User login

What are the cardiorenal differences between type 1 and type 2 diabetes?

While type 2 diabetes is associated with a greater risk for cardiovascular events than type 1 diabetes, the latter is more associated with chronic kidney complications, according to data from a French observational study.

That’s not to say that type 1 diabetes isn’t also associated with poor heart health that is of concern, according to Denis Angoulvant, MD, of Tours (France) Regional University Hospital and Trousseau Hospital in Paris.

“The difference is that, in the middle or older ages, we suddenly see a surge of cardiovascular events in type 1 diabetic patients,” he said at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. “As a cardiologist, I must say that we are barely see these patients ahead of those complications, so we advocate that there’s a gap to be filled here to prevent these events in these patients.”

Few studies have looked at the comparative risks for cardiovascular and renal outcomes between patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, Dr. Angoulvant said, so the aim of the study he presented was to look at this in more detail.

Comparing cardiovascular and renal outcomes

Data from the French hospital discharge database (PMSI), which covers more than 98% of the country’s population, were used to find all adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes who had at least 5 years of follow-up data starting from 2013.

Not surprisingly, there were eight times as many individuals with type 2 diabetes (425,207) than those with type 1 diabetes (50,623), and patients with type 2 diabetes tended to be older than those with type 1 diabetes (mean age, 68.6 vs. 61.4 years).

There were many significant differences between the two groups of patients in terms of clinical variables, such as patients with type 2 diabetes having more cardiovascular risk factors or preexisting heart problems, and those with type 1 diabetes more likely to have diabetic eye disease.

Indeed, Dr. Angoulvant pointed out that those with type 2 diabetes were significantly more likely (all P < .0001) than those with type 1 diabetes to have: hypertension (70.8% vs. 50.5%), heart failure (35.7% vs. 16.4%), valvular heart disease (7.2% vs. 3.5%), dilated cardiomyopathy (5.5% vs. 2.7%), coronary artery disease (27.6 vs. 18.6%), previous MI (3.0% vs. 2.4%), peripheral vascular disease (22.0% vs. 15.5%), and ischemic stroke (3.3 vs. 2.2%).

“Regarding more specific microvascular diabetic complications, we had a higher incidence of chronic kidney disease in type 2 diabetes patients [10.2% vs. 9.1%], but a higher incidence of diabetic retinopathy in type 1 diabetes patients [6.6% vs. 12.2%],” Dr. Angoulvant said.

Considering more than 2 million person-years of follow-up, the annual rates of MI, new-onset heart failure, ischemic stroke, and chronic kidney disease for the whole study population were respective 1.4%, 5.4%, 1.2%, and 3.4%. The annual rates for death from any cause was 9.7%, and for a cardiovascular reason was 2.4%.

Cardiovascular disease prevalence and event rates

The mean follow-up period was 4.3 years, and over this time the age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of cardiovascular disease was found to be highest in individuals with type 2 diabetes, especially after the age of 40 years.

Looking at the rates of different cardiovascular events showed that both younger (18-29 years) and older (60+ years) people with type 1 diabetes had a 1.2-fold higher risk for MI than similarly aged individuals with type 2 diabetes.

Furthermore, younger and older type 1 diabetes individuals had a 1.1- to 1.4-fold greater risk of new-onset heart failure than those with type 2 diabetes.

“Interestingly, regarding the incidence of ischemic stroke in our population, we found no significant difference between patients with type 1 diabetes, and patients with type 2 diabetes,” Dr. Angoulvant said.

Chronic kidney disease and risk for death

Chronic kidney disease was most common in individuals with type 1 diabetes who were aged between 18 and 69 years, with a greater prevalence also seen in those with type 2 diabetes only after age 80.

The risk of new chronic kidney disease was significantly increased in patients with type 1 diabetes, compared with patients with type 2 diabetes, with a 1.1- to 2.4-fold increase seen, first in individuals aged 18-49 years, and then again after the age of 60 years.

Dr. Angoulvant reported that the risk of dying from any cause was 1.1-fold higher in people with type 1 diabetes, compared with those with type 2 diabetes, but after the age of 60 years.

The risk of death from cardiovascular events was also increased in people with type 1 diabetes, but between the ages of 60 and 69 years.

Asked what his take-home message might be, Dr. Angoulvant stressed the importance of heart failure, in all patients with diabetes but particularly in those with type 1 diabetes.

“I think there is room for improvement in terms of assessing who is going to have heart failure, how to assess heart failure, and more importantly, how to prevent heart failure,” perhaps by “introducing those drugs that have shown tremendous benefit regarding hospitalization, such as [sodium-glucose transporter 2] inhibitors” in patients with type 1 diabetes ahead of the events, he said.

Dr. Angoulvant had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

While type 2 diabetes is associated with a greater risk for cardiovascular events than type 1 diabetes, the latter is more associated with chronic kidney complications, according to data from a French observational study.

That’s not to say that type 1 diabetes isn’t also associated with poor heart health that is of concern, according to Denis Angoulvant, MD, of Tours (France) Regional University Hospital and Trousseau Hospital in Paris.

“The difference is that, in the middle or older ages, we suddenly see a surge of cardiovascular events in type 1 diabetic patients,” he said at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. “As a cardiologist, I must say that we are barely see these patients ahead of those complications, so we advocate that there’s a gap to be filled here to prevent these events in these patients.”

Few studies have looked at the comparative risks for cardiovascular and renal outcomes between patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, Dr. Angoulvant said, so the aim of the study he presented was to look at this in more detail.

Comparing cardiovascular and renal outcomes

Data from the French hospital discharge database (PMSI), which covers more than 98% of the country’s population, were used to find all adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes who had at least 5 years of follow-up data starting from 2013.

Not surprisingly, there were eight times as many individuals with type 2 diabetes (425,207) than those with type 1 diabetes (50,623), and patients with type 2 diabetes tended to be older than those with type 1 diabetes (mean age, 68.6 vs. 61.4 years).

There were many significant differences between the two groups of patients in terms of clinical variables, such as patients with type 2 diabetes having more cardiovascular risk factors or preexisting heart problems, and those with type 1 diabetes more likely to have diabetic eye disease.

Indeed, Dr. Angoulvant pointed out that those with type 2 diabetes were significantly more likely (all P < .0001) than those with type 1 diabetes to have: hypertension (70.8% vs. 50.5%), heart failure (35.7% vs. 16.4%), valvular heart disease (7.2% vs. 3.5%), dilated cardiomyopathy (5.5% vs. 2.7%), coronary artery disease (27.6 vs. 18.6%), previous MI (3.0% vs. 2.4%), peripheral vascular disease (22.0% vs. 15.5%), and ischemic stroke (3.3 vs. 2.2%).

“Regarding more specific microvascular diabetic complications, we had a higher incidence of chronic kidney disease in type 2 diabetes patients [10.2% vs. 9.1%], but a higher incidence of diabetic retinopathy in type 1 diabetes patients [6.6% vs. 12.2%],” Dr. Angoulvant said.

Considering more than 2 million person-years of follow-up, the annual rates of MI, new-onset heart failure, ischemic stroke, and chronic kidney disease for the whole study population were respective 1.4%, 5.4%, 1.2%, and 3.4%. The annual rates for death from any cause was 9.7%, and for a cardiovascular reason was 2.4%.

Cardiovascular disease prevalence and event rates

The mean follow-up period was 4.3 years, and over this time the age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of cardiovascular disease was found to be highest in individuals with type 2 diabetes, especially after the age of 40 years.

Looking at the rates of different cardiovascular events showed that both younger (18-29 years) and older (60+ years) people with type 1 diabetes had a 1.2-fold higher risk for MI than similarly aged individuals with type 2 diabetes.

Furthermore, younger and older type 1 diabetes individuals had a 1.1- to 1.4-fold greater risk of new-onset heart failure than those with type 2 diabetes.

“Interestingly, regarding the incidence of ischemic stroke in our population, we found no significant difference between patients with type 1 diabetes, and patients with type 2 diabetes,” Dr. Angoulvant said.

Chronic kidney disease and risk for death

Chronic kidney disease was most common in individuals with type 1 diabetes who were aged between 18 and 69 years, with a greater prevalence also seen in those with type 2 diabetes only after age 80.

The risk of new chronic kidney disease was significantly increased in patients with type 1 diabetes, compared with patients with type 2 diabetes, with a 1.1- to 2.4-fold increase seen, first in individuals aged 18-49 years, and then again after the age of 60 years.

Dr. Angoulvant reported that the risk of dying from any cause was 1.1-fold higher in people with type 1 diabetes, compared with those with type 2 diabetes, but after the age of 60 years.

