User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Epidemiology of meningitis and encephalitis in the United States

Clinical Question: What is the epidemiology of meningitis and encephalitis in adults in the United States?

Background: Previous epidemiologic studies have been smaller with less clinical information available and without steroid usage rates.

Study Design: A retrospective database review.

Setting: The Premier HealthCare Database, including hospitals of all types and sizes.

Synopsis: Of patients aged 18 or older, 26,429 were included with a primary or secondary discharge diagnosis of meningitis or encephalitis from 2011-2014. Enterovirus was the most common infectious cause (51%), followed by unknown etiology (19%), bacterial (14%), herpetic (8%), fungal (3%), and arboviruses (1%). Of patients, 4.2% had HIV.

Steroids were given on the first day of antibiotics in 25.9%. The only statistical mortality benefit was found with steroid use in pneumococcal meningitis (6.7% vs. 12.5%; P = .0245), with a trend toward increased mortality for steroids in fungal meningitis.

Of patients, 87.2% were admitted through the ED, though 22.5% of lumbar punctures were done after admission and 77.4% were discharged home.

Bottom Line: Enterovirus was the most common cause of adult meningoencephalitis, and patients with pneumococcal meningitis who received steroids had decreased mortality.

Citation: Hasbun R, Ning R, Balada-Llasat JM, Chung J, Duff S, Bozzette S, et al. Meningitis and encephalitis in the United States from 2011-2014. Published online, Apr 17, 2017. Clin Infect Dis. 2017. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix319.

Dr. Hall is an assistant professor in the University of Kentucky division of hospital medicine and pediatrics.

Clinical Question: What is the epidemiology of meningitis and encephalitis in adults in the United States?

Background: Previous epidemiologic studies have been smaller with less clinical information available and without steroid usage rates.

Study Design: A retrospective database review.

Setting: The Premier HealthCare Database, including hospitals of all types and sizes.

Synopsis: Of patients aged 18 or older, 26,429 were included with a primary or secondary discharge diagnosis of meningitis or encephalitis from 2011-2014. Enterovirus was the most common infectious cause (51%), followed by unknown etiology (19%), bacterial (14%), herpetic (8%), fungal (3%), and arboviruses (1%). Of patients, 4.2% had HIV.

Steroids were given on the first day of antibiotics in 25.9%. The only statistical mortality benefit was found with steroid use in pneumococcal meningitis (6.7% vs. 12.5%; P = .0245), with a trend toward increased mortality for steroids in fungal meningitis.

Of patients, 87.2% were admitted through the ED, though 22.5% of lumbar punctures were done after admission and 77.4% were discharged home.

Bottom Line: Enterovirus was the most common cause of adult meningoencephalitis, and patients with pneumococcal meningitis who received steroids had decreased mortality.

Citation: Hasbun R, Ning R, Balada-Llasat JM, Chung J, Duff S, Bozzette S, et al. Meningitis and encephalitis in the United States from 2011-2014. Published online, Apr 17, 2017. Clin Infect Dis. 2017. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix319.

Dr. Hall is an assistant professor in the University of Kentucky division of hospital medicine and pediatrics.

Clinical Question: What is the epidemiology of meningitis and encephalitis in adults in the United States?

Background: Previous epidemiologic studies have been smaller with less clinical information available and without steroid usage rates.

Study Design: A retrospective database review.

Setting: The Premier HealthCare Database, including hospitals of all types and sizes.

Synopsis: Of patients aged 18 or older, 26,429 were included with a primary or secondary discharge diagnosis of meningitis or encephalitis from 2011-2014. Enterovirus was the most common infectious cause (51%), followed by unknown etiology (19%), bacterial (14%), herpetic (8%), fungal (3%), and arboviruses (1%). Of patients, 4.2% had HIV.

Steroids were given on the first day of antibiotics in 25.9%. The only statistical mortality benefit was found with steroid use in pneumococcal meningitis (6.7% vs. 12.5%; P = .0245), with a trend toward increased mortality for steroids in fungal meningitis.

Of patients, 87.2% were admitted through the ED, though 22.5% of lumbar punctures were done after admission and 77.4% were discharged home.

Bottom Line: Enterovirus was the most common cause of adult meningoencephalitis, and patients with pneumococcal meningitis who received steroids had decreased mortality.

Citation: Hasbun R, Ning R, Balada-Llasat JM, Chung J, Duff S, Bozzette S, et al. Meningitis and encephalitis in the United States from 2011-2014. Published online, Apr 17, 2017. Clin Infect Dis. 2017. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix319.

Dr. Hall is an assistant professor in the University of Kentucky division of hospital medicine and pediatrics.

Sneak Peek: Journal of Hospital Medicine – August 2017

BACKGROUND: There is increasing recognition that patients have critical insights into care experiences, including about breakdowns in care. Harnessing patient perspectives for hospital improvement requires an in-depth understanding of the types of breakdowns patients identify and the impact of these events.

RESULTS: Of 979 interviewees, 386 (39.4%) believed they had experienced at least one breakdown in care. The most common reported breakdowns involved information exchange (n = 158; 16.1%), medications (n = 120; 12.3%), delays in admission (n = 90; 9.2%), team communication (n = 65; 6.6%), providers’ manner (n = 62; 6.3%), and discharge (n = 56; 5.7%). Of the 386 interviewees who reported a breakdown, 140 (36.3%) perceived associated harm. Patient-perceived harms included physical (e.g., pain), emotional (e.g., distress, worry), damage to relationship with providers, need for additional care or prolonged hospital stay, and life disruption. We found higher rates of reporting breakdowns among younger (less than 60 years old) patients (45.4% vs. 34.5%; P less than .001), those with at least some college education (46.8% vs 32.7%; P less than .001), and those with another person (family or friend) present during the interview or interviewed in lieu of the patient (53.4% vs 37.8%; P = .002).

CONCLUSIONS: When asked directly, almost 4 out of 10 hospitalized patients reported a breakdown in their care. Patient-perceived breakdowns in care are frequently associated with perceived harm, illustrating the importance of detecting and addressing these events.

Also in JHM

Excess readmission vs. excess penalties: Maximum readmission penalties as a function of socioeconomics and geography

AUTHORS: Chris M. Caracciolo, MPH, Devin M. Parker, MS, Emily Marshall, MS, Jeremiah R. Brown, PhD, MS

Impact of a safety huddle-based intervention on monitor alarm rates in low-acuity pediatric intensive care unit patientsAUTHORS: Maya Dewan, MD, MPH, Heather Wolfe, MD, MSHP, Richard Lin, MD, Eileen Ware, RN, Michelle Weiss, RN, Lihai Song, MS, Matthew MacMurchy, BA, Daniela Davis, MD, MSCE, Christopher P. Bonafide MD MSCE

Perspectives of clinicians at skilled nursing facilities on 30-day hospital readmissions: A qualitative studyAUTHORS: Bennett W. Clark, MD, Katelyn Baron, MSIOP, Kathleen Tynan-McKiernan, RN, MSN, Meredith Campbell Britton, LMSW, Karl E. Minges, PhD, Sarwat I. Chaudhry, MD

Use of postacute facility care in children hospitalized with acute respiratory illnessAUTHORS: Jay G. Berry, MD, MPH, Karen M. Wilson, MD, MPH, FAAP, Helene Dumas, PT, MS, Edwin Simpser, MD, Jane O’Brien, MD, Kathleen Whitford, PNP, Rachna May, MD, Vineeta Mittal, MD, Nancy Murphy, MD, David Steinhorn, MD, Rishi Agrawal, MD, MPH, Kris Rehm, MD, Michelle Marks, DO, FAAP, SFHM, Christine Traul, MD, Michael Dribbon, PhD, Christopher J. Haines, DO, MBA, FAAP, FACEP, Matt Hall, PhD

A contemporary assessment of mechanical complication rates and trainee perceptions of central venous catheter insertionAUTHORS: Lauren Heidemann, MD, Niket Nathani, MD, Rommel Sagana, MD, Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc, Michael Heung, MD, MS

For more articles and subscription information, visit www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com.

BACKGROUND: There is increasing recognition that patients have critical insights into care experiences, including about breakdowns in care. Harnessing patient perspectives for hospital improvement requires an in-depth understanding of the types of breakdowns patients identify and the impact of these events.

