User login

International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases (ICEID 2015)

A small number of neonatal listeriosis cases may be of nonmaternal origin

ATLANTA – While the majority of neonatal listeriosis cases are caused by consumption of contaminated food by the pregnant mother, the number of listeriosis cases of nonmaternal origin has grown into a small, but increasingly significant portion of total diagnoses.

This is according to a new study presented by Kelly A. Jackson of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Listeriosis cases associated with pregnancy were analyzed by collecting clinical, demographic, exposure, and microbiologic data from the Listeria Initiative, a CDC surveillance program conducted between 2004 and 2012. Ms. Jackson and her coinvestigators looked at the time from the onset of symptoms in the mother to delivery or recognition of fetal losses among cases of definite maternal origin. For those of potential nonmaternal origin, differences in gestational age at birth and recognition of fetal loss were compared.

Differentiation between definite maternal and possible nonmaternal cases were made by examining data on foodborne outbreak status, maternal symptoms, pregnancy outcome, maternal hospitalization, and neonatal death. In total, 554 pregnancy-associated listeriosis cases were examined, of which 338 (61%) were classified as definite maternal origin, 96 were classified as possible nonmaternal origin (17%), and 120 (22%) were excluded because either the neonatal isolates were collected 2-7 days after birth, pregnancy outcome was unknown, or the mothers were still pregnant at the time reporting occurred.

Seventy-two percent of listeriosis cases that definitely began with the mother showed symptoms within 7 days of fetal loss, with fever (80%) and chills (62%) being the most commonly reported symptoms. Both of those symptoms occurred far less frequently in cases of possible nonmaternal origin, with 38% reporting fevers and only 2% reporting chills.

Nearly 75% of mothers whose neonates had listeriosis developed symptoms less than a week before delivery or recognition of fetal loss, the authors explained; the median number of days from mothers’ onset to delivery was 2 days (range of 0-146 days), compared with a median of 4 days (range 0-151 days) from onset to recognition of fetal loss. The median gestational age of live-born infants with definite maternal origin of listeriosis was lower than in infants of possible nonmaternal origin: 35 weeks (range 24-42 weeks) versus 39 weeks (34-42 weeks) (P < .01).

Dr. Jackson and her colleagues call for further study into possible nonfoodborne sources of late-onset listeriosis in neonates, which would likely reveal the sources of exposure and from which prevention plans can be developed to protect mothers and their children.

Dr. Jackson did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – While the majority of neonatal listeriosis cases are caused by consumption of contaminated food by the pregnant mother, the number of listeriosis cases of nonmaternal origin has grown into a small, but increasingly significant portion of total diagnoses.

This is according to a new study presented by Kelly A. Jackson of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Listeriosis cases associated with pregnancy were analyzed by collecting clinical, demographic, exposure, and microbiologic data from the Listeria Initiative, a CDC surveillance program conducted between 2004 and 2012. Ms. Jackson and her coinvestigators looked at the time from the onset of symptoms in the mother to delivery or recognition of fetal losses among cases of definite maternal origin. For those of potential nonmaternal origin, differences in gestational age at birth and recognition of fetal loss were compared.

Differentiation between definite maternal and possible nonmaternal cases were made by examining data on foodborne outbreak status, maternal symptoms, pregnancy outcome, maternal hospitalization, and neonatal death. In total, 554 pregnancy-associated listeriosis cases were examined, of which 338 (61%) were classified as definite maternal origin, 96 were classified as possible nonmaternal origin (17%), and 120 (22%) were excluded because either the neonatal isolates were collected 2-7 days after birth, pregnancy outcome was unknown, or the mothers were still pregnant at the time reporting occurred.

Seventy-two percent of listeriosis cases that definitely began with the mother showed symptoms within 7 days of fetal loss, with fever (80%) and chills (62%) being the most commonly reported symptoms. Both of those symptoms occurred far less frequently in cases of possible nonmaternal origin, with 38% reporting fevers and only 2% reporting chills.

Nearly 75% of mothers whose neonates had listeriosis developed symptoms less than a week before delivery or recognition of fetal loss, the authors explained; the median number of days from mothers’ onset to delivery was 2 days (range of 0-146 days), compared with a median of 4 days (range 0-151 days) from onset to recognition of fetal loss. The median gestational age of live-born infants with definite maternal origin of listeriosis was lower than in infants of possible nonmaternal origin: 35 weeks (range 24-42 weeks) versus 39 weeks (34-42 weeks) (P < .01).

Dr. Jackson and her colleagues call for further study into possible nonfoodborne sources of late-onset listeriosis in neonates, which would likely reveal the sources of exposure and from which prevention plans can be developed to protect mothers and their children.

Dr. Jackson did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – While the majority of neonatal listeriosis cases are caused by consumption of contaminated food by the pregnant mother, the number of listeriosis cases of nonmaternal origin has grown into a small, but increasingly significant portion of total diagnoses.

This is according to a new study presented by Kelly A. Jackson of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Listeriosis cases associated with pregnancy were analyzed by collecting clinical, demographic, exposure, and microbiologic data from the Listeria Initiative, a CDC surveillance program conducted between 2004 and 2012. Ms. Jackson and her coinvestigators looked at the time from the onset of symptoms in the mother to delivery or recognition of fetal losses among cases of definite maternal origin. For those of potential nonmaternal origin, differences in gestational age at birth and recognition of fetal loss were compared.

Differentiation between definite maternal and possible nonmaternal cases were made by examining data on foodborne outbreak status, maternal symptoms, pregnancy outcome, maternal hospitalization, and neonatal death. In total, 554 pregnancy-associated listeriosis cases were examined, of which 338 (61%) were classified as definite maternal origin, 96 were classified as possible nonmaternal origin (17%), and 120 (22%) were excluded because either the neonatal isolates were collected 2-7 days after birth, pregnancy outcome was unknown, or the mothers were still pregnant at the time reporting occurred.

Seventy-two percent of listeriosis cases that definitely began with the mother showed symptoms within 7 days of fetal loss, with fever (80%) and chills (62%) being the most commonly reported symptoms. Both of those symptoms occurred far less frequently in cases of possible nonmaternal origin, with 38% reporting fevers and only 2% reporting chills.

Nearly 75% of mothers whose neonates had listeriosis developed symptoms less than a week before delivery or recognition of fetal loss, the authors explained; the median number of days from mothers’ onset to delivery was 2 days (range of 0-146 days), compared with a median of 4 days (range 0-151 days) from onset to recognition of fetal loss. The median gestational age of live-born infants with definite maternal origin of listeriosis was lower than in infants of possible nonmaternal origin: 35 weeks (range 24-42 weeks) versus 39 weeks (34-42 weeks) (P < .01).

Dr. Jackson and her colleagues call for further study into possible nonfoodborne sources of late-onset listeriosis in neonates, which would likely reveal the sources of exposure and from which prevention plans can be developed to protect mothers and their children.

Dr. Jackson did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

AT ICEID 2015

Key clinical point: A small but significant portion of neonatal listeriosis cases may not be caused by consumption of contaminated food by the mother, requiring further study into late-onset listeriosis causes.

Major finding: Seventeen percent of 439 neonatal listeriosis cases reported were of possible nonmaternal origin, and fever and chills were far less common in the mothers in the possibly nonmaternal cases (38% and 2%, respectively) than in the cases definitely of maternal origin (80% and 62%, respectively).

Data source: 439 pregnancies affected by neonatal listeriosis between 2004 and 2012 in the Listeria Initiative, a CDC surveillance program.

Disclosures: Dr. Jackson did not disclosure any relevant financial disclosures.

