User login

Prepare for deluge of JAK inhibitors for RA

MAUI, HAWAII – As it grows increasingly likely that oral Janus kinase inhibitors will constitute a major development in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, with a bevy of these agents becoming available for that indication, rheumatologists are asking questions about the coming revolution. Like, when should these agents be used? What are the major safety and efficacy differences, if any, within the class? How clinically relevant is JAK selectivity? And which JAK inhibitor is the best choice?

on these and other related questions at the 2019 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

These issues take on growing relevance for clinicians and their RA patients because two oral small molecule JAK inhibitors – tofacitinib (Xeljanz) and baricitinib (Olumiant) – are already approved for RA, and three more – upadacitinib, filgotinib, and peficitinib – are on the horizon. Indeed, AbbVie has already filed for marketing approval of once-daily upadacitinib for RA on the basis of an impressive development program featuring six phase 3 trials, with a priority review decision from the Food and Drug Administration anticipated this fall. Filgotinib is the focus of three phase 3 studies, one of which is viewed as a home run, with the other two yet to report results. Peficitinib is backed by two positive phase 3 trials, although its manufacturer will at least initially seek marketing approval only in Japan and South Korea. And numerous other JAK inhibitors are in development for a variety of indications.

When should a JAK inhibitor be used?

That’s easy, according to Roy M. Fleischmann, MD: If the cost proves comparable, it makes sense to turn to a JAK inhibitor ahead of a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor or other biologic.

He noted that in the double-blind, phase 3 SELECT-COMPARE head-to-head comparison of upadacitinib at 15 mg/day, adalimumab (Humira) at 40 mg every other week, versus placebo, all on top of background methotrexate, upadacitinib proved superior to the market-leading tumor necrosis factor inhibitor in terms of both the American College of Rheumatology–defined 20% level of response (ACR 20) and 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on C-reactive protein (DAS28-CRP).

“The results were very dramatic,” noted Dr. Fleischmann, who presented the SELECT-COMPARE findings at the 2018 annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Moreover, other major trials have shown that baricitinib at 4 mg/day was superior in efficacy to adalimumab, and tofacitinib and peficitinib were “at least equal” to anti-TNF therapy, he added.

“These numbers are clinically meaningful – not so much for the difference in ACR 20, but in the depth of response: the ACR 50 and 70, the CDAI. I think these drugs are better than adalimumab,” declared Dr. Fleischmann, codirector of the division of rheumatology at Texas Health Presbyterian Medical Center, Dallas.

Mark Genovese, MD, concurred.

“I think that for most patients who don’t have a lot of other comorbidities, they would certainly prefer to take a pill over a shot. And if you have a drug that’s more effective than the standard of care and it comes at a reasonable price point – and ‘reasonable’ is in the eye of the beholder – but if I can get access to it on the formulary, I’d have no qualms about putting them on a JAK inhibitor before I’d move to a TNF inhibitor,” said Dr. Genovese, professor of medicine and director of the rheumatology clinic at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Upadacitinib elicited a better response at 30 mg than at 15 mg once daily in the phase 3 program; however, both speakers indicated they’d be happy with access to the 15-mg dose, should the FDA go that route, since it has a better safety profile.

Dr. Genovese was principal investigator in the previously reported multicenter FINCH2 trial of filgotinib at 100 or 200 mg/day in RA patients with a prior inadequate response to one or more biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

“Impressive results in a refractory population,” he said. “I don’t see a big difference in safety between 100 and 200 mg, so I’d opt for the 200 because it worked really well in patients who had refractory disease.”

Other advantages of JAK inhibitors

Speed of onset is another advantage in addition to oral administration and efficacy greater than or equivalent to anti-TNF therapy, according to Dr. Genovese.

“As a class, JAK inhibitors have a faster onset than methotrexate in terms of improvement in disease activity and pain. So in a few weeks you can have a sense of whether folks are going to be responders,” the rheumatologist said.

Does JAK isoform selectivity really make a difference in terms of efficacy and safety?

It’s doubtful, the rheumatologists agreed. All of these oral small molecules target JAK1, and that’s what’s key.

Tofacitinib is relatively selective for JAK1 and JAK3, baricitinib for JAK1 and JAK2, upadacitinib and fibotinib for JAK1, and peficitinib is a pan-JAK inhibitor.

What are the safety concerns with this class of medications?

The risk of herpes zoster is higher than with TNF inhibitors, reinforcing the importance of varicella vaccination in JAK inhibitor candidates. Anemia occurs in a small percentage of patients. As for the risk of venous thromboembolism as a potential side effect of JAK inhibitors, a topic of great concern to the FDA, Dr. Fleischmann dismissed it as vastly overblown.

“I think VTEs are an RA effect. You see it with all the drugs, including methotrexate,” he said.

Idiosyncratic self-limited increases in creatine kinase have been seen in 2%-4% of patients on JAK inhibitors in pretty much all of the clinical trials. “I’m not aware of any cases of myositis, though,” Dr. Fleischmann noted.

As for the teratogenicity potential of JAK inhibitors, Dr. Genovese said that, as is true for most medications, it hasn’t been well studied.

“We don’t know. But I would not choose to use a JAK inhibitor in a woman who is going to conceive, has conceived, or is breastfeeding. I just don’t think that would be a good decision,” according to the rheumatologist.

Which JAK inhibitor is the best choice for treatment of RA?

It’s impossible to say because of the hazards in trying to draw meaningful conclusions from cross-study comparisons, the experts agreed.

“It’s a challenge. I think at the end of the day there will probably be one agent that looks like it might be best in class predicated on having the most number of indications, and that will probably become a preferred agent. The question is, does that happen before tofacitinib goes generic? And I don’t know the answer to that,” Dr. Genovese said.

Notably, upadacitinib is the subject of a plethora of ongoing phase 3 trials in atopic dermatitis, psoriatic arthritis, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis. It is also in earlier-phase investigation for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis.

Do we really need all these JAK inhibitors?

“How many TNF inhibitors do you need?” Dr. Genovese retorted. “I think the reality is there’s probably a finite number and additional members add to the class, but there probably will always be one or two that are going to be best in class.”

Both rheumatologists indicated they serve as consultants to more than a dozen pharmaceutical companies and receive research grants from numerous firms.

MAUI, HAWAII – As it grows increasingly likely that oral Janus kinase inhibitors will constitute a major development in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, with a bevy of these agents becoming available for that indication, rheumatologists are asking questions about the coming revolution. Like, when should these agents be used? What are the major safety and efficacy differences, if any, within the class? How clinically relevant is JAK selectivity? And which JAK inhibitor is the best choice?

on these and other related questions at the 2019 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

These issues take on growing relevance for clinicians and their RA patients because two oral small molecule JAK inhibitors – tofacitinib (Xeljanz) and baricitinib (Olumiant) – are already approved for RA, and three more – upadacitinib, filgotinib, and peficitinib – are on the horizon. Indeed, AbbVie has already filed for marketing approval of once-daily upadacitinib for RA on the basis of an impressive development program featuring six phase 3 trials, with a priority review decision from the Food and Drug Administration anticipated this fall. Filgotinib is the focus of three phase 3 studies, one of which is viewed as a home run, with the other two yet to report results. Peficitinib is backed by two positive phase 3 trials, although its manufacturer will at least initially seek marketing approval only in Japan and South Korea. And numerous other JAK inhibitors are in development for a variety of indications.

When should a JAK inhibitor be used?

That’s easy, according to Roy M. Fleischmann, MD: If the cost proves comparable, it makes sense to turn to a JAK inhibitor ahead of a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor or other biologic.

He noted that in the double-blind, phase 3 SELECT-COMPARE head-to-head comparison of upadacitinib at 15 mg/day, adalimumab (Humira) at 40 mg every other week, versus placebo, all on top of background methotrexate, upadacitinib proved superior to the market-leading tumor necrosis factor inhibitor in terms of both the American College of Rheumatology–defined 20% level of response (ACR 20) and 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on C-reactive protein (DAS28-CRP).

“The results were very dramatic,” noted Dr. Fleischmann, who presented the SELECT-COMPARE findings at the 2018 annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Moreover, other major trials have shown that baricitinib at 4 mg/day was superior in efficacy to adalimumab, and tofacitinib and peficitinib were “at least equal” to anti-TNF therapy, he added.

“These numbers are clinically meaningful – not so much for the difference in ACR 20, but in the depth of response: the ACR 50 and 70, the CDAI. I think these drugs are better than adalimumab,” declared Dr. Fleischmann, codirector of the division of rheumatology at Texas Health Presbyterian Medical Center, Dallas.