RESULTS: Of 979 interviewees, 386 (39.4%) believed they had experienced at least one breakdown in care. The most common reported breakdowns involved information exchange (n = 158; 16.1%), medications (n = 120; 12.3%), delays in admission (n = 90; 9.2%), team communication (n = 65; 6.6%), providers’ manner (n = 62; 6.3%), and discharge (n = 56; 5.7%). Of the 386 interviewees who reported a breakdown, 140 (36.3%) perceived associated harm. Patient-perceived harms included physical (e.g., pain), emotional (e.g., distress, worry), damage to relationship with providers, need for additional care or prolonged hospital stay, and life disruption. We found higher rates of reporting breakdowns among younger (less than 60 years old) patients (45.4% vs. 34.5%; P less than .001), those with at least some college education (46.8% vs 32.7%; P less than .001), and those with another person (family or friend) present during the interview or interviewed in lieu of the patient (53.4% vs 37.8%; P = .002).

CONCLUSIONS: When asked directly, almost 4 out of 10 hospitalized patients reported a breakdown in their care. Patient-perceived breakdowns in care are frequently associated with perceived harm, illustrating the importance of detecting and addressing these events.

Also in JHM

Excess readmission vs. excess penalties: Maximum readmission penalties as a function of socioeconomics and geography

AUTHORS: Chris M. Caracciolo, MPH, Devin M. Parker, MS, Emily Marshall, MS, Jeremiah R. Brown, PhD, MS

Impact of a safety huddle-based intervention on monitor alarm rates in low-acuity pediatric intensive care unit patientsAUTHORS: Maya Dewan, MD, MPH, Heather Wolfe, MD, MSHP, Richard Lin, MD, Eileen Ware, RN, Michelle Weiss, RN, Lihai Song, MS, Matthew MacMurchy, BA, Daniela Davis, MD, MSCE, Christopher P. Bonafide MD MSCE

Perspectives of clinicians at skilled nursing facilities on 30-day hospital readmissions: A qualitative studyAUTHORS: Bennett W. Clark, MD, Katelyn Baron, MSIOP, Kathleen Tynan-McKiernan, RN, MSN, Meredith Campbell Britton, LMSW, Karl E. Minges, PhD, Sarwat I. Chaudhry, MD

Use of postacute facility care in children hospitalized with acute respiratory illnessAUTHORS: Jay G. Berry, MD, MPH, Karen M. Wilson, MD, MPH, FAAP, Helene Dumas, PT, MS, Edwin Simpser, MD, Jane O’Brien, MD, Kathleen Whitford, PNP, Rachna May, MD, Vineeta Mittal, MD, Nancy Murphy, MD, David Steinhorn, MD, Rishi Agrawal, MD, MPH, Kris Rehm, MD, Michelle Marks, DO, FAAP, SFHM, Christine Traul, MD, Michael Dribbon, PhD, Christopher J. Haines, DO, MBA, FAAP, FACEP, Matt Hall, PhD

A contemporary assessment of mechanical complication rates and trainee perceptions of central venous catheter insertionAUTHORS: Lauren Heidemann, MD, Niket Nathani, MD, Rommel Sagana, MD, Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc, Michael Heung, MD, MS

For more articles and subscription information, visit www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com.

BACKGROUND: There is increasing recognition that patients have critical insights into care experiences, including about breakdowns in care. Harnessing patient perspectives for hospital improvement requires an in-depth understanding of the types of breakdowns patients identify and the impact of these events.

RESULTS: Of 979 interviewees, 386 (39.4%) believed they had experienced at least one breakdown in care. The most common reported breakdowns involved information exchange (n = 158; 16.1%), medications (n = 120; 12.3%), delays in admission (n = 90; 9.2%), team communication (n = 65; 6.6%), providers’ manner (n = 62; 6.3%), and discharge (n = 56; 5.7%). Of the 386 interviewees who reported a breakdown, 140 (36.3%) perceived associated harm. Patient-perceived harms included physical (e.g., pain), emotional (e.g., distress, worry), damage to relationship with providers, need for additional care or prolonged hospital stay, and life disruption. We found higher rates of reporting breakdowns among younger (less than 60 years old) patients (45.4% vs. 34.5%; P less than .001), those with at least some college education (46.8% vs 32.7%; P less than .001), and those with another person (family or friend) present during the interview or interviewed in lieu of the patient (53.4% vs 37.8%; P = .002).

CONCLUSIONS: When asked directly, almost 4 out of 10 hospitalized patients reported a breakdown in their care. Patient-perceived breakdowns in care are frequently associated with perceived harm, illustrating the importance of detecting and addressing these events.

Also in JHM

Excess readmission vs. excess penalties: Maximum readmission penalties as a function of socioeconomics and geography

AUTHORS: Chris M. Caracciolo, MPH, Devin M. Parker, MS, Emily Marshall, MS, Jeremiah R. Brown, PhD, MS

Impact of a safety huddle-based intervention on monitor alarm rates in low-acuity pediatric intensive care unit patientsAUTHORS: Maya Dewan, MD, MPH, Heather Wolfe, MD, MSHP, Richard Lin, MD, Eileen Ware, RN, Michelle Weiss, RN, Lihai Song, MS, Matthew MacMurchy, BA, Daniela Davis, MD, MSCE, Christopher P. Bonafide MD MSCE

Perspectives of clinicians at skilled nursing facilities on 30-day hospital readmissions: A qualitative studyAUTHORS: Bennett W. Clark, MD, Katelyn Baron, MSIOP, Kathleen Tynan-McKiernan, RN, MSN, Meredith Campbell Britton, LMSW, Karl E. Minges, PhD, Sarwat I. Chaudhry, MD

Use of postacute facility care in children hospitalized with acute respiratory illnessAUTHORS: Jay G. Berry, MD, MPH, Karen M. Wilson, MD, MPH, FAAP, Helene Dumas, PT, MS, Edwin Simpser, MD, Jane O’Brien, MD, Kathleen Whitford, PNP, Rachna May, MD, Vineeta Mittal, MD, Nancy Murphy, MD, David Steinhorn, MD, Rishi Agrawal, MD, MPH, Kris Rehm, MD, Michelle Marks, DO, FAAP, SFHM, Christine Traul, MD, Michael Dribbon, PhD, Christopher J. Haines, DO, MBA, FAAP, FACEP, Matt Hall, PhD

A contemporary assessment of mechanical complication rates and trainee perceptions of central venous catheter insertionAUTHORS: Lauren Heidemann, MD, Niket Nathani, MD, Rommel Sagana, MD, Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc, Michael Heung, MD, MS

For more articles and subscription information, visit www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com.

Managing hospital- and ventilator-associated pneumonia

Background

Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) is defined as pneumonia that develops 48 hours or more after admission that was not present on admission; and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is pneumonia that develops 48 hours or more after endotracheal intubation.

HAP and VAP are common afflictions in hospitalized patients, accounting for nearly one-quarter of all hospital-acquired infections. They confer mortality rates of 24%-50%, increasing to nearly 75% if caused by resistant organisms.1,2 Given the high prevalence and significant mortality associated with these types of pneumonia, diagnosis and treatment are essential. Treatment must be balanced against potential unintended consequences of antibiotic use including Clostridium difficile infections and the promotion of resistant bacteria caused by poor antibiotic stewardship.

Given the frequency with which HAP and VAP occur, and the need for equipoise with antibiotic use, it is essential that all practicing clinicians have an evidence-based construct for the diagnosis and treatment of HAP and VAP.

Guideline updates

In 2016, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Thoracic Society (ATS) reconvened after 11 years to update their recommendations for the treatment of HAP and VAP.2 The decision to update their recommendations was based on the availability of new evidence regarding the diagnosis and treatment of these conditions.

Included in this review are guideline updates on methods for diagnosis, initial antibiotic choice, pathogen-specific therapy, and duration of therapy. The guidelines also have recommendations for the role of inhaled antibiotics and pharmacokinetic optimization of antibiotic dosing, which will not be reviewed here.

Methods for Diagnosis: The use of semi-quantitative, noninvasive sampling of respiratory cultures is preferred for HAP and VAP, rather than empiric treatment or quantitative cultures (i.e., bronchoalveolar lavage, protected-specimen brush and blind bronchial sampling).

