User login

In Case You Missed It: COVID

Desperate long COVID patients turn to unproven alternative therapies

Entrepreneur Maya McNulty, 49, was one of the first victims of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Schenectady, N.Y., businesswoman spent 2 months in the hospital after catching the disease in March 2020. That September, she was diagnosed with long COVID.

“Even a simple task such as unloading the dishwasher became a major challenge,” she says.

Over the next several months, Ms. McNulty saw a range of specialists, including neurologists, pulmonologists, and cardiologists. She had months of physical therapy and respiratory therapy to help regain strength and lung function. While many of the doctors she saw were sympathetic to what she was going through, not all were.

“I saw one neurologist who told me to my face that she didn’t believe in long COVID,” she recalls. “It was particularly astonishing since the hospital they were affiliated with had a long COVID clinic.”

Ms. McNulty began to connect with other patients with long COVID through a support group she created at the end of 2020 on the social media app Clubhouse. They exchanged ideas and stories about what had helped one another, which led her to try, over the next year, a plant-based diet, Chinese medicine, and vitamin C supplements, among other treatments.

She also acted on unscientific reports she found online and did her own research, which led her to discover claims that some asthma patients with chronic coughing responded well to halotherapy, or dry salt therapy, during which patients inhale micro-particles of salt into their lungs to reduce inflammation, widen airways, and thin mucus. She’s been doing this procedure at a clinic near her home for over a year and credits it with helping with her chronic cough, especially as she recovers from her second bout of COVID-19.

It’s not cheap – a single half-hour session can cost up to $50 and isn’t covered by insurance. There’s also no good research to suggest that it can help with long COVID, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

Ms. McNulty understands that but says many people who live with long COVID turn to these treatments out of a sense of desperation.

“When it comes to this condition, we kind of have to be our own advocates. People are so desperate and feel so gaslit by doctors who don’t believe in their symptoms that they play Russian roulette with their body,” she says. “Most just want some hope and a way to relieve pain.”

Across the country, 16 million Americans have long COVID, according to the Brookings Institution’s analysis of a 2022 Census Bureau report. The report also estimated that up to a quarter of them have such debilitating symptoms that they are no longer able to work. While long COVID centers may offer therapies to help relieve symptoms, “there are no evidence-based established treatments for long COVID at this point,” says Andrew Schamess, MD, a professor of internal medicine at Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, who runs its Post-COVID Recovery Program. “You can’t blame patients for looking for alternative remedies to help them. Unfortunately, there are also a lot of people out to make a buck who are selling unproven and disproven therapies.”

Sniffing out the snake oil

With few evidence-based treatments for long COVID, patients with debilitating symptoms can be tempted by unproven options. One that has gotten a lot of attention is hyperbaric oxygen. This therapy has traditionally been used to treat divers who have decompression sickness, or “the bends.” It’s also being touted by some clinics as an effective treatment for long COVID.

A very small trial of 73 patients with long COVID, published in the journal Scientific Reports, found that those treated in a high-pressure oxygen system 5 days a week for 2 months showed improvements in brain fog, pain, energy, sleep, anxiety, and depression, compared with similar patients who got sham treatments. But larger studies are needed to show how well it works, notes Dr. Schamess.

“It’s very expensive – roughly $120 per session – and there just isn’t the evidence there to support its use,” he says.

In addition, the therapy itself carries risks, such as ear and sinus pain, middle ear injury, temporary vision changes, and, very rarely, lung collapse, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

One “particularly troubling” treatment being offered, says Kathleen Bell, MD, chair of the department of physical medicine and rehabilitation at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, is stem cell therapy. This therapy is still in its infancy, but it’s being marketed by some clinics as a way to prevent COVID-19 and also treat long-haul symptoms.

The FDA has issued advisories that there are no products approved to treat long COVID and recommends against their use, except in a clinical trial.

“There’s absolutely no regulation – you don’t know what you’re getting, and there’s no research to suggest this therapy even works,” says Dr. Bell. It’s also prohibitively expensive – one Cayman Islands–based company advertises its treatment for as much as $25,000.

Patients with long COVID are even traveling as far as Cyprus, Germany, and Switzerland for a procedure known as blood washing, in which large needles are inserted into veins to filter blood and remove lipids and inflammatory proteins, the British Medical Journal reported in July. Some patients are also prescribed blood thinners to remove microscopic blood clots that may contribute to long COVID. But this treatment is also expensive, with many people paying $10,000-$15,000 out of pocket, and there’s no published evidence to suggest it works, according to the BMJ.

It can be particularly hard to discern what may work and what’s unproven, since many primary care providers are themselves unfamiliar with even traditional long COVID treatments, Dr. Bell says.

Sorting through supplements

Yufang Lin, MD, an integrative specialist at the Cleveland Clinic, says many patients with long COVID enter her office with bags of supplements.

“There’s no data on them, and in large quantities, they may even be harmful,” she says.

Instead, she works closely with the Cleveland Clinic’s long COVID center to do a thorough workup of each patient, which often includes screening for certain nutritional deficiencies.

“Anecdotally, we do see many patients with long COVID who are deficient in these vitamins and minerals,” says Dr. Lin. “If someone is low, we will suggest the appropriate supplement. Otherwise, we work with them to institute some dietary changes.”

This usually involves a plant-based, anti-inflammatory eating pattern such as the Mediterranean diet, which is rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, fatty fish, and healthy fats such as olive oil and avocados.

Other supplements some doctors recommend for patients with long COVID are meant to treat inflammation, Dr. Bell says, although there’s not good evidence they work. One is the antioxidant coenzyme Q10.

But a small preprint study published in The Lancet, of 121 patients with long COVID who took 500 milligrams a day of coenzyme Q10 for 6 weeks saw no differences in recovery, compared with those who took a placebo. Because the study is still a preprint, it has not been peer-reviewed.

Another is probiotics. A small study, published in the journal Infectious Diseases Diagnosis & Treatment, found that a blend of five lactobacillus probiotics, along with a prebiotic called inulin, taken for 30 days, helped with long-term COVID symptoms such as coughing and fatigue. But larger studies need to be done to support their use.

One that may have more promise is omega-3 fatty acids. Like many other supplements, these may help with long COVID by easing inflammation, says Steven Flanagan, MD, a rehabilitation medicine specialist at NYU Langone who works with long COVID patients. Researchers at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, are studying whether a supplement can help patients who have lost their sense of taste or smell after an infection, but results aren’t yet available.

Among the few alternatives that have been shown to help patients are mindfulness-based therapies – in particular, mindfulness-based forms of exercise such as tai chi and qi gong may be helpful, as they combine a gentle workout with stress reduction.

“Both incorporate meditation, which helps not only to relieve some of the anxiety associated with long COVID but allows patients to redirect their thought process so that they can cope with symptoms better,” says Dr. Flanagan.

A 2022 study, published in BMJ Open, found that these two activities reduced inflammatory markers and improved respiratory muscle strength and function in patients recovering from COVID-19.

“I recommend these activities to all my long COVID patients, as it’s inexpensive and easy to find classes to do either at home or in their community,” he says. “Even if it doesn’t improve their long COVID symptoms, it has other benefits such as increased strength and flexibility that can boost their overall health.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Entrepreneur Maya McNulty, 49, was one of the first victims of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Schenectady, N.Y., businesswoman spent 2 months in the hospital after catching the disease in March 2020. That September, she was diagnosed with long COVID.

“Even a simple task such as unloading the dishwasher became a major challenge,” she says.

Over the next several months, Ms. McNulty saw a range of specialists, including neurologists, pulmonologists, and cardiologists. She had months of physical therapy and respiratory therapy to help regain strength and lung function. While many of the doctors she saw were sympathetic to what she was going through, not all were.

“I saw one neurologist who told me to my face that she didn’t believe in long COVID,” she recalls. “It was particularly astonishing since the hospital they were affiliated with had a long COVID clinic.”

Ms. McNulty began to connect with other patients with long COVID through a support group she created at the end of 2020 on the social media app Clubhouse. They exchanged ideas and stories about what had helped one another, which led her to try, over the next year, a plant-based diet, Chinese medicine, and vitamin C supplements, among other treatments.

She also acted on unscientific reports she found online and did her own research, which led her to discover claims that some asthma patients with chronic coughing responded well to halotherapy, or dry salt therapy, during which patients inhale micro-particles of salt into their lungs to reduce inflammation, widen airways, and thin mucus. She’s been doing this procedure at a clinic near her home for over a year and credits it with helping with her chronic cough, especially as she recovers from her second bout of COVID-19.

It’s not cheap – a single half-hour session can cost up to $50 and isn’t covered by insurance. There’s also no good research to suggest that it can help with long COVID, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

Ms. McNulty understands that but says many people who live with long COVID turn to these treatments out of a sense of desperation.

“When it comes to this condition, we kind of have to be our own advocates. People are so desperate and feel so gaslit by doctors who don’t believe in their symptoms that they play Russian roulette with their body,” she says. “Most just want some hope and a way to relieve pain.”

Across the country, 16 million Americans have long COVID, according to the Brookings Institution’s analysis of a 2022 Census Bureau report. The report also estimated that up to a quarter of them have such debilitating symptoms that they are no longer able to work. While long COVID centers may offer therapies to help relieve symptoms, “there are no evidence-based established treatments for long COVID at this point,” says Andrew Schamess, MD, a professor of internal medicine at Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, who runs its Post-COVID Recovery Program. “You can’t blame patients for looking for alternative remedies to help them. Unfortunately, there are also a lot of people out to make a buck who are selling unproven and disproven therapies.”

