User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Low-calorie tastes sweeter with a little salt

Low-calorie tastes sweeter with a little salt

Diet and sugar-free foods and drinks seem like a good idea, but it’s hard to get past that strange aftertaste, right? It’s the calling card for the noncaloric aspartame- and stevia-containing sweeteners that we consume to make us feel like we can have the best of both worlds.

That weird lingering taste can be a total turn-off for some (raises hand), but researchers have found an almost facepalm solution to the not-so-sweet problem, and it’s salt.

Now, the concept of sweet and salty is not a far-fetched partnership when it comes to snack consumption (try M&Ms in your popcorn). The researchers at Almendra, a manufacturer of stevia sweeteners, put that iconic flavor pair to the test by adding mineral salts that have some nutritional value to lessen the effect of a stevia compound, rebaudioside A, found in noncaloric sweeteners.

The researchers added in magnesium chloride, calcium chloride, and potassium chloride separately to lessen rebaudioside A’s intensity, but they needed so much salt that it killed the sweet taste completely. A blend of the three mineral salts, however, reduced the lingering taste by 79% and improved the real sugar-like taste. The researchers tried this blend in reduced-calorie orange juice and a citrus-flavored soft drink, improving the taste in both.

The salty and sweet match comes in for the win once again. This time helping against the fight of obesity instead of making it worse.

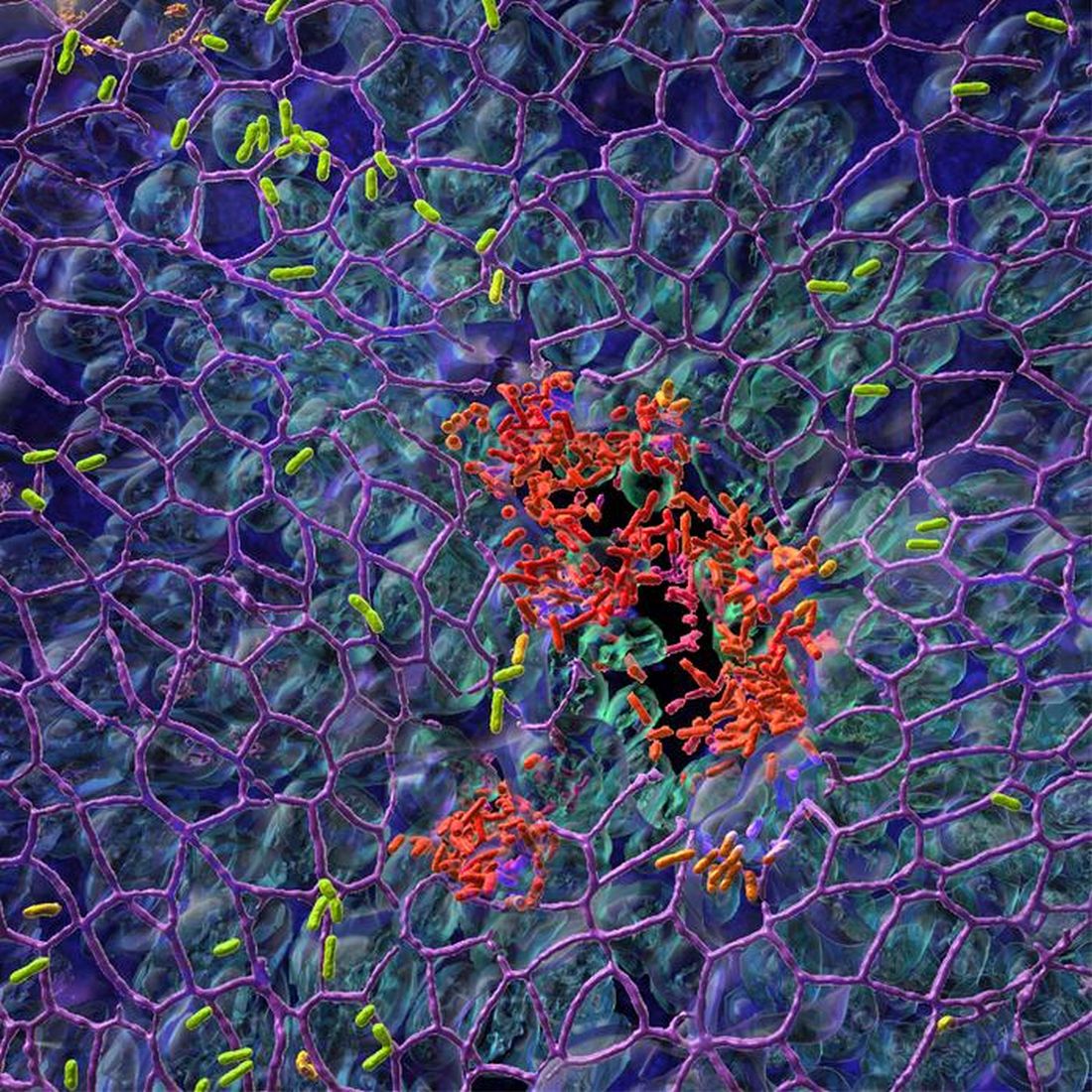

Pseudomonas’ Achilles’ heel is more of an Achilles’ genetic switch

Today, on the long-awaited return of “Bacteria vs. the World,” we meet one of the rock stars of infectious disease.

LOTME: Through the use of imaginary technology, we’re talking to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Thanks for joining us on such short notice, after Neisseria gonorrhoeae canceled at the last minute.

P. aeruginosa: No problem. I think we can all guess what that little devil is up to.

LOTME: Bacterial resistance to antibiotics is a huge problem for our species. What makes you so hard to fight?

P. aeruginosa: We’ve been trying to keep that a secret, actually, but now that researchers in Switzerland and Denmark seem to have figured it out, I guess it’s okay for me to spill the beans.

LOTME: Beans? What do beans have to do with it?

P. aeruginosa: Nothing, it’s just a colloquial expression that means I’m sharing previously private information.

LOTME: Sure, we knew that. Please, continue your spilling.

P. aeruginosa: The secret is … Well, let’s just say we were a little worried when the Clash released “Should I Stay or Should I Go” back in the 1980s.

LOTME: The Clash? Now we’re really confused.

P. aeruginosa: The answer to their question, “Should I stay or should I go? is yes. Successful invasion of a human is all about division of labor. “While one fraction of the bacterial population adheres to the mucosal surface and forms a biofilm, the other subpopulation spreads to distant tissue sites,” is how the investigators described it. We can increase surface colonization by using a “job-sharing” process, they said, and even resist antibiotics because most of us remain in the protective biofilm.

LOTME: And they say you guys don’t have brains.

P. aeruginosa: But wait, there’s more. We don’t just divide the labor randomly. After the initial colonization we form two functionally distinct subpopulations. One has high levels of the bacterial signaling molecule c-di-GMP and stays put to work on the biofilm. The other group, with low levels of c-di-GMP, heads out to the surrounding tissue to continue the colonization. As project leader Urs Jenal put it, “By identifying the genetic switch, we have tracked down the Achilles heel of the pathogen.”

LOTME: Pretty clever stuff, for humans, anyway.

P. aeruginosa: We agree, but now that you know our secret, we can’t let you share it.

LOTME: Wait! The journal article’s already been published. Your secret is out. You can’t stop that by infecting me.

P. aeruginosa: True enough, but are you familiar with the fable of the scorpion and the frog? It’s our nature.

LOTME: Nooooo! N. gonorrhoeae wouldn’t have done this!

What a pain in the Butt

Businesses rise and businesses fall. We all know that one cursed location, that spot in town where we see businesses move in and close up in a matter of months. At the same time, though, there are also businesses that have been around as long as anyone can remember, pillars of the community.

Corydon, IN., likely has a few such long-lived shops, but it is officially down one 70-year-old family business as of late April, with the unfortunate passing of beloved local pharmacy Butt Drugs. Prescription pick-up in rear.

The business dates back to 1952, when it was founded as William H. Butt Drugs. We’re sure William Butt was never teased about his last name. Nope. No one would ever do that. After he passed the store to his children, it underwent a stint as Butt Rexall Drugs. When the shop was passed down to its third-generation and ultimately final owner, Katie Butt Beckort, she decided to simplify the name. Get right down to the bottom of things, as it were.

Butt Drugs was a popular spot, featuring an old-school soda fountain and themed souvenirs. According to Ms. Butt Beckort, people would come from miles away to buy “I love Butt Drugs” T-shirts, magnets, and so on. Yes, they knew perfectly well what they were sitting on.

