User login

Pediatric Academic Societies (PAS): Annual Meeting

PAS: Low-dose hydrocortisone improves outcomes in extreme preemies

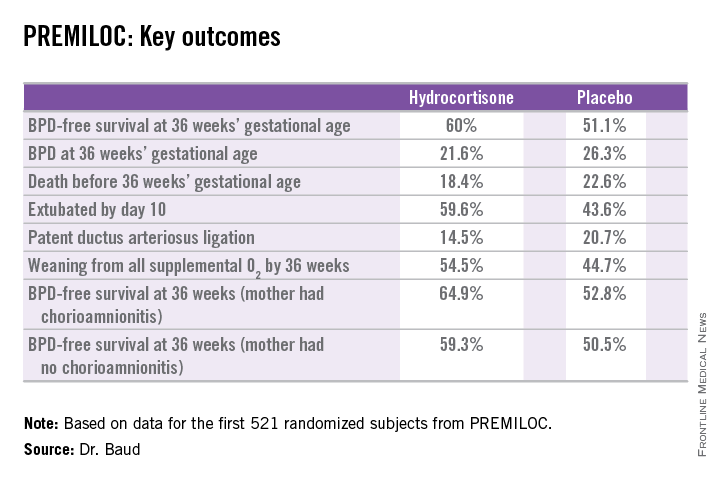

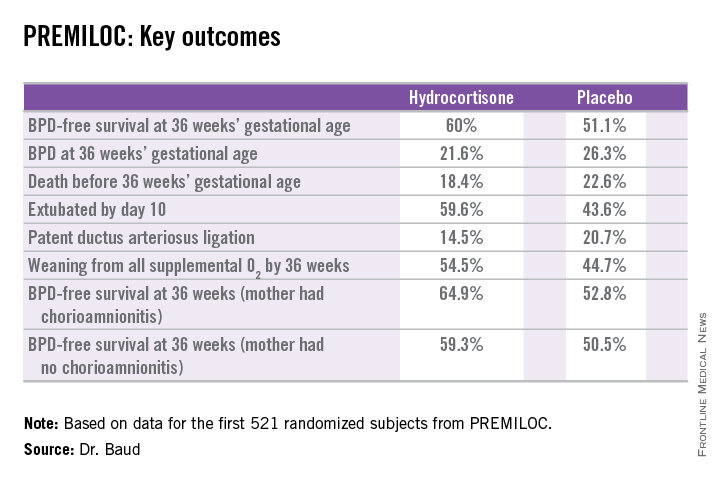

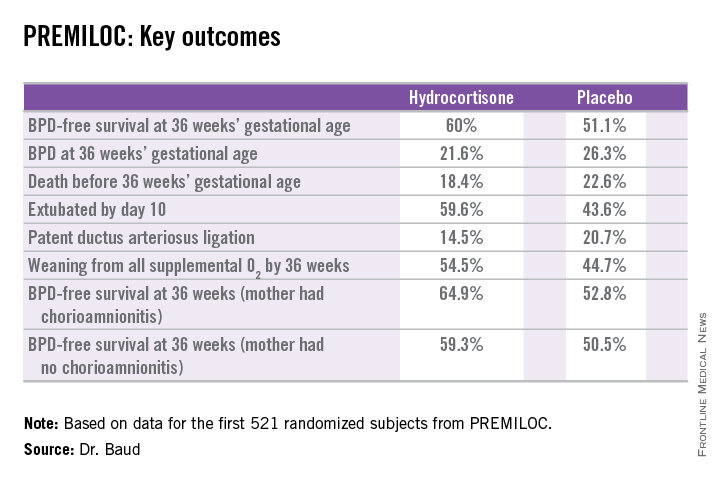

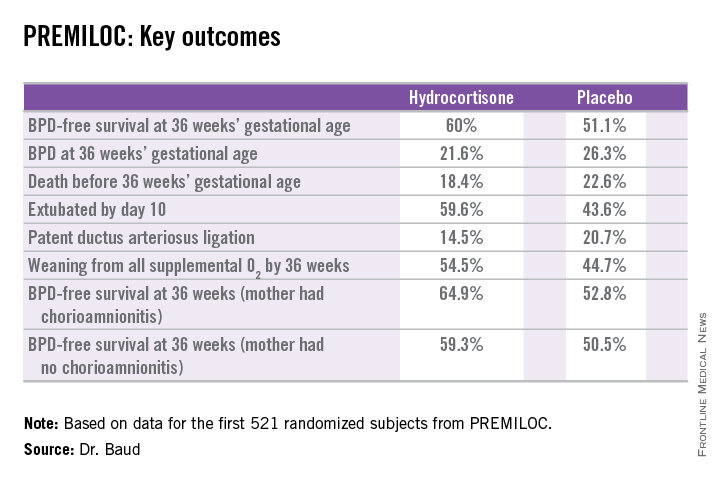

SAN DIEGO – Early prophylactic very-low-dose hydrocortisone improved survival free of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in extremely preterm neonates in a large French randomized trial.

The intervention also brought positive results on multiple secondary endpoints, including rates of extubation by day 10 and patent ductus arteriosus closure without resort to ligation, Dr. Olivier Baud reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

He presented the findings of PREMILOC, a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, 21-center French study. The study was halted by the data safety monitoring board for ethical reasons, based upon compelling evidence of superiority after scrutinizing results in the first 521 randomized subjects.

The primary outcome – survival free of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) at 36 weeks of gestational age – occurred in 60% of the hydrocortisone group, compared with 51% of placebo-treated controls, for an adjusted 48% increased likelihood of favorable outcome. The number-needed-to-treat was 11 patients, said Dr. Baud, professor of pediatrics and chief of the neonatal medicine unit at Robert Debré Hospital in Paris and Paris Diderot University.

The intervention involved administration of intravenous hydrocortisone sodium succinate for the first 10 postnatal days. The dose was 0.5 mg/kg/12 hours for 7 days followed by 0.5 mg/kg/24 hours for 3 days. Treatment began as soon as possible after birth and always within 24 hours. The total cumulative dose of hydrocortisone was 8.5 mg/kg. That’s 15-30 times less corticosteroid than employed in earlier studies of higher-dose dexamethasone, where gastrointestinal bleeding, intestinal perforation, and other serious adverse events were a major problem.

“This is the lowest hydrocortisone dose ever studied in a randomized controlled trial,” according to the neonatologist.

All study participants were born at 24-27 weeks’ gestational age. In order to minimize the risk of treatment-related serious adverse events, especially GI perforation – patients with intrauterine growth retardation or who were on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents were ineligible for the trial.

The rationale for the study, Dr. Baud explained, comes from the landmark work of Dr. Kristi L. Watterberg, professor of pediatrics at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, who has argued that early adrenal insufficiency in extremely small-for-gestational-age infants is linked to BPD, patent ductus arteriosus, persistent lung inflammation, and poor enteral nutrition. She introduced the concept that administration of very-low-dose corticosteroids at a dose comparable to normal endogenous steroid production could serve as a global therapy addressing these multiple health problems.

Two prior studies of low-dose hydrocortisone in extremely preterm babies were halted due to an increase in GI perforation, Dr. Baud noted, which is why the French investigators excluded neonates at increased risk for this complication.

In a prespecified PREMILOC subgroup analysis stratified by gestational age, the rate of survival free of BPD at 36 weeks among neonates born at 24-25 weeks was 33.7% with hydrocortisone, compared with 23.3% with placebo, for an adjusted 67% increased likelihood of a positive outcome with active treatment. In babies born at 26-27 weeks, the rates were 72.7% and 65.3%, respectively. On the other hand, hydrocortisone was associated with a highly significant 55% relative risk reduction for neonatal mortality in infants born at 26-27 weeks.

Post hoc analysis spotlighted several factors which were unexpectedly associated with differential impacts on outcome. For example, hydrocortisone achieved a significant benefit in terms of survival free of BPD at 36 weeks only in females, where the rates were 69.4% versus 53%, for an adjusted 2.25-fold increased rate. In males, the rate was 51.1% with hydrocortisone, compared with 49.7% in controls.