Sniffing out the snake oil

With few evidence-based treatments for long COVID, patients with debilitating symptoms can be tempted by unproven options. One that has gotten a lot of attention is hyperbaric oxygen. This therapy has traditionally been used to treat divers who have decompression sickness, or “the bends.” It’s also being touted by some clinics as an effective treatment for long COVID.

A very small trial of 73 patients with long COVID, published in the journal Scientific Reports, found that those treated in a high-pressure oxygen system 5 days a week for 2 months showed improvements in brain fog, pain, energy, sleep, anxiety, and depression, compared with similar patients who got sham treatments. But larger studies are needed to show how well it works, notes Dr. Schamess.

“It’s very expensive – roughly $120 per session – and there just isn’t the evidence there to support its use,” he says.

In addition, the therapy itself carries risks, such as ear and sinus pain, middle ear injury, temporary vision changes, and, very rarely, lung collapse, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

One “particularly troubling” treatment being offered, says Kathleen Bell, MD, chair of the department of physical medicine and rehabilitation at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, is stem cell therapy. This therapy is still in its infancy, but it’s being marketed by some clinics as a way to prevent COVID-19 and also treat long-haul symptoms.

The FDA has issued advisories that there are no products approved to treat long COVID and recommends against their use, except in a clinical trial.

“There’s absolutely no regulation – you don’t know what you’re getting, and there’s no research to suggest this therapy even works,” says Dr. Bell. It’s also prohibitively expensive – one Cayman Islands–based company advertises its treatment for as much as $25,000.

Patients with long COVID are even traveling as far as Cyprus, Germany, and Switzerland for a procedure known as blood washing, in which large needles are inserted into veins to filter blood and remove lipids and inflammatory proteins, the British Medical Journal reported in July. Some patients are also prescribed blood thinners to remove microscopic blood clots that may contribute to long COVID. But this treatment is also expensive, with many people paying $10,000-$15,000 out of pocket, and there’s no published evidence to suggest it works, according to the BMJ.

It can be particularly hard to discern what may work and what’s unproven, since many primary care providers are themselves unfamiliar with even traditional long COVID treatments, Dr. Bell says.

Sorting through supplements

Yufang Lin, MD, an integrative specialist at the Cleveland Clinic, says many patients with long COVID enter her office with bags of supplements.

“There’s no data on them, and in large quantities, they may even be harmful,” she says.

Instead, she works closely with the Cleveland Clinic’s long COVID center to do a thorough workup of each patient, which often includes screening for certain nutritional deficiencies.

“Anecdotally, we do see many patients with long COVID who are deficient in these vitamins and minerals,” says Dr. Lin. “If someone is low, we will suggest the appropriate supplement. Otherwise, we work with them to institute some dietary changes.”

This usually involves a plant-based, anti-inflammatory eating pattern such as the Mediterranean diet, which is rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, fatty fish, and healthy fats such as olive oil and avocados.

Other supplements some doctors recommend for patients with long COVID are meant to treat inflammation, Dr. Bell says, although there’s not good evidence they work. One is the antioxidant coenzyme Q10.

But a small preprint study published in The Lancet, of 121 patients with long COVID who took 500 milligrams a day of coenzyme Q10 for 6 weeks saw no differences in recovery, compared with those who took a placebo. Because the study is still a preprint, it has not been peer-reviewed.

Another is probiotics. A small study, published in the journal Infectious Diseases Diagnosis & Treatment, found that a blend of five lactobacillus probiotics, along with a prebiotic called inulin, taken for 30 days, helped with long-term COVID symptoms such as coughing and fatigue. But larger studies need to be done to support their use.

One that may have more promise is omega-3 fatty acids. Like many other supplements, these may help with long COVID by easing inflammation, says Steven Flanagan, MD, a rehabilitation medicine specialist at NYU Langone who works with long COVID patients. Researchers at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, are studying whether a supplement can help patients who have lost their sense of taste or smell after an infection, but results aren’t yet available.

Among the few alternatives that have been shown to help patients are mindfulness-based therapies – in particular, mindfulness-based forms of exercise such as tai chi and qi gong may be helpful, as they combine a gentle workout with stress reduction.

“Both incorporate meditation, which helps not only to relieve some of the anxiety associated with long COVID but allows patients to redirect their thought process so that they can cope with symptoms better,” says Dr. Flanagan.

A 2022 study, published in BMJ Open, found that these two activities reduced inflammatory markers and improved respiratory muscle strength and function in patients recovering from COVID-19.

“I recommend these activities to all my long COVID patients, as it’s inexpensive and easy to find classes to do either at home or in their community,” he says. “Even if it doesn’t improve their long COVID symptoms, it has other benefits such as increased strength and flexibility that can boost their overall health.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Entrepreneur Maya McNulty, 49, was one of the first victims of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Schenectady, N.Y., businesswoman spent 2 months in the hospital after catching the disease in March 2020. That September, she was diagnosed with long COVID.

“Even a simple task such as unloading the dishwasher became a major challenge,” she says.

Over the next several months, Ms. McNulty saw a range of specialists, including neurologists, pulmonologists, and cardiologists. She had months of physical therapy and respiratory therapy to help regain strength and lung function. While many of the doctors she saw were sympathetic to what she was going through, not all were.

“I saw one neurologist who told me to my face that she didn’t believe in long COVID,” she recalls. “It was particularly astonishing since the hospital they were affiliated with had a long COVID clinic.”

Ms. McNulty began to connect with other patients with long COVID through a support group she created at the end of 2020 on the social media app Clubhouse. They exchanged ideas and stories about what had helped one another, which led her to try, over the next year, a plant-based diet, Chinese medicine, and vitamin C supplements, among other treatments.

She also acted on unscientific reports she found online and did her own research, which led her to discover claims that some asthma patients with chronic coughing responded well to halotherapy, or dry salt therapy, during which patients inhale micro-particles of salt into their lungs to reduce inflammation, widen airways, and thin mucus. She’s been doing this procedure at a clinic near her home for over a year and credits it with helping with her chronic cough, especially as she recovers from her second bout of COVID-19.

It’s not cheap – a single half-hour session can cost up to $50 and isn’t covered by insurance. There’s also no good research to suggest that it can help with long COVID, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

Ms. McNulty understands that but says many people who live with long COVID turn to these treatments out of a sense of desperation.

“When it comes to this condition, we kind of have to be our own advocates. People are so desperate and feel so gaslit by doctors who don’t believe in their symptoms that they play Russian roulette with their body,” she says. “Most just want some hope and a way to relieve pain.”

Across the country, 16 million Americans have long COVID, according to the Brookings Institution’s analysis of a 2022 Census Bureau report. The report also estimated that up to a quarter of them have such debilitating symptoms that they are no longer able to work. While long COVID centers may offer therapies to help relieve symptoms, “there are no evidence-based established treatments for long COVID at this point,” says Andrew Schamess, MD, a professor of internal medicine at Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, who runs its Post-COVID Recovery Program. “You can’t blame patients for looking for alternative remedies to help them. Unfortunately, there are also a lot of people out to make a buck who are selling unproven and disproven therapies.”

Sniffing out the snake oil

With few evidence-based treatments for long COVID, patients with debilitating symptoms can be tempted by unproven options. One that has gotten a lot of attention is hyperbaric oxygen. This therapy has traditionally been used to treat divers who have decompression sickness, or “the bends.” It’s also being touted by some clinics as an effective treatment for long COVID.

A very small trial of 73 patients with long COVID, published in the journal Scientific Reports, found that those treated in a high-pressure oxygen system 5 days a week for 2 months showed improvements in brain fog, pain, energy, sleep, anxiety, and depression, compared with similar patients who got sham treatments. But larger studies are needed to show how well it works, notes Dr. Schamess.

“It’s very expensive – roughly $120 per session – and there just isn’t the evidence there to support its use,” he says.

In addition, the therapy itself carries risks, such as ear and sinus pain, middle ear injury, temporary vision changes, and, very rarely, lung collapse, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

One “particularly troubling” treatment being offered, says Kathleen Bell, MD, chair of the department of physical medicine and rehabilitation at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, is stem cell therapy. This therapy is still in its infancy, but it’s being marketed by some clinics as a way to prevent COVID-19 and also treat long-haul symptoms.

The FDA has issued advisories that there are no products approved to treat long COVID and recommends against their use, except in a clinical trial.

“There’s absolutely no regulation – you don’t know what you’re getting, and there’s no research to suggest this therapy even works,” says Dr. Bell. It’s also prohibitively expensive – one Cayman Islands–based company advertises its treatment for as much as $25,000.

Patients with long COVID are even traveling as far as Cyprus, Germany, and Switzerland for a procedure known as blood washing, in which large needles are inserted into veins to filter blood and remove lipids and inflammatory proteins, the British Medical Journal reported in July. Some patients are also prescribed blood thinners to remove microscopic blood clots that may contribute to long COVID. But this treatment is also expensive, with many people paying $10,000-$15,000 out of pocket, and there’s no published evidence to suggest it works, according to the BMJ.

It can be particularly hard to discern what may work and what’s unproven, since many primary care providers are themselves unfamiliar with even traditional long COVID treatments, Dr. Bell says.

Sorting through supplements

Yufang Lin, MD, an integrative specialist at the Cleveland Clinic, says many patients with long COVID enter her office with bags of supplements.

“There’s no data on them, and in large quantities, they may even be harmful,” she says.

