User login

American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry (AAGP)

ECT electrode placement matters most in elderly

ORLANDO – Right unilateral electroconvulsive therapy at six times the seizure threshold is markedly more effective in severely depressed patients aged 60 and older than in those who are younger, according to a multicenter randomized trial.

Bitemporal and right unilateral (RUL) ECT proved similarly effective in older patients, and both were better than bifrontal ECT in the elderly.

"One implication of our study is that in an older patient who didn’t want bitemporal ECT or whose family didn’t, then I would choose right unilateral because it’s just as good," Dr. Sohag N. Sanghani said at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

He presented a secondary analysis of a double-blind multicenter trial in which 230 patients with a major unipolar or bipolar depressive episode and a mean baseline score of 35 on the 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression were randomized to one of the three ECT electrode placements. Remission rates and adverse cognitive effects were similar in all three groups, as previously shown in the primary analysis (Br. J. Psychiatry 2010;196:226-34).

The secondary analysis was aimed at learning if age had a differential effect upon the effectiveness of the three electrode placements. It did: RUL had a 70.4% remission rate in patients aged 60 and older, compared with 46% in the younger group. And bifrontal ECT had a 50% remission rate in older patients versus a 64.4% rate in those younger than age 60, reported Dr. Sanghani, a geriatric psychiatry fellow at Zucker Hillside Hospital in Glen Oaks, N.Y.

In contrast, the 75% remission rate with bitemporal ECT in the older group was not significantly different from the 58.3% rate in younger patients, he added.

Dr. Sanghani’s coinvestigator Dr. Georgios Petrides offered two possible explanations for the differential efficacy with age. One is that because the brain shrinks with advancing age, bifrontal electrode placement in the elderly might result in weak contact and loss of much of the stimulus, while ECT delivered via RUL placement captures much more of the brain.

"On the other hand, we always get a better response with ECT in the elderly than with younger people. So maybe depression in the elderly is a different animal than in younger people," suggested Dr. Petrides, a psychiatrist at Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine, Glen Oaks.

Their study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. They reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

ORLANDO – Right unilateral electroconvulsive therapy at six times the seizure threshold is markedly more effective in severely depressed patients aged 60 and older than in those who are younger, according to a multicenter randomized trial.

Bitemporal and right unilateral (RUL) ECT proved similarly effective in older patients, and both were better than bifrontal ECT in the elderly.

"One implication of our study is that in an older patient who didn’t want bitemporal ECT or whose family didn’t, then I would choose right unilateral because it’s just as good," Dr. Sohag N. Sanghani said at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

He presented a secondary analysis of a double-blind multicenter trial in which 230 patients with a major unipolar or bipolar depressive episode and a mean baseline score of 35 on the 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression were randomized to one of the three ECT electrode placements. Remission rates and adverse cognitive effects were similar in all three groups, as previously shown in the primary analysis (Br. J. Psychiatry 2010;196:226-34).

The secondary analysis was aimed at learning if age had a differential effect upon the effectiveness of the three electrode placements. It did: RUL had a 70.4% remission rate in patients aged 60 and older, compared with 46% in the younger group. And bifrontal ECT had a 50% remission rate in older patients versus a 64.4% rate in those younger than age 60, reported Dr. Sanghani, a geriatric psychiatry fellow at Zucker Hillside Hospital in Glen Oaks, N.Y.

In contrast, the 75% remission rate with bitemporal ECT in the older group was not significantly different from the 58.3% rate in younger patients, he added.

Dr. Sanghani’s coinvestigator Dr. Georgios Petrides offered two possible explanations for the differential efficacy with age. One is that because the brain shrinks with advancing age, bifrontal electrode placement in the elderly might result in weak contact and loss of much of the stimulus, while ECT delivered via RUL placement captures much more of the brain.

"On the other hand, we always get a better response with ECT in the elderly than with younger people. So maybe depression in the elderly is a different animal than in younger people," suggested Dr. Petrides, a psychiatrist at Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine, Glen Oaks.

Their study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. They reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

ORLANDO – Right unilateral electroconvulsive therapy at six times the seizure threshold is markedly more effective in severely depressed patients aged 60 and older than in those who are younger, according to a multicenter randomized trial.

Bitemporal and right unilateral (RUL) ECT proved similarly effective in older patients, and both were better than bifrontal ECT in the elderly.

"One implication of our study is that in an older patient who didn’t want bitemporal ECT or whose family didn’t, then I would choose right unilateral because it’s just as good," Dr. Sohag N. Sanghani said at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

He presented a secondary analysis of a double-blind multicenter trial in which 230 patients with a major unipolar or bipolar depressive episode and a mean baseline score of 35 on the 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression were randomized to one of the three ECT electrode placements. Remission rates and adverse cognitive effects were similar in all three groups, as previously shown in the primary analysis (Br. J. Psychiatry 2010;196:226-34).

The secondary analysis was aimed at learning if age had a differential effect upon the effectiveness of the three electrode placements. It did: RUL had a 70.4% remission rate in patients aged 60 and older, compared with 46% in the younger group. And bifrontal ECT had a 50% remission rate in older patients versus a 64.4% rate in those younger than age 60, reported Dr. Sanghani, a geriatric psychiatry fellow at Zucker Hillside Hospital in Glen Oaks, N.Y.

In contrast, the 75% remission rate with bitemporal ECT in the older group was not significantly different from the 58.3% rate in younger patients, he added.

Dr. Sanghani’s coinvestigator Dr. Georgios Petrides offered two possible explanations for the differential efficacy with age. One is that because the brain shrinks with advancing age, bifrontal electrode placement in the elderly might result in weak contact and loss of much of the stimulus, while ECT delivered via RUL placement captures much more of the brain.

"On the other hand, we always get a better response with ECT in the elderly than with younger people. So maybe depression in the elderly is a different animal than in younger people," suggested Dr. Petrides, a psychiatrist at Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine, Glen Oaks.

Their study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. They reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

AT THE AAGP ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: Right unilateral ECT provided a 70.4% remission rate in severely depressed patients aged 60 or older, compared with a 46% rate in those under age 60.

Data source: A secondary analysis of a multicenter, randomized double-blind study in which 230 severely depressed patients received right unilateral, bitemporal, or bifrontal ECT.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. The presenters reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

Simple smell test may predict donepezil response

ORLANDO – Predicting whether add-on donepezil will improve residual cognitive deficits in an elderly patient on adequate antidepressant therapy may be as plain as the nose on the patient’s face.

Compared with the olfaction-intact patient, those with baseline deficits in sense of smell on a simple scratch-and-sniff test had significantly more improvements in episodic memory after 12 weeks of donepezil (Aricept) in a placebo-controlled, double-blind randomized pilot study, Dr. Gregory H. Pelton reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

"One’s ability to smell may be a predictor of Alzheimer’s disease pathology that will respond to acetylcholinesterase inhibitor therapy. That’s the logic here," explained Dr. Pelton, a psychiatrist at Columbia University, New York.

Patients with late-life depression and cognitive impairment are known to be at even greater risk for progression to dementia than are patients with mild cognitive impairment. Donepezil is approved for improving cognition in patients with Alzheimer’s disease but not in those with mild cognitive impairment, where the evidence of benefit has been equivocal. Since the distinctive neurobiologic abnormalities of Alzheimer’s disease are known to be present for many years before the disease is diagnosed, Dr. Pelton and his coworkers reasoned that a low score on a test of olfactory identification might be a biomarker for donepezil responsiveness in these patients.

"The olfactory system is a very old evolutionary system. Since it projects directly to the entorhinal cortex, which then goes to the hippocampus, it’s actually directly involved in memory. Everybody has these flashes of old memories that arise with olfactory stimuli," Dr. Pelton said in an interview. The nose is an expressway to memory.

