User login

Treatment adherence makes big impact in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures

HOUSTON – Patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures who stick with evidence-based treatment have significantly fewer seizures and have less associated disability than do those who don’t make it to therapy and psychiatry visits, a study showed.

Reporting preliminary data from 59 patients in a 123-patient study, Benjamin Tolchin, MD, and his colleagues said that patients who adhered to their treatment plans were significantly more likely to experience a reduction in seizure frequency of more than 50%, compared with nonadherent patients (P = .018). Treatment dropout was positively associated with having a prior psychogenic nonepileptic seizure (PNES) diagnosis and with having less concern about the illness.

These figures, he said, are consistent with what’s been reported in the PNES literature. Others have found that after diagnosis, 20%-30% of patients don’t attend their first appointment, although psychiatric treatment and therapy constitute evidence-based care that is effective in treating PNES.

Dr. Tolchin said previous studies have found that “over 71% of patients were found to have seizures and associated disability at the 4-year follow-up mark.”

In addition to tracking adherence, Dr. Tolchin and his coinvestigators attempted to identify risk factors for nonadherence among their patient cohort, all of whom had documented PNES. Study participants provided general demographic data, and investigators also gathered information about PNES event frequency; any prior diagnosis of PNES or other psychiatric comorbidities; history of physical, emotional, or sexual abuse; and health care resource utilization. Patients also were asked about their quality of life and time from symptom onset to receiving the PNES diagnosis.

Finally, patients filled out the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIPQ). This instrument measures various aspects of patients’ cognitive and emotional representations of illness, using a nine-item questionnaire. Higher scores indicate that the patient sees the illness as more concerning.

All patients were referred for both psychotherapy and four follow-up visits with a psychiatrist. The first psychiatric visit was to occur within 1-2 months after receiving the PNES diagnosis, with the next two visits occurring at 1.5- to 3-month intervals following the first visit. The final scheduled follow-up visit was to occur 6-9 months after the third visit.

Most patients (85%) were female and non-Hispanic white (77%), with a mean age of 38 years (range, 18-80). About one-third of patients were single, and another third were married. The remainder were evenly split between having a live-in partner and being separated or divorced, with just 2% being widowed.

By self-report, more than one-third of patients (37%) were on disability, and nearly one-quarter (24%) were unemployed. Just 18% were working full time; another 11% worked part time, and 8% were students.

The median weekly number of PNES episodes per patient was two, although reported events per week ranged from 0 to 350.

Psychiatric comorbidities were very frequent: 94% of patients reported some variety of psychiatric disorder. Depressive disorders were reported by 78% of patients, anxiety disorders by 61%, and posttraumatic stress disorder by 54%. Other commonly reported psychiatric diagnoses included panic disorder (40%), phobias (38%), and personality disorders (31%).

Almost a quarter of patients (23%) had attempted suicide in the past, and the same percentage reported a history of substance abuse. Patient reports of emotional (57%), physical (45%), and sexual (42%) abuse were also common.

Having a prior diagnosis of PNES was identified as a significant risk factor for dropping out of treatment (hazard ratio, 1.57; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-2.46; P = .046]. Patients with a higher concern for their illness, as evidenced by a higher BIPQ score, were less likely to drop out of treatment (HR, 0.77 for 10-point increment; 95% CI, 0.64-0.93; P = .008).

“Neurologists and behavioral health specialists need new interventions to improve adherence with treatment and prevent long-term disability,” Dr. Tolchin said.

The study, which won the Kaufman Honor for the highest-ranking abstract in the comorbidities topic category at the meeting, was supported by a practice research training fellowship from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Brain Foundation. Dr. Tolchin reported no other disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – Patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures who stick with evidence-based treatment have significantly fewer seizures and have less associated disability than do those who don’t make it to therapy and psychiatry visits, a study showed.

Reporting preliminary data from 59 patients in a 123-patient study, Benjamin Tolchin, MD, and his colleagues said that patients who adhered to their treatment plans were significantly more likely to experience a reduction in seizure frequency of more than 50%, compared with nonadherent patients (P = .018). Treatment dropout was positively associated with having a prior psychogenic nonepileptic seizure (PNES) diagnosis and with having less concern about the illness.

These figures, he said, are consistent with what’s been reported in the PNES literature. Others have found that after diagnosis, 20%-30% of patients don’t attend their first appointment, although psychiatric treatment and therapy constitute evidence-based care that is effective in treating PNES.

Dr. Tolchin said previous studies have found that “over 71% of patients were found to have seizures and associated disability at the 4-year follow-up mark.”

In addition to tracking adherence, Dr. Tolchin and his coinvestigators attempted to identify risk factors for nonadherence among their patient cohort, all of whom had documented PNES. Study participants provided general demographic data, and investigators also gathered information about PNES event frequency; any prior diagnosis of PNES or other psychiatric comorbidities; history of physical, emotional, or sexual abuse; and health care resource utilization. Patients also were asked about their quality of life and time from symptom onset to receiving the PNES diagnosis.

Finally, patients filled out the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIPQ). This instrument measures various aspects of patients’ cognitive and emotional representations of illness, using a nine-item questionnaire. Higher scores indicate that the patient sees the illness as more concerning.

All patients were referred for both psychotherapy and four follow-up visits with a psychiatrist. The first psychiatric visit was to occur within 1-2 months after receiving the PNES diagnosis, with the next two visits occurring at 1.5- to 3-month intervals following the first visit. The final scheduled follow-up visit was to occur 6-9 months after the third visit.

Most patients (85%) were female and non-Hispanic white (77%), with a mean age of 38 years (range, 18-80). About one-third of patients were single, and another third were married. The remainder were evenly split between having a live-in partner and being separated or divorced, with just 2% being widowed.

By self-report, more than one-third of patients (37%) were on disability, and nearly one-quarter (24%) were unemployed. Just 18% were working full time; another 11% worked part time, and 8% were students.

The median weekly number of PNES episodes per patient was two, although reported events per week ranged from 0 to 350.

Psychiatric comorbidities were very frequent: 94% of patients reported some variety of psychiatric disorder. Depressive disorders were reported by 78% of patients, anxiety disorders by 61%, and posttraumatic stress disorder by 54%. Other commonly reported psychiatric diagnoses included panic disorder (40%), phobias (38%), and personality disorders (31%).

Almost a quarter of patients (23%) had attempted suicide in the past, and the same percentage reported a history of substance abuse. Patient reports of emotional (57%), physical (45%), and sexual (42%) abuse were also common.

Having a prior diagnosis of PNES was identified as a significant risk factor for dropping out of treatment (hazard ratio, 1.57; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-2.46; P = .046]. Patients with a higher concern for their illness, as evidenced by a higher BIPQ score, were less likely to drop out of treatment (HR, 0.77 for 10-point increment; 95% CI, 0.64-0.93; P = .008).

“Neurologists and behavioral health specialists need new interventions to improve adherence with treatment and prevent long-term disability,” Dr. Tolchin said.

The study, which won the Kaufman Honor for the highest-ranking abstract in the comorbidities topic category at the meeting, was supported by a practice research training fellowship from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Brain Foundation. Dr. Tolchin reported no other disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – Patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures who stick with evidence-based treatment have significantly fewer seizures and have less associated disability than do those who don’t make it to therapy and psychiatry visits, a study showed.

Reporting preliminary data from 59 patients in a 123-patient study, Benjamin Tolchin, MD, and his colleagues said that patients who adhered to their treatment plans were significantly more likely to experience a reduction in seizure frequency of more than 50%, compared with nonadherent patients (P = .018). Treatment dropout was positively associated with having a prior psychogenic nonepileptic seizure (PNES) diagnosis and with having less concern about the illness.

These figures, he said, are consistent with what’s been reported in the PNES literature. Others have found that after diagnosis, 20%-30% of patients don’t attend their first appointment, although psychiatric treatment and therapy constitute evidence-based care that is effective in treating PNES.

Dr. Tolchin said previous studies have found that “over 71% of patients were found to have seizures and associated disability at the 4-year follow-up mark.”

In addition to tracking adherence, Dr. Tolchin and his coinvestigators attempted to identify risk factors for nonadherence among their patient cohort, all of whom had documented PNES. Study participants provided general demographic data, and investigators also gathered information about PNES event frequency; any prior diagnosis of PNES or other psychiatric comorbidities; history of physical, emotional, or sexual abuse; and health care resource utilization. Patients also were asked about their quality of life and time from symptom onset to receiving the PNES diagnosis.