There were no differences between the hydrocortisone and placebo groups in rates of any serious adverse events, including GI perforation, necrotizing enterocolitis, air leaks, severe sepsis, or persistent pulmonary hypertension.

Dr. Baud said the next stage of the PREMILOC study will be to report 2-year outcomes; a greater than 90% follow-up rate is anticipated. Also, he and his coinvestigators are planning ancillary studies examining placental findings, the impact of pretreatment serum cortisol levels, thyroid function, and other issues.

“Our goal is to identify a targeted population that could strongly benefit from prophylactic hydrocortisone,” the neonatologist said.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, supported by INSERM and other French national research organizations.

SAN DIEGO – Early prophylactic very-low-dose hydrocortisone improved survival free of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in extremely preterm neonates in a large French randomized trial.

The intervention also brought positive results on multiple secondary endpoints, including rates of extubation by day 10 and patent ductus arteriosus closure without resort to ligation, Dr. Olivier Baud reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

He presented the findings of PREMILOC, a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, 21-center French study. The study was halted by the data safety monitoring board for ethical reasons, based upon compelling evidence of superiority after scrutinizing results in the first 521 randomized subjects.

The primary outcome – survival free of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) at 36 weeks of gestational age – occurred in 60% of the hydrocortisone group, compared with 51% of placebo-treated controls, for an adjusted 48% increased likelihood of favorable outcome. The number-needed-to-treat was 11 patients, said Dr. Baud, professor of pediatrics and chief of the neonatal medicine unit at Robert Debré Hospital in Paris and Paris Diderot University.

The intervention involved administration of intravenous hydrocortisone sodium succinate for the first 10 postnatal days. The dose was 0.5 mg/kg/12 hours for 7 days followed by 0.5 mg/kg/24 hours for 3 days. Treatment began as soon as possible after birth and always within 24 hours. The total cumulative dose of hydrocortisone was 8.5 mg/kg. That’s 15-30 times less corticosteroid than employed in earlier studies of higher-dose dexamethasone, where gastrointestinal bleeding, intestinal perforation, and other serious adverse events were a major problem.

“This is the lowest hydrocortisone dose ever studied in a randomized controlled trial,” according to the neonatologist.

All study participants were born at 24-27 weeks’ gestational age. In order to minimize the risk of treatment-related serious adverse events, especially GI perforation – patients with intrauterine growth retardation or who were on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents were ineligible for the trial.

The rationale for the study, Dr. Baud explained, comes from the landmark work of Dr. Kristi L. Watterberg, professor of pediatrics at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, who has argued that early adrenal insufficiency in extremely small-for-gestational-age infants is linked to BPD, patent ductus arteriosus, persistent lung inflammation, and poor enteral nutrition. She introduced the concept that administration of very-low-dose corticosteroids at a dose comparable to normal endogenous steroid production could serve as a global therapy addressing these multiple health problems.

Two prior studies of low-dose hydrocortisone in extremely preterm babies were halted due to an increase in GI perforation, Dr. Baud noted, which is why the French investigators excluded neonates at increased risk for this complication.

In a prespecified PREMILOC subgroup analysis stratified by gestational age, the rate of survival free of BPD at 36 weeks among neonates born at 24-25 weeks was 33.7% with hydrocortisone, compared with 23.3% with placebo, for an adjusted 67% increased likelihood of a positive outcome with active treatment. In babies born at 26-27 weeks, the rates were 72.7% and 65.3%, respectively. On the other hand, hydrocortisone was associated with a highly significant 55% relative risk reduction for neonatal mortality in infants born at 26-27 weeks.

Post hoc analysis spotlighted several factors which were unexpectedly associated with differential impacts on outcome. For example, hydrocortisone achieved a significant benefit in terms of survival free of BPD at 36 weeks only in females, where the rates were 69.4% versus 53%, for an adjusted 2.25-fold increased rate. In males, the rate was 51.1% with hydrocortisone, compared with 49.7% in controls.

There were no differences between the hydrocortisone and placebo groups in rates of any serious adverse events, including GI perforation, necrotizing enterocolitis, air leaks, severe sepsis, or persistent pulmonary hypertension.

Dr. Baud said the next stage of the PREMILOC study will be to report 2-year outcomes; a greater than 90% follow-up rate is anticipated. Also, he and his coinvestigators are planning ancillary studies examining placental findings, the impact of pretreatment serum cortisol levels, thyroid function, and other issues.

“Our goal is to identify a targeted population that could strongly benefit from prophylactic hydrocortisone,” the neonatologist said.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, supported by INSERM and other French national research organizations.

SAN DIEGO – Early prophylactic very-low-dose hydrocortisone improved survival free of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in extremely preterm neonates in a large French randomized trial.

The intervention also brought positive results on multiple secondary endpoints, including rates of extubation by day 10 and patent ductus arteriosus closure without resort to ligation, Dr. Olivier Baud reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

He presented the findings of PREMILOC, a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, 21-center French study. The study was halted by the data safety monitoring board for ethical reasons, based upon compelling evidence of superiority after scrutinizing results in the first 521 randomized subjects.

The primary outcome – survival free of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) at 36 weeks of gestational age – occurred in 60% of the hydrocortisone group, compared with 51% of placebo-treated controls, for an adjusted 48% increased likelihood of favorable outcome. The number-needed-to-treat was 11 patients, said Dr. Baud, professor of pediatrics and chief of the neonatal medicine unit at Robert Debré Hospital in Paris and Paris Diderot University.

The intervention involved administration of intravenous hydrocortisone sodium succinate for the first 10 postnatal days. The dose was 0.5 mg/kg/12 hours for 7 days followed by 0.5 mg/kg/24 hours for 3 days. Treatment began as soon as possible after birth and always within 24 hours. The total cumulative dose of hydrocortisone was 8.5 mg/kg. That’s 15-30 times less corticosteroid than employed in earlier studies of higher-dose dexamethasone, where gastrointestinal bleeding, intestinal perforation, and other serious adverse events were a major problem.

“This is the lowest hydrocortisone dose ever studied in a randomized controlled trial,” according to the neonatologist.

All study participants were born at 24-27 weeks’ gestational age. In order to minimize the risk of treatment-related serious adverse events, especially GI perforation – patients with intrauterine growth retardation or who were on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents were ineligible for the trial.

The rationale for the study, Dr. Baud explained, comes from the landmark work of Dr. Kristi L. Watterberg, professor of pediatrics at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, who has argued that early adrenal insufficiency in extremely small-for-gestational-age infants is linked to BPD, patent ductus arteriosus, persistent lung inflammation, and poor enteral nutrition. She introduced the concept that administration of very-low-dose corticosteroids at a dose comparable to normal endogenous steroid production could serve as a global therapy addressing these multiple health problems.

Two prior studies of low-dose hydrocortisone in extremely preterm babies were halted due to an increase in GI perforation, Dr. Baud noted, which is why the French investigators excluded neonates at increased risk for this complication.

In a prespecified PREMILOC subgroup analysis stratified by gestational age, the rate of survival free of BPD at 36 weeks among neonates born at 24-25 weeks was 33.7% with hydrocortisone, compared with 23.3% with placebo, for an adjusted 67% increased likelihood of a positive outcome with active treatment. In babies born at 26-27 weeks, the rates were 72.7% and 65.3%, respectively. On the other hand, hydrocortisone was associated with a highly significant 55% relative risk reduction for neonatal mortality in infants born at 26-27 weeks.

Post hoc analysis spotlighted several factors which were unexpectedly associated with differential impacts on outcome. For example, hydrocortisone achieved a significant benefit in terms of survival free of BPD at 36 weeks only in females, where the rates were 69.4% versus 53%, for an adjusted 2.25-fold increased rate. In males, the rate was 51.1% with hydrocortisone, compared with 49.7% in controls.

