User login

Low vasculitis risk with TNF inhibitors

GLASGOW – Treatment with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis is associated with a low risk of vasculitis-like events, according to a large analysis of data from the United Kingdom.

Investigators using data from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Rheumatoid Arthritis (BSRBR-RA) found that the crude incidence rate was 16 cases per 10,000 person-years among TNF-inhibitor users versus seven cases per 10,000 person-years among users of nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (nbDMARDs) such as methotrexate and sulfasalazine.

Although the risk was slightly higher among anti-TNF than nbDMARD users, the propensity score fully adjusted hazard ratio for a first vasculitis-like event was 1.27, comparing the anti-TNF drugs with nbDMARDs, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.40-4.04.

“This is the first prospective observational study to systematically look at the risk of vasculitis-like events” in patients with RA treated with anti-TNF agents, Dr. Meghna Jani said at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

Dr. Jani of the Arthritis Research UK Centre for Epidemiology at the University of Manchester (England) explained that the reason for looking at this topic was that vasculitis-like events had been reported in case series and single-center studies, but these prior reports were too small to be able to estimate exactly how big a problem this was.

“Anti-TNF agents are associated with the development of a number of autoantibodies, including antinuclear antibodies and antidrug antibodies, and ANCA [antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody],” she observed.

“We know that a small proportion of these patients may then go on to develop autoimmune diseases, some independent of autoantibodies,” she added. The most common of these is vasculitis, including cutaneous vasculitis.

Vasculitis is a somewhat paradoxical adverse event, she noted, in that it has been associated with anti-TNF therapy, but these drugs can also be used to treat it.

Now in its 15th year, the BSRBR-RA is the largest ongoing cohort of patients treated with biologic agents for rheumatic disease and provides one of the best sources of data to examine the risk for vasculitis-like events Dr. Jani observed. The aims were to look at the respective risks as well as to see if there were any particular predictive factors.

The current analysis included more than 16,000 patients enrolled in the BSRBR-RA between 2001 and 2015, of whom 12,745 were newly started on an anti-TNF drug and 3,640 were receiving nbDMARDs and were also biologic naive. The mean age of patients in the two groups was 56 and 60 years, 76% and 72% were female, with a mean Disease Activity Score (DAS28) of 6.5 and 5.1 and median disease duration of 11 and 6 years, respectively.

After more than 52,428 person-years of exposure and a median of 5.1 years of follow-up, 81 vasculitis-like events occurred in the anti-TNF therapy group. Vasculitis-like events were attributed to treatment only if they had occurred within 90 days of starting the drug. Follow-up stopped after a first event; if there was a switch to another biologic drug; and at death, the last clinical follow-up, or the end of the analysis period (May 31, 2015).

In comparison, there were 20,635 person-years of exposure and 6.5 years’ follow-up in the nbDMARD group, with 14 vasculitis-like events reported during this time.

A sensitivity analysis was performed excluding patients who had nail-fold vasculitis at baseline, had vasculitis due to a possible secondary cause such as infection, and were taking any other medications associated with vasculitis-like events. Results showed a similar risk for a first vasculitis event between anti-TNF and nbDMARD users (aHR = 1.05; 95% CI, 0.32-3.45).

Looking at the risk of vasculitis events for individual anti-TNF drugs, there initially appeared to be a higher risk for patients taking infliximab (n = 3,292) and etanercept (n = 4,450) but not for those taking adalimumab (n = 4,312) versus nbDMARDs, with crude incidence rates of 10, 17, and 11 per 10,000 person-years; after adjustment, these differences were not significant (aHRs of 1.55, 1.72, and 0.77, respectively, with 95% CIs crossing 1.0). A crude rate for certolizumab could not be calculated as there were no vasculitis events reported but there were only 691 patients enrolled in the BSRBR-RA at the time of the analysis who had been exposed to the drug.

“The risk of the event was highest in the first year of treatment, followed by reduction over time,” Dr. Jani reported. “Reassuringly, up to two-thirds of patients in both cohorts had manifestations that were just limited to cutaneous involvement,” she said.

The most common systemic presentation was digital ischemia, affecting 14% of patients treated with anti-TNFs and 14% of those given nbDMARDs. Neurologic involvement was also seen in both groups of patients (7% vs. 7%), but new nail-fold vasculitis (17% vs. 0%), respiratory involvement (4% vs. 0%), associated thrombotic events (5% vs. 0%), and renal involvement (2.5% vs. 0%) were seen in TNF inhibitor-treated patients only.

Ten anti-TNF–treated patients and one nbDMARD-treated patient needed treatment for the vasculitis-like event, and three patients in the anti-TNF cohort died as a result of the event, all of whom had multisystem organ involvement and one of whom had cytoplasmic ANCA-positive vasculitis.

Treatment with methotrexate or sulfasalazine at baseline was associated with a lower risk for vasculitis-like events, while seropositive status, disease duration, DAS28, and HAQ scores were associated with an increased risk for such events.

The BSRBR-RA receives restricted income financial support from Abbvie, Amgen, Swedish Orphan Biovitram (SOBI), Merck, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB Pharma. Dr. Jani disclosed she has received honoraria from Pfizer, Abbvie, and UCB Pharma.

GLASGOW – Treatment with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis is associated with a low risk of vasculitis-like events, according to a large analysis of data from the United Kingdom.

Investigators using data from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Rheumatoid Arthritis (BSRBR-RA) found that the crude incidence rate was 16 cases per 10,000 person-years among TNF-inhibitor users versus seven cases per 10,000 person-years among users of nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (nbDMARDs) such as methotrexate and sulfasalazine.

Although the risk was slightly higher among anti-TNF than nbDMARD users, the propensity score fully adjusted hazard ratio for a first vasculitis-like event was 1.27, comparing the anti-TNF drugs with nbDMARDs, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.40-4.04.

“This is the first prospective observational study to systematically look at the risk of vasculitis-like events” in patients with RA treated with anti-TNF agents, Dr. Meghna Jani said at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

Dr. Jani of the Arthritis Research UK Centre for Epidemiology at the University of Manchester (England) explained that the reason for looking at this topic was that vasculitis-like events had been reported in case series and single-center studies, but these prior reports were too small to be able to estimate exactly how big a problem this was.

“Anti-TNF agents are associated with the development of a number of autoantibodies, including antinuclear antibodies and antidrug antibodies, and ANCA [antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody],” she observed.

“We know that a small proportion of these patients may then go on to develop autoimmune diseases, some independent of autoantibodies,” she added. The most common of these is vasculitis, including cutaneous vasculitis.

Vasculitis is a somewhat paradoxical adverse event, she noted, in that it has been associated with anti-TNF therapy, but these drugs can also be used to treat it.

Now in its 15th year, the BSRBR-RA is the largest ongoing cohort of patients treated with biologic agents for rheumatic disease and provides one of the best sources of data to examine the risk for vasculitis-like events Dr. Jani observed. The aims were to look at the respective risks as well as to see if there were any particular predictive factors.

The current analysis included more than 16,000 patients enrolled in the BSRBR-RA between 2001 and 2015, of whom 12,745 were newly started on an anti-TNF drug and 3,640 were receiving nbDMARDs and were also biologic naive. The mean age of patients in the two groups was 56 and 60 years, 76% and 72% were female, with a mean Disease Activity Score (DAS28) of 6.5 and 5.1 and median disease duration of 11 and 6 years, respectively.

After more than 52,428 person-years of exposure and a median of 5.1 years of follow-up, 81 vasculitis-like events occurred in the anti-TNF therapy group. Vasculitis-like events were attributed to treatment only if they had occurred within 90 days of starting the drug. Follow-up stopped after a first event; if there was a switch to another biologic drug; and at death, the last clinical follow-up, or the end of the analysis period (May 31, 2015).

In comparison, there were 20,635 person-years of exposure and 6.5 years’ follow-up in the nbDMARD group, with 14 vasculitis-like events reported during this time.

A sensitivity analysis was performed excluding patients who had nail-fold vasculitis at baseline, had vasculitis due to a possible secondary cause such as infection, and were taking any other medications associated with vasculitis-like events. Results showed a similar risk for a first vasculitis event between anti-TNF and nbDMARD users (aHR = 1.05; 95% CI, 0.32-3.45).

