User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Lower rates of patient satisfaction may predict readmission

Clinical question: Do higher rates of patient satisfaction lead to lower rates of hospital readmission?

Background: Readmissions account for 32.1% of total health care expenditures in the United States, of which 15%-20% are considered potentially preventable. Multiple studies have examined a variety of possible indicators of readmission, but rarely has patient perspective prior to discharge been examined.

Study design: Thematic interview and questionnaire.

Setting: Two inpatient medical units at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Synopsis: 846 patients were enrolled during their index admission with 201 of these patients being readmitted within 30 days of discharge. During the index admission, the patients completed a questionnaire developed by the authors and underwent a formal, thematic interview with identification of core domains performed by trained research coordinators. The primary outcome was 30-day readmission. Readmitted patients were less likely to have reported being “very satisfied” with their overall care (67.7% vs. 76.4%; P = .045) and were less likely to have reported that physicians “always listened” to them (65.7% vs. 73.2%; P = .048). Interestingly, if health care providers discussed the possible need for help after hospital stay, the patient had an increased risk of readmission (adjusted odds ratio, 1.56; 95% confidence interval, 1.02-2.39; P = .04) and patients who predicted they were “very likely” to require readmission were not more likely to be readmitted (aOR, 1.35; 95% CI, 0.83-2.19; P = .22). The major limitations of this study are that researchers interviewed only English-speaking patients who were able to participate in an in-depth interview and survey, perhaps resulting in a healthier-patient bias, as well as an inability to capture hospital admission at other institutions. Additionally, these patients are drawn from a tertiary-care service designed to care for medically complex cases and may not be generalizable to larger populations.

Bottom line: Lower rates of 30-day hospital readmission were associated with higher rates of patient satisfaction and a higher level of patient perception that providers were listening to them.

Citation: Carter J et al. The association between patient experience factors and likelihood of 30-day readmission: A prospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018 Sep;27:683-90.

Dr. Imber is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of New Mexico.

Clinical question: Do higher rates of patient satisfaction lead to lower rates of hospital readmission?

Background: Readmissions account for 32.1% of total health care expenditures in the United States, of which 15%-20% are considered potentially preventable. Multiple studies have examined a variety of possible indicators of readmission, but rarely has patient perspective prior to discharge been examined.

Study design: Thematic interview and questionnaire.

Setting: Two inpatient medical units at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Synopsis: 846 patients were enrolled during their index admission with 201 of these patients being readmitted within 30 days of discharge. During the index admission, the patients completed a questionnaire developed by the authors and underwent a formal, thematic interview with identification of core domains performed by trained research coordinators. The primary outcome was 30-day readmission. Readmitted patients were less likely to have reported being “very satisfied” with their overall care (67.7% vs. 76.4%; P = .045) and were less likely to have reported that physicians “always listened” to them (65.7% vs. 73.2%; P = .048). Interestingly, if health care providers discussed the possible need for help after hospital stay, the patient had an increased risk of readmission (adjusted odds ratio, 1.56; 95% confidence interval, 1.02-2.39; P = .04) and patients who predicted they were “very likely” to require readmission were not more likely to be readmitted (aOR, 1.35; 95% CI, 0.83-2.19; P = .22). The major limitations of this study are that researchers interviewed only English-speaking patients who were able to participate in an in-depth interview and survey, perhaps resulting in a healthier-patient bias, as well as an inability to capture hospital admission at other institutions. Additionally, these patients are drawn from a tertiary-care service designed to care for medically complex cases and may not be generalizable to larger populations.

Bottom line: Lower rates of 30-day hospital readmission were associated with higher rates of patient satisfaction and a higher level of patient perception that providers were listening to them.

Citation: Carter J et al. The association between patient experience factors and likelihood of 30-day readmission: A prospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018 Sep;27:683-90.

Dr. Imber is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of New Mexico.

Clinical question: Do higher rates of patient satisfaction lead to lower rates of hospital readmission?

Background: Readmissions account for 32.1% of total health care expenditures in the United States, of which 15%-20% are considered potentially preventable. Multiple studies have examined a variety of possible indicators of readmission, but rarely has patient perspective prior to discharge been examined.

Study design: Thematic interview and questionnaire.

Setting: Two inpatient medical units at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Synopsis: 846 patients were enrolled during their index admission with 201 of these patients being readmitted within 30 days of discharge. During the index admission, the patients completed a questionnaire developed by the authors and underwent a formal, thematic interview with identification of core domains performed by trained research coordinators. The primary outcome was 30-day readmission. Readmitted patients were less likely to have reported being “very satisfied” with their overall care (67.7% vs. 76.4%; P = .045) and were less likely to have reported that physicians “always listened” to them (65.7% vs. 73.2%; P = .048). Interestingly, if health care providers discussed the possible need for help after hospital stay, the patient had an increased risk of readmission (adjusted odds ratio, 1.56; 95% confidence interval, 1.02-2.39; P = .04) and patients who predicted they were “very likely” to require readmission were not more likely to be readmitted (aOR, 1.35; 95% CI, 0.83-2.19; P = .22). The major limitations of this study are that researchers interviewed only English-speaking patients who were able to participate in an in-depth interview and survey, perhaps resulting in a healthier-patient bias, as well as an inability to capture hospital admission at other institutions. Additionally, these patients are drawn from a tertiary-care service designed to care for medically complex cases and may not be generalizable to larger populations.

Bottom line: Lower rates of 30-day hospital readmission were associated with higher rates of patient satisfaction and a higher level of patient perception that providers were listening to them.

Citation: Carter J et al. The association between patient experience factors and likelihood of 30-day readmission: A prospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018 Sep;27:683-90.

Dr. Imber is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of New Mexico.

p-TIPS improves outcomes for high-risk variceal bleeding

Background: Acute variceal bleeding remains the most severe and life-threatening complication of portal hypertension in cirrhotic patients. Several small studies have shown improved outcomes with p-TIPS without worsening of hepatic encephalopathy or other adverse events.

Study design: Multicenter, international, observational study.

Setting: One Canadian and 33 European referral centers.

Synopsis: 2,138 patients were registered for analysis, of which 671 were identified as high risk based on Child-Pugh score (either Child class C of less than 14 or Child class B with active bleeding seen on endoscopy). Multiple exclusion criteria were used including Child-Pugh score of 14 or more, renal failure, occlusive portal vein thrombosis, sepsis, heart failure, or hepatocellular carcinoma outside Milan criteria. Each patient underwent initial management with vasoactive medications, antibiotics, and endoscopy with subsequent intervention (p-TIPS vs. standard care) based on provider decision. p-TIPS was defined as TIPS within 72 hours of initial bleed. 31.4% of the cohort was lost to follow-up at 1 year. p-TIPS improved 1-year mortality significantly (78% vs. 62%; P = .014) and did not confer an increased risk of hepatic encephalopathy or other complication. Additionally, the authors found that the effect was significantly greater in the Child-Pugh Class C group (1-year mortality rate of 78% vs. 53%; P = .002). The authors then compared observed mortality with MELD-predicted mortality and found that with standard care, MELD scores matched with predicted mortality, but with p-TIPS, MELD scores predicted a greater mortality than the observed mortality. The authors calculated that the number needed to treat to save one life for 1 year with p-TIPS is 4.2. The major limitation of this study is the observational design and the inherent risk of selection bias. Additionally, almost one-third of patients were lost to follow-up.

Bottom line: Significant improvements in mortality are observed when high-risk patients undergo p-TIPS procedures as opposed to usual care with medications and endoscopy.

Citation: Hernández Gea V et al. Preemptive TIPS improves outcome in high risk variceal bleeding: An observational study. Hepatology. 2018 Jul 16. doi: 10.1002/hep.30182.

Dr. Imber is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of New Mexico.

Background: Acute variceal bleeding remains the most severe and life-threatening complication of portal hypertension in cirrhotic patients. Several small studies have shown improved outcomes with p-TIPS without worsening of hepatic encephalopathy or other adverse events.

Study design: Multicenter, international, observational study.

Setting: One Canadian and 33 European referral centers.

