User login

Ketogenic diet, with variations, can help adult epilepsy

HOUSTON – The ketogenic diet is usually thought of as a solution of near-last resort for pediatric epilepsy, but some adolescents and adults with epilepsy can also benefit from a very low carbohydrate diet.

There are also limited data to suggest that more palatable adaptations of the diet may provide benefit while improving adherence, said Mackenzie C. Cervenka, MD, speaking at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“Ketogenic diets are a reasonable option for older adolescents and adults with drug-resistant epilepsy that’s not amenable to surgical intervention,” said Dr. Cervenka, director of the Adult Epilepsy Diet Center at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

The antiepileptic benefit of a diet that induces ketogenesis, forcing the brain to utilize ketone bodies rather than glucose for energy, has been known since the 1920s, with benefit seen for adolescents and adults in studies completed in the 1930s. These diets mimic a starvation state, but provide enough calories through fat or protein to maintain weight. Calories in the traditional ketogenic diet, Dr. Cervenka said, are about 90% fat. Food for patients on this diet should be weighed on a gram scale, and those preparing meals should aim for a ratio of 3 to 4 grams of fat for each gram of carbohydrate and protein combined. A modified version uses a 1:1 or 2:1 ratio, a more appealing configuration for some patients.

Weighing each bite of food is cumbersome, and palatability can be a major problem as well, contributing to adherence problems with such a high-fat diet. However, for patients who are so ill that they are tube-fed, commercially available ketogenic formulas are available. Necessary supplementation on a traditional ketogenic diet includes calcium, vitamin D, multivitamins, and oral citrates to prevent kidney stone formation, she said.

However, ketogenic diets are known to be anti-inflammatory: Animal models have shown less inflammation, pain, and fever when rats are fed a ketogenic diet. Also, proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines are reduced on a ketogenic diet in a rodent model of Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis. Particularly for patients with autoimmune encephalopathies, the ketogenic diet has been shown to be of benefit.

One option with promising, but limited, results is a low-carbohydrate diet rich in medium-chain triglycerides. Medium chain triglyceride (MCT) oil is available in a commercial preparation derived from coconut or palm kernel oil. On this diet, 30%-60% of calories should come from MCTs, which is usually sufficient to induce ketosis. However, gastrointestinal side effects such as bloating and diarrhea can be pronounced, especially if the diet is begun abruptly. It’s best to ramp up slowly with MCTs, so this diet would not be appropriate for the patient who needs quick improvement in seizure control, Dr. Cervenka said.

A modified Atkins diet provides 15-20 grams of net carbohydrates daily, after dietary fiber is subtracted. Using this strategy, adolescents and adults don’t have to weigh foods. Rather, food tables are used to track carbohydrates and fiber, and ketosis is assessed by measuring urine ketones on a test strip. The goal, Dr. Cervenka said, is to achieve moderate to large ketosis (40-160 ng/mL urine ketones).

Finally, low glycemic index treatment (LGIT) is an option worth considering. This diet takes advantage of certain carbohydrate-rich foods that do not raise blood sugar quickly, such as fiber-rich vegetables or legumes with some fat content. Patients on the LGIT diet can have from 40 to 60 grams of carbohydrate daily, and the diet has been used with some success in drug-resistant childhood epilepsy as well as Angelman syndrome, she said.

Though sample sizes are small and efficacy may be modest, Dr. Cervenka said, “the effect is quick.” Finding less-restrictive modifications of these diets may help patients stay on the diet over the long term, increasing real-world effectiveness.

But long-term adherence to a ketogenic or other high-fat, low-residue diet comes with a host of unknowns about cardiovascular, metabolic, and renal health; ongoing study of these patients may yield answers about whether theoretical concerns are borne out, and whether the risk is worth it in terms of seizure benefit.

Dr. Cervenka reported receiving grant support from Nutricia North America, Vitaflo, and the BrightFocus Foundation. She has also received an honorarium for speaking from LivaNova.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – The ketogenic diet is usually thought of as a solution of near-last resort for pediatric epilepsy, but some adolescents and adults with epilepsy can also benefit from a very low carbohydrate diet.

There are also limited data to suggest that more palatable adaptations of the diet may provide benefit while improving adherence, said Mackenzie C. Cervenka, MD, speaking at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“Ketogenic diets are a reasonable option for older adolescents and adults with drug-resistant epilepsy that’s not amenable to surgical intervention,” said Dr. Cervenka, director of the Adult Epilepsy Diet Center at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

The antiepileptic benefit of a diet that induces ketogenesis, forcing the brain to utilize ketone bodies rather than glucose for energy, has been known since the 1920s, with benefit seen for adolescents and adults in studies completed in the 1930s. These diets mimic a starvation state, but provide enough calories through fat or protein to maintain weight. Calories in the traditional ketogenic diet, Dr. Cervenka said, are about 90% fat. Food for patients on this diet should be weighed on a gram scale, and those preparing meals should aim for a ratio of 3 to 4 grams of fat for each gram of carbohydrate and protein combined. A modified version uses a 1:1 or 2:1 ratio, a more appealing configuration for some patients.

