User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Beware of polypharmacy in patients taking warfarin

SAN DIEGO – The incidence of polypharmacy among patients on warfarin therapy appears to peak at age 75, with close to 10 concurrent active prescriptions on average, results from a single-center study showed.

“Beware of polypharmacy with these patients,” Alan Jacobson, MD, said in an interview at the biennial summit of the Thrombosis & Hemostasis Societies of North America. “Anticoagulation tends to be a high-risk area. If you don’t treat, people have strokes. If you treat, they can have bleeds. Warfarin is the number one drug that gets older patients into the ER and admitted. We know that warfarin has a lot of drug-drug interactions.”

For example, in the ARISTOTLE trial, patients used a median of six drugs, and 26% of patients used nine or more drugs (BMJ. 2016 Jun 15;353:i2868.

In an effort to determine the average and maximum number of concurrent prescription drugs for age-dependent brackets of patients on warfarin, Dr. Jacobson and his associates reviewed the electronic pharmacy records of 1,122 warfarin patients at the VA Loma Linda Healthcare System. They excluded medications that could be obtained over the counter and calculated the average number of concurrent drugs for each of 10 age brackets: under age 50, over age 90, and eight brackets between those limits.

The researchers reported that 9,885 prescriptions were tabulated for the study population, which translated into a per patient average of 8.8 concurrent active prescription drugs, independent of age. They observed an age-dependent increase in the number of concurrent drugs that peaked at 9.9 among patients aged 70-74 years, and tapered off in those older than age 75. One patient in the 70- to 74-year-old age group was on 28 active prescriptions.

“If you’re on 28 pills, your chance of a bleeding complication is high,” Dr. Jacobson said. “We try to be rigorous with all of our patients on education. With these patients, slow the conversation down more. Have a family member come in with them and go into more detail.”

He added that the maximum number of concurrent prescriptions for any single patient in each age bracket tended to be two to three times higher than that of the average patient.

Dr. Jacobson acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its single-center design and relatively small sample size. There was also no comparison available as to the number of concurrent prescriptions for patients not receiving warfarin. He reported having no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Jacobson M et al. THSNA 2018. Poster 2.

SAN DIEGO – The incidence of polypharmacy among patients on warfarin therapy appears to peak at age 75, with close to 10 concurrent active prescriptions on average, results from a single-center study showed.

“Beware of polypharmacy with these patients,” Alan Jacobson, MD, said in an interview at the biennial summit of the Thrombosis & Hemostasis Societies of North America. “Anticoagulation tends to be a high-risk area. If you don’t treat, people have strokes. If you treat, they can have bleeds. Warfarin is the number one drug that gets older patients into the ER and admitted. We know that warfarin has a lot of drug-drug interactions.”

For example, in the ARISTOTLE trial, patients used a median of six drugs, and 26% of patients used nine or more drugs (BMJ. 2016 Jun 15;353:i2868.

In an effort to determine the average and maximum number of concurrent prescription drugs for age-dependent brackets of patients on warfarin, Dr. Jacobson and his associates reviewed the electronic pharmacy records of 1,122 warfarin patients at the VA Loma Linda Healthcare System. They excluded medications that could be obtained over the counter and calculated the average number of concurrent drugs for each of 10 age brackets: under age 50, over age 90, and eight brackets between those limits.

The researchers reported that 9,885 prescriptions were tabulated for the study population, which translated into a per patient average of 8.8 concurrent active prescription drugs, independent of age. They observed an age-dependent increase in the number of concurrent drugs that peaked at 9.9 among patients aged 70-74 years, and tapered off in those older than age 75. One patient in the 70- to 74-year-old age group was on 28 active prescriptions.

“If you’re on 28 pills, your chance of a bleeding complication is high,” Dr. Jacobson said. “We try to be rigorous with all of our patients on education. With these patients, slow the conversation down more. Have a family member come in with them and go into more detail.”

He added that the maximum number of concurrent prescriptions for any single patient in each age bracket tended to be two to three times higher than that of the average patient.

Dr. Jacobson acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its single-center design and relatively small sample size. There was also no comparison available as to the number of concurrent prescriptions for patients not receiving warfarin. He reported having no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Jacobson M et al. THSNA 2018. Poster 2.

SAN DIEGO – The incidence of polypharmacy among patients on warfarin therapy appears to peak at age 75, with close to 10 concurrent active prescriptions on average, results from a single-center study showed.

“Beware of polypharmacy with these patients,” Alan Jacobson, MD, said in an interview at the biennial summit of the Thrombosis & Hemostasis Societies of North America. “Anticoagulation tends to be a high-risk area. If you don’t treat, people have strokes. If you treat, they can have bleeds. Warfarin is the number one drug that gets older patients into the ER and admitted. We know that warfarin has a lot of drug-drug interactions.”

For example, in the ARISTOTLE trial, patients used a median of six drugs, and 26% of patients used nine or more drugs (BMJ. 2016 Jun 15;353:i2868.

In an effort to determine the average and maximum number of concurrent prescription drugs for age-dependent brackets of patients on warfarin, Dr. Jacobson and his associates reviewed the electronic pharmacy records of 1,122 warfarin patients at the VA Loma Linda Healthcare System. They excluded medications that could be obtained over the counter and calculated the average number of concurrent drugs for each of 10 age brackets: under age 50, over age 90, and eight brackets between those limits.

The researchers reported that 9,885 prescriptions were tabulated for the study population, which translated into a per patient average of 8.8 concurrent active prescription drugs, independent of age. They observed an age-dependent increase in the number of concurrent drugs that peaked at 9.9 among patients aged 70-74 years, and tapered off in those older than age 75. One patient in the 70- to 74-year-old age group was on 28 active prescriptions.

“If you’re on 28 pills, your chance of a bleeding complication is high,” Dr. Jacobson said. “We try to be rigorous with all of our patients on education. With these patients, slow the conversation down more. Have a family member come in with them and go into more detail.”

He added that the maximum number of concurrent prescriptions for any single patient in each age bracket tended to be two to three times higher than that of the average patient.

Dr. Jacobson acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its single-center design and relatively small sample size. There was also no comparison available as to the number of concurrent prescriptions for patients not receiving warfarin. He reported having no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Jacobson M et al. THSNA 2018. Poster 2.

REPORTING FROM THSNA 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: On average, warfarin patients had 8.8 concurrent active prescription drugs.

Study details: A review of medical records from 1,122 warfarin patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Jacobson reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Jacobson A et al. THSNA 2018. Poster 2.

Making structural improvements in health care

Every day, hospitalists devote time and energy to the best practices that can limit the spread of infection and the development of antibiotic resistance. Infection Prevention (IP) and Antimicrobial Stewardship (ASP) are two hospital programs that address that same goal.

But there may be a more effective approach possible, according to Jerome A. Leis, MD, MSc, FRCPC, of the Centre for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety at the University of Toronto.

“Despite the high-quality evidence supporting these IP/ASP interventions, our approach to adding these to our current practice sometimes feels like adding scaffolding to a rickety building,” he said. “It supports the underlying structure, but remove the scaffolding without fixing the building, and it may just come tumbling down.” Sometimes the work seems like an uphill battle, he added, as the same problems continue to recur.

That’s because there’s a systemic element to the problems. “Hospitalists know first hand about how the system that we work in makes it difficult to ensure that all the best IP/ASP practices are adhered to all the time,” Dr. Leis said. “Simply reminding staff to remove a urinary catheter in a timely fashion or clean their hands every single time they touch a patient or the environment can only get us so far.” That’s where improvement science comes in.

The relatively new field of improvement science provides a framework for research focused on health care improvement; its goal is to determine which improvement strategies are most effective. Dr. Leis argued that, “when our approach to IP and ASP incorporate principles of improvement science, we are more likely to be successful in achieving sustainable changes in practice.”

