User login

European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD): Annual Meeting

EASD: Alirocumab lipid-lowering benefits extend to patients with high-risk diabetes

STOCKHOLM – The lipid-lowering drug alirocumab significantly lowered low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level to a similar extent in people with diabetes mellitus as in those without diabetes, based on a subanalysis of data from the ODYSSEY Long-Term study.

The calculated change in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol from baseline to 24 weeks was –60.1% with alirocumab vs. –0.9% with placebo, for an overall difference of –59.2% in those with diabetes. By comparison, the corresponding mean changes in LDL cholesterol were –61.5% and –1.8% (a difference of –59.7%) in nondiabetic individuals.

Improvements in other parameters – including triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and lipoprotein(a) (Lp[a]) – were also similar in individuals with and without diabetes.

“The ODYSSEY Long-Term study is the longest study in the ODYSSEY phase III program,” said study investigator Dr. Helen Colhoun of the University of Dundee (Scotland). The primary endpoint was assessed at 24 weeks, but the trial ran for a further 54 weeks to gather as much lipid and general safety data as possible, she explained at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Alirocumab (Praulent) is a fully human monoclonal antibody that binds PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9) that was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use as an adjunct to diet and maximally tolerated statin therapy in people with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia or clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease who need additional LDL-cholesterol lowering.

The main results of the ODYSSEY Long-Term study were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in April (2015;372:1489-99 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501031) and showed a –62% difference (P less than .001) in the mean percentage change from baseline in calculated LDL cholesterol between the alirocumab and placebo groups at 24 weeks. The difference remained consistent over the 78 weeks of follow-up.

Overall, the study included 2,341 individuals at high risk for cardiovascular disease with an LDL cholesterol level of more than 70 mg/dL despite being treated with maximally tolerated doses of statins with or without additional lipid-lowering therapy. Of these, just over one third of the population (35.7%, n = 838) had diabetes. Patients in the trial were randomized 2:1 to receive either alirocumab 150 mg or matching placebo as a 1-mL injection once every 2 weeks.

The present analysis looked at the long-term efficacy and safety of alirocumab in the diabetic subpopulation. Baseline demographic and lipid characteristics of the 838 patients with diabetes were broadly similar to the 1,503 patients in the trial who did not have diabetes, with mean ages of 61 and 60 years. Dr. Colhoun pointed out that virtually all patients (999; 100%) were taking a background statin, and well over one-third of those with diabetes and half of those without were taking a high-dose statin. Approximately 26% of the diabetic population were receiving insulin. Diabetic patients had slightly lower LDL cholesterol and higher triglycerides than their nondiabetic counterparts at baseline, as would be expected, she added.

Similarly high proportions of patients with (78.4% vs. 10.6%, P less than .0001) and without (79.7% vs. 6.6%, P less than .0001) diabetes who were treated with alirocumab vs. placebo achieved a target LDL cholesterol level of less than 70 mg/dL at 24 weeks.

Alirocumab treatment was associated with a 3.5% increase in HDL cholesterol in patients with diabetes and a 5.6% increase in those without, and triglycerides were reduced by a respective –18.5% and –16.7%. The adjusted mean differences in Lp(a) were –27.2% and –24.9%, an effect not seen with statins, Dr. Colhoun said.

“Overall the safety profile was excellent with this new class of drug, and there weren’t any major surprises or differences in safety profile between those with diabetes receiving alirocumab and those without diabetes,” she noted. Less than 10% of adverse events led to treatment discontinuation, at 8.3% vs. 5.0% for active and placebo treatment in the diabetic group and 6.5% vs. 6.3% in those without diabetes.

Data on the risk for new-onset or worsening diabetes in the ODYSSEY program will be presented at the scientific sessions of the American Heart Association in November, Dr. Colhoun said, giving a sneak peak of the findings from the ODYSSEY Long-Term study that indicated that there was no increased risk for either. Rates of new-onset diabetes were 1.8% in the alirocumab-treated group and 2% in the placebo group and of worsening diabetes, were 12.9% and 13.6%, respectively.

Treatment-emergent major cardiovascular events (MACE) were evaluated as a safety parameter in a post hoc analysis. Although not a main endpoint of the study, the results showed a lower rate of MACE in the overall population with alirocumab than placebo treatment (1.7% vs. 3.3%; hazard ratio, 0.52; 95% confidence interval, 0.31-0.90) and in both diabetic (2.5% vs. 4.3%; HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.27-1.25) and nondiabetic subjects (1.3% vs. 2.8%; HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.22-1.0). “This is reassuring, but it is not by any means definitive evidence of a [cardiovascular disease] benefit,” Dr. Colhoun stressed.

The potential for alirocumab to reduce cardiovascular events will be investigated in the large, phase III ODYSSEY Outcomes study. This trial is currently recruiting and aims to accrue around 18,000 high-risk patients including those with diabetes. The study is projected to complete by the end of 2017.

STOCKHOLM – The lipid-lowering drug alirocumab significantly lowered low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level to a similar extent in people with diabetes mellitus as in those without diabetes, based on a subanalysis of data from the ODYSSEY Long-Term study.

The calculated change in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol from baseline to 24 weeks was –60.1% with alirocumab vs. –0.9% with placebo, for an overall difference of –59.2% in those with diabetes. By comparison, the corresponding mean changes in LDL cholesterol were –61.5% and –1.8% (a difference of –59.7%) in nondiabetic individuals.

Improvements in other parameters – including triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and lipoprotein(a) (Lp[a]) – were also similar in individuals with and without diabetes.

“The ODYSSEY Long-Term study is the longest study in the ODYSSEY phase III program,” said study investigator Dr. Helen Colhoun of the University of Dundee (Scotland). The primary endpoint was assessed at 24 weeks, but the trial ran for a further 54 weeks to gather as much lipid and general safety data as possible, she explained at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Alirocumab (Praulent) is a fully human monoclonal antibody that binds PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9) that was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use as an adjunct to diet and maximally tolerated statin therapy in people with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia or clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease who need additional LDL-cholesterol lowering.

The main results of the ODYSSEY Long-Term study were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in April (2015;372:1489-99 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501031) and showed a –62% difference (P less than .001) in the mean percentage change from baseline in calculated LDL cholesterol between the alirocumab and placebo groups at 24 weeks. The difference remained consistent over the 78 weeks of follow-up.

Overall, the study included 2,341 individuals at high risk for cardiovascular disease with an LDL cholesterol level of more than 70 mg/dL despite being treated with maximally tolerated doses of statins with or without additional lipid-lowering therapy. Of these, just over one third of the population (35.7%, n = 838) had diabetes. Patients in the trial were randomized 2:1 to receive either alirocumab 150 mg or matching placebo as a 1-mL injection once every 2 weeks.

The present analysis looked at the long-term efficacy and safety of alirocumab in the diabetic subpopulation. Baseline demographic and lipid characteristics of the 838 patients with diabetes were broadly similar to the 1,503 patients in the trial who did not have diabetes, with mean ages of 61 and 60 years. Dr. Colhoun pointed out that virtually all patients (999; 100%) were taking a background statin, and well over one-third of those with diabetes and half of those without were taking a high-dose statin. Approximately 26% of the diabetic population were receiving insulin. Diabetic patients had slightly lower LDL cholesterol and higher triglycerides than their nondiabetic counterparts at baseline, as would be expected, she added.

Similarly high proportions of patients with (78.4% vs. 10.6%, P less than .0001) and without (79.7% vs. 6.6%, P less than .0001) diabetes who were treated with alirocumab vs. placebo achieved a target LDL cholesterol level of less than 70 mg/dL at 24 weeks.

Alirocumab treatment was associated with a 3.5% increase in HDL cholesterol in patients with diabetes and a 5.6% increase in those without, and triglycerides were reduced by a respective –18.5% and –16.7%. The adjusted mean differences in Lp(a) were –27.2% and –24.9%, an effect not seen with statins, Dr. Colhoun said.

“Overall the safety profile was excellent with this new class of drug, and there weren’t any major surprises or differences in safety profile between those with diabetes receiving alirocumab and those without diabetes,” she noted. Less than 10% of adverse events led to treatment discontinuation, at 8.3% vs. 5.0% for active and placebo treatment in the diabetic group and 6.5% vs. 6.3% in those without diabetes.

Data on the risk for new-onset or worsening diabetes in the ODYSSEY program will be presented at the scientific sessions of the American Heart Association in November, Dr. Colhoun said, giving a sneak peak of the findings from the ODYSSEY Long-Term study that indicated that there was no increased risk for either. Rates of new-onset diabetes were 1.8% in the alirocumab-treated group and 2% in the placebo group and of worsening diabetes, were 12.9% and 13.6%, respectively.