Weighing each bite of food is cumbersome, and palatability can be a major problem as well, contributing to adherence problems with such a high-fat diet. However, for patients who are so ill that they are tube-fed, commercially available ketogenic formulas are available. Necessary supplementation on a traditional ketogenic diet includes calcium, vitamin D, multivitamins, and oral citrates to prevent kidney stone formation, she said.

However, ketogenic diets are known to be anti-inflammatory: Animal models have shown less inflammation, pain, and fever when rats are fed a ketogenic diet. Also, proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines are reduced on a ketogenic diet in a rodent model of Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis. Particularly for patients with autoimmune encephalopathies, the ketogenic diet has been shown to be of benefit.

One option with promising, but limited, results is a low-carbohydrate diet rich in medium-chain triglycerides. Medium chain triglyceride (MCT) oil is available in a commercial preparation derived from coconut or palm kernel oil. On this diet, 30%-60% of calories should come from MCTs, which is usually sufficient to induce ketosis. However, gastrointestinal side effects such as bloating and diarrhea can be pronounced, especially if the diet is begun abruptly. It’s best to ramp up slowly with MCTs, so this diet would not be appropriate for the patient who needs quick improvement in seizure control, Dr. Cervenka said.

A modified Atkins diet provides 15-20 grams of net carbohydrates daily, after dietary fiber is subtracted. Using this strategy, adolescents and adults don’t have to weigh foods. Rather, food tables are used to track carbohydrates and fiber, and ketosis is assessed by measuring urine ketones on a test strip. The goal, Dr. Cervenka said, is to achieve moderate to large ketosis (40-160 ng/mL urine ketones).

Finally, low glycemic index treatment (LGIT) is an option worth considering. This diet takes advantage of certain carbohydrate-rich foods that do not raise blood sugar quickly, such as fiber-rich vegetables or legumes with some fat content. Patients on the LGIT diet can have from 40 to 60 grams of carbohydrate daily, and the diet has been used with some success in drug-resistant childhood epilepsy as well as Angelman syndrome, she said.

Though sample sizes are small and efficacy may be modest, Dr. Cervenka said, “the effect is quick.” Finding less-restrictive modifications of these diets may help patients stay on the diet over the long term, increasing real-world effectiveness.

But long-term adherence to a ketogenic or other high-fat, low-residue diet comes with a host of unknowns about cardiovascular, metabolic, and renal health; ongoing study of these patients may yield answers about whether theoretical concerns are borne out, and whether the risk is worth it in terms of seizure benefit.

Dr. Cervenka reported receiving grant support from Nutricia North America, Vitaflo, and the BrightFocus Foundation. She has also received an honorarium for speaking from LivaNova.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – The ketogenic diet is usually thought of as a solution of near-last resort for pediatric epilepsy, but some adolescents and adults with epilepsy can also benefit from a very low carbohydrate diet.

There are also limited data to suggest that more palatable adaptations of the diet may provide benefit while improving adherence, said Mackenzie C. Cervenka, MD, speaking at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“Ketogenic diets are a reasonable option for older adolescents and adults with drug-resistant epilepsy that’s not amenable to surgical intervention,” said Dr. Cervenka, director of the Adult Epilepsy Diet Center at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

The antiepileptic benefit of a diet that induces ketogenesis, forcing the brain to utilize ketone bodies rather than glucose for energy, has been known since the 1920s, with benefit seen for adolescents and adults in studies completed in the 1930s. These diets mimic a starvation state, but provide enough calories through fat or protein to maintain weight. Calories in the traditional ketogenic diet, Dr. Cervenka said, are about 90% fat. Food for patients on this diet should be weighed on a gram scale, and those preparing meals should aim for a ratio of 3 to 4 grams of fat for each gram of carbohydrate and protein combined. A modified version uses a 1:1 or 2:1 ratio, a more appealing configuration for some patients.

Weighing each bite of food is cumbersome, and palatability can be a major problem as well, contributing to adherence problems with such a high-fat diet. However, for patients who are so ill that they are tube-fed, commercially available ketogenic formulas are available. Necessary supplementation on a traditional ketogenic diet includes calcium, vitamin D, multivitamins, and oral citrates to prevent kidney stone formation, she said.

However, ketogenic diets are known to be anti-inflammatory: Animal models have shown less inflammation, pain, and fever when rats are fed a ketogenic diet. Also, proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines are reduced on a ketogenic diet in a rodent model of Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis. Particularly for patients with autoimmune encephalopathies, the ketogenic diet has been shown to be of benefit.

One option with promising, but limited, results is a low-carbohydrate diet rich in medium-chain triglycerides. Medium chain triglyceride (MCT) oil is available in a commercial preparation derived from coconut or palm kernel oil. On this diet, 30%-60% of calories should come from MCTs, which is usually sufficient to induce ketosis. However, gastrointestinal side effects such as bloating and diarrhea can be pronounced, especially if the diet is begun abruptly. It’s best to ramp up slowly with MCTs, so this diet would not be appropriate for the patient who needs quick improvement in seizure control, Dr. Cervenka said.