Finally, patients filled out the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIPQ). This instrument measures various aspects of patients’ cognitive and emotional representations of illness, using a nine-item questionnaire. Higher scores indicate that the patient sees the illness as more concerning.

All patients were referred for both psychotherapy and four follow-up visits with a psychiatrist. The first psychiatric visit was to occur within 1-2 months after receiving the PNES diagnosis, with the next two visits occurring at 1.5- to 3-month intervals following the first visit. The final scheduled follow-up visit was to occur 6-9 months after the third visit.

Most patients (85%) were female and non-Hispanic white (77%), with a mean age of 38 years (range, 18-80). About one-third of patients were single, and another third were married. The remainder were evenly split between having a live-in partner and being separated or divorced, with just 2% being widowed.

By self-report, more than one-third of patients (37%) were on disability, and nearly one-quarter (24%) were unemployed. Just 18% were working full time; another 11% worked part time, and 8% were students.

The median weekly number of PNES episodes per patient was two, although reported events per week ranged from 0 to 350.

Psychiatric comorbidities were very frequent: 94% of patients reported some variety of psychiatric disorder. Depressive disorders were reported by 78% of patients, anxiety disorders by 61%, and posttraumatic stress disorder by 54%. Other commonly reported psychiatric diagnoses included panic disorder (40%), phobias (38%), and personality disorders (31%).

Almost a quarter of patients (23%) had attempted suicide in the past, and the same percentage reported a history of substance abuse. Patient reports of emotional (57%), physical (45%), and sexual (42%) abuse were also common.

Having a prior diagnosis of PNES was identified as a significant risk factor for dropping out of treatment (hazard ratio, 1.57; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-2.46; P = .046]. Patients with a higher concern for their illness, as evidenced by a higher BIPQ score, were less likely to drop out of treatment (HR, 0.77 for 10-point increment; 95% CI, 0.64-0.93; P = .008).

“Neurologists and behavioral health specialists need new interventions to improve adherence with treatment and prevent long-term disability,” Dr. Tolchin said.

The study, which won the Kaufman Honor for the highest-ranking abstract in the comorbidities topic category at the meeting, was supported by a practice research training fellowship from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Brain Foundation. Dr. Tolchin reported no other disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Adherent patients were more likely to reduce their seizures by half or more (P = .018).

Data source: A study of 123 patients with documented PNES.

Disclosures: The study was funded by a practice research training fellowship from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Brain Foundation. Dr. Tolchin reported no other disclosures.

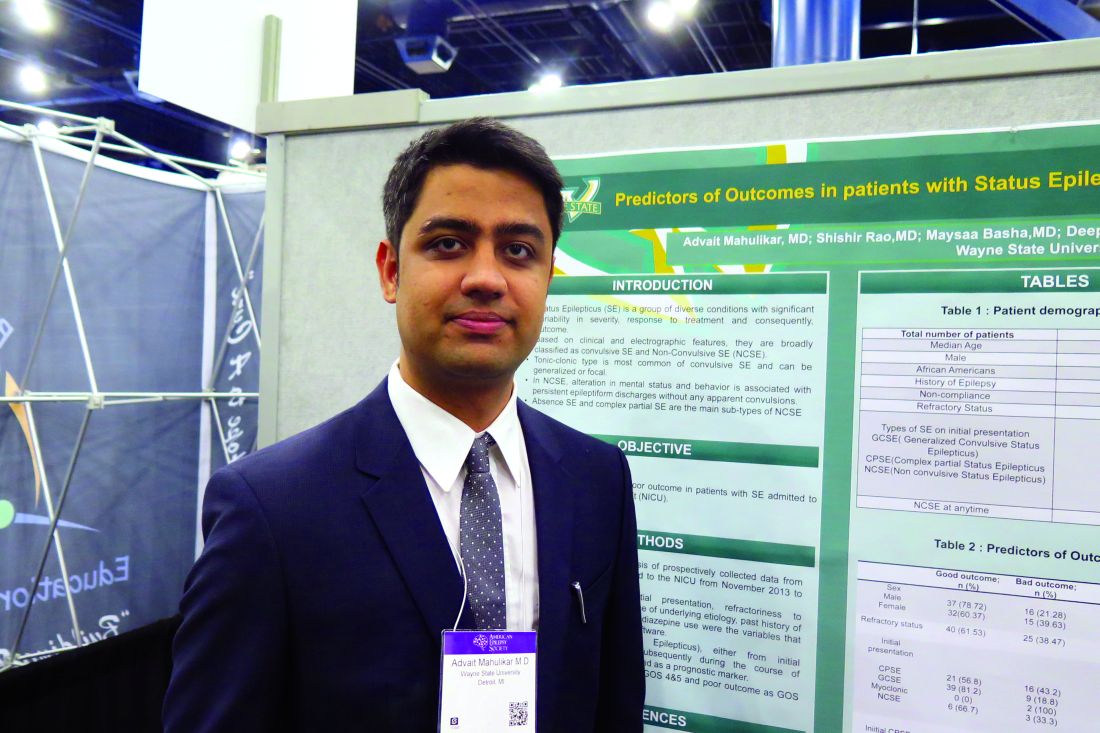

Study identifies predictors of poor outcome in status epilepticus

HOUSTON – Predictors of poor outcomes in patients with status epilepticus admitted to the neurointensive care unit include complex partial status epilepticus (CPSE), refractory status epilepticus, or the development of nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) at any time during the hospital course, according to results from a single-center study.

“Not a lot of data exist as to what predicts the poor outcomes and what’s known about the outcome in patients with status epilepticus,” lead study author Advait Mahulikar, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. To find out, he and his associates retrospectively reviewed data from 100 patients with status epilepticus who were admitted to the neurointensive care unit at Detroit Medical Center from November 2013 to January 2016. Variables of interest included patient demographics, initial presentation, refractoriness to treatment, presence or absence of underlying etiology, past history of epilepsy, and use of benzodiazepines on admission. Another variable of interest was NCSE, either from initial presentation or developed during the course of convulsive status epilepticus. A good outcome was defined as a Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) score of 4 or 5, and a poor outcome was defined as a GOS score of 1-3.

Neither age nor gender predicted poor outcome, and there was no difference in outcome between structural and nonstructural causes of status epilepticus. However, prior history of epilepsy was a strong negative predictor of poor outcome. In fact, only 14 of 70 patients (20%) with a prior history of epilepsy had a poor outcome (P less than .01). “The theory is that [these patients] were already on treatment for epilepsy in the past and that affected their outcome in a positive way,” Dr. Mahulikar explained.

When outcome was analyzed based on status semiology on initial presentation, poor outcome was seen in 16 of the 37 patients (43%) with CPSE (P = .04); 9 of 48 patients (19%) with generalized convulsive status epilepticus, all patients with myoclonic status epilepticus (n = 2), and 3 of 9 (33%) who had NCSE (P less than .01). The type of status epilepticus was unknown for four patients, one of whom had an unknown outcome. NCSE at any time during the hospital course (including at presentation) was seen in 31 patients. Of these, 14 (45%) had a poor outcome (P = .02).

The mean number of ventilator days was higher in patients with NCSE than in those without NCSE (9.2 vs. 1.6 days; P = .0001) and also higher in those with new-onset seizures than in those without (7.8 vs. 2.9 days; P = .001). Analysis of methods of treatments revealed that only 7 of 31 (22.5%) patients who received adequate benzodiazepine dosing had poor outcomes (P = .2247). “The take-home message is to diagnose NCSE as early as possible because I think some patients who come in initially we may attribute to metabolic or autoimmune causes, and we tend to miss NCSE sometimes due to delay in diagnosis of NCSE,” Dr. Mahulikar said. “Treat aggressively at the beginning.”

He reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – Predictors of poor outcomes in patients with status epilepticus admitted to the neurointensive care unit include complex partial status epilepticus (CPSE), refractory status epilepticus, or the development of nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) at any time during the hospital course, according to results from a single-center study.

“Not a lot of data exist as to what predicts the poor outcomes and what’s known about the outcome in patients with status epilepticus,” lead study author Advait Mahulikar, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. To find out, he and his associates retrospectively reviewed data from 100 patients with status epilepticus who were admitted to the neurointensive care unit at Detroit Medical Center from November 2013 to January 2016. Variables of interest included patient demographics, initial presentation, refractoriness to treatment, presence or absence of underlying etiology, past history of epilepsy, and use of benzodiazepines on admission. Another variable of interest was NCSE, either from initial presentation or developed during the course of convulsive status epilepticus. A good outcome was defined as a Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) score of 4 or 5, and a poor outcome was defined as a GOS score of 1-3.

