User login

Empowerment's Price Tag: Shared Decision-Making May Be Costly

SAN DIEGO – Inpatients who most strongly preferred to leave medical decisions to their doctors were discharged a third of a day sooner with $970 lower mean costs per patient, compared with patients who strongly disagreed about leaving decisions to their physicians, a study of data on 20,213 patients found.

The findings throw a wrinkle into the idea that empowering patients for shared decision making is always the best approach, Hyo Jung Tak, Ph.D. said at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Administrative and patient interview data on patients in the general medicine service at the University of Chicago Medical Center from 2003-2011 included responses of to the statement, "I prefer to leave decisions about my medical care up to my doctor." Patients responded with "definitely agree" (37% of patients), "somewhat agree" (34%), "somewhat disagree" (15%), or "definitely disagree" (14%).

Although 96% of patients said that they prefer to be informed by their doctors about treatment options and to be asked their opinions, 71% of patients strongly or somewhat agreed that they prefer to leave decisions about medical care to their doctors.

Dr. Tak compared responses to data on patients’ health care utilization, length of stay, and mean total costs.

Length of stay averaged 5.3 days for the entire cohort, but patients who "definitely agreed" with letting doctors make decisions left the hospital 0.31 days sooner than did those who "definitely disagreed," reported Dr. Tak and her associate in the study, Dr. David Meltzer, both of the University.

Total costs averaged $14,500 for the entire cohort, but costs for patients who "definitely agreed" with leaving decision to doctors averaged $970 less than for patients who "definitely disagreed" with that approach.

The differences between groups in length of stay and cost were statistically significant, Dr. Tak said. The analysis controlled for the possible effects of age, gender, educational category, health status, 10 most frequent diagnoses, Charlson index, weekend admission, transfer from another institution, and attending physicians.

The results raise a provocative question, she said: "Will patient empowerment efforts in a shared-decision model increase costs" in an era in which cost-control is one of the most pressing health policy issues?

Patients who definitely agreed to leave medical decisions to their doctors were significantly more likely to have no more than a high school education and to have public or no insurance, compared with patients who definitely disagreed about leaving medical decisions to their doctors.

Shared decision making between doctors and patients has emerged as the preferred approach for medical decisions, but patient preference for this approach has not been well characterized, and the effects of this approach on medical resource utilization rarely have been studied, Dr. Tak said.

The study was limited by its reliance on data from a single institution and by a lack of information on physicians’ preferences for shared decision making and the decision-making mechanisms.

The investigators plan further studies on how preferences for shared decision making affect health outcomes and on associations between socioeconomic status and preferences about decision-making. "At least in our study, it was patients with higher education and with more generous health insurance who preferred to participate" in decision-making, she said.

Dr. Tak reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Inpatients who most strongly preferred to leave medical decisions to their doctors were discharged a third of a day sooner with $970 lower mean costs per patient, compared with patients who strongly disagreed about leaving decisions to their physicians, a study of data on 20,213 patients found.

The findings throw a wrinkle into the idea that empowering patients for shared decision making is always the best approach, Hyo Jung Tak, Ph.D. said at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Administrative and patient interview data on patients in the general medicine service at the University of Chicago Medical Center from 2003-2011 included responses of to the statement, "I prefer to leave decisions about my medical care up to my doctor." Patients responded with "definitely agree" (37% of patients), "somewhat agree" (34%), "somewhat disagree" (15%), or "definitely disagree" (14%).

Although 96% of patients said that they prefer to be informed by their doctors about treatment options and to be asked their opinions, 71% of patients strongly or somewhat agreed that they prefer to leave decisions about medical care to their doctors.

Dr. Tak compared responses to data on patients’ health care utilization, length of stay, and mean total costs.

Length of stay averaged 5.3 days for the entire cohort, but patients who "definitely agreed" with letting doctors make decisions left the hospital 0.31 days sooner than did those who "definitely disagreed," reported Dr. Tak and her associate in the study, Dr. David Meltzer, both of the University.

Total costs averaged $14,500 for the entire cohort, but costs for patients who "definitely agreed" with leaving decision to doctors averaged $970 less than for patients who "definitely disagreed" with that approach.

The differences between groups in length of stay and cost were statistically significant, Dr. Tak said. The analysis controlled for the possible effects of age, gender, educational category, health status, 10 most frequent diagnoses, Charlson index, weekend admission, transfer from another institution, and attending physicians.

The results raise a provocative question, she said: "Will patient empowerment efforts in a shared-decision model increase costs" in an era in which cost-control is one of the most pressing health policy issues?

Patients who definitely agreed to leave medical decisions to their doctors were significantly more likely to have no more than a high school education and to have public or no insurance, compared with patients who definitely disagreed about leaving medical decisions to their doctors.

Shared decision making between doctors and patients has emerged as the preferred approach for medical decisions, but patient preference for this approach has not been well characterized, and the effects of this approach on medical resource utilization rarely have been studied, Dr. Tak said.

The study was limited by its reliance on data from a single institution and by a lack of information on physicians’ preferences for shared decision making and the decision-making mechanisms.

The investigators plan further studies on how preferences for shared decision making affect health outcomes and on associations between socioeconomic status and preferences about decision-making. "At least in our study, it was patients with higher education and with more generous health insurance who preferred to participate" in decision-making, she said.

Dr. Tak reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Inpatients who most strongly preferred to leave medical decisions to their doctors were discharged a third of a day sooner with $970 lower mean costs per patient, compared with patients who strongly disagreed about leaving decisions to their physicians, a study of data on 20,213 patients found.

The findings throw a wrinkle into the idea that empowering patients for shared decision making is always the best approach, Hyo Jung Tak, Ph.D. said at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Administrative and patient interview data on patients in the general medicine service at the University of Chicago Medical Center from 2003-2011 included responses of to the statement, "I prefer to leave decisions about my medical care up to my doctor." Patients responded with "definitely agree" (37% of patients), "somewhat agree" (34%), "somewhat disagree" (15%), or "definitely disagree" (14%).

Although 96% of patients said that they prefer to be informed by their doctors about treatment options and to be asked their opinions, 71% of patients strongly or somewhat agreed that they prefer to leave decisions about medical care to their doctors.

Dr. Tak compared responses to data on patients’ health care utilization, length of stay, and mean total costs.

Length of stay averaged 5.3 days for the entire cohort, but patients who "definitely agreed" with letting doctors make decisions left the hospital 0.31 days sooner than did those who "definitely disagreed," reported Dr. Tak and her associate in the study, Dr. David Meltzer, both of the University.

Total costs averaged $14,500 for the entire cohort, but costs for patients who "definitely agreed" with leaving decision to doctors averaged $970 less than for patients who "definitely disagreed" with that approach.

The differences between groups in length of stay and cost were statistically significant, Dr. Tak said. The analysis controlled for the possible effects of age, gender, educational category, health status, 10 most frequent diagnoses, Charlson index, weekend admission, transfer from another institution, and attending physicians.

The results raise a provocative question, she said: "Will patient empowerment efforts in a shared-decision model increase costs" in an era in which cost-control is one of the most pressing health policy issues?

Patients who definitely agreed to leave medical decisions to their doctors were significantly more likely to have no more than a high school education and to have public or no insurance, compared with patients who definitely disagreed about leaving medical decisions to their doctors.

Shared decision making between doctors and patients has emerged as the preferred approach for medical decisions, but patient preference for this approach has not been well characterized, and the effects of this approach on medical resource utilization rarely have been studied, Dr. Tak said.

The study was limited by its reliance on data from a single institution and by a lack of information on physicians’ preferences for shared decision making and the decision-making mechanisms.

The investigators plan further studies on how preferences for shared decision making affect health outcomes and on associations between socioeconomic status and preferences about decision-making. "At least in our study, it was patients with higher education and with more generous health insurance who preferred to participate" in decision-making, she said.