So, if was such a hit, why did it close? Butt Drugs may have a hilarious name and merchandise to match, but the pharmacy portion of the pharmacy had been losing money for years. You know, the actual point of the business. As with so many things, we can blame it on the insurance companies. More than half the drugs that passed through Butt Drugs’ doors were sold at a loss, because the insurance companies refused to reimburse the store more than the wholesale price of the drug. Not even a good butt drug could clear up that financial diarrhea.

And so, we’ve lost Butt Drugs forever. Spicy food enthusiasts, coffee drinkers, and all patrons of Taco Bell, take a moment to reflect and mourn on what you’ve lost. No more Butt Drugs to relieve your suffering. A true kick in the butt indeed.

Low-calorie tastes sweeter with a little salt

Diet and sugar-free foods and drinks seem like a good idea, but it’s hard to get past that strange aftertaste, right? It’s the calling card for the noncaloric aspartame- and stevia-containing sweeteners that we consume to make us feel like we can have the best of both worlds.

That weird lingering taste can be a total turn-off for some (raises hand), but researchers have found an almost facepalm solution to the not-so-sweet problem, and it’s salt.

Now, the concept of sweet and salty is not a far-fetched partnership when it comes to snack consumption (try M&Ms in your popcorn). The researchers at Almendra, a manufacturer of stevia sweeteners, put that iconic flavor pair to the test by adding mineral salts that have some nutritional value to lessen the effect of a stevia compound, rebaudioside A, found in noncaloric sweeteners.

The researchers added in magnesium chloride, calcium chloride, and potassium chloride separately to lessen rebaudioside A’s intensity, but they needed so much salt that it killed the sweet taste completely. A blend of the three mineral salts, however, reduced the lingering taste by 79% and improved the real sugar-like taste. The researchers tried this blend in reduced-calorie orange juice and a citrus-flavored soft drink, improving the taste in both.

The salty and sweet match comes in for the win once again. This time helping against the fight of obesity instead of making it worse.

Pseudomonas’ Achilles’ heel is more of an Achilles’ genetic switch

Today, on the long-awaited return of “Bacteria vs. the World,” we meet one of the rock stars of infectious disease.

LOTME: Through the use of imaginary technology, we’re talking to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Thanks for joining us on such short notice, after Neisseria gonorrhoeae canceled at the last minute.

P. aeruginosa: No problem. I think we can all guess what that little devil is up to.

LOTME: Bacterial resistance to antibiotics is a huge problem for our species. What makes you so hard to fight?

P. aeruginosa: We’ve been trying to keep that a secret, actually, but now that researchers in Switzerland and Denmark seem to have figured it out, I guess it’s okay for me to spill the beans.

LOTME: Beans? What do beans have to do with it?

P. aeruginosa: Nothing, it’s just a colloquial expression that means I’m sharing previously private information.

LOTME: Sure, we knew that. Please, continue your spilling.

P. aeruginosa: The secret is … Well, let’s just say we were a little worried when the Clash released “Should I Stay or Should I Go” back in the 1980s.

LOTME: The Clash? Now we’re really confused.

P. aeruginosa: The answer to their question, “Should I stay or should I go? is yes. Successful invasion of a human is all about division of labor. “While one fraction of the bacterial population adheres to the mucosal surface and forms a biofilm, the other subpopulation spreads to distant tissue sites,” is how the investigators described it. We can increase surface colonization by using a “job-sharing” process, they said, and even resist antibiotics because most of us remain in the protective biofilm.

LOTME: And they say you guys don’t have brains.

P. aeruginosa: But wait, there’s more. We don’t just divide the labor randomly. After the initial colonization we form two functionally distinct subpopulations. One has high levels of the bacterial signaling molecule c-di-GMP and stays put to work on the biofilm. The other group, with low levels of c-di-GMP, heads out to the surrounding tissue to continue the colonization. As project leader Urs Jenal put it, “By identifying the genetic switch, we have tracked down the Achilles heel of the pathogen.”

LOTME: Pretty clever stuff, for humans, anyway.

P. aeruginosa: We agree, but now that you know our secret, we can’t let you share it.

LOTME: Wait! The journal article’s already been published. Your secret is out. You can’t stop that by infecting me.

P. aeruginosa: True enough, but are you familiar with the fable of the scorpion and the frog? It’s our nature.

LOTME: Nooooo! N. gonorrhoeae wouldn’t have done this!

What a pain in the Butt

Businesses rise and businesses fall. We all know that one cursed location, that spot in town where we see businesses move in and close up in a matter of months. At the same time, though, there are also businesses that have been around as long as anyone can remember, pillars of the community.

Corydon, IN., likely has a few such long-lived shops, but it is officially down one 70-year-old family business as of late April, with the unfortunate passing of beloved local pharmacy Butt Drugs. Prescription pick-up in rear.

The business dates back to 1952, when it was founded as William H. Butt Drugs. We’re sure William Butt was never teased about his last name. Nope. No one would ever do that. After he passed the store to his children, it underwent a stint as Butt Rexall Drugs. When the shop was passed down to its third-generation and ultimately final owner, Katie Butt Beckort, she decided to simplify the name. Get right down to the bottom of things, as it were.

Butt Drugs was a popular spot, featuring an old-school soda fountain and themed souvenirs. According to Ms. Butt Beckort, people would come from miles away to buy “I love Butt Drugs” T-shirts, magnets, and so on. Yes, they knew perfectly well what they were sitting on.

So, if was such a hit, why did it close? Butt Drugs may have a hilarious name and merchandise to match, but the pharmacy portion of the pharmacy had been losing money for years. You know, the actual point of the business. As with so many things, we can blame it on the insurance companies. More than half the drugs that passed through Butt Drugs’ doors were sold at a loss, because the insurance companies refused to reimburse the store more than the wholesale price of the drug. Not even a good butt drug could clear up that financial diarrhea.

And so, we’ve lost Butt Drugs forever. Spicy food enthusiasts, coffee drinkers, and all patrons of Taco Bell, take a moment to reflect and mourn on what you’ve lost. No more Butt Drugs to relieve your suffering. A true kick in the butt indeed.

Low-calorie tastes sweeter with a little salt

Diet and sugar-free foods and drinks seem like a good idea, but it’s hard to get past that strange aftertaste, right? It’s the calling card for the noncaloric aspartame- and stevia-containing sweeteners that we consume to make us feel like we can have the best of both worlds.

That weird lingering taste can be a total turn-off for some (raises hand), but researchers have found an almost facepalm solution to the not-so-sweet problem, and it’s salt.

Now, the concept of sweet and salty is not a far-fetched partnership when it comes to snack consumption (try M&Ms in your popcorn). The researchers at Almendra, a manufacturer of stevia sweeteners, put that iconic flavor pair to the test by adding mineral salts that have some nutritional value to lessen the effect of a stevia compound, rebaudioside A, found in noncaloric sweeteners.

The researchers added in magnesium chloride, calcium chloride, and potassium chloride separately to lessen rebaudioside A’s intensity, but they needed so much salt that it killed the sweet taste completely. A blend of the three mineral salts, however, reduced the lingering taste by 79% and improved the real sugar-like taste. The researchers tried this blend in reduced-calorie orange juice and a citrus-flavored soft drink, improving the taste in both.

The salty and sweet match comes in for the win once again. This time helping against the fight of obesity instead of making it worse.

Pseudomonas’ Achilles’ heel is more of an Achilles’ genetic switch

Today, on the long-awaited return of “Bacteria vs. the World,” we meet one of the rock stars of infectious disease.

LOTME: Through the use of imaginary technology, we’re talking to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Thanks for joining us on such short notice, after Neisseria gonorrhoeae canceled at the last minute.

P. aeruginosa: No problem. I think we can all guess what that little devil is up to.

LOTME: Bacterial resistance to antibiotics is a huge problem for our species. What makes you so hard to fight?

P. aeruginosa: We’ve been trying to keep that a secret, actually, but now that researchers in Switzerland and Denmark seem to have figured it out, I guess it’s okay for me to spill the beans.

LOTME: Beans? What do beans have to do with it?

P. aeruginosa: Nothing, it’s just a colloquial expression that means I’m sharing previously private information.

LOTME: Sure, we knew that. Please, continue your spilling.

P. aeruginosa: The secret is … Well, let’s just say we were a little worried when the Clash released “Should I Stay or Should I Go” back in the 1980s.

LOTME: The Clash? Now we’re really confused.

