User login

American Heart Association (AHA): Scientific Sessions 2015

AHA: HDL – the waters grow muddier

ORLANDO – For years, HDL cholesterol was known as “the good cholesterol.” A low level was associated with increased cardiovascular risk. More HDL cholesterol was thought to be cardioprotective, perhaps even capable of offsetting at least some of the risk conferred by a high LDL cholesterol level.

But it turns out that when it comes to HDL cholesterol, more isn’t always better.

A new study utilizing the increasingly popular “big data” analytic approach indicates that the relationship between HDL cholesterol level and mortality isn’t linear. Instead, it’s U-shaped, with both low and high HDL cholesterol levels being associated with significantly increased mortality risk, Dr. Dennis T. Ko reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This is the latest in a string of bad news regarding the former “good cholesterol.” Large, multicenter, randomized trials of niacin and cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitors aimed at boosting HDL cholesterol levels in patients with low HDL cholesterol as a means of reducing cardiovascular risk succeeded in raising HDL cholesterol, but with no impact on major cardiovascular endpoints, noted Dr. Ko of the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences and the University of Toronto.

He presented a population-based study of 631,762 Ontario residents who were free of prior cardiovascular disease and at least 40 years old in 2008. This study group, known as the CANHEART cohort, was formed by combining 17 large regional databases. The advantage of working with such a large study population is that it provides new and statistically powerful insights into the impact of the full range of HDL cholesterol values, not just in terms of cardiovascular events but the full spectrum of disease, Dr. Ko explained. Up until now, the conventional knowledge about HDL cholesterol has been based largely upon relatively small observational studies, such as the Framingham Heart Study; most of those studies didn’t look at noncardiovascular events.

During a mean 4.9 years of follow-up of the CANHEART cohort, 9,339 deaths occurred in men and 8,613 in women. In an analysis adjusted for age, non–HDL cholesterol levels, cardiac risk factors, sex, comorbid conditions, and income, HDL cholesterol levels below the reference range of 41-50 mg/dL in women and 51-60 mg/dL in men were associated with increased risks of mortality from all three causes: cardiovascular, cancer, and other. The lower the HDL cholesterol level, the greater the risks.

As HDL cholesterol groupings moved decile by decile above the reference ranges there was no protective effect seen against cardiovascular or noncardiovascular deaths. Instead, the risk of death due to causes other than heart disease or cancer took a turn upward as HDL cholesterol levels approached the outer end of the bell curve, achieving significance in men with an HDL cholesterol of 71-80 mg/dL and peaking in those with a level greater than 90 mg/dL. In women, the U-shaped curve was shallower, with an increased mortality risk – again, as in men, restricted to causes other than cancer or heart disease – becoming statistically significant only in women with an HDL cholesterol level greater than 90 mg/dL, Dr. Ko continued.

It’s worth noting that men with an HDL cholesterol level of 81 mg/dL or above also showed a trend for increased risks of both cardiovascular and cancer deaths, although this didn’t reach statistical significance.

Patients at the low end of the HDL cholesterol spectrum had an increased prevalence of unhealthy lifestyle, COPD and other comorbid conditions, cardiac risk factors, and low income. In contrast, those with high HDL cholesterol levels were more likely to have a body mass index below 25 kg/m2, engage in 30 minutes or more of brisk walking or other moderate exercise daily, and consume five or more servings of fruits and vegetables daily. So they were, overall, healthier. On the other hand, they were also more likely to be heavy alcohol users as defined by consuming five or more drinks per occasion at least once monthly during the year prior to study enrollment. Alcohol, like physical exercise, is known to boost HDL cholesterol levels.

These CANHEART data and other evidence warrant a reappraisal of HDL cholesterol as a cardiovascular risk/protective factor, according to Dr. Ko.

“HDL is unlikely to represent a cardiovascular-specific risk factor, given similarities in its association with noncardiovascular outcomes,” he observed.

Discussant Jacques Genest concurred.

“Maybe HDL cholesterol mass is the wrong biomarker for HDL function,” opined Dr. Genest, professor of medicine at McGill University in Montreal.

He noted that a causal relationship between HDL cholesterol and cardiovascular risk has been cast into doubt not only by the negative randomized trials of niacin and the CETP inhibitors and the U-shaped mortality curve described by Dr. Ko, but also by randomized Mendelian genetic studies suggesting that genes causing HDL deficiency aren’t linked to increased cardiovascular risk.

It’s likely true that what’s important is not HDL cholesterol levels as measured in conventional lipid panels, but rather HDL function. HDL particles have many beneficial effects: antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, vasodilatory, antiapoptotic, and antithrombotic. A better biomarker – one that reflects these functional benefits – may be cholesterol efflux capacity, as was shown in a recent study by investigators in the Dallas Heart Study (N Engl J Med. 2014; Dec 18;371[25]:2383-93), according to Dr. Genest.

Session cochair Dr. Christie Ballantyne was particularly interested in the 2.8% of CANHEART participants with an HDL cholesterol level greater than 90 mg/dL and their associated increased mortality from causes other than cancer and cardiovascular disease.

“I’ve seen similar data once before, in a Russian cohort. Cold weather and alcohol – I wonder if that’s a factor here. The alcohol exposure we saw in the Russian cohort with the 90 HDL levels was really rather striking. And it wasn’t cardiovascular or cancer mortality that they faced, it was other mortality. So I wonder if it’s not an alcohol-related thing, especially in places where you have long, cold winters,” commented Dr. Ballantyne, professor of medicine and of molecular and human genetics at Baylor College of Medicine and director of the Center for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention at the Methodist Debakey Heart Center in Houston.

Dr. Genest was skeptical.

“I think clinicians would argue that seeing an HDL of 90 would be very unusual in a male even if he drinks like an American at a football game,” the Canadian quipped. “ It’s probable that a genetic predisposition plus heavy alcohol is involved.”

Dr. Ko said he and his coinvestigators are scrutinizing the “other deaths” in the very-high HDL cholesterol subgroup, looking for an increase in deaths due to liver cirrhosis, trauma, and other obvious alcohol-related causes. “We haven’t really found a specific pattern,” according to the physician.

Dr. Ballantyne was undeterred. “It may end up being that the person who drinks heavily has some general health issues where trouble occurs because of alcohol in combination with medications rather than a specifically alcohol-related death,” he advised.

The CANHEART study is sponsored by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Ko reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – For years, HDL cholesterol was known as “the good cholesterol.” A low level was associated with increased cardiovascular risk. More HDL cholesterol was thought to be cardioprotective, perhaps even capable of offsetting at least some of the risk conferred by a high LDL cholesterol level.

But it turns out that when it comes to HDL cholesterol, more isn’t always better.

A new study utilizing the increasingly popular “big data” analytic approach indicates that the relationship between HDL cholesterol level and mortality isn’t linear. Instead, it’s U-shaped, with both low and high HDL cholesterol levels being associated with significantly increased mortality risk, Dr. Dennis T. Ko reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This is the latest in a string of bad news regarding the former “good cholesterol.” Large, multicenter, randomized trials of niacin and cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitors aimed at boosting HDL cholesterol levels in patients with low HDL cholesterol as a means of reducing cardiovascular risk succeeded in raising HDL cholesterol, but with no impact on major cardiovascular endpoints, noted Dr. Ko of the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences and the University of Toronto.

He presented a population-based study of 631,762 Ontario residents who were free of prior cardiovascular disease and at least 40 years old in 2008. This study group, known as the CANHEART cohort, was formed by combining 17 large regional databases. The advantage of working with such a large study population is that it provides new and statistically powerful insights into the impact of the full range of HDL cholesterol values, not just in terms of cardiovascular events but the full spectrum of disease, Dr. Ko explained. Up until now, the conventional knowledge about HDL cholesterol has been based largely upon relatively small observational studies, such as the Framingham Heart Study; most of those studies didn’t look at noncardiovascular events.

