User login

European cholesterol guidelines push LDL targets below 55 mg/dL

PARIS – The 2019 dyslipidemia management guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology set an LDL cholesterol target for very-high-risk people of less than 55 mg/dL (as well as at least a 50% cut from baseline), a class I recommendation. This marks the first time a cardiology society has either recommended a target goal for this measure below 70 mg/dL or endorsed treating patients to still-lower cholesterol once their level was already under 70 mg/dL.*

The guidelines went further by suggesting consideration of an even lower treatment target for LDL-cholesterol in very-high-risk, secondary prevention patients who have already had at least two atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events during the past 2 years, a setting that could justify an LDL-cholesterol goal of less than 40 mg/dL (along with a cut from baseline of at least 50%), a class IIb recommendation that denotes a “may be considered,” endorsement.

“In all the trials, lower was better. There was no lower level of LDL cholesterol that’s been studied that was not better” for patient outcomes, Colin Baigent, BMBCH, said while presenting the new guideline at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). “It’s very clear” that the full treatment benefit from lowering LDL-cholesterol extends to getting very-high risk patients below these levels, said Dr. Baigent, professor of cardiology at Oxford (England) University and one of three chairs of the ESC’s dyslipidemia guideline-writing panel.

While this change was seen as a notably aggressive goal and too fixed on a specific number by at least one author of the 2018 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology cholesterol management guideline (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Jun;73[24]:e285-e350), it was embraced by another U.S. expert not involved in writing the most recent U.S. recommendations.

“A goal for LDL-cholesterol of less than 55 mg/dL is reasonable; it’s well documented” by trial evidence “and I support it,” said Robert H. Eckel, MD, an endocrinologist and professor of medicine at the University of Colorado in Aurora. Dr. Eckel added that he “also supports” an LDL-cholesterol of less than 40 mg/dL in very-high-risk patients with a history of multiple events or with multiple residual risk factors, and he said he has applied this lower LDL-cholesterol goal in his practice for selected patients. But Dr. Eckel acknowledged in an interview that the evidence for it was less clear-cut than was the evidence behind a goal of less than 55 mg/dL. He also supported the concept of including a treatment goal in U.S. lipid recommendations, which in recent versions has been missing. “I fall back on a cholesterol goal for practical purposes” of making the success of cholesterol-lowering treatment easier to track.

The new ESC goal was characterized as “arbitrary” by Neil J. Stone, MD, vice-chair of the panel that wrote the 2018 AHA/ACC guideline, which relied on treating secondary-prevention patients at high risk to an LDL-cholesterol at least 50% less than before treatment, and recommended continued intensification for patients whose LDL-cholesterol level remained at or above 70 mg/dL.

“If the patient is at 58 mg/dL I’m not sure anyone can tell me what the difference is,” compared with reaching less than 55 mg/dL, Dr. Stone said in an interview. “I worry about focusing on a number and not on the concept that people at the very highest risk deserve the most intensive treatment; the Europeans agree, but they have a different way of looking at it. Despite this difference in approach, the new ESC guidelines and the 2018 U.S. guideline “are more similar than different,” stressed Dr. Stone, professor of medicine and preventive medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago.

However, other experts see an important difference in the risk faced by patients who reach the ESC’s recommended treatment goals and those who fall just short.

“It’s hard to lower an LDL-cholesterol that is already relatively low. People who are close to their cholesterol target need the most intensified treatment” to reach their goal, said Rory Collins, F.Med.Sci., professor of epidemiology at Oxford University. He was not on the ESC guidelines panel.

“It’s a mind shift that clinicians need to be most aggressive in treating patients with the highest risk” even when their LDL-cholesterol is low but not yet at the target level, Dr. Collins said during a discussion session at the congress.

The new ESC guidelines is about “both getting the LDL-cholesterol down to a certain level and also about achieving a big [at least 50%] change” from baseline. “I think the ESC guidelines make that crystal clear,” said Marc S. Sabatine, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and the sole American to participate in the ESC guidelines-writing panel.

The ESC also broke new ground by advocating an aggressive path toward achieving these LDL-cholesterol goals by elevating the newest and most potent class of approved LDL-cholesterol-lowering drugs, the PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9) inhibitors, to a top-tier, class I recommendation (“is recommended”) for secondary prevention in very-high-risk patients not reaching their goal LDL-cholesterol level on a maximally tolerated statin plus ezetimibe. This recommendation to unequivocally add a PCSK9 inhibitor for this patient population contrasts with the 2018 AHA/ACC guideline that deemed adding a PCSK9 inhibitor a IIa recommendation (“is reasonable”).

A similar uptick in treatment aggressiveness appeared in the ESC’s recommendations for managing very-high-risk patients in a primary prevention setting, including those without familial hypercholesterolemia. For these people, the ESC panel, which worked in concert with the European Atherosclerosis Society, pegged adding a PCSK9 inhibitor as a IIb (“may be considered”) recommendation when these very-high-risk people fail to reach their LDL-cholesterol target on a maximally tolerated statin and ezetimibe. Once again, this opening to use a PCSK9 inhibitor contrasted with the 2018 U.S. guideline, which never mentioned an option of adding a PCSK9 inhibitor for primary prevention except when someone also has familial hypercholesterolemia and starts treatment with an LDL level of at least 190 mg/dL (a IIb recommendation). The new European guidelines proposed using a PCSK9 inhibitor as a second-line option to consider when needed for people whose very high risk derives primarily from older age and other factors such as smoking or hypertension that give them at least a 10% 10-year risk for cardiovascular death as estimated with the European-oriented SCORE risk calculator tables.

Updated SCORE risk designations appear in the new ESC dyslipidemia guidelines, and they show, for example, that in lower-risk European countries (mostly Western European nations) virtually all men who are at least 70 years old would fall into the very-high-risk category that makes them potential candidates for treatment with a PCSK9 inhibitor regardless of any other risk they may or may not have. In higher-risk (mostly Eastern European) countries this designation kicks in for most men once they reach the age of 65.

Several Congress attendees who came to a discussion session on the guidelines voiced concerns that the new revision will lead to substantially increased use of the these drugs and hence will significantly boost medical costs, because these drugs today are priced at about $6,000 annually to treat one patient. In response, members of the guideline-writing panel defended their decision as unavoidable given what’s been reported on the clinical impact of PCSK9 inhibitors when lowering LDL cholesterol and cutting atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events.

“I commend the [ESC] guideline for focusing on the science and on what is best for patients. The U.S. guidelines conflated the science and the cost, and the recommendations got watered down by cost considerations,” said Dr. Sabatine, who has led several studies of PCSK9 inhibitors.

Dr. Baigent added that the panel “deliberated long and hard on cost, but we felt that we had to focus on the evidence. The cost will shift” in the future, he predicted.

Other U.S. physicians highlighted the need to take drug cost into account when writing public health policy documents such as lipid-management guidelines and questioned whether this more liberal use of PCSK9 inhibitors was justified.

“I think that in the absence of familial hypercholesterolemia you need to waffle around the edges to justify a PCSK9 inhibitor,” said Dr. Eckel. “The cost of PCSK9 inhibitors has come down, but at $6,000 per year you can’t ignore their cost.”

“In the U.S. we need to be mindful of the cost of treatment,” said Dr. Stone. “The ESC guidelines are probably more aggressive” than the 2018 U.S. guideline. “They use PCSK9 inhibitors perhaps more than we do; we [in the United States] prefer generic ezetimibe. A lot has to do with the definitions of risk. The European guidelines have a lot of risk definitions that differ” from the U.S. guideline, he said.

Members of the ESC guidelines panel acknowledged that the SCORE risk-assessment charts could overestimate risk in older people who need primary prevention treatment, as well as underestimate the risk in younger adults.

This inherent age bias in the SCORE risk tables make it “extremely important to contextualize” a person’s risk “by considering other risk factors,” advised Brian A. Ference, MD, an interventional cardiologist and professor at Cambridge (England) University who was a member of the ESC guidelines writing group.

The new ESC guidelines say that risk categorization “must be interpreted in light of the clinician’s knowledge and experience, and of the patient’s pretest likelihood” of cardiovascular disease.”

Dr. Baigent has received research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, and Pfizer. Dr. Eckel has been an expert witness on behalf of Sanofi/Regeneron. Dr. Sabatine and Dr. Ference have received honoraria and research funding from several companies including those that market lipid-lowering drugs. Dr. Stone and Dr. Collins had no disclosures.

