User login

Epilepsy

Resting State Functional Connectivity Signals Medication Resistance

Altered thalamo-hippocampal resting state functional brain connectivity may serve as a biomarker to signal treatment resistance in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) suggests a recent study of 286 patients with epilepsy.

- Researchers from Rockefeller University reviewed data from a database that included resting state functional MRI readings.

- The analysis included seizure characterization, EEG indications of lateralization, and localization of seizure foci.

- The investigators compared records from patients with well-controlled TLE to those with treatment resistant disease and healthy controls.

- Treatment resistant patients had a significant bilateral decrease in thalamo-hippocampal functional connectivity.

Pressl C, Brandner P, Schaffelhofer S, et al. Resting state functional connectivity patterns associated with pharmacological treatment resistance in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2019;149:37-43.

Altered thalamo-hippocampal resting state functional brain connectivity may serve as a biomarker to signal treatment resistance in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) suggests a recent study of 286 patients with epilepsy.

- Researchers from Rockefeller University reviewed data from a database that included resting state functional MRI readings.

- The analysis included seizure characterization, EEG indications of lateralization, and localization of seizure foci.

- The investigators compared records from patients with well-controlled TLE to those with treatment resistant disease and healthy controls.

- Treatment resistant patients had a significant bilateral decrease in thalamo-hippocampal functional connectivity.

Pressl C, Brandner P, Schaffelhofer S, et al. Resting state functional connectivity patterns associated with pharmacological treatment resistance in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2019;149:37-43.

Altered thalamo-hippocampal resting state functional brain connectivity may serve as a biomarker to signal treatment resistance in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) suggests a recent study of 286 patients with epilepsy.

- Researchers from Rockefeller University reviewed data from a database that included resting state functional MRI readings.

- The analysis included seizure characterization, EEG indications of lateralization, and localization of seizure foci.

- The investigators compared records from patients with well-controlled TLE to those with treatment resistant disease and healthy controls.

- Treatment resistant patients had a significant bilateral decrease in thalamo-hippocampal functional connectivity.

Pressl C, Brandner P, Schaffelhofer S, et al. Resting state functional connectivity patterns associated with pharmacological treatment resistance in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2019;149:37-43.

Don’t Delay Drug Therapy in Children with Status Epilepticus

Delaying the first dose of antiseizure medication in children with status epilepticus will likely prolong the condition, according a report published in Epilepsy Research.

- Investigators from the Division of Child Neurology at Children’s National Health System in Washington, DC, evaluated the timing and selection of antiseizure medication in children presenting at a pediatric emergency department.

- Among 141 patients with status epilepticus (SE), median age 45 months, SE lasted 61.5 min (median).

- Median time to receipt of the first dose of antiseizure drug was 25 min.

- Ninety two percent of patients received a benzodiazepine as the first drug.

- A benzodiazepine was the second dose antiseizure medication in 95% of patients.

- Among patients who received the first dose of medication in less than 5 minutes, seizures lasted 59.5 min (median) while children who did not receive their first dose for an hour or more after seizure experienced a duration of 151.5 min.

Cohen NT, Chamberlain JM, Gaillard WD. Timing and selection of first antiseizure medication in patients with pediatric status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2019;149:21-25.

Delaying the first dose of antiseizure medication in children with status epilepticus will likely prolong the condition, according a report published in Epilepsy Research.

- Investigators from the Division of Child Neurology at Children’s National Health System in Washington, DC, evaluated the timing and selection of antiseizure medication in children presenting at a pediatric emergency department.

- Among 141 patients with status epilepticus (SE), median age 45 months, SE lasted 61.5 min (median).

- Median time to receipt of the first dose of antiseizure drug was 25 min.

- Ninety two percent of patients received a benzodiazepine as the first drug.

- A benzodiazepine was the second dose antiseizure medication in 95% of patients.

- Among patients who received the first dose of medication in less than 5 minutes, seizures lasted 59.5 min (median) while children who did not receive their first dose for an hour or more after seizure experienced a duration of 151.5 min.

Cohen NT, Chamberlain JM, Gaillard WD. Timing and selection of first antiseizure medication in patients with pediatric status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2019;149:21-25.

Delaying the first dose of antiseizure medication in children with status epilepticus will likely prolong the condition, according a report published in Epilepsy Research.

- Investigators from the Division of Child Neurology at Children’s National Health System in Washington, DC, evaluated the timing and selection of antiseizure medication in children presenting at a pediatric emergency department.

- Among 141 patients with status epilepticus (SE), median age 45 months, SE lasted 61.5 min (median).

- Median time to receipt of the first dose of antiseizure drug was 25 min.

- Ninety two percent of patients received a benzodiazepine as the first drug.

- A benzodiazepine was the second dose antiseizure medication in 95% of patients.

- Among patients who received the first dose of medication in less than 5 minutes, seizures lasted 59.5 min (median) while children who did not receive their first dose for an hour or more after seizure experienced a duration of 151.5 min.

Cohen NT, Chamberlain JM, Gaillard WD. Timing and selection of first antiseizure medication in patients with pediatric status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2019;149:21-25.

Prenatal valproate exposure raises ADHD risk

Children exposed to valproate in utero were 48% more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD when compared with unexposed children in a population-based cohort study of more than 900,000 children in Denmark.

Antiepileptic drug exposure is associated with an increased risk of various congenital malformations, but its role in the development of ADHD in children has not been well documented, first author Jakob Christensen, MD, PhD, DrMedSci, of Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital, and his colleagues wrote in their paper, published online Jan. 4 in JAMA Network Open.

The researchers identified 913,302 singleton births in Denmark from 1997 through 2011, with children followed through 2015.

Overall, children who were prenatally exposed to valproate had a 48% increased risk of ADHD. Antiepileptic drug exposure was defined as 30 days before the estimated day of conception to the day of birth, and included valproate, clobazam, and other antiepileptic drugs. The average age of the children at the study’s end was 10 years, and approximately half were male.

A total of 580 children were exposed to valproate in utero; of these, 8.4% were later diagnosed with ADHD, compared with 3.2% of 912,722 children who were not exposed to valproate. In addition, the absolute 15-year risk of ADHD was 11% in valproate-exposed children vs. 4.6% in unexposed children. No significant associations appeared between ADHD and other antiepileptic drugs.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the contraindication of valproate for use in pregnancy, which may mean that the women taking valproate had more severe disease, the researchers noted.

“Due to the observational nature of this study, we cannot rule out that the observed risk increase for ADHD is at least in part explained by the mother’s health condition that triggered the prescription of valproate during pregnancy,” they said. Other limitations included a lack of data on the exact amounts of valproate taken during pregnancy and the potential impact of nonepilepsy medications, they noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large size and population-based cohort, and support warnings by professional medical organizations against valproate use in pregnancy, the researchers said. “As randomized clinical trials of valproate use during pregnancy are neither feasible nor ethical, our study provides clinical information on the risk of ADHD associated with valproate use during pregnancy,” they concluded.

The study was supported by grants to various authors from the Danish Epilepsy Association Central Denmark Region, the Aarhus University Research Foundation, the Lundbeck Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the Novo Nordisk Foundation, and the European Commission.

SOURCE: Christensen J et al. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(1):e186606. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6606.

The data from the current study differ from a recent meta-analysis of five studies that did not find a statistically significant increase in ADHD risk in children associated with prenatal valproate exposure, Kimford J. Meador, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA Network Open. 2019;2[1]:e186603. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6603).

“The discrepancy between the present study and the prior meta-analysis might be due to the meta-analysis using different analytical approaches and examining studies with smaller sample sizes, higher attrition rates, shorter follow-ups, and cohort differences,” Dr. Meador said. “Nevertheless, the findings by Christensen et al. are consistent with multiple studies demonstrating adverse neurodevelopmental effects associated with fetal valproate exposure.”

Given the potential risks associated with valproate exposure not only for behavior problems such as ADHD but also for congenital malformations and other cognitive and behavioral issues in children, women of childbearing age who are using valproate or considering a prescription should be counseled for informed consent, Dr. Meador said.

Dr. Meador advocated additional research on the impact of antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy and risk assessment strategies, including “a national reporting system for congenital malformations, routine preclinical testing of all new antiseizure medications for neurodevelopmental effects, monitoring of antiseizure medication prescription practices for women of childbearing age to determine whether emerging knowledge is being appropriately applied, and improved funding of basic and clinical research to fully delineate risks and underlying mechanisms of anatomical and behavioral teratogenesis from antiseizure medications.”

Dr. Meador is affiliated with the department of neurology and neurological sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University. He disclosed research support from the National Institutes of Health and Sunovion, and travel support from UCB. The Epilepsy Study Consortium pays Stanford University for his research consultant time related to Eisai, GW Pharmaceuticals, NeuroPace, Novartis, Supernus, Upsher-Smith Laboratories, UCB, and Vivus.

The data from the current study differ from a recent meta-analysis of five studies that did not find a statistically significant increase in ADHD risk in children associated with prenatal valproate exposure, Kimford J. Meador, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA Network Open. 2019;2[1]:e186603. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6603).

“The discrepancy between the present study and the prior meta-analysis might be due to the meta-analysis using different analytical approaches and examining studies with smaller sample sizes, higher attrition rates, shorter follow-ups, and cohort differences,” Dr. Meador said. “Nevertheless, the findings by Christensen et al. are consistent with multiple studies demonstrating adverse neurodevelopmental effects associated with fetal valproate exposure.”