Send Patients Reminders for Flu Vaccines, Study Says

ATLANTA – Mobile reminders from health care providers to their patients, notifying them to get influenza vaccinations, significantly increases the likelihood that those patients will get vaccinated, according to a study by Dr. Katherine A. Benedict and coinvestigators in the Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Benedict presented findings of the research at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The researchers used data from the March 2012 National Flu Survey, a CDC “random digit dial telephone survey” of influenza vaccination trends in adults 18 years of age and older. They analyzed the data to determine whether or not patients received reminders, recommendations, or offers for influenza vaccinations from their health care providers since July 1, 2011. They did a logistic regression analysis to determine if there was any relationship between influenza vaccination rates and receipt of recommendations from health care providers.

Almost 73% of adults reported visiting a physician at least once since July 1, 2011, the start of data collection for the March 2012 study cycle, with 17.2% reporting that they received a reminder from their doctors to get a flu vaccine. Overall, 45.5% of adults ultimately got vaccinated, with 75.6% of those who reported receiving a reminder saying that they also were offered vaccinations by their doctors.

Adults who received recommendations for influenza vaccination from their health care providers were most likely to get vaccinated, and had an unadjusted prevalence ratio of 2.09. Next likely were those who received vaccination offers (PR = 1.90), and those who simply received reminders (PR = 1.33). Furthermore, those between 50 and 64 years old were found more likely to receive a recommendation or offer – PR = 1.23 and PR = 1.09, respectively – than were those in the 18- to 49-year age range (PR = 1.06 for recommendation, PR = 0.99 for offer).

The takeaway from this, according to the investigators, is that reminders should be sent at least once at the beginning of each influenza season. Prevalence ratios were consistently higher for patients with more frequent visits to their health care providers, meaning that continued interaction with and communication from doctors increases the likelihood of vaccination. Dr. Benedict also recommended sending additional reminders throughout the season, and that patients should either seek out or be referred to doctors who offer influenza vaccinations themselves.

Dr. Benedict did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Mobile reminders from health care providers to their patients, notifying them to get influenza vaccinations, significantly increases the likelihood that those patients will get vaccinated, according to a study by Dr. Katherine A. Benedict and coinvestigators in the Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Benedict presented findings of the research at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The researchers used data from the March 2012 National Flu Survey, a CDC “random digit dial telephone survey” of influenza vaccination trends in adults 18 years of age and older. They analyzed the data to determine whether or not patients received reminders, recommendations, or offers for influenza vaccinations from their health care providers since July 1, 2011. They did a logistic regression analysis to determine if there was any relationship between influenza vaccination rates and receipt of recommendations from health care providers.

Almost 73% of adults reported visiting a physician at least once since July 1, 2011, the start of data collection for the March 2012 study cycle, with 17.2% reporting that they received a reminder from their doctors to get a flu vaccine. Overall, 45.5% of adults ultimately got vaccinated, with 75.6% of those who reported receiving a reminder saying that they also were offered vaccinations by their doctors.

Adults who received recommendations for influenza vaccination from their health care providers were most likely to get vaccinated, and had an unadjusted prevalence ratio of 2.09. Next likely were those who received vaccination offers (PR = 1.90), and those who simply received reminders (PR = 1.33). Furthermore, those between 50 and 64 years old were found more likely to receive a recommendation or offer – PR = 1.23 and PR = 1.09, respectively – than were those in the 18- to 49-year age range (PR = 1.06 for recommendation, PR = 0.99 for offer).

The takeaway from this, according to the investigators, is that reminders should be sent at least once at the beginning of each influenza season. Prevalence ratios were consistently higher for patients with more frequent visits to their health care providers, meaning that continued interaction with and communication from doctors increases the likelihood of vaccination. Dr. Benedict also recommended sending additional reminders throughout the season, and that patients should either seek out or be referred to doctors who offer influenza vaccinations themselves.

Dr. Benedict did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Mobile reminders from health care providers to their patients, notifying them to get influenza vaccinations, significantly increases the likelihood that those patients will get vaccinated, according to a study by Dr. Katherine A. Benedict and coinvestigators in the Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Benedict presented findings of the research at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The researchers used data from the March 2012 National Flu Survey, a CDC “random digit dial telephone survey” of influenza vaccination trends in adults 18 years of age and older. They analyzed the data to determine whether or not patients received reminders, recommendations, or offers for influenza vaccinations from their health care providers since July 1, 2011. They did a logistic regression analysis to determine if there was any relationship between influenza vaccination rates and receipt of recommendations from health care providers.

Almost 73% of adults reported visiting a physician at least once since July 1, 2011, the start of data collection for the March 2012 study cycle, with 17.2% reporting that they received a reminder from their doctors to get a flu vaccine. Overall, 45.5% of adults ultimately got vaccinated, with 75.6% of those who reported receiving a reminder saying that they also were offered vaccinations by their doctors.

Adults who received recommendations for influenza vaccination from their health care providers were most likely to get vaccinated, and had an unadjusted prevalence ratio of 2.09. Next likely were those who received vaccination offers (PR = 1.90), and those who simply received reminders (PR = 1.33). Furthermore, those between 50 and 64 years old were found more likely to receive a recommendation or offer – PR = 1.23 and PR = 1.09, respectively – than were those in the 18- to 49-year age range (PR = 1.06 for recommendation, PR = 0.99 for offer).

The takeaway from this, according to the investigators, is that reminders should be sent at least once at the beginning of each influenza season. Prevalence ratios were consistently higher for patients with more frequent visits to their health care providers, meaning that continued interaction with and communication from doctors increases the likelihood of vaccination. Dr. Benedict also recommended sending additional reminders throughout the season, and that patients should either seek out or be referred to doctors who offer influenza vaccinations themselves.

Dr. Benedict did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

AT ICEID 2015

Send patients reminders for flu vaccines, study says

ATLANTA – Mobile reminders from health care providers to their patients, notifying them to get influenza vaccinations, significantly increases the likelihood that those patients will get vaccinated, according to a study by Dr. Katherine A. Benedict and coinvestigators in the Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Benedict presented findings of the research at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The researchers used data from the March 2012 National Flu Survey, a CDC “random digit dial telephone survey” of influenza vaccination trends in adults 18 years of age and older. They analyzed the data to determine whether or not patients received reminders, recommendations, or offers for influenza vaccinations from their health care providers since July 1, 2011. They did a logistic regression analysis to determine if there was any relationship between influenza vaccination rates and receipt of recommendations from health care providers.

Almost 73% of adults reported visiting a physician at least once since July 1, 2011, the start of data collection for the March 2012 study cycle, with 17.2% reporting that they received a reminder from their doctors to get a flu vaccine. Overall, 45.5% of adults ultimately got vaccinated, with 75.6% of those who reported receiving a reminder saying that they also were offered vaccinations by their doctors.

Adults who received recommendations for influenza vaccination from their health care providers were most likely to get vaccinated, and had an unadjusted prevalence ratio of 2.09. Next likely were those who received vaccination offers (PR = 1.90), and those who simply received reminders (PR = 1.33). Furthermore, those between 50 and 64 years old were found more likely to receive a recommendation or offer – PR = 1.23 and PR = 1.09, respectively – than were those in the 18- to 49-year age range (PR = 1.06 for recommendation, PR = 0.99 for offer).

The takeaway from this, according to the investigators, is that reminders should be sent at least once at the beginning of each influenza season. Prevalence ratios were consistently higher for patients with more frequent visits to their health care providers, meaning that continued interaction with and communication from doctors increases the likelihood of vaccination. Dr. Benedict also recommended sending additional reminders throughout the season, and that patients should either seek out or be referred to doctors who offer influenza vaccinations themselves.