P. aeruginosa: The answer to their question, “Should I stay or should I go? is yes. Successful invasion of a human is all about division of labor. “While one fraction of the bacterial population adheres to the mucosal surface and forms a biofilm, the other subpopulation spreads to distant tissue sites,” is how the investigators described it. We can increase surface colonization by using a “job-sharing” process, they said, and even resist antibiotics because most of us remain in the protective biofilm.

LOTME: And they say you guys don’t have brains.

P. aeruginosa: But wait, there’s more. We don’t just divide the labor randomly. After the initial colonization we form two functionally distinct subpopulations. One has high levels of the bacterial signaling molecule c-di-GMP and stays put to work on the biofilm. The other group, with low levels of c-di-GMP, heads out to the surrounding tissue to continue the colonization. As project leader Urs Jenal put it, “By identifying the genetic switch, we have tracked down the Achilles heel of the pathogen.”

LOTME: Pretty clever stuff, for humans, anyway.

P. aeruginosa: We agree, but now that you know our secret, we can’t let you share it.

LOTME: Wait! The journal article’s already been published. Your secret is out. You can’t stop that by infecting me.

P. aeruginosa: True enough, but are you familiar with the fable of the scorpion and the frog? It’s our nature.

LOTME: Nooooo! N. gonorrhoeae wouldn’t have done this!

What a pain in the Butt

Businesses rise and businesses fall. We all know that one cursed location, that spot in town where we see businesses move in and close up in a matter of months. At the same time, though, there are also businesses that have been around as long as anyone can remember, pillars of the community.

Corydon, IN., likely has a few such long-lived shops, but it is officially down one 70-year-old family business as of late April, with the unfortunate passing of beloved local pharmacy Butt Drugs. Prescription pick-up in rear.

The business dates back to 1952, when it was founded as William H. Butt Drugs. We’re sure William Butt was never teased about his last name. Nope. No one would ever do that. After he passed the store to his children, it underwent a stint as Butt Rexall Drugs. When the shop was passed down to its third-generation and ultimately final owner, Katie Butt Beckort, she decided to simplify the name. Get right down to the bottom of things, as it were.

Butt Drugs was a popular spot, featuring an old-school soda fountain and themed souvenirs. According to Ms. Butt Beckort, people would come from miles away to buy “I love Butt Drugs” T-shirts, magnets, and so on. Yes, they knew perfectly well what they were sitting on.

So, if was such a hit, why did it close? Butt Drugs may have a hilarious name and merchandise to match, but the pharmacy portion of the pharmacy had been losing money for years. You know, the actual point of the business. As with so many things, we can blame it on the insurance companies. More than half the drugs that passed through Butt Drugs’ doors were sold at a loss, because the insurance companies refused to reimburse the store more than the wholesale price of the drug. Not even a good butt drug could clear up that financial diarrhea.

And so, we’ve lost Butt Drugs forever. Spicy food enthusiasts, coffee drinkers, and all patrons of Taco Bell, take a moment to reflect and mourn on what you’ve lost. No more Butt Drugs to relieve your suffering. A true kick in the butt indeed.

Proteomics reveals potential targets for drug-resistant TB

TOPLINE:

Downregulation of plasma exosome-derived apolipoproteins APOA1, APOB, and APOC1 indicates DR-TB status and lipid metabolism regulation in pathogenesis.

METHODOLOGY:

Group case-controlled study assessed 17 drug resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) and 33 non–drug resistant TB (NDR-TB) patients at The Fourth People’s Hospital of Taiyuan, China, from November 2018 to March 2019.

Plasma exosome purity and quality was determined by transmission electron microscopy, nanoparticle tracking analysis, and Western blot markers.

Proteins purified from plasma exosomes were characterized by SDS-Page with Western blotting and liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry techniques.

Functional proteomic differential analysis was achieved using the UniProt-GOA, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), and STRING databases.

TAKEAWAYS:

DR-TB patients tended to be older than NDR-TB patients.

Isolated plasma exosomes were morphologically characterized as being “close to pure.”

Differential gene expression analysis revealed 16 upregulated and 10 downregulated proteins from DR-TB compared with NDR-TB patient-derived plasma exosomes.

through their functions in lipid metabolism and protein transport.

IN PRACTICE:

Key apolipoproteins “may be involved in the pathogenesis of DR-TB via accelerating the formation of foamy macrophages and reducing the cellular uptake of anti-TB drugs.”

STUDY DETAILS:

The study led by Mingrui Wu of Shanxi (China) Medical University and colleagues was published in the July 2023 issue of Tuberculosis.

LIMITATIONS:

This study is limited by an enrollment bias of at least twice as many men to women patients for both DR-TB and NDR-TB categories, reporting of some incomplete data collection characterizing the study population, and small sample size, which did not permit stratified analysis of the five types of DR-TB.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Downregulation of plasma exosome-derived apolipoproteins APOA1, APOB, and APOC1 indicates DR-TB status and lipid metabolism regulation in pathogenesis.

METHODOLOGY:

Group case-controlled study assessed 17 drug resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) and 33 non–drug resistant TB (NDR-TB) patients at The Fourth People’s Hospital of Taiyuan, China, from November 2018 to March 2019.

Plasma exosome purity and quality was determined by transmission electron microscopy, nanoparticle tracking analysis, and Western blot markers.

Proteins purified from plasma exosomes were characterized by SDS-Page with Western blotting and liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry techniques.

Functional proteomic differential analysis was achieved using the UniProt-GOA, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), and STRING databases.

TAKEAWAYS:

DR-TB patients tended to be older than NDR-TB patients.

Isolated plasma exosomes were morphologically characterized as being “close to pure.”

Differential gene expression analysis revealed 16 upregulated and 10 downregulated proteins from DR-TB compared with NDR-TB patient-derived plasma exosomes.

through their functions in lipid metabolism and protein transport.

IN PRACTICE:

Key apolipoproteins “may be involved in the pathogenesis of DR-TB via accelerating the formation of foamy macrophages and reducing the cellular uptake of anti-TB drugs.”

STUDY DETAILS:

The study led by Mingrui Wu of Shanxi (China) Medical University and colleagues was published in the July 2023 issue of Tuberculosis.

LIMITATIONS:

This study is limited by an enrollment bias of at least twice as many men to women patients for both DR-TB and NDR-TB categories, reporting of some incomplete data collection characterizing the study population, and small sample size, which did not permit stratified analysis of the five types of DR-TB.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Downregulation of plasma exosome-derived apolipoproteins APOA1, APOB, and APOC1 indicates DR-TB status and lipid metabolism regulation in pathogenesis.

METHODOLOGY:

Group case-controlled study assessed 17 drug resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) and 33 non–drug resistant TB (NDR-TB) patients at The Fourth People’s Hospital of Taiyuan, China, from November 2018 to March 2019.

Plasma exosome purity and quality was determined by transmission electron microscopy, nanoparticle tracking analysis, and Western blot markers.

Proteins purified from plasma exosomes were characterized by SDS-Page with Western blotting and liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry techniques.

Functional proteomic differential analysis was achieved using the UniProt-GOA, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), and STRING databases.

TAKEAWAYS:

DR-TB patients tended to be older than NDR-TB patients.

Isolated plasma exosomes were morphologically characterized as being “close to pure.”

Differential gene expression analysis revealed 16 upregulated and 10 downregulated proteins from DR-TB compared with NDR-TB patient-derived plasma exosomes.

through their functions in lipid metabolism and protein transport.

IN PRACTICE:

Key apolipoproteins “may be involved in the pathogenesis of DR-TB via accelerating the formation of foamy macrophages and reducing the cellular uptake of anti-TB drugs.”

STUDY DETAILS:

The study led by Mingrui Wu of Shanxi (China) Medical University and colleagues was published in the July 2023 issue of Tuberculosis.

LIMITATIONS:

This study is limited by an enrollment bias of at least twice as many men to women patients for both DR-TB and NDR-TB categories, reporting of some incomplete data collection characterizing the study population, and small sample size, which did not permit stratified analysis of the five types of DR-TB.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

New tool uses nanotechnology to speed up diagnostic testing of infectious disease

A new tool promises to expedite detection of infectious disease, according to researchers from McGill University, Montreal.

The diagnostic platform, called The device was tested for several respiratory viruses and bacteria, including the H1N1 influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2. It achieved 95% accuracy at identifying COVID-19 and its variants in 48 human saliva samples.