Given the potential risks associated with valproate exposure not only for behavior problems such as ADHD but also for congenital malformations and other cognitive and behavioral issues in children, women of childbearing age who are using valproate or considering a prescription should be counseled for informed consent, Dr. Meador said.

Dr. Meador advocated additional research on the impact of antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy and risk assessment strategies, including “a national reporting system for congenital malformations, routine preclinical testing of all new antiseizure medications for neurodevelopmental effects, monitoring of antiseizure medication prescription practices for women of childbearing age to determine whether emerging knowledge is being appropriately applied, and improved funding of basic and clinical research to fully delineate risks and underlying mechanisms of anatomical and behavioral teratogenesis from antiseizure medications.”

Dr. Meador is affiliated with the department of neurology and neurological sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University. He disclosed research support from the National Institutes of Health and Sunovion, and travel support from UCB. The Epilepsy Study Consortium pays Stanford University for his research consultant time related to Eisai, GW Pharmaceuticals, NeuroPace, Novartis, Supernus, Upsher-Smith Laboratories, UCB, and Vivus.

The data from the current study differ from a recent meta-analysis of five studies that did not find a statistically significant increase in ADHD risk in children associated with prenatal valproate exposure, Kimford J. Meador, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA Network Open. 2019;2[1]:e186603. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6603).

“The discrepancy between the present study and the prior meta-analysis might be due to the meta-analysis using different analytical approaches and examining studies with smaller sample sizes, higher attrition rates, shorter follow-ups, and cohort differences,” Dr. Meador said. “Nevertheless, the findings by Christensen et al. are consistent with multiple studies demonstrating adverse neurodevelopmental effects associated with fetal valproate exposure.”

Given the potential risks associated with valproate exposure not only for behavior problems such as ADHD but also for congenital malformations and other cognitive and behavioral issues in children, women of childbearing age who are using valproate or considering a prescription should be counseled for informed consent, Dr. Meador said.

Dr. Meador advocated additional research on the impact of antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy and risk assessment strategies, including “a national reporting system for congenital malformations, routine preclinical testing of all new antiseizure medications for neurodevelopmental effects, monitoring of antiseizure medication prescription practices for women of childbearing age to determine whether emerging knowledge is being appropriately applied, and improved funding of basic and clinical research to fully delineate risks and underlying mechanisms of anatomical and behavioral teratogenesis from antiseizure medications.”

Dr. Meador is affiliated with the department of neurology and neurological sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University. He disclosed research support from the National Institutes of Health and Sunovion, and travel support from UCB. The Epilepsy Study Consortium pays Stanford University for his research consultant time related to Eisai, GW Pharmaceuticals, NeuroPace, Novartis, Supernus, Upsher-Smith Laboratories, UCB, and Vivus.

Children exposed to valproate in utero were 48% more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD when compared with unexposed children in a population-based cohort study of more than 900,000 children in Denmark.

Antiepileptic drug exposure is associated with an increased risk of various congenital malformations, but its role in the development of ADHD in children has not been well documented, first author Jakob Christensen, MD, PhD, DrMedSci, of Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital, and his colleagues wrote in their paper, published online Jan. 4 in JAMA Network Open.

The researchers identified 913,302 singleton births in Denmark from 1997 through 2011, with children followed through 2015.

Overall, children who were prenatally exposed to valproate had a 48% increased risk of ADHD. Antiepileptic drug exposure was defined as 30 days before the estimated day of conception to the day of birth, and included valproate, clobazam, and other antiepileptic drugs. The average age of the children at the study’s end was 10 years, and approximately half were male.

A total of 580 children were exposed to valproate in utero; of these, 8.4% were later diagnosed with ADHD, compared with 3.2% of 912,722 children who were not exposed to valproate. In addition, the absolute 15-year risk of ADHD was 11% in valproate-exposed children vs. 4.6% in unexposed children. No significant associations appeared between ADHD and other antiepileptic drugs.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the contraindication of valproate for use in pregnancy, which may mean that the women taking valproate had more severe disease, the researchers noted.

“Due to the observational nature of this study, we cannot rule out that the observed risk increase for ADHD is at least in part explained by the mother’s health condition that triggered the prescription of valproate during pregnancy,” they said. Other limitations included a lack of data on the exact amounts of valproate taken during pregnancy and the potential impact of nonepilepsy medications, they noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large size and population-based cohort, and support warnings by professional medical organizations against valproate use in pregnancy, the researchers said. “As randomized clinical trials of valproate use during pregnancy are neither feasible nor ethical, our study provides clinical information on the risk of ADHD associated with valproate use during pregnancy,” they concluded.

The study was supported by grants to various authors from the Danish Epilepsy Association Central Denmark Region, the Aarhus University Research Foundation, the Lundbeck Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the Novo Nordisk Foundation, and the European Commission.

SOURCE: Christensen J et al. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(1):e186606. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6606.

Children exposed to valproate in utero were 48% more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD when compared with unexposed children in a population-based cohort study of more than 900,000 children in Denmark.

Antiepileptic drug exposure is associated with an increased risk of various congenital malformations, but its role in the development of ADHD in children has not been well documented, first author Jakob Christensen, MD, PhD, DrMedSci, of Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital, and his colleagues wrote in their paper, published online Jan. 4 in JAMA Network Open.

The researchers identified 913,302 singleton births in Denmark from 1997 through 2011, with children followed through 2015.

Overall, children who were prenatally exposed to valproate had a 48% increased risk of ADHD. Antiepileptic drug exposure was defined as 30 days before the estimated day of conception to the day of birth, and included valproate, clobazam, and other antiepileptic drugs. The average age of the children at the study’s end was 10 years, and approximately half were male.

A total of 580 children were exposed to valproate in utero; of these, 8.4% were later diagnosed with ADHD, compared with 3.2% of 912,722 children who were not exposed to valproate. In addition, the absolute 15-year risk of ADHD was 11% in valproate-exposed children vs. 4.6% in unexposed children. No significant associations appeared between ADHD and other antiepileptic drugs.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the contraindication of valproate for use in pregnancy, which may mean that the women taking valproate had more severe disease, the researchers noted.

“Due to the observational nature of this study, we cannot rule out that the observed risk increase for ADHD is at least in part explained by the mother’s health condition that triggered the prescription of valproate during pregnancy,” they said. Other limitations included a lack of data on the exact amounts of valproate taken during pregnancy and the potential impact of nonepilepsy medications, they noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large size and population-based cohort, and support warnings by professional medical organizations against valproate use in pregnancy, the researchers said. “As randomized clinical trials of valproate use during pregnancy are neither feasible nor ethical, our study provides clinical information on the risk of ADHD associated with valproate use during pregnancy,” they concluded.

The study was supported by grants to various authors from the Danish Epilepsy Association Central Denmark Region, the Aarhus University Research Foundation, the Lundbeck Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the Novo Nordisk Foundation, and the European Commission.

SOURCE: Christensen J et al. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(1):e186606. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6606.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The children whose mothers used valproate between 90 days before conception and birth had a 48% increased risk of ADHD compared with children whose mothers did not use valproate.

Study details: The data come from a population-based cohort study of 913,302 children in Denmark.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants to various authors from the Danish Epilepsy Association Central Denmark Region, the Aarhus University Research Foundation, the Lundbeck Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the Novo Nordisk Foundation, and the European Commission.

Source: SOURCE: Christensen J et al. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(1):e186606. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6606.

How Often Are Staring Spells Seizures?

Investigators review cases at a new-onset seizure clinic.

CHICAGO—About half of staring spells referred to a new-onset seizure (NOS) clinic turn out to be epileptic seizures, according to a retrospective chart review presented at the 47th Annual Meeting of the Child Neurology Society.

Children with nonepileptic staring were younger and more likely to have developmental delay, compared with children with epileptic staring, said Seunghyo Kim, MD, Visiting Associate Professor of Pediatrics at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, and his colleagues

A Common Reason for Referral

Staring spells are common in children and a frequent reason for referral to NOS clinics, the investigators said. Staring spells may be generalized absence seizures, focal seizures, or nonepileptic events. Few studies, however, have examined patients who newly present to a neurology clinic with the chief complaint of staring spells.

To evaluate the clinical and demographic features of children who present with staring spells to a regional NOS clinic, the researchers reviewed charts from 2,818 patients who visited a children’s hospital between September 22, 2015, and March 19, 2018. The investigators identified 189 patients with staring spells.

They excluded 48 cases where staring was accompanied by or followed by generalized tonic-clonic seizures or other motor seizures. In addition, they excluded 16 cases of established epilepsy and four cases of provoked seizures, including febrile seizures.

The final study population included 121 cases. About 48% of these patients with staring spells were African American, and 38% were white. Patients’ mean age at first visit to the NOS clinic was 6, and mean age at staring spell onset was 5.2.

Fifty-nine patients (49%) had epileptic staring episodes, and 62 patients (51%) had nonepileptic events.

Continue to: Approximately 50% were referred by an emergency department...

Approximately 50% were referred by an emergency department, 48% by a primary care physician, and 2% by an urgent care clinic. Of the 62 cases that turned out to be nonepileptic events, about 61% were referred by primary care physicians.