Deficits in olfactory identification as assessed by the commercially available, 40-item, multiple-choice, scratch-and-sniff University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) have been shown to be associated with an increased rate of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease (Am. J. Psychiatry 2000;157:1399-405).

The pilot study included 18 patients with late-life depression and cognitive impairment with a Mini Mental State Exam score above 20 out of a possible 30. All participants received 8 weeks of open-label antidepressant therapy followed by 12 weeks of donepezil or placebo in the trial. The primary outcome was the change in episodic verbal memory between weeks 8 and 20 as reflected in the Selective Reminding Test immediate total recall score.

Five patients had a low baseline UPSIT score, meaning they correctly identified fewer than 30 of the 40 scratch-and-sniff items. Patients with a low UPSIT score who were assigned to donepezil showed a mean 10.4-point improvement on the Selective Reminding Test, while those with an UPSIT score of 30 or more showed a 2.7-point improvement in response to the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor.

Based upon these encouraging pilot study results, Dr. Pelton is now conducting a larger, confirmatory randomized trial funded by the National Institutes of Health.

"If the finding of olfactory deficits predicting acetylcholinesterase inhibitor response is replicated in larger samples, utilizing this simple, reliable, and inexpensive approach may improve the selection of patients with late-life depression and cognitive impairment, and possibly also those with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease, who are likely to respond to acetylcholinesterase inhibitor therapy," he noted.

The study was funded by the Alzheimer’s Association, federal research grants, and Pfizer. Dr. Pelton is a consultant to the company.

ORLANDO – Predicting whether add-on donepezil will improve residual cognitive deficits in an elderly patient on adequate antidepressant therapy may be as plain as the nose on the patient’s face.

Compared with the olfaction-intact patient, those with baseline deficits in sense of smell on a simple scratch-and-sniff test had significantly more improvements in episodic memory after 12 weeks of donepezil (Aricept) in a placebo-controlled, double-blind randomized pilot study, Dr. Gregory H. Pelton reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

"One’s ability to smell may be a predictor of Alzheimer’s disease pathology that will respond to acetylcholinesterase inhibitor therapy. That’s the logic here," explained Dr. Pelton, a psychiatrist at Columbia University, New York.

Patients with late-life depression and cognitive impairment are known to be at even greater risk for progression to dementia than are patients with mild cognitive impairment. Donepezil is approved for improving cognition in patients with Alzheimer’s disease but not in those with mild cognitive impairment, where the evidence of benefit has been equivocal. Since the distinctive neurobiologic abnormalities of Alzheimer’s disease are known to be present for many years before the disease is diagnosed, Dr. Pelton and his coworkers reasoned that a low score on a test of olfactory identification might be a biomarker for donepezil responsiveness in these patients.

"The olfactory system is a very old evolutionary system. Since it projects directly to the entorhinal cortex, which then goes to the hippocampus, it’s actually directly involved in memory. Everybody has these flashes of old memories that arise with olfactory stimuli," Dr. Pelton said in an interview. The nose is an expressway to memory.

Deficits in olfactory identification as assessed by the commercially available, 40-item, multiple-choice, scratch-and-sniff University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) have been shown to be associated with an increased rate of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease (Am. J. Psychiatry 2000;157:1399-405).

The pilot study included 18 patients with late-life depression and cognitive impairment with a Mini Mental State Exam score above 20 out of a possible 30. All participants received 8 weeks of open-label antidepressant therapy followed by 12 weeks of donepezil or placebo in the trial. The primary outcome was the change in episodic verbal memory between weeks 8 and 20 as reflected in the Selective Reminding Test immediate total recall score.

Five patients had a low baseline UPSIT score, meaning they correctly identified fewer than 30 of the 40 scratch-and-sniff items. Patients with a low UPSIT score who were assigned to donepezil showed a mean 10.4-point improvement on the Selective Reminding Test, while those with an UPSIT score of 30 or more showed a 2.7-point improvement in response to the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor.

Based upon these encouraging pilot study results, Dr. Pelton is now conducting a larger, confirmatory randomized trial funded by the National Institutes of Health.

"If the finding of olfactory deficits predicting acetylcholinesterase inhibitor response is replicated in larger samples, utilizing this simple, reliable, and inexpensive approach may improve the selection of patients with late-life depression and cognitive impairment, and possibly also those with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease, who are likely to respond to acetylcholinesterase inhibitor therapy," he noted.

The study was funded by the Alzheimer’s Association, federal research grants, and Pfizer. Dr. Pelton is a consultant to the company.

ORLANDO – Predicting whether add-on donepezil will improve residual cognitive deficits in an elderly patient on adequate antidepressant therapy may be as plain as the nose on the patient’s face.

Compared with the olfaction-intact patient, those with baseline deficits in sense of smell on a simple scratch-and-sniff test had significantly more improvements in episodic memory after 12 weeks of donepezil (Aricept) in a placebo-controlled, double-blind randomized pilot study, Dr. Gregory H. Pelton reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

"One’s ability to smell may be a predictor of Alzheimer’s disease pathology that will respond to acetylcholinesterase inhibitor therapy. That’s the logic here," explained Dr. Pelton, a psychiatrist at Columbia University, New York.

Patients with late-life depression and cognitive impairment are known to be at even greater risk for progression to dementia than are patients with mild cognitive impairment. Donepezil is approved for improving cognition in patients with Alzheimer’s disease but not in those with mild cognitive impairment, where the evidence of benefit has been equivocal. Since the distinctive neurobiologic abnormalities of Alzheimer’s disease are known to be present for many years before the disease is diagnosed, Dr. Pelton and his coworkers reasoned that a low score on a test of olfactory identification might be a biomarker for donepezil responsiveness in these patients.

"The olfactory system is a very old evolutionary system. Since it projects directly to the entorhinal cortex, which then goes to the hippocampus, it’s actually directly involved in memory. Everybody has these flashes of old memories that arise with olfactory stimuli," Dr. Pelton said in an interview. The nose is an expressway to memory.

Deficits in olfactory identification as assessed by the commercially available, 40-item, multiple-choice, scratch-and-sniff University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) have been shown to be associated with an increased rate of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease (Am. J. Psychiatry 2000;157:1399-405).

The pilot study included 18 patients with late-life depression and cognitive impairment with a Mini Mental State Exam score above 20 out of a possible 30. All participants received 8 weeks of open-label antidepressant therapy followed by 12 weeks of donepezil or placebo in the trial. The primary outcome was the change in episodic verbal memory between weeks 8 and 20 as reflected in the Selective Reminding Test immediate total recall score.

Five patients had a low baseline UPSIT score, meaning they correctly identified fewer than 30 of the 40 scratch-and-sniff items. Patients with a low UPSIT score who were assigned to donepezil showed a mean 10.4-point improvement on the Selective Reminding Test, while those with an UPSIT score of 30 or more showed a 2.7-point improvement in response to the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor.

Based upon these encouraging pilot study results, Dr. Pelton is now conducting a larger, confirmatory randomized trial funded by the National Institutes of Health.

"If the finding of olfactory deficits predicting acetylcholinesterase inhibitor response is replicated in larger samples, utilizing this simple, reliable, and inexpensive approach may improve the selection of patients with late-life depression and cognitive impairment, and possibly also those with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease, who are likely to respond to acetylcholinesterase inhibitor therapy," he noted.

The study was funded by the Alzheimer’s Association, federal research grants, and Pfizer. Dr. Pelton is a consultant to the company.

AT THE AAGP ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: Patients with a low UPSIT score who were assigned to donepezil showed a mean 10.4-point improvement on the Selective Reminding Test, while those with an UPSIT score of 30 or more showed a 2.7-point improvement in response to the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor.