*Correction, 9/20/19: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the ESC guidelines were the first by a medical society to recommend the lower cholesterol goals. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists included targets below 55 mg/dL in their 2017 dyslipidemia management guidelines.

SOURCE: Mach F et al. Eur Heart J. 2019 Aug 31. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455.

The new ESC dyslipidemia guidelines recently presented at the society’s annual congress are a welcome addition to the lipid disorder treatment guidelines available to clinicians. These guidelines follow the groundbreaking recommendation in 2017 by AACE in their updated guidelines that introduced an LDL goal of <55 mg/dL in “extreme risk” patients. The ESC guidelines now also recommend an LDL goal of <55 mg/dL in “very-high-risk” patients but go further by also requiring a 50% reduction in LDL. Furthermore, they have established an LDL goal of <40 mg/dL in patients who experienced a second vascular event in the past 2 years while on maximally tolerated statin dose.

The ESC very-high-risk category shares many features with AACE’s extreme-risk category but is broader in that it includes patients without a clinical event who display unequivocal evidence of arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) on imaging and patients with severe chronic kidney disease (GFR <30 mL/min ) without known ASCVD. There are substantial differences between the ESC and AHA-ACC 2018 guidelines in the very-high-risk category. The AHA very-high-risk is directed toward secondary prevention only and requires two major ASCVD events or one major and at least two high-risk conditions. Moreover, elements of both major ASCVD events and high-risk conditions as well as the very-high-risk eligibility requirements could mean that some patients, who would clearly be classified by both ESC and AACE as candidates for an LDL goal of <55, may not qualify for threshold consideration for maximal LDL lowering below 70 mg/dL including the use of PCSK9 inhibitors. Relative to this point, the AHA-ACC guidelines do not classify past CABG or PCI as a major ASCVD event, nor is a TIA considered a major event or a high-risk condition.

For LDL, “lower is better” is supported by years of statin clinical trial evidence, along with the robust findings in the 2010 Cholesterol Trialists Collaboration. The goal of <55 mg/dL is supported by the IMPROVE-IT, FOURIER, and ODYSSEY trials. The ESC guidelines appropriately take this body of evidence and applies it to an aggressive treatment platform that, like AACE, sets clinically useful LDL goals for clinicians and patients. It takes early, aggressive LDL-lowering treatment to stay ahead of atherosclerotic plaque development in patients who are at very high or extreme risk. Following AACE’s lead, the ESC guidelines are the newest tool available to clinicians addressing this issue with the promise of further decreasing CVD events and extending lives.

Dr. Jellinger is a member of the editorial advisory board for Clinical Endocrinology News. He is professor of clinical medicine on the voluntary faculty at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and a practicing endocrinologist at The Center for Diabetes & Endocrine Care in Hollywood, Fla. He is past president of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American College of Endocrinology and was chair of the writing committee for the 2017 AACE-ACE lipid guidelines.

The new ESC dyslipidemia guidelines recently presented at the society’s annual congress are a welcome addition to the lipid disorder treatment guidelines available to clinicians. These guidelines follow the groundbreaking recommendation in 2017 by AACE in their updated guidelines that introduced an LDL goal of <55 mg/dL in “extreme risk” patients. The ESC guidelines now also recommend an LDL goal of <55 mg/dL in “very-high-risk” patients but go further by also requiring a 50% reduction in LDL. Furthermore, they have established an LDL goal of <40 mg/dL in patients who experienced a second vascular event in the past 2 years while on maximally tolerated statin dose.

The ESC very-high-risk category shares many features with AACE’s extreme-risk category but is broader in that it includes patients without a clinical event who display unequivocal evidence of arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) on imaging and patients with severe chronic kidney disease (GFR <30 mL/min ) without known ASCVD. There are substantial differences between the ESC and AHA-ACC 2018 guidelines in the very-high-risk category. The AHA very-high-risk is directed toward secondary prevention only and requires two major ASCVD events or one major and at least two high-risk conditions. Moreover, elements of both major ASCVD events and high-risk conditions as well as the very-high-risk eligibility requirements could mean that some patients, who would clearly be classified by both ESC and AACE as candidates for an LDL goal of <55, may not qualify for threshold consideration for maximal LDL lowering below 70 mg/dL including the use of PCSK9 inhibitors. Relative to this point, the AHA-ACC guidelines do not classify past CABG or PCI as a major ASCVD event, nor is a TIA considered a major event or a high-risk condition.

For LDL, “lower is better” is supported by years of statin clinical trial evidence, along with the robust findings in the 2010 Cholesterol Trialists Collaboration. The goal of <55 mg/dL is supported by the IMPROVE-IT, FOURIER, and ODYSSEY trials. The ESC guidelines appropriately take this body of evidence and applies it to an aggressive treatment platform that, like AACE, sets clinically useful LDL goals for clinicians and patients. It takes early, aggressive LDL-lowering treatment to stay ahead of atherosclerotic plaque development in patients who are at very high or extreme risk. Following AACE’s lead, the ESC guidelines are the newest tool available to clinicians addressing this issue with the promise of further decreasing CVD events and extending lives.

Dr. Jellinger is a member of the editorial advisory board for Clinical Endocrinology News. He is professor of clinical medicine on the voluntary faculty at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and a practicing endocrinologist at The Center for Diabetes & Endocrine Care in Hollywood, Fla. He is past president of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American College of Endocrinology and was chair of the writing committee for the 2017 AACE-ACE lipid guidelines.

The new ESC dyslipidemia guidelines recently presented at the society’s annual congress are a welcome addition to the lipid disorder treatment guidelines available to clinicians. These guidelines follow the groundbreaking recommendation in 2017 by AACE in their updated guidelines that introduced an LDL goal of <55 mg/dL in “extreme risk” patients. The ESC guidelines now also recommend an LDL goal of <55 mg/dL in “very-high-risk” patients but go further by also requiring a 50% reduction in LDL. Furthermore, they have established an LDL goal of <40 mg/dL in patients who experienced a second vascular event in the past 2 years while on maximally tolerated statin dose.

The ESC very-high-risk category shares many features with AACE’s extreme-risk category but is broader in that it includes patients without a clinical event who display unequivocal evidence of arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) on imaging and patients with severe chronic kidney disease (GFR <30 mL/min ) without known ASCVD. There are substantial differences between the ESC and AHA-ACC 2018 guidelines in the very-high-risk category. The AHA very-high-risk is directed toward secondary prevention only and requires two major ASCVD events or one major and at least two high-risk conditions. Moreover, elements of both major ASCVD events and high-risk conditions as well as the very-high-risk eligibility requirements could mean that some patients, who would clearly be classified by both ESC and AACE as candidates for an LDL goal of <55, may not qualify for threshold consideration for maximal LDL lowering below 70 mg/dL including the use of PCSK9 inhibitors. Relative to this point, the AHA-ACC guidelines do not classify past CABG or PCI as a major ASCVD event, nor is a TIA considered a major event or a high-risk condition.

For LDL, “lower is better” is supported by years of statin clinical trial evidence, along with the robust findings in the 2010 Cholesterol Trialists Collaboration. The goal of <55 mg/dL is supported by the IMPROVE-IT, FOURIER, and ODYSSEY trials. The ESC guidelines appropriately take this body of evidence and applies it to an aggressive treatment platform that, like AACE, sets clinically useful LDL goals for clinicians and patients. It takes early, aggressive LDL-lowering treatment to stay ahead of atherosclerotic plaque development in patients who are at very high or extreme risk. Following AACE’s lead, the ESC guidelines are the newest tool available to clinicians addressing this issue with the promise of further decreasing CVD events and extending lives.

Dr. Jellinger is a member of the editorial advisory board for Clinical Endocrinology News. He is professor of clinical medicine on the voluntary faculty at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and a practicing endocrinologist at The Center for Diabetes & Endocrine Care in Hollywood, Fla. He is past president of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American College of Endocrinology and was chair of the writing committee for the 2017 AACE-ACE lipid guidelines.

PARIS – The 2019 dyslipidemia management guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology set an LDL cholesterol target for very-high-risk people of less than 55 mg/dL (as well as at least a 50% cut from baseline), a class I recommendation. This marks the first time a cardiology society has either recommended a target goal for this measure below 70 mg/dL or endorsed treating patients to still-lower cholesterol once their level was already under 70 mg/dL.*

The guidelines went further by suggesting consideration of an even lower treatment target for LDL-cholesterol in very-high-risk, secondary prevention patients who have already had at least two atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events during the past 2 years, a setting that could justify an LDL-cholesterol goal of less than 40 mg/dL (along with a cut from baseline of at least 50%), a class IIb recommendation that denotes a “may be considered,” endorsement.