During a mean 4.9 years of follow-up of the CANHEART cohort, 9,339 deaths occurred in men and 8,613 in women. In an analysis adjusted for age, non–HDL cholesterol levels, cardiac risk factors, sex, comorbid conditions, and income, HDL cholesterol levels below the reference range of 41-50 mg/dL in women and 51-60 mg/dL in men were associated with increased risks of mortality from all three causes: cardiovascular, cancer, and other. The lower the HDL cholesterol level, the greater the risks.

As HDL cholesterol groupings moved decile by decile above the reference ranges there was no protective effect seen against cardiovascular or noncardiovascular deaths. Instead, the risk of death due to causes other than heart disease or cancer took a turn upward as HDL cholesterol levels approached the outer end of the bell curve, achieving significance in men with an HDL cholesterol of 71-80 mg/dL and peaking in those with a level greater than 90 mg/dL. In women, the U-shaped curve was shallower, with an increased mortality risk – again, as in men, restricted to causes other than cancer or heart disease – becoming statistically significant only in women with an HDL cholesterol level greater than 90 mg/dL, Dr. Ko continued.

It’s worth noting that men with an HDL cholesterol level of 81 mg/dL or above also showed a trend for increased risks of both cardiovascular and cancer deaths, although this didn’t reach statistical significance.

Patients at the low end of the HDL cholesterol spectrum had an increased prevalence of unhealthy lifestyle, COPD and other comorbid conditions, cardiac risk factors, and low income. In contrast, those with high HDL cholesterol levels were more likely to have a body mass index below 25 kg/m2, engage in 30 minutes or more of brisk walking or other moderate exercise daily, and consume five or more servings of fruits and vegetables daily. So they were, overall, healthier. On the other hand, they were also more likely to be heavy alcohol users as defined by consuming five or more drinks per occasion at least once monthly during the year prior to study enrollment. Alcohol, like physical exercise, is known to boost HDL cholesterol levels.

These CANHEART data and other evidence warrant a reappraisal of HDL cholesterol as a cardiovascular risk/protective factor, according to Dr. Ko.

“HDL is unlikely to represent a cardiovascular-specific risk factor, given similarities in its association with noncardiovascular outcomes,” he observed.

Discussant Jacques Genest concurred.

“Maybe HDL cholesterol mass is the wrong biomarker for HDL function,” opined Dr. Genest, professor of medicine at McGill University in Montreal.

He noted that a causal relationship between HDL cholesterol and cardiovascular risk has been cast into doubt not only by the negative randomized trials of niacin and the CETP inhibitors and the U-shaped mortality curve described by Dr. Ko, but also by randomized Mendelian genetic studies suggesting that genes causing HDL deficiency aren’t linked to increased cardiovascular risk.

It’s likely true that what’s important is not HDL cholesterol levels as measured in conventional lipid panels, but rather HDL function. HDL particles have many beneficial effects: antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, vasodilatory, antiapoptotic, and antithrombotic. A better biomarker – one that reflects these functional benefits – may be cholesterol efflux capacity, as was shown in a recent study by investigators in the Dallas Heart Study (N Engl J Med. 2014; Dec 18;371[25]:2383-93), according to Dr. Genest.

Session cochair Dr. Christie Ballantyne was particularly interested in the 2.8% of CANHEART participants with an HDL cholesterol level greater than 90 mg/dL and their associated increased mortality from causes other than cancer and cardiovascular disease.

“I’ve seen similar data once before, in a Russian cohort. Cold weather and alcohol – I wonder if that’s a factor here. The alcohol exposure we saw in the Russian cohort with the 90 HDL levels was really rather striking. And it wasn’t cardiovascular or cancer mortality that they faced, it was other mortality. So I wonder if it’s not an alcohol-related thing, especially in places where you have long, cold winters,” commented Dr. Ballantyne, professor of medicine and of molecular and human genetics at Baylor College of Medicine and director of the Center for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention at the Methodist Debakey Heart Center in Houston.

Dr. Genest was skeptical.

“I think clinicians would argue that seeing an HDL of 90 would be very unusual in a male even if he drinks like an American at a football game,” the Canadian quipped. “ It’s probable that a genetic predisposition plus heavy alcohol is involved.”

Dr. Ko said he and his coinvestigators are scrutinizing the “other deaths” in the very-high HDL cholesterol subgroup, looking for an increase in deaths due to liver cirrhosis, trauma, and other obvious alcohol-related causes. “We haven’t really found a specific pattern,” according to the physician.

Dr. Ballantyne was undeterred. “It may end up being that the person who drinks heavily has some general health issues where trouble occurs because of alcohol in combination with medications rather than a specifically alcohol-related death,” he advised.

The CANHEART study is sponsored by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Ko reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – For years, HDL cholesterol was known as “the good cholesterol.” A low level was associated with increased cardiovascular risk. More HDL cholesterol was thought to be cardioprotective, perhaps even capable of offsetting at least some of the risk conferred by a high LDL cholesterol level.

But it turns out that when it comes to HDL cholesterol, more isn’t always better.

A new study utilizing the increasingly popular “big data” analytic approach indicates that the relationship between HDL cholesterol level and mortality isn’t linear. Instead, it’s U-shaped, with both low and high HDL cholesterol levels being associated with significantly increased mortality risk, Dr. Dennis T. Ko reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This is the latest in a string of bad news regarding the former “good cholesterol.” Large, multicenter, randomized trials of niacin and cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitors aimed at boosting HDL cholesterol levels in patients with low HDL cholesterol as a means of reducing cardiovascular risk succeeded in raising HDL cholesterol, but with no impact on major cardiovascular endpoints, noted Dr. Ko of the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences and the University of Toronto.

He presented a population-based study of 631,762 Ontario residents who were free of prior cardiovascular disease and at least 40 years old in 2008. This study group, known as the CANHEART cohort, was formed by combining 17 large regional databases. The advantage of working with such a large study population is that it provides new and statistically powerful insights into the impact of the full range of HDL cholesterol values, not just in terms of cardiovascular events but the full spectrum of disease, Dr. Ko explained. Up until now, the conventional knowledge about HDL cholesterol has been based largely upon relatively small observational studies, such as the Framingham Heart Study; most of those studies didn’t look at noncardiovascular events.

During a mean 4.9 years of follow-up of the CANHEART cohort, 9,339 deaths occurred in men and 8,613 in women. In an analysis adjusted for age, non–HDL cholesterol levels, cardiac risk factors, sex, comorbid conditions, and income, HDL cholesterol levels below the reference range of 41-50 mg/dL in women and 51-60 mg/dL in men were associated with increased risks of mortality from all three causes: cardiovascular, cancer, and other. The lower the HDL cholesterol level, the greater the risks.

As HDL cholesterol groupings moved decile by decile above the reference ranges there was no protective effect seen against cardiovascular or noncardiovascular deaths. Instead, the risk of death due to causes other than heart disease or cancer took a turn upward as HDL cholesterol levels approached the outer end of the bell curve, achieving significance in men with an HDL cholesterol of 71-80 mg/dL and peaking in those with a level greater than 90 mg/dL. In women, the U-shaped curve was shallower, with an increased mortality risk – again, as in men, restricted to causes other than cancer or heart disease – becoming statistically significant only in women with an HDL cholesterol level greater than 90 mg/dL, Dr. Ko continued.

It’s worth noting that men with an HDL cholesterol level of 81 mg/dL or above also showed a trend for increased risks of both cardiovascular and cancer deaths, although this didn’t reach statistical significance.

Patients at the low end of the HDL cholesterol spectrum had an increased prevalence of unhealthy lifestyle, COPD and other comorbid conditions, cardiac risk factors, and low income. In contrast, those with high HDL cholesterol levels were more likely to have a body mass index below 25 kg/m2, engage in 30 minutes or more of brisk walking or other moderate exercise daily, and consume five or more servings of fruits and vegetables daily. So they were, overall, healthier. On the other hand, they were also more likely to be heavy alcohol users as defined by consuming five or more drinks per occasion at least once monthly during the year prior to study enrollment. Alcohol, like physical exercise, is known to boost HDL cholesterol levels.