Dr. Benedict did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Mobile reminders from health care providers to their patients, notifying them to get influenza vaccinations, significantly increases the likelihood that those patients will get vaccinated, according to a study by Dr. Katherine A. Benedict and coinvestigators in the Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Benedict presented findings of the research at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The researchers used data from the March 2012 National Flu Survey, a CDC “random digit dial telephone survey” of influenza vaccination trends in adults 18 years of age and older. They analyzed the data to determine whether or not patients received reminders, recommendations, or offers for influenza vaccinations from their health care providers since July 1, 2011. They did a logistic regression analysis to determine if there was any relationship between influenza vaccination rates and receipt of recommendations from health care providers.

Almost 73% of adults reported visiting a physician at least once since July 1, 2011, the start of data collection for the March 2012 study cycle, with 17.2% reporting that they received a reminder from their doctors to get a flu vaccine. Overall, 45.5% of adults ultimately got vaccinated, with 75.6% of those who reported receiving a reminder saying that they also were offered vaccinations by their doctors.

Adults who received recommendations for influenza vaccination from their health care providers were most likely to get vaccinated, and had an unadjusted prevalence ratio of 2.09. Next likely were those who received vaccination offers (PR = 1.90), and those who simply received reminders (PR = 1.33). Furthermore, those between 50 and 64 years old were found more likely to receive a recommendation or offer – PR = 1.23 and PR = 1.09, respectively – than were those in the 18- to 49-year age range (PR = 1.06 for recommendation, PR = 0.99 for offer).

The takeaway from this, according to the investigators, is that reminders should be sent at least once at the beginning of each influenza season. Prevalence ratios were consistently higher for patients with more frequent visits to their health care providers, meaning that continued interaction with and communication from doctors increases the likelihood of vaccination. Dr. Benedict also recommended sending additional reminders throughout the season, and that patients should either seek out or be referred to doctors who offer influenza vaccinations themselves.

Dr. Benedict did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Mobile reminders from health care providers to their patients, notifying them to get influenza vaccinations, significantly increases the likelihood that those patients will get vaccinated, according to a study by Dr. Katherine A. Benedict and coinvestigators in the Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Benedict presented findings of the research at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The researchers used data from the March 2012 National Flu Survey, a CDC “random digit dial telephone survey” of influenza vaccination trends in adults 18 years of age and older. They analyzed the data to determine whether or not patients received reminders, recommendations, or offers for influenza vaccinations from their health care providers since July 1, 2011. They did a logistic regression analysis to determine if there was any relationship between influenza vaccination rates and receipt of recommendations from health care providers.

Almost 73% of adults reported visiting a physician at least once since July 1, 2011, the start of data collection for the March 2012 study cycle, with 17.2% reporting that they received a reminder from their doctors to get a flu vaccine. Overall, 45.5% of adults ultimately got vaccinated, with 75.6% of those who reported receiving a reminder saying that they also were offered vaccinations by their doctors.

Adults who received recommendations for influenza vaccination from their health care providers were most likely to get vaccinated, and had an unadjusted prevalence ratio of 2.09. Next likely were those who received vaccination offers (PR = 1.90), and those who simply received reminders (PR = 1.33). Furthermore, those between 50 and 64 years old were found more likely to receive a recommendation or offer – PR = 1.23 and PR = 1.09, respectively – than were those in the 18- to 49-year age range (PR = 1.06 for recommendation, PR = 0.99 for offer).

The takeaway from this, according to the investigators, is that reminders should be sent at least once at the beginning of each influenza season. Prevalence ratios were consistently higher for patients with more frequent visits to their health care providers, meaning that continued interaction with and communication from doctors increases the likelihood of vaccination. Dr. Benedict also recommended sending additional reminders throughout the season, and that patients should either seek out or be referred to doctors who offer influenza vaccinations themselves.

Dr. Benedict did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

AT ICEID 2015

Key clinical point: Sending patients reminders to get their influenza vaccinations can significantly increase the likelihood that these patients will actually go out and get the vaccine.

Major finding: Adults who received a recommendation for influenza vaccination were more likely to get vaccinated, with an adjusted prevalence ratio (APR) of 1.15.

Data source: Retrospective review of adults 18 years and older in the March 2012 National Flu Survey.

Disclosures: Dr. Benedict did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

ICEID: TCAD regimen shows promise against H3N2 flu variant

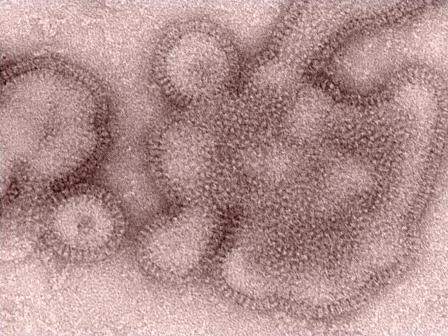

ATLANTA – Triple combination antiviral drug therapy offers a broad-spectrum treatment option for H3N2 variant influenza virus, according to findings from an in vitro study.

The finding suggest that the combination could play an important role in the event of an influenza pandemic, Carrie Sitz reported in a poster at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

After a human infection with the novel A/H3N2 variant was reported in 2011, and trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine was found to be of limited use, as it provided protection against H3N2 but not the H3N2 variant (H3N2v) in ferrets and elicited cross-protection against H3N2 in young adults but not older adults or children, a triple combination antiviral therapy (TCAD) regimen was considered.

Amantadine, oseltamivir carboxylate, and ribavirin each were tested alone and in double and triple combinations against the novel H3N2 variant virus carrying genes from avian, swine, and human origins. Triple therapy achieved a therapeutic effect with lower doses of component drugs, compared with monotherapies of antivirals as single agents, said Ms. Sitz, a microbiology research assistant at the Naval Health Research Center, San Diego.

The agents, which each have different mechanisms of action and which function at distinct points in the virus life cycle, were tested using the various combinations in 96-well plates seeded with Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) epithelial cells. They were found to produce synergistic antiviral activity, she noted.

A control experiment in the absence of the drugs also was performed.

Of note, amantadine had no activity as a single agent against H3N2v, even at 100 mcg/mL, the highest dose tested. However, amantadine did contribute to the synergy of the TCAD regimen. This effect was concentration dependent; the potential synergy volume increased steadily and significantly from about 300 to about 450, to about 575, and to about 600 as the amantadine concentration increased from +0.32, to +1.0, to +3.2, to +10, Ms. Sitz noted, adding that this may indicate that amantadine, which is known to have widespread resistance, can still play a therapeutic role in the setting of the TCAD regimen.

Vaccines are usually an effective safeguard against seasonal influenza but may be inadequate in seasons when a novel influenza emerges, resulting in compromised standard of care for treating the emergent viruses, she said, noting that this is especially true in immunocompromised patients.

“These issues point to the likelihood that we may be unprepared for a novel influenza virus displaying both virulence and transmissibility,” she added.

The current findings suggest that TCAD, which has previously been shown to be effective against seasonal and H5 influenza strains, is a broad-spectrum treatment option that could potentially play a role in pandemic preparedness. The mechanism by which oseltamivir carboxylate and ribavirin potentiate amantadine in combination therapy is unknown, and further testing is needed for evaluation, she concluded.

This study was sponsored by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

ATLANTA – Triple combination antiviral drug therapy offers a broad-spectrum treatment option for H3N2 variant influenza virus, according to findings from an in vitro study.

The finding suggest that the combination could play an important role in the event of an influenza pandemic, Carrie Sitz reported in a poster at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

After a human infection with the novel A/H3N2 variant was reported in 2011, and trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine was found to be of limited use, as it provided protection against H3N2 but not the H3N2 variant (H3N2v) in ferrets and elicited cross-protection against H3N2 in young adults but not older adults or children, a triple combination antiviral therapy (TCAD) regimen was considered.

Amantadine, oseltamivir carboxylate, and ribavirin each were tested alone and in double and triple combinations against the novel H3N2 variant virus carrying genes from avian, swine, and human origins. Triple therapy achieved a therapeutic effect with lower doses of component drugs, compared with monotherapies of antivirals as single agents, said Ms. Sitz, a microbiology research assistant at the Naval Health Research Center, San Diego.

