User login

American Surgical Association (ASA): Annual Meeting

Surgical fellowship directors: General surgery trainees arrive ill prepared

INDIANAPOLIS – The nation’s elite surgical educators are up in arms over reported widespread deficiencies in the skill set and judgment of recent graduates of 5-year general surgery residencies.

Many trainees arrive at surgical subspecialty fellowships unprepared in their basic skills, according to a detailed new survey of the nation’s subspecialty fellowship program directors. The underlying theme of the responses is that many fellows are pursuing fellowship positions to make up for inadequacies in their general surgery residency rather than to push their skills to the next level, according to Dr. Samer Mattar.

About 80% of graduating general surgery residents now seek fellowships to obtain advanced training in bariatric, colorectal, thoracic, hepatobiliary, or other surgical specialty areas.

"Many new fellows must gain basic and fundamental skills at the beginning of their fellowship before they can commence to benefit from the advanced skills that they originally came to obtain. The current high demand for fellowship training and the lack of readiness upon completion of general surgery residencies should be a call to action for all stakeholders in surgical training," Dr. Mattar said in presenting the survey results at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

Constructive changes are afoot, according to Dr. Mattar of Indiana University, Indianapolis. Plans are well underway to change the fourth year of medical school so that students interested in a career in surgery can begin preparing for it. And there are also efforts to custom tailor the final year of general surgery residency so residents can focus on their planned fellowship year. Toward that end, the Fellowship Council has moved the fellowship match date up to June so residents who know they are fellowship-bound can put their fifth year to the best use.

The survey was conducted by the Fellowship Council, an umbrella organization in charge of standardizing curricula, accrediting programs, and matching residents to fellowships. The group distributed the surveys to all 145 subspecialty fellowship program directors and drew a 63% response rate. That’s considered high for such a lengthy survey, said Dr. Mattar, and is an indication of the importance educators place on the subject.

The survey assessed five key educational domains: professionalism, independent practice, psychomotor skills, expertise in their chosen disease state, and scholarly focus.

"Incoming fellows exhibited high levels of professionalism, but there were deficiencies in autonomy and independence, psychomotor abilities, and – most profoundly – in academics and scholarship," Dr. Mattar said.

Among the key survey findings:

• Incoming fellows were unable to independently perform half an hour of a major procedure, according to 43% of program directors.

• Of incoming fellows, 30% couldn’t independently perform basic operations such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

• Of incoming fellows, 56% were able to laparoscopically suture and tie knots properly; 26% couldn’t recognize anatomic planes through the laparoscope.

• One-quarter was deemed unable to recognize early signs of complications.

In other findings, nearly 40% of program directors said new fellows display a lack of "patient ownership." "We promote patient ownership in our programs. We are somewhat disappointed and dismayed that the fellows feel that the patient is part of a service and not their own," Dr. Mattar commented. Half of the program directors indicated their incoming fellows demonstrated independence in the operating room and on call, although they reported the fellows showed marked improvement in these areas as the year went on.

A large majority of program directors felt their fellows were disinterested in research and in advancing the field, even though, as Dr. Mattar noted, "This is a mandate in our curriculum."

He reported having no financial conflicts.

No one should be surprised by the Fellowship Council survey results. During the past decade, the failure rate on the American Board of Surgery’s oral exam has climbed steadily from 16% to 28%. At present, the percentage of examinees who fail either the oral or written American Board of Surgery exam the first time around is in the mid-30s. That’s arguably an absurd failure rate for a 5-year training program in a group of people who should have mastered the subject.

The 80-hour work limit has effectively subtracted 6-12 months from the general surgery residency, yet I do not believe this emotional and contentious issue is the explanation.

At present, the average number of operations done by a first-year resident is less than two per week, while second-year residents average two to three per week. Our residents are spending 80 hours a week while doing two or three operations per week, which arguably could be done in half a day. It would be hard to imagine a less efficient educational process.

Dr. Frank R. Lewis is executive director of the American Board of Surgery. He was an invited discussant of the presentation.

No one should be surprised by the Fellowship Council survey results. During the past decade, the failure rate on the American Board of Surgery’s oral exam has climbed steadily from 16% to 28%. At present, the percentage of examinees who fail either the oral or written American Board of Surgery exam the first time around is in the mid-30s. That’s arguably an absurd failure rate for a 5-year training program in a group of people who should have mastered the subject.

The 80-hour work limit has effectively subtracted 6-12 months from the general surgery residency, yet I do not believe this emotional and contentious issue is the explanation.

At present, the average number of operations done by a first-year resident is less than two per week, while second-year residents average two to three per week. Our residents are spending 80 hours a week while doing two or three operations per week, which arguably could be done in half a day. It would be hard to imagine a less efficient educational process.

Dr. Frank R. Lewis is executive director of the American Board of Surgery. He was an invited discussant of the presentation.

No one should be surprised by the Fellowship Council survey results. During the past decade, the failure rate on the American Board of Surgery’s oral exam has climbed steadily from 16% to 28%. At present, the percentage of examinees who fail either the oral or written American Board of Surgery exam the first time around is in the mid-30s. That’s arguably an absurd failure rate for a 5-year training program in a group of people who should have mastered the subject.

The 80-hour work limit has effectively subtracted 6-12 months from the general surgery residency, yet I do not believe this emotional and contentious issue is the explanation.

At present, the average number of operations done by a first-year resident is less than two per week, while second-year residents average two to three per week. Our residents are spending 80 hours a week while doing two or three operations per week, which arguably could be done in half a day. It would be hard to imagine a less efficient educational process.

Dr. Frank R. Lewis is executive director of the American Board of Surgery. He was an invited discussant of the presentation.

INDIANAPOLIS – The nation’s elite surgical educators are up in arms over reported widespread deficiencies in the skill set and judgment of recent graduates of 5-year general surgery residencies.

Many trainees arrive at surgical subspecialty fellowships unprepared in their basic skills, according to a detailed new survey of the nation’s subspecialty fellowship program directors. The underlying theme of the responses is that many fellows are pursuing fellowship positions to make up for inadequacies in their general surgery residency rather than to push their skills to the next level, according to Dr. Samer Mattar.

About 80% of graduating general surgery residents now seek fellowships to obtain advanced training in bariatric, colorectal, thoracic, hepatobiliary, or other surgical specialty areas.

"Many new fellows must gain basic and fundamental skills at the beginning of their fellowship before they can commence to benefit from the advanced skills that they originally came to obtain. The current high demand for fellowship training and the lack of readiness upon completion of general surgery residencies should be a call to action for all stakeholders in surgical training," Dr. Mattar said in presenting the survey results at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

Constructive changes are afoot, according to Dr. Mattar of Indiana University, Indianapolis. Plans are well underway to change the fourth year of medical school so that students interested in a career in surgery can begin preparing for it. And there are also efforts to custom tailor the final year of general surgery residency so residents can focus on their planned fellowship year. Toward that end, the Fellowship Council has moved the fellowship match date up to June so residents who know they are fellowship-bound can put their fifth year to the best use.

The survey was conducted by the Fellowship Council, an umbrella organization in charge of standardizing curricula, accrediting programs, and matching residents to fellowships. The group distributed the surveys to all 145 subspecialty fellowship program directors and drew a 63% response rate. That’s considered high for such a lengthy survey, said Dr. Mattar, and is an indication of the importance educators place on the subject.

The survey assessed five key educational domains: professionalism, independent practice, psychomotor skills, expertise in their chosen disease state, and scholarly focus.

"Incoming fellows exhibited high levels of professionalism, but there were deficiencies in autonomy and independence, psychomotor abilities, and – most profoundly – in academics and scholarship," Dr. Mattar said.

Among the key survey findings:

• Incoming fellows were unable to independently perform half an hour of a major procedure, according to 43% of program directors.

• Of incoming fellows, 30% couldn’t independently perform basic operations such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

• Of incoming fellows, 56% were able to laparoscopically suture and tie knots properly; 26% couldn’t recognize anatomic planes through the laparoscope.

• One-quarter was deemed unable to recognize early signs of complications.