These CANHEART data and other evidence warrant a reappraisal of HDL cholesterol as a cardiovascular risk/protective factor, according to Dr. Ko.

“HDL is unlikely to represent a cardiovascular-specific risk factor, given similarities in its association with noncardiovascular outcomes,” he observed.

Discussant Jacques Genest concurred.

“Maybe HDL cholesterol mass is the wrong biomarker for HDL function,” opined Dr. Genest, professor of medicine at McGill University in Montreal.

He noted that a causal relationship between HDL cholesterol and cardiovascular risk has been cast into doubt not only by the negative randomized trials of niacin and the CETP inhibitors and the U-shaped mortality curve described by Dr. Ko, but also by randomized Mendelian genetic studies suggesting that genes causing HDL deficiency aren’t linked to increased cardiovascular risk.

It’s likely true that what’s important is not HDL cholesterol levels as measured in conventional lipid panels, but rather HDL function. HDL particles have many beneficial effects: antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, vasodilatory, antiapoptotic, and antithrombotic. A better biomarker – one that reflects these functional benefits – may be cholesterol efflux capacity, as was shown in a recent study by investigators in the Dallas Heart Study (N Engl J Med. 2014; Dec 18;371[25]:2383-93), according to Dr. Genest.

Session cochair Dr. Christie Ballantyne was particularly interested in the 2.8% of CANHEART participants with an HDL cholesterol level greater than 90 mg/dL and their associated increased mortality from causes other than cancer and cardiovascular disease.

“I’ve seen similar data once before, in a Russian cohort. Cold weather and alcohol – I wonder if that’s a factor here. The alcohol exposure we saw in the Russian cohort with the 90 HDL levels was really rather striking. And it wasn’t cardiovascular or cancer mortality that they faced, it was other mortality. So I wonder if it’s not an alcohol-related thing, especially in places where you have long, cold winters,” commented Dr. Ballantyne, professor of medicine and of molecular and human genetics at Baylor College of Medicine and director of the Center for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention at the Methodist Debakey Heart Center in Houston.

Dr. Genest was skeptical.

“I think clinicians would argue that seeing an HDL of 90 would be very unusual in a male even if he drinks like an American at a football game,” the Canadian quipped. “ It’s probable that a genetic predisposition plus heavy alcohol is involved.”

Dr. Ko said he and his coinvestigators are scrutinizing the “other deaths” in the very-high HDL cholesterol subgroup, looking for an increase in deaths due to liver cirrhosis, trauma, and other obvious alcohol-related causes. “We haven’t really found a specific pattern,” according to the physician.

Dr. Ballantyne was undeterred. “It may end up being that the person who drinks heavily has some general health issues where trouble occurs because of alcohol in combination with medications rather than a specifically alcohol-related death,” he advised.

The CANHEART study is sponsored by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Ko reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Doubt has emerged about the validity of HDL cholesterol as a straightforward cardiovascular risk factor.

Major finding: The relationship between HDL cholesterol and mortality isn’t linear, it’s U-shaped, with increased risk seen at both low and high levels.

Data source: This registry study included 631,762 Ontario adults free of cardiovascular disease at baseline and followed for a mean of 4.9 years.

Disclosures: The study is sponsored by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AHA: Physician awareness of women’s heart risk due for upgrade

ORLANDO – Heart disease in women is not a top-level concern for most primary care physicians or cardiologists, according to a national survey.

Less than two in five (39%) of the surveyed primary care physicians rated heart disease as their top concern in female patients. It ranked third, behind overweight/obesity followed by breast health, even though cardiovascular disease is the No. 1 cause of death for women in the United States, Dr. Holly S. Andersen reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“Cardiovascular disease is the leading health care threat for women, yet public awareness and physician action have stalled, particularly in younger women and among ethnic minorities. Women are less likely to receive evidence-based preventive, diagnostic, and therapeutic strategies for cardiovascular disease,” declared Dr. Andersen, a cardiologist at New York-Presbyterian Hospital.

She presented the results of a survey of 200 primary care physicians and 100 cardiologists, all in practice for 3 or more years. The survey of a nationally representative sample was commissioned by the Women’s Heart Alliance, for which Dr. Andersen serves as scientific adviser.

Primary care physicians’ emphasis on reducing overweight/obesity as a top priority in female patients is actually counterproductive from a cardiovascular risk perspective, Dr. Andersen said. Since sustained weight loss is often a losing battle, she explained, many women who’ve failed to reduce their body weight in response to their physicians’ encouragement simply put off further office visits, and so their other cardiovascular risk factors go unaddressed.

The survey results demonstrate that awareness about heart disease in women is low among both primary care physicians and cardiologists, she observed. Among the key survey findings:

• Under a quarter (22%) of primary care physicians and 42% of cardiologists feel “extremely well prepared” to assess heart disease risk in female patients, while another 42% of primary care physicians and 40% of cardiologists consider themselves “very well prepared.”

• Less than half (44%) of primary care physicians and 53% of cardiologists use the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk assessment calculator introduced in the latest cholesterol management guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (Circulation. 2013 November. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a). Moreover, 31% of primary care physicians and 15% of cardiologists said they’ve never used it. The tool is used to calculate a patient’s estimated 10-year and lifetime risks of ASCVD. Experts consider it a cornerstone of the current guidelines.

• Less than half (49%) of primary care physicians and 59% of cardiologists say they feel their medical school training prepared them to assess female patients’ risk of heart disease.

The survey was done in conjunction with a campaign by the Women’s Heart Alliance to increase physician awareness of women’s cardiovascular risk and to prepare to take action to improve it. The upcoming campaign will promote efforts to educate women about the importance of going to their physicians to find out their personal risk levels.

Most (87%) of the surveyed primary care physicians and 82% of the cardiologists were favorably disposed to the campaign and the notion of physician education programs to address practice gaps in women’s heart risk assessment.

“What’s different about this new effort is that it will give women a single, meaningful action they can take: a routine heart check with a health care professional,” Dr. Andersen said. A key part of this heart check will include use of the ASCVD risk assessment calculator.

“By uniting with health care professionals to encourage women to not only know their numbers but understand what they mean for their heart health, the effort will help women personalize their risk so they can take the steps they need to keep their hearts healthy,” she continued.

The portion of the campaign aimed at exhorting women to visit physicians for a discussion of personal cardiovascular risk will employ as a catchphrase “#getHeartChecked.”

Support for the physician survey was provided by the National Institutes of Health, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, and several foundations. Dr. Andersen reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Heart disease in women is not a top-level concern for most primary care physicians or cardiologists, according to a national survey.

Less than two in five (39%) of the surveyed primary care physicians rated heart disease as their top concern in female patients. It ranked third, behind overweight/obesity followed by breast health, even though cardiovascular disease is the No. 1 cause of death for women in the United States, Dr. Holly S. Andersen reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“Cardiovascular disease is the leading health care threat for women, yet public awareness and physician action have stalled, particularly in younger women and among ethnic minorities. Women are less likely to receive evidence-based preventive, diagnostic, and therapeutic strategies for cardiovascular disease,” declared Dr. Andersen, a cardiologist at New York-Presbyterian Hospital.

She presented the results of a survey of 200 primary care physicians and 100 cardiologists, all in practice for 3 or more years. The survey of a nationally representative sample was commissioned by the Women’s Heart Alliance, for which Dr. Andersen serves as scientific adviser.

Primary care physicians’ emphasis on reducing overweight/obesity as a top priority in female patients is actually counterproductive from a cardiovascular risk perspective, Dr. Andersen said. Since sustained weight loss is often a losing battle, she explained, many women who’ve failed to reduce their body weight in response to their physicians’ encouragement simply put off further office visits, and so their other cardiovascular risk factors go unaddressed.