There were no differences between the hydrocortisone and placebo groups in rates of any serious adverse events, including GI perforation, necrotizing enterocolitis, air leaks, severe sepsis, or persistent pulmonary hypertension.

Dr. Baud said the next stage of the PREMILOC study will be to report 2-year outcomes; a greater than 90% follow-up rate is anticipated. Also, he and his coinvestigators are planning ancillary studies examining placental findings, the impact of pretreatment serum cortisol levels, thyroid function, and other issues.

“Our goal is to identify a targeted population that could strongly benefit from prophylactic hydrocortisone,” the neonatologist said.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, supported by INSERM and other French national research organizations.

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: In extremely premature neonates, prophylactic very-low-dose hydrocortisone improved the likelihood of survival free of bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks’ gestational age by roughly 50%.

Major finding: The number needed to treat to achieve one additional survival without bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks’ gestational age was 11.

Data source: This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter French study involving 521 patients born at 24-27 weeks’ gestational age.

Disclosures: The PREMILOC study was supported by INSERM and other French scientific research organizations. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

PAS: Screen for postpartum depression during infant hospitalization

SAN DIEGO – Infant hospitalizations provide an untapped opportunity to screen for maternal postpartum depression, according to Dr. Margaret Trost.

“A hospital setting places a mother at the bedside with her infant for much of the day, which may provide time for screening and counseling,” noted Dr. Trost, a pediatric hospitalist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

Dr. Trost presented what she believes is the first-ever formal study of screening for maternal postpartum depression during infant hospitalization. The results demonstrated that this approach is readily accomplished and captures large numbers of previously unscreened mothers. Moreover, women who initially screened positive and followed staff advice to discuss postpartum depression with their own physician or a recommended mental health referral resource had lower postpartum depression scores upon repeat screening at 3 and/or 6 months of follow-up.

Maternal postpartum depression is a depressive episode occurring within 1 year of childbirth. It affects an estimated 10% of mothers, with markedly higher rates in high-risk populations, including teenage or low-income mothers. In addition to the harmful effects on the mother, postpartum depression can harm an infant’s cognitive development and contribute to behavioral and emotional problems, Dr. Trost noted.

She reported on 310 mothers screened for postpartum depression 24-48 hours after their infant was admitted to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. All infants had to be at least 2 weeks of age, because maternal depressive symptoms within the first 2 weeks after childbirth are classified as “baby blues” rather than postpartum depression. Study eligibility was restricted to the mothers of infants who were not admitted to an intensive care unit.

The screening tool utilized in the study was the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS), a validated 10-question instrument that probes a mother’s feelings, including energy, mood, and suicidality, within the past 7 days. A score of 10 or more out of a possible 30 identifies an at-risk mother.

All participants also were assessed using the Maternal-Infant Bonding Tool. In addition, information was collected on maternal demographics, social isolation, and history of previous psychiatric illness, as well as the infants’ comorbid conditions.

Based upon EPDS results, 28% of the mothers were deemed at risk for postpartum depression. They received counseling from both a physician and a social worker, got a handout on local and national mental health resources, and were advised to discuss their screening results with their personal physician or someone on the mental health referral list.

Of note, a mere 18% of study participants reported that they had been screened for postpartum depression since their most recent childbirth, underscoring the point that this important task doesn’t consistently get done in the outpatient setting, Dr. Trost said.

In this study, the higher a mother’s score on the EPDS, the worse her maternal-infant bonding score.

In a logistic regression analysis, Hispanic mothers were significantly less likely to have postpartum depression symptoms than non-Hispanics, with an odds ratio of 0.46.

Several risk factors for postpartum depression were identified in the study. Women who reported having low or no social support were 3.5 times more likely to have an at-risk EPDS score than those with self-described good social support. Those with a history of psychiatric illness were at 5.1-fold increased risk.

Those maternal risk factors for postpartum depression were consistent with the results of previous studies. A novel finding in this study was the identification of an infant risk factor: neurodevelopmental disorders. The 22 mothers of infants with a neurodevelopmental abnormality – cerebral palsy, mental retardation, hydrocephalus, seizures, a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, or craniosynostosis – had a 3.4-fold increased risk of a positive screen for postpartum depression. Moreover, in a multivariate logistic regression analysis controlled for race, social support, and history of psychiatric diagnosis, having an infant with a neurodevelopmental problem still remained associated with a threefold increased risk of maternal postpartum depression.

Attempts to follow up with all study participants by phone 3 and 6 months later met with only limited success. Of 87 mothers who screened positive by the EPDS, 21 completed follow-up phone interviews involving repeat screening, at which point 11 women still screened positive while 10 screened negative.

Follow-up interviews also were completed with 76 of the 223 mothers who initially screened negative. Of note, 6 women, or 8%, screened positive at follow-up.

Among the 21 mothers with an at-risk EPDS score at the initial screening during their infant’s hospitalization, 8 (38%) women took the advice to have a follow-up discussion about their risk for postpartum depression. This was typically with their personal physician, presumably because they felt more comfortable talking about the problem with a professional with whom there was already an established relationship, Dr. Trost said. On follow-up EPDS screening, those women showed a significant reduction from their baseline scores down to levels below the threshold for concern. In contrast, the change over time in EPDS scores in the 13 women who didn’t seek help was unimpressive, although the small sample size – just 21 mothers – must be noted, she said.

One audience member suggested that the intervention part of the program would be much more effective – and the follow-up rate higher – if the mental health referral resources could be incorporated into the initial infant hospitalization. Dr. Trost agreed, adding that she is looking into bringing in on-site small-group sessions.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

SAN DIEGO – Infant hospitalizations provide an untapped opportunity to screen for maternal postpartum depression, according to Dr. Margaret Trost.

“A hospital setting places a mother at the bedside with her infant for much of the day, which may provide time for screening and counseling,” noted Dr. Trost, a pediatric hospitalist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

Dr. Trost presented what she believes is the first-ever formal study of screening for maternal postpartum depression during infant hospitalization. The results demonstrated that this approach is readily accomplished and captures large numbers of previously unscreened mothers. Moreover, women who initially screened positive and followed staff advice to discuss postpartum depression with their own physician or a recommended mental health referral resource had lower postpartum depression scores upon repeat screening at 3 and/or 6 months of follow-up.

Maternal postpartum depression is a depressive episode occurring within 1 year of childbirth. It affects an estimated 10% of mothers, with markedly higher rates in high-risk populations, including teenage or low-income mothers. In addition to the harmful effects on the mother, postpartum depression can harm an infant’s cognitive development and contribute to behavioral and emotional problems, Dr. Trost noted.

She reported on 310 mothers screened for postpartum depression 24-48 hours after their infant was admitted to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. All infants had to be at least 2 weeks of age, because maternal depressive symptoms within the first 2 weeks after childbirth are classified as “baby blues” rather than postpartum depression. Study eligibility was restricted to the mothers of infants who were not admitted to an intensive care unit.

The screening tool utilized in the study was the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS), a validated 10-question instrument that probes a mother’s feelings, including energy, mood, and suicidality, within the past 7 days. A score of 10 or more out of a possible 30 identifies an at-risk mother.

All participants also were assessed using the Maternal-Infant Bonding Tool. In addition, information was collected on maternal demographics, social isolation, and history of previous psychiatric illness, as well as the infants’ comorbid conditions.

Based upon EPDS results, 28% of the mothers were deemed at risk for postpartum depression. They received counseling from both a physician and a social worker, got a handout on local and national mental health resources, and were advised to discuss their screening results with their personal physician or someone on the mental health referral list.

Of note, a mere 18% of study participants reported that they had been screened for postpartum depression since their most recent childbirth, underscoring the point that this important task doesn’t consistently get done in the outpatient setting, Dr. Trost said.

In this study, the higher a mother’s score on the EPDS, the worse her maternal-infant bonding score.

In a logistic regression analysis, Hispanic mothers were significantly less likely to have postpartum depression symptoms than non-Hispanics, with an odds ratio of 0.46.