Dr. Tak reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOCIETY OF HOSPITAL MEDICINE

Major Finding: Inpatients who most strongly preferred to leave medical decisions to their [physicians were discharged 0.31 days sooner and paid $970 lower mean costs per patient, compared with those who strongly disagreed with doing so.

Data Source: Data on 20,213 inpatients on general medicine services at one center during 2003-2011 were analyzed retrospectively.

Disclosures: Dr. Tak did not report any financial disclosures.

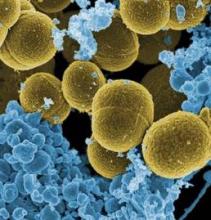

Fecal Transplant Tackles C. diff; Linezolid Good for MRSA Pneumonia

SAN DIEGO – Before treating Clostridium difficile, ask which test was used for diagnosis. For methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia, know that linezolid is now in the arsenal and that vancomycin dosing has changed.

These words of advice came from Dr. John Bartlett, professor of medicine and former chief of the division of infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, at a session on recent developments in infectious disease.

"When somebody tells you a patient has a positive C. difficile test, or a negative C. difficile test, your next question is ‘what test,’ " Dr. Bartlett said.

About half of U.S. hospitals use polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to diagnose C. diff., the other half, enzyme immunoassay (EIA), he said.

"PCR is exquisitely sensitive. It is very good for ruling it out, but there [are] false positives. EIA goes in the opposite direction. It’s not sensitive; it’s pretty good for specificity, [but] remember that if it’s a negative EIA, you have not excluded the diagnosis. EIA rules it in, PCR rules it out."

Increasingly, patients are colonized with C. diff. before they reach the hospital, probably from previous health care contact. Avoiding proton-pump inhibitors and antibiotics associated with C. diff. infection – cephalosporins, clindamycin, and fluoroquinolones – are wise moves for high-risk patients. Opiates should be avoided, too, because they cause intestinal stasis, he said.

It might take a while for the infection to respond to antibiotics; fecal transplantation is quicker.

"Fecal transplant is hot," Dr. Bartlett said. "The aesthetics" are lacking, but "it really works. Take a patient who has 10 relapses of C. diff., put in somebody else’s stool" – often delivered as a slurry through a nasogastric tube – "and the next bowel movement is normal. The biologic response is fantastic. It’s mostly done for patients who have multiple relapses, but it’s also been done in very refractory patients and those who are seriously ill," Dr. Bartlett said (Anaerobe 2009;15:285-9).

There’s a new colon-sparing surgical option for critically ill patients, diverting loop ileostomy with colonic lavage. Mortality rates are substantially lower, compared with traditional colon resection (Ann. Surg. 2011;254:423-7).

"You look at it and you say, ‘My God, why didn’t they think of this before?" Dr. Bartlett said.

There’s a new antibiotic choice, as well, after the Food and Drug Administration approved fidaxomicin for C. diff. in 2011. It has about the same cure rate as oral vancomycin, but fewer relapses, which may be "where this drug plays an important role," Dr. Bartlett said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:422-31).

For methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) pneumonia, it’s important to remember that dosing guidelines have changed for treating bacterium with vancomycin, he said.

"Five years ago, everybody with MRSA got one gram twice a day. Now we are saying give vancomycin in a dose that achieves a trough level of 15-20 mcg/mL; if the minimum inhibitory concentration is" greater than 2 mcg/mL, "maybe you ought to give something else," he said (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;49:325-7; Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;52:285-92).

And there now appears to be an alternative to vancomycin on the MRSA scene, Dr. Bartlett explained. In a head-to-head trial, linezolid "looked at least as good as vancomycin. There ought to be a comfort zone for that drug in MRSA pneumonia" (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54:621-9).

The USA300 strain now accounts for about 30% of hospital MRSA infections; the balance remain mostly "the old USA100 strain. MRSA acquired outside the hospital is more likely to be USA300, inside the hospital more likely to be USA100.

"There’s not an awful lot you need to know about the differences between them," except [that] USA300, in addition to being sensitive to USA100 antibiotics, can also be treated with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, doxycycline, and clindamycin, Dr. Bartlett said.

Dr. Bartlett said he has no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. John Bartlett, C. difficile test, polymerase chain reaction, PCR, enzyme immunoassay, EIA,

SAN DIEGO – Before treating Clostridium difficile, ask which test was used for diagnosis. For methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia, know that linezolid is now in the arsenal and that vancomycin dosing has changed.

These words of advice came from Dr. John Bartlett, professor of medicine and former chief of the division of infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, at a session on recent developments in infectious disease.

"When somebody tells you a patient has a positive C. difficile test, or a negative C. difficile test, your next question is ‘what test,’ " Dr. Bartlett said.

About half of U.S. hospitals use polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to diagnose C. diff., the other half, enzyme immunoassay (EIA), he said.

"PCR is exquisitely sensitive. It is very good for ruling it out, but there [are] false positives. EIA goes in the opposite direction. It’s not sensitive; it’s pretty good for specificity, [but] remember that if it’s a negative EIA, you have not excluded the diagnosis. EIA rules it in, PCR rules it out."

Increasingly, patients are colonized with C. diff. before they reach the hospital, probably from previous health care contact. Avoiding proton-pump inhibitors and antibiotics associated with C. diff. infection – cephalosporins, clindamycin, and fluoroquinolones – are wise moves for high-risk patients. Opiates should be avoided, too, because they cause intestinal stasis, he said.

It might take a while for the infection to respond to antibiotics; fecal transplantation is quicker.

"Fecal transplant is hot," Dr. Bartlett said. "The aesthetics" are lacking, but "it really works. Take a patient who has 10 relapses of C. diff., put in somebody else’s stool" – often delivered as a slurry through a nasogastric tube – "and the next bowel movement is normal. The biologic response is fantastic. It’s mostly done for patients who have multiple relapses, but it’s also been done in very refractory patients and those who are seriously ill," Dr. Bartlett said (Anaerobe 2009;15:285-9).

There’s a new colon-sparing surgical option for critically ill patients, diverting loop ileostomy with colonic lavage. Mortality rates are substantially lower, compared with traditional colon resection (Ann. Surg. 2011;254:423-7).

"You look at it and you say, ‘My God, why didn’t they think of this before?" Dr. Bartlett said.

There’s a new antibiotic choice, as well, after the Food and Drug Administration approved fidaxomicin for C. diff. in 2011. It has about the same cure rate as oral vancomycin, but fewer relapses, which may be "where this drug plays an important role," Dr. Bartlett said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:422-31).

For methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) pneumonia, it’s important to remember that dosing guidelines have changed for treating bacterium with vancomycin, he said.

"Five years ago, everybody with MRSA got one gram twice a day. Now we are saying give vancomycin in a dose that achieves a trough level of 15-20 mcg/mL; if the minimum inhibitory concentration is" greater than 2 mcg/mL, "maybe you ought to give something else," he said (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;49:325-7; Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;52:285-92).

And there now appears to be an alternative to vancomycin on the MRSA scene, Dr. Bartlett explained. In a head-to-head trial, linezolid "looked at least as good as vancomycin. There ought to be a comfort zone for that drug in MRSA pneumonia" (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54:621-9).

The USA300 strain now accounts for about 30% of hospital MRSA infections; the balance remain mostly "the old USA100 strain. MRSA acquired outside the hospital is more likely to be USA300, inside the hospital more likely to be USA100.

"There’s not an awful lot you need to know about the differences between them," except [that] USA300, in addition to being sensitive to USA100 antibiotics, can also be treated with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, doxycycline, and clindamycin, Dr. Bartlett said.

Dr. Bartlett said he has no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Before treating Clostridium difficile, ask which test was used for diagnosis. For methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia, know that linezolid is now in the arsenal and that vancomycin dosing has changed.