Synopsis: 2,138 patients were registered for analysis, of which 671 were identified as high risk based on Child-Pugh score (either Child class C of less than 14 or Child class B with active bleeding seen on endoscopy). Multiple exclusion criteria were used including Child-Pugh score of 14 or more, renal failure, occlusive portal vein thrombosis, sepsis, heart failure, or hepatocellular carcinoma outside Milan criteria. Each patient underwent initial management with vasoactive medications, antibiotics, and endoscopy with subsequent intervention (p-TIPS vs. standard care) based on provider decision. p-TIPS was defined as TIPS within 72 hours of initial bleed. 31.4% of the cohort was lost to follow-up at 1 year. p-TIPS improved 1-year mortality significantly (78% vs. 62%; P = .014) and did not confer an increased risk of hepatic encephalopathy or other complication. Additionally, the authors found that the effect was significantly greater in the Child-Pugh Class C group (1-year mortality rate of 78% vs. 53%; P = .002). The authors then compared observed mortality with MELD-predicted mortality and found that with standard care, MELD scores matched with predicted mortality, but with p-TIPS, MELD scores predicted a greater mortality than the observed mortality. The authors calculated that the number needed to treat to save one life for 1 year with p-TIPS is 4.2. The major limitation of this study is the observational design and the inherent risk of selection bias. Additionally, almost one-third of patients were lost to follow-up.

Bottom line: Significant improvements in mortality are observed when high-risk patients undergo p-TIPS procedures as opposed to usual care with medications and endoscopy.

Citation: Hernández Gea V et al. Preemptive TIPS improves outcome in high risk variceal bleeding: An observational study. Hepatology. 2018 Jul 16. doi: 10.1002/hep.30182.

Dr. Imber is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of New Mexico.

Background: Acute variceal bleeding remains the most severe and life-threatening complication of portal hypertension in cirrhotic patients. Several small studies have shown improved outcomes with p-TIPS without worsening of hepatic encephalopathy or other adverse events.

Study design: Multicenter, international, observational study.

Setting: One Canadian and 33 European referral centers.

Synopsis: 2,138 patients were registered for analysis, of which 671 were identified as high risk based on Child-Pugh score (either Child class C of less than 14 or Child class B with active bleeding seen on endoscopy). Multiple exclusion criteria were used including Child-Pugh score of 14 or more, renal failure, occlusive portal vein thrombosis, sepsis, heart failure, or hepatocellular carcinoma outside Milan criteria. Each patient underwent initial management with vasoactive medications, antibiotics, and endoscopy with subsequent intervention (p-TIPS vs. standard care) based on provider decision. p-TIPS was defined as TIPS within 72 hours of initial bleed. 31.4% of the cohort was lost to follow-up at 1 year. p-TIPS improved 1-year mortality significantly (78% vs. 62%; P = .014) and did not confer an increased risk of hepatic encephalopathy or other complication. Additionally, the authors found that the effect was significantly greater in the Child-Pugh Class C group (1-year mortality rate of 78% vs. 53%; P = .002). The authors then compared observed mortality with MELD-predicted mortality and found that with standard care, MELD scores matched with predicted mortality, but with p-TIPS, MELD scores predicted a greater mortality than the observed mortality. The authors calculated that the number needed to treat to save one life for 1 year with p-TIPS is 4.2. The major limitation of this study is the observational design and the inherent risk of selection bias. Additionally, almost one-third of patients were lost to follow-up.

Bottom line: Significant improvements in mortality are observed when high-risk patients undergo p-TIPS procedures as opposed to usual care with medications and endoscopy.

Citation: Hernández Gea V et al. Preemptive TIPS improves outcome in high risk variceal bleeding: An observational study. Hepatology. 2018 Jul 16. doi: 10.1002/hep.30182.

Dr. Imber is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of New Mexico.

Pilot program addresses social determinants of health

WASHINGTON –

The program, called SHAPE (Social Health Alliance to Promote Equity), was designed to screen patients across multiple social categories. In-house patient navigators, some bilingual, were trained on how to work with diverse populations and were able to address unmet patient needs through referrals to individualized resources. Physicians could refer patients to the following local community partners:

- The Child Center of NY.

- The INN – serving hungry & homeless Long Islanders.

- Maurice A. Deane School of Law – Hofstra Law.

- The Gitenstein Institute for Health Law and Policy.

The legal partners provided free assistance to patience with legal needs.

“By implementing a program where you address the nonmedical social needs, you will actually improve the overall health of the patient. You can’t just address the biomedical needs of your patients, you need to understand their home environment, their background, and social situations they’re going through to keep them healthy,” said Jane Lindahl at the annual meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine. Ms. Lindahl is a research assistant at Cohen Children’s Medical Center at Northwell Health in New York.

The SHAPE program was conducted at two internal medicine and pediatric primary care clinics at Northwell Health, a large academic hospital system in New York. It was originally created in the pediatric practice in August 2016 and expanded to the internal medicine practice in June 2018. A medicolegal partnership was created as part of the program in October 2018.

The patient population comprised low-income, racially ethnic, primarily Medicaid and uninsured individuals, including a high number of documented and undocumented immigrants. While 927 patients were screened, 590 screened positive for social determinants of health (SDOH). Of those 590 patients, 190 patients connected with patient navigators for intake and accepted initial assistance and 74 patients were connected to resources.

Screening was based on patients’ completion of a one-page SDOH form in the waiting room of their physician’s office on the same day of their annual visit. There were 15 categories of social needs identified on the screen.

After the screening, the results were discussed with the patients and the necessary referrals were determined. The screening indicated that the largest needs for the patients were health/dental insurance (cited by 296 people), education (cited by 269 people), and health literacy (cited by 225 patients).

Those who had emergent social needs were referred to on-site social workers and providers to address such needs. The emergent social needs included being a victim of domestic violence, being homeless, having an imminent eviction, and having imminent deportation.

Those patients with nonemergent social needs received referral and follow-up processes within 48 hours.

After a referral was made, the patient navigator followed up every 2 weeks with the patient to check on the status of the referral and social needs. After this period, a final phone interview was conducted to get feedback on the patient’s experience and SDOH status.

Ms. Lindahl had no financial conflicts of interest to disclose. The program was funded by Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Grant, Health Leads, Collaborative to Advance Social Health Integration, N.Y. State Delivery System Reform Incentive Program, and United Hospital Foundation.

WASHINGTON –

The program, called SHAPE (Social Health Alliance to Promote Equity), was designed to screen patients across multiple social categories. In-house patient navigators, some bilingual, were trained on how to work with diverse populations and were able to address unmet patient needs through referrals to individualized resources. Physicians could refer patients to the following local community partners:

- The Child Center of NY.

- The INN – serving hungry & homeless Long Islanders.

- Maurice A. Deane School of Law – Hofstra Law.

- The Gitenstein Institute for Health Law and Policy.

The legal partners provided free assistance to patience with legal needs.

“By implementing a program where you address the nonmedical social needs, you will actually improve the overall health of the patient. You can’t just address the biomedical needs of your patients, you need to understand their home environment, their background, and social situations they’re going through to keep them healthy,” said Jane Lindahl at the annual meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine. Ms. Lindahl is a research assistant at Cohen Children’s Medical Center at Northwell Health in New York.

The SHAPE program was conducted at two internal medicine and pediatric primary care clinics at Northwell Health, a large academic hospital system in New York. It was originally created in the pediatric practice in August 2016 and expanded to the internal medicine practice in June 2018. A medicolegal partnership was created as part of the program in October 2018.

The patient population comprised low-income, racially ethnic, primarily Medicaid and uninsured individuals, including a high number of documented and undocumented immigrants. While 927 patients were screened, 590 screened positive for social determinants of health (SDOH). Of those 590 patients, 190 patients connected with patient navigators for intake and accepted initial assistance and 74 patients were connected to resources.

Screening was based on patients’ completion of a one-page SDOH form in the waiting room of their physician’s office on the same day of their annual visit. There were 15 categories of social needs identified on the screen.

After the screening, the results were discussed with the patients and the necessary referrals were determined. The screening indicated that the largest needs for the patients were health/dental insurance (cited by 296 people), education (cited by 269 people), and health literacy (cited by 225 patients).

Those who had emergent social needs were referred to on-site social workers and providers to address such needs. The emergent social needs included being a victim of domestic violence, being homeless, having an imminent eviction, and having imminent deportation.

Those patients with nonemergent social needs received referral and follow-up processes within 48 hours.

