and exercise. Patients who have abnormal blood sugar levels can be referred to programs that help them eat a more healthful diet and exercise more often,” noted task force member Dr. William Phillips of the departments of health services and epidemiology at the University of Washington, Seattle, in a statement.

An estimated one-quarter of the cardiovascular disease (CVD) deaths are considered preventable. Likewise, abnormal blood glucose metabolism is considered a modifiable risk factor for CVD.

With the exception for some USPSTF recommendations involving breast cancer screening, the Affordable Care Act mandates that USPSTF recommendations with an A or B rating be covered by health insurance.

In 2008, the USPSTF gave a grade B-level recommendation to screening for type 2 diabetes in asymptomatic adults with treated or untreated hypertension (blood pressure greater than 135/80 mm Hg). They noted insufficient evidence to screen asymptomatic adults without a history of hypertension at that time.

The task force reviewed previous and new evidence on screening for type 2 diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, and impaired glucose tolerance and whether measurement of glucose resulted in improved outcomes and if interventions delayed progression to diabetes. Likewise, they wanted to know what, if any, harms could arise from screening for abnormal glucose metabolism.

The updated USPSTF recommendations call for the following:

• Screening for abnormal blood glucose in obese or overweight adults aged 40-70 years (Grade B).

• For those with abnormal glucose, referral for or offer intensive behavioral counseling on physical activity and healthful diet.

• Risk factors for abnormal glucose metabolism include physical inactivity, smoking, higher percentage of abdominal fat, overweight, and obesity. It is also often associated with other CVD risk factors such as hypertension and hyperlipidemia.

• Screening tests include: hemoglobin A1c, oral glucose tolerance test, or fasting plasma glucose with repeat testing for confirmation.

• No optimal screening interval was noted, but 3 years may be reasonable, based on previous studies.

• Interventions recommended included counseling on physical activity and a healthful diet, with insufficient evidence that medication has the same benefit to a behavioral approach.

The task force noted inadequate direct evidence that glucose measurement lessens CVD morbidity or mortality. However, they previously found evidence that intensive behavioral interventions in those at increased risk for CVD moderately lowered their CVD risk. This benefit was reported in those who are overweight or obese, have dyslipidemia, have hypertension, and/or have impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose. Further, the task force highlighted studies that showed moderate reduction in progression to diabetes with lifestyle interventions in people with impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose. They found that lifestyle interventions are more effective than metformin use.

Likewise, the task force noted little possible harm to initiating lifestyle intervention in order to reduce progression to diabetes and small to moderate harm in the use of drug therapy for diabetes prevention.

Furthermore, the recommendations include screening for obesity and referral to intensive behavioral interventions in those with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or more or a BMI greater than 25 kg/m2 and CVD risk factors.

Lifestyle interventions recommended for those at increased risk for type 2 diabetes include a combination of physical activity and dietary interventions. For example, among the effective approaches recommended are participating in individual and group sessions, setting weight loss goals, working with a trained diet or exercise counselor, and individualizing exercise or diet plans.

“The USPSTF assessed the overall benefit of screening for [impaired fasting glucose], [impaired glucose tolerance], and diabetes to be moderate. The effects of lifestyle interventions to prevent or delay progression to diabetes were consistent across a substantive body of literature.”

The USPSTF is funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has added a B-level recommendation for abnormal blood glucose screening in overweight or obese adults aged 40-70 years as a part of their cardiovascular risk assessment. The guidelines were published in the Annals of Internal Medicine on Oct 26.

“Losing weight reduces the chances of developing diabetes, which is why our recommendation focuses on diet and exercise. Patients who have abnormal blood sugar levels can be referred to programs that help them eat a more healthful diet and exercise more often,” noted task force member Dr. William Phillips of the departments of health services and epidemiology at the University of Washington, Seattle, in a statement.

An estimated one-quarter of the cardiovascular disease (CVD) deaths are considered preventable. Likewise, abnormal blood glucose metabolism is considered a modifiable risk factor for CVD.

With the exception for some USPSTF recommendations involving breast cancer screening, the Affordable Care Act mandates that USPSTF recommendations with an A or B rating be covered by health insurance.