These words of advice came from Dr. John Bartlett, professor of medicine and former chief of the division of infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, at a session on recent developments in infectious disease.

"When somebody tells you a patient has a positive C. difficile test, or a negative C. difficile test, your next question is ‘what test,’ " Dr. Bartlett said.

About half of U.S. hospitals use polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to diagnose C. diff., the other half, enzyme immunoassay (EIA), he said.

"PCR is exquisitely sensitive. It is very good for ruling it out, but there [are] false positives. EIA goes in the opposite direction. It’s not sensitive; it’s pretty good for specificity, [but] remember that if it’s a negative EIA, you have not excluded the diagnosis. EIA rules it in, PCR rules it out."

Increasingly, patients are colonized with C. diff. before they reach the hospital, probably from previous health care contact. Avoiding proton-pump inhibitors and antibiotics associated with C. diff. infection – cephalosporins, clindamycin, and fluoroquinolones – are wise moves for high-risk patients. Opiates should be avoided, too, because they cause intestinal stasis, he said.

It might take a while for the infection to respond to antibiotics; fecal transplantation is quicker.

"Fecal transplant is hot," Dr. Bartlett said. "The aesthetics" are lacking, but "it really works. Take a patient who has 10 relapses of C. diff., put in somebody else’s stool" – often delivered as a slurry through a nasogastric tube – "and the next bowel movement is normal. The biologic response is fantastic. It’s mostly done for patients who have multiple relapses, but it’s also been done in very refractory patients and those who are seriously ill," Dr. Bartlett said (Anaerobe 2009;15:285-9).

There’s a new colon-sparing surgical option for critically ill patients, diverting loop ileostomy with colonic lavage. Mortality rates are substantially lower, compared with traditional colon resection (Ann. Surg. 2011;254:423-7).

"You look at it and you say, ‘My God, why didn’t they think of this before?" Dr. Bartlett said.

There’s a new antibiotic choice, as well, after the Food and Drug Administration approved fidaxomicin for C. diff. in 2011. It has about the same cure rate as oral vancomycin, but fewer relapses, which may be "where this drug plays an important role," Dr. Bartlett said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:422-31).

For methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) pneumonia, it’s important to remember that dosing guidelines have changed for treating bacterium with vancomycin, he said.

"Five years ago, everybody with MRSA got one gram twice a day. Now we are saying give vancomycin in a dose that achieves a trough level of 15-20 mcg/mL; if the minimum inhibitory concentration is" greater than 2 mcg/mL, "maybe you ought to give something else," he said (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;49:325-7; Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;52:285-92).

And there now appears to be an alternative to vancomycin on the MRSA scene, Dr. Bartlett explained. In a head-to-head trial, linezolid "looked at least as good as vancomycin. There ought to be a comfort zone for that drug in MRSA pneumonia" (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54:621-9).

The USA300 strain now accounts for about 30% of hospital MRSA infections; the balance remain mostly "the old USA100 strain. MRSA acquired outside the hospital is more likely to be USA300, inside the hospital more likely to be USA100.

"There’s not an awful lot you need to know about the differences between them," except [that] USA300, in addition to being sensitive to USA100 antibiotics, can also be treated with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, doxycycline, and clindamycin, Dr. Bartlett said.

Dr. Bartlett said he has no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. John Bartlett, C. difficile test, polymerase chain reaction, PCR, enzyme immunoassay, EIA,

Dr. John Bartlett, C. difficile test, polymerase chain reaction, PCR, enzyme immunoassay, EIA,

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOCIETY OF HOSPITAL MEDICINE

More Cardiac Arrest Linked With Fewer Medical ICU Beds

SAN DIEGO – Decreased availability of medical ICU beds was significantly associated with a 27% higher risk for cardiac arrest on general hospital wards in an observational cohort study of 68 ICU beds and 258 ward beds at one academic medical center.

The availability of nonmedical ICU beds did not affect the risk of cardiac arrests. While total ICU bed availability was associated with increased cardiac arrests, this did not reach statistical significance, Michael Huber and his associates reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Across the United States, the approximately 90,000 ICU beds account for less than 15% of all hospital beds and are distributed unevenly geographically. Demand for ICU beds is projected to increase 80% over the next 209 years as the population ages and comorbidities increase, said Mr. Huber, a fourth-year medical student at the University of Chicago.

The findings suggest a need to increase ICU bed availability by adding beds, adopting flexible surgery scheduling for planned surgical ICU admissions (which in turn may open up ICU beds for medical patients), or implementing practices to reduce ICU length of stay, he suggested. "Of course, some ICU beds are taken by patients awaiting discharge to wards, so prioritizing ward beds to ICU discharges may also free up ICU beds."

A second implication of the study is that ward patients may be triaged inappropriately when ICU beds are severely limited, he added. Improved ICU triage practices may be needed, particularly at times of limited medical ICU bed availability.

The study was honored as one of the best research presentations at the meeting. It defined cardiac arrest as loss of a palpable pulse with a resuscitation attempt.

Researchers analyzed 96 cardiac arrests on the general wards (81 arrests on medical wards and 15 on non-medical wards). During 1,716 work shifts, there were a median of 217 patients on the wards at the start of 12-hour shifts. A median of five total ICU beds were available at shift start. For medical ICU beds, a median of one was available at shift start, and for nonmedical ICU beds, a median of three were available at shift start.

The incidence rate of cardiac arrests on the general wards was 6% higher for each fewer ICU bed, but this was not a statistically significant difference. For each fewer medical ICU bed, a 27% increase in cardiac arrests on the general wards was seen, which was significant. No association appeared between non-medical ICU bed availability and cardiac arrests on the wards.

The investigators calculated a "ward cardiac arrest rate" (defined as the number of ward cardiac arrests divided by ward occupancy at shift start) and compared these by the number of ICU beds available. The mean cardiac arrest rate was 2.6 arrests per 10,000 ward patients per shift. The rate when no medical ICU beds were available was nearly double the rate when one or more medical ICU beds were available. The cardiac arrest rate stabilized at or below the mean when one, two, or three or more medical ICU beds were available, Mr. Huber said.

Previous studies focused mostly on the effects of bed availability on patients in the ICU. They found no association with mortality but showed increased severity of illness and readmission rates as ICU bed availability decreased. Previous studies of ward patients were limited to high-risk patients who were evaluated for ICU admission; these found higher mortality rates in patients who were refused admission to the ICU, he said.

Mr. Huber reported having no financial disclosures. One of his associates reported financial ties to Philips Healthcare and Sotera Wireless.

SAN DIEGO – Decreased availability of medical ICU beds was significantly associated with a 27% higher risk for cardiac arrest on general hospital wards in an observational cohort study of 68 ICU beds and 258 ward beds at one academic medical center.

The availability of nonmedical ICU beds did not affect the risk of cardiac arrests. While total ICU bed availability was associated with increased cardiac arrests, this did not reach statistical significance, Michael Huber and his associates reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Across the United States, the approximately 90,000 ICU beds account for less than 15% of all hospital beds and are distributed unevenly geographically. Demand for ICU beds is projected to increase 80% over the next 209 years as the population ages and comorbidities increase, said Mr. Huber, a fourth-year medical student at the University of Chicago.

The findings suggest a need to increase ICU bed availability by adding beds, adopting flexible surgery scheduling for planned surgical ICU admissions (which in turn may open up ICU beds for medical patients), or implementing practices to reduce ICU length of stay, he suggested. "Of course, some ICU beds are taken by patients awaiting discharge to wards, so prioritizing ward beds to ICU discharges may also free up ICU beds."

A second implication of the study is that ward patients may be triaged inappropriately when ICU beds are severely limited, he added. Improved ICU triage practices may be needed, particularly at times of limited medical ICU bed availability.