After a referral was made, the patient navigator followed up every 2 weeks with the patient to check on the status of the referral and social needs. After this period, a final phone interview was conducted to get feedback on the patient’s experience and SDOH status.

Ms. Lindahl had no financial conflicts of interest to disclose. The program was funded by Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Grant, Health Leads, Collaborative to Advance Social Health Integration, N.Y. State Delivery System Reform Incentive Program, and United Hospital Foundation.

WASHINGTON –

The program, called SHAPE (Social Health Alliance to Promote Equity), was designed to screen patients across multiple social categories. In-house patient navigators, some bilingual, were trained on how to work with diverse populations and were able to address unmet patient needs through referrals to individualized resources. Physicians could refer patients to the following local community partners:

- The Child Center of NY.

- The INN – serving hungry & homeless Long Islanders.

- Maurice A. Deane School of Law – Hofstra Law.

- The Gitenstein Institute for Health Law and Policy.

The legal partners provided free assistance to patience with legal needs.

“By implementing a program where you address the nonmedical social needs, you will actually improve the overall health of the patient. You can’t just address the biomedical needs of your patients, you need to understand their home environment, their background, and social situations they’re going through to keep them healthy,” said Jane Lindahl at the annual meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine. Ms. Lindahl is a research assistant at Cohen Children’s Medical Center at Northwell Health in New York.

The SHAPE program was conducted at two internal medicine and pediatric primary care clinics at Northwell Health, a large academic hospital system in New York. It was originally created in the pediatric practice in August 2016 and expanded to the internal medicine practice in June 2018. A medicolegal partnership was created as part of the program in October 2018.

The patient population comprised low-income, racially ethnic, primarily Medicaid and uninsured individuals, including a high number of documented and undocumented immigrants. While 927 patients were screened, 590 screened positive for social determinants of health (SDOH). Of those 590 patients, 190 patients connected with patient navigators for intake and accepted initial assistance and 74 patients were connected to resources.

Screening was based on patients’ completion of a one-page SDOH form in the waiting room of their physician’s office on the same day of their annual visit. There were 15 categories of social needs identified on the screen.

After the screening, the results were discussed with the patients and the necessary referrals were determined. The screening indicated that the largest needs for the patients were health/dental insurance (cited by 296 people), education (cited by 269 people), and health literacy (cited by 225 patients).

Those who had emergent social needs were referred to on-site social workers and providers to address such needs. The emergent social needs included being a victim of domestic violence, being homeless, having an imminent eviction, and having imminent deportation.

Those patients with nonemergent social needs received referral and follow-up processes within 48 hours.

After a referral was made, the patient navigator followed up every 2 weeks with the patient to check on the status of the referral and social needs. After this period, a final phone interview was conducted to get feedback on the patient’s experience and SDOH status.

Ms. Lindahl had no financial conflicts of interest to disclose. The program was funded by Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Grant, Health Leads, Collaborative to Advance Social Health Integration, N.Y. State Delivery System Reform Incentive Program, and United Hospital Foundation.

REPORTING FROM SGIM 2019

Posthospitalization thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban is unnecessary

Background: Anticoagulation for at-risk medical populations for posthospitalization thromboprophylaxis has been investigated in previous studies demonstrating a benefit in reducing risk of asymptomatic deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) development, but no studies have examined symptomatic DVTs.

Study design: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multinational clinical trial.

Setting: 671 multinational hospitals.

Synopsis: 11,962 patients were identified as at-risk patients based on length of hospitalization (3-10 days), diagnosis, and additional risk factors identified by an IMPROVE risk score of greater than 4 or 2-3 with a D-dimer level more than twice the upper limit of normal. Patients were randomly assigned to receive rivaroxaban or placebo for 45 days. Primary outcome was composite of any symptomatic DVT or death related to VTE. Safety outcomes were principally related to bleeding. Symptomatic VTE or death from VTE occurred in 0.83% in the anticoagulation group and 1.1% in the placebo group (95% confidence interval, 0.52-1.09; P = .14). No significant difference was found in safety outcomes. The major limitation of the study was the low incidence of VTE and the need to include lower-risk patients (IMPROVE score 2/3 with elevated D-dimer), which may have decreased the effect of anticoagulation in the high-risk group (IMPROVE score 4 or greater).

Bottom line: No significant improvement in symptomatic VTE complications was found with posthospitalization thromboprophylaxis using rivaroxaban for an at-risk medical population.

Citation: Spyropoulos AC et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis after hospitalization for medical illness. N Eng J Med. 2018 Sep 20;379:1118-27.

Dr. Imber is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of New Mexico.

Background: Anticoagulation for at-risk medical populations for posthospitalization thromboprophylaxis has been investigated in previous studies demonstrating a benefit in reducing risk of asymptomatic deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) development, but no studies have examined symptomatic DVTs.

Study design: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multinational clinical trial.

Setting: 671 multinational hospitals.

Synopsis: 11,962 patients were identified as at-risk patients based on length of hospitalization (3-10 days), diagnosis, and additional risk factors identified by an IMPROVE risk score of greater than 4 or 2-3 with a D-dimer level more than twice the upper limit of normal. Patients were randomly assigned to receive rivaroxaban or placebo for 45 days. Primary outcome was composite of any symptomatic DVT or death related to VTE. Safety outcomes were principally related to bleeding. Symptomatic VTE or death from VTE occurred in 0.83% in the anticoagulation group and 1.1% in the placebo group (95% confidence interval, 0.52-1.09; P = .14). No significant difference was found in safety outcomes. The major limitation of the study was the low incidence of VTE and the need to include lower-risk patients (IMPROVE score 2/3 with elevated D-dimer), which may have decreased the effect of anticoagulation in the high-risk group (IMPROVE score 4 or greater).

Bottom line: No significant improvement in symptomatic VTE complications was found with posthospitalization thromboprophylaxis using rivaroxaban for an at-risk medical population.

Citation: Spyropoulos AC et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis after hospitalization for medical illness. N Eng J Med. 2018 Sep 20;379:1118-27.

Dr. Imber is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of New Mexico.

Background: Anticoagulation for at-risk medical populations for posthospitalization thromboprophylaxis has been investigated in previous studies demonstrating a benefit in reducing risk of asymptomatic deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) development, but no studies have examined symptomatic DVTs.

Study design: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multinational clinical trial.

Setting: 671 multinational hospitals.

Synopsis: 11,962 patients were identified as at-risk patients based on length of hospitalization (3-10 days), diagnosis, and additional risk factors identified by an IMPROVE risk score of greater than 4 or 2-3 with a D-dimer level more than twice the upper limit of normal. Patients were randomly assigned to receive rivaroxaban or placebo for 45 days. Primary outcome was composite of any symptomatic DVT or death related to VTE. Safety outcomes were principally related to bleeding. Symptomatic VTE or death from VTE occurred in 0.83% in the anticoagulation group and 1.1% in the placebo group (95% confidence interval, 0.52-1.09; P = .14). No significant difference was found in safety outcomes. The major limitation of the study was the low incidence of VTE and the need to include lower-risk patients (IMPROVE score 2/3 with elevated D-dimer), which may have decreased the effect of anticoagulation in the high-risk group (IMPROVE score 4 or greater).

Bottom line: No significant improvement in symptomatic VTE complications was found with posthospitalization thromboprophylaxis using rivaroxaban for an at-risk medical population.

Citation: Spyropoulos AC et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis after hospitalization for medical illness. N Eng J Med. 2018 Sep 20;379:1118-27.

Dr. Imber is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of New Mexico.

HM19: Pediatric sepsis

Improving recognition and treatment

Presenters

Elise van der Jagt, MD, MPH

Workshop title

What you need to know about pediatric sepsis

Session summary

Dr. Elise van der Jagt of the University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center, introduced the topic of pediatric sepsis and its epidemiology with the story of 12-year-old Rory Staunton, who died in 2012 of sepsis. In pediatrics, sepsis is the 10th leading cause of death, with severe sepsis having a mortality rate of 4%-10%. As a response to Rory Staunton’s death from sepsis, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo mandated all hospitals to implement ways to improve recognition and treatment of septic shock, especially in children.