In 2008, the USPSTF gave a grade B-level recommendation to screening for type 2 diabetes in asymptomatic adults with treated or untreated hypertension (blood pressure greater than 135/80 mm Hg). They noted insufficient evidence to screen asymptomatic adults without a history of hypertension at that time.

The task force reviewed previous and new evidence on screening for type 2 diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, and impaired glucose tolerance and whether measurement of glucose resulted in improved outcomes and if interventions delayed progression to diabetes. Likewise, they wanted to know what, if any, harms could arise from screening for abnormal glucose metabolism.

The updated USPSTF recommendations call for the following:

• Screening for abnormal blood glucose in obese or overweight adults aged 40-70 years (Grade B).

• For those with abnormal glucose, referral for or offer intensive behavioral counseling on physical activity and healthful diet.

• Risk factors for abnormal glucose metabolism include physical inactivity, smoking, higher percentage of abdominal fat, overweight, and obesity. It is also often associated with other CVD risk factors such as hypertension and hyperlipidemia.

• Screening tests include: hemoglobin A1c, oral glucose tolerance test, or fasting plasma glucose with repeat testing for confirmation.

• No optimal screening interval was noted, but 3 years may be reasonable, based on previous studies.

• Interventions recommended included counseling on physical activity and a healthful diet, with insufficient evidence that medication has the same benefit to a behavioral approach.

The task force noted inadequate direct evidence that glucose measurement lessens CVD morbidity or mortality. However, they previously found evidence that intensive behavioral interventions in those at increased risk for CVD moderately lowered their CVD risk. This benefit was reported in those who are overweight or obese, have dyslipidemia, have hypertension, and/or have impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose. Further, the task force highlighted studies that showed moderate reduction in progression to diabetes with lifestyle interventions in people with impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose. They found that lifestyle interventions are more effective than metformin use.

Likewise, the task force noted little possible harm to initiating lifestyle intervention in order to reduce progression to diabetes and small to moderate harm in the use of drug therapy for diabetes prevention.

Furthermore, the recommendations include screening for obesity and referral to intensive behavioral interventions in those with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or more or a BMI greater than 25 kg/m2 and CVD risk factors.

Lifestyle interventions recommended for those at increased risk for type 2 diabetes include a combination of physical activity and dietary interventions. For example, among the effective approaches recommended are participating in individual and group sessions, setting weight loss goals, working with a trained diet or exercise counselor, and individualizing exercise or diet plans.

“The USPSTF assessed the overall benefit of screening for [impaired fasting glucose], [impaired glucose tolerance], and diabetes to be moderate. The effects of lifestyle interventions to prevent or delay progression to diabetes were consistent across a substantive body of literature.”

The USPSTF is funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has added a B-level recommendation for abnormal blood glucose screening in overweight or obese adults aged 40-70 years as a part of their cardiovascular risk assessment. The guidelines were published in the Annals of Internal Medicine on Oct 26.

“Losing weight reduces the chances of developing diabetes, which is why our recommendation focuses on diet and exercise. Patients who have abnormal blood sugar levels can be referred to programs that help them eat a more healthful diet and exercise more often,” noted task force member Dr. William Phillips of the departments of health services and epidemiology at the University of Washington, Seattle, in a statement.

An estimated one-quarter of the cardiovascular disease (CVD) deaths are considered preventable. Likewise, abnormal blood glucose metabolism is considered a modifiable risk factor for CVD.

With the exception for some USPSTF recommendations involving breast cancer screening, the Affordable Care Act mandates that USPSTF recommendations with an A or B rating be covered by health insurance.

In 2008, the USPSTF gave a grade B-level recommendation to screening for type 2 diabetes in asymptomatic adults with treated or untreated hypertension (blood pressure greater than 135/80 mm Hg). They noted insufficient evidence to screen asymptomatic adults without a history of hypertension at that time.

The task force reviewed previous and new evidence on screening for type 2 diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, and impaired glucose tolerance and whether measurement of glucose resulted in improved outcomes and if interventions delayed progression to diabetes. Likewise, they wanted to know what, if any, harms could arise from screening for abnormal glucose metabolism.

The updated USPSTF recommendations call for the following:

• Screening for abnormal blood glucose in obese or overweight adults aged 40-70 years (Grade B).

• For those with abnormal glucose, referral for or offer intensive behavioral counseling on physical activity and healthful diet.