“COVID was something that opened our eyes, and now we have to think more seriously about point-of-care diagnostics,” Sara Mahshid, PhD, assistant professor of biomedical engineering and Canada Research Chair in Nano-Biosensing Devices at McGill University, said in an interview. The technology could become important for a range of medical applications, especially in low-resource areas.

The development was detailed in an article in Nature Nanotechnology.

Nonclinical setting

The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated the need for fast and accurate testing that can be used outside of a clinical setting. The gold-standard diagnostic method is PCR testing, but its accuracy comes with a trade-off. PCR testing involves a lengthy protocol and requires a centralized testing facility.

With QolorEX, the investigators aimed to develop a new test that achieves the accuracy of PCR in an automated tool that can be used outside of a testing facility or hospital setting. Dr. Mahshid noted a particular need for a tool that could be used in congregate settings, such as airports, schools, or restaurants.

The device is compact enough to sit on a tabletop or bench and can be used easily in group settings, according to Dr. Mahshid. In the future, she hopes to further miniaturize the device to make it more scalable for widespread use.

Requiring only a saliva sample, the tool is easy to use. Unlike current COVID-19 rapid tests, which involve several steps, the system is automated and does not require manually mixing reagents. After collecting a sample, a user taps a button in a smartphone or computer application. The device handles the rest.

“We’re not chemists who understand how to mix these solutions,” Dr. Mahshid said. Avoiding those extra steps may reduce the false positives and false negatives caused by user error.

Fast results

QolorEX can return results in 13 minutes, like a rapid antigen test does. Like a PCR test, the device uses nucleic acid amplification. But PCR tests typically take much longer. The sample analysis alone takes 1.5-2 hours.

The new test accelerates the reaction by injecting light-excited “hot” electrons from the surface of a nanoplasmonic sensor. The device then uses imaging and a machine learning algorithm to quantify a color transformation that occurs when a pathogen is present.

The fast, reliable results make the system potentially appropriate for use in places such as airports. Previously, passengers had to wait 24 hours for a negative COVID test before boarding a plane. A device such as QolorEX would allow screening on site.

The ability of the tool to distinguish between bacterial and viral infections so quickly is “an application that is both important and extremely difficult to achieve,” according to Nikhil Bhalla, PhD, in a research briefing. Dr. Bhalla is a lecturer in electronic engineering at Ulster University, Belfast, Ireland.

The researchers hope that by delivering results quickly, the device will help reduce the spread of respiratory diseases and possibly save lives.

‘Sensitive and specific’

The primary benefit of the tool is its ability to return results quickly while having low false positive and false negative rates, according to Leyla Soleymani, PhD, of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont. “It is hard to come by rapid tests that are both sensitive and specific, compared to PCR,” Dr. Soleymani told this news organization.

Although QolorEX was developed to detect COVID-19 and other infectious diseases, the uses of the device are not limited to the pathogens tested. The tool can be applied to a range of tests that currently use PCR technology. Dr. Mahshid and her team are considering several other applications of the technology, such as analyzing therapeutics for antimicrobial-resistant pathogens prioritized by the World Health Organization. The technology may also have potential for detecting cancer and bacterial infections, Dr. Mahshid said in an interview.

But to Dr. Soleymani, the most exciting application remains its use in diagnosing infectious diseases. She noted, however, that it’s unclear whether the price of the device will be too high for widespread home use. It may be more practical for family physician clinics and other facilities.

Before the device becomes commercially available, more testing is needed to validate the results, which are based on a limited number of samples that were available in a research setting.

The study was supported by the MI4 Emergency COVID-19 Research Funding, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canada Foundation for Innovation, and McGill University. Dr. Mahshid and Dr. Soleymani reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A new tool promises to expedite detection of infectious disease, according to researchers from McGill University, Montreal.

The diagnostic platform, called The device was tested for several respiratory viruses and bacteria, including the H1N1 influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2. It achieved 95% accuracy at identifying COVID-19 and its variants in 48 human saliva samples.

“COVID was something that opened our eyes, and now we have to think more seriously about point-of-care diagnostics,” Sara Mahshid, PhD, assistant professor of biomedical engineering and Canada Research Chair in Nano-Biosensing Devices at McGill University, said in an interview. The technology could become important for a range of medical applications, especially in low-resource areas.

The development was detailed in an article in Nature Nanotechnology.

Nonclinical setting

The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated the need for fast and accurate testing that can be used outside of a clinical setting. The gold-standard diagnostic method is PCR testing, but its accuracy comes with a trade-off. PCR testing involves a lengthy protocol and requires a centralized testing facility.

With QolorEX, the investigators aimed to develop a new test that achieves the accuracy of PCR in an automated tool that can be used outside of a testing facility or hospital setting. Dr. Mahshid noted a particular need for a tool that could be used in congregate settings, such as airports, schools, or restaurants.

The device is compact enough to sit on a tabletop or bench and can be used easily in group settings, according to Dr. Mahshid. In the future, she hopes to further miniaturize the device to make it more scalable for widespread use.

Requiring only a saliva sample, the tool is easy to use. Unlike current COVID-19 rapid tests, which involve several steps, the system is automated and does not require manually mixing reagents. After collecting a sample, a user taps a button in a smartphone or computer application. The device handles the rest.

“We’re not chemists who understand how to mix these solutions,” Dr. Mahshid said. Avoiding those extra steps may reduce the false positives and false negatives caused by user error.

Fast results

QolorEX can return results in 13 minutes, like a rapid antigen test does. Like a PCR test, the device uses nucleic acid amplification. But PCR tests typically take much longer. The sample analysis alone takes 1.5-2 hours.

The new test accelerates the reaction by injecting light-excited “hot” electrons from the surface of a nanoplasmonic sensor. The device then uses imaging and a machine learning algorithm to quantify a color transformation that occurs when a pathogen is present.

The fast, reliable results make the system potentially appropriate for use in places such as airports. Previously, passengers had to wait 24 hours for a negative COVID test before boarding a plane. A device such as QolorEX would allow screening on site.

The ability of the tool to distinguish between bacterial and viral infections so quickly is “an application that is both important and extremely difficult to achieve,” according to Nikhil Bhalla, PhD, in a research briefing. Dr. Bhalla is a lecturer in electronic engineering at Ulster University, Belfast, Ireland.

The researchers hope that by delivering results quickly, the device will help reduce the spread of respiratory diseases and possibly save lives.

‘Sensitive and specific’

The primary benefit of the tool is its ability to return results quickly while having low false positive and false negative rates, according to Leyla Soleymani, PhD, of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont. “It is hard to come by rapid tests that are both sensitive and specific, compared to PCR,” Dr. Soleymani told this news organization.

Although QolorEX was developed to detect COVID-19 and other infectious diseases, the uses of the device are not limited to the pathogens tested. The tool can be applied to a range of tests that currently use PCR technology. Dr. Mahshid and her team are considering several other applications of the technology, such as analyzing therapeutics for antimicrobial-resistant pathogens prioritized by the World Health Organization. The technology may also have potential for detecting cancer and bacterial infections, Dr. Mahshid said in an interview.

But to Dr. Soleymani, the most exciting application remains its use in diagnosing infectious diseases. She noted, however, that it’s unclear whether the price of the device will be too high for widespread home use. It may be more practical for family physician clinics and other facilities.

Before the device becomes commercially available, more testing is needed to validate the results, which are based on a limited number of samples that were available in a research setting.

The study was supported by the MI4 Emergency COVID-19 Research Funding, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canada Foundation for Innovation, and McGill University. Dr. Mahshid and Dr. Soleymani reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A new tool promises to expedite detection of infectious disease, according to researchers from McGill University, Montreal.

The diagnostic platform, called The device was tested for several respiratory viruses and bacteria, including the H1N1 influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2. It achieved 95% accuracy at identifying COVID-19 and its variants in 48 human saliva samples.

“COVID was something that opened our eyes, and now we have to think more seriously about point-of-care diagnostics,” Sara Mahshid, PhD, assistant professor of biomedical engineering and Canada Research Chair in Nano-Biosensing Devices at McGill University, said in an interview. The technology could become important for a range of medical applications, especially in low-resource areas.

The development was detailed in an article in Nature Nanotechnology.

Nonclinical setting

The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated the need for fast and accurate testing that can be used outside of a clinical setting. The gold-standard diagnostic method is PCR testing, but its accuracy comes with a trade-off. PCR testing involves a lengthy protocol and requires a centralized testing facility.

With QolorEX, the investigators aimed to develop a new test that achieves the accuracy of PCR in an automated tool that can be used outside of a testing facility or hospital setting. Dr. Mahshid noted a particular need for a tool that could be used in congregate settings, such as airports, schools, or restaurants.