Looking at the risk of vasculitis events for individual anti-TNF drugs, there initially appeared to be a higher risk for patients taking infliximab (n = 3,292) and etanercept (n = 4,450) but not for those taking adalimumab (n = 4,312) versus nbDMARDs, with crude incidence rates of 10, 17, and 11 per 10,000 person-years; after adjustment, these differences were not significant (aHRs of 1.55, 1.72, and 0.77, respectively, with 95% CIs crossing 1.0). A crude rate for certolizumab could not be calculated as there were no vasculitis events reported but there were only 691 patients enrolled in the BSRBR-RA at the time of the analysis who had been exposed to the drug.

“The risk of the event was highest in the first year of treatment, followed by reduction over time,” Dr. Jani reported. “Reassuringly, up to two-thirds of patients in both cohorts had manifestations that were just limited to cutaneous involvement,” she said.

The most common systemic presentation was digital ischemia, affecting 14% of patients treated with anti-TNFs and 14% of those given nbDMARDs. Neurologic involvement was also seen in both groups of patients (7% vs. 7%), but new nail-fold vasculitis (17% vs. 0%), respiratory involvement (4% vs. 0%), associated thrombotic events (5% vs. 0%), and renal involvement (2.5% vs. 0%) were seen in TNF inhibitor-treated patients only.

Ten anti-TNF–treated patients and one nbDMARD-treated patient needed treatment for the vasculitis-like event, and three patients in the anti-TNF cohort died as a result of the event, all of whom had multisystem organ involvement and one of whom had cytoplasmic ANCA-positive vasculitis.

Treatment with methotrexate or sulfasalazine at baseline was associated with a lower risk for vasculitis-like events, while seropositive status, disease duration, DAS28, and HAQ scores were associated with an increased risk for such events.

The BSRBR-RA receives restricted income financial support from Abbvie, Amgen, Swedish Orphan Biovitram (SOBI), Merck, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB Pharma. Dr. Jani disclosed she has received honoraria from Pfizer, Abbvie, and UCB Pharma.

GLASGOW – Treatment with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis is associated with a low risk of vasculitis-like events, according to a large analysis of data from the United Kingdom.

Investigators using data from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Rheumatoid Arthritis (BSRBR-RA) found that the crude incidence rate was 16 cases per 10,000 person-years among TNF-inhibitor users versus seven cases per 10,000 person-years among users of nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (nbDMARDs) such as methotrexate and sulfasalazine.

Although the risk was slightly higher among anti-TNF than nbDMARD users, the propensity score fully adjusted hazard ratio for a first vasculitis-like event was 1.27, comparing the anti-TNF drugs with nbDMARDs, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.40-4.04.

“This is the first prospective observational study to systematically look at the risk of vasculitis-like events” in patients with RA treated with anti-TNF agents, Dr. Meghna Jani said at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

Dr. Jani of the Arthritis Research UK Centre for Epidemiology at the University of Manchester (England) explained that the reason for looking at this topic was that vasculitis-like events had been reported in case series and single-center studies, but these prior reports were too small to be able to estimate exactly how big a problem this was.

“Anti-TNF agents are associated with the development of a number of autoantibodies, including antinuclear antibodies and antidrug antibodies, and ANCA [antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody],” she observed.

“We know that a small proportion of these patients may then go on to develop autoimmune diseases, some independent of autoantibodies,” she added. The most common of these is vasculitis, including cutaneous vasculitis.

Vasculitis is a somewhat paradoxical adverse event, she noted, in that it has been associated with anti-TNF therapy, but these drugs can also be used to treat it.

Now in its 15th year, the BSRBR-RA is the largest ongoing cohort of patients treated with biologic agents for rheumatic disease and provides one of the best sources of data to examine the risk for vasculitis-like events Dr. Jani observed. The aims were to look at the respective risks as well as to see if there were any particular predictive factors.

The current analysis included more than 16,000 patients enrolled in the BSRBR-RA between 2001 and 2015, of whom 12,745 were newly started on an anti-TNF drug and 3,640 were receiving nbDMARDs and were also biologic naive. The mean age of patients in the two groups was 56 and 60 years, 76% and 72% were female, with a mean Disease Activity Score (DAS28) of 6.5 and 5.1 and median disease duration of 11 and 6 years, respectively.

After more than 52,428 person-years of exposure and a median of 5.1 years of follow-up, 81 vasculitis-like events occurred in the anti-TNF therapy group. Vasculitis-like events were attributed to treatment only if they had occurred within 90 days of starting the drug. Follow-up stopped after a first event; if there was a switch to another biologic drug; and at death, the last clinical follow-up, or the end of the analysis period (May 31, 2015).

In comparison, there were 20,635 person-years of exposure and 6.5 years’ follow-up in the nbDMARD group, with 14 vasculitis-like events reported during this time.

A sensitivity analysis was performed excluding patients who had nail-fold vasculitis at baseline, had vasculitis due to a possible secondary cause such as infection, and were taking any other medications associated with vasculitis-like events. Results showed a similar risk for a first vasculitis event between anti-TNF and nbDMARD users (aHR = 1.05; 95% CI, 0.32-3.45).

Looking at the risk of vasculitis events for individual anti-TNF drugs, there initially appeared to be a higher risk for patients taking infliximab (n = 3,292) and etanercept (n = 4,450) but not for those taking adalimumab (n = 4,312) versus nbDMARDs, with crude incidence rates of 10, 17, and 11 per 10,000 person-years; after adjustment, these differences were not significant (aHRs of 1.55, 1.72, and 0.77, respectively, with 95% CIs crossing 1.0). A crude rate for certolizumab could not be calculated as there were no vasculitis events reported but there were only 691 patients enrolled in the BSRBR-RA at the time of the analysis who had been exposed to the drug.

“The risk of the event was highest in the first year of treatment, followed by reduction over time,” Dr. Jani reported. “Reassuringly, up to two-thirds of patients in both cohorts had manifestations that were just limited to cutaneous involvement,” she said.

The most common systemic presentation was digital ischemia, affecting 14% of patients treated with anti-TNFs and 14% of those given nbDMARDs. Neurologic involvement was also seen in both groups of patients (7% vs. 7%), but new nail-fold vasculitis (17% vs. 0%), respiratory involvement (4% vs. 0%), associated thrombotic events (5% vs. 0%), and renal involvement (2.5% vs. 0%) were seen in TNF inhibitor-treated patients only.

Ten anti-TNF–treated patients and one nbDMARD-treated patient needed treatment for the vasculitis-like event, and three patients in the anti-TNF cohort died as a result of the event, all of whom had multisystem organ involvement and one of whom had cytoplasmic ANCA-positive vasculitis.

Treatment with methotrexate or sulfasalazine at baseline was associated with a lower risk for vasculitis-like events, while seropositive status, disease duration, DAS28, and HAQ scores were associated with an increased risk for such events.

The BSRBR-RA receives restricted income financial support from Abbvie, Amgen, Swedish Orphan Biovitram (SOBI), Merck, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB Pharma. Dr. Jani disclosed she has received honoraria from Pfizer, Abbvie, and UCB Pharma.

AT RHEUMATOLOGY 2016

Key clinical point: There is a low risk of vasculitis-like events with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors.

Major finding: Crude incidence rates for vasculitis-like events were 16/10,000 person-years with TNF-inhibitor therapy and 7/10,000 person-years with nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

Data source: British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Rheumatoid Arthritis of 12,745 TNF-inhibitor and 3,640 nbDMARD users.

Disclosures: The BSRBR-RA receives restricted income financial support from Abbvie, Amgen, Swedish Orphan Biovitram (SOBI), Merck, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB Pharma. Dr. Jani disclosed she has received honoraria from Pfizer, Abbvie, and UCB Pharma.