Several risk factors for postpartum depression were identified in the study. Women who reported having low or no social support were 3.5 times more likely to have an at-risk EPDS score than those with self-described good social support. Those with a history of psychiatric illness were at 5.1-fold increased risk.

Those maternal risk factors for postpartum depression were consistent with the results of previous studies. A novel finding in this study was the identification of an infant risk factor: neurodevelopmental disorders. The 22 mothers of infants with a neurodevelopmental abnormality – cerebral palsy, mental retardation, hydrocephalus, seizures, a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, or craniosynostosis – had a 3.4-fold increased risk of a positive screen for postpartum depression. Moreover, in a multivariate logistic regression analysis controlled for race, social support, and history of psychiatric diagnosis, having an infant with a neurodevelopmental problem still remained associated with a threefold increased risk of maternal postpartum depression.

Attempts to follow up with all study participants by phone 3 and 6 months later met with only limited success. Of 87 mothers who screened positive by the EPDS, 21 completed follow-up phone interviews involving repeat screening, at which point 11 women still screened positive while 10 screened negative.

Follow-up interviews also were completed with 76 of the 223 mothers who initially screened negative. Of note, 6 women, or 8%, screened positive at follow-up.

Among the 21 mothers with an at-risk EPDS score at the initial screening during their infant’s hospitalization, 8 (38%) women took the advice to have a follow-up discussion about their risk for postpartum depression. This was typically with their personal physician, presumably because they felt more comfortable talking about the problem with a professional with whom there was already an established relationship, Dr. Trost said. On follow-up EPDS screening, those women showed a significant reduction from their baseline scores down to levels below the threshold for concern. In contrast, the change over time in EPDS scores in the 13 women who didn’t seek help was unimpressive, although the small sample size – just 21 mothers – must be noted, she said.

One audience member suggested that the intervention part of the program would be much more effective – and the follow-up rate higher – if the mental health referral resources could be incorporated into the initial infant hospitalization. Dr. Trost agreed, adding that she is looking into bringing in on-site small-group sessions.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

SAN DIEGO – Infant hospitalizations provide an untapped opportunity to screen for maternal postpartum depression, according to Dr. Margaret Trost.

“A hospital setting places a mother at the bedside with her infant for much of the day, which may provide time for screening and counseling,” noted Dr. Trost, a pediatric hospitalist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

Dr. Trost presented what she believes is the first-ever formal study of screening for maternal postpartum depression during infant hospitalization. The results demonstrated that this approach is readily accomplished and captures large numbers of previously unscreened mothers. Moreover, women who initially screened positive and followed staff advice to discuss postpartum depression with their own physician or a recommended mental health referral resource had lower postpartum depression scores upon repeat screening at 3 and/or 6 months of follow-up.

Maternal postpartum depression is a depressive episode occurring within 1 year of childbirth. It affects an estimated 10% of mothers, with markedly higher rates in high-risk populations, including teenage or low-income mothers. In addition to the harmful effects on the mother, postpartum depression can harm an infant’s cognitive development and contribute to behavioral and emotional problems, Dr. Trost noted.

She reported on 310 mothers screened for postpartum depression 24-48 hours after their infant was admitted to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. All infants had to be at least 2 weeks of age, because maternal depressive symptoms within the first 2 weeks after childbirth are classified as “baby blues” rather than postpartum depression. Study eligibility was restricted to the mothers of infants who were not admitted to an intensive care unit.

The screening tool utilized in the study was the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS), a validated 10-question instrument that probes a mother’s feelings, including energy, mood, and suicidality, within the past 7 days. A score of 10 or more out of a possible 30 identifies an at-risk mother.

All participants also were assessed using the Maternal-Infant Bonding Tool. In addition, information was collected on maternal demographics, social isolation, and history of previous psychiatric illness, as well as the infants’ comorbid conditions.

Based upon EPDS results, 28% of the mothers were deemed at risk for postpartum depression. They received counseling from both a physician and a social worker, got a handout on local and national mental health resources, and were advised to discuss their screening results with their personal physician or someone on the mental health referral list.

Of note, a mere 18% of study participants reported that they had been screened for postpartum depression since their most recent childbirth, underscoring the point that this important task doesn’t consistently get done in the outpatient setting, Dr. Trost said.

In this study, the higher a mother’s score on the EPDS, the worse her maternal-infant bonding score.

In a logistic regression analysis, Hispanic mothers were significantly less likely to have postpartum depression symptoms than non-Hispanics, with an odds ratio of 0.46.

Several risk factors for postpartum depression were identified in the study. Women who reported having low or no social support were 3.5 times more likely to have an at-risk EPDS score than those with self-described good social support. Those with a history of psychiatric illness were at 5.1-fold increased risk.

Those maternal risk factors for postpartum depression were consistent with the results of previous studies. A novel finding in this study was the identification of an infant risk factor: neurodevelopmental disorders. The 22 mothers of infants with a neurodevelopmental abnormality – cerebral palsy, mental retardation, hydrocephalus, seizures, a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, or craniosynostosis – had a 3.4-fold increased risk of a positive screen for postpartum depression. Moreover, in a multivariate logistic regression analysis controlled for race, social support, and history of psychiatric diagnosis, having an infant with a neurodevelopmental problem still remained associated with a threefold increased risk of maternal postpartum depression.

Attempts to follow up with all study participants by phone 3 and 6 months later met with only limited success. Of 87 mothers who screened positive by the EPDS, 21 completed follow-up phone interviews involving repeat screening, at which point 11 women still screened positive while 10 screened negative.

Follow-up interviews also were completed with 76 of the 223 mothers who initially screened negative. Of note, 6 women, or 8%, screened positive at follow-up.

Among the 21 mothers with an at-risk EPDS score at the initial screening during their infant’s hospitalization, 8 (38%) women took the advice to have a follow-up discussion about their risk for postpartum depression. This was typically with their personal physician, presumably because they felt more comfortable talking about the problem with a professional with whom there was already an established relationship, Dr. Trost said. On follow-up EPDS screening, those women showed a significant reduction from their baseline scores down to levels below the threshold for concern. In contrast, the change over time in EPDS scores in the 13 women who didn’t seek help was unimpressive, although the small sample size – just 21 mothers – must be noted, she said.

One audience member suggested that the intervention part of the program would be much more effective – and the follow-up rate higher – if the mental health referral resources could be incorporated into the initial infant hospitalization. Dr. Trost agreed, adding that she is looking into bringing in on-site small-group sessions.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Screening for maternal postpartum depression during an infant’s hospitalization captures large numbers of previously unscreened women.

Major finding: Twenty-eight percent of women screened during their infant’s hospital admission were deemed at risk for postpartum depression.

Data source: The study included 310 mothers, only 18% of whom had been screened for postpartum depression during their infant’s routine office visits as guidelines recommend.

Disclosures: This study was conducted free of commercial support. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

PAS: Screen for postpartum depression during infant hospitalization

SAN DIEGO – Infant hospitalizations provide an untapped opportunity to screen for maternal postpartum depression, according to Dr. Margaret Trost.

“A hospital setting places a mother at the bedside with her infant for much of the day, which may provide time for screening and counseling,” noted Dr. Trost, a pediatric hospitalist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends screening mothers for postpartum depression during an infant’s routine office visits. Realistically, that often doesn’t happen, because of time constraints, because of physician discomfort with diagnosing the illness, or because an infant with prolonged hospitalization for severe illness misses the scheduled office visits, she said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Dr. Trost presented what she believes is the first-ever formal study of screening for maternal postpartum depression during infant hospitalization. The results demonstrated that this approach is readily accomplished and captures large numbers of previously unscreened mothers. Moreover, women who initially screened positive and followed staff advice to discuss postpartum depression with their own physician or a recommended mental health referral resource had lower postpartum depression scores upon repeat screening at 3 and/or 6 months of follow-up.