Treatment-emergent major cardiovascular events (MACE) were evaluated as a safety parameter in a post hoc analysis. Although not a main endpoint of the study, the results showed a lower rate of MACE in the overall population with alirocumab than placebo treatment (1.7% vs. 3.3%; hazard ratio, 0.52; 95% confidence interval, 0.31-0.90) and in both diabetic (2.5% vs. 4.3%; HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.27-1.25) and nondiabetic subjects (1.3% vs. 2.8%; HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.22-1.0). “This is reassuring, but it is not by any means definitive evidence of a [cardiovascular disease] benefit,” Dr. Colhoun stressed.

The potential for alirocumab to reduce cardiovascular events will be investigated in the large, phase III ODYSSEY Outcomes study. This trial is currently recruiting and aims to accrue around 18,000 high-risk patients including those with diabetes. The study is projected to complete by the end of 2017.

STOCKHOLM – The lipid-lowering drug alirocumab significantly lowered low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level to a similar extent in people with diabetes mellitus as in those without diabetes, based on a subanalysis of data from the ODYSSEY Long-Term study.

The calculated change in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol from baseline to 24 weeks was –60.1% with alirocumab vs. –0.9% with placebo, for an overall difference of –59.2% in those with diabetes. By comparison, the corresponding mean changes in LDL cholesterol were –61.5% and –1.8% (a difference of –59.7%) in nondiabetic individuals.

Improvements in other parameters – including triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and lipoprotein(a) (Lp[a]) – were also similar in individuals with and without diabetes.

“The ODYSSEY Long-Term study is the longest study in the ODYSSEY phase III program,” said study investigator Dr. Helen Colhoun of the University of Dundee (Scotland). The primary endpoint was assessed at 24 weeks, but the trial ran for a further 54 weeks to gather as much lipid and general safety data as possible, she explained at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Alirocumab (Praulent) is a fully human monoclonal antibody that binds PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9) that was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use as an adjunct to diet and maximally tolerated statin therapy in people with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia or clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease who need additional LDL-cholesterol lowering.

The main results of the ODYSSEY Long-Term study were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in April (2015;372:1489-99 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501031) and showed a –62% difference (P less than .001) in the mean percentage change from baseline in calculated LDL cholesterol between the alirocumab and placebo groups at 24 weeks. The difference remained consistent over the 78 weeks of follow-up.

Overall, the study included 2,341 individuals at high risk for cardiovascular disease with an LDL cholesterol level of more than 70 mg/dL despite being treated with maximally tolerated doses of statins with or without additional lipid-lowering therapy. Of these, just over one third of the population (35.7%, n = 838) had diabetes. Patients in the trial were randomized 2:1 to receive either alirocumab 150 mg or matching placebo as a 1-mL injection once every 2 weeks.

The present analysis looked at the long-term efficacy and safety of alirocumab in the diabetic subpopulation. Baseline demographic and lipid characteristics of the 838 patients with diabetes were broadly similar to the 1,503 patients in the trial who did not have diabetes, with mean ages of 61 and 60 years. Dr. Colhoun pointed out that virtually all patients (999; 100%) were taking a background statin, and well over one-third of those with diabetes and half of those without were taking a high-dose statin. Approximately 26% of the diabetic population were receiving insulin. Diabetic patients had slightly lower LDL cholesterol and higher triglycerides than their nondiabetic counterparts at baseline, as would be expected, she added.

Similarly high proportions of patients with (78.4% vs. 10.6%, P less than .0001) and without (79.7% vs. 6.6%, P less than .0001) diabetes who were treated with alirocumab vs. placebo achieved a target LDL cholesterol level of less than 70 mg/dL at 24 weeks.

Alirocumab treatment was associated with a 3.5% increase in HDL cholesterol in patients with diabetes and a 5.6% increase in those without, and triglycerides were reduced by a respective –18.5% and –16.7%. The adjusted mean differences in Lp(a) were –27.2% and –24.9%, an effect not seen with statins, Dr. Colhoun said.

“Overall the safety profile was excellent with this new class of drug, and there weren’t any major surprises or differences in safety profile between those with diabetes receiving alirocumab and those without diabetes,” she noted. Less than 10% of adverse events led to treatment discontinuation, at 8.3% vs. 5.0% for active and placebo treatment in the diabetic group and 6.5% vs. 6.3% in those without diabetes.

Data on the risk for new-onset or worsening diabetes in the ODYSSEY program will be presented at the scientific sessions of the American Heart Association in November, Dr. Colhoun said, giving a sneak peak of the findings from the ODYSSEY Long-Term study that indicated that there was no increased risk for either. Rates of new-onset diabetes were 1.8% in the alirocumab-treated group and 2% in the placebo group and of worsening diabetes, were 12.9% and 13.6%, respectively.

Treatment-emergent major cardiovascular events (MACE) were evaluated as a safety parameter in a post hoc analysis. Although not a main endpoint of the study, the results showed a lower rate of MACE in the overall population with alirocumab than placebo treatment (1.7% vs. 3.3%; hazard ratio, 0.52; 95% confidence interval, 0.31-0.90) and in both diabetic (2.5% vs. 4.3%; HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.27-1.25) and nondiabetic subjects (1.3% vs. 2.8%; HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.22-1.0). “This is reassuring, but it is not by any means definitive evidence of a [cardiovascular disease] benefit,” Dr. Colhoun stressed.

The potential for alirocumab to reduce cardiovascular events will be investigated in the large, phase III ODYSSEY Outcomes study. This trial is currently recruiting and aims to accrue around 18,000 high-risk patients including those with diabetes. The study is projected to complete by the end of 2017.

AT EASD 2015

Key clinical point: The benefits of alirocumab seen in the main study population extend to people with diabetes, with no risk for new onset or worsening of diabetes.

Major finding: Mean placebo-corrected reductions in LDL cholesterol level at 24 weeks were –59.2% in people with and –63.3% in people without diabetes (P = .1155).

Data source: A randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study of alirocumab or placebo added to existing lipid-lowering treatment in 2,341 individuals at high cardiovascular risk and hyperlipidemia despite receiving statin therapy, including 838 with diabetes.

Disclosures: Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals funded the study. Dr. Colhoun disclosed acting as an advisory panel member for both companies as well as several other companies including Roche, of which she was also a stockholder or shareholder.

EASD: Diabetes doubles death risk from many causes

STOCKHOLM – Having diabetes doubles the risk for death from a multitude of causes and shortens the life span by 5-7 years, judging from evidence from the United Kingdom Prospective Studies Collaboration presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Patients with diabetes were two and a half times more likely than those without it to die from ischemic heart disease (odds ratio, 2.37; 95% confidence interval, 2.23-2.52). They were also more likely to die from ischemic stroke (OR, 2.75; 95% CI, 2.29-3.31) and “a surprising association with” cardiac arrhythmia (OR, 2.47; 95% CI, 1.80-3.38) was found, said the presenting author, Dr. Louisa Gnatiuc of the clinical trial service unit and epidemiological studies unit at Oxford (England) University. She noted, however, that diabetes was more weakly associated with death from nonischemic causes (OR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.34-1.85).

In addition, diabetic individuals were almost twice as likely as those with no diabetes to die from renal (OR, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.40-2.58) or hepatic (OR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.36-2.26) causes, and there was a 13% increase in the overall risk for death from cancer (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.06-1.21). The small increased risk for cancer death was largely due to deaths from oral (OR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.17-2.81), liver (OR, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.26-2.58), and pancreatic (OR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.21-2.03) cancers, Dr. Gnatiuc observed. Diabetic individuals were also more likely to die from respiratory causes than their nondiabetic counterparts (OR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.37-1.83).

These data provide further insight into the risk for death from a multitude of causes in patients with diabetes, said Dr. Naveed Sattar, who was not involved in the analysis, in an interview. “While it is pretty much a replication of the Emerging Risk Factor Paper that was published in the New England Journal of Medicine, there is a little bit of new information here, such as the relative risks in women versus men and by age as well,” he observed.

The odds ratio for death from ischemic heart disease was higher among women aged 35-39 years with diabetes versus those with no diabetes than in men aged 35-39 years with diabetes versus no diabetes, at 5.61 (95% CI, 4.08-7.72) and 2.49 (95% CI, 2.16-2.85), respectively. Similar finding were seen at other age ranges, with around a twofold increase in men aged 60-69 years (OR, 2.26; 95% CI, 2.01-2.53) and 70-89 years (OR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.70-2.11), but a two- to fourfold increase in women aged 60-69 years (OR, 4.15; 95% CI, 3.38-5.10) and 70-79 years (OR, 2.45, 95% CI, 2.11-2.84).