Data source: This was a pilot study involving 18 patients with late-life depression and cognitive impairment who received 8 weeks of antidepressant therapy, and then were randomized double-blind to 12 weeks of donepezil or placebo.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Alzheimer’s Association, federal research grants, and Pfizer. Dr. Pelton is a consultant to the company.

Time for an evidence-informed systematic approach to the pharmacotherapy of geriatric depression

Psychiatrists are quick to point out that primary care physicians do a poor job when treating depression. However, most psychiatrists are not that good at treating depression themselves.

I believe that truly treatment-resistant depression in elderly patients accounts for less than 10% of the patients we treat. (Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2002;59:729-35) But if you look at treatment as usual, we help only 30%-40% of the patients we see. I make the claim – and I’m ready to say it publicly – that we should be able to do about twice as well as that. Not only do we not help as many people as we should, but we hurt quite a few.

The reason for the low success rates and significant collateral damage in treating geriatric depression is that most psychiatrists are unwilling to adopting an evidence-informed stepped-care approach. Most practitioners were drawn to psychiatry because they are kind, empathic people who enjoy listening to their patients. They try to match their first-line antidepressant to the patient’s individual clinical characteristics or circumstances. As a result, they do not gain extensive clinical experience with any given medication, they don’t exude confidence in its use, they make ill-timed changes in treatment, and they are susceptible to the latest "fad du jour."

I use a treatment algorithm. That’s the one I would use for my 85-year-old mother if she got depressed, and if it’s good enough for my mother, it’s good enough for my patients. I’m going to use this treatment algorithm in patients I’ve not yet met and I’ve not yet talked to. By not trying to match a specific treatment to an individual patient, I believe that I will be able to get 60%-70% of those people better. And if they don’t give up and stay in our clinic for a year through up to three or four treatment trials, if need be, we’re going to help about 90% of those older depressed patients.

In the landmark PROSPECT study (Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial), my coinvestigators and I developed and used one such treatment algorithm (Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2001;16:585-92). This particular algorithm resulted in faster improvement and a significantly higher 24-month remission rate than did usual care in randomized depressed patients (Am. J. Psychiatry 2009;166:882-90), but there are other stepped-care algorithms of proven benefit (J. Clin. Psych. 2005;65:1634-41). Each step utilizes a medication with a different mechanism of action. In a meta-analysis of studies on treatment-resistant depression, sequential treatment – that is, a stepped-care approach – was what worked best, with an 88% response rate (Am. J. Psychiatry 2011;168:681-8).

Everyone in medicine is aware that poor patient adherence to prescribed medications is a big problem. That’s particularly true in late-life depression. The secret to high treatment response rates in geriatric depression is to convince the patient to fill the prescription, take the drug as prescribed, and stay on it despite initial side effects or lack of efficacy. A psychiatrist who follows a treatment algorithm is able to be more convincing in this regard because of more extensive experience with a given drug.

A negative randomized clinical trial of citalopram for the treatment of geriatric depression is a good illustration of a dirty little secret about psychopharmacology: Where a patient gets treated – that is, the way psychiatrists at that site use the drug – matters more than the drug itself does. In this 15-site clinical trial, the response rates to citalopram ranged by site from a low of 18% to 82%, while the response to placebo ranged from 16% to 80% (Am. J. Psychiatry 2004;161:2050-9).

Dr. Benoit H. Mulsant is professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto and physician in chief at the Center for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto. This editorial is adapted from his presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. Dr. Mulsant reported that his research has been supported predominantly by the National Institute of Mental Health (with medications for NIMH-funded clinical trials provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, or Pfizer), and he declared having no other financial conflicts.

Psychiatrists are quick to point out that primary care physicians do a poor job when treating depression. However, most psychiatrists are not that good at treating depression themselves.

I believe that truly treatment-resistant depression in elderly patients accounts for less than 10% of the patients we treat. (Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2002;59:729-35) But if you look at treatment as usual, we help only 30%-40% of the patients we see. I make the claim – and I’m ready to say it publicly – that we should be able to do about twice as well as that. Not only do we not help as many people as we should, but we hurt quite a few.

The reason for the low success rates and significant collateral damage in treating geriatric depression is that most psychiatrists are unwilling to adopting an evidence-informed stepped-care approach. Most practitioners were drawn to psychiatry because they are kind, empathic people who enjoy listening to their patients. They try to match their first-line antidepressant to the patient’s individual clinical characteristics or circumstances. As a result, they do not gain extensive clinical experience with any given medication, they don’t exude confidence in its use, they make ill-timed changes in treatment, and they are susceptible to the latest "fad du jour."

I use a treatment algorithm. That’s the one I would use for my 85-year-old mother if she got depressed, and if it’s good enough for my mother, it’s good enough for my patients. I’m going to use this treatment algorithm in patients I’ve not yet met and I’ve not yet talked to. By not trying to match a specific treatment to an individual patient, I believe that I will be able to get 60%-70% of those people better. And if they don’t give up and stay in our clinic for a year through up to three or four treatment trials, if need be, we’re going to help about 90% of those older depressed patients.

In the landmark PROSPECT study (Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial), my coinvestigators and I developed and used one such treatment algorithm (Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2001;16:585-92). This particular algorithm resulted in faster improvement and a significantly higher 24-month remission rate than did usual care in randomized depressed patients (Am. J. Psychiatry 2009;166:882-90), but there are other stepped-care algorithms of proven benefit (J. Clin. Psych. 2005;65:1634-41). Each step utilizes a medication with a different mechanism of action. In a meta-analysis of studies on treatment-resistant depression, sequential treatment – that is, a stepped-care approach – was what worked best, with an 88% response rate (Am. J. Psychiatry 2011;168:681-8).

Everyone in medicine is aware that poor patient adherence to prescribed medications is a big problem. That’s particularly true in late-life depression. The secret to high treatment response rates in geriatric depression is to convince the patient to fill the prescription, take the drug as prescribed, and stay on it despite initial side effects or lack of efficacy. A psychiatrist who follows a treatment algorithm is able to be more convincing in this regard because of more extensive experience with a given drug.

A negative randomized clinical trial of citalopram for the treatment of geriatric depression is a good illustration of a dirty little secret about psychopharmacology: Where a patient gets treated – that is, the way psychiatrists at that site use the drug – matters more than the drug itself does. In this 15-site clinical trial, the response rates to citalopram ranged by site from a low of 18% to 82%, while the response to placebo ranged from 16% to 80% (Am. J. Psychiatry 2004;161:2050-9).

Dr. Benoit H. Mulsant is professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto and physician in chief at the Center for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto. This editorial is adapted from his presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. Dr. Mulsant reported that his research has been supported predominantly by the National Institute of Mental Health (with medications for NIMH-funded clinical trials provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, or Pfizer), and he declared having no other financial conflicts.

Psychiatrists are quick to point out that primary care physicians do a poor job when treating depression. However, most psychiatrists are not that good at treating depression themselves.

I believe that truly treatment-resistant depression in elderly patients accounts for less than 10% of the patients we treat. (Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2002;59:729-35) But if you look at treatment as usual, we help only 30%-40% of the patients we see. I make the claim – and I’m ready to say it publicly – that we should be able to do about twice as well as that. Not only do we not help as many people as we should, but we hurt quite a few.

The reason for the low success rates and significant collateral damage in treating geriatric depression is that most psychiatrists are unwilling to adopting an evidence-informed stepped-care approach. Most practitioners were drawn to psychiatry because they are kind, empathic people who enjoy listening to their patients. They try to match their first-line antidepressant to the patient’s individual clinical characteristics or circumstances. As a result, they do not gain extensive clinical experience with any given medication, they don’t exude confidence in its use, they make ill-timed changes in treatment, and they are susceptible to the latest "fad du jour."

