User login

American Academy of Pain Medicine (AAPM): Annual Meeting

Group refines existing opioid misuse risk assessment tool

FORT LAUDERDALE, FLA. – Analysis of data from more than 13,000 patients at a large pain management practice shows that a self-reported history of sexual abuse and issues with anger, impairment of life control, marital status, and level of education are among predictors of patients’ tendency to misuse opioids.

The physician group, led by Dr. Mark Gostine, is planning to use the findings to help refine the specificity and sensitivity of an existing opioid risk assessment tool called the Opioid Risk Tool (ORT).

"What we’re trying to do is to take ORT 1.0 and create ORT 2.0," said Dr. Gostine, president of Michigan Pain Consultants in Grand Rapids.

The ORT was developed by Dr. Lynn Webster with the aim of identifying patients at risk of misusing opioids (Pain Med. 2005;6:432-42). The questionnaireseeks personal and family history of substance abuse, history of preadolescent sexual abuse, and a history of certain psychological disorders.

"The Gostine study is a significant contribution because of the number of subjects in the analysis," said Dr. Webster, who was not involved in the study. "I’m not aware of any opioid risk tool that has been evaluated in such a large population. It supports the risk factors that are identified in the Opioid Risk Tool but also suggests that the ORT could be improved with some modification."

The abuse of prescription drugs and overdoses stemming from their use became one of the top public health concerns starting in the 1990s. Their abuse continues to be the fastest-growing drug problem in the United States (MMWR 2012;61:10-13). The increase in unintentional overdoses has been mostly driven by opioids in recent years, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Physicians at Michigan Pain Consultants have been using the five-question ORT as part of their 120-question Pain Health Assessment that they give to chronic pain patients on an iPad prior to seeing the doctor. The form assesses disease presence, pain characteristics, physical function, and psychosocial function.

"Anybody with a high ORT score had a problem with narcotics," said Dr. Gostine in an interview. "However, two-thirds of the patients who misused narcotics had low ORT scores. So we wanted to find out what other elements in our database indicated that these patients are problematic, and can we use that to predict which patients will misuse medications."

They conducted an analysis of observed behaviors associated with narcotic misuse and/or patients on high-dose narcotics.

Dr. Gostine and his colleagues identified "miscreants" (256 patients) as patients who were flagged by the Michigan Automated Pharmacy Surveillance Program, had abnormal urine drug screens, had problems managing opiate prescriptions, and/or had poor behavior with clinic staff regarding opiate prescriptions. They also identified an additional 704 patients who consumed a high dose of narcotics, defined as greater than 100 mg of oral morphine equivalents per day. The investigators then compared the data on these two groups with the rest of their patient population (n = 13,026).

The investigators found a higher ORT score significantly more often among people with miscreant behavior (11%) than among those with high-dose opioid use (5%) or controls (4%). Low ORT scores occurred in 66% of individuals with miscreant behavior, compared with 73% of people in the high-dose group and 82% of the control group, Dr. Gostine said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pain Medicine.

The results also showed a correlation between the distress index – which uses a Likert-type numerical scale to score responses to questions relating to anger, depression/anxiety, and life control – and those identified as miscreants and those who consumed high doses of narcotics.

In addition, a history of sexual abuse was associated with being a miscreant (14%) and high-dose consumer (12%), compared with the control group (8%).

"Two other factors emerged: Marital status seems to be predictive, and patients with a higher level of education seem to be less likely to misuse," said Dr. Gostine. "Never married increases the risk of being a miscreant by 100% versus currently married. With our large numbers of miscreants and controls, this is highly significant, but these are early, provisional numbers."

He added that the rate of miscreant behavior among high school graduates is 50% higher than that of 4-year college graduates. "This is also significant, but these are provisional numbers," he said. "We have also confirmed the link with smoking and prescription drug misuse. Smoking almost doubles the risk of opioid misuse, again a provisional number, which we will look at in more detail with the larger numbers [1,800] we have now accrued."

Dr. Gostine said that he is planning to publish the findings. After refinement of the ORT, which is currently in the public domain and available to physicians, the tool might expand to 15 questions – a short-enough questionnaire that patients can fill out in 2 or 3 minutes. If the questionnaires are fed into electronic medical records, as they are in Dr. Gostine’s practice, "the doctor can find out whether [the patient] is someone they should be nervous about or someone they can trust" when it comes to prescribing opioids.

