User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Student Hospitalist Scholars: First experiences with clinical research

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

The work on my summer project is moving along. Right now, I am collecting data from patients who had clinical deterioration events and unplanned transfers to the PICU in Cincinnati Children’s Hospital over the past year or so.

My mentor has been very helpful in this process by setting up regular meetings with me and keeping communications open. He has provided me with some data from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital that identifies emergency transfer cases, as well as clinical deterioration cases. This saves me a significant amount of time and decreases the potential for errors in the data, because I don’t have to go back and decide which cases were emergency transfers on my own. We are discussing some of the exclusion criteria for the study at this point as well.

I’m enjoying this project, as it is one of my first experiences with clinical research. In addition to the research experience, I am also learning a good amount of medicine as I learn about the care given to these complex patients.

Farah Hussain is a 2nd-year medical student at University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and student researcher at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Her research interests involve bettering patient care to vulnerable populations.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

The work on my summer project is moving along. Right now, I am collecting data from patients who had clinical deterioration events and unplanned transfers to the PICU in Cincinnati Children’s Hospital over the past year or so.

My mentor has been very helpful in this process by setting up regular meetings with me and keeping communications open. He has provided me with some data from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital that identifies emergency transfer cases, as well as clinical deterioration cases. This saves me a significant amount of time and decreases the potential for errors in the data, because I don’t have to go back and decide which cases were emergency transfers on my own. We are discussing some of the exclusion criteria for the study at this point as well.

I’m enjoying this project, as it is one of my first experiences with clinical research. In addition to the research experience, I am also learning a good amount of medicine as I learn about the care given to these complex patients.

Farah Hussain is a 2nd-year medical student at University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and student researcher at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Her research interests involve bettering patient care to vulnerable populations.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

The work on my summer project is moving along. Right now, I am collecting data from patients who had clinical deterioration events and unplanned transfers to the PICU in Cincinnati Children’s Hospital over the past year or so.

My mentor has been very helpful in this process by setting up regular meetings with me and keeping communications open. He has provided me with some data from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital that identifies emergency transfer cases, as well as clinical deterioration cases. This saves me a significant amount of time and decreases the potential for errors in the data, because I don’t have to go back and decide which cases were emergency transfers on my own. We are discussing some of the exclusion criteria for the study at this point as well.

I’m enjoying this project, as it is one of my first experiences with clinical research. In addition to the research experience, I am also learning a good amount of medicine as I learn about the care given to these complex patients.

Farah Hussain is a 2nd-year medical student at University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and student researcher at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Her research interests involve bettering patient care to vulnerable populations.

A passion for education: Lonika Sood, MD

On top of her role as a hospitalist at the Aurora BayCare Medical Center in Green Bay, Wis., Lonika Sood, MD, FACP, is currently a candidate for a Masters in health professions education.

From her earliest training to the present day, she has maintained her passion for education, both as a student and an educator.

“I am a part of a community of practice, if you will, of other health professionals who do just this – medical education on a higher level.” Dr. Sood said. “Not only on the front lines of care, but also in designing curricula, undertaking medical education research, and holding leadership positions at medical schools and hospitals around the world.”

As one of the eight new members of The Hospitalist editorial advisory board, Dr. Sood is excited to use her role to help inform and to learn. She told us more about herself in a recent interview.

Q: How did you choose a career in medicine?

A: I grew up in India. I come from a family of doctors. When I was in high school, we found that we had close to 60 physicians in our family, and that number has grown quite a bit since then. At home, being around physicians, that was the language that I grew into. It was a big part of who I wanted to become when I grew up. The other part of it was that I’ve always wanted to help people and do something in one of the science fields, so this seemed like a natural choice for me.

Q: What made you choose hospital medicine?

A: I’ll be very honest – when I came to the United States for my residency, I wanted to become a subspecialist. I used to joke with my mentors in my residency program that every month I wanted to be a different subspecialist depending on which rotation I had or which physician really did a great job on the wards. After moving to Green Bay, Wis., I thought, “We’ll keep residency on hold for a couple of years.” Then I realized that I really liked medical education. I knew that I wanted to be a "specialist" in medical education, yet keep practicing internal medicine, which is something that I’ve always wanted to do. Being a hospitalist is like a marriage of those two passions.

Q: What about medical education draws you?

A: I think a large part of it was that my mother is a physician. My dad is in the merchant navy. In their midlife, they kind of fine-tuned their career paths by going into teaching, so both of them are educators, and very well accomplished in their own right. Growing up, that was a big part of what I saw myself becoming. I did not realize until later in my residency that it was my calling. Additionally, my experience of going into medicine and learning from good teachers is, in my mind, one of the things that really makes me comfortable, and happy being a doctor. I want to be able to leave that legacy for the coming generation.

Q: Tell us how your skills as a teacher help you when you’re working with your patients?

A: To give you an example, we have an adult internal medicine hospital, so we frequently have patients who come to the hospital for the first time. Some of our patients have not seen a physician in over 30 or 40 years. There may be many reasons for that, but they’re scared. They’re sick. They’re in a new environment. They are placing their trust in somebody else’s hands. As teachers and as doctors, it’s important for us to be compassionate, kind, and relatable to patients. We must also be able to explain to patients in their own words what is going on with their body, what might happen, and how can we help. We’re not telling patients what to do or forcing them to take our treatment recommendations, but we are helping them make informed choices. I think hospital medicine really is an incredibly powerful field that can help us relate to our patients.

Q: What is the best professional advice you have received in medicine?

A: I think the advice that I try to follow every day is to be humble. Try to be the best that you can be, yet stay humble, because there’s so much more that you can accomplish if you stay grounded. I think that has stuck with me. It’s come from my parents. It’s come from my mentors. And sometimes it comes from my patients, too.

Q: What is the worst advice you have received?

A: That’s a hard question, but an important one as well, I think. Sometimes there is a push – from society or your colleagues – to be as efficient as you can be, which is great, but we have to look at the downside of it. We sometimes don’t stop and think, or stop and be human. We’re kind of mechanical if data are all we follow.

Q: So where do you see yourself in the next 10 years?

A: That’s a question I try to answer daily, and I get a different answer each time. I think I do see myself continuing to provide clinical care for hospitalized patients. I see myself doing a little more in educational leadership, working with medical students and medical residents. I’m just completing my master’s in health professions education, so I’m excited to also start a career in medical education research.

Q: What’s the best book that you’ve read recently, and why was it the best?

A: Oh, well, it’s not a new book, and I’ve read this before, but I keep coming back to it. I don’t know if you’ve heard of Jim Corbett. He was a wildlife enthusiast in the early 20th century. He wrote a lot of books on man-eating tigers and leopards in India. My brother and I and my dad used to read these books growing up. That’s something that I’m going back to and rereading. There is a lot of rich description about Indian wildlife, and it’s something that brings back good memories.

On top of her role as a hospitalist at the Aurora BayCare Medical Center in Green Bay, Wis., Lonika Sood, MD, FACP, is currently a candidate for a Masters in health professions education.

From her earliest training to the present day, she has maintained her passion for education, both as a student and an educator.

“I am a part of a community of practice, if you will, of other health professionals who do just this – medical education on a higher level.” Dr. Sood said. “Not only on the front lines of care, but also in designing curricula, undertaking medical education research, and holding leadership positions at medical schools and hospitals around the world.”

As one of the eight new members of The Hospitalist editorial advisory board, Dr. Sood is excited to use her role to help inform and to learn. She told us more about herself in a recent interview.

Q: How did you choose a career in medicine?

A: I grew up in India. I come from a family of doctors. When I was in high school, we found that we had close to 60 physicians in our family, and that number has grown quite a bit since then. At home, being around physicians, that was the language that I grew into. It was a big part of who I wanted to become when I grew up. The other part of it was that I’ve always wanted to help people and do something in one of the science fields, so this seemed like a natural choice for me.

Q: What made you choose hospital medicine?

A: I’ll be very honest – when I came to the United States for my residency, I wanted to become a subspecialist. I used to joke with my mentors in my residency program that every month I wanted to be a different subspecialist depending on which rotation I had or which physician really did a great job on the wards. After moving to Green Bay, Wis., I thought, “We’ll keep residency on hold for a couple of years.” Then I realized that I really liked medical education. I knew that I wanted to be a "specialist" in medical education, yet keep practicing internal medicine, which is something that I’ve always wanted to do. Being a hospitalist is like a marriage of those two passions.