Mark Genovese, MD, concurred.

“I think that for most patients who don’t have a lot of other comorbidities, they would certainly prefer to take a pill over a shot. And if you have a drug that’s more effective than the standard of care and it comes at a reasonable price point – and ‘reasonable’ is in the eye of the beholder – but if I can get access to it on the formulary, I’d have no qualms about putting them on a JAK inhibitor before I’d move to a TNF inhibitor,” said Dr. Genovese, professor of medicine and director of the rheumatology clinic at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Upadacitinib elicited a better response at 30 mg than at 15 mg once daily in the phase 3 program; however, both speakers indicated they’d be happy with access to the 15-mg dose, should the FDA go that route, since it has a better safety profile.

Dr. Genovese was principal investigator in the previously reported multicenter FINCH2 trial of filgotinib at 100 or 200 mg/day in RA patients with a prior inadequate response to one or more biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

“Impressive results in a refractory population,” he said. “I don’t see a big difference in safety between 100 and 200 mg, so I’d opt for the 200 because it worked really well in patients who had refractory disease.”

Other advantages of JAK inhibitors

Speed of onset is another advantage in addition to oral administration and efficacy greater than or equivalent to anti-TNF therapy, according to Dr. Genovese.

“As a class, JAK inhibitors have a faster onset than methotrexate in terms of improvement in disease activity and pain. So in a few weeks you can have a sense of whether folks are going to be responders,” the rheumatologist said.

Does JAK isoform selectivity really make a difference in terms of efficacy and safety?

It’s doubtful, the rheumatologists agreed. All of these oral small molecules target JAK1, and that’s what’s key.

Tofacitinib is relatively selective for JAK1 and JAK3, baricitinib for JAK1 and JAK2, upadacitinib and fibotinib for JAK1, and peficitinib is a pan-JAK inhibitor.

What are the safety concerns with this class of medications?

The risk of herpes zoster is higher than with TNF inhibitors, reinforcing the importance of varicella vaccination in JAK inhibitor candidates. Anemia occurs in a small percentage of patients. As for the risk of venous thromboembolism as a potential side effect of JAK inhibitors, a topic of great concern to the FDA, Dr. Fleischmann dismissed it as vastly overblown.

“I think VTEs are an RA effect. You see it with all the drugs, including methotrexate,” he said.

Idiosyncratic self-limited increases in creatine kinase have been seen in 2%-4% of patients on JAK inhibitors in pretty much all of the clinical trials. “I’m not aware of any cases of myositis, though,” Dr. Fleischmann noted.

As for the teratogenicity potential of JAK inhibitors, Dr. Genovese said that, as is true for most medications, it hasn’t been well studied.

“We don’t know. But I would not choose to use a JAK inhibitor in a woman who is going to conceive, has conceived, or is breastfeeding. I just don’t think that would be a good decision,” according to the rheumatologist.

Which JAK inhibitor is the best choice for treatment of RA?

It’s impossible to say because of the hazards in trying to draw meaningful conclusions from cross-study comparisons, the experts agreed.

“It’s a challenge. I think at the end of the day there will probably be one agent that looks like it might be best in class predicated on having the most number of indications, and that will probably become a preferred agent. The question is, does that happen before tofacitinib goes generic? And I don’t know the answer to that,” Dr. Genovese said.

Notably, upadacitinib is the subject of a plethora of ongoing phase 3 trials in atopic dermatitis, psoriatic arthritis, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis. It is also in earlier-phase investigation for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis.

Do we really need all these JAK inhibitors?

“How many TNF inhibitors do you need?” Dr. Genovese retorted. “I think the reality is there’s probably a finite number and additional members add to the class, but there probably will always be one or two that are going to be best in class.”

Both rheumatologists indicated they serve as consultants to more than a dozen pharmaceutical companies and receive research grants from numerous firms.

MAUI, HAWAII – As it grows increasingly likely that oral Janus kinase inhibitors will constitute a major development in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, with a bevy of these agents becoming available for that indication, rheumatologists are asking questions about the coming revolution. Like, when should these agents be used? What are the major safety and efficacy differences, if any, within the class? How clinically relevant is JAK selectivity? And which JAK inhibitor is the best choice?

on these and other related questions at the 2019 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

These issues take on growing relevance for clinicians and their RA patients because two oral small molecule JAK inhibitors – tofacitinib (Xeljanz) and baricitinib (Olumiant) – are already approved for RA, and three more – upadacitinib, filgotinib, and peficitinib – are on the horizon. Indeed, AbbVie has already filed for marketing approval of once-daily upadacitinib for RA on the basis of an impressive development program featuring six phase 3 trials, with a priority review decision from the Food and Drug Administration anticipated this fall. Filgotinib is the focus of three phase 3 studies, one of which is viewed as a home run, with the other two yet to report results. Peficitinib is backed by two positive phase 3 trials, although its manufacturer will at least initially seek marketing approval only in Japan and South Korea. And numerous other JAK inhibitors are in development for a variety of indications.

When should a JAK inhibitor be used?

That’s easy, according to Roy M. Fleischmann, MD: If the cost proves comparable, it makes sense to turn to a JAK inhibitor ahead of a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor or other biologic.

He noted that in the double-blind, phase 3 SELECT-COMPARE head-to-head comparison of upadacitinib at 15 mg/day, adalimumab (Humira) at 40 mg every other week, versus placebo, all on top of background methotrexate, upadacitinib proved superior to the market-leading tumor necrosis factor inhibitor in terms of both the American College of Rheumatology–defined 20% level of response (ACR 20) and 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on C-reactive protein (DAS28-CRP).

“The results were very dramatic,” noted Dr. Fleischmann, who presented the SELECT-COMPARE findings at the 2018 annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Moreover, other major trials have shown that baricitinib at 4 mg/day was superior in efficacy to adalimumab, and tofacitinib and peficitinib were “at least equal” to anti-TNF therapy, he added.

“These numbers are clinically meaningful – not so much for the difference in ACR 20, but in the depth of response: the ACR 50 and 70, the CDAI. I think these drugs are better than adalimumab,” declared Dr. Fleischmann, codirector of the division of rheumatology at Texas Health Presbyterian Medical Center, Dallas.

Mark Genovese, MD, concurred.

“I think that for most patients who don’t have a lot of other comorbidities, they would certainly prefer to take a pill over a shot. And if you have a drug that’s more effective than the standard of care and it comes at a reasonable price point – and ‘reasonable’ is in the eye of the beholder – but if I can get access to it on the formulary, I’d have no qualms about putting them on a JAK inhibitor before I’d move to a TNF inhibitor,” said Dr. Genovese, professor of medicine and director of the rheumatology clinic at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Upadacitinib elicited a better response at 30 mg than at 15 mg once daily in the phase 3 program; however, both speakers indicated they’d be happy with access to the 15-mg dose, should the FDA go that route, since it has a better safety profile.

Dr. Genovese was principal investigator in the previously reported multicenter FINCH2 trial of filgotinib at 100 or 200 mg/day in RA patients with a prior inadequate response to one or more biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

“Impressive results in a refractory population,” he said. “I don’t see a big difference in safety between 100 and 200 mg, so I’d opt for the 200 because it worked really well in patients who had refractory disease.”

Other advantages of JAK inhibitors

Speed of onset is another advantage in addition to oral administration and efficacy greater than or equivalent to anti-TNF therapy, according to Dr. Genovese.

“As a class, JAK inhibitors have a faster onset than methotrexate in terms of improvement in disease activity and pain. So in a few weeks you can have a sense of whether folks are going to be responders,” the rheumatologist said.

Does JAK isoform selectivity really make a difference in terms of efficacy and safety?

It’s doubtful, the rheumatologists agreed. All of these oral small molecules target JAK1, and that’s what’s key.

Tofacitinib is relatively selective for JAK1 and JAK3, baricitinib for JAK1 and JAK2, upadacitinib and fibotinib for JAK1, and peficitinib is a pan-JAK inhibitor.

What are the safety concerns with this class of medications?

The risk of herpes zoster is higher than with TNF inhibitors, reinforcing the importance of varicella vaccination in JAK inhibitor candidates. Anemia occurs in a small percentage of patients. As for the risk of venous thromboembolism as a potential side effect of JAK inhibitors, a topic of great concern to the FDA, Dr. Fleischmann dismissed it as vastly overblown.

“I think VTEs are an RA effect. You see it with all the drugs, including methotrexate,” he said.