I use a treatment algorithm. That’s the one I would use for my 85-year-old mother if she got depressed, and if it’s good enough for my mother, it’s good enough for my patients. I’m going to use this treatment algorithm in patients I’ve not yet met and I’ve not yet talked to. By not trying to match a specific treatment to an individual patient, I believe that I will be able to get 60%-70% of those people better. And if they don’t give up and stay in our clinic for a year through up to three or four treatment trials, if need be, we’re going to help about 90% of those older depressed patients.

In the landmark PROSPECT study (Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial), my coinvestigators and I developed and used one such treatment algorithm (Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2001;16:585-92). This particular algorithm resulted in faster improvement and a significantly higher 24-month remission rate than did usual care in randomized depressed patients (Am. J. Psychiatry 2009;166:882-90), but there are other stepped-care algorithms of proven benefit (J. Clin. Psych. 2005;65:1634-41). Each step utilizes a medication with a different mechanism of action. In a meta-analysis of studies on treatment-resistant depression, sequential treatment – that is, a stepped-care approach – was what worked best, with an 88% response rate (Am. J. Psychiatry 2011;168:681-8).

Everyone in medicine is aware that poor patient adherence to prescribed medications is a big problem. That’s particularly true in late-life depression. The secret to high treatment response rates in geriatric depression is to convince the patient to fill the prescription, take the drug as prescribed, and stay on it despite initial side effects or lack of efficacy. A psychiatrist who follows a treatment algorithm is able to be more convincing in this regard because of more extensive experience with a given drug.

A negative randomized clinical trial of citalopram for the treatment of geriatric depression is a good illustration of a dirty little secret about psychopharmacology: Where a patient gets treated – that is, the way psychiatrists at that site use the drug – matters more than the drug itself does. In this 15-site clinical trial, the response rates to citalopram ranged by site from a low of 18% to 82%, while the response to placebo ranged from 16% to 80% (Am. J. Psychiatry 2004;161:2050-9).

Dr. Benoit H. Mulsant is professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto and physician in chief at the Center for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto. This editorial is adapted from his presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. Dr. Mulsant reported that his research has been supported predominantly by the National Institute of Mental Health (with medications for NIMH-funded clinical trials provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, or Pfizer), and he declared having no other financial conflicts.

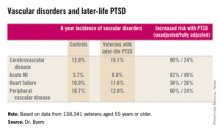

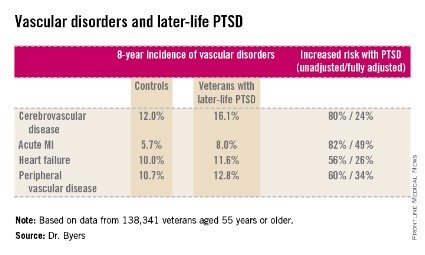

Later-life PTSD boosts vascular risk

ORLANDO – Military veterans aged 55 years or older with current posttraumatic stress disorder are at significantly higher risk of developing new-onset vascular disease than those without PTSD, according to a very large national longitudinal study.

"This study suggests the need for greater monitoring and treatment of PTSD in older veterans to assist in the prevention of vascular disorders over the long term," Amy L. Byers, Ph.D., asserted at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

She reported on 138,341 veterans aged 55 years or older, all of whom were free of known vascular disease at baseline. During 8 years of follow-up, the subjects with PTSD had significantly higher rates of incident cerebrovascular disease, acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and peripheral vascular disease than those without a current diagnosis of PTSD.

This remained the case even after controlling for numerous potential confounders in multivariate analysis, including demographics and comorbid diabetes, hypertension, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal disease, traumatic brain injury, dementia, substance use disorders, and psychiatric diagnoses. The fully adjusted increased risk of each of the forms of vascular disease under study still remained significant at the P less than .001 level, noted Dr. Byers, an epidemiologist in the psychiatry department at the University of California, San Francisco.

These findings are neither generalizable to veterans under age 55 with PTSD nor generalizable to civilians, she said. But a separate, newly published study in which Dr. Byers was the lead author did show that PTSD in the general population with onset prior to age 55 and persistence beyond age 55 is a powerful independent predictor of global disability.

Dr. Byers’ study of older veterans was funded by the Department of Defense. She reported having no financial conflicts.

ORLANDO – Military veterans aged 55 years or older with current posttraumatic stress disorder are at significantly higher risk of developing new-onset vascular disease than those without PTSD, according to a very large national longitudinal study.

"This study suggests the need for greater monitoring and treatment of PTSD in older veterans to assist in the prevention of vascular disorders over the long term," Amy L. Byers, Ph.D., asserted at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

She reported on 138,341 veterans aged 55 years or older, all of whom were free of known vascular disease at baseline. During 8 years of follow-up, the subjects with PTSD had significantly higher rates of incident cerebrovascular disease, acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and peripheral vascular disease than those without a current diagnosis of PTSD.

This remained the case even after controlling for numerous potential confounders in multivariate analysis, including demographics and comorbid diabetes, hypertension, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal disease, traumatic brain injury, dementia, substance use disorders, and psychiatric diagnoses. The fully adjusted increased risk of each of the forms of vascular disease under study still remained significant at the P less than .001 level, noted Dr. Byers, an epidemiologist in the psychiatry department at the University of California, San Francisco.

These findings are neither generalizable to veterans under age 55 with PTSD nor generalizable to civilians, she said. But a separate, newly published study in which Dr. Byers was the lead author did show that PTSD in the general population with onset prior to age 55 and persistence beyond age 55 is a powerful independent predictor of global disability.

Dr. Byers’ study of older veterans was funded by the Department of Defense. She reported having no financial conflicts.

ORLANDO – Military veterans aged 55 years or older with current posttraumatic stress disorder are at significantly higher risk of developing new-onset vascular disease than those without PTSD, according to a very large national longitudinal study.

"This study suggests the need for greater monitoring and treatment of PTSD in older veterans to assist in the prevention of vascular disorders over the long term," Amy L. Byers, Ph.D., asserted at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

She reported on 138,341 veterans aged 55 years or older, all of whom were free of known vascular disease at baseline. During 8 years of follow-up, the subjects with PTSD had significantly higher rates of incident cerebrovascular disease, acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and peripheral vascular disease than those without a current diagnosis of PTSD.

This remained the case even after controlling for numerous potential confounders in multivariate analysis, including demographics and comorbid diabetes, hypertension, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal disease, traumatic brain injury, dementia, substance use disorders, and psychiatric diagnoses. The fully adjusted increased risk of each of the forms of vascular disease under study still remained significant at the P less than .001 level, noted Dr. Byers, an epidemiologist in the psychiatry department at the University of California, San Francisco.

These findings are neither generalizable to veterans under age 55 with PTSD nor generalizable to civilians, she said. But a separate, newly published study in which Dr. Byers was the lead author did show that PTSD in the general population with onset prior to age 55 and persistence beyond age 55 is a powerful independent predictor of global disability.

Dr. Byers’ study of older veterans was funded by the Department of Defense. She reported having no financial conflicts.

AT THE AAGP ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: Military veterans with late-life posttraumatic stress disorder were 80% more likely to develop new-onset cerebrovascular disease during 8 years of follow-up than were those without PTSD. They were also 82% more likely to have a first acute myocardial infarction, 56% more likely to develop heart failure, and 60% more likely to be diagnosed with peripheral vascular disease.

Data source: This was a longitudinal observational study in 138,341 veterans aged 55 years or older who were free of known vascular disease at baseline and were followed for 8 years.

Disclosures: Dr. Byers’ study of older veterans was funded by the Department of Defense. She reported having no financial conflicts.

ECT quells dementia-associated agitation

ORLANDO – Electroconvulsive therapy was safe and effective for treatment of refractory agitation in patients with dementia, including those with multiple medical comorbidities, in the largest case series reported to date.