Q: What about medical education draws you?

A: I think a large part of it was that my mother is a physician. My dad is in the merchant navy. In their midlife, they kind of fine-tuned their career paths by going into teaching, so both of them are educators, and very well accomplished in their own right. Growing up, that was a big part of what I saw myself becoming. I did not realize until later in my residency that it was my calling. Additionally, my experience of going into medicine and learning from good teachers is, in my mind, one of the things that really makes me comfortable, and happy being a doctor. I want to be able to leave that legacy for the coming generation.

Q: Tell us how your skills as a teacher help you when you’re working with your patients?

A: To give you an example, we have an adult internal medicine hospital, so we frequently have patients who come to the hospital for the first time. Some of our patients have not seen a physician in over 30 or 40 years. There may be many reasons for that, but they’re scared. They’re sick. They’re in a new environment. They are placing their trust in somebody else’s hands. As teachers and as doctors, it’s important for us to be compassionate, kind, and relatable to patients. We must also be able to explain to patients in their own words what is going on with their body, what might happen, and how can we help. We’re not telling patients what to do or forcing them to take our treatment recommendations, but we are helping them make informed choices. I think hospital medicine really is an incredibly powerful field that can help us relate to our patients.

Q: What is the best professional advice you have received in medicine?

A: I think the advice that I try to follow every day is to be humble. Try to be the best that you can be, yet stay humble, because there’s so much more that you can accomplish if you stay grounded. I think that has stuck with me. It’s come from my parents. It’s come from my mentors. And sometimes it comes from my patients, too.

Q: What is the worst advice you have received?

A: That’s a hard question, but an important one as well, I think. Sometimes there is a push – from society or your colleagues – to be as efficient as you can be, which is great, but we have to look at the downside of it. We sometimes don’t stop and think, or stop and be human. We’re kind of mechanical if data are all we follow.

Q: So where do you see yourself in the next 10 years?

A: That’s a question I try to answer daily, and I get a different answer each time. I think I do see myself continuing to provide clinical care for hospitalized patients. I see myself doing a little more in educational leadership, working with medical students and medical residents. I’m just completing my master’s in health professions education, so I’m excited to also start a career in medical education research.

Q: What’s the best book that you’ve read recently, and why was it the best?

A: Oh, well, it’s not a new book, and I’ve read this before, but I keep coming back to it. I don’t know if you’ve heard of Jim Corbett. He was a wildlife enthusiast in the early 20th century. He wrote a lot of books on man-eating tigers and leopards in India. My brother and I and my dad used to read these books growing up. That’s something that I’m going back to and rereading. There is a lot of rich description about Indian wildlife, and it’s something that brings back good memories.

On top of her role as a hospitalist at the Aurora BayCare Medical Center in Green Bay, Wis., Lonika Sood, MD, FACP, is currently a candidate for a Masters in health professions education.

From her earliest training to the present day, she has maintained her passion for education, both as a student and an educator.

“I am a part of a community of practice, if you will, of other health professionals who do just this – medical education on a higher level.” Dr. Sood said. “Not only on the front lines of care, but also in designing curricula, undertaking medical education research, and holding leadership positions at medical schools and hospitals around the world.”

As one of the eight new members of The Hospitalist editorial advisory board, Dr. Sood is excited to use her role to help inform and to learn. She told us more about herself in a recent interview.

Q: How did you choose a career in medicine?

A: I grew up in India. I come from a family of doctors. When I was in high school, we found that we had close to 60 physicians in our family, and that number has grown quite a bit since then. At home, being around physicians, that was the language that I grew into. It was a big part of who I wanted to become when I grew up. The other part of it was that I’ve always wanted to help people and do something in one of the science fields, so this seemed like a natural choice for me.

Q: What made you choose hospital medicine?

A: I’ll be very honest – when I came to the United States for my residency, I wanted to become a subspecialist. I used to joke with my mentors in my residency program that every month I wanted to be a different subspecialist depending on which rotation I had or which physician really did a great job on the wards. After moving to Green Bay, Wis., I thought, “We’ll keep residency on hold for a couple of years.” Then I realized that I really liked medical education. I knew that I wanted to be a "specialist" in medical education, yet keep practicing internal medicine, which is something that I’ve always wanted to do. Being a hospitalist is like a marriage of those two passions.

Q: What about medical education draws you?

A: I think a large part of it was that my mother is a physician. My dad is in the merchant navy. In their midlife, they kind of fine-tuned their career paths by going into teaching, so both of them are educators, and very well accomplished in their own right. Growing up, that was a big part of what I saw myself becoming. I did not realize until later in my residency that it was my calling. Additionally, my experience of going into medicine and learning from good teachers is, in my mind, one of the things that really makes me comfortable, and happy being a doctor. I want to be able to leave that legacy for the coming generation.

Q: Tell us how your skills as a teacher help you when you’re working with your patients?

A: To give you an example, we have an adult internal medicine hospital, so we frequently have patients who come to the hospital for the first time. Some of our patients have not seen a physician in over 30 or 40 years. There may be many reasons for that, but they’re scared. They’re sick. They’re in a new environment. They are placing their trust in somebody else’s hands. As teachers and as doctors, it’s important for us to be compassionate, kind, and relatable to patients. We must also be able to explain to patients in their own words what is going on with their body, what might happen, and how can we help. We’re not telling patients what to do or forcing them to take our treatment recommendations, but we are helping them make informed choices. I think hospital medicine really is an incredibly powerful field that can help us relate to our patients.

Q: What is the best professional advice you have received in medicine?

A: I think the advice that I try to follow every day is to be humble. Try to be the best that you can be, yet stay humble, because there’s so much more that you can accomplish if you stay grounded. I think that has stuck with me. It’s come from my parents. It’s come from my mentors. And sometimes it comes from my patients, too.

Q: What is the worst advice you have received?

A: That’s a hard question, but an important one as well, I think. Sometimes there is a push – from society or your colleagues – to be as efficient as you can be, which is great, but we have to look at the downside of it. We sometimes don’t stop and think, or stop and be human. We’re kind of mechanical if data are all we follow.

Q: So where do you see yourself in the next 10 years?

A: That’s a question I try to answer daily, and I get a different answer each time. I think I do see myself continuing to provide clinical care for hospitalized patients. I see myself doing a little more in educational leadership, working with medical students and medical residents. I’m just completing my master’s in health professions education, so I’m excited to also start a career in medical education research.

Q: What’s the best book that you’ve read recently, and why was it the best?

A: Oh, well, it’s not a new book, and I’ve read this before, but I keep coming back to it. I don’t know if you’ve heard of Jim Corbett. He was a wildlife enthusiast in the early 20th century. He wrote a lot of books on man-eating tigers and leopards in India. My brother and I and my dad used to read these books growing up. That’s something that I’m going back to and rereading. There is a lot of rich description about Indian wildlife, and it’s something that brings back good memories.

Here’s what’s trending at SHM - Aug. 2017

Awards of Excellence nominations now open

SHM’s prestigious Awards of Excellence recognize exceptional achievements in the field of hospital medicine. Nominate a colleague (or yourself) for exemplary contributions that deserve acknowledgment and respect in the following categories:

- Excellence in Research

- Management Excellence in Hospital Medicine

- Outstanding Service in Hospital Medicine

- Excellence in Teaching

- Clinical Excellence for Physicians

- Clinical Excellence for Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants

- Excellence in Humanitarian Services

- Excellence in Teamwork

Awards of Excellence nominations are due on October 6, 2017. Nominate yourself or a colleague today at hospitalmedicine.org/awards.

Academic Hospitalist Academy

The eighth annual Academic Hospitalist Academy (AHA) is filling up quickly! For the second year in a row, it will be held at the beautiful Lakeway Resort and Spa in Austin, Texas, Sept. 25-28, 2017.

The principal goals of the Academy are to develop junior academic hospitalists as the premier teachers and educational leaders at their institutions, help academic hospitalists develop scholarly work and increase scholarly output, and enhance awareness of the value of quality improvement and patient safety work.