Dr. Gostine and his partner, Dr. Fred Davis, developed the Prism Pain Health Assessment that was used to capture and analyze the data. The product is now commercially available. Dr. Webster has received honoraria/travel support from AstraZeneca, Covidien Mallinckrodt, and other companies.

FORT LAUDERDALE, FLA. – Analysis of data from more than 13,000 patients at a large pain management practice shows that a self-reported history of sexual abuse and issues with anger, impairment of life control, marital status, and level of education are among predictors of patients’ tendency to misuse opioids.

The physician group, led by Dr. Mark Gostine, is planning to use the findings to help refine the specificity and sensitivity of an existing opioid risk assessment tool called the Opioid Risk Tool (ORT).

"What we’re trying to do is to take ORT 1.0 and create ORT 2.0," said Dr. Gostine, president of Michigan Pain Consultants in Grand Rapids.

The ORT was developed by Dr. Lynn Webster with the aim of identifying patients at risk of misusing opioids (Pain Med. 2005;6:432-42). The questionnaireseeks personal and family history of substance abuse, history of preadolescent sexual abuse, and a history of certain psychological disorders.

"The Gostine study is a significant contribution because of the number of subjects in the analysis," said Dr. Webster, who was not involved in the study. "I’m not aware of any opioid risk tool that has been evaluated in such a large population. It supports the risk factors that are identified in the Opioid Risk Tool but also suggests that the ORT could be improved with some modification."

The abuse of prescription drugs and overdoses stemming from their use became one of the top public health concerns starting in the 1990s. Their abuse continues to be the fastest-growing drug problem in the United States (MMWR 2012;61:10-13). The increase in unintentional overdoses has been mostly driven by opioids in recent years, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Physicians at Michigan Pain Consultants have been using the five-question ORT as part of their 120-question Pain Health Assessment that they give to chronic pain patients on an iPad prior to seeing the doctor. The form assesses disease presence, pain characteristics, physical function, and psychosocial function.

"Anybody with a high ORT score had a problem with narcotics," said Dr. Gostine in an interview. "However, two-thirds of the patients who misused narcotics had low ORT scores. So we wanted to find out what other elements in our database indicated that these patients are problematic, and can we use that to predict which patients will misuse medications."

They conducted an analysis of observed behaviors associated with narcotic misuse and/or patients on high-dose narcotics.

Dr. Gostine and his colleagues identified "miscreants" (256 patients) as patients who were flagged by the Michigan Automated Pharmacy Surveillance Program, had abnormal urine drug screens, had problems managing opiate prescriptions, and/or had poor behavior with clinic staff regarding opiate prescriptions. They also identified an additional 704 patients who consumed a high dose of narcotics, defined as greater than 100 mg of oral morphine equivalents per day. The investigators then compared the data on these two groups with the rest of their patient population (n = 13,026).

The investigators found a higher ORT score significantly more often among people with miscreant behavior (11%) than among those with high-dose opioid use (5%) or controls (4%). Low ORT scores occurred in 66% of individuals with miscreant behavior, compared with 73% of people in the high-dose group and 82% of the control group, Dr. Gostine said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pain Medicine.

The results also showed a correlation between the distress index – which uses a Likert-type numerical scale to score responses to questions relating to anger, depression/anxiety, and life control – and those identified as miscreants and those who consumed high doses of narcotics.

In addition, a history of sexual abuse was associated with being a miscreant (14%) and high-dose consumer (12%), compared with the control group (8%).

"Two other factors emerged: Marital status seems to be predictive, and patients with a higher level of education seem to be less likely to misuse," said Dr. Gostine. "Never married increases the risk of being a miscreant by 100% versus currently married. With our large numbers of miscreants and controls, this is highly significant, but these are early, provisional numbers."

He added that the rate of miscreant behavior among high school graduates is 50% higher than that of 4-year college graduates. "This is also significant, but these are provisional numbers," he said. "We have also confirmed the link with smoking and prescription drug misuse. Smoking almost doubles the risk of opioid misuse, again a provisional number, which we will look at in more detail with the larger numbers [1,800] we have now accrued."