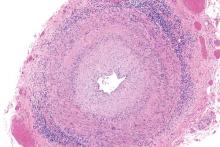

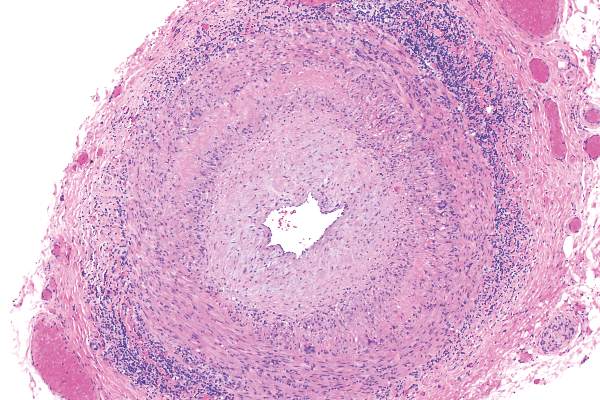

Vascular disease linked to sight loss in giant cell arteritis

GLASGOW – People with giant cell arteritis may be more likely to go blind if they have underlying vascular disease, according to an analysis of the Diagnostic and Classification Criteria in Vasculitis Study.

The results of the analysis showed that 7.9% of patients with this common type of vasculitis go blind in at least one eye within 6 months of a diagnosis, and that those with a history of peripheral vascular disease (PVD) could be up to 10 times more at risk than those without additional vascular comorbidity.

“This is the first multinational study for patients with [giant cell arteritis], and it shows that blindness is a significant problem,” said Dr. Max Yates of the University of East Anglia in Norwich, England, who presented the findings at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference. Blindness was defined as complete visual loss rather than by a full ophthalmology assessment, so the findings probably underplay the problem in patients with some form of visual loss, he observed. Visual disturbance had been noted in 42.9% of the patients who were studied at the first clinic review.

“It is interesting that there is the association with vascular disease,” Dr. Yates said. “Perhaps we need greater vigilance in those people who already have a diagnosis of vascular disease [and] to really watch and monitor those people carefully for sight loss.”

The Diagnostic and Classification Criteria in Vasculitis Study (DCVAS) is an ongoing project designed to develop and then validate new classification and diagnostic criteria for systemic vasculitis that can be used routinely in clinical practice and in clinical trials. So far, more than 3,500 participants over age 18 have been recruited from secondary care clinics, and of those, 2,000 have a new or established diagnosis of vasculitis. The others have a similar presentation but an alternative diagnosis.

A total of 433 patients participating in the DCVAS were identified as having GCA with more than 75% diagnostic certainty, of which 93% fulfilled the 1990 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for GCA and just over half (54%) had a positive temporal artery biopsy. Visual loss was recorded by completion of the Vasculitis Damage Index (VDI) 6 months after diagnosis.

Two-thirds of patients studied were female, the median age at diagnosis was 73 years, 40% had jaw claudication, 34% had lost weight, and 16% presented with a fever. In addition, 9.2% had diabetes, 3.2% a prior stroke, and 2.5% had PVD.

Looking for predictive factors, baseline laboratory findings such as the presence of anemia, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, or platelet counts were not associated with sight loss. Dr. Yates noted in discussion that the baseline ESR range was 35-120 mm/h and the CRP ranged from 12 to over 100 mg/dL in the patients studied.

However, prior vascular disease was found to be predictive of later blindness. The odds ratio (OR) for being blind in at least one eye 6 months after a GCA diagnosis was 10.44 for PVD, with the 95% confidence interval (CI) ranging from 2.94 to 37.03. A prior diagnosis of cerebral vascular accident (OR, 4.47; 95% CI, 1.30-15.41), and diabetes (OR, 2.48; 95% CI, 0.98-6.25) also upped the risk for complete sight loss at 6 months.

Dr. Yates noted that patients were selected from multiple clinics across secondary care, so there should be better generalizability than in prior, single-center studies. However, there could be some residual referral bias.

During discussion, it was pointed out that it would be helpful to know the rate of blindness in patients taking steroids, as this was one of the major reasons for emergency rheumatology calls at one clinic, a delegate observed.

“Giant cell arteritis is really the major rheumatology emergency for practicing clinicians. We recently set up a rheumatology day service and get usually 8-10 calls about it per day,” the delegate said. “It’s often said that once a patient is on any dose of steroids, there is not risk of them going blind.” There is a lot of angst about whether it is safe to use higher doses (60 mg vs. 40 mg) and “it’s important for us as clinicians to be able to reassure people.”

Dr. Yates noted that a prospective trial would be needed to answer the question and that trials were planned. “We don’t have any data on treatment,” he said. “So we’re unable to say whether steroids were started instantly or whether there was any improvement in the visual function of these people.” Long-term complications also would be something to look at, particularly in older people who have an increased risk for eye problems such as cataracts, and could be at higher risk for visual problems if treated with steroids or other agents.

The DCVAS study is supported by the ACR and is funded by the European League Against Rheumatism and the Vasculitis Foundation. Dr. Yates reported that he had no relevant disclosures.

GLASGOW – People with giant cell arteritis may be more likely to go blind if they have underlying vascular disease, according to an analysis of the Diagnostic and Classification Criteria in Vasculitis Study.

The results of the analysis showed that 7.9% of patients with this common type of vasculitis go blind in at least one eye within 6 months of a diagnosis, and that those with a history of peripheral vascular disease (PVD) could be up to 10 times more at risk than those without additional vascular comorbidity.

“This is the first multinational study for patients with [giant cell arteritis], and it shows that blindness is a significant problem,” said Dr. Max Yates of the University of East Anglia in Norwich, England, who presented the findings at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference. Blindness was defined as complete visual loss rather than by a full ophthalmology assessment, so the findings probably underplay the problem in patients with some form of visual loss, he observed. Visual disturbance had been noted in 42.9% of the patients who were studied at the first clinic review.

“It is interesting that there is the association with vascular disease,” Dr. Yates said. “Perhaps we need greater vigilance in those people who already have a diagnosis of vascular disease [and] to really watch and monitor those people carefully for sight loss.”

The Diagnostic and Classification Criteria in Vasculitis Study (DCVAS) is an ongoing project designed to develop and then validate new classification and diagnostic criteria for systemic vasculitis that can be used routinely in clinical practice and in clinical trials. So far, more than 3,500 participants over age 18 have been recruited from secondary care clinics, and of those, 2,000 have a new or established diagnosis of vasculitis. The others have a similar presentation but an alternative diagnosis.

A total of 433 patients participating in the DCVAS were identified as having GCA with more than 75% diagnostic certainty, of which 93% fulfilled the 1990 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for GCA and just over half (54%) had a positive temporal artery biopsy. Visual loss was recorded by completion of the Vasculitis Damage Index (VDI) 6 months after diagnosis.

Two-thirds of patients studied were female, the median age at diagnosis was 73 years, 40% had jaw claudication, 34% had lost weight, and 16% presented with a fever. In addition, 9.2% had diabetes, 3.2% a prior stroke, and 2.5% had PVD.

Looking for predictive factors, baseline laboratory findings such as the presence of anemia, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, or platelet counts were not associated with sight loss. Dr. Yates noted in discussion that the baseline ESR range was 35-120 mm/h and the CRP ranged from 12 to over 100 mg/dL in the patients studied.

However, prior vascular disease was found to be predictive of later blindness. The odds ratio (OR) for being blind in at least one eye 6 months after a GCA diagnosis was 10.44 for PVD, with the 95% confidence interval (CI) ranging from 2.94 to 37.03. A prior diagnosis of cerebral vascular accident (OR, 4.47; 95% CI, 1.30-15.41), and diabetes (OR, 2.48; 95% CI, 0.98-6.25) also upped the risk for complete sight loss at 6 months.

Dr. Yates noted that patients were selected from multiple clinics across secondary care, so there should be better generalizability than in prior, single-center studies. However, there could be some residual referral bias.

During discussion, it was pointed out that it would be helpful to know the rate of blindness in patients taking steroids, as this was one of the major reasons for emergency rheumatology calls at one clinic, a delegate observed.