Initial antibiotic choice: For HAP and VAP, clinicians should include therapy targeting S. aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and other gram-negative bacilli. Therapy for methicillin-resistant S. aureus should be included if patients are at high risk for death (i.e., septic shock or ventilated patients) or if local drug-resistant prevalence is greater than 10%-20%. Similarly, two antipseudomonal antibiotics should be used only with empiric therapy if the patient is at high risk for mortality or local drug-resistant prevalence is greater than 10%.

Duration of therapy: HAP and VAP should be treated for 7 days with regimens that are tailored to culture data when available, assuming there has been appropriate clinical response. Procalcitonin may be paired with clinical judgment when considering antibiotic discontinuation.

Guideline analysis

There are several notable differences between the 2016 IDSA/ATS guidelines and the 2005 guidelines.3 The earlier guidelines recommended strong consideration of invasive respiratory cultures such as bronchoalveolar lavage or protected-specimen brush sampling for HAP/VAP. It is now recommended that only noninvasive cultures be performed in most clinical scenarios.

Last, the updated guidelines recommend dual therapy for potential or documented Pseudomonas infection only for patients at high risk for mortality or in hospitals with a high prevalence of antibiotic resistance; previously, dual antipseudomonal therapy was recommended for all cases of HAP and VAP, based upon the risk of developing resistant strains with monotherapy.3

Since 2005, several organizations have released guidelines addressing the management of HAP and VAP.1,4,5,6 These are largely in keeping with the current version released by the IDSA/ATS. Across all guidelines, there is a focus on the importance of local antibiograms for appropriate and effective treatment, and the use of noninvasive culture data to guide therapy. Also, all groups recommend a short-course (7-8 days) of antibiotics for both HAP and VAP, assuming there has been an appropriate clinical response. The recent Canadian guidelines have one unique recommendation, which is to avoid the use of ceftazidime for suspected Pseudomonas pneumonia, based upon inferior outcomes when compared to alternative regimens.5

Takeaways

When considering the diagnosis of HAP and VAP, clinicians should be aware that the category of HCAP has been removed from current guidelines, and methods for microbiological diagnosis have been simplified.7 In addition, initial antibiotic selection should rely on institution-specific antibiograms and local resistance patterns when available. Recommended duration of therapy has been shortened, and should not include aminoglycosides.

Finally, antibiotic stewardship is the responsibility of each clinician and de-escalation of therapy for HAP and VAP should be guided by available respiratory cultures.

Dr. Hippensteel is a pulmonologist in Aurora, Colo. Dr. Sippel is visiting associate professor of clinical practice, medicine-pulmonary sciences & critical care at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

References

1. Masterton R, Galloway A, French G, Street M, Armstrong J, Brown E, Cleverley J, Dilworth P, Fry C, Gascoigne A. Guidelines for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia in the UK: report of the working party on hospital-acquired pneumonia of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62(1):5-34.

2. Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, Muscedere J, Sweeney DA, Palmer LB, Napolitano LM, O’grady NP, Bartlett JG, Carratalà J. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016:ciw353.

3. Society AT, America IDSo. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(4):388-416.

4. Dalhoff K, Abele-Horn M, Andreas S, Bauer T, von Baum H, Deja M, Ewig S, Gastmeier P, Gatermann S, Gerlach H. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of adult patients with nosocomial pneumonia. S-3 Guideline of the German Society for Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, the German Society for Infectious Diseases, the German Society for Hygiene and Microbiology, the German Respiratory Society and the Paul-Ehrlich-Society for Chemotherapy. Pneumologie (Stuttgart, Germany). 2012;66(12):707-65.

5. Rotstein C, Evans G, Born A, Grossman R, Light RB, Magder S, McTaggart B, Weiss K, Zhanel GG. Clinical practice guidelines for hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology. 2008;19(1):19-53.

6. Coffin SE, Klompas M, Classen D, Arias KM, Podgorny K, Anderson DJ, Burstin H, Calfee DP, Dubberke ER, Fraser V. Strategies to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia in acute care hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(S1):S31-S40.

7. Tablan OC, Anderson LJ, Besser R, Bridges C, Hajjeh R. Guidelines for preventing healthcare-associated pneumonia, 2003. MMWR. 2004;53(RR-3):1-36.

Background

Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) is defined as pneumonia that develops 48 hours or more after admission that was not present on admission; and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is pneumonia that develops 48 hours or more after endotracheal intubation.

HAP and VAP are common afflictions in hospitalized patients, accounting for nearly one-quarter of all hospital-acquired infections. They confer mortality rates of 24%-50%, increasing to nearly 75% if caused by resistant organisms.1,2 Given the high prevalence and significant mortality associated with these types of pneumonia, diagnosis and treatment are essential. Treatment must be balanced against potential unintended consequences of antibiotic use including Clostridium difficile infections and the promotion of resistant bacteria caused by poor antibiotic stewardship.

Given the frequency with which HAP and VAP occur, and the need for equipoise with antibiotic use, it is essential that all practicing clinicians have an evidence-based construct for the diagnosis and treatment of HAP and VAP.

Guideline updates

In 2016, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Thoracic Society (ATS) reconvened after 11 years to update their recommendations for the treatment of HAP and VAP.2 The decision to update their recommendations was based on the availability of new evidence regarding the diagnosis and treatment of these conditions.

Included in this review are guideline updates on methods for diagnosis, initial antibiotic choice, pathogen-specific therapy, and duration of therapy. The guidelines also have recommendations for the role of inhaled antibiotics and pharmacokinetic optimization of antibiotic dosing, which will not be reviewed here.

Methods for Diagnosis: The use of semi-quantitative, noninvasive sampling of respiratory cultures is preferred for HAP and VAP, rather than empiric treatment or quantitative cultures (i.e., bronchoalveolar lavage, protected-specimen brush and blind bronchial sampling).

Initial antibiotic choice: For HAP and VAP, clinicians should include therapy targeting S. aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and other gram-negative bacilli. Therapy for methicillin-resistant S. aureus should be included if patients are at high risk for death (i.e., septic shock or ventilated patients) or if local drug-resistant prevalence is greater than 10%-20%. Similarly, two antipseudomonal antibiotics should be used only with empiric therapy if the patient is at high risk for mortality or local drug-resistant prevalence is greater than 10%.

Duration of therapy: HAP and VAP should be treated for 7 days with regimens that are tailored to culture data when available, assuming there has been appropriate clinical response. Procalcitonin may be paired with clinical judgment when considering antibiotic discontinuation.

Guideline analysis

There are several notable differences between the 2016 IDSA/ATS guidelines and the 2005 guidelines.3 The earlier guidelines recommended strong consideration of invasive respiratory cultures such as bronchoalveolar lavage or protected-specimen brush sampling for HAP/VAP. It is now recommended that only noninvasive cultures be performed in most clinical scenarios.

Last, the updated guidelines recommend dual therapy for potential or documented Pseudomonas infection only for patients at high risk for mortality or in hospitals with a high prevalence of antibiotic resistance; previously, dual antipseudomonal therapy was recommended for all cases of HAP and VAP, based upon the risk of developing resistant strains with monotherapy.3

Since 2005, several organizations have released guidelines addressing the management of HAP and VAP.1,4,5,6 These are largely in keeping with the current version released by the IDSA/ATS. Across all guidelines, there is a focus on the importance of local antibiograms for appropriate and effective treatment, and the use of noninvasive culture data to guide therapy. Also, all groups recommend a short-course (7-8 days) of antibiotics for both HAP and VAP, assuming there has been an appropriate clinical response. The recent Canadian guidelines have one unique recommendation, which is to avoid the use of ceftazidime for suspected Pseudomonas pneumonia, based upon inferior outcomes when compared to alternative regimens.5

Takeaways

When considering the diagnosis of HAP and VAP, clinicians should be aware that the category of HCAP has been removed from current guidelines, and methods for microbiological diagnosis have been simplified.7 In addition, initial antibiotic selection should rely on institution-specific antibiograms and local resistance patterns when available. Recommended duration of therapy has been shortened, and should not include aminoglycosides.

Finally, antibiotic stewardship is the responsibility of each clinician and de-escalation of therapy for HAP and VAP should be guided by available respiratory cultures.