The study was honored as one of the best research presentations at the meeting. It defined cardiac arrest as loss of a palpable pulse with a resuscitation attempt.

Researchers analyzed 96 cardiac arrests on the general wards (81 arrests on medical wards and 15 on non-medical wards). During 1,716 work shifts, there were a median of 217 patients on the wards at the start of 12-hour shifts. A median of five total ICU beds were available at shift start. For medical ICU beds, a median of one was available at shift start, and for nonmedical ICU beds, a median of three were available at shift start.

The incidence rate of cardiac arrests on the general wards was 6% higher for each fewer ICU bed, but this was not a statistically significant difference. For each fewer medical ICU bed, a 27% increase in cardiac arrests on the general wards was seen, which was significant. No association appeared between non-medical ICU bed availability and cardiac arrests on the wards.

The investigators calculated a "ward cardiac arrest rate" (defined as the number of ward cardiac arrests divided by ward occupancy at shift start) and compared these by the number of ICU beds available. The mean cardiac arrest rate was 2.6 arrests per 10,000 ward patients per shift. The rate when no medical ICU beds were available was nearly double the rate when one or more medical ICU beds were available. The cardiac arrest rate stabilized at or below the mean when one, two, or three or more medical ICU beds were available, Mr. Huber said.

Previous studies focused mostly on the effects of bed availability on patients in the ICU. They found no association with mortality but showed increased severity of illness and readmission rates as ICU bed availability decreased. Previous studies of ward patients were limited to high-risk patients who were evaluated for ICU admission; these found higher mortality rates in patients who were refused admission to the ICU, he said.

Mr. Huber reported having no financial disclosures. One of his associates reported financial ties to Philips Healthcare and Sotera Wireless.

SAN DIEGO – Decreased availability of medical ICU beds was significantly associated with a 27% higher risk for cardiac arrest on general hospital wards in an observational cohort study of 68 ICU beds and 258 ward beds at one academic medical center.

The availability of nonmedical ICU beds did not affect the risk of cardiac arrests. While total ICU bed availability was associated with increased cardiac arrests, this did not reach statistical significance, Michael Huber and his associates reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Across the United States, the approximately 90,000 ICU beds account for less than 15% of all hospital beds and are distributed unevenly geographically. Demand for ICU beds is projected to increase 80% over the next 209 years as the population ages and comorbidities increase, said Mr. Huber, a fourth-year medical student at the University of Chicago.

The findings suggest a need to increase ICU bed availability by adding beds, adopting flexible surgery scheduling for planned surgical ICU admissions (which in turn may open up ICU beds for medical patients), or implementing practices to reduce ICU length of stay, he suggested. "Of course, some ICU beds are taken by patients awaiting discharge to wards, so prioritizing ward beds to ICU discharges may also free up ICU beds."

A second implication of the study is that ward patients may be triaged inappropriately when ICU beds are severely limited, he added. Improved ICU triage practices may be needed, particularly at times of limited medical ICU bed availability.

The study was honored as one of the best research presentations at the meeting. It defined cardiac arrest as loss of a palpable pulse with a resuscitation attempt.

Researchers analyzed 96 cardiac arrests on the general wards (81 arrests on medical wards and 15 on non-medical wards). During 1,716 work shifts, there were a median of 217 patients on the wards at the start of 12-hour shifts. A median of five total ICU beds were available at shift start. For medical ICU beds, a median of one was available at shift start, and for nonmedical ICU beds, a median of three were available at shift start.

The incidence rate of cardiac arrests on the general wards was 6% higher for each fewer ICU bed, but this was not a statistically significant difference. For each fewer medical ICU bed, a 27% increase in cardiac arrests on the general wards was seen, which was significant. No association appeared between non-medical ICU bed availability and cardiac arrests on the wards.

The investigators calculated a "ward cardiac arrest rate" (defined as the number of ward cardiac arrests divided by ward occupancy at shift start) and compared these by the number of ICU beds available. The mean cardiac arrest rate was 2.6 arrests per 10,000 ward patients per shift. The rate when no medical ICU beds were available was nearly double the rate when one or more medical ICU beds were available. The cardiac arrest rate stabilized at or below the mean when one, two, or three or more medical ICU beds were available, Mr. Huber said.

Previous studies focused mostly on the effects of bed availability on patients in the ICU. They found no association with mortality but showed increased severity of illness and readmission rates as ICU bed availability decreased. Previous studies of ward patients were limited to high-risk patients who were evaluated for ICU admission; these found higher mortality rates in patients who were refused admission to the ICU, he said.

Mr. Huber reported having no financial disclosures. One of his associates reported financial ties to Philips Healthcare and Sotera Wireless.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOCIETY OF HOSPITAL MEDICINE

Major Finding: Each fewer medical ICU bed was associated with a 27% increased risk for cardiac arrests on general hospital wards.

Data Source: Data came from an observational cohort study of 96 cardiac arrests in one academic medical center with 68 total ICU beds and 258 ward beds.

Disclosures: Mr. Huber reported having no financial disclosures. One of his associates reported financial ties to Philips Healthcare and Sotera Wireless.

Care Plans Decreased High-Risk Patients' ED Visits

SAN DIEGO – Making specialized care plans for 28 high-risk patients easily accessible to physicians by computer decreased hospitalizations and emergency department visits by 65% over 2 months.

In the 2 months before implementation of the care plan system, the 28 patients visited EDs 122 times and had 59 admissions to the hospital. ED visits decreased to 53 and admissions dropped to 9 for these patients in the 2 months after implementation of the system, an overall reduction of about 65%, Dr. Richard J. Hilger and his associates reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

The study was honored by the Society as one of the best three presentations at the meeting.

"Our financial department says that ideally, in a closed system, that would be a cost savings to society of over half a million dollars just for 28 patients over just a 2-month period," said Dr. Hilger, medical director of Care Management at Regions Hospital, St. Paul, Minn., a part of HealthPartners Medical Group.

Presently, there’s no way of knowing if patients circumvented the care plans by going to another hospital that’s not in the HealthPartners Medical Group, but records suggest that "only a handful of patients have left our system," he added.

The investigators next will try to integrate the care plans among health care systems in their geographic area, "so that care plans can be used from system to system," Dr. Hilger said.

The pilot study focused on three groups of patients with frequent ED visits and hospitalizations: narcotic-seeking patients, patients with mental health diagnoses (especially borderline traits), and patients with a long history of not complying with medical therapy.

A committee of hospital leaders created the specialized plans to restrict care in hopes of redirecting these patients to clinics and their primary care physicians, thus reducing medically unnecessary admissions and ED visits. The committee included specialists from hospital medicine, nursing, emergency medicine, primary care, risk management, quality control, care management, and electronic medical records.

When any physician in the medical group went to the computerized record of one of these patients, an orange bar across the bottom of the screen alerted the physician that a care plan was in place. Clicking on the bar opened a description of the plan, which could be read to the patient.

The "alpha case" that got the hospital team to start the care plan system was a 35-year-old patient named Ann who abused narcotics and had type 1 diabetes, borderline personality disorder, and severe anxiety disorder. Frequently, she would visit the ED in diabetic distress and would refuse insulin unless she was given narcotics. In the 6 weeks prior to institution of a care plan for her, she came to the ED 14 times and was admitted 6 times. In the 14 weeks after the plan started, she visited the ED twice and was admitted twice.

A Sample Plan

Dr. Hilger read an example of a care plan for narcotic-seeking patients, which said that care guidelines were being instituted in order to provide consistent and quality care that maintains the patient’s safety when seen by providers who may not know the patient well. The guidelines are as follows: The patient would not receive IV narcotics in the ED unless there is a medical condition unrelated to chronic pain. The ED should not be used for routine medical care or management of chronic pain, but the physician with the patient would help set up more frequent clinic visits. The ED or inpatient physicians would not fill orders for oral narcotics at discharge. The patient’s outpatient regimen should be used for chronic pain or exacerbations of chronic pain, and IV Benadryl or IV benzodiazepines should not be used for pain control.