Instead, she works closely with the Cleveland Clinic’s long COVID center to do a thorough workup of each patient, which often includes screening for certain nutritional deficiencies.

“Anecdotally, we do see many patients with long COVID who are deficient in these vitamins and minerals,” says Dr. Lin. “If someone is low, we will suggest the appropriate supplement. Otherwise, we work with them to institute some dietary changes.”

This usually involves a plant-based, anti-inflammatory eating pattern such as the Mediterranean diet, which is rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, fatty fish, and healthy fats such as olive oil and avocados.

Other supplements some doctors recommend for patients with long COVID are meant to treat inflammation, Dr. Bell says, although there’s not good evidence they work. One is the antioxidant coenzyme Q10.

But a small preprint study published in The Lancet, of 121 patients with long COVID who took 500 milligrams a day of coenzyme Q10 for 6 weeks saw no differences in recovery, compared with those who took a placebo. Because the study is still a preprint, it has not been peer-reviewed.

Another is probiotics. A small study, published in the journal Infectious Diseases Diagnosis & Treatment, found that a blend of five lactobacillus probiotics, along with a prebiotic called inulin, taken for 30 days, helped with long-term COVID symptoms such as coughing and fatigue. But larger studies need to be done to support their use.

One that may have more promise is omega-3 fatty acids. Like many other supplements, these may help with long COVID by easing inflammation, says Steven Flanagan, MD, a rehabilitation medicine specialist at NYU Langone who works with long COVID patients. Researchers at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, are studying whether a supplement can help patients who have lost their sense of taste or smell after an infection, but results aren’t yet available.

Among the few alternatives that have been shown to help patients are mindfulness-based therapies – in particular, mindfulness-based forms of exercise such as tai chi and qi gong may be helpful, as they combine a gentle workout with stress reduction.

“Both incorporate meditation, which helps not only to relieve some of the anxiety associated with long COVID but allows patients to redirect their thought process so that they can cope with symptoms better,” says Dr. Flanagan.

A 2022 study, published in BMJ Open, found that these two activities reduced inflammatory markers and improved respiratory muscle strength and function in patients recovering from COVID-19.

“I recommend these activities to all my long COVID patients, as it’s inexpensive and easy to find classes to do either at home or in their community,” he says. “Even if it doesn’t improve their long COVID symptoms, it has other benefits such as increased strength and flexibility that can boost their overall health.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Limiting antibiotic overprescription in pandemics: New guidelines

A statement by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, published online in Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, offers health care providers guidelines on how to prevent inappropriate antibiotic use in future pandemics and to avoid some of the negative scenarios that have been seen with COVID-19.

According to the U.S. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention,

The culprit might be the widespread antibiotic overprescription during the current pandemic. A 2022 meta-analysis revealed that in high-income countries, 58% of patients with COVID-19 were given antibiotics, whereas in lower- and middle-income countries, 89% of patients were put on such drugs. Some hospitals in Europe and the United States reported similarly elevated numbers, sometimes approaching 100%.

“We’ve lost control,” Natasha Pettit, PharmD, pharmacy director at University of Chicago Medicine, told this news organization. Dr. Pettit was not involved in the SHEA study. “Even if CDC didn’t come out with that data, I can tell you right now more of my time is spent trying to figure out how to manage these multi-drug–resistant infections, and we are running out of options for these patients,”

“Dealing with uncertainty, exhaustion, [and] critical illness in often young, otherwise healthy patients meant doctors wanted to do something for their patients,” said Tamar Barlam, MD, an infectious diseases expert at the Boston Medical Center who led the development of the SHEA white paper, in an interview.

That something often was a prescription for antibiotics, even without a clear indication that they were actually needed. A British study revealed that in times of pandemic uncertainty, clinicians often reached for antibiotics “just in case” and referred to conservative prescribing as “bravery.”

Studies have shown, however, that bacterial co-infections in COVID-19 are rare. A 2020 meta-analysis of 24 studies concluded that only 3.5% of patients had a bacterial co-infection on presentation, and 14.3% had a secondary infection. Similar patterns had previously been observed in other viral outbreaks. Research on MERS-CoV, for example, documented only 1% of patients with a bacterial co-infection on admission. During the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, that number was 12% of non–ICU hospitalized patients.

Yet, according to Dr. Pettit, even when such data became available, it didn’t necessarily change prescribing patterns. “Information was coming at us so quickly, I think the providers didn’t have a moment to see the data, to understand what it meant for their prescribing. Having external guidance earlier on would have been hugely helpful,” she told this news organization.

That’s where the newly published SHEA statement comes in: It outlines recommendations on when to prescribe antibiotics during a respiratory viral pandemic, what tests to order, and when to de-escalate or discontinue the treatment. These recommendations include, for instance, advice to not trust inflammatory markers as reliable indicators of bacterial or fungal infection and to not use procalcitonin routinely to aid in the decision to initiate antibiotics.

According to Dr. Barlam, one of the crucial lessons here is that if clinicians see patients with symptoms that are consistent with the current pandemic, they should trust their own impressions and avoid reaching for antimicrobials “just in case.”

Another important lesson is that antibiotic stewardship programs have a huge role to play during pandemics. They should not only monitor prescribing but also compile new information on bacterial co-infections as it gets released and make sure it reaches the clinicians in a clear form.

Evidence suggests that such programs and guidelines do work to limit unnecessary antibiotic use. In one medical center in Chicago, for example, before recommendations on when to initiate and discontinue antimicrobials were released, over 74% of COVID-19 patients received antibiotics. After guidelines were put in place, the use of such drugs fell to 42%.

Dr. Pettit believes, however, that it’s important not to leave each medical center to its own devices. “Hindsight is always twenty-twenty,” she said, “but I think it would be great that, if we start hearing about a pathogen that might lead to another pandemic, we should have a mechanism in place to call together an expert body to get guidance for how antimicrobial stewardship programs should get involved.”

One of the authors of the SHEA statement, Susan Seo, reports an investigator-initiated Merck grant on cost-effectiveness of letermovir in hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. Another author, Graeme Forrest, reports a clinical study grant from Regeneron for inpatient monoclonals against SARS-CoV-2. All other authors report no conflicts of interest. The study was independently supported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A statement by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, published online in Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, offers health care providers guidelines on how to prevent inappropriate antibiotic use in future pandemics and to avoid some of the negative scenarios that have been seen with COVID-19.

According to the U.S. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention,

The culprit might be the widespread antibiotic overprescription during the current pandemic. A 2022 meta-analysis revealed that in high-income countries, 58% of patients with COVID-19 were given antibiotics, whereas in lower- and middle-income countries, 89% of patients were put on such drugs. Some hospitals in Europe and the United States reported similarly elevated numbers, sometimes approaching 100%.

“We’ve lost control,” Natasha Pettit, PharmD, pharmacy director at University of Chicago Medicine, told this news organization. Dr. Pettit was not involved in the SHEA study. “Even if CDC didn’t come out with that data, I can tell you right now more of my time is spent trying to figure out how to manage these multi-drug–resistant infections, and we are running out of options for these patients,”

“Dealing with uncertainty, exhaustion, [and] critical illness in often young, otherwise healthy patients meant doctors wanted to do something for their patients,” said Tamar Barlam, MD, an infectious diseases expert at the Boston Medical Center who led the development of the SHEA white paper, in an interview.

That something often was a prescription for antibiotics, even without a clear indication that they were actually needed. A British study revealed that in times of pandemic uncertainty, clinicians often reached for antibiotics “just in case” and referred to conservative prescribing as “bravery.”

Studies have shown, however, that bacterial co-infections in COVID-19 are rare. A 2020 meta-analysis of 24 studies concluded that only 3.5% of patients had a bacterial co-infection on presentation, and 14.3% had a secondary infection. Similar patterns had previously been observed in other viral outbreaks. Research on MERS-CoV, for example, documented only 1% of patients with a bacterial co-infection on admission. During the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, that number was 12% of non–ICU hospitalized patients.

Yet, according to Dr. Pettit, even when such data became available, it didn’t necessarily change prescribing patterns. “Information was coming at us so quickly, I think the providers didn’t have a moment to see the data, to understand what it meant for their prescribing. Having external guidance earlier on would have been hugely helpful,” she told this news organization.

That’s where the newly published SHEA statement comes in: It outlines recommendations on when to prescribe antibiotics during a respiratory viral pandemic, what tests to order, and when to de-escalate or discontinue the treatment. These recommendations include, for instance, advice to not trust inflammatory markers as reliable indicators of bacterial or fungal infection and to not use procalcitonin routinely to aid in the decision to initiate antibiotics.

According to Dr. Barlam, one of the crucial lessons here is that if clinicians see patients with symptoms that are consistent with the current pandemic, they should trust their own impressions and avoid reaching for antimicrobials “just in case.”

Another important lesson is that antibiotic stewardship programs have a huge role to play during pandemics. They should not only monitor prescribing but also compile new information on bacterial co-infections as it gets released and make sure it reaches the clinicians in a clear form.

Evidence suggests that such programs and guidelines do work to limit unnecessary antibiotic use. In one medical center in Chicago, for example, before recommendations on when to initiate and discontinue antimicrobials were released, over 74% of COVID-19 patients received antibiotics. After guidelines were put in place, the use of such drugs fell to 42%.

Dr. Pettit believes, however, that it’s important not to leave each medical center to its own devices. “Hindsight is always twenty-twenty,” she said, “but I think it would be great that, if we start hearing about a pathogen that might lead to another pandemic, we should have a mechanism in place to call together an expert body to get guidance for how antimicrobial stewardship programs should get involved.”