The survey results demonstrate that awareness about heart disease in women is low among both primary care physicians and cardiologists, she observed. Among the key survey findings:

• Under a quarter (22%) of primary care physicians and 42% of cardiologists feel “extremely well prepared” to assess heart disease risk in female patients, while another 42% of primary care physicians and 40% of cardiologists consider themselves “very well prepared.”

• Less than half (44%) of primary care physicians and 53% of cardiologists use the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk assessment calculator introduced in the latest cholesterol management guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (Circulation. 2013 November. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a). Moreover, 31% of primary care physicians and 15% of cardiologists said they’ve never used it. The tool is used to calculate a patient’s estimated 10-year and lifetime risks of ASCVD. Experts consider it a cornerstone of the current guidelines.

• Less than half (49%) of primary care physicians and 59% of cardiologists say they feel their medical school training prepared them to assess female patients’ risk of heart disease.

The survey was done in conjunction with a campaign by the Women’s Heart Alliance to increase physician awareness of women’s cardiovascular risk and to prepare to take action to improve it. The upcoming campaign will promote efforts to educate women about the importance of going to their physicians to find out their personal risk levels.

Most (87%) of the surveyed primary care physicians and 82% of the cardiologists were favorably disposed to the campaign and the notion of physician education programs to address practice gaps in women’s heart risk assessment.

“What’s different about this new effort is that it will give women a single, meaningful action they can take: a routine heart check with a health care professional,” Dr. Andersen said. A key part of this heart check will include use of the ASCVD risk assessment calculator.

“By uniting with health care professionals to encourage women to not only know their numbers but understand what they mean for their heart health, the effort will help women personalize their risk so they can take the steps they need to keep their hearts healthy,” she continued.

The portion of the campaign aimed at exhorting women to visit physicians for a discussion of personal cardiovascular risk will employ as a catchphrase “#getHeartChecked.”

Support for the physician survey was provided by the National Institutes of Health, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, and several foundations. Dr. Andersen reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Heart disease in women is not a top-level concern for most primary care physicians or cardiologists, according to a national survey.

Less than two in five (39%) of the surveyed primary care physicians rated heart disease as their top concern in female patients. It ranked third, behind overweight/obesity followed by breast health, even though cardiovascular disease is the No. 1 cause of death for women in the United States, Dr. Holly S. Andersen reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“Cardiovascular disease is the leading health care threat for women, yet public awareness and physician action have stalled, particularly in younger women and among ethnic minorities. Women are less likely to receive evidence-based preventive, diagnostic, and therapeutic strategies for cardiovascular disease,” declared Dr. Andersen, a cardiologist at New York-Presbyterian Hospital.

She presented the results of a survey of 200 primary care physicians and 100 cardiologists, all in practice for 3 or more years. The survey of a nationally representative sample was commissioned by the Women’s Heart Alliance, for which Dr. Andersen serves as scientific adviser.

Primary care physicians’ emphasis on reducing overweight/obesity as a top priority in female patients is actually counterproductive from a cardiovascular risk perspective, Dr. Andersen said. Since sustained weight loss is often a losing battle, she explained, many women who’ve failed to reduce their body weight in response to their physicians’ encouragement simply put off further office visits, and so their other cardiovascular risk factors go unaddressed.

The survey results demonstrate that awareness about heart disease in women is low among both primary care physicians and cardiologists, she observed. Among the key survey findings:

• Under a quarter (22%) of primary care physicians and 42% of cardiologists feel “extremely well prepared” to assess heart disease risk in female patients, while another 42% of primary care physicians and 40% of cardiologists consider themselves “very well prepared.”

• Less than half (44%) of primary care physicians and 53% of cardiologists use the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk assessment calculator introduced in the latest cholesterol management guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (Circulation. 2013 November. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a). Moreover, 31% of primary care physicians and 15% of cardiologists said they’ve never used it. The tool is used to calculate a patient’s estimated 10-year and lifetime risks of ASCVD. Experts consider it a cornerstone of the current guidelines.

• Less than half (49%) of primary care physicians and 59% of cardiologists say they feel their medical school training prepared them to assess female patients’ risk of heart disease.

The survey was done in conjunction with a campaign by the Women’s Heart Alliance to increase physician awareness of women’s cardiovascular risk and to prepare to take action to improve it. The upcoming campaign will promote efforts to educate women about the importance of going to their physicians to find out their personal risk levels.

Most (87%) of the surveyed primary care physicians and 82% of the cardiologists were favorably disposed to the campaign and the notion of physician education programs to address practice gaps in women’s heart risk assessment.

“What’s different about this new effort is that it will give women a single, meaningful action they can take: a routine heart check with a health care professional,” Dr. Andersen said. A key part of this heart check will include use of the ASCVD risk assessment calculator.

“By uniting with health care professionals to encourage women to not only know their numbers but understand what they mean for their heart health, the effort will help women personalize their risk so they can take the steps they need to keep their hearts healthy,” she continued.

The portion of the campaign aimed at exhorting women to visit physicians for a discussion of personal cardiovascular risk will employ as a catchphrase “#getHeartChecked.”

Support for the physician survey was provided by the National Institutes of Health, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, and several foundations. Dr. Andersen reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Systematic assessment of heart disease risk in women is underutilized by physicians and will be the focus of a national consumer/physician educational campaign.

Major finding: Forty-four percent of primary care physicians and 53% of cardiologists surveyed used the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk assessment calculator introduced in the current ACC/AHA cholesterol management guidelines.

Data source: Survey of a nationally representative panel of 200 primary care physicians and 100 cardiologists.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, and several foundations supported the survey. Dr. Anderson reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AHA: DAPT score helps decide whether DAPT continues

ORLANDO – The common challenge faced by clinicians in deciding whether or not to continue dual antiplatelet therapy beyond a year in a patient who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention has gotten easier.

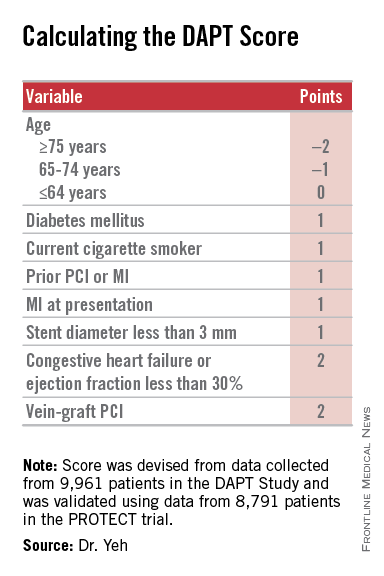

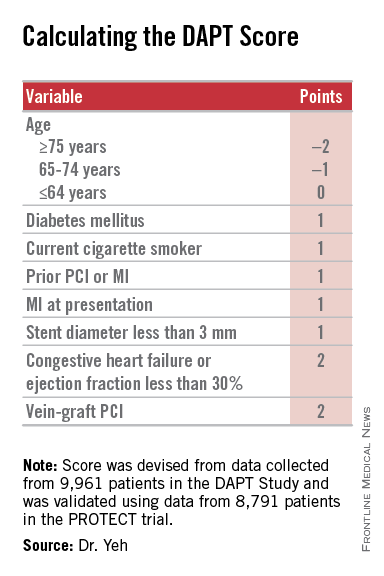

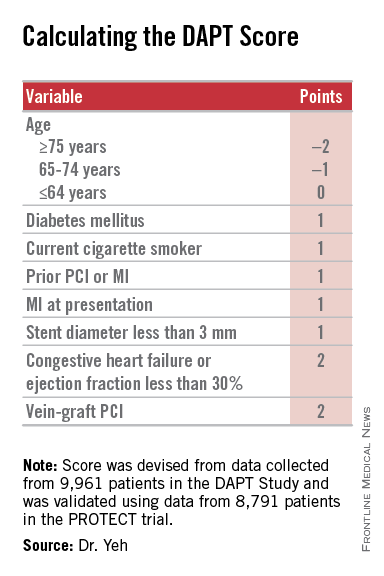

Researchers have devised a simple, eight-element scoring system using information already available in a patient’s records to help determine whether an individual patient will be more likely to benefit from continuing or stopping dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT).