Dr. Hippensteel is a pulmonologist in Aurora, Colo. Dr. Sippel is visiting associate professor of clinical practice, medicine-pulmonary sciences & critical care at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

References

1. Masterton R, Galloway A, French G, Street M, Armstrong J, Brown E, Cleverley J, Dilworth P, Fry C, Gascoigne A. Guidelines for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia in the UK: report of the working party on hospital-acquired pneumonia of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62(1):5-34.

2. Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, Muscedere J, Sweeney DA, Palmer LB, Napolitano LM, O’grady NP, Bartlett JG, Carratalà J. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016:ciw353.

3. Society AT, America IDSo. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(4):388-416.

4. Dalhoff K, Abele-Horn M, Andreas S, Bauer T, von Baum H, Deja M, Ewig S, Gastmeier P, Gatermann S, Gerlach H. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of adult patients with nosocomial pneumonia. S-3 Guideline of the German Society for Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, the German Society for Infectious Diseases, the German Society for Hygiene and Microbiology, the German Respiratory Society and the Paul-Ehrlich-Society for Chemotherapy. Pneumologie (Stuttgart, Germany). 2012;66(12):707-65.

5. Rotstein C, Evans G, Born A, Grossman R, Light RB, Magder S, McTaggart B, Weiss K, Zhanel GG. Clinical practice guidelines for hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology. 2008;19(1):19-53.

6. Coffin SE, Klompas M, Classen D, Arias KM, Podgorny K, Anderson DJ, Burstin H, Calfee DP, Dubberke ER, Fraser V. Strategies to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia in acute care hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(S1):S31-S40.

7. Tablan OC, Anderson LJ, Besser R, Bridges C, Hajjeh R. Guidelines for preventing healthcare-associated pneumonia, 2003. MMWR. 2004;53(RR-3):1-36.

Background

Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) is defined as pneumonia that develops 48 hours or more after admission that was not present on admission; and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is pneumonia that develops 48 hours or more after endotracheal intubation.

HAP and VAP are common afflictions in hospitalized patients, accounting for nearly one-quarter of all hospital-acquired infections. They confer mortality rates of 24%-50%, increasing to nearly 75% if caused by resistant organisms.1,2 Given the high prevalence and significant mortality associated with these types of pneumonia, diagnosis and treatment are essential. Treatment must be balanced against potential unintended consequences of antibiotic use including Clostridium difficile infections and the promotion of resistant bacteria caused by poor antibiotic stewardship.

Given the frequency with which HAP and VAP occur, and the need for equipoise with antibiotic use, it is essential that all practicing clinicians have an evidence-based construct for the diagnosis and treatment of HAP and VAP.

Guideline updates

In 2016, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Thoracic Society (ATS) reconvened after 11 years to update their recommendations for the treatment of HAP and VAP.2 The decision to update their recommendations was based on the availability of new evidence regarding the diagnosis and treatment of these conditions.

Included in this review are guideline updates on methods for diagnosis, initial antibiotic choice, pathogen-specific therapy, and duration of therapy. The guidelines also have recommendations for the role of inhaled antibiotics and pharmacokinetic optimization of antibiotic dosing, which will not be reviewed here.

Methods for Diagnosis: The use of semi-quantitative, noninvasive sampling of respiratory cultures is preferred for HAP and VAP, rather than empiric treatment or quantitative cultures (i.e., bronchoalveolar lavage, protected-specimen brush and blind bronchial sampling).

Initial antibiotic choice: For HAP and VAP, clinicians should include therapy targeting S. aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and other gram-negative bacilli. Therapy for methicillin-resistant S. aureus should be included if patients are at high risk for death (i.e., septic shock or ventilated patients) or if local drug-resistant prevalence is greater than 10%-20%. Similarly, two antipseudomonal antibiotics should be used only with empiric therapy if the patient is at high risk for mortality or local drug-resistant prevalence is greater than 10%.

Duration of therapy: HAP and VAP should be treated for 7 days with regimens that are tailored to culture data when available, assuming there has been appropriate clinical response. Procalcitonin may be paired with clinical judgment when considering antibiotic discontinuation.

Guideline analysis

There are several notable differences between the 2016 IDSA/ATS guidelines and the 2005 guidelines.3 The earlier guidelines recommended strong consideration of invasive respiratory cultures such as bronchoalveolar lavage or protected-specimen brush sampling for HAP/VAP. It is now recommended that only noninvasive cultures be performed in most clinical scenarios.

Last, the updated guidelines recommend dual therapy for potential or documented Pseudomonas infection only for patients at high risk for mortality or in hospitals with a high prevalence of antibiotic resistance; previously, dual antipseudomonal therapy was recommended for all cases of HAP and VAP, based upon the risk of developing resistant strains with monotherapy.3

Since 2005, several organizations have released guidelines addressing the management of HAP and VAP.1,4,5,6 These are largely in keeping with the current version released by the IDSA/ATS. Across all guidelines, there is a focus on the importance of local antibiograms for appropriate and effective treatment, and the use of noninvasive culture data to guide therapy. Also, all groups recommend a short-course (7-8 days) of antibiotics for both HAP and VAP, assuming there has been an appropriate clinical response. The recent Canadian guidelines have one unique recommendation, which is to avoid the use of ceftazidime for suspected Pseudomonas pneumonia, based upon inferior outcomes when compared to alternative regimens.5

Takeaways

When considering the diagnosis of HAP and VAP, clinicians should be aware that the category of HCAP has been removed from current guidelines, and methods for microbiological diagnosis have been simplified.7 In addition, initial antibiotic selection should rely on institution-specific antibiograms and local resistance patterns when available. Recommended duration of therapy has been shortened, and should not include aminoglycosides.

Finally, antibiotic stewardship is the responsibility of each clinician and de-escalation of therapy for HAP and VAP should be guided by available respiratory cultures.

Dr. Hippensteel is a pulmonologist in Aurora, Colo. Dr. Sippel is visiting associate professor of clinical practice, medicine-pulmonary sciences & critical care at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

References

1. Masterton R, Galloway A, French G, Street M, Armstrong J, Brown E, Cleverley J, Dilworth P, Fry C, Gascoigne A. Guidelines for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia in the UK: report of the working party on hospital-acquired pneumonia of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62(1):5-34.

2. Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, Muscedere J, Sweeney DA, Palmer LB, Napolitano LM, O’grady NP, Bartlett JG, Carratalà J. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016:ciw353.

3. Society AT, America IDSo. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(4):388-416.

4. Dalhoff K, Abele-Horn M, Andreas S, Bauer T, von Baum H, Deja M, Ewig S, Gastmeier P, Gatermann S, Gerlach H. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of adult patients with nosocomial pneumonia. S-3 Guideline of the German Society for Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, the German Society for Infectious Diseases, the German Society for Hygiene and Microbiology, the German Respiratory Society and the Paul-Ehrlich-Society for Chemotherapy. Pneumologie (Stuttgart, Germany). 2012;66(12):707-65.

5. Rotstein C, Evans G, Born A, Grossman R, Light RB, Magder S, McTaggart B, Weiss K, Zhanel GG. Clinical practice guidelines for hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology. 2008;19(1):19-53.

6. Coffin SE, Klompas M, Classen D, Arias KM, Podgorny K, Anderson DJ, Burstin H, Calfee DP, Dubberke ER, Fraser V. Strategies to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia in acute care hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(S1):S31-S40.

7. Tablan OC, Anderson LJ, Besser R, Bridges C, Hajjeh R. Guidelines for preventing healthcare-associated pneumonia, 2003. MMWR. 2004;53(RR-3):1-36.

PVC phlebitis rates varied widely, depending on assessment tool

Rates of phlebitis associated with peripheral venous catheters (PVC) ranged from less than 1% to 34% depending on which assessment tool researchers used in a large cross-sectional study.

Rates also varied within individual instruments because they included several possible case definitions, Katarina Göransson, PhD, and her associates reported in Lancet Haematology. “We find it concerning that our study shows variation of the proportion of PVCs causing phlebitis both within and across the instruments investigated,” they wrote. “How to best measure phlebitis outcomes is still unclear, since no universally accepted instrument exists that has had rigorous testing. From a work environment and patient safety perspective, clinical staff engaged in PVC management should be aware of the absence of adequately validated instruments for phlebitis assessment.”

