User login

VIDEO: Beware of over-relying on MRI findings in axSpA

SAN DIEGO – Healthy individuals can show signs of spinal and pelvic inflammation on MRI, but these scans can be misleading if relied on to make a diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis, according to findings from three separate studies at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“Don’t rely on MRI alone is our message,” said Robert Landewé, MD, PhD, of the University of Amsterdam, who was a coauthor of one of the three studies. “A positive MRI may occur in individuals that are completely healthy. We need to make sure that not too many patients with chronic lower back pain are diagnosed with a disease they don’t have.”

The axial form of spondyloarthritis (axSpA) affects the spinal and pelvic joints of an estimated 1.4% of the U.S. population, and the term encompasses the diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis (0.5% of U.S. population) in which advanced sacroiliitis is seen on conventional radiography, according to the ACR. Axial SpA is particularly common in young people, especially males, in their teens and 20s.

Researchers believe that MRI scans can misleadingly suggest that patients have the condition. “We know that MRI is a sensitive method, but there’s a lack of data regarding its specificity,” Thomas Renson, MD, of Ghent (Belgium) University, said at a press conference during the meeting.

Dr. Landewé led a study that compared MRIs of sacroiliac joints in 47 healthy people, 47 axSpA patients matched for gender and age, 47 chronic back pain patients, 7 women with postpartum back pain, and 24 frequent runners. Positive MRIs were common in the axSpA patients (43 of 47), but they were also found in healthy people (11 of 47), chronic back pain patients (3 of 47), frequent runners (3 of 24), and women with postpartum back pain (4 of 7).

In another study, Dr. Renson and his colleagues sought to understand whether a sustained period of intense physical activity affected spinal findings in 22 healthy military recruits who did not have SpA.

However, there was a statistically significant increase of combined structural and inflammatory lesions (P = .038) from baseline to post training.

The findings underscore “the importance of interpretation of imaging in the right clinical context,” Dr. Renson said, since they point to the possibility of an incorrect diagnosis “even in a young, active population.”

Another study, led by Ulrich Weber, MD, of King Christian 10th Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases, Gråsten, Denmark, sought to understand levels of normal low-grade BME in 20 amateur runners (8 men) and 22 professional Danish hockey players (all men). On average, the researchers found signs of BME in 3.1 sacroiliac joint quadrants in the runners before and after they ran a race. Hockey players were scanned at the end of the competitive season and showed signs of BME in an average of 3.6 sacroiliac joint quadrants.

In an interview, Dr. Landewé said the studies point to how common positive MRIs are in healthy people. “It was far higher than we would have thought 10 years ago,” he said.

Are MRIs still useful then? Dr. Weber said MRI scans are still helpful in axSpA diagnoses even though they have major limitations. “The imaging method is the only one that’s halfway reliable,” he said. “These joints are deep in the body, so we have virtually no clinical ways to diagnose this.”

However, Dr. Landewé said, “you should do it only when you have sufficient suspicion of spondyloarthritis” – due to accompanying conditions such as positive family history, acute anterior uveitis, psoriasis, or peripheral arthritis – and not just when a patient has chronic back pain.

Dr. Renson reported having no relevant disclosures; two of his coauthors reported extensive disclosures. Dr. Weber and his coauthors reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Landewé reported having no relevant disclosures; several of his coauthors reported various disclosures. Funding for the studies was not reported.

SAN DIEGO – Healthy individuals can show signs of spinal and pelvic inflammation on MRI, but these scans can be misleading if relied on to make a diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis, according to findings from three separate studies at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“Don’t rely on MRI alone is our message,” said Robert Landewé, MD, PhD, of the University of Amsterdam, who was a coauthor of one of the three studies. “A positive MRI may occur in individuals that are completely healthy. We need to make sure that not too many patients with chronic lower back pain are diagnosed with a disease they don’t have.”

The axial form of spondyloarthritis (axSpA) affects the spinal and pelvic joints of an estimated 1.4% of the U.S. population, and the term encompasses the diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis (0.5% of U.S. population) in which advanced sacroiliitis is seen on conventional radiography, according to the ACR. Axial SpA is particularly common in young people, especially males, in their teens and 20s.

Researchers believe that MRI scans can misleadingly suggest that patients have the condition. “We know that MRI is a sensitive method, but there’s a lack of data regarding its specificity,” Thomas Renson, MD, of Ghent (Belgium) University, said at a press conference during the meeting.

Dr. Landewé led a study that compared MRIs of sacroiliac joints in 47 healthy people, 47 axSpA patients matched for gender and age, 47 chronic back pain patients, 7 women with postpartum back pain, and 24 frequent runners. Positive MRIs were common in the axSpA patients (43 of 47), but they were also found in healthy people (11 of 47), chronic back pain patients (3 of 47), frequent runners (3 of 24), and women with postpartum back pain (4 of 7).

In another study, Dr. Renson and his colleagues sought to understand whether a sustained period of intense physical activity affected spinal findings in 22 healthy military recruits who did not have SpA.

However, there was a statistically significant increase of combined structural and inflammatory lesions (P = .038) from baseline to post training.

The findings underscore “the importance of interpretation of imaging in the right clinical context,” Dr. Renson said, since they point to the possibility of an incorrect diagnosis “even in a young, active population.”

Another study, led by Ulrich Weber, MD, of King Christian 10th Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases, Gråsten, Denmark, sought to understand levels of normal low-grade BME in 20 amateur runners (8 men) and 22 professional Danish hockey players (all men). On average, the researchers found signs of BME in 3.1 sacroiliac joint quadrants in the runners before and after they ran a race. Hockey players were scanned at the end of the competitive season and showed signs of BME in an average of 3.6 sacroiliac joint quadrants.

In an interview, Dr. Landewé said the studies point to how common positive MRIs are in healthy people. “It was far higher than we would have thought 10 years ago,” he said.

Are MRIs still useful then? Dr. Weber said MRI scans are still helpful in axSpA diagnoses even though they have major limitations. “The imaging method is the only one that’s halfway reliable,” he said. “These joints are deep in the body, so we have virtually no clinical ways to diagnose this.”

However, Dr. Landewé said, “you should do it only when you have sufficient suspicion of spondyloarthritis” – due to accompanying conditions such as positive family history, acute anterior uveitis, psoriasis, or peripheral arthritis – and not just when a patient has chronic back pain.

Dr. Renson reported having no relevant disclosures; two of his coauthors reported extensive disclosures. Dr. Weber and his coauthors reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Landewé reported having no relevant disclosures; several of his coauthors reported various disclosures. Funding for the studies was not reported.

SAN DIEGO – Healthy individuals can show signs of spinal and pelvic inflammation on MRI, but these scans can be misleading if relied on to make a diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis, according to findings from three separate studies at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“Don’t rely on MRI alone is our message,” said Robert Landewé, MD, PhD, of the University of Amsterdam, who was a coauthor of one of the three studies. “A positive MRI may occur in individuals that are completely healthy. We need to make sure that not too many patients with chronic lower back pain are diagnosed with a disease they don’t have.”

The axial form of spondyloarthritis (axSpA) affects the spinal and pelvic joints of an estimated 1.4% of the U.S. population, and the term encompasses the diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis (0.5% of U.S. population) in which advanced sacroiliitis is seen on conventional radiography, according to the ACR. Axial SpA is particularly common in young people, especially males, in their teens and 20s.

Researchers believe that MRI scans can misleadingly suggest that patients have the condition. “We know that MRI is a sensitive method, but there’s a lack of data regarding its specificity,” Thomas Renson, MD, of Ghent (Belgium) University, said at a press conference during the meeting.

Dr. Landewé led a study that compared MRIs of sacroiliac joints in 47 healthy people, 47 axSpA patients matched for gender and age, 47 chronic back pain patients, 7 women with postpartum back pain, and 24 frequent runners. Positive MRIs were common in the axSpA patients (43 of 47), but they were also found in healthy people (11 of 47), chronic back pain patients (3 of 47), frequent runners (3 of 24), and women with postpartum back pain (4 of 7).

In another study, Dr. Renson and his colleagues sought to understand whether a sustained period of intense physical activity affected spinal findings in 22 healthy military recruits who did not have SpA.