The device is compact enough to sit on a tabletop or bench and can be used easily in group settings, according to Dr. Mahshid. In the future, she hopes to further miniaturize the device to make it more scalable for widespread use.

Requiring only a saliva sample, the tool is easy to use. Unlike current COVID-19 rapid tests, which involve several steps, the system is automated and does not require manually mixing reagents. After collecting a sample, a user taps a button in a smartphone or computer application. The device handles the rest.

“We’re not chemists who understand how to mix these solutions,” Dr. Mahshid said. Avoiding those extra steps may reduce the false positives and false negatives caused by user error.

Fast results

QolorEX can return results in 13 minutes, like a rapid antigen test does. Like a PCR test, the device uses nucleic acid amplification. But PCR tests typically take much longer. The sample analysis alone takes 1.5-2 hours.

The new test accelerates the reaction by injecting light-excited “hot” electrons from the surface of a nanoplasmonic sensor. The device then uses imaging and a machine learning algorithm to quantify a color transformation that occurs when a pathogen is present.

The fast, reliable results make the system potentially appropriate for use in places such as airports. Previously, passengers had to wait 24 hours for a negative COVID test before boarding a plane. A device such as QolorEX would allow screening on site.

The ability of the tool to distinguish between bacterial and viral infections so quickly is “an application that is both important and extremely difficult to achieve,” according to Nikhil Bhalla, PhD, in a research briefing. Dr. Bhalla is a lecturer in electronic engineering at Ulster University, Belfast, Ireland.

The researchers hope that by delivering results quickly, the device will help reduce the spread of respiratory diseases and possibly save lives.

‘Sensitive and specific’

The primary benefit of the tool is its ability to return results quickly while having low false positive and false negative rates, according to Leyla Soleymani, PhD, of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont. “It is hard to come by rapid tests that are both sensitive and specific, compared to PCR,” Dr. Soleymani told this news organization.

Although QolorEX was developed to detect COVID-19 and other infectious diseases, the uses of the device are not limited to the pathogens tested. The tool can be applied to a range of tests that currently use PCR technology. Dr. Mahshid and her team are considering several other applications of the technology, such as analyzing therapeutics for antimicrobial-resistant pathogens prioritized by the World Health Organization. The technology may also have potential for detecting cancer and bacterial infections, Dr. Mahshid said in an interview.

But to Dr. Soleymani, the most exciting application remains its use in diagnosing infectious diseases. She noted, however, that it’s unclear whether the price of the device will be too high for widespread home use. It may be more practical for family physician clinics and other facilities.

Before the device becomes commercially available, more testing is needed to validate the results, which are based on a limited number of samples that were available in a research setting.

The study was supported by the MI4 Emergency COVID-19 Research Funding, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canada Foundation for Innovation, and McGill University. Dr. Mahshid and Dr. Soleymani reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NATURE NANOTECHNOLOGY

Cutting-edge nasal tech could usher in a new era of medicine

Noses are like caverns – twisting, turning, no two exactly the same. But if you nose past anyone’s nostrils, you’ll discover a surprisingly sprawling space.

“The size of the nasal cavity is about the same as a large handkerchief,” said Hugh Smyth, PhD, a professor of molecular pharmaceutics and drug delivery at the University of Texas at Austin.

“It’s very accessible tissue, and it has a lot of blood flow,” said Dr. Smyth. “The speed of onset can often be as fast as injections, sometimes even faster.”

It’s nothing new to get medicines via your nose. For decades, we’ve squirted various sprays into our nostrils to treat local maladies like allergies or infections. Even the ancients saw wisdom in the nasal route.

But recently, the nose has gained scientific attention as a gateway to the rest of the body – even the brain, a notoriously difficult target.

The upshot: Someday, inhaling therapies could be as routine as swallowing pills.

The nasal route is quick, needle free, and user friendly, and it often requires a smaller dose than other methods, since the drug doesn’t have to pass through the digestive tract, losing potency during digestion.

But there are challenges.

How hard can it be?

Old-school nasal sprayers, mostly unchanged since the 1800s, aren’t cut out for deep-nose delivery. “The technology is relatively limited because you’ve just got a single spray nozzle,” said Michael Hindle, PhD, a professor of pharmaceutics at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond.

These traditional devices (similar to perfume sprayers) don’t consistently push meds past the lower to middle sections inside the nose, called the nasal valve – if they do so at all: In a 2020 Rhinology study (doi: 10.4193/Rhin18.304) conventional nasal sprays only reached this first segment of the nose, a less-than-ideal spot to land.

Inside the nasal valve, the surface is skin-like and doesn’t absorb very well. Its narrow design slows airflow, preventing particles from moving to deeper regions, where tissue is vascular and porous like the lungs. And even if this structural roadblock is surpassed, other hurdles remain.

The nose is designed to keep stuff out. Nose hair, cilia, mucus, sneezing, coughing – all make “distributing drugs evenly across the nasal cavity difficult,” said Dr. Smyth. “The spray gets filtered out before it reaches those deeper zones,” potentially dripping out of the nostrils instead of being absorbed.

Complicating matters is how every person’s nose is different. In a 2018 study, Dr. Smyth and a research team created three dimensional–printed models of people’s nasal cavities. They varied widely. “Nasal cavities are very different in size, length, and internal geometry,” he said. “This makes it challenging to target specific areas.”

Although carefully positioning the spray nozzle can help, even something as minor as sniffing too hard (constricting the nostrils) can keep sprays from reaching the absorptive deeper regions.

Still, the benefits are enough to compel researchers to find a way in.

“This really is a drug delivery challenge we’ve been wrestling with,” said Dr. Hindle. “It’s not new formulations we hear about. It’s new devices and delivery methods trying to target the different nasal regions.”

Delivering the goods

In the late aughts, John Hoekman was a graduate student in the University of Washington’s pharmaceutics program, studying nasal drug delivery. In his experiments, he noticed that drugs distributed differently, depending on the region targeted – aiming for the upper nasal cavity led to a spike in absorption.

The results convinced Mr. Hoekman to stake his future on nasal drug delivery.

In 2008, while still in graduate school, he started his own company, now known as Impel Pharmaceuticals. In 2021, Impel released its first product: Trudhesa, a nasal spray for migraines. Although the drug itself – dihydroergotamine mesylate – was hardly novel, used for migraine relief since 1946 (Headache. 2020 Jan;60[1]:40-57), it was usually delivered through an intravenous line, often in the ED.

But with Mr. Hoekman’s POD device – short for precision olfactory delivery – the drug can be given by the patient, via the nose. This generally means faster, more reliable relief, with fewer side effects. “We were able to lower the dose and improve the overall absorption,” said Mr. Hoekman.

The POD’s nozzle is engineered to spray a soft, narrow plume. It’s gas propelled, so patients don’t have to breathe in any special way to ensure delivery. The drug can zip right through the nasal valve into the upper nasal cavity.

Another company – OptiNose – has a “bidirectional” delivery method that propels drugs, either liquid or dry powder, deep into the nose.

“You insert the nozzle into your nose, and as you blow through the mouthpiece, your soft palate closes,” said Dr. Hindle. With the throat sealed off, “the only place for the drug to go is into one nostril and out the other, coating both sides of the nasal passageways.”

The device is only available for Onzetra Xsail, a powder for migraines. But another application is on its way.

In May, OptiNose announced that the FDA is reviewing Xhance, which uses the system to direct a steroid to the sinuses. In a clinical trial, patients with chronic sinusitis who tried the drug-device combo saw a decline in congestion, facial pain, and inflammation.

Targeting the brain

Both of those migraine drugs – Trudhesa and Onzetra Xsail – are thought to penetrate the upper nasal cavity. That’s where you’ll find the olfactory zone, a sheet of neurons that connects to the olfactory bulb. Located behind the eyes, these two nerve bundles detect odors.

“The olfactory region is almost like a back door to the brain,” said Mr. Hoekman.

By bypassing the blood-brain barrier, it offers a direct pathway – the only direct pathway, actually – between an exposed area of the body and the brain. Meaning it can ferry drugs straight from the nasal cavity to the central nervous system.

Nose-to-brain treatments could be game-changing for central nervous system disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s, or anxiety.

But reaching the olfactory zone is notoriously hard. “The vasculature in your nose is like a big freeway, and the olfactory tract is like a side alley,” explained Mr. Hoekman. “It’s very limiting in what it will allow through.” The region is also small, occupying only 3%-10% of the nasal cavity’s surface area.