A modified Atkins diet provides 15-20 grams of net carbohydrates daily, after dietary fiber is subtracted. Using this strategy, adolescents and adults don’t have to weigh foods. Rather, food tables are used to track carbohydrates and fiber, and ketosis is assessed by measuring urine ketones on a test strip. The goal, Dr. Cervenka said, is to achieve moderate to large ketosis (40-160 ng/mL urine ketones).

Finally, low glycemic index treatment (LGIT) is an option worth considering. This diet takes advantage of certain carbohydrate-rich foods that do not raise blood sugar quickly, such as fiber-rich vegetables or legumes with some fat content. Patients on the LGIT diet can have from 40 to 60 grams of carbohydrate daily, and the diet has been used with some success in drug-resistant childhood epilepsy as well as Angelman syndrome, she said.

Though sample sizes are small and efficacy may be modest, Dr. Cervenka said, “the effect is quick.” Finding less-restrictive modifications of these diets may help patients stay on the diet over the long term, increasing real-world effectiveness.

But long-term adherence to a ketogenic or other high-fat, low-residue diet comes with a host of unknowns about cardiovascular, metabolic, and renal health; ongoing study of these patients may yield answers about whether theoretical concerns are borne out, and whether the risk is worth it in terms of seizure benefit.

Dr. Cervenka reported receiving grant support from Nutricia North America, Vitaflo, and the BrightFocus Foundation. She has also received an honorarium for speaking from LivaNova.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AES 2016

Few drug-resistant epilepsy patients recruitable for trials of new AEDs

HOUSTON – Fewer than 8% of adult patients with drug-resistant epilepsy would have been recruitable for recent phase II and III trials of new antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), results from a single-center study showed.

The findings underscore a need to rethink how phase II and III trials of AEDs are conducted, Bernhard J. Steinhoff, MD, said in an interview prior to the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “In spite of the marketing of numerous new antiepileptic drugs, the percentage of drug-resistant epilepsies has remained almost unchanged,” said Dr. Steinhoff of the Kork (Germany) Epilepsy Center. “I am not aware that anybody involved in the issue of clinical trials with AEDs addressed the problem [of] whether the pivotal trials really cover the patients the new AEDs are developed for: namely, patients with drug-resistant epilepsies. Every time we start with a new drug after licensing, we realize that we have no clue whether this drug will be appropriate for our difficult-to-treat patients. We wondered whether the design of the usual phase II and III randomized controlled trials covers an acceptable percentage of AED-resistant epilepsy patients.”

“The result was frightening because less than 10% [of patients] would have been covered by the trials,” Dr. Steinhoff said. “Therefore, we suggest that a bad trials strategy may be responsible for the fact that the percentage of drug-resistant patients has not been markedly reduced by more than 15 new AEDs that were introduced during the recent years.” He added that pivotal trials with new AEDs “show superiority over placebo as add-on in an extremely limited group of difficult-to-treat patients. After licensing and marketing, we start to learn whether a new AED is appropriate for our drug-resistant patients.”

Medical writing was funded by an unrestricted grant from UCB. Dr. Steinhoff reported having no financial conflicts.

HOUSTON – Fewer than 8% of adult patients with drug-resistant epilepsy would have been recruitable for recent phase II and III trials of new antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), results from a single-center study showed.

The findings underscore a need to rethink how phase II and III trials of AEDs are conducted, Bernhard J. Steinhoff, MD, said in an interview prior to the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “In spite of the marketing of numerous new antiepileptic drugs, the percentage of drug-resistant epilepsies has remained almost unchanged,” said Dr. Steinhoff of the Kork (Germany) Epilepsy Center. “I am not aware that anybody involved in the issue of clinical trials with AEDs addressed the problem [of] whether the pivotal trials really cover the patients the new AEDs are developed for: namely, patients with drug-resistant epilepsies. Every time we start with a new drug after licensing, we realize that we have no clue whether this drug will be appropriate for our difficult-to-treat patients. We wondered whether the design of the usual phase II and III randomized controlled trials covers an acceptable percentage of AED-resistant epilepsy patients.”

“The result was frightening because less than 10% [of patients] would have been covered by the trials,” Dr. Steinhoff said. “Therefore, we suggest that a bad trials strategy may be responsible for the fact that the percentage of drug-resistant patients has not been markedly reduced by more than 15 new AEDs that were introduced during the recent years.” He added that pivotal trials with new AEDs “show superiority over placebo as add-on in an extremely limited group of difficult-to-treat patients. After licensing and marketing, we start to learn whether a new AED is appropriate for our drug-resistant patients.”

Medical writing was funded by an unrestricted grant from UCB. Dr. Steinhoff reported having no financial conflicts.

HOUSTON – Fewer than 8% of adult patients with drug-resistant epilepsy would have been recruitable for recent phase II and III trials of new antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), results from a single-center study showed.