In other findings, nearly 40% of program directors said new fellows display a lack of "patient ownership." "We promote patient ownership in our programs. We are somewhat disappointed and dismayed that the fellows feel that the patient is part of a service and not their own," Dr. Mattar commented. Half of the program directors indicated their incoming fellows demonstrated independence in the operating room and on call, although they reported the fellows showed marked improvement in these areas as the year went on.

A large majority of program directors felt their fellows were disinterested in research and in advancing the field, even though, as Dr. Mattar noted, "This is a mandate in our curriculum."

He reported having no financial conflicts.

INDIANAPOLIS – The nation’s elite surgical educators are up in arms over reported widespread deficiencies in the skill set and judgment of recent graduates of 5-year general surgery residencies.

Many trainees arrive at surgical subspecialty fellowships unprepared in their basic skills, according to a detailed new survey of the nation’s subspecialty fellowship program directors. The underlying theme of the responses is that many fellows are pursuing fellowship positions to make up for inadequacies in their general surgery residency rather than to push their skills to the next level, according to Dr. Samer Mattar.

About 80% of graduating general surgery residents now seek fellowships to obtain advanced training in bariatric, colorectal, thoracic, hepatobiliary, or other surgical specialty areas.

"Many new fellows must gain basic and fundamental skills at the beginning of their fellowship before they can commence to benefit from the advanced skills that they originally came to obtain. The current high demand for fellowship training and the lack of readiness upon completion of general surgery residencies should be a call to action for all stakeholders in surgical training," Dr. Mattar said in presenting the survey results at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

Constructive changes are afoot, according to Dr. Mattar of Indiana University, Indianapolis. Plans are well underway to change the fourth year of medical school so that students interested in a career in surgery can begin preparing for it. And there are also efforts to custom tailor the final year of general surgery residency so residents can focus on their planned fellowship year. Toward that end, the Fellowship Council has moved the fellowship match date up to June so residents who know they are fellowship-bound can put their fifth year to the best use.

The survey was conducted by the Fellowship Council, an umbrella organization in charge of standardizing curricula, accrediting programs, and matching residents to fellowships. The group distributed the surveys to all 145 subspecialty fellowship program directors and drew a 63% response rate. That’s considered high for such a lengthy survey, said Dr. Mattar, and is an indication of the importance educators place on the subject.

The survey assessed five key educational domains: professionalism, independent practice, psychomotor skills, expertise in their chosen disease state, and scholarly focus.

"Incoming fellows exhibited high levels of professionalism, but there were deficiencies in autonomy and independence, psychomotor abilities, and – most profoundly – in academics and scholarship," Dr. Mattar said.

Among the key survey findings:

• Incoming fellows were unable to independently perform half an hour of a major procedure, according to 43% of program directors.

• Of incoming fellows, 30% couldn’t independently perform basic operations such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

• Of incoming fellows, 56% were able to laparoscopically suture and tie knots properly; 26% couldn’t recognize anatomic planes through the laparoscope.

• One-quarter was deemed unable to recognize early signs of complications.

In other findings, nearly 40% of program directors said new fellows display a lack of "patient ownership." "We promote patient ownership in our programs. We are somewhat disappointed and dismayed that the fellows feel that the patient is part of a service and not their own," Dr. Mattar commented. Half of the program directors indicated their incoming fellows demonstrated independence in the operating room and on call, although they reported the fellows showed marked improvement in these areas as the year went on.

A large majority of program directors felt their fellows were disinterested in research and in advancing the field, even though, as Dr. Mattar noted, "This is a mandate in our curriculum."

He reported having no financial conflicts.

AT THE ASA ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: Surgical subspecialty program directors said that 43% of incoming fellows were unable to independently perform half an hour of a major procedure.

Data source: Survey responses from 91 of the nation’s 145 surgical subspecialty program directors.

Disclosures: The survey was conducted by the Fellowship Council, an umbrella organization with oversight over surgical subspecialty fellowships. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Elevated glucose after colorectal surgery spells trouble

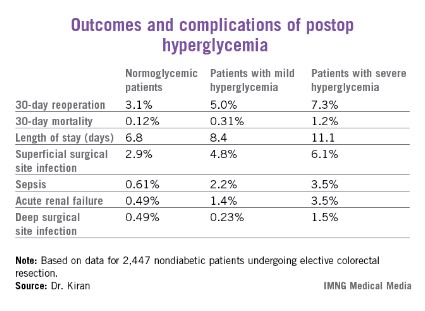

INDIANAPOLIS – Even a single brief episode of postoperative hyperglycemia after colorectal resection in nondiabetic patients was independently associated with increased morbidity and mortality in a large consecutive patient series.

The risks of a variety of complications, both infectious and noninfectious, in nondiabetic patients with postoperative hyperglycemia were similar in magnitude to those seen in diabetic patients experiencing postoperative hyperglycemia.

"A take-home point from our study would be that since it’s known that in diabetic patients it’s absolutely paramount to control hyperglycemia, perhaps nondiabetic patients undergoing major operations – especially colorectal surgery – need to be carefully monitored and have their glucose managed," Dr. P. Ravi Kiran said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

He and his coinvestigators evaluated the significance of hyperglycemia occurring within 48 hours postoperatively in 2,628 consecutive patients undergoing elective colorectal resection at the Cleveland Clinic in a recent 2-year period.

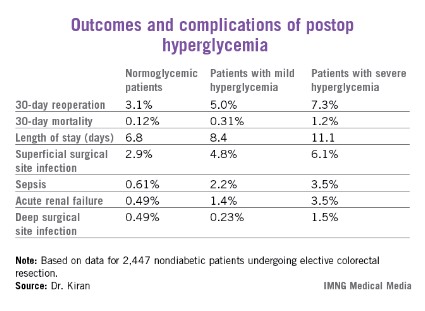

A total of 2,447 of these patients were nondiabetic. They collectively had 16,404 randomly obtained postoperative blood glucose measurements. One-third of them remained normoglycemic, with all their blood glucose values remaining at 125 mg/dL or less. Another 52.7% had one or more episodes of mild hyperglycemia as defined by a blood glucose value of 126-200 mg/dL. And 14% of nondiabetic subjects experienced postoperative severe hyperglycemia, with a level in excess of 200 mg/dL.

Those rates were similar to those of the known-diabetic patients, 35% of whom remained normoglycemic postoperatively, while 54% became mildly hyperglycemic and 11% severely hyperglycemic.

Postoperative hyperglycemia in nondiabetic patients was associated with greater intraoperative estimated blood loss. The transfusion rate was 4.8% in normoglycemic patients, 10.3% in mildly hyperglycemic ones, and 18.1% in those with severe hyperglycemia. The length of surgery averaged 137 minutes in normoglycemic patients, 166 minutes in patients with postoperative mild hyperglycemia, and 181 minutes in patients with severe hyperglycemia.

Any episode of postoperative severe hyperglycemia in the nondiabetic patients was associated with significantly higher rates of both superficial and deep surgical site infections, greater length of stay, and higher 30-day mortality, compared with normoglycemic patients (see chart). Mild hyperglycemia wasn’t associated with as many complications; however, it was linked to a significantly increased rate of sepsis and a greater length of stay.

Moreover, in a multivariate analysis mild hyperglycemia was independently associated with a 2.1-fold increased risk of reoperation within 30 days, while severe hyperglycemia carried a 3.8-fold increased risk, compared with normoglycemia, continued Dr. Kiran of the Cleveland Clinic.

The investigators identified two major independent risk factors for sepsis in nondiabetic patients: an American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status class of 3 or more (odds ratio, 4.2), and postoperative hyperglycemia, which was associated with roughly an 8-fold risk regardless of whether the hyperglycemia was mild or severe.

Studies from the cardiovascular and trauma surgery literature suggest postoperative uncontrolled blood glucose may lead to adverse outcomes. Dr. Kiran and his coworkers performed this study because the impact of elevated blood glucose after elective major abdominal surgery had not been well defined, although colorectal surgery entails bacterial contamination, so background rates of surgical site and other infectious complications already tend to run relatively high.