The risk of death from cardiovascular events was also increased in people with type 1 diabetes, but between the ages of 60 and 69 years.

Asked what his take-home message might be, Dr. Angoulvant stressed the importance of heart failure, in all patients with diabetes but particularly in those with type 1 diabetes.

“I think there is room for improvement in terms of assessing who is going to have heart failure, how to assess heart failure, and more importantly, how to prevent heart failure,” perhaps by “introducing those drugs that have shown tremendous benefit regarding hospitalization, such as [sodium-glucose transporter 2] inhibitors” in patients with type 1 diabetes ahead of the events, he said.

Dr. Angoulvant had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

While type 2 diabetes is associated with a greater risk for cardiovascular events than type 1 diabetes, the latter is more associated with chronic kidney complications, according to data from a French observational study.

That’s not to say that type 1 diabetes isn’t also associated with poor heart health that is of concern, according to Denis Angoulvant, MD, of Tours (France) Regional University Hospital and Trousseau Hospital in Paris.

“The difference is that, in the middle or older ages, we suddenly see a surge of cardiovascular events in type 1 diabetic patients,” he said at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. “As a cardiologist, I must say that we are barely see these patients ahead of those complications, so we advocate that there’s a gap to be filled here to prevent these events in these patients.”

Few studies have looked at the comparative risks for cardiovascular and renal outcomes between patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, Dr. Angoulvant said, so the aim of the study he presented was to look at this in more detail.

Comparing cardiovascular and renal outcomes

Data from the French hospital discharge database (PMSI), which covers more than 98% of the country’s population, were used to find all adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes who had at least 5 years of follow-up data starting from 2013.

Not surprisingly, there were eight times as many individuals with type 2 diabetes (425,207) than those with type 1 diabetes (50,623), and patients with type 2 diabetes tended to be older than those with type 1 diabetes (mean age, 68.6 vs. 61.4 years).

There were many significant differences between the two groups of patients in terms of clinical variables, such as patients with type 2 diabetes having more cardiovascular risk factors or preexisting heart problems, and those with type 1 diabetes more likely to have diabetic eye disease.

Indeed, Dr. Angoulvant pointed out that those with type 2 diabetes were significantly more likely (all P < .0001) than those with type 1 diabetes to have: hypertension (70.8% vs. 50.5%), heart failure (35.7% vs. 16.4%), valvular heart disease (7.2% vs. 3.5%), dilated cardiomyopathy (5.5% vs. 2.7%), coronary artery disease (27.6 vs. 18.6%), previous MI (3.0% vs. 2.4%), peripheral vascular disease (22.0% vs. 15.5%), and ischemic stroke (3.3 vs. 2.2%).

“Regarding more specific microvascular diabetic complications, we had a higher incidence of chronic kidney disease in type 2 diabetes patients [10.2% vs. 9.1%], but a higher incidence of diabetic retinopathy in type 1 diabetes patients [6.6% vs. 12.2%],” Dr. Angoulvant said.

Considering more than 2 million person-years of follow-up, the annual rates of MI, new-onset heart failure, ischemic stroke, and chronic kidney disease for the whole study population were respective 1.4%, 5.4%, 1.2%, and 3.4%. The annual rates for death from any cause was 9.7%, and for a cardiovascular reason was 2.4%.

Cardiovascular disease prevalence and event rates

The mean follow-up period was 4.3 years, and over this time the age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of cardiovascular disease was found to be highest in individuals with type 2 diabetes, especially after the age of 40 years.

Looking at the rates of different cardiovascular events showed that both younger (18-29 years) and older (60+ years) people with type 1 diabetes had a 1.2-fold higher risk for MI than similarly aged individuals with type 2 diabetes.

Furthermore, younger and older type 1 diabetes individuals had a 1.1- to 1.4-fold greater risk of new-onset heart failure than those with type 2 diabetes.

“Interestingly, regarding the incidence of ischemic stroke in our population, we found no significant difference between patients with type 1 diabetes, and patients with type 2 diabetes,” Dr. Angoulvant said.

Chronic kidney disease and risk for death

Chronic kidney disease was most common in individuals with type 1 diabetes who were aged between 18 and 69 years, with a greater prevalence also seen in those with type 2 diabetes only after age 80.

The risk of new chronic kidney disease was significantly increased in patients with type 1 diabetes, compared with patients with type 2 diabetes, with a 1.1- to 2.4-fold increase seen, first in individuals aged 18-49 years, and then again after the age of 60 years.

Dr. Angoulvant reported that the risk of dying from any cause was 1.1-fold higher in people with type 1 diabetes, compared with those with type 2 diabetes, but after the age of 60 years.

The risk of death from cardiovascular events was also increased in people with type 1 diabetes, but between the ages of 60 and 69 years.

Asked what his take-home message might be, Dr. Angoulvant stressed the importance of heart failure, in all patients with diabetes but particularly in those with type 1 diabetes.

“I think there is room for improvement in terms of assessing who is going to have heart failure, how to assess heart failure, and more importantly, how to prevent heart failure,” perhaps by “introducing those drugs that have shown tremendous benefit regarding hospitalization, such as [sodium-glucose transporter 2] inhibitors” in patients with type 1 diabetes ahead of the events, he said.

Dr. Angoulvant had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

FROM EASD 2021

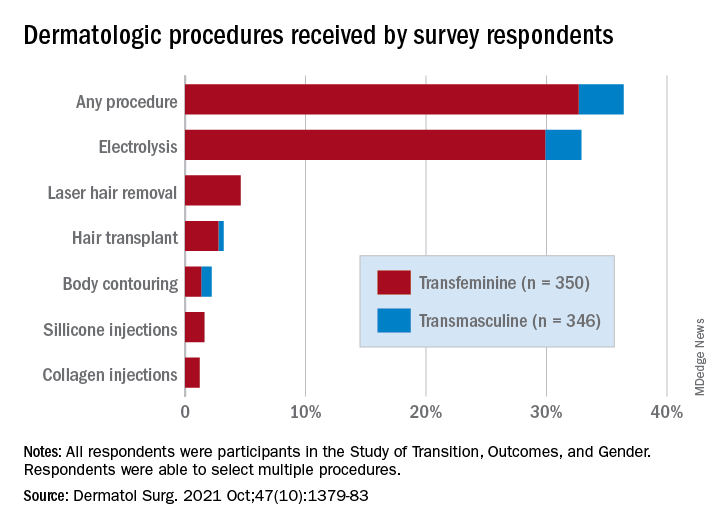

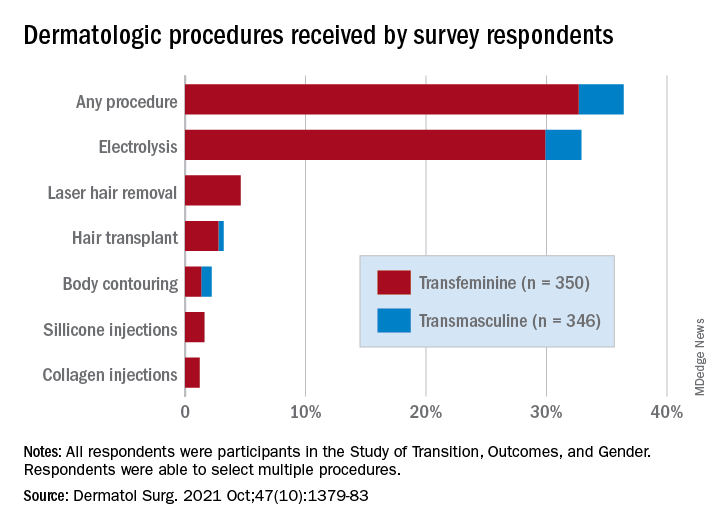

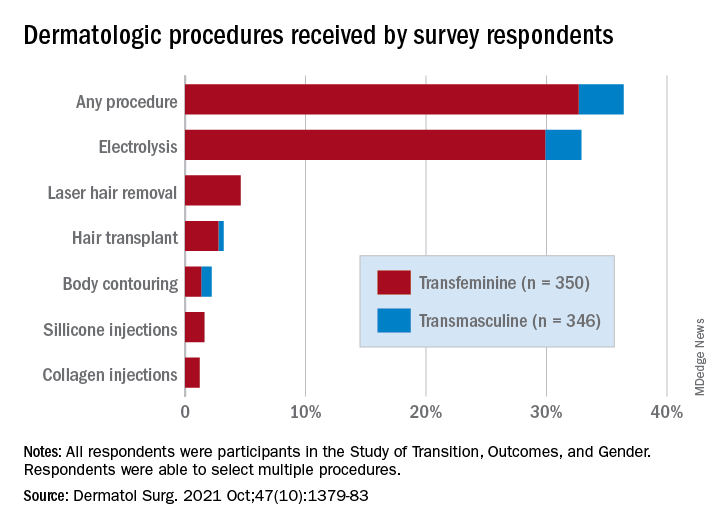

Transgender use of dermatologic procedures has strong gender tilt

, according to the results of a recent survey.