MRI Findings in Patients With Focal Seizures

On average, patients with nonepileptic staring were younger at the initial clinic presentation and at staring spell onset. Patients with nonepileptic staring had an average age of 4.8 at their initial visit, whereas patients with focal seizures had an average age of 6.3. Patients with absence seizures had an average age of 8.3.

Patients with nonepileptic events were more likely to have developmental delay (approximately 35%) versus patients with focal seizures (23%) or absence seizures (8%).

Absence epilepsy was diagnosed in 24 patients (20%), and focal epilepsy in 35 patients (29%).

Of the 59 cases of epileptic staring, 46% (n = 27) were classified as syndromic; 36% (n = 21) had childhood absence epilepsy, and 5% (n = 3) had juvenile absence epilepsy. In addition, there was one case each of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis, Panayiotopoulos syndrome, and generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures.

About one-third of patients received MRI, and seven patients had etiologically relevant findings (eg, brain tumor, malformation of cortical development, and periventricular leukomalacia). All of the patients with abnormal MRIs had focal seizures.

“An NOS clinic ... can provide rapid, accurate diagnoses for staring spells,” said Dr. Kim. “This is important, as children with nonepileptic events should not be given the diagnosis of epilepsy, and their events should not be treated with seizure medications. Similarly, children who have epileptic seizures require accurate diagnosis, as the treatment depends on the seizure type.”

Investigators review cases at a new-onset seizure clinic.

Investigators review cases at a new-onset seizure clinic.

CHICAGO—About half of staring spells referred to a new-onset seizure (NOS) clinic turn out to be epileptic seizures, according to a retrospective chart review presented at the 47th Annual Meeting of the Child Neurology Society.

Children with nonepileptic staring were younger and more likely to have developmental delay, compared with children with epileptic staring, said Seunghyo Kim, MD, Visiting Associate Professor of Pediatrics at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, and his colleagues

A Common Reason for Referral

Staring spells are common in children and a frequent reason for referral to NOS clinics, the investigators said. Staring spells may be generalized absence seizures, focal seizures, or nonepileptic events. Few studies, however, have examined patients who newly present to a neurology clinic with the chief complaint of staring spells.

To evaluate the clinical and demographic features of children who present with staring spells to a regional NOS clinic, the researchers reviewed charts from 2,818 patients who visited a children’s hospital between September 22, 2015, and March 19, 2018. The investigators identified 189 patients with staring spells.

They excluded 48 cases where staring was accompanied by or followed by generalized tonic-clonic seizures or other motor seizures. In addition, they excluded 16 cases of established epilepsy and four cases of provoked seizures, including febrile seizures.

The final study population included 121 cases. About 48% of these patients with staring spells were African American, and 38% were white. Patients’ mean age at first visit to the NOS clinic was 6, and mean age at staring spell onset was 5.2.

Fifty-nine patients (49%) had epileptic staring episodes, and 62 patients (51%) had nonepileptic events.

Continue to: Approximately 50% were referred by an emergency department...

Approximately 50% were referred by an emergency department, 48% by a primary care physician, and 2% by an urgent care clinic. Of the 62 cases that turned out to be nonepileptic events, about 61% were referred by primary care physicians.

MRI Findings in Patients With Focal Seizures

On average, patients with nonepileptic staring were younger at the initial clinic presentation and at staring spell onset. Patients with nonepileptic staring had an average age of 4.8 at their initial visit, whereas patients with focal seizures had an average age of 6.3. Patients with absence seizures had an average age of 8.3.

Patients with nonepileptic events were more likely to have developmental delay (approximately 35%) versus patients with focal seizures (23%) or absence seizures (8%).

Absence epilepsy was diagnosed in 24 patients (20%), and focal epilepsy in 35 patients (29%).

Of the 59 cases of epileptic staring, 46% (n = 27) were classified as syndromic; 36% (n = 21) had childhood absence epilepsy, and 5% (n = 3) had juvenile absence epilepsy. In addition, there was one case each of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis, Panayiotopoulos syndrome, and generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures.

About one-third of patients received MRI, and seven patients had etiologically relevant findings (eg, brain tumor, malformation of cortical development, and periventricular leukomalacia). All of the patients with abnormal MRIs had focal seizures.

“An NOS clinic ... can provide rapid, accurate diagnoses for staring spells,” said Dr. Kim. “This is important, as children with nonepileptic events should not be given the diagnosis of epilepsy, and their events should not be treated with seizure medications. Similarly, children who have epileptic seizures require accurate diagnosis, as the treatment depends on the seizure type.”

CHICAGO—About half of staring spells referred to a new-onset seizure (NOS) clinic turn out to be epileptic seizures, according to a retrospective chart review presented at the 47th Annual Meeting of the Child Neurology Society.

Children with nonepileptic staring were younger and more likely to have developmental delay, compared with children with epileptic staring, said Seunghyo Kim, MD, Visiting Associate Professor of Pediatrics at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, and his colleagues

A Common Reason for Referral

Staring spells are common in children and a frequent reason for referral to NOS clinics, the investigators said. Staring spells may be generalized absence seizures, focal seizures, or nonepileptic events. Few studies, however, have examined patients who newly present to a neurology clinic with the chief complaint of staring spells.

To evaluate the clinical and demographic features of children who present with staring spells to a regional NOS clinic, the researchers reviewed charts from 2,818 patients who visited a children’s hospital between September 22, 2015, and March 19, 2018. The investigators identified 189 patients with staring spells.

They excluded 48 cases where staring was accompanied by or followed by generalized tonic-clonic seizures or other motor seizures. In addition, they excluded 16 cases of established epilepsy and four cases of provoked seizures, including febrile seizures.

The final study population included 121 cases. About 48% of these patients with staring spells were African American, and 38% were white. Patients’ mean age at first visit to the NOS clinic was 6, and mean age at staring spell onset was 5.2.

Fifty-nine patients (49%) had epileptic staring episodes, and 62 patients (51%) had nonepileptic events.

Continue to: Approximately 50% were referred by an emergency department...

Approximately 50% were referred by an emergency department, 48% by a primary care physician, and 2% by an urgent care clinic. Of the 62 cases that turned out to be nonepileptic events, about 61% were referred by primary care physicians.

MRI Findings in Patients With Focal Seizures

On average, patients with nonepileptic staring were younger at the initial clinic presentation and at staring spell onset. Patients with nonepileptic staring had an average age of 4.8 at their initial visit, whereas patients with focal seizures had an average age of 6.3. Patients with absence seizures had an average age of 8.3.

Patients with nonepileptic events were more likely to have developmental delay (approximately 35%) versus patients with focal seizures (23%) or absence seizures (8%).

Absence epilepsy was diagnosed in 24 patients (20%), and focal epilepsy in 35 patients (29%).

Of the 59 cases of epileptic staring, 46% (n = 27) were classified as syndromic; 36% (n = 21) had childhood absence epilepsy, and 5% (n = 3) had juvenile absence epilepsy. In addition, there was one case each of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis, Panayiotopoulos syndrome, and generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures.

About one-third of patients received MRI, and seven patients had etiologically relevant findings (eg, brain tumor, malformation of cortical development, and periventricular leukomalacia). All of the patients with abnormal MRIs had focal seizures.

“An NOS clinic ... can provide rapid, accurate diagnoses for staring spells,” said Dr. Kim. “This is important, as children with nonepileptic events should not be given the diagnosis of epilepsy, and their events should not be treated with seizure medications. Similarly, children who have epileptic seizures require accurate diagnosis, as the treatment depends on the seizure type.”

Hippocampal abnormalities seen in epilepsy subtypes may be congenital

NEW ORLEANS – , although to a lesser extent, based on findings from two studies presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

While the studies suggest an imaging endophenotype associated with these disorders, it’s unclear if a larger degree of abnormality causes disease manifestation, or whether there are other predisposing actors at work.

“What our study tells us is that hippocampal abnormalities can occur in the absence of seizure,” Marian Galovic, MD, said in an interview. “It may be that, in some cases, hippocampal abnormalities could be the cause, rather than the consequence, of seizures.”

Dr. Galovic of University College London was on hand to discuss the work of his colleague, Lili Long, MD, PhD, of the Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Changsha, China. Visa issues prevented her from attending the meeting.