“In all the trials, lower was better. There was no lower level of LDL cholesterol that’s been studied that was not better” for patient outcomes, Colin Baigent, BMBCH, said while presenting the new guideline at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). “It’s very clear” that the full treatment benefit from lowering LDL-cholesterol extends to getting very-high risk patients below these levels, said Dr. Baigent, professor of cardiology at Oxford (England) University and one of three chairs of the ESC’s dyslipidemia guideline-writing panel.

While this change was seen as a notably aggressive goal and too fixed on a specific number by at least one author of the 2018 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology cholesterol management guideline (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Jun;73[24]:e285-e350), it was embraced by another U.S. expert not involved in writing the most recent U.S. recommendations.

“A goal for LDL-cholesterol of less than 55 mg/dL is reasonable; it’s well documented” by trial evidence “and I support it,” said Robert H. Eckel, MD, an endocrinologist and professor of medicine at the University of Colorado in Aurora. Dr. Eckel added that he “also supports” an LDL-cholesterol of less than 40 mg/dL in very-high-risk patients with a history of multiple events or with multiple residual risk factors, and he said he has applied this lower LDL-cholesterol goal in his practice for selected patients. But Dr. Eckel acknowledged in an interview that the evidence for it was less clear-cut than was the evidence behind a goal of less than 55 mg/dL. He also supported the concept of including a treatment goal in U.S. lipid recommendations, which in recent versions has been missing. “I fall back on a cholesterol goal for practical purposes” of making the success of cholesterol-lowering treatment easier to track.

The new ESC goal was characterized as “arbitrary” by Neil J. Stone, MD, vice-chair of the panel that wrote the 2018 AHA/ACC guideline, which relied on treating secondary-prevention patients at high risk to an LDL-cholesterol at least 50% less than before treatment, and recommended continued intensification for patients whose LDL-cholesterol level remained at or above 70 mg/dL.

“If the patient is at 58 mg/dL I’m not sure anyone can tell me what the difference is,” compared with reaching less than 55 mg/dL, Dr. Stone said in an interview. “I worry about focusing on a number and not on the concept that people at the very highest risk deserve the most intensive treatment; the Europeans agree, but they have a different way of looking at it. Despite this difference in approach, the new ESC guidelines and the 2018 U.S. guideline “are more similar than different,” stressed Dr. Stone, professor of medicine and preventive medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago.

However, other experts see an important difference in the risk faced by patients who reach the ESC’s recommended treatment goals and those who fall just short.

“It’s hard to lower an LDL-cholesterol that is already relatively low. People who are close to their cholesterol target need the most intensified treatment” to reach their goal, said Rory Collins, F.Med.Sci., professor of epidemiology at Oxford University. He was not on the ESC guidelines panel.

“It’s a mind shift that clinicians need to be most aggressive in treating patients with the highest risk” even when their LDL-cholesterol is low but not yet at the target level, Dr. Collins said during a discussion session at the congress.

The new ESC guidelines is about “both getting the LDL-cholesterol down to a certain level and also about achieving a big [at least 50%] change” from baseline. “I think the ESC guidelines make that crystal clear,” said Marc S. Sabatine, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and the sole American to participate in the ESC guidelines-writing panel.

The ESC also broke new ground by advocating an aggressive path toward achieving these LDL-cholesterol goals by elevating the newest and most potent class of approved LDL-cholesterol-lowering drugs, the PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9) inhibitors, to a top-tier, class I recommendation (“is recommended”) for secondary prevention in very-high-risk patients not reaching their goal LDL-cholesterol level on a maximally tolerated statin plus ezetimibe. This recommendation to unequivocally add a PCSK9 inhibitor for this patient population contrasts with the 2018 AHA/ACC guideline that deemed adding a PCSK9 inhibitor a IIa recommendation (“is reasonable”).

A similar uptick in treatment aggressiveness appeared in the ESC’s recommendations for managing very-high-risk patients in a primary prevention setting, including those without familial hypercholesterolemia. For these people, the ESC panel, which worked in concert with the European Atherosclerosis Society, pegged adding a PCSK9 inhibitor as a IIb (“may be considered”) recommendation when these very-high-risk people fail to reach their LDL-cholesterol target on a maximally tolerated statin and ezetimibe. Once again, this opening to use a PCSK9 inhibitor contrasted with the 2018 U.S. guideline, which never mentioned an option of adding a PCSK9 inhibitor for primary prevention except when someone also has familial hypercholesterolemia and starts treatment with an LDL level of at least 190 mg/dL (a IIb recommendation). The new European guidelines proposed using a PCSK9 inhibitor as a second-line option to consider when needed for people whose very high risk derives primarily from older age and other factors such as smoking or hypertension that give them at least a 10% 10-year risk for cardiovascular death as estimated with the European-oriented SCORE risk calculator tables.

Updated SCORE risk designations appear in the new ESC dyslipidemia guidelines, and they show, for example, that in lower-risk European countries (mostly Western European nations) virtually all men who are at least 70 years old would fall into the very-high-risk category that makes them potential candidates for treatment with a PCSK9 inhibitor regardless of any other risk they may or may not have. In higher-risk (mostly Eastern European) countries this designation kicks in for most men once they reach the age of 65.

Several Congress attendees who came to a discussion session on the guidelines voiced concerns that the new revision will lead to substantially increased use of the these drugs and hence will significantly boost medical costs, because these drugs today are priced at about $6,000 annually to treat one patient. In response, members of the guideline-writing panel defended their decision as unavoidable given what’s been reported on the clinical impact of PCSK9 inhibitors when lowering LDL cholesterol and cutting atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events.

“I commend the [ESC] guideline for focusing on the science and on what is best for patients. The U.S. guidelines conflated the science and the cost, and the recommendations got watered down by cost considerations,” said Dr. Sabatine, who has led several studies of PCSK9 inhibitors.

Dr. Baigent added that the panel “deliberated long and hard on cost, but we felt that we had to focus on the evidence. The cost will shift” in the future, he predicted.

Other U.S. physicians highlighted the need to take drug cost into account when writing public health policy documents such as lipid-management guidelines and questioned whether this more liberal use of PCSK9 inhibitors was justified.

“I think that in the absence of familial hypercholesterolemia you need to waffle around the edges to justify a PCSK9 inhibitor,” said Dr. Eckel. “The cost of PCSK9 inhibitors has come down, but at $6,000 per year you can’t ignore their cost.”

“In the U.S. we need to be mindful of the cost of treatment,” said Dr. Stone. “The ESC guidelines are probably more aggressive” than the 2018 U.S. guideline. “They use PCSK9 inhibitors perhaps more than we do; we [in the United States] prefer generic ezetimibe. A lot has to do with the definitions of risk. The European guidelines have a lot of risk definitions that differ” from the U.S. guideline, he said.

Members of the ESC guidelines panel acknowledged that the SCORE risk-assessment charts could overestimate risk in older people who need primary prevention treatment, as well as underestimate the risk in younger adults.

This inherent age bias in the SCORE risk tables make it “extremely important to contextualize” a person’s risk “by considering other risk factors,” advised Brian A. Ference, MD, an interventional cardiologist and professor at Cambridge (England) University who was a member of the ESC guidelines writing group.

The new ESC guidelines say that risk categorization “must be interpreted in light of the clinician’s knowledge and experience, and of the patient’s pretest likelihood” of cardiovascular disease.”

Dr. Baigent has received research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, and Pfizer. Dr. Eckel has been an expert witness on behalf of Sanofi/Regeneron. Dr. Sabatine and Dr. Ference have received honoraria and research funding from several companies including those that market lipid-lowering drugs. Dr. Stone and Dr. Collins had no disclosures.

*Correction, 9/20/19: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the ESC guidelines were the first by a medical society to recommend the lower cholesterol goals. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists included targets below 55 mg/dL in their 2017 dyslipidemia management guidelines.

SOURCE: Mach F et al. Eur Heart J. 2019 Aug 31. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455.