“So it looks like if you develop diabetes younger, your risk for mortality’s higher,” said Dr. Sattar, professor of metabolic medicine at the Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences, University of Glasgow (Scotland). “That makes sense,” he added, “because if you develop type 2 diabetes at the age of 30, it must be a much more malignant type of diabetes than, say, if you developed diabetes at age 80, and there are other data that now confirm that is the case as well.”

The analysis was based on data from 44 prospective studies that recorded 55,855 deaths in 690,700 adults who had no prior vascular or other chronic diseases at baseline. Men accounted for 60% of the study population, with a mean age of 48 years. During the postpresentation discussion, Dr. Gnatiuc noted that it was difficult to standardize the definition of diabetes used in the study and that all 25,000 cases of diabetes included in the study had been self-reported. It is likely that most cases were type 2. No information on the duration of diabetes was available, but she noted that this should not matter given the prospective nature of the analysis.

During 13 million patient-years of follow up the most common cause of death was ischemic heart disease, accounting for 17,218 deaths, followed by cancer (18,658 deaths). There were 5,466 strokes of which 1,353 were ischemic (OR, 2.75; 95% CI 2.29-3.31), 1,124 hemorrhagic (OR, 1.59; 95% CI 1.26-2.01), 2,563 that were unspecified (OR, 2.30; 95% CI 1.99-2.66), and 626 classed as subarachnoid hemorrhage (OR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.36-1.08). Vascular causes of death included inflammatory heart disease, sudden death, and atherosclerosis, among others, which were all increased in diabetic versus nondiabetic subjects.

Dr. Gnatiuc noted that the risk for ischemic heart disease increased with increasing age, systolic blood pressure, and total cholesterol in diabetics and in nondiabetics, although it was much higher in those with diabetes than in those without. “Controlling blood pressure, cholesterol, and obesity are particularly important to reduce absolute mortality rates in those with diabetes, she suggested.

The differences between the sexes in terms of ischemic heart disease need further study, she suggested, noting that improved understanding of the sex differences may help better understand and thus reduce the excess mortality seen.

Premature mortality of up to 5 years in men and 7 years in women was observed. “At the age of 70 a man with diabetes would have about 10% less probability to survive up to the age of 90 as compared to their nondiabetic counterparts,” Dr. Gnatiuc said. Women would have about a 30% decrease in survival probability from age 70-90, she added.

STOCKHOLM – Having diabetes doubles the risk for death from a multitude of causes and shortens the life span by 5-7 years, judging from evidence from the United Kingdom Prospective Studies Collaboration presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Patients with diabetes were two and a half times more likely than those without it to die from ischemic heart disease (odds ratio, 2.37; 95% confidence interval, 2.23-2.52). They were also more likely to die from ischemic stroke (OR, 2.75; 95% CI, 2.29-3.31) and “a surprising association with” cardiac arrhythmia (OR, 2.47; 95% CI, 1.80-3.38) was found, said the presenting author, Dr. Louisa Gnatiuc of the clinical trial service unit and epidemiological studies unit at Oxford (England) University. She noted, however, that diabetes was more weakly associated with death from nonischemic causes (OR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.34-1.85).

In addition, diabetic individuals were almost twice as likely as those with no diabetes to die from renal (OR, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.40-2.58) or hepatic (OR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.36-2.26) causes, and there was a 13% increase in the overall risk for death from cancer (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.06-1.21). The small increased risk for cancer death was largely due to deaths from oral (OR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.17-2.81), liver (OR, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.26-2.58), and pancreatic (OR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.21-2.03) cancers, Dr. Gnatiuc observed. Diabetic individuals were also more likely to die from respiratory causes than their nondiabetic counterparts (OR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.37-1.83).

These data provide further insight into the risk for death from a multitude of causes in patients with diabetes, said Dr. Naveed Sattar, who was not involved in the analysis, in an interview. “While it is pretty much a replication of the Emerging Risk Factor Paper that was published in the New England Journal of Medicine, there is a little bit of new information here, such as the relative risks in women versus men and by age as well,” he observed.

The odds ratio for death from ischemic heart disease was higher among women aged 35-39 years with diabetes versus those with no diabetes than in men aged 35-39 years with diabetes versus no diabetes, at 5.61 (95% CI, 4.08-7.72) and 2.49 (95% CI, 2.16-2.85), respectively. Similar finding were seen at other age ranges, with around a twofold increase in men aged 60-69 years (OR, 2.26; 95% CI, 2.01-2.53) and 70-89 years (OR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.70-2.11), but a two- to fourfold increase in women aged 60-69 years (OR, 4.15; 95% CI, 3.38-5.10) and 70-79 years (OR, 2.45, 95% CI, 2.11-2.84).

“So it looks like if you develop diabetes younger, your risk for mortality’s higher,” said Dr. Sattar, professor of metabolic medicine at the Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences, University of Glasgow (Scotland). “That makes sense,” he added, “because if you develop type 2 diabetes at the age of 30, it must be a much more malignant type of diabetes than, say, if you developed diabetes at age 80, and there are other data that now confirm that is the case as well.”

The analysis was based on data from 44 prospective studies that recorded 55,855 deaths in 690,700 adults who had no prior vascular or other chronic diseases at baseline. Men accounted for 60% of the study population, with a mean age of 48 years. During the postpresentation discussion, Dr. Gnatiuc noted that it was difficult to standardize the definition of diabetes used in the study and that all 25,000 cases of diabetes included in the study had been self-reported. It is likely that most cases were type 2. No information on the duration of diabetes was available, but she noted that this should not matter given the prospective nature of the analysis.

During 13 million patient-years of follow up the most common cause of death was ischemic heart disease, accounting for 17,218 deaths, followed by cancer (18,658 deaths). There were 5,466 strokes of which 1,353 were ischemic (OR, 2.75; 95% CI 2.29-3.31), 1,124 hemorrhagic (OR, 1.59; 95% CI 1.26-2.01), 2,563 that were unspecified (OR, 2.30; 95% CI 1.99-2.66), and 626 classed as subarachnoid hemorrhage (OR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.36-1.08). Vascular causes of death included inflammatory heart disease, sudden death, and atherosclerosis, among others, which were all increased in diabetic versus nondiabetic subjects.

Dr. Gnatiuc noted that the risk for ischemic heart disease increased with increasing age, systolic blood pressure, and total cholesterol in diabetics and in nondiabetics, although it was much higher in those with diabetes than in those without. “Controlling blood pressure, cholesterol, and obesity are particularly important to reduce absolute mortality rates in those with diabetes, she suggested.

The differences between the sexes in terms of ischemic heart disease need further study, she suggested, noting that improved understanding of the sex differences may help better understand and thus reduce the excess mortality seen.

Premature mortality of up to 5 years in men and 7 years in women was observed. “At the age of 70 a man with diabetes would have about 10% less probability to survive up to the age of 90 as compared to their nondiabetic counterparts,” Dr. Gnatiuc said. Women would have about a 30% decrease in survival probability from age 70-90, she added.

STOCKHOLM – Having diabetes doubles the risk for death from a multitude of causes and shortens the life span by 5-7 years, judging from evidence from the United Kingdom Prospective Studies Collaboration presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Patients with diabetes were two and a half times more likely than those without it to die from ischemic heart disease (odds ratio, 2.37; 95% confidence interval, 2.23-2.52). They were also more likely to die from ischemic stroke (OR, 2.75; 95% CI, 2.29-3.31) and “a surprising association with” cardiac arrhythmia (OR, 2.47; 95% CI, 1.80-3.38) was found, said the presenting author, Dr. Louisa Gnatiuc of the clinical trial service unit and epidemiological studies unit at Oxford (England) University. She noted, however, that diabetes was more weakly associated with death from nonischemic causes (OR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.34-1.85).

In addition, diabetic individuals were almost twice as likely as those with no diabetes to die from renal (OR, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.40-2.58) or hepatic (OR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.36-2.26) causes, and there was a 13% increase in the overall risk for death from cancer (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.06-1.21). The small increased risk for cancer death was largely due to deaths from oral (OR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.17-2.81), liver (OR, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.26-2.58), and pancreatic (OR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.21-2.03) cancers, Dr. Gnatiuc observed. Diabetic individuals were also more likely to die from respiratory causes than their nondiabetic counterparts (OR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.37-1.83).