There are many tools to measure PVC-related phlebitis, but no consensus on which to use, and past studies have reported rates of anywhere from 2% to 62%. Hypothesizing that instrument variability contributed to this discrepancy, the researchers tested 17 instruments in 1,032 patients who had 1,175 PVCs placed at 12 inpatient units in Sweden. Eight tools used clinical definitions, seven used severity rating systems, and two used scoring systems (Lancet Haematol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026[17]30122-9).

Rates of PVC-induced phlebitis reached 12% (137 cases) when the researchers used case definition tools, up to 31% when they used scoring systems (P less than .0001), and up to 34% when they used severity rating systems (P less than .0001, compared with the 12% rate). “The proportion within instruments ranged from less than 1% to 28%,” they added. “We [also] identified face validity issues, such as use of indistinct or complex measurements and inconsistent measurements or definitions.”

The investigators did not perform a systematic review to identify these instruments, and they did not necessarily use the most recent versions, they noted. Nevertheless, the findings have direct implications for hospital quality control measures, which require using a single validated instrument over time to generate meaningful results, they said. Hence, the investigators recommended developing a joint research program to develop reliable measures of PVC-related adverse events and better support clinicians who are trying to decide whether to remove PVCs.

The investigators reported having no funding sources and no competing interests.

Rates of phlebitis associated with peripheral venous catheters (PVC) ranged from less than 1% to 34% depending on which assessment tool researchers used in a large cross-sectional study.

Rates also varied within individual instruments because they included several possible case definitions, Katarina Göransson, PhD, and her associates reported in Lancet Haematology. “We find it concerning that our study shows variation of the proportion of PVCs causing phlebitis both within and across the instruments investigated,” they wrote. “How to best measure phlebitis outcomes is still unclear, since no universally accepted instrument exists that has had rigorous testing. From a work environment and patient safety perspective, clinical staff engaged in PVC management should be aware of the absence of adequately validated instruments for phlebitis assessment.”

There are many tools to measure PVC-related phlebitis, but no consensus on which to use, and past studies have reported rates of anywhere from 2% to 62%. Hypothesizing that instrument variability contributed to this discrepancy, the researchers tested 17 instruments in 1,032 patients who had 1,175 PVCs placed at 12 inpatient units in Sweden. Eight tools used clinical definitions, seven used severity rating systems, and two used scoring systems (Lancet Haematol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026[17]30122-9).

Rates of PVC-induced phlebitis reached 12% (137 cases) when the researchers used case definition tools, up to 31% when they used scoring systems (P less than .0001), and up to 34% when they used severity rating systems (P less than .0001, compared with the 12% rate). “The proportion within instruments ranged from less than 1% to 28%,” they added. “We [also] identified face validity issues, such as use of indistinct or complex measurements and inconsistent measurements or definitions.”

The investigators did not perform a systematic review to identify these instruments, and they did not necessarily use the most recent versions, they noted. Nevertheless, the findings have direct implications for hospital quality control measures, which require using a single validated instrument over time to generate meaningful results, they said. Hence, the investigators recommended developing a joint research program to develop reliable measures of PVC-related adverse events and better support clinicians who are trying to decide whether to remove PVCs.

The investigators reported having no funding sources and no competing interests.

Rates of phlebitis associated with peripheral venous catheters (PVC) ranged from less than 1% to 34% depending on which assessment tool researchers used in a large cross-sectional study.

Rates also varied within individual instruments because they included several possible case definitions, Katarina Göransson, PhD, and her associates reported in Lancet Haematology. “We find it concerning that our study shows variation of the proportion of PVCs causing phlebitis both within and across the instruments investigated,” they wrote. “How to best measure phlebitis outcomes is still unclear, since no universally accepted instrument exists that has had rigorous testing. From a work environment and patient safety perspective, clinical staff engaged in PVC management should be aware of the absence of adequately validated instruments for phlebitis assessment.”

There are many tools to measure PVC-related phlebitis, but no consensus on which to use, and past studies have reported rates of anywhere from 2% to 62%. Hypothesizing that instrument variability contributed to this discrepancy, the researchers tested 17 instruments in 1,032 patients who had 1,175 PVCs placed at 12 inpatient units in Sweden. Eight tools used clinical definitions, seven used severity rating systems, and two used scoring systems (Lancet Haematol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026[17]30122-9).

Rates of PVC-induced phlebitis reached 12% (137 cases) when the researchers used case definition tools, up to 31% when they used scoring systems (P less than .0001), and up to 34% when they used severity rating systems (P less than .0001, compared with the 12% rate). “The proportion within instruments ranged from less than 1% to 28%,” they added. “We [also] identified face validity issues, such as use of indistinct or complex measurements and inconsistent measurements or definitions.”

The investigators did not perform a systematic review to identify these instruments, and they did not necessarily use the most recent versions, they noted. Nevertheless, the findings have direct implications for hospital quality control measures, which require using a single validated instrument over time to generate meaningful results, they said. Hence, the investigators recommended developing a joint research program to develop reliable measures of PVC-related adverse events and better support clinicians who are trying to decide whether to remove PVCs.

The investigators reported having no funding sources and no competing interests.

FROM LANCET HAEMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Rates of PVC-induced phlebitis varied widely within and between assessment instruments.

Major finding: Rates were as high as 12% (137 cases) based on the case definition tools, up to 31% based on the scoring systems (P less than .0001), and up to 34% based on the severity rating systems (P less than .0001, compared with the case definition rate).

Data source: A cross-sectional study of 17 instruments used to identify phlebitis associated with peripheral venous catheters.

Disclosures: The investigators reported having no funding sources and no competing interests.