• Risk factors for abnormal glucose metabolism include physical inactivity, smoking, higher percentage of abdominal fat, overweight, and obesity. It is also often associated with other CVD risk factors such as hypertension and hyperlipidemia.

• Screening tests include: hemoglobin A1c, oral glucose tolerance test, or fasting plasma glucose with repeat testing for confirmation.

• No optimal screening interval was noted, but 3 years may be reasonable, based on previous studies.

• Interventions recommended included counseling on physical activity and a healthful diet, with insufficient evidence that medication has the same benefit to a behavioral approach.

The task force noted inadequate direct evidence that glucose measurement lessens CVD morbidity or mortality. However, they previously found evidence that intensive behavioral interventions in those at increased risk for CVD moderately lowered their CVD risk. This benefit was reported in those who are overweight or obese, have dyslipidemia, have hypertension, and/or have impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose. Further, the task force highlighted studies that showed moderate reduction in progression to diabetes with lifestyle interventions in people with impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose. They found that lifestyle interventions are more effective than metformin use.

Likewise, the task force noted little possible harm to initiating lifestyle intervention in order to reduce progression to diabetes and small to moderate harm in the use of drug therapy for diabetes prevention.

Furthermore, the recommendations include screening for obesity and referral to intensive behavioral interventions in those with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or more or a BMI greater than 25 kg/m2 and CVD risk factors.

Lifestyle interventions recommended for those at increased risk for type 2 diabetes include a combination of physical activity and dietary interventions. For example, among the effective approaches recommended are participating in individual and group sessions, setting weight loss goals, working with a trained diet or exercise counselor, and individualizing exercise or diet plans.

“The USPSTF assessed the overall benefit of screening for [impaired fasting glucose], [impaired glucose tolerance], and diabetes to be moderate. The effects of lifestyle interventions to prevent or delay progression to diabetes were consistent across a substantive body of literature.”