"This was true at least in the short term. Long term, there are no data," Dr. Yilang Tang noted at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

He presented a retrospective chart review of the 38 patients with dementia who received ECT for agitation at Emory University’s Wesley Woods Geriatric Hospital in Atlanta during 2012.

On admission, patients were on an average of six psychotropic medications, including two or more antipsychotic agents in half of cases. The subjects averaged 6.2 Axis III diagnoses. Patients received a mean of 10.2 and median of 6 ECT treatments. The ECT was performed initially with right unilateral electrode placement in 35 of 38 patients; however, 6 patients were switched to bifrontal placement after four to six sessions because of poor response.

The mean baseline total Pittsburgh Agitation Scale score was 9.2. At discharge, after an average length of stay of 26 days, all patients demonstrated a significant reduction in their agitation score, with a median 8-point drop from baseline. Two patients had transient increases in their agitation score, from 7 points to 11 in one case and from 3 points to 7 in the other, but they improved with maintenance ECT after their acute course of therapy. In addition, patients went from an average of six psychotropic medications at admission to five at discharge, according to Dr. Tang, a psychiatric resident at Emory University in Atlanta.

Most patients were discharged after four to six ECT sessions, although seven patients received more than 12 treatments, mostly delivered as outpatient maintenance therapy.

One patient experienced transient ECT-related delirium. Yet no major treatment-related medical complications occurred, even though 7 patients had coronary artery disease, 24 were hypertensive, 3 had a history of stroke, and 3 patients had heart failure.

Only 2 of 38 patients were readmitted within 1 year after discharge, one of whom got another course of ECT. Although the possibility of readmission at other facilities can’t be ruled out, it seems unlikely that this occurred often, since patients’ surrogates were pleased with the post-ECT clinical improvement, Dr. Tang observed.

Agitation is one of the most distressing behavioral manifestations of dementia for patients, caregivers, and hospital staff. No medication has demonstrated effectiveness in treating this condition.

Subsequent to Dr. Tang’s presentation, two distinguished senior geriatric psychiatrists weighed in on the question of whether ECT has a legitimate role in treating agitation and other behavioral disturbances associated with dementia.

"It’s an unconventional use of the therapy. I would say it would be a fairly rare occurrence. It should not be something that is done commonly," asserted Dr. W. Vaughn McCall, professor of psychiatry and health behavior at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta.

"Remember, the FDA indication for ECT does not include that particular use, although like with medications, you have the right to use a device off label if you can justify it. I would say the key in justifying it is to make sure you’re treating the patient’s distress and [you’re not using it] for the benefit of the nursing home staff. If you’re going to use ECT for a patient with dementia-associated agitation, it needs to be crystal clear that this is being done for the benefit of the patient, that the patient is in distress, and if you can also make the case that there is a concurrent depression along with the major neurocognitive disorder, then possibly you could justify using ECT if all other options have been exhausted," he added.

His fellow panelist Dr. George T. Grossberg took a more expansive view of ECT in patients with dementia.

"We do recommend ECT for patients with major neurocognitive disorders, either in instances where they have severe or treatment-resistant depression in the context of Alzheimer’s disease – where they tend to respond very well – or on rare occasions in treatment-resistant agitation. After we’ve tried everything else possible and they’re just really difficult to manage, I think a trial of ECT may be warranted. It has a calming, dampening effect on agitation and irritability," said Dr. Grossberg, professor of psychiatry, anatomy, neurobiology, and internal medicine at Saint Louis University.

"One thing it’s important to keep in mind is that if you have depression in the context of Alzheimer’s disease, and you decide to go with ECT because the depression is so severe or refractory, cognition will actually improve. When the depression starts to lift with the ECT, confusion and cognitive impairment will also improve. So I would keep ECT on the agenda," the geriatric psychiatrist added.

Dr. Tang reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Electroconvulsive therapy was safe and effective for treatment of refractory agitation in patients with dementia, including those with multiple medical comorbidities, in the largest case series reported to date.

"This was true at least in the short term. Long term, there are no data," Dr. Yilang Tang noted at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

He presented a retrospective chart review of the 38 patients with dementia who received ECT for agitation at Emory University’s Wesley Woods Geriatric Hospital in Atlanta during 2012.

On admission, patients were on an average of six psychotropic medications, including two or more antipsychotic agents in half of cases. The subjects averaged 6.2 Axis III diagnoses. Patients received a mean of 10.2 and median of 6 ECT treatments. The ECT was performed initially with right unilateral electrode placement in 35 of 38 patients; however, 6 patients were switched to bifrontal placement after four to six sessions because of poor response.

The mean baseline total Pittsburgh Agitation Scale score was 9.2. At discharge, after an average length of stay of 26 days, all patients demonstrated a significant reduction in their agitation score, with a median 8-point drop from baseline. Two patients had transient increases in their agitation score, from 7 points to 11 in one case and from 3 points to 7 in the other, but they improved with maintenance ECT after their acute course of therapy. In addition, patients went from an average of six psychotropic medications at admission to five at discharge, according to Dr. Tang, a psychiatric resident at Emory University in Atlanta.

Most patients were discharged after four to six ECT sessions, although seven patients received more than 12 treatments, mostly delivered as outpatient maintenance therapy.

One patient experienced transient ECT-related delirium. Yet no major treatment-related medical complications occurred, even though 7 patients had coronary artery disease, 24 were hypertensive, 3 had a history of stroke, and 3 patients had heart failure.

Only 2 of 38 patients were readmitted within 1 year after discharge, one of whom got another course of ECT. Although the possibility of readmission at other facilities can’t be ruled out, it seems unlikely that this occurred often, since patients’ surrogates were pleased with the post-ECT clinical improvement, Dr. Tang observed.

Agitation is one of the most distressing behavioral manifestations of dementia for patients, caregivers, and hospital staff. No medication has demonstrated effectiveness in treating this condition.

Subsequent to Dr. Tang’s presentation, two distinguished senior geriatric psychiatrists weighed in on the question of whether ECT has a legitimate role in treating agitation and other behavioral disturbances associated with dementia.

"It’s an unconventional use of the therapy. I would say it would be a fairly rare occurrence. It should not be something that is done commonly," asserted Dr. W. Vaughn McCall, professor of psychiatry and health behavior at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta.

"Remember, the FDA indication for ECT does not include that particular use, although like with medications, you have the right to use a device off label if you can justify it. I would say the key in justifying it is to make sure you’re treating the patient’s distress and [you’re not using it] for the benefit of the nursing home staff. If you’re going to use ECT for a patient with dementia-associated agitation, it needs to be crystal clear that this is being done for the benefit of the patient, that the patient is in distress, and if you can also make the case that there is a concurrent depression along with the major neurocognitive disorder, then possibly you could justify using ECT if all other options have been exhausted," he added.

His fellow panelist Dr. George T. Grossberg took a more expansive view of ECT in patients with dementia.

"We do recommend ECT for patients with major neurocognitive disorders, either in instances where they have severe or treatment-resistant depression in the context of Alzheimer’s disease – where they tend to respond very well – or on rare occasions in treatment-resistant agitation. After we’ve tried everything else possible and they’re just really difficult to manage, I think a trial of ECT may be warranted. It has a calming, dampening effect on agitation and irritability," said Dr. Grossberg, professor of psychiatry, anatomy, neurobiology, and internal medicine at Saint Louis University.

"One thing it’s important to keep in mind is that if you have depression in the context of Alzheimer’s disease, and you decide to go with ECT because the depression is so severe or refractory, cognition will actually improve. When the depression starts to lift with the ECT, confusion and cognitive impairment will also improve. So I would keep ECT on the agenda," the geriatric psychiatrist added.

Dr. Tang reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Electroconvulsive therapy was safe and effective for treatment of refractory agitation in patients with dementia, including those with multiple medical comorbidities, in the largest case series reported to date.