“The DAPT score may help clinicians decide who should and who should not be treated with extended DAPT,” Dr. Robert W. Yeh said at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

“This is a step forward for an issue we deal with daily, balancing an individual patient’s risk from ischemia and bleeding,” commented Dr. Alice Jacobs, professor of medicine at Boston University and director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory and interventional cardiology at Boston Medical Center.

Dr. Yeh and his associates devised the DAPT score from the data collected in the DAPT study, which enrolled more than 25,000 patients and randomized about 10,000 to test whether patients fared better by stopping or continuing DAPT after completing their initial year of DAPT following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The DAPT study results showed that after 18 additional months, continuing DAPT cut the rate of definite or probable stent thrombosis by 1 percentage point and the combined rate of death, MI, or stroke by 1.6 percentage points, both statistically significant differences, compared with patients randomized to treatment with aspirin plus placebo. The results also showed that continued DAPT increased GUSTO moderate or severe bleeding events by 1 percentage point, compared with the control patients (N Engl J Med. 2014 Dec 4;371[23]:2155-66).

The researchers used data collected in the DAPT study to build risk models using patient- and procedure-specific variables that predicted the ischemic and bleeding outcomes, and then combined the two into a single model. That meant abandoning some variables that had significant impact on both outcomes.

The result was a scoring system that includes eight variables that result in a score that ranges from –2 to 9. The analysis showed that a score of 1 or less identified patients for whom the risk for bleeding outweighs their potential gain by avoiding an ischemic event by about 2.5-fold, and hence likely would fare better by stopping DAPT. A score of 2 or higher flagged patients who benefited about eightfold more from avoided ischemic events, compared with their risk for a moderate or severe bleed.

Patient scores showed a classic bell-shaped curve, with roughly a quarter of the DAPT study patients having a score of 1 and about a quarter with a score of 2, about 16% had a score of 0 and about 16% had a score of 3, and about 8% had a score of –1 or –2, while about 9% had a score of 4 or more.

The investigators validated the scoring system using data collected in the PROTECT trial, which included 8,791 patients who underwent PCI during 2007-2008. Dr. Yeh acknowledged that the discrimination strength of the models he and his associated developed was “modest,” but added that its efficacy was greater than what has been shown in validation cohorts for the commonly used CH2ADS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scoring systems.

Dr. Yeh stressed that using the DAPT score “cannot trump clinical judgment.” He suggested that a clinician use the score to help facilitate a conversation with a PCI patient when the time comes to decide whether or not to continue DAPT beyond 1 year.

Other factors that could influence the decision include the length of the stented coronary lesions or prior radiation exposure to the patient’s coronary arteries, said Dr. Laura Mauri, who led the DAPT study and collaborated on developing the DAPT score. “It requires judgment to decide [on whether to continue DAPT] for patients who are on the borderline” for risk and benefit. “This gives patients a way to better understand what they might gain or lose” by continuing treatment. Without the quantification that the DAPT score provides, the balance of risk and benefit “is somewhat nebulous,” said Dr. Mauri, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Clinical Biometrics in the division of cardiovascular medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The investigators who ran the DAPT study realized several years before the study finished that development of the DAPT score was a critical part of applying the findings from the study into clinical practice, she said in an interview.

Dr. Yeh cautioned that the score is only appropriate for patients who match those enrolled into the DAPT study: patients who went through their first year post PCI on DAPT without having any ischemic or bleeding complications. For these patients, “we feel the DAPT score is incredibly valuable,” said Dr. Yeh, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. He and his associates are now using data from the DAPT study to model bleeding and ischemia risks during the first year following PCI to try to come up with risk models that can address DAPT use during this period.

Dr. Yeh and Dr. Mauri have placed a link to the electronic DAPT score calculator on the website for the DAPT study (www.daptstudy.org), and Dr. Yeh said that an app version will soon become available. Interventionalists in the programs that Dr. Yeh and Mauri are affiliated with have recently begun using the DAPT score calculator in their routine practice, Dr. Yeh said.

The DAPT study received funding from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Medtronic, Bristol-Myers Squib-Sanofi, Eli Lilly, and Daiichi Sankyo. Derivation of the DAPT score was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Yeh has received honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Merck. Dr. Jacobs had no disclosures. Dr. Mauri has been a consultant to Biotronik, Medtronic, and St. Jude and has received research funding from several companies.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The DAPT score is a clever and innovative idea. It is a major step forward in helping clinicians decide which patients should continue dual antiplatelet therapy after safely completing a year on this therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention. The DAPT score was data driven and provides a tool to help personalize decision making with a simple, practical solution to a common clinical dilemma. It’s a welcome addition to our decision-making process.

The competing risks from bleeding events caused by continued dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) beyond 1 year and ischemic events caused by stopping DAPT creates difficulty in determining whether or not to continue or stop DAPT for an individual patient. The DAPT score helps make that decision.

|

| Mitchel L. Zoler/Frontline Medical News Dr. James de Lemos |

The analysis performed by Dr. Yeh and his associates produced a clear and convincing result. The primary caveat is that it is only applicable to patients who entered the randomized phase of the DAPT study, specifically patients who underwent a full first year of DAPT treatment following PCI without an ischemic or major bleeding event. I would like to see replication of the score’s validation in an additional data set, although few data sets exist that are suitable for such replication. Although the discrimination produced by the DAPT score is moderate, it compares favorably with other widely used clinical decision scores such as the CHA2ADS2-VASc.

The added decision-making ability facilitated by this score revises my interpretation of the results from the DAPT study. When the results of the trial appeared in 2014, I considered the outcome null because of the problem it highlighted in balancing the competing risks of ischemic and bleeding events when deciding about continuing DAPT beyond 1 year. The DAPT score helps produce a much clearer risk versus benefit decision for a sizable subset of patients who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention.

Dr. James de Lemos is a professor of medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and chief of the cardiology service at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas. He has received honoraria from Novo Nordisk and St. Jude and research funding from Roche Diagnostics and Abbott Diagnostics. He made these comments as the designated discussant for Dr. Yeh’s report.

The DAPT score is a clever and innovative idea. It is a major step forward in helping clinicians decide which patients should continue dual antiplatelet therapy after safely completing a year on this therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention. The DAPT score was data driven and provides a tool to help personalize decision making with a simple, practical solution to a common clinical dilemma. It’s a welcome addition to our decision-making process.

The competing risks from bleeding events caused by continued dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) beyond 1 year and ischemic events caused by stopping DAPT creates difficulty in determining whether or not to continue or stop DAPT for an individual patient. The DAPT score helps make that decision.

|

| Mitchel L. Zoler/Frontline Medical News Dr. James de Lemos |

The analysis performed by Dr. Yeh and his associates produced a clear and convincing result. The primary caveat is that it is only applicable to patients who entered the randomized phase of the DAPT study, specifically patients who underwent a full first year of DAPT treatment following PCI without an ischemic or major bleeding event. I would like to see replication of the score’s validation in an additional data set, although few data sets exist that are suitable for such replication. Although the discrimination produced by the DAPT score is moderate, it compares favorably with other widely used clinical decision scores such as the CHA2ADS2-VASc.

The added decision-making ability facilitated by this score revises my interpretation of the results from the DAPT study. When the results of the trial appeared in 2014, I considered the outcome null because of the problem it highlighted in balancing the competing risks of ischemic and bleeding events when deciding about continuing DAPT beyond 1 year. The DAPT score helps produce a much clearer risk versus benefit decision for a sizable subset of patients who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention.