The physician should offer substance-abuse treatment programs when appropriate, the care plan continued. Repeated imaging studies such as CT scans were discouraged unless new pathology was suggested by an exam, vital signs, and/or screening labs, because repeated imaging exposes the patient to radiation. The patient should not attempt to obtain narcotic prescriptions from anyone other than the designated primary care provider. If the patient does not follow the rules described in the care plan, the medical group "would have to consider releasing you from our care, since noncompliance leads us to being unable to care for you safely and appropriately."

Dr. Hilger cited a New Yorker magazine article by Dr. Atul Gawande of Harvard University describing the benefits of coordinating care for the most chronically expensive patients. The use of care plans promotes consistency in care; reinforces goals and expectations; empowers patients to take steps toward positive change; fosters patient trust; increases use of primary care; and decreases hospitalizations, readmissions, and total costs, the article suggests.

"We didn’t invent this" idea of care plans, Dr. Hilger said. Many hospitals are experimenting with elements of specialized care plans, but research so far has been limited mainly to EDs, he added. Specialized care plans are becoming popular for the less than 1% of patients with high rates of medically unnecessary emergency visits and admissions.

Dr. Hilger reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Making specialized care plans for 28 high-risk patients easily accessible to physicians by computer decreased hospitalizations and emergency department visits by 65% over 2 months.

In the 2 months before implementation of the care plan system, the 28 patients visited EDs 122 times and had 59 admissions to the hospital. ED visits decreased to 53 and admissions dropped to 9 for these patients in the 2 months after implementation of the system, an overall reduction of about 65%, Dr. Richard J. Hilger and his associates reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

The study was honored by the Society as one of the best three presentations at the meeting.

"Our financial department says that ideally, in a closed system, that would be a cost savings to society of over half a million dollars just for 28 patients over just a 2-month period," said Dr. Hilger, medical director of Care Management at Regions Hospital, St. Paul, Minn., a part of HealthPartners Medical Group.

Presently, there’s no way of knowing if patients circumvented the care plans by going to another hospital that’s not in the HealthPartners Medical Group, but records suggest that "only a handful of patients have left our system," he added.

The investigators next will try to integrate the care plans among health care systems in their geographic area, "so that care plans can be used from system to system," Dr. Hilger said.

The pilot study focused on three groups of patients with frequent ED visits and hospitalizations: narcotic-seeking patients, patients with mental health diagnoses (especially borderline traits), and patients with a long history of not complying with medical therapy.

A committee of hospital leaders created the specialized plans to restrict care in hopes of redirecting these patients to clinics and their primary care physicians, thus reducing medically unnecessary admissions and ED visits. The committee included specialists from hospital medicine, nursing, emergency medicine, primary care, risk management, quality control, care management, and electronic medical records.

When any physician in the medical group went to the computerized record of one of these patients, an orange bar across the bottom of the screen alerted the physician that a care plan was in place. Clicking on the bar opened a description of the plan, which could be read to the patient.

The "alpha case" that got the hospital team to start the care plan system was a 35-year-old patient named Ann who abused narcotics and had type 1 diabetes, borderline personality disorder, and severe anxiety disorder. Frequently, she would visit the ED in diabetic distress and would refuse insulin unless she was given narcotics. In the 6 weeks prior to institution of a care plan for her, she came to the ED 14 times and was admitted 6 times. In the 14 weeks after the plan started, she visited the ED twice and was admitted twice.

A Sample Plan

Dr. Hilger read an example of a care plan for narcotic-seeking patients, which said that care guidelines were being instituted in order to provide consistent and quality care that maintains the patient’s safety when seen by providers who may not know the patient well. The guidelines are as follows: The patient would not receive IV narcotics in the ED unless there is a medical condition unrelated to chronic pain. The ED should not be used for routine medical care or management of chronic pain, but the physician with the patient would help set up more frequent clinic visits. The ED or inpatient physicians would not fill orders for oral narcotics at discharge. The patient’s outpatient regimen should be used for chronic pain or exacerbations of chronic pain, and IV Benadryl or IV benzodiazepines should not be used for pain control.

The physician should offer substance-abuse treatment programs when appropriate, the care plan continued. Repeated imaging studies such as CT scans were discouraged unless new pathology was suggested by an exam, vital signs, and/or screening labs, because repeated imaging exposes the patient to radiation. The patient should not attempt to obtain narcotic prescriptions from anyone other than the designated primary care provider. If the patient does not follow the rules described in the care plan, the medical group "would have to consider releasing you from our care, since noncompliance leads us to being unable to care for you safely and appropriately."

Dr. Hilger cited a New Yorker magazine article by Dr. Atul Gawande of Harvard University describing the benefits of coordinating care for the most chronically expensive patients. The use of care plans promotes consistency in care; reinforces goals and expectations; empowers patients to take steps toward positive change; fosters patient trust; increases use of primary care; and decreases hospitalizations, readmissions, and total costs, the article suggests.

"We didn’t invent this" idea of care plans, Dr. Hilger said. Many hospitals are experimenting with elements of specialized care plans, but research so far has been limited mainly to EDs, he added. Specialized care plans are becoming popular for the less than 1% of patients with high rates of medically unnecessary emergency visits and admissions.

Dr. Hilger reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Making specialized care plans for 28 high-risk patients easily accessible to physicians by computer decreased hospitalizations and emergency department visits by 65% over 2 months.

In the 2 months before implementation of the care plan system, the 28 patients visited EDs 122 times and had 59 admissions to the hospital. ED visits decreased to 53 and admissions dropped to 9 for these patients in the 2 months after implementation of the system, an overall reduction of about 65%, Dr. Richard J. Hilger and his associates reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

The study was honored by the Society as one of the best three presentations at the meeting.

"Our financial department says that ideally, in a closed system, that would be a cost savings to society of over half a million dollars just for 28 patients over just a 2-month period," said Dr. Hilger, medical director of Care Management at Regions Hospital, St. Paul, Minn., a part of HealthPartners Medical Group.

Presently, there’s no way of knowing if patients circumvented the care plans by going to another hospital that’s not in the HealthPartners Medical Group, but records suggest that "only a handful of patients have left our system," he added.

The investigators next will try to integrate the care plans among health care systems in their geographic area, "so that care plans can be used from system to system," Dr. Hilger said.

The pilot study focused on three groups of patients with frequent ED visits and hospitalizations: narcotic-seeking patients, patients with mental health diagnoses (especially borderline traits), and patients with a long history of not complying with medical therapy.

A committee of hospital leaders created the specialized plans to restrict care in hopes of redirecting these patients to clinics and their primary care physicians, thus reducing medically unnecessary admissions and ED visits. The committee included specialists from hospital medicine, nursing, emergency medicine, primary care, risk management, quality control, care management, and electronic medical records.

When any physician in the medical group went to the computerized record of one of these patients, an orange bar across the bottom of the screen alerted the physician that a care plan was in place. Clicking on the bar opened a description of the plan, which could be read to the patient.

The "alpha case" that got the hospital team to start the care plan system was a 35-year-old patient named Ann who abused narcotics and had type 1 diabetes, borderline personality disorder, and severe anxiety disorder. Frequently, she would visit the ED in diabetic distress and would refuse insulin unless she was given narcotics. In the 6 weeks prior to institution of a care plan for her, she came to the ED 14 times and was admitted 6 times. In the 14 weeks after the plan started, she visited the ED twice and was admitted twice.