However, there was a statistically significant increase of combined structural and inflammatory lesions (P = .038) from baseline to post training.

The findings underscore “the importance of interpretation of imaging in the right clinical context,” Dr. Renson said, since they point to the possibility of an incorrect diagnosis “even in a young, active population.”

Another study, led by Ulrich Weber, MD, of King Christian 10th Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases, Gråsten, Denmark, sought to understand levels of normal low-grade BME in 20 amateur runners (8 men) and 22 professional Danish hockey players (all men). On average, the researchers found signs of BME in 3.1 sacroiliac joint quadrants in the runners before and after they ran a race. Hockey players were scanned at the end of the competitive season and showed signs of BME in an average of 3.6 sacroiliac joint quadrants.

In an interview, Dr. Landewé said the studies point to how common positive MRIs are in healthy people. “It was far higher than we would have thought 10 years ago,” he said.

Are MRIs still useful then? Dr. Weber said MRI scans are still helpful in axSpA diagnoses even though they have major limitations. “The imaging method is the only one that’s halfway reliable,” he said. “These joints are deep in the body, so we have virtually no clinical ways to diagnose this.”

However, Dr. Landewé said, “you should do it only when you have sufficient suspicion of spondyloarthritis” – due to accompanying conditions such as positive family history, acute anterior uveitis, psoriasis, or peripheral arthritis – and not just when a patient has chronic back pain.

Dr. Renson reported having no relevant disclosures; two of his coauthors reported extensive disclosures. Dr. Weber and his coauthors reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Landewé reported having no relevant disclosures; several of his coauthors reported various disclosures. Funding for the studies was not reported.

AT ACR 2017

Blindness linked to HCQ use rare in rheumatic patients

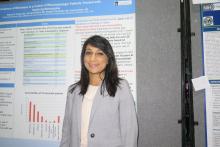

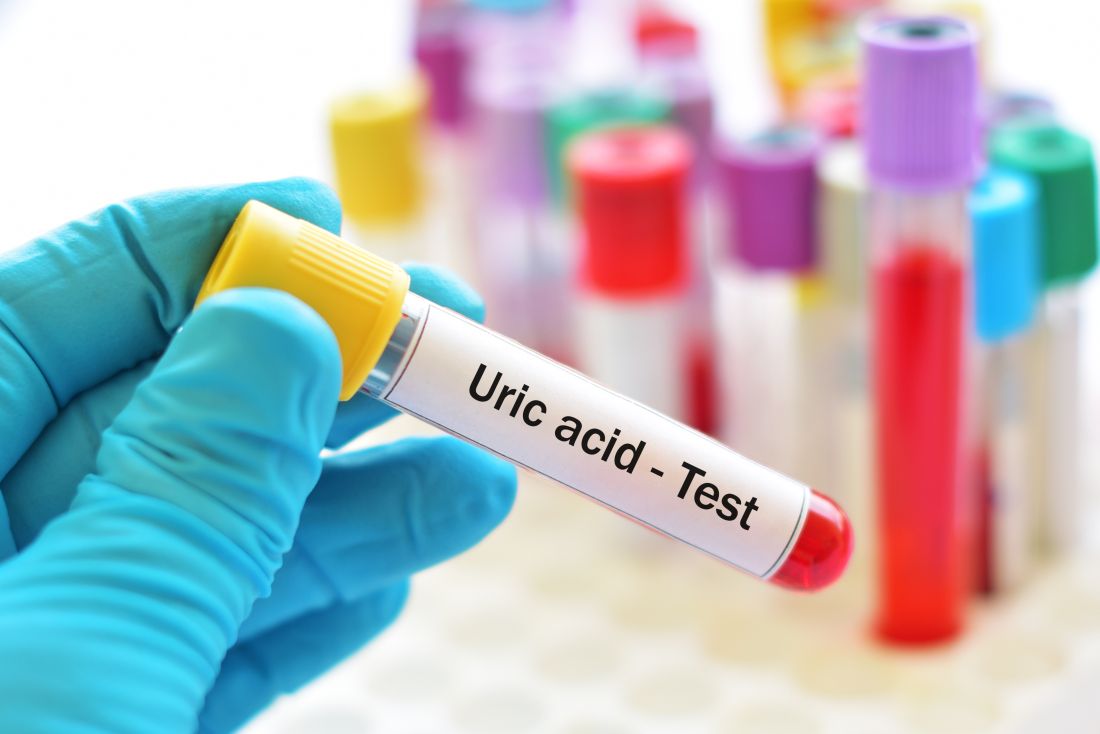

SAN DIEGO – Out of a cohort of nearly 2,900 rheumatic patients, none developed blindness attributable to toxic maculopathy from using hydroxychloroquine, in a single-center retrospective study.

“That’s very reassuring,” lead study author Dilpreet K. Singh, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “It’s still important to be vigilant with our screening and also to take note of the hydroxychloroquine dose that they’re on, because a lot of our patients have been on hydroxychloroquine for 10 or 15 years and there may not have been a dose adjustment. It’s also important to focus on the patients’ comorbidities and get them under better control.”

In an effort to assess the prevalence of blindness in a cohort of rheumatic patients and to identify the characteristics and comorbidities of those with HCQ retinal toxicity, Dr. Singh and her associates retrospectively evaluated 2,898 patients at MetroHealth Medical Center between January 1999 and August of 2017 with diagnoses of rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory polyarthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, subacute cutaneous lupus, and discoid lupus erythematosus who had a prescription written for HCQ.

In all, 31 had a diagnosis of “blindness” or “toxic maculopathy,” and these cases were further assessed for patient demographics, comorbidities, use of tamoxifen, weight and dose at initiation and discontinuation of HCQ, and duration of HCQ. Nearly 70% of these patients had hypertension, about 60% had chronic kidney disease, and 35% had cataracts. The researchers confirmed that in each of the cases the blindness was not caused by HCQ ocular toxicity, but instead by stroke, preexisting macular disease, diabetic retinopathy, hypertensive retinopathy, or cataracts.

Only 3 of the 31 patients were found to have HCQ retinal toxicity, each without blindness or change in vision. Two patients had bull’s-eye maculopathy and one had HCQ toxic maculopathy. Each of the three patients had received HCQ for more than 18 years at doses that ranged from 6.3 to 8.2 mg/kg based on documented weight, and none had functional vision loss at diagnosis.

“It’s reassuring to know that there’s a very small percentage of patients that will have HCQ-related toxicity,” Dr. Singh concluded. “We should also be focusing on the comorbidities [such as] diabetes, hypertension, and stroke-related vision loss that are common in our population of rheumatic patients, because these are contributing to visual impairment and blindness.”

She reported having no disclosures.

[email protected]

SAN DIEGO – Out of a cohort of nearly 2,900 rheumatic patients, none developed blindness attributable to toxic maculopathy from using hydroxychloroquine, in a single-center retrospective study.

“That’s very reassuring,” lead study author Dilpreet K. Singh, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “It’s still important to be vigilant with our screening and also to take note of the hydroxychloroquine dose that they’re on, because a lot of our patients have been on hydroxychloroquine for 10 or 15 years and there may not have been a dose adjustment. It’s also important to focus on the patients’ comorbidities and get them under better control.”

In an effort to assess the prevalence of blindness in a cohort of rheumatic patients and to identify the characteristics and comorbidities of those with HCQ retinal toxicity, Dr. Singh and her associates retrospectively evaluated 2,898 patients at MetroHealth Medical Center between January 1999 and August of 2017 with diagnoses of rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory polyarthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, subacute cutaneous lupus, and discoid lupus erythematosus who had a prescription written for HCQ.

In all, 31 had a diagnosis of “blindness” or “toxic maculopathy,” and these cases were further assessed for patient demographics, comorbidities, use of tamoxifen, weight and dose at initiation and discontinuation of HCQ, and duration of HCQ. Nearly 70% of these patients had hypertension, about 60% had chronic kidney disease, and 35% had cataracts. The researchers confirmed that in each of the cases the blindness was not caused by HCQ ocular toxicity, but instead by stroke, preexisting macular disease, diabetic retinopathy, hypertensive retinopathy, or cataracts.