Idiosyncratic self-limited increases in creatine kinase have been seen in 2%-4% of patients on JAK inhibitors in pretty much all of the clinical trials. “I’m not aware of any cases of myositis, though,” Dr. Fleischmann noted.

As for the teratogenicity potential of JAK inhibitors, Dr. Genovese said that, as is true for most medications, it hasn’t been well studied.

“We don’t know. But I would not choose to use a JAK inhibitor in a woman who is going to conceive, has conceived, or is breastfeeding. I just don’t think that would be a good decision,” according to the rheumatologist.

Which JAK inhibitor is the best choice for treatment of RA?

It’s impossible to say because of the hazards in trying to draw meaningful conclusions from cross-study comparisons, the experts agreed.

“It’s a challenge. I think at the end of the day there will probably be one agent that looks like it might be best in class predicated on having the most number of indications, and that will probably become a preferred agent. The question is, does that happen before tofacitinib goes generic? And I don’t know the answer to that,” Dr. Genovese said.

Notably, upadacitinib is the subject of a plethora of ongoing phase 3 trials in atopic dermatitis, psoriatic arthritis, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis. It is also in earlier-phase investigation for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis.

Do we really need all these JAK inhibitors?

“How many TNF inhibitors do you need?” Dr. Genovese retorted. “I think the reality is there’s probably a finite number and additional members add to the class, but there probably will always be one or two that are going to be best in class.”

Both rheumatologists indicated they serve as consultants to more than a dozen pharmaceutical companies and receive research grants from numerous firms.

REPORTING FROM RWCS 2019

Interosseous tendon inflammation is common prior to RA

MAUI, HAWAII – Inflammation of the hand interosseous tendons found on MRI is a novel target in efforts to preempt the development and progression of rheumatoid arthritis, Paul Emery, MD, said at the 2019 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

He and his coinvestigators have previously shown there is a high prevalence of interosseous tendon inflammation in the hands of patients with established RA, but now they’ve demonstrated that this phenomenon also occurs in anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP)–positive individuals at increased risk for RA, even before onset of clinical synovitis.

This finding is consistent with the notion that, even though RA is classically considered a disease of the synovial joints, the joint involvement is a relatively late phenomenon in the disease development process and extracapsular structures may be important early targets of RA-related inflammation. Indeed, the MRI finding of tenosynovitis of the wrist and finger flexor tendons is known to be the strongest predictor of progression to arthritis in patients with recent-onset arthralgia or other musculoskeletal symptoms but no clinical synovitis, according to Dr. Emery, professor of rheumatology and director of the University of Leeds (England) Musculoskeletal Biomedical Research Center.

Because the interosseous muscles of the hands play a critical role in hand function – pianists and other musicians not infrequently present to rheumatologists with overuse injuries of the muscles and their tendons – Dr. Emery and his coworkers decided to take a comprehensive look at interosseous tendon inflammation across the full spectrum of RA and pre-RA. They conducted a retrospective study of clinical and hand MRI data on 93 CCP-positive patients who presented with new-onset musculoskeletal symptoms but no clinical synovitis; 47 patients with early RA, all of whom were disease-modifying antirheumatic drug–naive; 28 patients with late RA as defined by at least 1 year of symptoms, anti-CCP and/or rheumatoid factor positivity, a Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28) of 3.2 or more, plus a history of exposure to one or more DMARDs at the time of their hand imaging; and 20 healthy controls.

The key finding is that the proportion of subjects with MRI evidence of interosseous tendon inflammation rose along the advancing RA continuum. It was present in 19% of the CCP-positive patients without clinical synovitis; 49% of the DMARD-naive early RA group; 57% of the late RA group; and in none of the healthy controls. Moreover, the number of inflamed interosseous tendons per patient also increased with RA progression.

A total of 12% of 507 nontender metacarpophalangeal joints showed MRI evidence of interosseous tendon inflammation, as did 28% of 141 tender ones (Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Mar 23. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214331).

As part of the study, Dr. Emery and coinvestigators performed cadaveric dissections that demonstrated that the interosseous tendons don’t possess a tendon sheath and don’t directly communicate with the joint capsule.

A prospective study is warranted in order to confirm the observed association between interosseous tendon inflammation and clinical and subclinical synovitis and to establish the predictive value of hand MRI as a harbinger of RA, he noted.

Dr. Emery reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

MAUI, HAWAII – Inflammation of the hand interosseous tendons found on MRI is a novel target in efforts to preempt the development and progression of rheumatoid arthritis, Paul Emery, MD, said at the 2019 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

He and his coinvestigators have previously shown there is a high prevalence of interosseous tendon inflammation in the hands of patients with established RA, but now they’ve demonstrated that this phenomenon also occurs in anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP)–positive individuals at increased risk for RA, even before onset of clinical synovitis.

This finding is consistent with the notion that, even though RA is classically considered a disease of the synovial joints, the joint involvement is a relatively late phenomenon in the disease development process and extracapsular structures may be important early targets of RA-related inflammation. Indeed, the MRI finding of tenosynovitis of the wrist and finger flexor tendons is known to be the strongest predictor of progression to arthritis in patients with recent-onset arthralgia or other musculoskeletal symptoms but no clinical synovitis, according to Dr. Emery, professor of rheumatology and director of the University of Leeds (England) Musculoskeletal Biomedical Research Center.

Because the interosseous muscles of the hands play a critical role in hand function – pianists and other musicians not infrequently present to rheumatologists with overuse injuries of the muscles and their tendons – Dr. Emery and his coworkers decided to take a comprehensive look at interosseous tendon inflammation across the full spectrum of RA and pre-RA. They conducted a retrospective study of clinical and hand MRI data on 93 CCP-positive patients who presented with new-onset musculoskeletal symptoms but no clinical synovitis; 47 patients with early RA, all of whom were disease-modifying antirheumatic drug–naive; 28 patients with late RA as defined by at least 1 year of symptoms, anti-CCP and/or rheumatoid factor positivity, a Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28) of 3.2 or more, plus a history of exposure to one or more DMARDs at the time of their hand imaging; and 20 healthy controls.

The key finding is that the proportion of subjects with MRI evidence of interosseous tendon inflammation rose along the advancing RA continuum. It was present in 19% of the CCP-positive patients without clinical synovitis; 49% of the DMARD-naive early RA group; 57% of the late RA group; and in none of the healthy controls. Moreover, the number of inflamed interosseous tendons per patient also increased with RA progression.

A total of 12% of 507 nontender metacarpophalangeal joints showed MRI evidence of interosseous tendon inflammation, as did 28% of 141 tender ones (Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Mar 23. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214331).

As part of the study, Dr. Emery and coinvestigators performed cadaveric dissections that demonstrated that the interosseous tendons don’t possess a tendon sheath and don’t directly communicate with the joint capsule.

A prospective study is warranted in order to confirm the observed association between interosseous tendon inflammation and clinical and subclinical synovitis and to establish the predictive value of hand MRI as a harbinger of RA, he noted.

Dr. Emery reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

MAUI, HAWAII – Inflammation of the hand interosseous tendons found on MRI is a novel target in efforts to preempt the development and progression of rheumatoid arthritis, Paul Emery, MD, said at the 2019 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

He and his coinvestigators have previously shown there is a high prevalence of interosseous tendon inflammation in the hands of patients with established RA, but now they’ve demonstrated that this phenomenon also occurs in anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP)–positive individuals at increased risk for RA, even before onset of clinical synovitis.

This finding is consistent with the notion that, even though RA is classically considered a disease of the synovial joints, the joint involvement is a relatively late phenomenon in the disease development process and extracapsular structures may be important early targets of RA-related inflammation. Indeed, the MRI finding of tenosynovitis of the wrist and finger flexor tendons is known to be the strongest predictor of progression to arthritis in patients with recent-onset arthralgia or other musculoskeletal symptoms but no clinical synovitis, according to Dr. Emery, professor of rheumatology and director of the University of Leeds (England) Musculoskeletal Biomedical Research Center.

Because the interosseous muscles of the hands play a critical role in hand function – pianists and other musicians not infrequently present to rheumatologists with overuse injuries of the muscles and their tendons – Dr. Emery and his coworkers decided to take a comprehensive look at interosseous tendon inflammation across the full spectrum of RA and pre-RA. They conducted a retrospective study of clinical and hand MRI data on 93 CCP-positive patients who presented with new-onset musculoskeletal symptoms but no clinical synovitis; 47 patients with early RA, all of whom were disease-modifying antirheumatic drug–naive; 28 patients with late RA as defined by at least 1 year of symptoms, anti-CCP and/or rheumatoid factor positivity, a Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28) of 3.2 or more, plus a history of exposure to one or more DMARDs at the time of their hand imaging; and 20 healthy controls.