Dr. Kiran said he believes postoperative hyperglycemia is probably a surrogate marker, perhaps for a distressed physiologic state or for looming complications. The next major question he and his coinvestigators want to tackle is this: Do prompt recognition and management of postoperative hyperglycemia in nondiabetic colorectal resection patients improve outcomes?

A cautionary note was sounded by discussant Dr. Hiram C. Polk Jr.,who emphasized that management strategies involving tight glucose control entail the risk of potentially disastrous postsurgical hypoglycemia.

"As many of you know, there are more than half a dozen patients in the midwestern U.S. who’ve been rendered badly hurt with hypoglycemia and cerebral damage. They’re working their way through the legal system at this point. It’s a fine balance: Sometimes perfection is the enemy of good in this situation," warned Dr. Polk, professor and chairman of the surgery department at the University of Louisville (Ky.).

He noted as an aside that just as Dr. Kiran found that even a single episode of postoperative hyperglycemia has adverse consequences, he and his Louisville coworkers have found the same is true for hypothermia.

"A single brief episode of hypothermia seems to throw the wheels off the track. It disrupts something in host defenses and makes everything very difficult," Dr. Polk observed.

The study was sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. Dr. Kiran reported no financial conflicts.

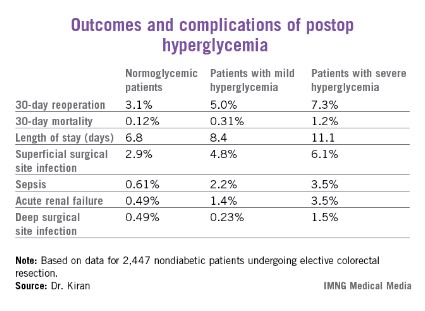

INDIANAPOLIS – Even a single brief episode of postoperative hyperglycemia after colorectal resection in nondiabetic patients was independently associated with increased morbidity and mortality in a large consecutive patient series.

The risks of a variety of complications, both infectious and noninfectious, in nondiabetic patients with postoperative hyperglycemia were similar in magnitude to those seen in diabetic patients experiencing postoperative hyperglycemia.

"A take-home point from our study would be that since it’s known that in diabetic patients it’s absolutely paramount to control hyperglycemia, perhaps nondiabetic patients undergoing major operations – especially colorectal surgery – need to be carefully monitored and have their glucose managed," Dr. P. Ravi Kiran said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

He and his coinvestigators evaluated the significance of hyperglycemia occurring within 48 hours postoperatively in 2,628 consecutive patients undergoing elective colorectal resection at the Cleveland Clinic in a recent 2-year period.

A total of 2,447 of these patients were nondiabetic. They collectively had 16,404 randomly obtained postoperative blood glucose measurements. One-third of them remained normoglycemic, with all their blood glucose values remaining at 125 mg/dL or less. Another 52.7% had one or more episodes of mild hyperglycemia as defined by a blood glucose value of 126-200 mg/dL. And 14% of nondiabetic subjects experienced postoperative severe hyperglycemia, with a level in excess of 200 mg/dL.

Those rates were similar to those of the known-diabetic patients, 35% of whom remained normoglycemic postoperatively, while 54% became mildly hyperglycemic and 11% severely hyperglycemic.

Postoperative hyperglycemia in nondiabetic patients was associated with greater intraoperative estimated blood loss. The transfusion rate was 4.8% in normoglycemic patients, 10.3% in mildly hyperglycemic ones, and 18.1% in those with severe hyperglycemia. The length of surgery averaged 137 minutes in normoglycemic patients, 166 minutes in patients with postoperative mild hyperglycemia, and 181 minutes in patients with severe hyperglycemia.

Any episode of postoperative severe hyperglycemia in the nondiabetic patients was associated with significantly higher rates of both superficial and deep surgical site infections, greater length of stay, and higher 30-day mortality, compared with normoglycemic patients (see chart). Mild hyperglycemia wasn’t associated with as many complications; however, it was linked to a significantly increased rate of sepsis and a greater length of stay.

Moreover, in a multivariate analysis mild hyperglycemia was independently associated with a 2.1-fold increased risk of reoperation within 30 days, while severe hyperglycemia carried a 3.8-fold increased risk, compared with normoglycemia, continued Dr. Kiran of the Cleveland Clinic.

The investigators identified two major independent risk factors for sepsis in nondiabetic patients: an American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status class of 3 or more (odds ratio, 4.2), and postoperative hyperglycemia, which was associated with roughly an 8-fold risk regardless of whether the hyperglycemia was mild or severe.

Studies from the cardiovascular and trauma surgery literature suggest postoperative uncontrolled blood glucose may lead to adverse outcomes. Dr. Kiran and his coworkers performed this study because the impact of elevated blood glucose after elective major abdominal surgery had not been well defined, although colorectal surgery entails bacterial contamination, so background rates of surgical site and other infectious complications already tend to run relatively high.

Dr. Kiran said he believes postoperative hyperglycemia is probably a surrogate marker, perhaps for a distressed physiologic state or for looming complications. The next major question he and his coinvestigators want to tackle is this: Do prompt recognition and management of postoperative hyperglycemia in nondiabetic colorectal resection patients improve outcomes?

A cautionary note was sounded by discussant Dr. Hiram C. Polk Jr.,who emphasized that management strategies involving tight glucose control entail the risk of potentially disastrous postsurgical hypoglycemia.

"As many of you know, there are more than half a dozen patients in the midwestern U.S. who’ve been rendered badly hurt with hypoglycemia and cerebral damage. They’re working their way through the legal system at this point. It’s a fine balance: Sometimes perfection is the enemy of good in this situation," warned Dr. Polk, professor and chairman of the surgery department at the University of Louisville (Ky.).

He noted as an aside that just as Dr. Kiran found that even a single episode of postoperative hyperglycemia has adverse consequences, he and his Louisville coworkers have found the same is true for hypothermia.

"A single brief episode of hypothermia seems to throw the wheels off the track. It disrupts something in host defenses and makes everything very difficult," Dr. Polk observed.

The study was sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. Dr. Kiran reported no financial conflicts.

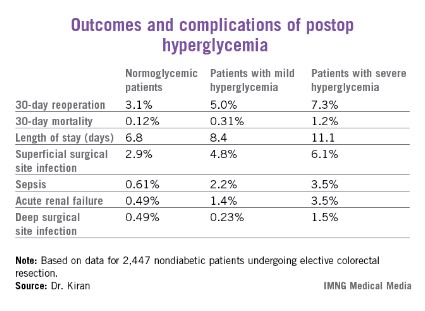

INDIANAPOLIS – Even a single brief episode of postoperative hyperglycemia after colorectal resection in nondiabetic patients was independently associated with increased morbidity and mortality in a large consecutive patient series.

The risks of a variety of complications, both infectious and noninfectious, in nondiabetic patients with postoperative hyperglycemia were similar in magnitude to those seen in diabetic patients experiencing postoperative hyperglycemia.

"A take-home point from our study would be that since it’s known that in diabetic patients it’s absolutely paramount to control hyperglycemia, perhaps nondiabetic patients undergoing major operations – especially colorectal surgery – need to be carefully monitored and have their glucose managed," Dr. P. Ravi Kiran said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

He and his coinvestigators evaluated the significance of hyperglycemia occurring within 48 hours postoperatively in 2,628 consecutive patients undergoing elective colorectal resection at the Cleveland Clinic in a recent 2-year period.

A total of 2,447 of these patients were nondiabetic. They collectively had 16,404 randomly obtained postoperative blood glucose measurements. One-third of them remained normoglycemic, with all their blood glucose values remaining at 125 mg/dL or less. Another 52.7% had one or more episodes of mild hyperglycemia as defined by a blood glucose value of 126-200 mg/dL. And 14% of nondiabetic subjects experienced postoperative severe hyperglycemia, with a level in excess of 200 mg/dL.

Those rates were similar to those of the known-diabetic patients, 35% of whom remained normoglycemic postoperatively, while 54% became mildly hyperglycemic and 11% severely hyperglycemic.