Only 3 of the 31 patients were found to have HCQ retinal toxicity, each without blindness or change in vision. Two patients had bull’s-eye maculopathy and one had HCQ toxic maculopathy. Each of the three patients had received HCQ for more than 18 years at doses that ranged from 6.3 to 8.2 mg/kg based on documented weight, and none had functional vision loss at diagnosis.

“It’s reassuring to know that there’s a very small percentage of patients that will have HCQ-related toxicity,” Dr. Singh concluded. “We should also be focusing on the comorbidities [such as] diabetes, hypertension, and stroke-related vision loss that are common in our population of rheumatic patients, because these are contributing to visual impairment and blindness.”

She reported having no disclosures.

[email protected]

SAN DIEGO – Out of a cohort of nearly 2,900 rheumatic patients, none developed blindness attributable to toxic maculopathy from using hydroxychloroquine, in a single-center retrospective study.

“That’s very reassuring,” lead study author Dilpreet K. Singh, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “It’s still important to be vigilant with our screening and also to take note of the hydroxychloroquine dose that they’re on, because a lot of our patients have been on hydroxychloroquine for 10 or 15 years and there may not have been a dose adjustment. It’s also important to focus on the patients’ comorbidities and get them under better control.”

In an effort to assess the prevalence of blindness in a cohort of rheumatic patients and to identify the characteristics and comorbidities of those with HCQ retinal toxicity, Dr. Singh and her associates retrospectively evaluated 2,898 patients at MetroHealth Medical Center between January 1999 and August of 2017 with diagnoses of rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory polyarthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, subacute cutaneous lupus, and discoid lupus erythematosus who had a prescription written for HCQ.

In all, 31 had a diagnosis of “blindness” or “toxic maculopathy,” and these cases were further assessed for patient demographics, comorbidities, use of tamoxifen, weight and dose at initiation and discontinuation of HCQ, and duration of HCQ. Nearly 70% of these patients had hypertension, about 60% had chronic kidney disease, and 35% had cataracts. The researchers confirmed that in each of the cases the blindness was not caused by HCQ ocular toxicity, but instead by stroke, preexisting macular disease, diabetic retinopathy, hypertensive retinopathy, or cataracts.

Only 3 of the 31 patients were found to have HCQ retinal toxicity, each without blindness or change in vision. Two patients had bull’s-eye maculopathy and one had HCQ toxic maculopathy. Each of the three patients had received HCQ for more than 18 years at doses that ranged from 6.3 to 8.2 mg/kg based on documented weight, and none had functional vision loss at diagnosis.

“It’s reassuring to know that there’s a very small percentage of patients that will have HCQ-related toxicity,” Dr. Singh concluded. “We should also be focusing on the comorbidities [such as] diabetes, hypertension, and stroke-related vision loss that are common in our population of rheumatic patients, because these are contributing to visual impairment and blindness.”

She reported having no disclosures.

[email protected]

AT ACR 2017

Key clinical point: The incidence of blindness due to hydroxychloroquine toxicity is very low.

Major finding: No patients developed blindness attributable to toxic maculopathy from using hydroxychloroquine.

Study details: A single-center retrospective study of 2,898 rheumatic patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Singh reported having no disclosures.

VIDEO: New PsA guideline expected in 2018

SAN DIEGO – For the first time, a forthcoming evidence-based guideline for the management of psoriatic arthritis recommends tumor necrosis factor inhibitor biologics as first-line therapy.

“Guidelines that have been around for the last several years have been skirting around the fact that there’s really no evidence that methotrexate works for PsA,” Dafna D. Gladman, MD, said during a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “So it’s refreshing and reassuring that when you do an appropriate, evidence-based approach, you finally find the truth in front of you, and you have TNF inhibitors as the first-line treatment. Obviously, they’re not for everybody. There are patients in whom we cannot use TNF inhibitors, either because they don’t like needles, or because they have contraindications to getting these particular needles, but at least we have a recommendation for the use of these drugs as a first-line treatment.”

“At first, I wasn’t a big fan of the idea of the GRADE guidelines because the number of questions blows up so fast, [but] it really makes you focus on what the most common [clinical] settings are,” said another core oversight team member, Alexis Ogdie, MD, a rheumatologist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “These guidelines also reveal the major gap of no head-to-head studies. I think we’ve known that, but this really called that out as important. When we’re making a treatment decision between [drugs] A and B, we need those studies to be able to better understand how to treat our patients, rather than using the data from one trial to make a decision. ... For my patients, I’m excited that I can now use a TNF inhibitor as a first-line agent. When we have patients come in with very severe disease, occasionally they also have severe psoriasis, so we’ve been able to use TNF inhibitors as first-line treatment in some of our patients in Pennsylvania. This differs state by state. But the exciting thing is that they get better so fast and you don’t have to tell them to wait 12 weeks for methotrexate to work.”

The ACR/NPF guideline is currently under peer review and is expected to be published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, Arthritis Care & Research, and the Journal of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis in the spring or summer of 2018. It focuses on common PsA patients, not exceptional cases. It includes recommendations on the management of patients with active PsA that is defined by the patients’ self-report and judged by the examining clinician to be caused by PsA, based on the on the presence of at least one of the following: actively inflamed joints; dactylitis; enthesitis; axial disease; active skin and/or nail involvement; and/or extra-articular manifestations such as uveitis or inflammatory bowel disease. Authors of the guideline considered cost as one of many possible factors affecting the use of the recommendations, but explicit cost-effectiveness analyses were not conducted. Also, since the NPF and the American Academy of Dermatology are concurrently developing a psoriasis treatment guideline, the treatment of skin psoriasis was not included in the guideline.

According to the guideline’s principal investigator Jasvinder Singh, MD, professor of medicine and epidemiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, the guideline will include 80 recommendations, 75 (94%) that are rated as “conditional,” and 5 (6%) that are rated as “strong,” based on the quality of evidence in the existing medical literature. “Most of our treatment guidelines rely on very low-to-moderate quality evidence, which means that there needs to be an active discussion between the physician and the patient with regard to which treatment to choose,” said Dr. Singh, who is also a staff rheumatologist at the Birmingham Veterans Affairs Medical Center and who led development of the 2012 and 2015 ACR treatment guidelines for RA. “When you’re not choosing the preferred treatment, there are defined specific recommendations under which that second treatment may be preferred over the first treatment.”

During a separate session at the meeting, Dr. Singh unveiled a few of the draft recommendations. One calls for using a treat-to-target strategy over not using one. In the setting of immunizing patients who are receiving a biologic, another recommendation calls for clinicians to start the indicated biologic and administer killed vaccines (as indicated) in patients with active PsA rather than delaying the biologic to give the killed vaccines. In addition, delaying the start of the indicated biologic is recommended over not delaying in order to administer a live attenuated vaccine in patients with active PsA. When patients continue to have with active PsA despite being on a TNF inhibitor, the draft guideline recommends switching to a different TNF inhibitor rather than an IL-17 inhibitor, an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor, abatacept (Orencia), tofacitinib (Xeljanz), or adding methotrexate. If PsA is still active, the guideline recommends switching to an IL-17 inhibitor instead of an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor, abatacept, or tofacitinib. If PsA is still active, the guideline recommends switching to an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor over abatacept or tofacitinib.

The guideline also includes suggestions for nonpharmacologic treatments, including recommending low-impact exercise over high-impact exercise, occupational therapy, physical therapy, and weight loss. It also includes a strong recommendation to provide smoking cessation advice to patients.

Dr. Singh acknowledged significant research gaps in the current PsA medical literature, including no head-to-head comparisons of treatments. He said that the field also could benefit from specific studies for enthesitis, axial disease, and arthritis mutilans; randomized trials of nonpharmacologic interventions; more trials of monotherapy vs. combination therapy; vaccination trials for live attenuated vaccines; trials and registry studies of patients with common comorbidities, and studies of NSAIDs and glucocorticoids, to define their role.

Possible topics for future PsA guidelines, he continued, include treatment options for patients for whom biologic medication is not an option; use of therapies in pregnancy and conception; incorporation of high-quality cost or cost-effectiveness analysis into recommendations; and the role of other comorbidities, such as fibromyalgia, hepatitis, depression/anxiety, malignancy, and cardiovascular disease.