PARIS – The 2019 dyslipidemia management guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology set an LDL cholesterol target for very-high-risk people of less than 55 mg/dL (as well as at least a 50% cut from baseline), a class I recommendation. This marks the first time a cardiology society has either recommended a target goal for this measure below 70 mg/dL or endorsed treating patients to still-lower cholesterol once their level was already under 70 mg/dL.*

The guidelines went further by suggesting consideration of an even lower treatment target for LDL-cholesterol in very-high-risk, secondary prevention patients who have already had at least two atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events during the past 2 years, a setting that could justify an LDL-cholesterol goal of less than 40 mg/dL (along with a cut from baseline of at least 50%), a class IIb recommendation that denotes a “may be considered,” endorsement.

“In all the trials, lower was better. There was no lower level of LDL cholesterol that’s been studied that was not better” for patient outcomes, Colin Baigent, BMBCH, said while presenting the new guideline at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). “It’s very clear” that the full treatment benefit from lowering LDL-cholesterol extends to getting very-high risk patients below these levels, said Dr. Baigent, professor of cardiology at Oxford (England) University and one of three chairs of the ESC’s dyslipidemia guideline-writing panel.

While this change was seen as a notably aggressive goal and too fixed on a specific number by at least one author of the 2018 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology cholesterol management guideline (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Jun;73[24]:e285-e350), it was embraced by another U.S. expert not involved in writing the most recent U.S. recommendations.

“A goal for LDL-cholesterol of less than 55 mg/dL is reasonable; it’s well documented” by trial evidence “and I support it,” said Robert H. Eckel, MD, an endocrinologist and professor of medicine at the University of Colorado in Aurora. Dr. Eckel added that he “also supports” an LDL-cholesterol of less than 40 mg/dL in very-high-risk patients with a history of multiple events or with multiple residual risk factors, and he said he has applied this lower LDL-cholesterol goal in his practice for selected patients. But Dr. Eckel acknowledged in an interview that the evidence for it was less clear-cut than was the evidence behind a goal of less than 55 mg/dL. He also supported the concept of including a treatment goal in U.S. lipid recommendations, which in recent versions has been missing. “I fall back on a cholesterol goal for practical purposes” of making the success of cholesterol-lowering treatment easier to track.

The new ESC goal was characterized as “arbitrary” by Neil J. Stone, MD, vice-chair of the panel that wrote the 2018 AHA/ACC guideline, which relied on treating secondary-prevention patients at high risk to an LDL-cholesterol at least 50% less than before treatment, and recommended continued intensification for patients whose LDL-cholesterol level remained at or above 70 mg/dL.

“If the patient is at 58 mg/dL I’m not sure anyone can tell me what the difference is,” compared with reaching less than 55 mg/dL, Dr. Stone said in an interview. “I worry about focusing on a number and not on the concept that people at the very highest risk deserve the most intensive treatment; the Europeans agree, but they have a different way of looking at it. Despite this difference in approach, the new ESC guidelines and the 2018 U.S. guideline “are more similar than different,” stressed Dr. Stone, professor of medicine and preventive medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago.

However, other experts see an important difference in the risk faced by patients who reach the ESC’s recommended treatment goals and those who fall just short.

“It’s hard to lower an LDL-cholesterol that is already relatively low. People who are close to their cholesterol target need the most intensified treatment” to reach their goal, said Rory Collins, F.Med.Sci., professor of epidemiology at Oxford University. He was not on the ESC guidelines panel.

“It’s a mind shift that clinicians need to be most aggressive in treating patients with the highest risk” even when their LDL-cholesterol is low but not yet at the target level, Dr. Collins said during a discussion session at the congress.

The new ESC guidelines is about “both getting the LDL-cholesterol down to a certain level and also about achieving a big [at least 50%] change” from baseline. “I think the ESC guidelines make that crystal clear,” said Marc S. Sabatine, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and the sole American to participate in the ESC guidelines-writing panel.

The ESC also broke new ground by advocating an aggressive path toward achieving these LDL-cholesterol goals by elevating the newest and most potent class of approved LDL-cholesterol-lowering drugs, the PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9) inhibitors, to a top-tier, class I recommendation (“is recommended”) for secondary prevention in very-high-risk patients not reaching their goal LDL-cholesterol level on a maximally tolerated statin plus ezetimibe. This recommendation to unequivocally add a PCSK9 inhibitor for this patient population contrasts with the 2018 AHA/ACC guideline that deemed adding a PCSK9 inhibitor a IIa recommendation (“is reasonable”).

A similar uptick in treatment aggressiveness appeared in the ESC’s recommendations for managing very-high-risk patients in a primary prevention setting, including those without familial hypercholesterolemia. For these people, the ESC panel, which worked in concert with the European Atherosclerosis Society, pegged adding a PCSK9 inhibitor as a IIb (“may be considered”) recommendation when these very-high-risk people fail to reach their LDL-cholesterol target on a maximally tolerated statin and ezetimibe. Once again, this opening to use a PCSK9 inhibitor contrasted with the 2018 U.S. guideline, which never mentioned an option of adding a PCSK9 inhibitor for primary prevention except when someone also has familial hypercholesterolemia and starts treatment with an LDL level of at least 190 mg/dL (a IIb recommendation). The new European guidelines proposed using a PCSK9 inhibitor as a second-line option to consider when needed for people whose very high risk derives primarily from older age and other factors such as smoking or hypertension that give them at least a 10% 10-year risk for cardiovascular death as estimated with the European-oriented SCORE risk calculator tables.

Updated SCORE risk designations appear in the new ESC dyslipidemia guidelines, and they show, for example, that in lower-risk European countries (mostly Western European nations) virtually all men who are at least 70 years old would fall into the very-high-risk category that makes them potential candidates for treatment with a PCSK9 inhibitor regardless of any other risk they may or may not have. In higher-risk (mostly Eastern European) countries this designation kicks in for most men once they reach the age of 65.

Several Congress attendees who came to a discussion session on the guidelines voiced concerns that the new revision will lead to substantially increased use of the these drugs and hence will significantly boost medical costs, because these drugs today are priced at about $6,000 annually to treat one patient. In response, members of the guideline-writing panel defended their decision as unavoidable given what’s been reported on the clinical impact of PCSK9 inhibitors when lowering LDL cholesterol and cutting atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events.

“I commend the [ESC] guideline for focusing on the science and on what is best for patients. The U.S. guidelines conflated the science and the cost, and the recommendations got watered down by cost considerations,” said Dr. Sabatine, who has led several studies of PCSK9 inhibitors.

Dr. Baigent added that the panel “deliberated long and hard on cost, but we felt that we had to focus on the evidence. The cost will shift” in the future, he predicted.

Other U.S. physicians highlighted the need to take drug cost into account when writing public health policy documents such as lipid-management guidelines and questioned whether this more liberal use of PCSK9 inhibitors was justified.

“I think that in the absence of familial hypercholesterolemia you need to waffle around the edges to justify a PCSK9 inhibitor,” said Dr. Eckel. “The cost of PCSK9 inhibitors has come down, but at $6,000 per year you can’t ignore their cost.”

“In the U.S. we need to be mindful of the cost of treatment,” said Dr. Stone. “The ESC guidelines are probably more aggressive” than the 2018 U.S. guideline. “They use PCSK9 inhibitors perhaps more than we do; we [in the United States] prefer generic ezetimibe. A lot has to do with the definitions of risk. The European guidelines have a lot of risk definitions that differ” from the U.S. guideline, he said.

Members of the ESC guidelines panel acknowledged that the SCORE risk-assessment charts could overestimate risk in older people who need primary prevention treatment, as well as underestimate the risk in younger adults.

This inherent age bias in the SCORE risk tables make it “extremely important to contextualize” a person’s risk “by considering other risk factors,” advised Brian A. Ference, MD, an interventional cardiologist and professor at Cambridge (England) University who was a member of the ESC guidelines writing group.

The new ESC guidelines say that risk categorization “must be interpreted in light of the clinician’s knowledge and experience, and of the patient’s pretest likelihood” of cardiovascular disease.”

Dr. Baigent has received research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, and Pfizer. Dr. Eckel has been an expert witness on behalf of Sanofi/Regeneron. Dr. Sabatine and Dr. Ference have received honoraria and research funding from several companies including those that market lipid-lowering drugs. Dr. Stone and Dr. Collins had no disclosures.

*Correction, 9/20/19: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the ESC guidelines were the first by a medical society to recommend the lower cholesterol goals. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists included targets below 55 mg/dL in their 2017 dyslipidemia management guidelines.