Again, POD means “precision olfactory delivery.” But the device isn’t quite as laser focused on the region as its name implies. “We’re not at the stage where we’re able to exclusively deliver to one target site in the nose,” said Dr. Hindle.

While wending its way toward the olfactory zone, some of the drug will be absorbed by other regions, then circulate throughout the body.

“About 59% of the drug that we put into the upper nasal space gets absorbed into the bloodstream,” said Mr. Hoekman.

Janssen Pharmaceuticals’ Spravato – a nasal spray for drug-resistant depression – is thought to work similarly: Some goes straight to the brain via the olfactory nerves, while the rest takes a more roundabout route, passing through the blood vessels to circulate in your system.

A needle-free option

Sometimes, the bloodstream is the main target. Because the nose’s middle and upper stretches are so vascular, drugs can be rapidly absorbed.

This is especially valuable for time-sensitive conditions. “If you give something nasally, you can have peak uptake in 15-30 minutes,” said Mr. Hoekman.

Take Narcan nasal spray, which delivers a burst of naloxone to quickly reverse the effects of opioid an overdose. Or Noctiva nasal spray. Taken just half an hour before bed, it can prevent frequent nighttime urination.

There’s also a group of seizure-stopping sprays, known as “rescue treatments.” One works by temporarily loosening the space between nasal cells, allowing the seizure drug to be quickly absorbed through the vessels.

This systemic access also has potential for drugs that would otherwise have to be injected, such as biologics.

The same goes for vaccines. Mucosal tissue inside the nasal cavity offers direct access to the infection-fighting lymphatic system, making the nose a prime target for inoculation against certain viruses.

Inhaling protection against viruses

Despite the recent surge of interest, nasal vaccines faced a rocky start. After the first nasal flu vaccine hit the market in 2001, it was pulled due to potential toxicity and reports of Bell’s palsy, a type of facial paralysis.

FluMist came in 2003 and has been plagued by problems ever since. Because it contains a weakened live virus, flu-like side effects can occur. And it doesn’t always work. During the 2016-2017 flu season, FluMist protected only 3% of kids, prompting the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to advise against the nasal route that year.

Why FluMist can be so hit-or-miss is poorly understood. But generally, the nose can pose an effectiveness challenge. “The nose is highly cycling,” said Dr. Hindle. “Anything we deposit usually gets transported out within 15-20 minutes.”

For kids – big fans of not using needles – chronically runny noses can be an issue. “You squirt it in the nose, and it will probably just come back out in their snot,” said Jay Kolls, MD, a professor of medicine and pediatrics at Tulane University, New Orleans, who is developing an intranasal pneumonia vaccine.

Even so, nasal vaccines became a hot topic among researchers after the world was shut down by a virus that invades through the nose.

“We realized that intramuscular vaccines were effective at preventing severe disease, but they weren’t that effective at preventing transmission,” said Michael Diamond, MD, PhD, an immunologist at Washington University in St. Louis.

Nasal vaccines could solve that problem by putting an immune barrier at the point of entry, denying access to the rest of the body. “You squash the infection early enough that it not only prevents disease,” said Dr. Kolls, “but potentially prevents transmission.”

And yes, a nasal COVID vaccine is on the way

In March 2020, Dr. Diamond’s team began exploring a nasal COVID vaccine. Promising results in animals prompted a vaccine development company to license the technology. The resulting nasal vaccine – the first for COVID – has been approved in India, both as a primary vaccine and a booster.

It works by stimulating an influx of IgA, a type of antibody found in the nasal passages, and production of resident memory T cells, immune cells on standby just beneath the surface tissue in the nose.

By contrast, injected vaccines generate mostly IgG antibodies, which struggle to enter the respiratory tract. Only a tiny fraction – an estimated 1% – typically reach the nose.

Nasal vaccines could also be used along with shots. The latter could prime the whole body to fight back, while a nasal spritz could pull that immune protection to the mucosal surfaces.

Nasal technology could yield more effective vaccines for infections like tuberculosis or malaria, or even safeguard against new – sometimes surprising – conditions.

In a 2021 Nature study, an intranasal vaccine derived from fentanyl was better at preventing overdose than an injected vaccine. “Through some clever chemistry, the drug [in the vaccine] isn’t fentanyl anymore,” said study author Elizabeth Norton, PhD, an assistant professor of microbiology and immunology at Tulane University. “But the immune system still has an antibody response to it.”

Novel applications like this represent the future of nasal drug delivery.

“We’re not going to innovate in asthma or COPD. We’re not going to innovate in local delivery to the nose,” said Dr. Hindle. “Innovation will only come if we look to treat new conditions.”

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

Noses are like caverns – twisting, turning, no two exactly the same. But if you nose past anyone’s nostrils, you’ll discover a surprisingly sprawling space.

“The size of the nasal cavity is about the same as a large handkerchief,” said Hugh Smyth, PhD, a professor of molecular pharmaceutics and drug delivery at the University of Texas at Austin.

“It’s very accessible tissue, and it has a lot of blood flow,” said Dr. Smyth. “The speed of onset can often be as fast as injections, sometimes even faster.”

It’s nothing new to get medicines via your nose. For decades, we’ve squirted various sprays into our nostrils to treat local maladies like allergies or infections. Even the ancients saw wisdom in the nasal route.

But recently, the nose has gained scientific attention as a gateway to the rest of the body – even the brain, a notoriously difficult target.

The upshot: Someday, inhaling therapies could be as routine as swallowing pills.

The nasal route is quick, needle free, and user friendly, and it often requires a smaller dose than other methods, since the drug doesn’t have to pass through the digestive tract, losing potency during digestion.

But there are challenges.

How hard can it be?

Old-school nasal sprayers, mostly unchanged since the 1800s, aren’t cut out for deep-nose delivery. “The technology is relatively limited because you’ve just got a single spray nozzle,” said Michael Hindle, PhD, a professor of pharmaceutics at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond.

These traditional devices (similar to perfume sprayers) don’t consistently push meds past the lower to middle sections inside the nose, called the nasal valve – if they do so at all: In a 2020 Rhinology study (doi: 10.4193/Rhin18.304) conventional nasal sprays only reached this first segment of the nose, a less-than-ideal spot to land.

Inside the nasal valve, the surface is skin-like and doesn’t absorb very well. Its narrow design slows airflow, preventing particles from moving to deeper regions, where tissue is vascular and porous like the lungs. And even if this structural roadblock is surpassed, other hurdles remain.

The nose is designed to keep stuff out. Nose hair, cilia, mucus, sneezing, coughing – all make “distributing drugs evenly across the nasal cavity difficult,” said Dr. Smyth. “The spray gets filtered out before it reaches those deeper zones,” potentially dripping out of the nostrils instead of being absorbed.

Complicating matters is how every person’s nose is different. In a 2018 study, Dr. Smyth and a research team created three dimensional–printed models of people’s nasal cavities. They varied widely. “Nasal cavities are very different in size, length, and internal geometry,” he said. “This makes it challenging to target specific areas.”

Although carefully positioning the spray nozzle can help, even something as minor as sniffing too hard (constricting the nostrils) can keep sprays from reaching the absorptive deeper regions.

Still, the benefits are enough to compel researchers to find a way in.

“This really is a drug delivery challenge we’ve been wrestling with,” said Dr. Hindle. “It’s not new formulations we hear about. It’s new devices and delivery methods trying to target the different nasal regions.”

Delivering the goods

In the late aughts, John Hoekman was a graduate student in the University of Washington’s pharmaceutics program, studying nasal drug delivery. In his experiments, he noticed that drugs distributed differently, depending on the region targeted – aiming for the upper nasal cavity led to a spike in absorption.

The results convinced Mr. Hoekman to stake his future on nasal drug delivery.

In 2008, while still in graduate school, he started his own company, now known as Impel Pharmaceuticals. In 2021, Impel released its first product: Trudhesa, a nasal spray for migraines. Although the drug itself – dihydroergotamine mesylate – was hardly novel, used for migraine relief since 1946 (Headache. 2020 Jan;60[1]:40-57), it was usually delivered through an intravenous line, often in the ED.

But with Mr. Hoekman’s POD device – short for precision olfactory delivery – the drug can be given by the patient, via the nose. This generally means faster, more reliable relief, with fewer side effects. “We were able to lower the dose and improve the overall absorption,” said Mr. Hoekman.