The key finding is that the proportion of subjects with MRI evidence of interosseous tendon inflammation rose along the advancing RA continuum. It was present in 19% of the CCP-positive patients without clinical synovitis; 49% of the DMARD-naive early RA group; 57% of the late RA group; and in none of the healthy controls. Moreover, the number of inflamed interosseous tendons per patient also increased with RA progression.

A total of 12% of 507 nontender metacarpophalangeal joints showed MRI evidence of interosseous tendon inflammation, as did 28% of 141 tender ones (Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Mar 23. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214331).

As part of the study, Dr. Emery and coinvestigators performed cadaveric dissections that demonstrated that the interosseous tendons don’t possess a tendon sheath and don’t directly communicate with the joint capsule.

A prospective study is warranted in order to confirm the observed association between interosseous tendon inflammation and clinical and subclinical synovitis and to establish the predictive value of hand MRI as a harbinger of RA, he noted.

Dr. Emery reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

REPORTING FROM RWCS 2019

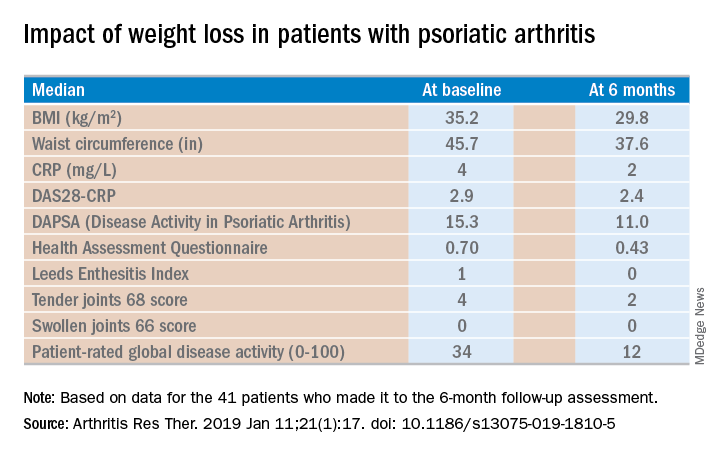

Weight loss improves psoriatic arthritis

MAUI, HAWAII – Serious weight loss brings big improvement in psoriatic arthritis in obese patients, at least short term, according to a Swedish, single-arm, prospective, proof-of-concept study.

A dose-response effect was evident: the greater the lost poundage, the bigger the improvement across multiple dimensions of psoriatic arthritis.

The short-term efficacy was eye-catching, especially in view of the well-recognized increased prevalence of obesity in psoriatic arthritis patients. But the jury is still out as to the long-term impact of this nonpharmacologic therapy, Eric M. Ruderman, MD, said at the 2019 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

He has spoken with the Swedish investigators and was happy to learn they’re continuing to follow study participants long term.

“That’s going to be the key, right? Because if you do this for 12 weeks, like every other fad crash diet, and then you let the weight go right back on again, you haven’t really accomplished anything. I think the key will be what happens at a year,” according to Dr. Ruderman, professor of medicine and associate chief for clinical affairs in the division of rheumatology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The study included 46 obese psoriatic arthritis patients who signed on for a structured, medically supervised very-low-energy diet lasting 12-16 weeks, depending upon their baseline obesity level. The commercially available liquid diet (Cambridge Weight Plan Limited) is a type of therapy widely prescribed by Swedish physicians, clocking in at a mere 640 kcal/day.

“I don’t know about you, but I ate that at breakfast this morning,” quipped symposium director Arthur Kavanaugh, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Following completion of the strict very-low-energy diet, patients were gradually reintroduced to a less-draconian, solid-food, energy-restricted diet, to be followed through the 12-month mark. The full 12-month protocol was supervised by staff in the obesity unit at Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Gothenburg, Sweden. The 12-month results will be presented at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology in Madrid.

Of the 46 starters, 41 made it to the 6-month follow-up assessment. At that point they’d lost a median of 18.2 kg, or 18.6% of their baseline body weight. Their body mass index had dropped from an average of 35.2 to 29.8 kg/m2. And their psoriatic arthritis had improved significantly. For example, their median Disease Activity Score using 28 joint counts based upon C-reactive protein (DAS28-CRP) decreased from 2.9 at baseline to 2.4 at 6 months, with ACR 20, -50, and -70 responses of 51.2%, 34.1%, and 7.3% while disease-directed medications were held constant (Arthritis Res Ther. 2019 Jan 11;21[1]:17. doi: 10.1186/s13075-019-1810-5).

The investigators reported the very-low-energy diet phase was generally well tolerated. A total of 34 of the 41 patients deemed it “easier or much easier” than expected, prompting Dr. Ruderman to comment: “Because they thought it was going to be awful.”

Dr. Ruderman and Dr. Kavanaugh reported serving as consultants to numerous pharmaceutical companies.

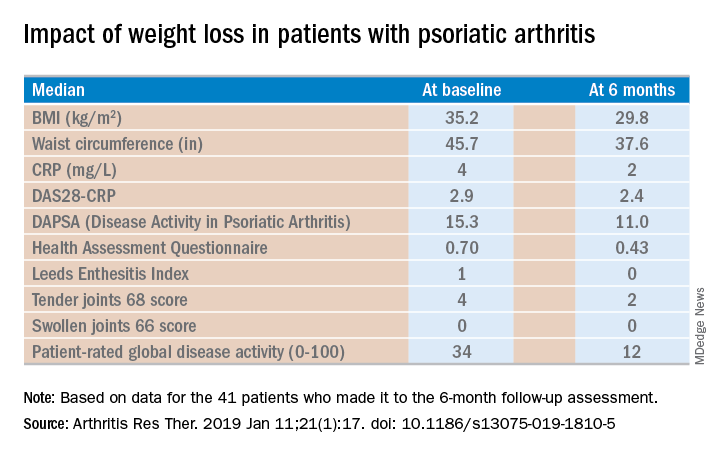

MAUI, HAWAII – Serious weight loss brings big improvement in psoriatic arthritis in obese patients, at least short term, according to a Swedish, single-arm, prospective, proof-of-concept study.

A dose-response effect was evident: the greater the lost poundage, the bigger the improvement across multiple dimensions of psoriatic arthritis.

The short-term efficacy was eye-catching, especially in view of the well-recognized increased prevalence of obesity in psoriatic arthritis patients. But the jury is still out as to the long-term impact of this nonpharmacologic therapy, Eric M. Ruderman, MD, said at the 2019 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

He has spoken with the Swedish investigators and was happy to learn they’re continuing to follow study participants long term.

“That’s going to be the key, right? Because if you do this for 12 weeks, like every other fad crash diet, and then you let the weight go right back on again, you haven’t really accomplished anything. I think the key will be what happens at a year,” according to Dr. Ruderman, professor of medicine and associate chief for clinical affairs in the division of rheumatology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The study included 46 obese psoriatic arthritis patients who signed on for a structured, medically supervised very-low-energy diet lasting 12-16 weeks, depending upon their baseline obesity level. The commercially available liquid diet (Cambridge Weight Plan Limited) is a type of therapy widely prescribed by Swedish physicians, clocking in at a mere 640 kcal/day.

“I don’t know about you, but I ate that at breakfast this morning,” quipped symposium director Arthur Kavanaugh, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Following completion of the strict very-low-energy diet, patients were gradually reintroduced to a less-draconian, solid-food, energy-restricted diet, to be followed through the 12-month mark. The full 12-month protocol was supervised by staff in the obesity unit at Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Gothenburg, Sweden. The 12-month results will be presented at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology in Madrid.

Of the 46 starters, 41 made it to the 6-month follow-up assessment. At that point they’d lost a median of 18.2 kg, or 18.6% of their baseline body weight. Their body mass index had dropped from an average of 35.2 to 29.8 kg/m2. And their psoriatic arthritis had improved significantly. For example, their median Disease Activity Score using 28 joint counts based upon C-reactive protein (DAS28-CRP) decreased from 2.9 at baseline to 2.4 at 6 months, with ACR 20, -50, and -70 responses of 51.2%, 34.1%, and 7.3% while disease-directed medications were held constant (Arthritis Res Ther. 2019 Jan 11;21[1]:17. doi: 10.1186/s13075-019-1810-5).