Neither age nor gender predicted poor outcome, and there was no difference in outcome between structural and nonstructural causes of status epilepticus. However, prior history of epilepsy was a strong negative predictor of poor outcome. In fact, only 14 of 70 patients (20%) with a prior history of epilepsy had a poor outcome (P less than .01). “The theory is that [these patients] were already on treatment for epilepsy in the past and that affected their outcome in a positive way,” Dr. Mahulikar explained.

When outcome was analyzed based on status semiology on initial presentation, poor outcome was seen in 16 of the 37 patients (43%) with CPSE (P = .04); 9 of 48 patients (19%) with generalized convulsive status epilepticus, all patients with myoclonic status epilepticus (n = 2), and 3 of 9 (33%) who had NCSE (P less than .01). The type of status epilepticus was unknown for four patients, one of whom had an unknown outcome. NCSE at any time during the hospital course (including at presentation) was seen in 31 patients. Of these, 14 (45%) had a poor outcome (P = .02).

The mean number of ventilator days was higher in patients with NCSE than in those without NCSE (9.2 vs. 1.6 days; P = .0001) and also higher in those with new-onset seizures than in those without (7.8 vs. 2.9 days; P = .001). Analysis of methods of treatments revealed that only 7 of 31 (22.5%) patients who received adequate benzodiazepine dosing had poor outcomes (P = .2247). “The take-home message is to diagnose NCSE as early as possible because I think some patients who come in initially we may attribute to metabolic or autoimmune causes, and we tend to miss NCSE sometimes due to delay in diagnosis of NCSE,” Dr. Mahulikar said. “Treat aggressively at the beginning.”

He reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – Predictors of poor outcomes in patients with status epilepticus admitted to the neurointensive care unit include complex partial status epilepticus (CPSE), refractory status epilepticus, or the development of nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) at any time during the hospital course, according to results from a single-center study.

“Not a lot of data exist as to what predicts the poor outcomes and what’s known about the outcome in patients with status epilepticus,” lead study author Advait Mahulikar, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. To find out, he and his associates retrospectively reviewed data from 100 patients with status epilepticus who were admitted to the neurointensive care unit at Detroit Medical Center from November 2013 to January 2016. Variables of interest included patient demographics, initial presentation, refractoriness to treatment, presence or absence of underlying etiology, past history of epilepsy, and use of benzodiazepines on admission. Another variable of interest was NCSE, either from initial presentation or developed during the course of convulsive status epilepticus. A good outcome was defined as a Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) score of 4 or 5, and a poor outcome was defined as a GOS score of 1-3.

Neither age nor gender predicted poor outcome, and there was no difference in outcome between structural and nonstructural causes of status epilepticus. However, prior history of epilepsy was a strong negative predictor of poor outcome. In fact, only 14 of 70 patients (20%) with a prior history of epilepsy had a poor outcome (P less than .01). “The theory is that [these patients] were already on treatment for epilepsy in the past and that affected their outcome in a positive way,” Dr. Mahulikar explained.

When outcome was analyzed based on status semiology on initial presentation, poor outcome was seen in 16 of the 37 patients (43%) with CPSE (P = .04); 9 of 48 patients (19%) with generalized convulsive status epilepticus, all patients with myoclonic status epilepticus (n = 2), and 3 of 9 (33%) who had NCSE (P less than .01). The type of status epilepticus was unknown for four patients, one of whom had an unknown outcome. NCSE at any time during the hospital course (including at presentation) was seen in 31 patients. Of these, 14 (45%) had a poor outcome (P = .02).

The mean number of ventilator days was higher in patients with NCSE than in those without NCSE (9.2 vs. 1.6 days; P = .0001) and also higher in those with new-onset seizures than in those without (7.8 vs. 2.9 days; P = .001). Analysis of methods of treatments revealed that only 7 of 31 (22.5%) patients who received adequate benzodiazepine dosing had poor outcomes (P = .2247). “The take-home message is to diagnose NCSE as early as possible because I think some patients who come in initially we may attribute to metabolic or autoimmune causes, and we tend to miss NCSE sometimes due to delay in diagnosis of NCSE,” Dr. Mahulikar said. “Treat aggressively at the beginning.”

He reported having no financial disclosures.

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Poor outcome was seen in 43% of patients with CPSE, 19% with generalized convulsive status epilepticus, all patients with myoclonic status epilepticus, and in 33% of those who had NCSE.

Data source: A retrospective review of data from 100 patients with status epilepticus who were admitted to the neurointensive care unit at Detroit Medical Center from November 2013 to January 2016.

Disclosures: Dr. Mahulikar reported having no financial disclosures.

Reasons for noncompliance to ketogenic diet explored

HOUSTON – More than one-third of children discontinued the ketogenic diet prior to completion of a 3-month trial because of reported difficulty, a single-center study showed.

The findings underscore the importance of carefully screening patients and their families prior to initiating the ketogenic diet, lead author Gogi Kumar, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “We always talk about how and when the ketogenic diet should be used, but we don’t talk about the barriers to continuing the diet, like the socioeconomic aspects that determine the feasibility of continuing the diet,” said Dr. Kumar, a pediatric neurologist at Dayton (Ohio) Children’s Hospital. “If it’s a single mom who has two jobs and has a kid with intractable epilepsy, she cannot do it because ketogenic diets are complex and very intense. If the child has a gastrostomy tube and you can feed them a formula it might work, but then you have to bring them in for multiple lab tests. The family has to be very committed. They have to have resources.”

The mean age of study participants was 7.4 years, and feeding was accomplished orally in 43%, by tube in 40%, and both routes in 17%. Of the patients who were started on a ketogenic diet, 57% continued on the diet for more than 3 months. Overall, 55% of patients experienced at least a 50% reduction in seizures, while 45% experienced less than a 50% reduction in seizures.

Dr. Kumar went on to report that 15 patients (43%) discontinued the diet before the 3-month trial period. Of these 15 patients, 3 had adverse effects after initiation of the diet and the remaining 12 reported stopping the diet because of difficulty, 1 of whom also reported cost as a barrier. Of the 12 patients who stopped the diet because of difficulty, 8 were on the classic ketogenic diet and 4 were on other diet therapies. All were oral eaters and 50% lived in a single-parent household or had shared parenting in multiple households with poor communication. The remaining 50% had married parents, of whom 25% were teenagers who did not want to commit to the diet and 25% were children with parents who found the diet difficult. Of families who discontinued the diet early, 58% of parents had difficulty learning how to manage the complexity of the ketogenic diet and/or had limited cooking skills.

“Before you try someone on the ketogenic diet, we should evaluate the family’s educational level, their commitment, and their support systems so that we can help them overcome any barriers. It is important to have social workers as part of the ketogenic diet team to help with the process,” Dr. Kumar said. She reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – More than one-third of children discontinued the ketogenic diet prior to completion of a 3-month trial because of reported difficulty, a single-center study showed.

The findings underscore the importance of carefully screening patients and their families prior to initiating the ketogenic diet, lead author Gogi Kumar, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “We always talk about how and when the ketogenic diet should be used, but we don’t talk about the barriers to continuing the diet, like the socioeconomic aspects that determine the feasibility of continuing the diet,” said Dr. Kumar, a pediatric neurologist at Dayton (Ohio) Children’s Hospital. “If it’s a single mom who has two jobs and has a kid with intractable epilepsy, she cannot do it because ketogenic diets are complex and very intense. If the child has a gastrostomy tube and you can feed them a formula it might work, but then you have to bring them in for multiple lab tests. The family has to be very committed. They have to have resources.”

The mean age of study participants was 7.4 years, and feeding was accomplished orally in 43%, by tube in 40%, and both routes in 17%. Of the patients who were started on a ketogenic diet, 57% continued on the diet for more than 3 months. Overall, 55% of patients experienced at least a 50% reduction in seizures, while 45% experienced less than a 50% reduction in seizures.

Dr. Kumar went on to report that 15 patients (43%) discontinued the diet before the 3-month trial period. Of these 15 patients, 3 had adverse effects after initiation of the diet and the remaining 12 reported stopping the diet because of difficulty, 1 of whom also reported cost as a barrier. Of the 12 patients who stopped the diet because of difficulty, 8 were on the classic ketogenic diet and 4 were on other diet therapies. All were oral eaters and 50% lived in a single-parent household or had shared parenting in multiple households with poor communication. The remaining 50% had married parents, of whom 25% were teenagers who did not want to commit to the diet and 25% were children with parents who found the diet difficult. Of families who discontinued the diet early, 58% of parents had difficulty learning how to manage the complexity of the ketogenic diet and/or had limited cooking skills.