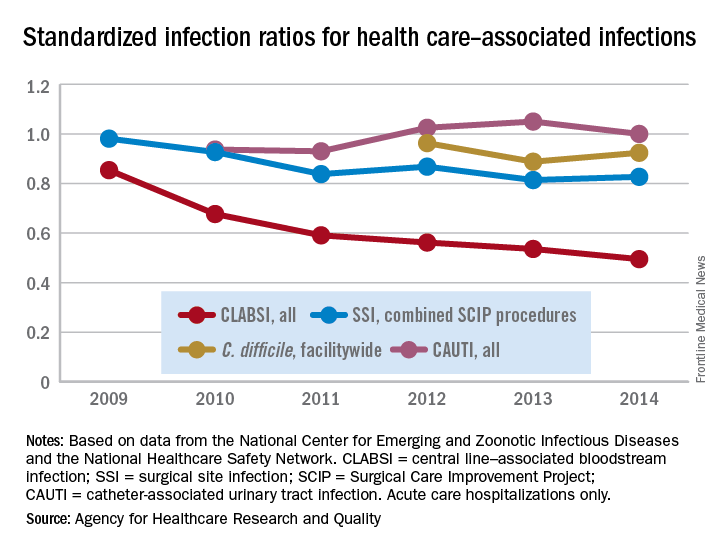

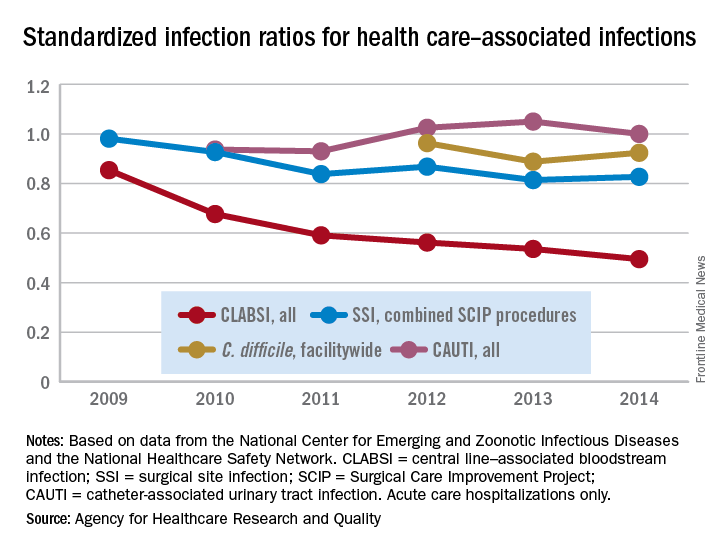

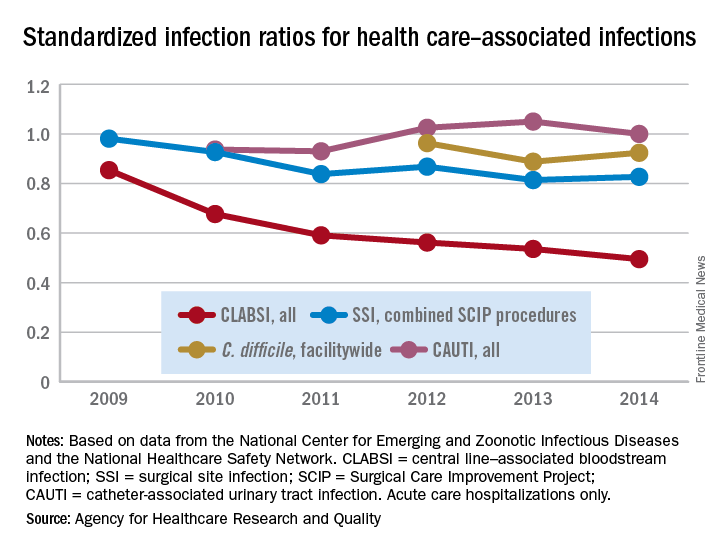

Standardized infection ratio for CLABSI almost halved since 2009

The standardized infection ratio (SIR) for central line–associated bloodstream infections dropped 42% from 2009 to 2014, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

For acute care hospitalizations, the SIR for central line–associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) fell from 0.854 in 2009 to 0.495 in 2014. Over that same time period, the SIR for surgical site infections involving Surgical Care Improvement Project procedures decreased from 0.981 to 0.827 – almost 16%, the AHRQ said in its annual National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report.

From 2010 to 2014, the SIR for catheter-associated urinary tract infections increased 6.7% from 0.937 to 1.000, but that change was not significant. For laboratory-identified hospital-onset Clostridium difficile infection, the SIR dropped from 0.963 to 0.924 – about 4% – from 2012 to 2014, the AHRQ reported using data from the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases and the National Healthcare Safety Network.

The standardized infection ratio (SIR) for central line–associated bloodstream infections dropped 42% from 2009 to 2014, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

For acute care hospitalizations, the SIR for central line–associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) fell from 0.854 in 2009 to 0.495 in 2014. Over that same time period, the SIR for surgical site infections involving Surgical Care Improvement Project procedures decreased from 0.981 to 0.827 – almost 16%, the AHRQ said in its annual National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report.

From 2010 to 2014, the SIR for catheter-associated urinary tract infections increased 6.7% from 0.937 to 1.000, but that change was not significant. For laboratory-identified hospital-onset Clostridium difficile infection, the SIR dropped from 0.963 to 0.924 – about 4% – from 2012 to 2014, the AHRQ reported using data from the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases and the National Healthcare Safety Network.

The standardized infection ratio (SIR) for central line–associated bloodstream infections dropped 42% from 2009 to 2014, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

For acute care hospitalizations, the SIR for central line–associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) fell from 0.854 in 2009 to 0.495 in 2014. Over that same time period, the SIR for surgical site infections involving Surgical Care Improvement Project procedures decreased from 0.981 to 0.827 – almost 16%, the AHRQ said in its annual National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report.

From 2010 to 2014, the SIR for catheter-associated urinary tract infections increased 6.7% from 0.937 to 1.000, but that change was not significant. For laboratory-identified hospital-onset Clostridium difficile infection, the SIR dropped from 0.963 to 0.924 – about 4% – from 2012 to 2014, the AHRQ reported using data from the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases and the National Healthcare Safety Network.

Everything We Say and Do: Digging deep brings empathy and sincere communication

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

What I say and do

I find a way to connect with my patients to express sincere appreciation.

A recent “Everything We Say and Do” column focused on an important element of high-impact physician-patient communication: closing the encounter by thanking the patient. Evidence suggests that patients feel more valued by their providers when expressions of gratitude are offered. However, it is not always easy to find a genuine and sincere way to incorporate a “thank you” at the end of a visit.

Why I do it

The physician-patient relationship is an inherently hierarchical one. Recognizing that the encounter represents a meeting of two people who equally stand to gain from the interaction goes a long way to strengthen trust, improve communication, and enhance the therapeutic effect.

How I do it

Many who don’t regularly experience serious illness firsthand take good health for granted. I appreciate my patients for reminding me to cherish my own good health. My patients offer me glimpses of hope as I watch them and their families rally through the trials that serious illness brings; in addition, they provide me inspiration and ideas for how I will handle these issues myself someday.

Some in other fields feel unfulfilled with their work as they contemplate their professional legacy. On the contrary, our patients validate our sense of purpose and strengthen our self-worth, as they allow us to participate in one of the noblest endeavors – caring for the sick. The unique insights physicians garner from patients via our intimate access to the private struggles and fears that all humans suffer, but rarely share, should strengthen our empathy for the greater human condition and enhance our own personal relationships.

Recalibrating my perspective makes it easier to harness and express sincere gratitude to patients, and enhances my ability to connect on a deeper level with those I serve.

Greg Seymann is clinical professor and vice chief for academic affairs, UCSD Division of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

What I say and do

I find a way to connect with my patients to express sincere appreciation.

A recent “Everything We Say and Do” column focused on an important element of high-impact physician-patient communication: closing the encounter by thanking the patient. Evidence suggests that patients feel more valued by their providers when expressions of gratitude are offered. However, it is not always easy to find a genuine and sincere way to incorporate a “thank you” at the end of a visit.

Why I do it

The physician-patient relationship is an inherently hierarchical one. Recognizing that the encounter represents a meeting of two people who equally stand to gain from the interaction goes a long way to strengthen trust, improve communication, and enhance the therapeutic effect.

How I do it

Many who don’t regularly experience serious illness firsthand take good health for granted. I appreciate my patients for reminding me to cherish my own good health. My patients offer me glimpses of hope as I watch them and their families rally through the trials that serious illness brings; in addition, they provide me inspiration and ideas for how I will handle these issues myself someday.

Some in other fields feel unfulfilled with their work as they contemplate their professional legacy. On the contrary, our patients validate our sense of purpose and strengthen our self-worth, as they allow us to participate in one of the noblest endeavors – caring for the sick. The unique insights physicians garner from patients via our intimate access to the private struggles and fears that all humans suffer, but rarely share, should strengthen our empathy for the greater human condition and enhance our own personal relationships.

Recalibrating my perspective makes it easier to harness and express sincere gratitude to patients, and enhances my ability to connect on a deeper level with those I serve.

Greg Seymann is clinical professor and vice chief for academic affairs, UCSD Division of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

What I say and do

I find a way to connect with my patients to express sincere appreciation.

A recent “Everything We Say and Do” column focused on an important element of high-impact physician-patient communication: closing the encounter by thanking the patient. Evidence suggests that patients feel more valued by their providers when expressions of gratitude are offered. However, it is not always easy to find a genuine and sincere way to incorporate a “thank you” at the end of a visit.

Why I do it

The physician-patient relationship is an inherently hierarchical one. Recognizing that the encounter represents a meeting of two people who equally stand to gain from the interaction goes a long way to strengthen trust, improve communication, and enhance the therapeutic effect.

How I do it

Many who don’t regularly experience serious illness firsthand take good health for granted. I appreciate my patients for reminding me to cherish my own good health. My patients offer me glimpses of hope as I watch them and their families rally through the trials that serious illness brings; in addition, they provide me inspiration and ideas for how I will handle these issues myself someday.

Some in other fields feel unfulfilled with their work as they contemplate their professional legacy. On the contrary, our patients validate our sense of purpose and strengthen our self-worth, as they allow us to participate in one of the noblest endeavors – caring for the sick. The unique insights physicians garner from patients via our intimate access to the private struggles and fears that all humans suffer, but rarely share, should strengthen our empathy for the greater human condition and enhance our own personal relationships.

Recalibrating my perspective makes it easier to harness and express sincere gratitude to patients, and enhances my ability to connect on a deeper level with those I serve.