Rather than constantly adding extra steps and reminders for hospitalists about patient safety, he said, we need to recognize that there are systemic factors that lead to specific practices. “Our focus should be to use improvement-science methodology to understand these barriers and redesign the processes of care in a way that makes it easier for hospitalists to adhere to the best IP/ASP practices for our patients.”

These structural changes should come from collaboration among content experts in IP/ASP and those with training in improvement science, he said – many IP and ASP programs are already putting this in practice, using improvement science to create safer systems of care.

Reference

Leis J. Advancing infection prevention and antimicrobial stewardship through improvement science. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017 Jun 14. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006793.

Every day, hospitalists devote time and energy to the best practices that can limit the spread of infection and the development of antibiotic resistance. Infection Prevention (IP) and Antimicrobial Stewardship (ASP) are two hospital programs that address that same goal.

But there may be a more effective approach possible, according to Jerome A. Leis, MD, MSc, FRCPC, of the Centre for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety at the University of Toronto.

“Despite the high-quality evidence supporting these IP/ASP interventions, our approach to adding these to our current practice sometimes feels like adding scaffolding to a rickety building,” he said. “It supports the underlying structure, but remove the scaffolding without fixing the building, and it may just come tumbling down.” Sometimes the work seems like an uphill battle, he added, as the same problems continue to recur.

That’s because there’s a systemic element to the problems. “Hospitalists know first hand about how the system that we work in makes it difficult to ensure that all the best IP/ASP practices are adhered to all the time,” Dr. Leis said. “Simply reminding staff to remove a urinary catheter in a timely fashion or clean their hands every single time they touch a patient or the environment can only get us so far.” That’s where improvement science comes in.

The relatively new field of improvement science provides a framework for research focused on health care improvement; its goal is to determine which improvement strategies are most effective. Dr. Leis argued that, “when our approach to IP and ASP incorporate principles of improvement science, we are more likely to be successful in achieving sustainable changes in practice.”

Rather than constantly adding extra steps and reminders for hospitalists about patient safety, he said, we need to recognize that there are systemic factors that lead to specific practices. “Our focus should be to use improvement-science methodology to understand these barriers and redesign the processes of care in a way that makes it easier for hospitalists to adhere to the best IP/ASP practices for our patients.”

These structural changes should come from collaboration among content experts in IP/ASP and those with training in improvement science, he said – many IP and ASP programs are already putting this in practice, using improvement science to create safer systems of care.

Reference

Leis J. Advancing infection prevention and antimicrobial stewardship through improvement science. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017 Jun 14. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006793.

Every day, hospitalists devote time and energy to the best practices that can limit the spread of infection and the development of antibiotic resistance. Infection Prevention (IP) and Antimicrobial Stewardship (ASP) are two hospital programs that address that same goal.

But there may be a more effective approach possible, according to Jerome A. Leis, MD, MSc, FRCPC, of the Centre for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety at the University of Toronto.

“Despite the high-quality evidence supporting these IP/ASP interventions, our approach to adding these to our current practice sometimes feels like adding scaffolding to a rickety building,” he said. “It supports the underlying structure, but remove the scaffolding without fixing the building, and it may just come tumbling down.” Sometimes the work seems like an uphill battle, he added, as the same problems continue to recur.

That’s because there’s a systemic element to the problems. “Hospitalists know first hand about how the system that we work in makes it difficult to ensure that all the best IP/ASP practices are adhered to all the time,” Dr. Leis said. “Simply reminding staff to remove a urinary catheter in a timely fashion or clean their hands every single time they touch a patient or the environment can only get us so far.” That’s where improvement science comes in.

The relatively new field of improvement science provides a framework for research focused on health care improvement; its goal is to determine which improvement strategies are most effective. Dr. Leis argued that, “when our approach to IP and ASP incorporate principles of improvement science, we are more likely to be successful in achieving sustainable changes in practice.”

Rather than constantly adding extra steps and reminders for hospitalists about patient safety, he said, we need to recognize that there are systemic factors that lead to specific practices. “Our focus should be to use improvement-science methodology to understand these barriers and redesign the processes of care in a way that makes it easier for hospitalists to adhere to the best IP/ASP practices for our patients.”

These structural changes should come from collaboration among content experts in IP/ASP and those with training in improvement science, he said – many IP and ASP programs are already putting this in practice, using improvement science to create safer systems of care.

Reference

Leis J. Advancing infection prevention and antimicrobial stewardship through improvement science. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017 Jun 14. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006793.

Early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke

(AIS). Conceptually, early management can be separated into initial triage and decisions about intervention to restore blood flow with thrombolysis or mechanical thrombectomy. If reperfusion therapy is not appropriate, then the focus is on management to minimize further damage from the stroke, decrease the likelihood of recurrence, and lessen secondary problems related to the stroke.

All patients with AIS should receive noncontrast CT to determine if there is evidence of a hemorrhagic stroke and, if such evidence exists, than the patient is not a candidate for thrombolysis. Intravenous alteplase should be considered for patients who present within 3 hours of stroke onset and for selected patients presenting between 3-4.5 hours after stroke onset (for more details, see Table 6 in the guidelines). Selected patients with AIS who present within 6-24 hours of last time they were known to be normal and who have large vessel occlusion in the anterior circulation, may be candidates for mechanical thrombectomy in specialized centers. Patients who are not candidates for acute interventions should then be managed according to early stroke management guidelines.

Early stroke management for patients with AIS admitted to medical floors involves attention to blood pressure, glucose, and antiplatelet therapy. For patients with blood pressure lower than 220/120 mm Hg who did not receive IV alteplase or thrombectomy, treatment of hypertension in the first 48-72 hours after an AIS does not change the outcome. It is reasonable when patients have BP greater than or equal to 220/120 mm Hg, to lower blood pressure by 15% during the first 24 hours after onset of stroke. Starting or restarting antihypertensive therapy during hospitalization in patients with blood pressure higher than 140/90 mm Hg who are neurologically stable improves long-term blood pressure control and is considered a reasonable strategy.

For patients with noncardioembolic AIS, the use of antiplatelet agents rather than oral anticoagulation is recommended. Patients should be treated with aspirin 160 mg-325 mg within 24-48 hours of presentation. In patients unsafe or unable to swallow, rectal or nasogastric administration is recommended. In patients with minor stroke, 21 days of dual-antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel) started within 24 hours can decrease stroke recurrence for the first 90 days after a stroke. This recommendation is based on a single study, the CHANCE trial, in a homogeneous population in China, and its generalizability is not known. If a patient had an AIS while already on aspirin, there is some evidence supporting a decreased risk of major cardiovascular events and recurrent stroke in patients switching to an alternative antiplatelet agent or combination antiplatelet therapy. Because of methodologic issues in the those studies, the guideline concludes that, for those already on aspirin, it is of unclear benefit to increase the dose of aspirin, switch to a different antiplatelet agent, or add a second antiplatelet agent. Switching to warfarin is not beneficial for secondary stroke prevention. High-dose statin therapy should be initiated. For patients with AIS in the setting of atrial fibrillation, oral anticoagulation can be started within 4-14 days after the stroke. One study showed that anticoagulation should not be started before 4 days after the stroke, with a hazard ratio of 0.53 for starting anticoagulation at 4-14 days, compared with less than 4 days.

Hyperglycemia should be controlled to a range of 140-180 mg/dL, because higher values are associated with worse outcomes. Oxygen should be used if needed to maintain oxygen saturation greater than 94%. High-intensity statin therapy should be used, and smoking cessation is strongly encouraged for those who use tobacco, with avoidance of secondhand smoke whenever possible.