The USPSTF is funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

EADV: Hidradenitis suppurativa carries high cardiovascular risk

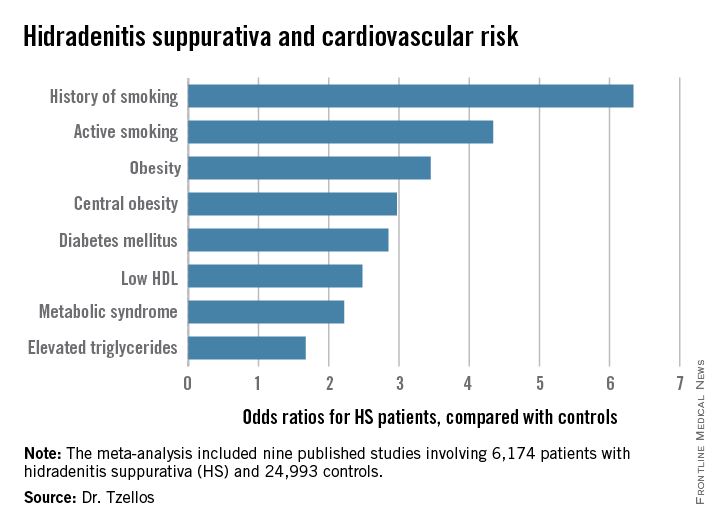

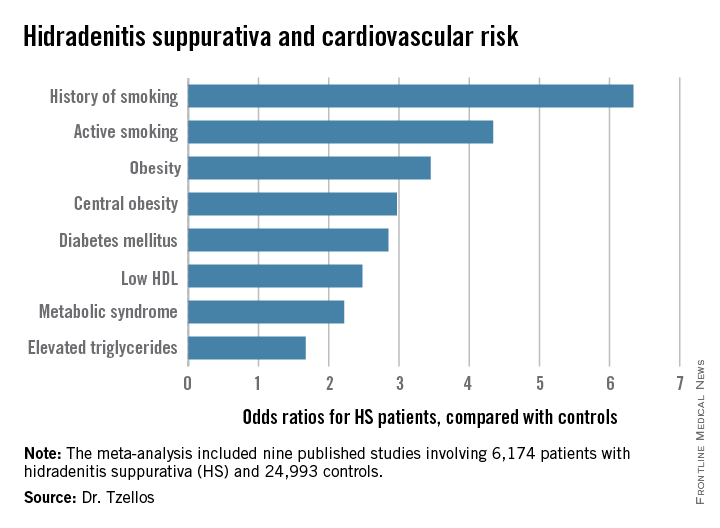

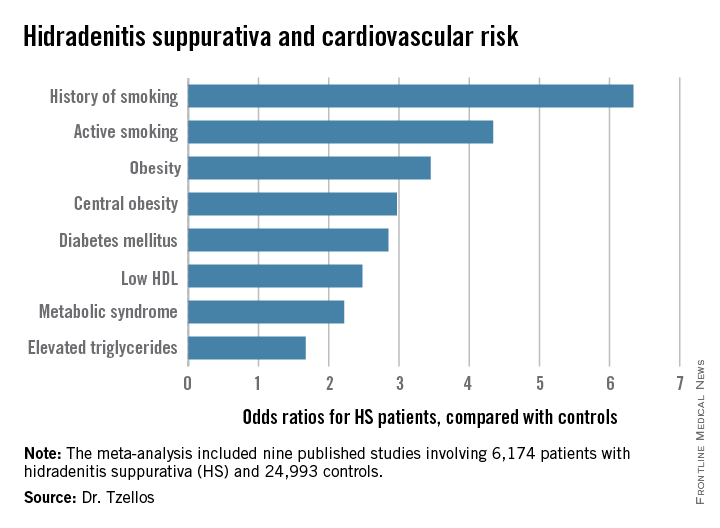

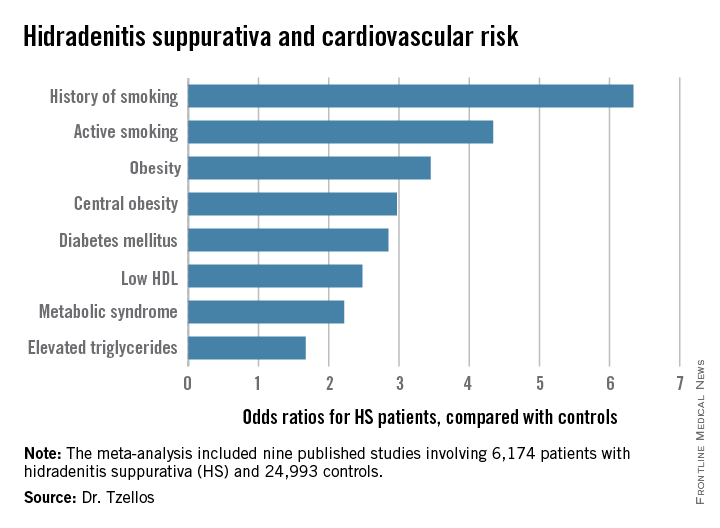

COPENHAGEN – Hidradenitis suppurativa, a common, chronic, inflammatory scarring skin disease of the hair follicles, is a red flag signaling elevated levels of multiple cardiovascular risk factors, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis.

“The need for screening of hidradenitis suppurativa patients for modifiable cardiovascular risk is emphasized,” Dr. Thrasyvoulos Tzellos said in presenting the findings at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

For such a common and dramatically destructive disease, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) was underresearched until recently. Investigative interest grew as the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab (Humira) underwent development as a novel therapy for what has been traditionally a notoriously difficult to treat disease. The biologic agent received Food and Drug Administration marketing approval in October as the first and only approved treatment for HS.

Dr. Tzellos’s meta-analysis included nine published studies totaling 6,174 HS patients and 24,993 controls. Five studies were case control, and the other four were cross sectional. An indicator of the recent explosive research interest in HS can be seen in the fact that 80% of all the HS patients included in the meta-analysis come from two studies published within just the last year, one from Massachusetts General Hospital (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Dec;71[6]:1144-50) and the other from Israel (Br J Dermatol. 2015 Aug;173[2]:464-70).

Not all the studies examined the same cardiovascular risk factors. For example, only six of nine studies looked at diabetes mellitus as an endpoint. Of those studies that did, diabetes occurred in 856 of 5,685 HS patients, a rate 2.85-fold higher than in controls, according to Dr. Tzellos of University Hospital of North Norway in Troms.

The only cardiovascular risk factor examined that was not significantly more common among patients with HS than controls was hypertension. The 1.57-fold increased likelihood of hypertension among HS patients didn’t achieve statistical significance.