One of the authors of the SHEA statement, Susan Seo, reports an investigator-initiated Merck grant on cost-effectiveness of letermovir in hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. Another author, Graeme Forrest, reports a clinical study grant from Regeneron for inpatient monoclonals against SARS-CoV-2. All other authors report no conflicts of interest. The study was independently supported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A statement by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, published online in Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, offers health care providers guidelines on how to prevent inappropriate antibiotic use in future pandemics and to avoid some of the negative scenarios that have been seen with COVID-19.

According to the U.S. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention,

The culprit might be the widespread antibiotic overprescription during the current pandemic. A 2022 meta-analysis revealed that in high-income countries, 58% of patients with COVID-19 were given antibiotics, whereas in lower- and middle-income countries, 89% of patients were put on such drugs. Some hospitals in Europe and the United States reported similarly elevated numbers, sometimes approaching 100%.

“We’ve lost control,” Natasha Pettit, PharmD, pharmacy director at University of Chicago Medicine, told this news organization. Dr. Pettit was not involved in the SHEA study. “Even if CDC didn’t come out with that data, I can tell you right now more of my time is spent trying to figure out how to manage these multi-drug–resistant infections, and we are running out of options for these patients,”

“Dealing with uncertainty, exhaustion, [and] critical illness in often young, otherwise healthy patients meant doctors wanted to do something for their patients,” said Tamar Barlam, MD, an infectious diseases expert at the Boston Medical Center who led the development of the SHEA white paper, in an interview.

That something often was a prescription for antibiotics, even without a clear indication that they were actually needed. A British study revealed that in times of pandemic uncertainty, clinicians often reached for antibiotics “just in case” and referred to conservative prescribing as “bravery.”

Studies have shown, however, that bacterial co-infections in COVID-19 are rare. A 2020 meta-analysis of 24 studies concluded that only 3.5% of patients had a bacterial co-infection on presentation, and 14.3% had a secondary infection. Similar patterns had previously been observed in other viral outbreaks. Research on MERS-CoV, for example, documented only 1% of patients with a bacterial co-infection on admission. During the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, that number was 12% of non–ICU hospitalized patients.

Yet, according to Dr. Pettit, even when such data became available, it didn’t necessarily change prescribing patterns. “Information was coming at us so quickly, I think the providers didn’t have a moment to see the data, to understand what it meant for their prescribing. Having external guidance earlier on would have been hugely helpful,” she told this news organization.

That’s where the newly published SHEA statement comes in: It outlines recommendations on when to prescribe antibiotics during a respiratory viral pandemic, what tests to order, and when to de-escalate or discontinue the treatment. These recommendations include, for instance, advice to not trust inflammatory markers as reliable indicators of bacterial or fungal infection and to not use procalcitonin routinely to aid in the decision to initiate antibiotics.

According to Dr. Barlam, one of the crucial lessons here is that if clinicians see patients with symptoms that are consistent with the current pandemic, they should trust their own impressions and avoid reaching for antimicrobials “just in case.”

Another important lesson is that antibiotic stewardship programs have a huge role to play during pandemics. They should not only monitor prescribing but also compile new information on bacterial co-infections as it gets released and make sure it reaches the clinicians in a clear form.

Evidence suggests that such programs and guidelines do work to limit unnecessary antibiotic use. In one medical center in Chicago, for example, before recommendations on when to initiate and discontinue antimicrobials were released, over 74% of COVID-19 patients received antibiotics. After guidelines were put in place, the use of such drugs fell to 42%.

Dr. Pettit believes, however, that it’s important not to leave each medical center to its own devices. “Hindsight is always twenty-twenty,” she said, “but I think it would be great that, if we start hearing about a pathogen that might lead to another pandemic, we should have a mechanism in place to call together an expert body to get guidance for how antimicrobial stewardship programs should get involved.”

One of the authors of the SHEA statement, Susan Seo, reports an investigator-initiated Merck grant on cost-effectiveness of letermovir in hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. Another author, Graeme Forrest, reports a clinical study grant from Regeneron for inpatient monoclonals against SARS-CoV-2. All other authors report no conflicts of interest. The study was independently supported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM INFECTION CONTROL & HOSPITAL EPIDEMIOLOGY

COVID vaccination does not appear to worsen symptoms of Parkinson’s disease

Nonmotor symptoms seemed to improve after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, although the investigators could not verify a causal relationship.

Vaccination programs should continue for patients with Parkinson’s disease, they said, reporting their clinical results at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

The International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society has recommended vaccining patients with Parkinson’s disease. “All approved mRNA-based and viral vector vaccines are not expected to interact with Parkinson’s disease, but patients [still] report concern with regard to the benefits, risks, and safeness in Parkinson’s disease,” Mayela Rodríguez-Violante, MD, MSc, and colleagues wrote in an abstract of their findings.

Social isolation may be contributing to these beliefs and concerns, though this is inconclusive.

Investigators from Mexico City conducted a retrospective study of patients with Parkinson’s disease to see how COVID-19 vaccination affected motor and nonmotor symptoms. They enlisted 60 patients (66.7% were male; aged 65.7 ± 11.35 years) who received either a vector-viral vaccine (Vaxzevria Coronavirus) or an mRNA vaccine (BNT162b2).

A Wilcoxon signed-rank test assessed scale differences before and after vaccination, measuring motor involvement (Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale), nonmotor involvement (Non-Motor Rating Scale [NMSS]), cognitive impairment (Montreal Cognitive Assessment), and quality of life (8-item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire index).

Investigators found no significant difference between scales, although they did notice a marked improvement in non-motor symptoms.

“The main takeaway is that vaccination against COVID-19 does not appear to worsen motor or nonmotor symptoms in persons with Parkinson’s disease. The benefits outweigh the risks,” said Dr. Rodríguez-Violante, the study’s lead author and a movement disorder specialist at the National Institute of Neurology and Neurosurgery, Mexico City.

Next steps are to increase the sample size to see if it’s possible to have a similar number in terms of type of vaccine, said Dr. Rodríguez-Violante. “Also, the data presented refers to primary series doses so booster effects will also be studied.”

Few studies have looked at vaccines and their possible effects on this patient population. However, a 2021 study of 181 patients with Parkinson’s disease reported that 2 (1.1%) had adverse effects after receiving the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine. One of the patients, a 61-year-old woman with a decade-long history of Parkinson’s disease, developed severe, continuous, generalized dyskinesia 6 hours after a first dose of vaccine. The second patient was 79 years old and had Parkinson’s disease for 5 years. She developed fever, confusion, delusions, and continuous severe dyskinesia for 3 days following her vaccination.

“This highlights that there is a variability in the response triggered by the vaccine that might likely depend on individual immunological profiles … clinicians should be aware of this possibility and monitor their patients after they receive their vaccination,” Roberto Erro, MD, PhD and colleagues wrote in the Movement Disorders journal.

Nonmotor symptoms seemed to improve after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, although the investigators could not verify a causal relationship.

Vaccination programs should continue for patients with Parkinson’s disease, they said, reporting their clinical results at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

The International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society has recommended vaccining patients with Parkinson’s disease. “All approved mRNA-based and viral vector vaccines are not expected to interact with Parkinson’s disease, but patients [still] report concern with regard to the benefits, risks, and safeness in Parkinson’s disease,” Mayela Rodríguez-Violante, MD, MSc, and colleagues wrote in an abstract of their findings.

Social isolation may be contributing to these beliefs and concerns, though this is inconclusive.

Investigators from Mexico City conducted a retrospective study of patients with Parkinson’s disease to see how COVID-19 vaccination affected motor and nonmotor symptoms. They enlisted 60 patients (66.7% were male; aged 65.7 ± 11.35 years) who received either a vector-viral vaccine (Vaxzevria Coronavirus) or an mRNA vaccine (BNT162b2).

A Wilcoxon signed-rank test assessed scale differences before and after vaccination, measuring motor involvement (Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale), nonmotor involvement (Non-Motor Rating Scale [NMSS]), cognitive impairment (Montreal Cognitive Assessment), and quality of life (8-item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire index).

Investigators found no significant difference between scales, although they did notice a marked improvement in non-motor symptoms.

“The main takeaway is that vaccination against COVID-19 does not appear to worsen motor or nonmotor symptoms in persons with Parkinson’s disease. The benefits outweigh the risks,” said Dr. Rodríguez-Violante, the study’s lead author and a movement disorder specialist at the National Institute of Neurology and Neurosurgery, Mexico City.

Next steps are to increase the sample size to see if it’s possible to have a similar number in terms of type of vaccine, said Dr. Rodríguez-Violante. “Also, the data presented refers to primary series doses so booster effects will also be studied.”

Few studies have looked at vaccines and their possible effects on this patient population. However, a 2021 study of 181 patients with Parkinson’s disease reported that 2 (1.1%) had adverse effects after receiving the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine. One of the patients, a 61-year-old woman with a decade-long history of Parkinson’s disease, developed severe, continuous, generalized dyskinesia 6 hours after a first dose of vaccine. The second patient was 79 years old and had Parkinson’s disease for 5 years. She developed fever, confusion, delusions, and continuous severe dyskinesia for 3 days following her vaccination.

“This highlights that there is a variability in the response triggered by the vaccine that might likely depend on individual immunological profiles … clinicians should be aware of this possibility and monitor their patients after they receive their vaccination,” Roberto Erro, MD, PhD and colleagues wrote in the Movement Disorders journal.

Nonmotor symptoms seemed to improve after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, although the investigators could not verify a causal relationship.