A Sample Plan

Dr. Hilger read an example of a care plan for narcotic-seeking patients, which said that care guidelines were being instituted in order to provide consistent and quality care that maintains the patient’s safety when seen by providers who may not know the patient well. The guidelines are as follows: The patient would not receive IV narcotics in the ED unless there is a medical condition unrelated to chronic pain. The ED should not be used for routine medical care or management of chronic pain, but the physician with the patient would help set up more frequent clinic visits. The ED or inpatient physicians would not fill orders for oral narcotics at discharge. The patient’s outpatient regimen should be used for chronic pain or exacerbations of chronic pain, and IV Benadryl or IV benzodiazepines should not be used for pain control.

The physician should offer substance-abuse treatment programs when appropriate, the care plan continued. Repeated imaging studies such as CT scans were discouraged unless new pathology was suggested by an exam, vital signs, and/or screening labs, because repeated imaging exposes the patient to radiation. The patient should not attempt to obtain narcotic prescriptions from anyone other than the designated primary care provider. If the patient does not follow the rules described in the care plan, the medical group "would have to consider releasing you from our care, since noncompliance leads us to being unable to care for you safely and appropriately."

Dr. Hilger cited a New Yorker magazine article by Dr. Atul Gawande of Harvard University describing the benefits of coordinating care for the most chronically expensive patients. The use of care plans promotes consistency in care; reinforces goals and expectations; empowers patients to take steps toward positive change; fosters patient trust; increases use of primary care; and decreases hospitalizations, readmissions, and total costs, the article suggests.

"We didn’t invent this" idea of care plans, Dr. Hilger said. Many hospitals are experimenting with elements of specialized care plans, but research so far has been limited mainly to EDs, he added. Specialized care plans are becoming popular for the less than 1% of patients with high rates of medically unnecessary emergency visits and admissions.

Dr. Hilger reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOCIETY OF HOSPITAL MEDICINE

Intensivist Service Reduced Infections, Ventilator Days

SAN DIEGO – Converting some conventional hospitalists to intensive care unit hospitalists reduced the average length of stay, duration on ventilators, and rate of catheter-related bloodstream infections, worth an estimated $1.45 million per year in savings at one community hospital.

After a year with the intensivist hospitalist team in action, the rate of catheter-related bloodstream infections decreased by 75%, the average length of ICU stay declined by 22%, ventilator days decreased by 35%, and the rate of ventilator-associated pneumonia was brought down to 0%. In addition, 30% more general ward patients were discharged before noon by non-ICU hospitalists, Dr. Min Hlaing and Dr. Rod Felber reported in a joint presentation at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Surveys of other hospital staff suggested that having the intensivist hospitalist team improved communication between physician and nurses and between hospitalists and subspecialists. ICU nursing staff, respiratory technicians, and the sole pulmonologist reported being very satisfied with the ICU hospitalist care, said Dr. Hlaing and Dr. Felber of Lodi (Calif.) Memorial Hospital. The center has 270 beds.

The reductions in length of stay, ventilator days, and infections alone represent a savings to the hospital of $1.45 million per year, the speakers and their associates estimated.

Patient- and family-satisfaction scores increased after institution of the ICU hospitalist service. Job satisfaction among nurses improved, which increased retention of nurses in both the ICU and general ward. The hospital found it easier to recruit and retain specialists and easier to recruit general ward hospitalists because they no longer needed to have ICU skills. Satisfaction and retention among hospitalists as a whole improved at the hospital, said Dr. Felber, medical director of the hospitalist program.

To start the trial, Dr. Hlaing, who is an associate director of the hospitalist program, identified four of his hospitalists who were comfortable in caring for critically ill patients. He assigned them and himself to manage the 10-bed ICU and closed the ICU to other hospitalists. Team members became credentialed to perform procedures such as ultrasound-guided central venous catheter placement, arterial catheter insertion, lumbar puncture, paracentesis, endotracheal intubation, and ventilator management. They completed a course in the fundamentals of critical care support, and utilized evidence-based standardized order sets that were developed for common ICU conditions.

The ICU hospitalists had dedicated times for multidisciplinary rounds, family meetings, ICU-specific committees, and education of nurses. An emphasis on continuity of care enabled ICU patients to be admitted, rounded on daily in the ICU, followed after transfer to the medical/surgical floor, and discharged home by the same hospitalist.

After a year of the ICU hospitalist service in action, the investigators conducted a 360-degree evaluation and review of the major hospital stakeholders.

The workload of caring for an ICU patient was considered to be 1.5 times that of medical/surgical floor patients, so the intensivist hospitalists saw fewer patients than other hospitalists. The ICU hospitalists were paid $5 per hour more than other hospitalists. The Relative Value Units for ICU patient care and performance of procedures also led to higher compensation compared with medical/surgical hospitalists, Dr. Felber said.

During the year, the hospital administration requested expansion of the ICU hospitalist model from 12 hours per day of coverage to 24 hours per day.

"If you have hospitalists who are capable of doing it, an ICU hospitalist model is one of the most sustainable and economically viable options to provide quality care to our most critically ill patients," Dr. Felber said.

Previous studies suggest that, in general, only 23% of critically ill patients are seen by intensivists, the speakers said. ICUs consume a quarter of hospital budgets on average. The aging U.S. population will increase demand for intensivist services by 38%. Strategies proposed for hospitals to cope with this evolution include hiring more intensivists, greater use of telemedicine, and partnering with hospitalists, as in the current study.

Dr. Hlaing and Dr. Felber did not report financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Converting some conventional hospitalists to intensive care unit hospitalists reduced the average length of stay, duration on ventilators, and rate of catheter-related bloodstream infections, worth an estimated $1.45 million per year in savings at one community hospital.

After a year with the intensivist hospitalist team in action, the rate of catheter-related bloodstream infections decreased by 75%, the average length of ICU stay declined by 22%, ventilator days decreased by 35%, and the rate of ventilator-associated pneumonia was brought down to 0%. In addition, 30% more general ward patients were discharged before noon by non-ICU hospitalists, Dr. Min Hlaing and Dr. Rod Felber reported in a joint presentation at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Surveys of other hospital staff suggested that having the intensivist hospitalist team improved communication between physician and nurses and between hospitalists and subspecialists. ICU nursing staff, respiratory technicians, and the sole pulmonologist reported being very satisfied with the ICU hospitalist care, said Dr. Hlaing and Dr. Felber of Lodi (Calif.) Memorial Hospital. The center has 270 beds.

The reductions in length of stay, ventilator days, and infections alone represent a savings to the hospital of $1.45 million per year, the speakers and their associates estimated.

Patient- and family-satisfaction scores increased after institution of the ICU hospitalist service. Job satisfaction among nurses improved, which increased retention of nurses in both the ICU and general ward. The hospital found it easier to recruit and retain specialists and easier to recruit general ward hospitalists because they no longer needed to have ICU skills. Satisfaction and retention among hospitalists as a whole improved at the hospital, said Dr. Felber, medical director of the hospitalist program.

To start the trial, Dr. Hlaing, who is an associate director of the hospitalist program, identified four of his hospitalists who were comfortable in caring for critically ill patients. He assigned them and himself to manage the 10-bed ICU and closed the ICU to other hospitalists. Team members became credentialed to perform procedures such as ultrasound-guided central venous catheter placement, arterial catheter insertion, lumbar puncture, paracentesis, endotracheal intubation, and ventilator management. They completed a course in the fundamentals of critical care support, and utilized evidence-based standardized order sets that were developed for common ICU conditions.

The ICU hospitalists had dedicated times for multidisciplinary rounds, family meetings, ICU-specific committees, and education of nurses. An emphasis on continuity of care enabled ICU patients to be admitted, rounded on daily in the ICU, followed after transfer to the medical/surgical floor, and discharged home by the same hospitalist.