SOURCE: Mach F et al. Eur Heart J. 2019 Aug 31. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455.

REPORTING FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2019

Survival at ‘overweight’ BMI surpasses ‘normal’

PARIS – Middle-aged adults with a body mass index of 25-29 kg/m2 had a significantly better adjusted survival during a median follow-up of nearly 10 years than did people with a “normal” body mass index of 20-24 kg/m2 in a worldwide study of more than 140,000. This finding suggests the current, widely accepted definition of normal body mass index is wrong.*

The new findings suggest that the current definition of a “healthy” body mass index (BMI) “should be re-evaluated,” Darryl P. Leong, MBBS, said at the annual Congress of the European Society of Cardiology. The analysis also identified a BMI specifically of 27 kg/m2 as associated with optimal survival among both women and men, “clearly outside the range of 20 to less than 25 kg/m2 that is considered normal,” said Dr. Leong, a cardiologist at McMaster University and the Population Health Research Institute, both in Hamilton, Ont.

Dr. Leong cited three potential explanations for why the new study identified optimal survival with a BMI of 25 to less than 30 kg/m2 among people who were 35-70 years old when they entered the study and were followed for a median of 9.5 years: The current study collected data and adjusted the results using a wider range of potential confounders than in prior studies, the data reflect the impact of contemporary interventions to reduce cardiovascular disease illness and death while past studies relied on data from earlier times when less cardiovascular disease protection occurred, and the current study included people from lower-income countries, although the finding is just as applicable to people who live in high-income countries, who were also included in the study population, noted Salim Yusuf, MBBS, principal investigator for the study.

A BMI of 20-24 kg/m2 “is actually low and harmful,” noted Dr. Yusuf in an interview. Despite recent data consistently showing better survival among people with a BMI of 25-29 kg/m2, panels that have recently written weight guidelines are “ossified” and “refuse to accept” the implications of these findings, said Dr. Yusuf, professor of medicine at McMaster and executive director of the Population Health Research Institute.

The results of the analyses that Dr. Leong reported also showed that BMI paled as a prognosticator for survival when compared with two other assessments of weight: waist/hip ratio, and even more powerful prognostically, a novel measure developed for this analysis that calculates the ratio of hand-grip strength/body weight. Waist/hip ratio adds the dimension of the location of body fat rather than just the amount, and the ratio of grip strength/body weight assesses the contribution of muscle mass to overall weight, noted Dr. Leong. He reported an optimal waist/hip ratio for survival of 0.83 in women and 0.93 in men, and an optimal strength/weight ratio of 0.42 in women and 0.50 in men. This means that a man whose hand-grip strength (measured in kg) is half of the person’s body weight has the best prospect for survival.

The study used data collected in PURE (Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology Study) on 142,410 people aged 35-70 years from any one of four high-income countries, 12 middle-income countries, and five low-income countries. The study excluded people who had at baseline known coronary artery disease, stroke, heart failure, or cancer, and the adjusted analysis controlled for age, sex, region, education, activity, alcohol and tobacco use, and the baseline prevalence of hypertension and diabetes. During follow-up, 9,712 of these people died.

The researchers saw a nadir for mortality among people with a BMI of 25-29 kg/m2 for both cardiovascular and noncardiovascular deaths. In addition, the link between total mortality and BMI was strongest in the subgroup of people on one or more treatments aimed at preventing cardiovascular disease, while it essentially disappeared among people not receiving any cardiovascular disease preventive measures, highlighting that the relationship now identified depends on a context of overall cardiovascular disease risk reduction, Dr. Leong said. The results also showed a very clear, direct, linear relationship between higher BMI and both the incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular disease, as well as increased all-cause and noncardiovascular mortality among people with a BMI of less than 20 kg/m2.

Dr. Yusuf discussed the results of the analysis in a video interview.

The PURE study has received partial funding from unrestricted grants from several drug companies. Dr. Leong has been an advisor to Ferring Pharmaceuticals and has been a speaker on behalf of Janssen. Dr. Yusuf had no disclosures.

This story was updated 9/19/2019.

PARIS – Middle-aged adults with a body mass index of 25-29 kg/m2 had a significantly better adjusted survival during a median follow-up of nearly 10 years than did people with a “normal” body mass index of 20-24 kg/m2 in a worldwide study of more than 140,000. This finding suggests the current, widely accepted definition of normal body mass index is wrong.*

The new findings suggest that the current definition of a “healthy” body mass index (BMI) “should be re-evaluated,” Darryl P. Leong, MBBS, said at the annual Congress of the European Society of Cardiology. The analysis also identified a BMI specifically of 27 kg/m2 as associated with optimal survival among both women and men, “clearly outside the range of 20 to less than 25 kg/m2 that is considered normal,” said Dr. Leong, a cardiologist at McMaster University and the Population Health Research Institute, both in Hamilton, Ont.

Dr. Leong cited three potential explanations for why the new study identified optimal survival with a BMI of 25 to less than 30 kg/m2 among people who were 35-70 years old when they entered the study and were followed for a median of 9.5 years: The current study collected data and adjusted the results using a wider range of potential confounders than in prior studies, the data reflect the impact of contemporary interventions to reduce cardiovascular disease illness and death while past studies relied on data from earlier times when less cardiovascular disease protection occurred, and the current study included people from lower-income countries, although the finding is just as applicable to people who live in high-income countries, who were also included in the study population, noted Salim Yusuf, MBBS, principal investigator for the study.

A BMI of 20-24 kg/m2 “is actually low and harmful,” noted Dr. Yusuf in an interview. Despite recent data consistently showing better survival among people with a BMI of 25-29 kg/m2, panels that have recently written weight guidelines are “ossified” and “refuse to accept” the implications of these findings, said Dr. Yusuf, professor of medicine at McMaster and executive director of the Population Health Research Institute.

The results of the analyses that Dr. Leong reported also showed that BMI paled as a prognosticator for survival when compared with two other assessments of weight: waist/hip ratio, and even more powerful prognostically, a novel measure developed for this analysis that calculates the ratio of hand-grip strength/body weight. Waist/hip ratio adds the dimension of the location of body fat rather than just the amount, and the ratio of grip strength/body weight assesses the contribution of muscle mass to overall weight, noted Dr. Leong. He reported an optimal waist/hip ratio for survival of 0.83 in women and 0.93 in men, and an optimal strength/weight ratio of 0.42 in women and 0.50 in men. This means that a man whose hand-grip strength (measured in kg) is half of the person’s body weight has the best prospect for survival.

The study used data collected in PURE (Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology Study) on 142,410 people aged 35-70 years from any one of four high-income countries, 12 middle-income countries, and five low-income countries. The study excluded people who had at baseline known coronary artery disease, stroke, heart failure, or cancer, and the adjusted analysis controlled for age, sex, region, education, activity, alcohol and tobacco use, and the baseline prevalence of hypertension and diabetes. During follow-up, 9,712 of these people died.

The researchers saw a nadir for mortality among people with a BMI of 25-29 kg/m2 for both cardiovascular and noncardiovascular deaths. In addition, the link between total mortality and BMI was strongest in the subgroup of people on one or more treatments aimed at preventing cardiovascular disease, while it essentially disappeared among people not receiving any cardiovascular disease preventive measures, highlighting that the relationship now identified depends on a context of overall cardiovascular disease risk reduction, Dr. Leong said. The results also showed a very clear, direct, linear relationship between higher BMI and both the incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular disease, as well as increased all-cause and noncardiovascular mortality among people with a BMI of less than 20 kg/m2.

Dr. Yusuf discussed the results of the analysis in a video interview.

The PURE study has received partial funding from unrestricted grants from several drug companies. Dr. Leong has been an advisor to Ferring Pharmaceuticals and has been a speaker on behalf of Janssen. Dr. Yusuf had no disclosures.

This story was updated 9/19/2019.

PARIS – Middle-aged adults with a body mass index of 25-29 kg/m2 had a significantly better adjusted survival during a median follow-up of nearly 10 years than did people with a “normal” body mass index of 20-24 kg/m2 in a worldwide study of more than 140,000. This finding suggests the current, widely accepted definition of normal body mass index is wrong.*

The new findings suggest that the current definition of a “healthy” body mass index (BMI) “should be re-evaluated,” Darryl P. Leong, MBBS, said at the annual Congress of the European Society of Cardiology. The analysis also identified a BMI specifically of 27 kg/m2 as associated with optimal survival among both women and men, “clearly outside the range of 20 to less than 25 kg/m2 that is considered normal,” said Dr. Leong, a cardiologist at McMaster University and the Population Health Research Institute, both in Hamilton, Ont.