Maternal postpartum depression is a depressive episode occurring within 1 year of childbirth. It affects an estimated 10% of mothers, with markedly higher rates in high-risk populations, including teenage or low-income mothers. In addition to the harmful effects on the mother, postpartum depression can harm an infant’s cognitive development and contribute to behavioral and emotional problems, Dr. Trost noted.

She reported on 310 mothers screened for postpartum depression 24-48 hours after their infant was admitted to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. All infants had to be at least 2 weeks of age, because maternal depressive symptoms within the first 2 weeks after childbirth are classified as “baby blues” rather than postpartum depression. Study eligibility was restricted to the mothers of infants who were not admitted to an intensive care unit.

The screening tool utilized in the study was the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS), a validated 10-question instrument that probes a mother’s feelings, including energy, mood, and suicidality, within the past 7 days. A score of 10 or more out of a possible 30 identifies an at-risk mother.

All participants also were assessed using the Maternal-Infant Bonding Tool. In addition, information was collected on maternal demographics, social isolation, and history of previous psychiatric illness, as well as the infants’ comorbid conditions.

Based upon EPDS results, 28% of the mothers were deemed at risk for postpartum depression. They received counseling from both a physician and a social worker, got a handout on local and national mental health resources, and were advised to discuss their screening results with their personal physician or someone on the mental health referral list.

Of note, a mere 18% of study participants reported that they had been screened for postpartum depression since their most recent childbirth, underscoring the point that this important task doesn’t consistently get done in the outpatient setting, Dr. Trost said.

In this study, the higher a mother’s score on the EPDS, the worse her maternal-infant bonding score.

In a logistic regression analysis, Hispanic mothers were significantly less likely to have postpartum depression symptoms than non-Hispanics, with an odds ratio of 0.46.

Several risk factors for postpartum depression were identified in the study. Women who reported having low or no social support were 3.5 times more likely to have an at-risk EPDS score than those with self-described good social support. Those with a history of psychiatric illness were at 5.1-fold increased risk.

Those maternal risk factors for postpartum depression were consistent with the results of previous studies. A novel finding in this study was the identification of an infant risk factor: neurodevelopmental disorders. The 22 mothers of infants with a neurodevelopmental abnormality – cerebral palsy, mental retardation, hydrocephalus, seizures, a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, or craniosynostosis – had a 3.4-fold increased risk of a positive screen for postpartum depression. Moreover, in a multivariate logistic regression analysis controlled for race, social support, and history of psychiatric diagnosis, having an infant with a neurodevelopmental problem still remained associated with a threefold increased risk of maternal postpartum depression.

Attempts to follow up with all study participants by phone 3 and 6 months later met with only limited success. Of 87 mothers who screened positive by the EPDS, 21 completed follow-up phone interviews involving repeat screening, at which point 11 women still screened positive while 10 screened negative.

Follow-up interviews also were completed with 76 of the 223 mothers who initially screened negative. Of note, 6 women, or 8%, screened positive at follow-up.

Among the 21 mothers with an at-risk EPDS score at the initial screening during their infant’s hospitalization, 8 (38%) women took the advice to have a follow-up discussion about their risk for postpartum depression. This was typically with their personal physician, presumably because they felt more comfortable talking about the problem with a professional with whom there was already an established relationship, Dr. Trost said. On follow-up EPDS screening, those women showed a significant reduction from their baseline scores down to levels below the threshold for concern. In contrast, the change over time in EPDS scores in the 13 women who didn’t seek help was unimpressive, although the small sample size – just 21 mothers – must be noted, she said.

One audience member suggested that the intervention part of the program would be much more effective – and the follow-up rate higher – if the mental health referral resources could be incorporated into the initial infant hospitalization. Dr. Trost agreed, adding that she is looking into bringing in on-site small-group sessions.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

SAN DIEGO – Infant hospitalizations provide an untapped opportunity to screen for maternal postpartum depression, according to Dr. Margaret Trost.

“A hospital setting places a mother at the bedside with her infant for much of the day, which may provide time for screening and counseling,” noted Dr. Trost, a pediatric hospitalist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends screening mothers for postpartum depression during an infant’s routine office visits. Realistically, that often doesn’t happen, because of time constraints, because of physician discomfort with diagnosing the illness, or because an infant with prolonged hospitalization for severe illness misses the scheduled office visits, she said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Dr. Trost presented what she believes is the first-ever formal study of screening for maternal postpartum depression during infant hospitalization. The results demonstrated that this approach is readily accomplished and captures large numbers of previously unscreened mothers. Moreover, women who initially screened positive and followed staff advice to discuss postpartum depression with their own physician or a recommended mental health referral resource had lower postpartum depression scores upon repeat screening at 3 and/or 6 months of follow-up.

Maternal postpartum depression is a depressive episode occurring within 1 year of childbirth. It affects an estimated 10% of mothers, with markedly higher rates in high-risk populations, including teenage or low-income mothers. In addition to the harmful effects on the mother, postpartum depression can harm an infant’s cognitive development and contribute to behavioral and emotional problems, Dr. Trost noted.

She reported on 310 mothers screened for postpartum depression 24-48 hours after their infant was admitted to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. All infants had to be at least 2 weeks of age, because maternal depressive symptoms within the first 2 weeks after childbirth are classified as “baby blues” rather than postpartum depression. Study eligibility was restricted to the mothers of infants who were not admitted to an intensive care unit.

The screening tool utilized in the study was the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS), a validated 10-question instrument that probes a mother’s feelings, including energy, mood, and suicidality, within the past 7 days. A score of 10 or more out of a possible 30 identifies an at-risk mother.

All participants also were assessed using the Maternal-Infant Bonding Tool. In addition, information was collected on maternal demographics, social isolation, and history of previous psychiatric illness, as well as the infants’ comorbid conditions.

Based upon EPDS results, 28% of the mothers were deemed at risk for postpartum depression. They received counseling from both a physician and a social worker, got a handout on local and national mental health resources, and were advised to discuss their screening results with their personal physician or someone on the mental health referral list.

Of note, a mere 18% of study participants reported that they had been screened for postpartum depression since their most recent childbirth, underscoring the point that this important task doesn’t consistently get done in the outpatient setting, Dr. Trost said.

In this study, the higher a mother’s score on the EPDS, the worse her maternal-infant bonding score.

In a logistic regression analysis, Hispanic mothers were significantly less likely to have postpartum depression symptoms than non-Hispanics, with an odds ratio of 0.46.

Several risk factors for postpartum depression were identified in the study. Women who reported having low or no social support were 3.5 times more likely to have an at-risk EPDS score than those with self-described good social support. Those with a history of psychiatric illness were at 5.1-fold increased risk.

Those maternal risk factors for postpartum depression were consistent with the results of previous studies. A novel finding in this study was the identification of an infant risk factor: neurodevelopmental disorders. The 22 mothers of infants with a neurodevelopmental abnormality – cerebral palsy, mental retardation, hydrocephalus, seizures, a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, or craniosynostosis – had a 3.4-fold increased risk of a positive screen for postpartum depression. Moreover, in a multivariate logistic regression analysis controlled for race, social support, and history of psychiatric diagnosis, having an infant with a neurodevelopmental problem still remained associated with a threefold increased risk of maternal postpartum depression.

Attempts to follow up with all study participants by phone 3 and 6 months later met with only limited success. Of 87 mothers who screened positive by the EPDS, 21 completed follow-up phone interviews involving repeat screening, at which point 11 women still screened positive while 10 screened negative.

Follow-up interviews also were completed with 76 of the 223 mothers who initially screened negative. Of note, 6 women, or 8%, screened positive at follow-up.

Among the 21 mothers with an at-risk EPDS score at the initial screening during their infant’s hospitalization, 8 (38%) women took the advice to have a follow-up discussion about their risk for postpartum depression. This was typically with their personal physician, presumably because they felt more comfortable talking about the problem with a professional with whom there was already an established relationship, Dr. Trost said. On follow-up EPDS screening, those women showed a significant reduction from their baseline scores down to levels below the threshold for concern. In contrast, the change over time in EPDS scores in the 13 women who didn’t seek help was unimpressive, although the small sample size – just 21 mothers – must be noted, she said.