Dr. Gostine said that he is planning to publish the findings. After refinement of the ORT, which is currently in the public domain and available to physicians, the tool might expand to 15 questions – a short-enough questionnaire that patients can fill out in 2 or 3 minutes. If the questionnaires are fed into electronic medical records, as they are in Dr. Gostine’s practice, "the doctor can find out whether [the patient] is someone they should be nervous about or someone they can trust" when it comes to prescribing opioids.

Dr. Gostine and his partner, Dr. Fred Davis, developed the Prism Pain Health Assessment that was used to capture and analyze the data. The product is now commercially available. Dr. Webster has received honoraria/travel support from AstraZeneca, Covidien Mallinckrodt, and other companies.

FORT LAUDERDALE, FLA. – Analysis of data from more than 13,000 patients at a large pain management practice shows that a self-reported history of sexual abuse and issues with anger, impairment of life control, marital status, and level of education are among predictors of patients’ tendency to misuse opioids.

The physician group, led by Dr. Mark Gostine, is planning to use the findings to help refine the specificity and sensitivity of an existing opioid risk assessment tool called the Opioid Risk Tool (ORT).

"What we’re trying to do is to take ORT 1.0 and create ORT 2.0," said Dr. Gostine, president of Michigan Pain Consultants in Grand Rapids.

The ORT was developed by Dr. Lynn Webster with the aim of identifying patients at risk of misusing opioids (Pain Med. 2005;6:432-42). The questionnaireseeks personal and family history of substance abuse, history of preadolescent sexual abuse, and a history of certain psychological disorders.

"The Gostine study is a significant contribution because of the number of subjects in the analysis," said Dr. Webster, who was not involved in the study. "I’m not aware of any opioid risk tool that has been evaluated in such a large population. It supports the risk factors that are identified in the Opioid Risk Tool but also suggests that the ORT could be improved with some modification."

The abuse of prescription drugs and overdoses stemming from their use became one of the top public health concerns starting in the 1990s. Their abuse continues to be the fastest-growing drug problem in the United States (MMWR 2012;61:10-13). The increase in unintentional overdoses has been mostly driven by opioids in recent years, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Physicians at Michigan Pain Consultants have been using the five-question ORT as part of their 120-question Pain Health Assessment that they give to chronic pain patients on an iPad prior to seeing the doctor. The form assesses disease presence, pain characteristics, physical function, and psychosocial function.

"Anybody with a high ORT score had a problem with narcotics," said Dr. Gostine in an interview. "However, two-thirds of the patients who misused narcotics had low ORT scores. So we wanted to find out what other elements in our database indicated that these patients are problematic, and can we use that to predict which patients will misuse medications."

They conducted an analysis of observed behaviors associated with narcotic misuse and/or patients on high-dose narcotics.

Dr. Gostine and his colleagues identified "miscreants" (256 patients) as patients who were flagged by the Michigan Automated Pharmacy Surveillance Program, had abnormal urine drug screens, had problems managing opiate prescriptions, and/or had poor behavior with clinic staff regarding opiate prescriptions. They also identified an additional 704 patients who consumed a high dose of narcotics, defined as greater than 100 mg of oral morphine equivalents per day. The investigators then compared the data on these two groups with the rest of their patient population (n = 13,026).

The investigators found a higher ORT score significantly more often among people with miscreant behavior (11%) than among those with high-dose opioid use (5%) or controls (4%). Low ORT scores occurred in 66% of individuals with miscreant behavior, compared with 73% of people in the high-dose group and 82% of the control group, Dr. Gostine said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pain Medicine.

The results also showed a correlation between the distress index – which uses a Likert-type numerical scale to score responses to questions relating to anger, depression/anxiety, and life control – and those identified as miscreants and those who consumed high doses of narcotics.

In addition, a history of sexual abuse was associated with being a miscreant (14%) and high-dose consumer (12%), compared with the control group (8%).

"Two other factors emerged: Marital status seems to be predictive, and patients with a higher level of education seem to be less likely to misuse," said Dr. Gostine. "Never married increases the risk of being a miscreant by 100% versus currently married. With our large numbers of miscreants and controls, this is highly significant, but these are early, provisional numbers."

He added that the rate of miscreant behavior among high school graduates is 50% higher than that of 4-year college graduates. "This is also significant, but these are provisional numbers," he said. "We have also confirmed the link with smoking and prescription drug misuse. Smoking almost doubles the risk of opioid misuse, again a provisional number, which we will look at in more detail with the larger numbers [1,800] we have now accrued."