Postoperative hyperglycemia in nondiabetic patients was associated with greater intraoperative estimated blood loss. The transfusion rate was 4.8% in normoglycemic patients, 10.3% in mildly hyperglycemic ones, and 18.1% in those with severe hyperglycemia. The length of surgery averaged 137 minutes in normoglycemic patients, 166 minutes in patients with postoperative mild hyperglycemia, and 181 minutes in patients with severe hyperglycemia.

Any episode of postoperative severe hyperglycemia in the nondiabetic patients was associated with significantly higher rates of both superficial and deep surgical site infections, greater length of stay, and higher 30-day mortality, compared with normoglycemic patients (see chart). Mild hyperglycemia wasn’t associated with as many complications; however, it was linked to a significantly increased rate of sepsis and a greater length of stay.

Moreover, in a multivariate analysis mild hyperglycemia was independently associated with a 2.1-fold increased risk of reoperation within 30 days, while severe hyperglycemia carried a 3.8-fold increased risk, compared with normoglycemia, continued Dr. Kiran of the Cleveland Clinic.

The investigators identified two major independent risk factors for sepsis in nondiabetic patients: an American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status class of 3 or more (odds ratio, 4.2), and postoperative hyperglycemia, which was associated with roughly an 8-fold risk regardless of whether the hyperglycemia was mild or severe.

Studies from the cardiovascular and trauma surgery literature suggest postoperative uncontrolled blood glucose may lead to adverse outcomes. Dr. Kiran and his coworkers performed this study because the impact of elevated blood glucose after elective major abdominal surgery had not been well defined, although colorectal surgery entails bacterial contamination, so background rates of surgical site and other infectious complications already tend to run relatively high.

Dr. Kiran said he believes postoperative hyperglycemia is probably a surrogate marker, perhaps for a distressed physiologic state or for looming complications. The next major question he and his coinvestigators want to tackle is this: Do prompt recognition and management of postoperative hyperglycemia in nondiabetic colorectal resection patients improve outcomes?

A cautionary note was sounded by discussant Dr. Hiram C. Polk Jr.,who emphasized that management strategies involving tight glucose control entail the risk of potentially disastrous postsurgical hypoglycemia.

"As many of you know, there are more than half a dozen patients in the midwestern U.S. who’ve been rendered badly hurt with hypoglycemia and cerebral damage. They’re working their way through the legal system at this point. It’s a fine balance: Sometimes perfection is the enemy of good in this situation," warned Dr. Polk, professor and chairman of the surgery department at the University of Louisville (Ky.).

He noted as an aside that just as Dr. Kiran found that even a single episode of postoperative hyperglycemia has adverse consequences, he and his Louisville coworkers have found the same is true for hypothermia.

"A single brief episode of hypothermia seems to throw the wheels off the track. It disrupts something in host defenses and makes everything very difficult," Dr. Polk observed.

The study was sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. Dr. Kiran reported no financial conflicts.

AT THE ASA ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: Mild hyperglycemia occurring within 48 hours after major colorectal surgery in nondiabetic patients was independently associated with a doubled risk of reoperation within 30 days and a 7.9-fold increase in sepsis, compared with patients who remained normoglycemic. Severe hyperglycemia – a blood glucose measurement in excess of 200 mg/dL – was associated with even worse outcomes.

Data source: A single-center study of more than 16,000 postoperative blood glucose measurements in 2,628 consecutive patients who underwent colorectal resection.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. Dr. Kiran reported no financial conflicts.

Study questions value of Surgical Care Improvement Project quality measure

INDIANAPOLIS – Intraoperative temperature proved unrelated to the risk of surgical site infection following major colorectal surgery in a large patient series.

This finding undercuts the rationale for normothermia as a process measure that’s part of the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP) sponsored by CMS in partnership with the American College of Surgeons and other organizations.

"Our study suggests that perioperative normothermia is not independently associated in and of itself with reduced surgical site infections after colorectal surgery, and this as a process measure may have limited utility in actually decreasing SSIs. We believe that efforts in other areas may be more efficacious," Dr. Genevieve B. Melton-Meaux said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

She hastened to add that she and her coinvestigators are by no means saying intraoperative warming is unimportant. Indeed, there is compelling evidence that warming has physiologic benefit. Also, it has been shown that intraoperative hypothermia boosts SSI risk by about three-fold (N. Engl. J. Med. 1996; 334:1209-15). But the investigators take issue with the SCIP quality measure mandating documentation of a temperature of exactly 36° C at the end of a surgical case, given that their study demonstrated that this metric had no correlation with SSI rate.

"Our message and belief is that warming is a good thing and hypothermia is not a good thing. Warming is indeed something that should be done," emphasized Dr. Melton-Meaux, a colorectal surgeon at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

She presented an analysis of continuously measured intraoperative temperature data recorded via anesthesia information system in 1,008 adults who underwent major colorectal procedures at the Cleveland Clinic during a recent 1-year period. Roughly two-thirds of the patients had either a partial colectomy, a proctectomy, or total abdominal colectomy. The mean operating time was 173 minutes, and 22% of patients had a laparoscopic approach. The anesthesia information system, Dr. Melton-Meaux observed, is a hitherto largely untapped rich data source for research, since it records temperature and other physiologic data throughout the operation.

Active rewarming was performed in 92% of cases. A total of 91% of patients received an antibiotic within 1 hour prior to incision, in accord with another SCIP performance measure. The mean and median intraoperative temperature was 36.0° C, with an ending temperature of 36.3° C.

The 30-day SSI rate was 17.4%, including an organ/space infection rate of 8.5%. Neither maximum, minimum, median, nor ending temperature differed significantly among patients who developed an SSI and those who didn’t. In a multivariate analysis, the only factors significantly associated with SSI risk were preoperative diabetes, which carried a 1.9-fold increased risk; laparoscopic approach, which was associated with a 41% reduction in risk; and estimated blood loss.

Discussant Dr. Mary T. Hawn characterized the temperature study as an indictment of SCIP.

"Colorectal surgery, as we all know, has been a major focus of the Surgical Care Improvement Project. Yet despite rapid adoption and standardization of some aspects of perioperative care, there is little if any evidence that any meaningful improvements in outcomes have been realized. And the evidence to support many of the SCIP metrics is limited. For instance, the evidence to support the use of prophylactic antibiotics is based upon extensive Level 1 data, but that data is on whether or not the patient received the antibiotic, not whether it was given within 60 minutes prior to incision," said Dr. Hawn of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

She added that it’s incumbent upon surgeons themselves to develop the evidence for alternative metrics that more meaningfully measure true surgical quality.

"If you Google ‘SCIP normothermia measure,’ the first three sites that come up are companies selling these devices, so I think we need to study them," the surgeon said.

Other audience members decried the fact that hospitals are spending millions of dollars to be compliant with quality scorecards based in large part upon SCIP process measures of unproven value.

"Are we ready to recommend to CMS that they modify their indirect attempts to alter the practice of medicine by telling us exactly what we ought to do with temperature?" commented Dr. Kenneth L. Mattox, professor and vice chairman of the department of surgery at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

Dr. Melton-Meaux commented, "I think the intention behind the process measures is the right one: that we should be implementing system-wide best practices. But I think what has happened inadvertently, especially because SCIP has become part of value-based purchasing, is we are all playing a game. We are playing to the measure rather than really focusing on delivering better care and better outcomes."

Reducing surgical site infections has been a major focus of SCIP because they constitute the most common and costly complication of colorectal surgery. Moreover, SSI is the most powerful risk factor for readmission within 30 days.

Dr. Melton-Meaux reported having no financial conflicts.

INDIANAPOLIS – Intraoperative temperature proved unrelated to the risk of surgical site infection following major colorectal surgery in a large patient series.

This finding undercuts the rationale for normothermia as a process measure that’s part of the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP) sponsored by CMS in partnership with the American College of Surgeons and other organizations.