Greg Seymann is clinical professor and vice chief for academic affairs, UCSD Division of Hospital Medicine.

How to make the move away from opioids for chronic noncancer pain

Standard care of chronic noncancer pain should start moving away from chronic opioid treatment, which can put patients in greater danger of developing a substance use disorder, according to evidence presented at a meeting held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education.

As the effects of the U.S. opioid epidemic continue to gain public attention – recently spurring a declaration of a state of emergency –

Use of opioid therapy for pain conditions such as osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, and migraine – once a common treatment approach – has been shown to be a dangerous breeding ground for opioid substance use disorders, and physicians would do well to re-evaluate their treatment methods, according to Edwin Salsitz, MD, assistant clinical professor at Mount Sinai Beth Israel Hospital, New York.

“Each prescriber is going to have to review this, digest it, reflect on it, and decide what they are going to do,” said Dr. Salsitz in an interview. “Base it on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guideline as a good starting point, and then individualize it for yourself and your patients.”

One of the major steps toward lowering the rate of opioid addiction through prescription is avoiding opioids as a treatment for acute pain.

“The first recommendation [of the CDC guideline] is nonpharmaceutical therapy, including physical therapy, massage therapy, acupuncture, and cognitive-behavioral therapy – and there’s a whole lot of evidence for these types of therapy,” said Dr. Salsitz. “The second option is that if you’re going to use medications, use those that aren’t opioids, like Tylenol, Motrin, and antidepressants.”

If opioids are necessary, said Dr. Salsitz, immediate-release opioids in limited prescriptions are a good way to lower the risk of addiction.

“The extended-release opioids have many more milligrams than the immediate-release opioids,” according to Dr. Salsitz. “For example, in New York state, we have a law now that says for acute pain, you cannot prescribe for more than a 7-day amount.”

That 7-day limit helps keep excess opioids out of households, he noted, making it harder for patients to share their medication with friends and family, which has proven to be the most common source for opioids during the onset of substance use disorders. In the first 12 months of use, friends and family members accounted for 55% of reported sources of opioids, according to the U.S. 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Providers may also want to consider screening pain patients for psychological disorders, Dr. Salsitz said, as many psychological conditions are associated with a high risk of developing a substance use disorder. Patients with major depression, dysthymia, or panic disorder were 3.43, 6.51, and 5.37 times more likely, respectively, than those without to initiate a prescription for and regularly use opioids, according to a study cited by Dr. Salsitz (Arch Intern Med. 2006 Oct 23;166[19]:2087-93).

One of the largest barriers preventing providers from implementing these methods, however, is a lack of resources, particularly in rural areas with increasing rates of opioid substance use disorders and limited provider options.

While these limitations do pose a problem, physicians should not feel they can’t provide proper care, according to Dr. Salsitz. “I think that each individual provider, wherever they are located, can do a reasonable job.”

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

Standard care of chronic noncancer pain should start moving away from chronic opioid treatment, which can put patients in greater danger of developing a substance use disorder, according to evidence presented at a meeting held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education.

As the effects of the U.S. opioid epidemic continue to gain public attention – recently spurring a declaration of a state of emergency –

Use of opioid therapy for pain conditions such as osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, and migraine – once a common treatment approach – has been shown to be a dangerous breeding ground for opioid substance use disorders, and physicians would do well to re-evaluate their treatment methods, according to Edwin Salsitz, MD, assistant clinical professor at Mount Sinai Beth Israel Hospital, New York.

“Each prescriber is going to have to review this, digest it, reflect on it, and decide what they are going to do,” said Dr. Salsitz in an interview. “Base it on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guideline as a good starting point, and then individualize it for yourself and your patients.”

One of the major steps toward lowering the rate of opioid addiction through prescription is avoiding opioids as a treatment for acute pain.

“The first recommendation [of the CDC guideline] is nonpharmaceutical therapy, including physical therapy, massage therapy, acupuncture, and cognitive-behavioral therapy – and there’s a whole lot of evidence for these types of therapy,” said Dr. Salsitz. “The second option is that if you’re going to use medications, use those that aren’t opioids, like Tylenol, Motrin, and antidepressants.”

If opioids are necessary, said Dr. Salsitz, immediate-release opioids in limited prescriptions are a good way to lower the risk of addiction.

“The extended-release opioids have many more milligrams than the immediate-release opioids,” according to Dr. Salsitz. “For example, in New York state, we have a law now that says for acute pain, you cannot prescribe for more than a 7-day amount.”

That 7-day limit helps keep excess opioids out of households, he noted, making it harder for patients to share their medication with friends and family, which has proven to be the most common source for opioids during the onset of substance use disorders. In the first 12 months of use, friends and family members accounted for 55% of reported sources of opioids, according to the U.S. 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Providers may also want to consider screening pain patients for psychological disorders, Dr. Salsitz said, as many psychological conditions are associated with a high risk of developing a substance use disorder. Patients with major depression, dysthymia, or panic disorder were 3.43, 6.51, and 5.37 times more likely, respectively, than those without to initiate a prescription for and regularly use opioids, according to a study cited by Dr. Salsitz (Arch Intern Med. 2006 Oct 23;166[19]:2087-93).

One of the largest barriers preventing providers from implementing these methods, however, is a lack of resources, particularly in rural areas with increasing rates of opioid substance use disorders and limited provider options.

While these limitations do pose a problem, physicians should not feel they can’t provide proper care, according to Dr. Salsitz. “I think that each individual provider, wherever they are located, can do a reasonable job.”

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

Standard care of chronic noncancer pain should start moving away from chronic opioid treatment, which can put patients in greater danger of developing a substance use disorder, according to evidence presented at a meeting held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education.

As the effects of the U.S. opioid epidemic continue to gain public attention – recently spurring a declaration of a state of emergency –

Use of opioid therapy for pain conditions such as osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, and migraine – once a common treatment approach – has been shown to be a dangerous breeding ground for opioid substance use disorders, and physicians would do well to re-evaluate their treatment methods, according to Edwin Salsitz, MD, assistant clinical professor at Mount Sinai Beth Israel Hospital, New York.

“Each prescriber is going to have to review this, digest it, reflect on it, and decide what they are going to do,” said Dr. Salsitz in an interview. “Base it on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guideline as a good starting point, and then individualize it for yourself and your patients.”

One of the major steps toward lowering the rate of opioid addiction through prescription is avoiding opioids as a treatment for acute pain.

“The first recommendation [of the CDC guideline] is nonpharmaceutical therapy, including physical therapy, massage therapy, acupuncture, and cognitive-behavioral therapy – and there’s a whole lot of evidence for these types of therapy,” said Dr. Salsitz. “The second option is that if you’re going to use medications, use those that aren’t opioids, like Tylenol, Motrin, and antidepressants.”

If opioids are necessary, said Dr. Salsitz, immediate-release opioids in limited prescriptions are a good way to lower the risk of addiction.

“The extended-release opioids have many more milligrams than the immediate-release opioids,” according to Dr. Salsitz. “For example, in New York state, we have a law now that says for acute pain, you cannot prescribe for more than a 7-day amount.”

That 7-day limit helps keep excess opioids out of households, he noted, making it harder for patients to share their medication with friends and family, which has proven to be the most common source for opioids during the onset of substance use disorders. In the first 12 months of use, friends and family members accounted for 55% of reported sources of opioids, according to the U.S. 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Providers may also want to consider screening pain patients for psychological disorders, Dr. Salsitz said, as many psychological conditions are associated with a high risk of developing a substance use disorder. Patients with major depression, dysthymia, or panic disorder were 3.43, 6.51, and 5.37 times more likely, respectively, than those without to initiate a prescription for and regularly use opioids, according to a study cited by Dr. Salsitz (Arch Intern Med. 2006 Oct 23;166[19]:2087-93).

One of the largest barriers preventing providers from implementing these methods, however, is a lack of resources, particularly in rural areas with increasing rates of opioid substance use disorders and limited provider options.

While these limitations do pose a problem, physicians should not feel they can’t provide proper care, according to Dr. Salsitz. “I think that each individual provider, wherever they are located, can do a reasonable job.”

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

FROM PAIN CARE FOR PRIMARY CARE

QI enthusiast to QI leader: Luci Leykum, MD

Editor’s Note: This ongoing series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Luci Leykum, MD, division chief, general and hospital medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio.