The findings underscore a need to rethink how phase II and III trials of AEDs are conducted, Bernhard J. Steinhoff, MD, said in an interview prior to the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “In spite of the marketing of numerous new antiepileptic drugs, the percentage of drug-resistant epilepsies has remained almost unchanged,” said Dr. Steinhoff of the Kork (Germany) Epilepsy Center. “I am not aware that anybody involved in the issue of clinical trials with AEDs addressed the problem [of] whether the pivotal trials really cover the patients the new AEDs are developed for: namely, patients with drug-resistant epilepsies. Every time we start with a new drug after licensing, we realize that we have no clue whether this drug will be appropriate for our difficult-to-treat patients. We wondered whether the design of the usual phase II and III randomized controlled trials covers an acceptable percentage of AED-resistant epilepsy patients.”

“The result was frightening because less than 10% [of patients] would have been covered by the trials,” Dr. Steinhoff said. “Therefore, we suggest that a bad trials strategy may be responsible for the fact that the percentage of drug-resistant patients has not been markedly reduced by more than 15 new AEDs that were introduced during the recent years.” He added that pivotal trials with new AEDs “show superiority over placebo as add-on in an extremely limited group of difficult-to-treat patients. After licensing and marketing, we start to learn whether a new AED is appropriate for our drug-resistant patients.”

Medical writing was funded by an unrestricted grant from UCB. Dr. Steinhoff reported having no financial conflicts.

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Only 7.4% of patients would have fulfilled the inclusion criteria of five phase II and III trials of new AEDs.

Data source: A review of 216 outpatients with drug-resistant epilepsies.

Disclosures: Medical writing was funded by an unrestricted grant from UCB. Dr. Steinhoff reported having no financial disclosures.

Wide variation seen in treatment of infantile spasms

HOUSTON – The types of diagnostic tests ordered and medication used for treatment of infantile spasms vary considerably, a large study of children’s hospitals showed.

“Children with infantile spasms often require extensive diagnostic work-up to determine etiology, expensive medications for treatment, and hospitalization during the initiation of certain therapies,” researchers led by Sunita N. Misra, MD, PhD, wrote in an abstract presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “The common diagnostic studies and therapies have evolved over the last several decades.”

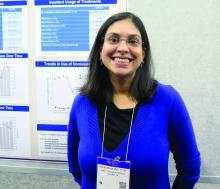

The researchers collected patient demographics, hospital length of stay, hospital admission cost, use of various diagnostic studies (such as lumbar puncture, brain MRI, and EEG), and medications used for infantile spasms (including antiepileptic drugs, corticotropin, and steroids). Cost data, calculated as a ratio of cost to charges, were collected and adjusted to 2014 dollars.

A total of 6,183 patients were included in the analysis and their average age of infantile-spasm diagnosis was 9 months. The most common diagnostic test ordered was EEG (76%), followed by brain imaging (57%), organic acids (38%), and lumbar puncture (17%). Medications were started during inpatient hospitalization in two-thirds of patients, with 33% starting on corticotropin; 29% on topiramate; and fewer than 10% of patients on an oral or intravenous steroid, zonisamide, or vigabatrin (Sabril). Use of corticotropin decreased over time, while use of oral steroids trended upwards. “We were surprised that one-third of patients did not have a medication initiated as an inpatient, given the studies showing earlier use of effective therapy has better outcomes,” Dr. Misra said in an interview in advance of the meeting.

“The cost of taking care of children with infantile spasms has increased over the study period 2004-2014,” Dr. Misra said. “Although we identified a few contributors to rising cost, there are probably other factors that need to be considered in future studies.” She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its retrospective design and the fact that it only identified cost associated with the initial admission. “Several of the diagnostic studies and medications may be initiated as an outpatient, for which we do not have the data,” she said.

Dr. Misra reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – The types of diagnostic tests ordered and medication used for treatment of infantile spasms vary considerably, a large study of children’s hospitals showed.

“Children with infantile spasms often require extensive diagnostic work-up to determine etiology, expensive medications for treatment, and hospitalization during the initiation of certain therapies,” researchers led by Sunita N. Misra, MD, PhD, wrote in an abstract presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “The common diagnostic studies and therapies have evolved over the last several decades.”

The researchers collected patient demographics, hospital length of stay, hospital admission cost, use of various diagnostic studies (such as lumbar puncture, brain MRI, and EEG), and medications used for infantile spasms (including antiepileptic drugs, corticotropin, and steroids). Cost data, calculated as a ratio of cost to charges, were collected and adjusted to 2014 dollars.