Dr. Gostine said that he is planning to publish the findings. After refinement of the ORT, which is currently in the public domain and available to physicians, the tool might expand to 15 questions – a short-enough questionnaire that patients can fill out in 2 or 3 minutes. If the questionnaires are fed into electronic medical records, as they are in Dr. Gostine’s practice, "the doctor can find out whether [the patient] is someone they should be nervous about or someone they can trust" when it comes to prescribing opioids.

Dr. Gostine and his partner, Dr. Fred Davis, developed the Prism Pain Health Assessment that was used to capture and analyze the data. The product is now commercially available. Dr. Webster has received honoraria/travel support from AstraZeneca, Covidien Mallinckrodt, and other companies.

AT THE AAPM ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: In an effort to detect patients who are at high risk for opioid abuse or overdose, investigators found that a history of sexual abuse was associated with miscreant behavior (14%) and high-dose opioid consumption (12%), compared with a control group (8%).

Data source: Analysis of data from more than 13,000 patients at a large pain management practice in Grand Rapids, Mich.

Disclosures: Dr. Gostine and his partner, Dr. Fred Davis, developed the Prism Pain Health Assessment that was used to capture and analyze the data. The product is now a commercially available. Dr. Webster has received honoraria/travel support from AstraZeneca, Covidien Mallinckrodt, and other companies.

Eight principles for safe opioid prescribing

FORT LAUDERDALE, FLA. – Opioids aren’t always appropriate for treating pain, and if they have to be prescribed, they must be used cautiously and at the lowest effective dosage, Dr. Lynn R. Webster advised.

Misuse and abuse of pharmaceuticals including opioids rank high among the nation’s public health concerns. Emergency department visits involving these drugs increased from 627,000 in 2004 to nearly 1,430,000 in 2011, according to the latest data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Narcotic pain relievers were among the most commonly misused or abused drug (134.8 ED visits per 100,000 population).

And while the majority of overdose deaths due to opioids occur in people who obtain them illegally, "there’s a subset that physicians are responsible for," Dr. Webster, president of the American Academy of Pain Medicine, said at the academy’s annual meeting.

For the past 8 years, since Utah’s medical examiner was quoted on the front page of a local newspaper saying that there was an epidemic of overdose deaths from prescription drugs, Dr. Webster has been on a mission to establish easy-to-follow, evidence-based principles for safe opioid prescribing in outpatient settings.

Various guidelines on safe opioid prescribing are currently available, "and they are all useful and helpful, but, in my view, not specific-enough to have an immediate impact," Dr. Webster said in an interview. "They address grander, larger problems. But these eight principles are specifically targeted to prevent deaths."

For easy recall, the principles are summed up in the trademarked acronym: RELIABLE – Respiratory, Experience, Long term, Initiating methadone, Apnea, Benzodiazepine, Look for comorbidities, and Exercise caution with switching. They’re now part of the AAPM’s Safe Opioid Prescribing Initiative:

• Respiratory: If you have a patient who is on long-term opioids and develops a respiratory condition (asthma, pneumonia, flu), reduce the opioid dose by 20%-30%.

• Experience: Assess the patient before prescribing opioids. Find out what the biologic, social, and psychiatric risk factors are.

• Long term: Extended-release opioids should not be used for acute pain. "And that’s the bottom line," said Dr. Webster.

• Initiating methadone: "Never start anybody on more than 15 mg a day," Dr. Webster advised, adding that the wrong starting dose for methadone can be lethal. "There are reported deaths of people on 30 mg a day."

• Apnea: Screen for obstructive and central sleep apnea. Screen for hypoxemia. "Patients that are on 150 mg morphine-equivalent, people who are very overweight, people who are infirm and elderly people, we need to make sure that opioids are safe for them, and we need to do sleep studies."

• Benzodiazepines: "Should be avoided if at all possible when you are prescribing opioids," because in the face of benzodiazepines, the toxicity of opioids is significantly enhanced. "If a benzo is used, reduce the dose of opioids. And look for an alternative (to benzodiazepines) if you have to prescribe an opioid."

• Look for comorbidities: Find out if patients have a history of bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, stress, "and particularly general anxiety disorder." Patients will often misuse the medications for their mental health disorder instead of their pain.