"Our study suggests that perioperative normothermia is not independently associated in and of itself with reduced surgical site infections after colorectal surgery, and this as a process measure may have limited utility in actually decreasing SSIs. We believe that efforts in other areas may be more efficacious," Dr. Genevieve B. Melton-Meaux said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

She hastened to add that she and her coinvestigators are by no means saying intraoperative warming is unimportant. Indeed, there is compelling evidence that warming has physiologic benefit. Also, it has been shown that intraoperative hypothermia boosts SSI risk by about three-fold (N. Engl. J. Med. 1996; 334:1209-15). But the investigators take issue with the SCIP quality measure mandating documentation of a temperature of exactly 36° C at the end of a surgical case, given that their study demonstrated that this metric had no correlation with SSI rate.

"Our message and belief is that warming is a good thing and hypothermia is not a good thing. Warming is indeed something that should be done," emphasized Dr. Melton-Meaux, a colorectal surgeon at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

She presented an analysis of continuously measured intraoperative temperature data recorded via anesthesia information system in 1,008 adults who underwent major colorectal procedures at the Cleveland Clinic during a recent 1-year period. Roughly two-thirds of the patients had either a partial colectomy, a proctectomy, or total abdominal colectomy. The mean operating time was 173 minutes, and 22% of patients had a laparoscopic approach. The anesthesia information system, Dr. Melton-Meaux observed, is a hitherto largely untapped rich data source for research, since it records temperature and other physiologic data throughout the operation.

Active rewarming was performed in 92% of cases. A total of 91% of patients received an antibiotic within 1 hour prior to incision, in accord with another SCIP performance measure. The mean and median intraoperative temperature was 36.0° C, with an ending temperature of 36.3° C.

The 30-day SSI rate was 17.4%, including an organ/space infection rate of 8.5%. Neither maximum, minimum, median, nor ending temperature differed significantly among patients who developed an SSI and those who didn’t. In a multivariate analysis, the only factors significantly associated with SSI risk were preoperative diabetes, which carried a 1.9-fold increased risk; laparoscopic approach, which was associated with a 41% reduction in risk; and estimated blood loss.

Discussant Dr. Mary T. Hawn characterized the temperature study as an indictment of SCIP.

"Colorectal surgery, as we all know, has been a major focus of the Surgical Care Improvement Project. Yet despite rapid adoption and standardization of some aspects of perioperative care, there is little if any evidence that any meaningful improvements in outcomes have been realized. And the evidence to support many of the SCIP metrics is limited. For instance, the evidence to support the use of prophylactic antibiotics is based upon extensive Level 1 data, but that data is on whether or not the patient received the antibiotic, not whether it was given within 60 minutes prior to incision," said Dr. Hawn of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

She added that it’s incumbent upon surgeons themselves to develop the evidence for alternative metrics that more meaningfully measure true surgical quality.

"If you Google ‘SCIP normothermia measure,’ the first three sites that come up are companies selling these devices, so I think we need to study them," the surgeon said.

Other audience members decried the fact that hospitals are spending millions of dollars to be compliant with quality scorecards based in large part upon SCIP process measures of unproven value.

"Are we ready to recommend to CMS that they modify their indirect attempts to alter the practice of medicine by telling us exactly what we ought to do with temperature?" commented Dr. Kenneth L. Mattox, professor and vice chairman of the department of surgery at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

Dr. Melton-Meaux commented, "I think the intention behind the process measures is the right one: that we should be implementing system-wide best practices. But I think what has happened inadvertently, especially because SCIP has become part of value-based purchasing, is we are all playing a game. We are playing to the measure rather than really focusing on delivering better care and better outcomes."

Reducing surgical site infections has been a major focus of SCIP because they constitute the most common and costly complication of colorectal surgery. Moreover, SSI is the most powerful risk factor for readmission within 30 days.

Dr. Melton-Meaux reported having no financial conflicts.

INDIANAPOLIS – Intraoperative temperature proved unrelated to the risk of surgical site infection following major colorectal surgery in a large patient series.

This finding undercuts the rationale for normothermia as a process measure that’s part of the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP) sponsored by CMS in partnership with the American College of Surgeons and other organizations.

"Our study suggests that perioperative normothermia is not independently associated in and of itself with reduced surgical site infections after colorectal surgery, and this as a process measure may have limited utility in actually decreasing SSIs. We believe that efforts in other areas may be more efficacious," Dr. Genevieve B. Melton-Meaux said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

She hastened to add that she and her coinvestigators are by no means saying intraoperative warming is unimportant. Indeed, there is compelling evidence that warming has physiologic benefit. Also, it has been shown that intraoperative hypothermia boosts SSI risk by about three-fold (N. Engl. J. Med. 1996; 334:1209-15). But the investigators take issue with the SCIP quality measure mandating documentation of a temperature of exactly 36° C at the end of a surgical case, given that their study demonstrated that this metric had no correlation with SSI rate.

"Our message and belief is that warming is a good thing and hypothermia is not a good thing. Warming is indeed something that should be done," emphasized Dr. Melton-Meaux, a colorectal surgeon at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

She presented an analysis of continuously measured intraoperative temperature data recorded via anesthesia information system in 1,008 adults who underwent major colorectal procedures at the Cleveland Clinic during a recent 1-year period. Roughly two-thirds of the patients had either a partial colectomy, a proctectomy, or total abdominal colectomy. The mean operating time was 173 minutes, and 22% of patients had a laparoscopic approach. The anesthesia information system, Dr. Melton-Meaux observed, is a hitherto largely untapped rich data source for research, since it records temperature and other physiologic data throughout the operation.

Active rewarming was performed in 92% of cases. A total of 91% of patients received an antibiotic within 1 hour prior to incision, in accord with another SCIP performance measure. The mean and median intraoperative temperature was 36.0° C, with an ending temperature of 36.3° C.

The 30-day SSI rate was 17.4%, including an organ/space infection rate of 8.5%. Neither maximum, minimum, median, nor ending temperature differed significantly among patients who developed an SSI and those who didn’t. In a multivariate analysis, the only factors significantly associated with SSI risk were preoperative diabetes, which carried a 1.9-fold increased risk; laparoscopic approach, which was associated with a 41% reduction in risk; and estimated blood loss.

Discussant Dr. Mary T. Hawn characterized the temperature study as an indictment of SCIP.

"Colorectal surgery, as we all know, has been a major focus of the Surgical Care Improvement Project. Yet despite rapid adoption and standardization of some aspects of perioperative care, there is little if any evidence that any meaningful improvements in outcomes have been realized. And the evidence to support many of the SCIP metrics is limited. For instance, the evidence to support the use of prophylactic antibiotics is based upon extensive Level 1 data, but that data is on whether or not the patient received the antibiotic, not whether it was given within 60 minutes prior to incision," said Dr. Hawn of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

She added that it’s incumbent upon surgeons themselves to develop the evidence for alternative metrics that more meaningfully measure true surgical quality.

"If you Google ‘SCIP normothermia measure,’ the first three sites that come up are companies selling these devices, so I think we need to study them," the surgeon said.

Other audience members decried the fact that hospitals are spending millions of dollars to be compliant with quality scorecards based in large part upon SCIP process measures of unproven value.

"Are we ready to recommend to CMS that they modify their indirect attempts to alter the practice of medicine by telling us exactly what we ought to do with temperature?" commented Dr. Kenneth L. Mattox, professor and vice chairman of the department of surgery at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

Dr. Melton-Meaux commented, "I think the intention behind the process measures is the right one: that we should be implementing system-wide best practices. But I think what has happened inadvertently, especially because SCIP has become part of value-based purchasing, is we are all playing a game. We are playing to the measure rather than really focusing on delivering better care and better outcomes."

Reducing surgical site infections has been a major focus of SCIP because they constitute the most common and costly complication of colorectal surgery. Moreover, SSI is the most powerful risk factor for readmission within 30 days.

Dr. Melton-Meaux reported having no financial conflicts.

AT THE ASA ANNUAL MEETING

Major Finding: Intraoperative temperatures in patients undergoing major colorectal surgery proved unrelated to surgical site infection risk.