A total of 6,183 patients were included in the analysis and their average age of infantile-spasm diagnosis was 9 months. The most common diagnostic test ordered was EEG (76%), followed by brain imaging (57%), organic acids (38%), and lumbar puncture (17%). Medications were started during inpatient hospitalization in two-thirds of patients, with 33% starting on corticotropin; 29% on topiramate; and fewer than 10% of patients on an oral or intravenous steroid, zonisamide, or vigabatrin (Sabril). Use of corticotropin decreased over time, while use of oral steroids trended upwards. “We were surprised that one-third of patients did not have a medication initiated as an inpatient, given the studies showing earlier use of effective therapy has better outcomes,” Dr. Misra said in an interview in advance of the meeting.

“The cost of taking care of children with infantile spasms has increased over the study period 2004-2014,” Dr. Misra said. “Although we identified a few contributors to rising cost, there are probably other factors that need to be considered in future studies.” She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its retrospective design and the fact that it only identified cost associated with the initial admission. “Several of the diagnostic studies and medications may be initiated as an outpatient, for which we do not have the data,” she said.

Dr. Misra reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – The types of diagnostic tests ordered and medication used for treatment of infantile spasms vary considerably, a large study of children’s hospitals showed.

“Children with infantile spasms often require extensive diagnostic work-up to determine etiology, expensive medications for treatment, and hospitalization during the initiation of certain therapies,” researchers led by Sunita N. Misra, MD, PhD, wrote in an abstract presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “The common diagnostic studies and therapies have evolved over the last several decades.”

The researchers collected patient demographics, hospital length of stay, hospital admission cost, use of various diagnostic studies (such as lumbar puncture, brain MRI, and EEG), and medications used for infantile spasms (including antiepileptic drugs, corticotropin, and steroids). Cost data, calculated as a ratio of cost to charges, were collected and adjusted to 2014 dollars.

A total of 6,183 patients were included in the analysis and their average age of infantile-spasm diagnosis was 9 months. The most common diagnostic test ordered was EEG (76%), followed by brain imaging (57%), organic acids (38%), and lumbar puncture (17%). Medications were started during inpatient hospitalization in two-thirds of patients, with 33% starting on corticotropin; 29% on topiramate; and fewer than 10% of patients on an oral or intravenous steroid, zonisamide, or vigabatrin (Sabril). Use of corticotropin decreased over time, while use of oral steroids trended upwards. “We were surprised that one-third of patients did not have a medication initiated as an inpatient, given the studies showing earlier use of effective therapy has better outcomes,” Dr. Misra said in an interview in advance of the meeting.

“The cost of taking care of children with infantile spasms has increased over the study period 2004-2014,” Dr. Misra said. “Although we identified a few contributors to rising cost, there are probably other factors that need to be considered in future studies.” She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its retrospective design and the fact that it only identified cost associated with the initial admission. “Several of the diagnostic studies and medications may be initiated as an outpatient, for which we do not have the data,” she said.

Dr. Misra reported having no financial disclosures.

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The most common diagnostic test ordered was EEG (76%), followed by brain imaging (57%), organic acids (38%), and lumbar puncture (17%).

Data source: Retrospective analysis of data on 6,183 patients with infantile spasms between 2004 and 2014.

Disclosures: Dr. Misra reported having no financial disclosures.

Wrist-worn system detected convulsive seizures in home setting

HOUSTON – A wrist-worn device and smartphone-based alert system worn by a patient outside of the epilepsy monitoring unit for 3 months effectively detected convulsive seizure events and minimized false alarms, results from a long-term study found.

The automated device, known as Embrace, relies on an accelerometer and electrodermal activity to detect convulsive seizures. It pairs a wrist-worn device with a smartphone-based application that provides an alert to designated caregivers when an unusual event is detected. Embrace, which is being developed by Empatica Inc., received clearance by the European Union as a medical device for convulsive seizure detection but is still under consideration by the Food and Drug Administration. Previous reports evaluating the automated detector used by Embrace have always relied on data from epilepsy monitoring units (EMUs), where it achieved sensitivity scores ranging from 92% to 100% and 0.15-2.02 false alarms per day in detecting convulsive seizures.

To find out, Dr. Picard, chief scientist at Empatica, and her associates conducted a case study of a 14-year-old patient with Dravet syndrome who was enrolled in a trial of Embrace in the outpatient setting. No data from this patient were used in training the system. The patient’s caregiver was asked to annotate the occurrence of each convulsive seizure and any activity that generated an alert. The number of false alerts was obtained by subtracting the number of correctly recognized convulsive seizures from the total alerts fired by the device. Sensitivity was the percentage of convulsive seizures that automatically triggered an alert.

“Embrace can work for patients outside the EMU, detecting events and issuing alerts through a paired smartphone to a designated caregiver. Also, for clinicians who understand machine learning, we should be clear that we used the strongest test possible: none of the patient’s data were used to train the algorithm that was used, nor was it tuned in any way special for this patient. Had we done so, the results could have possibly appeared even better. However, we chose to use this test of generalization to better get a sense of how it might work on new patients, whose data had never been seen before.”

Dr. Picard acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it was a single case and that the patient had Dravet syndrome. She disclosed that she is a cofounder of Empatica and owns shares in the company.