Each full day of learning is facilitated by leading clinician-educators, hospitalist-researchers, and clinical administrators in a 1:10 faculty-to-student ratio. Don’t miss out on this unique, hands-on experience. Visit academichospitalist.org to learn more.

Strengthen your skills with our Practice Administrator Mentor Program

New to practice administration? SHM invites you to join the Practice Administrators’ Committee Mentor/Mentee Program.

This structured program is geared toward hospitalist administrators seeking to strengthen their knowledge and skills. The program helps you develop relationships and serves as an outlet for you to pose questions to or share ideas with a seasoned administrator. There are two different ways you can participate. If you are a less experienced administrator looking for a mentor, or if you have more experience and are looking to be paired with a peer to learn from each other, you can choose the buddy system.

Learn more and submit your application at hospitalmedicine.org/pamentor. (The program is free to members only.)

Not a member? Join today at hospitalmedicine.org/join.

Distinguish yourself as a Class of 2018 Fellow in Hospital Medicine

SHM’s Fellows designation is a prestigious way to differentiate yourself in the rapidly growing profession of hospital medicine. There are currently over 2,000 hospitalists who have earned the Fellow in Hospital Medicine (FHM) or Senior Fellow in Hospital Medicine (SFHM) designation by demonstrating the core values of leadership, teamwork, and quality improvement.

If you applied for early decision on or before Sept. 15, you will receive a response on or before Oct. 27, 2017. The regular decision application will remain open through Nov. 30, with a decision on or before Dec. 31, 2017. Apply now and learn how you can join other hospitalists who have earned this exclusive designation and recognition at hospitalmedicine.org/fellows.

HM17 On Demand

Did you miss Hospital Medicine 2017? Are you looking to earn both CME credit and MOC points?

HM17 On Demand is a collection of the most popular tracks from Hospital Medicine 2017 (HM17), SHM’s annual meeting. HM17 is the premier educational event for health care professionals who specialize in hospital medicine.

HM17 On Demand gives you access to over 80 online audio and slide recordings from the hottest tracks, including clinical updates, rapid fire, pediatrics, comanagement, quality, and high-value care. Additionally, you can earn up to 70 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits and up to 30 ABIM MOC credits. HM17 attendees can also earn additional credits on sessions they missed out on.

HM17 On Demand is easily accessed through SHM’s Learning Portal. Visit shmlearningportal.org/hm17-demand to get your copy.

Brett Radler is marketing communications manager at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Awards of Excellence nominations now open

SHM’s prestigious Awards of Excellence recognize exceptional achievements in the field of hospital medicine. Nominate a colleague (or yourself) for exemplary contributions that deserve acknowledgment and respect in the following categories:

- Excellence in Research

- Management Excellence in Hospital Medicine

- Outstanding Service in Hospital Medicine

- Excellence in Teaching

- Clinical Excellence for Physicians

- Clinical Excellence for Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants

- Excellence in Humanitarian Services

- Excellence in Teamwork

Awards of Excellence nominations are due on October 6, 2017. Nominate yourself or a colleague today at hospitalmedicine.org/awards.

Academic Hospitalist Academy

The eighth annual Academic Hospitalist Academy (AHA) is filling up quickly! For the second year in a row, it will be held at the beautiful Lakeway Resort and Spa in Austin, Texas, Sept. 25-28, 2017.

The principal goals of the Academy are to develop junior academic hospitalists as the premier teachers and educational leaders at their institutions, help academic hospitalists develop scholarly work and increase scholarly output, and enhance awareness of the value of quality improvement and patient safety work.

Each full day of learning is facilitated by leading clinician-educators, hospitalist-researchers, and clinical administrators in a 1:10 faculty-to-student ratio. Don’t miss out on this unique, hands-on experience. Visit academichospitalist.org to learn more.

Strengthen your skills with our Practice Administrator Mentor Program

New to practice administration? SHM invites you to join the Practice Administrators’ Committee Mentor/Mentee Program.

This structured program is geared toward hospitalist administrators seeking to strengthen their knowledge and skills. The program helps you develop relationships and serves as an outlet for you to pose questions to or share ideas with a seasoned administrator. There are two different ways you can participate. If you are a less experienced administrator looking for a mentor, or if you have more experience and are looking to be paired with a peer to learn from each other, you can choose the buddy system.

Learn more and submit your application at hospitalmedicine.org/pamentor. (The program is free to members only.)

Not a member? Join today at hospitalmedicine.org/join.

Distinguish yourself as a Class of 2018 Fellow in Hospital Medicine

SHM’s Fellows designation is a prestigious way to differentiate yourself in the rapidly growing profession of hospital medicine. There are currently over 2,000 hospitalists who have earned the Fellow in Hospital Medicine (FHM) or Senior Fellow in Hospital Medicine (SFHM) designation by demonstrating the core values of leadership, teamwork, and quality improvement.

If you applied for early decision on or before Sept. 15, you will receive a response on or before Oct. 27, 2017. The regular decision application will remain open through Nov. 30, with a decision on or before Dec. 31, 2017. Apply now and learn how you can join other hospitalists who have earned this exclusive designation and recognition at hospitalmedicine.org/fellows.

HM17 On Demand

Did you miss Hospital Medicine 2017? Are you looking to earn both CME credit and MOC points?

HM17 On Demand is a collection of the most popular tracks from Hospital Medicine 2017 (HM17), SHM’s annual meeting. HM17 is the premier educational event for health care professionals who specialize in hospital medicine.

HM17 On Demand gives you access to over 80 online audio and slide recordings from the hottest tracks, including clinical updates, rapid fire, pediatrics, comanagement, quality, and high-value care. Additionally, you can earn up to 70 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits and up to 30 ABIM MOC credits. HM17 attendees can also earn additional credits on sessions they missed out on.

HM17 On Demand is easily accessed through SHM’s Learning Portal. Visit shmlearningportal.org/hm17-demand to get your copy.

Brett Radler is marketing communications manager at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Awards of Excellence nominations now open

SHM’s prestigious Awards of Excellence recognize exceptional achievements in the field of hospital medicine. Nominate a colleague (or yourself) for exemplary contributions that deserve acknowledgment and respect in the following categories:

- Excellence in Research

- Management Excellence in Hospital Medicine

- Outstanding Service in Hospital Medicine

- Excellence in Teaching

- Clinical Excellence for Physicians

- Clinical Excellence for Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants

- Excellence in Humanitarian Services

- Excellence in Teamwork

Awards of Excellence nominations are due on October 6, 2017. Nominate yourself or a colleague today at hospitalmedicine.org/awards.

Academic Hospitalist Academy

The eighth annual Academic Hospitalist Academy (AHA) is filling up quickly! For the second year in a row, it will be held at the beautiful Lakeway Resort and Spa in Austin, Texas, Sept. 25-28, 2017.

The principal goals of the Academy are to develop junior academic hospitalists as the premier teachers and educational leaders at their institutions, help academic hospitalists develop scholarly work and increase scholarly output, and enhance awareness of the value of quality improvement and patient safety work.

Each full day of learning is facilitated by leading clinician-educators, hospitalist-researchers, and clinical administrators in a 1:10 faculty-to-student ratio. Don’t miss out on this unique, hands-on experience. Visit academichospitalist.org to learn more.

Strengthen your skills with our Practice Administrator Mentor Program

New to practice administration? SHM invites you to join the Practice Administrators’ Committee Mentor/Mentee Program.

This structured program is geared toward hospitalist administrators seeking to strengthen their knowledge and skills. The program helps you develop relationships and serves as an outlet for you to pose questions to or share ideas with a seasoned administrator. There are two different ways you can participate. If you are a less experienced administrator looking for a mentor, or if you have more experience and are looking to be paired with a peer to learn from each other, you can choose the buddy system.

Learn more and submit your application at hospitalmedicine.org/pamentor. (The program is free to members only.)

Not a member? Join today at hospitalmedicine.org/join.

Distinguish yourself as a Class of 2018 Fellow in Hospital Medicine

SHM’s Fellows designation is a prestigious way to differentiate yourself in the rapidly growing profession of hospital medicine. There are currently over 2,000 hospitalists who have earned the Fellow in Hospital Medicine (FHM) or Senior Fellow in Hospital Medicine (SFHM) designation by demonstrating the core values of leadership, teamwork, and quality improvement.