Vaccination programs should continue for patients with Parkinson’s disease, they said, reporting their clinical results at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

The International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society has recommended vaccining patients with Parkinson’s disease. “All approved mRNA-based and viral vector vaccines are not expected to interact with Parkinson’s disease, but patients [still] report concern with regard to the benefits, risks, and safeness in Parkinson’s disease,” Mayela Rodríguez-Violante, MD, MSc, and colleagues wrote in an abstract of their findings.

Social isolation may be contributing to these beliefs and concerns, though this is inconclusive.

Investigators from Mexico City conducted a retrospective study of patients with Parkinson’s disease to see how COVID-19 vaccination affected motor and nonmotor symptoms. They enlisted 60 patients (66.7% were male; aged 65.7 ± 11.35 years) who received either a vector-viral vaccine (Vaxzevria Coronavirus) or an mRNA vaccine (BNT162b2).

A Wilcoxon signed-rank test assessed scale differences before and after vaccination, measuring motor involvement (Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale), nonmotor involvement (Non-Motor Rating Scale [NMSS]), cognitive impairment (Montreal Cognitive Assessment), and quality of life (8-item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire index).

Investigators found no significant difference between scales, although they did notice a marked improvement in non-motor symptoms.

“The main takeaway is that vaccination against COVID-19 does not appear to worsen motor or nonmotor symptoms in persons with Parkinson’s disease. The benefits outweigh the risks,” said Dr. Rodríguez-Violante, the study’s lead author and a movement disorder specialist at the National Institute of Neurology and Neurosurgery, Mexico City.

Next steps are to increase the sample size to see if it’s possible to have a similar number in terms of type of vaccine, said Dr. Rodríguez-Violante. “Also, the data presented refers to primary series doses so booster effects will also be studied.”

Few studies have looked at vaccines and their possible effects on this patient population. However, a 2021 study of 181 patients with Parkinson’s disease reported that 2 (1.1%) had adverse effects after receiving the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine. One of the patients, a 61-year-old woman with a decade-long history of Parkinson’s disease, developed severe, continuous, generalized dyskinesia 6 hours after a first dose of vaccine. The second patient was 79 years old and had Parkinson’s disease for 5 years. She developed fever, confusion, delusions, and continuous severe dyskinesia for 3 days following her vaccination.

“This highlights that there is a variability in the response triggered by the vaccine that might likely depend on individual immunological profiles … clinicians should be aware of this possibility and monitor their patients after they receive their vaccination,” Roberto Erro, MD, PhD and colleagues wrote in the Movement Disorders journal.