Although patients whose HS was treated exclusively in outpatient settings had significantly higher levels of cardiovascular risk factors than did controls, risk levels were consistently higher still in patients who had been hospitalized for HS.

A meta-analysis such as this cannot address causality, leaving open the question of whether increased cardiovascular risk factors are intrinsic to HS, or the debilitating recurrent skin disease causes affected patients to take a defeatest attitude toward maintenance of a healthy lifestyle.

Dr. Tzellos reported having no financial conflicts regarding this meta-analysis, carried out with academic funding.

COPENHAGEN – Hidradenitis suppurativa, a common, chronic, inflammatory scarring skin disease of the hair follicles, is a red flag signaling elevated levels of multiple cardiovascular risk factors, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis.

“The need for screening of hidradenitis suppurativa patients for modifiable cardiovascular risk is emphasized,” Dr. Thrasyvoulos Tzellos said in presenting the findings at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

For such a common and dramatically destructive disease, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) was underresearched until recently. Investigative interest grew as the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab (Humira) underwent development as a novel therapy for what has been traditionally a notoriously difficult to treat disease. The biologic agent received Food and Drug Administration marketing approval in October as the first and only approved treatment for HS.

Dr. Tzellos’s meta-analysis included nine published studies totaling 6,174 HS patients and 24,993 controls. Five studies were case control, and the other four were cross sectional. An indicator of the recent explosive research interest in HS can be seen in the fact that 80% of all the HS patients included in the meta-analysis come from two studies published within just the last year, one from Massachusetts General Hospital (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Dec;71[6]:1144-50) and the other from Israel (Br J Dermatol. 2015 Aug;173[2]:464-70).

Not all the studies examined the same cardiovascular risk factors. For example, only six of nine studies looked at diabetes mellitus as an endpoint. Of those studies that did, diabetes occurred in 856 of 5,685 HS patients, a rate 2.85-fold higher than in controls, according to Dr. Tzellos of University Hospital of North Norway in Troms.

The only cardiovascular risk factor examined that was not significantly more common among patients with HS than controls was hypertension. The 1.57-fold increased likelihood of hypertension among HS patients didn’t achieve statistical significance.

Although patients whose HS was treated exclusively in outpatient settings had significantly higher levels of cardiovascular risk factors than did controls, risk levels were consistently higher still in patients who had been hospitalized for HS.

A meta-analysis such as this cannot address causality, leaving open the question of whether increased cardiovascular risk factors are intrinsic to HS, or the debilitating recurrent skin disease causes affected patients to take a defeatest attitude toward maintenance of a healthy lifestyle.

Dr. Tzellos reported having no financial conflicts regarding this meta-analysis, carried out with academic funding.

COPENHAGEN – Hidradenitis suppurativa, a common, chronic, inflammatory scarring skin disease of the hair follicles, is a red flag signaling elevated levels of multiple cardiovascular risk factors, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis.

“The need for screening of hidradenitis suppurativa patients for modifiable cardiovascular risk is emphasized,” Dr. Thrasyvoulos Tzellos said in presenting the findings at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

For such a common and dramatically destructive disease, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) was underresearched until recently. Investigative interest grew as the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab (Humira) underwent development as a novel therapy for what has been traditionally a notoriously difficult to treat disease. The biologic agent received Food and Drug Administration marketing approval in October as the first and only approved treatment for HS.

Dr. Tzellos’s meta-analysis included nine published studies totaling 6,174 HS patients and 24,993 controls. Five studies were case control, and the other four were cross sectional. An indicator of the recent explosive research interest in HS can be seen in the fact that 80% of all the HS patients included in the meta-analysis come from two studies published within just the last year, one from Massachusetts General Hospital (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Dec;71[6]:1144-50) and the other from Israel (Br J Dermatol. 2015 Aug;173[2]:464-70).

Not all the studies examined the same cardiovascular risk factors. For example, only six of nine studies looked at diabetes mellitus as an endpoint. Of those studies that did, diabetes occurred in 856 of 5,685 HS patients, a rate 2.85-fold higher than in controls, according to Dr. Tzellos of University Hospital of North Norway in Troms.