The POD’s nozzle is engineered to spray a soft, narrow plume. It’s gas propelled, so patients don’t have to breathe in any special way to ensure delivery. The drug can zip right through the nasal valve into the upper nasal cavity.

Another company – OptiNose – has a “bidirectional” delivery method that propels drugs, either liquid or dry powder, deep into the nose.

“You insert the nozzle into your nose, and as you blow through the mouthpiece, your soft palate closes,” said Dr. Hindle. With the throat sealed off, “the only place for the drug to go is into one nostril and out the other, coating both sides of the nasal passageways.”

The device is only available for Onzetra Xsail, a powder for migraines. But another application is on its way.

In May, OptiNose announced that the FDA is reviewing Xhance, which uses the system to direct a steroid to the sinuses. In a clinical trial, patients with chronic sinusitis who tried the drug-device combo saw a decline in congestion, facial pain, and inflammation.

Targeting the brain

Both of those migraine drugs – Trudhesa and Onzetra Xsail – are thought to penetrate the upper nasal cavity. That’s where you’ll find the olfactory zone, a sheet of neurons that connects to the olfactory bulb. Located behind the eyes, these two nerve bundles detect odors.

“The olfactory region is almost like a back door to the brain,” said Mr. Hoekman.

By bypassing the blood-brain barrier, it offers a direct pathway – the only direct pathway, actually – between an exposed area of the body and the brain. Meaning it can ferry drugs straight from the nasal cavity to the central nervous system.

Nose-to-brain treatments could be game-changing for central nervous system disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s, or anxiety.

But reaching the olfactory zone is notoriously hard. “The vasculature in your nose is like a big freeway, and the olfactory tract is like a side alley,” explained Mr. Hoekman. “It’s very limiting in what it will allow through.” The region is also small, occupying only 3%-10% of the nasal cavity’s surface area.

Again, POD means “precision olfactory delivery.” But the device isn’t quite as laser focused on the region as its name implies. “We’re not at the stage where we’re able to exclusively deliver to one target site in the nose,” said Dr. Hindle.

While wending its way toward the olfactory zone, some of the drug will be absorbed by other regions, then circulate throughout the body.

“About 59% of the drug that we put into the upper nasal space gets absorbed into the bloodstream,” said Mr. Hoekman.

Janssen Pharmaceuticals’ Spravato – a nasal spray for drug-resistant depression – is thought to work similarly: Some goes straight to the brain via the olfactory nerves, while the rest takes a more roundabout route, passing through the blood vessels to circulate in your system.

A needle-free option

Sometimes, the bloodstream is the main target. Because the nose’s middle and upper stretches are so vascular, drugs can be rapidly absorbed.

This is especially valuable for time-sensitive conditions. “If you give something nasally, you can have peak uptake in 15-30 minutes,” said Mr. Hoekman.

Take Narcan nasal spray, which delivers a burst of naloxone to quickly reverse the effects of opioid an overdose. Or Noctiva nasal spray. Taken just half an hour before bed, it can prevent frequent nighttime urination.

There’s also a group of seizure-stopping sprays, known as “rescue treatments.” One works by temporarily loosening the space between nasal cells, allowing the seizure drug to be quickly absorbed through the vessels.

This systemic access also has potential for drugs that would otherwise have to be injected, such as biologics.

The same goes for vaccines. Mucosal tissue inside the nasal cavity offers direct access to the infection-fighting lymphatic system, making the nose a prime target for inoculation against certain viruses.

Inhaling protection against viruses

Despite the recent surge of interest, nasal vaccines faced a rocky start. After the first nasal flu vaccine hit the market in 2001, it was pulled due to potential toxicity and reports of Bell’s palsy, a type of facial paralysis.

FluMist came in 2003 and has been plagued by problems ever since. Because it contains a weakened live virus, flu-like side effects can occur. And it doesn’t always work. During the 2016-2017 flu season, FluMist protected only 3% of kids, prompting the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to advise against the nasal route that year.

Why FluMist can be so hit-or-miss is poorly understood. But generally, the nose can pose an effectiveness challenge. “The nose is highly cycling,” said Dr. Hindle. “Anything we deposit usually gets transported out within 15-20 minutes.”

For kids – big fans of not using needles – chronically runny noses can be an issue. “You squirt it in the nose, and it will probably just come back out in their snot,” said Jay Kolls, MD, a professor of medicine and pediatrics at Tulane University, New Orleans, who is developing an intranasal pneumonia vaccine.

Even so, nasal vaccines became a hot topic among researchers after the world was shut down by a virus that invades through the nose.

“We realized that intramuscular vaccines were effective at preventing severe disease, but they weren’t that effective at preventing transmission,” said Michael Diamond, MD, PhD, an immunologist at Washington University in St. Louis.

Nasal vaccines could solve that problem by putting an immune barrier at the point of entry, denying access to the rest of the body. “You squash the infection early enough that it not only prevents disease,” said Dr. Kolls, “but potentially prevents transmission.”

And yes, a nasal COVID vaccine is on the way

In March 2020, Dr. Diamond’s team began exploring a nasal COVID vaccine. Promising results in animals prompted a vaccine development company to license the technology. The resulting nasal vaccine – the first for COVID – has been approved in India, both as a primary vaccine and a booster.

It works by stimulating an influx of IgA, a type of antibody found in the nasal passages, and production of resident memory T cells, immune cells on standby just beneath the surface tissue in the nose.

By contrast, injected vaccines generate mostly IgG antibodies, which struggle to enter the respiratory tract. Only a tiny fraction – an estimated 1% – typically reach the nose.

Nasal vaccines could also be used along with shots. The latter could prime the whole body to fight back, while a nasal spritz could pull that immune protection to the mucosal surfaces.

Nasal technology could yield more effective vaccines for infections like tuberculosis or malaria, or even safeguard against new – sometimes surprising – conditions.

In a 2021 Nature study, an intranasal vaccine derived from fentanyl was better at preventing overdose than an injected vaccine. “Through some clever chemistry, the drug [in the vaccine] isn’t fentanyl anymore,” said study author Elizabeth Norton, PhD, an assistant professor of microbiology and immunology at Tulane University. “But the immune system still has an antibody response to it.”

Novel applications like this represent the future of nasal drug delivery.

“We’re not going to innovate in asthma or COPD. We’re not going to innovate in local delivery to the nose,” said Dr. Hindle. “Innovation will only come if we look to treat new conditions.”

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

Noses are like caverns – twisting, turning, no two exactly the same. But if you nose past anyone’s nostrils, you’ll discover a surprisingly sprawling space.

“The size of the nasal cavity is about the same as a large handkerchief,” said Hugh Smyth, PhD, a professor of molecular pharmaceutics and drug delivery at the University of Texas at Austin.

“It’s very accessible tissue, and it has a lot of blood flow,” said Dr. Smyth. “The speed of onset can often be as fast as injections, sometimes even faster.”

It’s nothing new to get medicines via your nose. For decades, we’ve squirted various sprays into our nostrils to treat local maladies like allergies or infections. Even the ancients saw wisdom in the nasal route.

But recently, the nose has gained scientific attention as a gateway to the rest of the body – even the brain, a notoriously difficult target.

The upshot: Someday, inhaling therapies could be as routine as swallowing pills.

The nasal route is quick, needle free, and user friendly, and it often requires a smaller dose than other methods, since the drug doesn’t have to pass through the digestive tract, losing potency during digestion.

But there are challenges.

How hard can it be?

Old-school nasal sprayers, mostly unchanged since the 1800s, aren’t cut out for deep-nose delivery. “The technology is relatively limited because you’ve just got a single spray nozzle,” said Michael Hindle, PhD, a professor of pharmaceutics at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond.

These traditional devices (similar to perfume sprayers) don’t consistently push meds past the lower to middle sections inside the nose, called the nasal valve – if they do so at all: In a 2020 Rhinology study (doi: 10.4193/Rhin18.304) conventional nasal sprays only reached this first segment of the nose, a less-than-ideal spot to land.

Inside the nasal valve, the surface is skin-like and doesn’t absorb very well. Its narrow design slows airflow, preventing particles from moving to deeper regions, where tissue is vascular and porous like the lungs. And even if this structural roadblock is surpassed, other hurdles remain.

The nose is designed to keep stuff out. Nose hair, cilia, mucus, sneezing, coughing – all make “distributing drugs evenly across the nasal cavity difficult,” said Dr. Smyth. “The spray gets filtered out before it reaches those deeper zones,” potentially dripping out of the nostrils instead of being absorbed.