FROM MDS 2022

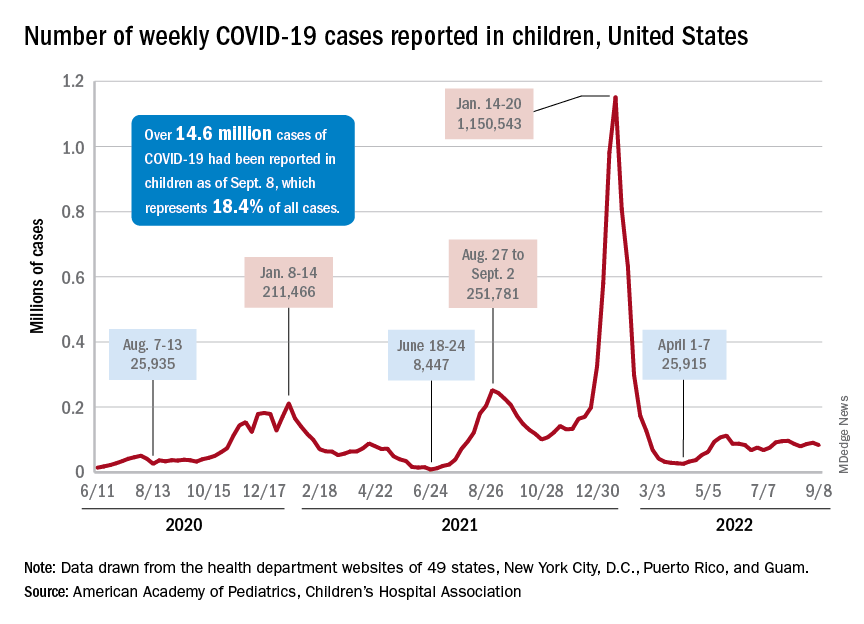

Children and COVID: Weekly cases drop to lowest level since April

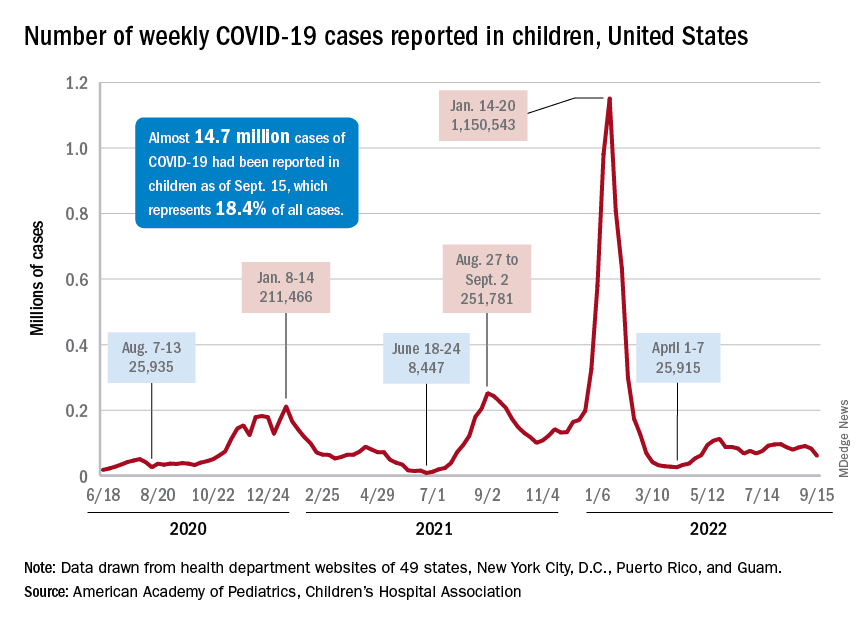

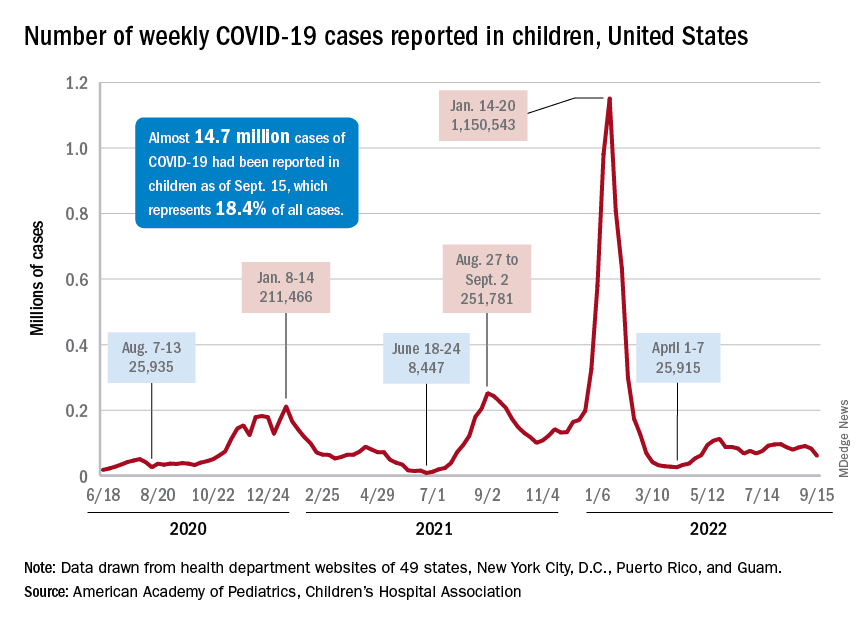

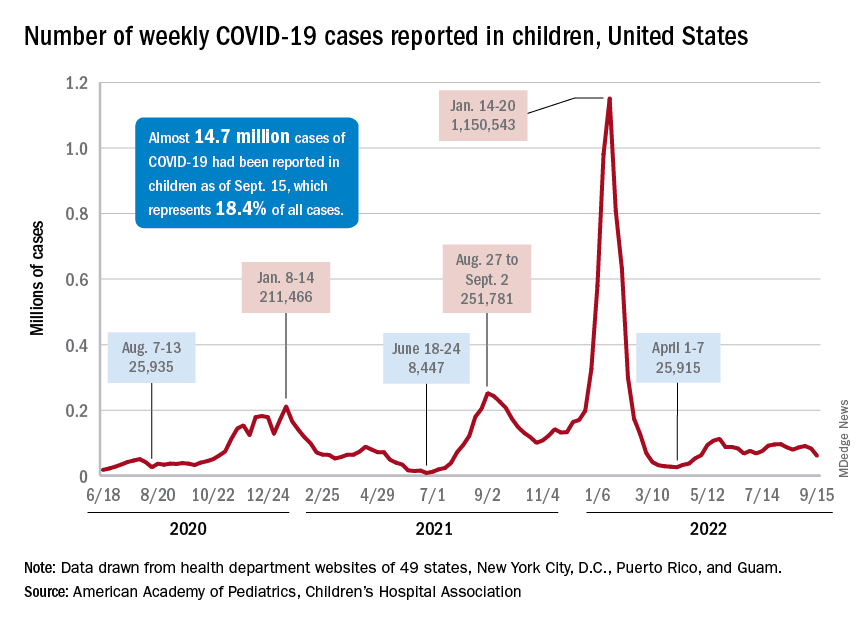

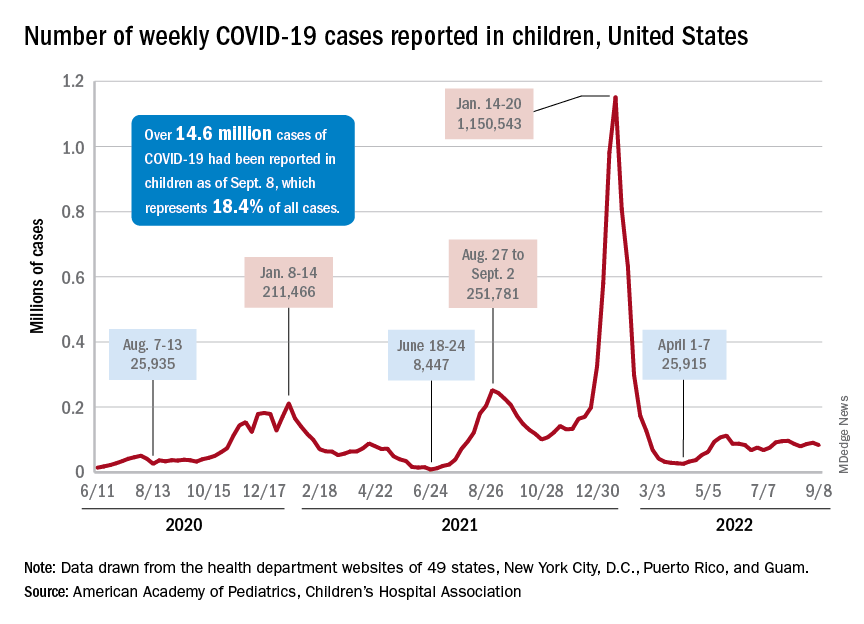

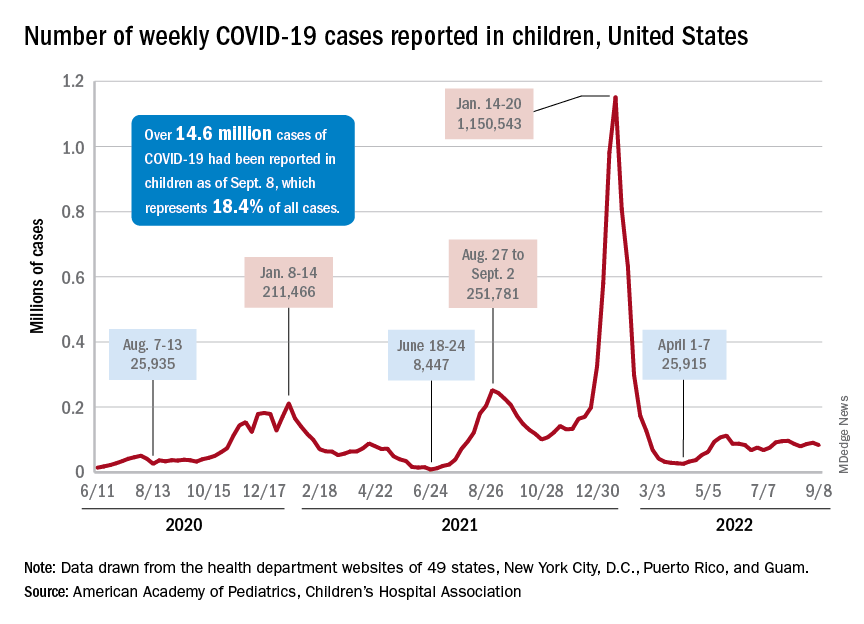

A hefty decline in new COVID-19 cases among children resulted in the lowest weekly total since late April, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, making for 2 consecutive weeks of declines after almost 91,000 cases were recorded for the week ending Sept. 1, the AAP and CHA said in their latest COVID report of state-level data.

The last time the weekly count was under 60,000 came during the week of April 22-28, when 53,000 were reported by state and territorial health departments in the midst of a 7-week stretch of rising cases. Since that streak ended in mid-May, however, “reported weekly cases have plateaued, fluctuating between a low, now of 60,300 cases and a high of about 112,000,” the AAP noted.

Emergency department visits and hospital admissions, which showed less fluctuation over the summer and more steady rise and fall, have both dropped in recent weeks and are now approaching late May/early June rates, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

On Sept. 15, for example, ED visits for children under 12 years with diagnosed COVID were just 2.2% of all visits, lower than at any time since May 19 and down from a summer high of 6.8% in late July. Hospital admissions for children aged 0-17 years also rose steadily through June and July, reaching 0.46 per 100,000 population on July 30, but have since slipped to 0.29 per 100,000 as of Sept. 17, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

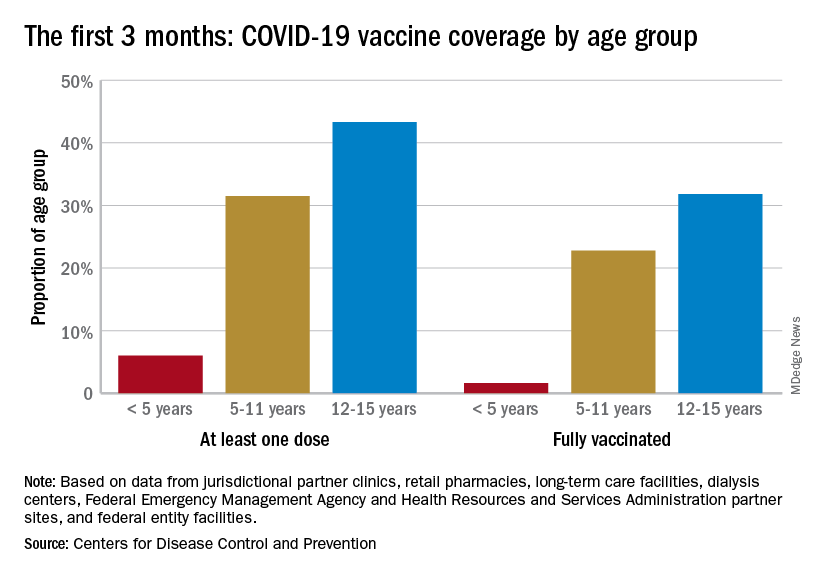

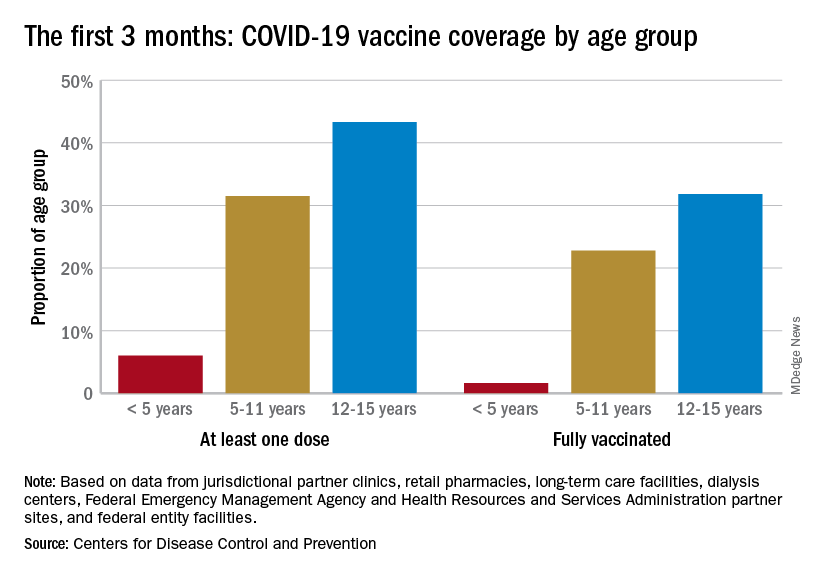

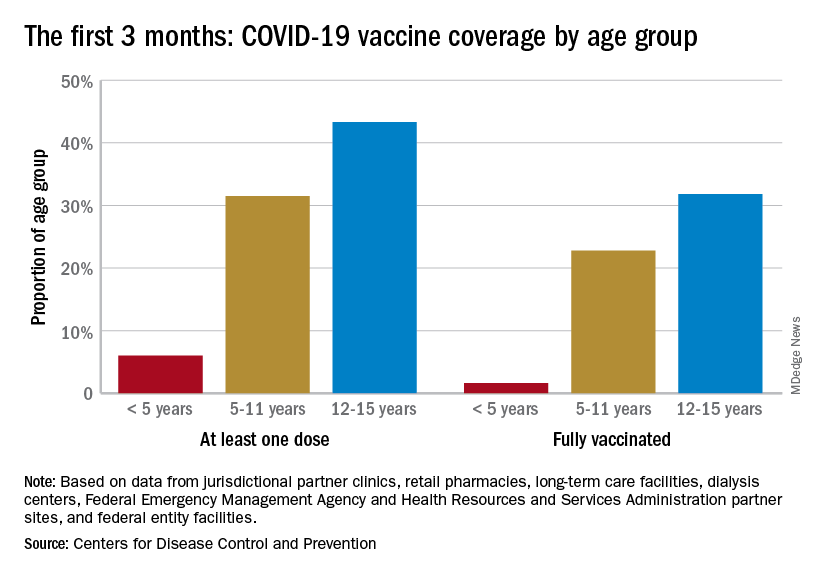

Vaccination continues to be a tough sell

Vaccination activity among the most recently eligible age group, in the meantime, remains tepid. Just 6.0% of children under age 5 had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine as of Sept. 13, about 3 months since its final approval in June, and 1.6% were fully vaccinated. For the two older groups of children with separate vaccine approvals, 31.5% of those aged 5-11 years and 43.3% of those aged 12-15 had received at least one dose 3 months after their vaccinations began, the CDC data show.