“Evidence-based medicine needs to be practiced, even in situations where it’s difficult to get a drug,” Dr. Gladman said. “One of the things we hope will happen in the near future is that companies will start doing head-to-head studies, to help us support evidence-based recommendations in the future.”

None of the speakers reported having relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – For the first time, a forthcoming evidence-based guideline for the management of psoriatic arthritis recommends tumor necrosis factor inhibitor biologics as first-line therapy.

“Guidelines that have been around for the last several years have been skirting around the fact that there’s really no evidence that methotrexate works for PsA,” Dafna D. Gladman, MD, said during a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “So it’s refreshing and reassuring that when you do an appropriate, evidence-based approach, you finally find the truth in front of you, and you have TNF inhibitors as the first-line treatment. Obviously, they’re not for everybody. There are patients in whom we cannot use TNF inhibitors, either because they don’t like needles, or because they have contraindications to getting these particular needles, but at least we have a recommendation for the use of these drugs as a first-line treatment.”

“At first, I wasn’t a big fan of the idea of the GRADE guidelines because the number of questions blows up so fast, [but] it really makes you focus on what the most common [clinical] settings are,” said another core oversight team member, Alexis Ogdie, MD, a rheumatologist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “These guidelines also reveal the major gap of no head-to-head studies. I think we’ve known that, but this really called that out as important. When we’re making a treatment decision between [drugs] A and B, we need those studies to be able to better understand how to treat our patients, rather than using the data from one trial to make a decision. ... For my patients, I’m excited that I can now use a TNF inhibitor as a first-line agent. When we have patients come in with very severe disease, occasionally they also have severe psoriasis, so we’ve been able to use TNF inhibitors as first-line treatment in some of our patients in Pennsylvania. This differs state by state. But the exciting thing is that they get better so fast and you don’t have to tell them to wait 12 weeks for methotrexate to work.”

The ACR/NPF guideline is currently under peer review and is expected to be published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, Arthritis Care & Research, and the Journal of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis in the spring or summer of 2018. It focuses on common PsA patients, not exceptional cases. It includes recommendations on the management of patients with active PsA that is defined by the patients’ self-report and judged by the examining clinician to be caused by PsA, based on the on the presence of at least one of the following: actively inflamed joints; dactylitis; enthesitis; axial disease; active skin and/or nail involvement; and/or extra-articular manifestations such as uveitis or inflammatory bowel disease. Authors of the guideline considered cost as one of many possible factors affecting the use of the recommendations, but explicit cost-effectiveness analyses were not conducted. Also, since the NPF and the American Academy of Dermatology are concurrently developing a psoriasis treatment guideline, the treatment of skin psoriasis was not included in the guideline.

According to the guideline’s principal investigator Jasvinder Singh, MD, professor of medicine and epidemiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, the guideline will include 80 recommendations, 75 (94%) that are rated as “conditional,” and 5 (6%) that are rated as “strong,” based on the quality of evidence in the existing medical literature. “Most of our treatment guidelines rely on very low-to-moderate quality evidence, which means that there needs to be an active discussion between the physician and the patient with regard to which treatment to choose,” said Dr. Singh, who is also a staff rheumatologist at the Birmingham Veterans Affairs Medical Center and who led development of the 2012 and 2015 ACR treatment guidelines for RA. “When you’re not choosing the preferred treatment, there are defined specific recommendations under which that second treatment may be preferred over the first treatment.”

During a separate session at the meeting, Dr. Singh unveiled a few of the draft recommendations. One calls for using a treat-to-target strategy over not using one. In the setting of immunizing patients who are receiving a biologic, another recommendation calls for clinicians to start the indicated biologic and administer killed vaccines (as indicated) in patients with active PsA rather than delaying the biologic to give the killed vaccines. In addition, delaying the start of the indicated biologic is recommended over not delaying in order to administer a live attenuated vaccine in patients with active PsA. When patients continue to have with active PsA despite being on a TNF inhibitor, the draft guideline recommends switching to a different TNF inhibitor rather than an IL-17 inhibitor, an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor, abatacept (Orencia), tofacitinib (Xeljanz), or adding methotrexate. If PsA is still active, the guideline recommends switching to an IL-17 inhibitor instead of an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor, abatacept, or tofacitinib. If PsA is still active, the guideline recommends switching to an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor over abatacept or tofacitinib.

The guideline also includes suggestions for nonpharmacologic treatments, including recommending low-impact exercise over high-impact exercise, occupational therapy, physical therapy, and weight loss. It also includes a strong recommendation to provide smoking cessation advice to patients.

Dr. Singh acknowledged significant research gaps in the current PsA medical literature, including no head-to-head comparisons of treatments. He said that the field also could benefit from specific studies for enthesitis, axial disease, and arthritis mutilans; randomized trials of nonpharmacologic interventions; more trials of monotherapy vs. combination therapy; vaccination trials for live attenuated vaccines; trials and registry studies of patients with common comorbidities, and studies of NSAIDs and glucocorticoids, to define their role.

Possible topics for future PsA guidelines, he continued, include treatment options for patients for whom biologic medication is not an option; use of therapies in pregnancy and conception; incorporation of high-quality cost or cost-effectiveness analysis into recommendations; and the role of other comorbidities, such as fibromyalgia, hepatitis, depression/anxiety, malignancy, and cardiovascular disease.

“Evidence-based medicine needs to be practiced, even in situations where it’s difficult to get a drug,” Dr. Gladman said. “One of the things we hope will happen in the near future is that companies will start doing head-to-head studies, to help us support evidence-based recommendations in the future.”

None of the speakers reported having relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – For the first time, a forthcoming evidence-based guideline for the management of psoriatic arthritis recommends tumor necrosis factor inhibitor biologics as first-line therapy.

“Guidelines that have been around for the last several years have been skirting around the fact that there’s really no evidence that methotrexate works for PsA,” Dafna D. Gladman, MD, said during a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “So it’s refreshing and reassuring that when you do an appropriate, evidence-based approach, you finally find the truth in front of you, and you have TNF inhibitors as the first-line treatment. Obviously, they’re not for everybody. There are patients in whom we cannot use TNF inhibitors, either because they don’t like needles, or because they have contraindications to getting these particular needles, but at least we have a recommendation for the use of these drugs as a first-line treatment.”

“At first, I wasn’t a big fan of the idea of the GRADE guidelines because the number of questions blows up so fast, [but] it really makes you focus on what the most common [clinical] settings are,” said another core oversight team member, Alexis Ogdie, MD, a rheumatologist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “These guidelines also reveal the major gap of no head-to-head studies. I think we’ve known that, but this really called that out as important. When we’re making a treatment decision between [drugs] A and B, we need those studies to be able to better understand how to treat our patients, rather than using the data from one trial to make a decision. ... For my patients, I’m excited that I can now use a TNF inhibitor as a first-line agent. When we have patients come in with very severe disease, occasionally they also have severe psoriasis, so we’ve been able to use TNF inhibitors as first-line treatment in some of our patients in Pennsylvania. This differs state by state. But the exciting thing is that they get better so fast and you don’t have to tell them to wait 12 weeks for methotrexate to work.”

The ACR/NPF guideline is currently under peer review and is expected to be published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, Arthritis Care & Research, and the Journal of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis in the spring or summer of 2018. It focuses on common PsA patients, not exceptional cases. It includes recommendations on the management of patients with active PsA that is defined by the patients’ self-report and judged by the examining clinician to be caused by PsA, based on the on the presence of at least one of the following: actively inflamed joints; dactylitis; enthesitis; axial disease; active skin and/or nail involvement; and/or extra-articular manifestations such as uveitis or inflammatory bowel disease. Authors of the guideline considered cost as one of many possible factors affecting the use of the recommendations, but explicit cost-effectiveness analyses were not conducted. Also, since the NPF and the American Academy of Dermatology are concurrently developing a psoriasis treatment guideline, the treatment of skin psoriasis was not included in the guideline.