Patients should be screened for dysphagia before taking anything per oral, including medications. A nasogastric tube may be considered within the first 7 days, if patients are dysphagic. Oral hygiene protocols may include antibacterial mouth rinse, systematic oral care, and decontamination gel to decrease the risk of pneumonia .

For deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis, intermittent pneumatic compression, in addition to the aspirin that a patient is on is reasonable, and the benefit of prophylactic-dose subcutaneous heparin (unfractionated heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin) in immobile patients with AIS is not well established.

In the poststroke setting, patients should be screened for depression and, if appropriate, treated with antidepressants. Regular skin assessments are recommended with objective scales, and skin friction and pressure should be actively minimized with regular turning, good skin hygiene, and use of specialized mattresses, wheelchair cushions, and seating until mobility returns. Early rehabilitation for hospitalized stroke patients should be provided, but high-dose, very-early mobilization within 24 hours of stroke should not be done because it reduces the odds of a favorable outcome at 3 months.

Completing the diagnostic evaluation for the cause of stroke and decreasing the chance of future strokes should be part of the initial hospitalization. While MRI is more sensitive than is CT for detecting AIS, routine use of MRI in all patients with AIS is not cost effective and therefore is not recommended. For patients with nondisabling AIS in the carotid territory and who are candidates for carotid endarterectomy or stenting, noninvasive imaging of the cervical vessels should be performed within 24 hours of admission, with plans for carotid revascularization between 48 hours and 7 days if indicated. Cardiac monitoring for at least the first 24 hours of admission should be performed, while primarily looking for atrial fibrillation as a cause of stroke. In some patients, prolonged cardiac monitoring may be reasonable. With prolonged cardiac monitoring, atrial fibrillation is newly detected in nearly a quarter of patients with stroke or TIA, but the effect on outcomes is uncertain. Routine use of echocardiography is not recommended but may be done in selected patients. All patients should be screened for diabetes. It is not clear whether screening for thrombophilic states is useful.

All patients should be counseled on stroke, and provided education about it and how it will affect their lives. Following their acute medical stay, all patients will benefit from rehabilitation, with the benefits associated using a program tailored to their needs and outcome goals.

The bottom line

Early management of stroke involves first determining whether someone is a candidate for reperfusion therapy with alteplase or thrombectomy and then, if not, admitting them to a monitored setting to screen for atrial fibrillation and evaluation for carotid stenosis. Patients should be evaluated for both depression and swallowing function, and there should be initiation of deep vein thrombosis prevention, appropriate management of elevated blood pressures, anti-platelet therapy, and statin therapy as well as plans for rehabilitation services.

Reference

Powers WJ et al. on behalf of the American Heart Association Stroke Council. 2018 Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018 Mar;49(3):e46-e110.

Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Callahan is an attending physician and preceptor in the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

(AIS). Conceptually, early management can be separated into initial triage and decisions about intervention to restore blood flow with thrombolysis or mechanical thrombectomy. If reperfusion therapy is not appropriate, then the focus is on management to minimize further damage from the stroke, decrease the likelihood of recurrence, and lessen secondary problems related to the stroke.

All patients with AIS should receive noncontrast CT to determine if there is evidence of a hemorrhagic stroke and, if such evidence exists, than the patient is not a candidate for thrombolysis. Intravenous alteplase should be considered for patients who present within 3 hours of stroke onset and for selected patients presenting between 3-4.5 hours after stroke onset (for more details, see Table 6 in the guidelines). Selected patients with AIS who present within 6-24 hours of last time they were known to be normal and who have large vessel occlusion in the anterior circulation, may be candidates for mechanical thrombectomy in specialized centers. Patients who are not candidates for acute interventions should then be managed according to early stroke management guidelines.

Early stroke management for patients with AIS admitted to medical floors involves attention to blood pressure, glucose, and antiplatelet therapy. For patients with blood pressure lower than 220/120 mm Hg who did not receive IV alteplase or thrombectomy, treatment of hypertension in the first 48-72 hours after an AIS does not change the outcome. It is reasonable when patients have BP greater than or equal to 220/120 mm Hg, to lower blood pressure by 15% during the first 24 hours after onset of stroke. Starting or restarting antihypertensive therapy during hospitalization in patients with blood pressure higher than 140/90 mm Hg who are neurologically stable improves long-term blood pressure control and is considered a reasonable strategy.

For patients with noncardioembolic AIS, the use of antiplatelet agents rather than oral anticoagulation is recommended. Patients should be treated with aspirin 160 mg-325 mg within 24-48 hours of presentation. In patients unsafe or unable to swallow, rectal or nasogastric administration is recommended. In patients with minor stroke, 21 days of dual-antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel) started within 24 hours can decrease stroke recurrence for the first 90 days after a stroke. This recommendation is based on a single study, the CHANCE trial, in a homogeneous population in China, and its generalizability is not known. If a patient had an AIS while already on aspirin, there is some evidence supporting a decreased risk of major cardiovascular events and recurrent stroke in patients switching to an alternative antiplatelet agent or combination antiplatelet therapy. Because of methodologic issues in the those studies, the guideline concludes that, for those already on aspirin, it is of unclear benefit to increase the dose of aspirin, switch to a different antiplatelet agent, or add a second antiplatelet agent. Switching to warfarin is not beneficial for secondary stroke prevention. High-dose statin therapy should be initiated. For patients with AIS in the setting of atrial fibrillation, oral anticoagulation can be started within 4-14 days after the stroke. One study showed that anticoagulation should not be started before 4 days after the stroke, with a hazard ratio of 0.53 for starting anticoagulation at 4-14 days, compared with less than 4 days.

Hyperglycemia should be controlled to a range of 140-180 mg/dL, because higher values are associated with worse outcomes. Oxygen should be used if needed to maintain oxygen saturation greater than 94%. High-intensity statin therapy should be used, and smoking cessation is strongly encouraged for those who use tobacco, with avoidance of secondhand smoke whenever possible.

Patients should be screened for dysphagia before taking anything per oral, including medications. A nasogastric tube may be considered within the first 7 days, if patients are dysphagic. Oral hygiene protocols may include antibacterial mouth rinse, systematic oral care, and decontamination gel to decrease the risk of pneumonia .

For deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis, intermittent pneumatic compression, in addition to the aspirin that a patient is on is reasonable, and the benefit of prophylactic-dose subcutaneous heparin (unfractionated heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin) in immobile patients with AIS is not well established.

In the poststroke setting, patients should be screened for depression and, if appropriate, treated with antidepressants. Regular skin assessments are recommended with objective scales, and skin friction and pressure should be actively minimized with regular turning, good skin hygiene, and use of specialized mattresses, wheelchair cushions, and seating until mobility returns. Early rehabilitation for hospitalized stroke patients should be provided, but high-dose, very-early mobilization within 24 hours of stroke should not be done because it reduces the odds of a favorable outcome at 3 months.

Completing the diagnostic evaluation for the cause of stroke and decreasing the chance of future strokes should be part of the initial hospitalization. While MRI is more sensitive than is CT for detecting AIS, routine use of MRI in all patients with AIS is not cost effective and therefore is not recommended. For patients with nondisabling AIS in the carotid territory and who are candidates for carotid endarterectomy or stenting, noninvasive imaging of the cervical vessels should be performed within 24 hours of admission, with plans for carotid revascularization between 48 hours and 7 days if indicated. Cardiac monitoring for at least the first 24 hours of admission should be performed, while primarily looking for atrial fibrillation as a cause of stroke. In some patients, prolonged cardiac monitoring may be reasonable. With prolonged cardiac monitoring, atrial fibrillation is newly detected in nearly a quarter of patients with stroke or TIA, but the effect on outcomes is uncertain. Routine use of echocardiography is not recommended but may be done in selected patients. All patients should be screened for diabetes. It is not clear whether screening for thrombophilic states is useful.