In the 2 weeks ending Sept. 14, almost 59,000 children under age 5 received their initial COVID-19 vaccine dose, as did 28,000 5- to 11-year-olds and 14,000 children aged 12-17. Children under age 5 years represented almost 20% of all Americans getting a first dose during Sept. 1-14, compared with 9.7% for those aged 5-11 and 4.8% for the 12- to 17-year-olds, the CDC said.

At the state level, children under age 5 years in the District of Columbia, where 28% have received at least one dose, and Vermont, at 24%, are the most likely to be vaccinated. The states with the lowest rates in this age group are Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi, all of which are at 2%. Vermont and D.C. have the highest rates for ages 5-11 at 70% each, and Alabama (17%) is the lowest, while D.C. (100%), Rhode Island (99%), and Massachusetts (99%) are highest for children aged 12-17 years and Wyoming (41%) is the lowest, the AAP said in a separate report.

A hefty decline in new COVID-19 cases among children resulted in the lowest weekly total since late April, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, making for 2 consecutive weeks of declines after almost 91,000 cases were recorded for the week ending Sept. 1, the AAP and CHA said in their latest COVID report of state-level data.

The last time the weekly count was under 60,000 came during the week of April 22-28, when 53,000 were reported by state and territorial health departments in the midst of a 7-week stretch of rising cases. Since that streak ended in mid-May, however, “reported weekly cases have plateaued, fluctuating between a low, now of 60,300 cases and a high of about 112,000,” the AAP noted.

Emergency department visits and hospital admissions, which showed less fluctuation over the summer and more steady rise and fall, have both dropped in recent weeks and are now approaching late May/early June rates, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

On Sept. 15, for example, ED visits for children under 12 years with diagnosed COVID were just 2.2% of all visits, lower than at any time since May 19 and down from a summer high of 6.8% in late July. Hospital admissions for children aged 0-17 years also rose steadily through June and July, reaching 0.46 per 100,000 population on July 30, but have since slipped to 0.29 per 100,000 as of Sept. 17, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Vaccination continues to be a tough sell

Vaccination activity among the most recently eligible age group, in the meantime, remains tepid. Just 6.0% of children under age 5 had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine as of Sept. 13, about 3 months since its final approval in June, and 1.6% were fully vaccinated. For the two older groups of children with separate vaccine approvals, 31.5% of those aged 5-11 years and 43.3% of those aged 12-15 had received at least one dose 3 months after their vaccinations began, the CDC data show.

In the 2 weeks ending Sept. 14, almost 59,000 children under age 5 received their initial COVID-19 vaccine dose, as did 28,000 5- to 11-year-olds and 14,000 children aged 12-17. Children under age 5 years represented almost 20% of all Americans getting a first dose during Sept. 1-14, compared with 9.7% for those aged 5-11 and 4.8% for the 12- to 17-year-olds, the CDC said.

At the state level, children under age 5 years in the District of Columbia, where 28% have received at least one dose, and Vermont, at 24%, are the most likely to be vaccinated. The states with the lowest rates in this age group are Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi, all of which are at 2%. Vermont and D.C. have the highest rates for ages 5-11 at 70% each, and Alabama (17%) is the lowest, while D.C. (100%), Rhode Island (99%), and Massachusetts (99%) are highest for children aged 12-17 years and Wyoming (41%) is the lowest, the AAP said in a separate report.

A hefty decline in new COVID-19 cases among children resulted in the lowest weekly total since late April, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, making for 2 consecutive weeks of declines after almost 91,000 cases were recorded for the week ending Sept. 1, the AAP and CHA said in their latest COVID report of state-level data.

The last time the weekly count was under 60,000 came during the week of April 22-28, when 53,000 were reported by state and territorial health departments in the midst of a 7-week stretch of rising cases. Since that streak ended in mid-May, however, “reported weekly cases have plateaued, fluctuating between a low, now of 60,300 cases and a high of about 112,000,” the AAP noted.

Emergency department visits and hospital admissions, which showed less fluctuation over the summer and more steady rise and fall, have both dropped in recent weeks and are now approaching late May/early June rates, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

On Sept. 15, for example, ED visits for children under 12 years with diagnosed COVID were just 2.2% of all visits, lower than at any time since May 19 and down from a summer high of 6.8% in late July. Hospital admissions for children aged 0-17 years also rose steadily through June and July, reaching 0.46 per 100,000 population on July 30, but have since slipped to 0.29 per 100,000 as of Sept. 17, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Vaccination continues to be a tough sell

Vaccination activity among the most recently eligible age group, in the meantime, remains tepid. Just 6.0% of children under age 5 had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine as of Sept. 13, about 3 months since its final approval in June, and 1.6% were fully vaccinated. For the two older groups of children with separate vaccine approvals, 31.5% of those aged 5-11 years and 43.3% of those aged 12-15 had received at least one dose 3 months after their vaccinations began, the CDC data show.

In the 2 weeks ending Sept. 14, almost 59,000 children under age 5 received their initial COVID-19 vaccine dose, as did 28,000 5- to 11-year-olds and 14,000 children aged 12-17. Children under age 5 years represented almost 20% of all Americans getting a first dose during Sept. 1-14, compared with 9.7% for those aged 5-11 and 4.8% for the 12- to 17-year-olds, the CDC said.

At the state level, children under age 5 years in the District of Columbia, where 28% have received at least one dose, and Vermont, at 24%, are the most likely to be vaccinated. The states with the lowest rates in this age group are Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi, all of which are at 2%. Vermont and D.C. have the highest rates for ages 5-11 at 70% each, and Alabama (17%) is the lowest, while D.C. (100%), Rhode Island (99%), and Massachusetts (99%) are highest for children aged 12-17 years and Wyoming (41%) is the lowest, the AAP said in a separate report.

COVID-19 linked to increased Alzheimer’s risk

The study of more than 6 million people aged 65 years or older found a 50%-80% increased risk for AD in the year after COVID-19; the risk was especially high for women older than 85 years.

However, the investigators were quick to point out that the observational retrospective study offers no evidence that COVID-19 causes AD. There could be a viral etiology at play, or the connection could be related to inflammation in neural tissue from the SARS-CoV-2 infection. Or it could simply be that exposure to the health care system for COVID-19 increased the odds of detection of existing undiagnosed AD cases.

Whatever the case, these findings point to a potential spike in AD cases, which is a cause for concern, study investigator Pamela Davis, MD, PhD, a professor in the Center for Community Health Integration at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, said in an interview.

“COVID may be giving us a legacy of ongoing medical difficulties,” Dr. Davis said. “We were already concerned about having a very large care burden and cost burden from Alzheimer’s disease. If this is another burden that’s increased by COVID, this is something we’re really going to have to prepare for.”

The findings were published online in Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Increased risk

Earlier research points to a potential link between COVID-19 and increased risk for AD and Parkinson’s disease.

For the current study, researchers analyzed anonymous electronic health records of 6.2 million adults aged 65 years or older who received medical treatment between February 2020 and May 2021 and had no prior diagnosis of AD. The database includes information on almost 30% of the entire U.S. population.

Overall, there were 410,748 cases of COVID-19 during the study period.

The overall risk for new diagnosis of AD in the COVID-19 cohort was close to double that of those who did not have COVID-19 (0.68% vs. 0.35%, respectively).

After propensity-score matching, those who have had COVID-19 had a significantly higher risk for an AD diagnosis compared with those who were not infected (hazard ratio [HR], 1.69; 95% confidence interval [CI],1.53-1.72).

Risk for AD was elevated in all age groups, regardless of gender or ethnicity. Researchers did not collect data on COVID-19 severity, and the medical codes for long COVID were not published until after the study had ended.

Those with the highest risk were individuals older than 85 years (HR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.73-2.07) and women (HR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.69-1.97).

“We expected to see some impact, but I was surprised that it was as potent as it was,” Dr. Davis said.

Association, not causation

Heather Snyder, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association vice president of medical and scientific relations, who commented on the findings for this article, called the study interesting but emphasized caution in interpreting the results.

“Because this study only showed an association through medical records, we cannot know what the underlying mechanisms driving this association are without more research,” Dr. Snyder said. “If you have had COVID-19, it doesn’t mean you’re going to get dementia. But if you have had COVID-19 and are experiencing long-term symptoms including cognitive difficulties, talk to your doctor.”

Dr. Davis agreed, noting that this type of study offers information on association, but not causation. “I do think that this makes it imperative that we continue to follow the population for what’s going on in various neurodegenerative diseases,” Dr. Davis said.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Aging, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland, and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Synder reports no relevant financial conflicts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study of more than 6 million people aged 65 years or older found a 50%-80% increased risk for AD in the year after COVID-19; the risk was especially high for women older than 85 years.

However, the investigators were quick to point out that the observational retrospective study offers no evidence that COVID-19 causes AD. There could be a viral etiology at play, or the connection could be related to inflammation in neural tissue from the SARS-CoV-2 infection. Or it could simply be that exposure to the health care system for COVID-19 increased the odds of detection of existing undiagnosed AD cases.