These data provide further insight into the risk for death from a multitude of causes in patients with diabetes, said Dr. Naveed Sattar, who was not involved in the analysis, in an interview. “While it is pretty much a replication of the Emerging Risk Factor Paper that was published in the New England Journal of Medicine, there is a little bit of new information here, such as the relative risks in women versus men and by age as well,” he observed.

The odds ratio for death from ischemic heart disease was higher among women aged 35-39 years with diabetes versus those with no diabetes than in men aged 35-39 years with diabetes versus no diabetes, at 5.61 (95% CI, 4.08-7.72) and 2.49 (95% CI, 2.16-2.85), respectively. Similar finding were seen at other age ranges, with around a twofold increase in men aged 60-69 years (OR, 2.26; 95% CI, 2.01-2.53) and 70-89 years (OR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.70-2.11), but a two- to fourfold increase in women aged 60-69 years (OR, 4.15; 95% CI, 3.38-5.10) and 70-79 years (OR, 2.45, 95% CI, 2.11-2.84).

“So it looks like if you develop diabetes younger, your risk for mortality’s higher,” said Dr. Sattar, professor of metabolic medicine at the Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences, University of Glasgow (Scotland). “That makes sense,” he added, “because if you develop type 2 diabetes at the age of 30, it must be a much more malignant type of diabetes than, say, if you developed diabetes at age 80, and there are other data that now confirm that is the case as well.”

The analysis was based on data from 44 prospective studies that recorded 55,855 deaths in 690,700 adults who had no prior vascular or other chronic diseases at baseline. Men accounted for 60% of the study population, with a mean age of 48 years. During the postpresentation discussion, Dr. Gnatiuc noted that it was difficult to standardize the definition of diabetes used in the study and that all 25,000 cases of diabetes included in the study had been self-reported. It is likely that most cases were type 2. No information on the duration of diabetes was available, but she noted that this should not matter given the prospective nature of the analysis.

During 13 million patient-years of follow up the most common cause of death was ischemic heart disease, accounting for 17,218 deaths, followed by cancer (18,658 deaths). There were 5,466 strokes of which 1,353 were ischemic (OR, 2.75; 95% CI 2.29-3.31), 1,124 hemorrhagic (OR, 1.59; 95% CI 1.26-2.01), 2,563 that were unspecified (OR, 2.30; 95% CI 1.99-2.66), and 626 classed as subarachnoid hemorrhage (OR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.36-1.08). Vascular causes of death included inflammatory heart disease, sudden death, and atherosclerosis, among others, which were all increased in diabetic versus nondiabetic subjects.

Dr. Gnatiuc noted that the risk for ischemic heart disease increased with increasing age, systolic blood pressure, and total cholesterol in diabetics and in nondiabetics, although it was much higher in those with diabetes than in those without. “Controlling blood pressure, cholesterol, and obesity are particularly important to reduce absolute mortality rates in those with diabetes, she suggested.

The differences between the sexes in terms of ischemic heart disease need further study, she suggested, noting that improved understanding of the sex differences may help better understand and thus reduce the excess mortality seen.

Premature mortality of up to 5 years in men and 7 years in women was observed. “At the age of 70 a man with diabetes would have about 10% less probability to survive up to the age of 90 as compared to their nondiabetic counterparts,” Dr. Gnatiuc said. Women would have about a 30% decrease in survival probability from age 70-90, she added.

AT EASD 2015

Key clinical point:Women with diabetes were more likely to die from ischemic heart disease than men with diabetes when compared to those without diabetes.

Major finding: Women with diabetes were more likely to die from ischemic heart disease than men with diabetes when compared to those without diabetes.

Data source: United Kingdom Prospective Studies Collaboration analysis of 44 prospective studies that recorded 55,855 deaths in 690,700 adults who had no prior vascular or other chronic diseases at baseline.

Disclosures: The study was funded by research grants from the British Heart Foundation, UK Medical Research Council, The National Institutes of Health (UK), Cancer Research UK, and the Clinical Trial Service Unit and Epidemiological Studies Unit at Oxford University, UK. Dr. Gnatiuc did not report any personal disclosures.

Metformin-induced B12 Deficiency Linked to Diabetic Neuropathy

STOCKHOLM – Clinicians might want to consider more routinely monitoring levels of vitamin B12 in their diabetic patients who are using metformin, according to new data from the HOME (Hyperinsulinaemia: the Outcome of Its Metabolic Effects) randomized controlled trial, which showed that B12 depletion was linked to neurotoxicity.

The new study findings, presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, showed that metformin increased levels of serum methylmalonic acid (MMA), the gold standard biomarker of tissue B12 deficiency, and that this in turn was linked to neuropathy measured using a validated score.

“We earlier showed that metformin causes B12 deficiency (<150 pmol/L) with a number needed to harm of 14 after 4.3 years,” said study investigator Dr. Mattijs Out of Bethesda Diabetes Research Center in Hoogeveen, the Netherlands, referring to the original results of the trial (BMJ. 2010;340:c2181).

“Today I showed you that metformin increases MMA, dose dependently and progressively over time,” he added. “Metformin has two opposite effects on neuropathy,” he continued, “a neuroprotective effect by improving glycemic control and a neurotoxic effect by inducing B12 depletion.”

Dr. Out noted that metformin remains the cornerstone of type 2 diabetes therapy with over 100 million prescriptions per year, putting many patients at risk for B12 deficiency and its consequences.

Current guidelines from the American Diabetes Association and EASD mention B12 deficiency as a potential downside of metformin use but do not go so far as giving specific recommendations because of lack of evidence on whether screening should be routinely performed or if vitamin B12 supplements should be given.

“Consequences of vitamin B12 deficiency, such as neuropathy or mental changes, may be profound,” Dr. Out said. Changes because of B12 deficits can be difficult to diagnose because they may be ascribed to old age or diabetes itself, and they may become irreversible if unchecked, he observed. Diagnosing and managing B12 deficiency is, in theory, “easy, cheap, and effective,” he said. A new trial would be needed, however, to determine whether screening for B12 deficiency or supplementation would be the better approach.

In the current study, structural equation monitoring (SEM) was used to determine the likely effects of metformin on the Valk neuropathy score (Diabetes Med. 1992;9:716-21) directly and via effects on hemoglobin A1c and MMA. The analysis involved 390 insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes who were also treated with 850 mg metformin or placebo up to three times daily for 52 months. Over a 4.3-year follow-up period, patients had HbA1c and neuropathy scores measured 17 times, and MMA was measured at six visits.

Compared with placebo, metformin use was associated with a significant (P= .001) 0.039 micromol/L (95% confidence interval, 0.019-0.055) increase in MMA over the course of the study.

While there was no significant difference in neuropathy scores between the placebo- and metformin-treated groups, SEM showed that metformin had a beneficial effect on lowering the neuropathy score via lowering HbA1c and an adverse effect on the neuropathy score by increasing MMA levels. Overall, metformin was associated with a 0.25-point increase in the neuropathy score, suggesting the net effect of the oral hypoglycemic drug is a negative one as higher scores mean worse neuropathy.

After the presentation of the findings, session chair Dr. Guntram Schernthaner commented: “In my center in Vienna, we have been using metformin for 30 years, but we have never used this high dosage [850 mg]. We have suspected several times the B12 deficiency and we measured it in many cases, but we never found any cases of severe B12 deficiency.”

Dr. Schernthaner, who is professor of medicine at the University of Vienna in Austria, suggested the next step would be to perform a large trial of maybe 2,000 metformin users to see how often B12 deficiency really occurs.

Dr. Out agreed a larger trial would be the ideal and conceded that the effect size was small. However, with such a large number of patients using the drug worldwide, potentially “many patients are at risk.”

He said a direct effect of metformin on neuropathy would perhaps not be found by general screening because of its protective effect via improved glycemic control, “so you may miss B12 deficiency–induced neuropathy.” Measuring MMA, where possible, may be a solution.

STOCKHOLM – Clinicians might want to consider more routinely monitoring levels of vitamin B12 in their diabetic patients who are using metformin, according to new data from the HOME (Hyperinsulinaemia: the Outcome of Its Metabolic Effects) randomized controlled trial, which showed that B12 depletion was linked to neurotoxicity.

The new study findings, presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, showed that metformin increased levels of serum methylmalonic acid (MMA), the gold standard biomarker of tissue B12 deficiency, and that this in turn was linked to neuropathy measured using a validated score.

“We earlier showed that metformin causes B12 deficiency (<150 pmol/L) with a number needed to harm of 14 after 4.3 years,” said study investigator Dr. Mattijs Out of Bethesda Diabetes Research Center in Hoogeveen, the Netherlands, referring to the original results of the trial (BMJ. 2010;340:c2181).