All patients should be counseled on stroke, and provided education about it and how it will affect their lives. Following their acute medical stay, all patients will benefit from rehabilitation, with the benefits associated using a program tailored to their needs and outcome goals.

The bottom line

Early management of stroke involves first determining whether someone is a candidate for reperfusion therapy with alteplase or thrombectomy and then, if not, admitting them to a monitored setting to screen for atrial fibrillation and evaluation for carotid stenosis. Patients should be evaluated for both depression and swallowing function, and there should be initiation of deep vein thrombosis prevention, appropriate management of elevated blood pressures, anti-platelet therapy, and statin therapy as well as plans for rehabilitation services.

Reference

Powers WJ et al. on behalf of the American Heart Association Stroke Council. 2018 Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018 Mar;49(3):e46-e110.

Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Callahan is an attending physician and preceptor in the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

(AIS). Conceptually, early management can be separated into initial triage and decisions about intervention to restore blood flow with thrombolysis or mechanical thrombectomy. If reperfusion therapy is not appropriate, then the focus is on management to minimize further damage from the stroke, decrease the likelihood of recurrence, and lessen secondary problems related to the stroke.

All patients with AIS should receive noncontrast CT to determine if there is evidence of a hemorrhagic stroke and, if such evidence exists, than the patient is not a candidate for thrombolysis. Intravenous alteplase should be considered for patients who present within 3 hours of stroke onset and for selected patients presenting between 3-4.5 hours after stroke onset (for more details, see Table 6 in the guidelines). Selected patients with AIS who present within 6-24 hours of last time they were known to be normal and who have large vessel occlusion in the anterior circulation, may be candidates for mechanical thrombectomy in specialized centers. Patients who are not candidates for acute interventions should then be managed according to early stroke management guidelines.

Early stroke management for patients with AIS admitted to medical floors involves attention to blood pressure, glucose, and antiplatelet therapy. For patients with blood pressure lower than 220/120 mm Hg who did not receive IV alteplase or thrombectomy, treatment of hypertension in the first 48-72 hours after an AIS does not change the outcome. It is reasonable when patients have BP greater than or equal to 220/120 mm Hg, to lower blood pressure by 15% during the first 24 hours after onset of stroke. Starting or restarting antihypertensive therapy during hospitalization in patients with blood pressure higher than 140/90 mm Hg who are neurologically stable improves long-term blood pressure control and is considered a reasonable strategy.

For patients with noncardioembolic AIS, the use of antiplatelet agents rather than oral anticoagulation is recommended. Patients should be treated with aspirin 160 mg-325 mg within 24-48 hours of presentation. In patients unsafe or unable to swallow, rectal or nasogastric administration is recommended. In patients with minor stroke, 21 days of dual-antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel) started within 24 hours can decrease stroke recurrence for the first 90 days after a stroke. This recommendation is based on a single study, the CHANCE trial, in a homogeneous population in China, and its generalizability is not known. If a patient had an AIS while already on aspirin, there is some evidence supporting a decreased risk of major cardiovascular events and recurrent stroke in patients switching to an alternative antiplatelet agent or combination antiplatelet therapy. Because of methodologic issues in the those studies, the guideline concludes that, for those already on aspirin, it is of unclear benefit to increase the dose of aspirin, switch to a different antiplatelet agent, or add a second antiplatelet agent. Switching to warfarin is not beneficial for secondary stroke prevention. High-dose statin therapy should be initiated. For patients with AIS in the setting of atrial fibrillation, oral anticoagulation can be started within 4-14 days after the stroke. One study showed that anticoagulation should not be started before 4 days after the stroke, with a hazard ratio of 0.53 for starting anticoagulation at 4-14 days, compared with less than 4 days.

Hyperglycemia should be controlled to a range of 140-180 mg/dL, because higher values are associated with worse outcomes. Oxygen should be used if needed to maintain oxygen saturation greater than 94%. High-intensity statin therapy should be used, and smoking cessation is strongly encouraged for those who use tobacco, with avoidance of secondhand smoke whenever possible.

Patients should be screened for dysphagia before taking anything per oral, including medications. A nasogastric tube may be considered within the first 7 days, if patients are dysphagic. Oral hygiene protocols may include antibacterial mouth rinse, systematic oral care, and decontamination gel to decrease the risk of pneumonia .

For deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis, intermittent pneumatic compression, in addition to the aspirin that a patient is on is reasonable, and the benefit of prophylactic-dose subcutaneous heparin (unfractionated heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin) in immobile patients with AIS is not well established.

In the poststroke setting, patients should be screened for depression and, if appropriate, treated with antidepressants. Regular skin assessments are recommended with objective scales, and skin friction and pressure should be actively minimized with regular turning, good skin hygiene, and use of specialized mattresses, wheelchair cushions, and seating until mobility returns. Early rehabilitation for hospitalized stroke patients should be provided, but high-dose, very-early mobilization within 24 hours of stroke should not be done because it reduces the odds of a favorable outcome at 3 months.

Completing the diagnostic evaluation for the cause of stroke and decreasing the chance of future strokes should be part of the initial hospitalization. While MRI is more sensitive than is CT for detecting AIS, routine use of MRI in all patients with AIS is not cost effective and therefore is not recommended. For patients with nondisabling AIS in the carotid territory and who are candidates for carotid endarterectomy or stenting, noninvasive imaging of the cervical vessels should be performed within 24 hours of admission, with plans for carotid revascularization between 48 hours and 7 days if indicated. Cardiac monitoring for at least the first 24 hours of admission should be performed, while primarily looking for atrial fibrillation as a cause of stroke. In some patients, prolonged cardiac monitoring may be reasonable. With prolonged cardiac monitoring, atrial fibrillation is newly detected in nearly a quarter of patients with stroke or TIA, but the effect on outcomes is uncertain. Routine use of echocardiography is not recommended but may be done in selected patients. All patients should be screened for diabetes. It is not clear whether screening for thrombophilic states is useful.

All patients should be counseled on stroke, and provided education about it and how it will affect their lives. Following their acute medical stay, all patients will benefit from rehabilitation, with the benefits associated using a program tailored to their needs and outcome goals.

The bottom line

Early management of stroke involves first determining whether someone is a candidate for reperfusion therapy with alteplase or thrombectomy and then, if not, admitting them to a monitored setting to screen for atrial fibrillation and evaluation for carotid stenosis. Patients should be evaluated for both depression and swallowing function, and there should be initiation of deep vein thrombosis prevention, appropriate management of elevated blood pressures, anti-platelet therapy, and statin therapy as well as plans for rehabilitation services.

Reference

Powers WJ et al. on behalf of the American Heart Association Stroke Council. 2018 Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018 Mar;49(3):e46-e110.

Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Callahan is an attending physician and preceptor in the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

Abdominal pain with high transaminases

A 54-year-old woman presents with severe abdominal pain lasting 3 hours. The pain came on suddenly and was 10/10 in severity. It was in her right upper quadrant radiating to her back. She has had a 50-pound weight loss in the past year. Her medications include sertraline, phentermine-topiramate, and simvastatin.

She is evaluated in the emergency department, and labs show the following: aspartate aminotransferase, 450; alanine aminotransferase, 500; alkaline phosphatase, 100; bilirubin, 1.2. She receives morphine for her pain with minimal relief. An ultrasound shows no gallstones and no dilated common bile duct (CBD).

Her pain resolves 3 hours after arriving in the ED. Repeat labs 15 minutes after pain resolution show the following: AST, 900; ALT, 1,000; alk phos, 130; bili, 1.2.