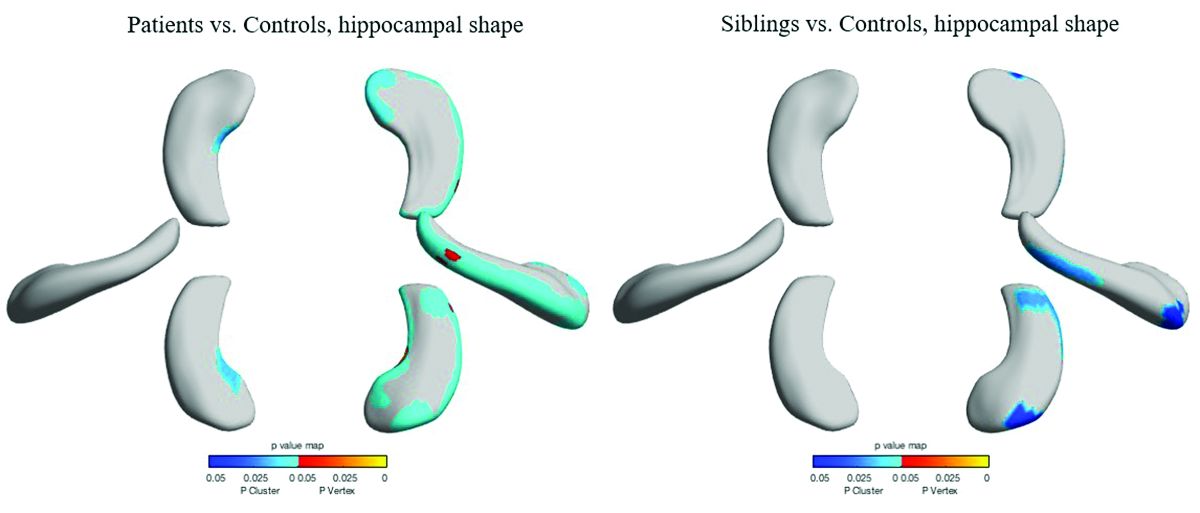

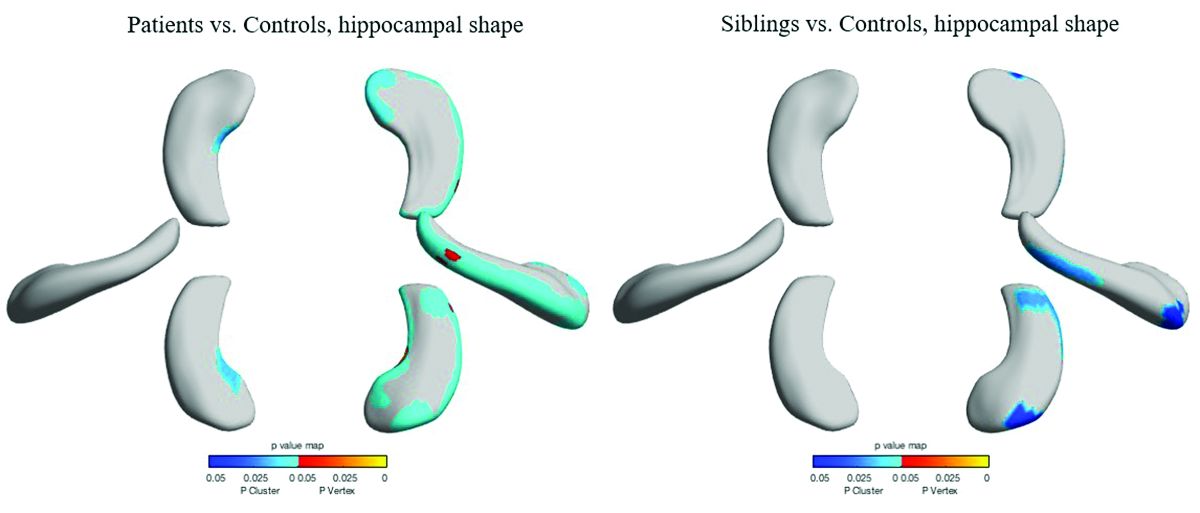

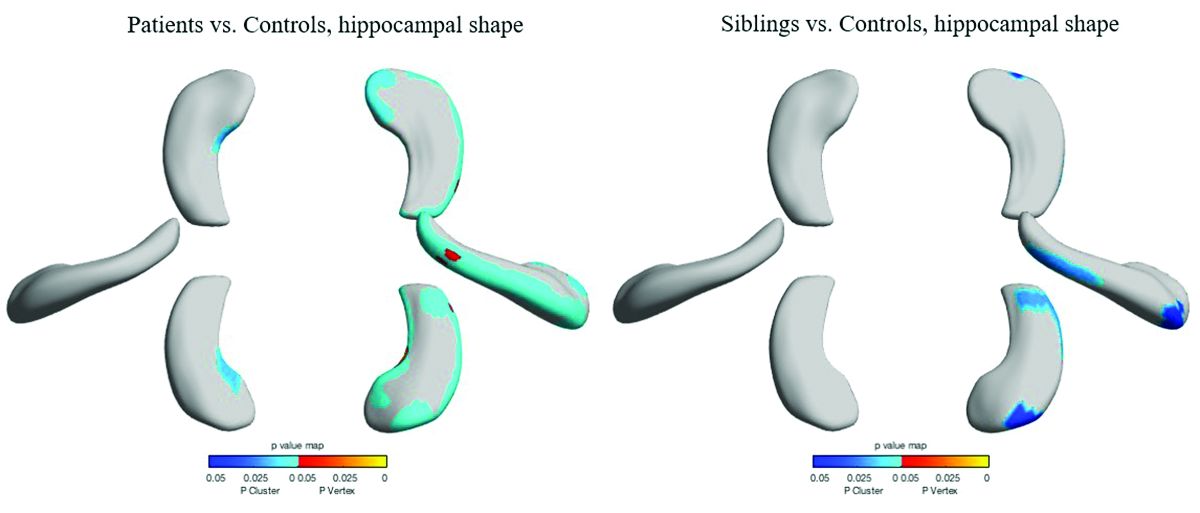

The study included 18 sibling pairs in which the affected siblings had sporadic, nonlesional temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), involving the right lobe in 12 and the left in 6. The patients, siblings, and 18 healthy, age-matched controls underwent clinical, electrophysiologic, and high-resolution structural neuroimaging.