“Today I showed you that metformin increases MMA, dose dependently and progressively over time,” he added. “Metformin has two opposite effects on neuropathy,” he continued, “a neuroprotective effect by improving glycemic control and a neurotoxic effect by inducing B12 depletion.”

Dr. Out noted that metformin remains the cornerstone of type 2 diabetes therapy with over 100 million prescriptions per year, putting many patients at risk for B12 deficiency and its consequences.

Current guidelines from the American Diabetes Association and EASD mention B12 deficiency as a potential downside of metformin use but do not go so far as giving specific recommendations because of lack of evidence on whether screening should be routinely performed or if vitamin B12 supplements should be given.

“Consequences of vitamin B12 deficiency, such as neuropathy or mental changes, may be profound,” Dr. Out said. Changes because of B12 deficits can be difficult to diagnose because they may be ascribed to old age or diabetes itself, and they may become irreversible if unchecked, he observed. Diagnosing and managing B12 deficiency is, in theory, “easy, cheap, and effective,” he said. A new trial would be needed, however, to determine whether screening for B12 deficiency or supplementation would be the better approach.

In the current study, structural equation monitoring (SEM) was used to determine the likely effects of metformin on the Valk neuropathy score (Diabetes Med. 1992;9:716-21) directly and via effects on hemoglobin A1c and MMA. The analysis involved 390 insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes who were also treated with 850 mg metformin or placebo up to three times daily for 52 months. Over a 4.3-year follow-up period, patients had HbA1c and neuropathy scores measured 17 times, and MMA was measured at six visits.

Compared with placebo, metformin use was associated with a significant (P= .001) 0.039 micromol/L (95% confidence interval, 0.019-0.055) increase in MMA over the course of the study.

While there was no significant difference in neuropathy scores between the placebo- and metformin-treated groups, SEM showed that metformin had a beneficial effect on lowering the neuropathy score via lowering HbA1c and an adverse effect on the neuropathy score by increasing MMA levels. Overall, metformin was associated with a 0.25-point increase in the neuropathy score, suggesting the net effect of the oral hypoglycemic drug is a negative one as higher scores mean worse neuropathy.

After the presentation of the findings, session chair Dr. Guntram Schernthaner commented: “In my center in Vienna, we have been using metformin for 30 years, but we have never used this high dosage [850 mg]. We have suspected several times the B12 deficiency and we measured it in many cases, but we never found any cases of severe B12 deficiency.”

Dr. Schernthaner, who is professor of medicine at the University of Vienna in Austria, suggested the next step would be to perform a large trial of maybe 2,000 metformin users to see how often B12 deficiency really occurs.

Dr. Out agreed a larger trial would be the ideal and conceded that the effect size was small. However, with such a large number of patients using the drug worldwide, potentially “many patients are at risk.”

He said a direct effect of metformin on neuropathy would perhaps not be found by general screening because of its protective effect via improved glycemic control, “so you may miss B12 deficiency–induced neuropathy.” Measuring MMA, where possible, may be a solution.

STOCKHOLM – Clinicians might want to consider more routinely monitoring levels of vitamin B12 in their diabetic patients who are using metformin, according to new data from the HOME (Hyperinsulinaemia: the Outcome of Its Metabolic Effects) randomized controlled trial, which showed that B12 depletion was linked to neurotoxicity.

The new study findings, presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, showed that metformin increased levels of serum methylmalonic acid (MMA), the gold standard biomarker of tissue B12 deficiency, and that this in turn was linked to neuropathy measured using a validated score.

“We earlier showed that metformin causes B12 deficiency (<150 pmol/L) with a number needed to harm of 14 after 4.3 years,” said study investigator Dr. Mattijs Out of Bethesda Diabetes Research Center in Hoogeveen, the Netherlands, referring to the original results of the trial (BMJ. 2010;340:c2181).

“Today I showed you that metformin increases MMA, dose dependently and progressively over time,” he added. “Metformin has two opposite effects on neuropathy,” he continued, “a neuroprotective effect by improving glycemic control and a neurotoxic effect by inducing B12 depletion.”

Dr. Out noted that metformin remains the cornerstone of type 2 diabetes therapy with over 100 million prescriptions per year, putting many patients at risk for B12 deficiency and its consequences.

Current guidelines from the American Diabetes Association and EASD mention B12 deficiency as a potential downside of metformin use but do not go so far as giving specific recommendations because of lack of evidence on whether screening should be routinely performed or if vitamin B12 supplements should be given.

“Consequences of vitamin B12 deficiency, such as neuropathy or mental changes, may be profound,” Dr. Out said. Changes because of B12 deficits can be difficult to diagnose because they may be ascribed to old age or diabetes itself, and they may become irreversible if unchecked, he observed. Diagnosing and managing B12 deficiency is, in theory, “easy, cheap, and effective,” he said. A new trial would be needed, however, to determine whether screening for B12 deficiency or supplementation would be the better approach.

In the current study, structural equation monitoring (SEM) was used to determine the likely effects of metformin on the Valk neuropathy score (Diabetes Med. 1992;9:716-21) directly and via effects on hemoglobin A1c and MMA. The analysis involved 390 insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes who were also treated with 850 mg metformin or placebo up to three times daily for 52 months. Over a 4.3-year follow-up period, patients had HbA1c and neuropathy scores measured 17 times, and MMA was measured at six visits.

Compared with placebo, metformin use was associated with a significant (P= .001) 0.039 micromol/L (95% confidence interval, 0.019-0.055) increase in MMA over the course of the study.

While there was no significant difference in neuropathy scores between the placebo- and metformin-treated groups, SEM showed that metformin had a beneficial effect on lowering the neuropathy score via lowering HbA1c and an adverse effect on the neuropathy score by increasing MMA levels. Overall, metformin was associated with a 0.25-point increase in the neuropathy score, suggesting the net effect of the oral hypoglycemic drug is a negative one as higher scores mean worse neuropathy.

After the presentation of the findings, session chair Dr. Guntram Schernthaner commented: “In my center in Vienna, we have been using metformin for 30 years, but we have never used this high dosage [850 mg]. We have suspected several times the B12 deficiency and we measured it in many cases, but we never found any cases of severe B12 deficiency.”

Dr. Schernthaner, who is professor of medicine at the University of Vienna in Austria, suggested the next step would be to perform a large trial of maybe 2,000 metformin users to see how often B12 deficiency really occurs.

Dr. Out agreed a larger trial would be the ideal and conceded that the effect size was small. However, with such a large number of patients using the drug worldwide, potentially “many patients are at risk.”

He said a direct effect of metformin on neuropathy would perhaps not be found by general screening because of its protective effect via improved glycemic control, “so you may miss B12 deficiency–induced neuropathy.” Measuring MMA, where possible, may be a solution.

AT EASD 2015

EASD: Metformin-induced B12 deficiency linked to diabetic neuropathy

STOCKHOLM – Clinicians might want to consider more routinely monitoring levels of vitamin B12 in their diabetic patients who are using metformin, according to new data from the HOME (Hyperinsulinaemia: the Outcome of Its Metabolic Effects) randomized controlled trial, which showed that B12 depletion was linked to neurotoxicity.

The new study findings, presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, showed that metformin increased levels of serum methylmalonic acid (MMA), the gold standard biomarker of tissue B12 deficiency, and that this in turn was linked to neuropathy measured using a validated score.

“We earlier showed that metformin causes B12 deficiency (<150 pmol/L) with a number needed to harm of 14 after 4.3 years,” said study investigator Dr. Mattijs Out of Bethesda Diabetes Research Center in Hoogeveen, the Netherlands, referring to the original results of the trial (BMJ. 2010;340:c2181).

“Today I showed you that metformin increases MMA, dose dependently and progressively over time,” he added. “Metformin has two opposite effects on neuropathy,” he continued, “a neuroprotective effect by improving glycemic control and a neurotoxic effect by inducing B12 depletion.”

Dr. Out noted that metformin remains the cornerstone of type 2 diabetes therapy with over 100 million prescriptions per year, putting many patients at risk for B12 deficiency and its consequences.

Current guidelines from the American Diabetes Association and EASD mention B12 deficiency as a potential downside of metformin use but do not go so far as giving specific recommendations because of lack of evidence on whether screening should be routinely performed or if vitamin B12 supplements should be given.

“Consequences of vitamin B12 deficiency, such as neuropathy or mental changes, may be profound,” Dr. Out said. Changes because of B12 deficits can be difficult to diagnose because they may be ascribed to old age or diabetes itself, and they may become irreversible if unchecked, he observed. Diagnosing and managing B12 deficiency is, in theory, “easy, cheap, and effective,” he said. A new trial would be needed, however, to determine whether screening for B12 deficiency or supplementation would be the better approach.