The definition and management of sepsis in pediatrics is complex, and forms a spectrum of disease from sepsis to severe sepsis, and septic shock. Dr. van der Jagt advised not to use the adult sepsis definition in children. Sepsis, stated Dr. van der Jagt, is systemic inflammatory response syndrome in association with suspected or proven infection. Severe sepsis is sepsis with cardiovascular dysfunction, respiratory dysfunction, or dysfunction of two other systems. Septic shock is sepsis with cardiovascular dysfunction that persists despite 40 mL/kg of fluid bolus in 1 hour.

Early recognition and management of sepsis decreases mortality. Early recognition can be improved by initiating a recognition bundle. Multiple trigger tools are available such as pSOFA (Pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment). Any trigger tool, however, must be combined with physician evaluation. This clinician assessment should be initiated within 15 minutes for any patient who screens positive with a trigger tool.

Resuscitation bundles also decrease mortality. A good goal is establishing intravenous or intraosseous access within 5 minutes, fluid administration within 30 minutes, and antibiotics and inotrope administration (if needed) in 60 minutes. Resuscitation bundles could include a sepsis clock, rapid response team, check list, protocol, and order set. Additional studies are needed to determine which of the components of a sepsis bundle is most important. Studies show that mortality increases with delays in initiating fluids and less fluids given. However, giving too much fluid also increases morbidity. It is imperative, stated Dr. van der Jagt, to reassess after fluid boluses. Use of lactate measurement can be problematic in pediatrics, as normal lactate can be seen with florid sepsis.

Stabilization bundles are more common in the ICU setting. They include an arterial line, central venous pressure, cardiopulmonary monitor, urinary catheter, and pulse oximeter. A performance bundle is important to assess adherence to the other bundles. This could include providing debriefing, data review, feedback, and formal quality improvement projects. Assigning a sepsis champion in each area helps to overcome barriers and continue performance bundles.

Key takeaways for HM

- Patients with severe sepsis/septic shock should be rapidly identified with the 2014/2017 American College of Critical Care Medicine consensus criteria.

- Efficient, time-based care should be provided during the first hour after recognizing pediatric severe sepsis/septic shock.

- Overcoming systems barriers to rapid sepsis recognition and treatment requires sepsis champions in each area, continuous data collection and feedback, persistence, and patience.

Dr. Eboh is a pediatric hospitalist at Covenant Children’s Hospital in Lubbock, Texas, and assistant professor of pediatrics at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center. Dr. Wright is a pediatric hospitalist at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center.

Improving recognition and treatment

Improving recognition and treatment

Presenters

Elise van der Jagt, MD, MPH

Workshop title

What you need to know about pediatric sepsis

Session summary

Dr. Elise van der Jagt of the University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center, introduced the topic of pediatric sepsis and its epidemiology with the story of 12-year-old Rory Staunton, who died in 2012 of sepsis. In pediatrics, sepsis is the 10th leading cause of death, with severe sepsis having a mortality rate of 4%-10%. As a response to Rory Staunton’s death from sepsis, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo mandated all hospitals to implement ways to improve recognition and treatment of septic shock, especially in children.

The definition and management of sepsis in pediatrics is complex, and forms a spectrum of disease from sepsis to severe sepsis, and septic shock. Dr. van der Jagt advised not to use the adult sepsis definition in children. Sepsis, stated Dr. van der Jagt, is systemic inflammatory response syndrome in association with suspected or proven infection. Severe sepsis is sepsis with cardiovascular dysfunction, respiratory dysfunction, or dysfunction of two other systems. Septic shock is sepsis with cardiovascular dysfunction that persists despite 40 mL/kg of fluid bolus in 1 hour.

Early recognition and management of sepsis decreases mortality. Early recognition can be improved by initiating a recognition bundle. Multiple trigger tools are available such as pSOFA (Pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment). Any trigger tool, however, must be combined with physician evaluation. This clinician assessment should be initiated within 15 minutes for any patient who screens positive with a trigger tool.

Resuscitation bundles also decrease mortality. A good goal is establishing intravenous or intraosseous access within 5 minutes, fluid administration within 30 minutes, and antibiotics and inotrope administration (if needed) in 60 minutes. Resuscitation bundles could include a sepsis clock, rapid response team, check list, protocol, and order set. Additional studies are needed to determine which of the components of a sepsis bundle is most important. Studies show that mortality increases with delays in initiating fluids and less fluids given. However, giving too much fluid also increases morbidity. It is imperative, stated Dr. van der Jagt, to reassess after fluid boluses. Use of lactate measurement can be problematic in pediatrics, as normal lactate can be seen with florid sepsis.

Stabilization bundles are more common in the ICU setting. They include an arterial line, central venous pressure, cardiopulmonary monitor, urinary catheter, and pulse oximeter. A performance bundle is important to assess adherence to the other bundles. This could include providing debriefing, data review, feedback, and formal quality improvement projects. Assigning a sepsis champion in each area helps to overcome barriers and continue performance bundles.

Key takeaways for HM

- Patients with severe sepsis/septic shock should be rapidly identified with the 2014/2017 American College of Critical Care Medicine consensus criteria.

- Efficient, time-based care should be provided during the first hour after recognizing pediatric severe sepsis/septic shock.

- Overcoming systems barriers to rapid sepsis recognition and treatment requires sepsis champions in each area, continuous data collection and feedback, persistence, and patience.

Dr. Eboh is a pediatric hospitalist at Covenant Children’s Hospital in Lubbock, Texas, and assistant professor of pediatrics at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center. Dr. Wright is a pediatric hospitalist at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center.

Presenters

Elise van der Jagt, MD, MPH

Workshop title

What you need to know about pediatric sepsis

Session summary

Dr. Elise van der Jagt of the University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center, introduced the topic of pediatric sepsis and its epidemiology with the story of 12-year-old Rory Staunton, who died in 2012 of sepsis. In pediatrics, sepsis is the 10th leading cause of death, with severe sepsis having a mortality rate of 4%-10%. As a response to Rory Staunton’s death from sepsis, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo mandated all hospitals to implement ways to improve recognition and treatment of septic shock, especially in children.

The definition and management of sepsis in pediatrics is complex, and forms a spectrum of disease from sepsis to severe sepsis, and septic shock. Dr. van der Jagt advised not to use the adult sepsis definition in children. Sepsis, stated Dr. van der Jagt, is systemic inflammatory response syndrome in association with suspected or proven infection. Severe sepsis is sepsis with cardiovascular dysfunction, respiratory dysfunction, or dysfunction of two other systems. Septic shock is sepsis with cardiovascular dysfunction that persists despite 40 mL/kg of fluid bolus in 1 hour.

Early recognition and management of sepsis decreases mortality. Early recognition can be improved by initiating a recognition bundle. Multiple trigger tools are available such as pSOFA (Pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment). Any trigger tool, however, must be combined with physician evaluation. This clinician assessment should be initiated within 15 minutes for any patient who screens positive with a trigger tool.

Resuscitation bundles also decrease mortality. A good goal is establishing intravenous or intraosseous access within 5 minutes, fluid administration within 30 minutes, and antibiotics and inotrope administration (if needed) in 60 minutes. Resuscitation bundles could include a sepsis clock, rapid response team, check list, protocol, and order set. Additional studies are needed to determine which of the components of a sepsis bundle is most important. Studies show that mortality increases with delays in initiating fluids and less fluids given. However, giving too much fluid also increases morbidity. It is imperative, stated Dr. van der Jagt, to reassess after fluid boluses. Use of lactate measurement can be problematic in pediatrics, as normal lactate can be seen with florid sepsis.

Stabilization bundles are more common in the ICU setting. They include an arterial line, central venous pressure, cardiopulmonary monitor, urinary catheter, and pulse oximeter. A performance bundle is important to assess adherence to the other bundles. This could include providing debriefing, data review, feedback, and formal quality improvement projects. Assigning a sepsis champion in each area helps to overcome barriers and continue performance bundles.

Key takeaways for HM

- Patients with severe sepsis/septic shock should be rapidly identified with the 2014/2017 American College of Critical Care Medicine consensus criteria.

- Efficient, time-based care should be provided during the first hour after recognizing pediatric severe sepsis/septic shock.

- Overcoming systems barriers to rapid sepsis recognition and treatment requires sepsis champions in each area, continuous data collection and feedback, persistence, and patience.

Dr. Eboh is a pediatric hospitalist at Covenant Children’s Hospital in Lubbock, Texas, and assistant professor of pediatrics at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center. Dr. Wright is a pediatric hospitalist at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center.