If you applied for early decision on or before Sept. 15, you will receive a response on or before Oct. 27, 2017. The regular decision application will remain open through Nov. 30, with a decision on or before Dec. 31, 2017. Apply now and learn how you can join other hospitalists who have earned this exclusive designation and recognition at hospitalmedicine.org/fellows.

HM17 On Demand

Did you miss Hospital Medicine 2017? Are you looking to earn both CME credit and MOC points?

HM17 On Demand is a collection of the most popular tracks from Hospital Medicine 2017 (HM17), SHM’s annual meeting. HM17 is the premier educational event for health care professionals who specialize in hospital medicine.

HM17 On Demand gives you access to over 80 online audio and slide recordings from the hottest tracks, including clinical updates, rapid fire, pediatrics, comanagement, quality, and high-value care. Additionally, you can earn up to 70 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits and up to 30 ABIM MOC credits. HM17 attendees can also earn additional credits on sessions they missed out on.

HM17 On Demand is easily accessed through SHM’s Learning Portal. Visit shmlearningportal.org/hm17-demand to get your copy.

Brett Radler is marketing communications manager at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

How to manage submassive pulmonary embolism

The case

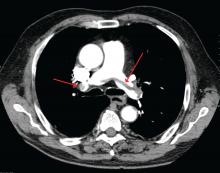

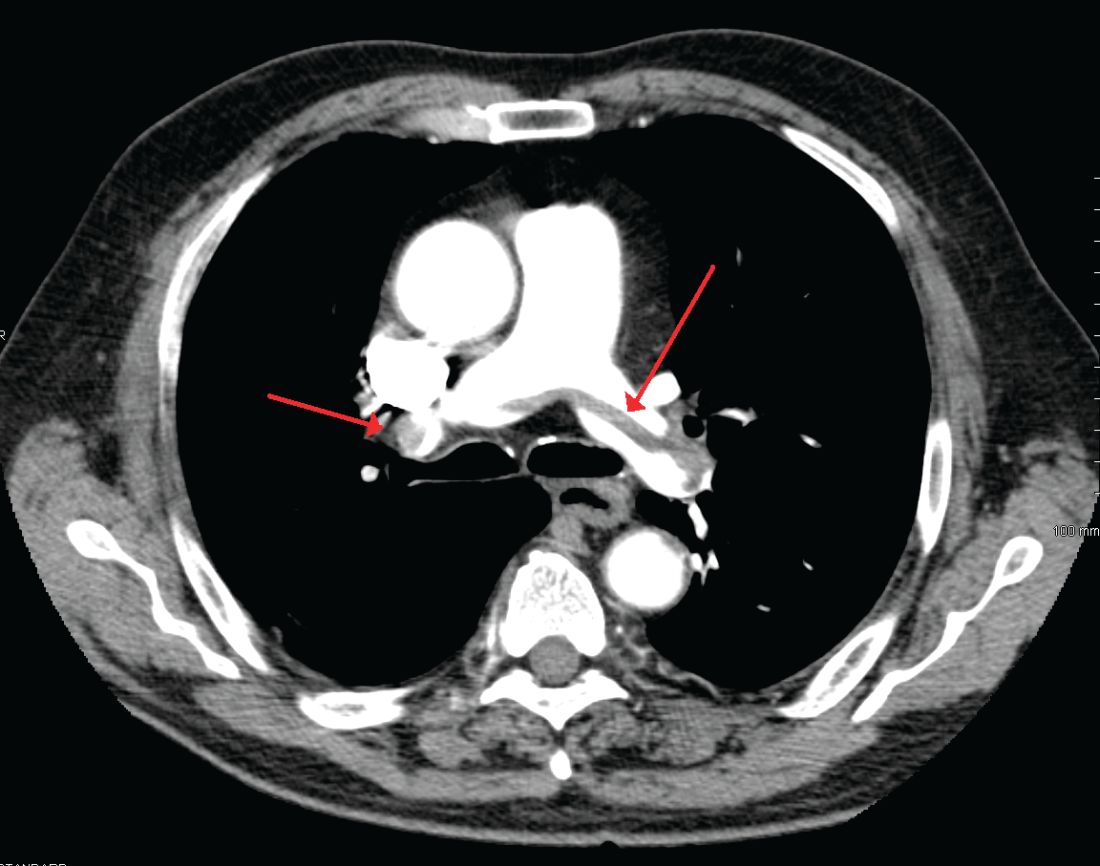

A 49-year-old morbidly obese woman presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath and abdominal distention. On presentation, her blood pressure was 100/60 mm Hg with a heart rate of 110, respiratory rate of 24, and a pulse oximetric saturation (SpO2) of 86% on room air. Troponin T was elevated at 0.3 ng/mL. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with intravenous contrast showed saddle pulmonary embolism (PE) with dilated right ventricle (RV). CT abdomen/pelvis revealed a very large uterine mass with diffuse lymphadenopathy.

Heparin infusion was started promptly. Echocardiogram demonstrated RV strain. Findings on duplex ultrasound of the lower extremities were consistent with acute deep vein thromboses (DVT) involving the left common femoral vein and the right popliteal vein. Biopsy of a supraclavicular lymph node showed high grade undifferentiated carcinoma most likely of uterine origin.

Clinical questions

What, if any, therapeutic options should be considered beyond standard systemic anticoagulation? Is there a role for:

1. Systemic thrombolysis?

2. Catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT)?

3. Inferior vena cava (IVC) filter placement?

What is the appropriate management of “submassive” PE?

In the case of massive PE, where the thrombus is located in the central pulmonary vasculature and associated with hypotension due to impaired cardiac output, systemic thrombolysis, embolectomy, and CDT are indicated as potentially life-saving measures. However, the evidence is less clear when the PE is large and has led to RV strain, but without overt hemodynamic instability. This is commonly known as an intermediate risk or “submassive” PE. Submassive PE based on American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines is:1

An acute PE without systemic hypotension (systolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg) but with either RV dysfunction or myocardial necrosis. RV dysfunction is defined by the presence of at least one of these following:

• RV dilation (apical 4-chamber RV diameter divided by LV diameter greater than 0.9) or RV systolic dysfunction on echocardiography;

• RV dilation on CT, elevation of BNP (greater than 90 pg/mL), elevation of N-terminal pro-BNP (greater than 500 pg/mL);

• Electrocardiographic changes (new complete or incomplete right bundle branch block, anteroseptal ST elevation or depression, or anteroseptal T-wave inversion).

Myocardial necrosis is defined as elevated troponin I (greater than 0.4 ng/mL) or elevated troponin T (greater than 0.1 ng/mL).

Why is submassive PE of clinical significance?

In 1999, analysis of the International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry (ICOPER) revealed that RV dysfunction in PE patients was associated with a near doubling of the 3-month mortality risk (hazard ratio 2.0, 1.3-2.9).2 Given this increased risk, one could draw the logical conclusion that we need to treat submassive PE more aggressively than PE without RV strain. But will this necessarily result in a better outcome for the patient given the 3% risk of intracranial hemorrhage associated with thrombolytic therapy?

In the clinical scenario above, the patient did meet the definition of submassive PE. While the patient did not experience systemic hypotension, she did have RV dilation on CT, RV systolic dysfunction on echo as well as an elevated Troponin T level. In addition to starting anticoagulant therapy, what more should be done to increase her probability of a good outcome?

The AHA recommends that systemic thrombolysis and CDT be considered for patients with acute submassive PE if they have clinical evidence of adverse prognosis, including worsening respiratory failure, severe RV dysfunction, or major myocardial necrosis and low risk of bleeding complications (Class IIB; Level of Evidence C).1

The 2016 American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) guidelines update3 recommends systemically administered thrombolytic therapy over no therapy in selected patients with acute PE who deteriorate after starting anticoagulant therapy but have yet to develop hypotension and who have a low bleeding risk (Grade 2C recommendation).

Systemic thrombolysis

Systemic thrombolysis is administered as an intravenous thrombolytic infusion delivered over a period of time. The Food and Drug Administration–approved thrombolytic drugs currently include tissue plasminogen activator (tPA)/alteplase, streptokinase and urokinase.