Complicating matters is how every person’s nose is different. In a 2018 study, Dr. Smyth and a research team created three dimensional–printed models of people’s nasal cavities. They varied widely. “Nasal cavities are very different in size, length, and internal geometry,” he said. “This makes it challenging to target specific areas.”

Although carefully positioning the spray nozzle can help, even something as minor as sniffing too hard (constricting the nostrils) can keep sprays from reaching the absorptive deeper regions.

Still, the benefits are enough to compel researchers to find a way in.

“This really is a drug delivery challenge we’ve been wrestling with,” said Dr. Hindle. “It’s not new formulations we hear about. It’s new devices and delivery methods trying to target the different nasal regions.”

Delivering the goods

In the late aughts, John Hoekman was a graduate student in the University of Washington’s pharmaceutics program, studying nasal drug delivery. In his experiments, he noticed that drugs distributed differently, depending on the region targeted – aiming for the upper nasal cavity led to a spike in absorption.

The results convinced Mr. Hoekman to stake his future on nasal drug delivery.

In 2008, while still in graduate school, he started his own company, now known as Impel Pharmaceuticals. In 2021, Impel released its first product: Trudhesa, a nasal spray for migraines. Although the drug itself – dihydroergotamine mesylate – was hardly novel, used for migraine relief since 1946 (Headache. 2020 Jan;60[1]:40-57), it was usually delivered through an intravenous line, often in the ED.

But with Mr. Hoekman’s POD device – short for precision olfactory delivery – the drug can be given by the patient, via the nose. This generally means faster, more reliable relief, with fewer side effects. “We were able to lower the dose and improve the overall absorption,” said Mr. Hoekman.

The POD’s nozzle is engineered to spray a soft, narrow plume. It’s gas propelled, so patients don’t have to breathe in any special way to ensure delivery. The drug can zip right through the nasal valve into the upper nasal cavity.

Another company – OptiNose – has a “bidirectional” delivery method that propels drugs, either liquid or dry powder, deep into the nose.

“You insert the nozzle into your nose, and as you blow through the mouthpiece, your soft palate closes,” said Dr. Hindle. With the throat sealed off, “the only place for the drug to go is into one nostril and out the other, coating both sides of the nasal passageways.”

The device is only available for Onzetra Xsail, a powder for migraines. But another application is on its way.

In May, OptiNose announced that the FDA is reviewing Xhance, which uses the system to direct a steroid to the sinuses. In a clinical trial, patients with chronic sinusitis who tried the drug-device combo saw a decline in congestion, facial pain, and inflammation.

Targeting the brain

Both of those migraine drugs – Trudhesa and Onzetra Xsail – are thought to penetrate the upper nasal cavity. That’s where you’ll find the olfactory zone, a sheet of neurons that connects to the olfactory bulb. Located behind the eyes, these two nerve bundles detect odors.

“The olfactory region is almost like a back door to the brain,” said Mr. Hoekman.

By bypassing the blood-brain barrier, it offers a direct pathway – the only direct pathway, actually – between an exposed area of the body and the brain. Meaning it can ferry drugs straight from the nasal cavity to the central nervous system.

Nose-to-brain treatments could be game-changing for central nervous system disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s, or anxiety.

But reaching the olfactory zone is notoriously hard. “The vasculature in your nose is like a big freeway, and the olfactory tract is like a side alley,” explained Mr. Hoekman. “It’s very limiting in what it will allow through.” The region is also small, occupying only 3%-10% of the nasal cavity’s surface area.

Again, POD means “precision olfactory delivery.” But the device isn’t quite as laser focused on the region as its name implies. “We’re not at the stage where we’re able to exclusively deliver to one target site in the nose,” said Dr. Hindle.

While wending its way toward the olfactory zone, some of the drug will be absorbed by other regions, then circulate throughout the body.

“About 59% of the drug that we put into the upper nasal space gets absorbed into the bloodstream,” said Mr. Hoekman.

Janssen Pharmaceuticals’ Spravato – a nasal spray for drug-resistant depression – is thought to work similarly: Some goes straight to the brain via the olfactory nerves, while the rest takes a more roundabout route, passing through the blood vessels to circulate in your system.

A needle-free option

Sometimes, the bloodstream is the main target. Because the nose’s middle and upper stretches are so vascular, drugs can be rapidly absorbed.

This is especially valuable for time-sensitive conditions. “If you give something nasally, you can have peak uptake in 15-30 minutes,” said Mr. Hoekman.

Take Narcan nasal spray, which delivers a burst of naloxone to quickly reverse the effects of opioid an overdose. Or Noctiva nasal spray. Taken just half an hour before bed, it can prevent frequent nighttime urination.

There’s also a group of seizure-stopping sprays, known as “rescue treatments.” One works by temporarily loosening the space between nasal cells, allowing the seizure drug to be quickly absorbed through the vessels.

This systemic access also has potential for drugs that would otherwise have to be injected, such as biologics.

The same goes for vaccines. Mucosal tissue inside the nasal cavity offers direct access to the infection-fighting lymphatic system, making the nose a prime target for inoculation against certain viruses.

Inhaling protection against viruses

Despite the recent surge of interest, nasal vaccines faced a rocky start. After the first nasal flu vaccine hit the market in 2001, it was pulled due to potential toxicity and reports of Bell’s palsy, a type of facial paralysis.

FluMist came in 2003 and has been plagued by problems ever since. Because it contains a weakened live virus, flu-like side effects can occur. And it doesn’t always work. During the 2016-2017 flu season, FluMist protected only 3% of kids, prompting the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to advise against the nasal route that year.

Why FluMist can be so hit-or-miss is poorly understood. But generally, the nose can pose an effectiveness challenge. “The nose is highly cycling,” said Dr. Hindle. “Anything we deposit usually gets transported out within 15-20 minutes.”

For kids – big fans of not using needles – chronically runny noses can be an issue. “You squirt it in the nose, and it will probably just come back out in their snot,” said Jay Kolls, MD, a professor of medicine and pediatrics at Tulane University, New Orleans, who is developing an intranasal pneumonia vaccine.

Even so, nasal vaccines became a hot topic among researchers after the world was shut down by a virus that invades through the nose.

“We realized that intramuscular vaccines were effective at preventing severe disease, but they weren’t that effective at preventing transmission,” said Michael Diamond, MD, PhD, an immunologist at Washington University in St. Louis.

Nasal vaccines could solve that problem by putting an immune barrier at the point of entry, denying access to the rest of the body. “You squash the infection early enough that it not only prevents disease,” said Dr. Kolls, “but potentially prevents transmission.”

And yes, a nasal COVID vaccine is on the way

In March 2020, Dr. Diamond’s team began exploring a nasal COVID vaccine. Promising results in animals prompted a vaccine development company to license the technology. The resulting nasal vaccine – the first for COVID – has been approved in India, both as a primary vaccine and a booster.

It works by stimulating an influx of IgA, a type of antibody found in the nasal passages, and production of resident memory T cells, immune cells on standby just beneath the surface tissue in the nose.

By contrast, injected vaccines generate mostly IgG antibodies, which struggle to enter the respiratory tract. Only a tiny fraction – an estimated 1% – typically reach the nose.

Nasal vaccines could also be used along with shots. The latter could prime the whole body to fight back, while a nasal spritz could pull that immune protection to the mucosal surfaces.

Nasal technology could yield more effective vaccines for infections like tuberculosis or malaria, or even safeguard against new – sometimes surprising – conditions.

In a 2021 Nature study, an intranasal vaccine derived from fentanyl was better at preventing overdose than an injected vaccine. “Through some clever chemistry, the drug [in the vaccine] isn’t fentanyl anymore,” said study author Elizabeth Norton, PhD, an assistant professor of microbiology and immunology at Tulane University. “But the immune system still has an antibody response to it.”

Novel applications like this represent the future of nasal drug delivery.

“We’re not going to innovate in asthma or COPD. We’re not going to innovate in local delivery to the nose,” said Dr. Hindle. “Innovation will only come if we look to treat new conditions.”

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

West Nile virus cases rising nationwide amid mosquito season

In the past 2 weeks, new cases have been reported in Iowa and Nebraska, adding to previous 2023 reports from Arizona, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Wyoming. A mosquito at a monitoring site near Houston tested positive last week for the potentially fatal virus, prompting local health officials to begin evening spray operations in the area where the mosquito was found, according to an announcement from Harris County Public Health.

According to the CDC, which compiles local reports, there have been 13 human cases of West Nile virus in 2023. In 2022, there were 1,126 cases, including 90 deaths.