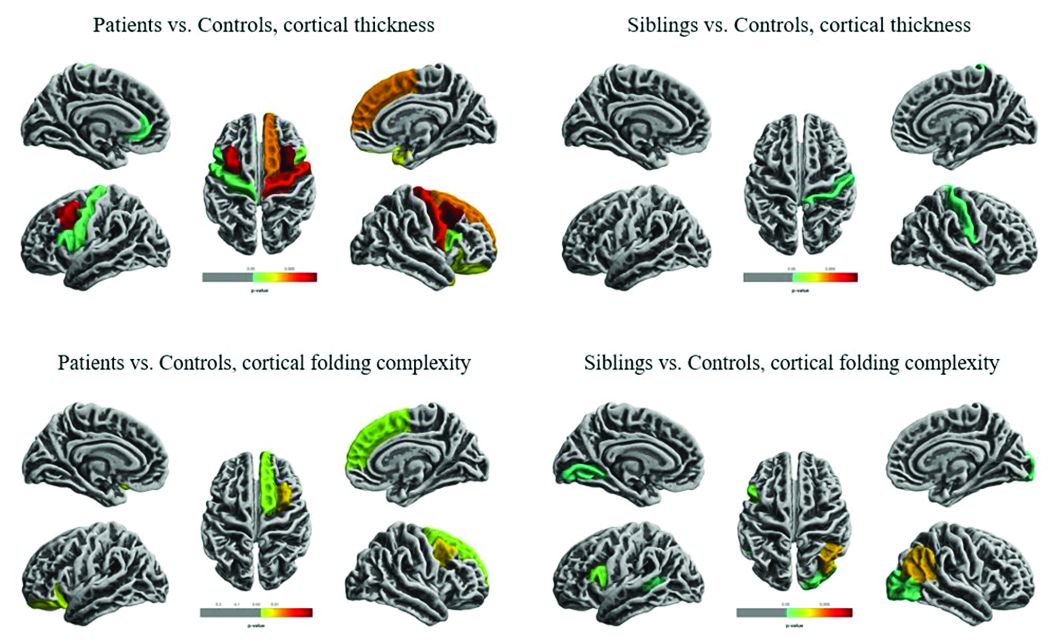

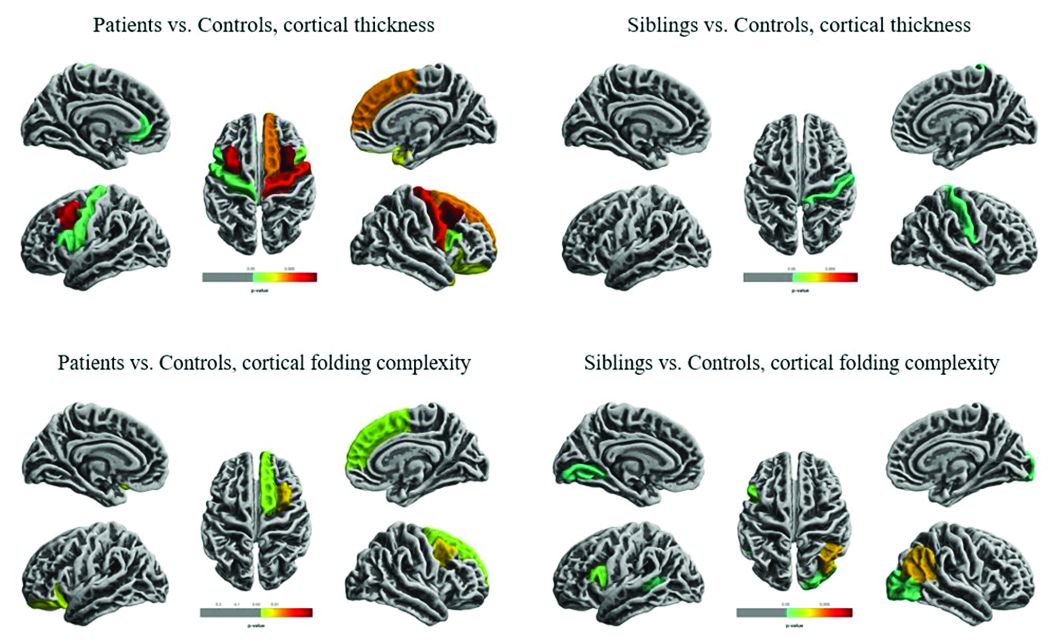

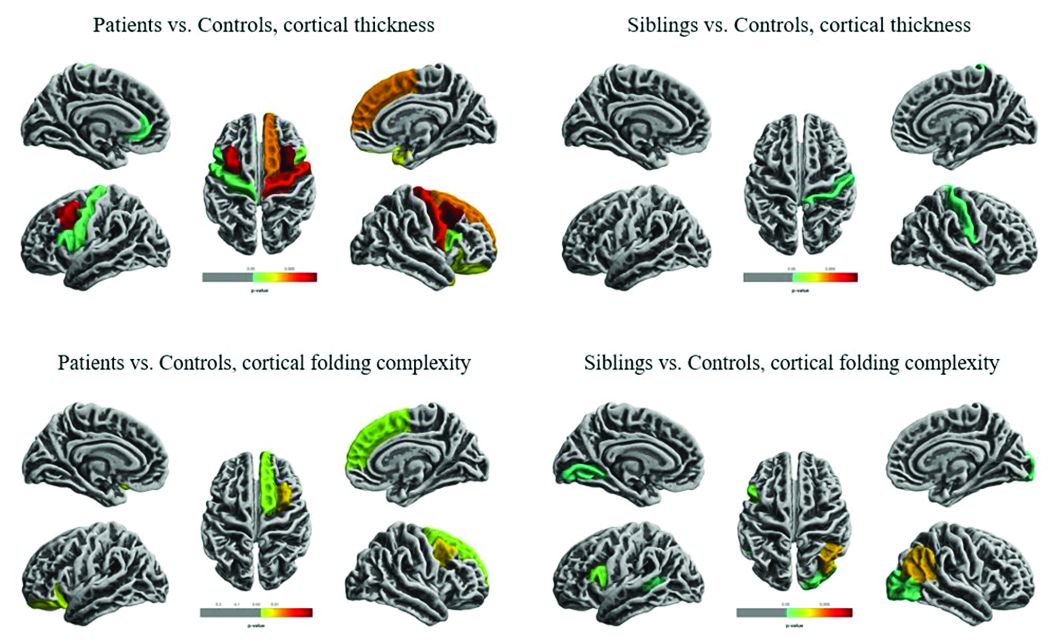

The researchers compared overall hippocampal volumes between groups and determined the subregional extent of hippocampal abnormalities using shape analysis. They also looked at whole-brain differences in cortical thickness and folding complexity.

As expected, median hippocampal volumes were largest in the healthy controls (left = 2.82 mL, right = 2.94 mL), and smallest in patients. Patients with left TLE had a median left hippocampal volume of 2.23 mL, while those with right TLE had a median right hippocampal volume of 1.92 mL.

However, volume in the unaffected siblings was a surprise. Like the patients, these subjects also had significant reductions in hippocampal volume when compared with controls (left = 2.47 mL, right = 2.65 mL). “The atrophy was relatively similar in siblings and patients, although not as pronounced in siblings,” Dr. Galovic said. “It was mostly unilateral in the siblings and bilateral in the patients, but it was still more pronounced on the side where the epilepsy of the affected sibling was coming from.”

Patients and siblings also shared morphologic variations of the hippocampus, with atrophy more pronounced on the right than the left. The right lateral body and anterior head of the hippocampus were most affected, Dr. Galovic said, with reductions in the right cornu ammonis 1 subfield and subiculum.

Widespread cortical thinning was present in patients, including the pericentral, frontal, and temporal areas. Unaffected siblings also showed cortical thinning, but this was mostly restricted to the right postcentral gyrus. Patients and siblings also demonstrated increased cortical folding complexity, but in different areas: predominantly frontal in patients, but predominantly parieto-occipital in siblings. Both were significantly different than healthy control subjects.

The study didn’t examine any association with memory, which is often impaired in patients with TLE. However, Dr. Galovic said, “We have just submitted for publication a study in which we did find an association between focal hippocampal atrophy and memory performance.”

A different study by a team at University College London looked at hippocampal structure and function in patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) and their unaffected siblings. The imaging study, lead by Lorenzo Caciagli, MD, of the university comprised 37 patients with JME, 16 unaffected siblings, and 20 healthy controls. It employed multimodal MRI and neuropsychological measures to examine the form and function of the mesiotemporal lobe.

The subjects were matched for age, sex, handedness, and hemispheric dominance, which was assessed with language lateralization indices. This measures the number of active voxels on functional MRI, showing which hemisphere is dominant for language.

Both patients and their siblings showed reductions in left hippocampal volume on the order of 5%-8%, significantly smaller than the volumes seen in healthy controls. About half of patients and half of siblings also showed either unilateral or bilateral hippocampal malrotation. This was present in just 15% of controls, another significant difference. The structural differences weren’t associated with seizure control or age at disease onset, or with any impairments in verbal or visual memory. But when the investigators performed functional mapping, they found unusual patterns of hippocampal activation in both patients and siblings, pointing to a dysfunction of verbal encoding. In patients, there appeared to be distinct patterns of underactivation along the hippocampal long axis, regardless of whether malrotation was present. But among patients who had malrotation, the left posterior hippocampus showed more activation during visual memory.

The team concluded that the hippocampal abnormalities in volume, shape, and positioning in patients with JME and their siblings are related to functional reorganization. The abnormalities probably occur during prenatal neurodevelopment, they noted.

“Cosegregation of imaging patterns in patients and their siblings is suggestive of genetic imaging phenotypes, and independent of disease activity,” Dr. Caciagli and his coinvestigators wrote in their abstract.

Funding for the TLE study came from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Ministry of Science and Technology of China, and Xiangya Hospital. Funding for the JME study came from a variety of U.K. charities and government agencies.

SOURCES: Long L et al. AES 2018, Abstract 2.183; Caciagli L et al. AES 2018, Abstract 2.166.

NEW ORLEANS – , although to a lesser extent, based on findings from two studies presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

While the studies suggest an imaging endophenotype associated with these disorders, it’s unclear if a larger degree of abnormality causes disease manifestation, or whether there are other predisposing actors at work.

“What our study tells us is that hippocampal abnormalities can occur in the absence of seizure,” Marian Galovic, MD, said in an interview. “It may be that, in some cases, hippocampal abnormalities could be the cause, rather than the consequence, of seizures.”

Dr. Galovic of University College London was on hand to discuss the work of his colleague, Lili Long, MD, PhD, of the Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Changsha, China. Visa issues prevented her from attending the meeting.

The study included 18 sibling pairs in which the affected siblings had sporadic, nonlesional temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), involving the right lobe in 12 and the left in 6. The patients, siblings, and 18 healthy, age-matched controls underwent clinical, electrophysiologic, and high-resolution structural neuroimaging.

The researchers compared overall hippocampal volumes between groups and determined the subregional extent of hippocampal abnormalities using shape analysis. They also looked at whole-brain differences in cortical thickness and folding complexity.

As expected, median hippocampal volumes were largest in the healthy controls (left = 2.82 mL, right = 2.94 mL), and smallest in patients. Patients with left TLE had a median left hippocampal volume of 2.23 mL, while those with right TLE had a median right hippocampal volume of 1.92 mL.

However, volume in the unaffected siblings was a surprise. Like the patients, these subjects also had significant reductions in hippocampal volume when compared with controls (left = 2.47 mL, right = 2.65 mL). “The atrophy was relatively similar in siblings and patients, although not as pronounced in siblings,” Dr. Galovic said. “It was mostly unilateral in the siblings and bilateral in the patients, but it was still more pronounced on the side where the epilepsy of the affected sibling was coming from.”

Patients and siblings also shared morphologic variations of the hippocampus, with atrophy more pronounced on the right than the left. The right lateral body and anterior head of the hippocampus were most affected, Dr. Galovic said, with reductions in the right cornu ammonis 1 subfield and subiculum.

Widespread cortical thinning was present in patients, including the pericentral, frontal, and temporal areas. Unaffected siblings also showed cortical thinning, but this was mostly restricted to the right postcentral gyrus. Patients and siblings also demonstrated increased cortical folding complexity, but in different areas: predominantly frontal in patients, but predominantly parieto-occipital in siblings. Both were significantly different than healthy control subjects.

The study didn’t examine any association with memory, which is often impaired in patients with TLE. However, Dr. Galovic said, “We have just submitted for publication a study in which we did find an association between focal hippocampal atrophy and memory performance.”

A different study by a team at University College London looked at hippocampal structure and function in patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) and their unaffected siblings. The imaging study, lead by Lorenzo Caciagli, MD, of the university comprised 37 patients with JME, 16 unaffected siblings, and 20 healthy controls. It employed multimodal MRI and neuropsychological measures to examine the form and function of the mesiotemporal lobe.

The subjects were matched for age, sex, handedness, and hemispheric dominance, which was assessed with language lateralization indices. This measures the number of active voxels on functional MRI, showing which hemisphere is dominant for language.