Transfeminine persons – those assigned male at birth – were much more likely to report a previous dermatologic procedure, compared with transmasculine respondents, by a margin of 64.9%-7.5%, Laura Ragmanauskaite, MD, and associates reported.

“Hair removal was the most frequently reported procedure type, with electrolysis being more common than laser hair removal,” they said, noting that “previous research on hair removal treatments among gender minority persons did not detect differences in the use of electrolysis and laser hair removal.”

Just under one-third of all respondents (32.9%) said that they had undergone electrolysis and 4.6% reported previous laser hair removal. For electrolysis, that works out to 59.4% of transfeminine and 6.1% of transmasculine respondents, while 9.1% of all transfeminine and no transmasculine persons had received laser hair removal, Dr. Ragmanauskaite of the department of dermatology, Emory University, Atlanta, and her coauthors said.

Those who had undergone gender-affirming surgery were significantly more likely to report electrolysis (78.6%) than were persons who had received no gender-affirming surgery or hormone therapy alone (47.4%), a statistically significant difference (P < .01). All of the other, less common procedures included in the online survey – 696 responses were received from 350 transfeminine and 346 transmasculine persons participating in the Study of Transition, Outcomes, and Gender – were reported more often by the transfeminine respondents. The procedure with the closest gender distribution was body contouring, reported by nine transfeminine and six transmasculine persons, the researchers said.

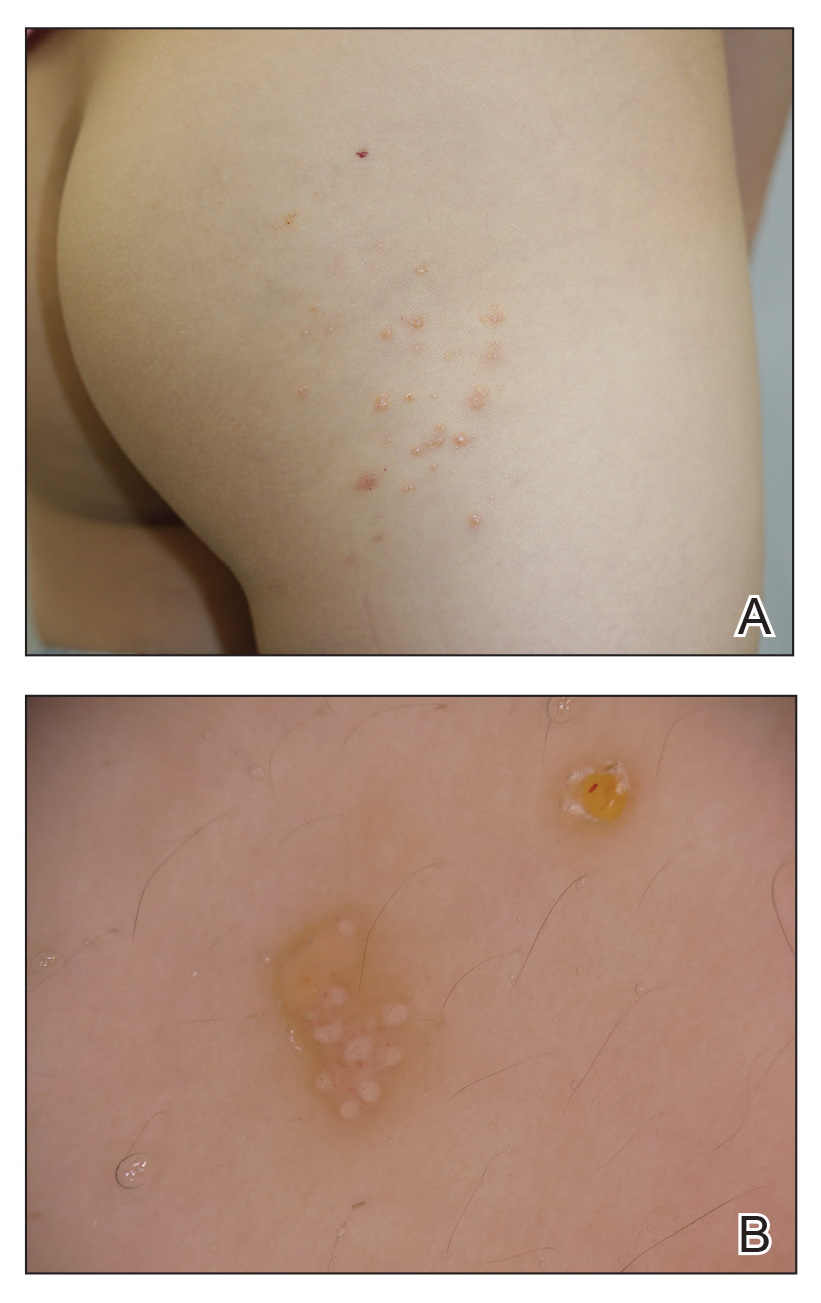

Use of dermal fillers was even less common (2.8% among all respondents, all transfeminine persons), with just 11 reporting having received silicone and 8 reporting having received collagen, although the survey did not ask about how the injections were obtained. In a previous study, the prevalence of illicit filler injection in transgender women was 16.9%, they pointed out.

These types of noninvasive, gender-affirming procedures “may contribute to higher levels of self-confidence and [reduce] gender dysphoria. Future studies should examine motivations, barriers, and optimal timing” for such procedures in transgender persons, Dr. Ragmanauskaite and associates wrote.

The authors reported that they had no relevant disclosures.

, according to the results of a recent survey.

Transfeminine persons – those assigned male at birth – were much more likely to report a previous dermatologic procedure, compared with transmasculine respondents, by a margin of 64.9%-7.5%, Laura Ragmanauskaite, MD, and associates reported.

“Hair removal was the most frequently reported procedure type, with electrolysis being more common than laser hair removal,” they said, noting that “previous research on hair removal treatments among gender minority persons did not detect differences in the use of electrolysis and laser hair removal.”

Just under one-third of all respondents (32.9%) said that they had undergone electrolysis and 4.6% reported previous laser hair removal. For electrolysis, that works out to 59.4% of transfeminine and 6.1% of transmasculine respondents, while 9.1% of all transfeminine and no transmasculine persons had received laser hair removal, Dr. Ragmanauskaite of the department of dermatology, Emory University, Atlanta, and her coauthors said.

Those who had undergone gender-affirming surgery were significantly more likely to report electrolysis (78.6%) than were persons who had received no gender-affirming surgery or hormone therapy alone (47.4%), a statistically significant difference (P < .01). All of the other, less common procedures included in the online survey – 696 responses were received from 350 transfeminine and 346 transmasculine persons participating in the Study of Transition, Outcomes, and Gender – were reported more often by the transfeminine respondents. The procedure with the closest gender distribution was body contouring, reported by nine transfeminine and six transmasculine persons, the researchers said.

Use of dermal fillers was even less common (2.8% among all respondents, all transfeminine persons), with just 11 reporting having received silicone and 8 reporting having received collagen, although the survey did not ask about how the injections were obtained. In a previous study, the prevalence of illicit filler injection in transgender women was 16.9%, they pointed out.

These types of noninvasive, gender-affirming procedures “may contribute to higher levels of self-confidence and [reduce] gender dysphoria. Future studies should examine motivations, barriers, and optimal timing” for such procedures in transgender persons, Dr. Ragmanauskaite and associates wrote.

The authors reported that they had no relevant disclosures.

, according to the results of a recent survey.

Transfeminine persons – those assigned male at birth – were much more likely to report a previous dermatologic procedure, compared with transmasculine respondents, by a margin of 64.9%-7.5%, Laura Ragmanauskaite, MD, and associates reported.

“Hair removal was the most frequently reported procedure type, with electrolysis being more common than laser hair removal,” they said, noting that “previous research on hair removal treatments among gender minority persons did not detect differences in the use of electrolysis and laser hair removal.”

Just under one-third of all respondents (32.9%) said that they had undergone electrolysis and 4.6% reported previous laser hair removal. For electrolysis, that works out to 59.4% of transfeminine and 6.1% of transmasculine respondents, while 9.1% of all transfeminine and no transmasculine persons had received laser hair removal, Dr. Ragmanauskaite of the department of dermatology, Emory University, Atlanta, and her coauthors said.