“Giant cell arteritis is really the major rheumatology emergency for practicing clinicians. We recently set up a rheumatology day service and get usually 8-10 calls about it per day,” the delegate said. “It’s often said that once a patient is on any dose of steroids, there is not risk of them going blind.” There is a lot of angst about whether it is safe to use higher doses (60 mg vs. 40 mg) and “it’s important for us as clinicians to be able to reassure people.”

Dr. Yates noted that a prospective trial would be needed to answer the question and that trials were planned. “We don’t have any data on treatment,” he said. “So we’re unable to say whether steroids were started instantly or whether there was any improvement in the visual function of these people.” Long-term complications also would be something to look at, particularly in older people who have an increased risk for eye problems such as cataracts, and could be at higher risk for visual problems if treated with steroids or other agents.

The DCVAS study is supported by the ACR and is funded by the European League Against Rheumatism and the Vasculitis Foundation. Dr. Yates reported that he had no relevant disclosures.

GLASGOW – People with giant cell arteritis may be more likely to go blind if they have underlying vascular disease, according to an analysis of the Diagnostic and Classification Criteria in Vasculitis Study.

The results of the analysis showed that 7.9% of patients with this common type of vasculitis go blind in at least one eye within 6 months of a diagnosis, and that those with a history of peripheral vascular disease (PVD) could be up to 10 times more at risk than those without additional vascular comorbidity.

“This is the first multinational study for patients with [giant cell arteritis], and it shows that blindness is a significant problem,” said Dr. Max Yates of the University of East Anglia in Norwich, England, who presented the findings at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference. Blindness was defined as complete visual loss rather than by a full ophthalmology assessment, so the findings probably underplay the problem in patients with some form of visual loss, he observed. Visual disturbance had been noted in 42.9% of the patients who were studied at the first clinic review.

“It is interesting that there is the association with vascular disease,” Dr. Yates said. “Perhaps we need greater vigilance in those people who already have a diagnosis of vascular disease [and] to really watch and monitor those people carefully for sight loss.”

The Diagnostic and Classification Criteria in Vasculitis Study (DCVAS) is an ongoing project designed to develop and then validate new classification and diagnostic criteria for systemic vasculitis that can be used routinely in clinical practice and in clinical trials. So far, more than 3,500 participants over age 18 have been recruited from secondary care clinics, and of those, 2,000 have a new or established diagnosis of vasculitis. The others have a similar presentation but an alternative diagnosis.

A total of 433 patients participating in the DCVAS were identified as having GCA with more than 75% diagnostic certainty, of which 93% fulfilled the 1990 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for GCA and just over half (54%) had a positive temporal artery biopsy. Visual loss was recorded by completion of the Vasculitis Damage Index (VDI) 6 months after diagnosis.

Two-thirds of patients studied were female, the median age at diagnosis was 73 years, 40% had jaw claudication, 34% had lost weight, and 16% presented with a fever. In addition, 9.2% had diabetes, 3.2% a prior stroke, and 2.5% had PVD.

Looking for predictive factors, baseline laboratory findings such as the presence of anemia, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, or platelet counts were not associated with sight loss. Dr. Yates noted in discussion that the baseline ESR range was 35-120 mm/h and the CRP ranged from 12 to over 100 mg/dL in the patients studied.

However, prior vascular disease was found to be predictive of later blindness. The odds ratio (OR) for being blind in at least one eye 6 months after a GCA diagnosis was 10.44 for PVD, with the 95% confidence interval (CI) ranging from 2.94 to 37.03. A prior diagnosis of cerebral vascular accident (OR, 4.47; 95% CI, 1.30-15.41), and diabetes (OR, 2.48; 95% CI, 0.98-6.25) also upped the risk for complete sight loss at 6 months.

Dr. Yates noted that patients were selected from multiple clinics across secondary care, so there should be better generalizability than in prior, single-center studies. However, there could be some residual referral bias.

During discussion, it was pointed out that it would be helpful to know the rate of blindness in patients taking steroids, as this was one of the major reasons for emergency rheumatology calls at one clinic, a delegate observed.

“Giant cell arteritis is really the major rheumatology emergency for practicing clinicians. We recently set up a rheumatology day service and get usually 8-10 calls about it per day,” the delegate said. “It’s often said that once a patient is on any dose of steroids, there is not risk of them going blind.” There is a lot of angst about whether it is safe to use higher doses (60 mg vs. 40 mg) and “it’s important for us as clinicians to be able to reassure people.”

Dr. Yates noted that a prospective trial would be needed to answer the question and that trials were planned. “We don’t have any data on treatment,” he said. “So we’re unable to say whether steroids were started instantly or whether there was any improvement in the visual function of these people.” Long-term complications also would be something to look at, particularly in older people who have an increased risk for eye problems such as cataracts, and could be at higher risk for visual problems if treated with steroids or other agents.

The DCVAS study is supported by the ACR and is funded by the European League Against Rheumatism and the Vasculitis Foundation. Dr. Yates reported that he had no relevant disclosures.

AT RHEUMATOLOGY 2016

Key clinical point: Patients with vascular disease who develop giant cell arteritis may require careful monitoring for sight loss.

Major finding: Overall, 42.9% of patients had some visual disturbance at first clinic review; 7.9% were blind at 6 months.

Data source: Analysis of 433 patients newly diagnosed with GCA participating in the Diagnostic and Classification Criteria in Vasculitis Study (DCVAS).

Disclosures: The DCVAS study is supported by the American College of Rheumatology and is funded by the European League Against Rheumatism and the Vasculitis Foundation. Dr. Yates reported that he had no relevant disclosures.

TRACTISS ends rituximab hopes for Sjögren’s syndrome

GLASGOW – Rituximab is unlikely to work as a treatment for Sjögren’s syndrome, according to a sneak peak of results from a multicenter study.

The study, the Trial of Anti–B Cell Therapy in Patients With Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome (TRACTISS), showed that there were no significant differences between the active and placebo arms in terms of alleviating oral dryness or fatigue, Dr. Simon J. Bowman, a principal investigator for the trial, observed at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference. In addition, no difference was found in the EULAR Sjögren’s syndrome disease activity index (ESSDAI).

In TRACTISS, 110 patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome received two courses of rituximab (Rituxan) or placebo in addition to standard therapy, and they were followed up for up to 48 weeks (BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:21).

Dr. Bowman, a consultant rheumatologist and honorary professor of rheumatology at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham, England, noted that there was some indication of an effect of rituximab on fatigue and oral dryness in another large, randomized, controlled trial – the Tolerance and Efficacy of Rituximab in Sjögren’s syndrome (TEARS) study – a couple of years ago (Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72[6]:1026-31), but these were not the primary endpoints of the study, so those results were essentially negative.

Calling the TRACTISS findings something of disappointment, Dr. Bowman said: “I think we’ll have to wait and see, but having had two big formal trials, I have to say that it doesn’t look like rituximab on its own is going to be any [great] success.”

Hopes were high for rituximab 5 years ago, when recruitment into the TRACTISS trial started, principally because drugs like rituximab already were available for use, Dr. Bowman said at the time. The focus was on anti–B cell therapies, because not only were they available but several features of Sjögren’s syndrome potentially are linked to B-cell activity, such as fatigue in about two-thirds of patients, the presence of anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies in about 40% of patients, and lymphoma in about 5% of patients. Also, several small studies had suggested rituximab might prove beneficial.

Other B-cell therapeutic options

Clearly, other B-cell targets might offer alternative therapeutic approaches. One of those under investigation is using belimumab (Benlysta) to target B cell–activating factor (BAFF) or B-cell lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS). Results of the BELISS study, a small, open-label, phase II trial in 30 patients with Sjögren’s syndrome (Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74[3]:526-31) showed there were some improvements in the ESSDAI and the EULAR Sjögren’s Syndrome Patient-Reported Index (ESSPRI). The improvements were great enough to justify proceeding to a larger clinical trial.

Perhaps the real hope for biologic therapy lies in targeting the T cells for which there is a very good rationale, said Wan-Fai Ng, Ph.D., professor of rheumatology at Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, England. Various approaches are available, and in addition, there have been some “encouraging” data from early-phase clinical trials.