• Exercise caution with rotation: "Conversion tables and equal analgesic tables should not be used to determine the starting dose of opioids. You have to assume that everybody is opioid naive, and start on a low dose, and titrate slowly to a level that you think is the maximum dose you think you can safely prescribe.

"Physicians can have an impact in reducing the number of overdose deaths, but it’s going to require a little bit of effort to learn these eight principles, and if we all do this, I think we’ll see a dramatic reduction in overdose deaths," Dr. Webster said.

The principles are likely to be published soon, he said, and they will be available on the AAPM’s website in the near future.

Dr. Webster said he had received honoraria/travel support from AstraZeneca, Covidien Mallinckrodt, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Nektar Therapeutics, Pfizer, and Salix.

On Twitter @NaseemSMiller

FORT LAUDERDALE, FLA. – Opioids aren’t always appropriate for treating pain, and if they have to be prescribed, they must be used cautiously and at the lowest effective dosage, Dr. Lynn R. Webster advised.

Misuse and abuse of pharmaceuticals including opioids rank high among the nation’s public health concerns. Emergency department visits involving these drugs increased from 627,000 in 2004 to nearly 1,430,000 in 2011, according to the latest data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Narcotic pain relievers were among the most commonly misused or abused drug (134.8 ED visits per 100,000 population).

And while the majority of overdose deaths due to opioids occur in people who obtain them illegally, "there’s a subset that physicians are responsible for," Dr. Webster, president of the American Academy of Pain Medicine, said at the academy’s annual meeting.

For the past 8 years, since Utah’s medical examiner was quoted on the front page of a local newspaper saying that there was an epidemic of overdose deaths from prescription drugs, Dr. Webster has been on a mission to establish easy-to-follow, evidence-based principles for safe opioid prescribing in outpatient settings.

Various guidelines on safe opioid prescribing are currently available, "and they are all useful and helpful, but, in my view, not specific-enough to have an immediate impact," Dr. Webster said in an interview. "They address grander, larger problems. But these eight principles are specifically targeted to prevent deaths."

For easy recall, the principles are summed up in the trademarked acronym: RELIABLE – Respiratory, Experience, Long term, Initiating methadone, Apnea, Benzodiazepine, Look for comorbidities, and Exercise caution with switching. They’re now part of the AAPM’s Safe Opioid Prescribing Initiative:

• Respiratory: If you have a patient who is on long-term opioids and develops a respiratory condition (asthma, pneumonia, flu), reduce the opioid dose by 20%-30%.

• Experience: Assess the patient before prescribing opioids. Find out what the biologic, social, and psychiatric risk factors are.

• Long term: Extended-release opioids should not be used for acute pain. "And that’s the bottom line," said Dr. Webster.

• Initiating methadone: "Never start anybody on more than 15 mg a day," Dr. Webster advised, adding that the wrong starting dose for methadone can be lethal. "There are reported deaths of people on 30 mg a day."

• Apnea: Screen for obstructive and central sleep apnea. Screen for hypoxemia. "Patients that are on 150 mg morphine-equivalent, people who are very overweight, people who are infirm and elderly people, we need to make sure that opioids are safe for them, and we need to do sleep studies."

• Benzodiazepines: "Should be avoided if at all possible when you are prescribing opioids," because in the face of benzodiazepines, the toxicity of opioids is significantly enhanced. "If a benzo is used, reduce the dose of opioids. And look for an alternative (to benzodiazepines) if you have to prescribe an opioid."

• Look for comorbidities: Find out if patients have a history of bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, stress, "and particularly general anxiety disorder." Patients will often misuse the medications for their mental health disorder instead of their pain.

• Exercise caution with rotation: "Conversion tables and equal analgesic tables should not be used to determine the starting dose of opioids. You have to assume that everybody is opioid naive, and start on a low dose, and titrate slowly to a level that you think is the maximum dose you think you can safely prescribe.

"Physicians can have an impact in reducing the number of overdose deaths, but it’s going to require a little bit of effort to learn these eight principles, and if we all do this, I think we’ll see a dramatic reduction in overdose deaths," Dr. Webster said.

The principles are likely to be published soon, he said, and they will be available on the AAPM’s website in the near future.

Dr. Webster said he had received honoraria/travel support from AstraZeneca, Covidien Mallinckrodt, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Nektar Therapeutics, Pfizer, and Salix.