Those who had undergone gender-affirming surgery were significantly more likely to report electrolysis (78.6%) than were persons who had received no gender-affirming surgery or hormone therapy alone (47.4%), a statistically significant difference (P < .01). All of the other, less common procedures included in the online survey – 696 responses were received from 350 transfeminine and 346 transmasculine persons participating in the Study of Transition, Outcomes, and Gender – were reported more often by the transfeminine respondents. The procedure with the closest gender distribution was body contouring, reported by nine transfeminine and six transmasculine persons, the researchers said.

Use of dermal fillers was even less common (2.8% among all respondents, all transfeminine persons), with just 11 reporting having received silicone and 8 reporting having received collagen, although the survey did not ask about how the injections were obtained. In a previous study, the prevalence of illicit filler injection in transgender women was 16.9%, they pointed out.

These types of noninvasive, gender-affirming procedures “may contribute to higher levels of self-confidence and [reduce] gender dysphoria. Future studies should examine motivations, barriers, and optimal timing” for such procedures in transgender persons, Dr. Ragmanauskaite and associates wrote.

The authors reported that they had no relevant disclosures.

FROM DERMATOLOGIC SURGERY

Overview of guidelines for patients seeking gender-affirmation surgery

Gender-affirmation surgery refers to a collection of procedures by which a transgender individual physically alters characteristics to align with their gender identity. While not all patients who identify as transgender will choose to undergo surgery, the surgeries are considered medically necessary and lead to significant improvements in emotional and psychological well-being.1 With increasing insurance coverage and improved access to care, more and more patients are seeking gender-affirming surgery, and it is incumbent for providers to familiarize themselves with preoperative recommendations and requirements.

Ob.gyns. play a key role in patients seeking surgical treatment as patients may inquire about available procedures and what steps are necessary prior to scheduling a visit with the appropriate surgeon. The World Professional Association of Transgender Health has established standards of care that provide multidisciplinary, evidence-based guidance for patients seeking a variety of gender-affirming services ranging from mental health, hormone therapy, and surgery.

Basic preoperative surgical prerequisites set forth by WPATH include being a patient with well-documented gender dysphoria, being the age of majority, and having the ability to provide informed consent.1

As with any surgical candidate, it is also equally important for a patient to have well-controlled medical and psychiatric comorbidities, which should also include smoking cessation. A variety of surgical procedures are available to patients and include breast/chest surgery, genital (bottom) surgery, and nongenital surgery (facial feminization, pectoral implant placement, thyroid chondroplasty, lipofilling/liposuction, body contouring, and voice modification). Patients may choose to undergo chest/breast surgery and/or bottom surgery or forgo surgical procedures altogether.

For transmasculine patients, breast/chest surgery, otherwise known as top surgery, is the most common and desired procedure. According to a recent survey, approximately 97% of transmasculine patients had or wanted masculinizing chest surgery.2 In addition to patients meeting the basic requirements set forth by WPATH, one referral from a mental health provider specializing in gender-affirming care is also needed prior to this procedure. It is also important to note that testosterone use is no longer a needed prior to masculinizing chest surgery.

Transmasculine bottom surgery, which includes hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, metoidioplasty, vaginectomy, scrotoplasty, testicular implant placement, and/or phalloplasty have additional nuances. Compared with transmasculine individuals seeking top surgery, the number of patients who have had or desire metoidioplasty and phalloplasty is much lower, which is mainly because of the high complication rates of these procedures. In the same survey, only 4% of patients had undergone a metoidioplasty procedure and 2% of patients had undergone a phalloplasty.2

In evaluating rates of hysterectomy with or without salpingo-oophorectomy, approximately 21% of transgender men underwent hysterectomy, with 58% desiring it in the future.2 Unlike patients pursuing top surgery, patients who desire any form of bottom surgery need to be on 12 months of continuous hormone therapy.1 They also must provide two letters from two different mental health providers, one of whom must have either an MD/DO or PhD. In cases in which a patient requests a hysterectomy for reasons other than gender dysphoria, such as pelvic pain or abnormal uterine bleeding, these criteria do not apply.

For transfeminine individuals, augmentation mammoplasty is performed following 12 months of continuous hormone therapy. This is to allow maximum breast growth, which occurs approximately 2-3 months after hormone initiation and peaks at 1-2 years.3 Rates of transfeminine individuals seeking augmentation mammoplasty is similar to that of their transmasculine counterparts at 74%.2 One referral letter from a mental health provider is also needed prior to augmentation mammoplasty.

Transfeminine patients who desire bottom surgery, which can involve an orchiectomy or vaginoplasty (single-stage penile inversion, peritoneal, or colonic interposition), have the same additional requirements as transmasculine individuals seeking bottom surgery. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that 25% of transfeminine individuals had already undergone orchiectomy and 87% had either undergone or desired a vaginoplasty in the future.2 This is in stark contrast to transmasculine patients and rates of bottom surgery.

Unless there is a specific medical contraindication to hormone therapy, emphasis is placed on 12 months of continuous hormone usage. Additional emphasis is placed on patients seeking bottom surgery to live for a minimum of 12 months in their congruent gender role. This also allows patients to further explore their gender identity and make appropriate preparations for surgery.

As with any surgical procedure, obtaining informed consent and reviewing patient expectations are key. In my clinical practice, I discuss with patients that the general surgical goals are to achieve both function and good aesthetic outcome but that their results are also tailored to their individual bodies. Assessing a patient’s support system and social factors is also equally important in the preoperative planning period. As this field continues to grow, it is essential for providers to understand the evolving distinctions in surgical care to improve access to patients.

Dr. Brandt is an ob.gyn. and fellowship-trained gender-affirming surgeon in West Reading, Pa. She has no conflicts. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People. https://www.wpath.org/publications/soc.

2. James SE et al. The report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender survey. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Transgender Equality. 2016.

3. Thomas TN. Overview of surgery for transgender patients, in “Comprehensive care for the transgender patient.” Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2020. pp. 48-53.

Gender-affirmation surgery refers to a collection of procedures by which a transgender individual physically alters characteristics to align with their gender identity. While not all patients who identify as transgender will choose to undergo surgery, the surgeries are considered medically necessary and lead to significant improvements in emotional and psychological well-being.1 With increasing insurance coverage and improved access to care, more and more patients are seeking gender-affirming surgery, and it is incumbent for providers to familiarize themselves with preoperative recommendations and requirements.

Ob.gyns. play a key role in patients seeking surgical treatment as patients may inquire about available procedures and what steps are necessary prior to scheduling a visit with the appropriate surgeon. The World Professional Association of Transgender Health has established standards of care that provide multidisciplinary, evidence-based guidance for patients seeking a variety of gender-affirming services ranging from mental health, hormone therapy, and surgery.

Basic preoperative surgical prerequisites set forth by WPATH include being a patient with well-documented gender dysphoria, being the age of majority, and having the ability to provide informed consent.1

As with any surgical candidate, it is also equally important for a patient to have well-controlled medical and psychiatric comorbidities, which should also include smoking cessation. A variety of surgical procedures are available to patients and include breast/chest surgery, genital (bottom) surgery, and nongenital surgery (facial feminization, pectoral implant placement, thyroid chondroplasty, lipofilling/liposuction, body contouring, and voice modification). Patients may choose to undergo chest/breast surgery and/or bottom surgery or forgo surgical procedures altogether.

For transmasculine patients, breast/chest surgery, otherwise known as top surgery, is the most common and desired procedure. According to a recent survey, approximately 97% of transmasculine patients had or wanted masculinizing chest surgery.2 In addition to patients meeting the basic requirements set forth by WPATH, one referral from a mental health provider specializing in gender-affirming care is also needed prior to this procedure. It is also important to note that testosterone use is no longer a needed prior to masculinizing chest surgery.

Transmasculine bottom surgery, which includes hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, metoidioplasty, vaginectomy, scrotoplasty, testicular implant placement, and/or phalloplasty have additional nuances. Compared with transmasculine individuals seeking top surgery, the number of patients who have had or desire metoidioplasty and phalloplasty is much lower, which is mainly because of the high complication rates of these procedures. In the same survey, only 4% of patients had undergone a metoidioplasty procedure and 2% of patients had undergone a phalloplasty.2

In evaluating rates of hysterectomy with or without salpingo-oophorectomy, approximately 21% of transgender men underwent hysterectomy, with 58% desiring it in the future.2 Unlike patients pursuing top surgery, patients who desire any form of bottom surgery need to be on 12 months of continuous hormone therapy.1 They also must provide two letters from two different mental health providers, one of whom must have either an MD/DO or PhD. In cases in which a patient requests a hysterectomy for reasons other than gender dysphoria, such as pelvic pain or abnormal uterine bleeding, these criteria do not apply.