One audience member suggested that the intervention part of the program would be much more effective – and the follow-up rate higher – if the mental health referral resources could be incorporated into the initial infant hospitalization. Dr. Trost agreed, adding that she is looking into bringing in on-site small-group sessions.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

SAN DIEGO – Infant hospitalizations provide an untapped opportunity to screen for maternal postpartum depression, according to Dr. Margaret Trost.

“A hospital setting places a mother at the bedside with her infant for much of the day, which may provide time for screening and counseling,” noted Dr. Trost, a pediatric hospitalist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends screening mothers for postpartum depression during an infant’s routine office visits. Realistically, that often doesn’t happen, because of time constraints, because of physician discomfort with diagnosing the illness, or because an infant with prolonged hospitalization for severe illness misses the scheduled office visits, she said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Dr. Trost presented what she believes is the first-ever formal study of screening for maternal postpartum depression during infant hospitalization. The results demonstrated that this approach is readily accomplished and captures large numbers of previously unscreened mothers. Moreover, women who initially screened positive and followed staff advice to discuss postpartum depression with their own physician or a recommended mental health referral resource had lower postpartum depression scores upon repeat screening at 3 and/or 6 months of follow-up.

Maternal postpartum depression is a depressive episode occurring within 1 year of childbirth. It affects an estimated 10% of mothers, with markedly higher rates in high-risk populations, including teenage or low-income mothers. In addition to the harmful effects on the mother, postpartum depression can harm an infant’s cognitive development and contribute to behavioral and emotional problems, Dr. Trost noted.

She reported on 310 mothers screened for postpartum depression 24-48 hours after their infant was admitted to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. All infants had to be at least 2 weeks of age, because maternal depressive symptoms within the first 2 weeks after childbirth are classified as “baby blues” rather than postpartum depression. Study eligibility was restricted to the mothers of infants who were not admitted to an intensive care unit.

The screening tool utilized in the study was the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS), a validated 10-question instrument that probes a mother’s feelings, including energy, mood, and suicidality, within the past 7 days. A score of 10 or more out of a possible 30 identifies an at-risk mother.

All participants also were assessed using the Maternal-Infant Bonding Tool. In addition, information was collected on maternal demographics, social isolation, and history of previous psychiatric illness, as well as the infants’ comorbid conditions.

Based upon EPDS results, 28% of the mothers were deemed at risk for postpartum depression. They received counseling from both a physician and a social worker, got a handout on local and national mental health resources, and were advised to discuss their screening results with their personal physician or someone on the mental health referral list.

Of note, a mere 18% of study participants reported that they had been screened for postpartum depression since their most recent childbirth, underscoring the point that this important task doesn’t consistently get done in the outpatient setting, Dr. Trost said.

In this study, the higher a mother’s score on the EPDS, the worse her maternal-infant bonding score.

In a logistic regression analysis, Hispanic mothers were significantly less likely to have postpartum depression symptoms than non-Hispanics, with an odds ratio of 0.46.

Several risk factors for postpartum depression were identified in the study. Women who reported having low or no social support were 3.5 times more likely to have an at-risk EPDS score than those with self-described good social support. Those with a history of psychiatric illness were at 5.1-fold increased risk.

Those maternal risk factors for postpartum depression were consistent with the results of previous studies. A novel finding in this study was the identification of an infant risk factor: neurodevelopmental disorders. The 22 mothers of infants with a neurodevelopmental abnormality – cerebral palsy, mental retardation, hydrocephalus, seizures, a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, or craniosynostosis – had a 3.4-fold increased risk of a positive screen for postpartum depression. Moreover, in a multivariate logistic regression analysis controlled for race, social support, and history of psychiatric diagnosis, having an infant with a neurodevelopmental problem still remained associated with a threefold increased risk of maternal postpartum depression.

Attempts to follow up with all study participants by phone 3 and 6 months later met with only limited success. Of 87 mothers who screened positive by the EPDS, 21 completed follow-up phone interviews involving repeat screening, at which point 11 women still screened positive while 10 screened negative.

Follow-up interviews also were completed with 76 of the 223 mothers who initially screened negative. Of note, 6 women, or 8%, screened positive at follow-up.

Among the 21 mothers with an at-risk EPDS score at the initial screening during their infant’s hospitalization, 8 (38%) women took the advice to have a follow-up discussion about their risk for postpartum depression. This was typically with their personal physician, presumably because they felt more comfortable talking about the problem with a professional with whom there was already an established relationship, Dr. Trost said. On follow-up EPDS screening, those women showed a significant reduction from their baseline scores down to levels below the threshold for concern. In contrast, the change over time in EPDS scores in the 13 women who didn’t seek help was unimpressive, although the small sample size – just 21 mothers – must be noted, she said.

One audience member suggested that the intervention part of the program would be much more effective – and the follow-up rate higher – if the mental health referral resources could be incorporated into the initial infant hospitalization. Dr. Trost agreed, adding that she is looking into bringing in on-site small-group sessions.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Screening for maternal postpartum depression during an infant’s hospitalization captures large numbers of previously unscreened women.

Major finding: Twenty-eight percent of women screened during their infant’s hospital admission were deemed at risk for postpartum depression.

Data source: The study included 310 mothers, only 18% of whom had been screened for postpartum depression during their infant’s routine office visits as guidelines recommend.

Disclosures: This study was conducted free of commercial support. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

PAS: Intervention eases transition from pediatric to adult care

SAN DIEGO – A dedicated care coordination intervention had a positive impact on facilitating the transition from pediatric to adult care among youth with special health care needs, a single-center randomized trial showed.

In an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, Dr. Lisa K. Tuchman said that coordination interventions in the existing literature have had mixed results. The current study is unique, she said, because it focuses on urban-based, publicly insured youth aged 16-22 years with special health care needs. “Other studies focus primarily on either pediatric or adult patients, not this in-between age group who is very vulnerable to dropping out of care,” explained Dr. Tuchman of the division of adolescent and young adult medicine at Children’s National Health System, Washington.

“Young adulthood is a time of many transitions; in this study we are focusing on transition between the pediatric and adult health care system – or when youth ‘age out’ of pediatric primary care and need to establish a new adult-oriented medical home – often in a different health system. This gap in care is known as a high-risk time for all youth, but especially for those youth with complex chronic conditions who may have adherence challenges, are navigating taking on more responsibility for their medical care, and often have a high rate of emergency department usage without a stable medical home.”

The current study also serves as a proof-of-effectiveness study. The health care transition recommendations published in Pediatrics in July 2011 are based on expert consensus, as evidence and data have been slow to evolve in this area (Pediatrics 2011;128:182-200). According to Dr. Tuchman, the current study is the first to demonstrate that these recommended guidelines improve quality and perception of care coordination, compared with a control group.

She and her colleagues recruited 210 patients aged 16-22 years from Children’s National Health System and randomly assigned them to a health care transition care coordination intervention (n = 105) or to a control group (n = 105).

The transition care coordination intervention consisted of implementing the Six Core Elements of Health Care Transition 2.0: transition policy, tracking and monitoring, transition readiness, planning, transfer of care, and completion. The last steps include communicating with the adult practice prior to planned transfer, confirming completion of transfer, and offering consultation assistance as needed.

The control group underwent usual care.

At baseline, and at 6 and 12 months, patients in both groups completed the Patient Assessment of Care for Chronic Conditions (PACIC), which assesses five domains (patient activation, delivery system design, goal setting, problem solving, and coordination/follow-up), as well as the Client Perceptions of Coordination Questionnaire (CPCQ), which assesses perception of patient-centered care and care coordination.

The study participants also completed a self-rating Likert scale (ranging from 1 to 10), a measurement of how ready they feel to transfer to adult care.