Dr. Leong cited three potential explanations for why the new study identified optimal survival with a BMI of 25 to less than 30 kg/m2 among people who were 35-70 years old when they entered the study and were followed for a median of 9.5 years: The current study collected data and adjusted the results using a wider range of potential confounders than in prior studies, the data reflect the impact of contemporary interventions to reduce cardiovascular disease illness and death while past studies relied on data from earlier times when less cardiovascular disease protection occurred, and the current study included people from lower-income countries, although the finding is just as applicable to people who live in high-income countries, who were also included in the study population, noted Salim Yusuf, MBBS, principal investigator for the study.

A BMI of 20-24 kg/m2 “is actually low and harmful,” noted Dr. Yusuf in an interview. Despite recent data consistently showing better survival among people with a BMI of 25-29 kg/m2, panels that have recently written weight guidelines are “ossified” and “refuse to accept” the implications of these findings, said Dr. Yusuf, professor of medicine at McMaster and executive director of the Population Health Research Institute.

The results of the analyses that Dr. Leong reported also showed that BMI paled as a prognosticator for survival when compared with two other assessments of weight: waist/hip ratio, and even more powerful prognostically, a novel measure developed for this analysis that calculates the ratio of hand-grip strength/body weight. Waist/hip ratio adds the dimension of the location of body fat rather than just the amount, and the ratio of grip strength/body weight assesses the contribution of muscle mass to overall weight, noted Dr. Leong. He reported an optimal waist/hip ratio for survival of 0.83 in women and 0.93 in men, and an optimal strength/weight ratio of 0.42 in women and 0.50 in men. This means that a man whose hand-grip strength (measured in kg) is half of the person’s body weight has the best prospect for survival.

The study used data collected in PURE (Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology Study) on 142,410 people aged 35-70 years from any one of four high-income countries, 12 middle-income countries, and five low-income countries. The study excluded people who had at baseline known coronary artery disease, stroke, heart failure, or cancer, and the adjusted analysis controlled for age, sex, region, education, activity, alcohol and tobacco use, and the baseline prevalence of hypertension and diabetes. During follow-up, 9,712 of these people died.

The researchers saw a nadir for mortality among people with a BMI of 25-29 kg/m2 for both cardiovascular and noncardiovascular deaths. In addition, the link between total mortality and BMI was strongest in the subgroup of people on one or more treatments aimed at preventing cardiovascular disease, while it essentially disappeared among people not receiving any cardiovascular disease preventive measures, highlighting that the relationship now identified depends on a context of overall cardiovascular disease risk reduction, Dr. Leong said. The results also showed a very clear, direct, linear relationship between higher BMI and both the incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular disease, as well as increased all-cause and noncardiovascular mortality among people with a BMI of less than 20 kg/m2.

Dr. Yusuf discussed the results of the analysis in a video interview.

The PURE study has received partial funding from unrestricted grants from several drug companies. Dr. Leong has been an advisor to Ferring Pharmaceuticals and has been a speaker on behalf of Janssen. Dr. Yusuf had no disclosures.

This story was updated 9/19/2019.

REPORTING FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2019

siRNA drug safely halved LDL cholesterol in phase 3 ORION-11

PARIS – A small interfering RNA drug, inclisiran, safely halved LDL cholesterol levels in more than 800 patients in a phase 3, multicenter study, in a big step toward this drug coming onto the market and offering an alternative way to harness the potent cholesterol-lowering power of PCSK9 inhibition.

In the reported study – which enrolled patients with established cardiovascular disease, familial hypercholesterolemia, type 2 diabetes, or a high Framingham Risk Score – participants received inclisiran as a semiannual subcutaneous injection. The safe efficacy this produced showed the viability of a new way to deliver lipid-lowering therapy that guarantees compliance and is convenient for patients.

The prospect of lowering cholesterol with about the same potency as the monoclonal antibodies that block PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9) activity but administered as a biannual injection “enables provider control over medication adherence, and may offer patients a meaningful new choice that is safe and convenient and has assured results,” Kausik K. Ray, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. The durable effect of the small interfering RNA (siRNA) agent “offers a huge advantage,” and “opens the field,” said Dr. Ray, a cardiologist and professor of public health at Imperial College, London.

He also highlighted the “excellent” safety profile seen in the 811 patients treated with inclisiran, compared with 804 patients in the study who received placebo. After four total injections of inclisiran spaced out over 450 days (about 15 months), the rate of treatment-emergent adverse events and serious events was virtually the same in the two treatment arms, and with no signal of inclisiran causing liver effects, renal or muscle injury, damage to blood components, or malignancy. The serial treatment with inclisiran that patients received – at baseline, 90, 270, and 450 days – produced no severe injection-site reactions, and transient mild or moderate injection-site reactions in just under 5% of patients.

Safety issues, such as more-severe injection-site reactions, thrombocytopenia, hepatotoxicity, and flu-like symptoms, plagued siRNA drugs during their earlier days of development, but more recently next-generation siRNA drugs with modified structures have produced much better safety performance, noted Richard C. Becker, MD, professor of medicine and director of the Heart, Lung, & Vascular Institute at the University of Cincinnati. The new-generation siRNAs such as inclisiran are “very well tolerated,” he said in an interview.

The Food and Drug Administration approved the first siRNA drug in August 2018, and in the year since then a few others have also come onto the U.S. market, Dr. Becker said.

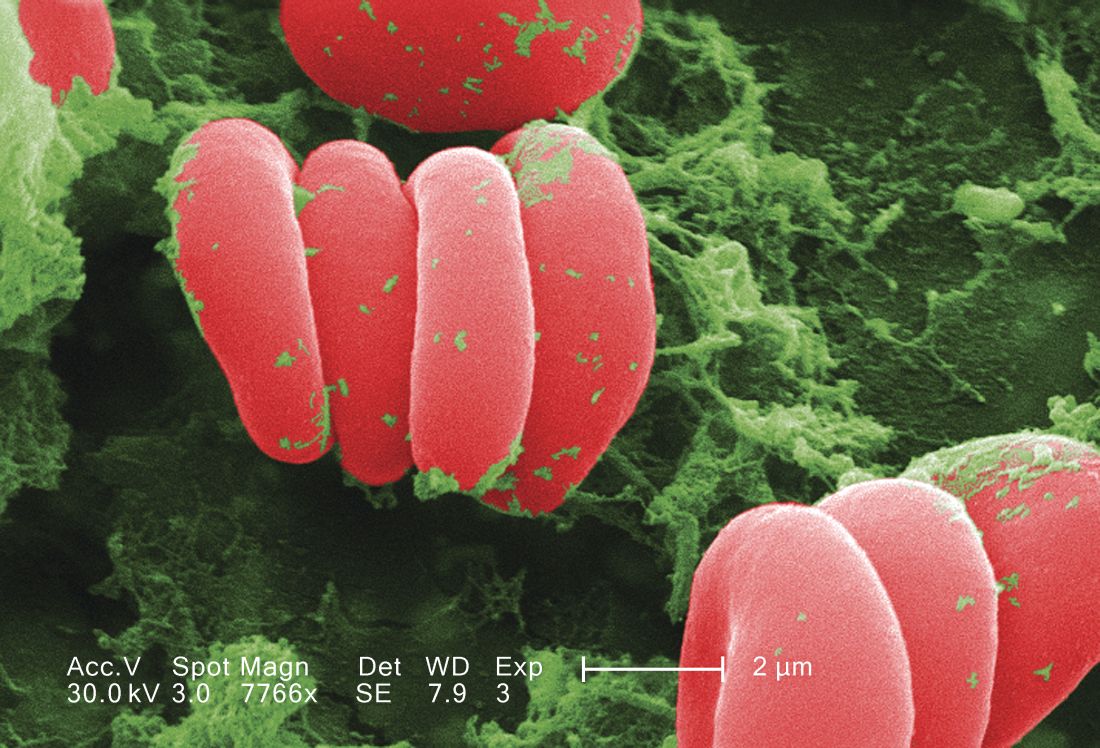

Like other siRNA drugs, the activity of inclisiran comes from a short RNA segment that is antisense to a particular messenger RNA (mRNA) target. In the case of inclisiran, the target is the mRNA for the PCSK9 enzyme produced in hepatocytes, and that decreases the number of LDL cholesterol receptors on the cell’s surface. When the antisense RNA molecule encounters a PCSK9 mRNA, the two bind and the mRNA is then degraded by a normal cell process. This cuts the cell’s production of the PCSK9 protein, resulting in more LDL cholesterol receptors on the cell’s surface that pull more LDL cholesterol from the blood. The blocking of PCSK9 activity by inclisiran is roughly equivalent to the action of the PCSK9 monoclonal antibodies that have now been on the U.S. market for a few years. Also like other siRNA drugs, the RNA of inclisiran is packaged so that, once injected into a patient, the RNA molecules travel to the liver and enter hepatocytes, where they exert their activity.