The agents, which each have different mechanisms of action and which function at distinct points in the virus life cycle, were tested using the various combinations in 96-well plates seeded with Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) epithelial cells. They were found to produce synergistic antiviral activity, she noted.

A control experiment in the absence of the drugs also was performed.

Of note, amantadine had no activity as a single agent against H3N2v, even at 100 mcg/mL, the highest dose tested. However, amantadine did contribute to the synergy of the TCAD regimen. This effect was concentration dependent; the potential synergy volume increased steadily and significantly from about 300 to about 450, to about 575, and to about 600 as the amantadine concentration increased from +0.32, to +1.0, to +3.2, to +10, Ms. Sitz noted, adding that this may indicate that amantadine, which is known to have widespread resistance, can still play a therapeutic role in the setting of the TCAD regimen.

Vaccines are usually an effective safeguard against seasonal influenza but may be inadequate in seasons when a novel influenza emerges, resulting in compromised standard of care for treating the emergent viruses, she said, noting that this is especially true in immunocompromised patients.

“These issues point to the likelihood that we may be unprepared for a novel influenza virus displaying both virulence and transmissibility,” she added.

The current findings suggest that TCAD, which has previously been shown to be effective against seasonal and H5 influenza strains, is a broad-spectrum treatment option that could potentially play a role in pandemic preparedness. The mechanism by which oseltamivir carboxylate and ribavirin potentiate amantadine in combination therapy is unknown, and further testing is needed for evaluation, she concluded.

This study was sponsored by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

ATLANTA – Triple combination antiviral drug therapy offers a broad-spectrum treatment option for H3N2 variant influenza virus, according to findings from an in vitro study.

The finding suggest that the combination could play an important role in the event of an influenza pandemic, Carrie Sitz reported in a poster at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

After a human infection with the novel A/H3N2 variant was reported in 2011, and trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine was found to be of limited use, as it provided protection against H3N2 but not the H3N2 variant (H3N2v) in ferrets and elicited cross-protection against H3N2 in young adults but not older adults or children, a triple combination antiviral therapy (TCAD) regimen was considered.

Amantadine, oseltamivir carboxylate, and ribavirin each were tested alone and in double and triple combinations against the novel H3N2 variant virus carrying genes from avian, swine, and human origins. Triple therapy achieved a therapeutic effect with lower doses of component drugs, compared with monotherapies of antivirals as single agents, said Ms. Sitz, a microbiology research assistant at the Naval Health Research Center, San Diego.

The agents, which each have different mechanisms of action and which function at distinct points in the virus life cycle, were tested using the various combinations in 96-well plates seeded with Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) epithelial cells. They were found to produce synergistic antiviral activity, she noted.

A control experiment in the absence of the drugs also was performed.

Of note, amantadine had no activity as a single agent against H3N2v, even at 100 mcg/mL, the highest dose tested. However, amantadine did contribute to the synergy of the TCAD regimen. This effect was concentration dependent; the potential synergy volume increased steadily and significantly from about 300 to about 450, to about 575, and to about 600 as the amantadine concentration increased from +0.32, to +1.0, to +3.2, to +10, Ms. Sitz noted, adding that this may indicate that amantadine, which is known to have widespread resistance, can still play a therapeutic role in the setting of the TCAD regimen.

Vaccines are usually an effective safeguard against seasonal influenza but may be inadequate in seasons when a novel influenza emerges, resulting in compromised standard of care for treating the emergent viruses, she said, noting that this is especially true in immunocompromised patients.

“These issues point to the likelihood that we may be unprepared for a novel influenza virus displaying both virulence and transmissibility,” she added.

The current findings suggest that TCAD, which has previously been shown to be effective against seasonal and H5 influenza strains, is a broad-spectrum treatment option that could potentially play a role in pandemic preparedness. The mechanism by which oseltamivir carboxylate and ribavirin potentiate amantadine in combination therapy is unknown, and further testing is needed for evaluation, she concluded.

This study was sponsored by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

AT ICEID 2015

Key clinical point: Triple combination antiviral drug therapy, or TCAD, offers a broad-spectrum treatment option for H3N2 variant influenza virus.

Major finding: Triple therapy achieved a therapeutic effect with lower doses of component drugs, compared with monotherapies of antivirals as single agents.

Data source: An in vitro study of TCAD for H3N2v.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

ICEID: Data highlight biofilm role in waterborne illness

ATLANTA – Emerging biofilm-associated pathogens are overtaking those transmitted by the fecal-oral route as the most-common cause of death from waterborne illness in the United States, according to findings from a review of administrative and disease-specific surveillance data.

Between 2003 and 2009, a mean of 2,516 deaths occurred per year as a result of exposure to 1 of more of 14 different waterborne germs or diseases, including campylobacteriosis, cryptosporidiosis, Escherichia coli infections, free-living amoeba, giardiasis, hemolytic uremic syndrome, hepatitis A, Legionnaires’ disease, nontuberculous Mycobacterium, otitis externa, Pseudomonas, salmonellosis, shigellosis, and vibriosis, Julia Gargano, Ph.D., reported in a poster at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The most commonly documented causes of death, accounting for 88% of deaths, were Pseudomonas pneumonia or P. septicemia, nontuberculosis Mycobacterium, and Legionnaires’ disease – all biofilm pathogens. For those illnesses potentially linked to ingestion of contaminated water – as opposed to those associated with inhalation and contact – the most-commonly documented causes of death were hepatitis A, hemolytic uremic syndrome, and vibriosis, noted Dr. Gargano of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Atlanta.

The findings were obtained from U.S. death certificates, the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, and disease-specific surveillance.

Although surveillance data consistently show that transmission of waterborne diarrheal diseases continue, such diseases are rarely fatal in the United States. Further, advances in water treatment and sanitation have reduced the burden of such diseases.

The findings of this study demonstrate that the burden of mortality has shifted.

“This is the first time the annual number of deaths due to potentially waterborne disease has been calculated, and [the findings] highlight the emerging trend in biofilm-related illness,” she wrote.

Dr. Gargano reported having no financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Emerging biofilm-associated pathogens are overtaking those transmitted by the fecal-oral route as the most-common cause of death from waterborne illness in the United States, according to findings from a review of administrative and disease-specific surveillance data.

Between 2003 and 2009, a mean of 2,516 deaths occurred per year as a result of exposure to 1 of more of 14 different waterborne germs or diseases, including campylobacteriosis, cryptosporidiosis, Escherichia coli infections, free-living amoeba, giardiasis, hemolytic uremic syndrome, hepatitis A, Legionnaires’ disease, nontuberculous Mycobacterium, otitis externa, Pseudomonas, salmonellosis, shigellosis, and vibriosis, Julia Gargano, Ph.D., reported in a poster at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The most commonly documented causes of death, accounting for 88% of deaths, were Pseudomonas pneumonia or P. septicemia, nontuberculosis Mycobacterium, and Legionnaires’ disease – all biofilm pathogens. For those illnesses potentially linked to ingestion of contaminated water – as opposed to those associated with inhalation and contact – the most-commonly documented causes of death were hepatitis A, hemolytic uremic syndrome, and vibriosis, noted Dr. Gargano of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Atlanta.

The findings were obtained from U.S. death certificates, the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, and disease-specific surveillance.

Although surveillance data consistently show that transmission of waterborne diarrheal diseases continue, such diseases are rarely fatal in the United States. Further, advances in water treatment and sanitation have reduced the burden of such diseases.

The findings of this study demonstrate that the burden of mortality has shifted.