The investigators reported the very-low-energy diet phase was generally well tolerated. A total of 34 of the 41 patients deemed it “easier or much easier” than expected, prompting Dr. Ruderman to comment: “Because they thought it was going to be awful.”

Dr. Ruderman and Dr. Kavanaugh reported serving as consultants to numerous pharmaceutical companies.

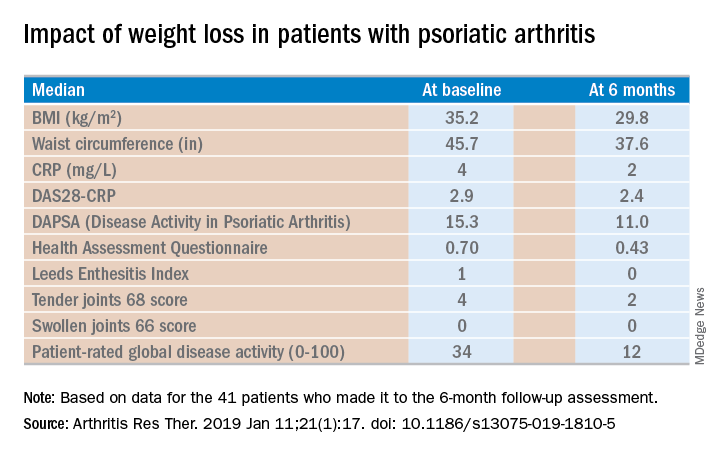

MAUI, HAWAII – Serious weight loss brings big improvement in psoriatic arthritis in obese patients, at least short term, according to a Swedish, single-arm, prospective, proof-of-concept study.

A dose-response effect was evident: the greater the lost poundage, the bigger the improvement across multiple dimensions of psoriatic arthritis.

The short-term efficacy was eye-catching, especially in view of the well-recognized increased prevalence of obesity in psoriatic arthritis patients. But the jury is still out as to the long-term impact of this nonpharmacologic therapy, Eric M. Ruderman, MD, said at the 2019 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

He has spoken with the Swedish investigators and was happy to learn they’re continuing to follow study participants long term.

“That’s going to be the key, right? Because if you do this for 12 weeks, like every other fad crash diet, and then you let the weight go right back on again, you haven’t really accomplished anything. I think the key will be what happens at a year,” according to Dr. Ruderman, professor of medicine and associate chief for clinical affairs in the division of rheumatology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The study included 46 obese psoriatic arthritis patients who signed on for a structured, medically supervised very-low-energy diet lasting 12-16 weeks, depending upon their baseline obesity level. The commercially available liquid diet (Cambridge Weight Plan Limited) is a type of therapy widely prescribed by Swedish physicians, clocking in at a mere 640 kcal/day.

“I don’t know about you, but I ate that at breakfast this morning,” quipped symposium director Arthur Kavanaugh, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Following completion of the strict very-low-energy diet, patients were gradually reintroduced to a less-draconian, solid-food, energy-restricted diet, to be followed through the 12-month mark. The full 12-month protocol was supervised by staff in the obesity unit at Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Gothenburg, Sweden. The 12-month results will be presented at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology in Madrid.

Of the 46 starters, 41 made it to the 6-month follow-up assessment. At that point they’d lost a median of 18.2 kg, or 18.6% of their baseline body weight. Their body mass index had dropped from an average of 35.2 to 29.8 kg/m2. And their psoriatic arthritis had improved significantly. For example, their median Disease Activity Score using 28 joint counts based upon C-reactive protein (DAS28-CRP) decreased from 2.9 at baseline to 2.4 at 6 months, with ACR 20, -50, and -70 responses of 51.2%, 34.1%, and 7.3% while disease-directed medications were held constant (Arthritis Res Ther. 2019 Jan 11;21[1]:17. doi: 10.1186/s13075-019-1810-5).

The investigators reported the very-low-energy diet phase was generally well tolerated. A total of 34 of the 41 patients deemed it “easier or much easier” than expected, prompting Dr. Ruderman to comment: “Because they thought it was going to be awful.”

Dr. Ruderman and Dr. Kavanaugh reported serving as consultants to numerous pharmaceutical companies.

REPORTING FROM RWCS 2019

Methotrexate pneumonitis called ‘super rare’

MAUI, HAWAII – The incidence of methotrexate pneumonitis has been reported as ranging from 3.5% to 7.6% among patients taking the disease-modifying antirheumatic drug. It’s an estimate that Aryeh Fischer, MD, counters with a one-word response: “Nonsense!”

“There’s just no way that methotrexate is causing that much lung disease,” he declared at the 2019 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

Dr. Fischer, a rheumatologist with joint appointments to the divisions of rheumatology and pulmonary sciences and critical care medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, noted that his opinion is considered controversial in the pulmonology world.

“I’m not allowed to talk about methotrexate at lung conferences. They stop you at the gate. They’re convinced in lung circles that methotrexate is the worst drug known to mankind,” he said.

“My take home on methotrexate lung toxicity is this: I would just say, yes, it can occur, but it’s super rare and most often we’re not really sure that it was methotrexate pneumonitis. The diagnosis is not definitive, it’s exclusionary. We know that patients with interstitial lung disease of all types get acute exacerbations, and in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis it’s actually the leading cause of mortality,” the rheumatologist said.

He highlighted a meta-analysis of 22 randomized, double-blind clinical trials published in 1990-2013 of methotrexate versus placebo or active comparators in 8,584 RA patients. The Irish investigators of that meta-analysis found that methotrexate was associated with a small albeit statistically significant 10% increase in the risk of all adverse respiratory events and an 11% increase in the risk of respiratory infection. However, patients on methotrexate were not at increased risk of mortality because of lung disease. And not a single case of methotrexate pneumonitis was reported after 2002 (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Apr;66[4]:803-12).

Methotrexate pneumonitis is not dose dependent, nor is it related to treatment duration.

“Just because your patient has been on methotrexate for years does not mean they won’t get methotrexate lung toxicity,” he cautioned. “But this is not a chronic fibrotic interstitial lung disease, this is an acute onset of peripheral infiltrates and ground glass opacifications on chest imaging.”

Bronchoalveolar lavage classically shows a hypersensitivity pneumonitis with lymphocytosis. Transbronchial or surgical lung biopsy may show an organizing pneumonia or airway-based nonnecrotizing granulomas, again indicative of a hypersensitivity reaction.

Because the diagnostic picture is so often cloudy, Dr. Fischer generally tries to avoid methotrexate in patients with moderate or severe interstitial lung disease. “I have the luxury of avoiding it because we have so many great arthritis drugs these days,” he noted.

“That being said, the notion that we’re going to stop methotrexate in an 80-year-old who’s been on it for years and has mild bibasilar fibrotic interstitial lung disease so that her lung doc can sleep better at night is not very helpful for our patients. If the patient is doing well on methotrexate and the interstitial lung disease is mild, I continue [the methotrexate],” Dr. Fischer said.

He reported receiving research grants from Boehringer Ingelheim and Corbus Pharmaceuticals and serving as a consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim and other pharmaceutical companies.

MAUI, HAWAII – The incidence of methotrexate pneumonitis has been reported as ranging from 3.5% to 7.6% among patients taking the disease-modifying antirheumatic drug. It’s an estimate that Aryeh Fischer, MD, counters with a one-word response: “Nonsense!”

“There’s just no way that methotrexate is causing that much lung disease,” he declared at the 2019 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

Dr. Fischer, a rheumatologist with joint appointments to the divisions of rheumatology and pulmonary sciences and critical care medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, noted that his opinion is considered controversial in the pulmonology world.

“I’m not allowed to talk about methotrexate at lung conferences. They stop you at the gate. They’re convinced in lung circles that methotrexate is the worst drug known to mankind,” he said.

“My take home on methotrexate lung toxicity is this: I would just say, yes, it can occur, but it’s super rare and most often we’re not really sure that it was methotrexate pneumonitis. The diagnosis is not definitive, it’s exclusionary. We know that patients with interstitial lung disease of all types get acute exacerbations, and in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis it’s actually the leading cause of mortality,” the rheumatologist said.

He highlighted a meta-analysis of 22 randomized, double-blind clinical trials published in 1990-2013 of methotrexate versus placebo or active comparators in 8,584 RA patients. The Irish investigators of that meta-analysis found that methotrexate was associated with a small albeit statistically significant 10% increase in the risk of all adverse respiratory events and an 11% increase in the risk of respiratory infection. However, patients on methotrexate were not at increased risk of mortality because of lung disease. And not a single case of methotrexate pneumonitis was reported after 2002 (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Apr;66[4]:803-12).