Abatacept (Orencia), for example, has been looked at in a few trials, with positive drops in ESSDAI and other endpoints, and currently, there is an ongoing phase III trial in 88 patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. There are a couple of ongoing phase II trials, one with the anti-CD40 molecule CFZ533 and another with the anti-B7RP1 molecule AMG 557.

Dr. Ng noted that a trial of efalizumab (Raptiva) had terminated because of an increased risk for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. In addition, a couple of other molecules, rhIL-2 and alefacept (Amevive), are under investigation, he said.

Four additional therapeutic targets

Other novel approaches to developing biologic therapy for Sjögren’s were summarized by Dr. Francesca Barone, a senior lecturer at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham, England. She described four strategies, the first of which was targeting the cross talk between antigen-presenting dendritic cells and T cells using a novel molecule RO5459072 that targets a protein called cathepsin S. Cathepsin S is involved in the assembly of the major histocompatibility complex II protein, and by interfering with this process, the theory is that the effector T-helper cell response will be muted and T-cell interaction with B cells will be decreased. A phase II “proof-of-concept” trial is underway with RO5459072 and will recruit 70 patients, she said.

A second strategy is targeting intracellular B cell signaling by targeting P13 kinase delta with UCB 5857. P13 kinase delta catalyzes B cell activation and “is really at the core of the biology of the B cell,” Dr. Barone observed. A phase II trial with UCB 5857 is planned in 52 patients.

A third approach is to target lymphoneogenesis more generally by interfering with the production of the chemokines CXCL13 and CXCL12. This might be achieved via interleukin (IL)–17 and IL-22 blockade. A trial with the novel agent baminercept, a lymphotoxin beta receptor fusion protein. However, that trial was stopped in 2014 for technical reasons.

A fourth strategy is to use combination “sandwich” treatment, consisting of belimumab, rituximab, and then belimumab again. “This is what is going to come next, putting two drugs together,” Dr. Barone said. A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial now open to recruitment aims to investigate whether there is value in this approach.

“We’ve bombarded you with a lot of targets,” Dr. Barone observed. “What do we believe is going to be the best one is very, very unclear.”

TRACTISS was funded by Arthritis Research UK with rituximab provided by Roche. Dr. Bowman did not provide any disclosures but previously has been a consultant for Roche, UCB Pharma, and Merck-Serono. Dr. Ng reported no conflicts of interest, and Dr. Barone disclosed consultancy or collaboration with UCB Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline, Celgene, Eli Lilly, and Roche.

GLASGOW – Rituximab is unlikely to work as a treatment for Sjögren’s syndrome, according to a sneak peak of results from a multicenter study.

The study, the Trial of Anti–B Cell Therapy in Patients With Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome (TRACTISS), showed that there were no significant differences between the active and placebo arms in terms of alleviating oral dryness or fatigue, Dr. Simon J. Bowman, a principal investigator for the trial, observed at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference. In addition, no difference was found in the EULAR Sjögren’s syndrome disease activity index (ESSDAI).

In TRACTISS, 110 patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome received two courses of rituximab (Rituxan) or placebo in addition to standard therapy, and they were followed up for up to 48 weeks (BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:21).

Dr. Bowman, a consultant rheumatologist and honorary professor of rheumatology at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham, England, noted that there was some indication of an effect of rituximab on fatigue and oral dryness in another large, randomized, controlled trial – the Tolerance and Efficacy of Rituximab in Sjögren’s syndrome (TEARS) study – a couple of years ago (Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72[6]:1026-31), but these were not the primary endpoints of the study, so those results were essentially negative.

Calling the TRACTISS findings something of disappointment, Dr. Bowman said: “I think we’ll have to wait and see, but having had two big formal trials, I have to say that it doesn’t look like rituximab on its own is going to be any [great] success.”

Hopes were high for rituximab 5 years ago, when recruitment into the TRACTISS trial started, principally because drugs like rituximab already were available for use, Dr. Bowman said at the time. The focus was on anti–B cell therapies, because not only were they available but several features of Sjögren’s syndrome potentially are linked to B-cell activity, such as fatigue in about two-thirds of patients, the presence of anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies in about 40% of patients, and lymphoma in about 5% of patients. Also, several small studies had suggested rituximab might prove beneficial.

Other B-cell therapeutic options

Clearly, other B-cell targets might offer alternative therapeutic approaches. One of those under investigation is using belimumab (Benlysta) to target B cell–activating factor (BAFF) or B-cell lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS). Results of the BELISS study, a small, open-label, phase II trial in 30 patients with Sjögren’s syndrome (Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74[3]:526-31) showed there were some improvements in the ESSDAI and the EULAR Sjögren’s Syndrome Patient-Reported Index (ESSPRI). The improvements were great enough to justify proceeding to a larger clinical trial.

Perhaps the real hope for biologic therapy lies in targeting the T cells for which there is a very good rationale, said Wan-Fai Ng, Ph.D., professor of rheumatology at Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, England. Various approaches are available, and in addition, there have been some “encouraging” data from early-phase clinical trials.

Abatacept (Orencia), for example, has been looked at in a few trials, with positive drops in ESSDAI and other endpoints, and currently, there is an ongoing phase III trial in 88 patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. There are a couple of ongoing phase II trials, one with the anti-CD40 molecule CFZ533 and another with the anti-B7RP1 molecule AMG 557.

Dr. Ng noted that a trial of efalizumab (Raptiva) had terminated because of an increased risk for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. In addition, a couple of other molecules, rhIL-2 and alefacept (Amevive), are under investigation, he said.

Four additional therapeutic targets

Other novel approaches to developing biologic therapy for Sjögren’s were summarized by Dr. Francesca Barone, a senior lecturer at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham, England. She described four strategies, the first of which was targeting the cross talk between antigen-presenting dendritic cells and T cells using a novel molecule RO5459072 that targets a protein called cathepsin S. Cathepsin S is involved in the assembly of the major histocompatibility complex II protein, and by interfering with this process, the theory is that the effector T-helper cell response will be muted and T-cell interaction with B cells will be decreased. A phase II “proof-of-concept” trial is underway with RO5459072 and will recruit 70 patients, she said.

A second strategy is targeting intracellular B cell signaling by targeting P13 kinase delta with UCB 5857. P13 kinase delta catalyzes B cell activation and “is really at the core of the biology of the B cell,” Dr. Barone observed. A phase II trial with UCB 5857 is planned in 52 patients.

A third approach is to target lymphoneogenesis more generally by interfering with the production of the chemokines CXCL13 and CXCL12. This might be achieved via interleukin (IL)–17 and IL-22 blockade. A trial with the novel agent baminercept, a lymphotoxin beta receptor fusion protein. However, that trial was stopped in 2014 for technical reasons.

A fourth strategy is to use combination “sandwich” treatment, consisting of belimumab, rituximab, and then belimumab again. “This is what is going to come next, putting two drugs together,” Dr. Barone said. A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial now open to recruitment aims to investigate whether there is value in this approach.

“We’ve bombarded you with a lot of targets,” Dr. Barone observed. “What do we believe is going to be the best one is very, very unclear.”

TRACTISS was funded by Arthritis Research UK with rituximab provided by Roche. Dr. Bowman did not provide any disclosures but previously has been a consultant for Roche, UCB Pharma, and Merck-Serono. Dr. Ng reported no conflicts of interest, and Dr. Barone disclosed consultancy or collaboration with UCB Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline, Celgene, Eli Lilly, and Roche.

GLASGOW – Rituximab is unlikely to work as a treatment for Sjögren’s syndrome, according to a sneak peak of results from a multicenter study.

The study, the Trial of Anti–B Cell Therapy in Patients With Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome (TRACTISS), showed that there were no significant differences between the active and placebo arms in terms of alleviating oral dryness or fatigue, Dr. Simon J. Bowman, a principal investigator for the trial, observed at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference. In addition, no difference was found in the EULAR Sjögren’s syndrome disease activity index (ESSDAI).

In TRACTISS, 110 patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome received two courses of rituximab (Rituxan) or placebo in addition to standard therapy, and they were followed up for up to 48 weeks (BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:21).