Short Takes

Evidence is uncertain for benefit of short-stay unit hospitalization

A Cochrane review of 14 randomized trials evaluating short-stay unit hospitalization for internal medicine conditions was unable to ascertain any definite benefit or harm, compared with usual care, with concerns for heterogeneity, bias, and random error in the studies. The authors recommended conducting more trials with low risk of bias and low risk of random errors.

Citation: Strøm C et al. Hospitalisation in short-stay units for adults with internal medicine diseases and conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;8. CD012370. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012370.pub2.

Hospice use among Medicare patients with heart failure

Of the 4% percent of Medicare patients discharged to hospice from a hospitalization for heart failure, 25% died within 72 hours of discharge, leading the authors to conclude that hospice is underutilized and initiated too late in the setting of heart failure.

Citation: Warraich HJ et al. Trends in hospice discharge and relative outcomes among Medicare patients in the Get With The Guidelines–Heart Failure Registry. JAMA Cardiol. 2018 Oct 1;3(10):917-26.

Culprit lesion PCI has similar 1-year mortality to immediate multivessel PCI

This is the follow-up study to CULPRIT-SHOCK trial , which examined percutaneous coronary intervention in culprit lesion only vs. multivessel PCI in the setting of cardiogenic shock. The initial trial showed improved 30-day mortality outcomes with culprit lesion PCI only and the follow-up demonstrated no significant difference in 1-year mortality between the two groups.

Citation: Thiele H et al. One-year outcomes after PCI strategies in cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 1;379(18):1699-710 .

Evidence is uncertain for benefit of short-stay unit hospitalization

A Cochrane review of 14 randomized trials evaluating short-stay unit hospitalization for internal medicine conditions was unable to ascertain any definite benefit or harm, compared with usual care, with concerns for heterogeneity, bias, and random error in the studies. The authors recommended conducting more trials with low risk of bias and low risk of random errors.

Citation: Strøm C et al. Hospitalisation in short-stay units for adults with internal medicine diseases and conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;8. CD012370. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012370.pub2.

Hospice use among Medicare patients with heart failure

Of the 4% percent of Medicare patients discharged to hospice from a hospitalization for heart failure, 25% died within 72 hours of discharge, leading the authors to conclude that hospice is underutilized and initiated too late in the setting of heart failure.

Citation: Warraich HJ et al. Trends in hospice discharge and relative outcomes among Medicare patients in the Get With The Guidelines–Heart Failure Registry. JAMA Cardiol. 2018 Oct 1;3(10):917-26.

Culprit lesion PCI has similar 1-year mortality to immediate multivessel PCI

This is the follow-up study to CULPRIT-SHOCK trial , which examined percutaneous coronary intervention in culprit lesion only vs. multivessel PCI in the setting of cardiogenic shock. The initial trial showed improved 30-day mortality outcomes with culprit lesion PCI only and the follow-up demonstrated no significant difference in 1-year mortality between the two groups.

Citation: Thiele H et al. One-year outcomes after PCI strategies in cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 1;379(18):1699-710 .

Evidence is uncertain for benefit of short-stay unit hospitalization

A Cochrane review of 14 randomized trials evaluating short-stay unit hospitalization for internal medicine conditions was unable to ascertain any definite benefit or harm, compared with usual care, with concerns for heterogeneity, bias, and random error in the studies. The authors recommended conducting more trials with low risk of bias and low risk of random errors.

Citation: Strøm C et al. Hospitalisation in short-stay units for adults with internal medicine diseases and conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;8. CD012370. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012370.pub2.

Hospice use among Medicare patients with heart failure

Of the 4% percent of Medicare patients discharged to hospice from a hospitalization for heart failure, 25% died within 72 hours of discharge, leading the authors to conclude that hospice is underutilized and initiated too late in the setting of heart failure.

Citation: Warraich HJ et al. Trends in hospice discharge and relative outcomes among Medicare patients in the Get With The Guidelines–Heart Failure Registry. JAMA Cardiol. 2018 Oct 1;3(10):917-26.

Culprit lesion PCI has similar 1-year mortality to immediate multivessel PCI

This is the follow-up study to CULPRIT-SHOCK trial , which examined percutaneous coronary intervention in culprit lesion only vs. multivessel PCI in the setting of cardiogenic shock. The initial trial showed improved 30-day mortality outcomes with culprit lesion PCI only and the follow-up demonstrated no significant difference in 1-year mortality between the two groups.

Citation: Thiele H et al. One-year outcomes after PCI strategies in cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 1;379(18):1699-710 .

Early dexmedetomidine did not reduce 90-day mortality in ICU patients on mechanical ventilation

Dexmedetomidine fell short for reducing 90-day mortality as the primary sedative for patients on mechanical ventilation, according to results of the randomized, controlled, open-label SPICE III trial, which was presented at the annual meeting of the American Thoracic Society and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Among patients undergoing mechanical ventilation in the ICU, those who received early dexmedetomidine for sedation had a rate of death at 90 days similar to that in the usual-care group and required supplemental sedatives to achieve the prescribed level of sedation,” Yahya Shehabi, PhD, of Monash University in Clayton, Australia, and colleagues wrote.

The study was conducted in 74 ICUs in eight countries. Researchers randomly assigned 4,000 patients who were critically ill, had received ventilation for less than 12 hours, and were likely to require mechanical ventilation for at least the next day to either dexmedetomidine or usual care (propofol, midazolam, or another sedative). The sedation goal was a Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale (RASS) score of –2 (lightly sedated) to +1 (restless), and was assessed every 4 hours. Intravenous dexmedetomidine was administered at 1 mcg/kg of body weight per hour without a loading dose and adjusted to a maximum dose of 1.5 mcg/kg per hour to achieve a RASS score in the target range. Use was continued as clinically required for up to 28 days.

The modified intention-to-treat analysis included 3,904 patients. The 90-day mortality rate was 29.1% (556 of 1,948 patients) for patients who received dexmedetomidine and 29.1% (569 of 1,956 patients) for those who received usual care. There was no significant difference for patients with suspected or proven sepsis at randomization and those without sepsis. Mortality did not vary based on country, cause of death, or discharge destination.

Dr. Shehabi and colleagues noted that, for 2 days after randomization, patients who received dexmedetomidine were also given propofol (64% of patients), midazolam (3%), or both (7%) as supplemental sedation. In the control group, 60% of the patients received propofol, 12% received midazolam, and 20% received both. About 80% of patients in both groups received fentanyl. The use of multiple agents may reflect sedation requirements during the acute phase of critical illness.

With regard to adverse events, the patients receiving dexmedetomidine more commonly experienced bradycardia and hypotension than the usual-care group.

SPICE III was funded in part by a grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the National Heart Institute of Malaysia. Dr. Shehabi reports grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, nonfinancial and other support from Pfizer, and nonfinancial and other support from Orion Pharma.

SOURCE: Shehabi Y et al. N Eng J Med. 2019 May 19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1904710.

Dexmedetomidine fell short for reducing 90-day mortality as the primary sedative for patients on mechanical ventilation, according to results of the randomized, controlled, open-label SPICE III trial, which was presented at the annual meeting of the American Thoracic Society and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Among patients undergoing mechanical ventilation in the ICU, those who received early dexmedetomidine for sedation had a rate of death at 90 days similar to that in the usual-care group and required supplemental sedatives to achieve the prescribed level of sedation,” Yahya Shehabi, PhD, of Monash University in Clayton, Australia, and colleagues wrote.

The study was conducted in 74 ICUs in eight countries. Researchers randomly assigned 4,000 patients who were critically ill, had received ventilation for less than 12 hours, and were likely to require mechanical ventilation for at least the next day to either dexmedetomidine or usual care (propofol, midazolam, or another sedative). The sedation goal was a Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale (RASS) score of –2 (lightly sedated) to +1 (restless), and was assessed every 4 hours. Intravenous dexmedetomidine was administered at 1 mcg/kg of body weight per hour without a loading dose and adjusted to a maximum dose of 1.5 mcg/kg per hour to achieve a RASS score in the target range. Use was continued as clinically required for up to 28 days.