Whatever the case, these findings point to a potential spike in AD cases, which is a cause for concern, study investigator Pamela Davis, MD, PhD, a professor in the Center for Community Health Integration at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, said in an interview.

“COVID may be giving us a legacy of ongoing medical difficulties,” Dr. Davis said. “We were already concerned about having a very large care burden and cost burden from Alzheimer’s disease. If this is another burden that’s increased by COVID, this is something we’re really going to have to prepare for.”

The findings were published online in Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Increased risk

Earlier research points to a potential link between COVID-19 and increased risk for AD and Parkinson’s disease.

For the current study, researchers analyzed anonymous electronic health records of 6.2 million adults aged 65 years or older who received medical treatment between February 2020 and May 2021 and had no prior diagnosis of AD. The database includes information on almost 30% of the entire U.S. population.

Overall, there were 410,748 cases of COVID-19 during the study period.

The overall risk for new diagnosis of AD in the COVID-19 cohort was close to double that of those who did not have COVID-19 (0.68% vs. 0.35%, respectively).

After propensity-score matching, those who have had COVID-19 had a significantly higher risk for an AD diagnosis compared with those who were not infected (hazard ratio [HR], 1.69; 95% confidence interval [CI],1.53-1.72).

Risk for AD was elevated in all age groups, regardless of gender or ethnicity. Researchers did not collect data on COVID-19 severity, and the medical codes for long COVID were not published until after the study had ended.

Those with the highest risk were individuals older than 85 years (HR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.73-2.07) and women (HR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.69-1.97).

“We expected to see some impact, but I was surprised that it was as potent as it was,” Dr. Davis said.

Association, not causation

Heather Snyder, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association vice president of medical and scientific relations, who commented on the findings for this article, called the study interesting but emphasized caution in interpreting the results.

“Because this study only showed an association through medical records, we cannot know what the underlying mechanisms driving this association are without more research,” Dr. Snyder said. “If you have had COVID-19, it doesn’t mean you’re going to get dementia. But if you have had COVID-19 and are experiencing long-term symptoms including cognitive difficulties, talk to your doctor.”

Dr. Davis agreed, noting that this type of study offers information on association, but not causation. “I do think that this makes it imperative that we continue to follow the population for what’s going on in various neurodegenerative diseases,” Dr. Davis said.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Aging, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland, and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Synder reports no relevant financial conflicts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study of more than 6 million people aged 65 years or older found a 50%-80% increased risk for AD in the year after COVID-19; the risk was especially high for women older than 85 years.

However, the investigators were quick to point out that the observational retrospective study offers no evidence that COVID-19 causes AD. There could be a viral etiology at play, or the connection could be related to inflammation in neural tissue from the SARS-CoV-2 infection. Or it could simply be that exposure to the health care system for COVID-19 increased the odds of detection of existing undiagnosed AD cases.

Whatever the case, these findings point to a potential spike in AD cases, which is a cause for concern, study investigator Pamela Davis, MD, PhD, a professor in the Center for Community Health Integration at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, said in an interview.

“COVID may be giving us a legacy of ongoing medical difficulties,” Dr. Davis said. “We were already concerned about having a very large care burden and cost burden from Alzheimer’s disease. If this is another burden that’s increased by COVID, this is something we’re really going to have to prepare for.”

The findings were published online in Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Increased risk

Earlier research points to a potential link between COVID-19 and increased risk for AD and Parkinson’s disease.

For the current study, researchers analyzed anonymous electronic health records of 6.2 million adults aged 65 years or older who received medical treatment between February 2020 and May 2021 and had no prior diagnosis of AD. The database includes information on almost 30% of the entire U.S. population.

Overall, there were 410,748 cases of COVID-19 during the study period.

The overall risk for new diagnosis of AD in the COVID-19 cohort was close to double that of those who did not have COVID-19 (0.68% vs. 0.35%, respectively).

After propensity-score matching, those who have had COVID-19 had a significantly higher risk for an AD diagnosis compared with those who were not infected (hazard ratio [HR], 1.69; 95% confidence interval [CI],1.53-1.72).

Risk for AD was elevated in all age groups, regardless of gender or ethnicity. Researchers did not collect data on COVID-19 severity, and the medical codes for long COVID were not published until after the study had ended.

Those with the highest risk were individuals older than 85 years (HR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.73-2.07) and women (HR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.69-1.97).

“We expected to see some impact, but I was surprised that it was as potent as it was,” Dr. Davis said.

Association, not causation

Heather Snyder, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association vice president of medical and scientific relations, who commented on the findings for this article, called the study interesting but emphasized caution in interpreting the results.

“Because this study only showed an association through medical records, we cannot know what the underlying mechanisms driving this association are without more research,” Dr. Snyder said. “If you have had COVID-19, it doesn’t mean you’re going to get dementia. But if you have had COVID-19 and are experiencing long-term symptoms including cognitive difficulties, talk to your doctor.”

Dr. Davis agreed, noting that this type of study offers information on association, but not causation. “I do think that this makes it imperative that we continue to follow the population for what’s going on in various neurodegenerative diseases,” Dr. Davis said.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Aging, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland, and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Synder reports no relevant financial conflicts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

People of color bearing brunt of long COVID, doctors say

From the earliest days of the COVID-19 pandemic, people of color have been hardest hit by the virus. Now, many doctors and researchers are seeing big disparities come about in who gets care for long COVID.

Long COVID can affect patients from all walks of life. said Alba Miranda Azola, MD, codirector of the post–acute COVID-19 team at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Non-White patients are more apt to lack access to primary care, face insurance barriers to see specialists, struggle with time off work or transportation for appointments, and have financial barriers to care as copayments for therapy pile up.

“We are getting a very skewed population of Caucasian wealthy people who are coming to our clinic because they have the ability to access care, they have good insurance, and they are looking on the internet and find us,” Dr. Azola said.

This mix of patients at Dr. Azola’s clinic is out of step with the demographics of Baltimore, where the majority of residents are Black, half of them earn less than $52,000 a year, and one in five live in poverty. And this isn’t unique to Hopkins. Many of the dozens of specialized long COVID clinics that have cropped up around the country are also seeing an unequal share of affluent White patients, experts say.

It’s also a patient mix that very likely doesn’t reflect who is most apt to have long COVID.

During the pandemic, people who identified as Black, Hispanic, American Indian, or Alaska Native were more likely to be diagnosed with COVID than people who identified as White, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These people of color were also at least twice as likely to be hospitalized with severe infections, and at least 70% more likely to die.

“Data repeatedly show the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minority populations, as well as other population groups such as people living in rural or frontier areas, people experiencing homelessness, essential and frontline workers, people with disabilities, people with substance use disorders, people who are incarcerated, and non–U.S.-born persons,” John Brooks, MD, chief medical officer for COVID-19 response at the CDC, said during testimony before the U.S. House Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Health in April 2021.

“While we do not yet have clear data on the impact of post-COVID conditions on racial and ethnic minority populations and other disadvantaged communities, we do believe that they are likely to be disproportionately impacted ... and less likely to be able to access health care services,” Dr. Brooks said at the time.

The picture that’s emerging of long COVID suggests that the condition impacts about one in five adults. It’s more common among Hispanic adults than among people who identify as Black, Asian, or White. It’s also more common among those who identify as other races or multiple races, according survey data collected by the CDC.

It’s hard to say how accurate this snapshot is because researchers need to do a better job of identifying and following people with long COVID, said Monica Verduzco-Gutierrez, MD, chair of rehabilitation medicine and director of the COVID-19 Recovery Clinic at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. A major limitation of surveys like the ones done by the CDC to monitor long COVID is that only people who realize they have the condition can get counted.

“Some people from historically marginalized groups may have less health literacy to know about impacts of long COVID,” she said.

Lack of awareness may keep people with persistent symptoms from seeking medical attention, leaving many long COVID cases undiagnosed.

When some patients do seek help, their complaints may not be acknowledged or understood. Often, cultural bias or structural racism can get in the way of diagnosis and treatment, Dr. Azola said.

“I hate to say this, but there is probably bias among providers,” she said. “For example, I am Puerto Rican, and the way we describe symptoms as Latinos may sound exaggerated or may be brushed aside or lost in translation. I think we miss a lot of patients being diagnosed or referred to specialists because the primary care provider they see maybe leans into this cultural bias of thinking this is just a Latino being dramatic.”

There’s some evidence that treatment for long COVID may differ by race even when symptoms are similar. One study of more than 400,000 patients, for example, found no racial differences in the proportion of people who have six common long COVID symptoms: shortness of breath, fatigue, weakness, pain, trouble with thinking skills, and a hard time getting around. Despite this, Black patients were significantly less likely to receive outpatient rehabilitation services to treat these symptoms.

Benjamin Abramoff, MD, who leads the long COVID collaborative for the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, draws parallels between what happens with long COVID to another common health problem often undertreated among patients of color: pain. With both long COVID and chronic pain, one major barrier to care is “just getting taken seriously by providers,” he said.

“There is significant evidence that racial bias has led to less prescription of pain medications to people of color,” Dr. Abramoff said. “Just as pain can be difficult to get objective measures of, long COVID symptoms can also be difficult to objectively measure and requires trust between the provider and patient.”

Geography can be another barrier to care, said Aaron Friedberg, MD, clinical colead of the post-COVID recovery program at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus. Many communities hardest hit by COVID – particularly in high-poverty urban neighborhoods – have long had limited access to care. The pandemic worsened staffing shortages at many hospitals and clinics in these communities, leaving patients even fewer options close to home.