“Before you try someone on the ketogenic diet, we should evaluate the family’s educational level, their commitment, and their support systems so that we can help them overcome any barriers. It is important to have social workers as part of the ketogenic diet team to help with the process,” Dr. Kumar said. She reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – More than one-third of children discontinued the ketogenic diet prior to completion of a 3-month trial because of reported difficulty, a single-center study showed.

The findings underscore the importance of carefully screening patients and their families prior to initiating the ketogenic diet, lead author Gogi Kumar, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “We always talk about how and when the ketogenic diet should be used, but we don’t talk about the barriers to continuing the diet, like the socioeconomic aspects that determine the feasibility of continuing the diet,” said Dr. Kumar, a pediatric neurologist at Dayton (Ohio) Children’s Hospital. “If it’s a single mom who has two jobs and has a kid with intractable epilepsy, she cannot do it because ketogenic diets are complex and very intense. If the child has a gastrostomy tube and you can feed them a formula it might work, but then you have to bring them in for multiple lab tests. The family has to be very committed. They have to have resources.”

The mean age of study participants was 7.4 years, and feeding was accomplished orally in 43%, by tube in 40%, and both routes in 17%. Of the patients who were started on a ketogenic diet, 57% continued on the diet for more than 3 months. Overall, 55% of patients experienced at least a 50% reduction in seizures, while 45% experienced less than a 50% reduction in seizures.

Dr. Kumar went on to report that 15 patients (43%) discontinued the diet before the 3-month trial period. Of these 15 patients, 3 had adverse effects after initiation of the diet and the remaining 12 reported stopping the diet because of difficulty, 1 of whom also reported cost as a barrier. Of the 12 patients who stopped the diet because of difficulty, 8 were on the classic ketogenic diet and 4 were on other diet therapies. All were oral eaters and 50% lived in a single-parent household or had shared parenting in multiple households with poor communication. The remaining 50% had married parents, of whom 25% were teenagers who did not want to commit to the diet and 25% were children with parents who found the diet difficult. Of families who discontinued the diet early, 58% of parents had difficulty learning how to manage the complexity of the ketogenic diet and/or had limited cooking skills.

“Before you try someone on the ketogenic diet, we should evaluate the family’s educational level, their commitment, and their support systems so that we can help them overcome any barriers. It is important to have social workers as part of the ketogenic diet team to help with the process,” Dr. Kumar said. She reported having no financial disclosures.

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: More than one-third of children (43%) discontinued the ketogenic diet before the end of a 3-month trial period.

Data source: A prospective evaluation of 64 patients with intractable epilepsy and their families who were educated about the ketogenic diet at Dayton Children’s Hospital.

Disclosures: Dr. Kumar reported having no financial disclosures.

First visit for tuberous sclerosis complex comes months before diagnosis

HOUSTON – Many patients who eventually receive a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis complex present with related complaints for months, or even years, before their condition is recognized and correctly diagnosed, according to a retrospective study.

The study, presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, found that patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) first sought care for TSC-related conditions an average of 7 months before they were diagnosed with the condition. Younger patients received the correct diagnosis sooner than did older patients: Treatment for TSC-related conditions preceded the diagnosis for 3.4 months for those aged 4 years or younger, compared with 5.5 months for those aged 25-29 years, and 21 months for those aged 80 years or older.

Seizures and skin conditions were common initial diagnoses among TSC patients, with 27% of patients aged 0-4 years being diagnosed with seizures prior to receiving their TSC diagnosis. The likelihood of prediagnosis visits for seizures decreased to less than 6% for older age groups. Seizures remained common post-TSC diagnosis among younger patients, with 38% of patients aged 0-4 years having any seizure diagnosis, while the rate fell through the lifespan to zero for those aged 80 or older.

James Wheless, MD, and his associates examined claims and enrollment data records from 2,163 patients diagnosed with TSC between January 2000 and December 2011. In addition to the frequently-diagnosed seizures seen in many TSC patients, skin conditions were diagnosed in 16.3% of patients before their eventual TSC diagnosis.

Other early conditions associated with TSC, according to the study’s multivariable analysis, included bone cysts, anxiety, and ADHD. However, wrote Dr. Wheless, chief of the department of pediatric neurology at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, and his coauthors, “at any point in time, patients with seizures were 2.9 times more likely to receive a TSC diagnosis than patients without seizures.”

The study was drawn from U.S. health plan databases that included both commercial and Medicare Advantage enrollees, and included patients through the lifespan. The date of the first recorded TSC diagnosis was the index date, and patients had to have at least 12 months of prediagnosis health plan enrollment to be included, or 6 months for those aged 2 years or younger. Data were collected for all pre-index visits (some of which stretched back to 1993), and for visits in the 12 months after the index visit.

The proportion of female patients ranged from fewer than half for those under 15 years (0-4 years, 46%; 5-9 years, 43%; 10-14 years, 48%) to 64% for those aged 80 years or older (P less than .001).

Dr. Wheless and his coauthors noted that the claims data used for the analysis “may not adequately capture clinical characteristics such as disease severity,” and that some patient data may have been lost if patients were disenrolled for periods of time during the study period.

The findings of the poster may prompt clinicians to consider TSC as a diagnosis; though rare, occurring in 1-2 per 6,000 live births, it’s thought to be an underrecognized disease entity. “Understanding the initial diagnoses experienced by TSC patients may help lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment of TSC,” Dr. Wheless and his coauthors wrote.

Novartis funded the study. Four study authors are employed by Optum, and one is employed by Novartis.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – Many patients who eventually receive a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis complex present with related complaints for months, or even years, before their condition is recognized and correctly diagnosed, according to a retrospective study.

The study, presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, found that patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) first sought care for TSC-related conditions an average of 7 months before they were diagnosed with the condition. Younger patients received the correct diagnosis sooner than did older patients: Treatment for TSC-related conditions preceded the diagnosis for 3.4 months for those aged 4 years or younger, compared with 5.5 months for those aged 25-29 years, and 21 months for those aged 80 years or older.

Seizures and skin conditions were common initial diagnoses among TSC patients, with 27% of patients aged 0-4 years being diagnosed with seizures prior to receiving their TSC diagnosis. The likelihood of prediagnosis visits for seizures decreased to less than 6% for older age groups. Seizures remained common post-TSC diagnosis among younger patients, with 38% of patients aged 0-4 years having any seizure diagnosis, while the rate fell through the lifespan to zero for those aged 80 or older.

James Wheless, MD, and his associates examined claims and enrollment data records from 2,163 patients diagnosed with TSC between January 2000 and December 2011. In addition to the frequently-diagnosed seizures seen in many TSC patients, skin conditions were diagnosed in 16.3% of patients before their eventual TSC diagnosis.

Other early conditions associated with TSC, according to the study’s multivariable analysis, included bone cysts, anxiety, and ADHD. However, wrote Dr. Wheless, chief of the department of pediatric neurology at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, and his coauthors, “at any point in time, patients with seizures were 2.9 times more likely to receive a TSC diagnosis than patients without seizures.”

The study was drawn from U.S. health plan databases that included both commercial and Medicare Advantage enrollees, and included patients through the lifespan. The date of the first recorded TSC diagnosis was the index date, and patients had to have at least 12 months of prediagnosis health plan enrollment to be included, or 6 months for those aged 2 years or younger. Data were collected for all pre-index visits (some of which stretched back to 1993), and for visits in the 12 months after the index visit.

The proportion of female patients ranged from fewer than half for those under 15 years (0-4 years, 46%; 5-9 years, 43%; 10-14 years, 48%) to 64% for those aged 80 years or older (P less than .001).

Dr. Wheless and his coauthors noted that the claims data used for the analysis “may not adequately capture clinical characteristics such as disease severity,” and that some patient data may have been lost if patients were disenrolled for periods of time during the study period.

The findings of the poster may prompt clinicians to consider TSC as a diagnosis; though rare, occurring in 1-2 per 6,000 live births, it’s thought to be an underrecognized disease entity. “Understanding the initial diagnoses experienced by TSC patients may help lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment of TSC,” Dr. Wheless and his coauthors wrote.