Dr. James de Lemos is a professor of medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and chief of the cardiology service at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas. He has received honoraria from Novo Nordisk and St. Jude and research funding from Roche Diagnostics and Abbott Diagnostics. He made these comments as the designated discussant for Dr. Yeh’s report.

The DAPT score is a clever and innovative idea. It is a major step forward in helping clinicians decide which patients should continue dual antiplatelet therapy after safely completing a year on this therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention. The DAPT score was data driven and provides a tool to help personalize decision making with a simple, practical solution to a common clinical dilemma. It’s a welcome addition to our decision-making process.

The competing risks from bleeding events caused by continued dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) beyond 1 year and ischemic events caused by stopping DAPT creates difficulty in determining whether or not to continue or stop DAPT for an individual patient. The DAPT score helps make that decision.

|

| Mitchel L. Zoler/Frontline Medical News Dr. James de Lemos |

The analysis performed by Dr. Yeh and his associates produced a clear and convincing result. The primary caveat is that it is only applicable to patients who entered the randomized phase of the DAPT study, specifically patients who underwent a full first year of DAPT treatment following PCI without an ischemic or major bleeding event. I would like to see replication of the score’s validation in an additional data set, although few data sets exist that are suitable for such replication. Although the discrimination produced by the DAPT score is moderate, it compares favorably with other widely used clinical decision scores such as the CHA2ADS2-VASc.

The added decision-making ability facilitated by this score revises my interpretation of the results from the DAPT study. When the results of the trial appeared in 2014, I considered the outcome null because of the problem it highlighted in balancing the competing risks of ischemic and bleeding events when deciding about continuing DAPT beyond 1 year. The DAPT score helps produce a much clearer risk versus benefit decision for a sizable subset of patients who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention.

Dr. James de Lemos is a professor of medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and chief of the cardiology service at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas. He has received honoraria from Novo Nordisk and St. Jude and research funding from Roche Diagnostics and Abbott Diagnostics. He made these comments as the designated discussant for Dr. Yeh’s report.

ORLANDO – The common challenge faced by clinicians in deciding whether or not to continue dual antiplatelet therapy beyond a year in a patient who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention has gotten easier.

Researchers have devised a simple, eight-element scoring system using information already available in a patient’s records to help determine whether an individual patient will be more likely to benefit from continuing or stopping dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT).

“The DAPT score may help clinicians decide who should and who should not be treated with extended DAPT,” Dr. Robert W. Yeh said at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

“This is a step forward for an issue we deal with daily, balancing an individual patient’s risk from ischemia and bleeding,” commented Dr. Alice Jacobs, professor of medicine at Boston University and director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory and interventional cardiology at Boston Medical Center.

Dr. Yeh and his associates devised the DAPT score from the data collected in the DAPT study, which enrolled more than 25,000 patients and randomized about 10,000 to test whether patients fared better by stopping or continuing DAPT after completing their initial year of DAPT following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The DAPT study results showed that after 18 additional months, continuing DAPT cut the rate of definite or probable stent thrombosis by 1 percentage point and the combined rate of death, MI, or stroke by 1.6 percentage points, both statistically significant differences, compared with patients randomized to treatment with aspirin plus placebo. The results also showed that continued DAPT increased GUSTO moderate or severe bleeding events by 1 percentage point, compared with the control patients (N Engl J Med. 2014 Dec 4;371[23]:2155-66).

The researchers used data collected in the DAPT study to build risk models using patient- and procedure-specific variables that predicted the ischemic and bleeding outcomes, and then combined the two into a single model. That meant abandoning some variables that had significant impact on both outcomes.

The result was a scoring system that includes eight variables that result in a score that ranges from –2 to 9. The analysis showed that a score of 1 or less identified patients for whom the risk for bleeding outweighs their potential gain by avoiding an ischemic event by about 2.5-fold, and hence likely would fare better by stopping DAPT. A score of 2 or higher flagged patients who benefited about eightfold more from avoided ischemic events, compared with their risk for a moderate or severe bleed.

Patient scores showed a classic bell-shaped curve, with roughly a quarter of the DAPT study patients having a score of 1 and about a quarter with a score of 2, about 16% had a score of 0 and about 16% had a score of 3, and about 8% had a score of –1 or –2, while about 9% had a score of 4 or more.

The investigators validated the scoring system using data collected in the PROTECT trial, which included 8,791 patients who underwent PCI during 2007-2008. Dr. Yeh acknowledged that the discrimination strength of the models he and his associated developed was “modest,” but added that its efficacy was greater than what has been shown in validation cohorts for the commonly used CH2ADS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scoring systems.

Dr. Yeh stressed that using the DAPT score “cannot trump clinical judgment.” He suggested that a clinician use the score to help facilitate a conversation with a PCI patient when the time comes to decide whether or not to continue DAPT beyond 1 year.

Other factors that could influence the decision include the length of the stented coronary lesions or prior radiation exposure to the patient’s coronary arteries, said Dr. Laura Mauri, who led the DAPT study and collaborated on developing the DAPT score. “It requires judgment to decide [on whether to continue DAPT] for patients who are on the borderline” for risk and benefit. “This gives patients a way to better understand what they might gain or lose” by continuing treatment. Without the quantification that the DAPT score provides, the balance of risk and benefit “is somewhat nebulous,” said Dr. Mauri, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Clinical Biometrics in the division of cardiovascular medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The investigators who ran the DAPT study realized several years before the study finished that development of the DAPT score was a critical part of applying the findings from the study into clinical practice, she said in an interview.

Dr. Yeh cautioned that the score is only appropriate for patients who match those enrolled into the DAPT study: patients who went through their first year post PCI on DAPT without having any ischemic or bleeding complications. For these patients, “we feel the DAPT score is incredibly valuable,” said Dr. Yeh, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. He and his associates are now using data from the DAPT study to model bleeding and ischemia risks during the first year following PCI to try to come up with risk models that can address DAPT use during this period.

Dr. Yeh and Dr. Mauri have placed a link to the electronic DAPT score calculator on the website for the DAPT study (www.daptstudy.org), and Dr. Yeh said that an app version will soon become available. Interventionalists in the programs that Dr. Yeh and Mauri are affiliated with have recently begun using the DAPT score calculator in their routine practice, Dr. Yeh said.

The DAPT study received funding from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Medtronic, Bristol-Myers Squib-Sanofi, Eli Lilly, and Daiichi Sankyo. Derivation of the DAPT score was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Yeh has received honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Merck. Dr. Jacobs had no disclosures. Dr. Mauri has been a consultant to Biotronik, Medtronic, and St. Jude and has received research funding from several companies.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – The common challenge faced by clinicians in deciding whether or not to continue dual antiplatelet therapy beyond a year in a patient who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention has gotten easier.

Researchers have devised a simple, eight-element scoring system using information already available in a patient’s records to help determine whether an individual patient will be more likely to benefit from continuing or stopping dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT).

“The DAPT score may help clinicians decide who should and who should not be treated with extended DAPT,” Dr. Robert W. Yeh said at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

“This is a step forward for an issue we deal with daily, balancing an individual patient’s risk from ischemia and bleeding,” commented Dr. Alice Jacobs, professor of medicine at Boston University and director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory and interventional cardiology at Boston Medical Center.

Dr. Yeh and his associates devised the DAPT score from the data collected in the DAPT study, which enrolled more than 25,000 patients and randomized about 10,000 to test whether patients fared better by stopping or continuing DAPT after completing their initial year of DAPT following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The DAPT study results showed that after 18 additional months, continuing DAPT cut the rate of definite or probable stent thrombosis by 1 percentage point and the combined rate of death, MI, or stroke by 1.6 percentage points, both statistically significant differences, compared with patients randomized to treatment with aspirin plus placebo. The results also showed that continued DAPT increased GUSTO moderate or severe bleeding events by 1 percentage point, compared with the control patients (N Engl J Med. 2014 Dec 4;371[23]:2155-66).