HOUSTON – A wrist-worn device and smartphone-based alert system worn by a patient outside of the epilepsy monitoring unit for 3 months effectively detected convulsive seizure events and minimized false alarms, results from a long-term study found.

The automated device, known as Embrace, relies on an accelerometer and electrodermal activity to detect convulsive seizures. It pairs a wrist-worn device with a smartphone-based application that provides an alert to designated caregivers when an unusual event is detected. Embrace, which is being developed by Empatica Inc., received clearance by the European Union as a medical device for convulsive seizure detection but is still under consideration by the Food and Drug Administration. Previous reports evaluating the automated detector used by Embrace have always relied on data from epilepsy monitoring units (EMUs), where it achieved sensitivity scores ranging from 92% to 100% and 0.15-2.02 false alarms per day in detecting convulsive seizures.

To find out, Dr. Picard, chief scientist at Empatica, and her associates conducted a case study of a 14-year-old patient with Dravet syndrome who was enrolled in a trial of Embrace in the outpatient setting. No data from this patient were used in training the system. The patient’s caregiver was asked to annotate the occurrence of each convulsive seizure and any activity that generated an alert. The number of false alerts was obtained by subtracting the number of correctly recognized convulsive seizures from the total alerts fired by the device. Sensitivity was the percentage of convulsive seizures that automatically triggered an alert.

“Embrace can work for patients outside the EMU, detecting events and issuing alerts through a paired smartphone to a designated caregiver. Also, for clinicians who understand machine learning, we should be clear that we used the strongest test possible: none of the patient’s data were used to train the algorithm that was used, nor was it tuned in any way special for this patient. Had we done so, the results could have possibly appeared even better. However, we chose to use this test of generalization to better get a sense of how it might work on new patients, whose data had never been seen before.”

Dr. Picard acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it was a single case and that the patient had Dravet syndrome. She disclosed that she is a cofounder of Empatica and owns shares in the company.

HOUSTON – A wrist-worn device and smartphone-based alert system worn by a patient outside of the epilepsy monitoring unit for 3 months effectively detected convulsive seizure events and minimized false alarms, results from a long-term study found.

The automated device, known as Embrace, relies on an accelerometer and electrodermal activity to detect convulsive seizures. It pairs a wrist-worn device with a smartphone-based application that provides an alert to designated caregivers when an unusual event is detected. Embrace, which is being developed by Empatica Inc., received clearance by the European Union as a medical device for convulsive seizure detection but is still under consideration by the Food and Drug Administration. Previous reports evaluating the automated detector used by Embrace have always relied on data from epilepsy monitoring units (EMUs), where it achieved sensitivity scores ranging from 92% to 100% and 0.15-2.02 false alarms per day in detecting convulsive seizures.

To find out, Dr. Picard, chief scientist at Empatica, and her associates conducted a case study of a 14-year-old patient with Dravet syndrome who was enrolled in a trial of Embrace in the outpatient setting. No data from this patient were used in training the system. The patient’s caregiver was asked to annotate the occurrence of each convulsive seizure and any activity that generated an alert. The number of false alerts was obtained by subtracting the number of correctly recognized convulsive seizures from the total alerts fired by the device. Sensitivity was the percentage of convulsive seizures that automatically triggered an alert.

“Embrace can work for patients outside the EMU, detecting events and issuing alerts through a paired smartphone to a designated caregiver. Also, for clinicians who understand machine learning, we should be clear that we used the strongest test possible: none of the patient’s data were used to train the algorithm that was used, nor was it tuned in any way special for this patient. Had we done so, the results could have possibly appeared even better. However, we chose to use this test of generalization to better get a sense of how it might work on new patients, whose data had never been seen before.”

Dr. Picard acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it was a single case and that the patient had Dravet syndrome. She disclosed that she is a cofounder of Empatica and owns shares in the company.

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A device known as Embrace detected 22 of the patient’s 24 convulsive seizure events, for a sensitivity of 92% and a false-alarm rate of 0.35 false alarms per day worn.

Data source: Case study of a 14-year-old patient with Dravet syndrome who was enrolled in a trial of Embrace in the outpatient setting and used the device for 113 days.

Disclosures: Dr. Picard is a cofounder of Empatica. She also owns shares in the company.

Rate of mosaicism in parents of children with epileptic encephalopathy likely underestimated

HOUSTON – The rate of parental mosaicism in children with sporadic cases of epileptic encephalopathy and an apparent de novo mutation is believed to be at least 10%, which is much higher than previously thought.

The discovery, which was revealed with advanced genetic testing methods, underscores the need to rethink how parents of children with epileptic encephalopathy are counseled with regard to family planning, lead study author Candace T. Myers, PhD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “Generally, families are counseled with a recurrence risk of 1%-3%, but we found that in 10% of our families their recurrence risk is much higher because we’re able to see the genetic mutation in either blood or saliva of an unaffected parent,” said Dr. Myers of the division of genetic medicine in the department of pediatrics at the University of Washington, Seattle. “If we’re able to detect it in either of those tissues that means that the level in their gametes is much higher than just a single cell or a handful of cells, which is usually how people think about de novo mutations. What we’re finding is that in 10% of cases these mutations happen during embryonic development of the parent.”