“This is the first time the annual number of deaths due to potentially waterborne disease has been calculated, and [the findings] highlight the emerging trend in biofilm-related illness,” she wrote.

Dr. Gargano reported having no financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Emerging biofilm-associated pathogens are overtaking those transmitted by the fecal-oral route as the most-common cause of death from waterborne illness in the United States, according to findings from a review of administrative and disease-specific surveillance data.

Between 2003 and 2009, a mean of 2,516 deaths occurred per year as a result of exposure to 1 of more of 14 different waterborne germs or diseases, including campylobacteriosis, cryptosporidiosis, Escherichia coli infections, free-living amoeba, giardiasis, hemolytic uremic syndrome, hepatitis A, Legionnaires’ disease, nontuberculous Mycobacterium, otitis externa, Pseudomonas, salmonellosis, shigellosis, and vibriosis, Julia Gargano, Ph.D., reported in a poster at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The most commonly documented causes of death, accounting for 88% of deaths, were Pseudomonas pneumonia or P. septicemia, nontuberculosis Mycobacterium, and Legionnaires’ disease – all biofilm pathogens. For those illnesses potentially linked to ingestion of contaminated water – as opposed to those associated with inhalation and contact – the most-commonly documented causes of death were hepatitis A, hemolytic uremic syndrome, and vibriosis, noted Dr. Gargano of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Atlanta.

The findings were obtained from U.S. death certificates, the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, and disease-specific surveillance.

Although surveillance data consistently show that transmission of waterborne diarrheal diseases continue, such diseases are rarely fatal in the United States. Further, advances in water treatment and sanitation have reduced the burden of such diseases.

The findings of this study demonstrate that the burden of mortality has shifted.

“This is the first time the annual number of deaths due to potentially waterborne disease has been calculated, and [the findings] highlight the emerging trend in biofilm-related illness,” she wrote.

Dr. Gargano reported having no financial disclosures.

AT ICEID 2015

Key clinical point: Emerging biofilm-associated pathogens are overtaking those transmitted by the fecal-oral route as the most-common cause of death from waterborne illness in the United States.

Major finding: 88% of deaths resulted from Pseudomonas pneumonia or P. septicemia, nontuberculosis Mycobacterium, and Legionnaires’ disease – all biofilm pathogens.

Data source: A review of administrative and disease-specific surveillance data.

Disclosures: Dr. Gargano reported having no financial disclosures.

Jamestown Canyon virus detected in humans in Minnesota

ATLANTA – A mosquito-borne illness that has been mainly limited to white-tailed deer throughout North America is emerging as a more frequent cause of human disease, according to a report from the Minnesota Department of Health.

The Jamestown Canyon virus (JCV), a member of the California serogroup of bunyaviruses likely transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected Aedes-species mosquito, was first detected in a human in Minnesota in 2013. Due to suspicion that cases were being missed by an assay in use at the time in Minnesota, which had relatively poor sensitivity for detecting Jamestown Canyon virus, an enzyme immunoassay specific to JCV was put into use in 2014 to test serum and cerebrospinal fluid specimens submitted for other arboviral testing. Subsequently, an additional six cases were identified, Elizabeth Schiffman reported at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Between May and October of 2014, 141 serum or cerebrospinal fluid samples from 107 unique patients were tested. Of these, 20 samples from 17 patients initially tested positive for JCV; further testing at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta confirmed the findings in 7 specimens from 6 patients, said Ms. Schiffman, an epidemiologist at the Minnesota Department of Health, St. Paul.

Findings from other specimens were pending at the time of her presentation.

The initial patient was a 49-year-old man who had generalized symptoms, including myalgia, fatigue, and nausea for about week, who then was hospitalized after experiencing sudden onset of fever, disorientation, and aphasia. Viral encephalitis was suspected, and specimens sent to the Minnesota Department of Health, then to the CDC, were positive for JCV. The other patients with confirmed JCV ranged in age from 11 to 77 years (median, 56).

Illness onset was between late May and early September, and patients presented with symptoms typical of mosquito-borne illnesses, including fever, fatigue, myalgia/arthralgia, and/or headache, although clinical syndromes varied among individuals.

“Three patients were classified as having meningoencephalitis, three had fever without neurological involvement, and one patient developed acute flaccid paralysis,” Ms. Schiffman said, adding that six of the seven patients were hospitalized with duration ranging from 4 to 20 days (median, 7 days), and three were discharged to acute rehabilitation facilities for further care.

Although only three patients were classified as having neuroinvasive disease, five of the seven reported symptoms suggestive of some neurologic involvement, ranging from mild confusion and altered mental status, to aphasia, ataxia, and seizure, she said.

An additional case from 2002 was retrospectively identified, she noted.

Although JCV has been known to cause disease in humans since the 1970s and has been nationally notifiable since 2004, it is rarely reported. In fact, only 31 human cases were reported in the United States from 2000 to 2015, she said, adding that the disease is likely underrecognized, particularly in more mild forms.

“It is expected that continued testing and increased awareness among health care providers of JCV as a possible cause of human disease – particularly viral encephalitis – will likely aid in the identification of additional cases in the future,” she said.

This work was funded by the Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity Cooperative Agreement with the CDC.

ATLANTA – A mosquito-borne illness that has been mainly limited to white-tailed deer throughout North America is emerging as a more frequent cause of human disease, according to a report from the Minnesota Department of Health.

The Jamestown Canyon virus (JCV), a member of the California serogroup of bunyaviruses likely transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected Aedes-species mosquito, was first detected in a human in Minnesota in 2013. Due to suspicion that cases were being missed by an assay in use at the time in Minnesota, which had relatively poor sensitivity for detecting Jamestown Canyon virus, an enzyme immunoassay specific to JCV was put into use in 2014 to test serum and cerebrospinal fluid specimens submitted for other arboviral testing. Subsequently, an additional six cases were identified, Elizabeth Schiffman reported at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Between May and October of 2014, 141 serum or cerebrospinal fluid samples from 107 unique patients were tested. Of these, 20 samples from 17 patients initially tested positive for JCV; further testing at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta confirmed the findings in 7 specimens from 6 patients, said Ms. Schiffman, an epidemiologist at the Minnesota Department of Health, St. Paul.

Findings from other specimens were pending at the time of her presentation.

The initial patient was a 49-year-old man who had generalized symptoms, including myalgia, fatigue, and nausea for about week, who then was hospitalized after experiencing sudden onset of fever, disorientation, and aphasia. Viral encephalitis was suspected, and specimens sent to the Minnesota Department of Health, then to the CDC, were positive for JCV. The other patients with confirmed JCV ranged in age from 11 to 77 years (median, 56).

Illness onset was between late May and early September, and patients presented with symptoms typical of mosquito-borne illnesses, including fever, fatigue, myalgia/arthralgia, and/or headache, although clinical syndromes varied among individuals.

“Three patients were classified as having meningoencephalitis, three had fever without neurological involvement, and one patient developed acute flaccid paralysis,” Ms. Schiffman said, adding that six of the seven patients were hospitalized with duration ranging from 4 to 20 days (median, 7 days), and three were discharged to acute rehabilitation facilities for further care.

Although only three patients were classified as having neuroinvasive disease, five of the seven reported symptoms suggestive of some neurologic involvement, ranging from mild confusion and altered mental status, to aphasia, ataxia, and seizure, she said.

An additional case from 2002 was retrospectively identified, she noted.

Although JCV has been known to cause disease in humans since the 1970s and has been nationally notifiable since 2004, it is rarely reported. In fact, only 31 human cases were reported in the United States from 2000 to 2015, she said, adding that the disease is likely underrecognized, particularly in more mild forms.

“It is expected that continued testing and increased awareness among health care providers of JCV as a possible cause of human disease – particularly viral encephalitis – will likely aid in the identification of additional cases in the future,” she said.