After a year of the ICU hospitalist service in action, the investigators conducted a 360-degree evaluation and review of the major hospital stakeholders.

The workload of caring for an ICU patient was considered to be 1.5 times that of medical/surgical floor patients, so the intensivist hospitalists saw fewer patients than other hospitalists. The ICU hospitalists were paid $5 per hour more than other hospitalists. The Relative Value Units for ICU patient care and performance of procedures also led to higher compensation compared with medical/surgical hospitalists, Dr. Felber said.

During the year, the hospital administration requested expansion of the ICU hospitalist model from 12 hours per day of coverage to 24 hours per day.

"If you have hospitalists who are capable of doing it, an ICU hospitalist model is one of the most sustainable and economically viable options to provide quality care to our most critically ill patients," Dr. Felber said.

Previous studies suggest that, in general, only 23% of critically ill patients are seen by intensivists, the speakers said. ICUs consume a quarter of hospital budgets on average. The aging U.S. population will increase demand for intensivist services by 38%. Strategies proposed for hospitals to cope with this evolution include hiring more intensivists, greater use of telemedicine, and partnering with hospitalists, as in the current study.

Dr. Hlaing and Dr. Felber did not report financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Converting some conventional hospitalists to intensive care unit hospitalists reduced the average length of stay, duration on ventilators, and rate of catheter-related bloodstream infections, worth an estimated $1.45 million per year in savings at one community hospital.

After a year with the intensivist hospitalist team in action, the rate of catheter-related bloodstream infections decreased by 75%, the average length of ICU stay declined by 22%, ventilator days decreased by 35%, and the rate of ventilator-associated pneumonia was brought down to 0%. In addition, 30% more general ward patients were discharged before noon by non-ICU hospitalists, Dr. Min Hlaing and Dr. Rod Felber reported in a joint presentation at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Surveys of other hospital staff suggested that having the intensivist hospitalist team improved communication between physician and nurses and between hospitalists and subspecialists. ICU nursing staff, respiratory technicians, and the sole pulmonologist reported being very satisfied with the ICU hospitalist care, said Dr. Hlaing and Dr. Felber of Lodi (Calif.) Memorial Hospital. The center has 270 beds.

The reductions in length of stay, ventilator days, and infections alone represent a savings to the hospital of $1.45 million per year, the speakers and their associates estimated.

Patient- and family-satisfaction scores increased after institution of the ICU hospitalist service. Job satisfaction among nurses improved, which increased retention of nurses in both the ICU and general ward. The hospital found it easier to recruit and retain specialists and easier to recruit general ward hospitalists because they no longer needed to have ICU skills. Satisfaction and retention among hospitalists as a whole improved at the hospital, said Dr. Felber, medical director of the hospitalist program.

To start the trial, Dr. Hlaing, who is an associate director of the hospitalist program, identified four of his hospitalists who were comfortable in caring for critically ill patients. He assigned them and himself to manage the 10-bed ICU and closed the ICU to other hospitalists. Team members became credentialed to perform procedures such as ultrasound-guided central venous catheter placement, arterial catheter insertion, lumbar puncture, paracentesis, endotracheal intubation, and ventilator management. They completed a course in the fundamentals of critical care support, and utilized evidence-based standardized order sets that were developed for common ICU conditions.

The ICU hospitalists had dedicated times for multidisciplinary rounds, family meetings, ICU-specific committees, and education of nurses. An emphasis on continuity of care enabled ICU patients to be admitted, rounded on daily in the ICU, followed after transfer to the medical/surgical floor, and discharged home by the same hospitalist.

After a year of the ICU hospitalist service in action, the investigators conducted a 360-degree evaluation and review of the major hospital stakeholders.

The workload of caring for an ICU patient was considered to be 1.5 times that of medical/surgical floor patients, so the intensivist hospitalists saw fewer patients than other hospitalists. The ICU hospitalists were paid $5 per hour more than other hospitalists. The Relative Value Units for ICU patient care and performance of procedures also led to higher compensation compared with medical/surgical hospitalists, Dr. Felber said.

During the year, the hospital administration requested expansion of the ICU hospitalist model from 12 hours per day of coverage to 24 hours per day.

"If you have hospitalists who are capable of doing it, an ICU hospitalist model is one of the most sustainable and economically viable options to provide quality care to our most critically ill patients," Dr. Felber said.

Previous studies suggest that, in general, only 23% of critically ill patients are seen by intensivists, the speakers said. ICUs consume a quarter of hospital budgets on average. The aging U.S. population will increase demand for intensivist services by 38%. Strategies proposed for hospitals to cope with this evolution include hiring more intensivists, greater use of telemedicine, and partnering with hospitalists, as in the current study.

Dr. Hlaing and Dr. Felber did not report financial disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOCIETY OF HOSPITAL MEDICINE

Statins' Effect on Pneumonia Mortality Murky in Meta-Analysis

SAN DIEGO – Statins may reduce mortality after pneumonia, but this possible benefit may weaken or disappear in important subgroups of patients, results of a double meta-analysis suggest.

The analyses of data from 13 studies including 254,950 adults with pneumonia found a significant 38% decreased likelihood of dying in patients who were on statins compared with non-statin users, before adjusting for confounding factors, Dr. Vineet Chopra and his associates reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

The investigators then pooled adjusted data from the studies accounting for the effects of various confounders, and found a combined reduction in the risk for death after pneumonia of 34% in statin users compared with nonusers, which also was statistically significant, said Dr. Chopra, a hospitalist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

He and his associates took it a step further, however, and conducted their own subgroup analyses of the studies’ data because of the heterogeneity of the studies and their patient populations, and because most studies used administrative data sets, which often don’t include the severity of illness and other important factors influencing mortality from pneumonia. Authors of 7 of the 13 studies provided unpublished data.

The subgroup analyses done by Dr. Chopra and his colleagues adjusted for the effects of smoking, vaccination status, severity of pneumonia, and whether the studies featured a score for the propensity of a patient to receive statins. They also looked at whether the studies included "uncommon covariates" such as time to antibiotic delivery, the presence of bacteremia, the presence of advance directives, the use of home health services, residence in a nursing home, and measures of frailty other than comorbidity indices.

"When we started teasing out from each model whether or not they adjusted for" any of these potential confounders and pooled the effects separately for each confounder, "any effect of statin use on mortality after pneumonia was completely eliminated," Dr. Chopra said.

A randomized controlled trial will be needed to understand the effects of statins on outcomes in patients with pneumonia, he said. The findings of the current meta-analyses are to be published in the American Journal of Medicine in October, he added.

The meta-analyses included 10 cohort studies (7 retrospective and 3 prospective), 2 case-control studies, and 1 randomized controlled trial published only as an abstract by Korean investigators who did not respond to requests for more information. "I have some doubts about this study," Dr. Chopra said.

The smallest study included 67 patients, and the largest had 121,254 patients. ("This is a nightmare to deal with" in a meta-analysis, he said.) Eight studies focused on hospitalized patients and five on outpatients. Four studies reported only in-hospital mortality, six reported 30-day mortality, two reported 60-day mortality, and one reported mortality 6 months after pneumonia diagnosis.

The variety in study designs and models limits the significance of the meta-analyses’ findings. The observational nature of meta-analyses and the source of data being observational studies also were limitations. In addition, restrictive inclusion criteria were a constraint: The meta-analyses excluded studies of influenza or ventilator-associated pneumonia because the investigators "wanted a pure cohort of community-acquired pneumonia," he said. Sepsis studies in which mortality could not be linked directly to pneumonia also were excluded.

Pneumonia is the eighth-leading cause of death in hospitalized patients. For hospitalists, "pneumonia is our bread and butter," Dr. Chopra said.

The advent of antibiotics greatly reduced mortality from pneumonia, but the drugs have nearly no effect on mortality in the first 5 days of treatment, he said. Sixty-six percent of deaths from pneumonia happen within 7 days of illness.

