User login

American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology (AAAAI): Annual Meeting

Breastfeeding-related changes in gut bacteria protect against childhood allergy

HOUSTON – Findings from a cohort study of mothers and babies point to breastfeeding as influencing infants’ gut microbiome in a way that protects them from developing allergic disease.

In findings presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, epidemiologist Christine Cole Johnson, Ph.D., of the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit described a correlation between certain maternal and birth characteristics that had previously been shown to relate to allergic response, and measurable differences in the bacterial profiles of the study infants’ stools.

Using data from the WHEALS (Wayne County [Michigan] Health, Environment, Allergy, and Asthma Longitudinal Study) cohort, Dr. Johnson and her colleagues looked at stool samples from 298 children at 1 and 6 months of age. The investigators also collected dust samples from the infants’ homes, obtained medical records, and conducted interviews with the families (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015 [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1443]).

The presence of household pets, the body mass index of mothers before delivery, the mode of delivery, household smoke exposure, marital status, income, race, and maternal education were all found to be significantly correlated to different gut bacterial profiles.

“Environmental and lifestyle variables that we’ve been working on related to childhood asthma and allergy seem to be associated – at least in our study – with the child’s gut microbiome,” Dr. Johnson said. “These factors vary a lot by whether those stool samples were collected at 1 or 6 months,” she said, noting that the infant gut microbiome is shaped rapidly in the first year.

But, at both 1 and 6 months of age, breastfeeding was seen as the dominant factor influencing gut bacterial composition.

At 6 months, breastfed infants had bacterial profiles showing overwhelming dominance of Bifidobacteriaceae, but vastly lower levels of other families of bacteria, notably Lachnospiraceae, which were prominent in the guts of non-breastfed babies.

In a related study that used the same cohort to explore whether the influence of breastfeeding on gut bacterial composition correlated to the development of allergic symptoms at 4 years old, Alexandra R. Sitarik, also of the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, reported that babies being breastfed at 1 month of age had a significantly lower risk of developing allergiclike symptoms to pets by age 4 years (P = .028) (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015 [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1444]).

Both breastfeeding and allergiclike response to pets were significantly related to compositional variation in gut microbiome (P < .001 and P = .023, respectively), Ms. Sitarik reported.

Of the 109 types of bacteria significantly associated with both breastfeeding and allergiclike response to pets, 71% were negatively associated with breastfeeding but positively associated with allergiclike response to pets.

This subset of risk-increasing bacteria suppressed by breastfeeding were predominantly members of the family Lachnospiraceae, the researchers found.

Lachnospiraceae are common adult gut colonizers, Ms. Sitarik said, and as people age the relative abundance of Lachnospiraceae increases. “What we think might be happening in terms of the gut microbiome is that maybe breastfeeding is preventing this premature shift into adulthood,” she said.

Dr. Johnson and Ms. Sitarik reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – Findings from a cohort study of mothers and babies point to breastfeeding as influencing infants’ gut microbiome in a way that protects them from developing allergic disease.

In findings presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, epidemiologist Christine Cole Johnson, Ph.D., of the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit described a correlation between certain maternal and birth characteristics that had previously been shown to relate to allergic response, and measurable differences in the bacterial profiles of the study infants’ stools.

Using data from the WHEALS (Wayne County [Michigan] Health, Environment, Allergy, and Asthma Longitudinal Study) cohort, Dr. Johnson and her colleagues looked at stool samples from 298 children at 1 and 6 months of age. The investigators also collected dust samples from the infants’ homes, obtained medical records, and conducted interviews with the families (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015 [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1443]).

The presence of household pets, the body mass index of mothers before delivery, the mode of delivery, household smoke exposure, marital status, income, race, and maternal education were all found to be significantly correlated to different gut bacterial profiles.

“Environmental and lifestyle variables that we’ve been working on related to childhood asthma and allergy seem to be associated – at least in our study – with the child’s gut microbiome,” Dr. Johnson said. “These factors vary a lot by whether those stool samples were collected at 1 or 6 months,” she said, noting that the infant gut microbiome is shaped rapidly in the first year.

But, at both 1 and 6 months of age, breastfeeding was seen as the dominant factor influencing gut bacterial composition.

At 6 months, breastfed infants had bacterial profiles showing overwhelming dominance of Bifidobacteriaceae, but vastly lower levels of other families of bacteria, notably Lachnospiraceae, which were prominent in the guts of non-breastfed babies.

In a related study that used the same cohort to explore whether the influence of breastfeeding on gut bacterial composition correlated to the development of allergic symptoms at 4 years old, Alexandra R. Sitarik, also of the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, reported that babies being breastfed at 1 month of age had a significantly lower risk of developing allergiclike symptoms to pets by age 4 years (P = .028) (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015 [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1444]).

Both breastfeeding and allergiclike response to pets were significantly related to compositional variation in gut microbiome (P < .001 and P = .023, respectively), Ms. Sitarik reported.

Of the 109 types of bacteria significantly associated with both breastfeeding and allergiclike response to pets, 71% were negatively associated with breastfeeding but positively associated with allergiclike response to pets.

This subset of risk-increasing bacteria suppressed by breastfeeding were predominantly members of the family Lachnospiraceae, the researchers found.

Lachnospiraceae are common adult gut colonizers, Ms. Sitarik said, and as people age the relative abundance of Lachnospiraceae increases. “What we think might be happening in terms of the gut microbiome is that maybe breastfeeding is preventing this premature shift into adulthood,” she said.

Dr. Johnson and Ms. Sitarik reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – Findings from a cohort study of mothers and babies point to breastfeeding as influencing infants’ gut microbiome in a way that protects them from developing allergic disease.