The modified intention-to-treat analysis included 3,904 patients. The 90-day mortality rate was 29.1% (556 of 1,948 patients) for patients who received dexmedetomidine and 29.1% (569 of 1,956 patients) for those who received usual care. There was no significant difference for patients with suspected or proven sepsis at randomization and those without sepsis. Mortality did not vary based on country, cause of death, or discharge destination.

Dr. Shehabi and colleagues noted that, for 2 days after randomization, patients who received dexmedetomidine were also given propofol (64% of patients), midazolam (3%), or both (7%) as supplemental sedation. In the control group, 60% of the patients received propofol, 12% received midazolam, and 20% received both. About 80% of patients in both groups received fentanyl. The use of multiple agents may reflect sedation requirements during the acute phase of critical illness.

With regard to adverse events, the patients receiving dexmedetomidine more commonly experienced bradycardia and hypotension than the usual-care group.

SPICE III was funded in part by a grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the National Heart Institute of Malaysia. Dr. Shehabi reports grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, nonfinancial and other support from Pfizer, and nonfinancial and other support from Orion Pharma.

SOURCE: Shehabi Y et al. N Eng J Med. 2019 May 19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1904710.

Dexmedetomidine fell short for reducing 90-day mortality as the primary sedative for patients on mechanical ventilation, according to results of the randomized, controlled, open-label SPICE III trial, which was presented at the annual meeting of the American Thoracic Society and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Among patients undergoing mechanical ventilation in the ICU, those who received early dexmedetomidine for sedation had a rate of death at 90 days similar to that in the usual-care group and required supplemental sedatives to achieve the prescribed level of sedation,” Yahya Shehabi, PhD, of Monash University in Clayton, Australia, and colleagues wrote.

The study was conducted in 74 ICUs in eight countries. Researchers randomly assigned 4,000 patients who were critically ill, had received ventilation for less than 12 hours, and were likely to require mechanical ventilation for at least the next day to either dexmedetomidine or usual care (propofol, midazolam, or another sedative). The sedation goal was a Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale (RASS) score of –2 (lightly sedated) to +1 (restless), and was assessed every 4 hours. Intravenous dexmedetomidine was administered at 1 mcg/kg of body weight per hour without a loading dose and adjusted to a maximum dose of 1.5 mcg/kg per hour to achieve a RASS score in the target range. Use was continued as clinically required for up to 28 days.

The modified intention-to-treat analysis included 3,904 patients. The 90-day mortality rate was 29.1% (556 of 1,948 patients) for patients who received dexmedetomidine and 29.1% (569 of 1,956 patients) for those who received usual care. There was no significant difference for patients with suspected or proven sepsis at randomization and those without sepsis. Mortality did not vary based on country, cause of death, or discharge destination.

Dr. Shehabi and colleagues noted that, for 2 days after randomization, patients who received dexmedetomidine were also given propofol (64% of patients), midazolam (3%), or both (7%) as supplemental sedation. In the control group, 60% of the patients received propofol, 12% received midazolam, and 20% received both. About 80% of patients in both groups received fentanyl. The use of multiple agents may reflect sedation requirements during the acute phase of critical illness.

With regard to adverse events, the patients receiving dexmedetomidine more commonly experienced bradycardia and hypotension than the usual-care group.

SPICE III was funded in part by a grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the National Heart Institute of Malaysia. Dr. Shehabi reports grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, nonfinancial and other support from Pfizer, and nonfinancial and other support from Orion Pharma.

SOURCE: Shehabi Y et al. N Eng J Med. 2019 May 19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1904710.

FROM ATS 2019

Key clinical point: Patients receiving dexmedetomidine for sedation had a comparable 90-day mortality rate with patients who received usual care.

Major finding: The mortality rate at 90 days was 29.1% (556 of 1,948 patients) for patients who received dexmedetomidine and 29.1% (569 of 1,956 patients) for those who received usual care.

Study details: The study was conducted in 74 ICUs in 8 countries. Researchers randomly assigned 4,000 patients who were critically ill, had received ventilation for less than 12 hours, and were likely to require mechanical ventilation for at least the next day to either dexmedetomidine or usual care (propofol, midazolam, or another sedative).

Disclosures: The study was funded in part by a grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the National Heart Institute of Malaysia. Dr. Shehabi reports grants from The National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, nonfinancial and other support from Pfizer, and nonfinancial and other support from Orion Pharma.Source: Shehabi Y et al. N Eng J Med. 2019 May 19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1904710.

AFib on the rise in end-stage COPD patients hospitalized for exacerbations

Atrial fibrillation is being seen with increasing frequency in patients admitted to U.S. hospitals for exacerbations of end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, based on a retrospective analysis of data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample.

The prevalence of atrial fibrillation (AFib) among patients with end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) on home oxygen who were admitted with COPD exacerbations increased from 12.9% in 2003 to 21.3% in 2014, according to Xiaochun Xiao of the department of health statistics at Second Military Medical University in Shanghai and colleagues.

Additionally, “we found that comorbid [AFib] was associated with an increased risk of the need for mechanical ventilation, especially invasive mechanical ventilation. Moreover, comorbid [AFib] was associated with adverse clinical outcomes, including increased in-hospital death, acute respiratory failure, acute kidney injury, sepsis, and stroke,” the researchers wrote in the study published in the journal CHEST.

Patients included in the study were aged at least 18 years, were diagnosed with end-stage COPD and on home oxygen, and were hospitalized because of a COPD-related exacerbation. Based on 1,345,270 weighted hospital admissions of adults with end-stage COPD on home oxygen who met the inclusion criteria for the study, 18.2% (244,488 admissions) of patients had AFib, and the prevalence of AFib in COPD patients increased over time from 2003 (12.9%) to 2014 (21.3%; P less than .0001).

Patients with AFib, compared with patients without AFib, were older (75.5 years vs. 69.6 years; P less than .0001) and more likely to be male (50.7% vs. 59.1%; P less than .0001) and white (80.9% vs. 74.4%; P less than .0001). Patients with AFib also had higher stroke risk reflected in higher CHA2DS2-VASc scores (3.26 vs. 2.45; P less than .0001), and higher likelihood of in-hospital mortality and readmission reflected in Elixhauser scores greater than or equal to 4 (51.2% vs. 35.6%).

In addition, the prevalence of AFib increased with increasing income. Larger hospitals in terms of bed size, urban environment, and Medicare insurance status also were associated with a higher AFib prevalence.

AFib was associated with an increased cost of $1,415 and an increased length of stay of 0.6 days after adjustment for potential confounders. AFib also predicted risk for several adverse events, including stroke (odds ratio, 1.80; in-hospital death, [OR, 1.54]), invasive mechanical ventilation (OR, 1.37), sepsis (OR, 1.23), noninvasive mechanical ventilation (OR, 1.14), acute kidney injury (OR, 1.09), and acute respiratory failure (OR, 1.09).

The researchers noted the database could have potentially overinflated AFib prevalence, as they could not differentiate index admissions and readmissions. The database also does not contain information about secondary diagnoses codes present on admission, which could make it difficult to identify adverse events that occurred during hospitalization.

“Our findings should prompt further efforts to identify the reasons for increased [AFib] prevalence and provide better management strategies for end-stage COPD patients comorbid with [AFib],” the researchers concluded.

This study was funded by a grant from the Fourth Round of the Shanghai 3-year Action Plan on Public Health Discipline and Talent Program. The authors reported no relevant conflict of interest.

SOURCE: Xiao X et al. CHEST. 2019 Jan 23. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.12.021.

Atrial fibrillation is being seen with increasing frequency in patients admitted to U.S. hospitals for exacerbations of end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, based on a retrospective analysis of data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample.

The prevalence of atrial fibrillation (AFib) among patients with end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) on home oxygen who were admitted with COPD exacerbations increased from 12.9% in 2003 to 21.3% in 2014, according to Xiaochun Xiao of the department of health statistics at Second Military Medical University in Shanghai and colleagues.

Additionally, “we found that comorbid [AFib] was associated with an increased risk of the need for mechanical ventilation, especially invasive mechanical ventilation. Moreover, comorbid [AFib] was associated with adverse clinical outcomes, including increased in-hospital death, acute respiratory failure, acute kidney injury, sepsis, and stroke,” the researchers wrote in the study published in the journal CHEST.