Inflammation may be an important factor. A recent study found a 15% reduction in the probability of hospital-acquired pneumonia after chest trauma if patients received hydrocortisone therapy (JAMA 2011;305:1242-3).

Statins have anti-inflammatory properties, and several recent studies have reported that statin users had lower risks of developing pneumonia or complications of pneumonia, or of dying of pneumonia (Respir. Res. 2005;6:82; Chest 2007;131:1006-12; Am. J. Med. 2008;121:1002-7; Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2009;18:697-703).

One study of 8,652 veterans found a 46% lower risk of 30-day mortality after pneumonia in statin users compared with nonusers (Eur. Respir. J. 2008;31:611-7).

Some experts have argued that these perceived benefits could all be due to confounding factors and methodological constraints in the studies, prompting the current study.

Dr. Chopra reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Statins may reduce mortality after pneumonia, but this possible benefit may weaken or disappear in important subgroups of patients, results of a double meta-analysis suggest.

The analyses of data from 13 studies including 254,950 adults with pneumonia found a significant 38% decreased likelihood of dying in patients who were on statins compared with non-statin users, before adjusting for confounding factors, Dr. Vineet Chopra and his associates reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

The investigators then pooled adjusted data from the studies accounting for the effects of various confounders, and found a combined reduction in the risk for death after pneumonia of 34% in statin users compared with nonusers, which also was statistically significant, said Dr. Chopra, a hospitalist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

He and his associates took it a step further, however, and conducted their own subgroup analyses of the studies’ data because of the heterogeneity of the studies and their patient populations, and because most studies used administrative data sets, which often don’t include the severity of illness and other important factors influencing mortality from pneumonia. Authors of 7 of the 13 studies provided unpublished data.

The subgroup analyses done by Dr. Chopra and his colleagues adjusted for the effects of smoking, vaccination status, severity of pneumonia, and whether the studies featured a score for the propensity of a patient to receive statins. They also looked at whether the studies included "uncommon covariates" such as time to antibiotic delivery, the presence of bacteremia, the presence of advance directives, the use of home health services, residence in a nursing home, and measures of frailty other than comorbidity indices.

"When we started teasing out from each model whether or not they adjusted for" any of these potential confounders and pooled the effects separately for each confounder, "any effect of statin use on mortality after pneumonia was completely eliminated," Dr. Chopra said.

A randomized controlled trial will be needed to understand the effects of statins on outcomes in patients with pneumonia, he said. The findings of the current meta-analyses are to be published in the American Journal of Medicine in October, he added.

The meta-analyses included 10 cohort studies (7 retrospective and 3 prospective), 2 case-control studies, and 1 randomized controlled trial published only as an abstract by Korean investigators who did not respond to requests for more information. "I have some doubts about this study," Dr. Chopra said.

The smallest study included 67 patients, and the largest had 121,254 patients. ("This is a nightmare to deal with" in a meta-analysis, he said.) Eight studies focused on hospitalized patients and five on outpatients. Four studies reported only in-hospital mortality, six reported 30-day mortality, two reported 60-day mortality, and one reported mortality 6 months after pneumonia diagnosis.

The variety in study designs and models limits the significance of the meta-analyses’ findings. The observational nature of meta-analyses and the source of data being observational studies also were limitations. In addition, restrictive inclusion criteria were a constraint: The meta-analyses excluded studies of influenza or ventilator-associated pneumonia because the investigators "wanted a pure cohort of community-acquired pneumonia," he said. Sepsis studies in which mortality could not be linked directly to pneumonia also were excluded.

Pneumonia is the eighth-leading cause of death in hospitalized patients. For hospitalists, "pneumonia is our bread and butter," Dr. Chopra said.

The advent of antibiotics greatly reduced mortality from pneumonia, but the drugs have nearly no effect on mortality in the first 5 days of treatment, he said. Sixty-six percent of deaths from pneumonia happen within 7 days of illness.

Inflammation may be an important factor. A recent study found a 15% reduction in the probability of hospital-acquired pneumonia after chest trauma if patients received hydrocortisone therapy (JAMA 2011;305:1242-3).

Statins have anti-inflammatory properties, and several recent studies have reported that statin users had lower risks of developing pneumonia or complications of pneumonia, or of dying of pneumonia (Respir. Res. 2005;6:82; Chest 2007;131:1006-12; Am. J. Med. 2008;121:1002-7; Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2009;18:697-703).

One study of 8,652 veterans found a 46% lower risk of 30-day mortality after pneumonia in statin users compared with nonusers (Eur. Respir. J. 2008;31:611-7).

Some experts have argued that these perceived benefits could all be due to confounding factors and methodological constraints in the studies, prompting the current study.

Dr. Chopra reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Statins may reduce mortality after pneumonia, but this possible benefit may weaken or disappear in important subgroups of patients, results of a double meta-analysis suggest.

The analyses of data from 13 studies including 254,950 adults with pneumonia found a significant 38% decreased likelihood of dying in patients who were on statins compared with non-statin users, before adjusting for confounding factors, Dr. Vineet Chopra and his associates reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

The investigators then pooled adjusted data from the studies accounting for the effects of various confounders, and found a combined reduction in the risk for death after pneumonia of 34% in statin users compared with nonusers, which also was statistically significant, said Dr. Chopra, a hospitalist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

He and his associates took it a step further, however, and conducted their own subgroup analyses of the studies’ data because of the heterogeneity of the studies and their patient populations, and because most studies used administrative data sets, which often don’t include the severity of illness and other important factors influencing mortality from pneumonia. Authors of 7 of the 13 studies provided unpublished data.

The subgroup analyses done by Dr. Chopra and his colleagues adjusted for the effects of smoking, vaccination status, severity of pneumonia, and whether the studies featured a score for the propensity of a patient to receive statins. They also looked at whether the studies included "uncommon covariates" such as time to antibiotic delivery, the presence of bacteremia, the presence of advance directives, the use of home health services, residence in a nursing home, and measures of frailty other than comorbidity indices.

"When we started teasing out from each model whether or not they adjusted for" any of these potential confounders and pooled the effects separately for each confounder, "any effect of statin use on mortality after pneumonia was completely eliminated," Dr. Chopra said.

A randomized controlled trial will be needed to understand the effects of statins on outcomes in patients with pneumonia, he said. The findings of the current meta-analyses are to be published in the American Journal of Medicine in October, he added.

The meta-analyses included 10 cohort studies (7 retrospective and 3 prospective), 2 case-control studies, and 1 randomized controlled trial published only as an abstract by Korean investigators who did not respond to requests for more information. "I have some doubts about this study," Dr. Chopra said.

The smallest study included 67 patients, and the largest had 121,254 patients. ("This is a nightmare to deal with" in a meta-analysis, he said.) Eight studies focused on hospitalized patients and five on outpatients. Four studies reported only in-hospital mortality, six reported 30-day mortality, two reported 60-day mortality, and one reported mortality 6 months after pneumonia diagnosis.

The variety in study designs and models limits the significance of the meta-analyses’ findings. The observational nature of meta-analyses and the source of data being observational studies also were limitations. In addition, restrictive inclusion criteria were a constraint: The meta-analyses excluded studies of influenza or ventilator-associated pneumonia because the investigators "wanted a pure cohort of community-acquired pneumonia," he said. Sepsis studies in which mortality could not be linked directly to pneumonia also were excluded.

Pneumonia is the eighth-leading cause of death in hospitalized patients. For hospitalists, "pneumonia is our bread and butter," Dr. Chopra said.

The advent of antibiotics greatly reduced mortality from pneumonia, but the drugs have nearly no effect on mortality in the first 5 days of treatment, he said. Sixty-six percent of deaths from pneumonia happen within 7 days of illness.