On Twitter @NaseemSMiller

FORT LAUDERDALE, FLA. – Opioids aren’t always appropriate for treating pain, and if they have to be prescribed, they must be used cautiously and at the lowest effective dosage, Dr. Lynn R. Webster advised.

Misuse and abuse of pharmaceuticals including opioids rank high among the nation’s public health concerns. Emergency department visits involving these drugs increased from 627,000 in 2004 to nearly 1,430,000 in 2011, according to the latest data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Narcotic pain relievers were among the most commonly misused or abused drug (134.8 ED visits per 100,000 population).

And while the majority of overdose deaths due to opioids occur in people who obtain them illegally, "there’s a subset that physicians are responsible for," Dr. Webster, president of the American Academy of Pain Medicine, said at the academy’s annual meeting.

For the past 8 years, since Utah’s medical examiner was quoted on the front page of a local newspaper saying that there was an epidemic of overdose deaths from prescription drugs, Dr. Webster has been on a mission to establish easy-to-follow, evidence-based principles for safe opioid prescribing in outpatient settings.

Various guidelines on safe opioid prescribing are currently available, "and they are all useful and helpful, but, in my view, not specific-enough to have an immediate impact," Dr. Webster said in an interview. "They address grander, larger problems. But these eight principles are specifically targeted to prevent deaths."

For easy recall, the principles are summed up in the trademarked acronym: RELIABLE – Respiratory, Experience, Long term, Initiating methadone, Apnea, Benzodiazepine, Look for comorbidities, and Exercise caution with switching. They’re now part of the AAPM’s Safe Opioid Prescribing Initiative:

• Respiratory: If you have a patient who is on long-term opioids and develops a respiratory condition (asthma, pneumonia, flu), reduce the opioid dose by 20%-30%.

• Experience: Assess the patient before prescribing opioids. Find out what the biologic, social, and psychiatric risk factors are.

• Long term: Extended-release opioids should not be used for acute pain. "And that’s the bottom line," said Dr. Webster.

• Initiating methadone: "Never start anybody on more than 15 mg a day," Dr. Webster advised, adding that the wrong starting dose for methadone can be lethal. "There are reported deaths of people on 30 mg a day."

• Apnea: Screen for obstructive and central sleep apnea. Screen for hypoxemia. "Patients that are on 150 mg morphine-equivalent, people who are very overweight, people who are infirm and elderly people, we need to make sure that opioids are safe for them, and we need to do sleep studies."

• Benzodiazepines: "Should be avoided if at all possible when you are prescribing opioids," because in the face of benzodiazepines, the toxicity of opioids is significantly enhanced. "If a benzo is used, reduce the dose of opioids. And look for an alternative (to benzodiazepines) if you have to prescribe an opioid."

• Look for comorbidities: Find out if patients have a history of bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, stress, "and particularly general anxiety disorder." Patients will often misuse the medications for their mental health disorder instead of their pain.

• Exercise caution with rotation: "Conversion tables and equal analgesic tables should not be used to determine the starting dose of opioids. You have to assume that everybody is opioid naive, and start on a low dose, and titrate slowly to a level that you think is the maximum dose you think you can safely prescribe.

"Physicians can have an impact in reducing the number of overdose deaths, but it’s going to require a little bit of effort to learn these eight principles, and if we all do this, I think we’ll see a dramatic reduction in overdose deaths," Dr. Webster said.

The principles are likely to be published soon, he said, and they will be available on the AAPM’s website in the near future.

Dr. Webster said he had received honoraria/travel support from AstraZeneca, Covidien Mallinckrodt, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Nektar Therapeutics, Pfizer, and Salix.

On Twitter @NaseemSMiller

AT THE AAPM ANNUAL MEETING

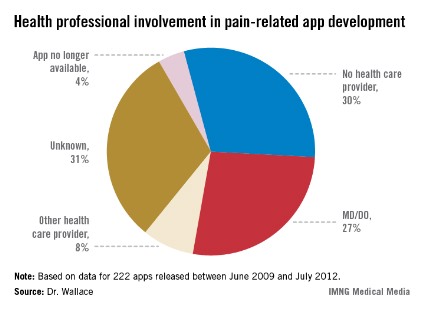

Most pain apps lack physician input

FORT LAUDERDALE, FLA. – An evaluation of 222 pain-related smartphone apps showed that many were developed without the input of a health professional, some had inaccurate information, and some of their features weren’t as robust as they could be.