Dr. Myers reported that of the 109 families screened, 10 cases of low-level somatic mosaicism were identified: 6 in fathers and 4 in mothers. The fraction of mutant alleles identified ranged from 3%-25%, which are levels that would pass undetected by traditional Sanger sequencing methods. In three families where a mosaic parent was identified, there were multiple affected children. The finding “opens up more questions for families that are thinking about future pregnancies,” she said. “I think we should have more genetic counselors working with pediatric neurologists to facilitate those discussions.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that DNA samples were extracted only from blood and saliva. “If the mutation is not present or detected in those particular tissues, it is still possible for the parent to be a germline carrier,” Dr. Myers said. “The most relevant tissue type for us to be testing would be the sex cells. We’ll have to look for families to see if they’re willing to donate [those cells] for future studies.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Myers is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship provided by the Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome Foundation and by the American Epilepsy Society. She reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – The rate of parental mosaicism in children with sporadic cases of epileptic encephalopathy and an apparent de novo mutation is believed to be at least 10%, which is much higher than previously thought.

The discovery, which was revealed with advanced genetic testing methods, underscores the need to rethink how parents of children with epileptic encephalopathy are counseled with regard to family planning, lead study author Candace T. Myers, PhD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “Generally, families are counseled with a recurrence risk of 1%-3%, but we found that in 10% of our families their recurrence risk is much higher because we’re able to see the genetic mutation in either blood or saliva of an unaffected parent,” said Dr. Myers of the division of genetic medicine in the department of pediatrics at the University of Washington, Seattle. “If we’re able to detect it in either of those tissues that means that the level in their gametes is much higher than just a single cell or a handful of cells, which is usually how people think about de novo mutations. What we’re finding is that in 10% of cases these mutations happen during embryonic development of the parent.”

Dr. Myers reported that of the 109 families screened, 10 cases of low-level somatic mosaicism were identified: 6 in fathers and 4 in mothers. The fraction of mutant alleles identified ranged from 3%-25%, which are levels that would pass undetected by traditional Sanger sequencing methods. In three families where a mosaic parent was identified, there were multiple affected children. The finding “opens up more questions for families that are thinking about future pregnancies,” she said. “I think we should have more genetic counselors working with pediatric neurologists to facilitate those discussions.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that DNA samples were extracted only from blood and saliva. “If the mutation is not present or detected in those particular tissues, it is still possible for the parent to be a germline carrier,” Dr. Myers said. “The most relevant tissue type for us to be testing would be the sex cells. We’ll have to look for families to see if they’re willing to donate [those cells] for future studies.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Myers is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship provided by the Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome Foundation and by the American Epilepsy Society. She reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – The rate of parental mosaicism in children with sporadic cases of epileptic encephalopathy and an apparent de novo mutation is believed to be at least 10%, which is much higher than previously thought.

The discovery, which was revealed with advanced genetic testing methods, underscores the need to rethink how parents of children with epileptic encephalopathy are counseled with regard to family planning, lead study author Candace T. Myers, PhD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “Generally, families are counseled with a recurrence risk of 1%-3%, but we found that in 10% of our families their recurrence risk is much higher because we’re able to see the genetic mutation in either blood or saliva of an unaffected parent,” said Dr. Myers of the division of genetic medicine in the department of pediatrics at the University of Washington, Seattle. “If we’re able to detect it in either of those tissues that means that the level in their gametes is much higher than just a single cell or a handful of cells, which is usually how people think about de novo mutations. What we’re finding is that in 10% of cases these mutations happen during embryonic development of the parent.”

Dr. Myers reported that of the 109 families screened, 10 cases of low-level somatic mosaicism were identified: 6 in fathers and 4 in mothers. The fraction of mutant alleles identified ranged from 3%-25%, which are levels that would pass undetected by traditional Sanger sequencing methods. In three families where a mosaic parent was identified, there were multiple affected children. The finding “opens up more questions for families that are thinking about future pregnancies,” she said. “I think we should have more genetic counselors working with pediatric neurologists to facilitate those discussions.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that DNA samples were extracted only from blood and saliva. “If the mutation is not present or detected in those particular tissues, it is still possible for the parent to be a germline carrier,” Dr. Myers said. “The most relevant tissue type for us to be testing would be the sex cells. We’ll have to look for families to see if they’re willing to donate [those cells] for future studies.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Myers is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship provided by the Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome Foundation and by the American Epilepsy Society. She reported having no financial disclosures.

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of 109 families screened, 10 cases of low-level somatic mosaicism were identified: 6 in fathers and 4 in mothers.

Data source: Screening of 109 families where the affected child’s epileptic encephalopathy was attributed to a substitution or small indel in 1 of 31 established epilepsy genes and reported as “de novo” by either clinical or research analysis of parental DNA.