In the current study, structural equation monitoring (SEM) was used to determine the likely effects of metformin on the Valk neuropathy score (Diabetes Med. 1992;9:716-21) directly and via effects on hemoglobin A1c and MMA. The analysis involved 390 insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes who were also treated with 850 mg metformin or placebo up to three times daily for 52 months. Over a 4.3-year follow-up period, patients had HbA1c and neuropathy scores measured 17 times, and MMA was measured at six visits.

Compared with placebo, metformin use was associated with a significant (P= .001) 0.039 micromol/L (95% confidence interval, 0.019-0.055) increase in MMA over the course of the study.

While there was no significant difference in neuropathy scores between the placebo- and metformin-treated groups, SEM showed that metformin had a beneficial effect on lowering the neuropathy score via lowering HbA1c and an adverse effect on the neuropathy score by increasing MMA levels. Overall, metformin was associated with a 0.25-point increase in the neuropathy score, suggesting the net effect of the oral hypoglycemic drug is a negative one as higher scores mean worse neuropathy.

After the presentation of the findings, session chair Dr. Guntram Schernthaner commented: “In my center in Vienna, we have been using metformin for 30 years, but we have never used this high dosage [850 mg]. We have suspected several times the B12 deficiency and we measured it in many cases, but we never found any cases of severe B12 deficiency.”

Dr. Schernthaner, who is professor of medicine at the University of Vienna in Austria, suggested the next step would be to perform a large trial of maybe 2,000 metformin users to see how often B12 deficiency really occurs.

Dr. Out agreed a larger trial would be the ideal and conceded that the effect size was small. However, with such a large number of patients using the drug worldwide, potentially “many patients are at risk.”

He said a direct effect of metformin on neuropathy would perhaps not be found by general screening because of its protective effect via improved glycemic control, “so you may miss B12 deficiency–induced neuropathy.” Measuring MMA, where possible, may be a solution.

STOCKHOLM – Clinicians might want to consider more routinely monitoring levels of vitamin B12 in their diabetic patients who are using metformin, according to new data from the HOME (Hyperinsulinaemia: the Outcome of Its Metabolic Effects) randomized controlled trial, which showed that B12 depletion was linked to neurotoxicity.

The new study findings, presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, showed that metformin increased levels of serum methylmalonic acid (MMA), the gold standard biomarker of tissue B12 deficiency, and that this in turn was linked to neuropathy measured using a validated score.

“We earlier showed that metformin causes B12 deficiency (<150 pmol/L) with a number needed to harm of 14 after 4.3 years,” said study investigator Dr. Mattijs Out of Bethesda Diabetes Research Center in Hoogeveen, the Netherlands, referring to the original results of the trial (BMJ. 2010;340:c2181).

“Today I showed you that metformin increases MMA, dose dependently and progressively over time,” he added. “Metformin has two opposite effects on neuropathy,” he continued, “a neuroprotective effect by improving glycemic control and a neurotoxic effect by inducing B12 depletion.”

Dr. Out noted that metformin remains the cornerstone of type 2 diabetes therapy with over 100 million prescriptions per year, putting many patients at risk for B12 deficiency and its consequences.

Current guidelines from the American Diabetes Association and EASD mention B12 deficiency as a potential downside of metformin use but do not go so far as giving specific recommendations because of lack of evidence on whether screening should be routinely performed or if vitamin B12 supplements should be given.

“Consequences of vitamin B12 deficiency, such as neuropathy or mental changes, may be profound,” Dr. Out said. Changes because of B12 deficits can be difficult to diagnose because they may be ascribed to old age or diabetes itself, and they may become irreversible if unchecked, he observed. Diagnosing and managing B12 deficiency is, in theory, “easy, cheap, and effective,” he said. A new trial would be needed, however, to determine whether screening for B12 deficiency or supplementation would be the better approach.

In the current study, structural equation monitoring (SEM) was used to determine the likely effects of metformin on the Valk neuropathy score (Diabetes Med. 1992;9:716-21) directly and via effects on hemoglobin A1c and MMA. The analysis involved 390 insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes who were also treated with 850 mg metformin or placebo up to three times daily for 52 months. Over a 4.3-year follow-up period, patients had HbA1c and neuropathy scores measured 17 times, and MMA was measured at six visits.

Compared with placebo, metformin use was associated with a significant (P= .001) 0.039 micromol/L (95% confidence interval, 0.019-0.055) increase in MMA over the course of the study.

While there was no significant difference in neuropathy scores between the placebo- and metformin-treated groups, SEM showed that metformin had a beneficial effect on lowering the neuropathy score via lowering HbA1c and an adverse effect on the neuropathy score by increasing MMA levels. Overall, metformin was associated with a 0.25-point increase in the neuropathy score, suggesting the net effect of the oral hypoglycemic drug is a negative one as higher scores mean worse neuropathy.

After the presentation of the findings, session chair Dr. Guntram Schernthaner commented: “In my center in Vienna, we have been using metformin for 30 years, but we have never used this high dosage [850 mg]. We have suspected several times the B12 deficiency and we measured it in many cases, but we never found any cases of severe B12 deficiency.”

Dr. Schernthaner, who is professor of medicine at the University of Vienna in Austria, suggested the next step would be to perform a large trial of maybe 2,000 metformin users to see how often B12 deficiency really occurs.

Dr. Out agreed a larger trial would be the ideal and conceded that the effect size was small. However, with such a large number of patients using the drug worldwide, potentially “many patients are at risk.”

He said a direct effect of metformin on neuropathy would perhaps not be found by general screening because of its protective effect via improved glycemic control, “so you may miss B12 deficiency–induced neuropathy.” Measuring MMA, where possible, may be a solution.

STOCKHOLM – Clinicians might want to consider more routinely monitoring levels of vitamin B12 in their diabetic patients who are using metformin, according to new data from the HOME (Hyperinsulinaemia: the Outcome of Its Metabolic Effects) randomized controlled trial, which showed that B12 depletion was linked to neurotoxicity.

The new study findings, presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, showed that metformin increased levels of serum methylmalonic acid (MMA), the gold standard biomarker of tissue B12 deficiency, and that this in turn was linked to neuropathy measured using a validated score.

“We earlier showed that metformin causes B12 deficiency (<150 pmol/L) with a number needed to harm of 14 after 4.3 years,” said study investigator Dr. Mattijs Out of Bethesda Diabetes Research Center in Hoogeveen, the Netherlands, referring to the original results of the trial (BMJ. 2010;340:c2181).

“Today I showed you that metformin increases MMA, dose dependently and progressively over time,” he added. “Metformin has two opposite effects on neuropathy,” he continued, “a neuroprotective effect by improving glycemic control and a neurotoxic effect by inducing B12 depletion.”

Dr. Out noted that metformin remains the cornerstone of type 2 diabetes therapy with over 100 million prescriptions per year, putting many patients at risk for B12 deficiency and its consequences.

Current guidelines from the American Diabetes Association and EASD mention B12 deficiency as a potential downside of metformin use but do not go so far as giving specific recommendations because of lack of evidence on whether screening should be routinely performed or if vitamin B12 supplements should be given.

“Consequences of vitamin B12 deficiency, such as neuropathy or mental changes, may be profound,” Dr. Out said. Changes because of B12 deficits can be difficult to diagnose because they may be ascribed to old age or diabetes itself, and they may become irreversible if unchecked, he observed. Diagnosing and managing B12 deficiency is, in theory, “easy, cheap, and effective,” he said. A new trial would be needed, however, to determine whether screening for B12 deficiency or supplementation would be the better approach.

In the current study, structural equation monitoring (SEM) was used to determine the likely effects of metformin on the Valk neuropathy score (Diabetes Med. 1992;9:716-21) directly and via effects on hemoglobin A1c and MMA. The analysis involved 390 insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes who were also treated with 850 mg metformin or placebo up to three times daily for 52 months. Over a 4.3-year follow-up period, patients had HbA1c and neuropathy scores measured 17 times, and MMA was measured at six visits.

Compared with placebo, metformin use was associated with a significant (P= .001) 0.039 micromol/L (95% confidence interval, 0.019-0.055) increase in MMA over the course of the study.

While there was no significant difference in neuropathy scores between the placebo- and metformin-treated groups, SEM showed that metformin had a beneficial effect on lowering the neuropathy score via lowering HbA1c and an adverse effect on the neuropathy score by increasing MMA levels. Overall, metformin was associated with a 0.25-point increase in the neuropathy score, suggesting the net effect of the oral hypoglycemic drug is a negative one as higher scores mean worse neuropathy.