This work was funded by the Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity Cooperative Agreement with the CDC.

ATLANTA – A mosquito-borne illness that has been mainly limited to white-tailed deer throughout North America is emerging as a more frequent cause of human disease, according to a report from the Minnesota Department of Health.

The Jamestown Canyon virus (JCV), a member of the California serogroup of bunyaviruses likely transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected Aedes-species mosquito, was first detected in a human in Minnesota in 2013. Due to suspicion that cases were being missed by an assay in use at the time in Minnesota, which had relatively poor sensitivity for detecting Jamestown Canyon virus, an enzyme immunoassay specific to JCV was put into use in 2014 to test serum and cerebrospinal fluid specimens submitted for other arboviral testing. Subsequently, an additional six cases were identified, Elizabeth Schiffman reported at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Between May and October of 2014, 141 serum or cerebrospinal fluid samples from 107 unique patients were tested. Of these, 20 samples from 17 patients initially tested positive for JCV; further testing at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta confirmed the findings in 7 specimens from 6 patients, said Ms. Schiffman, an epidemiologist at the Minnesota Department of Health, St. Paul.

Findings from other specimens were pending at the time of her presentation.

The initial patient was a 49-year-old man who had generalized symptoms, including myalgia, fatigue, and nausea for about week, who then was hospitalized after experiencing sudden onset of fever, disorientation, and aphasia. Viral encephalitis was suspected, and specimens sent to the Minnesota Department of Health, then to the CDC, were positive for JCV. The other patients with confirmed JCV ranged in age from 11 to 77 years (median, 56).

Illness onset was between late May and early September, and patients presented with symptoms typical of mosquito-borne illnesses, including fever, fatigue, myalgia/arthralgia, and/or headache, although clinical syndromes varied among individuals.

“Three patients were classified as having meningoencephalitis, three had fever without neurological involvement, and one patient developed acute flaccid paralysis,” Ms. Schiffman said, adding that six of the seven patients were hospitalized with duration ranging from 4 to 20 days (median, 7 days), and three were discharged to acute rehabilitation facilities for further care.

Although only three patients were classified as having neuroinvasive disease, five of the seven reported symptoms suggestive of some neurologic involvement, ranging from mild confusion and altered mental status, to aphasia, ataxia, and seizure, she said.

An additional case from 2002 was retrospectively identified, she noted.

Although JCV has been known to cause disease in humans since the 1970s and has been nationally notifiable since 2004, it is rarely reported. In fact, only 31 human cases were reported in the United States from 2000 to 2015, she said, adding that the disease is likely underrecognized, particularly in more mild forms.

“It is expected that continued testing and increased awareness among health care providers of JCV as a possible cause of human disease – particularly viral encephalitis – will likely aid in the identification of additional cases in the future,” she said.

This work was funded by the Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity Cooperative Agreement with the CDC.

AT ICEID 2015

Key clinical point: A mosquito-borne illness that has been mainly limited to white-tailed deer throughout North America is emerging as a more frequent cause of human disease, according to a report from the Minnesota Department of Health.

Major finding: Seven specimens from six patients were confirmed as positive for JCV.

Data source: Laboratory testing of 141 serum or cerebrospinal fluid samples from 107 unique patients.

Disclosures: This work was funded by the Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity Cooperative Agreement with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

ICEID: Population-level data support ACIP flu vaccine recommendations

ATLANTA – Expanded influenza vaccination coverage among children between 2002 and 2012 appears to have provided direct benefit with respect to influenza-related hospitalizations among vaccinated children, according to an analysis of vaccination and hospitalization data.

Additionally, the coverage among children appears to have provided indirect benefits in adults, Cecile Viboud, Ph.D. of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., reported at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Between 2006-2007 and 2010-2011, the U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) broadened vaccination recommendations to include not only children aged 6-23 months, but also those aged 24-59 months, then those aged 5-18 years, and eventually all those over age 6 months. Consequently, the vaccine coverage rate increased from less than 5% in 2002 to about 52% in 2012 (and to about 70% in those under age 5 years). Modeling of weekly influenza-related hospitalization outcomes (pneumonia and influenza outcomes and respiratory and circulatory outcomes) provided solid evidence of a direct and significant protective effect of vaccination both in children under age 5 years and in those aged 5-19 years. This finding was consistent across disease outcomes, and remained significant in those under age 5 after adjusting for state, but the association was weaker with stratification by season, Dr. Viboud noted.

Further, hospitalization rates among working-age adults and seniors aged 65-74 years declined with increasing pediatric vaccine coverage, suggesting an indirect protective effect in that population, she said, noting that the vaccination rate among older adults remained stable across the study period.

No evidence was seen for an indirect protective effect among adults over age 74 years, she said.

Dr. Viboud and her colleagues used age-specific annual vaccination rates derived from the National Immunization Survey and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Age-specific rates of influenza-associated hospitalizations were estimated for each season during 1989-2012 by modeling weekly pneumonia and influenza outcomes plus respiratory and circulatory outcomes from the State Inpatient Databases of the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality.

“In a nutshell, we see strong statistical evidence for the direct protective effects of the influenza vaccination program in children on the basis of analyses of population-level hospitalization data, which supports the expansion of the ACIP flu vaccine recommendations in the past decade,” Dr. Viboud said in an interview. “We also find weak evidence of herd immunity effects, whereby hospitalization rates are reduced in adults. That the evidence is weak is perhaps not surprising given that vaccine uptake in children remains moderate (60% in most highly vaccinated states) and vaccine effectiveness is modest at 40%-60% depending on the season. Independent information from mathematical transmission models confirms that herd immunity benefits are expected to be low given these levels of vaccine coverage.”

The indirect effects may become clearer with increasing vaccine uptake, she added.

Dr. Viboud reported having no disclosures.

ATLANTA – Expanded influenza vaccination coverage among children between 2002 and 2012 appears to have provided direct benefit with respect to influenza-related hospitalizations among vaccinated children, according to an analysis of vaccination and hospitalization data.

Additionally, the coverage among children appears to have provided indirect benefits in adults, Cecile Viboud, Ph.D. of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., reported at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Between 2006-2007 and 2010-2011, the U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) broadened vaccination recommendations to include not only children aged 6-23 months, but also those aged 24-59 months, then those aged 5-18 years, and eventually all those over age 6 months. Consequently, the vaccine coverage rate increased from less than 5% in 2002 to about 52% in 2012 (and to about 70% in those under age 5 years). Modeling of weekly influenza-related hospitalization outcomes (pneumonia and influenza outcomes and respiratory and circulatory outcomes) provided solid evidence of a direct and significant protective effect of vaccination both in children under age 5 years and in those aged 5-19 years. This finding was consistent across disease outcomes, and remained significant in those under age 5 after adjusting for state, but the association was weaker with stratification by season, Dr. Viboud noted.

Further, hospitalization rates among working-age adults and seniors aged 65-74 years declined with increasing pediatric vaccine coverage, suggesting an indirect protective effect in that population, she said, noting that the vaccination rate among older adults remained stable across the study period.

No evidence was seen for an indirect protective effect among adults over age 74 years, she said.

Dr. Viboud and her colleagues used age-specific annual vaccination rates derived from the National Immunization Survey and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Age-specific rates of influenza-associated hospitalizations were estimated for each season during 1989-2012 by modeling weekly pneumonia and influenza outcomes plus respiratory and circulatory outcomes from the State Inpatient Databases of the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality.

“In a nutshell, we see strong statistical evidence for the direct protective effects of the influenza vaccination program in children on the basis of analyses of population-level hospitalization data, which supports the expansion of the ACIP flu vaccine recommendations in the past decade,” Dr. Viboud said in an interview. “We also find weak evidence of herd immunity effects, whereby hospitalization rates are reduced in adults. That the evidence is weak is perhaps not surprising given that vaccine uptake in children remains moderate (60% in most highly vaccinated states) and vaccine effectiveness is modest at 40%-60% depending on the season. Independent information from mathematical transmission models confirms that herd immunity benefits are expected to be low given these levels of vaccine coverage.”