Disclosures: The study was funded by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Myers is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship provided by the Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome Foundation and by the American Epilepsy Society. She reported having no financial disclosures.

Survey sheds light on clinical neurophysiology fellowship training

HOUSTON – Fellowship training in clinical neurophysiology delivered high rates of satisfaction, but recommended areas for improvements include more focus on training in sleep, brain mapping, and evoked potentials, results from a survey of current trainees found.

“There has been no systematic evaluation of neurophysiology fellowships,” Zulfi Haneef, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “In fact, there are some studies on neurology residency, but not on any of the neurology fellowships. This study opens a window into what the situation is after residency: what makes the residents decide on a fellowship, and how they feel they have done with the choice of fellowship.”

Overall, 87% of respondents expressed satisfaction with their current program and rated it as 4 or a 5 on a 1-5 Likert scale. “It seems that choosing a program based on the location may not have been the best thing to do,” he said. “Satisfaction scores (on a 1-5 scale for the training) were lower among those who chose a program based on location.” Less time spent in the epilepsy monitoring unit and EEG monitoring was also associated with higher satisfaction scores. “Rather than a lack of interest in epilepsy monitoring and EEG, this may reflect overemphasis on these at the expense of other areas, as these were also the areas that appeared to be most stressed during training,” Dr. Haneef said. The researchers observed no differences between male and female respondents in their answers to the various survey questions.

Based on the survey results, better clinical neurophysiology training in some areas were deemed necessary by the responding fellows, including sleep, brain mapping, and evoked potentials. Dr. Haneef acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it was voluntary. “As such there could be some self-selection of fellows who have stronger viewpoints that pushed them to respond to a survey,” he said. He reported having no financial disclosures related to the study.

HOUSTON – Fellowship training in clinical neurophysiology delivered high rates of satisfaction, but recommended areas for improvements include more focus on training in sleep, brain mapping, and evoked potentials, results from a survey of current trainees found.

“There has been no systematic evaluation of neurophysiology fellowships,” Zulfi Haneef, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “In fact, there are some studies on neurology residency, but not on any of the neurology fellowships. This study opens a window into what the situation is after residency: what makes the residents decide on a fellowship, and how they feel they have done with the choice of fellowship.”

Overall, 87% of respondents expressed satisfaction with their current program and rated it as 4 or a 5 on a 1-5 Likert scale. “It seems that choosing a program based on the location may not have been the best thing to do,” he said. “Satisfaction scores (on a 1-5 scale for the training) were lower among those who chose a program based on location.” Less time spent in the epilepsy monitoring unit and EEG monitoring was also associated with higher satisfaction scores. “Rather than a lack of interest in epilepsy monitoring and EEG, this may reflect overemphasis on these at the expense of other areas, as these were also the areas that appeared to be most stressed during training,” Dr. Haneef said. The researchers observed no differences between male and female respondents in their answers to the various survey questions.

Based on the survey results, better clinical neurophysiology training in some areas were deemed necessary by the responding fellows, including sleep, brain mapping, and evoked potentials. Dr. Haneef acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it was voluntary. “As such there could be some self-selection of fellows who have stronger viewpoints that pushed them to respond to a survey,” he said. He reported having no financial disclosures related to the study.

HOUSTON – Fellowship training in clinical neurophysiology delivered high rates of satisfaction, but recommended areas for improvements include more focus on training in sleep, brain mapping, and evoked potentials, results from a survey of current trainees found.

“There has been no systematic evaluation of neurophysiology fellowships,” Zulfi Haneef, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “In fact, there are some studies on neurology residency, but not on any of the neurology fellowships. This study opens a window into what the situation is after residency: what makes the residents decide on a fellowship, and how they feel they have done with the choice of fellowship.”

Overall, 87% of respondents expressed satisfaction with their current program and rated it as 4 or a 5 on a 1-5 Likert scale. “It seems that choosing a program based on the location may not have been the best thing to do,” he said. “Satisfaction scores (on a 1-5 scale for the training) were lower among those who chose a program based on location.” Less time spent in the epilepsy monitoring unit and EEG monitoring was also associated with higher satisfaction scores. “Rather than a lack of interest in epilepsy monitoring and EEG, this may reflect overemphasis on these at the expense of other areas, as these were also the areas that appeared to be most stressed during training,” Dr. Haneef said. The researchers observed no differences between male and female respondents in their answers to the various survey questions.

Based on the survey results, better clinical neurophysiology training in some areas were deemed necessary by the responding fellows, including sleep, brain mapping, and evoked potentials. Dr. Haneef acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it was voluntary. “As such there could be some self-selection of fellows who have stronger viewpoints that pushed them to respond to a survey,” he said. He reported having no financial disclosures related to the study.

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Overall, 87% of clinical neurophysiology fellows expressed satisfaction with their current program and rated it as 4 or a 5 on a 1-5 Likert scale.

Data source: An Internet-based survey of 49 clinical neurophysiology fellows in the United States.

Disclosures: Dr. Haneef reported having no financial disclosures related to the study.