Efficacy of low dose thrombolysis was studied in MOPETT 2013,5 a single-center, prospective, randomized, open label study, in which 126 participants found to have submassive PE based on symptoms and CT angiographic or ventilation/perfusion scan data received either 50 mg tPA plus heparin or heparin anticoagulation alone. The composite endpoint of pulmonary hypertension and recurrent PE at 28 months was 16% in the tPA group compared to 63% in the control group (P less than .001). Systemic thrombolysis was associated with lower risk of pulmonary hypertension and recurrent PE, although no mortality benefit was seen in this small study.

In the randomized, double-blind PEITHO trial (n = 1,006) of 20146 comparing tenecteplase plus heparin versus heparin in the submassive PE patients, the primary outcomes of death and hemodynamic decompensation occurred in 2.6% of the tenecteplase group, compared to 5.6% in the placebo group (P = .02). Thrombolytic therapy was associated with 2% rate of hemorrhagic stroke, whereas hemorrhagic stroke in the placebo group was 0.2% (P = .03). In this case, systemic thrombolysis was associated with a 3% lower risk of death and hemodynamic instability, but also a 1.8% increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke.

Catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT)

CDT was originally developed to treat arterial, dialysis graft and deep vein thromboses, but is now approved by the FDA for the treatment of acute submassive or massive PE.

A wire is passed through the embolus and a multihole infusion catheter is placed, through which a thrombolytic drug is infused over 12-24 hours. The direct delivery of the drug into the thrombus is thought to be as effective as systemic therapy but with a lower risk of bleeding. If more rapid thrombus removal is indicated due to large clot burden and hemodynamic instability, mechanical therapies, such as fragmentation and aspiration, can be used as an adjunct to CDT. However, these mechanical techniques carry the risk of pulmonary artery injury, and therefore should only be used as a last resort. An ultrasound-emitting wire can be added to the multihole infusion catheter to expedite thrombolysis by ultrasonically disrupting the thrombus, a technique known as ultrasound-enhanced thrombolysis (EKOS).7,10

The ULTIMA 2014 trial,8 a small, randomized, open-label study of Ultrasound-Assisted Catheter Directed Thrombolysis (USAT, the term can be used interchangeably with EKOS) versus heparin anticoagulation alone in 59 patients, was designed to study if the former strategy was better at improving the primary outcome measure of RV/LV ratio in submassive PE patients. The mean reduction in RV/LV ratio was 0.30 +/– 0.20 in the USAT group compared to 0.03 +/– 0.16 in the heparin group (P less than .001). However, no significant difference in mortality or bleeding was observed in the groups at 90-day follow up.

The PERFECT 2015 Trial,9 a multicenter registry-based study, prospectively enrolled 101 patients who received CDT as first-line therapy for massive and submassive PE. Among patients with submassive PE, 97.3% were found to have “clinical success” with this treatment, defined as stabilization of hemodynamics, improvement in pulmonary hypertension and right heart strain, and survival to hospital discharge. There was no major bleeding or intracranial hemorrhage. Subgroup analyses in this study comparing USAT against standard CDT did not reveal significant difference in average pulmonary pressure changes, average thrombolytic doses, or average infusion times.

A prospective single-arm multicenter trial, SEATTLE II 2015,10 evaluated the efficacy of EKOS in a sample of 159 patients. Patients with both massive and submassive PE received approximately 24 mg tPA infused via a catheter over 12-24 hours. The primary efficacy outcome was the chest CT-measured RV/LV ratio decrease from the baseline compared to 48 hours post procedure. The pre- and postprocedure ratio was 1.55 versus 1.13 respectively (P less than .001), indicating that EKOS decreased RV dilation. No intracranial hemorrhage was observed and the investigators did not comment on long-term outcomes such as mortality or quality of life. The study was limited by the lack of a comparison group, such as anticoagulation with heparin as monotherapy, or systemic thrombolysis or standard CDT.

Treatment of submassive PE varies between different institutions. There simply are not adequate data comparing low dose systemic thrombolysis, CDT, EKOS, and standard heparin anticoagulation to make firm recommendations. Some investigators feel low-dose systemic thrombolysis is probably as good as the expensive catheter-based thrombolytic therapies.11,12 Low-dose thrombolytic therapy can be followed by use of oral direct factor Xa inhibitors for maintenance of antithrombotic activity.13

Bottom line

In our institution, the interventional radiology team screens patients who meet criteria for submassive PE on a case-by-case basis. We use pulmonary angiographic data (nature and extent of the thrombus), clinical stability, and analysis of other comorbid conditions to decide the best treatment modality for an individual patient. Our team prefers EKOS for submassive PE patients as well as for massive PE patients and as a rescue procedure for patients who have failed systemic thrombolysis.

Until more data are available to support firm guidelines, we feel establishing multidisciplinary teams composed of interventional radiologists, intensivists, cardiologists, and vascular surgeons is prudent to make individualized decisions and to achieve the best outcomes for our patients.14

IVC filter

Since the patient in this case already has a submassive PE, can she tolerate additional clot burden should her remaining DVT embolize again? Is there a role for IVC filter?

The implantation of IVC filters has increased significantly in the past 30 years, without quality evidence justifying their use.15

The 2016 Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report states clearly: In patients with acute DVT of the leg or PE who are treated with anticoagulants, the use of an IVC filter is not recommended (Grade 1B).3 This recommendation is based on findings of the Prevention du Risque d’Embolie Pulmonaire par Interruption Cave (PREPIC) randomized trial,16 and the recently published PREPIC 2 randomized trial,17 both showing that in anticoagulated patients with PE and DVT, concurrent placement of an IVC filter for 3 months did not reduce recurrent PE, including fatal PE.

CHEST guidelines state that an IVC filter should not be routinely placed as an adjunct in patients with PE and DVT. However, what about in the subgroup of patients with submassive or massive PE in whom another PE would be catastrophic? Clinical data are lacking in this area.

Deshpande et al. reported on a series of six patients with massive PE and cardiopulmonary instability; patients all received an IVC filter with anticoagulation. The short-term outcome was excellent, but long-term follow-up was not done.18 Kucher and colleagues reported that from the ICOPER in 2006, out of the 108 massive PE patients with systolic arterial pressure under 90 mm Hg, 11 patients received adjunctive IVC filter placement. None of these 11 patients developed recurrent PE in 90 days and 10 of them survived at least 90 days; IVC filter placement was associated with a reduction in 90-day mortality. In this study, the placement of an IVC filter was entirely decided by the physicians at different sites.19 In a 2012 study examining case fatality rates in 3,770 patients with acute PE who received pulmonary embolectomy, the data showed that in both unstable and stable patients, case fatality rates were lower in those who received an IVC filter.20

Although the above data are favorable for adjunctive IVC filter placement in massive PE patients, at least in short-term outcomes, the small size and lack of randomization preclude establishment of evidence-based guidelines. The 2016 CHEST guidelines point out that as it is uncertain if there is benefit to place an IVC filter adjunctively in anticoagulated patients with severe PE, in this specific subgroup of patients, the recommendation against insertion of an IVC filter in patients with acute PE who are anticoagulated may not apply.3

Bottom line

There is no evidence-based guideline as to whether IVC filters should be placed adjunctively in patients with submassive or massive PE; however, based on expert consensus, it may be appropriate to place an IVC filter as an adjunct to anticoagulation in patients with severe PE. The decision should be individualized based on each patient’s characteristics, preferences, and institutional expertise.

In our case, in hope of preventing further embolic burden, the patient received an IVC filter the day after presentation. Despite the initiation of anticoagulation with heparin, she remained tachycardic and tachypneic, prompting referral for CDT. The interventional radiology team did not feel that she was a good candidate, given her persistent vaginal bleeding and widely metastatic uterine carcinoma. She was switched to therapeutic enoxaparin after no further invasive intervention was deemed appropriate. Her respiratory status did not improve and bilevel positive airway pressure was initiated. Taking into consideration the terminal nature of her cancer, she ultimately elected to pursue comfort care and died shortly afterward.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Benjamin A. Hohmuth, MD, A. Joseph Layon, MD, and Luis L. Nadal, MD, for their review of the article and invaluable feedback.

Dr. Wenqian Wang, Dr. Vedamurthy, and Dr. Wang are based in the department of hospital medicine at The Medicine Institute, Geisinger Health System, Danville, Penn. Contact Dr. Wenqian Wang at [email protected].