In findings presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, epidemiologist Christine Cole Johnson, Ph.D., of the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit described a correlation between certain maternal and birth characteristics that had previously been shown to relate to allergic response, and measurable differences in the bacterial profiles of the study infants’ stools.

Using data from the WHEALS (Wayne County [Michigan] Health, Environment, Allergy, and Asthma Longitudinal Study) cohort, Dr. Johnson and her colleagues looked at stool samples from 298 children at 1 and 6 months of age. The investigators also collected dust samples from the infants’ homes, obtained medical records, and conducted interviews with the families (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015 [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1443]).

The presence of household pets, the body mass index of mothers before delivery, the mode of delivery, household smoke exposure, marital status, income, race, and maternal education were all found to be significantly correlated to different gut bacterial profiles.

“Environmental and lifestyle variables that we’ve been working on related to childhood asthma and allergy seem to be associated – at least in our study – with the child’s gut microbiome,” Dr. Johnson said. “These factors vary a lot by whether those stool samples were collected at 1 or 6 months,” she said, noting that the infant gut microbiome is shaped rapidly in the first year.

But, at both 1 and 6 months of age, breastfeeding was seen as the dominant factor influencing gut bacterial composition.

At 6 months, breastfed infants had bacterial profiles showing overwhelming dominance of Bifidobacteriaceae, but vastly lower levels of other families of bacteria, notably Lachnospiraceae, which were prominent in the guts of non-breastfed babies.

In a related study that used the same cohort to explore whether the influence of breastfeeding on gut bacterial composition correlated to the development of allergic symptoms at 4 years old, Alexandra R. Sitarik, also of the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, reported that babies being breastfed at 1 month of age had a significantly lower risk of developing allergiclike symptoms to pets by age 4 years (P = .028) (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015 [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1444]).

Both breastfeeding and allergiclike response to pets were significantly related to compositional variation in gut microbiome (P < .001 and P = .023, respectively), Ms. Sitarik reported.

Of the 109 types of bacteria significantly associated with both breastfeeding and allergiclike response to pets, 71% were negatively associated with breastfeeding but positively associated with allergiclike response to pets.

This subset of risk-increasing bacteria suppressed by breastfeeding were predominantly members of the family Lachnospiraceae, the researchers found.

Lachnospiraceae are common adult gut colonizers, Ms. Sitarik said, and as people age the relative abundance of Lachnospiraceae increases. “What we think might be happening in terms of the gut microbiome is that maybe breastfeeding is preventing this premature shift into adulthood,” she said.

Dr. Johnson and Ms. Sitarik reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE 2015 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Breastfeeding helps to alter the gut microbiome of infants, protecting them from pet allergies in childhood.

Major finding: Infants breastfed at 1 month of age had a significantly lower risk of being allergic to household pets at age 4 years (P =.028).

Data source: Data and stool samples from 298 infants enrolled in the Wayne County [Michigan] Health, Environment, Allergy, and Asthma Longitudinal Study (WHEALS) study.

Disclosures: The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

Skin patch therapy for peanut allergy wins plaudits

HOUSTON – A peanut protein–bearing skin patch showed considerable promise in the largest randomized trial to date of any potential treatment for peanut allergy.

One year of treatment with the investigational proprietary Viaskin Peanut skin patch raised the threshold of exposure to peanut protein required to elicit an allergic reaction to a level that patients and families would consider life changing, Dr. Hugh A. Sampson said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

“One of the biggest problems for the family of a patient with peanut allergy is the fear of getting contamination. If they could rest assured that they could tolerate something like a gram’s worth of contamination with peanut protein, much of that concern would go away. They could go to restaurants and birthday parties. They still need to be vigilant and tell people they’re peanut allergic, but the chance of these low-level contaminations that lead to most of the reactions we see would largely be taken care of,” said Dr. Sampson, professor of pediatrics, allergy, and immunology and dean for translational biomedical research at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

He presented the findings of a phase IIb randomized, double-blind, multinational, placebo-controlled trial of what is being called epicutaneous immunotherapy. The trial involved 221 subjects with documented peanut allergy. Roughly half were aged 6-11 years; the rest were adolescents and adults up to age 55. They were randomized to one of four study arms: the skin patch at a dose of 50, 100, or 250 mcg or a placebo patch. As a requirement for study participation, all subjects had to have a peanut protein reaction–eliciting dose of 300 mg or less on baseline formal oral peanut challenge testing; half of the children reacted to 30 mg or less.

The primary endpoint was the ability to tolerate on a repeat oral challenge at 1 year either at least 1 g of peanut protein or 10 times the amount they tolerated on baseline testing. In the overall study population, the 250-mcg patch was the top performer. It was the only patch dose significantly better than placebo: 50% of all patients on the 250-mcg patch met the primary endpoint, compared with 25% of placebo-treated controls.

Peanut allergy typically starts early in life, so it’s noteworthy that the children in the study had a markedly more robust response to epicutaneous immunotherapy than the older patients. Indeed, among the 6- to 11-year-olds, all three patch doses outperformed placebo. The mean cumulative dose of peanut protein required to elicit a reaction on structured oral challenge testing was 1,121 mg greater at 1 year than at baseline among children on the 250-mcg patch, 570 mg greater with the 100-mcg patch, and 471 mg greater than at baseline among those using the 50-mcg patch.

Similarly, a robust dose-dependent increase was seen in protective peanut-specific IgG4 levels in response to 1 year of epicutaneous immunotherapy. The median level of this biomarker of therapeutic benefit climbed 19-fold over baseline in children on the 250-mcg patch, 7-fold with the 100-mcg patch, and 5.5-fold with the 50-mcg patch.