Dr. Bowman, a consultant rheumatologist and honorary professor of rheumatology at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham, England, noted that there was some indication of an effect of rituximab on fatigue and oral dryness in another large, randomized, controlled trial – the Tolerance and Efficacy of Rituximab in Sjögren’s syndrome (TEARS) study – a couple of years ago (Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72[6]:1026-31), but these were not the primary endpoints of the study, so those results were essentially negative.

Calling the TRACTISS findings something of disappointment, Dr. Bowman said: “I think we’ll have to wait and see, but having had two big formal trials, I have to say that it doesn’t look like rituximab on its own is going to be any [great] success.”

Hopes were high for rituximab 5 years ago, when recruitment into the TRACTISS trial started, principally because drugs like rituximab already were available for use, Dr. Bowman said at the time. The focus was on anti–B cell therapies, because not only were they available but several features of Sjögren’s syndrome potentially are linked to B-cell activity, such as fatigue in about two-thirds of patients, the presence of anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies in about 40% of patients, and lymphoma in about 5% of patients. Also, several small studies had suggested rituximab might prove beneficial.

Other B-cell therapeutic options

Clearly, other B-cell targets might offer alternative therapeutic approaches. One of those under investigation is using belimumab (Benlysta) to target B cell–activating factor (BAFF) or B-cell lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS). Results of the BELISS study, a small, open-label, phase II trial in 30 patients with Sjögren’s syndrome (Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74[3]:526-31) showed there were some improvements in the ESSDAI and the EULAR Sjögren’s Syndrome Patient-Reported Index (ESSPRI). The improvements were great enough to justify proceeding to a larger clinical trial.

Perhaps the real hope for biologic therapy lies in targeting the T cells for which there is a very good rationale, said Wan-Fai Ng, Ph.D., professor of rheumatology at Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, England. Various approaches are available, and in addition, there have been some “encouraging” data from early-phase clinical trials.

Abatacept (Orencia), for example, has been looked at in a few trials, with positive drops in ESSDAI and other endpoints, and currently, there is an ongoing phase III trial in 88 patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. There are a couple of ongoing phase II trials, one with the anti-CD40 molecule CFZ533 and another with the anti-B7RP1 molecule AMG 557.

Dr. Ng noted that a trial of efalizumab (Raptiva) had terminated because of an increased risk for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. In addition, a couple of other molecules, rhIL-2 and alefacept (Amevive), are under investigation, he said.

Four additional therapeutic targets

Other novel approaches to developing biologic therapy for Sjögren’s were summarized by Dr. Francesca Barone, a senior lecturer at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham, England. She described four strategies, the first of which was targeting the cross talk between antigen-presenting dendritic cells and T cells using a novel molecule RO5459072 that targets a protein called cathepsin S. Cathepsin S is involved in the assembly of the major histocompatibility complex II protein, and by interfering with this process, the theory is that the effector T-helper cell response will be muted and T-cell interaction with B cells will be decreased. A phase II “proof-of-concept” trial is underway with RO5459072 and will recruit 70 patients, she said.

A second strategy is targeting intracellular B cell signaling by targeting P13 kinase delta with UCB 5857. P13 kinase delta catalyzes B cell activation and “is really at the core of the biology of the B cell,” Dr. Barone observed. A phase II trial with UCB 5857 is planned in 52 patients.

A third approach is to target lymphoneogenesis more generally by interfering with the production of the chemokines CXCL13 and CXCL12. This might be achieved via interleukin (IL)–17 and IL-22 blockade. A trial with the novel agent baminercept, a lymphotoxin beta receptor fusion protein. However, that trial was stopped in 2014 for technical reasons.

A fourth strategy is to use combination “sandwich” treatment, consisting of belimumab, rituximab, and then belimumab again. “This is what is going to come next, putting two drugs together,” Dr. Barone said. A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial now open to recruitment aims to investigate whether there is value in this approach.

“We’ve bombarded you with a lot of targets,” Dr. Barone observed. “What do we believe is going to be the best one is very, very unclear.”

TRACTISS was funded by Arthritis Research UK with rituximab provided by Roche. Dr. Bowman did not provide any disclosures but previously has been a consultant for Roche, UCB Pharma, and Merck-Serono. Dr. Ng reported no conflicts of interest, and Dr. Barone disclosed consultancy or collaboration with UCB Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline, Celgene, Eli Lilly, and Roche.

AT RHEUMATOLOGY 2016

Key clinical point: Randomized clinical trial data suggest rituximab is unlikely to have any benefit in treating patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome.

Major finding: There were no significant differences in the study endpoints of sicca syndrome, fatigue, or systemic disease.

Data source: TRACTISS, a U.K. multicenter, double-blind, randomized, controlled, parallel-group trial of rituximab vs. placebo in 110 patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome.

Disclosures: TRACTISS was funded by Arthritis Research UK, with rituximab provided by Roche. Dr. Bowman did not provide any disclosures but previously has been a consultant for Roche, UCB Pharma, and Merck-Serono. Dr. Ng reported no conflicts of interest, and Dr. Barone disclosed consultancy or collaboration with UCB Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline, Celgene, Eli Lilly, and Roche.

Simple Signs Could Signal Complex Pain Syndrome

GLASGOW – Two novel clinical signs can be used to determine whether people who have had a fracture are likely to develop complex regional pain syndrome, a condition for which there is currently no specific diagnostic test.

The way in which patients perceived which of their fingers was being touched when their eyes were closed (finger perception) and the position of different parts of their body in relation to one another generally (body scheme) were found to be reliable ways of identifying those who would experience prolonged pain in the future. The positive and negative predictive values of using those tests together were a respective 84.1% and 76.9%.

“Digit misperception and body scheme combined can be useful in predicting chronic pain,” Dr. Nicholas Shenker of Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, England, said in an interview at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

“This may allow a reduction in chronic pain by identifying a cohort requiring more intensive intervention with physiotherapy and intervention,” he added. It also may help to reduce the incidence of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) after sustaining a fracture.

CPRS is characterized by prolonged, intractable pain that often follows injury to a limb, such as a fracture or another traumatic event. “It’s a nervy type pain, burning, and shooting, and it’s a horrible condition,” Dr. Shenker explained. “If you ask patients to rate the amount of pain they get from their condition, whether it is rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, or osteoarthritis, this is the condition that commonly comes top.”

With differential diagnoses spanning many rheumatologic and neurologic conditions, it is perhaps no surprise that patients with CRPS often go undiagnosed for many months. In fact, according to CRPS Registry UK findings, it can take up to 6 months after symptoms start before patients are diagnosed with the pain syndrome (Br J Pain. 2015;9[2]:122-8).

While pain symptoms may resolve by themselves in about one-third of patients by 3 months and three-quarters of patients by 12 months, there are a significant number of patients whose symptoms do not resolve, and their window of opportunity for treatment may have closed. Although treatment may be largely reassurance based for many, some patients may benefit from early physical therapy or pain medication.

“Once you have any chronic pain condition for more than 12 months, the chances of it getting better are pretty slim. So we want to identify these people early, but that is not easy,” Dr. Shenker observed.

Since there is currently no diagnostic test, Dr. Shenker and his associates identified four novel clinical signs – abnormal finger perception, hand laterality identification, body scheme report, and astereognosis – from a cohort of patients with CRPS and developed tests for them.

Finger perception was assessed by asking the subjects to place their hands on their laps, close their eyes and say which finger or thumb was being touched within a 20-second time limit. A positive test was a score of 8 or less out of 10.

Hand laterality was tested using a computer program showing the subjects a series of images of left and right hands and asking them to click whether the image was of a person’s right or left hand. A positive test was a score of fewer than 50 out of 56 or if the subject took longer than 3 minutes to complete the exercise.

Astereognosis, the inability to identify an object by the touch of the hands only, was assessed by asking the subjects to close their eyes and present their hand palms upward, then placing three different objects into it and asking them what they were touching. A test was considered positive if only two out of three objects were recognized, or if the subjects took longer than 6 seconds to identify the objects.