Key Points

• Use pulmonary angiographic data, clinical stability, and analysis of other comorbid conditions to decide the best treatment modality.

• Our team prefers ultrasound-enhanced thrombolysis (EKOS) for submassive PE patients, massive PE patients, and as a rescue procedure for patients who fail systemic thrombolysis.

• Establishing multidisciplinary teams composed of interventional radiologists, intensivists, cardiologists, and vascular surgeons is prudent to make individualized decisions.

• It may be appropriate to place an IVC filter as an adjunct to anticoagulation in patients with severe PE.

References

1. Jaff MR, McMurtry MS, Archer SL, et al. Management of massive and submassive pulmonary embolism, iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis, and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:1788-1830.

2. Goldhaber SZ, Visani L, De Rosa M. Acute pulmonary embolism: clinical outcomes in the International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry (ICOPER). Lancet. 1999;353:1386-9.

3. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2016;149:315-52.

4. Konstantinides S, Geibel A, Heusel G, Heinrich F, Kasper W. Management Strategies and Prognosis of Pulmonary Embolism-3 Trial Investigators. Heparin plus alteplase compared with heparin alone in patients with submassive pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1143-50.

5. Sharifi M, Bay C, Skrocki L, Rahimi F, Mehdipour M, “MOPETT” Investigators. Moderate pulmonary embolism treated with thrombolysis (from the “MOPETT” Trial). Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:273-7.

6. Meyer G, Vicaut E, Danays T, et al. Fibrinolysis for patients with intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1402-11.

7. Kuo WT. Endovascular therapy for acute pulmonary embolism. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2012;23:167-79. e164

8. Kucher N, Boekstegers P, Muller OJ, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of ultrasound-assisted catheter-directed thrombolysis for acute intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 2014;129:479-86.

9. Kuo WT, Banerjee A, Kim PS, et al. Pulmonary Embolism Response to Fragmentation, Embolectomy, and Catheter Thrombolysis (PERFECT): Initial Results From a Prospective Multicenter Registry. Chest. 2015;148:667-73.

10. Piazza G, Hohlfelder B, Jaff MR, et al. A Prospective, Single-Arm, Multicenter Trial of Ultrasound-Facilitated, Catheter-Directed, Low-Dose Fibrinolysis for Acute Massive and Submassive Pulmonary Embolism: The SEATTLE II Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:1382-92.

11. Sharifi M. Systemic Full Dose, Half Dose, and Catheter Directed Thrombolysis for Pulmonary Embolism. When to Use and How to Choose? Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2016;18:31.

12. Wang C, Zhai Z, Yang Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of low dose recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator for the treatment of acute pulmonary thromboembolism: a randomized, multicenter, controlled trial. Chest. 2010;137:254-62.

13. Sharifi M, Vajo Z, Freeman W, Bay C, Sharifi M, Schwartz F. Transforming and simplifying the treatment of pulmonary embolism: “safe dose” thrombolysis plus new oral anticoagulants. Lung. 2015;193:369-74.

14. Kabrhel C, Rosovsky R, Channick R, et al. A Multidisciplinary Pulmonary Embolism Response Team: Initial 30-Month Experience With a Novel Approach to Delivery of Care to Patients With Submassive and Massive Pulmonary Embolism. Chest. 2016;150:384-93.

15. Lessne ML, Sing RF. Counterpoint: Do the Benefits Outweigh the Risks for Most Patients Under Consideration for inferior vena cava filters? No. Chest. 2016; 150(6):1182-4.

16. The PREPIC Study Group. Eight-year follow-up of patients with permanent vena cava filters in the prevention of pulmonary embolism: the PREPIC (Prevention du Risque d’Embolie Pulmonaire par Interruption Cave) randomized study. Circulation. 2005;112(3):416-22.

17. Mismetti P, Laporte S, Pellerin O, et al. Effect of a retrievable inferior vena cava filter plus anticoagulation vs. anticoagulation alone on risk of recurrent pulmonary embolism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015. 313(16):1627-35.

18. Deshpande KS, Hatem C, Karwa M, et al. The use of inferior vena cava filter as a treatment modality for massive pulmonary embolism. A case series and review of pathophysiology. Respir Med. 2002.96(12):984-9.

19. Kucher N, Rossi E, De Rosa M, et al. Massive Pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 2006;113(4):577-82.

20. Stein P, Matta F. Case Fatality Rate with Pulmonary Embolectomy for Acute Pulmonary Embolism. Am J Med. 2012;125:471-7.

The case

A 49-year-old morbidly obese woman presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath and abdominal distention. On presentation, her blood pressure was 100/60 mm Hg with a heart rate of 110, respiratory rate of 24, and a pulse oximetric saturation (SpO2) of 86% on room air. Troponin T was elevated at 0.3 ng/mL. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with intravenous contrast showed saddle pulmonary embolism (PE) with dilated right ventricle (RV). CT abdomen/pelvis revealed a very large uterine mass with diffuse lymphadenopathy.

Heparin infusion was started promptly. Echocardiogram demonstrated RV strain. Findings on duplex ultrasound of the lower extremities were consistent with acute deep vein thromboses (DVT) involving the left common femoral vein and the right popliteal vein. Biopsy of a supraclavicular lymph node showed high grade undifferentiated carcinoma most likely of uterine origin.

Clinical questions

What, if any, therapeutic options should be considered beyond standard systemic anticoagulation? Is there a role for:

1. Systemic thrombolysis?

2. Catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT)?

3. Inferior vena cava (IVC) filter placement?

What is the appropriate management of “submassive” PE?

In the case of massive PE, where the thrombus is located in the central pulmonary vasculature and associated with hypotension due to impaired cardiac output, systemic thrombolysis, embolectomy, and CDT are indicated as potentially life-saving measures. However, the evidence is less clear when the PE is large and has led to RV strain, but without overt hemodynamic instability. This is commonly known as an intermediate risk or “submassive” PE. Submassive PE based on American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines is:1

An acute PE without systemic hypotension (systolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg) but with either RV dysfunction or myocardial necrosis. RV dysfunction is defined by the presence of at least one of these following:

• RV dilation (apical 4-chamber RV diameter divided by LV diameter greater than 0.9) or RV systolic dysfunction on echocardiography;

• RV dilation on CT, elevation of BNP (greater than 90 pg/mL), elevation of N-terminal pro-BNP (greater than 500 pg/mL);

• Electrocardiographic changes (new complete or incomplete right bundle branch block, anteroseptal ST elevation or depression, or anteroseptal T-wave inversion).

Myocardial necrosis is defined as elevated troponin I (greater than 0.4 ng/mL) or elevated troponin T (greater than 0.1 ng/mL).

Why is submassive PE of clinical significance?

In 1999, analysis of the International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry (ICOPER) revealed that RV dysfunction in PE patients was associated with a near doubling of the 3-month mortality risk (hazard ratio 2.0, 1.3-2.9).2 Given this increased risk, one could draw the logical conclusion that we need to treat submassive PE more aggressively than PE without RV strain. But will this necessarily result in a better outcome for the patient given the 3% risk of intracranial hemorrhage associated with thrombolytic therapy?

In the clinical scenario above, the patient did meet the definition of submassive PE. While the patient did not experience systemic hypotension, she did have RV dilation on CT, RV systolic dysfunction on echo as well as an elevated Troponin T level. In addition to starting anticoagulant therapy, what more should be done to increase her probability of a good outcome?

The AHA recommends that systemic thrombolysis and CDT be considered for patients with acute submassive PE if they have clinical evidence of adverse prognosis, including worsening respiratory failure, severe RV dysfunction, or major myocardial necrosis and low risk of bleeding complications (Class IIB; Level of Evidence C).1

The 2016 American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) guidelines update3 recommends systemically administered thrombolytic therapy over no therapy in selected patients with acute PE who deteriorate after starting anticoagulant therapy but have yet to develop hypotension and who have a low bleeding risk (Grade 2C recommendation).

Systemic thrombolysis

Systemic thrombolysis is administered as an intravenous thrombolytic infusion delivered over a period of time. The Food and Drug Administration–approved thrombolytic drugs currently include tissue plasminogen activator (tPA)/alteplase, streptokinase and urokinase.