The indirect effects may become clearer with increasing vaccine uptake, she added.

Dr. Viboud reported having no disclosures.

ATLANTA – Expanded influenza vaccination coverage among children between 2002 and 2012 appears to have provided direct benefit with respect to influenza-related hospitalizations among vaccinated children, according to an analysis of vaccination and hospitalization data.

Additionally, the coverage among children appears to have provided indirect benefits in adults, Cecile Viboud, Ph.D. of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., reported at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Between 2006-2007 and 2010-2011, the U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) broadened vaccination recommendations to include not only children aged 6-23 months, but also those aged 24-59 months, then those aged 5-18 years, and eventually all those over age 6 months. Consequently, the vaccine coverage rate increased from less than 5% in 2002 to about 52% in 2012 (and to about 70% in those under age 5 years). Modeling of weekly influenza-related hospitalization outcomes (pneumonia and influenza outcomes and respiratory and circulatory outcomes) provided solid evidence of a direct and significant protective effect of vaccination both in children under age 5 years and in those aged 5-19 years. This finding was consistent across disease outcomes, and remained significant in those under age 5 after adjusting for state, but the association was weaker with stratification by season, Dr. Viboud noted.

Further, hospitalization rates among working-age adults and seniors aged 65-74 years declined with increasing pediatric vaccine coverage, suggesting an indirect protective effect in that population, she said, noting that the vaccination rate among older adults remained stable across the study period.

No evidence was seen for an indirect protective effect among adults over age 74 years, she said.

Dr. Viboud and her colleagues used age-specific annual vaccination rates derived from the National Immunization Survey and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Age-specific rates of influenza-associated hospitalizations were estimated for each season during 1989-2012 by modeling weekly pneumonia and influenza outcomes plus respiratory and circulatory outcomes from the State Inpatient Databases of the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality.

“In a nutshell, we see strong statistical evidence for the direct protective effects of the influenza vaccination program in children on the basis of analyses of population-level hospitalization data, which supports the expansion of the ACIP flu vaccine recommendations in the past decade,” Dr. Viboud said in an interview. “We also find weak evidence of herd immunity effects, whereby hospitalization rates are reduced in adults. That the evidence is weak is perhaps not surprising given that vaccine uptake in children remains moderate (60% in most highly vaccinated states) and vaccine effectiveness is modest at 40%-60% depending on the season. Independent information from mathematical transmission models confirms that herd immunity benefits are expected to be low given these levels of vaccine coverage.”

The indirect effects may become clearer with increasing vaccine uptake, she added.

Dr. Viboud reported having no disclosures.

AT ICEID 2015

Key clinical point: Expanded influenza vaccination coverage in children provided direct benefits with respect to hospitalizations.

Major finding: Vaccine coverage rate increased from less than 5% in 2002 to about 52% in 2012 .

Data source: An analysis of vaccination and hospitalization data.

Disclosures: Dr. Viboud reported having no disclosures.

ICEID: Pertussis vaccination reduces disease severity

ATLANTA – Pertussis vaccination does not eliminate the risk of disease, but it does appear to reduce disease severity, according to findings from a study of more than 10,000 cases.

In fact, despite high acellular pertussis vaccine coverage in the United States, 48,277 cases were reported in 2012, and many of these were among vaccinated individuals – a result of waning protection over time following childhood pertussis vaccination, Lucy A. McNamara, Ph.D., of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta reported at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

To assess whether severe symptoms or complications are more common in those who are not fully vaccinated, Dr. McNamara and her colleagues identified a total of 10,092 pertussis case patients from the Enhanced Pertussis Surveillance/Emerging Infections Program network in 2010-2012 and collected case information through vaccine registries and interviews with physicians and patients at six network sites. Of those aged 3 months to 19 years, 81% were up to date for pertussis vaccinations for their age, and of adults, 45% had received Tdap.

Up-to-date status was protective against severe disease, defined as disease involving seizures, encephalopathy, pneumonia, or hospitalization, in children aged 7 months to 6 years, who had about a 60% reduction in risk, compared with those who were not up to date. Up-to-date status also reduced the risk of posttussive vomiting, which sometimes accompanies severe coughing fits, by about 25% in those aged 19 months to 64 years, she said, adding that the risk of vomiting after coughing was about 38% lower in this age group when patients received antibiotic treatment within 1 week of the start of the illness.

The effect on posttussive vomiting was independent of antibiotic treatment timing, which further underscores the value of both rapid treatment and completion of the pertussis vaccination schedule, she said.

Dr. McNamara reported having no disclosures.

ATLANTA – Pertussis vaccination does not eliminate the risk of disease, but it does appear to reduce disease severity, according to findings from a study of more than 10,000 cases.

In fact, despite high acellular pertussis vaccine coverage in the United States, 48,277 cases were reported in 2012, and many of these were among vaccinated individuals – a result of waning protection over time following childhood pertussis vaccination, Lucy A. McNamara, Ph.D., of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta reported at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

To assess whether severe symptoms or complications are more common in those who are not fully vaccinated, Dr. McNamara and her colleagues identified a total of 10,092 pertussis case patients from the Enhanced Pertussis Surveillance/Emerging Infections Program network in 2010-2012 and collected case information through vaccine registries and interviews with physicians and patients at six network sites. Of those aged 3 months to 19 years, 81% were up to date for pertussis vaccinations for their age, and of adults, 45% had received Tdap.

Up-to-date status was protective against severe disease, defined as disease involving seizures, encephalopathy, pneumonia, or hospitalization, in children aged 7 months to 6 years, who had about a 60% reduction in risk, compared with those who were not up to date. Up-to-date status also reduced the risk of posttussive vomiting, which sometimes accompanies severe coughing fits, by about 25% in those aged 19 months to 64 years, she said, adding that the risk of vomiting after coughing was about 38% lower in this age group when patients received antibiotic treatment within 1 week of the start of the illness.

The effect on posttussive vomiting was independent of antibiotic treatment timing, which further underscores the value of both rapid treatment and completion of the pertussis vaccination schedule, she said.

Dr. McNamara reported having no disclosures.

ATLANTA – Pertussis vaccination does not eliminate the risk of disease, but it does appear to reduce disease severity, according to findings from a study of more than 10,000 cases.

In fact, despite high acellular pertussis vaccine coverage in the United States, 48,277 cases were reported in 2012, and many of these were among vaccinated individuals – a result of waning protection over time following childhood pertussis vaccination, Lucy A. McNamara, Ph.D., of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta reported at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

To assess whether severe symptoms or complications are more common in those who are not fully vaccinated, Dr. McNamara and her colleagues identified a total of 10,092 pertussis case patients from the Enhanced Pertussis Surveillance/Emerging Infections Program network in 2010-2012 and collected case information through vaccine registries and interviews with physicians and patients at six network sites. Of those aged 3 months to 19 years, 81% were up to date for pertussis vaccinations for their age, and of adults, 45% had received Tdap.

Up-to-date status was protective against severe disease, defined as disease involving seizures, encephalopathy, pneumonia, or hospitalization, in children aged 7 months to 6 years, who had about a 60% reduction in risk, compared with those who were not up to date. Up-to-date status also reduced the risk of posttussive vomiting, which sometimes accompanies severe coughing fits, by about 25% in those aged 19 months to 64 years, she said, adding that the risk of vomiting after coughing was about 38% lower in this age group when patients received antibiotic treatment within 1 week of the start of the illness.