What is the most likely diagnosis?

A. Acetaminophen toxicity.

B. Hepatitis A.

C. Ischemic hepatitis.

D. Simvastatin.

E. Passage of gallstone.

The correct answer in this case is passage of a gallstone.

The patient has had weight loss, which increases the risk of gallstone formation, and the pain pattern is consistent with passage of a gallstone through the common bile duct.

I have seen a number of cases where the diagnosis was missed when the lab pattern is similar to the labs in this case. The high transaminases and the absence of significant alkaline phosphatase elevation can be confusing. We are taught in our medical training that alkaline phosphatase is a lab value that goes up with obstruction, and that transaminases are liver injury labs. What are the data on liver labs in the setting of acute obstruction as seen with the passage of a gallstone?

Frederick Kiechle, MD, and colleagues reported that alkaline phosphatase levels, either alone or in conjunction with bilirubin levels, were not useful in determining the presence of common bile duct stones.1 Ming-Hsun Yang et al. found that normal gamma-glutamyl transferase results had the highest negative predictive value for the presence of a common bile duct stone (97%).2 The sensitivity for ultrasound detection of CBD stone in this study was only 35%.

Keun Soo Ahn and colleagues found that, in patients with symptomatic CBD stones, the average AST was 275, and the average ALT was 317 – about six to seven times the upper limit of normal for these lab tests.3 In the same study, the average alkaline phosphatase was 213, which is about twice the upper limit of normal.

Sometimes, extremely high transaminase elevations can occur with choledocholithiasis. Saroja Bangaru et al. reported on a case series of patients who all had transaminase values greater than 1,000 with symptomatic choledocholithiasis.4 All of the patients had normal or just mildly elevated alkaline phosphatase levels.

Rahul Nathwani, MD, and colleagues also reported on a series of 16 patients with choledocholithiasis and transaminase levels greater than 1,000.5 All patients were symptomatic, and the average alkaline phosphatase levels were 2.5 times the upper limit of normal.

Ala Sharara, MD, et al. looked at 40 patients in a retrospective study of patients found to have choledocholithiasis who presented within 12 hours of pain onset.6 Levels of AST and ALT both significantly correlated with duration of pain (P less than .001), whereas there was no significant correlation with alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin levels.

Pearl: AST and ALT elevations in patients with acute abdominal pain could be due to choledocholithiasis, even if there are minimal or no abnormalities in alkaline phosphatase. Marked elevations (greater than 1,000) can occur.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Am J Emerg Med. 1985 Nov;3(6):556-60.

2. Surg Endosc. 2008 Jul;22(7):1620-4.

3. World J Surg. 2016 Aug;40(8):1925-31.

4. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017 Sep;51(8):728-33.

5. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005 Feb;100(2):295-8.

6. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Dec;8(12):1077-82.

A 54-year-old woman presents with severe abdominal pain lasting 3 hours. The pain came on suddenly and was 10/10 in severity. It was in her right upper quadrant radiating to her back. She has had a 50-pound weight loss in the past year. Her medications include sertraline, phentermine-topiramate, and simvastatin.

She is evaluated in the emergency department, and labs show the following: aspartate aminotransferase, 450; alanine aminotransferase, 500; alkaline phosphatase, 100; bilirubin, 1.2. She receives morphine for her pain with minimal relief. An ultrasound shows no gallstones and no dilated common bile duct (CBD).

Her pain resolves 3 hours after arriving in the ED. Repeat labs 15 minutes after pain resolution show the following: AST, 900; ALT, 1,000; alk phos, 130; bili, 1.2.

What is the most likely diagnosis?

A. Acetaminophen toxicity.

B. Hepatitis A.

C. Ischemic hepatitis.

D. Simvastatin.

E. Passage of gallstone.

The correct answer in this case is passage of a gallstone.

The patient has had weight loss, which increases the risk of gallstone formation, and the pain pattern is consistent with passage of a gallstone through the common bile duct.

I have seen a number of cases where the diagnosis was missed when the lab pattern is similar to the labs in this case. The high transaminases and the absence of significant alkaline phosphatase elevation can be confusing. We are taught in our medical training that alkaline phosphatase is a lab value that goes up with obstruction, and that transaminases are liver injury labs. What are the data on liver labs in the setting of acute obstruction as seen with the passage of a gallstone?

Frederick Kiechle, MD, and colleagues reported that alkaline phosphatase levels, either alone or in conjunction with bilirubin levels, were not useful in determining the presence of common bile duct stones.1 Ming-Hsun Yang et al. found that normal gamma-glutamyl transferase results had the highest negative predictive value for the presence of a common bile duct stone (97%).2 The sensitivity for ultrasound detection of CBD stone in this study was only 35%.

Keun Soo Ahn and colleagues found that, in patients with symptomatic CBD stones, the average AST was 275, and the average ALT was 317 – about six to seven times the upper limit of normal for these lab tests.3 In the same study, the average alkaline phosphatase was 213, which is about twice the upper limit of normal.

Sometimes, extremely high transaminase elevations can occur with choledocholithiasis. Saroja Bangaru et al. reported on a case series of patients who all had transaminase values greater than 1,000 with symptomatic choledocholithiasis.4 All of the patients had normal or just mildly elevated alkaline phosphatase levels.

Rahul Nathwani, MD, and colleagues also reported on a series of 16 patients with choledocholithiasis and transaminase levels greater than 1,000.5 All patients were symptomatic, and the average alkaline phosphatase levels were 2.5 times the upper limit of normal.

Ala Sharara, MD, et al. looked at 40 patients in a retrospective study of patients found to have choledocholithiasis who presented within 12 hours of pain onset.6 Levels of AST and ALT both significantly correlated with duration of pain (P less than .001), whereas there was no significant correlation with alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin levels.

Pearl: AST and ALT elevations in patients with acute abdominal pain could be due to choledocholithiasis, even if there are minimal or no abnormalities in alkaline phosphatase. Marked elevations (greater than 1,000) can occur.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Am J Emerg Med. 1985 Nov;3(6):556-60.

2. Surg Endosc. 2008 Jul;22(7):1620-4.

3. World J Surg. 2016 Aug;40(8):1925-31.

4. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017 Sep;51(8):728-33.

5. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005 Feb;100(2):295-8.

6. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Dec;8(12):1077-82.

A 54-year-old woman presents with severe abdominal pain lasting 3 hours. The pain came on suddenly and was 10/10 in severity. It was in her right upper quadrant radiating to her back. She has had a 50-pound weight loss in the past year. Her medications include sertraline, phentermine-topiramate, and simvastatin.

She is evaluated in the emergency department, and labs show the following: aspartate aminotransferase, 450; alanine aminotransferase, 500; alkaline phosphatase, 100; bilirubin, 1.2. She receives morphine for her pain with minimal relief. An ultrasound shows no gallstones and no dilated common bile duct (CBD).

Her pain resolves 3 hours after arriving in the ED. Repeat labs 15 minutes after pain resolution show the following: AST, 900; ALT, 1,000; alk phos, 130; bili, 1.2.

What is the most likely diagnosis?

A. Acetaminophen toxicity.

B. Hepatitis A.

C. Ischemic hepatitis.

D. Simvastatin.

E. Passage of gallstone.

The correct answer in this case is passage of a gallstone.

The patient has had weight loss, which increases the risk of gallstone formation, and the pain pattern is consistent with passage of a gallstone through the common bile duct.

I have seen a number of cases where the diagnosis was missed when the lab pattern is similar to the labs in this case. The high transaminases and the absence of significant alkaline phosphatase elevation can be confusing. We are taught in our medical training that alkaline phosphatase is a lab value that goes up with obstruction, and that transaminases are liver injury labs. What are the data on liver labs in the setting of acute obstruction as seen with the passage of a gallstone?