Dr. Tuchman reported that there were no statistically significant differences in PACIC, CPCQ, or readiness scores between the two groups at baseline. At 6 months, however, patients in the care coordination intervention group, compared with their counterparts in the control group, rated the quality of their chronic illness higher (P = .065) and reported receiving less conflicting advice from care providers (P = .018).

At 12 months, patients in the care coordination intervention group rated the following PACIC domains higher, compared with those in the control group: patient activation (P = .015), goal setting (P = .034), problem solving (P = .009), and coordination/follow-up (P = .016). Patients in the care coordination intervention group also reported more often receiving services they thought they needed (P = .03), were less confused about the role of providers (P = .012), and reported having more frequent discussions with providers about future care (P = .05).

The researchers observed no differences between the two groups in self-rating of transition readiness throughout the study period.

“[It was] surprising that this perceived higher quality care coordination and quality of care did not change perception of readiness to transfer from pediatrics to adult care,” Dr. Tuchman said. “This likely means that readiness is difficult to measure, and not related to care quality.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including the fact it “was a predominately African American, urban, publicly insured population of adolescents with special health care needs, and therefore may not be generalizable to other populations. But [it’s] still very important as Washington, D.C., has the fourth highest rate of unmet transition needs nationally.”

Maternal and Child Health, a bureau of the Department of Health and Human Services’ Health Resources and Services Administration, funded the study. Dr. Tuchman reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

This article was updated 4/30/2015.

SAN DIEGO – A dedicated care coordination intervention had a positive impact on facilitating the transition from pediatric to adult care among youth with special health care needs, a single-center randomized trial showed.

In an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, Dr. Lisa K. Tuchman said that coordination interventions in the existing literature have had mixed results. The current study is unique, she said, because it focuses on urban-based, publicly insured youth aged 16-22 years with special health care needs. “Other studies focus primarily on either pediatric or adult patients, not this in-between age group who is very vulnerable to dropping out of care,” explained Dr. Tuchman of the division of adolescent and young adult medicine at Children’s National Health System, Washington.

“Young adulthood is a time of many transitions; in this study we are focusing on transition between the pediatric and adult health care system – or when youth ‘age out’ of pediatric primary care and need to establish a new adult-oriented medical home – often in a different health system. This gap in care is known as a high-risk time for all youth, but especially for those youth with complex chronic conditions who may have adherence challenges, are navigating taking on more responsibility for their medical care, and often have a high rate of emergency department usage without a stable medical home.”

The current study also serves as a proof-of-effectiveness study. The health care transition recommendations published in Pediatrics in July 2011 are based on expert consensus, as evidence and data have been slow to evolve in this area (Pediatrics 2011;128:182-200). According to Dr. Tuchman, the current study is the first to demonstrate that these recommended guidelines improve quality and perception of care coordination, compared with a control group.

She and her colleagues recruited 210 patients aged 16-22 years from Children’s National Health System and randomly assigned them to a health care transition care coordination intervention (n = 105) or to a control group (n = 105).

The transition care coordination intervention consisted of implementing the Six Core Elements of Health Care Transition 2.0: transition policy, tracking and monitoring, transition readiness, planning, transfer of care, and completion. The last steps include communicating with the adult practice prior to planned transfer, confirming completion of transfer, and offering consultation assistance as needed.

The control group underwent usual care.

At baseline, and at 6 and 12 months, patients in both groups completed the Patient Assessment of Care for Chronic Conditions (PACIC), which assesses five domains (patient activation, delivery system design, goal setting, problem solving, and coordination/follow-up), as well as the Client Perceptions of Coordination Questionnaire (CPCQ), which assesses perception of patient-centered care and care coordination.

The study participants also completed a self-rating Likert scale (ranging from 1 to 10), a measurement of how ready they feel to transfer to adult care.

Dr. Tuchman reported that there were no statistically significant differences in PACIC, CPCQ, or readiness scores between the two groups at baseline. At 6 months, however, patients in the care coordination intervention group, compared with their counterparts in the control group, rated the quality of their chronic illness higher (P = .065) and reported receiving less conflicting advice from care providers (P = .018).

At 12 months, patients in the care coordination intervention group rated the following PACIC domains higher, compared with those in the control group: patient activation (P = .015), goal setting (P = .034), problem solving (P = .009), and coordination/follow-up (P = .016). Patients in the care coordination intervention group also reported more often receiving services they thought they needed (P = .03), were less confused about the role of providers (P = .012), and reported having more frequent discussions with providers about future care (P = .05).

The researchers observed no differences between the two groups in self-rating of transition readiness throughout the study period.

“[It was] surprising that this perceived higher quality care coordination and quality of care did not change perception of readiness to transfer from pediatrics to adult care,” Dr. Tuchman said. “This likely means that readiness is difficult to measure, and not related to care quality.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including the fact it “was a predominately African American, urban, publicly insured population of adolescents with special health care needs, and therefore may not be generalizable to other populations. But [it’s] still very important as Washington, D.C., has the fourth highest rate of unmet transition needs nationally.”

Maternal and Child Health, a bureau of the Department of Health and Human Services’ Health Resources and Services Administration, funded the study. Dr. Tuchman reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

This article was updated 4/30/2015.

SAN DIEGO – A dedicated care coordination intervention had a positive impact on facilitating the transition from pediatric to adult care among youth with special health care needs, a single-center randomized trial showed.

In an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, Dr. Lisa K. Tuchman said that coordination interventions in the existing literature have had mixed results. The current study is unique, she said, because it focuses on urban-based, publicly insured youth aged 16-22 years with special health care needs. “Other studies focus primarily on either pediatric or adult patients, not this in-between age group who is very vulnerable to dropping out of care,” explained Dr. Tuchman of the division of adolescent and young adult medicine at Children’s National Health System, Washington.

“Young adulthood is a time of many transitions; in this study we are focusing on transition between the pediatric and adult health care system – or when youth ‘age out’ of pediatric primary care and need to establish a new adult-oriented medical home – often in a different health system. This gap in care is known as a high-risk time for all youth, but especially for those youth with complex chronic conditions who may have adherence challenges, are navigating taking on more responsibility for their medical care, and often have a high rate of emergency department usage without a stable medical home.”

The current study also serves as a proof-of-effectiveness study. The health care transition recommendations published in Pediatrics in July 2011 are based on expert consensus, as evidence and data have been slow to evolve in this area (Pediatrics 2011;128:182-200). According to Dr. Tuchman, the current study is the first to demonstrate that these recommended guidelines improve quality and perception of care coordination, compared with a control group.

She and her colleagues recruited 210 patients aged 16-22 years from Children’s National Health System and randomly assigned them to a health care transition care coordination intervention (n = 105) or to a control group (n = 105).

The transition care coordination intervention consisted of implementing the Six Core Elements of Health Care Transition 2.0: transition policy, tracking and monitoring, transition readiness, planning, transfer of care, and completion. The last steps include communicating with the adult practice prior to planned transfer, confirming completion of transfer, and offering consultation assistance as needed.

The control group underwent usual care.

At baseline, and at 6 and 12 months, patients in both groups completed the Patient Assessment of Care for Chronic Conditions (PACIC), which assesses five domains (patient activation, delivery system design, goal setting, problem solving, and coordination/follow-up), as well as the Client Perceptions of Coordination Questionnaire (CPCQ), which assesses perception of patient-centered care and care coordination.

The study participants also completed a self-rating Likert scale (ranging from 1 to 10), a measurement of how ready they feel to transfer to adult care.

Dr. Tuchman reported that there were no statistically significant differences in PACIC, CPCQ, or readiness scores between the two groups at baseline. At 6 months, however, patients in the care coordination intervention group, compared with their counterparts in the control group, rated the quality of their chronic illness higher (P = .065) and reported receiving less conflicting advice from care providers (P = .018).

At 12 months, patients in the care coordination intervention group rated the following PACIC domains higher, compared with those in the control group: patient activation (P = .015), goal setting (P = .034), problem solving (P = .009), and coordination/follow-up (P = .016). Patients in the care coordination intervention group also reported more often receiving services they thought they needed (P = .03), were less confused about the role of providers (P = .012), and reported having more frequent discussions with providers about future care (P = .05).