Data Source: A retrospective study of continuous intraoperative temperature data measured via an anesthesia information system in 1,008 adults undergoing major colorectal procedures.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Watchful waiting doesn't pay for asymptomatic inguinal hernias

INDIANAPOLIS – The luster has suddenly worn off the time-honored strategy of nonoperative watchful waiting in men with minimally symptomatic inguinal hernias.

New evidence indicates the vast majority of men with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic inguinal hernias will eventually come to surgery. This may not occur until years down the road, when their advanced age may render surgery more arduous.

"Although watchful waiting remains a safe strategy, even on long-term follow-up, patients who present to their physician to have their hernia evaluated, especially if elderly, should be informed that almost certainly they will come to surgery eventually ... The logical assumption is that watchful waiting is not an effective strategy, as with time almost all men cross over," Dr. Robert J. Fitzgibbons Jr. explained at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

He presented an extended follow-up of patients enrolled in a landmark randomized multicenter clinical trial, one of only two randomized studies ever done comparing watchful waiting versus routine surgical repair for men with minimally symptomatic inguinal hernia. In the earlier report by Dr. Fitzgibbons and coworkers, watchful waiting was deemed "an acceptable option" because only 23% of patients crossed over to surgery due to increased pain during the first 2 years of follow-up (JAMA 2006;295:285-92).

At the ASA meeting, however, he presented updated 10-year follow-up data on 167 patients from the cohort initially assigned to watchful waiting. The rate of crossover to surgery was 68% by 10 years, with a marked age-based divergence. Patients below age 65 had a 62% crossover rate, while those above that age had a 79% crossover rate, according to Dr. Fitzgibbons, professor of surgery and chief of the division of general surgery at Creighton University, Omaha, Neb.

The good news was that hernia incarceration was a rare event, occurring at a rate of just 0.2% per year over the course of 10 years.

"We as surgeons have been taught for many years that we must repair all our hernias to prevent hernia accidents. Well, only three patients in our whole study developed incarceration, for which they underwent surgery with no mortality," Dr. Fitzgibbons noted. "The risk of a hernia accident should not be considered an indication for surgery. Older studies in the literature which would suggest otherwise can no longer be considered relevant."

He offered a caveat regarding the study findings: Participants were enrolled after they sought medical attention because of their hernias, even though they were asymptomatic or only minimally symptomatic. So the study results are most applicable to men concerned enough about their hernias that they visit a physician for that reason.

"It’s probably not valid to extrapolate the conclusions in this study to the entire population of minimally symptomatic inguinal hernia patients," the surgeon said. "Physicians have been observing elderly patients for years and would be loath to believe a crossover rate this high."

Nevertheless, the results of this study are virtually identical to those of the only other randomized trial of watchful waiting, which was conducted by surgeons at the University of Glasgow. The most recent update from that study showed an estimated crossover rate in the watchful waiting group of 16% at 1 year, 54% at 5 years, and 72% at 7.5 years. As in the American study, the rate of acute incarceration was reassuringly small. The investigators concluded that watchful waiting appears pointless, and they recommended surgical repair for medically fit patients (Br. J. Surg. 2011;98:596-9).

Discussant Dr. Michael E. Zenilman commented that his own approach is to individualize patient management based in large part upon activity level.

"When I see patients who are 80 years old in the office with an asymptomatic hernia, my conversation with them is about what their lifestyle is like. If they’re an active golfer I know that they’re going to end up getting their hernia fixed. If they’re sedentary, sitting at home in retirement, they don’t. So I think the next step in your research project should be to find out what the activity level is of these patients who are getting older and have asymptomatic hernias," said Dr. Zenilman, vice chair and regional director of surgery for the Washington, D.C., region, Johns Hopkins Medicine.

Dr. Fitzgibbons’ trial was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality with support from the American College of Surgeons. He reported having no financial conflicts.

This report is finally a victory for surgeons who plead for common sense in the pursuit of evidence-based practice. Dr. Robert J. Fitzgibbons, recognized as one of surgery's foremost experts in hernia repair, presents long-term follow-up of patients with inguinal hernia who are treated expectantly. There are three very significant results. First, complications are very rare (0.5% per year, and these patients did OK with urgent management). Second, most patients will decide to have their hernias repaired, eventually (68% at 10 years). Finally, older patients are the ones most likely to come to repair.

Dr. Savarise |

What this means for the thousands of surgeons who see these patients on a regular basis is that shared clinical decision making with our patients, based on the surgeon's judgment of operative risks and benefits, is the correct clinical pathway. Nonoperative management, when in the opinion of the surgeon and in the patient to be in the patient's best interest, is safe. Immediate operation, even in patients with asymptomatic hernias, is standard of care. And it would be perfectly reasonable for any good-risk patient to schedule an elective hernia repair at his convenience.

Dr. Mark Savarise is an ACS Fellow and clinical assistant professor of surgery, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

This report is finally a victory for surgeons who plead for common sense in the pursuit of evidence-based practice. Dr. Robert J. Fitzgibbons, recognized as one of surgery's foremost experts in hernia repair, presents long-term follow-up of patients with inguinal hernia who are treated expectantly. There are three very significant results. First, complications are very rare (0.5% per year, and these patients did OK with urgent management). Second, most patients will decide to have their hernias repaired, eventually (68% at 10 years). Finally, older patients are the ones most likely to come to repair.

Dr. Savarise |

What this means for the thousands of surgeons who see these patients on a regular basis is that shared clinical decision making with our patients, based on the surgeon's judgment of operative risks and benefits, is the correct clinical pathway. Nonoperative management, when in the opinion of the surgeon and in the patient to be in the patient's best interest, is safe. Immediate operation, even in patients with asymptomatic hernias, is standard of care. And it would be perfectly reasonable for any good-risk patient to schedule an elective hernia repair at his convenience.

Dr. Mark Savarise is an ACS Fellow and clinical assistant professor of surgery, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

This report is finally a victory for surgeons who plead for common sense in the pursuit of evidence-based practice. Dr. Robert J. Fitzgibbons, recognized as one of surgery's foremost experts in hernia repair, presents long-term follow-up of patients with inguinal hernia who are treated expectantly. There are three very significant results. First, complications are very rare (0.5% per year, and these patients did OK with urgent management). Second, most patients will decide to have their hernias repaired, eventually (68% at 10 years). Finally, older patients are the ones most likely to come to repair.

Dr. Savarise |

What this means for the thousands of surgeons who see these patients on a regular basis is that shared clinical decision making with our patients, based on the surgeon's judgment of operative risks and benefits, is the correct clinical pathway. Nonoperative management, when in the opinion of the surgeon and in the patient to be in the patient's best interest, is safe. Immediate operation, even in patients with asymptomatic hernias, is standard of care. And it would be perfectly reasonable for any good-risk patient to schedule an elective hernia repair at his convenience.

Dr. Mark Savarise is an ACS Fellow and clinical assistant professor of surgery, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

INDIANAPOLIS – The luster has suddenly worn off the time-honored strategy of nonoperative watchful waiting in men with minimally symptomatic inguinal hernias.

New evidence indicates the vast majority of men with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic inguinal hernias will eventually come to surgery. This may not occur until years down the road, when their advanced age may render surgery more arduous.

"Although watchful waiting remains a safe strategy, even on long-term follow-up, patients who present to their physician to have their hernia evaluated, especially if elderly, should be informed that almost certainly they will come to surgery eventually ... The logical assumption is that watchful waiting is not an effective strategy, as with time almost all men cross over," Dr. Robert J. Fitzgibbons Jr. explained at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

He presented an extended follow-up of patients enrolled in a landmark randomized multicenter clinical trial, one of only two randomized studies ever done comparing watchful waiting versus routine surgical repair for men with minimally symptomatic inguinal hernia. In the earlier report by Dr. Fitzgibbons and coworkers, watchful waiting was deemed "an acceptable option" because only 23% of patients crossed over to surgery due to increased pain during the first 2 years of follow-up (JAMA 2006;295:285-92).

At the ASA meeting, however, he presented updated 10-year follow-up data on 167 patients from the cohort initially assigned to watchful waiting. The rate of crossover to surgery was 68% by 10 years, with a marked age-based divergence. Patients below age 65 had a 62% crossover rate, while those above that age had a 79% crossover rate, according to Dr. Fitzgibbons, professor of surgery and chief of the division of general surgery at Creighton University, Omaha, Neb.