Both patients and their siblings showed reductions in left hippocampal volume on the order of 5%-8%, significantly smaller than the volumes seen in healthy controls. About half of patients and half of siblings also showed either unilateral or bilateral hippocampal malrotation. This was present in just 15% of controls, another significant difference. The structural differences weren’t associated with seizure control or age at disease onset, or with any impairments in verbal or visual memory. But when the investigators performed functional mapping, they found unusual patterns of hippocampal activation in both patients and siblings, pointing to a dysfunction of verbal encoding. In patients, there appeared to be distinct patterns of underactivation along the hippocampal long axis, regardless of whether malrotation was present. But among patients who had malrotation, the left posterior hippocampus showed more activation during visual memory.

The team concluded that the hippocampal abnormalities in volume, shape, and positioning in patients with JME and their siblings are related to functional reorganization. The abnormalities probably occur during prenatal neurodevelopment, they noted.

“Cosegregation of imaging patterns in patients and their siblings is suggestive of genetic imaging phenotypes, and independent of disease activity,” Dr. Caciagli and his coinvestigators wrote in their abstract.

Funding for the TLE study came from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Ministry of Science and Technology of China, and Xiangya Hospital. Funding for the JME study came from a variety of U.K. charities and government agencies.

SOURCES: Long L et al. AES 2018, Abstract 2.183; Caciagli L et al. AES 2018, Abstract 2.166.

NEW ORLEANS – , although to a lesser extent, based on findings from two studies presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

While the studies suggest an imaging endophenotype associated with these disorders, it’s unclear if a larger degree of abnormality causes disease manifestation, or whether there are other predisposing actors at work.

“What our study tells us is that hippocampal abnormalities can occur in the absence of seizure,” Marian Galovic, MD, said in an interview. “It may be that, in some cases, hippocampal abnormalities could be the cause, rather than the consequence, of seizures.”

Dr. Galovic of University College London was on hand to discuss the work of his colleague, Lili Long, MD, PhD, of the Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Changsha, China. Visa issues prevented her from attending the meeting.

The study included 18 sibling pairs in which the affected siblings had sporadic, nonlesional temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), involving the right lobe in 12 and the left in 6. The patients, siblings, and 18 healthy, age-matched controls underwent clinical, electrophysiologic, and high-resolution structural neuroimaging.

The researchers compared overall hippocampal volumes between groups and determined the subregional extent of hippocampal abnormalities using shape analysis. They also looked at whole-brain differences in cortical thickness and folding complexity.

As expected, median hippocampal volumes were largest in the healthy controls (left = 2.82 mL, right = 2.94 mL), and smallest in patients. Patients with left TLE had a median left hippocampal volume of 2.23 mL, while those with right TLE had a median right hippocampal volume of 1.92 mL.

However, volume in the unaffected siblings was a surprise. Like the patients, these subjects also had significant reductions in hippocampal volume when compared with controls (left = 2.47 mL, right = 2.65 mL). “The atrophy was relatively similar in siblings and patients, although not as pronounced in siblings,” Dr. Galovic said. “It was mostly unilateral in the siblings and bilateral in the patients, but it was still more pronounced on the side where the epilepsy of the affected sibling was coming from.”

Patients and siblings also shared morphologic variations of the hippocampus, with atrophy more pronounced on the right than the left. The right lateral body and anterior head of the hippocampus were most affected, Dr. Galovic said, with reductions in the right cornu ammonis 1 subfield and subiculum.

Widespread cortical thinning was present in patients, including the pericentral, frontal, and temporal areas. Unaffected siblings also showed cortical thinning, but this was mostly restricted to the right postcentral gyrus. Patients and siblings also demonstrated increased cortical folding complexity, but in different areas: predominantly frontal in patients, but predominantly parieto-occipital in siblings. Both were significantly different than healthy control subjects.

The study didn’t examine any association with memory, which is often impaired in patients with TLE. However, Dr. Galovic said, “We have just submitted for publication a study in which we did find an association between focal hippocampal atrophy and memory performance.”

A different study by a team at University College London looked at hippocampal structure and function in patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) and their unaffected siblings. The imaging study, lead by Lorenzo Caciagli, MD, of the university comprised 37 patients with JME, 16 unaffected siblings, and 20 healthy controls. It employed multimodal MRI and neuropsychological measures to examine the form and function of the mesiotemporal lobe.

The subjects were matched for age, sex, handedness, and hemispheric dominance, which was assessed with language lateralization indices. This measures the number of active voxels on functional MRI, showing which hemisphere is dominant for language.

Both patients and their siblings showed reductions in left hippocampal volume on the order of 5%-8%, significantly smaller than the volumes seen in healthy controls. About half of patients and half of siblings also showed either unilateral or bilateral hippocampal malrotation. This was present in just 15% of controls, another significant difference. The structural differences weren’t associated with seizure control or age at disease onset, or with any impairments in verbal or visual memory. But when the investigators performed functional mapping, they found unusual patterns of hippocampal activation in both patients and siblings, pointing to a dysfunction of verbal encoding. In patients, there appeared to be distinct patterns of underactivation along the hippocampal long axis, regardless of whether malrotation was present. But among patients who had malrotation, the left posterior hippocampus showed more activation during visual memory.

The team concluded that the hippocampal abnormalities in volume, shape, and positioning in patients with JME and their siblings are related to functional reorganization. The abnormalities probably occur during prenatal neurodevelopment, they noted.

“Cosegregation of imaging patterns in patients and their siblings is suggestive of genetic imaging phenotypes, and independent of disease activity,” Dr. Caciagli and his coinvestigators wrote in their abstract.

Funding for the TLE study came from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Ministry of Science and Technology of China, and Xiangya Hospital. Funding for the JME study came from a variety of U.K. charities and government agencies.

SOURCES: Long L et al. AES 2018, Abstract 2.183; Caciagli L et al. AES 2018, Abstract 2.166.

REPORTING FROM AES 2018

Measuring the Impact of Developmental Encephalopathic Epilepsy

Developmental encephalopathic epilepsies (DEEs) are responsible for a disproportionate number of cases of drug resistance, early deaths, and disability, according to researchers from Northwestern-Feinberg School of Medicine and Yale School of Medicine.

- An analysis of 613 pediatric patients from the Connecticut Study of Epilepsy allowed researchers to classify patients into specific epilepsy syndromes and to reclassify them over a period of 9 years.

- Among these children, 58 were found to have DEEs (9.4%).

- DEEs were more resistant to drug therapy than other epilepsies (71% vs 18%), more likely to cause intellectual disability (84% vs 11%), and more likely to cause death (21% vs <1%).

- The analysis also revealed changes from the initial epilepsy diagnosis over time, eg, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome was initially diagnosed in only 4 children but by the end of 9 years, 22 had received the diagnosis.

Berg AT, Levy SR, Testa FM. Evolution and course of early life developmental encephalopathic epilepsies: Focus on Lennox‐Gastaut syndrome. Epilepsia. 2018;59:2096-2105.

Developmental encephalopathic epilepsies (DEEs) are responsible for a disproportionate number of cases of drug resistance, early deaths, and disability, according to researchers from Northwestern-Feinberg School of Medicine and Yale School of Medicine.

- An analysis of 613 pediatric patients from the Connecticut Study of Epilepsy allowed researchers to classify patients into specific epilepsy syndromes and to reclassify them over a period of 9 years.

- Among these children, 58 were found to have DEEs (9.4%).

- DEEs were more resistant to drug therapy than other epilepsies (71% vs 18%), more likely to cause intellectual disability (84% vs 11%), and more likely to cause death (21% vs <1%).

- The analysis also revealed changes from the initial epilepsy diagnosis over time, eg, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome was initially diagnosed in only 4 children but by the end of 9 years, 22 had received the diagnosis.

Berg AT, Levy SR, Testa FM. Evolution and course of early life developmental encephalopathic epilepsies: Focus on Lennox‐Gastaut syndrome. Epilepsia. 2018;59:2096-2105.

Developmental encephalopathic epilepsies (DEEs) are responsible for a disproportionate number of cases of drug resistance, early deaths, and disability, according to researchers from Northwestern-Feinberg School of Medicine and Yale School of Medicine.

- An analysis of 613 pediatric patients from the Connecticut Study of Epilepsy allowed researchers to classify patients into specific epilepsy syndromes and to reclassify them over a period of 9 years.

- Among these children, 58 were found to have DEEs (9.4%).

- DEEs were more resistant to drug therapy than other epilepsies (71% vs 18%), more likely to cause intellectual disability (84% vs 11%), and more likely to cause death (21% vs <1%).

- The analysis also revealed changes from the initial epilepsy diagnosis over time, eg, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome was initially diagnosed in only 4 children but by the end of 9 years, 22 had received the diagnosis.

Berg AT, Levy SR, Testa FM. Evolution and course of early life developmental encephalopathic epilepsies: Focus on Lennox‐Gastaut syndrome. Epilepsia. 2018;59:2096-2105.

Infraslow Envelope Analysis Holds Promise in Predicting Seizures

Analyzing infraslow amplitude modulations may help clinicians better understand changes in intracranial EEG readings over the long-term and help researchers develop better algorithms to forecast the onset of seizures, according to a report published in Epilepsia.

- Investigators from Yale-New Haven Hospital collected intracranial EEG readings from 13 adult patients with medically refractory epilepsy.

- To derive infraslow envelope correlations, they estimated magnitude-squared coherence at <0.15 Hz of EEG frequency band power time series for all electrode contact pairs.

- Infraslow envelope magnitude-squared coherence increased significantly after patients had their antiepileptic drugs tapered; it also increased at night and decreased during the day.