Methotrexate pneumonitis is not dose dependent, nor is it related to treatment duration.

“Just because your patient has been on methotrexate for years does not mean they won’t get methotrexate lung toxicity,” he cautioned. “But this is not a chronic fibrotic interstitial lung disease, this is an acute onset of peripheral infiltrates and ground glass opacifications on chest imaging.”

Bronchoalveolar lavage classically shows a hypersensitivity pneumonitis with lymphocytosis. Transbronchial or surgical lung biopsy may show an organizing pneumonia or airway-based nonnecrotizing granulomas, again indicative of a hypersensitivity reaction.

Because the diagnostic picture is so often cloudy, Dr. Fischer generally tries to avoid methotrexate in patients with moderate or severe interstitial lung disease. “I have the luxury of avoiding it because we have so many great arthritis drugs these days,” he noted.

“That being said, the notion that we’re going to stop methotrexate in an 80-year-old who’s been on it for years and has mild bibasilar fibrotic interstitial lung disease so that her lung doc can sleep better at night is not very helpful for our patients. If the patient is doing well on methotrexate and the interstitial lung disease is mild, I continue [the methotrexate],” Dr. Fischer said.

He reported receiving research grants from Boehringer Ingelheim and Corbus Pharmaceuticals and serving as a consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim and other pharmaceutical companies.

MAUI, HAWAII – The incidence of methotrexate pneumonitis has been reported as ranging from 3.5% to 7.6% among patients taking the disease-modifying antirheumatic drug. It’s an estimate that Aryeh Fischer, MD, counters with a one-word response: “Nonsense!”

“There’s just no way that methotrexate is causing that much lung disease,” he declared at the 2019 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

Dr. Fischer, a rheumatologist with joint appointments to the divisions of rheumatology and pulmonary sciences and critical care medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, noted that his opinion is considered controversial in the pulmonology world.

“I’m not allowed to talk about methotrexate at lung conferences. They stop you at the gate. They’re convinced in lung circles that methotrexate is the worst drug known to mankind,” he said.

“My take home on methotrexate lung toxicity is this: I would just say, yes, it can occur, but it’s super rare and most often we’re not really sure that it was methotrexate pneumonitis. The diagnosis is not definitive, it’s exclusionary. We know that patients with interstitial lung disease of all types get acute exacerbations, and in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis it’s actually the leading cause of mortality,” the rheumatologist said.

He highlighted a meta-analysis of 22 randomized, double-blind clinical trials published in 1990-2013 of methotrexate versus placebo or active comparators in 8,584 RA patients. The Irish investigators of that meta-analysis found that methotrexate was associated with a small albeit statistically significant 10% increase in the risk of all adverse respiratory events and an 11% increase in the risk of respiratory infection. However, patients on methotrexate were not at increased risk of mortality because of lung disease. And not a single case of methotrexate pneumonitis was reported after 2002 (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Apr;66[4]:803-12).

Methotrexate pneumonitis is not dose dependent, nor is it related to treatment duration.

“Just because your patient has been on methotrexate for years does not mean they won’t get methotrexate lung toxicity,” he cautioned. “But this is not a chronic fibrotic interstitial lung disease, this is an acute onset of peripheral infiltrates and ground glass opacifications on chest imaging.”

Bronchoalveolar lavage classically shows a hypersensitivity pneumonitis with lymphocytosis. Transbronchial or surgical lung biopsy may show an organizing pneumonia or airway-based nonnecrotizing granulomas, again indicative of a hypersensitivity reaction.

Because the diagnostic picture is so often cloudy, Dr. Fischer generally tries to avoid methotrexate in patients with moderate or severe interstitial lung disease. “I have the luxury of avoiding it because we have so many great arthritis drugs these days,” he noted.

“That being said, the notion that we’re going to stop methotrexate in an 80-year-old who’s been on it for years and has mild bibasilar fibrotic interstitial lung disease so that her lung doc can sleep better at night is not very helpful for our patients. If the patient is doing well on methotrexate and the interstitial lung disease is mild, I continue [the methotrexate],” Dr. Fischer said.

He reported receiving research grants from Boehringer Ingelheim and Corbus Pharmaceuticals and serving as a consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim and other pharmaceutical companies.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM RWCS 2019

Surprise! MTX proves effective in psoriatic arthritis

MAUI, HAWAII – The first-ever, double-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial evidence demonstrating that methotrexate indeed has therapeutic efficacy in psoriatic arthritis has come at an awkward time – on the heels of a basically negative Cochrane Collaboration systematic review as well as the latest American College of Rheumatology/National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines for treatment of psoriatic arthritis, which recommend anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy as first line, ahead of methotrexate.

The timing of the release of the SEAM-PsA randomized trial results was such that neither the Cochrane group nor the ACR/NPF guideline committee was able to consider the new, potentially game-changing study findings.

“I look at SEAM-PsA and have to say, methotrexate does seem to be an effective therapy. I think it calls into question the new guidelines, which were developed before the data were out. Now you look at this and have to ask, can you really say you should use a TNF inhibitor before methotrexate based on these results? I don’t know,” Eric M. Ruderman, MD, said at the 2019 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

He also shared other problems he has with the new guidelines, which he considers seriously flawed.

The Cochrane Collaboration Systematic Review

The Cochrane group cast a net for all randomized, controlled clinical trials of methotrexate versus placebo or another disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD). They found eight, which they judged to be of poor quality. Their conclusion: “Low-quality evidence suggests that low-dose (15 mg or less) oral methotrexate might be slightly more effective than placebo when taken for 6 months; however, we are uncertain if it is more harmful” (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Jan 18;1:CD012722. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012722.pub2).

“The new Cochrane Review concludes methotrexate doesn’t seem to work that well,” observed symposium director Arthur Kavanaugh, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

“That’s because it’s based on published data, and there’s been very little of that,” said Dr. Ruderman, professor of medicine and associate chief for clinical affairs in the division of rheumatology at Northwestern University in Chicago.

“I think most people assume, based on clinical experience, that it does work well. It’s all we had for years and years and years,” he added.

That is, until SEAM-PsA.

SEAM-PsA

SEAM-PsA randomized 851 DMARD- and biologic-naive patients with a median 0.6-year duration of psoriatic arthritis to one of three treatment arms for 48 weeks: once-weekly etanercept at 50 mg plus oral methotrexate at 20 mg, etanercept plus oral placebo, or methotrexate plus injectable placebo.

This is a study that will reshape clinical practice for many rheumatologists, according to Dr. Kavanaugh. The hypothesis was that in psoriatic arthritis, just as has been shown to be the case in rheumatoid arthritis, the combination of a TNF inhibitor plus methotrexate would have greater efficacy than either agent alone. But the study brought a couple of major surprises.

“Methotrexate didn’t do so badly,” Dr. Kavanaugh observed. “And the combination did nothing. I would have bet that the combination would have shown methotrexate had a synergistic effect with the TNF inhibitor, especially for x-ray changes. But the combination didn’t do any better than etanercept alone.”

Make no mistake: Etanercept monotherapy significantly outperformed methotrexate monotherapy for the primary endpoint, the ACR 20 response at week 24, by a margin of 60.9% versus 50.7%. Dr. Ruderman deemed that methotrexate response rate to be quite respectable, although he bemoaned the absence of a double-placebo comparator arm. And the key secondary endpoint, the minimal disease activity response rate at week 24, was also significantly better with etanercept, at 35.9% compared with 22.9%. Moreover, both etanercept arms showed significantly less radiographic progression than with methotrexate alone.

However, that was it. There were no significant differences between etanercept and methotrexate in other secondary endpoints, including the Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada Enthesitis Index (SPARCC), the Disease Activity in PSoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA) score, the Leeds Dactylitis Instrument (LDI), and quality of life as assessed by the 36-item Short Form Health Survey total score.

“Methotrexate showed generally good efficacy across multiple domains,” the investigators concluded (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Feb 12. doi: 10.1002/art.40851).

“Another intriguing thing to come out of this study for me were the enthesitis and dactylitis results. My clinical experience suggested methotrexate wasn’t so great for that, but this study suggests that’s not true,” Dr. Ruderman said.

“There are a couple of key take-home points from this study,” according to Dr. Kavanaugh. “One is that the combination is not synergistic. When you start a rheumatoid arthritis patient on methotrexate, you try to keep him on methotrexate when you add a TNF inhibitor. This study would say there doesn’t seem like there’s a reason to do that in your psoriatic arthritis patient. And the second message is that methotrexate seems to work.”