The compliance rate with patch therapy was greater than 96%. Only 2 of the 221 participants dropped out of the study due to adverse events, both because of a flare of atopic dermatitis around the patch site. There were no serious adverse events in the study.

The trial is being extended for a second year of immunotherapy. “My anticipation based on what we see with other forms of immunotherapy is that we might very well see even more protection,” according to Dr. Sampson.

In an interview, he said he’d like to see the skin patch studied at doses above 250 mcg in adolescents and adults.

“I would also love to see epicutaneous immunotherapy looked at in very young children,” he added. “You get a much better response, and it may be longer lasting because we think that the immune system in an infant is much more plastic than it is once they get older. Trying to reverse a set response is much more difficult.”

The skin patch is about the size of a small, round Band-Aid. It is placed over the back or inner upper arm and changed daily. The concept is that as humidity develops under the patch, a small amount of peanut protein permeates the outer skin. Langerhans cells then pick it up and transport it to regional lymph nodes, where T cells can activate desensitization.

“I think this concept of using a low amount of protein in a convenient, safe way could change the way we do immunotherapy,” Dr. Sampson predicted.

Asked to comment, peanut allergy researcher Dr. Brian P. Vickery of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, agreed with Dr. Sampson’s assessment that patch therapy could be a game changer, especially given that there is no FDA-approved treatment for peanut allergy.

“Right now the standard of care is avoidance. So anything that improves upon that to allow a margin of safety that lets a patient get along in the world with the reassurance that a contamination event up to, say, a gram would be well tolerated would be transformative,” he said.

HOUSTON – A peanut protein–bearing skin patch showed considerable promise in the largest randomized trial to date of any potential treatment for peanut allergy.

One year of treatment with the investigational proprietary Viaskin Peanut skin patch raised the threshold of exposure to peanut protein required to elicit an allergic reaction to a level that patients and families would consider life changing, Dr. Hugh A. Sampson said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

“One of the biggest problems for the family of a patient with peanut allergy is the fear of getting contamination. If they could rest assured that they could tolerate something like a gram’s worth of contamination with peanut protein, much of that concern would go away. They could go to restaurants and birthday parties. They still need to be vigilant and tell people they’re peanut allergic, but the chance of these low-level contaminations that lead to most of the reactions we see would largely be taken care of,” said Dr. Sampson, professor of pediatrics, allergy, and immunology and dean for translational biomedical research at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

He presented the findings of a phase IIb randomized, double-blind, multinational, placebo-controlled trial of what is being called epicutaneous immunotherapy. The trial involved 221 subjects with documented peanut allergy. Roughly half were aged 6-11 years; the rest were adolescents and adults up to age 55. They were randomized to one of four study arms: the skin patch at a dose of 50, 100, or 250 mcg or a placebo patch. As a requirement for study participation, all subjects had to have a peanut protein reaction–eliciting dose of 300 mg or less on baseline formal oral peanut challenge testing; half of the children reacted to 30 mg or less.

The primary endpoint was the ability to tolerate on a repeat oral challenge at 1 year either at least 1 g of peanut protein or 10 times the amount they tolerated on baseline testing. In the overall study population, the 250-mcg patch was the top performer. It was the only patch dose significantly better than placebo: 50% of all patients on the 250-mcg patch met the primary endpoint, compared with 25% of placebo-treated controls.

Peanut allergy typically starts early in life, so it’s noteworthy that the children in the study had a markedly more robust response to epicutaneous immunotherapy than the older patients. Indeed, among the 6- to 11-year-olds, all three patch doses outperformed placebo. The mean cumulative dose of peanut protein required to elicit a reaction on structured oral challenge testing was 1,121 mg greater at 1 year than at baseline among children on the 250-mcg patch, 570 mg greater with the 100-mcg patch, and 471 mg greater than at baseline among those using the 50-mcg patch.

Similarly, a robust dose-dependent increase was seen in protective peanut-specific IgG4 levels in response to 1 year of epicutaneous immunotherapy. The median level of this biomarker of therapeutic benefit climbed 19-fold over baseline in children on the 250-mcg patch, 7-fold with the 100-mcg patch, and 5.5-fold with the 50-mcg patch.

The compliance rate with patch therapy was greater than 96%. Only 2 of the 221 participants dropped out of the study due to adverse events, both because of a flare of atopic dermatitis around the patch site. There were no serious adverse events in the study.

The trial is being extended for a second year of immunotherapy. “My anticipation based on what we see with other forms of immunotherapy is that we might very well see even more protection,” according to Dr. Sampson.

In an interview, he said he’d like to see the skin patch studied at doses above 250 mcg in adolescents and adults.

“I would also love to see epicutaneous immunotherapy looked at in very young children,” he added. “You get a much better response, and it may be longer lasting because we think that the immune system in an infant is much more plastic than it is once they get older. Trying to reverse a set response is much more difficult.”

The skin patch is about the size of a small, round Band-Aid. It is placed over the back or inner upper arm and changed daily. The concept is that as humidity develops under the patch, a small amount of peanut protein permeates the outer skin. Langerhans cells then pick it up and transport it to regional lymph nodes, where T cells can activate desensitization.

“I think this concept of using a low amount of protein in a convenient, safe way could change the way we do immunotherapy,” Dr. Sampson predicted.

Asked to comment, peanut allergy researcher Dr. Brian P. Vickery of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, agreed with Dr. Sampson’s assessment that patch therapy could be a game changer, especially given that there is no FDA-approved treatment for peanut allergy.

“Right now the standard of care is avoidance. So anything that improves upon that to allow a margin of safety that lets a patient get along in the world with the reassurance that a contamination event up to, say, a gram would be well tolerated would be transformative,” he said.

HOUSTON – A peanut protein–bearing skin patch showed considerable promise in the largest randomized trial to date of any potential treatment for peanut allergy.