The effect on posttussive vomiting was independent of antibiotic treatment timing, which further underscores the value of both rapid treatment and completion of the pertussis vaccination schedule, she said.

Dr. McNamara reported having no disclosures.

AT ICEID 2015

Key clinical point: Pertussis vaccination does not eliminate the risk of disease, but it does reduce disease severity, according to findings from a study of more than 10,000 cases.

Major finding: The risk of severe disease in children aged 7 months to 6 years was about 60% lower in children with up-to-date status, compared with those who were not up to date on their pertussis vaccinations.

Data source: Surveillance data on 10,092 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. McNamara reported having no disclosures.

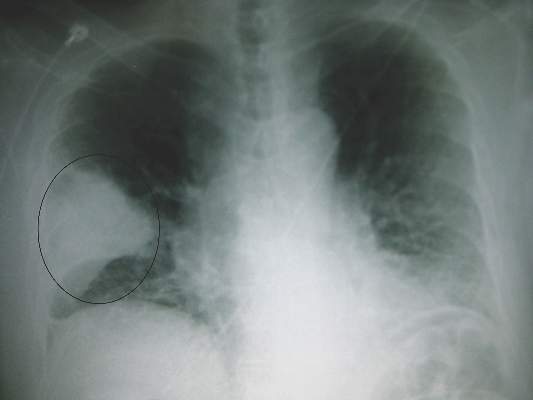

ICEID: Flu shots significantly decrease disease severity, duration

ATLANTA – Individuals who neglect to get their annual influenza vaccinations will likely experience more-severe symptoms and a longer duration of the illness if they contract the disease, specifically the A/H3N2 strain.

In a study of 155 influenza patients between 2009 and 2014, 138 (89%) were positive for influenza A virus, 111 (72%) of whom were vaccinated against influenza.

“We know that flu vaccines are about 60% effective, but of that remaining 40%, do they still get severe flu? The data from our study say no,” explained Dr. Eugene V. Millar of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md.

Sixty-six (48%) individuals contracted the A/H3N2 strain of the influenza virus; of these patients, those who did not get vaccinated reported higher average severity scores for upper respiratory symptoms (7 vs. 3), lower respiratory symptoms (7 vs. 3), systemic symptoms (9.5 vs. 6), and total symptoms (22 vs. 12) than did subjects who did get vaccinated (P less than .01).

“People ask me all the time why I bother getting a flu vaccine if it never works,” Dr. Millar said. “I tell them that if you’re walking around and talking to people, then it did work, even if you feel a little lousy; if you didn’t get that vaccination, you’d be on your back.”

Such disparity in the severity and duration of symptoms was not noted in 69 (50%) of the 155 influenza patients who contracted the A/H1N1 strain of the virus, nor in the 3 (2%) subjects who had an “untyped” form of influenza A. However, Dr. Millar cautioned that results regarding H1N1 may have been confounded by a couple of factors.

“As we’ve seen with the [H1N1] pandemic, it was just a pandemic of the sniffles, so it’s very hard to assess symptom severity when the differences are moderate to none,” Dr. Millar explained, adding that the variant strain of H3N2 which became prevalent during the 2014-2015 respiratory season proved to be the far more severe disease. Furthermore, patients found with A/H1N1 were more likely to be put on antivirals, making it impossible to look at vaccine effect.

In total, 884 patients with influenza-like illness were screened for inclusion in the study, from which the sample of 155 subjects was eventually derived. Median age of the 155 subjects was 30.6 (P = .61), mean body mass index was 27.6 kg/m2 (P = .07), males outnumbered females 88 to 67, and 106 subjects were active-duty military at the time they had influenza.

“These are healthy people presenting to outpatient [clinics], it’s very interesting to see if the same thing would hold true for the elderly or people with underlying medical conditions, since those are the people we’re really trying to protect not only from influenza, but its complications, as well, such as secondary bacterial pneumonia.”

Nine subjects (6%) had influenza during the 2009-2010 season, 56 (36%) during the 2010-2011 season, 16 (10%) during the 2011-2012 season, 38 (25%) during the 2012-2013 season, and 36 (23%) during the 2013-2014 season.

This study was supported by the Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program (IDCRP), a Department of Defense program carried out via the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, a division of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Millar did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Individuals who neglect to get their annual influenza vaccinations will likely experience more-severe symptoms and a longer duration of the illness if they contract the disease, specifically the A/H3N2 strain.

In a study of 155 influenza patients between 2009 and 2014, 138 (89%) were positive for influenza A virus, 111 (72%) of whom were vaccinated against influenza.

“We know that flu vaccines are about 60% effective, but of that remaining 40%, do they still get severe flu? The data from our study say no,” explained Dr. Eugene V. Millar of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md.

Sixty-six (48%) individuals contracted the A/H3N2 strain of the influenza virus; of these patients, those who did not get vaccinated reported higher average severity scores for upper respiratory symptoms (7 vs. 3), lower respiratory symptoms (7 vs. 3), systemic symptoms (9.5 vs. 6), and total symptoms (22 vs. 12) than did subjects who did get vaccinated (P less than .01).

“People ask me all the time why I bother getting a flu vaccine if it never works,” Dr. Millar said. “I tell them that if you’re walking around and talking to people, then it did work, even if you feel a little lousy; if you didn’t get that vaccination, you’d be on your back.”

Such disparity in the severity and duration of symptoms was not noted in 69 (50%) of the 155 influenza patients who contracted the A/H1N1 strain of the virus, nor in the 3 (2%) subjects who had an “untyped” form of influenza A. However, Dr. Millar cautioned that results regarding H1N1 may have been confounded by a couple of factors.

“As we’ve seen with the [H1N1] pandemic, it was just a pandemic of the sniffles, so it’s very hard to assess symptom severity when the differences are moderate to none,” Dr. Millar explained, adding that the variant strain of H3N2 which became prevalent during the 2014-2015 respiratory season proved to be the far more severe disease. Furthermore, patients found with A/H1N1 were more likely to be put on antivirals, making it impossible to look at vaccine effect.

In total, 884 patients with influenza-like illness were screened for inclusion in the study, from which the sample of 155 subjects was eventually derived. Median age of the 155 subjects was 30.6 (P = .61), mean body mass index was 27.6 kg/m2 (P = .07), males outnumbered females 88 to 67, and 106 subjects were active-duty military at the time they had influenza.

“These are healthy people presenting to outpatient [clinics], it’s very interesting to see if the same thing would hold true for the elderly or people with underlying medical conditions, since those are the people we’re really trying to protect not only from influenza, but its complications, as well, such as secondary bacterial pneumonia.”

Nine subjects (6%) had influenza during the 2009-2010 season, 56 (36%) during the 2010-2011 season, 16 (10%) during the 2011-2012 season, 38 (25%) during the 2012-2013 season, and 36 (23%) during the 2013-2014 season.

This study was supported by the Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program (IDCRP), a Department of Defense program carried out via the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, a division of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Millar did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Individuals who neglect to get their annual influenza vaccinations will likely experience more-severe symptoms and a longer duration of the illness if they contract the disease, specifically the A/H3N2 strain.

In a study of 155 influenza patients between 2009 and 2014, 138 (89%) were positive for influenza A virus, 111 (72%) of whom were vaccinated against influenza.

“We know that flu vaccines are about 60% effective, but of that remaining 40%, do they still get severe flu? The data from our study say no,” explained Dr. Eugene V. Millar of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md.

Sixty-six (48%) individuals contracted the A/H3N2 strain of the influenza virus; of these patients, those who did not get vaccinated reported higher average severity scores for upper respiratory symptoms (7 vs. 3), lower respiratory symptoms (7 vs. 3), systemic symptoms (9.5 vs. 6), and total symptoms (22 vs. 12) than did subjects who did get vaccinated (P less than .01).