New ACR/NPF psoriatic arthritis guidelines under fire

“The new guidelines are fuzzy, aren’t they?” Dr. Kavanaugh said in lobbing the topic over to Dr. Ruderman.

“Where do we start?” he replied, shaking his head. “These are evidence-based guidelines in an area in which there was virtually no evidence.”

Indeed, the guidelines committee proudly employed the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology, which forces committee members to issue “conditional” recommendations when there’s not enough evidence to make a “strong” recommendation.

“You’re not allowed to say, ‘We don’t know, there’s not enough evidence to make a choice,’ ” Dr. Ruderman said. “The problem with these guidelines is virtually everything in it is a conditional recommendation except ‘stop smoking,’ which was a strong recommendation.

“A conditional recommendation is pretty much a fancy term for expert opinion. It’s basically everybody in the room saying, ‘This is what we think.’ And that makes guidelines challenging because as a rheumatologist, you’re an expert. The people in the room have perhaps looked at the data more carefully than you’ve drilled down into the studies, but ultimately they’ve taken care of these patients and you’ve taken care of these patients, so why is their opinion better than your opinion, if it’s an informed opinion?”

His other critique of the 28-page guidelines is they don’t include the reasoning behind the conditional recommendations.

“If the conditional recommendation is, ‘In this situation, a TNF inhibitor is preferred over an IL-17 inhibitor,’ that would be great if they had also said, ‘This is why we thought that.’ But that’s not in the paper,” Dr. Ruderman said.

He and Dr. Kavanaugh reported serving as consultants to numerous pharmaceutical companies.

MAUI, HAWAII – The first-ever, double-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial evidence demonstrating that methotrexate indeed has therapeutic efficacy in psoriatic arthritis has come at an awkward time – on the heels of a basically negative Cochrane Collaboration systematic review as well as the latest American College of Rheumatology/National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines for treatment of psoriatic arthritis, which recommend anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy as first line, ahead of methotrexate.

The timing of the release of the SEAM-PsA randomized trial results was such that neither the Cochrane group nor the ACR/NPF guideline committee was able to consider the new, potentially game-changing study findings.

“I look at SEAM-PsA and have to say, methotrexate does seem to be an effective therapy. I think it calls into question the new guidelines, which were developed before the data were out. Now you look at this and have to ask, can you really say you should use a TNF inhibitor before methotrexate based on these results? I don’t know,” Eric M. Ruderman, MD, said at the 2019 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

He also shared other problems he has with the new guidelines, which he considers seriously flawed.

The Cochrane Collaboration Systematic Review

The Cochrane group cast a net for all randomized, controlled clinical trials of methotrexate versus placebo or another disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD). They found eight, which they judged to be of poor quality. Their conclusion: “Low-quality evidence suggests that low-dose (15 mg or less) oral methotrexate might be slightly more effective than placebo when taken for 6 months; however, we are uncertain if it is more harmful” (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Jan 18;1:CD012722. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012722.pub2).

“The new Cochrane Review concludes methotrexate doesn’t seem to work that well,” observed symposium director Arthur Kavanaugh, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

“That’s because it’s based on published data, and there’s been very little of that,” said Dr. Ruderman, professor of medicine and associate chief for clinical affairs in the division of rheumatology at Northwestern University in Chicago.

“I think most people assume, based on clinical experience, that it does work well. It’s all we had for years and years and years,” he added.

That is, until SEAM-PsA.

SEAM-PsA

SEAM-PsA randomized 851 DMARD- and biologic-naive patients with a median 0.6-year duration of psoriatic arthritis to one of three treatment arms for 48 weeks: once-weekly etanercept at 50 mg plus oral methotrexate at 20 mg, etanercept plus oral placebo, or methotrexate plus injectable placebo.

This is a study that will reshape clinical practice for many rheumatologists, according to Dr. Kavanaugh. The hypothesis was that in psoriatic arthritis, just as has been shown to be the case in rheumatoid arthritis, the combination of a TNF inhibitor plus methotrexate would have greater efficacy than either agent alone. But the study brought a couple of major surprises.

“Methotrexate didn’t do so badly,” Dr. Kavanaugh observed. “And the combination did nothing. I would have bet that the combination would have shown methotrexate had a synergistic effect with the TNF inhibitor, especially for x-ray changes. But the combination didn’t do any better than etanercept alone.”

Make no mistake: Etanercept monotherapy significantly outperformed methotrexate monotherapy for the primary endpoint, the ACR 20 response at week 24, by a margin of 60.9% versus 50.7%. Dr. Ruderman deemed that methotrexate response rate to be quite respectable, although he bemoaned the absence of a double-placebo comparator arm. And the key secondary endpoint, the minimal disease activity response rate at week 24, was also significantly better with etanercept, at 35.9% compared with 22.9%. Moreover, both etanercept arms showed significantly less radiographic progression than with methotrexate alone.

However, that was it. There were no significant differences between etanercept and methotrexate in other secondary endpoints, including the Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada Enthesitis Index (SPARCC), the Disease Activity in PSoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA) score, the Leeds Dactylitis Instrument (LDI), and quality of life as assessed by the 36-item Short Form Health Survey total score.

“Methotrexate showed generally good efficacy across multiple domains,” the investigators concluded (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Feb 12. doi: 10.1002/art.40851).

“Another intriguing thing to come out of this study for me were the enthesitis and dactylitis results. My clinical experience suggested methotrexate wasn’t so great for that, but this study suggests that’s not true,” Dr. Ruderman said.

“There are a couple of key take-home points from this study,” according to Dr. Kavanaugh. “One is that the combination is not synergistic. When you start a rheumatoid arthritis patient on methotrexate, you try to keep him on methotrexate when you add a TNF inhibitor. This study would say there doesn’t seem like there’s a reason to do that in your psoriatic arthritis patient. And the second message is that methotrexate seems to work.”

New ACR/NPF psoriatic arthritis guidelines under fire

“The new guidelines are fuzzy, aren’t they?” Dr. Kavanaugh said in lobbing the topic over to Dr. Ruderman.

“Where do we start?” he replied, shaking his head. “These are evidence-based guidelines in an area in which there was virtually no evidence.”

Indeed, the guidelines committee proudly employed the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology, which forces committee members to issue “conditional” recommendations when there’s not enough evidence to make a “strong” recommendation.

“You’re not allowed to say, ‘We don’t know, there’s not enough evidence to make a choice,’ ” Dr. Ruderman said. “The problem with these guidelines is virtually everything in it is a conditional recommendation except ‘stop smoking,’ which was a strong recommendation.

“A conditional recommendation is pretty much a fancy term for expert opinion. It’s basically everybody in the room saying, ‘This is what we think.’ And that makes guidelines challenging because as a rheumatologist, you’re an expert. The people in the room have perhaps looked at the data more carefully than you’ve drilled down into the studies, but ultimately they’ve taken care of these patients and you’ve taken care of these patients, so why is their opinion better than your opinion, if it’s an informed opinion?”

His other critique of the 28-page guidelines is they don’t include the reasoning behind the conditional recommendations.

“If the conditional recommendation is, ‘In this situation, a TNF inhibitor is preferred over an IL-17 inhibitor,’ that would be great if they had also said, ‘This is why we thought that.’ But that’s not in the paper,” Dr. Ruderman said.

He and Dr. Kavanaugh reported serving as consultants to numerous pharmaceutical companies.

MAUI, HAWAII – The first-ever, double-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial evidence demonstrating that methotrexate indeed has therapeutic efficacy in psoriatic arthritis has come at an awkward time – on the heels of a basically negative Cochrane Collaboration systematic review as well as the latest American College of Rheumatology/National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines for treatment of psoriatic arthritis, which recommend anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy as first line, ahead of methotrexate.

The timing of the release of the SEAM-PsA randomized trial results was such that neither the Cochrane group nor the ACR/NPF guideline committee was able to consider the new, potentially game-changing study findings.

“I look at SEAM-PsA and have to say, methotrexate does seem to be an effective therapy. I think it calls into question the new guidelines, which were developed before the data were out. Now you look at this and have to ask, can you really say you should use a TNF inhibitor before methotrexate based on these results? I don’t know,” Eric M. Ruderman, MD, said at the 2019 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

He also shared other problems he has with the new guidelines, which he considers seriously flawed.