One year of treatment with the investigational proprietary Viaskin Peanut skin patch raised the threshold of exposure to peanut protein required to elicit an allergic reaction to a level that patients and families would consider life changing, Dr. Hugh A. Sampson said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

“One of the biggest problems for the family of a patient with peanut allergy is the fear of getting contamination. If they could rest assured that they could tolerate something like a gram’s worth of contamination with peanut protein, much of that concern would go away. They could go to restaurants and birthday parties. They still need to be vigilant and tell people they’re peanut allergic, but the chance of these low-level contaminations that lead to most of the reactions we see would largely be taken care of,” said Dr. Sampson, professor of pediatrics, allergy, and immunology and dean for translational biomedical research at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

He presented the findings of a phase IIb randomized, double-blind, multinational, placebo-controlled trial of what is being called epicutaneous immunotherapy. The trial involved 221 subjects with documented peanut allergy. Roughly half were aged 6-11 years; the rest were adolescents and adults up to age 55. They were randomized to one of four study arms: the skin patch at a dose of 50, 100, or 250 mcg or a placebo patch. As a requirement for study participation, all subjects had to have a peanut protein reaction–eliciting dose of 300 mg or less on baseline formal oral peanut challenge testing; half of the children reacted to 30 mg or less.

The primary endpoint was the ability to tolerate on a repeat oral challenge at 1 year either at least 1 g of peanut protein or 10 times the amount they tolerated on baseline testing. In the overall study population, the 250-mcg patch was the top performer. It was the only patch dose significantly better than placebo: 50% of all patients on the 250-mcg patch met the primary endpoint, compared with 25% of placebo-treated controls.

Peanut allergy typically starts early in life, so it’s noteworthy that the children in the study had a markedly more robust response to epicutaneous immunotherapy than the older patients. Indeed, among the 6- to 11-year-olds, all three patch doses outperformed placebo. The mean cumulative dose of peanut protein required to elicit a reaction on structured oral challenge testing was 1,121 mg greater at 1 year than at baseline among children on the 250-mcg patch, 570 mg greater with the 100-mcg patch, and 471 mg greater than at baseline among those using the 50-mcg patch.

Similarly, a robust dose-dependent increase was seen in protective peanut-specific IgG4 levels in response to 1 year of epicutaneous immunotherapy. The median level of this biomarker of therapeutic benefit climbed 19-fold over baseline in children on the 250-mcg patch, 7-fold with the 100-mcg patch, and 5.5-fold with the 50-mcg patch.

The compliance rate with patch therapy was greater than 96%. Only 2 of the 221 participants dropped out of the study due to adverse events, both because of a flare of atopic dermatitis around the patch site. There were no serious adverse events in the study.

The trial is being extended for a second year of immunotherapy. “My anticipation based on what we see with other forms of immunotherapy is that we might very well see even more protection,” according to Dr. Sampson.

In an interview, he said he’d like to see the skin patch studied at doses above 250 mcg in adolescents and adults.

“I would also love to see epicutaneous immunotherapy looked at in very young children,” he added. “You get a much better response, and it may be longer lasting because we think that the immune system in an infant is much more plastic than it is once they get older. Trying to reverse a set response is much more difficult.”

The skin patch is about the size of a small, round Band-Aid. It is placed over the back or inner upper arm and changed daily. The concept is that as humidity develops under the patch, a small amount of peanut protein permeates the outer skin. Langerhans cells then pick it up and transport it to regional lymph nodes, where T cells can activate desensitization.

“I think this concept of using a low amount of protein in a convenient, safe way could change the way we do immunotherapy,” Dr. Sampson predicted.

Asked to comment, peanut allergy researcher Dr. Brian P. Vickery of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, agreed with Dr. Sampson’s assessment that patch therapy could be a game changer, especially given that there is no FDA-approved treatment for peanut allergy.

“Right now the standard of care is avoidance. So anything that improves upon that to allow a margin of safety that lets a patient get along in the world with the reassurance that a contamination event up to, say, a gram would be well tolerated would be transformative,” he said.

AT 2015 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Epicutaneous immunotherapy in patients with peanut allergy is safe, well-tolerated, and shows dose- and age-dependent efficacy.

Major finding: Half of peanut-allergic patients who wore a proprietary skin patch containing 250 mcg of peanut protein experienced a clinically meaningful increase in the threshold of exposure required to elicit a reaction, compared with 25% of controls using a placebo patch. The results were more dramatic in children than older subjects.

Data source: This was a 12-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multinational phase IIb study involving 221 peanut-allergic patients aged 6-55 years.

Disclosures: The study was funded by DBV Technologies. The presenter reported serving as an unpaid member of the company’s scientific advisory board.

Atopic dermatitis treated with experimental microbial therapy

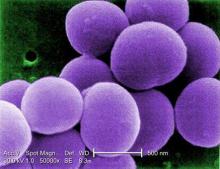

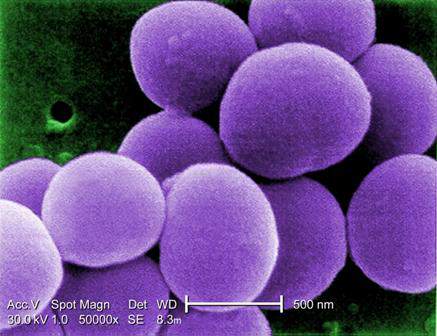

HOUSTON – New science suggests that the skin microbial environment may be manipulated in patients with atopic dermatitis in a way that could quell overgrowth of Staphylococcus aureus – meaning that the first microbiome-based therapies for AD might not be far away.

Dr. Richard L. Gallo, professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, described preliminary findings that the skin microbiome functions differently in patients with AD than in those without.