According to the guideline’s principal investigator Jasvinder Singh, MD, professor of medicine and epidemiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, the guideline will include 80 recommendations, 75 (94%) that are rated as “conditional,” and 5 (6%) that are rated as “strong,” based on the quality of evidence in the existing medical literature. “Most of our treatment guidelines rely on very low-to-moderate quality evidence, which means that there needs to be an active discussion between the physician and the patient with regard to which treatment to choose,” said Dr. Singh, who is also a staff rheumatologist at the Birmingham Veterans Affairs Medical Center and who led development of the 2012 and 2015 ACR treatment guidelines for RA. “When you’re not choosing the preferred treatment, there are defined specific recommendations under which that second treatment may be preferred over the first treatment.”

During a separate session at the meeting, Dr. Singh unveiled a few of the draft recommendations. One calls for using a treat-to-target strategy over not using one. In the setting of immunizing patients who are receiving a biologic, another recommendation calls for clinicians to start the indicated biologic and administer killed vaccines (as indicated) in patients with active PsA rather than delaying the biologic to give the killed vaccines. In addition, delaying the start of the indicated biologic is recommended over not delaying in order to administer a live attenuated vaccine in patients with active PsA. When patients continue to have with active PsA despite being on a TNF inhibitor, the draft guideline recommends switching to a different TNF inhibitor rather than an IL-17 inhibitor, an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor, abatacept (Orencia), tofacitinib (Xeljanz), or adding methotrexate. If PsA is still active, the guideline recommends switching to an IL-17 inhibitor instead of an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor, abatacept, or tofacitinib. If PsA is still active, the guideline recommends switching to an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor over abatacept or tofacitinib.

The guideline also includes suggestions for nonpharmacologic treatments, including recommending low-impact exercise over high-impact exercise, occupational therapy, physical therapy, and weight loss. It also includes a strong recommendation to provide smoking cessation advice to patients.

Dr. Singh acknowledged significant research gaps in the current PsA medical literature, including no head-to-head comparisons of treatments. He said that the field also could benefit from specific studies for enthesitis, axial disease, and arthritis mutilans; randomized trials of nonpharmacologic interventions; more trials of monotherapy vs. combination therapy; vaccination trials for live attenuated vaccines; trials and registry studies of patients with common comorbidities, and studies of NSAIDs and glucocorticoids, to define their role.

Possible topics for future PsA guidelines, he continued, include treatment options for patients for whom biologic medication is not an option; use of therapies in pregnancy and conception; incorporation of high-quality cost or cost-effectiveness analysis into recommendations; and the role of other comorbidities, such as fibromyalgia, hepatitis, depression/anxiety, malignancy, and cardiovascular disease.

“Evidence-based medicine needs to be practiced, even in situations where it’s difficult to get a drug,” Dr. Gladman said. “One of the things we hope will happen in the near future is that companies will start doing head-to-head studies, to help us support evidence-based recommendations in the future.”

None of the speakers reported having relevant financial disclosures.

AT ACR 2017

Obesity linked to pain, fatigue in SLE

SAN DIEGO – A new study offers a double message about the potential impact of obesity on systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in women: Excess pounds are linked to a higher risk of patient-reported outcomes such as pain and fatigue, and body mass index may be an appropriate tool to study weight issues in this population.

Researchers found “a strong relationship between body composition and worse outcomes,” Sarah Patterson, MD, a fellow in rheumatology at the University of California, San Francisco, and the lead study author, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

For the new study, Dr. Patterson and her colleagues analyzed findings from surveys of 148 participants in the Arthritis Body Composition and Disability study. All participants were women with a verified SLE diagnosis.

About two-thirds of the sample were white, 14% were Asian, and 13% were African American. The average age was 48 years, the average disease duration was 16 years, and 45% took glucocorticoids.

Researchers used two measurements of obesity: BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater and fat mass index (FMI) of 13 kg/m2 or greater.

They calculated FMI with data collected via whole dual x-ray absorptiometry. Of the participants, 32% and 30% met criteria for obesity under FMI and BMI definitions, respectively.

Researchers also collected survey data regarding measurements of disease activity, depressive symptoms, pain and fatigue.

The study authors controlled their results to account for factors such as age, race, and prednisone use. They found that those defined as obese via FMI had more disease activity and depression than did nonobese women: 14.8 versus 11.5, P = .010, on the Systemic Lupus Activity Questionnaire scale, and 19.8 versus 13.1, P = .004, on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale.

On two other scales of pain and fatigue, obese patients scored lower – a sign of worse status – compared with nonobese women: 38.7 versus 44.2, P = .004, on the Short Form 36 (SF-36) Health Survey pain subscale and 39.6 versus 45.2, P = .010, on the SF-36 vitality subscale. The researchers reported similar findings when using BMI to assess obesity.

It’s not clear why obesity and lupus may be linked, Dr. Patterson said, though she noted that inflammation is a shared factor. “People with lupus have arthritis and chronic pain, so there may be this vicious feedback cycle with hindrances to be able to live healthy lifestyles,” she added.

The study has limitations, including that the sample is largely white, while lupus is more common among minority women. In addition, the study does not include underweight patients or track patients over time. “It will be important to look at obesity and patient-reported outcomes to determine whether weight loss results in better outcomes,” Dr. Patterson said.

The study does provide an extra benefit by suggesting that BMI is not an inferior tool to measure the effects of obesity in the SLE population, Dr. Patterson said. BMI has been criticized as a misleading measurement of obesity. But the BMI and FMI measures produced similar results in this study. “That’s really good news in a way for the practicalities of using this information,” she said.

But FMI may still be a better measurement of obesity in the general population, where BMI may be more likely to be thrown off by high muscle mass.

It may seem obvious that obesity is linked to worse lupus outcomes, but rheumatologist Bryant England, MD, of the University of Nebraska, Omaha, said that this research is noteworthy because it highlights the importance of focusing on obesity in the clinic.

Rheumatologists shouldn’t leave obesity to primary care physicians but instead confront it themselves, said Dr. England, who moderated a discussion of new research at an ACR annual meeting press conference. But he cautioned that prudence is especially important when talking about obesity with lupus patients because they may be sensitive about medication-related weight gain.

Dr. Patterson and the other study authors reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. England also reported no relevant disclosures. The study was funded by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

SAN DIEGO – A new study offers a double message about the potential impact of obesity on systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in women: Excess pounds are linked to a higher risk of patient-reported outcomes such as pain and fatigue, and body mass index may be an appropriate tool to study weight issues in this population.

Researchers found “a strong relationship between body composition and worse outcomes,” Sarah Patterson, MD, a fellow in rheumatology at the University of California, San Francisco, and the lead study author, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

For the new study, Dr. Patterson and her colleagues analyzed findings from surveys of 148 participants in the Arthritis Body Composition and Disability study. All participants were women with a verified SLE diagnosis.

About two-thirds of the sample were white, 14% were Asian, and 13% were African American. The average age was 48 years, the average disease duration was 16 years, and 45% took glucocorticoids.

Researchers used two measurements of obesity: BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater and fat mass index (FMI) of 13 kg/m2 or greater.

They calculated FMI with data collected via whole dual x-ray absorptiometry. Of the participants, 32% and 30% met criteria for obesity under FMI and BMI definitions, respectively.

Researchers also collected survey data regarding measurements of disease activity, depressive symptoms, pain and fatigue.

The study authors controlled their results to account for factors such as age, race, and prednisone use. They found that those defined as obese via FMI had more disease activity and depression than did nonobese women: 14.8 versus 11.5, P = .010, on the Systemic Lupus Activity Questionnaire scale, and 19.8 versus 13.1, P = .004, on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale.

On two other scales of pain and fatigue, obese patients scored lower – a sign of worse status – compared with nonobese women: 38.7 versus 44.2, P = .004, on the Short Form 36 (SF-36) Health Survey pain subscale and 39.6 versus 45.2, P = .010, on the SF-36 vitality subscale. The researchers reported similar findings when using BMI to assess obesity.

It’s not clear why obesity and lupus may be linked, Dr. Patterson said, though she noted that inflammation is a shared factor. “People with lupus have arthritis and chronic pain, so there may be this vicious feedback cycle with hindrances to be able to live healthy lifestyles,” she added.