Joshi RB, Duckrow RB, Goncharova II, et al. Seizure susceptibility and infraslow modulatory activity in the intracranial electroencephalogram. Epilepsia. 2018;59:2075-2085.

Analyzing infraslow amplitude modulations may help clinicians better understand changes in intracranial EEG readings over the long-term and help researchers develop better algorithms to forecast the onset of seizures, according to a report published in Epilepsia.

- Investigators from Yale-New Haven Hospital collected intracranial EEG readings from 13 adult patients with medically refractory epilepsy.

- To derive infraslow envelope correlations, they estimated magnitude-squared coherence at <0.15 Hz of EEG frequency band power time series for all electrode contact pairs.

- Infraslow envelope magnitude-squared coherence increased significantly after patients had their antiepileptic drugs tapered; it also increased at night and decreased during the day.

Joshi RB, Duckrow RB, Goncharova II, et al. Seizure susceptibility and infraslow modulatory activity in the intracranial electroencephalogram. Epilepsia. 2018;59:2075-2085.

Analyzing infraslow amplitude modulations may help clinicians better understand changes in intracranial EEG readings over the long-term and help researchers develop better algorithms to forecast the onset of seizures, according to a report published in Epilepsia.

- Investigators from Yale-New Haven Hospital collected intracranial EEG readings from 13 adult patients with medically refractory epilepsy.

- To derive infraslow envelope correlations, they estimated magnitude-squared coherence at <0.15 Hz of EEG frequency band power time series for all electrode contact pairs.

- Infraslow envelope magnitude-squared coherence increased significantly after patients had their antiepileptic drugs tapered; it also increased at night and decreased during the day.

Joshi RB, Duckrow RB, Goncharova II, et al. Seizure susceptibility and infraslow modulatory activity in the intracranial electroencephalogram. Epilepsia. 2018;59:2075-2085.

Provocative Induction of PNES Doesn’t Require Placebos

Diagnosing psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) can prove challenging; using provocative induction is one way to detect the disorder. A recent experiment suggests that inducing seizures without the use of a placebo is just as effective as inducing them with one.

- Researchers compared 170 patients suspected of having PNES who underwent provocative induction plus placebo to 170 patients who underwent the same induction procedure without a saline solution placebo.

- Induction triggered a seizure in 79.4% of patients without the help of the placebo, compared to 73.5% with placebo, a non-significant difference.

- Investigators postulated that the greater success rate in the non-placebo group may have resulted from the greater cumulative induction experience of clinicians, which may have influenced the manner and presentation of how the induction was presented.

- The study concluded that experienced clinicians should opt for non-placebo based provocative induction.

Chen DK, Dave H, Gadelmola, K et al. Provocative induction of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: Noninferiority of an induction technique without versus with placebo. Epilepsia. 2018; 59:e161-e165.

Diagnosing psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) can prove challenging; using provocative induction is one way to detect the disorder. A recent experiment suggests that inducing seizures without the use of a placebo is just as effective as inducing them with one.

- Researchers compared 170 patients suspected of having PNES who underwent provocative induction plus placebo to 170 patients who underwent the same induction procedure without a saline solution placebo.

- Induction triggered a seizure in 79.4% of patients without the help of the placebo, compared to 73.5% with placebo, a non-significant difference.

- Investigators postulated that the greater success rate in the non-placebo group may have resulted from the greater cumulative induction experience of clinicians, which may have influenced the manner and presentation of how the induction was presented.

- The study concluded that experienced clinicians should opt for non-placebo based provocative induction.

Chen DK, Dave H, Gadelmola, K et al. Provocative induction of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: Noninferiority of an induction technique without versus with placebo. Epilepsia. 2018; 59:e161-e165.

Diagnosing psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) can prove challenging; using provocative induction is one way to detect the disorder. A recent experiment suggests that inducing seizures without the use of a placebo is just as effective as inducing them with one.

- Researchers compared 170 patients suspected of having PNES who underwent provocative induction plus placebo to 170 patients who underwent the same induction procedure without a saline solution placebo.

- Induction triggered a seizure in 79.4% of patients without the help of the placebo, compared to 73.5% with placebo, a non-significant difference.

- Investigators postulated that the greater success rate in the non-placebo group may have resulted from the greater cumulative induction experience of clinicians, which may have influenced the manner and presentation of how the induction was presented.

- The study concluded that experienced clinicians should opt for non-placebo based provocative induction.

Chen DK, Dave H, Gadelmola, K et al. Provocative induction of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: Noninferiority of an induction technique without versus with placebo. Epilepsia. 2018; 59:e161-e165.

How does CBD compare and interact with other AEDs?

according to a review published in Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. “Careful down-titration of benzodiazepines is essential to minimize sedation with adjunctive CBD,” the authors said.

Although CBD’s antiepileptic mechanisms “are not fully elucidated, it is clear that administration of CBD as adjunct therapy decreases seizure frequency in patients with Dravet syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome,” wrote Shayma Ali, a doctoral student in the department of pediatrics and child health at the University of Otago in Wellington, New Zealand, and her colleagues. “Contrary to public expectation of miraculous results, CBD has a similar antiepileptic and side effect profile to other AEDs. Nevertheless, as individual children with these developmental and epileptic encephalopathies are often refractory to available AEDs, the addition of another potentially effective therapeutic medicine will be warmly welcomed by families and physicians.”

The FDA approved Epidiolex, a pharmaceutical-grade oral solution that is 98% CBD, in June of 2018. In September of 2018, the Drug Enforcement Administration classified it as a Schedule V controlled substance. Patients’ use of nonpharmaceutical grade CBD products, including those combined with tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), “raises concerns about the use of products with THC on the developing brain,” the review authors said.

Randomized trials

Three randomized, controlled, double-blind trials in patients with Dravet syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome found that CBD, compared with placebo, results in greater median seizure reductions (38%-41% vs. 13%-19%) and responder rates (i.e., the proportion of patients with 50% reductions in convulsive or drop seizures; 39%-46% vs. 14%-27%).

Common adverse effects include somnolence, diarrhea, decreased appetite, fatigue, lethargy, pyrexia, and vomiting. Hepatic transaminases became elevated in some patients, and this result occurred more often in patients taking valproate.

No phase 2 or phase 3 trials have assessed the efficacy of CBD without coadministration of other AEDs, and CBD’s efficacy may relate to its impact on the pharmacokinetics of coadministered AEDs. “The most important clinical interaction is between CBD and clobazam, as [the dose of] clobazam often needs to be lowered because of excessive sedation,” wrote Ms. Ali and her colleagues. CBD inhibits CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 – enzymes that are involved in clobazam metabolism – which results in high plasma concentrations of clobazam’s active metabolite, norclobazam. Plasma levels of topiramate, rufinamide, zonisamide, and eslicarbazepine also may increase when these drugs are taken with CBD.

Challenges and opportunities

Of the hundreds of compounds in the marijuana plant, CBD “has the most evidence of antiepileptic efficacy and does not have the psychoactive effects” of THC, the authors said. Little evidence supports the combination of THC and CBD for the treatment of epilepsy. In addition, research indicates that THC can have a proconvulsive effect in animal models and harm the development of the human brain.

Investigators are evaluating alternative routes of CBD delivery to avoid first-pass metabolism, such as oromucosal sprays, transdermal gels, eye drops, intranasal sprays, and rectal suppositories. “Alternative methods of administration ... deserve consideration, particularly for the developmental and epileptic encephalopathies population, as administration of oral medication can be challenging,” they said.

SOURCE: Ali S et al. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14087.

according to a review published in Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. “Careful down-titration of benzodiazepines is essential to minimize sedation with adjunctive CBD,” the authors said.

Although CBD’s antiepileptic mechanisms “are not fully elucidated, it is clear that administration of CBD as adjunct therapy decreases seizure frequency in patients with Dravet syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome,” wrote Shayma Ali, a doctoral student in the department of pediatrics and child health at the University of Otago in Wellington, New Zealand, and her colleagues. “Contrary to public expectation of miraculous results, CBD has a similar antiepileptic and side effect profile to other AEDs. Nevertheless, as individual children with these developmental and epileptic encephalopathies are often refractory to available AEDs, the addition of another potentially effective therapeutic medicine will be warmly welcomed by families and physicians.”

The FDA approved Epidiolex, a pharmaceutical-grade oral solution that is 98% CBD, in June of 2018. In September of 2018, the Drug Enforcement Administration classified it as a Schedule V controlled substance. Patients’ use of nonpharmaceutical grade CBD products, including those combined with tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), “raises concerns about the use of products with THC on the developing brain,” the review authors said.

Randomized trials

Three randomized, controlled, double-blind trials in patients with Dravet syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome found that CBD, compared with placebo, results in greater median seizure reductions (38%-41% vs. 13%-19%) and responder rates (i.e., the proportion of patients with 50% reductions in convulsive or drop seizures; 39%-46% vs. 14%-27%).

Common adverse effects include somnolence, diarrhea, decreased appetite, fatigue, lethargy, pyrexia, and vomiting. Hepatic transaminases became elevated in some patients, and this result occurred more often in patients taking valproate.