Dr. Gallo and his colleagues took skin sloughs from 50 AD patients and 30 non-AD controls. Most of the Staphylococcus aureus bacteria on sloughs from AD patients were alive, while most were dead on sloughs from patients without AD. Normal subjects had skin biomes that were able to kill S. aureus, Dr. Gallo said in a plenary talk at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The investigators looked at the few species of normally occurring skin bacteria that can kill S. aureus, focusing on Staphylococcus hominis, which, they found, produces an antimicrobial peptide very effective against S. aureus. After mouse experiments showed S. hominis effective against S. aureus infection, Dr. Gallo and his colleagues began investigating its activity in a human patient. They isolated S. hominis from the skin of a patient, cultured it, and applied it in a topical cream. The result was a 1,000-fold drop in S. aureus colonization in the same patient. Dr. Gallo did not say how long the effect lasted or whether clinical symptoms abated.

“The pharmaceutical industry has been looking for antimicrobials in the jungles and the deep sea,” Dr. Gallo said. “We just swabbed an arm and found one that was really effective.” The findings suggest, he said, that “perhaps there are some therapeutic opportunities using the skin microbiome that aren’t 5 years away.” He added that his team has funding from NIH to continue this work as well as for a larger study using a similar approach that will be applicable in larger populations.

Dr. Gallo also mentioned new research showing that the skin microbiome goes quite a bit deeper than commonly understood, with immune-mediating bacteria found in the dermis and even the adipose layers. “We have to start thinking about skin in a different way,” he said. “These are not absolute barriers but highly evolved filters that permit selected microbes to interact.” Dr. Gallo has received research support from Galderma and Bayer and is listed on several patents for potential therapies held by his institution.

HOUSTON – New science suggests that the skin microbial environment may be manipulated in patients with atopic dermatitis in a way that could quell overgrowth of Staphylococcus aureus – meaning that the first microbiome-based therapies for AD might not be far away.

Dr. Richard L. Gallo, professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, described preliminary findings that the skin microbiome functions differently in patients with AD than in those without.

Dr. Gallo and his colleagues took skin sloughs from 50 AD patients and 30 non-AD controls. Most of the Staphylococcus aureus bacteria on sloughs from AD patients were alive, while most were dead on sloughs from patients without AD. Normal subjects had skin biomes that were able to kill S. aureus, Dr. Gallo said in a plenary talk at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The investigators looked at the few species of normally occurring skin bacteria that can kill S. aureus, focusing on Staphylococcus hominis, which, they found, produces an antimicrobial peptide very effective against S. aureus. After mouse experiments showed S. hominis effective against S. aureus infection, Dr. Gallo and his colleagues began investigating its activity in a human patient. They isolated S. hominis from the skin of a patient, cultured it, and applied it in a topical cream. The result was a 1,000-fold drop in S. aureus colonization in the same patient. Dr. Gallo did not say how long the effect lasted or whether clinical symptoms abated.

“The pharmaceutical industry has been looking for antimicrobials in the jungles and the deep sea,” Dr. Gallo said. “We just swabbed an arm and found one that was really effective.” The findings suggest, he said, that “perhaps there are some therapeutic opportunities using the skin microbiome that aren’t 5 years away.” He added that his team has funding from NIH to continue this work as well as for a larger study using a similar approach that will be applicable in larger populations.

Dr. Gallo also mentioned new research showing that the skin microbiome goes quite a bit deeper than commonly understood, with immune-mediating bacteria found in the dermis and even the adipose layers. “We have to start thinking about skin in a different way,” he said. “These are not absolute barriers but highly evolved filters that permit selected microbes to interact.” Dr. Gallo has received research support from Galderma and Bayer and is listed on several patents for potential therapies held by his institution.

HOUSTON – New science suggests that the skin microbial environment may be manipulated in patients with atopic dermatitis in a way that could quell overgrowth of Staphylococcus aureus – meaning that the first microbiome-based therapies for AD might not be far away.

Dr. Richard L. Gallo, professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, described preliminary findings that the skin microbiome functions differently in patients with AD than in those without.

Dr. Gallo and his colleagues took skin sloughs from 50 AD patients and 30 non-AD controls. Most of the Staphylococcus aureus bacteria on sloughs from AD patients were alive, while most were dead on sloughs from patients without AD. Normal subjects had skin biomes that were able to kill S. aureus, Dr. Gallo said in a plenary talk at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The investigators looked at the few species of normally occurring skin bacteria that can kill S. aureus, focusing on Staphylococcus hominis, which, they found, produces an antimicrobial peptide very effective against S. aureus. After mouse experiments showed S. hominis effective against S. aureus infection, Dr. Gallo and his colleagues began investigating its activity in a human patient. They isolated S. hominis from the skin of a patient, cultured it, and applied it in a topical cream. The result was a 1,000-fold drop in S. aureus colonization in the same patient. Dr. Gallo did not say how long the effect lasted or whether clinical symptoms abated.

“The pharmaceutical industry has been looking for antimicrobials in the jungles and the deep sea,” Dr. Gallo said. “We just swabbed an arm and found one that was really effective.” The findings suggest, he said, that “perhaps there are some therapeutic opportunities using the skin microbiome that aren’t 5 years away.” He added that his team has funding from NIH to continue this work as well as for a larger study using a similar approach that will be applicable in larger populations.

Dr. Gallo also mentioned new research showing that the skin microbiome goes quite a bit deeper than commonly understood, with immune-mediating bacteria found in the dermis and even the adipose layers. “We have to start thinking about skin in a different way,” he said. “These are not absolute barriers but highly evolved filters that permit selected microbes to interact.” Dr. Gallo has received research support from Galderma and Bayer and is listed on several patents for potential therapies held by his institution.