For transfeminine individuals, augmentation mammoplasty is performed following 12 months of continuous hormone therapy. This is to allow maximum breast growth, which occurs approximately 2-3 months after hormone initiation and peaks at 1-2 years.3 Rates of transfeminine individuals seeking augmentation mammoplasty is similar to that of their transmasculine counterparts at 74%.2 One referral letter from a mental health provider is also needed prior to augmentation mammoplasty.

Transfeminine patients who desire bottom surgery, which can involve an orchiectomy or vaginoplasty (single-stage penile inversion, peritoneal, or colonic interposition), have the same additional requirements as transmasculine individuals seeking bottom surgery. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that 25% of transfeminine individuals had already undergone orchiectomy and 87% had either undergone or desired a vaginoplasty in the future.2 This is in stark contrast to transmasculine patients and rates of bottom surgery.

Unless there is a specific medical contraindication to hormone therapy, emphasis is placed on 12 months of continuous hormone usage. Additional emphasis is placed on patients seeking bottom surgery to live for a minimum of 12 months in their congruent gender role. This also allows patients to further explore their gender identity and make appropriate preparations for surgery.

As with any surgical procedure, obtaining informed consent and reviewing patient expectations are key. In my clinical practice, I discuss with patients that the general surgical goals are to achieve both function and good aesthetic outcome but that their results are also tailored to their individual bodies. Assessing a patient’s support system and social factors is also equally important in the preoperative planning period. As this field continues to grow, it is essential for providers to understand the evolving distinctions in surgical care to improve access to patients.

Dr. Brandt is an ob.gyn. and fellowship-trained gender-affirming surgeon in West Reading, Pa. She has no conflicts. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People. https://www.wpath.org/publications/soc.

2. James SE et al. The report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender survey. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Transgender Equality. 2016.

3. Thomas TN. Overview of surgery for transgender patients, in “Comprehensive care for the transgender patient.” Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2020. pp. 48-53.

Gender-affirmation surgery refers to a collection of procedures by which a transgender individual physically alters characteristics to align with their gender identity. While not all patients who identify as transgender will choose to undergo surgery, the surgeries are considered medically necessary and lead to significant improvements in emotional and psychological well-being.1 With increasing insurance coverage and improved access to care, more and more patients are seeking gender-affirming surgery, and it is incumbent for providers to familiarize themselves with preoperative recommendations and requirements.

Ob.gyns. play a key role in patients seeking surgical treatment as patients may inquire about available procedures and what steps are necessary prior to scheduling a visit with the appropriate surgeon. The World Professional Association of Transgender Health has established standards of care that provide multidisciplinary, evidence-based guidance for patients seeking a variety of gender-affirming services ranging from mental health, hormone therapy, and surgery.

Basic preoperative surgical prerequisites set forth by WPATH include being a patient with well-documented gender dysphoria, being the age of majority, and having the ability to provide informed consent.1

As with any surgical candidate, it is also equally important for a patient to have well-controlled medical and psychiatric comorbidities, which should also include smoking cessation. A variety of surgical procedures are available to patients and include breast/chest surgery, genital (bottom) surgery, and nongenital surgery (facial feminization, pectoral implant placement, thyroid chondroplasty, lipofilling/liposuction, body contouring, and voice modification). Patients may choose to undergo chest/breast surgery and/or bottom surgery or forgo surgical procedures altogether.

For transmasculine patients, breast/chest surgery, otherwise known as top surgery, is the most common and desired procedure. According to a recent survey, approximately 97% of transmasculine patients had or wanted masculinizing chest surgery.2 In addition to patients meeting the basic requirements set forth by WPATH, one referral from a mental health provider specializing in gender-affirming care is also needed prior to this procedure. It is also important to note that testosterone use is no longer a needed prior to masculinizing chest surgery.

Transmasculine bottom surgery, which includes hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, metoidioplasty, vaginectomy, scrotoplasty, testicular implant placement, and/or phalloplasty have additional nuances. Compared with transmasculine individuals seeking top surgery, the number of patients who have had or desire metoidioplasty and phalloplasty is much lower, which is mainly because of the high complication rates of these procedures. In the same survey, only 4% of patients had undergone a metoidioplasty procedure and 2% of patients had undergone a phalloplasty.2

In evaluating rates of hysterectomy with or without salpingo-oophorectomy, approximately 21% of transgender men underwent hysterectomy, with 58% desiring it in the future.2 Unlike patients pursuing top surgery, patients who desire any form of bottom surgery need to be on 12 months of continuous hormone therapy.1 They also must provide two letters from two different mental health providers, one of whom must have either an MD/DO or PhD. In cases in which a patient requests a hysterectomy for reasons other than gender dysphoria, such as pelvic pain or abnormal uterine bleeding, these criteria do not apply.

For transfeminine individuals, augmentation mammoplasty is performed following 12 months of continuous hormone therapy. This is to allow maximum breast growth, which occurs approximately 2-3 months after hormone initiation and peaks at 1-2 years.3 Rates of transfeminine individuals seeking augmentation mammoplasty is similar to that of their transmasculine counterparts at 74%.2 One referral letter from a mental health provider is also needed prior to augmentation mammoplasty.

Transfeminine patients who desire bottom surgery, which can involve an orchiectomy or vaginoplasty (single-stage penile inversion, peritoneal, or colonic interposition), have the same additional requirements as transmasculine individuals seeking bottom surgery. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that 25% of transfeminine individuals had already undergone orchiectomy and 87% had either undergone or desired a vaginoplasty in the future.2 This is in stark contrast to transmasculine patients and rates of bottom surgery.

Unless there is a specific medical contraindication to hormone therapy, emphasis is placed on 12 months of continuous hormone usage. Additional emphasis is placed on patients seeking bottom surgery to live for a minimum of 12 months in their congruent gender role. This also allows patients to further explore their gender identity and make appropriate preparations for surgery.

As with any surgical procedure, obtaining informed consent and reviewing patient expectations are key. In my clinical practice, I discuss with patients that the general surgical goals are to achieve both function and good aesthetic outcome but that their results are also tailored to their individual bodies. Assessing a patient’s support system and social factors is also equally important in the preoperative planning period. As this field continues to grow, it is essential for providers to understand the evolving distinctions in surgical care to improve access to patients.

Dr. Brandt is an ob.gyn. and fellowship-trained gender-affirming surgeon in West Reading, Pa. She has no conflicts. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People. https://www.wpath.org/publications/soc.

2. James SE et al. The report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender survey. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Transgender Equality. 2016.

3. Thomas TN. Overview of surgery for transgender patients, in “Comprehensive care for the transgender patient.” Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2020. pp. 48-53.

My experience as a family medicine resident in 2021

I did not get a medical school graduation; I was one of the many thousands of newly graduated students who simply left their 4th-year rotation sites one chilly day in March 2020 and just never went back. My medical school education didn’t end with me walking triumphantly across the stage – a first-generation college student finally achieving the greatest dream in her life. Instead, it ended with a Zoom “graduation” and a cross-country move from Georgia to Pennsylvania amidst the greatest pandemic in recent memory. To say my impostor syndrome was bad would be an understatement.

Residency in the COVID-19-era

The joy and the draw to family medicine for me has always been the broad scope of conditions that we see and treat. From day 1, however, much of my residency has been devoted to one very small subset of patients – those with COVID-19. At one point, our hospital was so strained that our family medicine program had to run a second inpatient service alongside our usual five-resident service team just to provide care to everybody. Patients were in the hallways. The ER was packed to the gills. We were sleepless, terrified, unvaccinated, and desperate to help our patients survive a disease that was incompletely understood, with very few tools in our toolbox to combat it.

I distinctly remember sitting in the workroom with a coresident of mine, our faces seemingly permanently lined from wearing N95s all shift, and saying to him, “I worry I will be a bad family medicine physician. I worry I haven’t seen enough, other than COVID.” It was midway through my intern year; the days were short, so I was driving to and from the hospital in chilly darkness. My patients, like many around the country, were doing poorly. Vaccines seemed like a promise too good to be true. Worst of all: Those of us who were interns, who had no triumphant podium moment to end our medical school education, were suffering with an intense sense of impostor syndrome which was strengthened by every “there is nothing else we can offer your loved one at this time,” conversation we had. My apprehension about not having seen a wider breadth of medicine during my training is a sentiment still widely shared by COVID-era residents.

Luckily, my coresident was supportive.

“We’re going to be great family medicine physicians,” he said. “We’re learning the hard stuff – the bread and butter of FM – up-front. You’ll see.”

In some ways, I think he was right. Clinical skills, empathy, humility, and forging strong relationships are at the center of every family medicine physician’s heart; my generation has had to learn these skills early and under pressure. Sometimes, there are no answers. Sometimes, the best thing a family doctor can do for a patient is to hear them, understand them, and hold their hand.