After the presentation of the findings, session chair Dr. Guntram Schernthaner commented: “In my center in Vienna, we have been using metformin for 30 years, but we have never used this high dosage [850 mg]. We have suspected several times the B12 deficiency and we measured it in many cases, but we never found any cases of severe B12 deficiency.”

Dr. Schernthaner, who is professor of medicine at the University of Vienna in Austria, suggested the next step would be to perform a large trial of maybe 2,000 metformin users to see how often B12 deficiency really occurs.

Dr. Out agreed a larger trial would be the ideal and conceded that the effect size was small. However, with such a large number of patients using the drug worldwide, potentially “many patients are at risk.”

He said a direct effect of metformin on neuropathy would perhaps not be found by general screening because of its protective effect via improved glycemic control, “so you may miss B12 deficiency–induced neuropathy.” Measuring MMA, where possible, may be a solution.

AT EASD 2015

Key clinical point: Metformin has an overall detrimental effect on neuropathy mediated by its effect on MMA, a specific biomarker of B12 deficiency.

Major finding: Metformin use was associated with a significant (P = .001) 0.04 micromol/L increase in MMA over the course of the study when compared with placebo.

Data source: A prospective, randomized controlled trial of 390 insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes who were randomized to metformin or placebo for 4.3 years.

Disclosures: Dr. Out reported that he had no disclosures. The HOME study was supported by Takeda, Lifescan, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, and Novo Nordisk.

EASD: Liraglutide lowers HbA1c when added to insulin in longstanding type 2 diabetes

STOCKHOLM – Adding liraglutide to multiple daily insulin injections helped stabilize blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes, while also resulting in weight loss and reduction of daily insulin doses.

All this was accomplished without an increase in the risk of hypoglycemia, Dr. Marcus Lind said at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

A randomized, placebo-controlled study showed that the approach was successful in patients with long-standing disease, said Dr. Lind of the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. “We used to think that incretin-based therapies were most helpful in early type 2 diabetes. This seems to confirm that they are effective during the entire disease process.”

The soon-to-be-published 24-week study examined the addition of liraglutide in 124 patients with type 2 diabetes of long duration (a mean of 17 years). They were overweight, with a mean body mass index of 33.5 (about 218 pounds). At baseline, their mean hemoglobin A1c was 9%; they were taking a mean of 105 units of insulin each day in about four injections.

The study’s primary endpoint was change in HbA1c at 24 weeks. This declined significantly more among those taking liraglutide than those taking a placebo (–1.6% vs. –0.4%). “This is a difference of 1.1%, which is very clinically significant,” Dr. Lind said.

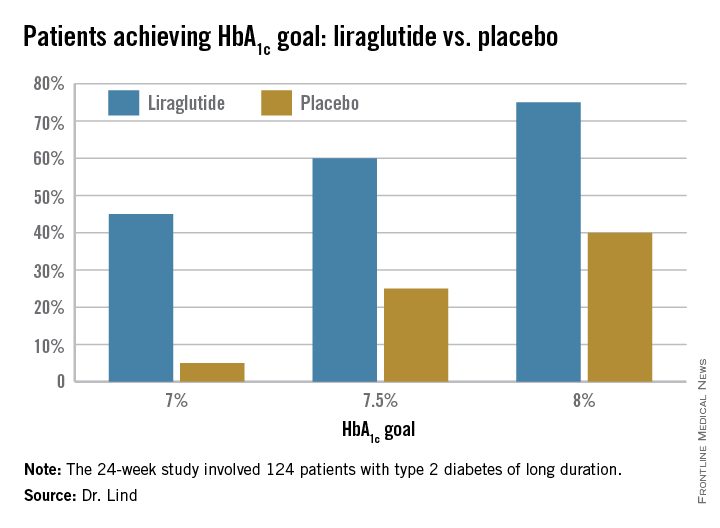

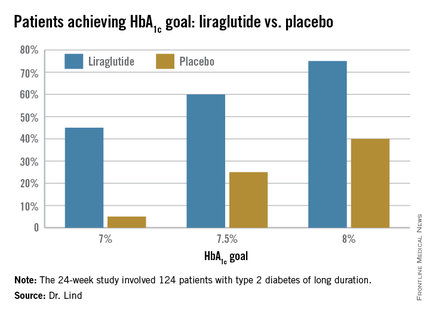

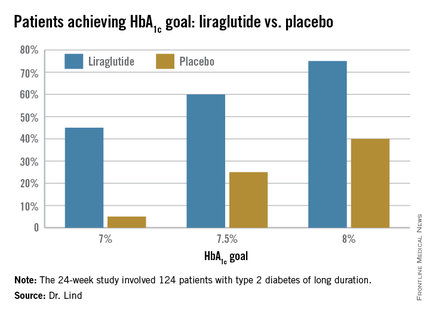

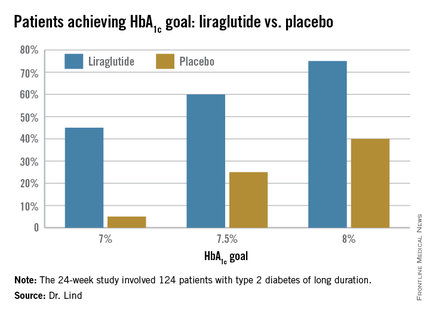

Dr. Lind assigned individualized HbA1c goals to patients, with the cutpoints of 7%, 7.5%, and 8%. Significantly more patients taking liraglutide were able to achieve those goals (see chart).

They also lost about 8 pounds more weight than did the placebo patients, and experienced a greater decrease in systolic blood pressure (–5.5 mm Hg more than placebo). There was no effect on diastolic blood pressure or lipids.

There were no severe hypoglycemic events in either group, nor any between-group difference in nonsevere events.

There were three serious adverse events among three patients taking liraglutide, and eight among four patients taking placebo; none of these were pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer.

Patients taking the study drug experienced significantly more nausea, especially at the beginning of the study, compared to the end of the study (22% vs. 5%).

The study was investigator initiated but received financial support from Novo Nordisk, which provided the drug. Dr. Lind disclosed financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies, including honoraria from Novo Nordisk.

STOCKHOLM – Adding liraglutide to multiple daily insulin injections helped stabilize blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes, while also resulting in weight loss and reduction of daily insulin doses.

All this was accomplished without an increase in the risk of hypoglycemia, Dr. Marcus Lind said at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

A randomized, placebo-controlled study showed that the approach was successful in patients with long-standing disease, said Dr. Lind of the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. “We used to think that incretin-based therapies were most helpful in early type 2 diabetes. This seems to confirm that they are effective during the entire disease process.”

The soon-to-be-published 24-week study examined the addition of liraglutide in 124 patients with type 2 diabetes of long duration (a mean of 17 years). They were overweight, with a mean body mass index of 33.5 (about 218 pounds). At baseline, their mean hemoglobin A1c was 9%; they were taking a mean of 105 units of insulin each day in about four injections.

The study’s primary endpoint was change in HbA1c at 24 weeks. This declined significantly more among those taking liraglutide than those taking a placebo (–1.6% vs. –0.4%). “This is a difference of 1.1%, which is very clinically significant,” Dr. Lind said.

Dr. Lind assigned individualized HbA1c goals to patients, with the cutpoints of 7%, 7.5%, and 8%. Significantly more patients taking liraglutide were able to achieve those goals (see chart).

They also lost about 8 pounds more weight than did the placebo patients, and experienced a greater decrease in systolic blood pressure (–5.5 mm Hg more than placebo). There was no effect on diastolic blood pressure or lipids.

There were no severe hypoglycemic events in either group, nor any between-group difference in nonsevere events.

There were three serious adverse events among three patients taking liraglutide, and eight among four patients taking placebo; none of these were pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer.

Patients taking the study drug experienced significantly more nausea, especially at the beginning of the study, compared to the end of the study (22% vs. 5%).

The study was investigator initiated but received financial support from Novo Nordisk, which provided the drug. Dr. Lind disclosed financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies, including honoraria from Novo Nordisk.

STOCKHOLM – Adding liraglutide to multiple daily insulin injections helped stabilize blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes, while also resulting in weight loss and reduction of daily insulin doses.

All this was accomplished without an increase in the risk of hypoglycemia, Dr. Marcus Lind said at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

A randomized, placebo-controlled study showed that the approach was successful in patients with long-standing disease, said Dr. Lind of the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. “We used to think that incretin-based therapies were most helpful in early type 2 diabetes. This seems to confirm that they are effective during the entire disease process.”