Patients included in the study were aged at least 18 years, were diagnosed with end-stage COPD and on home oxygen, and were hospitalized because of a COPD-related exacerbation. Based on 1,345,270 weighted hospital admissions of adults with end-stage COPD on home oxygen who met the inclusion criteria for the study, 18.2% (244,488 admissions) of patients had AFib, and the prevalence of AFib in COPD patients increased over time from 2003 (12.9%) to 2014 (21.3%; P less than .0001).

Patients with AFib, compared with patients without AFib, were older (75.5 years vs. 69.6 years; P less than .0001) and more likely to be male (50.7% vs. 59.1%; P less than .0001) and white (80.9% vs. 74.4%; P less than .0001). Patients with AFib also had higher stroke risk reflected in higher CHA2DS2-VASc scores (3.26 vs. 2.45; P less than .0001), and higher likelihood of in-hospital mortality and readmission reflected in Elixhauser scores greater than or equal to 4 (51.2% vs. 35.6%).

In addition, the prevalence of AFib increased with increasing income. Larger hospitals in terms of bed size, urban environment, and Medicare insurance status also were associated with a higher AFib prevalence.

AFib was associated with an increased cost of $1,415 and an increased length of stay of 0.6 days after adjustment for potential confounders. AFib also predicted risk for several adverse events, including stroke (odds ratio, 1.80; in-hospital death, [OR, 1.54]), invasive mechanical ventilation (OR, 1.37), sepsis (OR, 1.23), noninvasive mechanical ventilation (OR, 1.14), acute kidney injury (OR, 1.09), and acute respiratory failure (OR, 1.09).

The researchers noted the database could have potentially overinflated AFib prevalence, as they could not differentiate index admissions and readmissions. The database also does not contain information about secondary diagnoses codes present on admission, which could make it difficult to identify adverse events that occurred during hospitalization.

“Our findings should prompt further efforts to identify the reasons for increased [AFib] prevalence and provide better management strategies for end-stage COPD patients comorbid with [AFib],” the researchers concluded.

This study was funded by a grant from the Fourth Round of the Shanghai 3-year Action Plan on Public Health Discipline and Talent Program. The authors reported no relevant conflict of interest.

SOURCE: Xiao X et al. CHEST. 2019 Jan 23. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.12.021.

Atrial fibrillation is being seen with increasing frequency in patients admitted to U.S. hospitals for exacerbations of end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, based on a retrospective analysis of data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample.

The prevalence of atrial fibrillation (AFib) among patients with end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) on home oxygen who were admitted with COPD exacerbations increased from 12.9% in 2003 to 21.3% in 2014, according to Xiaochun Xiao of the department of health statistics at Second Military Medical University in Shanghai and colleagues.

Additionally, “we found that comorbid [AFib] was associated with an increased risk of the need for mechanical ventilation, especially invasive mechanical ventilation. Moreover, comorbid [AFib] was associated with adverse clinical outcomes, including increased in-hospital death, acute respiratory failure, acute kidney injury, sepsis, and stroke,” the researchers wrote in the study published in the journal CHEST.

Patients included in the study were aged at least 18 years, were diagnosed with end-stage COPD and on home oxygen, and were hospitalized because of a COPD-related exacerbation. Based on 1,345,270 weighted hospital admissions of adults with end-stage COPD on home oxygen who met the inclusion criteria for the study, 18.2% (244,488 admissions) of patients had AFib, and the prevalence of AFib in COPD patients increased over time from 2003 (12.9%) to 2014 (21.3%; P less than .0001).

Patients with AFib, compared with patients without AFib, were older (75.5 years vs. 69.6 years; P less than .0001) and more likely to be male (50.7% vs. 59.1%; P less than .0001) and white (80.9% vs. 74.4%; P less than .0001). Patients with AFib also had higher stroke risk reflected in higher CHA2DS2-VASc scores (3.26 vs. 2.45; P less than .0001), and higher likelihood of in-hospital mortality and readmission reflected in Elixhauser scores greater than or equal to 4 (51.2% vs. 35.6%).

In addition, the prevalence of AFib increased with increasing income. Larger hospitals in terms of bed size, urban environment, and Medicare insurance status also were associated with a higher AFib prevalence.

AFib was associated with an increased cost of $1,415 and an increased length of stay of 0.6 days after adjustment for potential confounders. AFib also predicted risk for several adverse events, including stroke (odds ratio, 1.80; in-hospital death, [OR, 1.54]), invasive mechanical ventilation (OR, 1.37), sepsis (OR, 1.23), noninvasive mechanical ventilation (OR, 1.14), acute kidney injury (OR, 1.09), and acute respiratory failure (OR, 1.09).

The researchers noted the database could have potentially overinflated AFib prevalence, as they could not differentiate index admissions and readmissions. The database also does not contain information about secondary diagnoses codes present on admission, which could make it difficult to identify adverse events that occurred during hospitalization.

“Our findings should prompt further efforts to identify the reasons for increased [AFib] prevalence and provide better management strategies for end-stage COPD patients comorbid with [AFib],” the researchers concluded.

This study was funded by a grant from the Fourth Round of the Shanghai 3-year Action Plan on Public Health Discipline and Talent Program. The authors reported no relevant conflict of interest.

SOURCE: Xiao X et al. CHEST. 2019 Jan 23. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.12.021.

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point: Comorbid atrial fibrillation was associated with an increased risk of the need for mechanical ventilation, especially invasive mechanical ventilation, and of adverse outcomes including in-hospital death, acute respiratory failure, acute kidney injury, sepsis, and stroke.

Major finding: The prevalence of atrial fibrillation with end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease increased over time from 2003 (12.9%) to 2014 (21.3%). Study details: A retrospective analysis based on 1,345,270 weighted hospital admissions of adults with end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on home oxygen from the Nationwide Impatient Sample during 2003-2014.

Disclosures: The study was funded by a grant from the Fourth Round of the Shanghai 3-Year Action Plan on Public Health Discipline and Talent Program. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Xiao X et al. CHEST. 2019 Jan 23. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.12.021.

Culture: An unseen force in the hospital workplace

Parallels from the airline industry

“Workplace culture” has a profound influence on the success or failure of a team in the modern-day work environment, where teamwork and interpersonal interactions have paramount importance. Crew resource management (CRM), a technique developed originally by the airline industry, has been used as a tool to improve safety and quality in ICUs, trauma rooms, and operating rooms.1,2 This article discusses the use of CRM in hospital medicine as a tool for training and maintaining a favorable workplace culture.

Origin and evolution of CRM

United Airlines instituted the airline industry’s first crew resource management for pilots in 1981, following the 1978 crash of United Flight 173 in Portland, Ore. CRM was created based on recommendations from the National Transportation Safety Board and from a NASA workshop held subsequently.3 CRM has since evolved through five generations, and is a required annual training for most major commercial airline companies around the world. It also has been adapted for personnel training by several modern international industries.4

From the airline industry to the hospital

The health care industry is similar to the airline industry in that there is absolutely no margin of error, and that workplace culture plays a very important role. The culture being referred to here is the sum total of values, beliefs, work ethics, work strategies, strengths, and weaknesses of a group of people, and how they interact as a group. In other words, it is the dynamics of a group.

According to Donelson R. Forsyth, a social and personality psychologist at the University of Richmond (Virginia), the two key determinants of successful teamwork are a “shared mental representation of the task,” which refers to an in-depth understanding of the team and the tasks they are attempting; and “group unity/cohesion,” which means that, generally, members of cohesive groups like each other and the group, and they also are united in their pursuit of collective, group-level goals.5

Understanding the culture of a hospitalist team

Analyzing group dynamics and actively managing them toward both the institutional and global goals of health care is critical for the success of an organization. This is the core of successfully managing any team in any industry.

Additionally, the rapidly changing health care climate and insurance payment systems requires hospital medicine groups to rapidly adapt to the constantly changing health care business environment. As a result, there are a couple of ways to evaluate the effectiveness of the team:

- Measure tangible outcomes. The outcomes have to be well defined, important and measurable. These could be cost of care, quality of care, engagement of the team etc. These tangible measures’ outcome over a period of time can be used as a measure of how effective the team is.

- Simply ask your team! It is very important to know what core values the team holds dear. The best way to get that information from the team is to find out the de facto leaders of the team. They should be involved in the decision-making process, thus making them valuable to the management as well as the team.