The good news was that hernia incarceration was a rare event, occurring at a rate of just 0.2% per year over the course of 10 years.

"We as surgeons have been taught for many years that we must repair all our hernias to prevent hernia accidents. Well, only three patients in our whole study developed incarceration, for which they underwent surgery with no mortality," Dr. Fitzgibbons noted. "The risk of a hernia accident should not be considered an indication for surgery. Older studies in the literature which would suggest otherwise can no longer be considered relevant."

He offered a caveat regarding the study findings: Participants were enrolled after they sought medical attention because of their hernias, even though they were asymptomatic or only minimally symptomatic. So the study results are most applicable to men concerned enough about their hernias that they visit a physician for that reason.

"It’s probably not valid to extrapolate the conclusions in this study to the entire population of minimally symptomatic inguinal hernia patients," the surgeon said. "Physicians have been observing elderly patients for years and would be loath to believe a crossover rate this high."

Nevertheless, the results of this study are virtually identical to those of the only other randomized trial of watchful waiting, which was conducted by surgeons at the University of Glasgow. The most recent update from that study showed an estimated crossover rate in the watchful waiting group of 16% at 1 year, 54% at 5 years, and 72% at 7.5 years. As in the American study, the rate of acute incarceration was reassuringly small. The investigators concluded that watchful waiting appears pointless, and they recommended surgical repair for medically fit patients (Br. J. Surg. 2011;98:596-9).

Discussant Dr. Michael E. Zenilman commented that his own approach is to individualize patient management based in large part upon activity level.

"When I see patients who are 80 years old in the office with an asymptomatic hernia, my conversation with them is about what their lifestyle is like. If they’re an active golfer I know that they’re going to end up getting their hernia fixed. If they’re sedentary, sitting at home in retirement, they don’t. So I think the next step in your research project should be to find out what the activity level is of these patients who are getting older and have asymptomatic hernias," said Dr. Zenilman, vice chair and regional director of surgery for the Washington, D.C., region, Johns Hopkins Medicine.

Dr. Fitzgibbons’ trial was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality with support from the American College of Surgeons. He reported having no financial conflicts.

INDIANAPOLIS – The luster has suddenly worn off the time-honored strategy of nonoperative watchful waiting in men with minimally symptomatic inguinal hernias.

New evidence indicates the vast majority of men with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic inguinal hernias will eventually come to surgery. This may not occur until years down the road, when their advanced age may render surgery more arduous.

"Although watchful waiting remains a safe strategy, even on long-term follow-up, patients who present to their physician to have their hernia evaluated, especially if elderly, should be informed that almost certainly they will come to surgery eventually ... The logical assumption is that watchful waiting is not an effective strategy, as with time almost all men cross over," Dr. Robert J. Fitzgibbons Jr. explained at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

He presented an extended follow-up of patients enrolled in a landmark randomized multicenter clinical trial, one of only two randomized studies ever done comparing watchful waiting versus routine surgical repair for men with minimally symptomatic inguinal hernia. In the earlier report by Dr. Fitzgibbons and coworkers, watchful waiting was deemed "an acceptable option" because only 23% of patients crossed over to surgery due to increased pain during the first 2 years of follow-up (JAMA 2006;295:285-92).

At the ASA meeting, however, he presented updated 10-year follow-up data on 167 patients from the cohort initially assigned to watchful waiting. The rate of crossover to surgery was 68% by 10 years, with a marked age-based divergence. Patients below age 65 had a 62% crossover rate, while those above that age had a 79% crossover rate, according to Dr. Fitzgibbons, professor of surgery and chief of the division of general surgery at Creighton University, Omaha, Neb.

The good news was that hernia incarceration was a rare event, occurring at a rate of just 0.2% per year over the course of 10 years.

"We as surgeons have been taught for many years that we must repair all our hernias to prevent hernia accidents. Well, only three patients in our whole study developed incarceration, for which they underwent surgery with no mortality," Dr. Fitzgibbons noted. "The risk of a hernia accident should not be considered an indication for surgery. Older studies in the literature which would suggest otherwise can no longer be considered relevant."

He offered a caveat regarding the study findings: Participants were enrolled after they sought medical attention because of their hernias, even though they were asymptomatic or only minimally symptomatic. So the study results are most applicable to men concerned enough about their hernias that they visit a physician for that reason.

"It’s probably not valid to extrapolate the conclusions in this study to the entire population of minimally symptomatic inguinal hernia patients," the surgeon said. "Physicians have been observing elderly patients for years and would be loath to believe a crossover rate this high."

Nevertheless, the results of this study are virtually identical to those of the only other randomized trial of watchful waiting, which was conducted by surgeons at the University of Glasgow. The most recent update from that study showed an estimated crossover rate in the watchful waiting group of 16% at 1 year, 54% at 5 years, and 72% at 7.5 years. As in the American study, the rate of acute incarceration was reassuringly small. The investigators concluded that watchful waiting appears pointless, and they recommended surgical repair for medically fit patients (Br. J. Surg. 2011;98:596-9).

Discussant Dr. Michael E. Zenilman commented that his own approach is to individualize patient management based in large part upon activity level.

"When I see patients who are 80 years old in the office with an asymptomatic hernia, my conversation with them is about what their lifestyle is like. If they’re an active golfer I know that they’re going to end up getting their hernia fixed. If they’re sedentary, sitting at home in retirement, they don’t. So I think the next step in your research project should be to find out what the activity level is of these patients who are getting older and have asymptomatic hernias," said Dr. Zenilman, vice chair and regional director of surgery for the Washington, D.C., region, Johns Hopkins Medicine.

Dr. Fitzgibbons’ trial was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality with support from the American College of Surgeons. He reported having no financial conflicts.

AT THE ASA ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: Sixty-eight percent of men randomized to nonoperative observation of their asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic inguinal hernia crossed over to surgical repair within 10 years.

Data source: This was an open registry long-term extension of a randomized trial in which 720 men with minimally symptomatic inguinal hernia were assigned to watchful waiting or routine surgical repair.

Disclosures: The sponsor was the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The presenter reported having no conflicts of interest.

Vascular surgeons get superior outcomes in aortic aneurysm repair

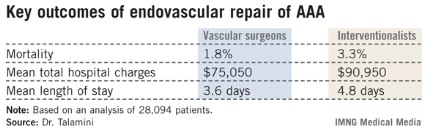

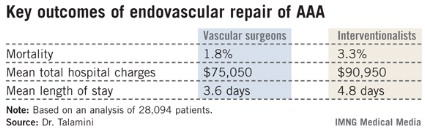

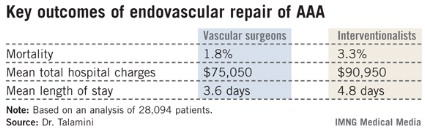

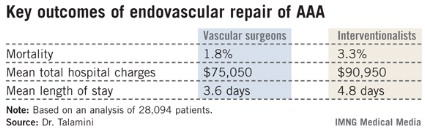

INDIANAPOLIS – Major outcomes in patients undergoing endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm are superior in terms of mortality, length of stay, and total hospital charges when the procedure is done by vascular surgeons rather than cardiologists or interventional radiologists, according to an analysis of a comprehensive national hospital database.

"Obviously these are striking findings," Dr. Mark A. Talamini noted in presenting the study results at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association. "We believe that health policy in support of selective referrals for aneurysm repair, or integrating interventionalists and vascular surgeons more effectively, should be considered."

He presented an outcomes analysis involving 28,094 patients who underwent endovascular implantation of a graft for an abdominal aortic aneurysm within the Nationwide Inpatient Sample during 2001-2009. This database, sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, receives input from a representative cross-section composed of 20% of U.S. hospitals. Dr. Talamini and coworkers were able to reliably determine whether an operator was a vascular surgeon, a cardiologist, or an interventional radiologist. Vascular surgeons performed 78.1% of the cases, while nonsurgeon interventionalists did the rest. Ninety-seven percent of patients presented with a nonruptured aneurysm.