Frederick Kiechle, MD, and colleagues reported that alkaline phosphatase levels, either alone or in conjunction with bilirubin levels, were not useful in determining the presence of common bile duct stones.1 Ming-Hsun Yang et al. found that normal gamma-glutamyl transferase results had the highest negative predictive value for the presence of a common bile duct stone (97%).2 The sensitivity for ultrasound detection of CBD stone in this study was only 35%.

Keun Soo Ahn and colleagues found that, in patients with symptomatic CBD stones, the average AST was 275, and the average ALT was 317 – about six to seven times the upper limit of normal for these lab tests.3 In the same study, the average alkaline phosphatase was 213, which is about twice the upper limit of normal.

Sometimes, extremely high transaminase elevations can occur with choledocholithiasis. Saroja Bangaru et al. reported on a case series of patients who all had transaminase values greater than 1,000 with symptomatic choledocholithiasis.4 All of the patients had normal or just mildly elevated alkaline phosphatase levels.

Rahul Nathwani, MD, and colleagues also reported on a series of 16 patients with choledocholithiasis and transaminase levels greater than 1,000.5 All patients were symptomatic, and the average alkaline phosphatase levels were 2.5 times the upper limit of normal.

Ala Sharara, MD, et al. looked at 40 patients in a retrospective study of patients found to have choledocholithiasis who presented within 12 hours of pain onset.6 Levels of AST and ALT both significantly correlated with duration of pain (P less than .001), whereas there was no significant correlation with alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin levels.

Pearl: AST and ALT elevations in patients with acute abdominal pain could be due to choledocholithiasis, even if there are minimal or no abnormalities in alkaline phosphatase. Marked elevations (greater than 1,000) can occur.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Am J Emerg Med. 1985 Nov;3(6):556-60.

2. Surg Endosc. 2008 Jul;22(7):1620-4.

3. World J Surg. 2016 Aug;40(8):1925-31.

4. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017 Sep;51(8):728-33.

5. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005 Feb;100(2):295-8.

6. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Dec;8(12):1077-82.

New tool improves hand-off communications

Transitions of care can be rife with communications issues – and subsequent adverse events. They are also a place where hospitalists can take the lead in making improvements.

“They are the team leaders, typically,” said Ana Pujols McKee, MD, the executive vice president and chief medical officer for The Joint Commission. “The hospitalist really owns this process of the transfer of this accurate information.”

To help, The Joint Commission has issued a new Sentinel Event Alert, which provides seven recommendations to improve the communication failures that can occur when patients are transitioned from one caregiver to another, as well as a Targeted Solutions Tool to put the recommendations into action.

“Every organization is challenged in communicating accurate and timely information regarding patients,” Dr. McKee said. “One of the riskiest transitions that patients go through is when they change levels of care from ICU to med-surg, or from the ER to ICU, OR to ICU, med-surg to home, and home to home care. All of those transitions inherently carry a certain amount of risk and are deeply reliant on the transfer of the right information at the right time to the right person.”

These resources reflect what The Joint Commission has found: “The knowledge that we now have is that one of the defects that occurs in this transitioning is that – I’ll speak of sender and receiver – the information that is sent is always sent from the perspective of what the sender thinks is important, not the information the receiver needs to manage that patient safely.”

The tool uses the principles of Lean Six Sigma and change management, and organizations can use it to identify their opportunities for improvement and develop strategies to address their specific root causes in their organization.

“It’s a self-guided tool,” Dr. McKee said. “Organizations have reduced errors significantly in using this tool. I think if the hospitalist community takes this on, that would really help transform how we do transitions of care.”

Transitions of care can be rife with communications issues – and subsequent adverse events. They are also a place where hospitalists can take the lead in making improvements.

“They are the team leaders, typically,” said Ana Pujols McKee, MD, the executive vice president and chief medical officer for The Joint Commission. “The hospitalist really owns this process of the transfer of this accurate information.”

To help, The Joint Commission has issued a new Sentinel Event Alert, which provides seven recommendations to improve the communication failures that can occur when patients are transitioned from one caregiver to another, as well as a Targeted Solutions Tool to put the recommendations into action.

“Every organization is challenged in communicating accurate and timely information regarding patients,” Dr. McKee said. “One of the riskiest transitions that patients go through is when they change levels of care from ICU to med-surg, or from the ER to ICU, OR to ICU, med-surg to home, and home to home care. All of those transitions inherently carry a certain amount of risk and are deeply reliant on the transfer of the right information at the right time to the right person.”

These resources reflect what The Joint Commission has found: “The knowledge that we now have is that one of the defects that occurs in this transitioning is that – I’ll speak of sender and receiver – the information that is sent is always sent from the perspective of what the sender thinks is important, not the information the receiver needs to manage that patient safely.”

The tool uses the principles of Lean Six Sigma and change management, and organizations can use it to identify their opportunities for improvement and develop strategies to address their specific root causes in their organization.

“It’s a self-guided tool,” Dr. McKee said. “Organizations have reduced errors significantly in using this tool. I think if the hospitalist community takes this on, that would really help transform how we do transitions of care.”

Transitions of care can be rife with communications issues – and subsequent adverse events. They are also a place where hospitalists can take the lead in making improvements.

“They are the team leaders, typically,” said Ana Pujols McKee, MD, the executive vice president and chief medical officer for The Joint Commission. “The hospitalist really owns this process of the transfer of this accurate information.”

To help, The Joint Commission has issued a new Sentinel Event Alert, which provides seven recommendations to improve the communication failures that can occur when patients are transitioned from one caregiver to another, as well as a Targeted Solutions Tool to put the recommendations into action.

“Every organization is challenged in communicating accurate and timely information regarding patients,” Dr. McKee said. “One of the riskiest transitions that patients go through is when they change levels of care from ICU to med-surg, or from the ER to ICU, OR to ICU, med-surg to home, and home to home care. All of those transitions inherently carry a certain amount of risk and are deeply reliant on the transfer of the right information at the right time to the right person.”

These resources reflect what The Joint Commission has found: “The knowledge that we now have is that one of the defects that occurs in this transitioning is that – I’ll speak of sender and receiver – the information that is sent is always sent from the perspective of what the sender thinks is important, not the information the receiver needs to manage that patient safely.”

The tool uses the principles of Lean Six Sigma and change management, and organizations can use it to identify their opportunities for improvement and develop strategies to address their specific root causes in their organization.

“It’s a self-guided tool,” Dr. McKee said. “Organizations have reduced errors significantly in using this tool. I think if the hospitalist community takes this on, that would really help transform how we do transitions of care.”

DOACs may be beneficial in post-op atrial fib after CABG

SAN DIEGO – The use of direct oral anticoagulants were not significantly different from warfarin for safety and efficacy in cases of postoperative atrial fibrillation following coronary artery bypass grafting, according to results from a single-center study.

In fact, , which suggests a potential for reduced hospital stay-related costs. “There are several different niche populations for which the DOACs have not been studied,” one of the study authors, Ammie J. Patel, PharmD, said in an interview at the biennial summit of the Thrombosis & Hemostasis Societies of North America. “This provides the opportunity for institutions and hospitals to study the use of these drugs in non-traditional ways.”

Dr. Patel, of Temple University, Philadelphia, said that postoperative atrial fibrillation occurs in about 30% of patients following CABG and that new-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation after CABG has been linked to a 21% increase in relative mortality.