Novartis funded the study. Four study authors are employed by Optum, and one is employed by Novartis.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – Many patients who eventually receive a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis complex present with related complaints for months, or even years, before their condition is recognized and correctly diagnosed, according to a retrospective study.

The study, presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, found that patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) first sought care for TSC-related conditions an average of 7 months before they were diagnosed with the condition. Younger patients received the correct diagnosis sooner than did older patients: Treatment for TSC-related conditions preceded the diagnosis for 3.4 months for those aged 4 years or younger, compared with 5.5 months for those aged 25-29 years, and 21 months for those aged 80 years or older.

Seizures and skin conditions were common initial diagnoses among TSC patients, with 27% of patients aged 0-4 years being diagnosed with seizures prior to receiving their TSC diagnosis. The likelihood of prediagnosis visits for seizures decreased to less than 6% for older age groups. Seizures remained common post-TSC diagnosis among younger patients, with 38% of patients aged 0-4 years having any seizure diagnosis, while the rate fell through the lifespan to zero for those aged 80 or older.

James Wheless, MD, and his associates examined claims and enrollment data records from 2,163 patients diagnosed with TSC between January 2000 and December 2011. In addition to the frequently-diagnosed seizures seen in many TSC patients, skin conditions were diagnosed in 16.3% of patients before their eventual TSC diagnosis.

Other early conditions associated with TSC, according to the study’s multivariable analysis, included bone cysts, anxiety, and ADHD. However, wrote Dr. Wheless, chief of the department of pediatric neurology at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, and his coauthors, “at any point in time, patients with seizures were 2.9 times more likely to receive a TSC diagnosis than patients without seizures.”

The study was drawn from U.S. health plan databases that included both commercial and Medicare Advantage enrollees, and included patients through the lifespan. The date of the first recorded TSC diagnosis was the index date, and patients had to have at least 12 months of prediagnosis health plan enrollment to be included, or 6 months for those aged 2 years or younger. Data were collected for all pre-index visits (some of which stretched back to 1993), and for visits in the 12 months after the index visit.

The proportion of female patients ranged from fewer than half for those under 15 years (0-4 years, 46%; 5-9 years, 43%; 10-14 years, 48%) to 64% for those aged 80 years or older (P less than .001).

Dr. Wheless and his coauthors noted that the claims data used for the analysis “may not adequately capture clinical characteristics such as disease severity,” and that some patient data may have been lost if patients were disenrolled for periods of time during the study period.

The findings of the poster may prompt clinicians to consider TSC as a diagnosis; though rare, occurring in 1-2 per 6,000 live births, it’s thought to be an underrecognized disease entity. “Understanding the initial diagnoses experienced by TSC patients may help lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment of TSC,” Dr. Wheless and his coauthors wrote.

Novartis funded the study. Four study authors are employed by Optum, and one is employed by Novartis.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

FROM AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients were seen an average of 6.9 months before they received their TSC diagnosis.

Data source: Retrospective review of claims and enrollment data from 2,163 patients with tuberous sclerosis.

Disclosures: Novartis funded the study. Four study authors are employed by Optum; one is employed by Novartis.

Machine learning beats clinical prediction of temporal lobe epilepsy surgery outcomes

HOUSTON – A machine learning interpretation of presurgical MRI studies did a better job of predicting which patients would have a successful outcome after anterior temporal lobectomy for temporal lobe epilepsy than did commonly-used clinical indicators in a prospective cohort study.

Xiaosong He, PhD, and his associates used two different machine learning classification methods to find two markers for thalamocortical connectedness that best predicted a good surgical outcome for temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) in a small sample of patients. They presented their findings during a poster session of the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

After selecting a variety of possible predictors and building a model using resting state functional MRI (rsfMRI) data from 48 patients, the investigators then validated the prediction accuracies with rsfMRI data from 8 patients.

In predicting which TLE patients would have a good surgical outcome, models built with machine learning techniques using rsfMRI functional connectivity values had sensitivity ranging from 80% to 89% and specificity ranging from 52% to 57%. By comparison, models using clinical predictors only had sensitivity of 66% to 83% and specificity of 29% to 33%.

Dr. He and his coauthors dichotomized the surgical outcome for 56 patients who underwent TLE surgery into good outcome (n = 35) for those achieving and Engel class I and poor outcome (n = 21, class II-IV) at 1 year post surgery. All patients had a 5-minute rsfMRI scan before surgery.

MRI has been helpful in elucidating the importance of thalamocortical network pathology in TLE. Dr. He and his associates had previously used rsfMRI to examine the strength of functional connectivity between thalamic regions and their corresponding cortical regions in patients with TLE. Analysis of rsfMRI data of “both the left and right TLE groups showed that compared to controls there was a pattern of decreased thalamocortical [functional connectivity] in multiple thalamic segments,” wrote Dr. He and his collaborators (Epilepsia. 2015;56[10]:1571-9).

For the validation cohort, the two measures of connectedness found most predictive of a good surgical outcome were degree centrality and eigenvector centrality. In the graph theory and network analysis used in mapping functional connectivity, centrality refers to how highly connected one node, or data point, is to other data.

In the present study, the investigators used the Automated Anatomical Labeling cortical parcellation map to identify 45 cortical regions of interest per hemisphere, for a total of 90 cortical regions. They built a matrix with five topological parameters (global efficiency, global clustering coefficient, degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and eigenvector centrality) and the 90 cortical regions, yielding 272 variables. When nine commonly-used clinical predictors of surgical outcome (age, gender, handedness, laterality of TLE, epilepsy onset age and duration, seizure focality, interictal-spike type, and the presence of hippocampal sclerosis) were included, the model was made up of 281 variables.

The investigators used two different machine learning classification methods, called support vector machine and random forest, to build models that included various combinations of the 281 variables based on data from the initial 48 patients. The models were then tested with data from the remaining 8 patients.

Of the 35 patients with a good outcome, 18 had a left-sided epileptogenic temporal lobe; for the 21 patients with a poor outcome, the left temporal lobe was epileptogenic in 8. The mean age was similar for both groups: 41.25 years in those with good outcome, and 38.58 years in those with a poor outcome. Age at epilepsy onset also was similar, with each group having had epilepsy for about 17 years at the time of surgery. A total of 15 of the 20 patients with good outcome had seizure focality, compared with 10 of the 11 with poor outcome. Of those with a good outcome, 29 had an ipsilateral interactive spike, while 15 of those with poor outcomes had an ipsilateral interactive spike.

Since the random forest model best predicted surgical outcomes in the small sample size tested, the investigators plan to further fine-tune the random forest parameters to increase the robustness of their model.

Dr. He reported no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – A machine learning interpretation of presurgical MRI studies did a better job of predicting which patients would have a successful outcome after anterior temporal lobectomy for temporal lobe epilepsy than did commonly-used clinical indicators in a prospective cohort study.

Xiaosong He, PhD, and his associates used two different machine learning classification methods to find two markers for thalamocortical connectedness that best predicted a good surgical outcome for temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) in a small sample of patients. They presented their findings during a poster session of the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

After selecting a variety of possible predictors and building a model using resting state functional MRI (rsfMRI) data from 48 patients, the investigators then validated the prediction accuracies with rsfMRI data from 8 patients.

In predicting which TLE patients would have a good surgical outcome, models built with machine learning techniques using rsfMRI functional connectivity values had sensitivity ranging from 80% to 89% and specificity ranging from 52% to 57%. By comparison, models using clinical predictors only had sensitivity of 66% to 83% and specificity of 29% to 33%.

Dr. He and his coauthors dichotomized the surgical outcome for 56 patients who underwent TLE surgery into good outcome (n = 35) for those achieving and Engel class I and poor outcome (n = 21, class II-IV) at 1 year post surgery. All patients had a 5-minute rsfMRI scan before surgery.

MRI has been helpful in elucidating the importance of thalamocortical network pathology in TLE. Dr. He and his associates had previously used rsfMRI to examine the strength of functional connectivity between thalamic regions and their corresponding cortical regions in patients with TLE. Analysis of rsfMRI data of “both the left and right TLE groups showed that compared to controls there was a pattern of decreased thalamocortical [functional connectivity] in multiple thalamic segments,” wrote Dr. He and his collaborators (Epilepsia. 2015;56[10]:1571-9).

For the validation cohort, the two measures of connectedness found most predictive of a good surgical outcome were degree centrality and eigenvector centrality. In the graph theory and network analysis used in mapping functional connectivity, centrality refers to how highly connected one node, or data point, is to other data.