The unadjusted differences in key outcomes between vascular surgeons and interventionalists were striking. Perhaps even more impressive were the differences following adjustment for operator volume, comorbid conditions, aneurysm rupture status, patient demographics and socioeconomic status, and hospital location and teaching status. The interventionalists’ patients had a 39% greater risk of mortality, an average of $20,000 more in total hospital charges, and a 1.4-day longer length of stay, reported Dr. Talamini, a nonvascular surgeon who is professor and chairman of the department of surgery at the University of California, San Diego.

Additional findings of interest were that the patients of high-volume operators (defined as those who performed more than 10 cases per year) had a 31% reduction in mortality risk regardless of operator specialty. In addition, high-volume operators averaged $10,000 per patient less in total hospital charges and shorter hospital length of stay by 1 full day. Undergoing aneurysm repair in a teaching hospital had no impact upon mortality or total charges, but was associated with an average 0.4-day greater length of stay, he continued.

Dr. Talamini offered two potential explanations for the disparate outcomes. One is that perhaps the patient populations of vascular surgeons and interventionalists differ in ways that were not accounted for in the multivariate analysis. The other possibility is that vascular surgeons achieve better outcomes because their training and experience are superior, allowing them to make better judgments about treatment than those of interventionalists.

"Obviously, this is the ‘we’re better than they are’ argument, and I hardly think we can assume that this is the case until we exhaust all other potential explanations. Further work using longitudinal databases with more detail hopefully will allow us to do just that," said Dr. Talamini.

Discussant Dr. K. Craig Kent called the study findings "very provocative."

"The moral of the story is expertise in disease is far more important than expertise in technology," declared Dr. Kent, professor and chairman of the department of surgery at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

"When I first became a vascular surgeon 25 years ago it was difficult to recruit to the specialty. There were few that wanted to care for a group of patients for whom procedures were long and tedious, reoperations were common, and outcomes weren’t always favorable," Dr. Kent recalled. "Fast forward to 2013, where everybody wants to be a vascular surgeon: cardiologists, interventional radiologists, nephrologists, dermatologists, vascular medicine physicians, and many others. Why the dramatic change? For the nonsurgeons, the reason is the development of minimally invasive technology that has allowed any specialist with catheter-based skills to participate in vascular care. But is it appropriate for nonsurgical specialists to treat vascular patients? The answer from this study is a resounding no."

Dr. Samuel E. Wilson, a vascular surgeon who was Dr. Talamini’s coinvestigator in the study, said he thinks patient selection is the key to understanding the outcome disparities.

"If you think about it, the vascular surgeon in his office has the ability to make an elective decision, carefully considered, and decide whether or not he’s going to actually do the procedure. The hospital-based radiologist may not have that opportunity; he receives a call, a procedure on an inpatient is requested, and he feels obligated to proceed. Another key aspect may be postoperative care. Vascular surgery patients receive their postoperative care under the direction of the surgeon," observed Dr. Wilson of the University of California, Irvine.

It’s worth noting, he added, that the outcomes for both vascular surgeons and interventionalists improved over the years of the study. The results are coming closer together over time, although significant differences remain.

Dr. Robert S. Rhodes said that general surgeons should be included in any further comparative effectiveness studies focused on endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms.

"Our data at the American Board of Surgery suggests that general surgeons who perform vascular surgery actually do so in substantial volume, so it may be that they’ve also acquired endovascular skills," said Dr. Rhodes, associate executive director for vascular surgery at the ABS.

None of the speakers reported having any financial conflicts.

INDIANAPOLIS – Major outcomes in patients undergoing endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm are superior in terms of mortality, length of stay, and total hospital charges when the procedure is done by vascular surgeons rather than cardiologists or interventional radiologists, according to an analysis of a comprehensive national hospital database.

"Obviously these are striking findings," Dr. Mark A. Talamini noted in presenting the study results at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association. "We believe that health policy in support of selective referrals for aneurysm repair, or integrating interventionalists and vascular surgeons more effectively, should be considered."

He presented an outcomes analysis involving 28,094 patients who underwent endovascular implantation of a graft for an abdominal aortic aneurysm within the Nationwide Inpatient Sample during 2001-2009. This database, sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, receives input from a representative cross-section composed of 20% of U.S. hospitals. Dr. Talamini and coworkers were able to reliably determine whether an operator was a vascular surgeon, a cardiologist, or an interventional radiologist. Vascular surgeons performed 78.1% of the cases, while nonsurgeon interventionalists did the rest. Ninety-seven percent of patients presented with a nonruptured aneurysm.

The unadjusted differences in key outcomes between vascular surgeons and interventionalists were striking. Perhaps even more impressive were the differences following adjustment for operator volume, comorbid conditions, aneurysm rupture status, patient demographics and socioeconomic status, and hospital location and teaching status. The interventionalists’ patients had a 39% greater risk of mortality, an average of $20,000 more in total hospital charges, and a 1.4-day longer length of stay, reported Dr. Talamini, a nonvascular surgeon who is professor and chairman of the department of surgery at the University of California, San Diego.

Additional findings of interest were that the patients of high-volume operators (defined as those who performed more than 10 cases per year) had a 31% reduction in mortality risk regardless of operator specialty. In addition, high-volume operators averaged $10,000 per patient less in total hospital charges and shorter hospital length of stay by 1 full day. Undergoing aneurysm repair in a teaching hospital had no impact upon mortality or total charges, but was associated with an average 0.4-day greater length of stay, he continued.

Dr. Talamini offered two potential explanations for the disparate outcomes. One is that perhaps the patient populations of vascular surgeons and interventionalists differ in ways that were not accounted for in the multivariate analysis. The other possibility is that vascular surgeons achieve better outcomes because their training and experience are superior, allowing them to make better judgments about treatment than those of interventionalists.

"Obviously, this is the ‘we’re better than they are’ argument, and I hardly think we can assume that this is the case until we exhaust all other potential explanations. Further work using longitudinal databases with more detail hopefully will allow us to do just that," said Dr. Talamini.

Discussant Dr. K. Craig Kent called the study findings "very provocative."

"The moral of the story is expertise in disease is far more important than expertise in technology," declared Dr. Kent, professor and chairman of the department of surgery at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

"When I first became a vascular surgeon 25 years ago it was difficult to recruit to the specialty. There were few that wanted to care for a group of patients for whom procedures were long and tedious, reoperations were common, and outcomes weren’t always favorable," Dr. Kent recalled. "Fast forward to 2013, where everybody wants to be a vascular surgeon: cardiologists, interventional radiologists, nephrologists, dermatologists, vascular medicine physicians, and many others. Why the dramatic change? For the nonsurgeons, the reason is the development of minimally invasive technology that has allowed any specialist with catheter-based skills to participate in vascular care. But is it appropriate for nonsurgical specialists to treat vascular patients? The answer from this study is a resounding no."

Dr. Samuel E. Wilson, a vascular surgeon who was Dr. Talamini’s coinvestigator in the study, said he thinks patient selection is the key to understanding the outcome disparities.

"If you think about it, the vascular surgeon in his office has the ability to make an elective decision, carefully considered, and decide whether or not he’s going to actually do the procedure. The hospital-based radiologist may not have that opportunity; he receives a call, a procedure on an inpatient is requested, and he feels obligated to proceed. Another key aspect may be postoperative care. Vascular surgery patients receive their postoperative care under the direction of the surgeon," observed Dr. Wilson of the University of California, Irvine.

It’s worth noting, he added, that the outcomes for both vascular surgeons and interventionalists improved over the years of the study. The results are coming closer together over time, although significant differences remain.

Dr. Robert S. Rhodes said that general surgeons should be included in any further comparative effectiveness studies focused on endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms.

"Our data at the American Board of Surgery suggests that general surgeons who perform vascular surgery actually do so in substantial volume, so it may be that they’ve also acquired endovascular skills," said Dr. Rhodes, associate executive director for vascular surgery at the ABS.