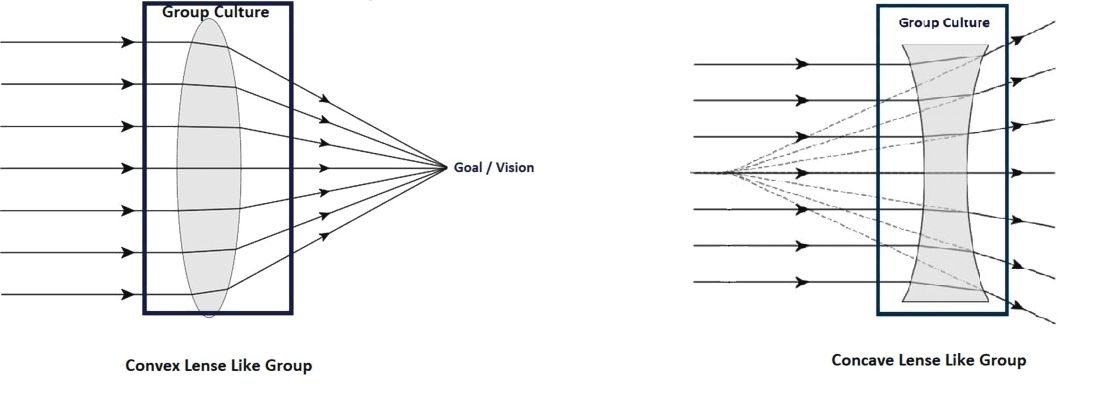

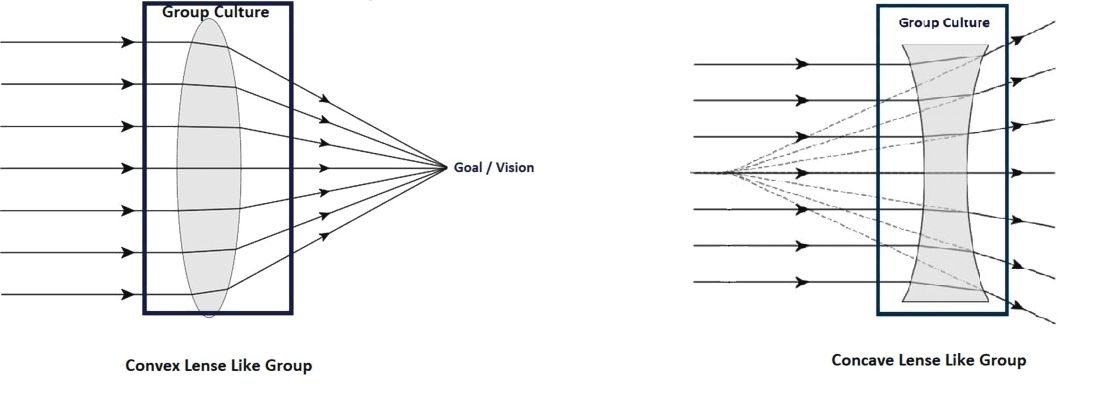

Culture shapes outcomes

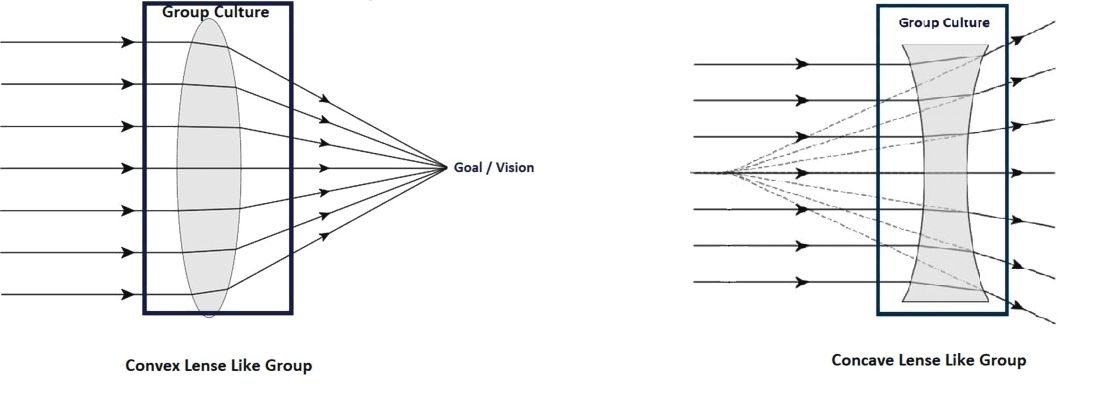

We have used the analogy of a convex and concave lens to help understand this better. A well-developed and well-coordinated team is like convex lens. A lens’ ability to converge or diverge light rays depends on certain characteristics like the curvature of surfaces and refractory index. Likewise, the culture of a group determines its ability to transform all the demands of the collective workload toward a unified goal/outcome. If it is favorable, the group will work as one and success will happen automatically.

Unfortunately, the opposite of this, (the concave lens effect), is more commonplace, where the dynamics of a team prevent the goals being achieved, as there is discordance, poor coordination of ideas and values, and team members not liking each other.

Most teams would fall somewhere within this spectrum, spanning the most favorable convex lens–like group to the least favorable concave lens–like group.

Change team dynamics using CRM principles

The concept of using CRM principles in health care is not entirely new. Such agencies as the Joint Commission and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality recommend using principles of CRM to improve communications, and as an error-prevention tool in health care.6

This approach can be broken down into four important steps:

1. Recruit right. It is important to make sure that the new recruit is the right fit for the team and that the de facto leaders and a few other team members are involved in interviewing the candidates. Their assessment should be given due consideration in making the decision to give the new recruit the job.

Every program looks for aspects like clinical competence, interpersonal communication, teamwork, etc., in a candidate, but it is even more important to make sure the candidate has the tenets that would make him/her a part of that particular team.

2. Train well. The newly recruited providers should be given focused training and the seasoned providers should be given refresher training at regular intervals. Care should be taken in designing the training programs in such a way that the providers are trained in skills that they don’t always think about, things that aren’t readily obvious, and in skills that they never get trained in during medical school and residency.

Specifically, they should be trained in:

- Values. These should include the values of both the organization and the team.

- Safety. This should include all the safety protocols that are in place in the organization - where to get help, how to report unsafe events etc.

- Communication.

Within the group: Have a mentor for the new provider, and also develop a culture where he/she feels comfortable to reach out to anyone in the team for help.

With patients and families: This training should ideally be done in a simulated environment if possible.

With other groups in the hospital: Consultants, nurses, other ancillary staff. Give them an idea about the prevailing culture in the organization with regard to these groups, so that they know what to expect when dealing with them.

- Managing perceptions. How the providers are viewed in the hospital, and how to improve it or maintain it.

- Nurturing the good. Use positive reinforcements to solidify the positive aspects of group dynamics these individuals might possess.

- Weeding out the bad. Use training and feedback to alter the negative group dynamic aspects.

3. Intervene. This is necessary either to maintain the positive aspects of a team that is already high-functioning, or to transform a poorly functioning team into a well-coordinated team. This is where the principles of CRM are going to be most useful.

There are five generations of CRM, each with a different focus.6 Only the aspects relevant to hospital medicine training are mentioned here.

- Communication. Address the gaps in communication. It is important to include people who are trusted by the team in designing and executing these sessions.

- Leadership. The goal should be to encourage the team to take ownership of the program. This will make a tremendous change in the ability of a team to deliver and rise up to challenges. The organizational leadership has to be willing to elevate the leaders of the group to positions where they can meaningfully take part in managing the team and making decisions that are critical to the team.

- Burnout management. Providers getting disillusioned: having no work-life balance; not getting enough respect from management, as well as other groups of doctors/nurses/etc. in the hospital; they are subject to bad scheduling and poor pay – all of which can all lead to career-ending burnout. It is important to recognize this and mitigate the factors that cause burnout.

- Organizational culture. If the team feels valued and supported, they will, in turn, work hard toward success. Creative leadership and a willingness to accommodate what matters the most to the team is essential for achieving this.

- Simulated training. These can be done in simulation labs, or in-group sessions with the team, re-creating difficult scenarios or problems in which the whole team can come together and solve them.

- Error containment and management. The team needs to identify possible sources of error and contain them before errors happen. The group should get together if a serious event happens and brainstorm why it happened and take measures to prevent it.