Noting that patients with planned major surgery were excluded from RE-LY, ROCKET AF, ARISTOTLE, and other pivotal clinical trials of DOACs, she and her research mentor, Rachael Durie, PharmD, retrospectively evaluated the safety and efficacy of DOACs in 285 cases of new-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation following CABG performed at Jersey Shore University Medical Center, Neptune, N.J., between July 1, 2014, and June 30, 2016. They hypothesized that using DOACs in this patient population might offer advantages over warfarin, including rapid onset and earlier hospital discharge, fewer drug interactions, and no coagulation monitoring.

Of the 146 patients on anticoagulants, 79 were discharged on warfarin, 43 on apixaban, 20 on rivaroxaban, and 4 on dabigatran. The other 139 patients were not anticoagulated for various reasons, one of which included normal sinus rhythm at discharge.

The researchers found that the DOACs were not significantly different from warfarin for efficacy endpoints in stroke (P = 0.23) or systemic embolism (P = 0.68). Safety endpoints also were similar among all groups for major bleeding (P = 0.57) or minor bleeding (P = 0.63). Median post-CABG length of stay was significantly longer in the warfarin group (8 days, P = 0.005), compared with dabigatran (7.5 days), rivaroxaban (6.5 days), and apixaban (6 days). In addition, the median total hospital length of stay was significantly longer with warfarin (11 days, P = 0.004), compared with rivaroxaban (8.5 days) and apixaban (9 days), but not compared with dabigatran (12 days).

Dr. Patel acknowledged that the study’s retrospective design and small sample size are limitations and said that larger prospective trials are warranted to confirm these results. She reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Patel AJ et al. THSNA 2018. Poster 64.

SAN DIEGO – The use of direct oral anticoagulants were not significantly different from warfarin for safety and efficacy in cases of postoperative atrial fibrillation following coronary artery bypass grafting, according to results from a single-center study.

In fact, , which suggests a potential for reduced hospital stay-related costs. “There are several different niche populations for which the DOACs have not been studied,” one of the study authors, Ammie J. Patel, PharmD, said in an interview at the biennial summit of the Thrombosis & Hemostasis Societies of North America. “This provides the opportunity for institutions and hospitals to study the use of these drugs in non-traditional ways.”

Dr. Patel, of Temple University, Philadelphia, said that postoperative atrial fibrillation occurs in about 30% of patients following CABG and that new-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation after CABG has been linked to a 21% increase in relative mortality.

Noting that patients with planned major surgery were excluded from RE-LY, ROCKET AF, ARISTOTLE, and other pivotal clinical trials of DOACs, she and her research mentor, Rachael Durie, PharmD, retrospectively evaluated the safety and efficacy of DOACs in 285 cases of new-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation following CABG performed at Jersey Shore University Medical Center, Neptune, N.J., between July 1, 2014, and June 30, 2016. They hypothesized that using DOACs in this patient population might offer advantages over warfarin, including rapid onset and earlier hospital discharge, fewer drug interactions, and no coagulation monitoring.

Of the 146 patients on anticoagulants, 79 were discharged on warfarin, 43 on apixaban, 20 on rivaroxaban, and 4 on dabigatran. The other 139 patients were not anticoagulated for various reasons, one of which included normal sinus rhythm at discharge.

The researchers found that the DOACs were not significantly different from warfarin for efficacy endpoints in stroke (P = 0.23) or systemic embolism (P = 0.68). Safety endpoints also were similar among all groups for major bleeding (P = 0.57) or minor bleeding (P = 0.63). Median post-CABG length of stay was significantly longer in the warfarin group (8 days, P = 0.005), compared with dabigatran (7.5 days), rivaroxaban (6.5 days), and apixaban (6 days). In addition, the median total hospital length of stay was significantly longer with warfarin (11 days, P = 0.004), compared with rivaroxaban (8.5 days) and apixaban (9 days), but not compared with dabigatran (12 days).

Dr. Patel acknowledged that the study’s retrospective design and small sample size are limitations and said that larger prospective trials are warranted to confirm these results. She reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Patel AJ et al. THSNA 2018. Poster 64.

SAN DIEGO – The use of direct oral anticoagulants were not significantly different from warfarin for safety and efficacy in cases of postoperative atrial fibrillation following coronary artery bypass grafting, according to results from a single-center study.

In fact, , which suggests a potential for reduced hospital stay-related costs. “There are several different niche populations for which the DOACs have not been studied,” one of the study authors, Ammie J. Patel, PharmD, said in an interview at the biennial summit of the Thrombosis & Hemostasis Societies of North America. “This provides the opportunity for institutions and hospitals to study the use of these drugs in non-traditional ways.”

Dr. Patel, of Temple University, Philadelphia, said that postoperative atrial fibrillation occurs in about 30% of patients following CABG and that new-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation after CABG has been linked to a 21% increase in relative mortality.

Noting that patients with planned major surgery were excluded from RE-LY, ROCKET AF, ARISTOTLE, and other pivotal clinical trials of DOACs, she and her research mentor, Rachael Durie, PharmD, retrospectively evaluated the safety and efficacy of DOACs in 285 cases of new-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation following CABG performed at Jersey Shore University Medical Center, Neptune, N.J., between July 1, 2014, and June 30, 2016. They hypothesized that using DOACs in this patient population might offer advantages over warfarin, including rapid onset and earlier hospital discharge, fewer drug interactions, and no coagulation monitoring.

Of the 146 patients on anticoagulants, 79 were discharged on warfarin, 43 on apixaban, 20 on rivaroxaban, and 4 on dabigatran. The other 139 patients were not anticoagulated for various reasons, one of which included normal sinus rhythm at discharge.

The researchers found that the DOACs were not significantly different from warfarin for efficacy endpoints in stroke (P = 0.23) or systemic embolism (P = 0.68). Safety endpoints also were similar among all groups for major bleeding (P = 0.57) or minor bleeding (P = 0.63). Median post-CABG length of stay was significantly longer in the warfarin group (8 days, P = 0.005), compared with dabigatran (7.5 days), rivaroxaban (6.5 days), and apixaban (6 days). In addition, the median total hospital length of stay was significantly longer with warfarin (11 days, P = 0.004), compared with rivaroxaban (8.5 days) and apixaban (9 days), but not compared with dabigatran (12 days).

Dr. Patel acknowledged that the study’s retrospective design and small sample size are limitations and said that larger prospective trials are warranted to confirm these results. She reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Patel AJ et al. THSNA 2018. Poster 64.

REPORTING FROM THSNA 2018

Key clinical point: DOACs may be safe and effective alternatives to warfarin in postoperative atrial fibrillation after CABG.

Major finding: DOACs were not significantly different from warfarin for efficacy endpoints in stroke (P = 0.23) or systemic embolism (P = 0.68).

Study details: A retrospective, single-center study of DOACs in 285 cases of new-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation following CABG.

Disclosures: Dr. Patel reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Patel AJ et al. THSNA 2018. Poster 64.

When should nutritional support be implemented in a hospitalized patient?

Case

A 60-year-old male with a history of head & neck cancer, treated with radical neck dissection and radiation 5 years prior is admitted with community-acquired pneumonia and anasarca. Prior to admission, he was on a soft dysphagia diet and reports increased difficulty with solid foods and weight loss from 70 kg to 55 kg over 2.5 years. Should nutritional support be initiated?

Background

Malnutrition is associated with increased hospital mortality, decreased functional status and quality of life, infections, longer length of stay, higher hospital costs, and more frequent nonelective readmissions.1,2

Identifying patients who are malnourished or at risk for malnutrition

An international consensus committee recommended the following criteria for the diagnosis of undernutrition if two of six are present3:

- Insufficient energy intake.

- Weight loss.

- Loss of muscle mass.

- Loss of subcutaneous fat.

- Localized or generalized fluid accumulation that may sometimes mask weight loss.

- Diminished functional status as measured by handgrip strength.