‘We watched Cinderella together’

Shortly after that conversation with my coresident, I had a particular case which moved me. This gentleman with intellectual disability and COVID had been declining steadily since his admission to the hospital. He was isolated from everybody he knew and loved, but it did not dampen his spirits. He was cheerful to every person who entered his room, clad in their shrouds of PPE, which more often than not felt more like mourning garb than protective wear. I remember very little about this patient’s clinical picture – the COVID, the superimposed pneumonia, the repeated intubations. What I do remember is he loved the Disney classic, Cinderella. I knew this because I developed a very close relationship with his family during the course of his hospitalization. Amidst the torrential onslaught of patients, I made sure to call families every day – not because I wanted to, but because my mentors and attendings and coresidents had all drilled into me from day 1 that we are family medicine, and a large part of our role is to advocate for our patients, and to communicate with their loved ones. So I called. I learned a lot about him; his likes, his dislikes, his close bond with his siblings, and of course his lifelong love for Cinderella. On the last week of my ICU rotation, my patient passed peacefully. His nurse and I were bedside. We held his hand. We told him his family loved him. We watched Cinderella together on an iPad encased in protective plastic.

My next rotation was an outpatient one and it looked more like the “bread and butter” of family medicine. But as I whisked in and out of patient rooms, attending to patients with diabetes, with depression, with pain, I could not stop thinking about my hospitalized patients who my coresidents had assumed care of. Each exam room I entered, I rather morbidly thought “this patient could be next on our hospital service.” Without realizing it, I made more of an effort to get to know each patient holistically. I learned who they were as people. I found myself writing small, medically low-yield details in the chart: “Margaret loves to sing in her church choir;” “Katherine is a self-published author.”

I learned from my attendings. As I sat at the precepting table with them, observing their conversations about patients, their collective decades of experience were apparent.

“I’ve been seeing this patient every few weeks since I was a resident,” said one of my attendings.

“I don’t even see my parents that often,” I thought.

The depth of her relationship with, understanding of, and compassion for this patient struck me deeply. This was why I went into family medicine. My attending knew her patients; they were not faceless unknowns in a hospital gown to her. She would have known to play Cinderella for them in the end.

This is a unique time for trainees. We have been challenged, terrified, overwhelmed, and heartbroken. But at no point have we been isolated. We’ve had the generations of doctors before us to lead the way, to teach us the “hard stuff.” We’ve had senior residents to lean on, who have taken us aside and told us, “I can do the goals-of-care talk today, you need a break.” While the plague seems to have passed over our hospital for now, it has left behind a class of family medicine residents who are proud to carry on our specialty’s long tradition of compassionate, empathetic, lifelong care. “We care for all life stages, from cradle to grave,” says every family medicine physician.

My class, for better or for worse, has cared more often for patients in the twilight of their lives, and while it has been hard, I believe it has made us all better doctors. Now, when I hold a newborn in my arms for a well-child check, I am exceptionally grateful – for the opportunities I have been given, for new beginnings amidst so much sadness, and for the great privilege of being a family medicine physician.

Dr. Persampiere is a 2nd-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. You can contact her directly at [email protected] or via [email protected].

I did not get a medical school graduation; I was one of the many thousands of newly graduated students who simply left their 4th-year rotation sites one chilly day in March 2020 and just never went back. My medical school education didn’t end with me walking triumphantly across the stage – a first-generation college student finally achieving the greatest dream in her life. Instead, it ended with a Zoom “graduation” and a cross-country move from Georgia to Pennsylvania amidst the greatest pandemic in recent memory. To say my impostor syndrome was bad would be an understatement.

Residency in the COVID-19-era

The joy and the draw to family medicine for me has always been the broad scope of conditions that we see and treat. From day 1, however, much of my residency has been devoted to one very small subset of patients – those with COVID-19. At one point, our hospital was so strained that our family medicine program had to run a second inpatient service alongside our usual five-resident service team just to provide care to everybody. Patients were in the hallways. The ER was packed to the gills. We were sleepless, terrified, unvaccinated, and desperate to help our patients survive a disease that was incompletely understood, with very few tools in our toolbox to combat it.

I distinctly remember sitting in the workroom with a coresident of mine, our faces seemingly permanently lined from wearing N95s all shift, and saying to him, “I worry I will be a bad family medicine physician. I worry I haven’t seen enough, other than COVID.” It was midway through my intern year; the days were short, so I was driving to and from the hospital in chilly darkness. My patients, like many around the country, were doing poorly. Vaccines seemed like a promise too good to be true. Worst of all: Those of us who were interns, who had no triumphant podium moment to end our medical school education, were suffering with an intense sense of impostor syndrome which was strengthened by every “there is nothing else we can offer your loved one at this time,” conversation we had. My apprehension about not having seen a wider breadth of medicine during my training is a sentiment still widely shared by COVID-era residents.

Luckily, my coresident was supportive.

“We’re going to be great family medicine physicians,” he said. “We’re learning the hard stuff – the bread and butter of FM – up-front. You’ll see.”

In some ways, I think he was right. Clinical skills, empathy, humility, and forging strong relationships are at the center of every family medicine physician’s heart; my generation has had to learn these skills early and under pressure. Sometimes, there are no answers. Sometimes, the best thing a family doctor can do for a patient is to hear them, understand them, and hold their hand.

‘We watched Cinderella together’

Shortly after that conversation with my coresident, I had a particular case which moved me. This gentleman with intellectual disability and COVID had been declining steadily since his admission to the hospital. He was isolated from everybody he knew and loved, but it did not dampen his spirits. He was cheerful to every person who entered his room, clad in their shrouds of PPE, which more often than not felt more like mourning garb than protective wear. I remember very little about this patient’s clinical picture – the COVID, the superimposed pneumonia, the repeated intubations. What I do remember is he loved the Disney classic, Cinderella. I knew this because I developed a very close relationship with his family during the course of his hospitalization. Amidst the torrential onslaught of patients, I made sure to call families every day – not because I wanted to, but because my mentors and attendings and coresidents had all drilled into me from day 1 that we are family medicine, and a large part of our role is to advocate for our patients, and to communicate with their loved ones. So I called. I learned a lot about him; his likes, his dislikes, his close bond with his siblings, and of course his lifelong love for Cinderella. On the last week of my ICU rotation, my patient passed peacefully. His nurse and I were bedside. We held his hand. We told him his family loved him. We watched Cinderella together on an iPad encased in protective plastic.

My next rotation was an outpatient one and it looked more like the “bread and butter” of family medicine. But as I whisked in and out of patient rooms, attending to patients with diabetes, with depression, with pain, I could not stop thinking about my hospitalized patients who my coresidents had assumed care of. Each exam room I entered, I rather morbidly thought “this patient could be next on our hospital service.” Without realizing it, I made more of an effort to get to know each patient holistically. I learned who they were as people. I found myself writing small, medically low-yield details in the chart: “Margaret loves to sing in her church choir;” “Katherine is a self-published author.”

I learned from my attendings. As I sat at the precepting table with them, observing their conversations about patients, their collective decades of experience were apparent.

“I’ve been seeing this patient every few weeks since I was a resident,” said one of my attendings.

“I don’t even see my parents that often,” I thought.

The depth of her relationship with, understanding of, and compassion for this patient struck me deeply. This was why I went into family medicine. My attending knew her patients; they were not faceless unknowns in a hospital gown to her. She would have known to play Cinderella for them in the end.

This is a unique time for trainees. We have been challenged, terrified, overwhelmed, and heartbroken. But at no point have we been isolated. We’ve had the generations of doctors before us to lead the way, to teach us the “hard stuff.” We’ve had senior residents to lean on, who have taken us aside and told us, “I can do the goals-of-care talk today, you need a break.” While the plague seems to have passed over our hospital for now, it has left behind a class of family medicine residents who are proud to carry on our specialty’s long tradition of compassionate, empathetic, lifelong care. “We care for all life stages, from cradle to grave,” says every family medicine physician.

My class, for better or for worse, has cared more often for patients in the twilight of their lives, and while it has been hard, I believe it has made us all better doctors. Now, when I hold a newborn in my arms for a well-child check, I am exceptionally grateful – for the opportunities I have been given, for new beginnings amidst so much sadness, and for the great privilege of being a family medicine physician.

Dr. Persampiere is a 2nd-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. You can contact her directly at [email protected] or via [email protected].

I did not get a medical school graduation; I was one of the many thousands of newly graduated students who simply left their 4th-year rotation sites one chilly day in March 2020 and just never went back. My medical school education didn’t end with me walking triumphantly across the stage – a first-generation college student finally achieving the greatest dream in her life. Instead, it ended with a Zoom “graduation” and a cross-country move from Georgia to Pennsylvania amidst the greatest pandemic in recent memory. To say my impostor syndrome was bad would be an understatement.