The only cardiovascular risk factor examined that was not significantly more common among patients with HS than controls was hypertension. The 1.57-fold increased likelihood of hypertension among HS patients didn’t achieve statistical significance.

Although patients whose HS was treated exclusively in outpatient settings had significantly higher levels of cardiovascular risk factors than did controls, risk levels were consistently higher still in patients who had been hospitalized for HS.

A meta-analysis such as this cannot address causality, leaving open the question of whether increased cardiovascular risk factors are intrinsic to HS, or the debilitating recurrent skin disease causes affected patients to take a defeatest attitude toward maintenance of a healthy lifestyle.

Dr. Tzellos reported having no financial conflicts regarding this meta-analysis, carried out with academic funding.

AT THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Be vigilant in screening for modifiable cardiovascular risk factors in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa.

Major finding: Hidradenitis suppurativa patients were 2.85-fold more likely than controls to have diabetes, 2.22-fold more likely to have metabolic syndrome, and 4.34-fold more likely to be active smokers.

Data source: A meta-analysis of nine published studies totaling 6,174 hidradenitis suppurativa patients and 24,993 controls.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding this meta-analysis, carried out with academic funding.

Study examines factors driving diabetes overtreatment

Misconceptions and misplaced concerns held by a significant minority of care providers will likely exacerbate the challenge of addressing costly, potentially dangerous drug overutilization in certain high-risk populations of older diabetic patients, according to research published online Oct. 26 in JAMA Internal Medicine (doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5950).

The study surveyed a randomized sample of 594 practicing non-trainee Department of Veterans Affairs primary care professionals (physicians, nurses, physician assistants).

Dr. Tanner J. Caverly of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues identified provider resistance as a key hurdle to broader acceptance of hemoglobin A1c recommendations from the American Geriatrics Society’s Choosing Wisely diabetes treatment guidelines. The guidelines, revised in 2015,, reflect an emerging clinical consensus that it is safe to ease stringent blood glucose control for older type 2 diabetes patients with an HbA1c level lower than 7.5%, renal disease, or dementia.

Subjects answered a series of questions regarding a hypothetical scenario (77-year-old man with long-standing type 2 diabetes at high risk for hypoglycemia, 6.5% HbA1c, severe kidney disease, taking 10 mg of glipizide twice-daily) in which, according to the Choosing Wisely recommendation, racheting down the intensity of treatment is advised. Findings, however, indicated that 38.6% of respondents expressed the belief that continued strict blood glucose control would be beneficial to the theoretical patient, 44.9% did not associate strict control with any increased risk of danger or harm, 42.1% cited concerns that lessening treatment intensity would result in HbA1c levels outside of those stipulated by current performance metrics, and 23.5% feared that easing back on treatment intensity would open them to future malpractice claims.

As a result of the above-mentioned and other factors, 28.7% of PCPs surveyed characterized the adherence to Choosing Wisely’s HbA1c recommendation as “difficult” or “very difficult.” Researchers then assessed which provider concerns were associated with the greatest likelihood of noncompliance. Providers who linked tight glucose control with patient benefit (P = .009) and those who worried about the danger of increased malpractice claims (P = .02) were most likely to report having difficulties following the Choosing Wisely recommendations.

The investigators suggested a number of possible measures that could “improve prescribing practices and prevent many adverse events in older patients with diabetes,” including national multidisciplinary safety initiatives (such as the Million Hearts Campaign), establishment of national guidelines, and creation of performance measures which incentivize adoption of less intense treatment where appropriate.

Misconceptions and misplaced concerns held by a significant minority of care providers will likely exacerbate the challenge of addressing costly, potentially dangerous drug overutilization in certain high-risk populations of older diabetic patients, according to research published online Oct. 26 in JAMA Internal Medicine (doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5950).

The study surveyed a randomized sample of 594 practicing non-trainee Department of Veterans Affairs primary care professionals (physicians, nurses, physician assistants).

Dr. Tanner J. Caverly of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues identified provider resistance as a key hurdle to broader acceptance of hemoglobin A1c recommendations from the American Geriatrics Society’s Choosing Wisely diabetes treatment guidelines. The guidelines, revised in 2015,, reflect an emerging clinical consensus that it is safe to ease stringent blood glucose control for older type 2 diabetes patients with an HbA1c level lower than 7.5%, renal disease, or dementia.