Finally, body scheme is about assessing how patients generally sense the parts of their bodies with their eyes closed, or how one side of the body compares in terms of size, weight, and length to the other. For this test, the body is divided into 17 areas, and over the course of 2 minutes, patients are asked to describe, without moving, how their left side compares to their right side. A test is considered positive if patients’ responses differ by more than 10% in two contiguous areas, such as the arm and elbow.

Only finger perception and body scheme were found to have good positive and negative predictive values individually.

The aim of the prospective observational cohort study Dr. Shenkar presented at the meeting on behalf of colleague Dr. Anoop Kuttikat was to look at those signs to see how common those scenarios were and to determine if these could be used as simple bedside tests to identify those likely to develop CRPS.

Dr. Shenkar reported data on 47 patients aged a mean of 53 years who needed a plaster cast for an upper (wrist) or lower (ankle/tibia) limb fracture who were assessed fewer than 2 weeks after their injury and followed up for 6 months. Their medical records were reviewed 3 years later to see whether chronic pain was present.

One patient developed CRPS. This patient had both a positive finger perception and body scheme test at the baseline assessment. Three patients had persistent pain, and two of those had positive finger perception and body scheme tests. The remaining 43 patients did not have persistent pain, and four of these patients had positive finger perception and body scheme tests. This means that 7 out of the 47 patients would be flagged very early on for further assessment and possible treatment, Dr. Shenker observed.

Future plans are to refine a quicker test for body scheme assessment and to perform a larger prospective multicenter study.

Dr. Shenker has received grant or research support from the British Medical Association, the U.K. National Institute for Health Research’s Clinical Research Network, and the Cambridge Arthritis Research Endeavour.

GLASGOW – Two novel clinical signs can be used to determine whether people who have had a fracture are likely to develop complex regional pain syndrome, a condition for which there is currently no specific diagnostic test.

The way in which patients perceived which of their fingers was being touched when their eyes were closed (finger perception) and the position of different parts of their body in relation to one another generally (body scheme) were found to be reliable ways of identifying those who would experience prolonged pain in the future. The positive and negative predictive values of using those tests together were a respective 84.1% and 76.9%.

“Digit misperception and body scheme combined can be useful in predicting chronic pain,” Dr. Nicholas Shenker of Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, England, said in an interview at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

“This may allow a reduction in chronic pain by identifying a cohort requiring more intensive intervention with physiotherapy and intervention,” he added. It also may help to reduce the incidence of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) after sustaining a fracture.

CPRS is characterized by prolonged, intractable pain that often follows injury to a limb, such as a fracture or another traumatic event. “It’s a nervy type pain, burning, and shooting, and it’s a horrible condition,” Dr. Shenker explained. “If you ask patients to rate the amount of pain they get from their condition, whether it is rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, or osteoarthritis, this is the condition that commonly comes top.”

With differential diagnoses spanning many rheumatologic and neurologic conditions, it is perhaps no surprise that patients with CRPS often go undiagnosed for many months. In fact, according to CRPS Registry UK findings, it can take up to 6 months after symptoms start before patients are diagnosed with the pain syndrome (Br J Pain. 2015;9[2]:122-8).

While pain symptoms may resolve by themselves in about one-third of patients by 3 months and three-quarters of patients by 12 months, there are a significant number of patients whose symptoms do not resolve, and their window of opportunity for treatment may have closed. Although treatment may be largely reassurance based for many, some patients may benefit from early physical therapy or pain medication.

“Once you have any chronic pain condition for more than 12 months, the chances of it getting better are pretty slim. So we want to identify these people early, but that is not easy,” Dr. Shenker observed.

Since there is currently no diagnostic test, Dr. Shenker and his associates identified four novel clinical signs – abnormal finger perception, hand laterality identification, body scheme report, and astereognosis – from a cohort of patients with CRPS and developed tests for them.

Finger perception was assessed by asking the subjects to place their hands on their laps, close their eyes and say which finger or thumb was being touched within a 20-second time limit. A positive test was a score of 8 or less out of 10.

Hand laterality was tested using a computer program showing the subjects a series of images of left and right hands and asking them to click whether the image was of a person’s right or left hand. A positive test was a score of fewer than 50 out of 56 or if the subject took longer than 3 minutes to complete the exercise.

Astereognosis, the inability to identify an object by the touch of the hands only, was assessed by asking the subjects to close their eyes and present their hand palms upward, then placing three different objects into it and asking them what they were touching. A test was considered positive if only two out of three objects were recognized, or if the subjects took longer than 6 seconds to identify the objects.

Finally, body scheme is about assessing how patients generally sense the parts of their bodies with their eyes closed, or how one side of the body compares in terms of size, weight, and length to the other. For this test, the body is divided into 17 areas, and over the course of 2 minutes, patients are asked to describe, without moving, how their left side compares to their right side. A test is considered positive if patients’ responses differ by more than 10% in two contiguous areas, such as the arm and elbow.

Only finger perception and body scheme were found to have good positive and negative predictive values individually.

The aim of the prospective observational cohort study Dr. Shenkar presented at the meeting on behalf of colleague Dr. Anoop Kuttikat was to look at those signs to see how common those scenarios were and to determine if these could be used as simple bedside tests to identify those likely to develop CRPS.

Dr. Shenkar reported data on 47 patients aged a mean of 53 years who needed a plaster cast for an upper (wrist) or lower (ankle/tibia) limb fracture who were assessed fewer than 2 weeks after their injury and followed up for 6 months. Their medical records were reviewed 3 years later to see whether chronic pain was present.

One patient developed CRPS. This patient had both a positive finger perception and body scheme test at the baseline assessment. Three patients had persistent pain, and two of those had positive finger perception and body scheme tests. The remaining 43 patients did not have persistent pain, and four of these patients had positive finger perception and body scheme tests. This means that 7 out of the 47 patients would be flagged very early on for further assessment and possible treatment, Dr. Shenker observed.

Future plans are to refine a quicker test for body scheme assessment and to perform a larger prospective multicenter study.

Dr. Shenker has received grant or research support from the British Medical Association, the U.K. National Institute for Health Research’s Clinical Research Network, and the Cambridge Arthritis Research Endeavour.

GLASGOW – Two novel clinical signs can be used to determine whether people who have had a fracture are likely to develop complex regional pain syndrome, a condition for which there is currently no specific diagnostic test.

The way in which patients perceived which of their fingers was being touched when their eyes were closed (finger perception) and the position of different parts of their body in relation to one another generally (body scheme) were found to be reliable ways of identifying those who would experience prolonged pain in the future. The positive and negative predictive values of using those tests together were a respective 84.1% and 76.9%.

“Digit misperception and body scheme combined can be useful in predicting chronic pain,” Dr. Nicholas Shenker of Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, England, said in an interview at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

“This may allow a reduction in chronic pain by identifying a cohort requiring more intensive intervention with physiotherapy and intervention,” he added. It also may help to reduce the incidence of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) after sustaining a fracture.

CPRS is characterized by prolonged, intractable pain that often follows injury to a limb, such as a fracture or another traumatic event. “It’s a nervy type pain, burning, and shooting, and it’s a horrible condition,” Dr. Shenker explained. “If you ask patients to rate the amount of pain they get from their condition, whether it is rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, or osteoarthritis, this is the condition that commonly comes top.”

With differential diagnoses spanning many rheumatologic and neurologic conditions, it is perhaps no surprise that patients with CRPS often go undiagnosed for many months. In fact, according to CRPS Registry UK findings, it can take up to 6 months after symptoms start before patients are diagnosed with the pain syndrome (Br J Pain. 2015;9[2]:122-8).

While pain symptoms may resolve by themselves in about one-third of patients by 3 months and three-quarters of patients by 12 months, there are a significant number of patients whose symptoms do not resolve, and their window of opportunity for treatment may have closed. Although treatment may be largely reassurance based for many, some patients may benefit from early physical therapy or pain medication.

“Once you have any chronic pain condition for more than 12 months, the chances of it getting better are pretty slim. So we want to identify these people early, but that is not easy,” Dr. Shenker observed.

Since there is currently no diagnostic test, Dr. Shenker and his associates identified four novel clinical signs – abnormal finger perception, hand laterality identification, body scheme report, and astereognosis – from a cohort of patients with CRPS and developed tests for them.