The joint commission requires that all patients admitted to acute care hospitals be screened for risk of malnutrition within 24 hours. The American College of Gastroenterologists recommends using a validated score to assess nutritional risk, such as the Nutritional Risk Score (NRS) 2002 or the NUTRIC (Nutrition Risk in the Critically Ill) Score, which use a combination of nutritional status and diet-related factors – weight loss, body mass index, and food intake – and also severity of illness measurements.4

- Starvation-related malnutrition, such as anorexia nervosa, presents with a deficiency in calories and protein without inflammation, .

- Chronic disease–related malnutrition, such as that caused chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, and obesity, presents with mild to moderate inflammation.

- Acute disease or injury–related malnutrition, such as that caused by sepsis, burns, and trauma, presents with acute and severe inflammation.

Laboratory indicators such as albumin, prealbumin, and transferrin are not recommended for the determination of nutritional status. Instead, as negative acute-phase reactants, they can be used as surrogate markers of nutritional risk and degree of inflammation.4

Overview of the data

What are the indications for initiating nutritional support, and what is the optimal timing for initiation?

Patients who are malnourished or at significant risk for becoming malnourished should receive specialized nutrition support. Early enteral nutrition should be initiated within 24-48 hours of admission in critically ill patients with high nutritional risk who are unable to maintain volitional intake.6 In the absence of preexisting malnutrition, nutritional support should be provided for patients with inadequate oral intake for 7-14 days or for those in whom inadequate oral intake is expected over the same time period.7

How should nutritional support be administered?

Dietary modification and supplementation

In patients who can tolerate an oral diet, dietary modifications may be made in order to facilitate the provision of essential nutrients in a well-tolerated form. Modifications may include adjusting the consistency of foods, energy value of foods, types of nutrients consumed, and number and frequency of meals.8 Commercial meal replacement beverages are widely used to support a standard oral diet, but there is no data to support their routine use.7

Enteral nutrition

Enteral nutrition (EN) is the method of choice for administering nutrition support. Contraindications to enteral feeding include diffuse peritonitis, intestinal obstruction, and gastrointestinal ischemia.9 The potential advantages of EN over parenteral nutrition (PN) include decreased infection rate, decreased total complications, and shorter length of stay, but there has been no observed difference in mortality. EN is also suggested to have nonnutritional benefits related to providing luminal nutrients – these include maintaining gut integrity, beneficial immune responses, and favorable metabolic responses that help maintain euglycemia and enhance more physiologic fuel utilization.4

Enteral feeding can be administered through the following routes of access:

- Nasogastric tubes: A nasogastric or orogastric tube with radiologic confirmation of positioning is the first line of enteral access. Gastric feeding is preferred because it is well tolerated in the majority of patients, is more physiological, requires a lower level of expertise, and minimizes any delay in initiation of feeding.

- Postpyloric tubes: Postpyloric feeding tubes are indicated if gastric feeding is poorly tolerated or if the patient is at high risk for aspiration because jejunal feedings decrease the incidence of reflux, regurgitation, and aspiration.

- Percutaneous access: When long-term enteral access is required – that is, for greater than 4 weeks – a percutaneous enteral access device should be placed. Prolonged use of a nasoenteric tube may be associated with erosion of the nares and an increase in the incidence of aspiration pneumonia, sinusitis, and esophageal ulceration or stricture. Patients who have had a stroke are the most likely to benefit from percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy placement, as 40% of patients can have continued dysphagia as long as 1 year after.4,10 Absolute contraindications for PEG placement include serious coagulation disorders (international normalized ratio greater than 1.5; fewer than 50,000 platelets/mcL), sepsis, abdominal wall infections, marked peritoneal carcinomatosis, peritonitis, severe gastroparesis, gastric outlet obstruction, or a history of total gastrectomy. Risks often outweigh benefits in patients who have cirrhosis with ascites, patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis, and patients who have portal hypertension with gastric varices, but PEG can be considered on a case-by-case basis.11

Parenteral nutrition

Parenteral nutrition is reserved for patients in whom enteral feeding is contraindicated or who fail to meet their nutritional needs with enteral feedings. If EN is not feasible, then parenteral nutrition should be initiated as soon as possible in patients who had high nutritional risk on admission. Otherwise, PN should not be initiated during the first week of hospitalization because there is evidence to suggest net harm when initiated early. Supplemental PN may be considered for patients already on EN who are unable to meet more than 60% of their energy and protein requirements by the enteral route alone, but again, this should only be considered after 7-10 days on EN. PN is generally stopped when the patients achieve more than 60% of their energy and protein goals from EN.4

How should patients be monitored while receiving nutritional support?

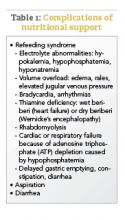

If a patient is severely malnourished and refeeding is initiated, serious complications can occur, which are summarized in Table 1; these complications can include severe electrolyte disorders, fluid shifts, and even death.12 Refeeding syndrome occurs in the first few days of initiating a diet in severely malnourished patients, and its severity is directly related to the severity of malnutrition prior to refeeding. The National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence created criteria to identify patients at risk for refeeding syndrome; these criteria include having a BMI less than 18.5 kg/m2; unintentional weight loss of greater than 10% in the previous 3-6 months; little or no nutritional intake for more than 5 days; low levels of potassium, phosphorus, or magnesium before refeeding; and a history of alcohol misuse or taking certain drugs, such as insulin, chemotherapy, antacids, or diuretics.9

Aspiration is a risk with enteral feeding – the risk factors include being older than 70 years, altered mental status, supine position, and bolus rather than continuous infusion.4 Postpyloric feeding may reduce the risk of aspiration. Expert consensus suggests elevating the head of the bed by 30°-40° for all intubated patients receiving EN, as well as administering chlorhexidine mouthwash twice daily.6

Diarrhea is very common in patients receiving EN. After evaluating for other etiologies of diarrhea, tube feeding–associated diarrhea may be managed first by using a fiber-containing formulation. Fiber should be avoided in patients at risk for bowel ischemia or severe dysmotility. If diarrhea persists despite fiber, small peptide formulations, also known as elemental tube feeds, may be used.4,6

Gastric residual volume (GRV) is commonly monitored in patients receiving enteral nutrition. However, the American College of Gastroenterology does not recommend using GRVs to monitor EN feeding because it is a poor marker of clinically meaningful variables, such as gastric emptying, risk of aspiration, and risk of poor outcomes, and increases the risk of tube clogging and inadequate delivery of EN. If GRVs are being monitored, tube feedings should not be withheld because of high GRVs when there are no other signs of intolerance.4 Nausea may be managed by changing a patient from bolus to continuous feedings or by adding promotility agents such as metoclopramide or erythromycin.6

Special considerations in common conditions treated by hospitalists

The principles outlined above are general guidelines that are applicable to most patients requiring nutrition support. We have highlighted special considerations for common conditions in hospitalized patients who require nutritional support below.

Critical Illness

- Defer enteral nutrition until patient is fully resuscitated and hemodynamically stable.

- Severely malnourished or high nutritional-risk patients should be advanced toward goals as quickly as can be tolerated over 24-48 hours.

- Patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome or acute lung injury, or those expected to require mechanical ventilation for more than 72 hours, should receive trophic feeds or full nutrition by enteral route.6

Pancreatitis

- Oral feeding should be attempted as soon as abdominal pain is decreasing and inflammatory markers are improving.13

- A regular solid, low-fat diet should be initiated, rather than slowly advancing from a clear liquid diet.13

- In severe acute pancreatitis, initiation of enteral nutrition within 48 hours of presentation is associated with improved outcomes.13

- There is no difference in outcomes between gastric and postpyloric feeding.14