Subjects answered a series of questions regarding a hypothetical scenario (77-year-old man with long-standing type 2 diabetes at high risk for hypoglycemia, 6.5% HbA1c, severe kidney disease, taking 10 mg of glipizide twice-daily) in which, according to the Choosing Wisely recommendation, racheting down the intensity of treatment is advised. Findings, however, indicated that 38.6% of respondents expressed the belief that continued strict blood glucose control would be beneficial to the theoretical patient, 44.9% did not associate strict control with any increased risk of danger or harm, 42.1% cited concerns that lessening treatment intensity would result in HbA1c levels outside of those stipulated by current performance metrics, and 23.5% feared that easing back on treatment intensity would open them to future malpractice claims.

As a result of the above-mentioned and other factors, 28.7% of PCPs surveyed characterized the adherence to Choosing Wisely’s HbA1c recommendation as “difficult” or “very difficult.” Researchers then assessed which provider concerns were associated with the greatest likelihood of noncompliance. Providers who linked tight glucose control with patient benefit (P = .009) and those who worried about the danger of increased malpractice claims (P = .02) were most likely to report having difficulties following the Choosing Wisely recommendations.

The investigators suggested a number of possible measures that could “improve prescribing practices and prevent many adverse events in older patients with diabetes,” including national multidisciplinary safety initiatives (such as the Million Hearts Campaign), establishment of national guidelines, and creation of performance measures which incentivize adoption of less intense treatment where appropriate.

Misconceptions and misplaced concerns held by a significant minority of care providers will likely exacerbate the challenge of addressing costly, potentially dangerous drug overutilization in certain high-risk populations of older diabetic patients, according to research published online Oct. 26 in JAMA Internal Medicine (doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5950).

The study surveyed a randomized sample of 594 practicing non-trainee Department of Veterans Affairs primary care professionals (physicians, nurses, physician assistants).

Dr. Tanner J. Caverly of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues identified provider resistance as a key hurdle to broader acceptance of hemoglobin A1c recommendations from the American Geriatrics Society’s Choosing Wisely diabetes treatment guidelines. The guidelines, revised in 2015,, reflect an emerging clinical consensus that it is safe to ease stringent blood glucose control for older type 2 diabetes patients with an HbA1c level lower than 7.5%, renal disease, or dementia.

Subjects answered a series of questions regarding a hypothetical scenario (77-year-old man with long-standing type 2 diabetes at high risk for hypoglycemia, 6.5% HbA1c, severe kidney disease, taking 10 mg of glipizide twice-daily) in which, according to the Choosing Wisely recommendation, racheting down the intensity of treatment is advised. Findings, however, indicated that 38.6% of respondents expressed the belief that continued strict blood glucose control would be beneficial to the theoretical patient, 44.9% did not associate strict control with any increased risk of danger or harm, 42.1% cited concerns that lessening treatment intensity would result in HbA1c levels outside of those stipulated by current performance metrics, and 23.5% feared that easing back on treatment intensity would open them to future malpractice claims.

As a result of the above-mentioned and other factors, 28.7% of PCPs surveyed characterized the adherence to Choosing Wisely’s HbA1c recommendation as “difficult” or “very difficult.” Researchers then assessed which provider concerns were associated with the greatest likelihood of noncompliance. Providers who linked tight glucose control with patient benefit (P = .009) and those who worried about the danger of increased malpractice claims (P = .02) were most likely to report having difficulties following the Choosing Wisely recommendations.

The investigators suggested a number of possible measures that could “improve prescribing practices and prevent many adverse events in older patients with diabetes,” including national multidisciplinary safety initiatives (such as the Million Hearts Campaign), establishment of national guidelines, and creation of performance measures which incentivize adoption of less intense treatment where appropriate.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Entrenched provider attitudes may contribute to overtreatment of blood glucose levels in patients at elevated risk for hypoglycemia and related adverse events.

Major finding: Of survey respondents, 28.7% said they would find it difficult or very difficult to comply with the American Geriatrics Society’s Choosing Wisely recommendation to “avoid using medications other than metformin to achieve HbA1c less than 7.5% in most older adults.”

Data source: A randomized, nationwide survey of 594 practicing non-trainee Department of Veterans Affairs physicians, nurses, and physician assistants.