The researchers used data collected in the DAPT study to build risk models using patient- and procedure-specific variables that predicted the ischemic and bleeding outcomes, and then combined the two into a single model. That meant abandoning some variables that had significant impact on both outcomes.

The result was a scoring system that includes eight variables that result in a score that ranges from –2 to 9. The analysis showed that a score of 1 or less identified patients for whom the risk for bleeding outweighs their potential gain by avoiding an ischemic event by about 2.5-fold, and hence likely would fare better by stopping DAPT. A score of 2 or higher flagged patients who benefited about eightfold more from avoided ischemic events, compared with their risk for a moderate or severe bleed.

Patient scores showed a classic bell-shaped curve, with roughly a quarter of the DAPT study patients having a score of 1 and about a quarter with a score of 2, about 16% had a score of 0 and about 16% had a score of 3, and about 8% had a score of –1 or –2, while about 9% had a score of 4 or more.

The investigators validated the scoring system using data collected in the PROTECT trial, which included 8,791 patients who underwent PCI during 2007-2008. Dr. Yeh acknowledged that the discrimination strength of the models he and his associated developed was “modest,” but added that its efficacy was greater than what has been shown in validation cohorts for the commonly used CH2ADS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scoring systems.

Dr. Yeh stressed that using the DAPT score “cannot trump clinical judgment.” He suggested that a clinician use the score to help facilitate a conversation with a PCI patient when the time comes to decide whether or not to continue DAPT beyond 1 year.

Other factors that could influence the decision include the length of the stented coronary lesions or prior radiation exposure to the patient’s coronary arteries, said Dr. Laura Mauri, who led the DAPT study and collaborated on developing the DAPT score. “It requires judgment to decide [on whether to continue DAPT] for patients who are on the borderline” for risk and benefit. “This gives patients a way to better understand what they might gain or lose” by continuing treatment. Without the quantification that the DAPT score provides, the balance of risk and benefit “is somewhat nebulous,” said Dr. Mauri, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Clinical Biometrics in the division of cardiovascular medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The investigators who ran the DAPT study realized several years before the study finished that development of the DAPT score was a critical part of applying the findings from the study into clinical practice, she said in an interview.

Dr. Yeh cautioned that the score is only appropriate for patients who match those enrolled into the DAPT study: patients who went through their first year post PCI on DAPT without having any ischemic or bleeding complications. For these patients, “we feel the DAPT score is incredibly valuable,” said Dr. Yeh, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. He and his associates are now using data from the DAPT study to model bleeding and ischemia risks during the first year following PCI to try to come up with risk models that can address DAPT use during this period.

Dr. Yeh and Dr. Mauri have placed a link to the electronic DAPT score calculator on the website for the DAPT study (www.daptstudy.org), and Dr. Yeh said that an app version will soon become available. Interventionalists in the programs that Dr. Yeh and Mauri are affiliated with have recently begun using the DAPT score calculator in their routine practice, Dr. Yeh said.

The DAPT study received funding from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Medtronic, Bristol-Myers Squib-Sanofi, Eli Lilly, and Daiichi Sankyo. Derivation of the DAPT score was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Yeh has received honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Merck. Dr. Jacobs had no disclosures. Dr. Mauri has been a consultant to Biotronik, Medtronic, and St. Jude and has received research funding from several companies.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: A year after percutaneous coronary intervention, the DAPT score helps clinicians decide whether to continue dual antiplatelet therapy.

Major finding: DAPT scores of 1 or less were linked with a 2.5-fold higher risk of bleeding than ischemic events prevented by continued DAPT; scores of 2 or more were linked with an eightfold increased rate of ischemic events prevented, compared with bleeding events triggered.

Data source: The DAPT study, a multicenter, international, randomized trial that enrolled 25,682 patients.

Disclosures: The DAPT study received funding from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Medtronic, Bristol-Myers Squibb-Sanofi, Eli Lilly, and Daiichi Sankyo. Derivation of the DAPT score was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Yeh has received honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Merck.

ACC/AHA guidelines upgrade multivessel PCI, downgrade thrombectomy

ORLANDO – Two guideline panels jointly upgraded percutaneous coronary interventions in noninfarct coronary arteries in patients with a recent MI, and downgraded manual aspiration thrombectomy in acute MI patients.

The panels, organized by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, cover, respectively, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and ST-elevation MI (STEMI).

The revised guidance on percutaneous coronary intervention for multivessel coronary disease affects roughly half the patients with an acute ST-elevation MI, those who have significant stenoses in noninfarct coronaries. The 2011 guidelines from the PCI panel (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011 Dec;58[24]:e44-122) and the 2013 guidelines from the STEMI committee (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Jan;61[4]:e78-140) only endorsed revascularization of stenotic, noninfarct arteries in patients with cardiogenic shock or severe heart failure. Multivessel PCI for patients without hemodynamic compromise at the time of primary PCI was deemed a class III indication, “thought to confer harm,” based on the results of several observational studies, Dr. Patrick T. O’Gara said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

After the 2013 STEMI guidelines came out, results from four studies showed either benefit or no harm from multivessel PCI in patients with appropriate anatomy performed either at the time of primary PCI or as a scheduled, staged procedure soon after primary PCI, said Dr. O’Gara, professor and director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Three of the four studies, PRAMI (N Engl J Med. 2013 Sept 19;369[12]:1115-23), CvLPRIT (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 March;65[10]:963-72), and DANAMI-3–PRIMULTI (Lancet. 2015 Aug 15;386[9994]:665-71), are published, while results from the fourth, PRAGUE-13, came out in a meeting report this year but as of mid-November had not been published.

Based on these data the two committees reset PCI of noninfarct arteries as a class IIb recommendation that “could be considered” in selected STEMI patients with multivessel disease who are hemodynamically stable.

The guidelines further said that “insufficient data exist to inform a recommendation” about the optimal time for this multivessel PCI, which could be coincident with primary PCI or 2 days, 3 days, a week, or even later after initial PCI, said Dr. O’Gara. “The writing committees do not advocate for routine use of multivessel PCI; clinical judgment is obviously needed,” he cautioned.

The two committees also reassessed manual aspiration thrombectomy during primary PCI for STEMI, which until now has been a class IIa recommendation, “reasonable” for STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI. But based on the neutral results for thrombectomy in the recent findings from the two largest randomized trials of thrombectomy, TOTAL (N Engl J Med. 2015 April 9;372[15]:1389-98) and TASTE (N Engl J Med. 2013 Oct 24;369[17]:1587-97), as well as a recent, 17-trial meta-analysis, the revised guidelines rate routine aspiration thrombectomy as class III, with “no benefit” and “not useful,” and selective and bailout thrombectomy as a class IIb recommendation, with usefulness that is “not well established.”

Selective use of thrombectomy will require good judgment, noted Dr. O’Gara, who added “it will be important to see what effect, if any, these observations, this evidence, and this distillation of the recommendations from the writing committees have on a change in practice” – using thrombectomy to treat STEMI patients.

Dr. O’Gara chairs the STEMI writing panel of the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – Two guideline panels jointly upgraded percutaneous coronary interventions in noninfarct coronary arteries in patients with a recent MI, and downgraded manual aspiration thrombectomy in acute MI patients.

The panels, organized by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, cover, respectively, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and ST-elevation MI (STEMI).

The revised guidance on percutaneous coronary intervention for multivessel coronary disease affects roughly half the patients with an acute ST-elevation MI, those who have significant stenoses in noninfarct coronaries. The 2011 guidelines from the PCI panel (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011 Dec;58[24]:e44-122) and the 2013 guidelines from the STEMI committee (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Jan;61[4]:e78-140) only endorsed revascularization of stenotic, noninfarct arteries in patients with cardiogenic shock or severe heart failure. Multivessel PCI for patients without hemodynamic compromise at the time of primary PCI was deemed a class III indication, “thought to confer harm,” based on the results of several observational studies, Dr. Patrick T. O’Gara said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

After the 2013 STEMI guidelines came out, results from four studies showed either benefit or no harm from multivessel PCI in patients with appropriate anatomy performed either at the time of primary PCI or as a scheduled, staged procedure soon after primary PCI, said Dr. O’Gara, professor and director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Three of the four studies, PRAMI (N Engl J Med. 2013 Sept 19;369[12]:1115-23), CvLPRIT (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 March;65[10]:963-72), and DANAMI-3–PRIMULTI (Lancet. 2015 Aug 15;386[9994]:665-71), are published, while results from the fourth, PRAGUE-13, came out in a meeting report this year but as of mid-November had not been published.