The soon-to-be-published 24-week study examined the addition of liraglutide in 124 patients with type 2 diabetes of long duration (a mean of 17 years). They were overweight, with a mean body mass index of 33.5 (about 218 pounds). At baseline, their mean hemoglobin A1c was 9%; they were taking a mean of 105 units of insulin each day in about four injections.

The study’s primary endpoint was change in HbA1c at 24 weeks. This declined significantly more among those taking liraglutide than those taking a placebo (–1.6% vs. –0.4%). “This is a difference of 1.1%, which is very clinically significant,” Dr. Lind said.

Dr. Lind assigned individualized HbA1c goals to patients, with the cutpoints of 7%, 7.5%, and 8%. Significantly more patients taking liraglutide were able to achieve those goals (see chart).

They also lost about 8 pounds more weight than did the placebo patients, and experienced a greater decrease in systolic blood pressure (–5.5 mm Hg more than placebo). There was no effect on diastolic blood pressure or lipids.

There were no severe hypoglycemic events in either group, nor any between-group difference in nonsevere events.

There were three serious adverse events among three patients taking liraglutide, and eight among four patients taking placebo; none of these were pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer.

Patients taking the study drug experienced significantly more nausea, especially at the beginning of the study, compared to the end of the study (22% vs. 5%).

The study was investigator initiated but received financial support from Novo Nordisk, which provided the drug. Dr. Lind disclosed financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies, including honoraria from Novo Nordisk.

AT EASD 2015

Key clinical point: Liraglutide added to multiple daily insulin injections lowered HbA1c significantly more than did placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Major finding: HbA1c at 24 weeks declined significantly more among those taking liraglutide than those taking a placebo (–1.6% vs. –0.4%).

Data source: A randomized, placebo-controlled study of 124 patients.

Disclosures: The study was investigator initiated but received financial support from Novo Nordisk, which provided the drug. Dr. Lind disclosed financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies, including honoraria from Novo Nordisk.

EASD: Pre-pregnancy weight, not gestational gain, affects later diabetes risk

STOCKHOLM – Women had a more than six-fold increased risk of developing diabetes more than a decade after they gave birth if they were overweight or obese at the start of their pregnancy, according to the results of a large epidemiological study.

The odds ratio for the development of diabetes was 6.4 (95% confidence interval, 3.5-11.6, P < .001) comparing women who had a body mass index above 25 at the start of pregnancy with those who were of a lower body weight.

The heavier women also were more likely to be obese (OR, 21.9; 95% CI, 16.3-29.5; P< .001), have developed cardiac (OR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.5-4.9; P= .001) or other endocrine (OR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.5-3.4; P< .001) diseases 10-17 years later.

“A high pre-pregnancy BMI significantly increases the risk of several diseases later in life, including diabetes and cardiac disease,” Dr. Ulrika Moll of Lund University, Sweden, said at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

The amount of weight gained during the pregnancy did not appear to matter, with no increase in the risk of cardiac or endocrine disease, even in women who gained more than the recommended weight set by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) guidelines. The IOM recommends that that women who are overweight should gain no more than 7–11.5 kg and those who are obese no more than 5-9 kg during their pregnancy. The mean maternal weight gain was 14.7 kg in the overweight group and 8.9 kg in the obese group.

Gaining more than 15 kg versus ≤15 kg during pregnancy did double the likelihood of women being overweight or obese in later life. A larger weight gain appeared to be protective against development of later psychiatric disease (OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.4-0.9; P= .03).

“A high weight gain during pregnancy did not have any implications on metabolic diseases within 10 years in our cohort,” Dr. Moll said. “These results have implications for the urgency of identification and care of the young women of childbearing age who struggle with being overweight or obese.”

Previous studies have shown that women who are overweight before they are pregnant and those that gain excessive amounts of weight during their pregnancies are more likely to experience poor outcomes, such as developing gestational diabetes or hypertension, needing a Cesarean section, giving birth prematurely, or having a larger baby. There was also some evidence that a high BMI at the start of pregnancy increases the risk form heart attack or stroke.

The aim of the current study was to see if a high maternal body weight at the start of pregnancy and a high or low gestational weight gain were associated with diseases later in life. Dr. Moll and associates used a population-based cohort of 23,524 women from southern Sweden and 30,559 records from the Swedish Medical Birth Register to find women who had at least one pregnancy and had completed a self-reported health questionnaire 10-17 years afterwards.

A total of 13,608 women were identified who had a mean pre-pregnancy BMI of 21.9, a follow-up BMI of 24.6 , and a mean gestational weight gain of 14.5 kg. Women were divided into groups based on their pre-pregnancy BMIt (≤25 or >25) and amount of they weight gained during their pregnancy (≤15 or >15 kg).

At follow up, the crude rates of diabetes, cardiac, and endocrine diseases were 1.6%, 3.3%, and 7.1%. There was a 0.4% rate of stroke and 2.3% rate of psychiatric disease; 37% of women were overweight, and 9.4% were obese.

In an interview, Dr. Naveed Sattar, professor of metabolic medicine at the Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences, University of Glasgow, Scotland, provided an independent comment on the findings. He said the data “strongly reiterate that the BMI with which you enter pregnancy gives you not only pregnancy complications but means that you are much more likely to be obese later on.”

Dr. Sattar added: “The interesting thing that it showed beautifully was that weight gain in pregnancy is inversely associated with the BMI at the beginning of pregnancy, so women who actually gain the least weight in pregnancy are the most obese. That suggests to me that the IOM criteria are very crude and perhaps not that useful.”

The IOM criteria may need reevaluation, he suggested. “The most important fact is that your weight when entering pregnancy is much more important than any weight gain during pregnancy,” he noted.

Dr. Moll had no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Sattar had no disclosures relevant to his comments.

STOCKHOLM – Women had a more than six-fold increased risk of developing diabetes more than a decade after they gave birth if they were overweight or obese at the start of their pregnancy, according to the results of a large epidemiological study.

The odds ratio for the development of diabetes was 6.4 (95% confidence interval, 3.5-11.6, P < .001) comparing women who had a body mass index above 25 at the start of pregnancy with those who were of a lower body weight.

The heavier women also were more likely to be obese (OR, 21.9; 95% CI, 16.3-29.5; P< .001), have developed cardiac (OR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.5-4.9; P= .001) or other endocrine (OR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.5-3.4; P< .001) diseases 10-17 years later.

“A high pre-pregnancy BMI significantly increases the risk of several diseases later in life, including diabetes and cardiac disease,” Dr. Ulrika Moll of Lund University, Sweden, said at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

The amount of weight gained during the pregnancy did not appear to matter, with no increase in the risk of cardiac or endocrine disease, even in women who gained more than the recommended weight set by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) guidelines. The IOM recommends that that women who are overweight should gain no more than 7–11.5 kg and those who are obese no more than 5-9 kg during their pregnancy. The mean maternal weight gain was 14.7 kg in the overweight group and 8.9 kg in the obese group.

Gaining more than 15 kg versus ≤15 kg during pregnancy did double the likelihood of women being overweight or obese in later life. A larger weight gain appeared to be protective against development of later psychiatric disease (OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.4-0.9; P= .03).

“A high weight gain during pregnancy did not have any implications on metabolic diseases within 10 years in our cohort,” Dr. Moll said. “These results have implications for the urgency of identification and care of the young women of childbearing age who struggle with being overweight or obese.”

Previous studies have shown that women who are overweight before they are pregnant and those that gain excessive amounts of weight during their pregnancies are more likely to experience poor outcomes, such as developing gestational diabetes or hypertension, needing a Cesarean section, giving birth prematurely, or having a larger baby. There was also some evidence that a high BMI at the start of pregnancy increases the risk form heart attack or stroke.

The aim of the current study was to see if a high maternal body weight at the start of pregnancy and a high or low gestational weight gain were associated with diseases later in life. Dr. Moll and associates used a population-based cohort of 23,524 women from southern Sweden and 30,559 records from the Swedish Medical Birth Register to find women who had at least one pregnancy and had completed a self-reported health questionnaire 10-17 years afterwards.

A total of 13,608 women were identified who had a mean pre-pregnancy BMI of 21.9, a follow-up BMI of 24.6 , and a mean gestational weight gain of 14.5 kg. Women were divided into groups based on their pre-pregnancy BMIt (≤25 or >25) and amount of they weight gained during their pregnancy (≤15 or >15 kg).

At follow up, the crude rates of diabetes, cardiac, and endocrine diseases were 1.6%, 3.3%, and 7.1%. There was a 0.4% rate of stroke and 2.3% rate of psychiatric disease; 37% of women were overweight, and 9.4% were obese.