The study has limitations, including that the sample is largely white, while lupus is more common among minority women. In addition, the study does not include underweight patients or track patients over time. “It will be important to look at obesity and patient-reported outcomes to determine whether weight loss results in better outcomes,” Dr. Patterson said.

The study does provide an extra benefit by suggesting that BMI is not an inferior tool to measure the effects of obesity in the SLE population, Dr. Patterson said. BMI has been criticized as a misleading measurement of obesity. But the BMI and FMI measures produced similar results in this study. “That’s really good news in a way for the practicalities of using this information,” she said.

But FMI may still be a better measurement of obesity in the general population, where BMI may be more likely to be thrown off by high muscle mass.

It may seem obvious that obesity is linked to worse lupus outcomes, but rheumatologist Bryant England, MD, of the University of Nebraska, Omaha, said that this research is noteworthy because it highlights the importance of focusing on obesity in the clinic.

Rheumatologists shouldn’t leave obesity to primary care physicians but instead confront it themselves, said Dr. England, who moderated a discussion of new research at an ACR annual meeting press conference. But he cautioned that prudence is especially important when talking about obesity with lupus patients because they may be sensitive about medication-related weight gain.

Dr. Patterson and the other study authors reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. England also reported no relevant disclosures. The study was funded by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

SAN DIEGO – A new study offers a double message about the potential impact of obesity on systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in women: Excess pounds are linked to a higher risk of patient-reported outcomes such as pain and fatigue, and body mass index may be an appropriate tool to study weight issues in this population.

Researchers found “a strong relationship between body composition and worse outcomes,” Sarah Patterson, MD, a fellow in rheumatology at the University of California, San Francisco, and the lead study author, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

For the new study, Dr. Patterson and her colleagues analyzed findings from surveys of 148 participants in the Arthritis Body Composition and Disability study. All participants were women with a verified SLE diagnosis.

About two-thirds of the sample were white, 14% were Asian, and 13% were African American. The average age was 48 years, the average disease duration was 16 years, and 45% took glucocorticoids.

Researchers used two measurements of obesity: BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater and fat mass index (FMI) of 13 kg/m2 or greater.

They calculated FMI with data collected via whole dual x-ray absorptiometry. Of the participants, 32% and 30% met criteria for obesity under FMI and BMI definitions, respectively.

Researchers also collected survey data regarding measurements of disease activity, depressive symptoms, pain and fatigue.

The study authors controlled their results to account for factors such as age, race, and prednisone use. They found that those defined as obese via FMI had more disease activity and depression than did nonobese women: 14.8 versus 11.5, P = .010, on the Systemic Lupus Activity Questionnaire scale, and 19.8 versus 13.1, P = .004, on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale.

On two other scales of pain and fatigue, obese patients scored lower – a sign of worse status – compared with nonobese women: 38.7 versus 44.2, P = .004, on the Short Form 36 (SF-36) Health Survey pain subscale and 39.6 versus 45.2, P = .010, on the SF-36 vitality subscale. The researchers reported similar findings when using BMI to assess obesity.

It’s not clear why obesity and lupus may be linked, Dr. Patterson said, though she noted that inflammation is a shared factor. “People with lupus have arthritis and chronic pain, so there may be this vicious feedback cycle with hindrances to be able to live healthy lifestyles,” she added.

The study has limitations, including that the sample is largely white, while lupus is more common among minority women. In addition, the study does not include underweight patients or track patients over time. “It will be important to look at obesity and patient-reported outcomes to determine whether weight loss results in better outcomes,” Dr. Patterson said.

The study does provide an extra benefit by suggesting that BMI is not an inferior tool to measure the effects of obesity in the SLE population, Dr. Patterson said. BMI has been criticized as a misleading measurement of obesity. But the BMI and FMI measures produced similar results in this study. “That’s really good news in a way for the practicalities of using this information,” she said.

But FMI may still be a better measurement of obesity in the general population, where BMI may be more likely to be thrown off by high muscle mass.

It may seem obvious that obesity is linked to worse lupus outcomes, but rheumatologist Bryant England, MD, of the University of Nebraska, Omaha, said that this research is noteworthy because it highlights the importance of focusing on obesity in the clinic.

Rheumatologists shouldn’t leave obesity to primary care physicians but instead confront it themselves, said Dr. England, who moderated a discussion of new research at an ACR annual meeting press conference. But he cautioned that prudence is especially important when talking about obesity with lupus patients because they may be sensitive about medication-related weight gain.

Dr. Patterson and the other study authors reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. England also reported no relevant disclosures. The study was funded by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

AT ACR 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Obese women with SLE had more disease activity than did nonobese women (14.8 versus 11.5, P = .010).

Data source: An analysis of 148 SLE patients (65% white, mean age 48, about 31% obese) with obesity measured by body mass index or fat mass index.

Disclosures: The study authors reported having no relevant disclosures. The National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases funded the study.

Gout incidence is intertwined with serum urate, but only up to a point

SAN DIEGO – The incidence of gout is strongly linked to patients’ concentration of serum uric acid over time, but even so, less than half of patients with levels of 10 mg/dL or above develop the condition by 15 years, according to the largest individual person-level analysis to examine the relationship.

The incidence of gout rose from about 1% after 15 years in patients with a serum uric acid (sUA) level of less than 6 mg/dL to almost 49% in those with 10 mg/dL or higher in the study, which implies “a long period of hyperuricemia preceding the onset of clinical gout” and also “supports a role for additional factors in the pathogenesis of gout,” Nicola Dalbeth, MD, said in her presentation of the results at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Dr. Dalbeth and her associates found four studies in a search of PubMed and the Database of Genotype and Phenotype from Jan. 1, 1980, to June 11, 2016, that met the inclusion criteria of containing publicly available participant level data, recorded incident gout (via classification criteria, doctor’s diagnosis, or self report of disease), and had a minimum of 3 years of follow-up. The four studies were the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study, the original cohort of the Framingham Heart Study, and the offspring cohort of the Framingham Heart Study, comprising 18,889 individuals who were gout free at the beginning of follow-up, which lasted a mean of 11.2 years.

In all studies combined, the incidence of gout at an sUA level of less than 6 mg/dL steadily increased from 0.21% at 3 years of follow-up to 1.12% at 15 years. In contrast, sUA at 10 mg/dL or higher led to gout in 10.00% at 3 years and in 48.57% at 15 years.

The same general pattern held for the incidence of gout in both men and women, although men had a higher incidence across nearly all sUA concentration ranges.

Female sex provided a 30% reduced risk of gout, and European ethnicity nearly halved the risk for gout, compared with non-Europeans, The risk for gout rose across decades of age, starting at 40-49 years, and also increased significantly for each 1-mg/dL interval of sUA starting at 6 mg/dL.

The study’s conclusions are limited by the use of variable definitions of gout and how it was ascertained. In addition, the study did not analyze other endpoints that are associated with hyperuricemia and may be relevant to discuss in counseling people with elevated sUA levels, such as hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease, Dr. Dalbeth said.

Audience member Daniel H. Solomon, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said after the presentation that it is possible that age might not be independent of sUA level because it’s unknown when patients first had hyperuricemia, and so it could just serve as a marker of the duration of the effect of hyperuricemia. “You showed us that the longer you wait for people who have higher [sUA] levels, the more likely you are to observe gout. So it’s probably some mixture of duration [of hyperuricemia] and age,” he said.

Dr. Dalbeth agreed, saying that it could also help to explain why the incidence of gout is lower at younger ages in women but then subsequently becomes higher.

The Health Research Council of New Zealand supported the research. Dr. Dalbeth reported receiving consulting fees, grants, or speaking fees from Takeda, Horizon, Menarini, AstraZeneca, Ardea Biosciences, Pfizer, and Cymabay, but none are related to this study. Two other authors also had several financial disclosures, but none of the others did.

SAN DIEGO – The incidence of gout is strongly linked to patients’ concentration of serum uric acid over time, but even so, less than half of patients with levels of 10 mg/dL or above develop the condition by 15 years, according to the largest individual person-level analysis to examine the relationship.