“No one has concerns about inclisiran being able to lower LDL [cholesterol], and there have been no safety signals. The data we have seen so far look very reassuring, and in particular has been very safe for the liver,” commented Marc S. Sabatine, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, who has led several studies involving PCSK9-targeted drugs and is helping to run ORION-4, a 15,000-patient study of inclisiran designed to assess the drug’s effect on clinical events. Results from ORION-4 are not expected until about 2024.

“The PCSK9 inhibitors in general have been a huge advance for patients, and the more kinds of drugs we have to target PCSK9, the better,” he said in an interview.

The study reported by Dr. Ray, ORION-11, enrolled 1,617 patients with high atherosclerotic disease risk at 70 sites in six European countries and South Africa. The study’s primary efficacy endpoint was reduction from baseline in LDL cholesterol both at 510 days (about 17 months) after the first dose and also throughout the 15-month period that started 3 months after the first dose. The average reduction seen after 510 days was 54%, compared with baseline, and the time-averaged reduction during the 15-month window examined was 50%, Dr. Ray said. The results also showed a consistent reduction in LDL cholesterol in virtually every patient treated with inclisiran.

Two other phase 3 studies of inclisiran with similar design have been completed, and the results will come out before the end of 2019, according to a statement from the Medicines Company, which is developing the drug. The statement also said that the company plans to file their data with the FDA for marketing approval for inclisiran before the end of 2019. In the recent past, the FDA has approved drugs for the indication of lowering LDL cholesterol before evidence is available to prove that the agent has benefits for reducing clinical events.

Future studies of inclisiran will explore the efficacy of a single annual injection of the drug as an approach to primary prevention of cardiovascular disease, Dr. Ray said.

ORION-11 was sponsored by the Medicines Company. Dr. Ray is a consultant to it and to several other companies. Dr. Becker had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Sabatine has received research support from the Medicines Company and several other companies, and has received personal fees from Anthos Therapeutics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CVS Caremark, Daiichi Sankyo, DalCor Pharmaceuticals, Dyrnamix, and Ionis.

PARIS – A small interfering RNA drug, inclisiran, safely halved LDL cholesterol levels in more than 800 patients in a phase 3, multicenter study, in a big step toward this drug coming onto the market and offering an alternative way to harness the potent cholesterol-lowering power of PCSK9 inhibition.

In the reported study – which enrolled patients with established cardiovascular disease, familial hypercholesterolemia, type 2 diabetes, or a high Framingham Risk Score – participants received inclisiran as a semiannual subcutaneous injection. The safe efficacy this produced showed the viability of a new way to deliver lipid-lowering therapy that guarantees compliance and is convenient for patients.

The prospect of lowering cholesterol with about the same potency as the monoclonal antibodies that block PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9) activity but administered as a biannual injection “enables provider control over medication adherence, and may offer patients a meaningful new choice that is safe and convenient and has assured results,” Kausik K. Ray, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. The durable effect of the small interfering RNA (siRNA) agent “offers a huge advantage,” and “opens the field,” said Dr. Ray, a cardiologist and professor of public health at Imperial College, London.

He also highlighted the “excellent” safety profile seen in the 811 patients treated with inclisiran, compared with 804 patients in the study who received placebo. After four total injections of inclisiran spaced out over 450 days (about 15 months), the rate of treatment-emergent adverse events and serious events was virtually the same in the two treatment arms, and with no signal of inclisiran causing liver effects, renal or muscle injury, damage to blood components, or malignancy. The serial treatment with inclisiran that patients received – at baseline, 90, 270, and 450 days – produced no severe injection-site reactions, and transient mild or moderate injection-site reactions in just under 5% of patients.

Safety issues, such as more-severe injection-site reactions, thrombocytopenia, hepatotoxicity, and flu-like symptoms, plagued siRNA drugs during their earlier days of development, but more recently next-generation siRNA drugs with modified structures have produced much better safety performance, noted Richard C. Becker, MD, professor of medicine and director of the Heart, Lung, & Vascular Institute at the University of Cincinnati. The new-generation siRNAs such as inclisiran are “very well tolerated,” he said in an interview.

The Food and Drug Administration approved the first siRNA drug in August 2018, and in the year since then a few others have also come onto the U.S. market, Dr. Becker said.

Like other siRNA drugs, the activity of inclisiran comes from a short RNA segment that is antisense to a particular messenger RNA (mRNA) target. In the case of inclisiran, the target is the mRNA for the PCSK9 enzyme produced in hepatocytes, and that decreases the number of LDL cholesterol receptors on the cell’s surface. When the antisense RNA molecule encounters a PCSK9 mRNA, the two bind and the mRNA is then degraded by a normal cell process. This cuts the cell’s production of the PCSK9 protein, resulting in more LDL cholesterol receptors on the cell’s surface that pull more LDL cholesterol from the blood. The blocking of PCSK9 activity by inclisiran is roughly equivalent to the action of the PCSK9 monoclonal antibodies that have now been on the U.S. market for a few years. Also like other siRNA drugs, the RNA of inclisiran is packaged so that, once injected into a patient, the RNA molecules travel to the liver and enter hepatocytes, where they exert their activity.

“No one has concerns about inclisiran being able to lower LDL [cholesterol], and there have been no safety signals. The data we have seen so far look very reassuring, and in particular has been very safe for the liver,” commented Marc S. Sabatine, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, who has led several studies involving PCSK9-targeted drugs and is helping to run ORION-4, a 15,000-patient study of inclisiran designed to assess the drug’s effect on clinical events. Results from ORION-4 are not expected until about 2024.

“The PCSK9 inhibitors in general have been a huge advance for patients, and the more kinds of drugs we have to target PCSK9, the better,” he said in an interview.

The study reported by Dr. Ray, ORION-11, enrolled 1,617 patients with high atherosclerotic disease risk at 70 sites in six European countries and South Africa. The study’s primary efficacy endpoint was reduction from baseline in LDL cholesterol both at 510 days (about 17 months) after the first dose and also throughout the 15-month period that started 3 months after the first dose. The average reduction seen after 510 days was 54%, compared with baseline, and the time-averaged reduction during the 15-month window examined was 50%, Dr. Ray said. The results also showed a consistent reduction in LDL cholesterol in virtually every patient treated with inclisiran.

Two other phase 3 studies of inclisiran with similar design have been completed, and the results will come out before the end of 2019, according to a statement from the Medicines Company, which is developing the drug. The statement also said that the company plans to file their data with the FDA for marketing approval for inclisiran before the end of 2019. In the recent past, the FDA has approved drugs for the indication of lowering LDL cholesterol before evidence is available to prove that the agent has benefits for reducing clinical events.

Future studies of inclisiran will explore the efficacy of a single annual injection of the drug as an approach to primary prevention of cardiovascular disease, Dr. Ray said.

ORION-11 was sponsored by the Medicines Company. Dr. Ray is a consultant to it and to several other companies. Dr. Becker had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Sabatine has received research support from the Medicines Company and several other companies, and has received personal fees from Anthos Therapeutics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CVS Caremark, Daiichi Sankyo, DalCor Pharmaceuticals, Dyrnamix, and Ionis.

PARIS – A small interfering RNA drug, inclisiran, safely halved LDL cholesterol levels in more than 800 patients in a phase 3, multicenter study, in a big step toward this drug coming onto the market and offering an alternative way to harness the potent cholesterol-lowering power of PCSK9 inhibition.

In the reported study – which enrolled patients with established cardiovascular disease, familial hypercholesterolemia, type 2 diabetes, or a high Framingham Risk Score – participants received inclisiran as a semiannual subcutaneous injection. The safe efficacy this produced showed the viability of a new way to deliver lipid-lowering therapy that guarantees compliance and is convenient for patients.