"Many of them were giving advice and offering coping strategies, but we don’t know if they’re effective," said Lorraine S. Wallace, Ph.D., who led the study. In addition, the apps could potentially be dangerous for users if the coping strategy – for instance, exercise – isn’t right for them, she said.

Experts have begun studying the safety and efficacy of health-related smartphone apps, many of which are aimed at patients for managing various diseases and conditions.

Dr. Wallace said that, ideally, app developers, physicians, and patients should collaborate to create the apps. "And there needs to be a list of good apps. I always get asked ‘show us a good app,’ so there are definitely some features that we should look at, and that should be driven by health care professionals to determine what a pain app should look like," she said. She advised physicians to be aware of the apps that are currently available to patients.

Dr. Wallace said her study was modeled after a 2011 British study of 111 pain-related apps. The authors of that study also concluded, "Pain apps appear to be able to promise pain relief without any concern for the effectiveness of the product, or for possible adverse effects of product use. In a population often desperate for a solution to distressing and debilitating pain conditions, there is considerable risk of individuals being misled" (J. Telemed. Telecare. 2011;17:308-12).

Dr. Wallace of the department of family medicine and director of research at the Ohio State University in Columbus said that in her evaluation, she didn’t find an ideal pain-related app. "There were certain ones that had better features such as pain diaries or other characteristics, but most of them were not that comprehensive."

Dr. Wallace and her colleagues searched Apple, Android, and Blackberry app stores for the word "pain." They chose 222 apps, and evaluated certain information such as cost, purpose, and key features and documentation of medical professional involvement in design and/or content.

The apps were released between June 2009 and July 2012, with an average cost of $4.99 or less (only seven apps cost more than $9.99). Researchers didn’t purchase any of the apps.

Pain diaries, exercises, and coping strategies were the most common app features. Many apps focused on general pain (93), 57 addressed back and/or neck pain, and 21 dealt with migraine/headache pain. Researchers found one app for muscle pain and one for pain from each of the following conditions: fibromyalgia, menstruation, injury, patellar tendonitis, rheumatism, and sciatica.

But, "the key finding was that in 30% of the apps, there was no evidence of a health provider input," said Dr. Wallace, who presented her findings in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pain Medicine. In another 30%, the developer was unknown, and researchers couldn’t determine whether a health provider was involved in developing the app. In only 27% of the apps was there a clear involvement of an MD or DO.

Dr. Wallace and her team are working to get the study published and are planning to do a more extensive review of the apps this year. "We’re also planning on connecting some of the studies and looking at what percentages of physicians are recommending these apps and under what circumstances."

Dr. Wallace said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @NaseemSMiller

FORT LAUDERDALE, FLA. – An evaluation of 222 pain-related smartphone apps showed that many were developed without the input of a health professional, some had inaccurate information, and some of their features weren’t as robust as they could be.

"Many of them were giving advice and offering coping strategies, but we don’t know if they’re effective," said Lorraine S. Wallace, Ph.D., who led the study. In addition, the apps could potentially be dangerous for users if the coping strategy – for instance, exercise – isn’t right for them, she said.

Experts have begun studying the safety and efficacy of health-related smartphone apps, many of which are aimed at patients for managing various diseases and conditions.

Dr. Wallace said that, ideally, app developers, physicians, and patients should collaborate to create the apps. "And there needs to be a list of good apps. I always get asked ‘show us a good app,’ so there are definitely some features that we should look at, and that should be driven by health care professionals to determine what a pain app should look like," she said. She advised physicians to be aware of the apps that are currently available to patients.

Dr. Wallace said her study was modeled after a 2011 British study of 111 pain-related apps. The authors of that study also concluded, "Pain apps appear to be able to promise pain relief without any concern for the effectiveness of the product, or for possible adverse effects of product use. In a population often desperate for a solution to distressing and debilitating pain conditions, there is considerable risk of individuals being misled" (J. Telemed. Telecare. 2011;17:308-12).

Dr. Wallace of the department of family medicine and director of research at the Ohio State University in Columbus said that in her evaluation, she didn’t find an ideal pain-related app. "There were certain ones that had better features such as pain diaries or other characteristics, but most of them were not that comprehensive."