The incidence of gout rose from about 1% after 15 years in patients with a serum uric acid (sUA) level of less than 6 mg/dL to almost 49% in those with 10 mg/dL or higher in the study, which implies “a long period of hyperuricemia preceding the onset of clinical gout” and also “supports a role for additional factors in the pathogenesis of gout,” Nicola Dalbeth, MD, said in her presentation of the results at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Dr. Dalbeth and her associates found four studies in a search of PubMed and the Database of Genotype and Phenotype from Jan. 1, 1980, to June 11, 2016, that met the inclusion criteria of containing publicly available participant level data, recorded incident gout (via classification criteria, doctor’s diagnosis, or self report of disease), and had a minimum of 3 years of follow-up. The four studies were the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study, the original cohort of the Framingham Heart Study, and the offspring cohort of the Framingham Heart Study, comprising 18,889 individuals who were gout free at the beginning of follow-up, which lasted a mean of 11.2 years.

In all studies combined, the incidence of gout at an sUA level of less than 6 mg/dL steadily increased from 0.21% at 3 years of follow-up to 1.12% at 15 years. In contrast, sUA at 10 mg/dL or higher led to gout in 10.00% at 3 years and in 48.57% at 15 years.

The same general pattern held for the incidence of gout in both men and women, although men had a higher incidence across nearly all sUA concentration ranges.

Female sex provided a 30% reduced risk of gout, and European ethnicity nearly halved the risk for gout, compared with non-Europeans, The risk for gout rose across decades of age, starting at 40-49 years, and also increased significantly for each 1-mg/dL interval of sUA starting at 6 mg/dL.

The study’s conclusions are limited by the use of variable definitions of gout and how it was ascertained. In addition, the study did not analyze other endpoints that are associated with hyperuricemia and may be relevant to discuss in counseling people with elevated sUA levels, such as hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease, Dr. Dalbeth said.

Audience member Daniel H. Solomon, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said after the presentation that it is possible that age might not be independent of sUA level because it’s unknown when patients first had hyperuricemia, and so it could just serve as a marker of the duration of the effect of hyperuricemia. “You showed us that the longer you wait for people who have higher [sUA] levels, the more likely you are to observe gout. So it’s probably some mixture of duration [of hyperuricemia] and age,” he said.

Dr. Dalbeth agreed, saying that it could also help to explain why the incidence of gout is lower at younger ages in women but then subsequently becomes higher.

The Health Research Council of New Zealand supported the research. Dr. Dalbeth reported receiving consulting fees, grants, or speaking fees from Takeda, Horizon, Menarini, AstraZeneca, Ardea Biosciences, Pfizer, and Cymabay, but none are related to this study. Two other authors also had several financial disclosures, but none of the others did.

SAN DIEGO – The incidence of gout is strongly linked to patients’ concentration of serum uric acid over time, but even so, less than half of patients with levels of 10 mg/dL or above develop the condition by 15 years, according to the largest individual person-level analysis to examine the relationship.

The incidence of gout rose from about 1% after 15 years in patients with a serum uric acid (sUA) level of less than 6 mg/dL to almost 49% in those with 10 mg/dL or higher in the study, which implies “a long period of hyperuricemia preceding the onset of clinical gout” and also “supports a role for additional factors in the pathogenesis of gout,” Nicola Dalbeth, MD, said in her presentation of the results at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Dr. Dalbeth and her associates found four studies in a search of PubMed and the Database of Genotype and Phenotype from Jan. 1, 1980, to June 11, 2016, that met the inclusion criteria of containing publicly available participant level data, recorded incident gout (via classification criteria, doctor’s diagnosis, or self report of disease), and had a minimum of 3 years of follow-up. The four studies were the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study, the original cohort of the Framingham Heart Study, and the offspring cohort of the Framingham Heart Study, comprising 18,889 individuals who were gout free at the beginning of follow-up, which lasted a mean of 11.2 years.

In all studies combined, the incidence of gout at an sUA level of less than 6 mg/dL steadily increased from 0.21% at 3 years of follow-up to 1.12% at 15 years. In contrast, sUA at 10 mg/dL or higher led to gout in 10.00% at 3 years and in 48.57% at 15 years.

The same general pattern held for the incidence of gout in both men and women, although men had a higher incidence across nearly all sUA concentration ranges.

Female sex provided a 30% reduced risk of gout, and European ethnicity nearly halved the risk for gout, compared with non-Europeans, The risk for gout rose across decades of age, starting at 40-49 years, and also increased significantly for each 1-mg/dL interval of sUA starting at 6 mg/dL.

The study’s conclusions are limited by the use of variable definitions of gout and how it was ascertained. In addition, the study did not analyze other endpoints that are associated with hyperuricemia and may be relevant to discuss in counseling people with elevated sUA levels, such as hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease, Dr. Dalbeth said.

Audience member Daniel H. Solomon, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said after the presentation that it is possible that age might not be independent of sUA level because it’s unknown when patients first had hyperuricemia, and so it could just serve as a marker of the duration of the effect of hyperuricemia. “You showed us that the longer you wait for people who have higher [sUA] levels, the more likely you are to observe gout. So it’s probably some mixture of duration [of hyperuricemia] and age,” he said.

Dr. Dalbeth agreed, saying that it could also help to explain why the incidence of gout is lower at younger ages in women but then subsequently becomes higher.

The Health Research Council of New Zealand supported the research. Dr. Dalbeth reported receiving consulting fees, grants, or speaking fees from Takeda, Horizon, Menarini, AstraZeneca, Ardea Biosciences, Pfizer, and Cymabay, but none are related to this study. Two other authors also had several financial disclosures, but none of the others did.

AT ACR 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The incidence of gout rose to about 1% after 15 years in patients with a serum uric acid (sUA) level of less than 6 mg/dL to almost 49% in those with 10 mg/dL or higher.

Data source: An analysis of 18,889 participants in four longitudinal observational cohort studies for whom baseline serum uric acid levels were available.

Disclosures: The Health Research Council of New Zealand supported the research. Dr. Dalbeth reported receiving consulting fees, grants, or speaking fees from Takeda, Horizon, Menarini, AstraZeneca, Ardea Biosciences, Pfizer, and Cymabay, but none are related to this study. Two other authors also had several financial disclosures, but none of the others did.

Use of opioids, SSRIs linked to increased fracture risk in RA

SAN DIEGO – The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and opioids was associated with an increased osteoporotic fracture risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, results from an analysis of national data showed.

“Osteoporotic fractures are one of the important causes of disability, health-related costs, and mortality in RA, with substantially higher complication and mortality rates than the general population,” study author Gulsen Ozen, MD, said in an interview prior to the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “Given the burden of osteoporotic fractures and the suboptimal osteoporosis care, identifying the factors associated with fracture risk in RA patients is of paramount importance.”

During a median follow-up of nearly 6 years, 863 patients (7.8%) sustained osteoporotic fractures. Compared with patients who did not develop fractures, those who did were significantly older, had higher disease duration and activity, glucocorticoid use, comorbidity and FRAX, a fracture risk assessment tool, scores at baseline. After adjusting for sociodemographics, comorbidities, body mass index, fracture risk by FRAX, and RA severity measures, the researchers found a significant risk of osteoporotic fractures with use of opioids of any strength (weak agents, hazard ratio, 1.45; strong agents, HR, 1.79; P less than .001 for both), SSRI use (HR, 1.35; P = .003), and glucocorticoid use of 3 months or longer at a dose of at least 7.5 mg per day (HR, 1.74; P less than .05). Osteoporotic fracture risk increase started even after 1-30 days of opioid use (HR, 1.96; P less than .001), whereas SSRI-associated risk increase started after 3 months of use (HR, 1.42; P = .054). No significant association with fracture risk was observed with the use of other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, statins, antidepressants, proton pump inhibitors, NSAIDs, anticonvulsants, and antipsychotics.