Residency in the COVID-19-era

The joy and the draw to family medicine for me has always been the broad scope of conditions that we see and treat. From day 1, however, much of my residency has been devoted to one very small subset of patients – those with COVID-19. At one point, our hospital was so strained that our family medicine program had to run a second inpatient service alongside our usual five-resident service team just to provide care to everybody. Patients were in the hallways. The ER was packed to the gills. We were sleepless, terrified, unvaccinated, and desperate to help our patients survive a disease that was incompletely understood, with very few tools in our toolbox to combat it.

I distinctly remember sitting in the workroom with a coresident of mine, our faces seemingly permanently lined from wearing N95s all shift, and saying to him, “I worry I will be a bad family medicine physician. I worry I haven’t seen enough, other than COVID.” It was midway through my intern year; the days were short, so I was driving to and from the hospital in chilly darkness. My patients, like many around the country, were doing poorly. Vaccines seemed like a promise too good to be true. Worst of all: Those of us who were interns, who had no triumphant podium moment to end our medical school education, were suffering with an intense sense of impostor syndrome which was strengthened by every “there is nothing else we can offer your loved one at this time,” conversation we had. My apprehension about not having seen a wider breadth of medicine during my training is a sentiment still widely shared by COVID-era residents.

Luckily, my coresident was supportive.

“We’re going to be great family medicine physicians,” he said. “We’re learning the hard stuff – the bread and butter of FM – up-front. You’ll see.”

In some ways, I think he was right. Clinical skills, empathy, humility, and forging strong relationships are at the center of every family medicine physician’s heart; my generation has had to learn these skills early and under pressure. Sometimes, there are no answers. Sometimes, the best thing a family doctor can do for a patient is to hear them, understand them, and hold their hand.

‘We watched Cinderella together’

Shortly after that conversation with my coresident, I had a particular case which moved me. This gentleman with intellectual disability and COVID had been declining steadily since his admission to the hospital. He was isolated from everybody he knew and loved, but it did not dampen his spirits. He was cheerful to every person who entered his room, clad in their shrouds of PPE, which more often than not felt more like mourning garb than protective wear. I remember very little about this patient’s clinical picture – the COVID, the superimposed pneumonia, the repeated intubations. What I do remember is he loved the Disney classic, Cinderella. I knew this because I developed a very close relationship with his family during the course of his hospitalization. Amidst the torrential onslaught of patients, I made sure to call families every day – not because I wanted to, but because my mentors and attendings and coresidents had all drilled into me from day 1 that we are family medicine, and a large part of our role is to advocate for our patients, and to communicate with their loved ones. So I called. I learned a lot about him; his likes, his dislikes, his close bond with his siblings, and of course his lifelong love for Cinderella. On the last week of my ICU rotation, my patient passed peacefully. His nurse and I were bedside. We held his hand. We told him his family loved him. We watched Cinderella together on an iPad encased in protective plastic.

My next rotation was an outpatient one and it looked more like the “bread and butter” of family medicine. But as I whisked in and out of patient rooms, attending to patients with diabetes, with depression, with pain, I could not stop thinking about my hospitalized patients who my coresidents had assumed care of. Each exam room I entered, I rather morbidly thought “this patient could be next on our hospital service.” Without realizing it, I made more of an effort to get to know each patient holistically. I learned who they were as people. I found myself writing small, medically low-yield details in the chart: “Margaret loves to sing in her church choir;” “Katherine is a self-published author.”

I learned from my attendings. As I sat at the precepting table with them, observing their conversations about patients, their collective decades of experience were apparent.

“I’ve been seeing this patient every few weeks since I was a resident,” said one of my attendings.

“I don’t even see my parents that often,” I thought.

The depth of her relationship with, understanding of, and compassion for this patient struck me deeply. This was why I went into family medicine. My attending knew her patients; they were not faceless unknowns in a hospital gown to her. She would have known to play Cinderella for them in the end.

This is a unique time for trainees. We have been challenged, terrified, overwhelmed, and heartbroken. But at no point have we been isolated. We’ve had the generations of doctors before us to lead the way, to teach us the “hard stuff.” We’ve had senior residents to lean on, who have taken us aside and told us, “I can do the goals-of-care talk today, you need a break.” While the plague seems to have passed over our hospital for now, it has left behind a class of family medicine residents who are proud to carry on our specialty’s long tradition of compassionate, empathetic, lifelong care. “We care for all life stages, from cradle to grave,” says every family medicine physician.

My class, for better or for worse, has cared more often for patients in the twilight of their lives, and while it has been hard, I believe it has made us all better doctors. Now, when I hold a newborn in my arms for a well-child check, I am exceptionally grateful – for the opportunities I have been given, for new beginnings amidst so much sadness, and for the great privilege of being a family medicine physician.

Dr. Persampiere is a 2nd-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. You can contact her directly at [email protected] or via [email protected].

Tiny worms sniff out early-stage pancreatic cancer

Research shows Caenorhabditis elegans are attracted to the odor certain chemicals give off – a behavior known as attractive chemotaxis – and early evidence indicates these scents may include human cancer cell secretions, cancer tissues, and urine from patients with colorectal, gastric, and breast cancers.

According to the recent analysis, published in Oncotarget, these small worms may be hot on the trail of pancreatic cancer–related compounds too. The researchers found that C. elegans were significantly more attracted to patients with early-stage pancreatic cancer versus healthy controls.

There is a huge need for research like this that explores strategies to detect pancreatic cancer early, but it’s far too soon to tell how, or if, this particular approach will be clinically relevant, according to Neeha Zaidi, MD, assistant professor of oncology and a medical oncologist specializing in pancreatic cancer at John Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, who was not involved in the current analysis.

Right now, few diagnostic markers exist for identifying pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDACs), which account for 90% of pancreatic cancers. PDACs remain one of the deadliest cancers, with a 5-year survival rate of 9%.

A combination of surgical resection and chemotherapy is the only curative treatment, and just 20% of patients are eligible, Dr. Zaidi said. The majority are identified after the disease has metastasized.

However, patients’ 5-year survival rate improves markedly – as high as 85% – if the condition is caught sooner.

In the current study, the researchers first exposed C. elegans to the urine of 83 patients from cancer centers across Japan who had various stages of pancreatic cancer before and after undergoing surgical resection. Using an assay, which takes 30 minutes and 50-100 nematodes per test, C. elegans showed significantly higher chemotaxis toward preoperative urine, compared with postoperative urine.

In a second, closed-labeled arm, the nematodes were exposed to the urine of 28 randomized participants – 11 of whom had early-stage pancreatic cancer (0 or IA), plus 17 healthy volunteers. In this instance as well, C. elegans showed significantly higher chemotaxis in patients with early-stage pancreatic cancer, compared with healthy volunteers (P = .034).

According to the authors, C. elegans “had a higher sensitivity for detecting early pancreatic cancer compared to existing diagnostic markers.” And while this strategy needs to be further validated, they believe early detection of pancreatic cancer using C. elegans “can certainly be expected in the near future.”

The study aligns with previous research, showing that wild-type C. elegans are sensitive to scent and that these critters can smell cancer. Other studies have also found that sniffer canines can detect volatile organic compounds – including biomarkers of certain cancers – in the urine and breath of cancer patients. But training an adequate number of these canines for the clinic isn’t feasible, while C. elegans are far more compact and affordable.

According to Dr. Zaidi, a scent test using C. elegans “seems pretty feasible” and cost effective, but whether this approach will “change our care has yet to be determined.”

The authors, for instance, don’t specify how the scent test will be used, though Dr. Zaidi suspects it would be most relevant for following patients with a higher risk of pancreatic cancer. Alternatively, it could be used as a screening test, but that’s a massive undertaking and “this is way too early to tell if it’s going to be helpful to use this test on a broad scale,” Dr. Zaidi said.

To validate the approach, researchers would also need to know what exactly the C. elegans are smelling and to test it in a much larger number of patients, Dr. Zaidi said. The mere 11 patients with cancer in the blinded portion of the study are not sufficient to draw any major conclusions.

The study also claims a high sensitivity, but what about specificity, Dr. Zaidi said. In other words, are there a lot of false positives?

In addition, a deeper look at the participants shows the two groups – early PDAC and healthy volunteers – were not adequately balanced. The median age of the diseased patients was 70, and the healthy volunteers was 39.

“This is a big difference,” Eithne Costello, PhD, professor of molecular oncology at Liverpool (England) University, said in an interview. “It [also] appears the controls are all of one sex (either all male or all female), while the cancer group is mixed.”