Dr. Wallace and her colleagues searched Apple, Android, and Blackberry app stores for the word "pain." They chose 222 apps, and evaluated certain information such as cost, purpose, and key features and documentation of medical professional involvement in design and/or content.

The apps were released between June 2009 and July 2012, with an average cost of $4.99 or less (only seven apps cost more than $9.99). Researchers didn’t purchase any of the apps.

Pain diaries, exercises, and coping strategies were the most common app features. Many apps focused on general pain (93), 57 addressed back and/or neck pain, and 21 dealt with migraine/headache pain. Researchers found one app for muscle pain and one for pain from each of the following conditions: fibromyalgia, menstruation, injury, patellar tendonitis, rheumatism, and sciatica.

But, "the key finding was that in 30% of the apps, there was no evidence of a health provider input," said Dr. Wallace, who presented her findings in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pain Medicine. In another 30%, the developer was unknown, and researchers couldn’t determine whether a health provider was involved in developing the app. In only 27% of the apps was there a clear involvement of an MD or DO.

Dr. Wallace and her team are working to get the study published and are planning to do a more extensive review of the apps this year. "We’re also planning on connecting some of the studies and looking at what percentages of physicians are recommending these apps and under what circumstances."

Dr. Wallace said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @NaseemSMiller

FORT LAUDERDALE, FLA. – An evaluation of 222 pain-related smartphone apps showed that many were developed without the input of a health professional, some had inaccurate information, and some of their features weren’t as robust as they could be.

"Many of them were giving advice and offering coping strategies, but we don’t know if they’re effective," said Lorraine S. Wallace, Ph.D., who led the study. In addition, the apps could potentially be dangerous for users if the coping strategy – for instance, exercise – isn’t right for them, she said.

Experts have begun studying the safety and efficacy of health-related smartphone apps, many of which are aimed at patients for managing various diseases and conditions.

Dr. Wallace said that, ideally, app developers, physicians, and patients should collaborate to create the apps. "And there needs to be a list of good apps. I always get asked ‘show us a good app,’ so there are definitely some features that we should look at, and that should be driven by health care professionals to determine what a pain app should look like," she said. She advised physicians to be aware of the apps that are currently available to patients.

Dr. Wallace said her study was modeled after a 2011 British study of 111 pain-related apps. The authors of that study also concluded, "Pain apps appear to be able to promise pain relief without any concern for the effectiveness of the product, or for possible adverse effects of product use. In a population often desperate for a solution to distressing and debilitating pain conditions, there is considerable risk of individuals being misled" (J. Telemed. Telecare. 2011;17:308-12).

Dr. Wallace of the department of family medicine and director of research at the Ohio State University in Columbus said that in her evaluation, she didn’t find an ideal pain-related app. "There were certain ones that had better features such as pain diaries or other characteristics, but most of them were not that comprehensive."

Dr. Wallace and her colleagues searched Apple, Android, and Blackberry app stores for the word "pain." They chose 222 apps, and evaluated certain information such as cost, purpose, and key features and documentation of medical professional involvement in design and/or content.

The apps were released between June 2009 and July 2012, with an average cost of $4.99 or less (only seven apps cost more than $9.99). Researchers didn’t purchase any of the apps.

Pain diaries, exercises, and coping strategies were the most common app features. Many apps focused on general pain (93), 57 addressed back and/or neck pain, and 21 dealt with migraine/headache pain. Researchers found one app for muscle pain and one for pain from each of the following conditions: fibromyalgia, menstruation, injury, patellar tendonitis, rheumatism, and sciatica.

But, "the key finding was that in 30% of the apps, there was no evidence of a health provider input," said Dr. Wallace, who presented her findings in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pain Medicine. In another 30%, the developer was unknown, and researchers couldn’t determine whether a health provider was involved in developing the app. In only 27% of the apps was there a clear involvement of an MD or DO.

Dr. Wallace and her team are working to get the study published and are planning to do a more extensive review of the apps this year. "We’re also planning on connecting some of the studies and looking at what percentages of physicians are recommending these apps and under what circumstances."

Dr. Wallace said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @NaseemSMiller

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PAIN MEDICINE

Major finding: In more than 60% of the apps, there was no clear indication that a health care professional was involved in the development process.

Data source: Researchers selected 222 apps by searching for the word "pain" in Apple, Android, and Blackberry app stores.

Disclosures: Dr. Wallace said she had no relevant financial disclosures.