In the present study, the investigators used the Automated Anatomical Labeling cortical parcellation map to identify 45 cortical regions of interest per hemisphere, for a total of 90 cortical regions. They built a matrix with five topological parameters (global efficiency, global clustering coefficient, degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and eigenvector centrality) and the 90 cortical regions, yielding 272 variables. When nine commonly-used clinical predictors of surgical outcome (age, gender, handedness, laterality of TLE, epilepsy onset age and duration, seizure focality, interictal-spike type, and the presence of hippocampal sclerosis) were included, the model was made up of 281 variables.

The investigators used two different machine learning classification methods, called support vector machine and random forest, to build models that included various combinations of the 281 variables based on data from the initial 48 patients. The models were then tested with data from the remaining 8 patients.

Of the 35 patients with a good outcome, 18 had a left-sided epileptogenic temporal lobe; for the 21 patients with a poor outcome, the left temporal lobe was epileptogenic in 8. The mean age was similar for both groups: 41.25 years in those with good outcome, and 38.58 years in those with a poor outcome. Age at epilepsy onset also was similar, with each group having had epilepsy for about 17 years at the time of surgery. A total of 15 of the 20 patients with good outcome had seizure focality, compared with 10 of the 11 with poor outcome. Of those with a good outcome, 29 had an ipsilateral interactive spike, while 15 of those with poor outcomes had an ipsilateral interactive spike.

Since the random forest model best predicted surgical outcomes in the small sample size tested, the investigators plan to further fine-tune the random forest parameters to increase the robustness of their model.

Dr. He reported no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – A machine learning interpretation of presurgical MRI studies did a better job of predicting which patients would have a successful outcome after anterior temporal lobectomy for temporal lobe epilepsy than did commonly-used clinical indicators in a prospective cohort study.

Xiaosong He, PhD, and his associates used two different machine learning classification methods to find two markers for thalamocortical connectedness that best predicted a good surgical outcome for temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) in a small sample of patients. They presented their findings during a poster session of the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

After selecting a variety of possible predictors and building a model using resting state functional MRI (rsfMRI) data from 48 patients, the investigators then validated the prediction accuracies with rsfMRI data from 8 patients.

In predicting which TLE patients would have a good surgical outcome, models built with machine learning techniques using rsfMRI functional connectivity values had sensitivity ranging from 80% to 89% and specificity ranging from 52% to 57%. By comparison, models using clinical predictors only had sensitivity of 66% to 83% and specificity of 29% to 33%.

Dr. He and his coauthors dichotomized the surgical outcome for 56 patients who underwent TLE surgery into good outcome (n = 35) for those achieving and Engel class I and poor outcome (n = 21, class II-IV) at 1 year post surgery. All patients had a 5-minute rsfMRI scan before surgery.

MRI has been helpful in elucidating the importance of thalamocortical network pathology in TLE. Dr. He and his associates had previously used rsfMRI to examine the strength of functional connectivity between thalamic regions and their corresponding cortical regions in patients with TLE. Analysis of rsfMRI data of “both the left and right TLE groups showed that compared to controls there was a pattern of decreased thalamocortical [functional connectivity] in multiple thalamic segments,” wrote Dr. He and his collaborators (Epilepsia. 2015;56[10]:1571-9).

For the validation cohort, the two measures of connectedness found most predictive of a good surgical outcome were degree centrality and eigenvector centrality. In the graph theory and network analysis used in mapping functional connectivity, centrality refers to how highly connected one node, or data point, is to other data.

In the present study, the investigators used the Automated Anatomical Labeling cortical parcellation map to identify 45 cortical regions of interest per hemisphere, for a total of 90 cortical regions. They built a matrix with five topological parameters (global efficiency, global clustering coefficient, degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and eigenvector centrality) and the 90 cortical regions, yielding 272 variables. When nine commonly-used clinical predictors of surgical outcome (age, gender, handedness, laterality of TLE, epilepsy onset age and duration, seizure focality, interictal-spike type, and the presence of hippocampal sclerosis) were included, the model was made up of 281 variables.

The investigators used two different machine learning classification methods, called support vector machine and random forest, to build models that included various combinations of the 281 variables based on data from the initial 48 patients. The models were then tested with data from the remaining 8 patients.

Of the 35 patients with a good outcome, 18 had a left-sided epileptogenic temporal lobe; for the 21 patients with a poor outcome, the left temporal lobe was epileptogenic in 8. The mean age was similar for both groups: 41.25 years in those with good outcome, and 38.58 years in those with a poor outcome. Age at epilepsy onset also was similar, with each group having had epilepsy for about 17 years at the time of surgery. A total of 15 of the 20 patients with good outcome had seizure focality, compared with 10 of the 11 with poor outcome. Of those with a good outcome, 29 had an ipsilateral interactive spike, while 15 of those with poor outcomes had an ipsilateral interactive spike.

Since the random forest model best predicted surgical outcomes in the small sample size tested, the investigators plan to further fine-tune the random forest parameters to increase the robustness of their model.

Dr. He reported no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Models built with machine learning techniques using resting state fMRI functional connectivity values had sensitivity ranging from 80% to 89% and specificity ranging from 52% to 57%.

Data source: A prospective study of 56 patients with temporal lobe epilepsy.

Disclosures: Dr. He reported no conflicts of interest.

Add-on fenfluramine reduces seizure frequency in Dravet syndrome

HOUSTON – Low-dose fenfluramine was found to reduce seizures significantly among a small cohort with Dravet syndrome without the appearance of valvular abnormalities or pulmonary hypertension, according to a prospective study presented at a poster session of the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Six of nine Dravet syndrome (DS) patients (66%) had at least a 50% reduction in major motor seizure frequency for at least 90% of the period during which they took fenfluramine. Five of the nine DS patients (56%) experienced a reduction in major motor seizure frequency of 75% or more for at least 60% of the median 1.9 years they were on fenfluramine.

According to lead author An-Sofie Schoonjans, MD, and her collaborators, the results suggest that “low-dose fenfluramine provides significant improvement in seizure frequency while being generally well tolerated in DS patients.”

The study criteria included patients aged 6 months to 50 years who had a DS diagnosis; enrollees ranged in age from 1.2 to 29.8 years when starting fenfluramine. Though criteria allowed enrollment of patients with and without a mutation in the SCN1A gene, all participants did have a de novo mutation of the SCN1A gene, according to Dr. Schoonjans of the department of pediatric neurology at Antwerp (Belgium) University Hospital and her colleagues. They wrote that mutations in the gene, which encodes the alpha subunit of type 1 voltage-gated sodium channels, are found in about 80% of DS patients.

During the 3-month run-in period that began the study, patients had a median seizure frequency of 15 seizures per month. Patients remained on their baseline antiepilepsy regimen during the run-in period and throughout the study, with fenfluramine used as add-on therapy. At baseline, all patients were taking valproic acid and at least one other antiepileptic medication; three patients were taking four medications and one was taking five medications. Three patients also had vagal nerve stimulators with stable settings.

Throughout the study period, patients or their caregivers kept a seizure diary, recording major motor seizures. Those keeping the diary were instructed to record all tonic-clonic, tonic, atonic, and myoclonic seizures lasting more than 30 seconds.

Three months after beginning treatment, the study population’s median seizure frequency fell to 2.0 per month (–84%). Frequency fell further during the first year, to 1.0 per month (–79%; a smaller percent reduction because data were not available for this time period for the patient with the highest seizure frequency). For the total treatment period, the median seizure frequency was 1.9 per month (–76%). The reduction in seizure frequency was statistically significant at all time points (P less than .05; compared with baseline).

Fenfluramine was generally well-tolerated. Five patients experienced somnolence, and four had loss of appetite.

To track cardiovascular safety, all patients had echocardiographs at baseline and every 3 months during the first year of treatment. Echocardiographs were performed every 6 months during the second year, and annually thereafter. One patient had systolic dysfunction characterized by a reduced ejection fraction (53%) and fractional shortening (26%), findings of “no clinical significance,” according to Dr. Schoonjans and her colleagues.

Fenfluramine was part of an oral weight loss drug combination, along with phentermine. The combo, known as “fen-phen,” was associated with increased rates of pulmonary hypertension and valve disease, particularly aortic valve thickening and regurgitation. It was withdrawn from the market in 1997. Though pulmonary hypertension would frequently resolve after discontinuing fen-phen, not all patients with valvulopathy experienced resolution, and case reports of patients with the aortic valve thickening typically seen with fenfluramine are still surfacing many years after the drug’s discontinuation (e.g., Tex Heart Inst J. 2011;38[5]:581-3).