AT 2015 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Get the baby a dog: Infants’ gut biota seen to affect allergy risk

HOUSTON – The specific bacterial composition of infants’ gut biomes may be key to their developing or not developing allergic disease in early childhood, supporting what researchers called “a gut-airway axis” for allergic disease.

In preliminary, unpublished findings, Susan V. Lynch, Ph.D., of the department of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues looked at stool samples from 298 infants aged between 0 and 11 months. They measured gut bacterial diversity, distribution, and richness at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months. Gut bacteria diversified rapidly and steadily during this time, the researchers found.

"The dramatic diversification that occurs during the first year of life is the peak period of plasticity of microbial accumulation," Dr. Lynch said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. The composition of the gut microbiomes was significantly related to the age of the infants.

Dr. Lynch's group found that in infants less than 6 months of age gut biomes were dominated by Bifidobacteriaceae (70 infants), Enterobacteriaceae (49), or codominated by both (11). Gut composition related to the types of microbial exposures in the home and was affected by the presence or absence of furred pets, particularly dogs, Dr. Lynch said.

Infants without pets in the home were most likely to have a codominated biome, with a relative risk of multiple sensitization of 2.94 when compared with infants with a Bifidobacteriaeae biome and 2.06 compared with those with a Enterobacteriaceae-dominated biome.

“We asked is there a clinical correlate? Yes. That codominated community runs the highest risk of allergic disease development at age 2, having a significantly increased risk ratio, compared with either of the singly dominated communities,” Dr. Lynch said.

Moreover, the different bacterial profiles were responsible for observed differences in gut function. “We find very dramatic differences in carbohydrate and fatty acid metabolism in these communities for which atopy risk is highest,” Dr. Lynch said. “Perhaps the foundation for atopic development in childhood is associated with a compositionally distinct and highly dysfunctional neonatal gut.”

The potential for intervention is highest in the first year of life when the microbiome is most plastic, Dr. Lynch said; however, she declined to speculate what such interventions might amount to, noting that it was too early.

At the same talk, Dr. Erika Von Mutius, medical director of the asthma and allergy clinic at the University of Munich in Germany, described her work with children growing up on European farms, whom decades worth of studies have shown to have both higher diversity and frequency of microbial exposure and also lower risk of asthma and allergies than children raised in non-farm environments.

Dr. Von Mutius reported that her research group is beginning to pinpoint the protective microbes detected in these children’s’ environments and also their respiratory tracts.

A handful of organisms appear to work in concert as a microbial cocktail that predicts lower asthma and allergy rates. “What we’re seeing here is not the needle in the haystack, it’s not the one thing that will protect [from disease]. The question is, is the more the better, or is it like a soup, in which certain components are more important?’ We think it’s more like a soup,” she said.

The way in which these microbes work in the body to become protective is unknown, said Dr. Von Mutius, whose current research is looking at nose and throat samples from children. Dr. Von Mutius and her colleagues found more than fourfold more microbial diversity in farm children’s noses than their throats, though, she said, they did not yet understand why.

“The more diversity in the nose, the less asthma these children had,” she said, adding that it remained to be learned “whether you can do something in the nose to affect asthma” or whether lower respiratory and/or gut processes were key to mediating asthma risk. Dr. Lynch has received support or other funding from Second Genome, Janssen, Regeneron, and KaloBios. Dr. Von Mutius has received fees or support from ALK, Nestle, Airsonett, Protectimmun, and Novartis.

HOUSTON – The specific bacterial composition of infants’ gut biomes may be key to their developing or not developing allergic disease in early childhood, supporting what researchers called “a gut-airway axis” for allergic disease.

In preliminary, unpublished findings, Susan V. Lynch, Ph.D., of the department of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues looked at stool samples from 298 infants aged between 0 and 11 months. They measured gut bacterial diversity, distribution, and richness at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months. Gut bacteria diversified rapidly and steadily during this time, the researchers found.

"The dramatic diversification that occurs during the first year of life is the peak period of plasticity of microbial accumulation," Dr. Lynch said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. The composition of the gut microbiomes was significantly related to the age of the infants.

Dr. Lynch's group found that in infants less than 6 months of age gut biomes were dominated by Bifidobacteriaceae (70 infants), Enterobacteriaceae (49), or codominated by both (11). Gut composition related to the types of microbial exposures in the home and was affected by the presence or absence of furred pets, particularly dogs, Dr. Lynch said.

Infants without pets in the home were most likely to have a codominated biome, with a relative risk of multiple sensitization of 2.94 when compared with infants with a Bifidobacteriaeae biome and 2.06 compared with those with a Enterobacteriaceae-dominated biome.

“We asked is there a clinical correlate? Yes. That codominated community runs the highest risk of allergic disease development at age 2, having a significantly increased risk ratio, compared with either of the singly dominated communities,” Dr. Lynch said.

Moreover, the different bacterial profiles were responsible for observed differences in gut function. “We find very dramatic differences in carbohydrate and fatty acid metabolism in these communities for which atopy risk is highest,” Dr. Lynch said. “Perhaps the foundation for atopic development in childhood is associated with a compositionally distinct and highly dysfunctional neonatal gut.”

The potential for intervention is highest in the first year of life when the microbiome is most plastic, Dr. Lynch said; however, she declined to speculate what such interventions might amount to, noting that it was too early.

At the same talk, Dr. Erika Von Mutius, medical director of the asthma and allergy clinic at the University of Munich in Germany, described her work with children growing up on European farms, whom decades worth of studies have shown to have both higher diversity and frequency of microbial exposure and also lower risk of asthma and allergies than children raised in non-farm environments.