"This was true at least in the short term. Long term, there are no data," Dr. Yilang Tang noted at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

He presented a retrospective chart review of the 38 patients with dementia who received ECT for agitation at Emory University’s Wesley Woods Geriatric Hospital in Atlanta during 2012.

On admission, patients were on an average of six psychotropic medications, including two or more antipsychotic agents in half of cases. The subjects averaged 6.2 Axis III diagnoses. Patients received a mean of 10.2 and median of 6 ECT treatments. The ECT was performed initially with right unilateral electrode placement in 35 of 38 patients; however, 6 patients were switched to bifrontal placement after four to six sessions because of poor response.

The mean baseline total Pittsburgh Agitation Scale score was 9.2. At discharge, after an average length of stay of 26 days, all patients demonstrated a significant reduction in their agitation score, with a median 8-point drop from baseline. Two patients had transient increases in their agitation score, from 7 points to 11 in one case and from 3 points to 7 in the other, but they improved with maintenance ECT after their acute course of therapy. In addition, patients went from an average of six psychotropic medications at admission to five at discharge, according to Dr. Tang, a psychiatric resident at Emory University in Atlanta.

Most patients were discharged after four to six ECT sessions, although seven patients received more than 12 treatments, mostly delivered as outpatient maintenance therapy.

One patient experienced transient ECT-related delirium. Yet no major treatment-related medical complications occurred, even though 7 patients had coronary artery disease, 24 were hypertensive, 3 had a history of stroke, and 3 patients had heart failure.

Only 2 of 38 patients were readmitted within 1 year after discharge, one of whom got another course of ECT. Although the possibility of readmission at other facilities can’t be ruled out, it seems unlikely that this occurred often, since patients’ surrogates were pleased with the post-ECT clinical improvement, Dr. Tang observed.

Agitation is one of the most distressing behavioral manifestations of dementia for patients, caregivers, and hospital staff. No medication has demonstrated effectiveness in treating this condition.

Subsequent to Dr. Tang’s presentation, two distinguished senior geriatric psychiatrists weighed in on the question of whether ECT has a legitimate role in treating agitation and other behavioral disturbances associated with dementia.

"It’s an unconventional use of the therapy. I would say it would be a fairly rare occurrence. It should not be something that is done commonly," asserted Dr. W. Vaughn McCall, professor of psychiatry and health behavior at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta.

"Remember, the FDA indication for ECT does not include that particular use, although like with medications, you have the right to use a device off label if you can justify it. I would say the key in justifying it is to make sure you’re treating the patient’s distress and [you’re not using it] for the benefit of the nursing home staff. If you’re going to use ECT for a patient with dementia-associated agitation, it needs to be crystal clear that this is being done for the benefit of the patient, that the patient is in distress, and if you can also make the case that there is a concurrent depression along with the major neurocognitive disorder, then possibly you could justify using ECT if all other options have been exhausted," he added.

His fellow panelist Dr. George T. Grossberg took a more expansive view of ECT in patients with dementia.

"We do recommend ECT for patients with major neurocognitive disorders, either in instances where they have severe or treatment-resistant depression in the context of Alzheimer’s disease – where they tend to respond very well – or on rare occasions in treatment-resistant agitation. After we’ve tried everything else possible and they’re just really difficult to manage, I think a trial of ECT may be warranted. It has a calming, dampening effect on agitation and irritability," said Dr. Grossberg, professor of psychiatry, anatomy, neurobiology, and internal medicine at Saint Louis University.

"One thing it’s important to keep in mind is that if you have depression in the context of Alzheimer’s disease, and you decide to go with ECT because the depression is so severe or refractory, cognition will actually improve. When the depression starts to lift with the ECT, confusion and cognitive impairment will also improve. So I would keep ECT on the agenda," the geriatric psychiatrist added.

Dr. Tang reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AT THE AAGP ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: Patients responded to ECT for agitation as a symptom of dementia with an average 8-point drop on the Pittsburgh Agitation Scale from a baseline of 9.2.

Data source: A retrospective study of the 38 patients discharged from one geriatric hospital in 2012 following ECT for dementia-associated agitation.

Disclosures: This was a university-funded study. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Vortioxetine establishes credentials for late-life depression

ORLANDO – The novel antidepressant vortioxetine proved safe, effective, and well tolerated for treatment of major depressive disorder specifically in elderly patients in a combined analysis of nine randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials.

Only one of the trials was restricted to patients aged 65 years or older. This 8-week, double-blind study included 302 patients (mean age, 71 years) randomized to vortioxetine (Brintellix) at 5 mg once daily or placebo. From a baseline mean Hamilton Rating Scale-Depression score of 29.0, scores in the vortioxetine group fell by an average of 3.3 more points than in controls at 8 weeks. The response rate, defined as at least a 50% reduction in depression scores compared with baseline, was 53% in the vortioxetine group, compared with 35% with placebo.

Similarly, scores on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale dropped by an average of 15.5 points in vortioxetine-treated patients, a significantly better performance than the 11.2-point reduction with placebo, Dr. Atul R. Mahableshwarkar reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

The safety analysis incorporated the limited numbers of elderly patients in the other eight randomized, placebo-controlled, short-term studies. There were 286 patients over age 65 who received vortioxetine at 5-20 mg/day and 212 placebo-treated controls. The only side effect significantly more common in vortioxetine-treated patients than in controls was nausea, by a margin of 22.4% to 7.5%. There were no instances of treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction and no signal of increased suicidal ideation in these elderly patients on vortioxetine, according to Dr. Mahableshwarkar, senior medical director at Takeda Pharmaceuticals in Deerfield, Ill.

A clinical efficacy analysis couldn’t be done in any meaningful way for the nine-study overview because the patient numbers on any given dose were too small. While laboratory studies indicated that drug exposure was increased up to 30% in elderly patients, the wide therapeutic index of vortioxetine should make dose adjustments unnecessary, he added.

Vortioxetine at 5-20 mg/day received Food and Drug Administration marketing approval for treatment of major depressive disorder last fall. The drug has multimodal mechanisms of action, directly modulating the activity of the serotonin 5-HT3, 5-HT7, 5-HT1D, 5-HT1B, and 5-HT1A receptors while also inhibiting the 5-HT transporter.

In a separate session on late-life depression held during the AAGP annual meeting, Dr. J. Craig Nelson commented that he considers vortioxetine to be first and foremost a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

"This is a new agent for many of us. We’ll need to get more experience with it to see how important these secondary and tertiary effects really are and at what doses they come into play," said Dr. Nelson, professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco.

One particularly intriguing feature of vortioxetine is that in the elderly-specific randomized trial, it showed evidence of beneficial effects on cognition as expressed in scoring on tests of processing speed, verbal learning, and memory. There are also supportive animal studies.

"This finding will need to be replicated. It’ll be interesting to see how this plays out. It certainly would be nice to have something for depression that’s also perhaps effective for cognitive impairment," he added.

Dr. Mahableshwarkar is an employee of Takeda, which sponsored the nine randomized trials. Dr. Nelson serves as a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, and other companies.

ORLANDO – The novel antidepressant vortioxetine proved safe, effective, and well tolerated for treatment of major depressive disorder specifically in elderly patients in a combined analysis of nine randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials.

Only one of the trials was restricted to patients aged 65 years or older. This 8-week, double-blind study included 302 patients (mean age, 71 years) randomized to vortioxetine (Brintellix) at 5 mg once daily or placebo. From a baseline mean Hamilton Rating Scale-Depression score of 29.0, scores in the vortioxetine group fell by an average of 3.3 more points than in controls at 8 weeks. The response rate, defined as at least a 50% reduction in depression scores compared with baseline, was 53% in the vortioxetine group, compared with 35% with placebo.