Fenfluramine was typically given at doses up to 60 mg when used with phentermine for weight loss. The dosing for Dravet syndrome patients in this study was much lower and weight based, ranging from 0.1 to 1.0 mg/kg per day, with a maximum permitted dose of 20 mg/day.

Fenfluramine is a serotonin releaser, and serotonin is known to modulate the action of voltage-gated sodium channels. However, the exact mechanism by which the drug reduces seizure frequency is not known. Clinical trials are underway in the United States for both DS and Lennox Gastaut epilepsy, and fenfluramine has been granted orphan drug status in the United States and Europe, according to an announcement from Zogenix, the drug’s manufacturer.

The study was funded by Zogenix, which holds a Royal Decree to dispense the drug under the study conditions in Belgium, where the study took place. Zogenix also funded writing and editorial assistance for the poster presentation.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – Low-dose fenfluramine was found to reduce seizures significantly among a small cohort with Dravet syndrome without the appearance of valvular abnormalities or pulmonary hypertension, according to a prospective study presented at a poster session of the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Six of nine Dravet syndrome (DS) patients (66%) had at least a 50% reduction in major motor seizure frequency for at least 90% of the period during which they took fenfluramine. Five of the nine DS patients (56%) experienced a reduction in major motor seizure frequency of 75% or more for at least 60% of the median 1.9 years they were on fenfluramine.

According to lead author An-Sofie Schoonjans, MD, and her collaborators, the results suggest that “low-dose fenfluramine provides significant improvement in seizure frequency while being generally well tolerated in DS patients.”

The study criteria included patients aged 6 months to 50 years who had a DS diagnosis; enrollees ranged in age from 1.2 to 29.8 years when starting fenfluramine. Though criteria allowed enrollment of patients with and without a mutation in the SCN1A gene, all participants did have a de novo mutation of the SCN1A gene, according to Dr. Schoonjans of the department of pediatric neurology at Antwerp (Belgium) University Hospital and her colleagues. They wrote that mutations in the gene, which encodes the alpha subunit of type 1 voltage-gated sodium channels, are found in about 80% of DS patients.

During the 3-month run-in period that began the study, patients had a median seizure frequency of 15 seizures per month. Patients remained on their baseline antiepilepsy regimen during the run-in period and throughout the study, with fenfluramine used as add-on therapy. At baseline, all patients were taking valproic acid and at least one other antiepileptic medication; three patients were taking four medications and one was taking five medications. Three patients also had vagal nerve stimulators with stable settings.

Throughout the study period, patients or their caregivers kept a seizure diary, recording major motor seizures. Those keeping the diary were instructed to record all tonic-clonic, tonic, atonic, and myoclonic seizures lasting more than 30 seconds.

Three months after beginning treatment, the study population’s median seizure frequency fell to 2.0 per month (–84%). Frequency fell further during the first year, to 1.0 per month (–79%; a smaller percent reduction because data were not available for this time period for the patient with the highest seizure frequency). For the total treatment period, the median seizure frequency was 1.9 per month (–76%). The reduction in seizure frequency was statistically significant at all time points (P less than .05; compared with baseline).

Fenfluramine was generally well-tolerated. Five patients experienced somnolence, and four had loss of appetite.

To track cardiovascular safety, all patients had echocardiographs at baseline and every 3 months during the first year of treatment. Echocardiographs were performed every 6 months during the second year, and annually thereafter. One patient had systolic dysfunction characterized by a reduced ejection fraction (53%) and fractional shortening (26%), findings of “no clinical significance,” according to Dr. Schoonjans and her colleagues.

Fenfluramine was part of an oral weight loss drug combination, along with phentermine. The combo, known as “fen-phen,” was associated with increased rates of pulmonary hypertension and valve disease, particularly aortic valve thickening and regurgitation. It was withdrawn from the market in 1997. Though pulmonary hypertension would frequently resolve after discontinuing fen-phen, not all patients with valvulopathy experienced resolution, and case reports of patients with the aortic valve thickening typically seen with fenfluramine are still surfacing many years after the drug’s discontinuation (e.g., Tex Heart Inst J. 2011;38[5]:581-3).

Fenfluramine was typically given at doses up to 60 mg when used with phentermine for weight loss. The dosing for Dravet syndrome patients in this study was much lower and weight based, ranging from 0.1 to 1.0 mg/kg per day, with a maximum permitted dose of 20 mg/day.

Fenfluramine is a serotonin releaser, and serotonin is known to modulate the action of voltage-gated sodium channels. However, the exact mechanism by which the drug reduces seizure frequency is not known. Clinical trials are underway in the United States for both DS and Lennox Gastaut epilepsy, and fenfluramine has been granted orphan drug status in the United States and Europe, according to an announcement from Zogenix, the drug’s manufacturer.

The study was funded by Zogenix, which holds a Royal Decree to dispense the drug under the study conditions in Belgium, where the study took place. Zogenix also funded writing and editorial assistance for the poster presentation.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – Low-dose fenfluramine was found to reduce seizures significantly among a small cohort with Dravet syndrome without the appearance of valvular abnormalities or pulmonary hypertension, according to a prospective study presented at a poster session of the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Six of nine Dravet syndrome (DS) patients (66%) had at least a 50% reduction in major motor seizure frequency for at least 90% of the period during which they took fenfluramine. Five of the nine DS patients (56%) experienced a reduction in major motor seizure frequency of 75% or more for at least 60% of the median 1.9 years they were on fenfluramine.

According to lead author An-Sofie Schoonjans, MD, and her collaborators, the results suggest that “low-dose fenfluramine provides significant improvement in seizure frequency while being generally well tolerated in DS patients.”

The study criteria included patients aged 6 months to 50 years who had a DS diagnosis; enrollees ranged in age from 1.2 to 29.8 years when starting fenfluramine. Though criteria allowed enrollment of patients with and without a mutation in the SCN1A gene, all participants did have a de novo mutation of the SCN1A gene, according to Dr. Schoonjans of the department of pediatric neurology at Antwerp (Belgium) University Hospital and her colleagues. They wrote that mutations in the gene, which encodes the alpha subunit of type 1 voltage-gated sodium channels, are found in about 80% of DS patients.

During the 3-month run-in period that began the study, patients had a median seizure frequency of 15 seizures per month. Patients remained on their baseline antiepilepsy regimen during the run-in period and throughout the study, with fenfluramine used as add-on therapy. At baseline, all patients were taking valproic acid and at least one other antiepileptic medication; three patients were taking four medications and one was taking five medications. Three patients also had vagal nerve stimulators with stable settings.

Throughout the study period, patients or their caregivers kept a seizure diary, recording major motor seizures. Those keeping the diary were instructed to record all tonic-clonic, tonic, atonic, and myoclonic seizures lasting more than 30 seconds.

Three months after beginning treatment, the study population’s median seizure frequency fell to 2.0 per month (–84%). Frequency fell further during the first year, to 1.0 per month (–79%; a smaller percent reduction because data were not available for this time period for the patient with the highest seizure frequency). For the total treatment period, the median seizure frequency was 1.9 per month (–76%). The reduction in seizure frequency was statistically significant at all time points (P less than .05; compared with baseline).

Fenfluramine was generally well-tolerated. Five patients experienced somnolence, and four had loss of appetite.

To track cardiovascular safety, all patients had echocardiographs at baseline and every 3 months during the first year of treatment. Echocardiographs were performed every 6 months during the second year, and annually thereafter. One patient had systolic dysfunction characterized by a reduced ejection fraction (53%) and fractional shortening (26%), findings of “no clinical significance,” according to Dr. Schoonjans and her colleagues.

Fenfluramine was part of an oral weight loss drug combination, along with phentermine. The combo, known as “fen-phen,” was associated with increased rates of pulmonary hypertension and valve disease, particularly aortic valve thickening and regurgitation. It was withdrawn from the market in 1997. Though pulmonary hypertension would frequently resolve after discontinuing fen-phen, not all patients with valvulopathy experienced resolution, and case reports of patients with the aortic valve thickening typically seen with fenfluramine are still surfacing many years after the drug’s discontinuation (e.g., Tex Heart Inst J. 2011;38[5]:581-3).