Finger perception was assessed by asking the subjects to place their hands on their laps, close their eyes and say which finger or thumb was being touched within a 20-second time limit. A positive test was a score of 8 or less out of 10.

Hand laterality was tested using a computer program showing the subjects a series of images of left and right hands and asking them to click whether the image was of a person’s right or left hand. A positive test was a score of fewer than 50 out of 56 or if the subject took longer than 3 minutes to complete the exercise.

Astereognosis, the inability to identify an object by the touch of the hands only, was assessed by asking the subjects to close their eyes and present their hand palms upward, then placing three different objects into it and asking them what they were touching. A test was considered positive if only two out of three objects were recognized, or if the subjects took longer than 6 seconds to identify the objects.

Finally, body scheme is about assessing how patients generally sense the parts of their bodies with their eyes closed, or how one side of the body compares in terms of size, weight, and length to the other. For this test, the body is divided into 17 areas, and over the course of 2 minutes, patients are asked to describe, without moving, how their left side compares to their right side. A test is considered positive if patients’ responses differ by more than 10% in two contiguous areas, such as the arm and elbow.

Only finger perception and body scheme were found to have good positive and negative predictive values individually.

The aim of the prospective observational cohort study Dr. Shenkar presented at the meeting on behalf of colleague Dr. Anoop Kuttikat was to look at those signs to see how common those scenarios were and to determine if these could be used as simple bedside tests to identify those likely to develop CRPS.

Dr. Shenkar reported data on 47 patients aged a mean of 53 years who needed a plaster cast for an upper (wrist) or lower (ankle/tibia) limb fracture who were assessed fewer than 2 weeks after their injury and followed up for 6 months. Their medical records were reviewed 3 years later to see whether chronic pain was present.

One patient developed CRPS. This patient had both a positive finger perception and body scheme test at the baseline assessment. Three patients had persistent pain, and two of those had positive finger perception and body scheme tests. The remaining 43 patients did not have persistent pain, and four of these patients had positive finger perception and body scheme tests. This means that 7 out of the 47 patients would be flagged very early on for further assessment and possible treatment, Dr. Shenker observed.

Future plans are to refine a quicker test for body scheme assessment and to perform a larger prospective multicenter study.

Dr. Shenker has received grant or research support from the British Medical Association, the U.K. National Institute for Health Research’s Clinical Research Network, and the Cambridge Arthritis Research Endeavour.

AT RHEUMATOLOGY 2016

Simple signs could signal complex pain syndrome

GLASGOW – Two novel clinical signs can be used to determine whether people who have had a fracture are likely to develop complex regional pain syndrome, a condition for which there is currently no specific diagnostic test.

The way in which patients perceived which of their fingers was being touched when their eyes were closed (finger perception) and the position of different parts of their body in relation to one another generally (body scheme) were found to be reliable ways of identifying those who would experience prolonged pain in the future. The positive and negative predictive values of using those tests together were a respective 84.1% and 76.9%.

“Digit misperception and body scheme combined can be useful in predicting chronic pain,” Dr. Nicholas Shenker of Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, England, said in an interview at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

“This may allow a reduction in chronic pain by identifying a cohort requiring more intensive intervention with physiotherapy and intervention,” he added. It also may help to reduce the incidence of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) after sustaining a fracture.

CPRS is characterized by prolonged, intractable pain that often follows injury to a limb, such as a fracture or another traumatic event. “It’s a nervy type pain, burning, and shooting, and it’s a horrible condition,” Dr. Shenker explained. “If you ask patients to rate the amount of pain they get from their condition, whether it is rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, or osteoarthritis, this is the condition that commonly comes top.”

With differential diagnoses spanning many rheumatologic and neurologic conditions, it is perhaps no surprise that patients with CRPS often go undiagnosed for many months. In fact, according to CRPS Registry UK findings, it can take up to 6 months after symptoms start before patients are diagnosed with the pain syndrome (Br J Pain. 2015;9[2]:122-8).

While pain symptoms may resolve by themselves in about one-third of patients by 3 months and three-quarters of patients by 12 months, there are a significant number of patients whose symptoms do not resolve, and their window of opportunity for treatment may have closed. Although treatment may be largely reassurance based for many, some patients may benefit from early physical therapy or pain medication.

“Once you have any chronic pain condition for more than 12 months, the chances of it getting better are pretty slim. So we want to identify these people early, but that is not easy,” Dr. Shenker observed.

Since there is currently no diagnostic test, Dr. Shenker and his associates identified four novel clinical signs – abnormal finger perception, hand laterality identification, body scheme report, and astereognosis – from a cohort of patients with CRPS and developed tests for them.

Finger perception was assessed by asking the subjects to place their hands on their laps, close their eyes and say which finger or thumb was being touched within a 20-second time limit. A positive test was a score of 8 or less out of 10.

Hand laterality was tested using a computer program showing the subjects a series of images of left and right hands and asking them to click whether the image was of a person’s right or left hand. A positive test was a score of fewer than 50 out of 56 or if the subject took longer than 3 minutes to complete the exercise.

Astereognosis, the inability to identify an object by the touch of the hands only, was assessed by asking the subjects to close their eyes and present their hand palms upward, then placing three different objects into it and asking them what they were touching. A test was considered positive if only two out of three objects were recognized, or if the subjects took longer than 6 seconds to identify the objects.

Finally, body scheme is about assessing how patients generally sense the parts of their bodies with their eyes closed, or how one side of the body compares in terms of size, weight, and length to the other. For this test, the body is divided into 17 areas, and over the course of 2 minutes, patients are asked to describe, without moving, how their left side compares to their right side. A test is considered positive if patients’ responses differ by more than 10% in two contiguous areas, such as the arm and elbow.

Only finger perception and body scheme were found to have good positive and negative predictive values individually.

The aim of the prospective observational cohort study Dr. Shenkar presented at the meeting on behalf of colleague Dr. Anoop Kuttikat was to look at those signs to see how common those scenarios were and to determine if these could be used as simple bedside tests to identify those likely to develop CRPS.

Dr. Shenkar reported data on 47 patients aged a mean of 53 years who needed a plaster cast for an upper (wrist) or lower (ankle/tibia) limb fracture who were assessed fewer than 2 weeks after their injury and followed up for 6 months. Their medical records were reviewed 3 years later to see whether chronic pain was present.

One patient developed CRPS. This patient had both a positive finger perception and body scheme test at the baseline assessment. Three patients had persistent pain, and two of those had positive finger perception and body scheme tests. The remaining 43 patients did not have persistent pain, and four of these patients had positive finger perception and body scheme tests. This means that 7 out of the 47 patients would be flagged very early on for further assessment and possible treatment, Dr. Shenker observed.

Future plans are to refine a quicker test for body scheme assessment and to perform a larger prospective multicenter study.

Dr. Shenker has received grant or research support from the British Medical Association, the U.K. National Institute for Health Research’s Clinical Research Network, and the Cambridge Arthritis Research Endeavour.

GLASGOW – Two novel clinical signs can be used to determine whether people who have had a fracture are likely to develop complex regional pain syndrome, a condition for which there is currently no specific diagnostic test.

The way in which patients perceived which of their fingers was being touched when their eyes were closed (finger perception) and the position of different parts of their body in relation to one another generally (body scheme) were found to be reliable ways of identifying those who would experience prolonged pain in the future. The positive and negative predictive values of using those tests together were a respective 84.1% and 76.9%.

“Digit misperception and body scheme combined can be useful in predicting chronic pain,” Dr. Nicholas Shenker of Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, England, said in an interview at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

“This may allow a reduction in chronic pain by identifying a cohort requiring more intensive intervention with physiotherapy and intervention,” he added. It also may help to reduce the incidence of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) after sustaining a fracture.

CPRS is characterized by prolonged, intractable pain that often follows injury to a limb, such as a fracture or another traumatic event. “It’s a nervy type pain, burning, and shooting, and it’s a horrible condition,” Dr. Shenker explained. “If you ask patients to rate the amount of pain they get from their condition, whether it is rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, or osteoarthritis, this is the condition that commonly comes top.”