The Cochrane Collaboration Systematic Review

The Cochrane group cast a net for all randomized, controlled clinical trials of methotrexate versus placebo or another disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD). They found eight, which they judged to be of poor quality. Their conclusion: “Low-quality evidence suggests that low-dose (15 mg or less) oral methotrexate might be slightly more effective than placebo when taken for 6 months; however, we are uncertain if it is more harmful” (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Jan 18;1:CD012722. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012722.pub2).

“The new Cochrane Review concludes methotrexate doesn’t seem to work that well,” observed symposium director Arthur Kavanaugh, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

“That’s because it’s based on published data, and there’s been very little of that,” said Dr. Ruderman, professor of medicine and associate chief for clinical affairs in the division of rheumatology at Northwestern University in Chicago.

“I think most people assume, based on clinical experience, that it does work well. It’s all we had for years and years and years,” he added.

That is, until SEAM-PsA.

SEAM-PsA

SEAM-PsA randomized 851 DMARD- and biologic-naive patients with a median 0.6-year duration of psoriatic arthritis to one of three treatment arms for 48 weeks: once-weekly etanercept at 50 mg plus oral methotrexate at 20 mg, etanercept plus oral placebo, or methotrexate plus injectable placebo.

This is a study that will reshape clinical practice for many rheumatologists, according to Dr. Kavanaugh. The hypothesis was that in psoriatic arthritis, just as has been shown to be the case in rheumatoid arthritis, the combination of a TNF inhibitor plus methotrexate would have greater efficacy than either agent alone. But the study brought a couple of major surprises.

“Methotrexate didn’t do so badly,” Dr. Kavanaugh observed. “And the combination did nothing. I would have bet that the combination would have shown methotrexate had a synergistic effect with the TNF inhibitor, especially for x-ray changes. But the combination didn’t do any better than etanercept alone.”

Make no mistake: Etanercept monotherapy significantly outperformed methotrexate monotherapy for the primary endpoint, the ACR 20 response at week 24, by a margin of 60.9% versus 50.7%. Dr. Ruderman deemed that methotrexate response rate to be quite respectable, although he bemoaned the absence of a double-placebo comparator arm. And the key secondary endpoint, the minimal disease activity response rate at week 24, was also significantly better with etanercept, at 35.9% compared with 22.9%. Moreover, both etanercept arms showed significantly less radiographic progression than with methotrexate alone.

However, that was it. There were no significant differences between etanercept and methotrexate in other secondary endpoints, including the Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada Enthesitis Index (SPARCC), the Disease Activity in PSoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA) score, the Leeds Dactylitis Instrument (LDI), and quality of life as assessed by the 36-item Short Form Health Survey total score.

“Methotrexate showed generally good efficacy across multiple domains,” the investigators concluded (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Feb 12. doi: 10.1002/art.40851).

“Another intriguing thing to come out of this study for me were the enthesitis and dactylitis results. My clinical experience suggested methotrexate wasn’t so great for that, but this study suggests that’s not true,” Dr. Ruderman said.

“There are a couple of key take-home points from this study,” according to Dr. Kavanaugh. “One is that the combination is not synergistic. When you start a rheumatoid arthritis patient on methotrexate, you try to keep him on methotrexate when you add a TNF inhibitor. This study would say there doesn’t seem like there’s a reason to do that in your psoriatic arthritis patient. And the second message is that methotrexate seems to work.”

New ACR/NPF psoriatic arthritis guidelines under fire

“The new guidelines are fuzzy, aren’t they?” Dr. Kavanaugh said in lobbing the topic over to Dr. Ruderman.

“Where do we start?” he replied, shaking his head. “These are evidence-based guidelines in an area in which there was virtually no evidence.”

Indeed, the guidelines committee proudly employed the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology, which forces committee members to issue “conditional” recommendations when there’s not enough evidence to make a “strong” recommendation.

“You’re not allowed to say, ‘We don’t know, there’s not enough evidence to make a choice,’ ” Dr. Ruderman said. “The problem with these guidelines is virtually everything in it is a conditional recommendation except ‘stop smoking,’ which was a strong recommendation.

“A conditional recommendation is pretty much a fancy term for expert opinion. It’s basically everybody in the room saying, ‘This is what we think.’ And that makes guidelines challenging because as a rheumatologist, you’re an expert. The people in the room have perhaps looked at the data more carefully than you’ve drilled down into the studies, but ultimately they’ve taken care of these patients and you’ve taken care of these patients, so why is their opinion better than your opinion, if it’s an informed opinion?”

His other critique of the 28-page guidelines is they don’t include the reasoning behind the conditional recommendations.

“If the conditional recommendation is, ‘In this situation, a TNF inhibitor is preferred over an IL-17 inhibitor,’ that would be great if they had also said, ‘This is why we thought that.’ But that’s not in the paper,” Dr. Ruderman said.

He and Dr. Kavanaugh reported serving as consultants to numerous pharmaceutical companies.

REPORTING FROM RWCS 2019

Lymphoma rate in RA patients is falling

MAUI, HAWAII – The incidence of lymphoma in patients with RA appears to have been dropping during the past 2 decades – and for rheumatologists, that’s news you can use.

“I think this is encouraging data about where we’re headed with therapy. And it’s encouraging data for your patients, that maybe more effective therapies can lead to a lower risk of cancer,” John J. Cush, MD, commented at the 2019 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“Patients are always worried about cancer,” observed symposium director Arthur Kavanaugh, MD. “I think this is very useful data to bring to a discussion with patients.”

The study they highlighted was presented at the 2018 annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology by Namrata Singh, MD, of the University of Iowa, Iowa City and coinvestigators from Veterans Affairs medical centers around the country. They analyzed the incidence of lymphomas as well as all-site cancers in 50,870 men with RA in the national VA health care system during 2001-2015 and compared the rates with the background rates in the general U.S. population as captured in the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program.

The key finding: While the standardized incidence ratio for the development of lymphoma in the RA patients during 2001-2005 was 190% greater than in the SEER population, the SIR dropped to 1.6 in 2006-2010 and stayed low in 2011-2015.

“These are the only data I’m aware of that say maybe lymphomas are becoming less frequent among RA patients,” said Dr. Kavanaugh, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Historically, RA has been associated with roughly a 100% increased risk of lymphoma. The source of the increased risk has been a matter of controversy: Is it the result of immunostimulation triggered by high RA disease activity, or a side effect of the drugs employed in treatment of the disease? The clear implication of the VA study is that it’s all about disease activity.

“The lymphoma rate is higher early in the use of our new therapies, in 2001-2005, because the patients who went on TNF [tumor necrosis factor] inhibitors then had the most disease activity. But with time, patients are getting those treatments earlier. Does this [lower lymphoma rate] reflect a change in the practice of rheumatology? I think it does,” according to Dr. Cush, professor of medicine and rheumatology at Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas.

Dr. Kavanaugh agreed. “Now, if we’re treating early and treating to target, we should see less lymphomas than we did back in the day.”

The rate of cancers at all sites in the VA RA patients has been going down as well, with the SIR dropping from 1.8 in 2001-2005 to close to 1, the background rate in the general population.

“What’s great about this study is this is a large data set. You really can’t compare an RA population on and off treatment. The right comparison is to a normal population – and SEER accounts for something like 14% of the U.S. population,” Dr. Cush said.

Previous support for the notion that the increased lymphoma risk associated with RA was a function of disease activity came from a Swedish study of 378 RA patients in the prebiologic era who developed lymphoma and a matched cohort of 378 others without lymphoma. The investigators found that patients with moderate overall RA disease activity were at a 700% increased risk of lymphoma, compared with those with low overall disease activity, and that patients with high RA disease activity were at a 6,900% increased risk (Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Mar;54[3]:692-701). But that was a cross-sectional study, whereas the VA study examined trends over time.

The VA RA cohort had a mean age of 64 years. About 60% were current or ex-smokers, 65% were positive for rheumatoid factor, and 62% were positive for anticyclic citrullinated peptide.

Dr. Kavanaugh said that, because of the potential for referral bias in the VA study, he’s eager to see the findings reproduced in another data set.

Both Dr. Cush and Dr. Kavanaugh reported serving as a consultant to and/or receiving research funding from numerous pharmaceutical companies.

MAUI, HAWAII – The incidence of lymphoma in patients with RA appears to have been dropping during the past 2 decades – and for rheumatologists, that’s news you can use.

“I think this is encouraging data about where we’re headed with therapy. And it’s encouraging data for your patients, that maybe more effective therapies can lead to a lower risk of cancer,” John J. Cush, MD, commented at the 2019 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“Patients are always worried about cancer,” observed symposium director Arthur Kavanaugh, MD. “I think this is very useful data to bring to a discussion with patients.”