Efficacy of low dose thrombolysis was studied in MOPETT 2013,5 a single-center, prospective, randomized, open label study, in which 126 participants found to have submassive PE based on symptoms and CT angiographic or ventilation/perfusion scan data received either 50 mg tPA plus heparin or heparin anticoagulation alone. The composite endpoint of pulmonary hypertension and recurrent PE at 28 months was 16% in the tPA group compared to 63% in the control group (P less than .001). Systemic thrombolysis was associated with lower risk of pulmonary hypertension and recurrent PE, although no mortality benefit was seen in this small study.

In the randomized, double-blind PEITHO trial (n = 1,006) of 20146 comparing tenecteplase plus heparin versus heparin in the submassive PE patients, the primary outcomes of death and hemodynamic decompensation occurred in 2.6% of the tenecteplase group, compared to 5.6% in the placebo group (P = .02). Thrombolytic therapy was associated with 2% rate of hemorrhagic stroke, whereas hemorrhagic stroke in the placebo group was 0.2% (P = .03). In this case, systemic thrombolysis was associated with a 3% lower risk of death and hemodynamic instability, but also a 1.8% increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke.

Catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT)

CDT was originally developed to treat arterial, dialysis graft and deep vein thromboses, but is now approved by the FDA for the treatment of acute submassive or massive PE.

A wire is passed through the embolus and a multihole infusion catheter is placed, through which a thrombolytic drug is infused over 12-24 hours. The direct delivery of the drug into the thrombus is thought to be as effective as systemic therapy but with a lower risk of bleeding. If more rapid thrombus removal is indicated due to large clot burden and hemodynamic instability, mechanical therapies, such as fragmentation and aspiration, can be used as an adjunct to CDT. However, these mechanical techniques carry the risk of pulmonary artery injury, and therefore should only be used as a last resort. An ultrasound-emitting wire can be added to the multihole infusion catheter to expedite thrombolysis by ultrasonically disrupting the thrombus, a technique known as ultrasound-enhanced thrombolysis (EKOS).7,10

The ULTIMA 2014 trial,8 a small, randomized, open-label study of Ultrasound-Assisted Catheter Directed Thrombolysis (USAT, the term can be used interchangeably with EKOS) versus heparin anticoagulation alone in 59 patients, was designed to study if the former strategy was better at improving the primary outcome measure of RV/LV ratio in submassive PE patients. The mean reduction in RV/LV ratio was 0.30 +/– 0.20 in the USAT group compared to 0.03 +/– 0.16 in the heparin group (P less than .001). However, no significant difference in mortality or bleeding was observed in the groups at 90-day follow up.

The PERFECT 2015 Trial,9 a multicenter registry-based study, prospectively enrolled 101 patients who received CDT as first-line therapy for massive and submassive PE. Among patients with submassive PE, 97.3% were found to have “clinical success” with this treatment, defined as stabilization of hemodynamics, improvement in pulmonary hypertension and right heart strain, and survival to hospital discharge. There was no major bleeding or intracranial hemorrhage. Subgroup analyses in this study comparing USAT against standard CDT did not reveal significant difference in average pulmonary pressure changes, average thrombolytic doses, or average infusion times.

A prospective single-arm multicenter trial, SEATTLE II 2015,10 evaluated the efficacy of EKOS in a sample of 159 patients. Patients with both massive and submassive PE received approximately 24 mg tPA infused via a catheter over 12-24 hours. The primary efficacy outcome was the chest CT-measured RV/LV ratio decrease from the baseline compared to 48 hours post procedure. The pre- and postprocedure ratio was 1.55 versus 1.13 respectively (P less than .001), indicating that EKOS decreased RV dilation. No intracranial hemorrhage was observed and the investigators did not comment on long-term outcomes such as mortality or quality of life. The study was limited by the lack of a comparison group, such as anticoagulation with heparin as monotherapy, or systemic thrombolysis or standard CDT.

Treatment of submassive PE varies between different institutions. There simply are not adequate data comparing low dose systemic thrombolysis, CDT, EKOS, and standard heparin anticoagulation to make firm recommendations. Some investigators feel low-dose systemic thrombolysis is probably as good as the expensive catheter-based thrombolytic therapies.11,12 Low-dose thrombolytic therapy can be followed by use of oral direct factor Xa inhibitors for maintenance of antithrombotic activity.13

Bottom line

In our institution, the interventional radiology team screens patients who meet criteria for submassive PE on a case-by-case basis. We use pulmonary angiographic data (nature and extent of the thrombus), clinical stability, and analysis of other comorbid conditions to decide the best treatment modality for an individual patient. Our team prefers EKOS for submassive PE patients as well as for massive PE patients and as a rescue procedure for patients who have failed systemic thrombolysis.

Until more data are available to support firm guidelines, we feel establishing multidisciplinary teams composed of interventional radiologists, intensivists, cardiologists, and vascular surgeons is prudent to make individualized decisions and to achieve the best outcomes for our patients.14

IVC filter

Since the patient in this case already has a submassive PE, can she tolerate additional clot burden should her remaining DVT embolize again? Is there a role for IVC filter?

The implantation of IVC filters has increased significantly in the past 30 years, without quality evidence justifying their use.15

The 2016 Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report states clearly: In patients with acute DVT of the leg or PE who are treated with anticoagulants, the use of an IVC filter is not recommended (Grade 1B).3 This recommendation is based on findings of the Prevention du Risque d’Embolie Pulmonaire par Interruption Cave (PREPIC) randomized trial,16 and the recently published PREPIC 2 randomized trial,17 both showing that in anticoagulated patients with PE and DVT, concurrent placement of an IVC filter for 3 months did not reduce recurrent PE, including fatal PE.

CHEST guidelines state that an IVC filter should not be routinely placed as an adjunct in patients with PE and DVT. However, what about in the subgroup of patients with submassive or massive PE in whom another PE would be catastrophic? Clinical data are lacking in this area.

Deshpande et al. reported on a series of six patients with massive PE and cardiopulmonary instability; patients all received an IVC filter with anticoagulation. The short-term outcome was excellent, but long-term follow-up was not done.18 Kucher and colleagues reported that from the ICOPER in 2006, out of the 108 massive PE patients with systolic arterial pressure under 90 mm Hg, 11 patients received adjunctive IVC filter placement. None of these 11 patients developed recurrent PE in 90 days and 10 of them survived at least 90 days; IVC filter placement was associated with a reduction in 90-day mortality. In this study, the placement of an IVC filter was entirely decided by the physicians at different sites.19 In a 2012 study examining case fatality rates in 3,770 patients with acute PE who received pulmonary embolectomy, the data showed that in both unstable and stable patients, case fatality rates were lower in those who received an IVC filter.20

Although the above data are favorable for adjunctive IVC filter placement in massive PE patients, at least in short-term outcomes, the small size and lack of randomization preclude establishment of evidence-based guidelines. The 2016 CHEST guidelines point out that as it is uncertain if there is benefit to place an IVC filter adjunctively in anticoagulated patients with severe PE, in this specific subgroup of patients, the recommendation against insertion of an IVC filter in patients with acute PE who are anticoagulated may not apply.3

Bottom line

There is no evidence-based guideline as to whether IVC filters should be placed adjunctively in patients with submassive or massive PE; however, based on expert consensus, it may be appropriate to place an IVC filter as an adjunct to anticoagulation in patients with severe PE. The decision should be individualized based on each patient’s characteristics, preferences, and institutional expertise.

In our case, in hope of preventing further embolic burden, the patient received an IVC filter the day after presentation. Despite the initiation of anticoagulation with heparin, she remained tachycardic and tachypneic, prompting referral for CDT. The interventional radiology team did not feel that she was a good candidate, given her persistent vaginal bleeding and widely metastatic uterine carcinoma. She was switched to therapeutic enoxaparin after no further invasive intervention was deemed appropriate. Her respiratory status did not improve and bilevel positive airway pressure was initiated. Taking into consideration the terminal nature of her cancer, she ultimately elected to pursue comfort care and died shortly afterward.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Benjamin A. Hohmuth, MD, A. Joseph Layon, MD, and Luis L. Nadal, MD, for their review of the article and invaluable feedback.

Dr. Wenqian Wang, Dr. Vedamurthy, and Dr. Wang are based in the department of hospital medicine at The Medicine Institute, Geisinger Health System, Danville, Penn. Contact Dr. Wenqian Wang at [email protected].