Dr. Von Mutius reported that her research group is beginning to pinpoint the protective microbes detected in these children’s’ environments and also their respiratory tracts.

A handful of organisms appear to work in concert as a microbial cocktail that predicts lower asthma and allergy rates. “What we’re seeing here is not the needle in the haystack, it’s not the one thing that will protect [from disease]. The question is, is the more the better, or is it like a soup, in which certain components are more important?’ We think it’s more like a soup,” she said.

The way in which these microbes work in the body to become protective is unknown, said Dr. Von Mutius, whose current research is looking at nose and throat samples from children. Dr. Von Mutius and her colleagues found more than fourfold more microbial diversity in farm children’s noses than their throats, though, she said, they did not yet understand why.

“The more diversity in the nose, the less asthma these children had,” she said, adding that it remained to be learned “whether you can do something in the nose to affect asthma” or whether lower respiratory and/or gut processes were key to mediating asthma risk. Dr. Lynch has received support or other funding from Second Genome, Janssen, Regeneron, and KaloBios. Dr. Von Mutius has received fees or support from ALK, Nestle, Airsonett, Protectimmun, and Novartis.

HOUSTON – The specific bacterial composition of infants’ gut biomes may be key to their developing or not developing allergic disease in early childhood, supporting what researchers called “a gut-airway axis” for allergic disease.

In preliminary, unpublished findings, Susan V. Lynch, Ph.D., of the department of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues looked at stool samples from 298 infants aged between 0 and 11 months. They measured gut bacterial diversity, distribution, and richness at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months. Gut bacteria diversified rapidly and steadily during this time, the researchers found.

"The dramatic diversification that occurs during the first year of life is the peak period of plasticity of microbial accumulation," Dr. Lynch said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. The composition of the gut microbiomes was significantly related to the age of the infants.

Dr. Lynch's group found that in infants less than 6 months of age gut biomes were dominated by Bifidobacteriaceae (70 infants), Enterobacteriaceae (49), or codominated by both (11). Gut composition related to the types of microbial exposures in the home and was affected by the presence or absence of furred pets, particularly dogs, Dr. Lynch said.

Infants without pets in the home were most likely to have a codominated biome, with a relative risk of multiple sensitization of 2.94 when compared with infants with a Bifidobacteriaeae biome and 2.06 compared with those with a Enterobacteriaceae-dominated biome.

“We asked is there a clinical correlate? Yes. That codominated community runs the highest risk of allergic disease development at age 2, having a significantly increased risk ratio, compared with either of the singly dominated communities,” Dr. Lynch said.

Moreover, the different bacterial profiles were responsible for observed differences in gut function. “We find very dramatic differences in carbohydrate and fatty acid metabolism in these communities for which atopy risk is highest,” Dr. Lynch said. “Perhaps the foundation for atopic development in childhood is associated with a compositionally distinct and highly dysfunctional neonatal gut.”

The potential for intervention is highest in the first year of life when the microbiome is most plastic, Dr. Lynch said; however, she declined to speculate what such interventions might amount to, noting that it was too early.

At the same talk, Dr. Erika Von Mutius, medical director of the asthma and allergy clinic at the University of Munich in Germany, described her work with children growing up on European farms, whom decades worth of studies have shown to have both higher diversity and frequency of microbial exposure and also lower risk of asthma and allergies than children raised in non-farm environments.

Dr. Von Mutius reported that her research group is beginning to pinpoint the protective microbes detected in these children’s’ environments and also their respiratory tracts.

A handful of organisms appear to work in concert as a microbial cocktail that predicts lower asthma and allergy rates. “What we’re seeing here is not the needle in the haystack, it’s not the one thing that will protect [from disease]. The question is, is the more the better, or is it like a soup, in which certain components are more important?’ We think it’s more like a soup,” she said.

The way in which these microbes work in the body to become protective is unknown, said Dr. Von Mutius, whose current research is looking at nose and throat samples from children. Dr. Von Mutius and her colleagues found more than fourfold more microbial diversity in farm children’s noses than their throats, though, she said, they did not yet understand why.

“The more diversity in the nose, the less asthma these children had,” she said, adding that it remained to be learned “whether you can do something in the nose to affect asthma” or whether lower respiratory and/or gut processes were key to mediating asthma risk. Dr. Lynch has received support or other funding from Second Genome, Janssen, Regeneron, and KaloBios. Dr. Von Mutius has received fees or support from ALK, Nestle, Airsonett, Protectimmun, and Novartis.

AT 2015 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

EXPECT: Omalizumab pregnancy safety data called ‘reassuring’

HOUSTON – Babies born to mothers who took omalizumab just before or during pregnancy exhibited birth defects that are in line with the general population, according to data from the EXPECT registry.

EXPECT (the Xolair Pregnancy Registry) is an ongoing, prospective observational study of pregnant women who received at least 1 dose of omalizumab within 2 months of conception or during their pregnancies.

Dr. Jennifer Namazy of the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif., presented data from women enrolled between September 2006 and November 2013 at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. The registry aims to enroll 250 women.

Dr. Namazy reported on 186 of the 207 expectant mothers for whom outcomes are recorded. Asthma severity was available for 164. Most (105 or 64%) had severe asthma, while 55 (34%) had moderate asthma, and 4 (2.4%) had mild disease. Each received omalizumab during the first trimester of pregnancy.

A total of 178 births were recorded, 174 of which were live. Of the 170 singletons, 24 (14%) were born at less than 37 weeks’ gestation and of those 3 (13%) were considered small for gestational age (weight less than 10th percentile for gestational age).