No phase 2 or phase 3 trials have assessed the efficacy of CBD without coadministration of other AEDs, and CBD’s efficacy may relate to its impact on the pharmacokinetics of coadministered AEDs. “The most important clinical interaction is between CBD and clobazam, as [the dose of] clobazam often needs to be lowered because of excessive sedation,” wrote Ms. Ali and her colleagues. CBD inhibits CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 – enzymes that are involved in clobazam metabolism – which results in high plasma concentrations of clobazam’s active metabolite, norclobazam. Plasma levels of topiramate, rufinamide, zonisamide, and eslicarbazepine also may increase when these drugs are taken with CBD.

Challenges and opportunities

Of the hundreds of compounds in the marijuana plant, CBD “has the most evidence of antiepileptic efficacy and does not have the psychoactive effects” of THC, the authors said. Little evidence supports the combination of THC and CBD for the treatment of epilepsy. In addition, research indicates that THC can have a proconvulsive effect in animal models and harm the development of the human brain.

Investigators are evaluating alternative routes of CBD delivery to avoid first-pass metabolism, such as oromucosal sprays, transdermal gels, eye drops, intranasal sprays, and rectal suppositories. “Alternative methods of administration ... deserve consideration, particularly for the developmental and epileptic encephalopathies population, as administration of oral medication can be challenging,” they said.

SOURCE: Ali S et al. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14087.

according to a review published in Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. “Careful down-titration of benzodiazepines is essential to minimize sedation with adjunctive CBD,” the authors said.

Although CBD’s antiepileptic mechanisms “are not fully elucidated, it is clear that administration of CBD as adjunct therapy decreases seizure frequency in patients with Dravet syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome,” wrote Shayma Ali, a doctoral student in the department of pediatrics and child health at the University of Otago in Wellington, New Zealand, and her colleagues. “Contrary to public expectation of miraculous results, CBD has a similar antiepileptic and side effect profile to other AEDs. Nevertheless, as individual children with these developmental and epileptic encephalopathies are often refractory to available AEDs, the addition of another potentially effective therapeutic medicine will be warmly welcomed by families and physicians.”

The FDA approved Epidiolex, a pharmaceutical-grade oral solution that is 98% CBD, in June of 2018. In September of 2018, the Drug Enforcement Administration classified it as a Schedule V controlled substance. Patients’ use of nonpharmaceutical grade CBD products, including those combined with tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), “raises concerns about the use of products with THC on the developing brain,” the review authors said.

Randomized trials

Three randomized, controlled, double-blind trials in patients with Dravet syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome found that CBD, compared with placebo, results in greater median seizure reductions (38%-41% vs. 13%-19%) and responder rates (i.e., the proportion of patients with 50% reductions in convulsive or drop seizures; 39%-46% vs. 14%-27%).

Common adverse effects include somnolence, diarrhea, decreased appetite, fatigue, lethargy, pyrexia, and vomiting. Hepatic transaminases became elevated in some patients, and this result occurred more often in patients taking valproate.

No phase 2 or phase 3 trials have assessed the efficacy of CBD without coadministration of other AEDs, and CBD’s efficacy may relate to its impact on the pharmacokinetics of coadministered AEDs. “The most important clinical interaction is between CBD and clobazam, as [the dose of] clobazam often needs to be lowered because of excessive sedation,” wrote Ms. Ali and her colleagues. CBD inhibits CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 – enzymes that are involved in clobazam metabolism – which results in high plasma concentrations of clobazam’s active metabolite, norclobazam. Plasma levels of topiramate, rufinamide, zonisamide, and eslicarbazepine also may increase when these drugs are taken with CBD.

Challenges and opportunities

Of the hundreds of compounds in the marijuana plant, CBD “has the most evidence of antiepileptic efficacy and does not have the psychoactive effects” of THC, the authors said. Little evidence supports the combination of THC and CBD for the treatment of epilepsy. In addition, research indicates that THC can have a proconvulsive effect in animal models and harm the development of the human brain.

Investigators are evaluating alternative routes of CBD delivery to avoid first-pass metabolism, such as oromucosal sprays, transdermal gels, eye drops, intranasal sprays, and rectal suppositories. “Alternative methods of administration ... deserve consideration, particularly for the developmental and epileptic encephalopathies population, as administration of oral medication can be challenging,” they said.

SOURCE: Ali S et al. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14087.

FROM DEVELOPMENTAL MEDICINE & CHILD NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point: Cannabidiol’s efficacy is similar to that of other antiepileptic drugs.

Major finding: Cannabidiol inhibits CYP2C19 and CYP3A4, which are involved in clobazam metabolism.

Study details: An invited review.

Disclosures: No disclosures were reported.

Source: Ali S et al. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14087.

How often is AED treatment delayed for patients with epilepsy?

NEW ORLEANS – , according to an Australian study presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. Most untreated patients begin an AED after experiencing subsequent seizures, however.

“The decision to start or withhold treatment reflects the complex interplay between factors perceived to influence the predicted risk of seizure recurrence, which remain imprecise, and personal factors,” said lead study author Zhibin Chen, PhD, a biostatistician at the University of Melbourne and colleagues.

Many patients with epilepsy in resource-poor countries may not receive AED therapy for socioeconomic reasons, but little is known about untreated epilepsy in high-income countries. To assess the extent of and reasons for patients not receiving AEDs when treatment is accessible and affordable, Dr. Chen and colleagues prospectively recruited adult patients who attended the first-seizure clinics of publicly funded hospitals in Western Australia between May 1, 1999, and May 31, 2016. The patients had new-onset seizures and were referred by primary care or emergency department physicians. The health care system provided universal coverage for patients’ hospital admissions, outpatient visits, investigations, and treatment.

The researchers identified patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy and reviewed medical records to determine the proportion of untreated patients and the reasons for not starting treatment at each follow-up visit. The investigators compared the sociodemographic factors, neuroimaging, and EEG findings of treated and untreated patients.

In all, 1,317 people attended the clinics during the study period, and 610 patients (61% male; median age, 40) received a diagnosis of epilepsy and met 2014 International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) diagnostic criteria for epilepsy. Patients were followed for a median of 5.7 years.

Of the 610 patients with epilepsy, 31% did not start AED treatment at the time of diagnosis – 16.4% because the neurologist did not recommend treatment and 14.6% because the patient declined treatment despite a neurologist’s recommendation to start therapy.

Patients’ reasons for not starting treatment included doubts about the need for treatment or about the epilepsy diagnosis, as well as concerns about medication side effects. Neurologists’ reasons for not beginning treatment included a patient having only one seizure and awaiting further results. The presence of seizure-precipitating factors (e.g., flashing lights, sleep deprivation, stress, or alcohol use) was another reason that patients and neurologists commonly cited for not initiating treatment.

Among the 189 initially untreated patients, 62.4% started treatment after a median delay of 95 days, “mainly after further seizures,” the investigators said. Patients with epilepsy who were older, from lower socioeconomic areas, had experienced more seizures, or had epileptogenic lesions on neuroimaging were more likely to initiate AED treatment at diagnosis.

“The percentage of people who were not initially prescribed AEDs was much higher than expected and suggests that untreated epilepsy exists not just in resource-poor, but also in wealthy countries,” said Dr. Chen.

More research is needed to assess the long-term outcomes of patient with seizure-precipitating factors who initiate AEDs immediately, compared with those who try avoidance of precipitating factors alone, said Dr. Chen.

This study was supported by a grant from UCB Pharma.

SOURCE: Chen Z et al. AES 2018, Abstract 3.421.

NEW ORLEANS – , according to an Australian study presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. Most untreated patients begin an AED after experiencing subsequent seizures, however.

“The decision to start or withhold treatment reflects the complex interplay between factors perceived to influence the predicted risk of seizure recurrence, which remain imprecise, and personal factors,” said lead study author Zhibin Chen, PhD, a biostatistician at the University of Melbourne and colleagues.

Many patients with epilepsy in resource-poor countries may not receive AED therapy for socioeconomic reasons, but little is known about untreated epilepsy in high-income countries. To assess the extent of and reasons for patients not receiving AEDs when treatment is accessible and affordable, Dr. Chen and colleagues prospectively recruited adult patients who attended the first-seizure clinics of publicly funded hospitals in Western Australia between May 1, 1999, and May 31, 2016. The patients had new-onset seizures and were referred by primary care or emergency department physicians. The health care system provided universal coverage for patients’ hospital admissions, outpatient visits, investigations, and treatment.

The researchers identified patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy and reviewed medical records to determine the proportion of untreated patients and the reasons for not starting treatment at each follow-up visit. The investigators compared the sociodemographic factors, neuroimaging, and EEG findings of treated and untreated patients.

In all, 1,317 people attended the clinics during the study period, and 610 patients (61% male; median age, 40) received a diagnosis of epilepsy and met 2014 International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) diagnostic criteria for epilepsy. Patients were followed for a median of 5.7 years.

Of the 610 patients with epilepsy, 31% did not start AED treatment at the time of diagnosis – 16.4% because the neurologist did not recommend treatment and 14.6% because the patient declined treatment despite a neurologist’s recommendation to start therapy.

Patients’ reasons for not starting treatment included doubts about the need for treatment or about the epilepsy diagnosis, as well as concerns about medication side effects. Neurologists’ reasons for not beginning treatment included a patient having only one seizure and awaiting further results. The presence of seizure-precipitating factors (e.g., flashing lights, sleep deprivation, stress, or alcohol use) was another reason that patients and neurologists commonly cited for not initiating treatment.