The authors attributed these shortcomings to the small population they had to work with: There simply aren’t many patients whose pancreatic cancer is detected early. Dr. Zaidi agreed that patients with pancreatic cancer stage 0 or IA are extremely difficult to come by.

Even still, researchers need to understand the mechanisms behind this approach and see it work in a much larger group of patients, Dr. Zaidi said.

The study was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology. The authors reported institutional endowments received from Hirotsu Bio Science, Kinshu-kai Medical, IDEA Consultants, Ono Pharmaceutical, and others. Two coauthors are employees of Hirotsu Bio Science.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Research shows Caenorhabditis elegans are attracted to the odor certain chemicals give off – a behavior known as attractive chemotaxis – and early evidence indicates these scents may include human cancer cell secretions, cancer tissues, and urine from patients with colorectal, gastric, and breast cancers.

According to the recent analysis, published in Oncotarget, these small worms may be hot on the trail of pancreatic cancer–related compounds too. The researchers found that C. elegans were significantly more attracted to patients with early-stage pancreatic cancer versus healthy controls.

There is a huge need for research like this that explores strategies to detect pancreatic cancer early, but it’s far too soon to tell how, or if, this particular approach will be clinically relevant, according to Neeha Zaidi, MD, assistant professor of oncology and a medical oncologist specializing in pancreatic cancer at John Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, who was not involved in the current analysis.

Right now, few diagnostic markers exist for identifying pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDACs), which account for 90% of pancreatic cancers. PDACs remain one of the deadliest cancers, with a 5-year survival rate of 9%.

A combination of surgical resection and chemotherapy is the only curative treatment, and just 20% of patients are eligible, Dr. Zaidi said. The majority are identified after the disease has metastasized.

However, patients’ 5-year survival rate improves markedly – as high as 85% – if the condition is caught sooner.

In the current study, the researchers first exposed C. elegans to the urine of 83 patients from cancer centers across Japan who had various stages of pancreatic cancer before and after undergoing surgical resection. Using an assay, which takes 30 minutes and 50-100 nematodes per test, C. elegans showed significantly higher chemotaxis toward preoperative urine, compared with postoperative urine.

In a second, closed-labeled arm, the nematodes were exposed to the urine of 28 randomized participants – 11 of whom had early-stage pancreatic cancer (0 or IA), plus 17 healthy volunteers. In this instance as well, C. elegans showed significantly higher chemotaxis in patients with early-stage pancreatic cancer, compared with healthy volunteers (P = .034).

According to the authors, C. elegans “had a higher sensitivity for detecting early pancreatic cancer compared to existing diagnostic markers.” And while this strategy needs to be further validated, they believe early detection of pancreatic cancer using C. elegans “can certainly be expected in the near future.”

The study aligns with previous research, showing that wild-type C. elegans are sensitive to scent and that these critters can smell cancer. Other studies have also found that sniffer canines can detect volatile organic compounds – including biomarkers of certain cancers – in the urine and breath of cancer patients. But training an adequate number of these canines for the clinic isn’t feasible, while C. elegans are far more compact and affordable.

According to Dr. Zaidi, a scent test using C. elegans “seems pretty feasible” and cost effective, but whether this approach will “change our care has yet to be determined.”

The authors, for instance, don’t specify how the scent test will be used, though Dr. Zaidi suspects it would be most relevant for following patients with a higher risk of pancreatic cancer. Alternatively, it could be used as a screening test, but that’s a massive undertaking and “this is way too early to tell if it’s going to be helpful to use this test on a broad scale,” Dr. Zaidi said.

To validate the approach, researchers would also need to know what exactly the C. elegans are smelling and to test it in a much larger number of patients, Dr. Zaidi said. The mere 11 patients with cancer in the blinded portion of the study are not sufficient to draw any major conclusions.

The study also claims a high sensitivity, but what about specificity, Dr. Zaidi said. In other words, are there a lot of false positives?

In addition, a deeper look at the participants shows the two groups – early PDAC and healthy volunteers – were not adequately balanced. The median age of the diseased patients was 70, and the healthy volunteers was 39.

“This is a big difference,” Eithne Costello, PhD, professor of molecular oncology at Liverpool (England) University, said in an interview. “It [also] appears the controls are all of one sex (either all male or all female), while the cancer group is mixed.”

The authors attributed these shortcomings to the small population they had to work with: There simply aren’t many patients whose pancreatic cancer is detected early. Dr. Zaidi agreed that patients with pancreatic cancer stage 0 or IA are extremely difficult to come by.

Even still, researchers need to understand the mechanisms behind this approach and see it work in a much larger group of patients, Dr. Zaidi said.

The study was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology. The authors reported institutional endowments received from Hirotsu Bio Science, Kinshu-kai Medical, IDEA Consultants, Ono Pharmaceutical, and others. Two coauthors are employees of Hirotsu Bio Science.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Research shows Caenorhabditis elegans are attracted to the odor certain chemicals give off – a behavior known as attractive chemotaxis – and early evidence indicates these scents may include human cancer cell secretions, cancer tissues, and urine from patients with colorectal, gastric, and breast cancers.

According to the recent analysis, published in Oncotarget, these small worms may be hot on the trail of pancreatic cancer–related compounds too. The researchers found that C. elegans were significantly more attracted to patients with early-stage pancreatic cancer versus healthy controls.

There is a huge need for research like this that explores strategies to detect pancreatic cancer early, but it’s far too soon to tell how, or if, this particular approach will be clinically relevant, according to Neeha Zaidi, MD, assistant professor of oncology and a medical oncologist specializing in pancreatic cancer at John Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, who was not involved in the current analysis.

Right now, few diagnostic markers exist for identifying pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDACs), which account for 90% of pancreatic cancers. PDACs remain one of the deadliest cancers, with a 5-year survival rate of 9%.

A combination of surgical resection and chemotherapy is the only curative treatment, and just 20% of patients are eligible, Dr. Zaidi said. The majority are identified after the disease has metastasized.

However, patients’ 5-year survival rate improves markedly – as high as 85% – if the condition is caught sooner.

In the current study, the researchers first exposed C. elegans to the urine of 83 patients from cancer centers across Japan who had various stages of pancreatic cancer before and after undergoing surgical resection. Using an assay, which takes 30 minutes and 50-100 nematodes per test, C. elegans showed significantly higher chemotaxis toward preoperative urine, compared with postoperative urine.

In a second, closed-labeled arm, the nematodes were exposed to the urine of 28 randomized participants – 11 of whom had early-stage pancreatic cancer (0 or IA), plus 17 healthy volunteers. In this instance as well, C. elegans showed significantly higher chemotaxis in patients with early-stage pancreatic cancer, compared with healthy volunteers (P = .034).

According to the authors, C. elegans “had a higher sensitivity for detecting early pancreatic cancer compared to existing diagnostic markers.” And while this strategy needs to be further validated, they believe early detection of pancreatic cancer using C. elegans “can certainly be expected in the near future.”

The study aligns with previous research, showing that wild-type C. elegans are sensitive to scent and that these critters can smell cancer. Other studies have also found that sniffer canines can detect volatile organic compounds – including biomarkers of certain cancers – in the urine and breath of cancer patients. But training an adequate number of these canines for the clinic isn’t feasible, while C. elegans are far more compact and affordable.

According to Dr. Zaidi, a scent test using C. elegans “seems pretty feasible” and cost effective, but whether this approach will “change our care has yet to be determined.”

The authors, for instance, don’t specify how the scent test will be used, though Dr. Zaidi suspects it would be most relevant for following patients with a higher risk of pancreatic cancer. Alternatively, it could be used as a screening test, but that’s a massive undertaking and “this is way too early to tell if it’s going to be helpful to use this test on a broad scale,” Dr. Zaidi said.

To validate the approach, researchers would also need to know what exactly the C. elegans are smelling and to test it in a much larger number of patients, Dr. Zaidi said. The mere 11 patients with cancer in the blinded portion of the study are not sufficient to draw any major conclusions.

The study also claims a high sensitivity, but what about specificity, Dr. Zaidi said. In other words, are there a lot of false positives?

In addition, a deeper look at the participants shows the two groups – early PDAC and healthy volunteers – were not adequately balanced. The median age of the diseased patients was 70, and the healthy volunteers was 39.

“This is a big difference,” Eithne Costello, PhD, professor of molecular oncology at Liverpool (England) University, said in an interview. “It [also] appears the controls are all of one sex (either all male or all female), while the cancer group is mixed.”

The authors attributed these shortcomings to the small population they had to work with: There simply aren’t many patients whose pancreatic cancer is detected early. Dr. Zaidi agreed that patients with pancreatic cancer stage 0 or IA are extremely difficult to come by.