Of 140 single-born infants who were carried to full term and also had relevant weight data, 4 (3%) had low birth weight (less than 2.5 kg) and 16 (11%) were considered small for gestational age. Overall, 27 (15%) infants had confirmed congenital anomalies and 11 (6.2%) had a major birth defect.

“This is all very reassuring data,” Dr. Namazy said in an interview. “In terms of the outcomes – major defects and conditional defects – these results are not too unusual, [compared with] the general population. But when we’re looking at infant outcomes, it’s not too different from the severe asthma population.”

She noted, however, that “it’s hard to make large-scale conclusions from this sample size. When you’re talking about congenital malformations, they’re so rare and uncommon that you need a very large population in order to reach any kind of conclusion. But looking at these [data], we’re reassured because there isn’t any consistent information that’s disconcerting; it’s all over the spectrum, and so there’s no significant increase in the rate of birth rate defects that we’re seeing.”

Omalizumab is marketed by Genentech as Xolair. The EXPECT study is funded by Genentech and Novartis Pharma AG. Dr. Namazy is affiliated with Genentech.

HOUSTON – Babies born to mothers who took omalizumab just before or during pregnancy exhibited birth defects that are in line with the general population, according to data from the EXPECT registry.

EXPECT (the Xolair Pregnancy Registry) is an ongoing, prospective observational study of pregnant women who received at least 1 dose of omalizumab within 2 months of conception or during their pregnancies.

Dr. Jennifer Namazy of the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif., presented data from women enrolled between September 2006 and November 2013 at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. The registry aims to enroll 250 women.

Dr. Namazy reported on 186 of the 207 expectant mothers for whom outcomes are recorded. Asthma severity was available for 164. Most (105 or 64%) had severe asthma, while 55 (34%) had moderate asthma, and 4 (2.4%) had mild disease. Each received omalizumab during the first trimester of pregnancy.

A total of 178 births were recorded, 174 of which were live. Of the 170 singletons, 24 (14%) were born at less than 37 weeks’ gestation and of those 3 (13%) were considered small for gestational age (weight less than 10th percentile for gestational age).

Of 140 single-born infants who were carried to full term and also had relevant weight data, 4 (3%) had low birth weight (less than 2.5 kg) and 16 (11%) were considered small for gestational age. Overall, 27 (15%) infants had confirmed congenital anomalies and 11 (6.2%) had a major birth defect.

“This is all very reassuring data,” Dr. Namazy said in an interview. “In terms of the outcomes – major defects and conditional defects – these results are not too unusual, [compared with] the general population. But when we’re looking at infant outcomes, it’s not too different from the severe asthma population.”

She noted, however, that “it’s hard to make large-scale conclusions from this sample size. When you’re talking about congenital malformations, they’re so rare and uncommon that you need a very large population in order to reach any kind of conclusion. But looking at these [data], we’re reassured because there isn’t any consistent information that’s disconcerting; it’s all over the spectrum, and so there’s no significant increase in the rate of birth rate defects that we’re seeing.”

Omalizumab is marketed by Genentech as Xolair. The EXPECT study is funded by Genentech and Novartis Pharma AG. Dr. Namazy is affiliated with Genentech.

HOUSTON – Babies born to mothers who took omalizumab just before or during pregnancy exhibited birth defects that are in line with the general population, according to data from the EXPECT registry.

EXPECT (the Xolair Pregnancy Registry) is an ongoing, prospective observational study of pregnant women who received at least 1 dose of omalizumab within 2 months of conception or during their pregnancies.

Dr. Jennifer Namazy of the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif., presented data from women enrolled between September 2006 and November 2013 at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. The registry aims to enroll 250 women.

Dr. Namazy reported on 186 of the 207 expectant mothers for whom outcomes are recorded. Asthma severity was available for 164. Most (105 or 64%) had severe asthma, while 55 (34%) had moderate asthma, and 4 (2.4%) had mild disease. Each received omalizumab during the first trimester of pregnancy.

A total of 178 births were recorded, 174 of which were live. Of the 170 singletons, 24 (14%) were born at less than 37 weeks’ gestation and of those 3 (13%) were considered small for gestational age (weight less than 10th percentile for gestational age).

Of 140 single-born infants who were carried to full term and also had relevant weight data, 4 (3%) had low birth weight (less than 2.5 kg) and 16 (11%) were considered small for gestational age. Overall, 27 (15%) infants had confirmed congenital anomalies and 11 (6.2%) had a major birth defect.

“This is all very reassuring data,” Dr. Namazy said in an interview. “In terms of the outcomes – major defects and conditional defects – these results are not too unusual, [compared with] the general population. But when we’re looking at infant outcomes, it’s not too different from the severe asthma population.”

She noted, however, that “it’s hard to make large-scale conclusions from this sample size. When you’re talking about congenital malformations, they’re so rare and uncommon that you need a very large population in order to reach any kind of conclusion. But looking at these [data], we’re reassured because there isn’t any consistent information that’s disconcerting; it’s all over the spectrum, and so there’s no significant increase in the rate of birth rate defects that we’re seeing.”

Omalizumab is marketed by Genentech as Xolair. The EXPECT study is funded by Genentech and Novartis Pharma AG. Dr. Namazy is affiliated with Genentech.

AT 2015 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Omalizumab does not appear to increase the risk of birth defects or adverse outcomes in pregnant women and their babies.

Major finding: Of 140 singleton infants carried to full term and for whom relevant weight data was available, 4 (2.9%) had low birth weight and 16 (11.4%) were considered small for gestational age, 27 (15.2%) had congenital anomalies, and 11 (6.2%) had a major birth defect.

Data source: EXPECT trial – an ongoing observational study of 207 prospectively enrolled women.

Disclosures: EXPECT is funded by Genentech and Novartis Pharma AG. Dr. Namazy is affiliated with Genentech.