The researchers observed no differences between the two groups in self-rating of transition readiness throughout the study period.

“[It was] surprising that this perceived higher quality care coordination and quality of care did not change perception of readiness to transfer from pediatrics to adult care,” Dr. Tuchman said. “This likely means that readiness is difficult to measure, and not related to care quality.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including the fact it “was a predominately African American, urban, publicly insured population of adolescents with special health care needs, and therefore may not be generalizable to other populations. But [it’s] still very important as Washington, D.C., has the fourth highest rate of unmet transition needs nationally.”

Maternal and Child Health, a bureau of the Department of Health and Human Services’ Health Resources and Services Administration, funded the study. Dr. Tuchman reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

This article was updated 4/30/2015.

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: A coordinated health care transition intervention improved many aspects of quality care for youth with chronic illnesses.

Major finding: At 12 months, compared with the control group, patients in the transition care coordination intervention group reported more often receiving services they thought they needed (P = .03), were less confused about the role of providers (P = .012), and reported having more frequent discussions with providers about future care (P = .05).

Data source: A study of 210 patients aged 16-22 years with special health care needs who were randomly assigned to a health care transition care coordination intervention or a control group.

Disclosures: Maternal and Child Health, a bureau of the Department of Health and Human Services’ Health Resources and Services Administration, funded the study. Dr. Tuchman reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

PAS: Early antibiotics linked to later overweight

SAN DIEGO – The use of oral antibiotics before 4 years of age was associated with a significantly increased risk of later overweight in a large cohort study.

“Antibiotics may provide a physician-modifiable risk factor for obesity prevention in early childhood,” Dr. Elizabeth Dawson-Hahn said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

The study included 4,938 children born at Group Health Cooperative, the Seattle-based integrated health care system. Their electronic medical records indicated that 3,533 of them, or 72%, filled one or more prescriptions for oral antibiotics at ages 0-47 months. In this group, 53% were less than 12 months old at the time of their first oral antibiotic exposure, while the rest were 12-47 months old.

At ages 48-59 months, roughly 12% of all study participants were overweight, as defined by a body mass index at or above the 85th percentile. The prevalence was similar regardless of whether a child was exposed to early oral antibiotics. However, the groups with and without early antibiotic exposure differed in key ways, including a more than threefold higher prevalence of childhood asthma in those with early antibiotic exposure.

In a prespecified logistic regression analysis adjusted for sex, Medicaid status, childhood asthma, race, maternal antibiotic exposure during pregnancy, delivery type, and birth weight, each course of oral antibiotics a child received up to 47 months of age was associated with a 3% increased likelihood of being overweight at 48-59 months – and children who got early oral antibiotics received a mean of 3.7 courses by age 47 months. Thus, early antibiotic exposure was associated on average with a significant 11% increased risk of later overweight (P = .005), reported Dr. Dawson-Hahn, a general pediatrics fellow at the University of Washington, Seattle.

The increased risk of overweight related to early antibiotics was concentrated in the children who received the medications in infancy. In another logistic regression analysis, children who got oral antibiotics prior to age 12 months were at an adjusted 20% increased risk of being overweight at ages 48-59 months, compared with children who didn’t receive oral antibiotics before 48 months of age. In contrast, the risk of overweight in kids who received oral antibiotics at ages 12-47 months wasn’t significantly different from the risk in the unexposed group.

Future studies should explore the mechanism of the observed relationship between early antibiotic exposure and later overweight, Dr. Dawson-Hahn said. One leading hypothesis is that the early exposure alters the composition of the developing gut microbiome. Antibiotics have been used for decades as a means of boosting the weight of livestock, she noted.

Dr. Dawson-Hahn said she is planning to reanalyze the data set to see if weight gain differed depending upon the type of antibiotic involved in an early exposure. More than 80% of children with early antibiotic exposure received amoxicillin.

One audience member noted that just because the health plan’s electronic pharmacy records show a prescription for oral antibiotics was filled doesn’t mean the child took the full course. Dr. Dawson-Hahn agreed, but noted that her study findings are consistent with the results of prior studies by other investigators in the past 2 years, which typically relied upon parental recall of antibiotic exposure.

“We thought documented prescription fill would be an improvement over that,” she added.

Dr. Dawson-Hahn’s study was funded by a Hearst Foundation Fellowship Award and a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award. She reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

SAN DIEGO – The use of oral antibiotics before 4 years of age was associated with a significantly increased risk of later overweight in a large cohort study.

“Antibiotics may provide a physician-modifiable risk factor for obesity prevention in early childhood,” Dr. Elizabeth Dawson-Hahn said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

The study included 4,938 children born at Group Health Cooperative, the Seattle-based integrated health care system. Their electronic medical records indicated that 3,533 of them, or 72%, filled one or more prescriptions for oral antibiotics at ages 0-47 months. In this group, 53% were less than 12 months old at the time of their first oral antibiotic exposure, while the rest were 12-47 months old.

At ages 48-59 months, roughly 12% of all study participants were overweight, as defined by a body mass index at or above the 85th percentile. The prevalence was similar regardless of whether a child was exposed to early oral antibiotics. However, the groups with and without early antibiotic exposure differed in key ways, including a more than threefold higher prevalence of childhood asthma in those with early antibiotic exposure.

In a prespecified logistic regression analysis adjusted for sex, Medicaid status, childhood asthma, race, maternal antibiotic exposure during pregnancy, delivery type, and birth weight, each course of oral antibiotics a child received up to 47 months of age was associated with a 3% increased likelihood of being overweight at 48-59 months – and children who got early oral antibiotics received a mean of 3.7 courses by age 47 months. Thus, early antibiotic exposure was associated on average with a significant 11% increased risk of later overweight (P = .005), reported Dr. Dawson-Hahn, a general pediatrics fellow at the University of Washington, Seattle.

The increased risk of overweight related to early antibiotics was concentrated in the children who received the medications in infancy. In another logistic regression analysis, children who got oral antibiotics prior to age 12 months were at an adjusted 20% increased risk of being overweight at ages 48-59 months, compared with children who didn’t receive oral antibiotics before 48 months of age. In contrast, the risk of overweight in kids who received oral antibiotics at ages 12-47 months wasn’t significantly different from the risk in the unexposed group.

Future studies should explore the mechanism of the observed relationship between early antibiotic exposure and later overweight, Dr. Dawson-Hahn said. One leading hypothesis is that the early exposure alters the composition of the developing gut microbiome. Antibiotics have been used for decades as a means of boosting the weight of livestock, she noted.

Dr. Dawson-Hahn said she is planning to reanalyze the data set to see if weight gain differed depending upon the type of antibiotic involved in an early exposure. More than 80% of children with early antibiotic exposure received amoxicillin.

One audience member noted that just because the health plan’s electronic pharmacy records show a prescription for oral antibiotics was filled doesn’t mean the child took the full course. Dr. Dawson-Hahn agreed, but noted that her study findings are consistent with the results of prior studies by other investigators in the past 2 years, which typically relied upon parental recall of antibiotic exposure.

“We thought documented prescription fill would be an improvement over that,” she added.

Dr. Dawson-Hahn’s study was funded by a Hearst Foundation Fellowship Award and a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award. She reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

SAN DIEGO – The use of oral antibiotics before 4 years of age was associated with a significantly increased risk of later overweight in a large cohort study.

“Antibiotics may provide a physician-modifiable risk factor for obesity prevention in early childhood,” Dr. Elizabeth Dawson-Hahn said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

The study included 4,938 children born at Group Health Cooperative, the Seattle-based integrated health care system. Their electronic medical records indicated that 3,533 of them, or 72%, filled one or more prescriptions for oral antibiotics at ages 0-47 months. In this group, 53% were less than 12 months old at the time of their first oral antibiotic exposure, while the rest were 12-47 months old.