Fenfluramine was typically given at doses up to 60 mg when used with phentermine for weight loss. The dosing for Dravet syndrome patients in this study was much lower and weight based, ranging from 0.1 to 1.0 mg/kg per day, with a maximum permitted dose of 20 mg/day.

Fenfluramine is a serotonin releaser, and serotonin is known to modulate the action of voltage-gated sodium channels. However, the exact mechanism by which the drug reduces seizure frequency is not known. Clinical trials are underway in the United States for both DS and Lennox Gastaut epilepsy, and fenfluramine has been granted orphan drug status in the United States and Europe, according to an announcement from Zogenix, the drug’s manufacturer.

The study was funded by Zogenix, which holds a Royal Decree to dispense the drug under the study conditions in Belgium, where the study took place. Zogenix also funded writing and editorial assistance for the poster presentation.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Six of nine patients (66%) had a reduction in seizure frequency of at least 50% for at least 90% of the time they were taking fenfluramine.

Data source: Prospective cohort study of nine patients with Dravet syndrome who took fenfluramine as add-on therapy for a median 1.9 years.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Zogenix, which funded editorial and writing support for the poster presentation.

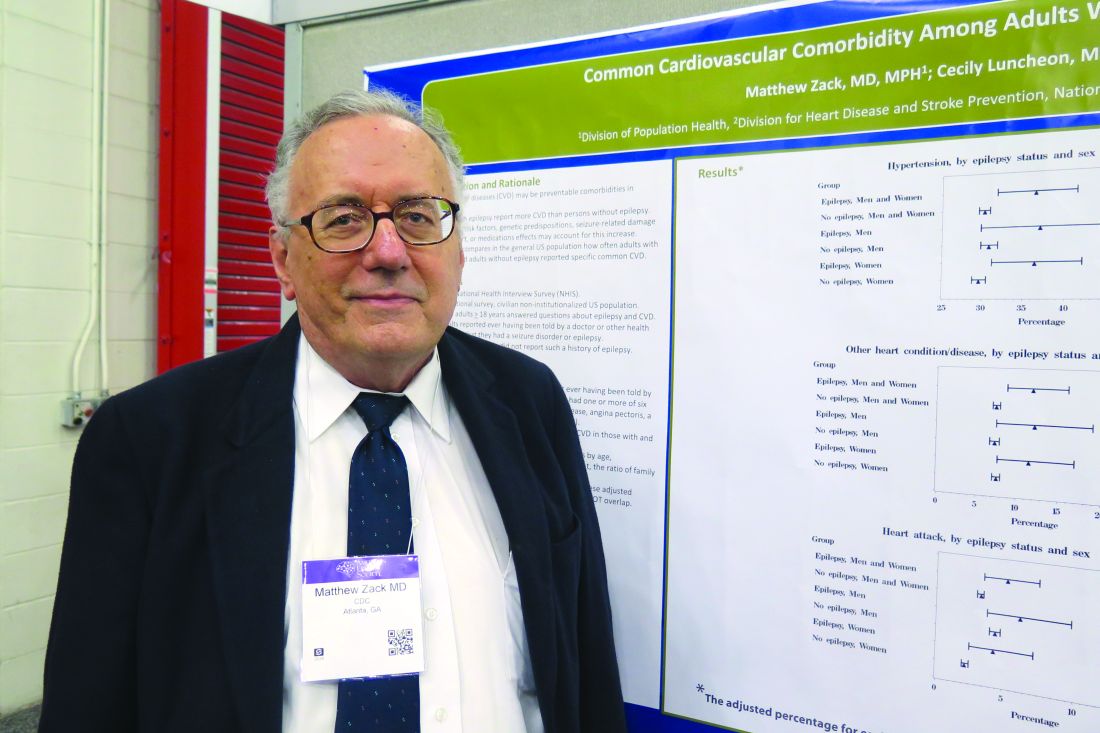

Cardiovascular comorbidities common in patients with epilepsy

HOUSTON – Adults with epilepsy reported five of the six most common cardiovascular diseases more often than did adults without epilepsy, according to results from the 2013 National Health Interview Survey.

“Often, neurologists are busy treating the seizure, making sure the patient has proper treatment, but they often don’t have the time to look at these conditions that can cause deaths a lot more commonly than things like sudden unexpected death from epilepsy,” lead study author Matthew Zack, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “We’re not talking about mortality here, but it’s important for doctors to be aware of the fact that patients with epilepsy have increased risk for conditions like heart attacks, high blood pressure, and stroke.”

Compared to NHIS respondents without epilepsy, those with any epilepsy reported significantly more hypertension (36.4% vs. 30.2%), angina pectoris (3.9% vs. 2.0%), heart attack (5.2% vs. 3.3%), other heart condition/diseases (11.8% vs. 7.4%), and stroke (12.2% vs. 2.6%; P less than .01 for all associations). “We knew that persons with epilepsy often have a preexisting stroke, but we didn’t expect this for hypertension,” Dr. Zack said. “Hypertension is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, but we also know that persons with epilepsy tend to smoke cigarettes a little bit more often than the general population. They also tend not to exercise or have physical activity. It had been a recommendation that they not participate in physical activity because it was thought to evoke seizures. But in fact, other follow-up studies have shown that’s not true, and that persons who engage in physical activity can often lessen the effects of epilepsy.”

Women with epilepsy reported significantly higher rates of three CVD conditions, compared with women who did not have epilepsy: hypertension (36.4% vs. 29.6%), angina pectoris (3.9% vs. 1.7%), and stroke (14.1% vs. 2.6%; P less than .01 for all associations). However, men with epilepsy reported only significantly more stroke, compared with men who did not have epilepsy (10.1% vs. 2.7%; P less than .01). Reasons for the differences observed between genders remain unclear and will require further analysis, Dr. Zack said. He acknowledged the self-reported nature of the NHIS as a chief limitation of the analysis. “We don’t have measurements of high blood pressure, we just have the person’s report that the doctor told them they had high blood pressure,” he said.

Dr. Zack reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – Adults with epilepsy reported five of the six most common cardiovascular diseases more often than did adults without epilepsy, according to results from the 2013 National Health Interview Survey.

“Often, neurologists are busy treating the seizure, making sure the patient has proper treatment, but they often don’t have the time to look at these conditions that can cause deaths a lot more commonly than things like sudden unexpected death from epilepsy,” lead study author Matthew Zack, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “We’re not talking about mortality here, but it’s important for doctors to be aware of the fact that patients with epilepsy have increased risk for conditions like heart attacks, high blood pressure, and stroke.”

Compared to NHIS respondents without epilepsy, those with any epilepsy reported significantly more hypertension (36.4% vs. 30.2%), angina pectoris (3.9% vs. 2.0%), heart attack (5.2% vs. 3.3%), other heart condition/diseases (11.8% vs. 7.4%), and stroke (12.2% vs. 2.6%; P less than .01 for all associations). “We knew that persons with epilepsy often have a preexisting stroke, but we didn’t expect this for hypertension,” Dr. Zack said. “Hypertension is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, but we also know that persons with epilepsy tend to smoke cigarettes a little bit more often than the general population. They also tend not to exercise or have physical activity. It had been a recommendation that they not participate in physical activity because it was thought to evoke seizures. But in fact, other follow-up studies have shown that’s not true, and that persons who engage in physical activity can often lessen the effects of epilepsy.”

Women with epilepsy reported significantly higher rates of three CVD conditions, compared with women who did not have epilepsy: hypertension (36.4% vs. 29.6%), angina pectoris (3.9% vs. 1.7%), and stroke (14.1% vs. 2.6%; P less than .01 for all associations). However, men with epilepsy reported only significantly more stroke, compared with men who did not have epilepsy (10.1% vs. 2.7%; P less than .01). Reasons for the differences observed between genders remain unclear and will require further analysis, Dr. Zack said. He acknowledged the self-reported nature of the NHIS as a chief limitation of the analysis. “We don’t have measurements of high blood pressure, we just have the person’s report that the doctor told them they had high blood pressure,” he said.

Dr. Zack reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – Adults with epilepsy reported five of the six most common cardiovascular diseases more often than did adults without epilepsy, according to results from the 2013 National Health Interview Survey.

“Often, neurologists are busy treating the seizure, making sure the patient has proper treatment, but they often don’t have the time to look at these conditions that can cause deaths a lot more commonly than things like sudden unexpected death from epilepsy,” lead study author Matthew Zack, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “We’re not talking about mortality here, but it’s important for doctors to be aware of the fact that patients with epilepsy have increased risk for conditions like heart attacks, high blood pressure, and stroke.”