Based on these data the two committees reset PCI of noninfarct arteries as a class IIb recommendation that “could be considered” in selected STEMI patients with multivessel disease who are hemodynamically stable.

The guidelines further said that “insufficient data exist to inform a recommendation” about the optimal time for this multivessel PCI, which could be coincident with primary PCI or 2 days, 3 days, a week, or even later after initial PCI, said Dr. O’Gara. “The writing committees do not advocate for routine use of multivessel PCI; clinical judgment is obviously needed,” he cautioned.

The two committees also reassessed manual aspiration thrombectomy during primary PCI for STEMI, which until now has been a class IIa recommendation, “reasonable” for STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI. But based on the neutral results for thrombectomy in the recent findings from the two largest randomized trials of thrombectomy, TOTAL (N Engl J Med. 2015 April 9;372[15]:1389-98) and TASTE (N Engl J Med. 2013 Oct 24;369[17]:1587-97), as well as a recent, 17-trial meta-analysis, the revised guidelines rate routine aspiration thrombectomy as class III, with “no benefit” and “not useful,” and selective and bailout thrombectomy as a class IIb recommendation, with usefulness that is “not well established.”

Selective use of thrombectomy will require good judgment, noted Dr. O’Gara, who added “it will be important to see what effect, if any, these observations, this evidence, and this distillation of the recommendations from the writing committees have on a change in practice” – using thrombectomy to treat STEMI patients.

Dr. O’Gara chairs the STEMI writing panel of the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – Two guideline panels jointly upgraded percutaneous coronary interventions in noninfarct coronary arteries in patients with a recent MI, and downgraded manual aspiration thrombectomy in acute MI patients.

The panels, organized by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, cover, respectively, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and ST-elevation MI (STEMI).

The revised guidance on percutaneous coronary intervention for multivessel coronary disease affects roughly half the patients with an acute ST-elevation MI, those who have significant stenoses in noninfarct coronaries. The 2011 guidelines from the PCI panel (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011 Dec;58[24]:e44-122) and the 2013 guidelines from the STEMI committee (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Jan;61[4]:e78-140) only endorsed revascularization of stenotic, noninfarct arteries in patients with cardiogenic shock or severe heart failure. Multivessel PCI for patients without hemodynamic compromise at the time of primary PCI was deemed a class III indication, “thought to confer harm,” based on the results of several observational studies, Dr. Patrick T. O’Gara said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

After the 2013 STEMI guidelines came out, results from four studies showed either benefit or no harm from multivessel PCI in patients with appropriate anatomy performed either at the time of primary PCI or as a scheduled, staged procedure soon after primary PCI, said Dr. O’Gara, professor and director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Three of the four studies, PRAMI (N Engl J Med. 2013 Sept 19;369[12]:1115-23), CvLPRIT (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 March;65[10]:963-72), and DANAMI-3–PRIMULTI (Lancet. 2015 Aug 15;386[9994]:665-71), are published, while results from the fourth, PRAGUE-13, came out in a meeting report this year but as of mid-November had not been published.

Based on these data the two committees reset PCI of noninfarct arteries as a class IIb recommendation that “could be considered” in selected STEMI patients with multivessel disease who are hemodynamically stable.

The guidelines further said that “insufficient data exist to inform a recommendation” about the optimal time for this multivessel PCI, which could be coincident with primary PCI or 2 days, 3 days, a week, or even later after initial PCI, said Dr. O’Gara. “The writing committees do not advocate for routine use of multivessel PCI; clinical judgment is obviously needed,” he cautioned.

The two committees also reassessed manual aspiration thrombectomy during primary PCI for STEMI, which until now has been a class IIa recommendation, “reasonable” for STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI. But based on the neutral results for thrombectomy in the recent findings from the two largest randomized trials of thrombectomy, TOTAL (N Engl J Med. 2015 April 9;372[15]:1389-98) and TASTE (N Engl J Med. 2013 Oct 24;369[17]:1587-97), as well as a recent, 17-trial meta-analysis, the revised guidelines rate routine aspiration thrombectomy as class III, with “no benefit” and “not useful,” and selective and bailout thrombectomy as a class IIb recommendation, with usefulness that is “not well established.”

Selective use of thrombectomy will require good judgment, noted Dr. O’Gara, who added “it will be important to see what effect, if any, these observations, this evidence, and this distillation of the recommendations from the writing committees have on a change in practice” – using thrombectomy to treat STEMI patients.

Dr. O’Gara chairs the STEMI writing panel of the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

AHA: It’s best to have a cardiac arrest in Midwest

ORLANDO – Considerable regional variation exists across the United States in outcomes, including survival and hospital charges following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, Dr. Aiham Albaeni reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He presented an analysis of 155,592 adults who survived at least until hospital admission following non–trauma-related out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) during 2002-2012. The data came from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Nationwide Inpatient Sample, the largest all-payer U.S. inpatient database.

Mortality was lowest among patients whose OHCA occurred in the Midwest. Indeed, taking the Northeast region as the reference point in a multivariate analysis, the adjusted mortality risk was 14% lower in the Midwest and 9% lower in the South. There was no difference in survival rates between the West and Northeast in this analysis adjusted for age, gender, race, primary diagnosis, income, Charlson Comorbidity Index, primary payer, and hospital size and teaching status, reported Dr. Albaeni of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Total hospital charges for patients admitted following OHCA were far and away highest in the West, and this increased expenditure didn’t pay off in terms of a survival advantage. The Consumer Price Index–adjusted mean total hospital charges averaged $85,592 per patient in the West, $66,290 in the Northeast, $55,257 in the Midwest, and $54,878 in the South.

Outliers in terms of cost of care – that is, patients admitted with OHCA whose total hospital charges exceeded $109,000 per admission – were 85% more common in the West than the other three regions, he noted.

Hospital length of stay greater than 8 days occurred most often in the Northeast. These lengthier stays were 10%-12% less common in the other regions.

The explanation for the marked regional differences observed in this study remains unknown.

“These findings call for more efforts to identify a high-quality model of excellence that standardizes health care delivery and improves quality of care in low-performing regions,” said Dr. Albaeni.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study.

ORLANDO – Considerable regional variation exists across the United States in outcomes, including survival and hospital charges following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, Dr. Aiham Albaeni reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He presented an analysis of 155,592 adults who survived at least until hospital admission following non–trauma-related out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) during 2002-2012. The data came from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Nationwide Inpatient Sample, the largest all-payer U.S. inpatient database.

Mortality was lowest among patients whose OHCA occurred in the Midwest. Indeed, taking the Northeast region as the reference point in a multivariate analysis, the adjusted mortality risk was 14% lower in the Midwest and 9% lower in the South. There was no difference in survival rates between the West and Northeast in this analysis adjusted for age, gender, race, primary diagnosis, income, Charlson Comorbidity Index, primary payer, and hospital size and teaching status, reported Dr. Albaeni of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Total hospital charges for patients admitted following OHCA were far and away highest in the West, and this increased expenditure didn’t pay off in terms of a survival advantage. The Consumer Price Index–adjusted mean total hospital charges averaged $85,592 per patient in the West, $66,290 in the Northeast, $55,257 in the Midwest, and $54,878 in the South.

Outliers in terms of cost of care – that is, patients admitted with OHCA whose total hospital charges exceeded $109,000 per admission – were 85% more common in the West than the other three regions, he noted.