Luci Leykum, MD, MBA, MSc, FACP, SFHM, became familiar with inpatient medicine at age 9 years, when her grandfather contracted non-AB hepatitis from a postoperative blood transfusion. In the ensuing years, Dr. Leykum visited her grandfather during his frequent hospitalizations, keeping a close watch on the physicians charged with his care.

“It was when HIV and what we now think is hep C were just emerging, and there was a lot to figure out,” Dr. Leykum recalled of these formative experiences. Her interests in problem-solving, human relationships, and physiology led to enrollment years later as a medical student at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, where her keen observation skills led to a life-changing, “how did we get here?” moment.

Shortly before Dr. Leykum entered residency in 1999, New York Hospital and Columbia Presbyterian Hospital announced that they were merging. The timing was ideal for someone with Dr. Leykum’s acumen in business and medicine, and, as a resident, she began working with the chief medical officer for quality at the new, combined health system to identify quality improvement opportunities.

From there, the projects began pouring in: tracking phone hold times for residents; updating policies to reduce staff exposure to blood-borne pathogens and other infectious diseases; and monitoring flow through the hospitalization process. “In the progression of a few years, I was able to see important aspects of how the system came together,” said Dr. Leykum, “and how decisions were made around standards and metrics for the system as a whole and for its multiple individual hospital facilities.”

In 2004, two years out of residency, Dr. Leykum relocated to San Antonio to accept a clinician investigator position with the South Texas Veterans Health Care System/University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio (UTHSCSA). Research, she said, has allowed her to delve deeper into the underlying mechanisms that impact systems of health care. She sees the complementary sides of quality improvement and research.

“Through our quality improvement initiatives, we can evaluate and improve specific aspects of care, in specific contexts or systems,” Dr. Leykum explained. “In our research projects, we look for new insights that can be more broadly applied across contexts. With funding, you are able to look at things with a scope, depth, or time horizon beyond what you typically have with a QI project.”

Since joining the UTHSCSA/VA system, Dr. Leykum has participated in more than 15 externally funded studies, 6 as principal investigator. She joined SHM’s research committee in 2009, serving as chair for 6 years, and is currently working with the committee to implement the Improving Hospital Outcomes through Patient Engagement (i-HOPE) Study.

I-HOPE, funded through the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, is a project to develop a patient- and stakeholder-partnered research agenda to improve the care of hospitalized patients. Dr. Leykum is also involved in implementing a collaborative care model at University Health System, a patient-partnered, interprofessional model that “focuses on improving interconnections, relationships, and sense making,” in the hospital system, she explained. “It was motivated strongly by our desire to improve our partnerships with patients and other providers in the hospital as a strategy to improve care.”

In addition to the many professional responsibilities she manages as division chief of general and hospital medicine at UTHSCSA – a position she has held for hospital medicine since 2006 and for the combined division since 2016 – Dr. Leykum continues to play an integral role in multiple academic and research initiatives for SHM.

She encourages anyone considering a concentration in QI and research to seek opportunities to actively learn these skills and, more importantly, let other people know their interests.

“The value of talking with colleagues at other places is so high,” she said. “When you actively reach out, you find that most people are happy to share their knowledge. Networking is one of the best parts of the SHM annual meeting – there’s an energy and excitement in learning about what others are doing. Wander into the poster and special interest sessions and see what people are working on, get email addresses, and participate on committees.”

Editor’s Note: This ongoing series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Luci Leykum, MD, division chief, general and hospital medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio.

Luci Leykum, MD, MBA, MSc, FACP, SFHM, became familiar with inpatient medicine at age 9 years, when her grandfather contracted non-AB hepatitis from a postoperative blood transfusion. In the ensuing years, Dr. Leykum visited her grandfather during his frequent hospitalizations, keeping a close watch on the physicians charged with his care.

“It was when HIV and what we now think is hep C were just emerging, and there was a lot to figure out,” Dr. Leykum recalled of these formative experiences. Her interests in problem-solving, human relationships, and physiology led to enrollment years later as a medical student at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, where her keen observation skills led to a life-changing, “how did we get here?” moment.

Shortly before Dr. Leykum entered residency in 1999, New York Hospital and Columbia Presbyterian Hospital announced that they were merging. The timing was ideal for someone with Dr. Leykum’s acumen in business and medicine, and, as a resident, she began working with the chief medical officer for quality at the new, combined health system to identify quality improvement opportunities.

From there, the projects began pouring in: tracking phone hold times for residents; updating policies to reduce staff exposure to blood-borne pathogens and other infectious diseases; and monitoring flow through the hospitalization process. “In the progression of a few years, I was able to see important aspects of how the system came together,” said Dr. Leykum, “and how decisions were made around standards and metrics for the system as a whole and for its multiple individual hospital facilities.”

In 2004, two years out of residency, Dr. Leykum relocated to San Antonio to accept a clinician investigator position with the South Texas Veterans Health Care System/University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio (UTHSCSA). Research, she said, has allowed her to delve deeper into the underlying mechanisms that impact systems of health care. She sees the complementary sides of quality improvement and research.

“Through our quality improvement initiatives, we can evaluate and improve specific aspects of care, in specific contexts or systems,” Dr. Leykum explained. “In our research projects, we look for new insights that can be more broadly applied across contexts. With funding, you are able to look at things with a scope, depth, or time horizon beyond what you typically have with a QI project.”

Since joining the UTHSCSA/VA system, Dr. Leykum has participated in more than 15 externally funded studies, 6 as principal investigator. She joined SHM’s research committee in 2009, serving as chair for 6 years, and is currently working with the committee to implement the Improving Hospital Outcomes through Patient Engagement (i-HOPE) Study.

I-HOPE, funded through the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, is a project to develop a patient- and stakeholder-partnered research agenda to improve the care of hospitalized patients. Dr. Leykum is also involved in implementing a collaborative care model at University Health System, a patient-partnered, interprofessional model that “focuses on improving interconnections, relationships, and sense making,” in the hospital system, she explained. “It was motivated strongly by our desire to improve our partnerships with patients and other providers in the hospital as a strategy to improve care.”

In addition to the many professional responsibilities she manages as division chief of general and hospital medicine at UTHSCSA – a position she has held for hospital medicine since 2006 and for the combined division since 2016 – Dr. Leykum continues to play an integral role in multiple academic and research initiatives for SHM.

She encourages anyone considering a concentration in QI and research to seek opportunities to actively learn these skills and, more importantly, let other people know their interests.

“The value of talking with colleagues at other places is so high,” she said. “When you actively reach out, you find that most people are happy to share their knowledge. Networking is one of the best parts of the SHM annual meeting – there’s an energy and excitement in learning about what others are doing. Wander into the poster and special interest sessions and see what people are working on, get email addresses, and participate on committees.”

Editor’s Note: This ongoing series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Luci Leykum, MD, division chief, general and hospital medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio.

Luci Leykum, MD, MBA, MSc, FACP, SFHM, became familiar with inpatient medicine at age 9 years, when her grandfather contracted non-AB hepatitis from a postoperative blood transfusion. In the ensuing years, Dr. Leykum visited her grandfather during his frequent hospitalizations, keeping a close watch on the physicians charged with his care.

“It was when HIV and what we now think is hep C were just emerging, and there was a lot to figure out,” Dr. Leykum recalled of these formative experiences. Her interests in problem-solving, human relationships, and physiology led to enrollment years later as a medical student at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, where her keen observation skills led to a life-changing, “how did we get here?” moment.

Shortly before Dr. Leykum entered residency in 1999, New York Hospital and Columbia Presbyterian Hospital announced that they were merging. The timing was ideal for someone with Dr. Leykum’s acumen in business and medicine, and, as a resident, she began working with the chief medical officer for quality at the new, combined health system to identify quality improvement opportunities.

From there, the projects began pouring in: tracking phone hold times for residents; updating policies to reduce staff exposure to blood-borne pathogens and other infectious diseases; and monitoring flow through the hospitalization process. “In the progression of a few years, I was able to see important aspects of how the system came together,” said Dr. Leykum, “and how decisions were made around standards and metrics for the system as a whole and for its multiple individual hospital facilities.”