Similarly, scores on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale dropped by an average of 15.5 points in vortioxetine-treated patients, a significantly better performance than the 11.2-point reduction with placebo, Dr. Atul R. Mahableshwarkar reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

The safety analysis incorporated the limited numbers of elderly patients in the other eight randomized, placebo-controlled, short-term studies. There were 286 patients over age 65 who received vortioxetine at 5-20 mg/day and 212 placebo-treated controls. The only side effect significantly more common in vortioxetine-treated patients than in controls was nausea, by a margin of 22.4% to 7.5%. There were no instances of treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction and no signal of increased suicidal ideation in these elderly patients on vortioxetine, according to Dr. Mahableshwarkar, senior medical director at Takeda Pharmaceuticals in Deerfield, Ill.

A clinical efficacy analysis couldn’t be done in any meaningful way for the nine-study overview because the patient numbers on any given dose were too small. While laboratory studies indicated that drug exposure was increased up to 30% in elderly patients, the wide therapeutic index of vortioxetine should make dose adjustments unnecessary, he added.

Vortioxetine at 5-20 mg/day received Food and Drug Administration marketing approval for treatment of major depressive disorder last fall. The drug has multimodal mechanisms of action, directly modulating the activity of the serotonin 5-HT3, 5-HT7, 5-HT1D, 5-HT1B, and 5-HT1A receptors while also inhibiting the 5-HT transporter.

In a separate session on late-life depression held during the AAGP annual meeting, Dr. J. Craig Nelson commented that he considers vortioxetine to be first and foremost a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

"This is a new agent for many of us. We’ll need to get more experience with it to see how important these secondary and tertiary effects really are and at what doses they come into play," said Dr. Nelson, professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco.

One particularly intriguing feature of vortioxetine is that in the elderly-specific randomized trial, it showed evidence of beneficial effects on cognition as expressed in scoring on tests of processing speed, verbal learning, and memory. There are also supportive animal studies.

"This finding will need to be replicated. It’ll be interesting to see how this plays out. It certainly would be nice to have something for depression that’s also perhaps effective for cognitive impairment," he added.

Dr. Mahableshwarkar is an employee of Takeda, which sponsored the nine randomized trials. Dr. Nelson serves as a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, and other companies.

ORLANDO – The novel antidepressant vortioxetine proved safe, effective, and well tolerated for treatment of major depressive disorder specifically in elderly patients in a combined analysis of nine randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials.

Only one of the trials was restricted to patients aged 65 years or older. This 8-week, double-blind study included 302 patients (mean age, 71 years) randomized to vortioxetine (Brintellix) at 5 mg once daily or placebo. From a baseline mean Hamilton Rating Scale-Depression score of 29.0, scores in the vortioxetine group fell by an average of 3.3 more points than in controls at 8 weeks. The response rate, defined as at least a 50% reduction in depression scores compared with baseline, was 53% in the vortioxetine group, compared with 35% with placebo.

Similarly, scores on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale dropped by an average of 15.5 points in vortioxetine-treated patients, a significantly better performance than the 11.2-point reduction with placebo, Dr. Atul R. Mahableshwarkar reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

The safety analysis incorporated the limited numbers of elderly patients in the other eight randomized, placebo-controlled, short-term studies. There were 286 patients over age 65 who received vortioxetine at 5-20 mg/day and 212 placebo-treated controls. The only side effect significantly more common in vortioxetine-treated patients than in controls was nausea, by a margin of 22.4% to 7.5%. There were no instances of treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction and no signal of increased suicidal ideation in these elderly patients on vortioxetine, according to Dr. Mahableshwarkar, senior medical director at Takeda Pharmaceuticals in Deerfield, Ill.

A clinical efficacy analysis couldn’t be done in any meaningful way for the nine-study overview because the patient numbers on any given dose were too small. While laboratory studies indicated that drug exposure was increased up to 30% in elderly patients, the wide therapeutic index of vortioxetine should make dose adjustments unnecessary, he added.

Vortioxetine at 5-20 mg/day received Food and Drug Administration marketing approval for treatment of major depressive disorder last fall. The drug has multimodal mechanisms of action, directly modulating the activity of the serotonin 5-HT3, 5-HT7, 5-HT1D, 5-HT1B, and 5-HT1A receptors while also inhibiting the 5-HT transporter.

In a separate session on late-life depression held during the AAGP annual meeting, Dr. J. Craig Nelson commented that he considers vortioxetine to be first and foremost a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

"This is a new agent for many of us. We’ll need to get more experience with it to see how important these secondary and tertiary effects really are and at what doses they come into play," said Dr. Nelson, professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco.

One particularly intriguing feature of vortioxetine is that in the elderly-specific randomized trial, it showed evidence of beneficial effects on cognition as expressed in scoring on tests of processing speed, verbal learning, and memory. There are also supportive animal studies.

"This finding will need to be replicated. It’ll be interesting to see how this plays out. It certainly would be nice to have something for depression that’s also perhaps effective for cognitive impairment," he added.

Dr. Mahableshwarkar is an employee of Takeda, which sponsored the nine randomized trials. Dr. Nelson serves as a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, and other companies.

AT THE AAGP ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: Hamilton Rating Scale–Depression scores among those in the vortioxetine group fell by an average of 3.3 more points than in controls at 8 weeks. The response rate, defined as at least a 50% reduction in depression scores compared with baseline, was 53% in the vortioxetine group, compared to 35% with placebo.

Data source: This was an analysis of the 498 patients over age 65 with major depressive disorder who participated in nine randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials.

Disclosures: Dr. Mahableshwarkar is an employee of Takeda, which sponsored the nine randomized trials. Dr. Nelson serves as a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, and other companies.

Say goodbye to ‘dementia’

ORLANDO – This May, the hallowed term "dementia" is supposed to be tossed onto the scrapheap of discarded psychiatric nomenclature, replaced by "major neurocognitive disorder."

When the DSM-5 was released in May 2013, the American Psychiatric Association gave a year’s grace period for the world to absorb the changes before they take effect. "Dementia" was replaced in the DSM-5 because the term was deemed stigmatizing; the rough translation from the Latin roots is "loss of mind." Acknowledging that old habits die hard, however, the DSM-5 also states that use of the term is not precluded "where that term is standard."

The old DSM-IV category of delirium, dementia, and amnestic and other cognitive disorders has been replaced in the DSM-5 by the neurocognitive disorders category. Major or mild neurocognitive disorder from Alzheimer’s disease is included under this new category. At the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, Dr. W. Vaughn McCall and Dr. George T. Grossberg highlighted the changes.

"Major neurocognitive disorder" is a syndrome, which includes what was formerly known as dementia. The distinction between it and the new "mild neurocognitive disorder," previously known as mild cognitive impairment or MCI, is necessarily somewhat arbitrary. Major neurocognitive disorder requires "significant" cognitive decline in one or more cognitive domains as noted by the patient, family member, or clinician along with objective evidence of "substantial" impaired cognition compared to normative test values.

"In contrast, the requirements for mild neurocognitive disorder are ‘mild’ cognitive decline observed by patient, family member, or clinician and ‘modest’ impairment on testing, explained Dr. McCall, professor of psychiatry and health behavior at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta.

Dr. Grossberg offered two practical tips in drawing the distinction between major and mild neurocognitive disorder. One is whether the cognitive deficits are sufficiently limited in scope that the patient is still able to function independently in everyday activities.

"If they’re not, I’m moving from [mild] to major," said Dr. Grossberg, professor of psychiatry, neurobiology, and internal medicine at Saint Louis University.

Also, if neuropsychologic testing focusing on memory is performed, Dr. Grossberg wants to see at least a one standard deviation below the expected age- and education-adjusted norms before calling it objective evidence of "substantial" impaired cognition rising to the level of major neurocognitive disorder.