Key Points

• Use pulmonary angiographic data, clinical stability, and analysis of other comorbid conditions to decide the best treatment modality.

• Our team prefers ultrasound-enhanced thrombolysis (EKOS) for submassive PE patients, massive PE patients, and as a rescue procedure for patients who fail systemic thrombolysis.

• Establishing multidisciplinary teams composed of interventional radiologists, intensivists, cardiologists, and vascular surgeons is prudent to make individualized decisions.

• It may be appropriate to place an IVC filter as an adjunct to anticoagulation in patients with severe PE.

References

1. Jaff MR, McMurtry MS, Archer SL, et al. Management of massive and submassive pulmonary embolism, iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis, and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:1788-1830.

2. Goldhaber SZ, Visani L, De Rosa M. Acute pulmonary embolism: clinical outcomes in the International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry (ICOPER). Lancet. 1999;353:1386-9.

3. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2016;149:315-52.

4. Konstantinides S, Geibel A, Heusel G, Heinrich F, Kasper W. Management Strategies and Prognosis of Pulmonary Embolism-3 Trial Investigators. Heparin plus alteplase compared with heparin alone in patients with submassive pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1143-50.

5. Sharifi M, Bay C, Skrocki L, Rahimi F, Mehdipour M, “MOPETT” Investigators. Moderate pulmonary embolism treated with thrombolysis (from the “MOPETT” Trial). Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:273-7.

6. Meyer G, Vicaut E, Danays T, et al. Fibrinolysis for patients with intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1402-11.

7. Kuo WT. Endovascular therapy for acute pulmonary embolism. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2012;23:167-79. e164

8. Kucher N, Boekstegers P, Muller OJ, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of ultrasound-assisted catheter-directed thrombolysis for acute intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 2014;129:479-86.

9. Kuo WT, Banerjee A, Kim PS, et al. Pulmonary Embolism Response to Fragmentation, Embolectomy, and Catheter Thrombolysis (PERFECT): Initial Results From a Prospective Multicenter Registry. Chest. 2015;148:667-73.

10. Piazza G, Hohlfelder B, Jaff MR, et al. A Prospective, Single-Arm, Multicenter Trial of Ultrasound-Facilitated, Catheter-Directed, Low-Dose Fibrinolysis for Acute Massive and Submassive Pulmonary Embolism: The SEATTLE II Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:1382-92.

11. Sharifi M. Systemic Full Dose, Half Dose, and Catheter Directed Thrombolysis for Pulmonary Embolism. When to Use and How to Choose? Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2016;18:31.

12. Wang C, Zhai Z, Yang Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of low dose recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator for the treatment of acute pulmonary thromboembolism: a randomized, multicenter, controlled trial. Chest. 2010;137:254-62.

13. Sharifi M, Vajo Z, Freeman W, Bay C, Sharifi M, Schwartz F. Transforming and simplifying the treatment of pulmonary embolism: “safe dose” thrombolysis plus new oral anticoagulants. Lung. 2015;193:369-74.

14. Kabrhel C, Rosovsky R, Channick R, et al. A Multidisciplinary Pulmonary Embolism Response Team: Initial 30-Month Experience With a Novel Approach to Delivery of Care to Patients With Submassive and Massive Pulmonary Embolism. Chest. 2016;150:384-93.

15. Lessne ML, Sing RF. Counterpoint: Do the Benefits Outweigh the Risks for Most Patients Under Consideration for inferior vena cava filters? No. Chest. 2016; 150(6):1182-4.

16. The PREPIC Study Group. Eight-year follow-up of patients with permanent vena cava filters in the prevention of pulmonary embolism: the PREPIC (Prevention du Risque d’Embolie Pulmonaire par Interruption Cave) randomized study. Circulation. 2005;112(3):416-22.

17. Mismetti P, Laporte S, Pellerin O, et al. Effect of a retrievable inferior vena cava filter plus anticoagulation vs. anticoagulation alone on risk of recurrent pulmonary embolism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015. 313(16):1627-35.

18. Deshpande KS, Hatem C, Karwa M, et al. The use of inferior vena cava filter as a treatment modality for massive pulmonary embolism. A case series and review of pathophysiology. Respir Med. 2002.96(12):984-9.

19. Kucher N, Rossi E, De Rosa M, et al. Massive Pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 2006;113(4):577-82.

20. Stein P, Matta F. Case Fatality Rate with Pulmonary Embolectomy for Acute Pulmonary Embolism. Am J Med. 2012;125:471-7.

The case

A 49-year-old morbidly obese woman presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath and abdominal distention. On presentation, her blood pressure was 100/60 mm Hg with a heart rate of 110, respiratory rate of 24, and a pulse oximetric saturation (SpO2) of 86% on room air. Troponin T was elevated at 0.3 ng/mL. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with intravenous contrast showed saddle pulmonary embolism (PE) with dilated right ventricle (RV). CT abdomen/pelvis revealed a very large uterine mass with diffuse lymphadenopathy.

Heparin infusion was started promptly. Echocardiogram demonstrated RV strain. Findings on duplex ultrasound of the lower extremities were consistent with acute deep vein thromboses (DVT) involving the left common femoral vein and the right popliteal vein. Biopsy of a supraclavicular lymph node showed high grade undifferentiated carcinoma most likely of uterine origin.

Clinical questions

What, if any, therapeutic options should be considered beyond standard systemic anticoagulation? Is there a role for:

1. Systemic thrombolysis?

2. Catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT)?

3. Inferior vena cava (IVC) filter placement?

What is the appropriate management of “submassive” PE?

In the case of massive PE, where the thrombus is located in the central pulmonary vasculature and associated with hypotension due to impaired cardiac output, systemic thrombolysis, embolectomy, and CDT are indicated as potentially life-saving measures. However, the evidence is less clear when the PE is large and has led to RV strain, but without overt hemodynamic instability. This is commonly known as an intermediate risk or “submassive” PE. Submassive PE based on American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines is:1

An acute PE without systemic hypotension (systolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg) but with either RV dysfunction or myocardial necrosis. RV dysfunction is defined by the presence of at least one of these following:

• RV dilation (apical 4-chamber RV diameter divided by LV diameter greater than 0.9) or RV systolic dysfunction on echocardiography;

• RV dilation on CT, elevation of BNP (greater than 90 pg/mL), elevation of N-terminal pro-BNP (greater than 500 pg/mL);

• Electrocardiographic changes (new complete or incomplete right bundle branch block, anteroseptal ST elevation or depression, or anteroseptal T-wave inversion).

Myocardial necrosis is defined as elevated troponin I (greater than 0.4 ng/mL) or elevated troponin T (greater than 0.1 ng/mL).

Why is submassive PE of clinical significance?

In 1999, analysis of the International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry (ICOPER) revealed that RV dysfunction in PE patients was associated with a near doubling of the 3-month mortality risk (hazard ratio 2.0, 1.3-2.9).2 Given this increased risk, one could draw the logical conclusion that we need to treat submassive PE more aggressively than PE without RV strain. But will this necessarily result in a better outcome for the patient given the 3% risk of intracranial hemorrhage associated with thrombolytic therapy?

In the clinical scenario above, the patient did meet the definition of submassive PE. While the patient did not experience systemic hypotension, she did have RV dilation on CT, RV systolic dysfunction on echo as well as an elevated Troponin T level. In addition to starting anticoagulant therapy, what more should be done to increase her probability of a good outcome?

The AHA recommends that systemic thrombolysis and CDT be considered for patients with acute submassive PE if they have clinical evidence of adverse prognosis, including worsening respiratory failure, severe RV dysfunction, or major myocardial necrosis and low risk of bleeding complications (Class IIB; Level of Evidence C).1

The 2016 American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) guidelines update3 recommends systemically administered thrombolytic therapy over no therapy in selected patients with acute PE who deteriorate after starting anticoagulant therapy but have yet to develop hypotension and who have a low bleeding risk (Grade 2C recommendation).

Systemic thrombolysis

Systemic thrombolysis is administered as an intravenous thrombolytic infusion delivered over a period of time. The Food and Drug Administration–approved thrombolytic drugs currently include tissue plasminogen activator (tPA)/alteplase, streptokinase and urokinase.