“One of the first surprising findings was that almost 40% of the RA patients older than 40 years of age were at least once exposed to opioid analgesics,” said Dr. Ozen, who is a research fellow in the division of immunology and rheumatology at the medical center. “Another surprising finding was that even very short-term (1-30 days) use of opioids was associated with increased fracture risk.” She went on to note that careful and regular reviewing of patient medications “is an essential part of the RA patient care, as the use of medications not indicated anymore brings harm rather than a benefit. The most well-known example for this is glucocorticoid use. This is valid for all medications, too. Therefore, we hope that our findings provide more awareness about osteoporotic fractures and associated risk factors in RA patients.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its observational design. “Additionally, fracture and the level of the trauma in our cohort were reported by patients,” she said. “Therefore, there might be some misclassification of fractures as osteoporotic fractures. Lastly, we did not have detailed data regarding fall risk, which might explain the associations we observed with opioids and potentially, SSRIs.”

Dr. Ozen reported having no disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and opioids was associated with an increased osteoporotic fracture risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, results from an analysis of national data showed.

“Osteoporotic fractures are one of the important causes of disability, health-related costs, and mortality in RA, with substantially higher complication and mortality rates than the general population,” study author Gulsen Ozen, MD, said in an interview prior to the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “Given the burden of osteoporotic fractures and the suboptimal osteoporosis care, identifying the factors associated with fracture risk in RA patients is of paramount importance.”

During a median follow-up of nearly 6 years, 863 patients (7.8%) sustained osteoporotic fractures. Compared with patients who did not develop fractures, those who did were significantly older, had higher disease duration and activity, glucocorticoid use, comorbidity and FRAX, a fracture risk assessment tool, scores at baseline. After adjusting for sociodemographics, comorbidities, body mass index, fracture risk by FRAX, and RA severity measures, the researchers found a significant risk of osteoporotic fractures with use of opioids of any strength (weak agents, hazard ratio, 1.45; strong agents, HR, 1.79; P less than .001 for both), SSRI use (HR, 1.35; P = .003), and glucocorticoid use of 3 months or longer at a dose of at least 7.5 mg per day (HR, 1.74; P less than .05). Osteoporotic fracture risk increase started even after 1-30 days of opioid use (HR, 1.96; P less than .001), whereas SSRI-associated risk increase started after 3 months of use (HR, 1.42; P = .054). No significant association with fracture risk was observed with the use of other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, statins, antidepressants, proton pump inhibitors, NSAIDs, anticonvulsants, and antipsychotics.

“One of the first surprising findings was that almost 40% of the RA patients older than 40 years of age were at least once exposed to opioid analgesics,” said Dr. Ozen, who is a research fellow in the division of immunology and rheumatology at the medical center. “Another surprising finding was that even very short-term (1-30 days) use of opioids was associated with increased fracture risk.” She went on to note that careful and regular reviewing of patient medications “is an essential part of the RA patient care, as the use of medications not indicated anymore brings harm rather than a benefit. The most well-known example for this is glucocorticoid use. This is valid for all medications, too. Therefore, we hope that our findings provide more awareness about osteoporotic fractures and associated risk factors in RA patients.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its observational design. “Additionally, fracture and the level of the trauma in our cohort were reported by patients,” she said. “Therefore, there might be some misclassification of fractures as osteoporotic fractures. Lastly, we did not have detailed data regarding fall risk, which might explain the associations we observed with opioids and potentially, SSRIs.”

Dr. Ozen reported having no disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and opioids was associated with an increased osteoporotic fracture risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, results from an analysis of national data showed.

“Osteoporotic fractures are one of the important causes of disability, health-related costs, and mortality in RA, with substantially higher complication and mortality rates than the general population,” study author Gulsen Ozen, MD, said in an interview prior to the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “Given the burden of osteoporotic fractures and the suboptimal osteoporosis care, identifying the factors associated with fracture risk in RA patients is of paramount importance.”

During a median follow-up of nearly 6 years, 863 patients (7.8%) sustained osteoporotic fractures. Compared with patients who did not develop fractures, those who did were significantly older, had higher disease duration and activity, glucocorticoid use, comorbidity and FRAX, a fracture risk assessment tool, scores at baseline. After adjusting for sociodemographics, comorbidities, body mass index, fracture risk by FRAX, and RA severity measures, the researchers found a significant risk of osteoporotic fractures with use of opioids of any strength (weak agents, hazard ratio, 1.45; strong agents, HR, 1.79; P less than .001 for both), SSRI use (HR, 1.35; P = .003), and glucocorticoid use of 3 months or longer at a dose of at least 7.5 mg per day (HR, 1.74; P less than .05). Osteoporotic fracture risk increase started even after 1-30 days of opioid use (HR, 1.96; P less than .001), whereas SSRI-associated risk increase started after 3 months of use (HR, 1.42; P = .054). No significant association with fracture risk was observed with the use of other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, statins, antidepressants, proton pump inhibitors, NSAIDs, anticonvulsants, and antipsychotics.

“One of the first surprising findings was that almost 40% of the RA patients older than 40 years of age were at least once exposed to opioid analgesics,” said Dr. Ozen, who is a research fellow in the division of immunology and rheumatology at the medical center. “Another surprising finding was that even very short-term (1-30 days) use of opioids was associated with increased fracture risk.” She went on to note that careful and regular reviewing of patient medications “is an essential part of the RA patient care, as the use of medications not indicated anymore brings harm rather than a benefit. The most well-known example for this is glucocorticoid use. This is valid for all medications, too. Therefore, we hope that our findings provide more awareness about osteoporotic fractures and associated risk factors in RA patients.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its observational design. “Additionally, fracture and the level of the trauma in our cohort were reported by patients,” she said. “Therefore, there might be some misclassification of fractures as osteoporotic fractures. Lastly, we did not have detailed data regarding fall risk, which might explain the associations we observed with opioids and potentially, SSRIs.”

Dr. Ozen reported having no disclosures.

AT ACR 2017

Key clinical point: When managing with opioids, even in the short-term, clinicians should be aware of the fracture risk.

Major finding: In patients with RA, concomitant use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors was associated with an increased risk of osteoporotic fracture (HR, 1.35; P = .003), as was opioid use (HR, 1.45 and HR, 1.79) for weak and strong agents, respectively; P less than .001 for both).

Study details: An observational study of 11,049 patients from the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases.

Disclosures: Dr. Ozen reported having no disclosures.

Legislative landscape affecting rheumatology has potential wins but many challenges

SAN DIEGO – , but ongoing efforts to advocate for the specialty and patients are showing signs of paying off in some areas, Angus Worthing, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Dr. Worthing, who is chair of the ACR’s Government Affairs Committee and a practicing rheumatologist in the Washington area, encouraged rheumatologists to become involved in advocacy efforts and asked members of the audience at the meeting to visit the ACR’s advocacy website to learn how to help.

The ACR supports a group of bills that have been introduced in either the House or Senate that should have an effect on alleviating the projected shortage of rheumatologists across the United States through 2030. These bills will help, although much of the effort to address the shortage and maldistribution of rheumatologists across the United States will “probably be solved at the local level. It’s not going to be a federal solution. It will be relationships and treatment programs between primary care and rheumatology care that are very local,” Dr. Worthing said.

The Conrad State 30 and Physician Access Reauthorization Act (H.R. 2141, S. 898) aims to streamline visas for foreign physicians to practice in underserved areas.

The Resident Physician Shortage Reduction Act of 2017 (H.R. 2267) would increase for the first time since 1997 the number of graduate medical education residency slots in the United States.

The Ensuring Children’s Access to Specialty Care Act of 2017 (S. 989) allows pediatric subspecialists, including pediatric rheumatologists, to get access to the National Health Service Corps loan repayment program when they work in underserved areas.

More recently, in spring 2017 the American Medical Association played a big role in getting the Trump administration to reverse its stance on not allowing premium processing of H1-B visas for professionals such as physicians. If this had gone into effect, all the rheumatology fellows in training who were going to be practicing – some in underserved areas – might have been forced to return to their home country because of a lack of time to get their H1-B visa processed before finishing their fellowship, Dr. Worthing said.

Affordable Care Act (ACA)

- Provide sufficient, affordable, continuous coverage that encourages access to high-quality care for all.

- Prohibit exclusions based on preexisting conditions.

- Allow children to remain on parent’s insurance until age 26 years.

- Remove excessive administrative burdens that take focus away from patient care.

- Cap annual out-of-pocket costs and ban lifetime limits.

- Have affordable premiums, deductibles, and cost sharing.