Since major neurocognitive disorder is a syndrome, Dr. McCall said, it’s important to try to specify its nature. For the condition to qualify as major neurocognitive disorder from Alzheimer’s disease under the DSM-5, the impairment in cognition must be insidious in onset and gradual in progression. The patient must either have a causative Alzheimer’s disease mutation, which is present in less than 1% of all cases of the disease, or else the patient must meet three criteria: a decline in memory and learning, plus at least one additional cognitive domain; a steady decline without extended plateaus; and no evidence of mixed etiology involving cardiovascular disease or other disorders.

"There’s no requirement that memory impairment be the first affected domain. That’s a bit of a change," the psychiatrist noted.

The office-based assessment of neurocognitive disorders as recommended in the DSM-5 includes a careful history and an objective measure of cognitive function such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, the Saint Louis University Mental Status Evaluation, and the Mini-Mental State Examination. The patient’s ability to perform activities of daily living should be objectively evaluated, as by the Katz Index of Activities of Daily Living scale or the Barthel Index. A screening neurologic exam should be part of the work-up; this can be performed by a primary care physician or a neurologist if the psychiatrist prefers. Since major neurocognitive disorder is a syndrome, the DSM-5 does not require imaging via MRI or CT, although both Dr. McCall and Dr. Grossberg said this was a controversial issue during the creation of the DSM-5, and they recommend one-time baseline neuroimaging in order to rule out a tumor, old stroke, or frontotemporal atrophy.

Laboratory tests deemed an essential part of the work-up are a complete metabolic profile, thyroid stimulating hormone, a complete blood count, urinalysis, and folate.

In addition, Dr. Grossberg said, many memory clinics now routinely include measurements of vitamin D level, homocysteine, and C-reactive protein in the work-up.

"Vitamin D deficiency is extremely common. We’re finding in St. Louis – and I don’t think it’s a whole lot different among the elderly even in Florida, where there’s a lot of sun – that people are afraid of the sun now so they put on a whole lot of sunscreen, preventing vitamin D absorption. We check vitamin D levels routinely in our clinic, and maybe two out of every three older adults we test are low in vitamin D. More and more research shows that deficiency may be related to depression and may also have an effect on cognition. It’s something that’s easily remediable. We give 50,000 IU orally per week for 8 weeks, then a maintenance dose of 1,000-2,000 IU/day," Dr. Grossman said.

Elevated homocysteine and C-reactive protein levels are implicated in cardiovascular disease and also increasingly under scrutiny in Alzheimer’s disease. High homocysteine levels can readily be lowered with folate, and 81 mg/day of aspirin may be sufficient to reduce C-reactive protein, he added.

"Delirium" is the one neurocognitive disorder that’s essentially unchanged from the DSM-IV, according to Dr. McCall and Dr. Grossberg. This condition is characterized by rapid onset and fluctuations in severity during the day and must be linked to the physiologic consequences of a medical condition.

Dr. McCall reported receiving research grants from the National Institute of Mental Health and Merck. Dr. Grossberg serves as a consultant to Forest Laboratories, Lundbeck, Novartis, Otsuka, and Takeda.

ORLANDO – This May, the hallowed term "dementia" is supposed to be tossed onto the scrapheap of discarded psychiatric nomenclature, replaced by "major neurocognitive disorder."

When the DSM-5 was released in May 2013, the American Psychiatric Association gave a year’s grace period for the world to absorb the changes before they take effect. "Dementia" was replaced in the DSM-5 because the term was deemed stigmatizing; the rough translation from the Latin roots is "loss of mind." Acknowledging that old habits die hard, however, the DSM-5 also states that use of the term is not precluded "where that term is standard."

The old DSM-IV category of delirium, dementia, and amnestic and other cognitive disorders has been replaced in the DSM-5 by the neurocognitive disorders category. Major or mild neurocognitive disorder from Alzheimer’s disease is included under this new category. At the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, Dr. W. Vaughn McCall and Dr. George T. Grossberg highlighted the changes.

"Major neurocognitive disorder" is a syndrome, which includes what was formerly known as dementia. The distinction between it and the new "mild neurocognitive disorder," previously known as mild cognitive impairment or MCI, is necessarily somewhat arbitrary. Major neurocognitive disorder requires "significant" cognitive decline in one or more cognitive domains as noted by the patient, family member, or clinician along with objective evidence of "substantial" impaired cognition compared to normative test values.

"In contrast, the requirements for mild neurocognitive disorder are ‘mild’ cognitive decline observed by patient, family member, or clinician and ‘modest’ impairment on testing, explained Dr. McCall, professor of psychiatry and health behavior at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta.

Dr. Grossberg offered two practical tips in drawing the distinction between major and mild neurocognitive disorder. One is whether the cognitive deficits are sufficiently limited in scope that the patient is still able to function independently in everyday activities.

"If they’re not, I’m moving from [mild] to major," said Dr. Grossberg, professor of psychiatry, neurobiology, and internal medicine at Saint Louis University.

Also, if neuropsychologic testing focusing on memory is performed, Dr. Grossberg wants to see at least a one standard deviation below the expected age- and education-adjusted norms before calling it objective evidence of "substantial" impaired cognition rising to the level of major neurocognitive disorder.

Since major neurocognitive disorder is a syndrome, Dr. McCall said, it’s important to try to specify its nature. For the condition to qualify as major neurocognitive disorder from Alzheimer’s disease under the DSM-5, the impairment in cognition must be insidious in onset and gradual in progression. The patient must either have a causative Alzheimer’s disease mutation, which is present in less than 1% of all cases of the disease, or else the patient must meet three criteria: a decline in memory and learning, plus at least one additional cognitive domain; a steady decline without extended plateaus; and no evidence of mixed etiology involving cardiovascular disease or other disorders.

"There’s no requirement that memory impairment be the first affected domain. That’s a bit of a change," the psychiatrist noted.

The office-based assessment of neurocognitive disorders as recommended in the DSM-5 includes a careful history and an objective measure of cognitive function such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, the Saint Louis University Mental Status Evaluation, and the Mini-Mental State Examination. The patient’s ability to perform activities of daily living should be objectively evaluated, as by the Katz Index of Activities of Daily Living scale or the Barthel Index. A screening neurologic exam should be part of the work-up; this can be performed by a primary care physician or a neurologist if the psychiatrist prefers. Since major neurocognitive disorder is a syndrome, the DSM-5 does not require imaging via MRI or CT, although both Dr. McCall and Dr. Grossberg said this was a controversial issue during the creation of the DSM-5, and they recommend one-time baseline neuroimaging in order to rule out a tumor, old stroke, or frontotemporal atrophy.

Laboratory tests deemed an essential part of the work-up are a complete metabolic profile, thyroid stimulating hormone, a complete blood count, urinalysis, and folate.

In addition, Dr. Grossberg said, many memory clinics now routinely include measurements of vitamin D level, homocysteine, and C-reactive protein in the work-up.

"Vitamin D deficiency is extremely common. We’re finding in St. Louis – and I don’t think it’s a whole lot different among the elderly even in Florida, where there’s a lot of sun – that people are afraid of the sun now so they put on a whole lot of sunscreen, preventing vitamin D absorption. We check vitamin D levels routinely in our clinic, and maybe two out of every three older adults we test are low in vitamin D. More and more research shows that deficiency may be related to depression and may also have an effect on cognition. It’s something that’s easily remediable. We give 50,000 IU orally per week for 8 weeks, then a maintenance dose of 1,000-2,000 IU/day," Dr. Grossman said.

Elevated homocysteine and C-reactive protein levels are implicated in cardiovascular disease and also increasingly under scrutiny in Alzheimer’s disease. High homocysteine levels can readily be lowered with folate, and 81 mg/day of aspirin may be sufficient to reduce C-reactive protein, he added.