The prospect of lowering cholesterol with about the same potency as the monoclonal antibodies that block PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9) activity but administered as a biannual injection “enables provider control over medication adherence, and may offer patients a meaningful new choice that is safe and convenient and has assured results,” Kausik K. Ray, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. The durable effect of the small interfering RNA (siRNA) agent “offers a huge advantage,” and “opens the field,” said Dr. Ray, a cardiologist and professor of public health at Imperial College, London.

He also highlighted the “excellent” safety profile seen in the 811 patients treated with inclisiran, compared with 804 patients in the study who received placebo. After four total injections of inclisiran spaced out over 450 days (about 15 months), the rate of treatment-emergent adverse events and serious events was virtually the same in the two treatment arms, and with no signal of inclisiran causing liver effects, renal or muscle injury, damage to blood components, or malignancy. The serial treatment with inclisiran that patients received – at baseline, 90, 270, and 450 days – produced no severe injection-site reactions, and transient mild or moderate injection-site reactions in just under 5% of patients.

Safety issues, such as more-severe injection-site reactions, thrombocytopenia, hepatotoxicity, and flu-like symptoms, plagued siRNA drugs during their earlier days of development, but more recently next-generation siRNA drugs with modified structures have produced much better safety performance, noted Richard C. Becker, MD, professor of medicine and director of the Heart, Lung, & Vascular Institute at the University of Cincinnati. The new-generation siRNAs such as inclisiran are “very well tolerated,” he said in an interview.

The Food and Drug Administration approved the first siRNA drug in August 2018, and in the year since then a few others have also come onto the U.S. market, Dr. Becker said.

Like other siRNA drugs, the activity of inclisiran comes from a short RNA segment that is antisense to a particular messenger RNA (mRNA) target. In the case of inclisiran, the target is the mRNA for the PCSK9 enzyme produced in hepatocytes, and that decreases the number of LDL cholesterol receptors on the cell’s surface. When the antisense RNA molecule encounters a PCSK9 mRNA, the two bind and the mRNA is then degraded by a normal cell process. This cuts the cell’s production of the PCSK9 protein, resulting in more LDL cholesterol receptors on the cell’s surface that pull more LDL cholesterol from the blood. The blocking of PCSK9 activity by inclisiran is roughly equivalent to the action of the PCSK9 monoclonal antibodies that have now been on the U.S. market for a few years. Also like other siRNA drugs, the RNA of inclisiran is packaged so that, once injected into a patient, the RNA molecules travel to the liver and enter hepatocytes, where they exert their activity.

“No one has concerns about inclisiran being able to lower LDL [cholesterol], and there have been no safety signals. The data we have seen so far look very reassuring, and in particular has been very safe for the liver,” commented Marc S. Sabatine, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, who has led several studies involving PCSK9-targeted drugs and is helping to run ORION-4, a 15,000-patient study of inclisiran designed to assess the drug’s effect on clinical events. Results from ORION-4 are not expected until about 2024.

“The PCSK9 inhibitors in general have been a huge advance for patients, and the more kinds of drugs we have to target PCSK9, the better,” he said in an interview.

The study reported by Dr. Ray, ORION-11, enrolled 1,617 patients with high atherosclerotic disease risk at 70 sites in six European countries and South Africa. The study’s primary efficacy endpoint was reduction from baseline in LDL cholesterol both at 510 days (about 17 months) after the first dose and also throughout the 15-month period that started 3 months after the first dose. The average reduction seen after 510 days was 54%, compared with baseline, and the time-averaged reduction during the 15-month window examined was 50%, Dr. Ray said. The results also showed a consistent reduction in LDL cholesterol in virtually every patient treated with inclisiran.

Two other phase 3 studies of inclisiran with similar design have been completed, and the results will come out before the end of 2019, according to a statement from the Medicines Company, which is developing the drug. The statement also said that the company plans to file their data with the FDA for marketing approval for inclisiran before the end of 2019. In the recent past, the FDA has approved drugs for the indication of lowering LDL cholesterol before evidence is available to prove that the agent has benefits for reducing clinical events.

Future studies of inclisiran will explore the efficacy of a single annual injection of the drug as an approach to primary prevention of cardiovascular disease, Dr. Ray said.

ORION-11 was sponsored by the Medicines Company. Dr. Ray is a consultant to it and to several other companies. Dr. Becker had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Sabatine has received research support from the Medicines Company and several other companies, and has received personal fees from Anthos Therapeutics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CVS Caremark, Daiichi Sankyo, DalCor Pharmaceuticals, Dyrnamix, and Ionis.

REPORTING FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2019

New hypertension cases halved with community-wide salt substitution

PARIS – In rural Peru, a comprehensive community-wide strategy to replace conventional table salt with a formulation that was 25% potassium chloride halved incident hypertension, also dropping blood pressure in participants with baseline hypertension.

The multifaceted intervention targeted six villages at the far north of Peru, replacing table salt with the lower-sodium substitute, J. Jaime Miranda, MD, PhD, said at a prevention-focused, late-breaking research session at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. The 75/25 mixture had a palatable proportion of potassium, and was easily produced by combining table salt with potassium chloride crystals.

Dr. Miranda, director of the CRONICAS Center of Excellence at the Cayetano Heredia Peruvian University, Lima, and colleagues enrolled virtually all adult residents of the six villages in the study; patients who reported heart disease or chronic kidney disease were excluded.

“We wanted to achieve and shape a pragmatic study – and a pragmatic study that incorporates day-to-day behavior. We eat every day, but we think very little of our salt habits,” said Dr. Miranda in a video interview.

In all, 2,376 of 2,605 potential participants enrolled in the study, which used a stepped-wedge, cluster-randomized, controlled trial design. To track the primary outcome measures of systolic and diastolic BP, measurements were obtained every 5 months for a total of seven rounds of measurement, said Dr. Miranda.

Dr. Miranda said that the investigators borrowed principles from social marketing to ensure community-wide replacement of table salt with the low-sodium substitute. This meant that they branded and packaged the low-sodium salt and gave it to participants at no cost – but with a catch. To receive the low-sodium salt, participants had to turn in their table salt.

The effort was supported by promotional events and a trained “sales force” who brought messaging to families, restaurants, and key voices in the community. The attractively packaged replacement salt was distributed with a similarly branded shaker. “We wanted to guarantee the full replacement of salt in the entire village,” explained Dr. Miranda.

At the end of the study, individuals with hypertension saw a decrease in systolic BP of 1.92 mm Hg (95% confidence interval, –3.29 to –0.54).

New hypertension diagnoses, a secondary outcome measure, fell by 55% in participating villages; the hazard ratio for hypertension incidence was 0.45 (95% CI, 0.31-0.66) in a fully adjusted statistical model that accounted for clustering at the village level, as well as age, sex, education, wealth index, and body mass index, said Dr. Miranda.

Older village residents with hypertension saw greater BP reduction; for those aged at least 60 years, the mean reduction was 2.17 mm Hg (95% CI, –3.67 to –0.68).

The positive findings were met with broad applause during his presentation, a response that made his 15-hour trip from Lima to Paris worthwhile, said Dr. Miranda.

Adherence was assessed by obtaining 24-hour urine samples from a random sample of 100 participants before and after the study. “This was my biggest fear – that as soon as we left the door, people would go and throw it away,” said Dr. Miranda. Among these participants, excreted potassium rose, indicating adherence, but sodium stayed basically the same. Possible explanations included that individuals were adding table salt to their diets, or that other prepared foods or condiments contained high amounts of sodium.

The study shows the feasibility of a community-wide intervention that achieved the dual aims of population-wide reductions in BP and reduction in incident BP, and of achieving clinically meaningful benefits for the high-risk population, said Dr. Miranda. He remarked that the population was young overall, with a mean age of 43 years and a low mean baseline systolic BP of 113, making the modest population-wide reduction more notable.

“We wanted to shift the entire distribution of blood pressure in the village. And with that, we see gains not only in public health, but also effective improvements in blood pressure in those at high risk, particularly those who tend to have high blood pressure,” said Dr. Miranda.

Discussant Bruce Neal, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Sydney and senior director of the George Institute for Global Health in Newtown, Australia, congratulated Dr. Miranda and colleagues on accomplishing “a truly enormous project.” He began by noting that, though the reductions were modest, “the low starting blood pressures were almost certainly responsible for the magnitude of effect seen in this study.” He added that “this is nonetheless a worthwhile blood pressure reduction, particularly if it was sustained throughout life.”